1. Introduction

Protein protease or peptidase inhibitors (PPIs) are essential bioactive molecules throughout living organisms. These inhibitors play critical roles in many fundamental biological processes, from embryogenesis to aging and death, as well as in pathologies, parasitism and infections, among others [

1]. They have, therefore, strong biological and biotechnological importance, and arise growing focus. In plants, PPIs are also involved in an array of key functions like seed germination, plant development and growth, flowering, maturation and senescence, plant protection against predators and pests, biotic and abiotic stress [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Noteworthy is also the controversial anti-nutritional properties of plant protease inhibitors, and its health impact [

6]. Understanding the structure and function of PPIs can lead to advancements in agriculture and medicine, and particularly in the development of new biotechnological applications.

The knowledge on specific plant protein protease inhibitors, and their roles is notable but still demanding, especially given their significance in agriculture, nutrition, and health. In the widely used MEROPS database such molecules are classified in 35 families within a conjoint of 108 families for all living species [

7]. Thus, well-known and intensively cultivated plants like

Solanum tuberosum (potato),

Glycine max (soya), or

Triticum aestivum (wheat) have in such database counts above 250-300 for the numbered homologs of known and putative PPIs. These are significant and initially unexpected high numbers, occupying such inhibitors together with the target proteases a considerable percentage of the genome of their species. They are subdivided, regarding specificity, in inhibitors of serine- (the major group), cysteine-, aspartic-, or metallo-proteases, with none or very little representation in those related with glutamic-, asparagine-, threonine-proteases or other variants, in contrast with what is found in the general protease database. At the conformational point of views, by now, at MEROPS there are 40 clans or folding types containing plant PPIs, that group inhibitors in families that show similarities in three-dimensional structures [

7]. However, another more restricted structural classification, pedagogically described in a study covering 6700 plant PPIs made by Hellinger & Gruber [

2], considers nowadays 12 well recognized fold types of plant PPIs, of which phytostatins, serpins, kunitz-type, potato-type.1, Bowman Birk-type and cyclotides are among the most populated. Overall, although the structural knowledge about is significant, much still is left to complete and to integrate/facilitate such knowledge for drug discovery and related biotechnological and therapeutic purposes.

Among the alimentary plants traditionally used in LatinoAmerica

Chenopodium spp (quinoa),

Amaranthus spp (amaranto/amaranth) and

Lupinus mutabilis (lupino/lupine/Andean or pearl lupin) emerged among the species that raised great prominence nowadays because of nutritional interest, such as their large and equilibrated content in proteins and constituent amino acids, as well as other beneficial nutrients [

8,

9]. Because of its potential utility, controversial value and molecular differentiation of variants, we are studying in the seeds of such species the content and properties of protein inhibitors of proteases, and particularly of serine proteases, found there at significant levels and potency [

9]. In the present work, and taking trypsin as a model for serine proteases, we found that among the seeds of such alimentary plants from Andean countries, the ones from two tested amaranth species,

A. hybridus (or sangorache) and

A. caudatus (also known as kiwicha) had the highest inhibitory capability on trypsin, an activity already reported for such pseudocereals. Also, both displayed higher molecular homogeneity and scalability regarding the ones from the other two here tested species, quinoa (

Chenopodium quinoa L.) and lupine (

Lupinus mutabilis).

In this work, with the affinity-proteomics Intensity-Fading MS approach [

10], we visualised not only the active forms of all four inhibitors from their natural extracts, including the two at very low concentrations (quinoa and lupine), but also we quickly isolated the inhibitors from the two tested amaranths, showing they have identical masses and mass-fingerprints by MALDI-TOF.MS. Subsequently, after a preparative purification by affinity chromatography of the inhibitor from

Amaranthus caudatus species, here called ATSI as in an initially related report [

11], we made a complex with porcine trypsin and characterised it in the isolated and complex state. Also, successfully crystallised the complex and solved its three-dimensional structure by X-ray crystallography, clarifying the detailed inhibitory mechanism and determinants. Besides, the capability of such inhibitor(s) to affect the growth of microbial species known to be plant diseases, as described by other protease inhibitors [

5], as well as other capabilities of biotech/biomed interests, have been investigated. We expect that the study can clarify the role of these plant protease inhibitors and related, facilitate future studies, applicative uses and developments based on the here analysed molecules, as well as nutritionally-related knowledge and strategies.

2. Results

2.1. Trypsin inhibition dose-response curves, inhibitory capabilities and identification of inhibitory species

Relying on previous prospective analysis, the aqueous extracts from the seeds of selected four Latino America distinct plants, Chenopodium quinoa (quinoa), Amaranthus hybridus (sangorache), Amaranthus caudatus (kiwicha) and Lupinus mutabilis (chocho, Andean lupin) were analysed for the content on peptide/protein inhibitors of trypsin, as one of the main and more representative serineproteases. Previously, the different seeds, after milled as fine flours, were defatted with 1-propanol (1:4 v/v, solid/liquid), stored at 4ºC in dry state, and extracted before analysis with a TrisHCl-NaCl buffer (pH 8.0).

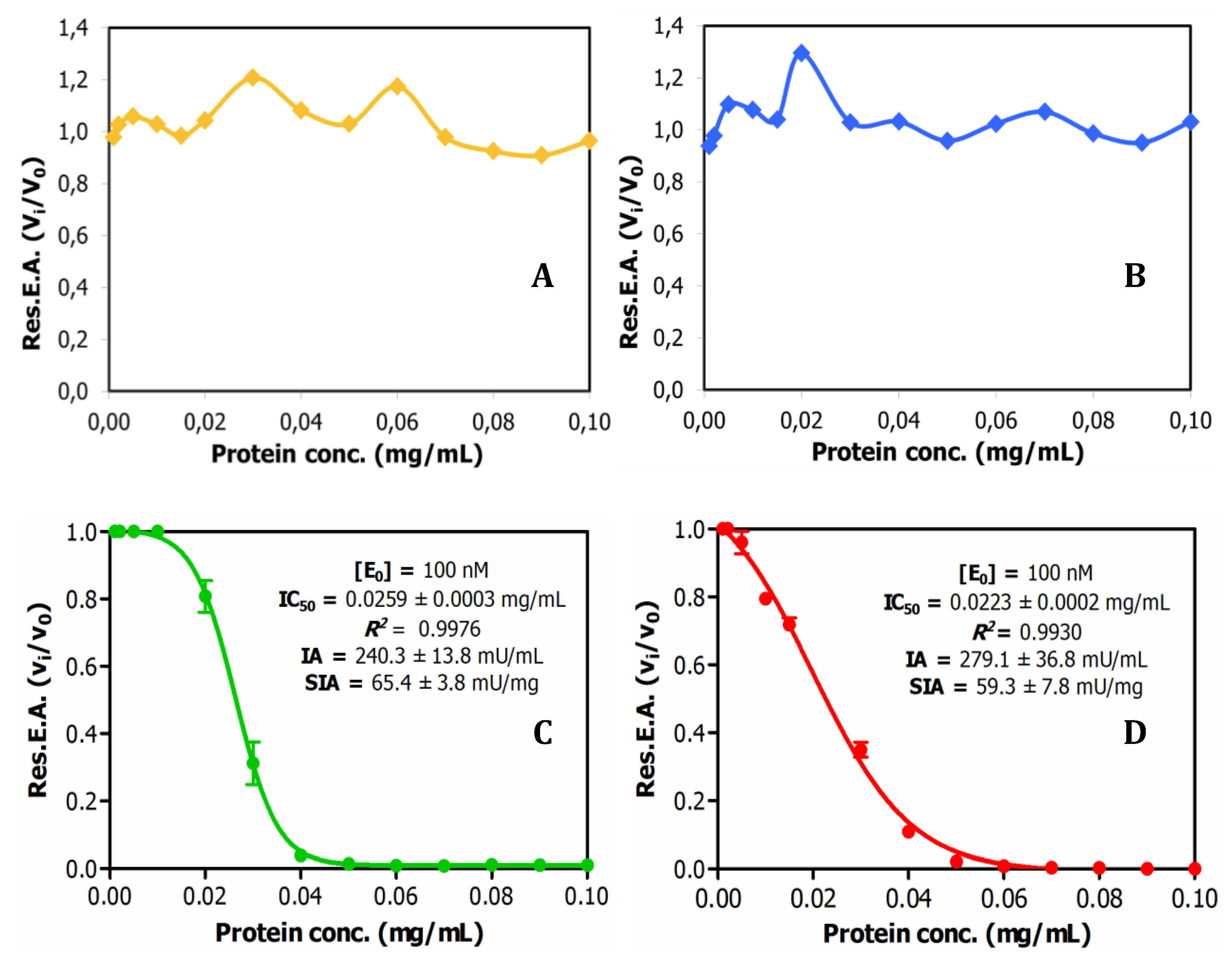

Figure 1.

Dose-response relationships for trypsin inhibitory activity in crude plant seed extracts and derivation of IC50 values. Effects of different doses of crude extracts on trypsin activity: (A) Quinoa; (B) Lupine; (C) Amaranthus hybridus (sangorache); and (D) Amaranthus caudatus (kiwicha). 1.0mM BAPNA was used as substrate. Res.E.A.: Residual Enzymatic Activity. IA: inhibitory activity. SIA: specific inhibitory activity.

Figure 1.

Dose-response relationships for trypsin inhibitory activity in crude plant seed extracts and derivation of IC50 values. Effects of different doses of crude extracts on trypsin activity: (A) Quinoa; (B) Lupine; (C) Amaranthus hybridus (sangorache); and (D) Amaranthus caudatus (kiwicha). 1.0mM BAPNA was used as substrate. Res.E.A.: Residual Enzymatic Activity. IA: inhibitory activity. SIA: specific inhibitory activity.

Subsequently, the protein content of the extracts was analysed by the bicinconnic acid chemical method. The extracts displayed a considerable protein content, particularly in the case of the lupine seeds, as shown in

Table S1. Such content was essentially kept after application of two alternative clarification analytical procedures, TCA at 2.5% (w/v) or heating treatment at 65ºC, traditionally used in this field to remove unwanted materials (

Table S1). However, when titration activity curves of trypsin inhibitory capability were obtained, through adding increasing volumes of these extracts on model bovine trypsin, such biological activity was only initially detected in the derived plots for the two tested amaranth species, the

A. hybridus and the

A. caudatus, but not for quinoa and lupine, as shown in Fig1. This indicates that the inhibitory capability or content on the searched inhibitory species is significant in the two amaranth species but low in the two other ones. Interestingly, from such dose-response or titration curves, IC50 parameters were derived for the

A. hybridus and

A. caudatus samples, with values of 0.0259 +/- 0.0003 mg/l and 0.023 +/- 0.0002 mg/mL. This is indicative of very high inhibitory capabilities for both extracts and inhibitory molecules that they contain, as well as of their low Ki values, as confirmed in subsequent experiments.

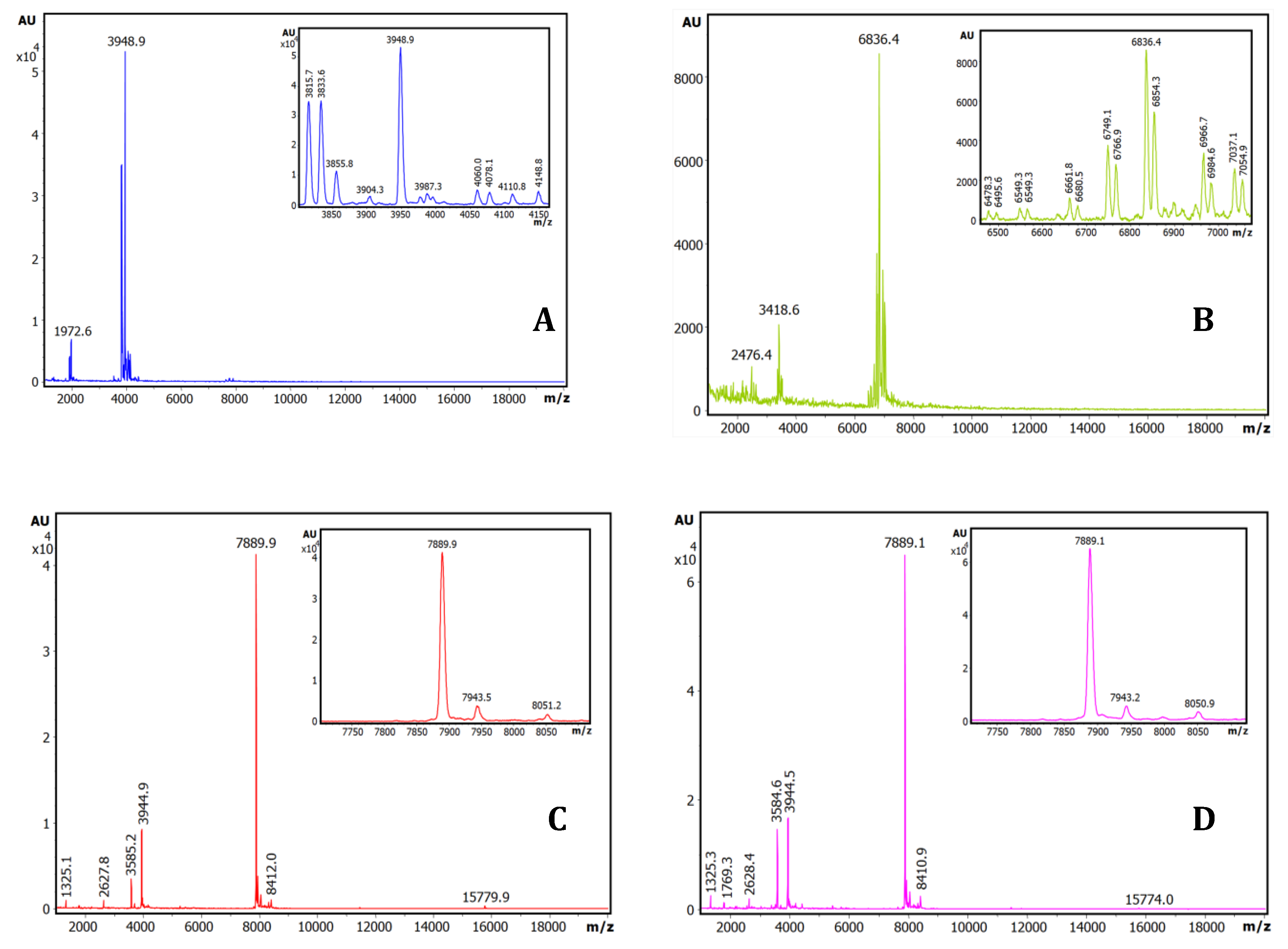

Figure 2.

Identification of trypsin inhibitors by Intensity-Fading MALDI-TOF MS in crude plant seed extracts on bovine trypsin-glyoxal SepharoseR. Stack view of the mass spectra from plant extracts corresponding to the elution fractions of IF-MALDI-TOF MS analyses on bovine trypsin-glyoxal Sepharose® CL-4B. (A) Quinoa. (B) Lupine. (C) A. hybridus (sangorache). (D) A. caudatus (kiwicha). The elution from the affinity matrix was performed with 0.5% v/v TFA. Assays carried out in duplicate, at room temperature. See details at Methods section,

Figure 2.

Identification of trypsin inhibitors by Intensity-Fading MALDI-TOF MS in crude plant seed extracts on bovine trypsin-glyoxal SepharoseR. Stack view of the mass spectra from plant extracts corresponding to the elution fractions of IF-MALDI-TOF MS analyses on bovine trypsin-glyoxal Sepharose® CL-4B. (A) Quinoa. (B) Lupine. (C) A. hybridus (sangorache). (D) A. caudatus (kiwicha). The elution from the affinity matrix was performed with 0.5% v/v TFA. Assays carried out in duplicate, at room temperature. See details at Methods section,

Additionally, the extracts were analysed using our more sensitive and previously reported affinity-based Intensity-Fading MALDI-TOF.MS approach (IF-MS) [

10,

12,

13], combining concentration action of affinity capture in spin microcolumns or microbeads of glyoxal Sepharose matrix derivatised with trypsin [

10,

13] with high-sensitivity analysis by HPLC and mass spectrometry, overall unveiling a more positive view for all the extracts. Thus, such binding analyses clearly indicated the occurrence of distinct strongly trypsin binding molecules in all of such seeds, with m/z values in the 3900-6900-7900 range values, as shown in Fig.2. The efficient derivatisation procedure of the affinity matrix used, allowing to reach a high content and activity of the immobilised enzyme (as shown in

Table S2), surely contributed to the clear visualisation of the mentioned binding species for all of them.

To better identify the molecules responsible of such strong binding capabilities (probably inhibitors), the same affinity-based IF-MS approach at semi-preparative levels, in larger centrifugal microcolumns, was applied to the seeds extracts of the four plant species, using the trypsin-Sepharose matrix as the capturing agent. As seen in Fig.3, the main components visible after IF-MS appear at 3948.9, 6836.4, 7889.9 and 7889.1 mz/values for each species, although some spectral heterogeneity appear for the quinoa and lupine species, probably real but also indicative of the low concentration of the captured molecules that are present in the seeds. The lower intensity spectral signals at about 0.5x and 2x of the main m/z values are clearly visible for the A. hybridus and A. caudatus, signals most probably corresponding to half and double charged MALDI signals, which are also present in the other two plants (particularly for the 0.5x values).

Figure 3.

Purification and basic characterization of natural Amaranthus caudatus trypsin inhibitor (ATSI). A) Affinity chromatography of the crude extract of A. caudatus on a bovine trypsin-glyoxal Sepharose® CL-4B column. Equilibration, loading and washing buffer at pH 8.0, at room temperature. The elution buffer at pH 2.0 released the ATSI peak of trypsin inhibitory activity. B) SDS-PAGE analysis of the trypsin affinity chromatography fractions of ATSI, run in 15% of acrylamide gel. Lanes 1 and 2: loading and get-through fractions; lanes 3 to 6: washing fractions nº 1, 4, 8 and 12, respectively; lane 7: ATSI elution peak of trypsin inhibitory activity. C) MALDI-TOF.MS spectrum of purified ATSI. Spectral acquisition, using DHAP as matrix.

Figure 3.

Purification and basic characterization of natural Amaranthus caudatus trypsin inhibitor (ATSI). A) Affinity chromatography of the crude extract of A. caudatus on a bovine trypsin-glyoxal Sepharose® CL-4B column. Equilibration, loading and washing buffer at pH 8.0, at room temperature. The elution buffer at pH 2.0 released the ATSI peak of trypsin inhibitory activity. B) SDS-PAGE analysis of the trypsin affinity chromatography fractions of ATSI, run in 15% of acrylamide gel. Lanes 1 and 2: loading and get-through fractions; lanes 3 to 6: washing fractions nº 1, 4, 8 and 12, respectively; lane 7: ATSI elution peak of trypsin inhibitory activity. C) MALDI-TOF.MS spectrum of purified ATSI. Spectral acquisition, using DHAP as matrix.

To be confident of the genuine origin of the visualized main mass spectrometry signals, the MS-MALDI spectra of the crude extracts of A. caudatus, of the different washes, and of the final eluted sample (in the present case using acid-based detachment of the inhibitors from the matrix), were compared, as displayed in Fig.3S. It is seen that none of the signals that appear in the lastly eluted sample, besides the main one at 7889,1 m/z, is visible neither at the initial crude samples nor at none of the washes: i.e. this happens for the 8840 m/z signal which is visible in both the crude sample and in the non-binding eluate. By contrast, due to equivalent reasons, the 8337 m/z signal, although of minor occurrence and only present in some batches, it could be a genuine binder. All these analyses, stimulated us to concentrate research on the inhibitor from A. caudatus species, one of the amaranths with more agricultural and nutritional interests nowadays.

2.2. Purification and mass characterization of natural ATSI.

Once the Amaranthus caudatus trypsin inhibitor of 7889.1 m/z, abbreviated here as ATSI, has been visualized as the most promising target among the assayed, we purified it with enough quantities from trustable and certificated seeds. For this, we extended the analytical affinity-based approach to the preparative level, using a 25mL CL4b.Sepharose-trypsin column, with a high-load of enzyme, with application and washing at slightly alkaline buffer (pH 8.0) followed by elution at acidic conditions (pH 2.0). The chromatographic profile, shown in Fig.3A, indicated a clean separation of a fraction with high trypsin inhibitory capability, confirmed to be practically pure by RP-HPLC (C8), PAGE analysis and high resolution MALDI-TOF.MS spectrum, shown in Figs.3B and 3C. In these conditions, such spectrum confirmed a molecular mass of 7888.7 m/z, for its single charged species, with signals at 3943.6 and 15775.7 for the 0.5 and x2 charged ones.

Table 1.

Summary of the purification procedure of ATSI from A. caudatus [Data are means (n=3) ± S.D.].

Table 1.

Summary of the purification procedure of ATSI from A. caudatus [Data are means (n=3) ± S.D.].

| |

Total protein (mg) |

Inhibitory activity (U) |

Specific inhibitory activity (U/mg) |

Yield (%) |

Purification

(fold) |

| Crude extract |

186.5 ± 0.8 |

11.1 ± 1.5 |

0.059 ± 0.008 |

100.0 ± 0.0 |

1.0 ± 0.0 |

| Peak from affinity chromatography |

1.88 ± 0.01 |

8.5 ± 0.7 |

4.5 ± 0.3 |

76.4 ± 11.7 |

75.7 ± 11.6 |

2.3. Determination of inhibitory activities, Ki value, number of cysteines and Top-Down MS sequencing analysis.

Analysis of the inhibitory activities along the purification procedure evidenced that ATSI was purified about 75-fold from the crude extract, achieving a specific inhibitory activity of 4.5 +/- 0.3 U/mg on bovine trypsin (see

Table 1 about). Deduction of the enzymatic parameters of ATSI against this enzyme, at different protein inhibitor/enzyme ratios, following the Morrison approach [

14,

15], and after enzyme titration, gave rise to an equilibrium dissociation constant value, Ki, of 1.24 +/- 0.16 nM, at 37 ºC and pH 8.0 (Fig.4). Noteworthy, the derived graphical plot was typical of tight binding inhibitors, when representing vi/vo against inhibitor concentration (at nanomolar ranges)

.

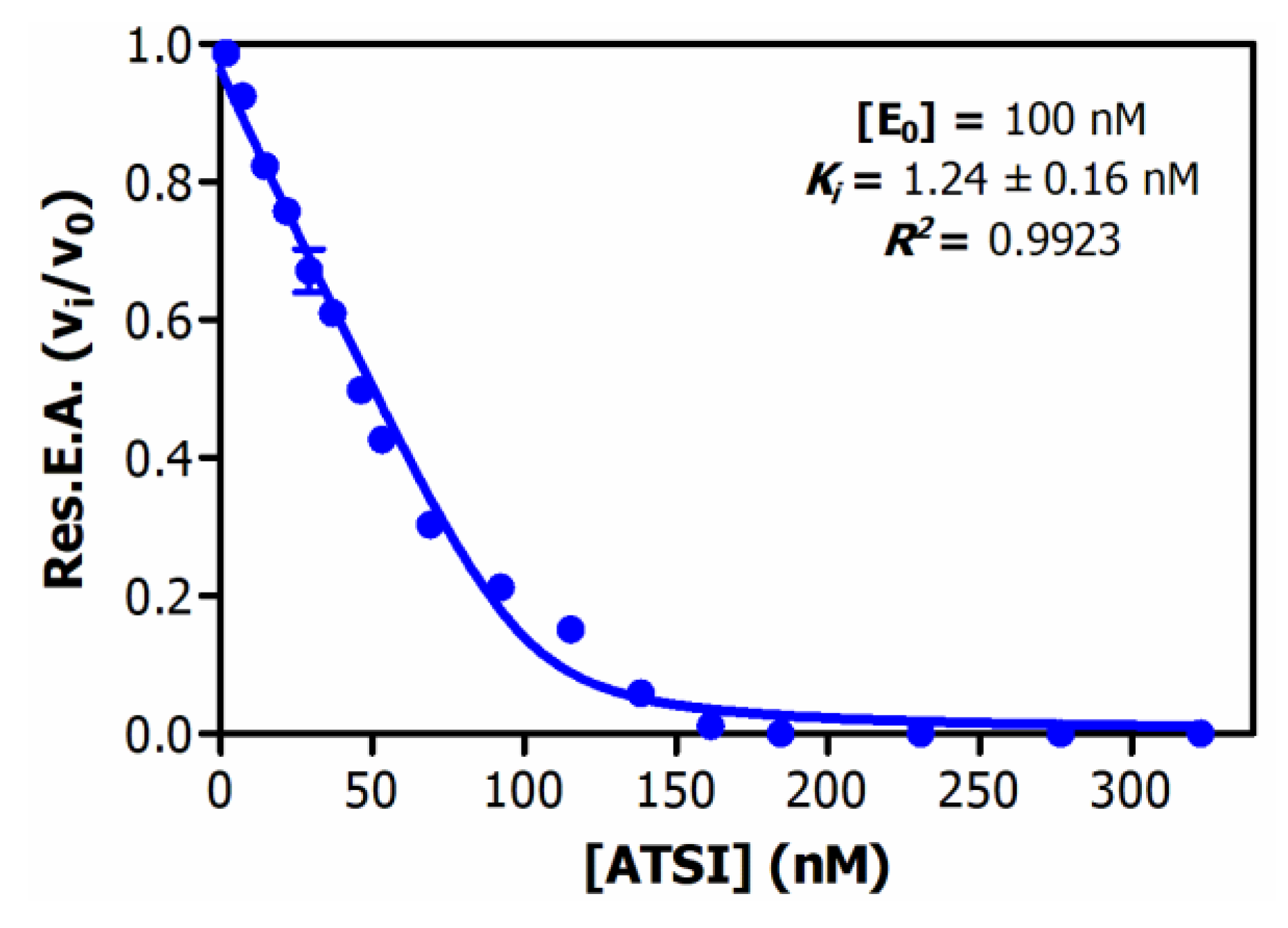

Figure 4.

Equilibrium dissociation constant (Ki) of ATSI against bovine trypsin. Assays performed with 1.0mM BAPNA substrate, in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH=8.0, 150 mM NaCl 20 mM CaCl2, 0.05% v/v Triton X-100 as activity buffer, at 37ºC. Pre-incubation: 15 min, at 37ºC. See experimental details and data treatment at Methods.

Figure 4.

Equilibrium dissociation constant (Ki) of ATSI against bovine trypsin. Assays performed with 1.0mM BAPNA substrate, in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH=8.0, 150 mM NaCl 20 mM CaCl2, 0.05% v/v Triton X-100 as activity buffer, at 37ºC. Pre-incubation: 15 min, at 37ºC. See experimental details and data treatment at Methods.

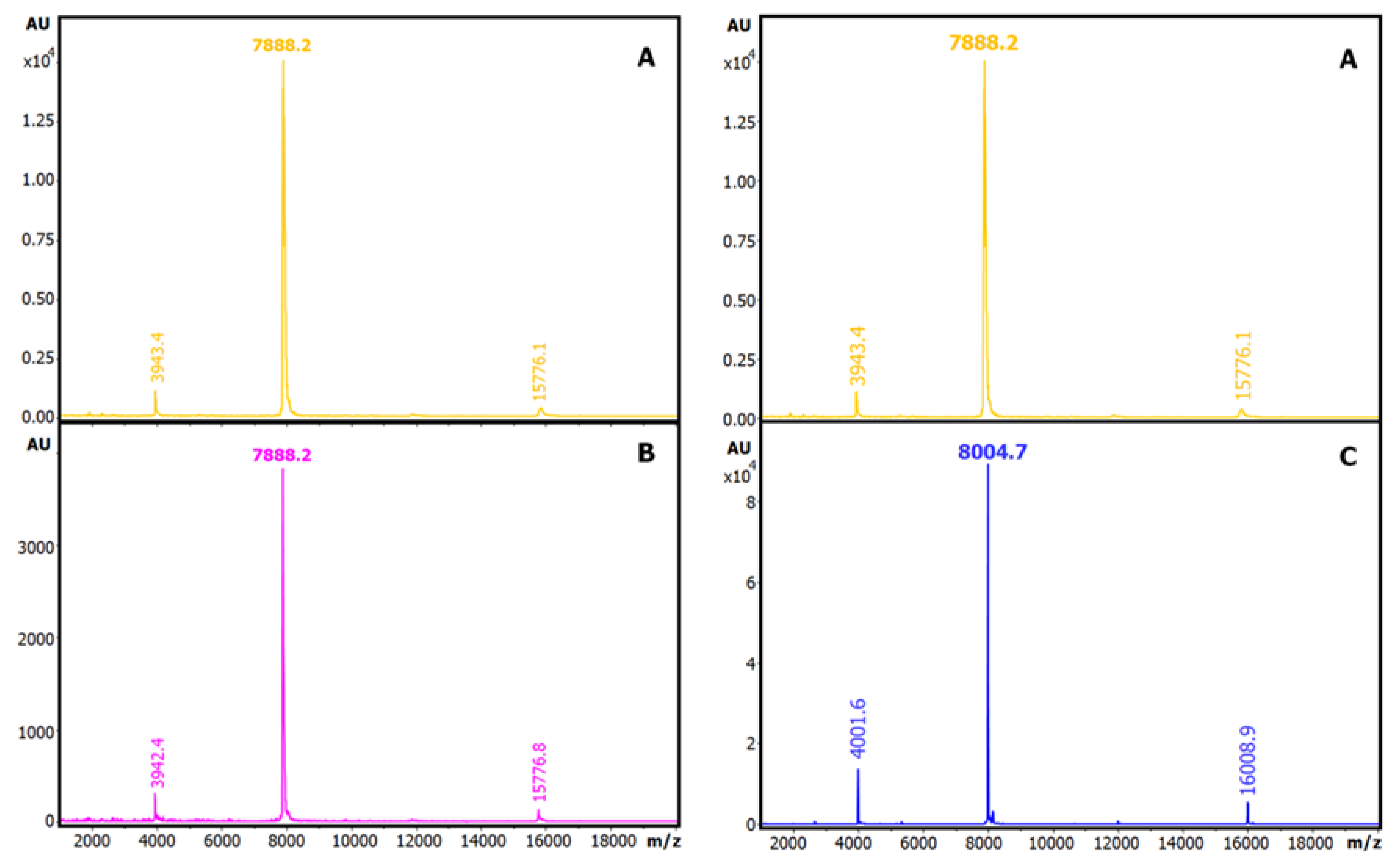

On the other hand, we analysed the number of cysteine residues in this ATSI molecule by reduction or reduction and derivatisation with iodoacetamide and MALDI-TOF.MS comparative analysis of the natural and modified variants of the molecule, shown in Fig.5. From this it appeared that ATSI becomes double carboamidomethylated with such alkylation agent, indicative of the occurrence of two cysteines in the natural molecule as a disulfide-linked cystine, with no free cysteine. The subsequent evidence on the occurrence of such two cysteines in the molecule, at positions 4 and 49, by resolution of its three-dimensional structure, confirmed they are disulfide bridged.

Figure 5.

Determination of total free and paired cysteine residues of ATSI. MALDI-TOF MS spectrum (A) of native ATSI; (B) after S-carbamidomethylation; (C) after reduction and S-carbamidomethylation. DHAP was used as a matrix.

Figure 5.

Determination of total free and paired cysteine residues of ATSI. MALDI-TOF MS spectrum (A) of native ATSI; (B) after S-carbamidomethylation; (C) after reduction and S-carbamidomethylation. DHAP was used as a matrix.

Given that all the properties of such purified molecule were coincident with those of the

A. caudatus inhibitor initially identified by J Hejgaard et al (1994) [

11], we submitted it to MALDI-TOF.MS/MS fragmentation, with ISD and CID, in the presence of the 2,5-DHB matrix, to become certain about. The derived spectra clearly displayed long fragmentation ladders, with c, y and Z+2 fragments from positions 9-46, 9-31 and 9-32, as shown in Fig.6. Very similar spectra were generated from the

A. hybridus inhibitor. All of this, together with precise identical molecular masses, 7888.7 m/z, allowed to confirm the identity of the here isolated ATSI sequence with the one above mentioned initially reported, as well as between the ATSI inhibitors found in the two amaranth species.

2.4. Formation and isolation of the ATSI-bovine Trypsin complex.

To start analysing in detail the complexes that ATSI could establish with standard serine-proteases, we assayed the formation and isolation of a binary complex of the inhibitor with bovine trypsin, as an experimental model. This was achieved by mixing both molecules in the presence a 2:1 molar excess of ATSI over trypsin, at pH 8.0 and 25ºC, in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2. After incubation of the complex for 30min., subsequent gel-filtration chromatography of the mixed sample through a Superdex 75 High load column, in the same buffer, allowed a clean separation of the complex from the excess inhibitor, and the purification of the former, as shown by

Figure 6.

ISD MALDI-TOF MS analysis of ATSI. The ISD fragmentation ladder spectrum of purified ATSI (after HPLC-C8 polishing) was performed on the reduced and S-carbamidomethylated ATSI using 2,5-DHB as a MALDI matrix. See details at Methods.

Figure 6.

ISD MALDI-TOF MS analysis of ATSI. The ISD fragmentation ladder spectrum of purified ATSI (after HPLC-C8 polishing) was performed on the reduced and S-carbamidomethylated ATSI using 2,5-DHB as a MALDI matrix. See details at Methods.

SDS-PAGE (see Fig.7) and RP-HPLC. Noteworthy that, in spite of elution in a very symmetric gel filtration peak, the sample from the complex displayed in such electrophoresis two additional bands of intermediate masses between the ones from trypsin and ATSI, reminding the formation of autolytic large and limited trypsin fragments, previously well reported for trypsin [

16,

17]. This could indicate that the overall stoke radius of the complex is not affected by such cleavages, if any, and that the conformation and main structure-function determinants of trypsin, hold by disulfides, are not grossly affected. Besides, such prepared complex readily crystallised, allowing the clean resolution of its three-dimensional structure (see below). Noteworthy, the potentially remaining trypsin activity of the complex was found null, and the X-ray electron density maps did not reflect any evidence of cuts/discontinuities at the protein inhibitor main chain (see at next section). This probably reflects that trypsin (isolated or in complex) mainly autolysed when mixed with the SDS buffer of PAGE, but it was intact within the analysed complex.

Figure 7.

Size exclusion chromatography of the ATSI-bTrypsin complex on a HiLoad Superdex75 269 column, and SDS-PAGE analysis of complex formation and purification. A). Separation of the 270 (first) peak of the complex from the (second) peak of excess ATSI was achieved in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 271 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0, at room temperature. B) SDS-PAGE analysis at 15% acryla-272 mide. Lanes 1 and 2: bovine trypsin and ATSI after 30 min incubation (alone) in activity buffer. 273 Lane 3: bovine trypsin–ATSI complex after 30 min incubation in a 1:2 molar mixture of them, in 274 activity buffer, and purification through Superdex75. Lane 4: ATSI in excess recovered by Superdex75. C) Analysis of the complex from crystals, before X-ray diffraction analysis.

Figure 7.

Size exclusion chromatography of the ATSI-bTrypsin complex on a HiLoad Superdex75 269 column, and SDS-PAGE analysis of complex formation and purification. A). Separation of the 270 (first) peak of the complex from the (second) peak of excess ATSI was achieved in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 271 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0, at room temperature. B) SDS-PAGE analysis at 15% acryla-272 mide. Lanes 1 and 2: bovine trypsin and ATSI after 30 min incubation (alone) in activity buffer. 273 Lane 3: bovine trypsin–ATSI complex after 30 min incubation in a 1:2 molar mixture of them, in 274 activity buffer, and purification through Superdex75. Lane 4: ATSI in excess recovered by Superdex75. C) Analysis of the complex from crystals, before X-ray diffraction analysis.

2.5. Three-dimensional crystal structure analysis of the ATSI-bTrypsin complex.

In order to facilitate crystallization, the purified ATSI-bTrypsin complex was concentrated to 16.0 mg/mL by centrifugal ultrafiltration and, at that time, the purification buffer was exchanged to 5 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0). Freshly prepared and concentrated complex was submitted to crystallisation assays, giving rise to well formed protein crystals. The three-dimensional structure of such crystallised complex, after analysis at the Alba Synchroton X-ray beam, was solved at 2.8 Å resolution. The quality of the electron density map allowed the perfect trace of side chains along the whole proteins and, particularly, regarding the enzyme subsites and the inhibitory, "reactive", site of ATSI.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional structure of ATSI in complex with bovine trypsin. Views of the complex structure shown in ribbons (left) and surface-charged representations (rigth). The latter depicts the penetration of the long binding/reactive loop of the inhibitor within the active site of the enzyme, including “reactive” Lys44, and the presence of a disulfide bridge between Cys4 and Cys49.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional structure of ATSI in complex with bovine trypsin. Views of the complex structure shown in ribbons (left) and surface-charged representations (rigth). The latter depicts the penetration of the long binding/reactive loop of the inhibitor within the active site of the enzyme, including “reactive” Lys44, and the presence of a disulfide bridge between Cys4 and Cys49.

The asymmetric unit of the crystal contained 8 complexes of ATSI-trypsin, basically all sharing a similar three-dimensional structure (Fig.8). The structure of bovine trypsin in complex with ATSI aligns well with other trypsin structures deposited in the PDB database. Despite the small size of ATSI, its crystal structure contains some secondary structure elements, namely a two stranded parallel ß-sheets and a small α-helix, which are able to form a hydrophobic core and to stabilize its fold. The active part of the molecules corresponds to the loop connecting the two b-strands, which is called “binding loop”, because it contains all the elements necessary to interact and inhibit serine proteases, either chymotrypsin, subtilisin or in this instance trypsin. ATSI from Amaranth also contains one disulfide bridge (Cys4-Cys49), which helps to stabilize the overall structure and in particular to maintain the conformation of the binding loop in the right orientation for inhibition.

A structural Blast analysis submitted towards the whole PDB data indicated that the three highest structural protein homologues of amarantath ATSI in the data bank are: 1) rBTI from buckwheat (PDB code 3RDZ, with a rmsd of 0.69 Å for 67 aligned residues); 2) LUTI, the Linum usitatissimum trypsin inhibitor (PDB code 1dwm, with an rmsd of 1.06 Å for 67 aligned residues); and 3) BGIT, a trypsin inhibitor from bitter gourd (PDB code 1vbw, with a rmsd of 0.66 Å for 66 aligned residues) (Fig.9).

Figure 9.

Aligned sequences and overlapped conformations of ATSI with homologous inhibitors of serine proteases of known three-dimensional structures (about 41.5% minimal sequence identity). 1) sp|P80211|, ATSI from Amaranthus caudatus; 2) tr|Q9S9F3|, rBTI from Buckwheat; 3) sp|P82381|, LUTI from Linum usitatissimum (Flax) (Linum humile); and 4) tr|Q7M1Q1|, BGIT from Momordica charantia (Bitter gourd) (Balsam pear). h, refers to residues in α-helix ; s, refers to residues in ß-strand. The + sign refers to the reactive/active site (cleavable site) of the inhibitor. The disulfide bridge connection is shown in stick representation.

Figure 9.

Aligned sequences and overlapped conformations of ATSI with homologous inhibitors of serine proteases of known three-dimensional structures (about 41.5% minimal sequence identity). 1) sp|P80211|, ATSI from Amaranthus caudatus; 2) tr|Q9S9F3|, rBTI from Buckwheat; 3) sp|P82381|, LUTI from Linum usitatissimum (Flax) (Linum humile); and 4) tr|Q7M1Q1|, BGIT from Momordica charantia (Bitter gourd) (Balsam pear). h, refers to residues in α-helix ; s, refers to residues in ß-strand. The + sign refers to the reactive/active site (cleavable site) of the inhibitor. The disulfide bridge connection is shown in stick representation.

The low rmsd value in these instances evidences that such proteins share a similar structural fold and are members of the potato inhibitor I family of serine protease inhibitors. In fact, such clear homology in sequences and crystal structures was de basis of the resolution we achieved of the electronic diffraction map of both molecules in the ATSI-bTrypsin complex by the molecular replacement approach. As shown in Fig.9, ATSI nicely aligns with all such trypsin inhibitors at the level of primary, secondary and tertiary structures. Noteworthy is also close conformational overlap of the long inhibitory/reactive site loop of ATSI and those of the other three inhibitors, of very similar size (around 8 residues) and conformation, protruding towards the active site of the receptor enzyme, as displayed in Figs.8 and 9.

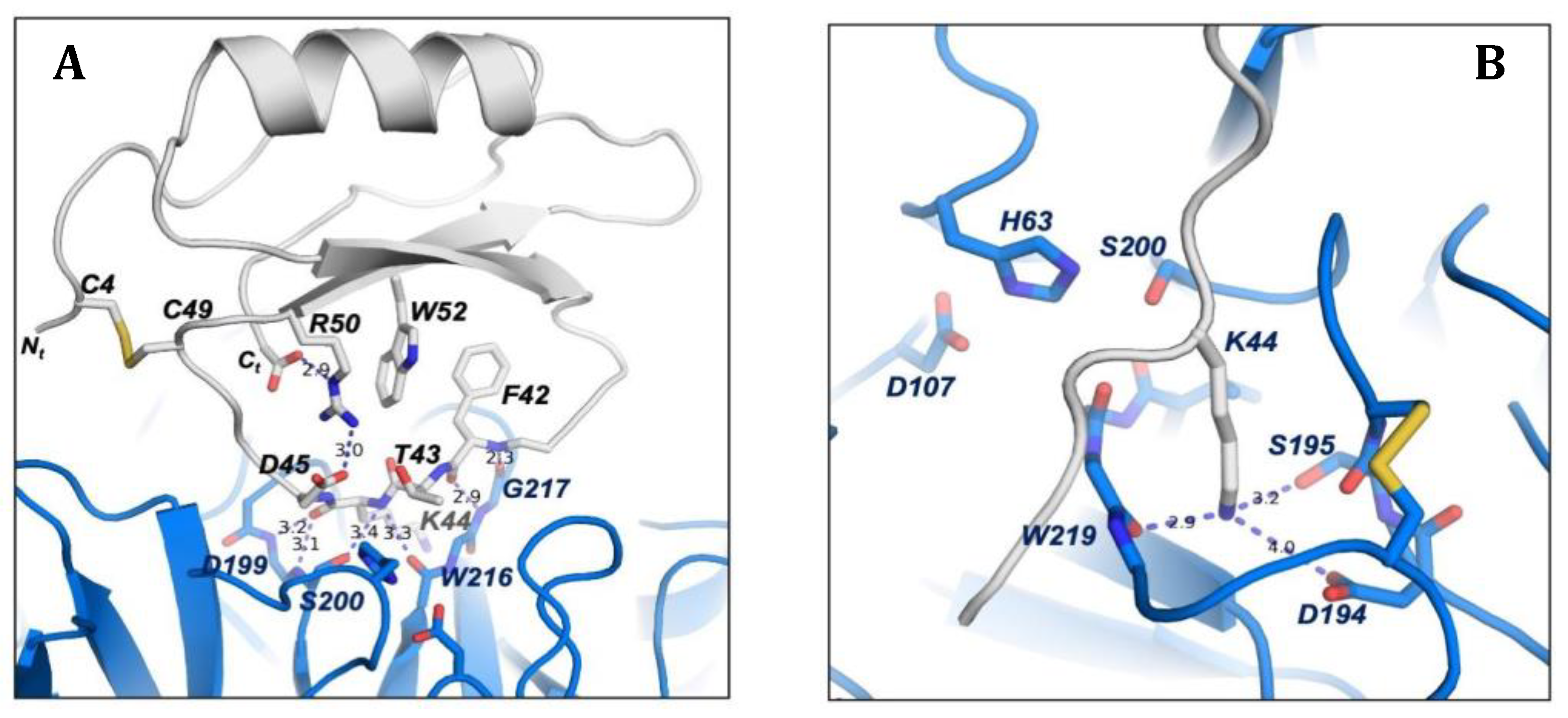

2.6. Structure-function details of the of the ATSI-trypsin complex.

To maintain the correct conformation of the binding loop of ATSI for the substrate-like inhibition on trypsin, several contacts are formed inside ATSI between residues of the ß2 strand and the binding loop. It is noticeable the role of Arg50 of ATSI, which is sandwiched between a hydrophobic interaction to Trp52 and an electrostatic interaction to the C-terminal carboxylate end of ATSI (2.9 Å). Arg50 also forms a salt bridge with Asp45 from the binding loop (3.0 Å), which in addition to the hydrophobic interaction with Phe42 helps to maintain the correct conformation of the binding loop for the right orientation of the substrate-like Lys44 to fit into the binding pocket of trypsin (Fig.10a). All those interactions described in ATSI from amaranth are conserved in other homologues of the family, such as Lute or orbit [

18], which complex three-dimensional structures are known. In other members of the family some substitutions in this region can be observed, but in all cases the fixed conformation of the binding loop, which is essential for the inhibition, is kept.

The low binding inhibitory constant of ATSI for bovine trypsin, indicative of tight binding, can be basically attributed to two major factors. First, to the perfect fitting of the substrate-like Lys44, which potentially constitutes the "reactive" cleavage site, into the negatively charged binding pocket of bovine trypsin. And second, to the hydrogen bond network formed between the main chain residues of the ATSI binding loop and the active site surface of trypsin. The negatively-charged binding pocket of bovine trypsin is formed by the side chains of Asp194 and Ser195, and by the carboxylate oxygen of Trp216. Essentially, the substrate-like side chain of the ATSI Lys44 is buried in the trypsin substrate pocket with its positive-charged ε-amino group positioned at hydrogen bond distance to the carboxylate oxygen of Trp216 (2.9 Å), to the side chain of Ser195 (3.2 Å), and to the negatively-charged Asp194 (4.0 Å), conducting a strong buried electrostatic interaction (Fig.10b).

Figure 10.

Detailed view of the three-dimensional structure fundamental elements of ATSI-trypsin complex. A) Detailed representation of the contacts in ATSI to shape the “reactive” loop in a correct orientation for binding to trypsin. Side chains are labelled and shown in stick representation. The residues essential for the mutual recognition of the inhibitor and enzyme and for the establishment of the transition state are shown. B) Binding of the “reactive” Lys44 of ATSI (in grey) inside the trypsin specific pocket. Numbered dotted lines indicate important polar interactions and bond distances.

Figure 10.

Detailed view of the three-dimensional structure fundamental elements of ATSI-trypsin complex. A) Detailed representation of the contacts in ATSI to shape the “reactive” loop in a correct orientation for binding to trypsin. Side chains are labelled and shown in stick representation. The residues essential for the mutual recognition of the inhibitor and enzyme and for the establishment of the transition state are shown. B) Binding of the “reactive” Lys44 of ATSI (in grey) inside the trypsin specific pocket. Numbered dotted lines indicate important polar interactions and bond distances.

However, the reason for the non-productive enzymatic binding of ATSI, that makes difficult its cleavage by bTrypsin, as well as external cleavages promoted by this enzyme, can be definitively attributed to the extensive network of hydrogen bonds between the ATSI binding loop with the active site region of trypsin, which traps ATSI in a substrate-like transition state of the reaction (Fig.10 A). In particular, these interactions are conducted by: the carboxylate oxygen and amino main chain of Phe42 with the respective amino and carboxylate oxygen of Gly217 (2.4 Å and 2.9 Å, respectively); the carboxylate oxygen and amino main chain of Lys44 with the amino of Ser200 (3.2 Å) and carboxylate oxygen of Ser215 (3.3 Å); the carboxylate oxygen of Lys44 with amino group of Gly198 (2.7 Å); and the amino group of Phe46 with the carboxylate oxygen of Phe47 (3.1 Å). Also, at the edges of the ATSI binding loop other hydrogen bonds are conducted between main chain Glu38, Arg39 and Cys48 with the side chains of Ser218 (2.9 Å), Lys125 (2.8 Å) and Tyr45 (3.4 Å), respectively. All this extensive network of hydrogen bond interactions inhibits the catalytic reaction by trapping ATSI as a non-productive substrate-like inhibitor.

2.7. Assaying the capabilities of ATSI to act as antimicrobial in cell cultures.

To go further into the functional properties of ATSI, we analysed those that could be related to the defence of the plant against microbial attacks, as generically suggested frequently as well as specifically for plant protease inhibitors [

3,

5,

19,

20], and to potential biotech/biomed applications. Thus, the growth of a series of bacterial cell cultures from well-known plant pathogens, like

Erwinia amylovora (Ea),

Xanthomonas arboricola PV. pruni (Xap) and

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pto), were analysed at different concentrations of ATSI, up to 100 microM final concentration of the inhibitor, following the drop plate assay on agar approach [

21], at 28ºC and pH 7.4, as shown in Fig.S5. In parallel, as a reference, the same assay was made with the antibacterial peptides BP100 and BP178, two well-known synthetic antimicrobial reference peptides for such species [

22]. No inhibitory effect on the growth of such bacterial cultures was observed along the tested ATSI concentrations, whilst in such conditions the reference peptides strongly affected the bacterial growth.

The assays were also expanded to three plant pathogenic fungi know to be important vegetal pests,

Fusarium oxysporum,

Penicillium expansum and

Botrytis cinerea, in similar concentrations of ATSI, at 23ºC and pH 7.4, and using a distinct reference antifungal peptide, BP15 [

23], Here again no inhibitory effects of the ATSI on the growth of such fungi were observed whilst positive effects were evident for the antifungical reference compound, as shown in Fig.S6. Also, to confirm this, the assay was repeated in the presence of 200 microM ATSI against

Fusarium oxysporum, caring this time in the avoidance of frozing/defrozing steps of the stored samples that could damage ATSI

, but again we got a negative result.

Also, assays were made using

Mycoplasma genitalium as a model microorganism, very far evolutively and functionally unrelated to the previous microbial models. Mycoplasmas are minimal cells, with very limited biosynthetic pathways, and with the presence of very promiscuous membrane transporters that make them quite permeable to external polar and non-polar molecules [

24,

25]. In addition,

M. genitalium is an emerging human pathogen, with an increasing interest to develop non-antibiotic therapies against this microorganism. When ATSI was included in

M. genitalium cultures in the range of 5-100 µM, it was noticeable a small increase of the duplication time of this microorganism, and cells reached the stationary phase of growth 15 hours later than cells without ATSI (Fig S7A). However, cell densities in the stationary phase were nearly identical both in the presence and in the absence of ATSI, concluding that this small polypeptide does not significantly inhibit the growth of mycoplasmas (Fig S7B). In contrast, when

M. genitalium cells were incubated with a small amount of a protein extract from the marine invertebrate

Nerita peloronta, very rich in protease inhibitors [

10], a strong inhibitory activity on the mycoplasma growth was observed (Fig S7A and B).

Additionally, and to get a more complete view

, antimicrobial assays were made with ATSI on the microbial parasite

Plasmodium falciparum, a protozoan of high biomedical impact, to expand our view on the properties and potentialities of the inhibitor. Initial results were negative, with a non-significative reduction of the growth of this microbe observed in the presence of a wide range of assayed concentration of this trypsin inhibitor, from 0-222 microM (

Table S4 and Fig.S8), using chloroquine as a reference anti-

Plasmodium compound. Noteworthy that at the higher assayed concentration of 444 microM, haemolysis of the erythrocytes included in the cell culture took place, indicating a potentially damaging action of ATSI in mammalian cells to be taken into account.

3. Discussion

The interest in the developments on proteolytic enzymes (proteases) and their inhibitors remains strong due to their diverse biological functions and the necessity for the precise controls they perform across evolutionary scales, or they require in biotech/biomed interventions. This also applies to plant proteases and their inhibitors, both for their intrinsic properties and their proven or potential roles in biotechnological applications, such as plant protection against parasites and predators [

3,

4,

5,

26], and in human biomedical issues and applications, as in digestive dysfunctions [

6], cancer development [

27,

28] and anti-microbial strategies [

5,

29], among others. The great potency of such molecules makes advisable to evaluate carefully their properties, generically and as bioactive compounds, and the limits of use and applications. This is particularly valid for cereals, pseudocereals and Leguminosae, and its seeds, usually rich in protease inhibitors, mostly of proteinaceous nature.

Additionally, at the nutritional level, such developments on several seeds of such plants crosses interest with the advised and increasing use of them at the human diet, because of their high and equilibrated content in proteins and essential constituent amino acids; also, of other beneficial constituents and lack of gluten in pseudocereals and Leguminosae [

30]. Therefore, the consumption and cultivation of these plants is steadily increasing nowadays. However, given that warnings have been issued about the potential anti-nutritional properties of the abundant protease inhibitors found in plant seeds [

6,

31], an important question is to what extend such concern has to be extended to them.

Quite a number of publications, mainly since 1990's, reporting the occurrence of protease inhibitors in the pseudocereals

Chenopodium quinoa (quinoa) and

Amaranthus sp. (amaranth), as well as in Leguminosae, appeared in the literature [

32,

33,

34,

35]. This has been confirmed in our study through the analysis of seed extracts from three varieties commonly used in the Andean region, using our affinity/IF-MS proteomics approach. Thus, in such extracts it appeared several small protein forms around 3949 Da. for

Chenopodium quinoa (quinoa) and several around 6838 Da for

Lupinus mutabilis (lupine), as well as a single form of about 7890 Da. for

Amaranthus hybridus (sangorache). Also, the extract from the seeds of this amaranth showed the higher trypsin inhibitory capability among the three species, although the higher protein content was clearly assignable to the lupine samples. Such remarkable protein content has already been reported in lupine seeds, in which the presence of bitter alkaloids and antinutritional factors, as protease inhibitors, limits its consumption, requiring previous debittering and fermentation treatments [

36].

Given the clear signals and MALDI-MS homogeneity of the molecular species that appeared as responsible of the high inhibitory content (per gram of seeds) in

A. hybridus (sangorache), we decided to extend the analysis to

A. caudatus (kiwicha), a parent species of the same genus, because although both are of Andean origin, the first one is more used at level of consumption of leaves or for ornamental uses, whilst for the latter one the consumption as seeds and flour is more important. Along America,

A. hypochondriacus is mainly used and originated in Mexico,

A. cruentus in Guatemala and southeast Mexico, and

A. caudatus &

A. hybridus in Andean South America [

8,

37,

38]. The uses of these and other related varieties are also high and rising in other parts of the world [

8,

37]. Remarkably, our analysis of the seed extracts indicated again a high (equivalent) trypsin inhibitory content for

A. caudatus, as well as exactly the same molecular mass, molecular homogeneity and protein sequence of its inhibitor by affinity, IF-MS, and MS/MS, than in the previously analysed

A. hybridus species. Noteworthy is that our aim was to use certified seeds from a single country, produced in rather similar climatic and cultivar conditions, to facilitate comparisons, and this was followed for the four distinct seeds here investigated.

On the light of the above results, we focused our attention on two previous publications in the field, one of Valdes-Rodriguez et al. (1993) [

39] and one of Hejgaard et al (1994) [

11] on the initial characterization of trypsin inhibitors from amaranth seeds, the former from

A. hypochondriacus and the latter from

A. caudatus. Interestingly, in the first paper the seeds were defatted with chloroform/methanol (2:1) before aqueous extract, whilst in the second case were defatted with ethyl acetate, as well as processed with different aqueous extraction and purification procedures. In the present work, we used a "greener organic solvent" for defatting [

40], that is propanol-1, a nowadays tendency. These variables are mentioned here because they could give rise to an unwanted variability of the extraction and final heterogeneity/appearance of distinct protein inhibitors, as well as of isoforms, if any, requiring full characterization. It is noteworthy that we used trypsin as the major model for serine protease targets in the study, because it is the most selected one in the field, but keeping in mind that protein inhibitors usually have a rather wide range of specificities for target proteases of the same catalytic class (i.e. on chymotrypsin, elastase and/or subtilisin), although in certain cases they can be more restricted regarding the natural target enzyme.

Interestingly and related, in both previous works they found a major form of a trypsin inhibitor of about 69 residues of sequence, one from

A. hypochondriacus and the other one from

A. caudatus. Subsequently, for the first form, differences were found regarding the other form in positions 34 (Asp/Ser) and 59 (Tyr/Ser), as well as double positions, probable indication of isoforms, for the

A. hypochondriacus inhibitor, for residues 41 (Ser/Tyr) and 65 (Thr/Tyr) (see Fig.S1 about). In such work, Valdez-Rodriguez et al (1999) [

41] cloned and sequenced the cDNA of the trypsin inhibitor of

A. hypochondriacus, corrected the former sequence, and found that the region encoding the mature protein had the same 69 residues sequence that the one from Hejgaard et al (1994) [

11] in

A. caudatus. However, in such late work, Valdez-Rodriguez et al, focusing on the duality in position 41 (Ser/Tyr), concluded that the sequence differences between both publications and species could be due to the possible occurrence of two distinct gene copies for such protein inhibitor in the amaranth genome, because of the observation of distinct fragments when such cDNA was cleaved by restriction endonucleases, in a Southern blot analysis.

At this respect, our experimental HPLC, IF-MS, comparative molecular masses and long fragmentation ladder MS/MS analyses of the trypsin inhibitor fraction that we isolated from A. caudatus, indicated that a single/unique molecular form of the trypsin inhibitor, of 7889.1 Da. and 69 residues, was present in our seeds and extracts. Also, that such form was in mass, sequence and homogeneity identical to the form studied by us from A. hybridus in this work, found as a single one and characterised at these levels by the first time. For clarity, let us remind that these two species originated and are mainly cultivated in Andean countries, whilst the A, hypochondriacus one is centered in Mexico, Central and NorthAmerica. Overall, and by correspondence and analogy of our results and the above described previous works, it can be suggested that a single form of such trypsin inhibitor, of 69 residues, is present and identical in A. hybridus and A. caudatus at the protein level, and is also present in A. hypochondriacus but with minor differences in sequence, and with the probable occurrence of a second isoform in the latter. The presence of second isoforms in A. hybridus and A. caudatus cannot be discarded given that the visualisation of isoforms, particularly for minor ones, could be dependent of the distinct defatting, extraction and purification procedures in different works, or even from the differential expression of genes (if double) in distinct growing, environmental conditions and cultivars.

The observed high homogeneity of the trypsin inhibitor from

A. caudatus seeds, with expected easy scalability, and its strong inhibitory potency versus the enzyme, with Ki in the low nanomolar level for trypsin, together with the large agricultural, biotechnological and nutritional interest of this plant species [

8,

41], prompted us to select it for further structure-function analyses. Given such selection, and to be respectful with the ATSI abbreviation initially suggested by Hejgaard et al (1994) [

11] for the inhibitor from the

A. caudatus species, we kept it along this work. In a next step, we envisaged detailed X-ray crystallisation studies of it in complex with trypsin. This was achieved with the known model bovine trypsin, when mixed with 2:1 (mol:mol) excess of inhibitor, following by incubation at 25ºC. The formed complex, isolated and purified by gel filtration chromatography, gave rise to well formed crystals and excellent X-ray electron density maps, allowing to trace the full complex structure without discontinuities. Hence, the unexpected mid-size faint bands that appeared in the electrophoretic analysis of the complex, probably due to trypsin autolytic action in the SDS-PAGE loading buffer, were not taken in consideration, as already mentioned at the end of subsection 2.4. of Results.

The excellent X-ray derived electron density maps at 2.8 Å resolution (see

Table S3 for X-ray data collection), allowed a clean delineation of the main and side chains of both the bovine trypsin and ATSI, including the active site of the former and binding site of the latter. Remarkably, the long loop containing the binding site of the inhibitor, that extends from residues Arg40 to Arg48, appeared here intact, in spite that in other similar trypsin inhibitor/trypsin complexes [

43], and in certain conditions, it becomes cleaved, action which facilitated its naming as "reactive loop". Remarkably, the crystal structure of the complex indicates that enzyme and inhibitor are in a substrate-like transition state mode, essential to understand the molecular mechanism of the binding, as well as for potential engineering purposes. Also it is significant the occurrence of the single disulfide bond of ATSI, Cys4-Cys49, in a position that constrains the binding loop by its center, helping to define its docking into the binding sites of the enzyme and probably contributing to the highly efficient inhibition of bovine trypsin, with a low Ki value. Besides, the here derived structure facilitates the classification of ATSI as a member of the structural-functional family of potato-I plant inhibitors, joining other ones from plants assigned to this family, as is the case of rBTI from Buckwheat, LUTI from

Linum usitatissimum (Linum humile) and BGIT from

Momordica charantia (Bitter gourd), to which it aligns very well, as shown in Fig.9. The availability of the detailed three-dimensional structure of ATSI could facilitate future protein engineering studies: i.e. by adding disulfides to it in order to strongly increase its stability. Such mutations probably would improve its endurance and capability to act as inhibitor on pest enzymes in

in vivo transgenic plants, an application already reported for other protease inhibitors [

26].

Previous evidences indicated that ATSI from

A. caudatus is a good enzyme inhibitor for certain mammalian serineproteases, as trypsin and chymotrypsin, as well as for bacillus subtilisins and a

Fusarium proteinase, suggesting that it might act as anti-microbial against them for the defence system of amaranth [

11]. On the other hand, when growth inhibitory assays with ATSI from

A. hypochondriacus were made on digestive proteinases in crude larvae extracts of the

P. truncatus insect [

39]

, not a usual predator of this amaranth species but known to have trypsin-like enzymes, positive results were observed. However, when such assays were extended to larvae extracts from other common insect grain pests, as

Sitophilus zeamais,

Tribolium castaneum,

Callosobruchus maculatus,

Zabrotes subfasciatus, and

Acanthoscelides obtectus, they didn't show inhibition action by ATSI [

39]. Also, assays from the same authors on crude fungal extracts from

Aspergillius niger and

Aspergillius fumigatus were negative regarding in vitro inhibition assays with ATSI. Later on the same laboratory found low levels of this inhibitor in

Amaranthus hypochondriacus young sprouts, probably assignable to plant defence mechanisms but not as wound inducible, concluding that the involvement of it in defense against bacteria and insects is still its most probable role [

41]. Also, other reports claimed the anti-microbial capability of organic and/or aqueous extracts of the shoots/sprouts, steams, leaves and seeds from different amaranth varieties, as

A. lividus and

A. hybridus [

38,

44], or as

A. caudatus [

38,

46,

47], including a diversity of bacteria and fungi. Overall, evidences on the involvement of ATSI in plant defence have been controversial.

Given that by now the roles of ATSI in amaranth plants still are not well clarified, particularly as antimicrobials, as well as regarding its potential biotech related properties, we assayed its purified form against distinct classes of microbes, in culture, selecting several of them considered as models bacterial plant pathogens: i.e. against the bacteria

Erwinia amylovora (Ea),

Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni (Xap) and

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pto), as well as against the plant pathogenic fungi

Fusarium oxysporum,

Penicillium expansumi and

Botrytis cinerea. In this work, in spite of using a range of assays reaching rather high concentrations of ATSI (i.e. until 100-200 microM), no significant inhibitory effect of ATSI on the growth of those bacterial and fungal microorganisms were detected in any of them, in contrast with the clear inhibitory effect when using reference model peptides (antibacterial and antifungal) of proved action on such microorganisms [

21,

22,

23]. Negative results were also observed by us when the assays were extended to a minimal, wall-less, bacteria, with poor protection against the action of harmful external molecules, as is the

Mycoplasma g., used as a model. In spite of these results, it should not be overlooked that the occurrence of diverse important microbial pests in amaranthus, among bacteria, fungi and mycoplasms, or the related phytoplasms, has been reported [

34,

45], a fact that would justify the involvement of defensive molecules against it in these plants. Unfortunately, such involvement and activity has not been backed in the present work.

Our final assay conducted to explore the potential anti-microbial effect of ATSI on the protozoan

Plasmodium falciparum, -the main causative agent of malaria-, yielded unexpectedly negative results, despite related biotech/biomed precedents and prospects about on protease inhibitors. Previous research had suggested that peptide or proteinaceous inhibitors of serine proteases might inhibit the growth and viability of human Plasmodium parasites [

48,

49,

50]. However, our findings indicate that ATSI does not meet this expectation. This result is particularly notable given ATSI’s apparent haemolytic activity, which may limit its utility in therapeutic applications against this parasite. To this respect, when developing inhibitors to combat

P. falciparum, the goal is to target the parasite without harming the host's red blood cells. Effective inhibitors should disrupt the parasite's lifecycle or its ability to infect and multiply within red blood cells. However, if an inhibitor also damages red blood cells or causes haemolysis (the rupture of red blood cells), it could exacerbate the condition, leading to severe anaemia and other complications.

Certainly, the results here collected on the effects of ATSI over distinct microbial cell cultures cannot be generalised and considered as a firm prove of its lack of role as antimicrobial in amaranth cultivars given that the assays were not made against the specific microbes that actually infects amaranth plants in the fields, either bacteria, fungi or phytoplasms [

34,

51,

52]. The lack of well established cell cultures for the microbes naturally infecting amaranth makes quite difficult such assays by now, but it will be worth to be performed on such microbes when feasible. However, overall, the here collected evidences seem to disfavour a role of ATSI, and its potential use, as antimicrobial and suggests to redirect its functional and applicative research towards defensive insect deterrence roles and/or other protective/regulatory functions in the amaranth seeds.