1. Introduction

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is increasingly utilised as a preoperative risk stratification tool to predict postoperative outcomes and to inform shared decision-making processes [

1,

2,

3]. Accurate functional assessment is critical for reliable preoperative evaluation and can guide strategies for both prehabilitation and rehabilitation [

4]. These strategies aim to deliver individualised perioperative care while reducing the risk of surgical complications, which are costly for both patients and healthcare providers.

However, as surgical demand grows alongside an ageing and increasingly medically complex population, the demand for CPET testing has also risen. CPET is time-consuming, expensive, and not universally available, as few centres have the capacity to test all patients requiring risk stratification. Current UK guidelines[

5] recommend screening all patients with validated tools, such as the Duke Activity Status Index, Godin-Shepard Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, or the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Patients identified as having reduced fitness through these tools should then be referred for CPET testing.

Simpler objective tests of functional capacity, including the incremental shuttle walk test, six-minute walk test, one-minute sit-to-stand test, and timed up-and-go test, have been explored as alternative strategies for routine preoperative assessment. These tests may serve as either replacements for CPET in resource-limited settings or as screening tools to identify patients who would benefit most from CPET [

4]. Notably, the Duke Activity Status Index and six-minute walk test have demonstrated predictive value for postoperative outcomes in perioperative cohorts.[

4,

6]

Frailty assessments have also emerged as valuable adjuncts in preoperative risk stratification. Tools such as the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) and the Fried Frailty Phenotype have shown promise in predicting postoperative outcomes, particularly in major abdominal and thoracic surgeries, as well as in older adults undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery[

7,

8]. The CFS is a clinician-administered tool that evaluates frailty based on physical, cognitive, and functional impairments. It categorises individuals on a scale from "very fit [

1]" to "terminally ill"[

9] based on the accumulation of health deficits. Despite its potential, limited research has investigated the utility of the CFS as a surrogate for CPET or as an independent tool for preoperative risk stratification[

10]. We hypothesise that the CFS could serve as a useful adjunct to identify patients with reduced functional capacity and predict those at higher perioperative mortality risk.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective observational study of adult patients (≥18 years) undergoing CPET testing at a single district general hospital site between May 2018 and December 2022 was performed. Patients received their CPET test as part of the standard perioperative referral pathway following referrals from the study site or three other district general hospitals in the region. Patients were referred according to local criteria, including major elective surgery, anticipated major surgical risk (ASA class ≥III) or reduced functional capacity assessed through clinical evaluation by the referring team. Patients were excluded from analysis if they had either missing CPET data or CFS score.

Data were extracted from electronic health records and included demographics (eg age, sex, BMI), comorbidities and CPET results. Descriptive data were collected from clinic notes and hospital episode records at the test site and calculated for the study population. CPET was performed on a cycle ergometer using an incremental ramp protocol . All tests were completed and validated by a single trained physiologist following standardised protocol(11). CPET data included peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak), anaerobic threshold (AT) and ventilatory equivalents at anaerobic threshold (VE/VCO2). The Rockwood CFS score(9) was assessed at presentation for CPET testing for all patients by their clinical team.

The primary endpoints were the associations between Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) scores and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) variables, including VO₂ peak, anaerobic threshold (AT), and ventilatory efficiency (VE/VCO₂). Linear regression models were used to analyse relationships between CFS scores and CPET parameters, while Spearman’s rank correlation tested the strength and direction of associations.

Additionally, as further analysis, an ordinal logistic regression model was applied to explore the association between CPET variables and CFS scores. The correlation between CFS score and 1-year mortality in the same group was also evaluated. A logistic regression model was applied to determine the predictive power of CFS score for 1-year mortality. Statistical significance was assessed for all tested associations.

A subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the correlation (Spearman’s rank) between CFS score and length of hospital stay in patients who proceeded to surgery at the host site.

All data was analysed using R, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, r-project.org.

A retrospective review of anonymised routinely collected data met criteria for it being a service evaluation study rather than one requiring ethical approval.

3. Results

A total of 179 patients with CPET data were initially included. After excluding 5 cases due to missing values, 174 patients with matched CFS and CPET data were analysed. Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The mean Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) score was 3 (range: 1–5). CPET-derived variables showed a mean VO₂ peak of 15.9 ml/kg/min (range: 5.7–28.0, SD: 3.51), a mean anaerobic threshold of 12.7 ml/kg/min (range: 4.8–22.0, SD: 2.8), and a mean ventilatory equivalent slope of 35.6 (range: 18–61, SD: 6.2)

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis revealed a weak association between CFS score and CPET results. The correlation coefficients for VO₂ peak and anaerobic threshold were -0.34 (p < 0.001) and -0.36 (p < 0.001), respectively. A weak positive correlation was observed between CFS score and ventilatory equivalents, with a coefficient of 0.31 (p < 0.001)

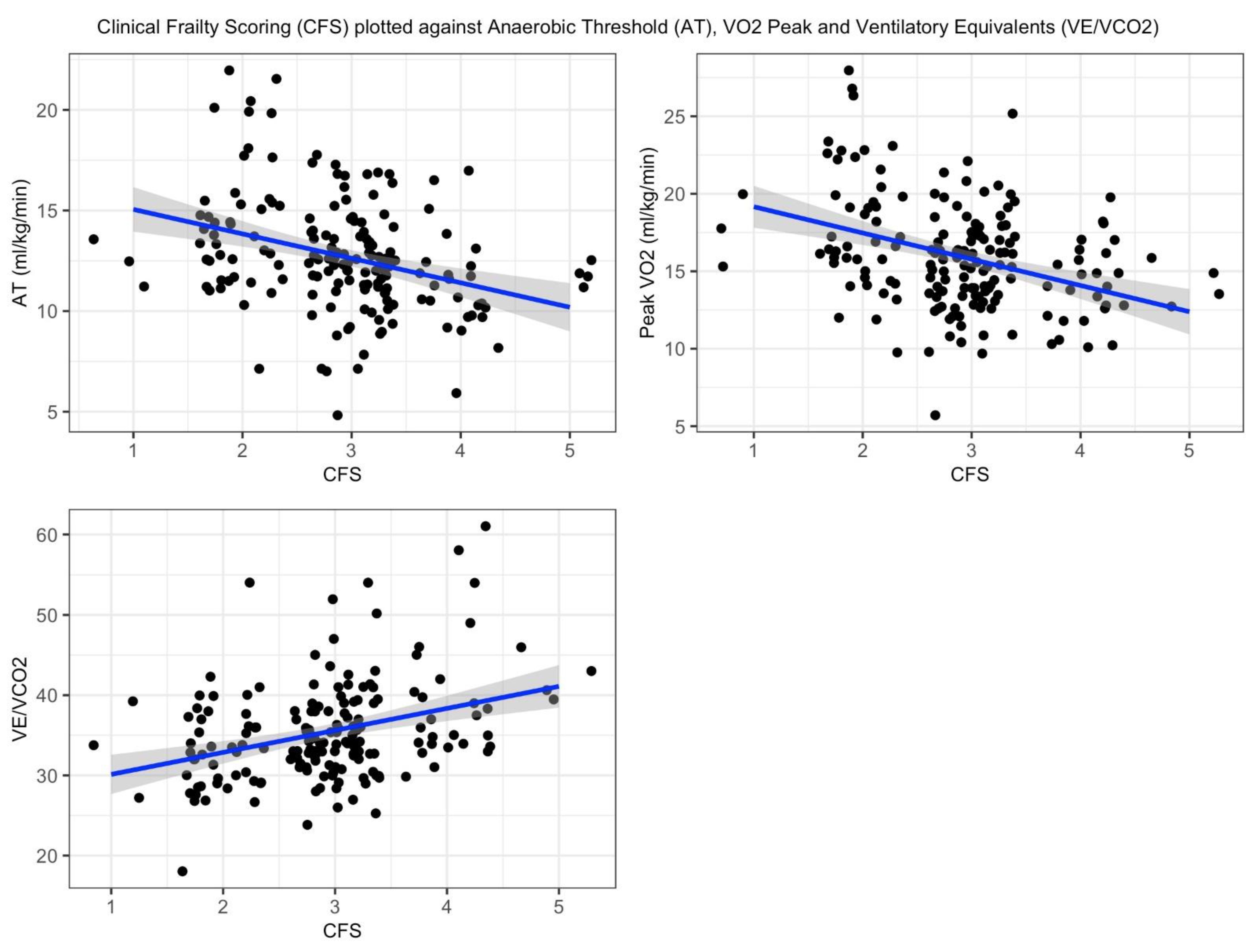

Linear regression modeling showed a significant negative association between Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) scores and CPET variables. For every unit increase in CFS score, VO₂ peak decreased by 1.22 (p<0.001), and the anaerobic threshold (AT) decreased by 1.70 (p<0.001). In contrast, ventilatory equivalents (VE/VCO₂) demonstrated a significant positive association, increasing by 2.74 per unit increase in CFS score (p<0.001). The adjusted R² values for the models were 0.13, 0.10, and 0.10, respectively. Linear regression plots are presented in

Appendix A.

Ordinal logistic regression modeling of CPET variables to predict CFS demonstrated negative coefficients for VO2 peak (-0.22) and AT (-0.24), both with p < 0.001. Ventilatory equivalents showed a weak positive coefficient (0.10, p < 0.001). For VO2 peak and AT as predictors of CFS, thresholds shifted from negative to positive between CFS scores 4 and 5. A similar shift occurred between CFS scores 2 and 3 for ventilatory equivalents.

In the subgroup analysis of those patients that proceeded to surgery at the host site, (n=59), mean length of stay was 12 days (SD 22.8). CFS score demonstrated no correlation with length of stay (coefficient= 0.037).

3.1. Year Mortality Data

At 1 year, 19 deaths were recorded (10.9%). The CFS score showed a weak positive correlation with 1-year mortality (coefficient 0.11), which did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.17). Logistic regression analysis indicated that each unit increase in CFS score was associated with an odds ratio of 1.4 for 1 year mortality; however, this result was not statistically significant (p = 0.22).

4. Discussion

This retrospective cohort analysis, representing a typical perioperative population with regards to CPET values[

11], compared a clinician-assessed measure of patients’ frailty, the CFS, with the gold standard method of pre-operative risk stratification, CPET testing. CPET is complex, time consuming and costly for the provider and patient whereas CFS scoring is simple, quick and non-invasive, offering a potential avenue for improvement of the risk stratification process of patients prior to major surgery.

Whilst it is intuitive that the functional status of a patient may correlate with CPET performance, there is currently a paucity of literature available to support this. One study by O’Mahoney et al (10) demonstrated a weak association between CPET and CFS scores, similar to the findings of this study, but beyond this there has been little investigation of the use of CFS status as a potential surrogate for formal CPET testing.

This study found a weak correlation between CFS scores and CPET variables. However, the relatively low adjusted R² values (0.13, 0.10, and 0.10 for VO2 peak, AT and ventilatory equivalents respectively) suggest that the models account for only a small proportion of the variability in the outcomes. This indicates that other unmeasured or unaccounted-for factors may be influencing these variables, highlighting the potential for additional predictors to improve the explanatory power of the models.

Ordinal regression analysis revealed that CFS categories 1-4 exhibited an increasing probability of transitioning to a higher category as both anaerobic threshold (AT) and VO2 peak decreased. This linear relationship supports the weak overall association observed. This pattern continued up to category 4-5, suggesting that CFS category 4 may represent a threshold beyond which further reductions in CPET values have minimal impact on CFS scoring. Similarly, mortality data exhibited a weak positive association, with increasing mortality observed as CFS scores rose. However, linear regression analysis showed a non-significant coefficient, indicating insufficient evidence to conclude that CFS score alone is a significant predictor of 1-year mortality in this cohort.

Whilst the presented study provides more investigation of the relationship between a frailty assessment and CPET performance, there are limitations. Due to resource constraints, the study cohort is relatively small, potentially affecting the strength of association between the two variables. In addition, the highest CFS score observed was 5, which may be because those with higher CFS scores were deemed too high risk for surgery and therefore not referred for CPET. Regardless, this limits the ability of the study to assess correlation between CFS and CPET in the most frail of patients. Finally, although understanding of the relationship between CFS scoring and CPET performance may be of academic interest, successful adoption of CFS scoring as a surrogate for CPET would rely on CFS scoring providing accurate estimation of peri-operative risk itself, rather than correlation with another risk prediction tool. Whilst there is emerging evidence [

12] that increased frailty (as assessed using CFS scoring) is associated with worsened post-surgical outcomes, in our cohort we were unable to demonstrate an association between CFS and hospital length of stay, and only weak association with 1 year mortality. Larger studies will be required to assess the true predictive power of CFS score for perioperative mortality risk.

5. Conclusions

Our data suggests a weak signal between CFS score and CPET results. Further investigation with larger datasets is required to explore the merit of CFS as a surrogate for CPET testing and its use as an independent predictor for perioperative outcomes. This study supports the limited literature available.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, AH,LH. methodology, AH,LH.; data curation, MR.; writing—original draft preparation, AH,MR,LH.; writing—review and editing, AH,LH,MR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Dr R Kennedy (Consultant Anaesthetist, University Hospitals Sussex, UK).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A.

Best fit line (blue) by minimizing the sum of squared residuals. Shaded area (grey) represents the 95% confidence interval.

Best fit line (blue) by minimizing the sum of squared residuals. Shaded area (grey) represents the 95% confidence interval.

References

- Moran, J.; Wilson, F.; Guinan, E.; McCormick, P.; Hussey, J.; Moriarty, J. Role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing as a risk-assessment method in patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26787788/. 2016, 116, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennis, P.J.; Meale, P.M.; Grocott, M.P.W. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the evaluation of perioperative risk in non-cardiopulmonary surgery. Postgrad Med J Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21693573/. 2011, 87, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, T.; Bates, S.; Sharp, T.; Richardson, K.; Bali, S.; Plumb, J.; et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) in the United Kingdom-a national survey of the structure, conduct, interpretation and funding. Perioper Med (Lond) Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29423173/. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.; Shulman, M. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing and Other Tests of Functional Capacity. Curr Anesthesiol Rep Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8605465/. 2022, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://cpoc.org.uk/sites/cpoc/files/documents/2021-06/Preoperative%20assessment%20and%20optimisation%20guidance.pdf.

- Riedel, B.; Li, M.H.G.; Lee, C.H.A.; Ismail, H.; Cuthbertson, B.H.; Wijeysundera, D.N.; et al. A simplified (modified) Duke Activity Status Index (M-DASI) to characterise functional capacity: a secondary analysis of the Measurement of Exercise Tolerance before Surgery (METS) study. Br J Anaesth Available from: http://www.bjanaesthesia.org.uk/article/S0007091220304621/fulltext. 2021, 126, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parini, S.; Azzolina, D.; Massera, F.; Garlisi, C.; Papalia, E.; Baietto, G.; et al. Comparison of frailty indexes as predictors of clinical outcomes after major thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38883684/. 2024, 16, 3192–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagard, K.; Leonard, S.; Deschodt, M.; Devriendt, E.; Wolthuis, A.; Prenen, H.; et al. The impact of frailty on postoperative outcomes in individuals aged 65 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27338516/. 2016, 7, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16129869/. 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, M.; Mohammed, K.; Kasivisvanathan, R. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Versus Frailty, Measured by the Clinical Frailty Score, in Predicting Morbidity in Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Cancer Surgery. World J Surg Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32935139/. 2021, 45, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett, D.Z.H.; Jack, S.; Swart, M.; Carlisle, J.; Wilson, J.; Snowden, C.; et al. Perioperative cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET): consensus clinical guidelines on indications, organization, conduct, and physiological interpretation. Br J Anaesth Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29452805/. 2018, 120, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snitkjær, C.; Jensen, L.R.; Soylu, L.; Hauge, C.; Kvist, M.; Jensen, T.K.; et al. Impact of clinical frailty on surgical and non-surgical complications after major emergency abdominal surgery. BJS Open Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38788680/. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Patient demographics and co-morbdities, n=174.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and co-morbdities, n=174.

| Domain |

Median(IQR) |

|

| Age |

73.8 (69.0-79.0) |

|

| Male |

70% (n=121) |

|

| Ischaemic heart disease |

18% (n=32) |

|

| Atrial fibrillation |

14% (n=25) |

|

| Stroke/ TIA |

8% (n=14) |

|

| Diabetes |

23% (n=40) |

|

| Heart failure |

7% (n=12) |

|

| COPD |

16% (n=27) |

|

| Hypertension |

45% (n=79) |

|

| |

|

|

Table 2.

Surgical procedure, n=174.

Table 2.

Surgical procedure, n=174.

| Surgery type |

(n) |

| Cystectomy |

76 |

| |

| |

| Nephrectomy |

|

| 35 |

| Bowel resection |

|

| |

| |

| 36 |

| Lung resection |

|

| 8 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).