1. Introduction

A universal and elusive phenomenon, humour appears everywhere. Humour has become an essential part of modern clever communication. The precise meaning of humour is difficult to accomplish since various people interpret humour differently in a piece of writing. It has proven to be an effective approach for creating social bonds and eliminating barriers. It removes a dialogue in addition to making a discussion more interesting. Automatic recognition of humor in texts presents remarkable difficulties because of its subjective nature and complex etymological designs. However, effective strategies for dealing with this issue have emerged due to furtherance in natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning [

1].

Computer systems can now comprehend humour and incorporate human intent into conversations thanks to technological advancements [

2]. Detecting humour in text aims to predict the degree of humour in the text [

3], so that more humour-related concealed meanings in natural language can be discovered. Much study has been conducted in order to determine what makes an individual laugh in a piece of writing. Detecting humour in text has proven to be an interesting yet difficult task in recent years due to its subjective nature [

2].

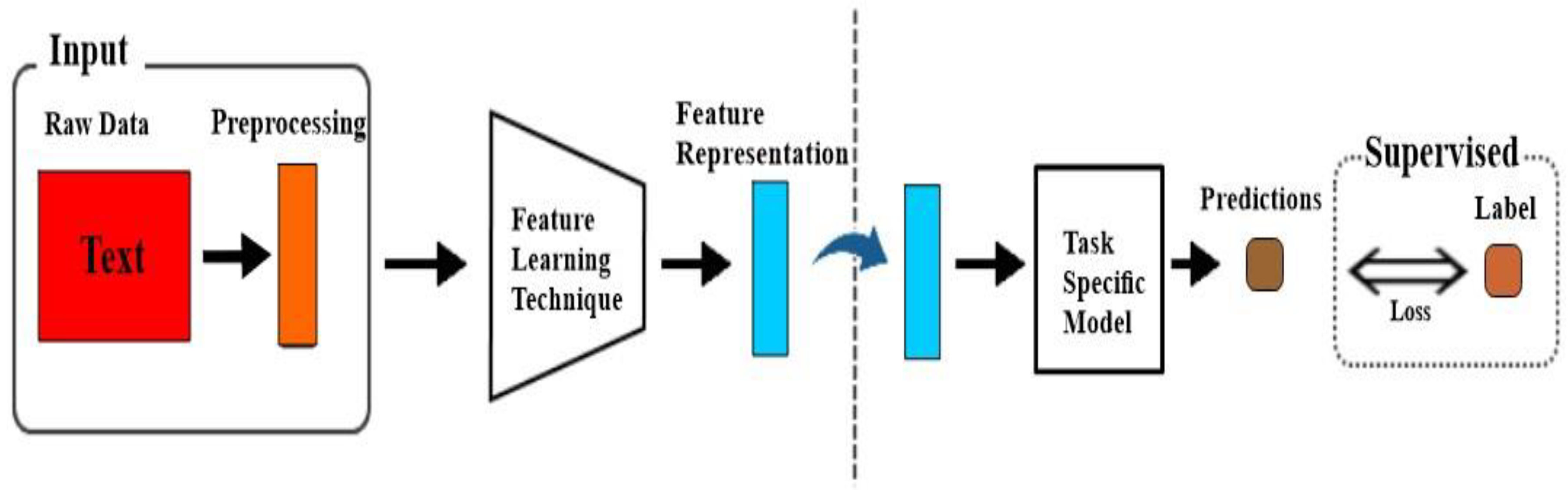

Different mechanisms such as machine learning and deep learning in conjunction with Natural Language Processing techniques have been used in humour detection. This research aims at developing an accurate and robust system for humour detection by developing models that are capable of accurately identifying instances of humour in text with a high degree of accuracy.

The following research questions are being addressed by this study;

What is the performance of the state-of-the-art pre-trained models in comparison with other models for humour detection?

How can we utilise deep learning models in identifying instances of humour in text?

This study is comprised of six sections: the introduction and the research questions in section 1, section 2 highlights the literature review. section 3 includes the methodological approach, results are highlighted and analyzed in section 4. Finally, in section 5 the results are discussed and the conclusions, limitation and future directions are presented in section 6.

2. Literature Review

Humor detection, the task of detecting and identifying humour in text, has gained tremendous interest in recent years. Researchers in the fields of NLP have explored approaches, including deep learning and machine learning techniques, to develop effective models for humor detection. Deep learning technology has advanced significantly in a number of research areas, including natural language understanding. Traditional humour evaluation techniques, in contrast to deep learning technology, mainly concentrate on analyzing sentences from the standpoint of language structure such as synthetic patterns, semantic relationships and linguistic features. For instance, a study presented a hybrid model which they called “DeepHumour” model in which both Convolution Neural Network (CNN) and Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) layers were integrated to identify between humorous and non-humorous texts. To address the limitation of contextual information learnt from CNN layers, LSTM layers were used and this approach attained the training accuracy of 89.61% and cross validation (CV) accuracy of 87.07% [

4]. The technique utilized in “DeepHumour” was able to capture the contextual meaning of the sentences. In a different approach, Mihalcea & Strapparava [

5] in a research study, investigated computational methods for detecting humour in a given text combining humor-specific features, such as alliteration, antonyms, and adult slang with text classification models. They limited their research to one-liners gleaned from the internet. On three datasets: Reuters news headlines, Proverbs, and the British National Corpus (BNC), humour was recognized using Naive Bayes and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers. For Reuters, BNC, and Proverbs, the humour recognition accuracy assessed by Naive Bayes was 96.67%, 73.22%, and 84.81%, respectively. SVM accuracy for Reuters, BNC, and Proverbs was 96.09%, 77.51%, and 84.48%, respectively. Although the accuracy achieved in this approach of detecting humour using simple machine learning techniques was higher as compared to “DeepHumour” techniques, however, the recognition process did not take into-account the humour-specific characteristics of ambiguity and semantic oppositions [

5].

Over the years implementation of deep learning techniques have been introduced by researchers for text analysis as these techniques have achieved a higher accuracy compared to traditional machine learning techniques [

4]. The advancement of technology and research has led to the unveiling of new techniques such as transfer learning [

3]. A research focused on humour detection and sentiment analysis utilized Decision Tree, SVM, Multilingual Naïve Bayes, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), ColBERT and Distillation-BERT (DilBERT) to classify humour of comic dataset. The dataset was extracted from two sources, the dilbert.com, and Garfield comics. The texts were extracted as both grammatically correct and grammatically incorrect and used for binary classification. DistilBERT outperformed other models in both grammatically correct and incorrect dataset which signifies the need for using a complex NLP model when complex linguistic expression like humor needs to be detected. When trained and tested on the grammatically correct dataset DilBERT gives more accurate predictions than when the parsed version of the dataset is used. DistilBERT achieved 70% while Decision Tree performed the lowest with an accuracy of 28% [

6]. These findings highlight the potential of transfer learning methods in humour detection tasks. Concurrently, experiments in several text domains have been conducted to investigate the feasibility of using pre-trained language models to extract information in text and capture contextual dependencies in conjunction with machine learning models to accomplish a number of tasks rather than fine-tuning the pre-trained model itself to a downstream task. A recent research proposed machine learning techniques using Bidirectional Encoders Representation from Transformers (BERT) and Global Vectors (GloVe) embeddings to detect sarcasm in a twitter dataset. The training dataset was the context of the tweet, meaning the topic tweeted about while the test dataset was the response to the topic or context tweeted. The context was 5000 entries while the response was 1800 entries labelled as sarcastic and non-sarcastic. The individual embeddings were combined with the machine learning models, Gaussian Naïve Bayes, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Linear Support Vector Classifier respectively. Logistic Regression outperformed other models with an accuracy of 63% when combined with BERT and 69% with Glove. The models performed better with Glove embeddings as compared with BERT embeddings which is more computationally intensive [

7].

Another notable work investigates humour recognition using a novel technique. In the study titled "Humour Detection: A Transformer Gets the Last Laugh," a transformer-based approach is suggested for determining humorous jokes based on ratings received from Reddit pages. The research focuses on the usage of a BERT Transformer architecture for learning from phrase context and shows the model's efficiency in humour identification tasks, outperforming earlier methods. The model was fine-tuned and trained Reddit jokes dataset and achieved an accuracy of 72%. The proposed model was tested on pun dataset and short jokes dataset and both achieved an accuracy of 93% and 98% respectively [

8]. This fine-tuned approach achieved a higher accuracy in contrast to using BERT for feature extraction [

7].

This research considers three deep learning Models in this research and a simple machine learning classifier as the baseline. Firstly, two dimensions of extrinsic word embeddings, Global Vectors and FastText in conjunction with Long Short-Term Memory. Secondly, finetune state-of-art transformer models, BERT and DistillationBERT to explore how differently these models perform. The effectiveness of the different classifiers will be evaluated using different evaluation techniques.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, the approaches are discussed along with the datasets and the models used for classification tasks.

3.1. Data Collection

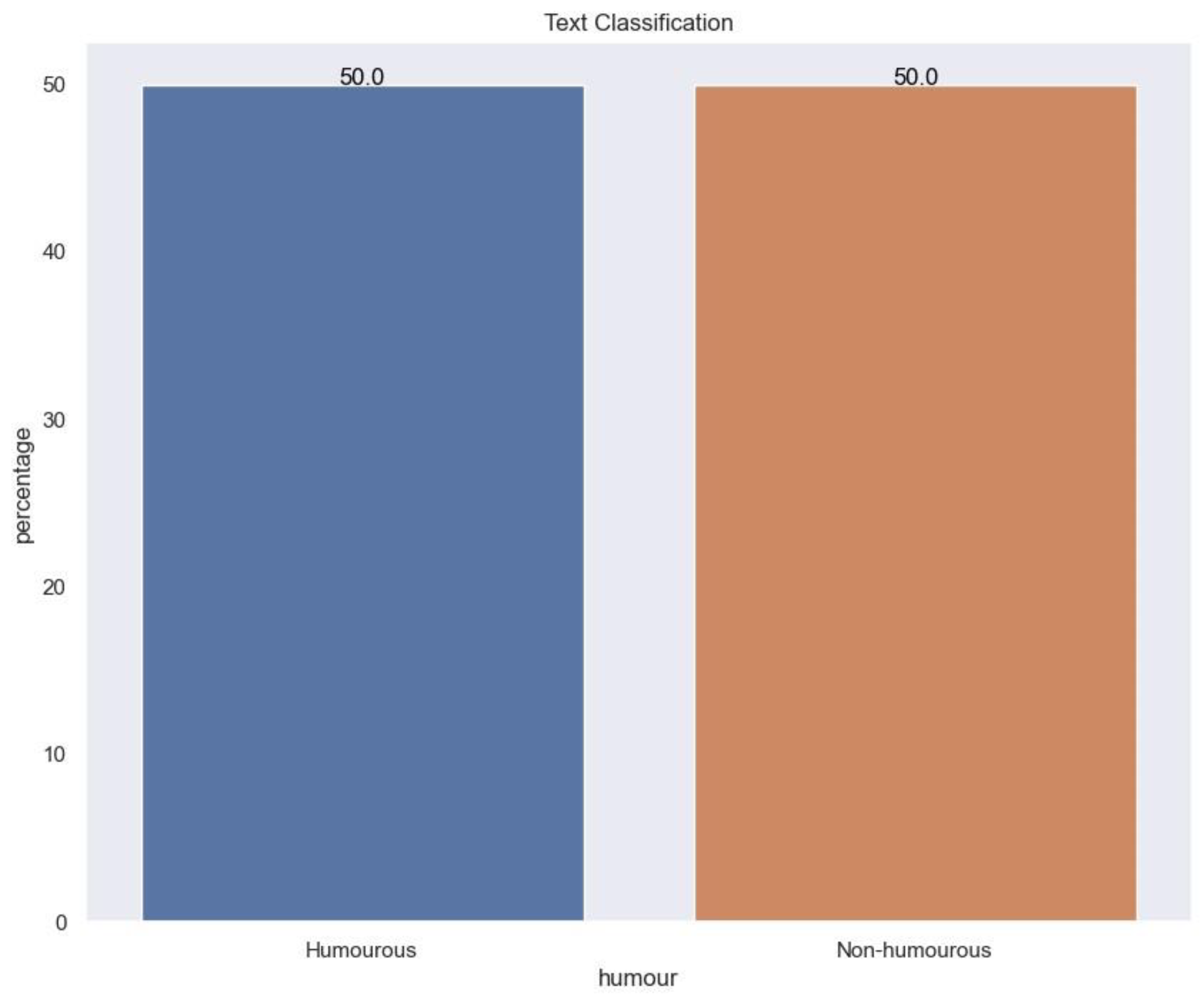

The data used in this study is the 200k short text dataset on Kaggle [

10]. The dataset contains 200,000 datapoints evenly distributed between humourous and non-humourous as shown in

Figure 1. The dataset was introduced by Issa Annamoradnejad and Gohar Zoghi in their research study “

ColBERT: Using BERT Sentence Embedding for Humor Detection”. They extracted the data from Reddit communities and Huffington

Post online news magazines and was pre-processed for the purpose of humour detection tasks [

11].

3.2. Pre-Processing

The contractions such as “I’ve”, “I’m”, “you’ve” and so on were expanded, by utilizing a contraction map (CM). Further, stem the text, removed punctuations, emojis and numbers, converted to lowercase and removed special characters. No stop words such as ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘not’ and so on were removed. Although stopwords have little semantic meaning their removal reduces the dimensionality of the text thereby removing potential noise in the dataset. However, in humour detection task it is important to consider the context of the text as some jokes rely on stopwords for their jocular effect, removing it could alter the linguistic pattern of the joke [

13]. For example, the stopword ‘not’ which means to negate, if removed could alter the meaning of the text. The data was labelled as True and False indicating humourous and non-humourous respectively. I assigned 1 to Humourous and 0 to non-humourous using one hot encoding. We used the ratio split, 80:20 for train and test. Out of 80, we used 80:20 ratio split for test and validation.

3.3. Word Embedding Techniques

Given that most machine learning algorithms are unable to handle text data but numerical data, it is essential to represent these data in numerals. Word embedding are vector representation of words. They are capable of capturing semantic and synthetic similarities of words in relation to other words [

13]. Examples of such techniques are GloVe, FastText and Word2Vec.

A.FastText

FastText exploit sub-word information to construct word embeddings. Representations are learnt of character

ngrams, and words represented as the sum of the

n-gram vectors. This extends the word2vec type models with subword information. This helps the embeddings understand suffixes and prefixes. Once a word is represented using character

n-grams, a skip-gram model is trained to learn the embeddings [

14]. FastText can handle morphological and compositional structures, as a result we will use it for our task in order to take advantage of its subword-aware embeddings, which can be used to identify linguistic patterns indicative of humour.

B.GloVe Embeddings

GloVe (Global Vectors), a well-known word embedding technique, combines a word matrix for the word cooccurrence of matrix from the data. GloVe represents the presence or absence of words in a document using the global matrix factorization method. The GloVe model's objective is to produce word vectors such that the dot product of any two vectors is equal to the logarithm of the likelihood that they will occur together. This method enhances the representation of word semantics and aids in the capture of meaningful relationships between words [

15] as a result will be used as an embedding in this study.

3.4. Classification Models

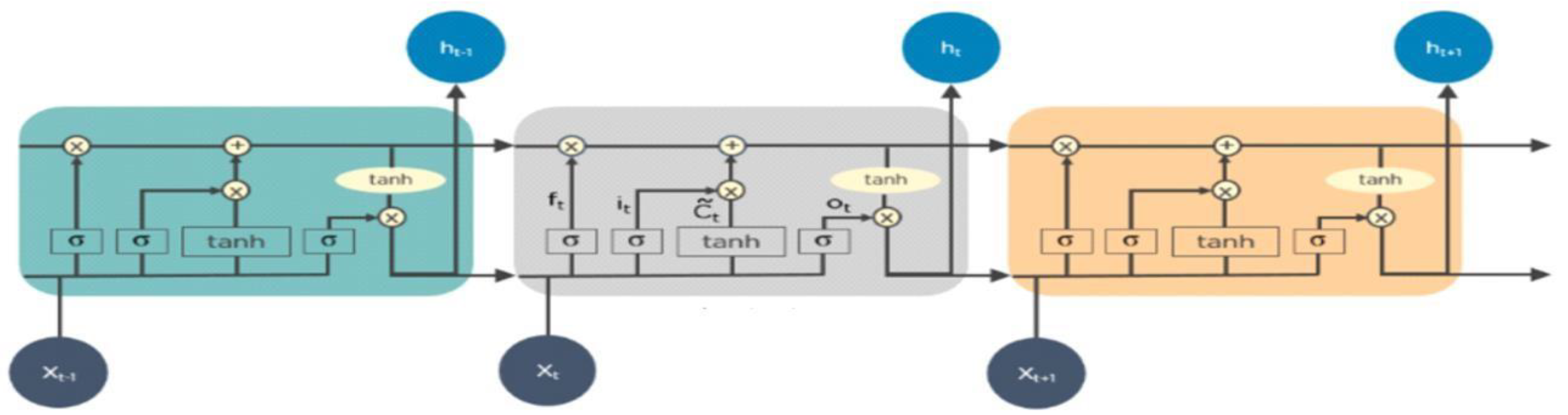

A.LSTM

LSTM is an improved variant of RNN that is able to learn long term dependencies while also resolving the vanishing gradient problem by adding a mechanism to control information and enable long-term memory [

13]. In summary, the LSTM design consists of these three gates and a memory cell. The first gate which is the forget gate, decides which information should be thrown away from the cell, the second gate known as the input gate decides the information to be stored in the cell and the last gate which is the output gate decides which information to output [

18]. This is represented in

Figure 3.

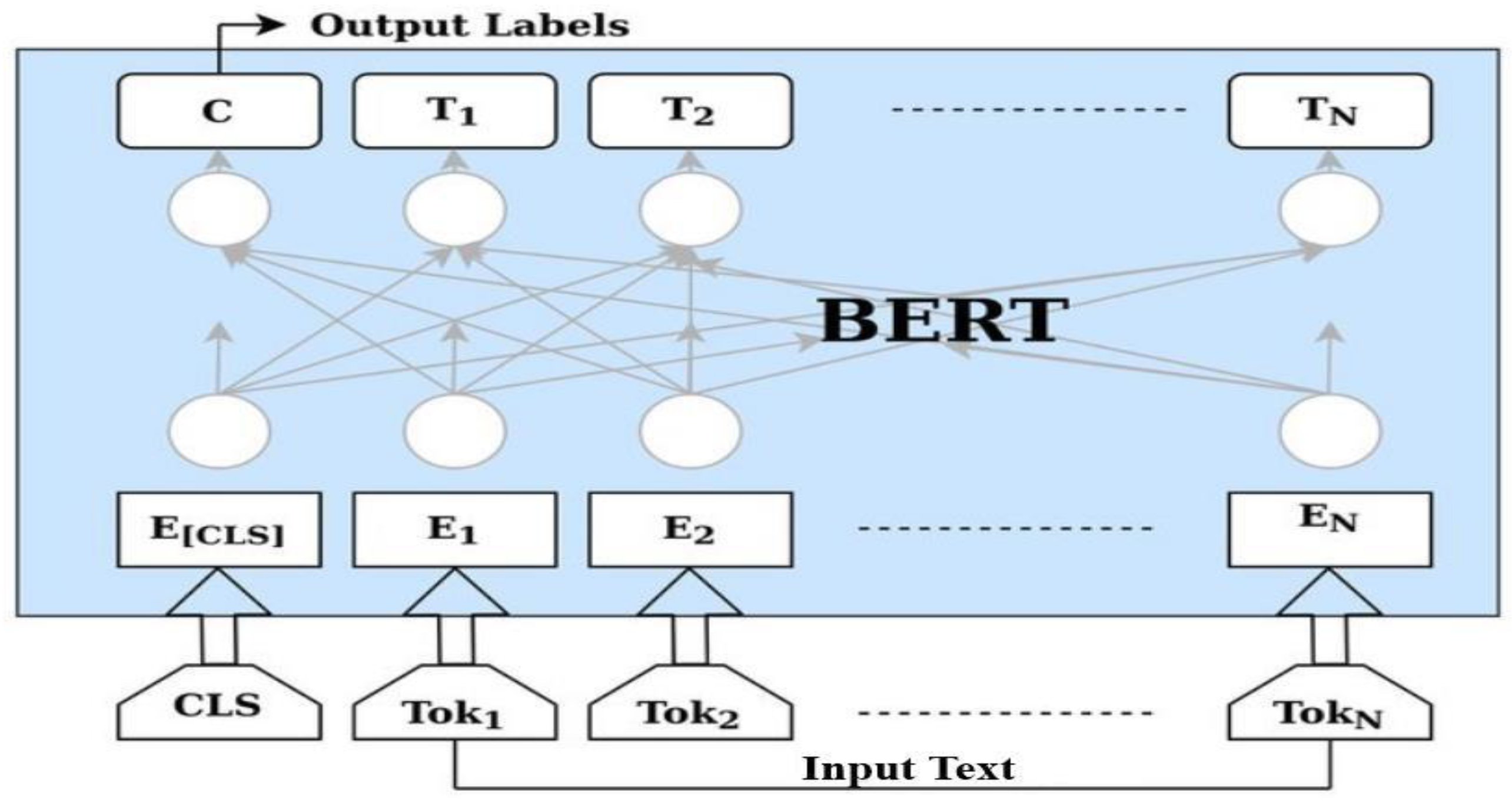

B.BERT

BERT is a transformer-based model that was self-supervised pretrained on a corpus. Without human labelling, it learns from unlabeled texts and generates inputs and labels automatically. Masked language modelling (MLM) and next sentence prediction (NSP) are the model's two pretraining goals. BERT learns bidirectional representations of sentences by randomly masking 15% of the words in a sentence and predicting those words. In NSP, BERT joins together pairs of masked sentences and determines whether or not they follow one another. BERT gains a thorough understanding of the language through pretraining with these goals, enabling it to extract helpful features for subsequent tasks and learning the contextual meaning of words by considering the surrounding words and their contexts which is an essential to learn hidden patterns for humour specific task. The BERT Base model generally consists of 12 blocks transformer, and a maximum sequence length of 512 tokens [

12]. The model’s framework is represented in

Figure 4.

C.DISTILBERT

Distillation-BERT is different version of BERT that possesses half its parameters while retaining 97% of its performing abilities. Using, BERT as a teacher, it was trained by using a bigger model or ensemble model and building a lighter model to imitate the bigger one. DistilBERT has the same architecture as BERT except that it is lighter. It underwent three objectives during training. First, the distillation loss, which was trained to produce probabilities that matched those of the BERT base model. Second, masked language modelling (MLM), where 15% of the words in a sentence were randomly omitted, and it learned to predict the omitted words. Finally, using the cosine embedding loss, DistilBERT was trained to produce hidden states that closely resemble those of the BERT [

17].

D. Naïve Bayes Multinomial (MNB)

Naïve Bayes is a probabilistic machine learning model that is based on the Bayes theorem, which determines the likelihood of a hypothesis based on previously known information and fresh data [

19].

Bayes Theorem;

Here

A and

B are events, the probability of event A occurring is given that event B has occurred. Here,

P(

B) is the evidence/data and

P(

A) is the probability of the hypothesis. The assumption made here is that the features are independent. It operates by computing the prior probabilities for each class labels, determining the likelihood probability with each attribute for each class, placing these values in Bayes Formula and calculate posterior probability and then observe which class has a higher probability, given the input belongs to the higher probability class. Naïve Bayes has been found to outperforms most machine learning classifiers in humour prediction [

5], due to its simplicity and being computationally less expensive will be used in this research.

3.5. Experiments Setup

We trained an LSTM model using two different embeddings. first, I combined the LSTM model with pre-trained 300-dimensional GloVe embedding to initialize the embedding layer for the input text. Second, combined LSTM with 300-dimensional FastText embedding for the input text. The LSTM model in both cases had the same architecture. I initialized the embedding layer with the pre-trained word vectors. The model architecture consists of two LSTM layers with 128 and 64 units, respectively. The first LSTM layer was set to capture sequential information. After each LSTM layer, a dropout layer of 0.4 was introduced to prevent overfitting and improve generalization. The output layer of the model had two units with softmax activation, enabling binary classification. Compiled the model with the Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss for training. To control model complexity, we applied L2 regularization with a coefficient of 0.01 and trained using 10 epochs and a batch size of 32.

The implementation of the pre-trained models involved leveraging BERT and DistilBERT language models for word embeddings so as to learn contextual information. The models were implemented using the same architecture. First, I initialize tokenizer of each pretrained model respectively, the tokenizer function takes in the text data and a maximum sequence length of 128 and call the tokenizer_encode_plus function to tokenize the text. This encodes the text into a sequence of integers, we also padded sequence to the specified maximum length, and truncate anything outside this length. The models take input IDs and attention masks, which were specified as input layers. We applied a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) layer with 128 units and captured sequential information from the embeddings. To enhance the model's ability to focus on important features, we introduced an Attention mechanism to compute attention scores and aggregate the most relevant features. To summarize the features, we added global average pooling and global max pooling layers. The outputs from both pooling layers were concatenated, and a dense layer with 256 units and ReLU activation was introduced for classification. Dropout of 0.5 was applied to reduce overfitting. The final output layer used softmax activation. Compiled the model with the Adam optimizer, a learning rate of 1e-5, and categorical cross-entropy loss and trained using 5 epochs and a batch size of 32.

To implement the Multinomial Naive Bayes model for text classification, I started by using the CountVectorizer to convert the text data into numerical features. This vectorization technique represents the frequency of each word in the text as a numerical value. Then, we applied Term Frequency - Inverse Document Frequency (TFIDF) to provide informative representations of the text by considering the importance of each word relative to the entire corpus. I trained the Multinomial Naive Bayes classifier on the TF-IDF transformed data and evaluated on both validation and test datasets.

4. Results

From

Table 1, BERT model did essentially well when viewed alongside the other models, the model had an F1score of 97% while DistilBERT had an F1-score of 96%. LSTM also performed well with an F1-score of 94% and 95% when FastText and GloVe embeddings were used. However, LSTM did not perform as well as the other transformer models. Lastly, Naïve Bayes Classifier which is a commonly used machine learning classifier for text classification performed the lowest in this study, with an accuracy of 91%. Furthermore, each model performed effectively well when the overall performance is considered. In this research, the state-of-art model, BERT is a better classification model. However, due to its computational load, DistilBERT which is faster and lighter can be considered.

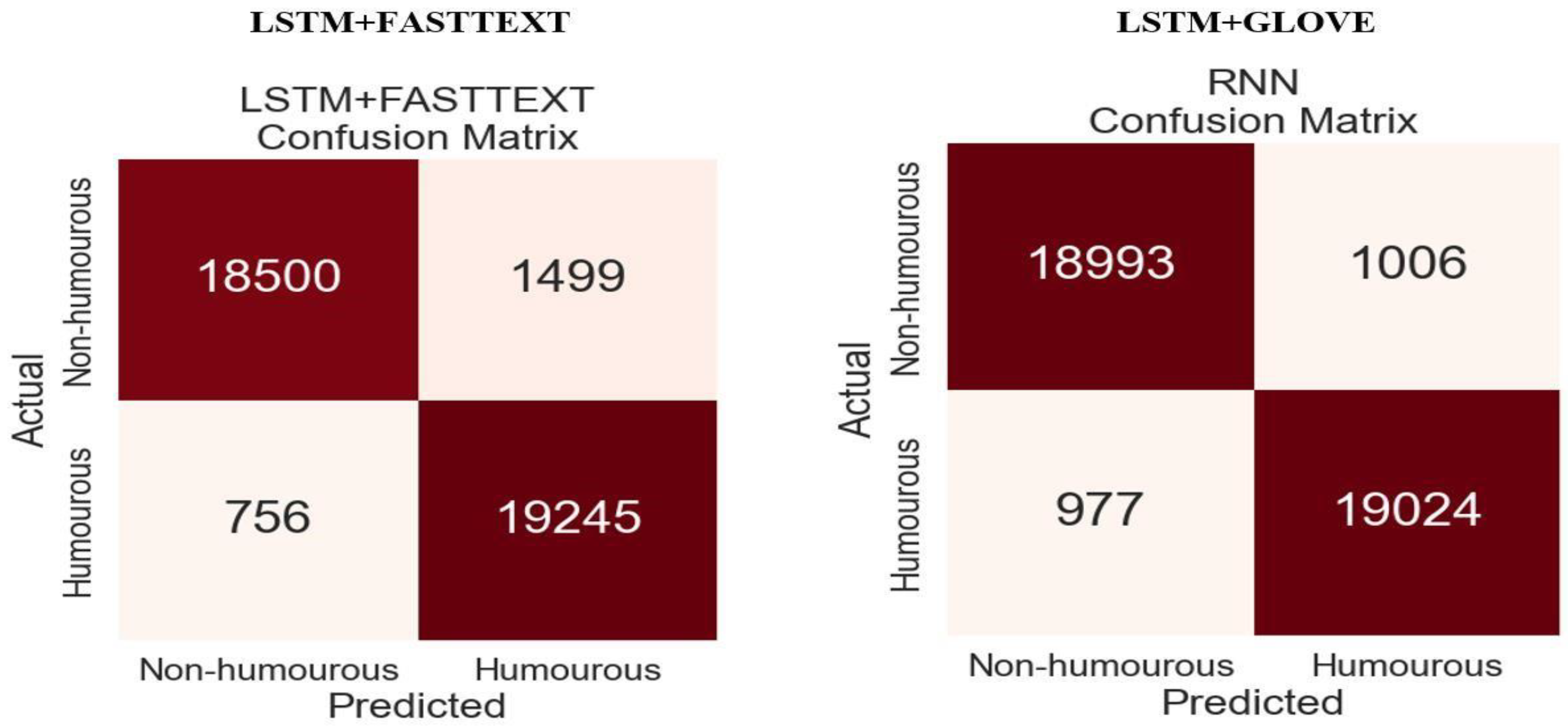

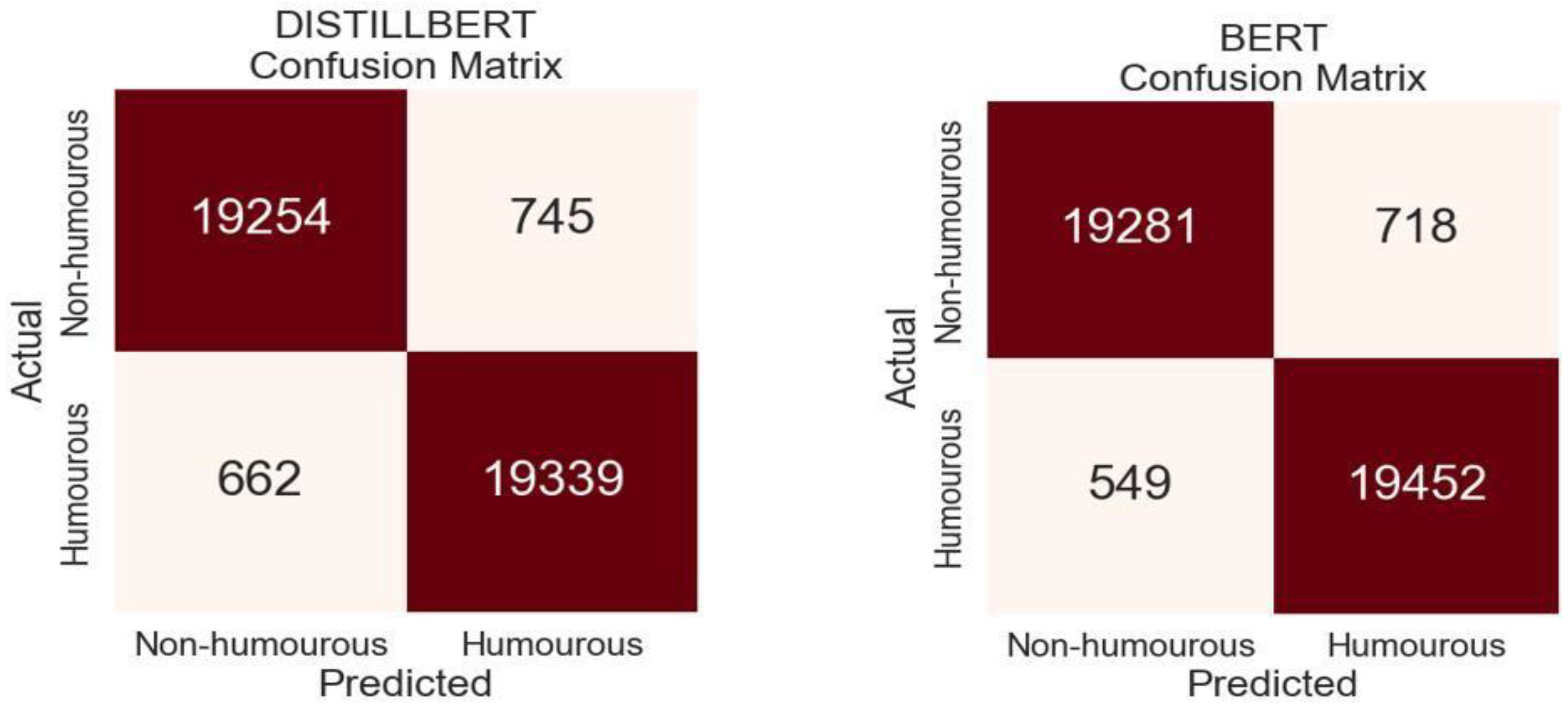

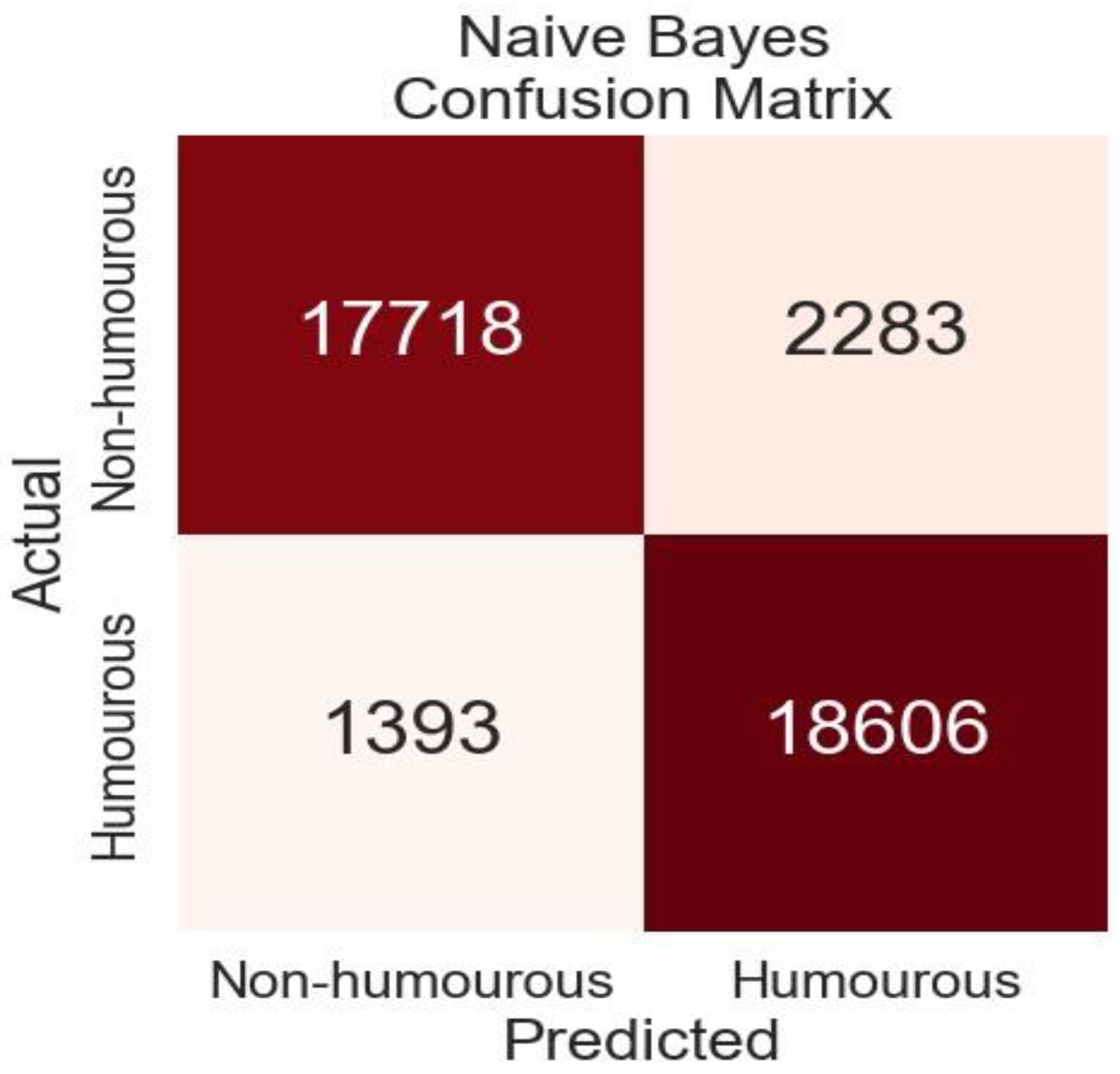

Confusion Matrix for the models is given below. The confusion matrix made a total of 40,000 predictions. The confusion matrix shows how well the models classifies data by counting the number of True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), True Negative (TN), and False Negative (FN) predictions for each class. From figures below, BERT is shown to have the highest TP and TN which indicates a high precision and high recall.

5. Discussion

Whilst this research reflects similarities with the previous work on humour detection, the researchers acknowledge the difficulty in detecting humour in text considering that humour is subjective in nature [

2] – [

1]. The outcomes from the various models and classifiers show that both conventional machine-learning and deep-learning techniques are effective for detecting humour. [

5] implemented Naive Bayes classifier for humor detection and achieved accuracy ranging from 73.22% to 96.67% for different datasets, while our research utilized datasets different from [

5], the F1-score of 91% attained falls within the same range. This suggests that conventional approaches can be competitive and provide a strong foundation for humour detection tasks. Furthermore, the performance of word embeddings (FastText and GloVe) on LSTM achieved an accuracy of 94% and 95% respectively, which is high compared to the “DeepHumour” system of combining CNN and LSTM layers proposed by [

4] whose accuracy was 89%. Although the “DeepHumour” technique is able to capture contextual and long-term dependencies of the sequence, however, using the vectors generated by pretrained embeddings as input for LSTM considerably captures the semantic, morphological, contextual and long-term dependencies which can enable the model achieve a high accuracy. However, when [

7] utilized GloVe and BERT embeddings with machine learning techniques the highest accuracy attained was 69% which is not as high when compared to our technique because the training dataset used was considerably small (5000 data points).

The inclusion of transformer-based models, BERT and DistilBERT has shown advancements in performance. BERT achieved an F1-score of 97% while DistilBERT had 96%. This demonstrates the ability of transformer architectures to capture dependencies and complex language expressions making them well suited for tasks like humor detection. The exceptional performance of the DistilBERT model although it is a distilled version of BERT suggests that it can be highly effective reducing computational expenses and yielding outstanding accuracy, therefore, in situations where computational resources are limited, opting for DistilBERT may be more favorable. More so, the accuracies attained in our study are consistent with previous studies carried out on humour detection.

From the findings, it becomes evident that there are two elements in attaining a high level of accuracy in the current task. Firstly, the significance of sentence and word embeddings is clearly observable. The transformer models make use of their embeddings resulting in an accuracy rate that surpasses LSTM combined with FastText and GloVe by 1% and 2%. On the other hand, the conventional approach to word representations, like TF-IDF failed to surpass a threshold when used alongside Naïve Bayes. Second, although deep learning techniques are computationally expensive, it is interesting to note they outperformed machine learning techniques as a result of being able to learn complex linguistic patterns in the text. Overall, this answers the research questions given in chapter 1.

As natural language systems advance and become universal through human-centered systems like chatbots, virtual assistants, customer service systems and other IOT devices, it is paramount to develop humour-aware systems and integrate them into these human-centered systems so as to understand humour and be able to detect when a user is being joking. An interesting application involves deciding whether an input text warrants being taken seriously or not, which is essential to understand the sentiments behind a user’s query, return helpful solutions, and enhance the user's experience. According to [

20], social robots could serve as trustworthy aids in therapeutic interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders as well as amiable helpers for children and the elderly. Due to this, social robots must interact with human beings in highly fluid ways in order to establish meaningful associations. In other words, Social robots must be able to recognize and respond to a variety of human inputs, including humour in interactions.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide evidence for the idea that deep learning approaches, those based on transformer architectures offer advantages over traditional machine learning methods due to their ability to learn contextual meaning of words and complex linguistic patterns. This Study’s analysis indicates that while all the techniques used were able to detect humor, the novel models performed better than the others. BERT which is a state-of-art model performed the highest with an F1-score of 97%. Furthermore, though the accuracies the models attained are significantly high, they might not accurately reflect the subtleties of humour as humour is subjective, hence in future it is necessary to increase the robustness of models to cover a range of humour styles like sarcasm, pun e.tc. Additionally, more than just the conventional metrics used in this study and some previous studies, additional information about the detection of potential biases or limitations such as misinterpretation of humour leading to false negatives and positives that might not be obvious from just the use of these quantitative metrics can be obtained from human evaluation due to the subjectivity [

8].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O. and C.C.; methodology, P.O.; software, P.O. and C.C.; validation, P.O.; formal analysis, P.O.; investigation, P.O.; resources, C.C and P.O.; data curation, P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, P.O. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, P.O., C.C. and O.O.; visualization, P.O.; supervision, C.C and O.O.; project administration, P.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Algorithms 2024, 17, 572 18 of 19.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kirsh, G.A.; Kuiper, N.A. Positive and negative aspects of sense of humor: Associations with the constructs of individualism and relatedness. HUMOR 2003, 16, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraj, R. and Aono, M. (2021) “Humour detection using a bidirectional encoder representations from Transformers (BERT) based neural ensemble model,” 2021 8th International Conference on Advanced Informatics: Concepts, Theory and Applications (ICAICTA) [Preprint]. Available at. [CrossRef]

- Trueman, T.E.; K, G.; J, A.K. Online Text-Based Humor Detection. 2021 International Conference on Disruptive Technologies for Multi-Disciplinary Research and Applications (CENTCON); pp. 313–316.

- Kumar, V.; Walia, R.; Sharma, S. DeepHumor: a novel deep learning framework for humor detection. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 16797–16812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, R.; Strapparava, C. Making computers laugh. In Proceedings of the conference on Human Language Technology and Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing - HLT '05; pp. 531–538.

- Garbowicz, K. and Chen, L. (2021) ‘DilBERT2: Humor Detection and Sentiment Analysis of Comic Texts Using Fine-Tuned BERT Models’, Delft University of Technology, Bachelor Seminar of Computer Science and Engineering [Preprint].

- Khatri, A.; P, P. Sarcasm Detection in Tweets with BERT and GloVe Embeddings. Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Figurative Language Processing; pp. 56–60.

- Weller, O.; Seppi, K. Humor Detection: A Transformer Gets the Last Laugh. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); pp. 3619–3623.

- Patel, K.; Mathkar, M.; Maniar, S.; Mehta, A.; Natu, S. To laugh or not to laugh – LSTM based humor detection approach. 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); pp. 1–7.

- Devastator, T. (2022) Reddit: /r/jokes, Kaggle. Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/thedevastator/unlock-reddit-s-humorous-side-analyzing-reddit-s (Accessed: 11 July 2023).

- Annamoradnejad, I.; Zoghi, G. ColBERT: Using BERT sentence embedding in parallel neural networks for computational humor. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; et al. (2019) ‘BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding’, in NAACL HLT 2019 - 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies - Proceedings of the Conference, pp. 4171–4186. Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.04805.pdf.

- Wang, D.; Su, J.; Yu, H. Feature Extraction and Analysis of Natural Language Processing for Deep Learning English Language. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 46335–46345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Enriching Word Vectors with Subword Information. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguistics 2017, 5, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

- D'Sa, A.G.; Illina, I.; Fohr, D. BERT and fastText Embeddings for Automatic Detection of Toxic Speech. 2020 International Multi-Conference on: “Organization of Knowledge and Advanced Technologies” (OCTA); pp. 1–5.

- Sanh, V.; et al. (2020) Distilbert, a distilled version of Bert: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter, arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.01108 (Accessed: 16 July 2023).

- Seabe, P.L.; Moutsinga, C.R.B.; Pindza, E. Forecasting Cryptocurrency Prices Using LSTM, GRU, and Bi-Directional LSTM: A Deep Learning Approach. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naulak, C. (2022) A comparative study of naive Bayes classifiers with improved technique on text classification [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Ritschel, H.; André, E. Shaping a social robot’s humor with Natural Language Generation and socially-aware reinforcement learning. Proceedings of the Workshop on NLG for Human–Robot Interaction; pp. 12–16.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).