Background

This case study describes how the Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS), an urban school system, experienced and responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and what actions BCPS took to mitigate the pandemic’s impacts on its students, faculty, and staff. Documenting these actions and the decision-making processes surrounding them identifies useful measures that may be useful for future pandemic planning, particularly for high-density, limited-resource urban school systems. BCPS currently consists of 160 schools with 75,811 enrolled students across K-12 grades. More than 90% of enrolled students are members of racial or ethnic minoritized populations (71% African American/Black, 18.6% Hispanic/Latino, 7.1% White, and <=5% Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Multiracial) and 72.1% of students are designated as low-income[

1].

Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schools

School systems around the world had to respond to challenging conditions during the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2023). At the height of the pandemic, nearly 1.6 billion students in more than 190 countries experienced education disruption due to school closures, equal to roughly 94% of the world’s student population[

2]. A systematic review analyzing the impact of COVID-19 education disruption observed an increase of inequalities in those who experienced learning loss[

2]. The long-term impact of learning loss may be significant, including that a “0.20 standard deviation decrease in standardized test scores could decrease future employment probability by 0.86%.” This exacerbates racial, socioeconomic, and other educational inequities[

3].

In addition to providing learning environments, public school systems, including BCPS, are a source of food and other critical services for students and their families[

4]. 30 million children depend on US schools for no cost or reduced-price meals[

5]. According to the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, while schools were closed, only 15% of low-income households with children who qualified for school meals received them[

5].

BCPS kept detailed records of COVID–related mitigation measures taken throughout the abbreviated 2019–2020 school year, and during the 2020–2021, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023 academic years. BCPS established multiple systems to collect and incorporate real-time information to determine how well intervention measures were working, and if necessary, rapidly update and revise policies to respond to changes in the pandemic and its student populations. As such, these systems provided well-documented examples of how public-school systems could respond to similar disease emergencies in the future.

The extent to which BCPS’s mitigation measures reduced COVID-19 transmission cannot be precisely determined, especially given the scarcity of data about similar measures undertaken by comparable school systems, but documenting the steps taken to reduce pandemic-related harms is important. This paper examines and documents some of those measures, including testing and contract tracing, masking, indoor air quality improvements, and other public health interventions. Describing these measures can provide insight into strategies to reduce school system and learning disruptions during future respiratory disease emergencies and pandemics.

COVID-19 Policies and Changes in Baltimore City Schools

The complete timeline for COVID-19 and BCPS is described in

Table 1, starting on March 5, 2020, when the first individuals in Maryland tested positive for COVID-19 and then-Governor Larry Hogan declared a state of emergency. On March 12, Maryland public schools were declared closed from March 16 through 27. The first COVID-19 case in Baltimore City was identified on March 14, and the first confirmed case of a 5-year-old child was identified on March 19. On March 25, the state extended public school closures for another month through April 26. To support students with remote learning, the state distributed 4,000 Chromebooks to students without devices and internet access[

6]. Laptops and hotspots were distributed with limitations at the district headquarters in July 2020. The hotspots were purchased through T-Mobile's EmpowerED 2.0 program, with the intent of supplementing internet access to students who did not already have access to in-home internet[

7].

Maryland extended school closures again to May 15 on April 17. On April 28, the Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association canceled sports for the remainder of the 2019–2020 academic year, and on May 6, the state closed schools for the remainder of the academic year. Under then-Governor Hogan’s Recovery Plan, all schools could reopen on August 27, 2020. Before the fall semester, BCPS distributed Chromebooks and hotspots once more in advance of the 2020-2021 school year[

8].

Once the first COVID-19 vaccines became available in late 2020, Maryland used a multiphase approach to delivery. In phase 1A, vaccines were available only for healthcare workers, first responders, and those in residential long-term care facilities. On January 18, 2021, Maryland moved into Phase 1B of the distribution plan, which expanded access to other populations at elevated risk of infection, including K–12 teachers, education staff, and childcare providers, prior to the public. Later phases included people in other essential roles and the public. By April 6, 2021, anyone aged 16 years and older could get vaccinated at a central mass vaccine site, and by April 12, they could be vaccinated at any provider. On May 12, vaccine access was expanded to younger adolescents[

9]. To encourage vaccinations, the state began advertising a VaxU Scholarship Promotion on July 7, 2021, which provided

$50,000 college scholarships to randomly selected vaccinated youth[

10].

As the 2021–2022 academic year began, BCPS resumed asymptomatic testing in September 2021 for staff and students as a continuation of the safe reopening plan[

11]. During the fall semester, vaccine access was rolled out for children aged 5–11 years old, completing the rollout of vaccines to school-aged children.

The Omicron variant was identified in Maryland on December 3, 2021, and the state announced a 30-day state of emergency on January 4, 2022, one day before in-person learning was scheduled to start for that semester[

9]. On February 25, Maryland updated its school face mask policy, leaving decisions to local authorities. Statewide, schools saw a decline in COVID-19 cases one month later. On March 30, 2022, BCPS sent COVID-19 tests home with students and staff ahead of their spring break[

6].

BCPS’s COVID-19 response services, including COVID-19 testing, COVID-19 related services, and COVID-19 related support to schools, ended as of June 13, 2023. BCPS now refers to COVID-19 questions and concerns to the Baltimore City Health Department[

12].

BCPS COVID-19 Protocols

Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic started, the Baltimore City Health Department established a Public Health Advisory Committee to develop protocols and make necessary decisions for the safety of the community, including its school system. This advisory committee was comprised of faculty members and experts from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Morgan State University, Johns Hopkins University (coauthor Gigi Gronvall served on this committee), and the Baltimore City Health Department. The BCPS website was updated frequently with policies and procedures for parents, students, and staff, based on recommendations from the advisory committee.

Phases of Reopening

BCPS established a 3-phase reopening plan in July 2020 with the intent of shifting between phases as the state of the pandemic changed. BCPS implemented the first phase, full virtual learning, at the onset of the pandemic, and included limited in-person services and access to student learning centers[

13].

The second phase, the longest-running phase, was a medium-term recovery phase utilizing a mix of in-person and virtual learning, with options to continue 100% virtual learning as needed. In cooperation with the Public Health Advisory Committee, and in accordance with local and national guidance, BCPS established and often reviewed health and safety measures. As of the 2024-2025 school year, the school system remains in the third phase, taking note of the pandemic as a “new normal” and featuring in-person learning with virtual components, as necessary.

Table 1 shows an overview of the timeline of COVID-19 related policies and changes in BCPS.

Social Distancing

BCPS established and followed social distancing protocols based on guidance from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), particularly in the early phases of the pandemic. Social distancing protocols, now known as physical distancing, suggested that students be placed at least 6 feet away from each other, and maintain that distance as much as possible.

At the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020, schools closed in-person learning, engaging only in virtual learning. Initial reopening plans were for August 2020 and were delayed by one month due to feedback from parents and students who were uncomfortable with reopening in August. When BCPS did reopen in September 2020 for the 2020-21 academic year with a hybrid plan, distance among students and staff was maximized as much as possible for students in person, with a virtual learning option for those who preferred at-home learning. This was based on CDC guidance around physical distancing to mitigate the spread of respiratory viruses[

14].

During the 2022–2023 school year, physical distancing for meals was not an active policy. Meals were served in the cafeteria; however, air scrubbers were installed for continuous air filtration while students were unmasked and eating.

As of the 2023–24 school year, based on current guidance, physical distancing is no longer recommended, and therefore not followed in the K–12 setting.

Masking

From the onset of school reopening on September 8, 2020, until March 14, 2022, BCPS required that students and staff wear protective masks or face coverings. Mask grade requirements were not established, but rules required masks to have a snug fit without gaps and cover both the nose and mouth. Guidance was provided on how to correctly use surgical masks/3 ply disposable masks and KN95 masks, and face shields were not considered sufficient substitutes for face coverings. BCPS provided masks for individuals who needed them.

If a parent/guardian sought accommodations for students with behavioral, mental, or physical conditions that prevented them from wearing masks, those accommodations were provided through the Equal Educational Employment Opportunity and Title IX Compliance Unit. Notably, however, accommodations were provided only after collaborative problem-solving efforts took place between parents and staff, and the district emphasized that as much as possible, mask-wearing skills should be developed and improved in students.

After March 14, 2022, masks became optional in most cases. However, they remained mandatory in the following situations: (1) for known contacts of a positive COVID-19 case, for 10 days after exposure; (2) for 10 days from the start of isolation for those who test positive; (3) for anyone who developed COVID-like symptoms while at school; and (4) for members of a K–8 grade cohort with a positive case.

Testing Policy and Case Tracking

BCPS required COVID-19 testing for students. BCPS partnered with two COVID-19 testing vendors, Concentric by Ginkgo and Shield T3, to establish three in-school testing programs to monitor and respond to outbreaks of COVID-19 at schools, as well as to surveil overall prevalence and case positivity[

15]. The three programs included diagnostic testing for individuals with symptoms, screening testing for individuals without symptoms, and testing for close contacts, explained in detail below. BCPS-provided COVID-19 testing ended as of June 13, 2023. Cases could be reported through the BCPS point-n-click reporting system until June 13, 2023.

Diagnostic Testing

Symptomatic diagnostic testing guidance included the following: if students or staff members began to feel symptoms, trained staff performed a rapid antigen test. If the individual had a positive test result, they were sent home to isolate for 5 days. A negative test result led to the school nurse determining whether the student was well enough to stay or needed to go home.

Asymptomatic Screening Testing

Screening testing occurred every other week during the 2022–2023 academic year. All students, regardless of vaccination status, were required to participate. If parents and guardians did not consent to free in-school testing, parents had to provide documentation of screening tests conducted at home. Individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 within the prior 90 days did not take part in screening testing.

Testing was done by pool testing: groups of staff and students self-administered swabs, and the samples were tested together. A positive pooled test indicated that at least one member of the group was infected with SARS-CoV-2. In this case, everyone in the group was then individually tested using a rapid antigen test. Any positive individual was sent home to isolate, and their class was required to wear masks for the subsequent 10 days.

Quarantine and Isolation

BCPS defined a classroom outbreak as three or more confirmed and associated COVID-19 cases among students, teachers, or staff within 10 days. Similarly, a schoolwide outbreak was defined as five or more classroom outbreaks (so long as the positive cases lived in different households), or at least 5% of unrelated students, teachers, or staff had confirmed cases within 10 days, with a minimum threshold of 10 positive individuals. When an outbreak occurred, the school community was notified through a letter and the state was informed. Masking protocols then went into effect.

Individuals who tested positive had to isolate for at least five days, with Day 0 being the date of the positive test. After Day 5, individuals could return to school if they did not have symptoms and had been fever-free for 24 hours. However, masking was required through Day 10, and if masking was not possible, students had to have a negative test on Day 5 or later to return prior to Day 11.

Indoor Air Quality Improvements

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2014 BCPS partnered with Johns Hopkins University through a grant provided by the Environmental Protection Agency to engage in a 4-year research program to assess how indoor and outdoor air quality can affect student achievement, health, and climate, and to document that impact[

17].

Phase I assessed all the public schools in Baltimore and determined if there was an association between air quality and student performance and health indicators. Phase II assessed whether schools had improved air quality after facility improvement, as compared to schools that had not yet undergone that facility improvement[

18].

Towards the end of the study, BCPS conducted a thorough review of each school building to ensure that their mechanical ventilation systems could receive and utilize MERV 13 filters. Where this was not possible, additional supplementary measurements were taken to ensure that portable filters could provide MERV 13 performance levels[

18]. These measures were taken in accordance with standards established by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), encouraging the combination of mechanical filters and HEPA air purifiers to mitigate aerosolized transmission of infectious disease. 81 schools received MERV 13 upgrades, and 67 schools received portable air purifiers[

19]. Each school was assessed for individual updates that included a combination of filter upgrades or air purification system installation. In many instances, air handlers supported common spaces only, such as school auditoriums, cafeterias, and libraries. As such, the units that serviced these spaces were upgraded with MERV 13 filters. MERV 13 and air purifier filters were changed quarterly, through a dedicated in-house district team. Funding for these improvements was designated by the school system[

19].

Conclusions from the project’s final report, written in 2019, found that BCPS school building conditions and environments were associated with student academic achievement and absence rates; renovation was associated with improvements in air quality and that those improvements in building conditions likely reduced exposures known to be harmful to student and staff health[

18].

Based on the project’s timelines and stated aims, BCPS took air quality’s impact on student and staff health seriously prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and went into the pandemic with a full understanding of the value of air quality improvements in potentially reducing COVID-19 infections and transmission amongst students and staff[

18].

Vaccination

BCPS did not establish mandatory vaccination for all students but strongly encouraged vaccination for anyone eligible (anyone aged 6 months and older) and provided information on available COVID-19 vaccines, including the dates and locations of free vaccination clinics, to parents and students[

20]. For the 2021-2022 academic year, high school student athletes participating in winter and spring sports were required to be vaccinated before the beginning of their season. High school students participating in fall sports were not required to be vaccinated.

To encourage student vaccinations, BCPS offered service-learning hours to middle and high school students who received an authorized COVID-19 vaccine. They would earn five hours of service for each vaccine dose, including the first two in the series and a booster, with a potential of 15 hours total[

21]. These hours counted toward the 75 service-learning hours required of all graduating high school students.

It is unclear whether this incentive increased the uptick in COVID-19 vaccinations among BCPS students, but the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS) did a study looking at the impact of incentives on COVID-19 vaccine uptick. NC DHHS offered a

$25 incentive to vaccine recipients or their drivers in summer 2021. During a one-week review, participating clinics saw only a 26% drop in vaccinations versus 51% in others. 41% of recipients cited the incentive as a key factor, and 49% mentioned having someone drive them as important[

22]. This impact was most notable among Black, Hispanic, and lower-income individuals.

Communication

BCPS established communication policies, with frequent updates reported through the BCPS Public Relations department and school administrators. Communications included updates to policies, notifications of outbreaks and cases to parents and students, resources for parents and students on vaccination and social services, and details on how parents could provide feedback or ask questions. The frequency of communications depended on the pandemic phase and COVID-19 case prevalence at individual schools. Guidelines for communication were established in the district’s standard operating procedure, with differentiation by school level.

Events and Extracurriculars

There were no specific limits delineated on indoor or outdoor gatherings; rather, the school engaged in transmission mitigation protocols to prevent super-spreader events. Students attending overnight field trips had to be vaccinated or participating in the school testing program. Student athletes were required to “participate in the new ‘Test-to-Play’ protocol for the 2022-23 school year,” meaning they had to participate in their school’s COVID-19 screening testing program[

23].

Reactions to Reopening

As BCPS investigated and finalized the protocols to allow for a return to in-person learning, there was ongoing debate on what a ‘safe’ reopening would look like and how it would be implemented. Leaders like then-Governor Larry Hogan, State School Superintendent Karen Salmon, and BCPS CEO Dr. Sonja Brookins Santelises faced economic and political pressures to reopen schools, citing data showing that Maryland’s students were falling behind academically and threatening legal action[

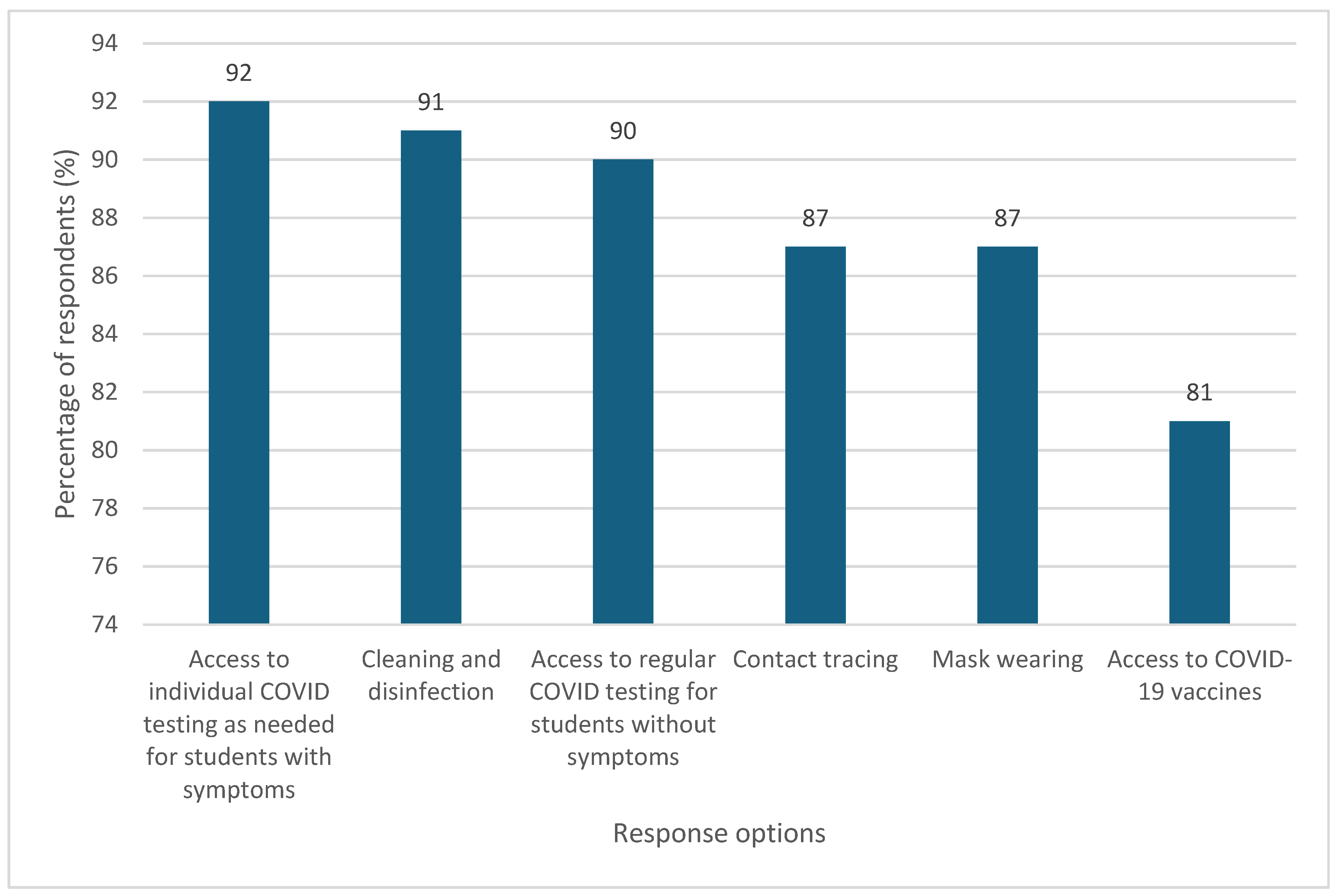

24]. Their safe reopening plan faced opposition from the Baltimore Teachers Union (BTU), and some parents and students, who felt more alignment was needed. This pressure led to several delays in reopening execution and mixed feelings when optional in-person learning began. Compared to the beginning of the 2021–2022 school year, the percentage of BCPS students who felt safe at school at the end of the school year dropped from 64% to 56%. A third of BCPS teachers and staff felt that BCPS was not doing what was necessary to support COVID-19 health and safety in schools. Parents felt that the COVID-19 safety protocols adopted by BCPS were important to their family feeling safe at school – with each protocol surveyed receiving an indication of importance from 81-92% of parents[

25].

Public Protests to Reopening

2020: #SafeNotSilenced and Political Pressures to Reopen

Once BCPS school re-opening conversations started after the initial lockdown, BTU began the #SafeNotSilenced reopening campaign. BTU is made up of 7,000 teachers, clinicians, paraprofessionals, and staff within the BCPS system[

26]. BTU shared concerns about the lack of funding available to reopen schools safely. The union highlighted safety concerns that predated the pandemic: “We did not have running water, functioning HVAC systems, proper staffing levels, technology, and cleaning materials before the crisis, and this exacerbates the challenge of reopening for Baltimore City in particular”[

27]. They also highlighted the “impossible choice between lives and livelihoods” for their students and families[

27]. BTU’s position was that “City Schools need to open virtually in the fall [2020] to protect human life, period. Only when the public health data demonstrates consistent, significant, and long-term downward trends, school facilities and public transportation are safe, the necessary resources and PPE have been procured, and the procedures and protocols have been fully worked out THEN we can consider shifting to a hybrid model.”[

27].

Then-Governor Hogan authorized all Maryland counties to reopen schools in August 2020[

9]. BTU organized a protest and petition, claiming it was not yet safe to reopen schools in Baltimore City. Before returning to in-person learning, BTU asked for the opportunity for all staff to be fully vaccinated, ventilation upgrade work to be completed, and a symptomatic and asymptomatic testing program be in place. In addition, they asked that schools meet minimum public health metrics (positivity and case rates) for at least a week before reopening[

28]. Due to the pressure applied to the school district, BCPS announced a delay in a return to full in-person instruction until March and April 2021, which the union declared a “victory” in its negotiations[

29].

2021:. Student Protests

There were several instances of student protests during this period. During a January 26, 2021 school board meeting, a BCPS high school senior and former student school board commissioner announced plans for a student strike. They asked students to continue with virtual learning until their demands, including access to vaccines and ventilation improvements, were met[

30]. This same group of students (Students Organizing a Multicultural Open Society) successfully pressured Comcast to double the internet speeds for its Internet Essentials broadband program to support virtual learning in March 2021[

31].

Starting in the 2021-2022 academic year, parents had a choice to register their students for in-person instruction or the Virtual Learning Program (VLP)[

32]. This continued into the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 academic years.

2022:. Return to in-person learning and #ResultsToReturn

Full in-person learning was set to start January 5, 2022, which was during the Omicron surge. The BTU started the #ResultsToReturn campaign, demanding that BCPS require that “all students and staff submit a negative covid result before reporting into school buildings regardless of vaccination status”[

33]. As part of that campaign, BTU issued a BCPS community survey asking: “Do you AGREE or DISAGREE with the demand that students and staff must submit a negative covid result before reporting into school buildings regardless of vaccination status?” 84.7% of the 930 responses strongly agreed or agreed with that statement[

33]. The 930 responses consisted of: 47.7% teacher or school staff, 25.2% Baltimore community member, 17.3% parent or family member, and 16.1% student[

33]. It is not clear if BCPS acted based on this campaign, as plans for full in-person learning (with the VLP option) continued.

Reflections on COVID-19 protocols as part of reopening for the 2021-2022 academic year

At the end of the 2021–2022 academic year, BCPS issued an end-of-year survey asking students, parents, teachers, and school administrators for reflections on school COVID-19 protocols for that academic year.

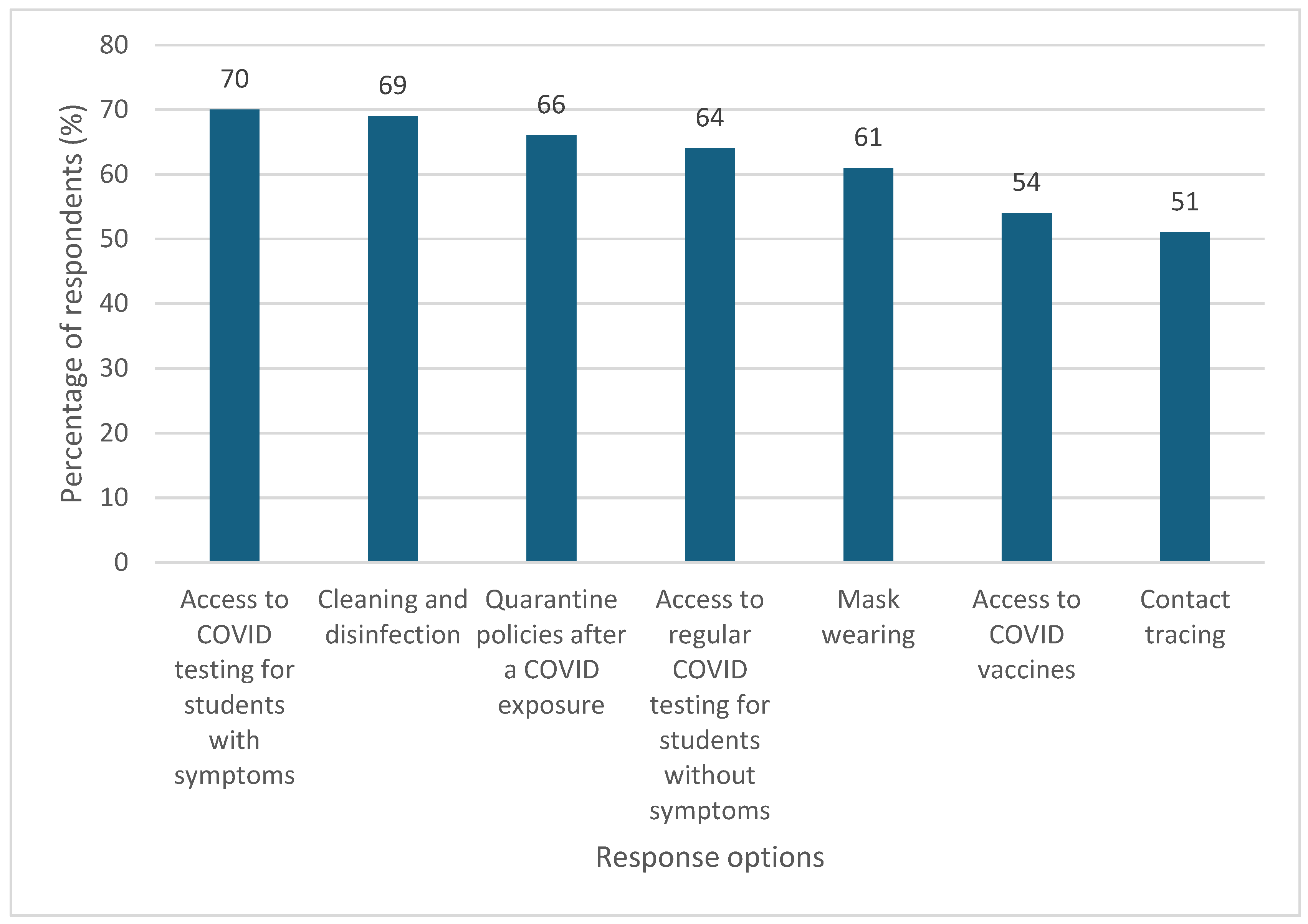

Students

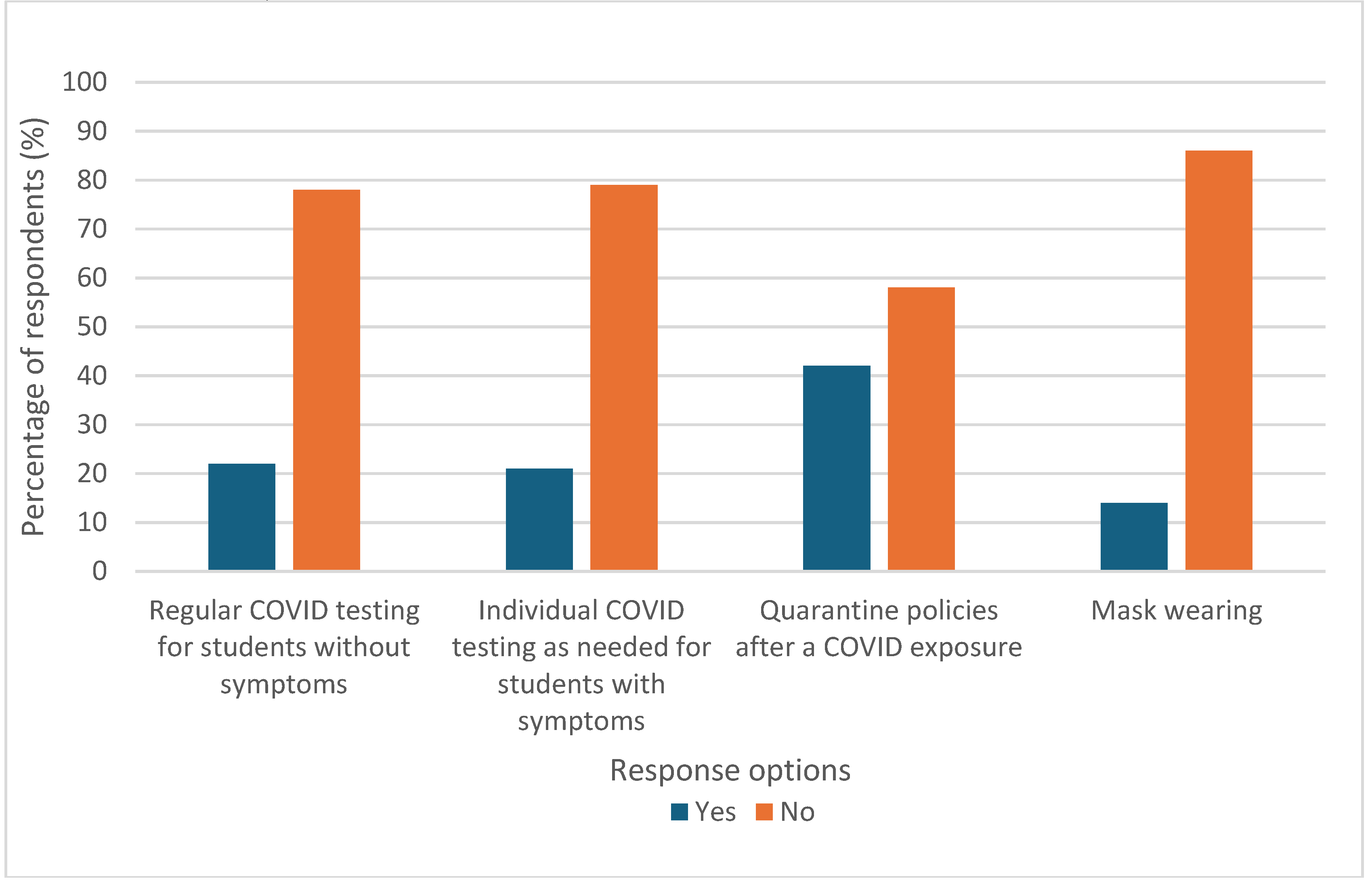

Students were asked “How important were the following school COVID safety measures to you feeling safe in school?”[

25]. Respondents could choose multiple answers.

Figure 1.

BCPS student responses to 2021-2022 end-of-year survey on protocol importance to “feeling safe at school”.

Figure 1.

BCPS student responses to 2021-2022 end-of-year survey on protocol importance to “feeling safe at school”.

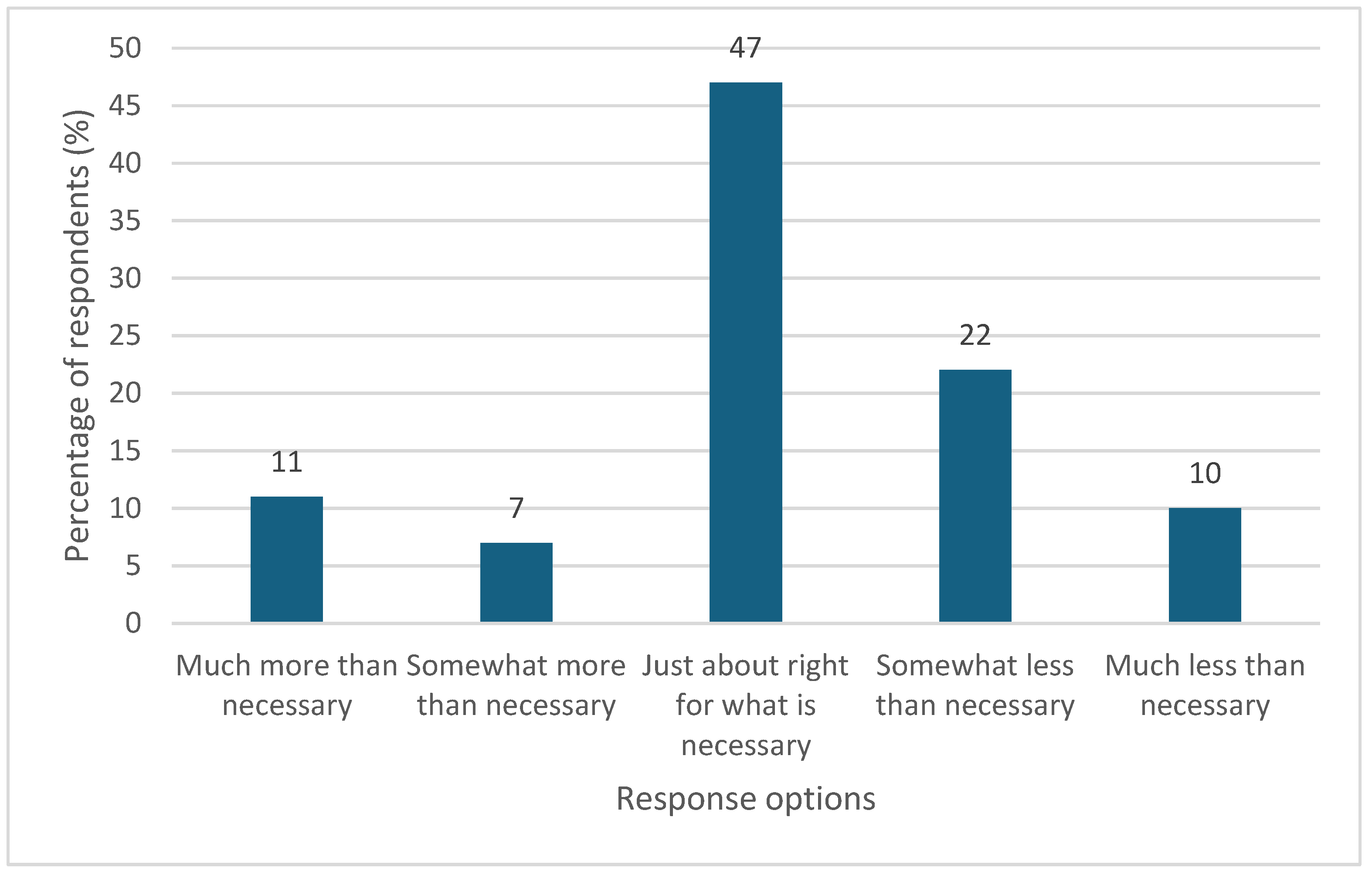

Teachers and Staff

Teachers and staff were asked to respond to “We are doing well in addressing what is necessary for supporting COVID health and safety in our schools”[

25]. Respondents could choose one answer.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents who chose specific response options to the question “We are doing well in addressing what is necessary for supporting COVID health and safety in our schools.”.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents who chose specific response options to the question “We are doing well in addressing what is necessary for supporting COVID health and safety in our schools.”.

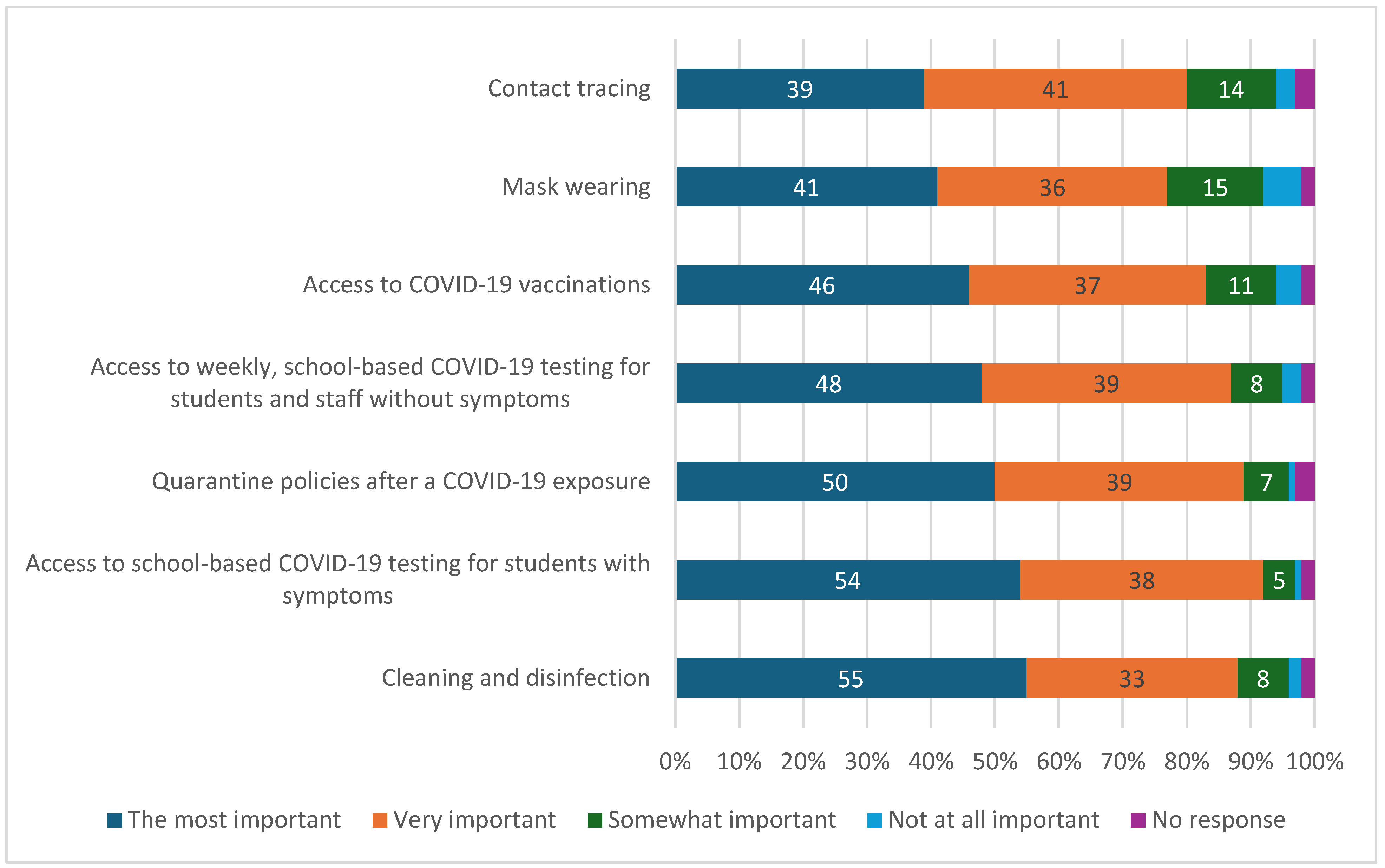

Teachers and staff were also asked to indicate the importance of the following COVID-19 health and safety protocols[

25].

Figure 3.

BCPS Teacher and Staff responses to 2021–2022 end of year survey question on COVID-19 protocol importance[

25].

Figure 3.

BCPS Teacher and Staff responses to 2021–2022 end of year survey question on COVID-19 protocol importance[

25].

82% of school-based support staff agreed that BCPS “current health and safety protocols related to COVID-19 are ‘just about’ or ‘more than’ or ‘much more than’ necessary”[

25]. 86% said they knew the appropriate protocols and procedures if they tested positive for COVID-19[

25].

School Administrators

School administrators were asked “How clear was communication from the district office about COVID-related safety measures and protocols”[

25]. 67% said that communication was “mostly clear” and 15% said it was “extremely clear”[

25].

Parents and Families

Parents and families were asked “How important were the following COVID safety measures to your family feeling safe in school?”[

25]. Respondents could choose multiple answers.

Figure 4.

Percent favorable BCPS parent/guardian responses to 2021–2022 end of year survey question on COVID-19 protocol importance to “their families feeling safe in school”[

25].

Figure 4.

Percent favorable BCPS parent/guardian responses to 2021–2022 end of year survey question on COVID-19 protocol importance to “their families feeling safe in school”[

25].

Additionally, parents were asked about how disruptive certain COVID-19 safety protocols were to their child’s learning.

Figure 5.

BCPS parent/guardian yes or no responses to 2021–2022 end of year survey question “… did each of the following COVID safety measures interrupt your child's learning?”[

25]. .

Figure 5.

BCPS parent/guardian yes or no responses to 2021–2022 end of year survey question “… did each of the following COVID safety measures interrupt your child's learning?”[

25]. .

Compared to the beginning of the 2021–2022 academic year, the percentage of families who ended the year feeling that there were opportunities to engage in decision-making and advocacy at their schools increased by 5%[

25].

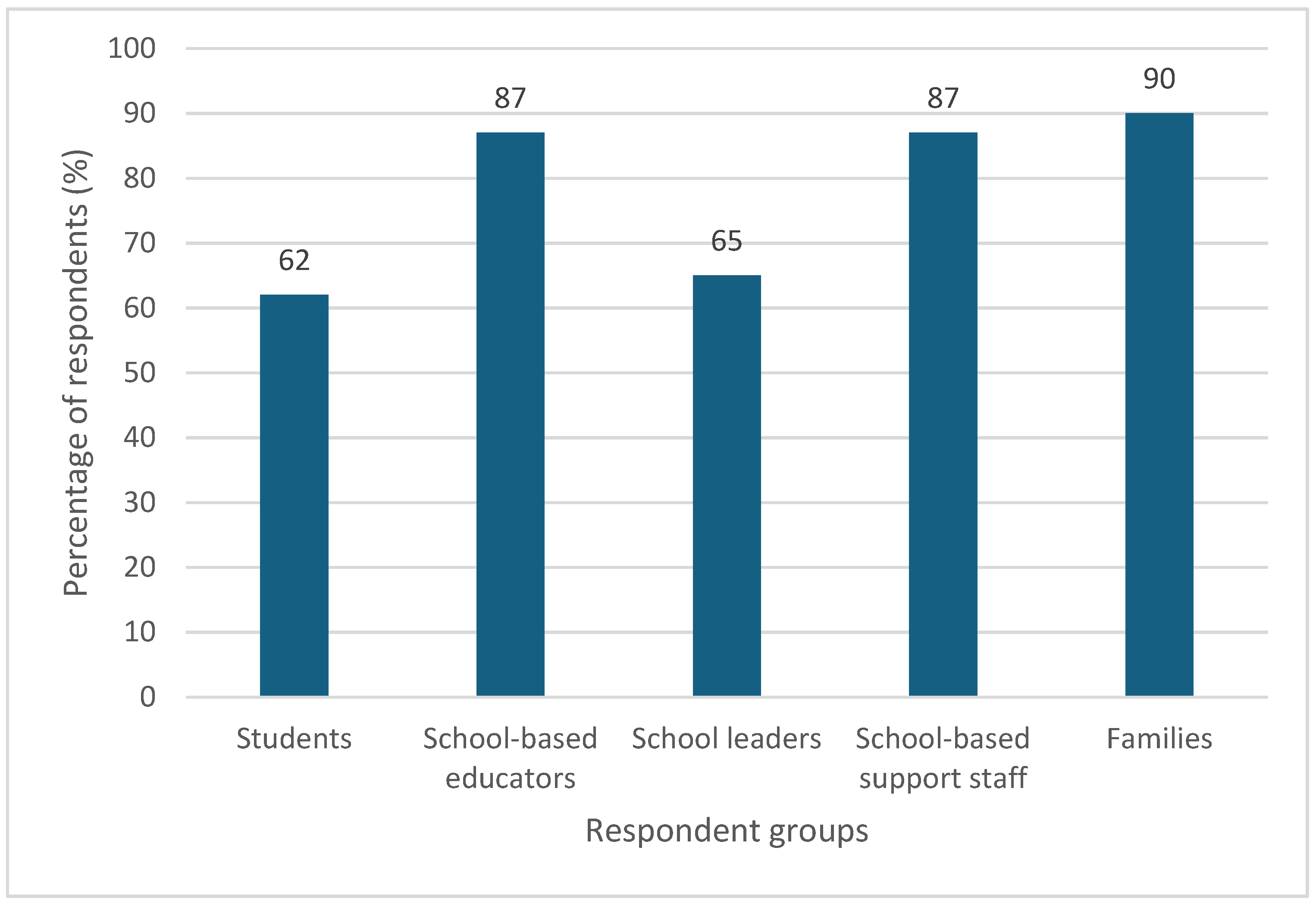

The surveyed groups were asked about the importance of regular COVID-19 testing in schools.

Figure 6.

Percentage of respondent groups who responded “Extremely” or “Most Important” to the BCPS 2020-2021 survey question “Regular COVID testing is extremely important or most important even if symptoms are not apparent.”.

Figure 6.

Percentage of respondent groups who responded “Extremely” or “Most Important” to the BCPS 2020-2021 survey question “Regular COVID testing is extremely important or most important even if symptoms are not apparent.”.

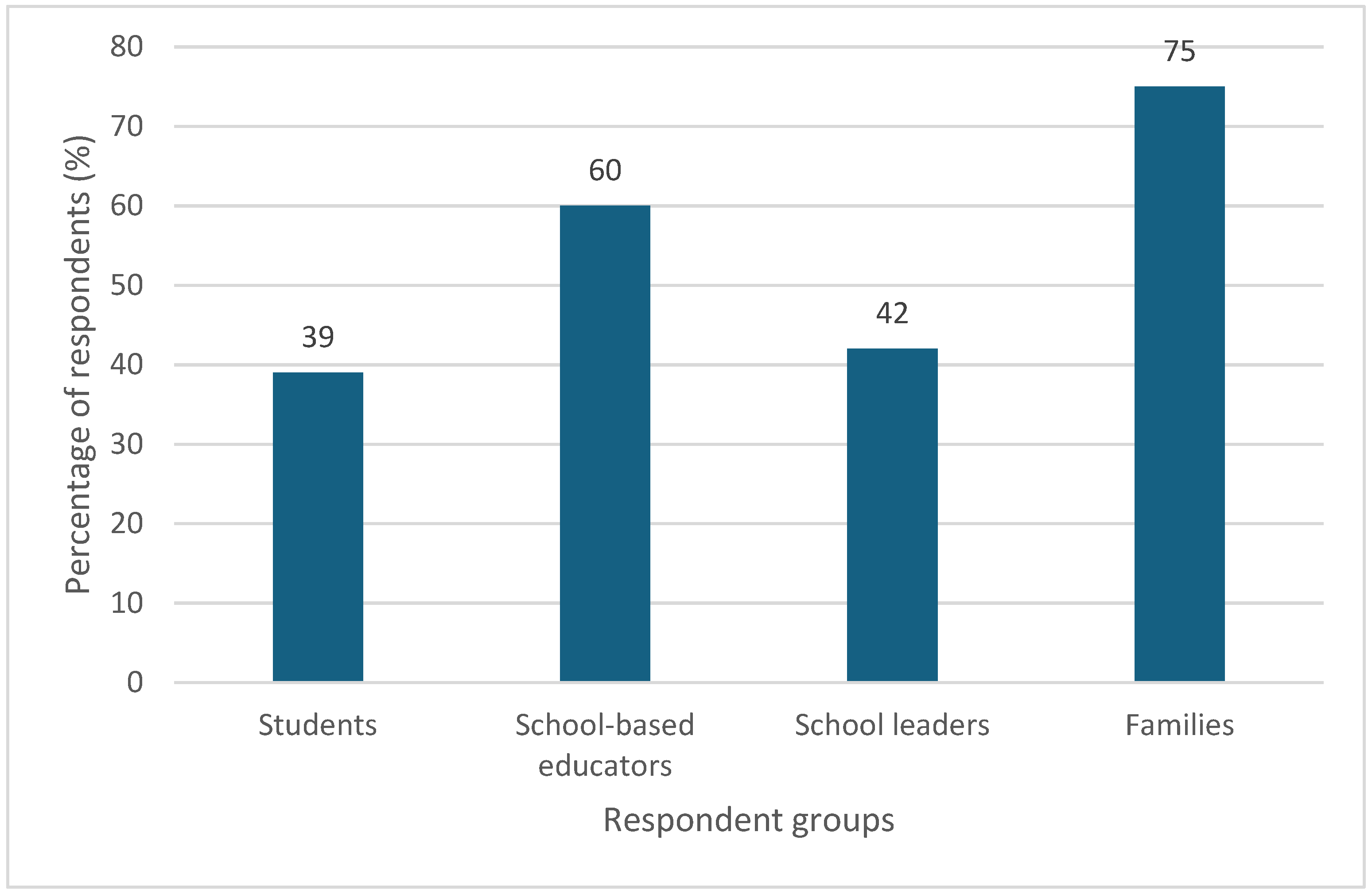

The surveyed groups were asked whether “Safety rules interrupted learning a little, somewhat, or not at all”[

25].

Figure 7.

Percentage of respondent groups who responded, “a little,” “somewhat,” or “not at all” to the BCPS 2020-2021 survey question “How much did safety rules interrupt learning?”.

Figure 7.

Percentage of respondent groups who responded, “a little,” “somewhat,” or “not at all” to the BCPS 2020-2021 survey question “How much did safety rules interrupt learning?”.

COVID-19 Era Budgets

Prior to BCPS fully understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, they passed their FY 2020–2021 Annual Budget on May 12, 2020, adopting a Health & Safety Operations Office Expenditure budget of

$1,969,325[

34]. They budgeted

$1,969,435 for the same line item in FY19[

34].

Maryland received

$21.9 billion in federal grant funding across the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Acts (CARES Act I), the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CARES Act II), and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA)[

35]. In addition, BCPS received

$760.1 million across federal grants during the COVID-19 emergency, through the Elementary Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER I & II), later expanded via ARPA, and the Governor‘s Emergency Education Relief (GEER). BCPS used this funding for the following programs: Learning loss (

$443.5 million), Safe reopening (

$247 million), Supplemental instruction and tutoring (

$56.3 million), Summer school (

$10.5 million), and Behavioral health (

$2.8 million)[

35].

COVID-19 Trends Before, During and After Protocols Introduction

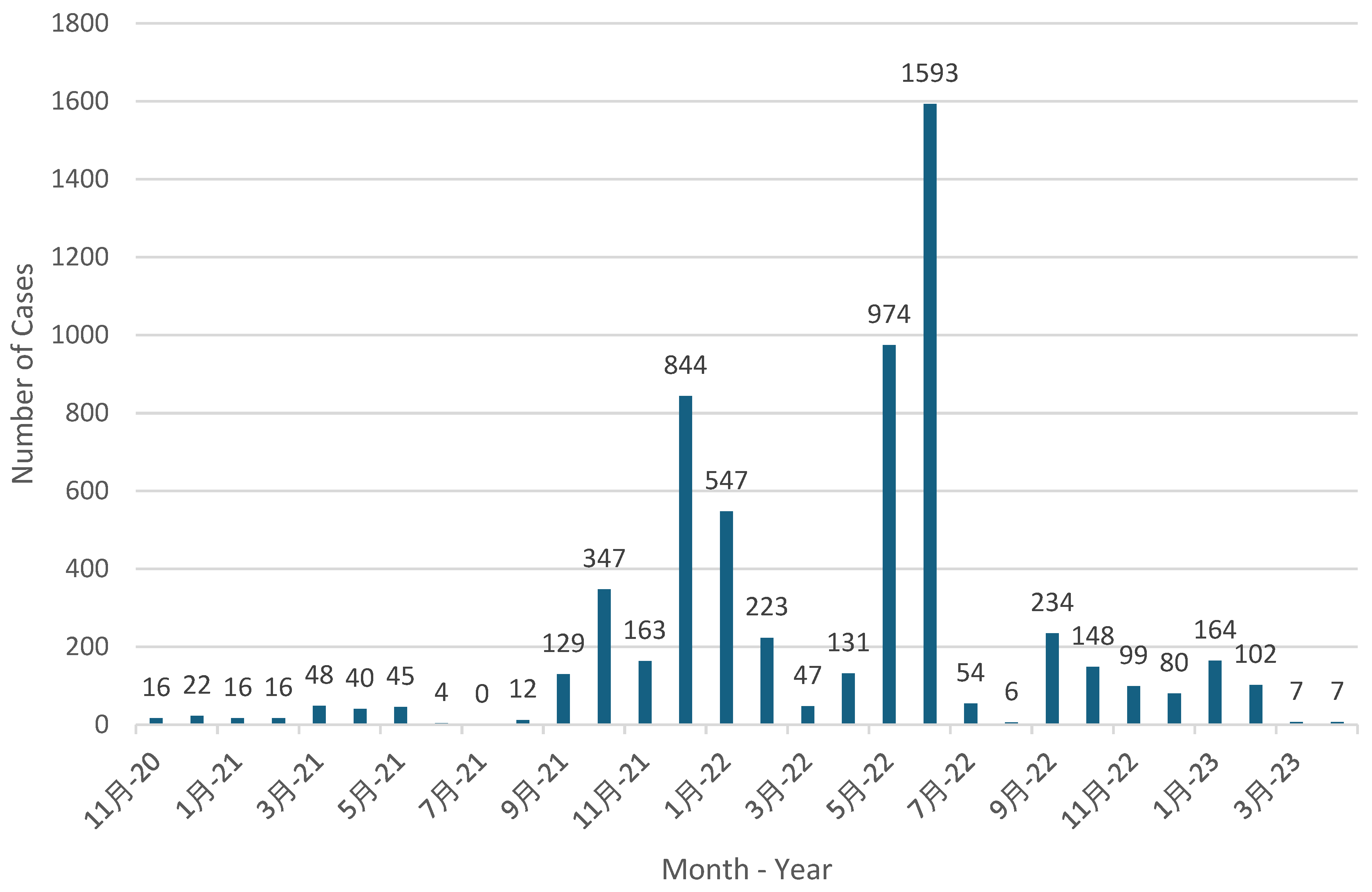

Figure 8.

A graph showing monthly reported COVID-19 cases throughout BCPS, reported to the Maryland Department of Health[

36]

.

Figure 8.

A graph showing monthly reported COVID-19 cases throughout BCPS, reported to the Maryland Department of Health[

36]

.

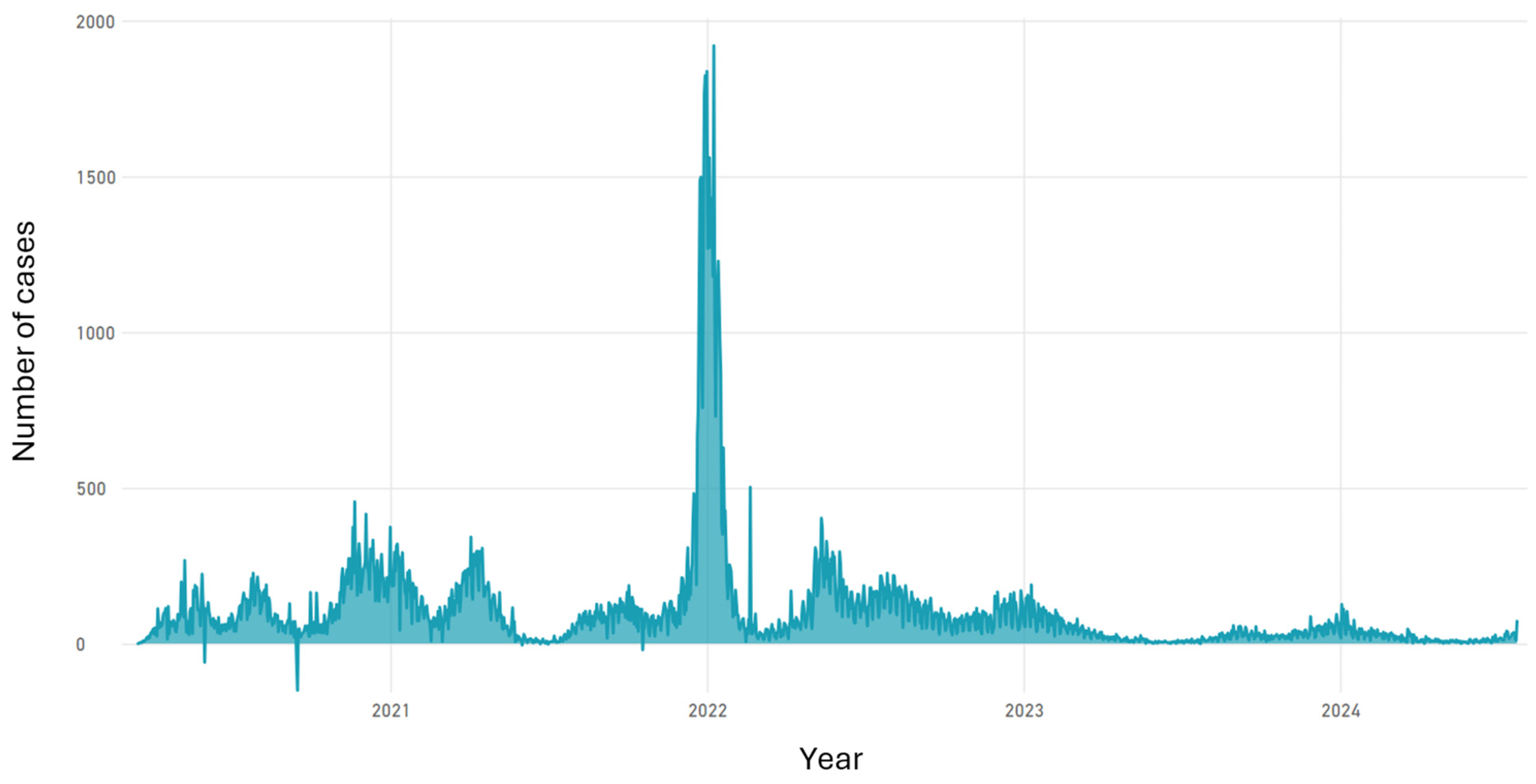

Figure 9.

A graph showing daily reported COVID-19 cases through Baltimore City, as reported to the City of Baltimore Health Department[

37]

.

Figure 9.

A graph showing daily reported COVID-19 cases through Baltimore City, as reported to the City of Baltimore Health Department[

37]

.

As presented in the data above, there are two significant peaks of cases: one in December 2021, as district cases climbed sharply following the Thanksgiving holiday. The other peak occurred in May 2022 to June 2022, with close to 500 cases reported per week in the district; this was concurrent with a smaller peak in cases across Baltimore City; however, there was a smaller peak in school cases in December 2021 and a larger peak in May 2022; this is the inverse of the larger trend throughout Baltimore City, which experienced its sharpest peak in December 2021, and a milder peak in May 2022[

37].

Local news reported the May 2022 outbreak was at a particular grade level within a specific school, with epidemiological investigations indicating that the spread was “likely traced back to an event that happened over the weekend,” along with several community events happening around the date of that initial event.[

38] Accounting for this unusual event that drove a massive spike in case transmission, the rest of the epidemiological curve for cases in BCPS tracks closely with the general trend present for the entire city.

Conclusions

In this study, we discussed the multilayered approach taken by BCPS to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and reduce the risk of viral transmission among the system’s students, faculty, and staff. To accomplish this, BCPS used several COVID-19 mitigation and student/faculty support measures and multiple sources of funding. The school system chose to take these measures based on federal and state public health guidance and because these methods had individually been shown, prior to COVID-19, to be associated with a reduction in the number of respiratory illnesses, both in students and staff. Many of the measures implemented by BCPS have been individually associated with reduced COVID-19 prevalence, although not causally linked; have become standardized recommendations across several public health agencies; and have been recommended for incorporation into future pandemic preparedness policies[

37,

39].

These individual measures taken by BCPS cannot be causally associated with a reduced COVID-19 case incidence amongst its students, staff, and community. However, the combination of measures implemented provided significant insight into the level of effort, and continued intent required to keep a large urban school district operating as efficiently as possible during this crisis. The process of designing and implementing these measures also indicate that it is necessary to design those measures with as much community and stakeholder engagement and buy-in as possible, to keep open communication and support people feeling safe to return to in-person settings.

In that regard, assessing purely whether this urban school system was able to remain operational throughout the pandemic, and was able to mitigate the system-wide loss of educational days, and to reduce the number of students who would miss education due to necessary quarantine and isolation procedures, the school was successful. The school system did not close after reopening and was able to continuously provide a variety of methods for students to continue to learn, both through hybrid education, and through the provision of full-time online learning for those families that chose it. While internet connectivity was initially poor, improvements in the provision of mobile hotspots for educational use helped to bridge some of the gaps for students who did not previously have access to at-home internet[

31].

Even though the acute stage of the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, school systems like BCPS will need continued support and guidance to better design and use policies to remain open and provide necessary social services and education to students during future epidemics and pandemics[

40]

. Therefore, it is essential to document the experiences of these different school districts to better design policies to prepare schools for the next crisis or disease outbreak.

Due to the additional benefits and services that schools provide, as well as the learning-loss identified because of virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, instituting safe reopening measures needs to be prioritized when possible, during future pandemics so that schools can return to in-person education[

4]. Layered prevention strategies will allow schools to operate in-person while protecting students and staff from the harms and risks of diseases like COVID-19. Due to the loss of in-person education during COVID-19, multiple studies found not only a decrease in student scores in standardized math and literature tests,[

2,

41] but also that these learning losses were exacerbated in households already experiencing inequalities. Lower-income and historically disadvantaged students were further behind as compared to their higher-income, not-disadvantaged peers[

42]. Additionally, public schools provide additional services, such as food and childcare access, and many students and families experienced additional insecurities due to school closures[

43].

As seen throughout this case study, recommendations that should be taken forward from this example and applied towards other similar school systems include the implementation of a robust case surveillance system as well as a thorough testing system to promote case detection and improve contact tracing during active outbreaks. Additionally, as BCPS has shown, one-time investments in the renovation of indoor air quality measures, as well as routine up-keep and maintenance of those measures to maintain maximum efficacy may help reduce the transmission of common seasonal respiratory illnesses that impact student health and attendance, including COVID-19 as another future endemic disease in school settings[

44].

It is also important to highlight the necessity of having public funding available for these policies to be implemented and necessary renovations to ensure indoor air quality and school infrastructure to be made. Insufficient funding will pose challenges to implementing these recommendations, particularly in public schools that are already not well-resourced. Public schools are funded by local, state, and federal sources, and in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, they received supplemental federal funding. This funding went toward education-related initiatives, meal provision, and after-school childcare through supplemental activities, and with limitations in the funding accessible, different public-school systems made different choices on what was most necessary to prioritize. Consequently, many schools chose not to use funding for building renovations or long-term, more systemic protections against future respiratory disease outbreaks. Without the accessibility of funds to take both short- and long-term actions against respiratory disease outbreaks such as these, public school systems are at risk of collapsing under the weight of the demands placed on them[

45].

Without the same caliber of funding restrictions and limitations, and with flexibility in spending, some private schools chose to prioritize different mitigation measures, such as systematic improvements to indoor air quality. Due to the broader range in funding resources, and the ability to make different choices with their funding, some private school systems may have been able to achieve more rapid gains in pandemic mitigation measures, as well as a higher level of student and parent satisfaction[

46]. Again, while individual measures cannot be separated to be examined for individual efficiency, a well-thought-out combination of pandemic mitigation measures, using sufficient funding for long-term improvements to indoor air quality, were associated with a lowered prevalence of COVID-19, particularly at private institutions. Some of the measures necessary to reduce COVID-19 prevalence, such as improved indoor air quality, are also associated with long term student benefits, such as a reduction in overall illness incidence year-round, indicating that public funding for long-term pandemic mitigation measures may be doubly beneficial [

46].

Limitations

The measures within this case study can only be examined in the contexts of Baltimore City Public Schools and Baltimore City, in the form of correlations or associations. Based on the quality of data available, it is not possible to establish causality between the system’s measures and decreased student, staff, and community prevalence of COVID-19. As such, the aims of this case study are to accurately document the experience of a school system during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, and to highlight the need for similar significant documentations of data from this period to inform future pandemic and outbreak scenarios.

Acknowledgements

[Redacted for preprint]

Competing Interests:Competing Interests. No competing interests to report.

Personal Financial Interests. No personal financial interests to report.

Funding. The research data was provided by Baltimore City Public School System, which is a public school system; as such, this organization does not stand to gain or lose financially from publication of the article through reception of positive/negative press attention, derived from responses to the article. The funding for this article was provided through a grant from the Bloomberg American Health Initiative.

Employment. AI has no personal employment interests to report. While in a different role for a different US state, NI contracted Ginkgo Bioworks for K-12 Testing via public procurement. GG was a member of the BCPS Public Health Advisory Committee but was not paid for her role.

References

- City schools at a glance. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/o/bcps/page/district-overview Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/o/bcps/page/district-overview. Updated 2024. Accessed Jun 19, 2024.

- Donnelly R, Patrinos HA. Learning loss during covid-19: An early systematic review. PROSPECTS. 2022;51(4):601–609. [CrossRef]

- Currie J, Thomas D. Early test scores, school quality and SES: Longrun effects on wage and employment outcomes. In: Polachek S, ed. Worker wellbeing in a changing labor market. Vol 20. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2001:103–132. [CrossRef]

- Schools should prioritize reopening in fall 2020, especially for grades K-5, while weighing risks and benefits. https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2020/07/schools-should-prioritize-reopening-in-fall-2020-especially-for-grades-k-5-while-weighing-risks-and-benefits. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Turner C. 'Children are going hungry': Why schools are struggling to feed students. NPR. -09-08T05:00:00-04:00 2020. Available from: https://www.npr.org/2020/09/08/908442609/children-are-going-hungry-why-schools-are-struggling-to-feed-students. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Ng G, Fulginiti J, Lucas T. 2021 timeline: Coronavirus in Maryland. WBALTV 11. -01-04T17:21:00 2022. Available from: https://www.wbaltv.com/article/covid-19-in-maryland-2021-timeline/35169408. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- CORRECTION: City schools purchases hotspots to keep students connected this summer. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1365579. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Round I. Beginning Monday, city schools will distribute laptops and hotspots through schools. Baltimore Brew Web site. https://www.baltimorebrew.com/2020/08/19/beginning-monday-city-schools-will-distribute-laptops-and-hotspots-through-schools/. Updated 2020. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Ng G, Fulginiti J, Lucas T. 2021 timeline: Coronavirus in Maryland. https://www.wbaltv.com/article/covid-19-in-maryland-2021-timeline/35169408. Updated 2022. Accessed June 19, 2024.

- VaxU scholarship promotion. Maryland Higher Education Commission Web site. https://mhec.maryland.gov/Pages/vaxU-scholarship-promotion.aspx. Accessed Jun 19, 2024.

- COVID dashboard and the return of school-based testing announced. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1364626. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Updated COVID procedures for 2022-23 school year. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1363480. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- City schools announces reopening plan. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1365587. Updated 2020. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- About physical distancing and respiratory viruses. United States Centers for Disease Control Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/prevention/physical-distancing.html. Updated 2024. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- COVID testing program expands learning time and serves as national model. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1359999. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Baltimore City Public School System. BCPSS COVID-19 case tracker portal. https://app.smartsheet.com/b/publish?EQBCT=834975018e5f49e181a486e7ccd49863. Updated 2023. Accessed Jun 19, 2024.

- US EPA O, McCormack M, Leaf P, Curriero F, Connolly F, Koehler K. Final report | baltimore healthy schools: Impact of indoor air quality on health and performance | research project database | grantee research project | ORD | US EPA. The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore City Schools, Baltimore Education Research Consortium. . https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts//index.cfm. Accessed Jun 19, 2024.

- Leaf P, Curriero F, Connolly F, Koehler K. Final report | baltimore healthy schools: Impact of indoor air quality on health and performance | research project database | grantee research project | ORD | US EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency Web site. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts//index.cfm. Updated 2019. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- In-person air quality plan. Internet Archive Web site. https://web.archive.org/web/20230929011549/https:/www.baltimorecityschools.org/in-person-air-plan. Updated 2023. Accessed October 21, 2023.

- Vaccination update. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1364620. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 27, 2024.

- Vaccinate Maryland (middle or high school). . :1–3. Accessed Oct 27, 2024.

- Wong CA, Pilkington W, Doherty IA, et al. Guaranteed financial incentives for COVID-19 vaccination: A pilot program in north carolina. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2022;182(1):78–80. Accessed Oct 21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Student- athletes must "test-to-play". Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1363416. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 27, 2024.

- Stole B, Bowie L, Wood P. Maryland gov. hogan calls on schools to bring students back to classrooms by march under hybrid learning plan. . 2021. https://www.baltimoresun.com/2021/01/21/maryland-gov-hogan-calls-on-schools-to-bring-students-back-to-classrooms-by-march-under-hybrid-learning-plan/. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Santelises SB, Jones T, Hike-Hubbard T. Baltimore city public schools: End-of-year stakeholder survey results, 2021-22 school year. Baltimore City Public Schools. . https://core-docs.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/documents/asset/uploaded_file/3843/BCPS/3601144/End_of_Year_Engagement_Results.pdf. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Baltimore teachers union | history & mission. Baltimore Teachers Union Web site. https://baltimoreteachers.org/about/history-mission/. Accessed Oct 29, 2024.

- Baltimore teachers union (btu) re-opening campaign: #Safenotsilenced. Baltimore Teachers Union Web site. . Updated 2024. Accessed October 21, 2024.

- Berinato C. Baltimore teachers union to protest school reopening. Fox Baltimore News Web site. https://foxbaltimore.com/news/local/baltimore-teachers-union-to-protest-school-reopening. Updated 2021. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- City schools to start school year online. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1365592. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 27, 2024.

- Pilgrim P. Rising to the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Baltimore Educator. 2020:1–20. https://www.baltimoreteachers.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/BTU-Newsletter-Vol.-1-Issue-3-Website-Version.pdf. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Students petition comcast, asking for better internet service during COVID-19 pandemic. WMAR2 News Web site. https://www.wmar2news.com/news/region/baltimore-city/students-petition-comcast-asking-for-better-internet-service-during-covid-19-pandemic. Updated 2020. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Virtual learning program for the 2022-23 school year. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/article/1361119. Accessed Oct 27, 2024.

- Baltimore Teachers Union. #ResultsToReturn toolkit. . :1–2. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1FR5EZetGrCnxmjIJyjY216OyKbk5u3Dsdoco8pL4880/edit?tab=t.0. Accessed Oct 27, 2024.

- Baltimore city public schools | 2020-21 budget. Baltimore City Public Schools Web site. https://web.archive.org/web/20230703011730/https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/FY21_AdoptedOperatingBudget_051420_Remediated.pdf. Updated 2023. Accessed Oct 21, 2024.

- Federal COVID-19 funds: Baltimore city and Baltimore city public schools. Maryland Center on Economic Policy Web site. https://www.mdeconomy.org/baltimore-covid-relief/. Updated 2022. Accessed Jun 19, 2024.

- MD COVID19 school outbreaks. https://data.imap.maryland.gov/datasets/maryland::mdcovid19-casesbyagedistribution/explore. Accessed Jun 20, 2024.

- Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) number of cases by report date. City of Baltimore Department of Health Web site. https://coronavirus.baltimorecity.gov/. Accessed Jun 20, 2024.

- Vermer B. Baltimore city and county schools deal with COVID-19 outbreaks. WMAR 2 News Baltimore Web site. https://www.wmar2news.com/news/local-news/baltimore-city-and-county-schools-deal-with-covid-19-outbreaks. Updated 2022. Accessed Jun 20, 2024.

-

Reopening K-12 schools during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prioritizing health, equity, and communities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25858/chapter/1. Accessed Oct 21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Viner RM, Bonell C, Drake L, et al. Reopening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic: Governments must balance the uncertainty and risks of reopening schools against the clear harms associated with prolonged closure. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(2):111–113. http://adc.bmj.com/content/106/2/111.abstract http://adc.bmj.com/content/106/2/111.abstract. [CrossRef]

- Engzell P, Frey A, Verhagen MD. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2023;118(17):e2022376118. [CrossRef]

- Dorn E, Hancock B, Sarakatsannis J, Viruleg E. COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning | McKinsey. McKinsey & Company Web site. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/covid-19-and-education-the-lingering-effects-of-unfinished-learning. Accessed Jun 19, 2024.

- Parekh N, Ali SH, O'Connor J, et al. Food insecurity among households with children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a study among social media users across the united states. Nutr J. 2021;20(1):73. Accessed Jul 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Birmili W, Selinka H, Moriske Hö, Daniels A, Straff W. Ventilation concepts in schools for the prevention of transmission of highly infectious viruses (SARS-CoV-2) by aerosols in indoor air. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2021;64(12):1570–1580. [CrossRef]

- Hecht AA, Dunn CG, Kinsey EW, et al. Estimates of the nutritional impact of non-participation in the national school lunch program during COVID-19 school closures. Nutrients. 2022;14(7). [CrossRef]

- Iyengar A, Hanon S, Bruns R, Olsiewski P, Gronvall GK. COVID-19 Mitigation in a K-12 School Setting: A Case Study of Avenues: The World School in New York City. Health Security. 2024. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Detailed Timeline of COVID-19 Related Policies and Changes in and affecting Baltimore City Schools.

Table 1.

Detailed Timeline of COVID-19 Related Policies and Changes in and affecting Baltimore City Schools.

| Date |

Policy Institution/Change |

| March 5,2020 |

Maryland State of Emergency declared by then-Governor Larry Hogan |

| March 12, 2020 |

Maryland Public Schools closed from March 16-27th, learning packets prepared in anticipation of longer-term closures |

| Mar 13, 2020 |

Baltimore City Public Schools announces it is participating in the Emergency Feeding Program during the Emergency Closure period outlined by the Government of Maryland. The program is funded by the USDA, and administered by the Maryland DOE, and provides breakfast and lunch free of charge to children at school sites during the emergency closure of schools. |

| March 25, 2020 |

Maryland Public Schools closed further until April 26th. Maryland distributes 4,000 Chromebooks to students without devices and internet access to support remote learning |

| April 17, 2020 |

Maryland Public Schools closed further until May 15th. |

| May 6, 2020 |

Maryland Public Schools closed further through the end of the school year |

| July 20, 2020 |

BCPS in-person education reopening delayed until later in the fall, with virtual education still in place at the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year. |

| October 7, 2020 |

A phased approach to reintroduce in-person instruction was suggested, starting with select groups of students |

| December 7, 2020 |

BCPS announced a revised plan to start a hybrid learning model in January 2021, beginning with students in Pre-K through second grade, and special education students. |

| January 4, 2021 |

BCPS welcomed back students from Pre-K to 2nd grade, as well as special education students |

| February 23, 2021 |

Beginning March 1, BCPS will be expanding in-person learning options to students in grades 3-5. Pooled screenings will be conducted for elementary grades, and individual saliva screenings will be conducted at the high school levels. |

| March 15, 2021 |

BCPS expanded the hybrid learning model further to include middle and high school students on a group-by-group basis |

| May 14, 2021 |

On May 10th, the FDA provided emergency use authorization for the Pfizer vaccine for children 12 years of age and older. |

| May 24, 2021 |

BCPS announced that 2021-2022 school year would start with full in-person instruction for all students, with remote learning options available for families that chose to opt-in. |

| June 15, 2021 |

Protocols for the 2021-2022 school year are detailed, including mask mandates and social distancing guidelines.

- -

Mask mandates were in place for all people inside school buildings - -

Daily health screenings and temperature checks would take place - -

Schools would be engaged in ventilation and air quality improvements - -

Social distancing will be maintained where feasible. - -

Increased sanitation and hand hygiene will be promoted

|

| August 31, 2021 |

High school student athletes participating in winter and spring sports will be required to be vaccinated before their seasons begin; students participating in fall sports will not be required to be vaccinated, but are strongly encouraged to |

| September 8, 2021 |

BCPS re-launched the COVID-19 dashboard for the 2021-2022 school year, showing daily updates of any COVID-19 cases among students, staff, and others within schools |

| December 20, 2021 |

Policies are updated:

- -

Masks required indoors at all schools and offices. - -

Air filters upgraded at schools, or air purifiers added where needed. - -

Normal pace of testing (weekly for students and staff) will continue through January. - -

Staff members must be vaccinated

|

| January 3, 2022 |

Winter break will be extended to Monday and Tuesday, January 3-4th, 2022 to offer testing opportunities for students and staff |

| January 13, 2022 |

BCPS reduced its required quarantine period to 5 days for students and staff, and instituted a Test to Stay protocol, aligned with recent guidance for K-12 schools from the CDC and Maryland Department of Health. Testing pools were also reduced to five individuals, when possible, to more quickly identify which students needed to quarantine |

| February 16, 2022 |

Some schools temporarily transitioned to virtual learning, based on the ability to operate a school or the ability to conduct COVID-19 testing |

| March 8, 2022 |

The use of masks and face coverings will be optional for all persons in BCPS beginning March 14, 2022 |

| August 23, 2022 |

Policy Changes:

- -

Masking is now optional in buildings and on school grounds UNLESS the student/staff member in question had COVID-19 in the last ten days or was exposed in the last 10 days. - -

Anyone who tests positive must isolate for at least 5 days. - -

Screen testing will take place every other week, and students and staff will have access to diagnostic testing if they feel sick or were exposed to COVID. - -

Field trips, athletics, and indoor events may proceed as planned; however, students attending overnight, and out-of-state trips must be vaccinated or participating in BCPS testing

|

| November 11, 2022 |

COVID-19 test kits were provided to every student and all staff before Thanksgiving and Winter breaks, to be taken 1-2 days prior to return, and positive cases reported to the contact tracing team.Biweekly screening will no longer be conducted, and students will be tested if they show symptoms. |

| January 3, 2023 |

Schools will no longer notify families about individual cases and will track cases on the COVID-19 dashboard. Classrooms and schools will be notified of outbreaks, consisting of three or more cases that are linked. |

| June 13, 2023 |

BCPS will no longer provide COVID-19 testing, services, or support to schools or offices. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).