Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Detection of Cytokines and Growth Factors in Serum

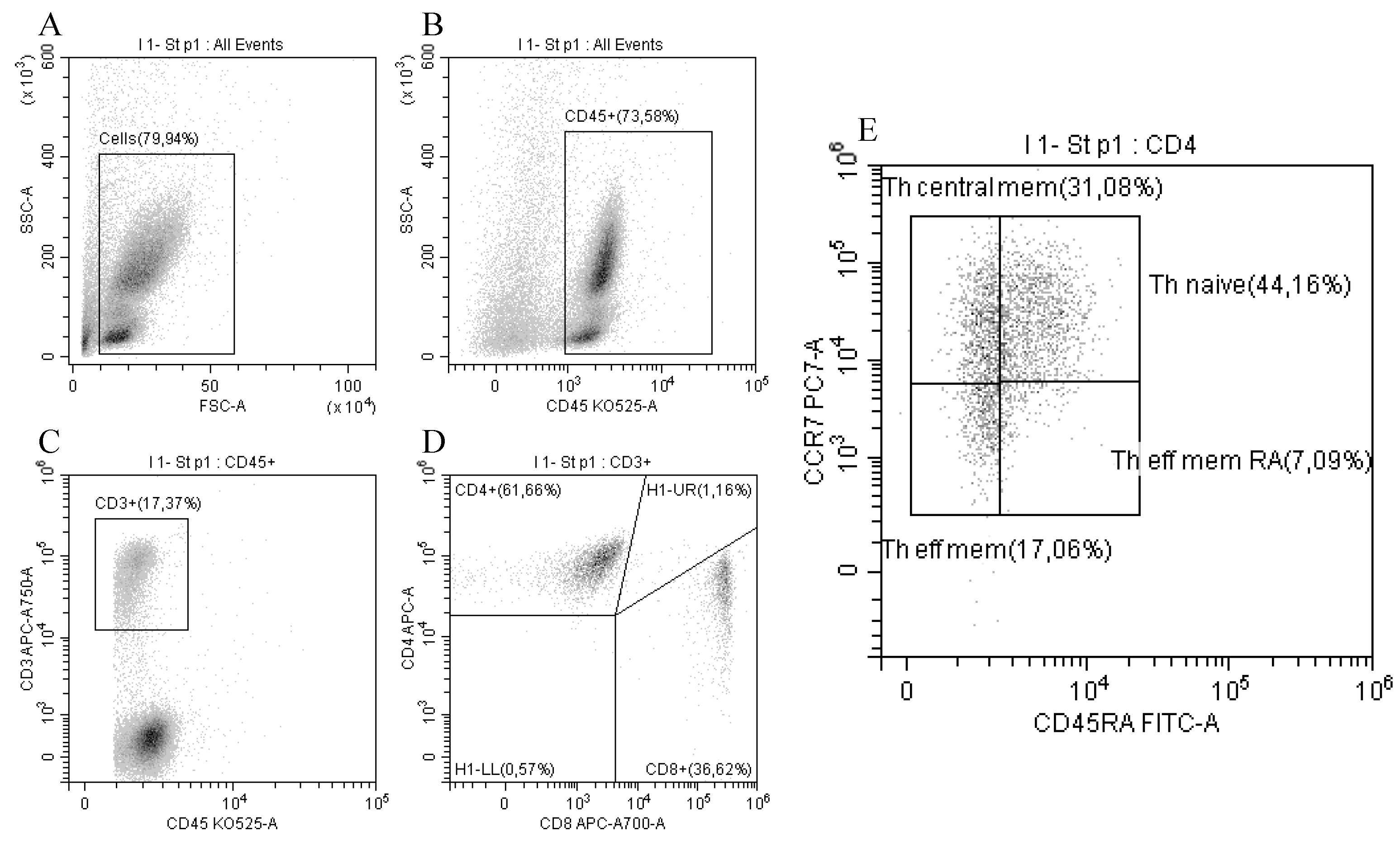

2.4. T-Cell Immunophenotyping

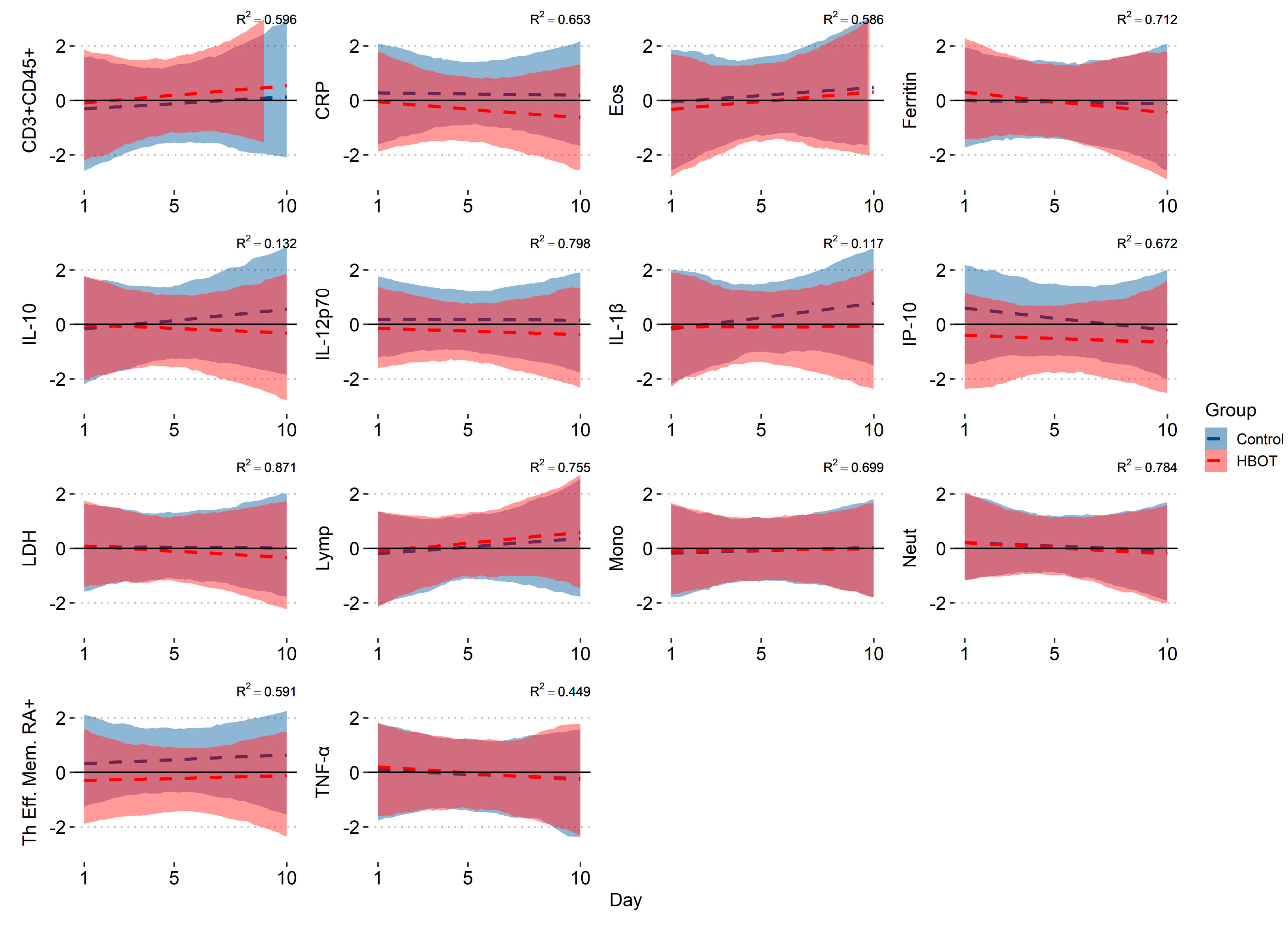

2.5. Model Construction and Validation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 17 Sep 2023).

- WHO. Currently circulating variants of interest (VOIs) (as of 28 June 2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed 8 Sep 2024).

- Oliaei, S.; Paranjkhoo, P.; SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Mehraeen, E.; Hackett D. Is There a Role for Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in Reducing Long-Term COVID-19 Sequelae? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2270.

- Kjellberg, A.;Hassler, A.; Boström, E. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for long COVID (HOT-LoCO), an interim safety report from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Zamani Rarani, F.; Zamani Rarani, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Rashidi, B.; Hashemian, S.M.R.; Mirzaei, H. Comprehensive overview of COVID-19-related respiratory failure: focus on cellular interactions. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27(1), 63. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.S.; Bertolino, L.; Zampino, R.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Monaldi Hospital Cardiovascular Infection Study Group. Cardiac sequelae after coronavirus disease 2019 recovery: a systematic review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27(9), 1250-1261. [CrossRef]

- Cothran, T.P.; Kellman, S.; Singh, S; et al. A brewing storm: The neuropsychological sequelae of hyperinflammation due to COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 957-958. [CrossRef]

- Gheware, A.; Ray, A.; Rana, D.; et al. ACE2 protein expression in lung tissues of severe COVID-19 infection. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1), 4058. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, G.D.; Ji, C.; Connolly, B.A.; et al. Effect of Noninvasive Respiratory Strategies on Intubation or Mortality Among Patients With Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure and COVID-19: The RECOVERY-RS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022, 327(6), 546-558.

- Phetsouphanh, C.; Darley, D.R.; Wilson, D.B.; et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23(2), 210-216.

- van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis ,E.; Pickkers, P.; et al. A guide to immunotherapy for COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28(1), 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Etayo, F.J.; Suarez-Fernandez, P.; Cabrera-Marante, O.; Arroyo, D.; Garcinuno, S.; Naranjo, L.; et al. T-Helper Cell Subset Response Is a Determining Factor in COVID-19 Progression. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 624483. [CrossRef]

- Boechat, J.L.; Chora, I.; Morais, A.; Delgado, L. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 immunopathology - Current perspectives. Pulmonology. 2021, 27(5), 423-37.

- Moss, P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23(2), 186-93.

- Habel, J.R.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; van de Sandt, C.E.; Juno, J.A.; Chaurasia, P.; Wragg, K.; et al. Suboptimal SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8(+) T cell response associated with the prominent HLA-A*02:01 phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117(39), 24384-91.

- Laing, A.G.; Lorenc, A.; del Molino del Barrio, I.; Das, A.; Fish, M.; Monin, L.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; McKenzie, D.R.; Hayday, T.S.; Francos-Quijorna, I.; et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1623-1635.

- Gorenstein, S.A.; Castellano, M.L.; Slone, E.S.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for COVID-19 patients with respiratory distress: treated cases versus propensity-matched controls. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2020, 47(3), 405-413.

- Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.-A.; Jiang, J.; Su, N. Specific cytokines in the inflammatory cytokine storm of patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome and extrapulmonary multiple-organ dysfunction. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 117.

- Rarani, F.Z.; Rashidi, B.; Jafari Najaf Abadi M.H.; Hamblin, M.R.; Reza Hashemian, S.M.; Mirzaei, H. Cytokines and microRNAs in SARS-CoV-2: What do we know? Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2022, 29, 219-242.

- Mulchandani, R.; Lyngdoh, T.; Kakkar, A.K. Deciphering the COVID-19 cytokine storm: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13429. [CrossRef]

- Kuppalli, K.; Rasmussen, A.L. A glimpse into the eye of the COVID-19 cytokine storm. EBioMedicine 2020, 55, 102789.

- Mangalmurti, N.; Hunter, C.A. Cytokine Storms: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2020, 53(1), 19-25.

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yan, X.; et al. Neutrophil infiltration and myocarditis in patients with severe COVID-19: A post-mortem study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1026866. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Stojkov, D.; Fettrelet, T.; Bilyy, R.; Yousefi, S.; Simon, H.U. Transcriptional Insights of Oxidative Stress and Extracellular Traps in Lung Tissues of Fatal COVID-19 Cases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(3), 2646.

- Veenith, T.; Martin, H.; Le Breuilly, M.; et al. High generation of reactive oxygen species from neutrophils in patients with severe COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1), 10484.

- Diao, B.; Wang, C.; Tan, Y.; et al. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 827. [CrossRef]

- Laforge, M.; Elbim, C.; Frère, C.; et al. Tissue damage from neutrophil-induced oxidative stress in COVID-19 [published correction appears in Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20(9), 515-516.

- Mathieu, D.; Marroni, A.; Kot, J. Tenth European Consensus Conference on Hyperbaric Medicine: recommendations for accepted and non-accepted clinical indications and practice of hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Diving hyperbar. med.: j. South Pac. Under. Med. Soc.. 2017, 47(1):24-32.

- Shinomiya, N.; Asai, Y. Hyperbaric Oxygenation Therapy: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2019; pp. 55–65.

- Boet, S.; Martin, L.; Cheng-Boivin, O.; et al. Can preventive hyperbaric oxygen therapy optimise surgical outcome?: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 37(8), 636-648.

- Fosen, K.M,; Thom, S.R. Hyperbaric oxygen, vasculogenic stem cells, and wound healing. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2014, 21(11), 1634-1647. [CrossRef]

- de Wolde, S.D.; Hulskes, R.H.; de Jonge, S.W.; et al. The Effect of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy on Markers of Oxidative Stress and the Immune Response in Healthy Volunteers. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 826163.

- Bosco, G.; Paganini, M.; Giacon, T.A.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation, MicroRNA, and Hemoglobin Variations after Administration of Oxygen at Different Pressures and Concentrations: A Randomized Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(18), 9755. [CrossRef]

- Lalieu, R.C.; Brouwer, R.J.; Ubbink, D.T.; Hoencamp, R.; Bol Raap, R.; van Hulst, R.A. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for nonischemic diabetic ulcers: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 266–275. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, R.J.; Lalieu, R.C.; Hoencamp, R.; van Hulst, R.A.; Ubbink, D.T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcers with arterial insufficiency. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 71, 682–692.e681. [CrossRef]

- Löndahl, M.; Boulton, A.J. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in diabetic foot ulceration: Useless or useful? A battle. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3233. [CrossRef]

- Lerche, C.J.; Schwartz, F.; Pries-Heje, M.M.; Fosbøl, E.L.; Iversen, K.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N.; Hyldegaard, O.; Bundgaard, H.; Moser, C. Potential advances of adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy in infective endocarditis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 15. [CrossRef]

- Hajhosseini, B.; Kuehlmann, B.A.; Bonham, C.A.; Kamperman, K.J.; Gurtner, G.C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: Descriptive review of the technology and current application in chronic wounds. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2020, 8, e3136. [CrossRef]

- Vinkel, J.; Rib, L.; Buil, A.; Hedetoft, M.; Hyldegaard, O. Key pathways and genes that are altered during treatment with hyperbaric oxygen in patients with sepsis due to necrotizing soft tissue infection (HBOmic study). Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28(1), 507. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liang, T.Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a narrative review. Med. Gas. Res. 2021, 11(2), 66-71.

- Zhong, X.T.Y.; Chen, R. Effect of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy on HBOT in Patients with Severe New Coronavirus Pneumonia: First Report Chinese. Chin. J. Naut. Med. Hyperb. Med. 2020, 27, 132–135.

- ECHM. European Committee for Hyperbaric Medicine (ECHM) Position on Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) in Multiplace Chambers During Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Available online: http://www.echm.org/documents/ECHM%20position%20on%20HBOT%20and%20COVID-19%20(16th%20March%202020).pdf (accessed on 8 Sep 2024).

- Cannellotto, M.; Duarte, M.; Keller, G.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjuvant treatment for patients with COVID-19 severe hypoxaemia: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg. Med. J. 2022, 39(2), 88-93.

- Siewiera, J.; Brodaczewska, K.; Jermakow, N.; Lubas, A.; Kłos, K.; Majewska, A.; Kot, J. Effectiveness of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia: The Primary Results of a Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12(1), 8.

- Gorenstein, S.A.; Castellano, M.L.; Slone, E.S.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for COVID-19 patients with respiratory distress: treated cases versus propensity-matched controls. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2020, 47(3), 405-413.

- Keller, G.A.; Colaianni, I.; Coria, J.; Di Girolamo, G.; Miranda, S. Clinical and biochemical short-term effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on SARS-Cov-2+ hospitalized patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Respir. Med. 2023, 209, 107155.

- Bhaiyat, A.M.; Sasson, E.; Wang, Z.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for long coronavirus disease-19: a case report. J. Med. Case. Rep. 2022, 16(1), 80.

- Leitman, M.; Fuchs, S.; Tyomkin, V.; Hadanny, A.; Zilberman-Itskovich, S.; Efrati, S. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on myocardial function in post-COVID-19 syndrome patients: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13(1), 9473.

- Robbins, T.; Gonevski, M.; Clark, C.; Baitule, S.; Sharma, K.; Magar, A.; Patel, K.; Sankar, S.; Kyrou, I.; Ali, A.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the treatment of long COVID: Early evaluation of a highly promising intervention. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e629–e632.

- Ceban, F.; Leber, A.; Jawad, M.Y.; et al. Registered clinical trials investigating treatment of long COVID: a scoping review and recommendations for research. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022, 54(7), 467-477. [CrossRef]

- Odak, I.; Barros-Martins, J.; Bošnjak, B.; et al. Reappearance of effector T cells is associated with recovery from COVID-19. EBioMedicine, 2020, 57, 102885. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).