1. Introduction

Machine learning (ML) has recently been applied in digital forensic investigation (DFI) and is still evolving; for example, Ref. [

1] designed a new framework known as IoTDots to help protect the data collected by various smart devices and applications. This features two primary components: the IoTDots analyser and the IoTDots modifier. The former scans the applications’ source code and detects forensic information. The latter automatically inserts tracking logs and reports the results.

The potential benefits of ML in DFIs are significant. These intelligent technologies have the power to support and significantly enhance the conventional DFI process. ML techniques can automate manual DFI processes, mainly when dealing with large volumes and diverse data. Leveraging these intelligent techniques increases the chances of identifying and successfully investigating cybercrimes in modern smart environments. This enables digital forensic (DF) specialists to reach the root cause quicker and more efficiently [

2].

For the aforementioned reasons, ML holds excellent potential for DFIs; however, it is a foreign field to most DF investigators, and the range for new research is vast. A minor research corpus uses ML technology to investigate digital crimes [

3].

According to Ref. [

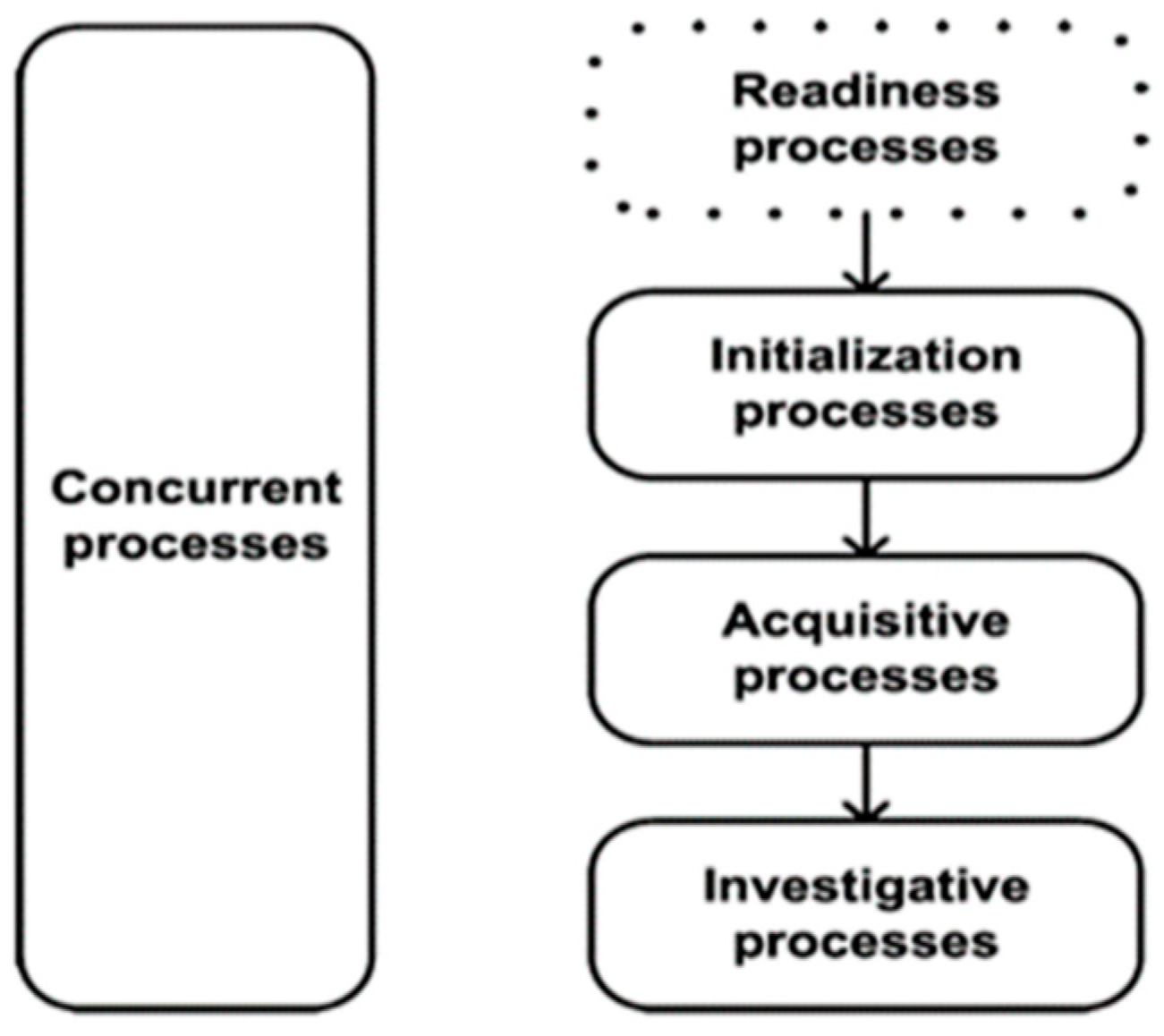

4], the state of the art in applying ML techniques in DFI within smart environments involving the initialisation and investigative processes suggests that ML techniques should be used more prominently in DFI’s readiness, acquisitive, and concurrent processes.

Machine learning (ML) techniques are used for prediction and classification; therefore, the acquisitive and concurrent processes in ISO/IEC 27043:2015 can be automated using ML techniques. These techniques will benefit the readiness and initialisation processes in this set of standards, which use decision trees and neural networks to predict and detect incidents.

Conversely, incorporating ML techniques can be robust for DFI; however, a lack of interpretability and inadequate training data may lead to powerless and improperly understood models [

3,

5,

6].

The remainder of this study is constructed as follows: Section II provides background on digital forensics, the ISO/IEC 27043 international standard on the DFI process, and ML. Section III presents a high-level of the proposed digital forensic readiness (DFR) model for smart environments. Section IV introduces the dataset and the steps applied in the implementation section—the subsequent section, section V. Section IV also presents a case study for this dataset used to apply ML techniques to implement the ML readiness model in the ISO/IEC 27043:2015 standard. Section V explains the detailed steps implemented in the dataset using Python. Section VI presents the study conclusion.

2. Background

The This section approaches digital forensics, the internationally standardised DFI process, and ML—all important concepts that the reader needs to consider in this paper.

2.1. Digital Forensics

Digital forensics (DF) is a more significant field of forensic science. DF investigators are responsible for retrieving and investigating data on digital devices. As these new and updated platforms collaborate with the Internet of Things ( IoT) and cloud technologies in smart environments, industry and practitioners struggle to develop DF strategies and procedures to envisage the challenges. These technologies could include embedded electronics or computing systems designed for specific functions, which might be integrated into a broader platform [

7].

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 27043 (ISO/IEC) 27043:2015 international standard captures a systematic and standardised process for incident investigation, with further details in the subsequent section.

2.2. ISO/IEC 27043

The ISO/IEC 27043 international standard was initially proposed by Valjarevic and Venter [

8] to direct DF incident investigation principles and processes [

9].

Error! Reference source not found. demonstrates a high-level overview of this ISO/IEC 27043 international standard.

Figure 1.

A high-level overview of the ISO/EIC 27043 international standard [

9].

Figure 1.

A high-level overview of the ISO/EIC 27043 international standard [

9].

The conventional DF process (i.e., the process followed before ISO/IEC 27043 was imposed) only concerned initialisation, acquisitive, and investigative processes; however, it comprised unharmonised disparate models; therefore, Valjarevic and Venter [

8] considered relevant models and other standards to direct the disparities and harmonise them into a single standardised model—ISO/IEC 27043. In addition to the harmonisation effort, Valjarevic and Venter [

8] added the readiness and concurrent process classes.

Since it has not been customised for IoT and smart environments, using the ISO/IEC 27043 DFI process within the smart environment remains challenging owing to the many IoT devices in this environment.

Applying ML techniques to enable automation and pre-incident prediction and detection will improve readiness processes in smart environments. A thorough awareness of the setups, data sources, and types will significantly reduce the time required for DFIs. Automating DFR processes will enable the automatic capturing and saving of digital evidence from smart environments based on predefined rules using a rule-based classifier and association rules. This should provide proactive and preventive methods for automation in such an environment.

Digital forensic readiness (DFR) principles ensure the forensic soundness of the information collected, which is suitable for litigation; therefore, ML techniques can be applied in the DFR process using noise-resistant algorithms, support vector machines, and neural networks. Using such ML techniques, investigators could deduce the classification rules from existing and historical datasets and scenarios to learn and train the readiness model. Clustering enhances classification accuracy and enables independent decision-making by the model.

The subsequent section presents a brief background of ML techniques.

2.3. Machine Learning

Applying ML in DF induced an innovative discipline known as ML forensics (MLF), which can detect criminal patterns, anticipate criminal activities (e.g. where and when crimes are inclined to occur), and automate DF investigative procedures. To conduct MLF, an adapted DF framework is required, which must be capable of capturing and analysing data in smart environments—even if devices in this smart environment are connected to the Internet through wired or wireless networking interfaces [

10].

Machine learning (ML) is an artificial intelligence (AI) approach that allows a system to learn independently from experience and examples rather than from programming. ML describes a system that continually learns and decides based on data rather than programming [

3]. ML is not only used for AI goals, such as simulating human behaviour but also to minimise human effort and time spent on complex and time-consuming jobs. ML techniques include supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning.

Supervised learning develops AI by training a computer program on labelled input data for a specific output. The model is trained until it recognises the fundamental patterns and correlations between the input and output labels, allowing it to produce appropriate labelling results when provided previously unobserved data. Supervised learning excels in classification and regression concerns. It aims to make meaning of data in a provided topic [

11]. Section III mentions that some researchers propose using supervised learning to improve DFIs in smart environments.

In contrast to supervised learning, unsupervised learning is presented with unlabelled data and is designed to detect similarity patterns on its own. Unsupervised learning techniques include clustering and association, which find all kinds of unknown patterns in data and help find features that can be useful for categorisation [

11].

Reinforcement learning differs from supervised and unsupervised ML techniques. The relationship between supervised and unsupervised techniques can be with the presence or absence of data labelling; however, reinforcement learning is an ML subfield concerned with how intelligent agents should behave in an environment. Markov models are used when the system being represented is independent and unaffected by an external actor [

12]. Markov chains are the simplest Markov model and represent systems where all conditions are observable. Markov chains display all conditions. Applications of this model include prediction. This probabilistic technique uses Markov models to predict the future behaviour of some variables based on the current state, and it can be used in several domains.

Conversely, ML influences DF, holding various applications in this sector. These applications can improve the efficiency of DFIs by attaining trends and patterns, similarities, anomalies, and other characteristics inside digital evidence; therefore, forensic professionals can produce leads and solve crimes in less time and with fewer resources. These advancements led to the second significant contribution of ML applications—a reduction in cost for a DFI [

13].

According to [

4], studies focus on the initialisation and investigative processes when automating ML tasks; however, the DFI process needs more attention to apply ML techniques in the readiness, acquisitive, and concurrent processes of the ISO/IEC 27043:2015 standard. This study focused on incorporating ML techniques into readiness; the acquisitive and concurrent processes remain subjects for future research.

The subsequent section presents the proposed DFR model for a smart environment.

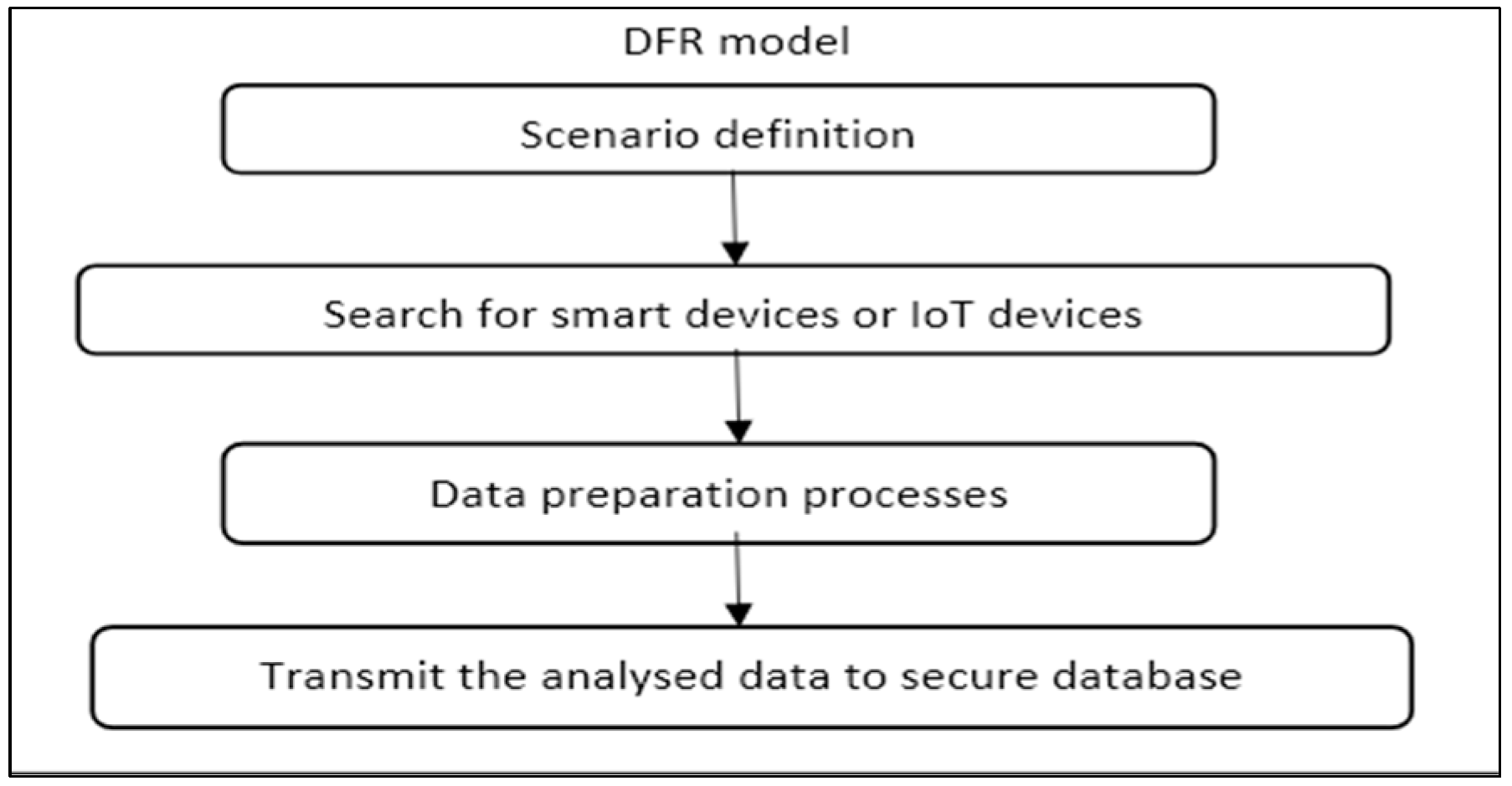

3. High-Level Digital Forensic Readiness (DFR) Model for the Smart Environment

This section presents a high-level or abstract observation of the DFR model, where the high-level model contains several “black boxes” expanded on in the subsequent sections. The IoT devices in a smart environment produce significant information, including potential evidence advantageous to the investigation. All necessary evidence must be collected and preserved to establish incident facts.

The proposed model must resemble a centralised model, connecting to IoT devices and components. This will enable the investigators to access the information when needed for an investigation in a smart environment. All processes and results in the model should be recorded and documented accurately.

The proposed model is unrestricted to a simple pre-incident process, such as ISO/IEC 27043 readiness processes; it is more than preparing for the environment and its data. It also includes an actual implementation for data capturing, transmission, analysis, and classification of potential digital evidence, representing a production of potential digital evidence. This is conducted by incorporating ML techniques to reduce unnecessary time consumption and for DF soundness purposes according to the smart environment’s complexity and changing landscape.

Figure 1 presents a high-level DFR model. The architectural framework for IoT-driven smart applications defines strategies to monitor and manage data, control, and process flows. These strategies ensure IoT device data within the smart environment supports service automation and data flow control. The data from the IoT devices involved in the investigation should be ready to approach. As mentioned, the proposed model is centralised, enabling the investigator to access the data in such interconnected environments through the processes mentioned in the model.

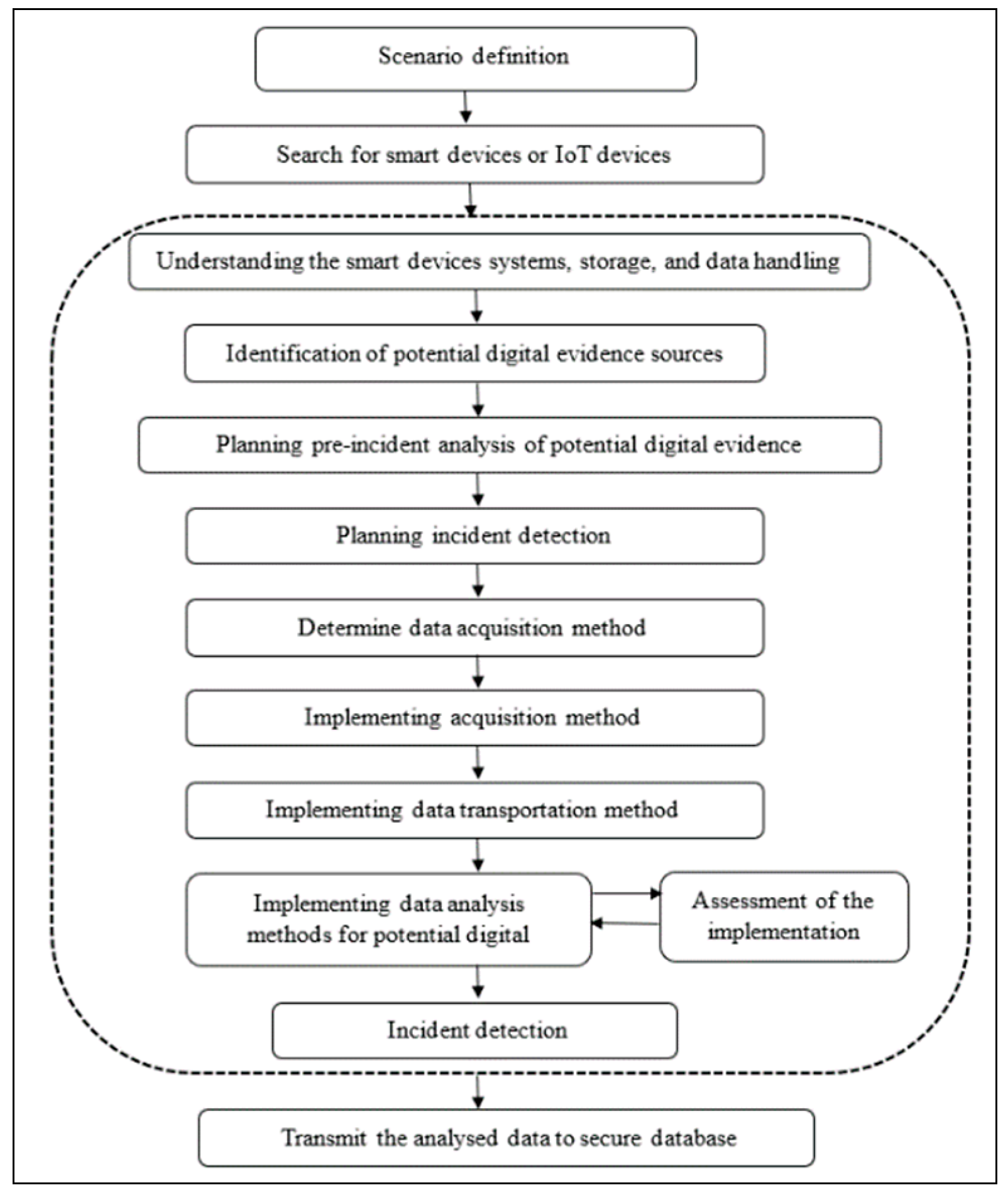

Figure 2 is an extension of

Figure 1; it details the data preparation processes delineated with a dashed line.

Figure 2 presents smart environment readiness processes, including the following:

Scenario definition. In this process, the investigator should define potential scenarios for the smart environment, including digital evidence. Several scenarios may warrant a DF investigation; for example, where will an investigator attain potential evidence sources when an incident occurs in a smart building? Such evidence sources might include information from environmental sensors, such as temperature sensors, smart cameras, and motion sensors, to indicate the occupation of the rooms during the incident.

Search for smart devices or IoT devices. In this process, the investigator must attempt to locate the smart devices controlling the specific smart environment. The investigator should explore physical devices, such as sensors and actuators, cameras, and control units; for example, in the smart building scenario, the investigator must attempt to disclose the available smart or IoT devices, such as sensors, smart locks, cameras, and any other devices comprising digital data.

Understanding smart device systems, storage, and data handling. The smart environment complicates identifying the potential digital evidence sources, as in conventional computer systems; therefore, this process focuses on understanding the specific environment by creating a broad representation of the particular smart environment according to the information from the previous process and a detailed overview, including technology, control units, and storage devices. This process also identifies the data type formats and how they can be approached; however, leveraging ML techniques, a smart library or database could gradually accumulate information from diverse devices and scenarios, enhancing an understanding of the device.

Identifying potential digital evidence sources. After comprehending the smart devices discussed in the preceding process, sources of evidence can be determined based on the specific scenario. At this stage, the investigator has a complete representation of the environment of the particular scenario; therefore, the output of this process will be a list of potential evidence sources; for example, evidence sources can be system logs, camera storage, voice recognition sensors/data, temperature sensors, carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration sensors, and occupancy sensors. Similar to the previous process, a repository of potential evidence sources from diverse devices could be developed to aid DF investigators in their work.

Planning pre-incident analysis of potential digital evidence. The DF investigator considers how to analyse the collected data best to produce valuable results. The DF investigator also decides on the analysis according to the identified scenario and potentially valuable techniques that might be needed in such an environment. This study proposes the proactive contribution of ML techniques, discussed in the hypothetical scenario section.

Planning incident detection. During this phase, the DF investigator considers how to track and detect the specific incident, assessing whether expert personnel or specialised devices are required for the case. At this stage, the DF investigator may also decide where the investigation should be conducted, such as in a sophisticated lab or whether a physical crime scene is involved; therefore, the crime scene can be traversed. This process should also determine what actions to take when an incident is initially established. This process’s results include specific procedures conducted when an incident is discovered, especially determining the data or information that must be collected or transferred to the rest of the DF process.

Determine data acquisition method. Most data acquisition during the DF investigation should be conducted using unique strategies and devices in DF labs. Data acquisition must be conducted meticulously to maintain forensic integrity. Performing this process within a DF lab is advantageous, attributable to the availability of sophisticated data acquisition strategies; however, owing to the characteristics of smart environments and their changing landscape, this study proposes a centralised DFR model. This model must be connected to smart devices in the specific environment and function as a live acquisition process; therefore, a live data acquisition process will capture live forensic images from the potential evidence sources, representing the original evidence. This is the most effective and defensible method for live acquisition cases. Then, other image copies of the live ‘original’ copy are created for further investigation; therefore, the ‘live original’ copy becomes the original.

Implementing acquisition method. As suggested in this study, implementing this process involves automating and connecting live forensic acquisition procedures for smart devices within the specific environment.

Implementing data transportation method. After implementing the data acquisition process, the investigator must decide how to transport the data. Data are transmitted digitally over the network, and data integrity and confidentiality must be maintained.

Implementing analysis methods for potential digital evidence. This process implements proactive analysis, such as applying the ML techniques proposed in the planning process on the collected data from the live acquisition process. Three ML techniques are used in the hypothetical scenario section.

Implementation assessment. This process confirms whether the implemented DFR processes meet the expected aims and requirements for the investigation. If changes are required, the DF investigator can return and realise them.

Incident detection. This process involves the output of the previous process, where a potential incident might be detected owing to pre-analysis implementation that might help detect the incident. This will then elicit the initial incident investigation process.

Transmit the analysed data to a secured database. This process transmits the results from the previous processes to a secured database to function as a smart library/database. It can more easily glean information from varied devices and scenarios to assist the DF investigator in future investigations. It also reduces the time and effort required to understand the incident and acquire and analyse the evidence.

Section 4 presents a case study for the smart building sensors dataset that applies ML techniques to implement the ML readiness model in the ISO/IEC 27043:2015 standard.

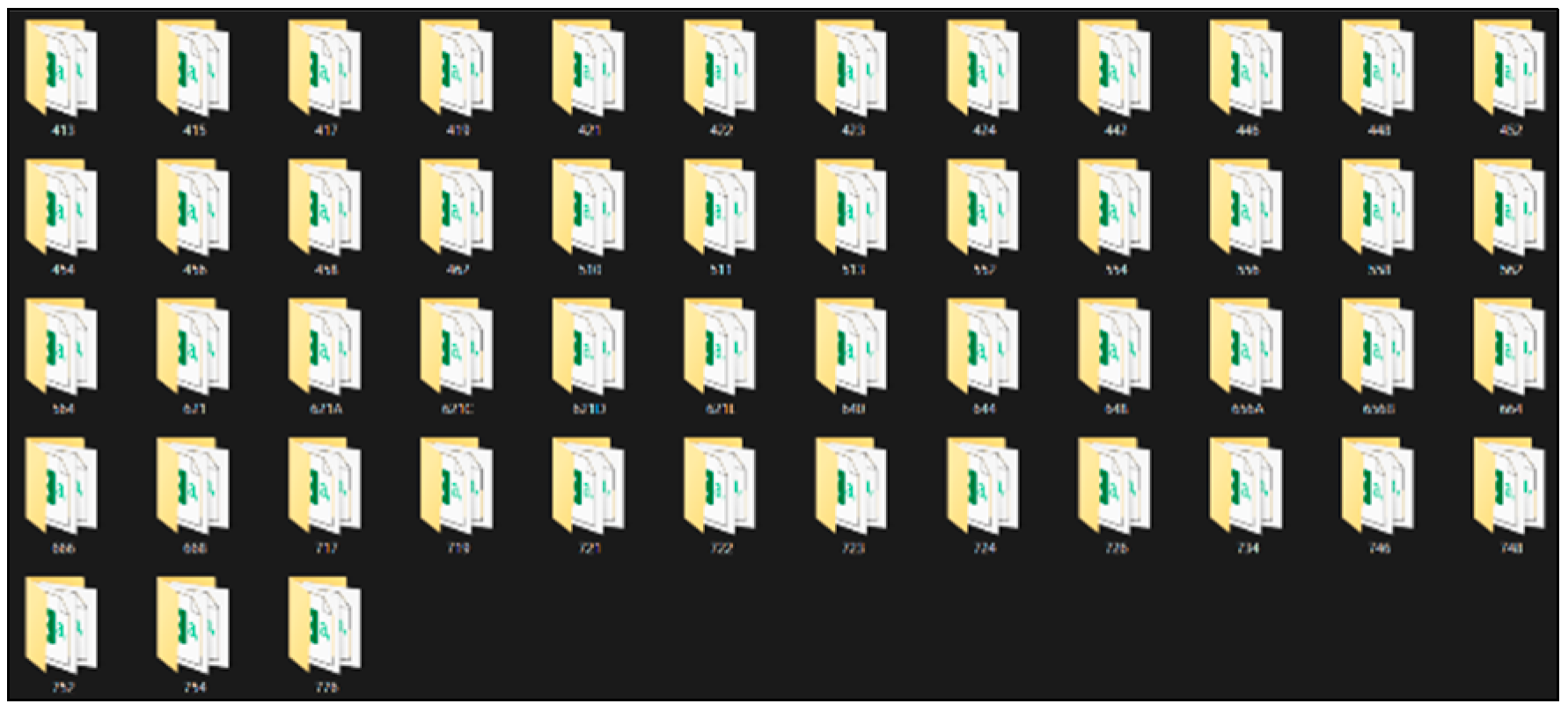

4. Smart Building Sensors Dataset

The smart building dataset was compiled from a case scenario comprising 255 sensors. A time series was recorded in 51 rooms over four Sutardja Dai Hall (SDH) floors at the University of California, Berkeley. This research used it to pursue patterns in a building’s room activities [

13]; therefore, ML algorithms can be implemented to automate and improve the readiness processes for smart environments. Some steps include data preparation, filtering, and classification.

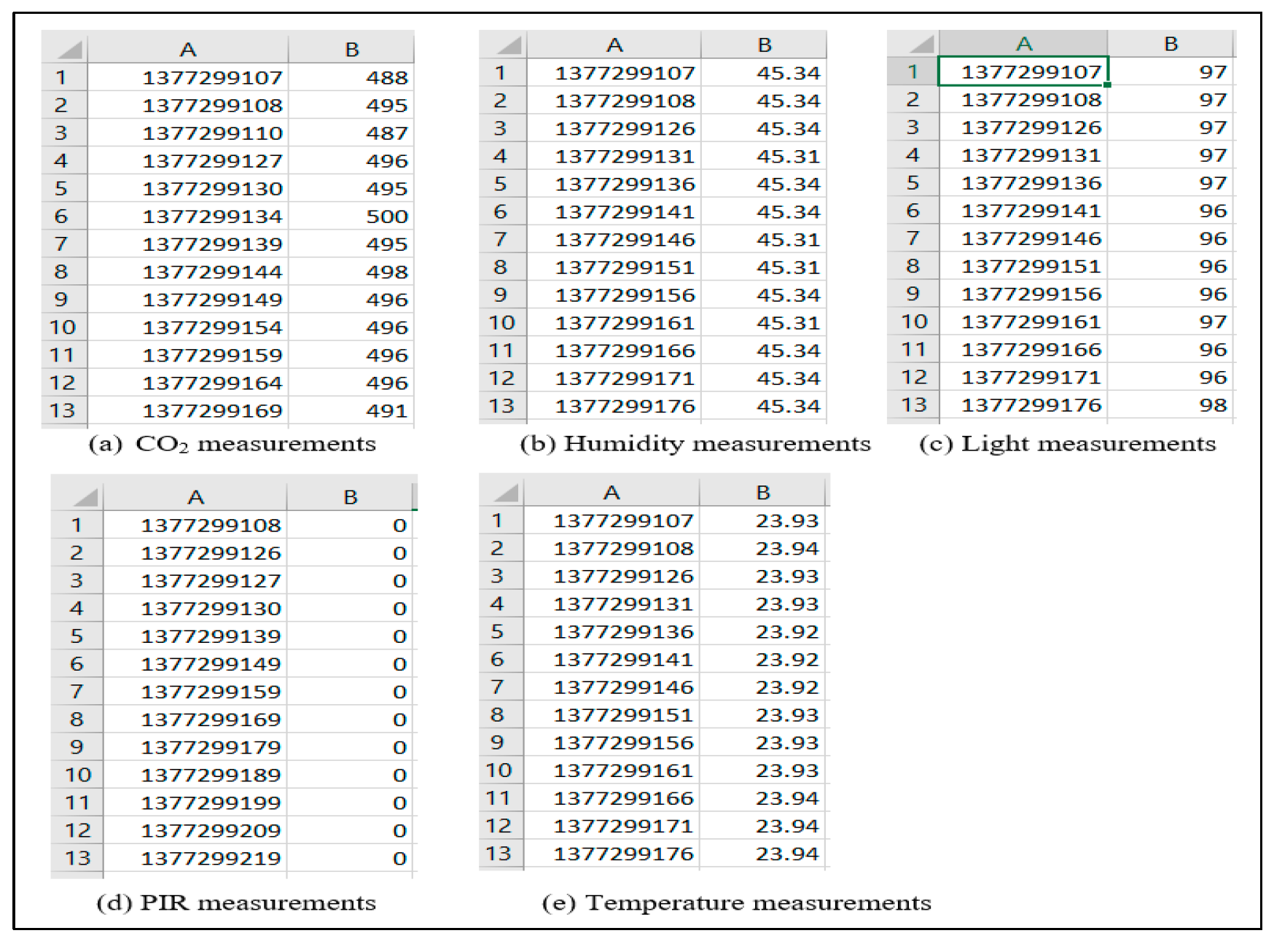

Each room includes five measurements: carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration, room air humidity, room temperature, luminosity, and passive infrared (PIR) motion sensor data, indicating the room’s occupation status. These measurements were collected over one week from Friday, August 23, 2013, to Saturday, August 31, 2013.

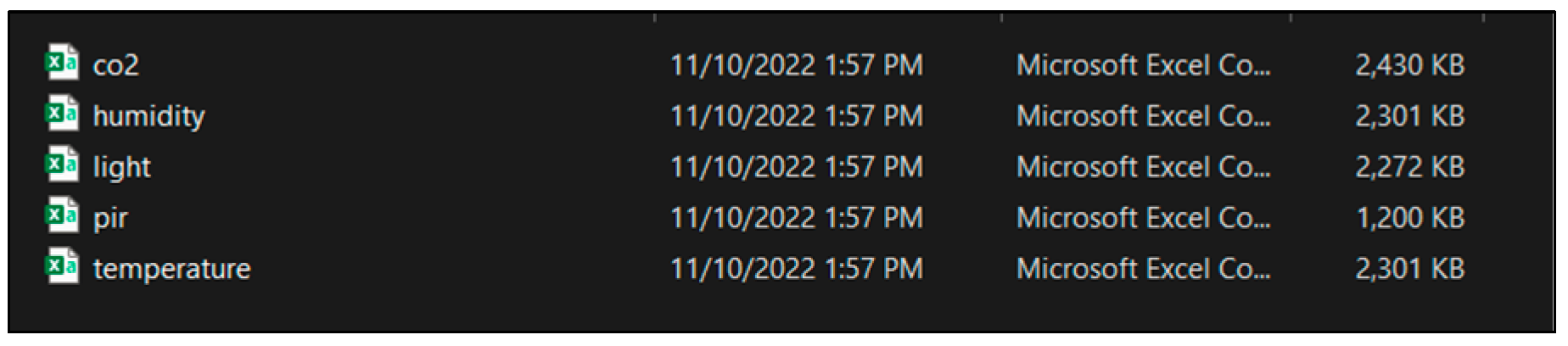

Figure 3 presents the dataset’s folder appearance. Each room has a folder named after its room number; each contains five measurement files (

Figure 4).

Each measurement file contains the actual readings of the sensors sampled every five seconds except for the PIR sensor, sampled every ten seconds. All measurements also contain timestamps—in Unix Epoch Time—a popular date and time encoding in computing. It is extensively used for databases, file systems, and computer operating systems. It calculates the number of seconds that have passed from 00:00:00 UTC on January 1, 1970, the start of the Unix epoch time.

Figure 5 presents a sample of data from the CO

2, humidity, light, PIR, and temperature files for room 413. Every file has two columns—the timestamp column and the actual readings from the sensor.

Below is a representation of the steps of exploratory data analysis (EDA) applied to the dataset using Python to understand the datasets by summarising their main characteristics. These steps are essential when modelling the data to apply ML. Each step of EDA applied to the dataset is explained in the next section.

Importing the required libraries for EDA.

Load the data into the data frame.

Checking the types of data.

Dropping irrelevant columns.

Renaming the columns.

Reducing the duplicate rows.

Reducing the missing or null values.

Plot distinctive features against one another (scatter) against frequency (histogram).

The subsequent section provides a more detailed explanation of the steps involved.

5. Implementation

The steps in the previous section are expanded in more detail in this section.

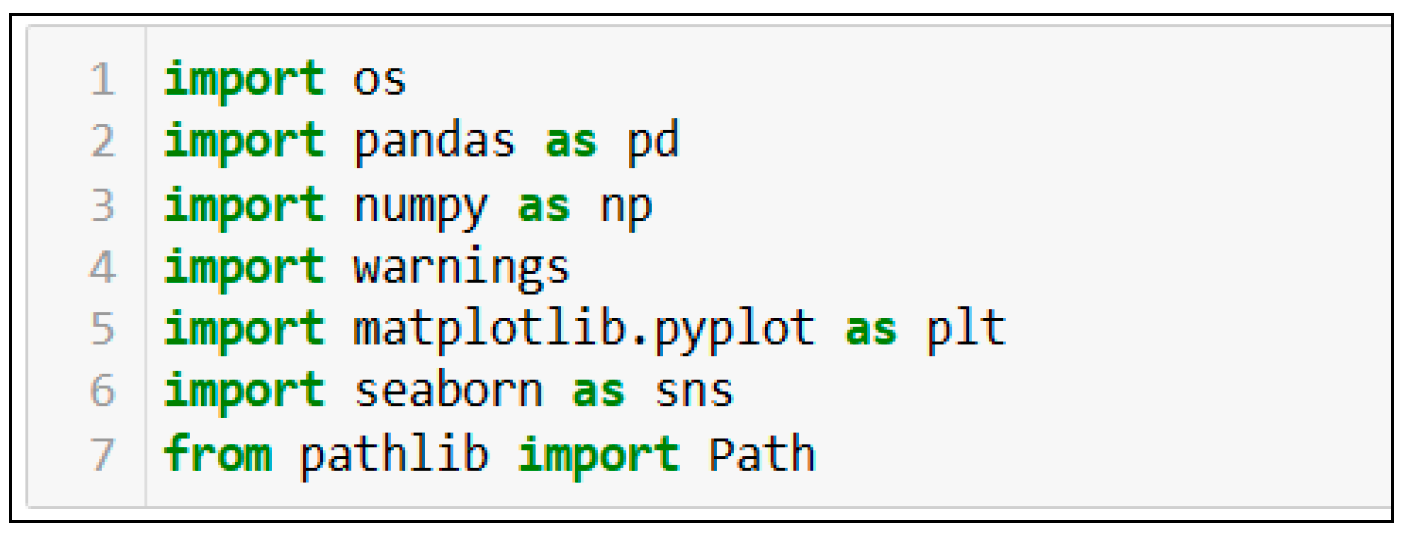

5.1. Importing the Required Libraries for Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Python libraries are a collection of pre-written programs that allow developers to select and use them in a computer program. These libraries offer an application programming interface (API), simplifying integration for developers within their software programs; for example, NumPy (numerical Python) is a library for interacting with arrays. It also has functions for operating in linear algebra, Fourier transforms, and matrices. The Pandas library primarily serves data analysis tasks, enabling the analysis of large datasets and drawing conclusions based on statistical theories.

Figure 6 presents an image of the Python code, demonstrating how to import libraries for the EDA used in this research.

After importing the required libraries, the dataset must be loaded into a data frame to start the analysis.

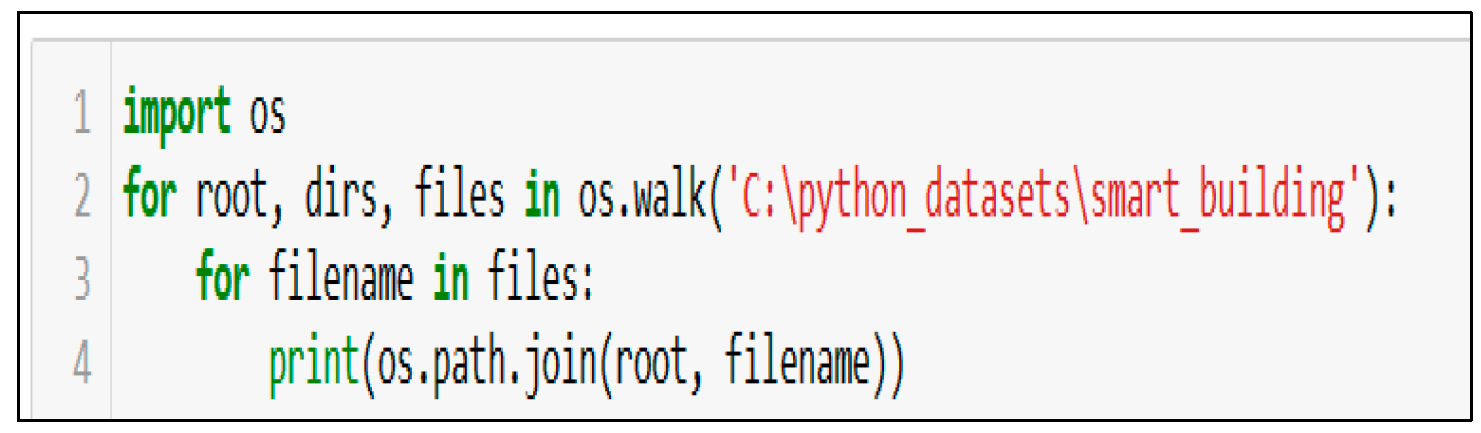

5.2. Load the Data into the Data Frame

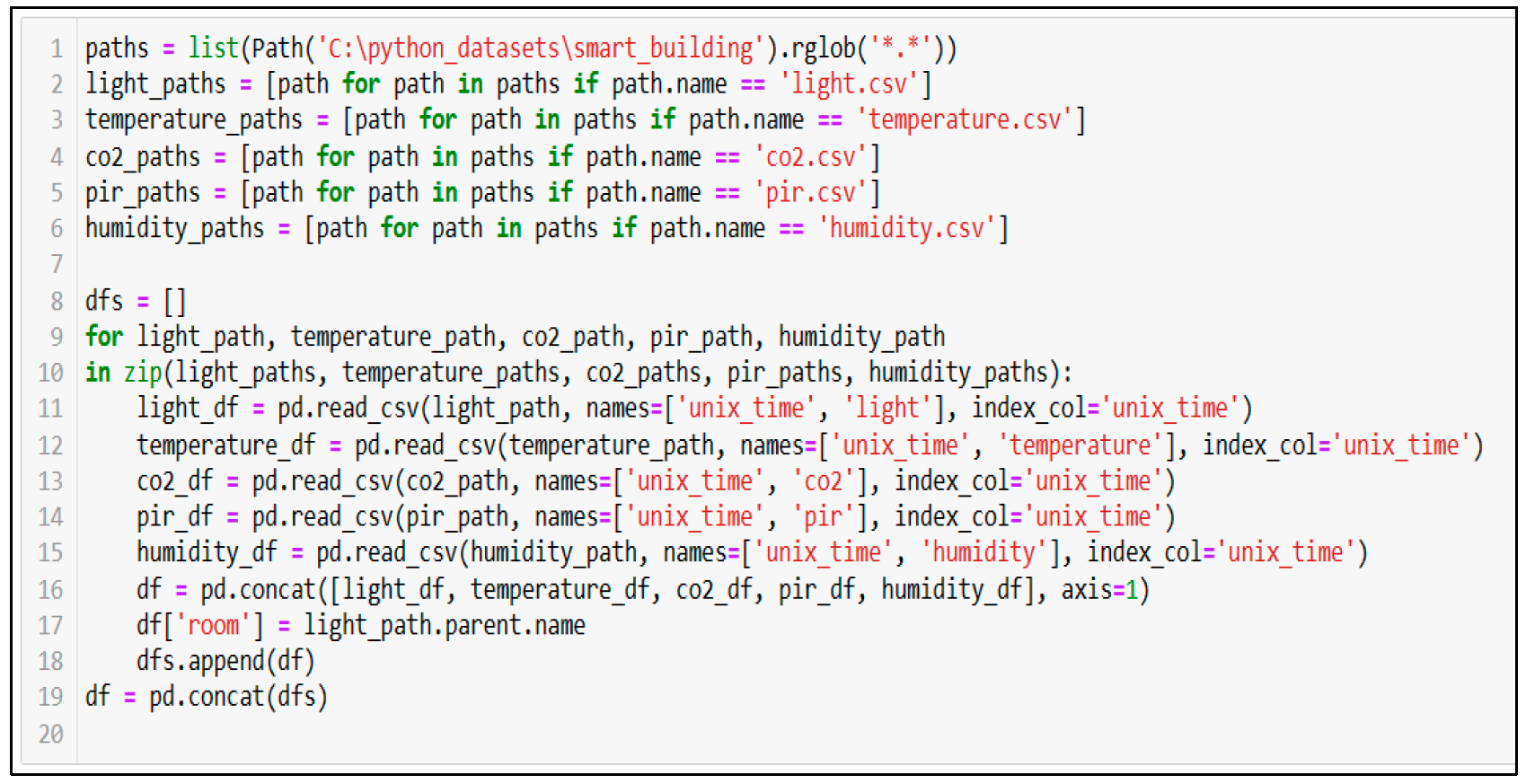

The smart building dataset is distributed in 51 folders containing five files.

Figure 7 illustrates how to ensure the program accesses and views the folders.

The output of the os. Walk method retrieves the file names in a directory tree of the dataset. The os. walk method helps to ensure that the program sees and accesses the dataset; then, the measurements and rooms folder files are merged into one data frame. A room number column is added as a new column to represent that each row of measurements belongs to a specific room number, as revealed in

Figure 8.

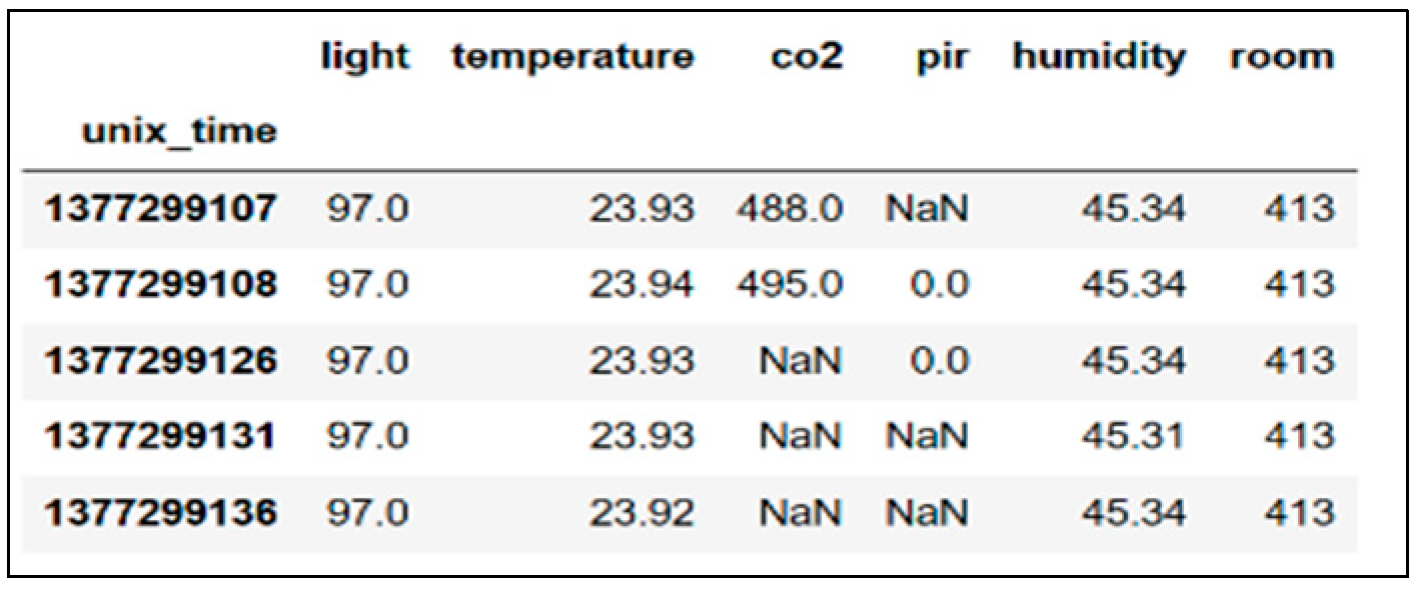

Figure 9 presents the output of merging files (room, CO

2, light, PIR, humidity, and temperature) into one data frame.

After the step involving loading the data into one data frame, some cells appear as null values—indicated by Not a Number (NaN)—because the PIR sensor is recording a value about the room occupation every ten seconds, unlike the other sensors that record values every five seconds, these null values will be checked and plunged in the fourth step of the EDA process. The ensuing step checks the data types as a step of the EDA process since the ML algorithms need a numeric data type and a new column (room) is added; therefore, the column data types must be assessed before applying ML algorithms.

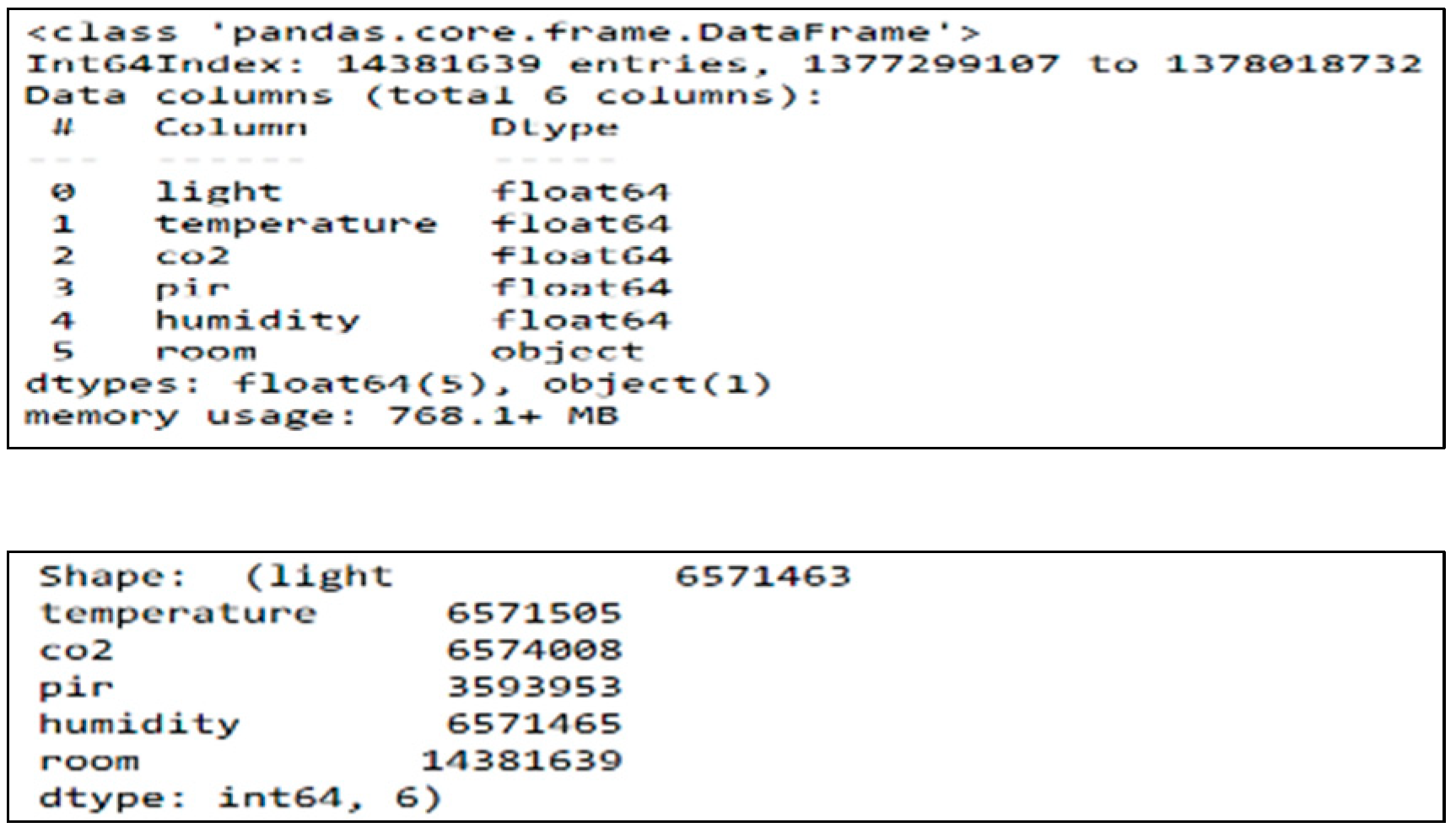

5.3. Checking the Data Types

The information method is used to check the data frame information. The information includes the number of columns, column names, column data types, memory used, and the count of non-null values in each column, as in Figure

10, the light, temperature, CO

2, PIR, and humidity columns are float number data types, but the room column is an object data type; this means it must be changed to a numeric value before applying ML algorithms.

Figure 10 also demonstrates the numbers of non-null values; for example, the temperature column has 6571505 values, but the PIR column has 3593953 values; this means that the PIR column contains null values that will be plunged in the next step of the EDA process.

Figure 10 demonstrates the value counts of columns in the data frame. The temperature, CO

2, PIR, and humidity columns have null values. Since the ML algorithms cannot accept null values, the next step is to plunge them.

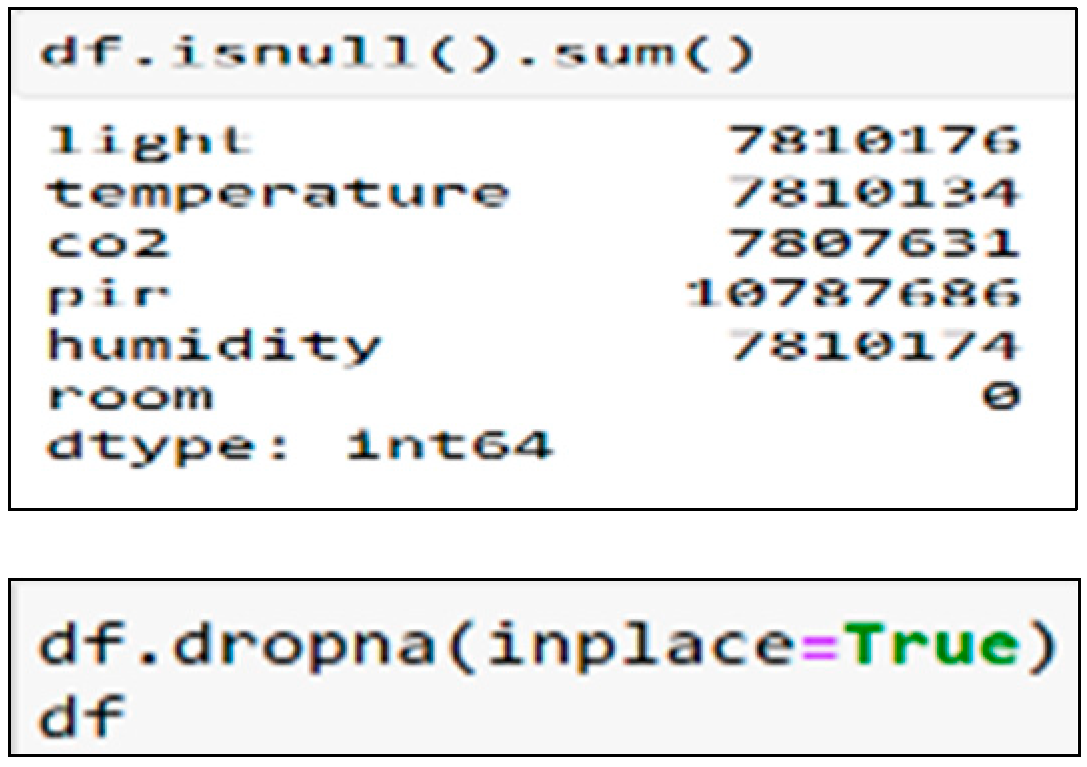

5.4. Plummeting the Missing or Null Values

The null method determines any null values in the data frame, as in

Figure 11. The figure also demonstrates the code for counting the null values using a null. sum. For example, the light column contains 7810176 null values, and the null values are plunged using the dropna method.

The dropna method deletes rows comprising null values. If the method is null, the sum is rechecked, and the columns’ output values become zero because no null values remain.

After this step, the data frame is ready for visualisation, which helps to acquire critical insights into the data and their correlations through diverse graphical representations.

5.5. Visualisation

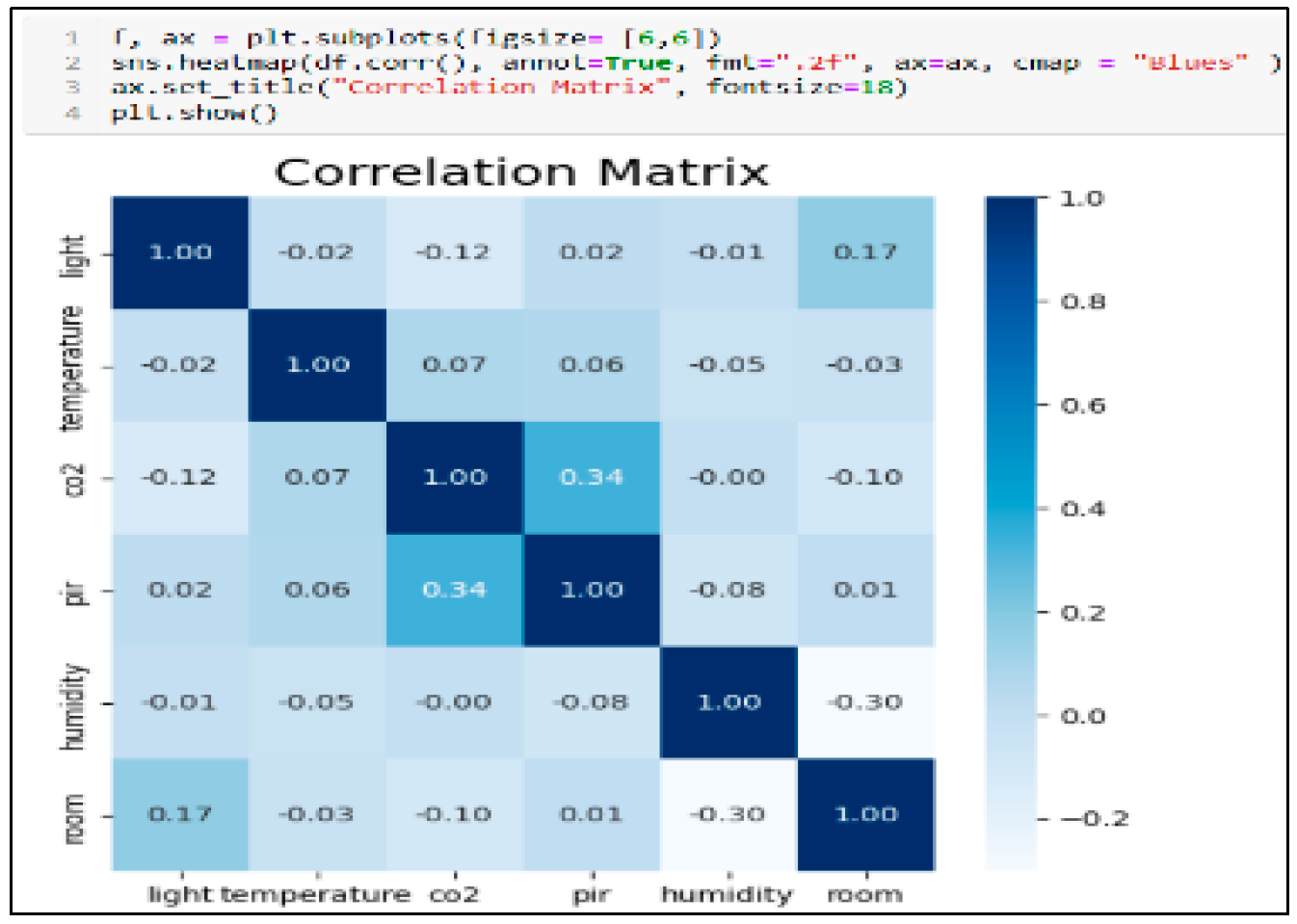

The heatmap method visually represents correlations within data, enabling the detection of patterns and relationships among values.

Figure 12provides an example of its application. In

Figure 12, the colour concentration reflects the relationship among values; therefore, the colour is darker.

For example, from

Figure 12, the CO

2 column has a correlation value of 0.34 with the PIR column. This figure provides insights into the interrelationships and mutual influence among values within the dataset; for example, the correlation between CO

2 and PIR indicates a positive relation, and the values in one column increased based on the values of diverse columns.

Figure 12 is a motivation for applying deep analysis using ML techniques to predict values based on additional features. Training the proposed readiness model can function intelligently in live forensic scenarios and indicate whether an incident has occurred.

The correlation matrix reveals the correlation coefficients among various variables. It provides insight into the relationships among all pairs of values, making it a powerful strategy for summarising large datasets and visualising patterns. Each cell represents the correlation between two variables; the value ranges between -1 and 1. If the correlation coefficient is more significant than zero, it is a positive relationship. Conversely, if the value is less than zero, it is an adverse relationship. A value of zero indicates that no relationship exists between the two variables.

After performing the EDA, the dataset can be used with ML algorithms, including clustering and Apriori algorithms.

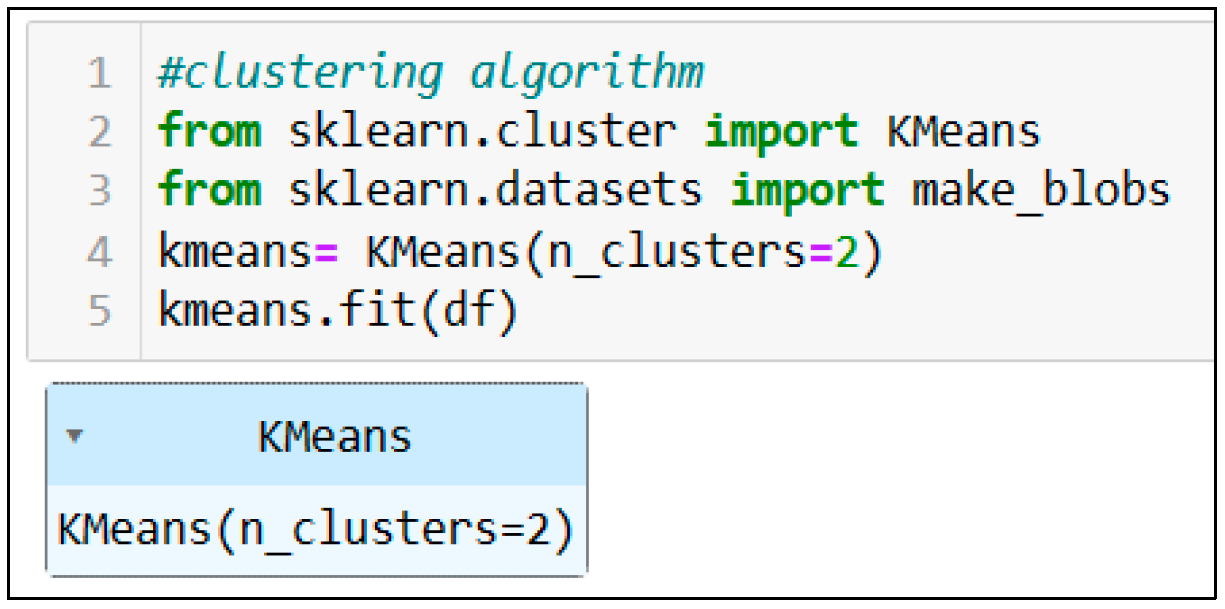

5.6. Appling Clustering Algorithm

K-means clustering is a famous and influential unsupervised ML algorithm. It is used to solve several complex unsupervised ML difficulties. A k-means clustering algorithm divides comparable items into clusters [

14]. The number of groups is represented by K.

Figure 13.

Clustering algorithm.

Figure 13.

Clustering algorithm.

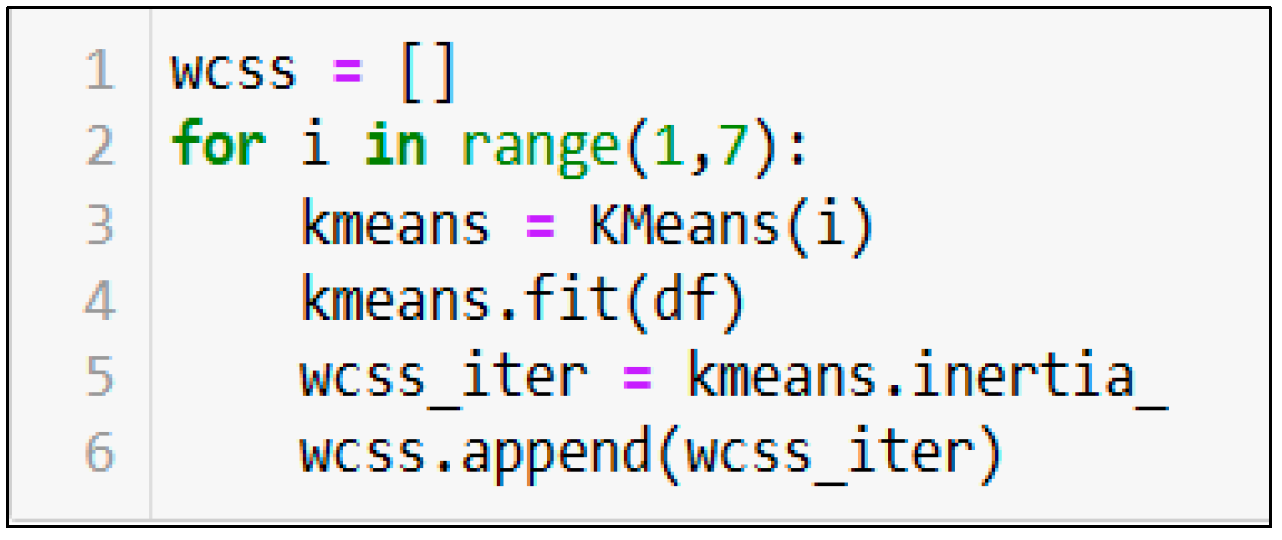

One of the most challenging tasks in this clustering algorithm is choosing the correct k-values. The elbow method is most famous for selecting the proper k-value and improving the model’s performance. It is an empirical method for discovering the best k-value. It selects a range of values and identifies the optimal by computing the sum of squared and average distances.

Figure 14.

Calculating the sum of the squares (the elbow method).

Figure 14.

Calculating the sum of the squares (the elbow method).

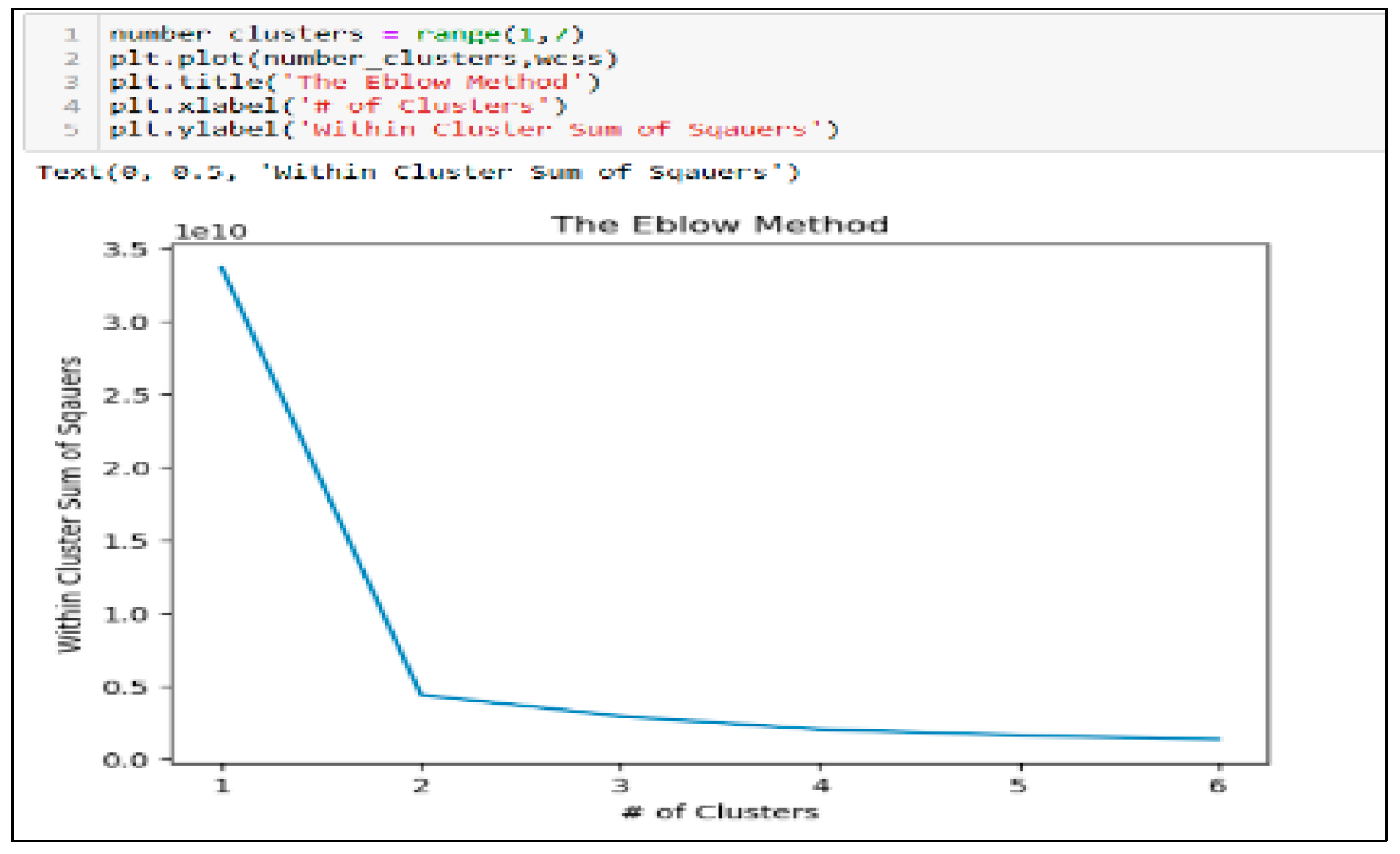

In conclusion, a graph is plotted between k-values and the within-cluster square to obtain the k-value. The graph was carefully examined. At some point, the graph decreased abruptly. That point indicates a k-value.

Figure 15.

Graphic deciding the elbow method.

Figure 15.

Graphic deciding the elbow method.

Clustering algorithms automatically group related data into clusters, but the proposed model requires an increase in the performance and quality of the clustering by combining it with a support vector machine (SVM).

5.7. Applying the Support Vector Machine (SVM) Algorithm

The support vector machine (SVM) is a supervised ML technique to classify data and estimate relationships among variables. This is a supervised method, indicating it requires initial training with labelled data [

15].

The model’s accuracy is improved when the SVM algorithm is applied with clustering. Also, SVM is effective with large-volume datasets and can effectively generalise in high-dimensional feature spaces. This functionality eliminates the requirement for feature selection, simplifying application classification. SVMs also have the benefit of being more robust than conventional approaches.

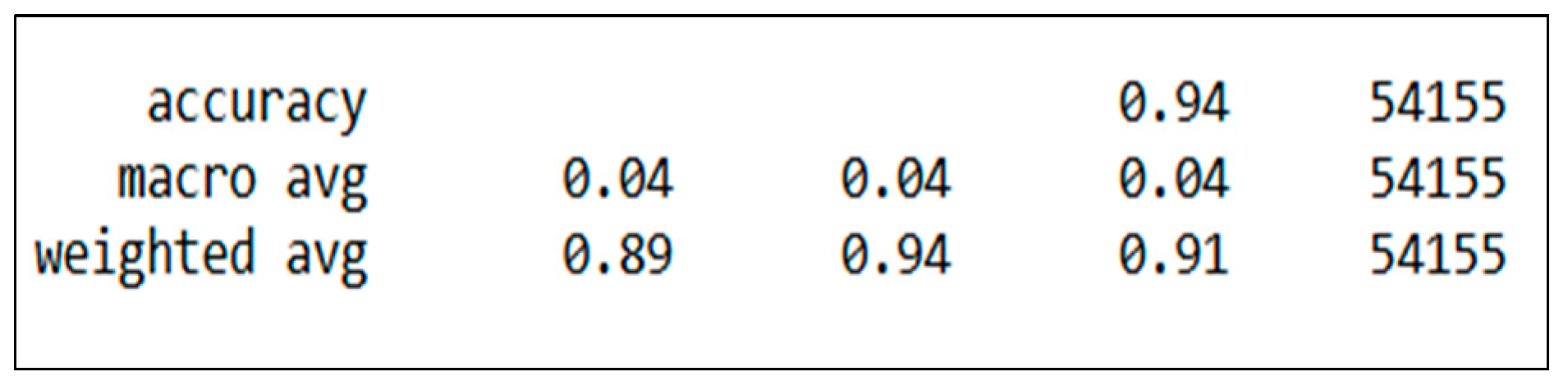

Figure 16 presents the accuracy of the model with the SVM algorithm.

The analysed data generated by the proposed model is transmitted and saved in a secure database that can function as a smart library/database built up over time to glean information more easily from diverse devices and scenarios to assist the DF investigator. The proposed model is an automatic and live forensic strategy, functioning proactively owing to the IoT environment’s needs. The proposed model is a learning model which improves over time based on the fed data.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the potential of integrating machine learning (ML) techniques into the ISO/IEC 27043:2015 standard to enhance digital forensic readiness in smart environments. The implementation of the readiness model underscores the effectiveness of automating manual processes and optimizing incident detection and response. By utilizing supervised and unsupervised ML algorithms, the readiness model provides a robust framework for pre-incident planning and analysis in complex IoT-enabled ecosystems.

The comparative analysis of Support Vector Machines (SVM) and clustering techniques reveals noteworthy insights into their performance in implementing the readiness model. Initially, clustering algorithms, specifically k-means, facilitated the organization of data into distinct groups, enabling the identification of patterns and relationships. However, the clustering approach showed limitations in precision and adaptability when dealing with high-dimensional datasets, a common challenge in smart environments.

In contrast, SVM, a supervised learning method, outperformed clustering by delivering higher classification accuracy. The combination of clustering with SVM further enhanced the overall performance by leveraging the strengths of both methods. Clustering provided an initial structure to the dataset, while SVM refined the classification process, ensuring a more precise identification of potential incidents. This hybrid approach emphasizes the importance of combining unsupervised and supervised techniques to achieve optimal results in digital forensic readiness.

The proactive use of ML techniques, as demonstrated in this study, allows investigators to detect anomalies and predict potential incidents in real-time, reducing response times and improving the efficiency of forensic processes. Despite these advancements, the integration of ML techniques into ISO/IEC 27043:2015 faces challenges, such as the need for large and diverse datasets and the interpretability of ML models. Future research should focus on addressing these limitations and exploring the applicability of other ML approaches, such as deep learning and AI, in digital forensic readiness.

5. Conclusions

The importance of ML in DFIs should not be underestimated since such intelligent technologies have the potential to support and significantly enhance the conventional DFI process. ML techniques can assist in automating manual DFI processes when analysing significant volumes and data. Using more intelligent techniques will increase the chances of identifying and successfully investigating cybercrimes in modern smart environments. This will assist data forensics specialists in determining the fundamental cause more quickly and efficiently [

2].

According to [

4], studies focus on initialisation and investigative processes when automating ML tasks; however, the DFI process needs more attention to apply ML techniques in the readiness, acquisitive, and concurrent processes of the ISO/IEC 27043:2015 standard. Provided the study’s focus on integrating ML techniques into readiness, further investigation into the acquisitive and concurrent processes remains a topic for future research.

This study presents a case study for the smart building dataset that applies ML techniques to implement the proposed ML readiness model in the ISO/IEC 27043:2015 standard. It compares the results of implementing ML techniques. These results display how smart environment data can be proactively analysed and classified, enabling investigators to access information when needed for an investigation in such environments.

References

- L. Babun, A. K. Sikder, A. Acar, and A. S. Uluagac, “IoTDots: A Digital Forensics Framework for Smart Environments”, Sep. 2018.

- V. R. Kebande, R. A. Ikuesan, N. M. Karie, S. Alawadi, K.-K. R. Choo, and A. Al-Dhaqm, “Quantifying the need for supervised machine learning in conducting live forensic analysis of emergent configurations (ECO) in IoT environments”, Forensic Science International: Reports, vol. 2, p. 100122, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100122. [CrossRef]

- X. Du et al., “SoK”, in Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, New York, NY, USA: ACM, Aug. 2020, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1145/3407023.3407068. [CrossRef]

- L. Tageldin and H. Venter, “Machine-Learning Forensics: State of the Art in the Use of Machine-Learning Techniques for Digital Forensic Investigations within Smart Environments”, Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 18, p. 10169, Sep. 2023, doi: 10.3390/app131810169. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Tok and S. Chattopadhyay, “Identifying threats, cybercrime and digital forensic opportunities in Smart City Infrastructure via threat modeling”, Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, vol. 45, p. 301540, Jun. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.fsidi.2023.301540. [CrossRef]

- H. Ismael Sahib, M. Qahatan AlSudani, M. Hasan Ali, H. Qassim Abbas, K. Moorthy, and M. Mundher Adnan, “Proposed intelligence systems based on digital Forensics: Review paper”, Mater Today Proc, vol. 80, pp. 2647–2651, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.007. [CrossRef]

- S. Watson and A. Dehghantanha, “Digital forensics: the missing piece of the Internet of Things promise”, Computer Fraud and Security, vol. 2016, no. 6, pp. 5–8, Jun. 2016, doi: 10.1016/S1361-3723(15)30045-2. [CrossRef]

- A. Valjarevic and H. S. Venter, “A Comprehensive and Harmonized Digital Forensic Investigation Process Model”, J Forensic Sci, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 1467–1483, Nov. 2015, doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12823. [CrossRef]

- A. Valjarevic, H. Venter, and R. Petrovic, “ISO/IEC 27043:2015 — Role and application”, in 2016 24th Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR), IEEE, Nov. 2016, pp. 1–4. doi: 10.1109/TELFOR.2016.7818718. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Qadir and A. Varol, “The Role of Machine Learning in Digital Forensics”, in 2020 8th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS), IEEE, Jun. 2020, pp. 1–5. doi: 10.1109/ISDFS49300.2020.9116298. [CrossRef]

- I. Goni, J. Mishion Gumpy, T. Umar Maigari, M. Muhammad, and A. Saidu, “Cybersecurity and Cyber Forensics: Machine Learning Approach”, Machine Learning Research, vol. 5, no. 4, p. 46, 2020, doi: 10.11648/j.mlr.20200504.11. [CrossRef]

- S. Iqbal and S. Abed Alharbi, “Advancing Automation in Digital Forensic Investigations Using Machine Learning Forensics”, in Digital Forensic Science, IntechOpen, 2020. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.90233. [CrossRef]

- A. Jarrett and K. R. Choo, “The impact of automation and artificial intelligence on digital forensics”, WIREs Forensic Science, vol. 3, no. 6, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1002/wfs2.1418. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Khairkar and M. D. A. Phalke, “International Journal on Recent and Innovation Trends in Computing and Communication Enhanced Document Clustering using K-Means with Support Vector Machine (SVM) Approach”, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://www.ijritcc.org.

- M. S. Patil, M. S. Bewoor, and S. H. Patil, “A Hybrid Approach for Extractive Document Summarization Using Machine Learning and Clustering Technique.” [Online]. Available: www.ijcsit.com.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).