Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Space Radiation Environment

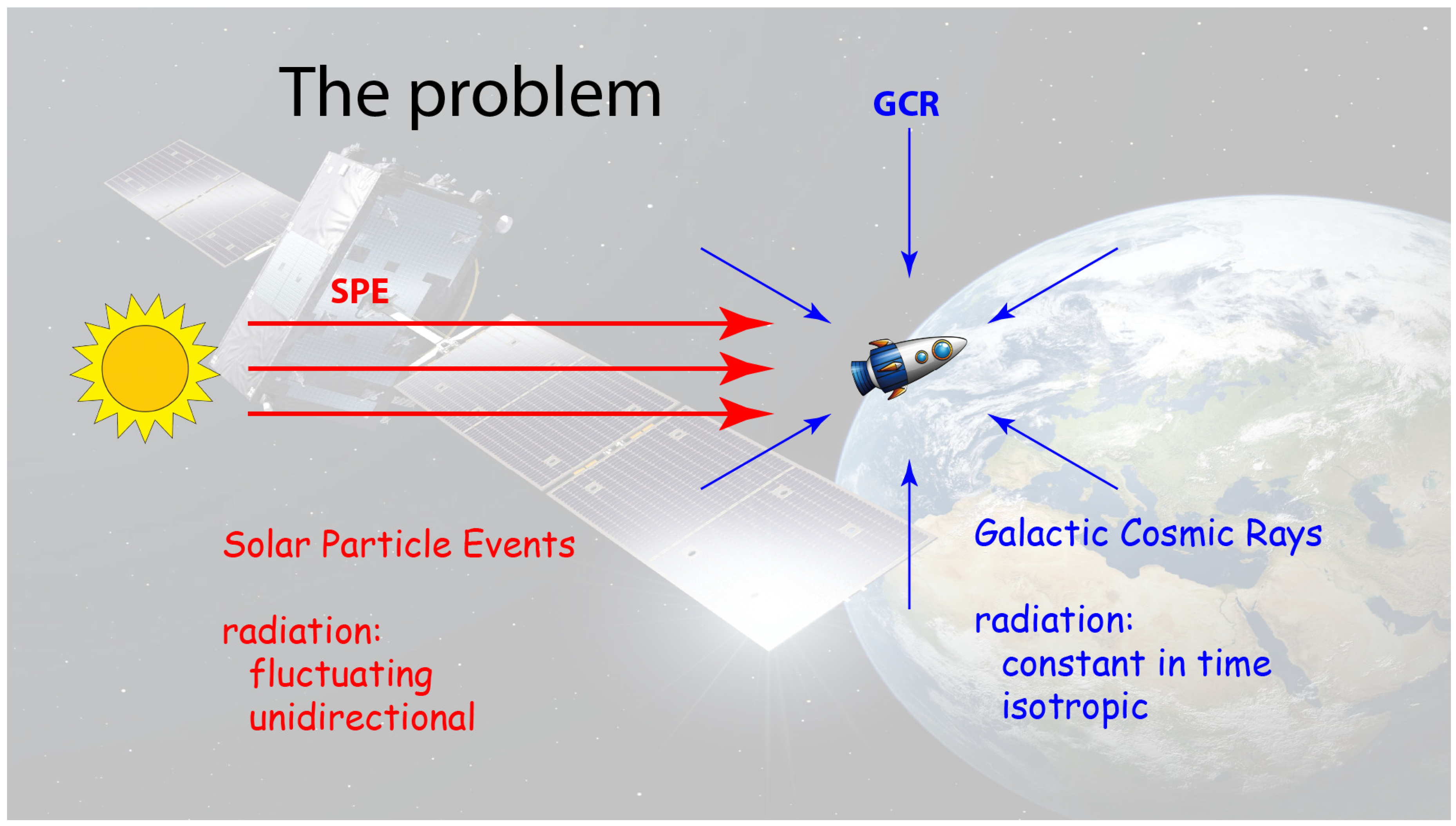

2.1. Galactic Cosmic Rays and Solar Particle Events

3. Space Radiation Protection

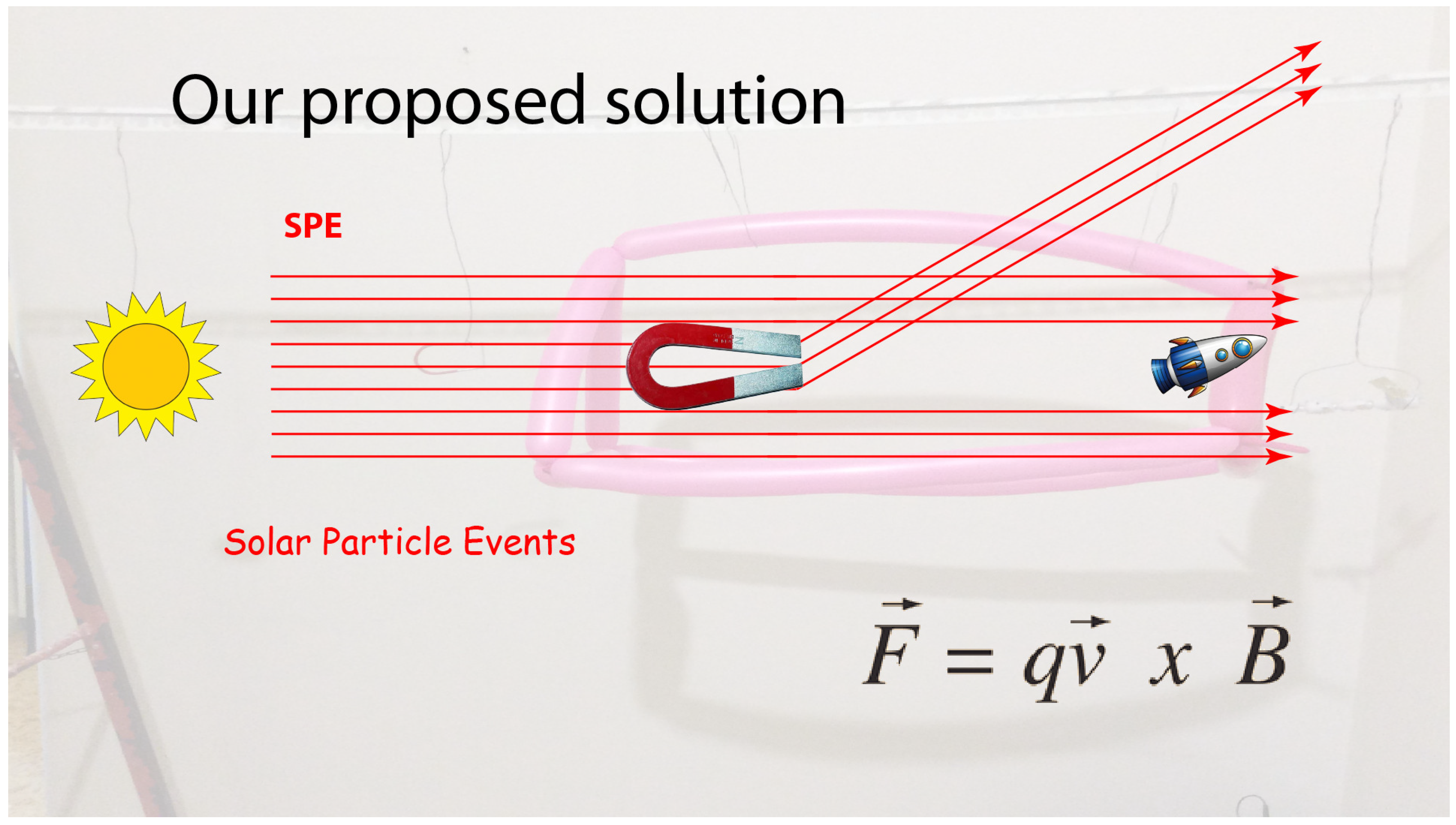

4. A Possible Magnetic Shield

5. Conclusions

References

- Roberto Battiston. The antimatter spectrometer (ams-02): A particle physics detector in space. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2008, 588, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto Battiston, Tipei Li, and Paolo Zuccon. Spacepart 2006. Nuclear Physics B (Proc. Suppl.) 2007, 166. [Google Scholar]

- James W Cronin. Cosmic rays: the most energetic particles in the universe. Reviews of Modern Physics 1999, 71, S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FA Cucinotta, H Nikjoo, and DT Goodhead. Model for radial dependence of frequency distributions for energy imparted in nanometer volumes from hze particles. Radiation research 2000, 153, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis A Cucinotta, Shaowen Hu, Nathan A Schwadron, K Kozarev, Lawrence W Townsend, and Myung-Hee Y Kim. Space radiation risk limits and earth-moon-mars environmental models. Space Weather 2010, 8. [Google Scholar]

- M Durante and FA Cucinotta. Nature rev. cancer. Cancer 2008, 8, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Marco Durante and C Bruno. Impact of rocket propulsion technology on the radiation risk in missions to mars. The European Physical Journal D 2010, 60, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco Durante and Francis A Cucinotta. Physical basis of radiation protection in space travel. Reviews of modern physics 2011, 83, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristine Ferrone, Charles Willis, Fada Guan, Jingfei Ma, Leif Peterson, and Stephen Kry. A review of magnetic shielding technology for space radiation. Radiation 2023, 3, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- editor J.Valentin. The 2007 recommendations of the international commission on radiological protection. Ann ICRP 2007, 37, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Myung-Hee Y Kim, Matthew J Hayat, Alan H Feiveson, and Francis A Cucinotta. Prediction of frequency and exposure level of solar particle events. Health physics 2009, 97, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RE McGuire, TT Von Rosenvinge, and FB McDonald. The composition of solar energetic particles. Astrophysical Journal, Part 1 (ISSN 0004-637X) 1986, 301, 938–961. [Google Scholar]

- Livio Narici, Marco Casolino, Luca Di Fino, Marianna Larosa, Piergiorgio Picozza, Alessandro Rizzo, and Veronica Zaconte. Performances of kevlar and polyethylene as radiation shielding on-board the international space station in high latitude radiation environment. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzo-Dolcetta F. Parisi, V. and L. Lunati. Towards protection form cosmic radiation via permanent magnets. in preparation 2024. [Google Scholar]

- W Schimmerling, JW Wilson, F Cucinotta, and MH Kim. Requirements for simulating space radiation with particle accelerators. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- P Spillantini, M Casolino, Marco Durante, R Mueller-Mellin, Günther Reitz, L Rossi, V Shurshakov, and M Sorbi. Shielding from cosmic radiation for interplanetary missions: Active and passive methods. Radiation measurements 2007, 42, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LW Townsend. Overview of active methods for shielding spacecraft from energetic space radiation. Physica Medica 2001, 17, 84–85. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).