3. NLP Algorithms: Comparative Analysis

Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms are fundamental tools that enable computers to understand, process, and generate human language. These algorithms serve as the backbone for a wide array of applications, such as speech recognition, machine translation, sentiment analysis, chatbots, and information retrieval. NLP algorithms are designed to perform various language-related tasks, including tokenization, lemmatization, part-of-speech tagging, named entity recognition (NER), and text summarization. Over the years, advancements in machine learning and deep learning techniques, especially with the rise of transformer-based models like BERT, GPT, and RoBERTa, have significantly enhanced the ability of machines to comprehend the complexities of human language. These models not only interpret syntax but also understand context, disambiguating meanings and recognizing relationships within text. The growing sophistication of NLP algorithms has made them indispensable in fields like healthcare, finance, legal analysis, and knowledge management [8].

However, with the wide variety of NLP algorithms available, selecting the most suitable one for a specific task can be challenging. To address this, we will conduct a comparative analysis of various NLP algorithms based on three key criteria: accuracy, speed, and resource requirements. Accuracy will be measured by the algorithm’s ability to produce correct and meaningful results; speed will evaluate how quickly the algorithm performs, especially in real-time or large-scale applications; and resource requirements will consider the computational resources, such as memory and processing power, needed to run the algorithm efficiently. This focused analysis will provide insights into the best-suited algorithms for different stages of NLP tasks, ensuring optimal performance and scalability in real-world applications.

- ⮚

Text cleaning

Text cleaning is a crucial step in data preprocessing, especially in fields like Natural Language Processing (NLP), where unstructured text is processed to extract meaningful information. The following table provides a comparative analysis of NLP algorithms for this task based on various criteria such as accuracy, resource requierement and speed.

Regular expressions, or regex, are character sequences that define patterns for searching and manipulating text. They play a crucial role in natural language processing (NLP) tasks such as text searching, data extraction, and format validation. Regex enables users to specify intricate string-matching rules, making them invaluable for organizing, cleaning, and efficiently parsing textual data [9].

Spelling correction is the process of identifying and rectifying errors in text to enhance its accuracy. In natural language processing (NLP), this involves techniques such as edit distance algorithms, like Levenshtein Distance, which calculate the number of edits required to transform one word into another. Contextual models, including transformer-based tools, analyze surrounding text to predict the most likely intended word. Additionally, dictionaries or lexicons are used to validate words and suggest accurate alternatives, ensuring the text adheres to standard spelling conventions [10].

Noise removal in NLP involves filtering out irrelevant or unhelpful elements from text to retain only meaningful information for tasks like analysis or modeling. Typical forms of noise include special characters that often lack semantic significance, stop words such as “the” or “is,” which carry minimal contextual value, and numerical values that might be unnecessary in certain applications [11].

Table 1.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for text cleaning.

Table 1.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for text cleaning.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requirement |

| Regular Expressions |

Moderate |

fast |

Low |

| Spelling Correction |

High for common spelling errors |

Moderate |

Moderate |

| Noise Removal |

Low to Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

Comparative analysis: Regular expressions are fast and flexible but may require manual tuning and can be prone to errors for more complex text cleaning. Spelling correction works well but adds computational overhead. Noise removal methods (like lowercasing) are simple and effective, though they may miss important information.

- ⮚

Tokenization

Tokenization is a fundamental step in Natural Language Processing (NLP) that involves breaking down text into smaller units, called tokens. Tokens can be words, phrases, or even characters, depending on the specific application. This step is crucial for text analysis as it helps transform raw text into a structured format that algorithms can process.

Whitespace tokenization is a straightforward method in NLP where text is divided into tokens based on spaces, tabs, and newline characters. It operates under the assumption that words are primarily separated by spaces, which makes it suitable for simple tokenization tasks. However, this approach struggles with punctuation and special characters and may not work well when words are written without spaces, such as “NewYork,” where it would incorrectly treat the combined form as a single token. Consequently, while whitespace tokenization is efficient for basic use cases, it has limitations when handling more complex text structures [12].

The Treebank Tokenizer is a more advanced tokenization tool that employs predefined rules and models to accurately process text. It is particularly adept at managing punctuation, contractions, and other special cases, such as splitting “don’t” into “do” and “n’t.” Unlike simpler tokenization methods, it ensures consistency with syntactic structures, making it especially useful in syntactic parsing tasks. It is commonly employed with Treebank-style annotations, which include part-of-speech tagging and syntactic parsing, to maintain precise and coherent tokenization in natural language processing tasks [13].

Subword tokenization decomposes words into smaller, more meaningful units called subwords, which helps improve handling of rare or previously unseen words in tasks like machine translation and language modeling. Techniques such as Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), SentencePiece, and WordPiece break down words into subword components, allowing for better generalization across languages. For instance, the word “unhappiness” could be split into “un” and “happiness” or further into even smaller parts like “un,” “happi,” and “ness.” This method ensures more flexible handling of diverse vocabulary and improves model performance, especially in multilingual contexts [14].

Table 2.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for Tokenization.

Table 2.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for Tokenization.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| Whitespace Tokenzization |

Low |

Fast |

Low |

| Treebank Tokenizer |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

| Subword Tokenization |

High |

Moderate |

High |

Analysis: Whitespace tokenization is fast but lacks accuracy for more complex sentence structures. Treebank tokenization is more accurate but slower and less scalable. Subword tokenization, used in models like BERT, provides high accuracy but requires significant resources and is computationally expensive.

- ⮚

Normalization

Normalization is a preprocessing technique in NLP that converts text into a standard or canonical form. It is essential for ensuring consistency in the data and improving the performance of downstream tasks like text classification, sentiment analysis, or machine translation. By reducing variability in text, normalization makes it easier for algorithms to analyze and extract meaningful insights.

Text preprocessing techniques like lowercasing, stemming, and lemmatization are essential for normalizing text in natural language processing (NLP). Lowercasing standardizes words by converting all characters to lowercase, helping reduce case-related inconsistencies. Stemming reduces words to their root forms using algorithms like Porter or Snowball, although it can result in non-dictionary forms. In contrast, lemmatization is more precise, transforming words into their base form based on context and meaning (e.g., “better” to “good” and “running” to “run”), and is particularly useful for tasks requiring semantic accuracy. While stemming is computationally faster, lemmatization is preferred for tasks where context and correctness are critical [15].

Table 3.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for Normalization.

Table 3.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for Normalization.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| Lowercasing |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Stemming |

Low to Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Lemmatization |

High |

Slow |

Moderate |

Analysis: Lowercasing is a quick and simple process but can lead to loss of context. Stemming is fast and works well for many use cases but can lead to non-dictionary words. Lemmatization is more accurate as it returns valid words but is slower and requires additional resources.

- ⮚

Stopword Removal

Stopword removal is a preprocessing technique in NLP that involves eliminating common words that usually carry little semantic meaning. These words, called stopwords, include terms like “the,” “is,” “in,” “and,” or “of.” The goal is to reduce noise in the text, enabling algorithms to focus on more informative and meaningful words.

Predefined lists in NLP refer to sets of words used for specific tasks, such as stopwords or domain-specific vocabularies, which help streamline processes like tokenization and information extraction. TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) is a statistical method used to assess the importance of words within a document relative to a corpus, highlighting words that are frequent in specific documents but rare across others, making it useful for text mining, search engines, and information retrieval [16].

Table 4.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for stopword removal.

Table 4.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for stopword removal.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| Predefind Lists |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| TF-IDF |

High |

Moderate |

High |

Analysis: Predefined lists are very fast but may miss important stopwords in context. TF-IDF is more context-sensitive but computationally more expensive.

- ⮚

Named Entity Recognition (NER)

Rule-based models in NLP rely on predefined linguistic rules to process language, often used for tasks like parsing and named entity recognition. While they can be highly accurate in structured settings, they lack flexibility and struggle with ambiguity. Statistical models, such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Naive Bayes, use probabilistic methods to infer relationships within data, offering more adaptability in tasks like part-of-speech tagging and machine translation. Deep learning models, particularly transformer-based architectures like BERT and GPT, have significantly advanced NLP by automatically learning from vast datasets, excelling in tasks like text generation, summarization, and question answering with impressive accuracy [17].

Table 5.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for NER.

Table 5.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for NER.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierment |

| Rue-Based |

Low to Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Statistical Models |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

| Deep Learning |

High |

Slow |

High |

Analysis: Rule-based systems are fast and simple but limited by predefined rules. Statistical models like CRFs offer better accuracy but require labeled data. Deep learning models such as BERT deliver the highest accuracy but require significant computational resources and are slower.

- ⮚

Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) are probabilistic models that assume an underlying hidden state evolves over time, often used in sequential tasks like speech recognition or part-of-speech tagging. Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) are similar but focus on structured prediction, considering the entire input sequence when making predictions. Deep learning, particularly with models like RNNs, LSTMs, and transformers, surpasses HMMs and CRFs in capturing complex relationships in data, making it ideal for tasks that require understanding context and dependencies within large datasets, such as natural language processing [18].

Table 6.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging.

Table 6.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| HMM |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| CRF |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

| Deep Learning |

High |

Slow |

High |

Analysis: HMMs are fast and simple but may not capture long-range dependencies. CRFs offer better performance, especially in sequence prediction tasks. BiLSTM-CRF or transformer-based models provide the best accuracy but are resource-heavy and slow.

- ✓

Coreference Resolution

Rule-based models in NLP rely on predefined linguistic rules for tasks like parsing and named entity recognition, but they lack flexibility and struggle with ambiguity. Machine learning models, such as decision trees and SVMs, adapt to data and are more versatile than rule-based models, making them suitable for a wide range of tasks. Deep learning models, including RNNs, CNNs, and transformers, automatically learn complex patterns from large datasets, outperforming both rule-based and machine learning models in tasks like text generation, translation, and summarization due to their ability to capture context and dependencies [19].

Table 7.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for coreference resolution.

Table 7.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for coreference resolution.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| Rule-based |

Low to oderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Machine Learning |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

| Deep Learning |

Very High |

Slow |

High |

Analysis: Rule-based systems are fast and simple but not as effective for complex coreferences. Machine learning models (e.g., CRFs) perform well but require labeled data. BERT-based models offer very high accuracy at the cost of significant resources and time.

- ✓

Key Phrase Extraction

TF-IDF, RAKE, and TextRank are common algorithms in Natural Language Processing used for tasks like keyword extraction, summarization, and information retrieval. TF-IDF calculates the importance of words in a document by combining term frequency (TF) with inverse document frequency (IDF), highlighting terms that are significant within specific contexts. RAKE focuses on extracting multi-word key phrases by analyzing word co-occurrence patterns, making it efficient for large datasets. TextRank, inspired by the PageRank algorithm, builds a graph of words or phrases, using their relationships to rank their importance for tasks like summarization and keyword extraction. These techniques are fundamental in text analysis and content processing [20].

Table 8.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for key phrase extraction.

Table 8.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for key phrase extraction.

| Algotithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| TF-IDF |

Moderate |

fast |

Low |

| RAKE |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| TextRank |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Analysis: TF-IDF is quick and simple but may miss contextual relevance. RAKE is fast and can handle short texts but might miss key phrases in larger documents. TextRank performs well in terms of semantic relevance but is slower and more complex to implement.

- ✓

Sentiment Analysis

Lexicon-based approaches in NLP use predefined word lists or lexicons to perform tasks like sentiment analysis, relying on word matching to determine meaning. While simple and interpretable, they can struggle with context and ambiguity. Machine learning methods, on the other hand, learn from labeled data to make predictions and are more adaptable than lexicon-based models. Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, goes further by using neural networks with multiple layers to automatically learn complex language patterns, making it especially effective for handling tasks like text generation, translation, and sentiment analysis due to its ability to understand context and semantic nuances [21].

Table 9.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for sentiment analysis.

Table 9.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for sentiment analysis.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| Lexicon-Based |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Machine Learning |

High |

Moderate |

Low |

| Deep Learning |

Very High |

Slow |

High |

Analysis: Lexicon-based methods are fast but lack accuracy in complex sentiment scenarios. Machine learning models (e.g., Naive Bayes, SVM) are more accurate but require labeled data. Deep learning methods (e.g., LSTM or BERT) provide very high accuracy but demand significant computational power and time.

- ✓

Text Summarization

Extractive summarization involves selecting important sentences or phrases directly from the original text to create a concise summary, often using techniques like TF-IDF, TextRank, or supervised learning models. It is computationally less intensive but may lack coherence as it simply extracts fragments. In contrast, abstractive summarization generates summaries by paraphrasing and rephrasing the original content, often employing deep learning models such as sequence-to-sequence networks or transformers. While abstractive methods are more complex and resource-demanding, they provide more coherent and human-like summaries. Both approaches have distinct advantages, with extractive methods being simpler and faster, while abstractive methods produce more natural summaries [22].

Table 10.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for text summarization.

Table 10.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for text summarization.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierement |

| Extractive Summarization |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Abstractive Summarization |

High |

Slow |

High |

Analysis: Extractive summarization is simpler and faster but may lack coherence. Abstractive summarization provides better and more coherent results but is computationally expensive and slower.

- ✓

Semantic analysis

Word embedding models, such as Word2Vec, GloVe, and FastText, map words into dense vectors, capturing their semantic meaning, and are widely used for tasks like sentiment analysis and machine translation. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including LSTMs and GRUs, handle sequential data by maintaining memory of previous inputs, making them suitable for tasks like language modeling and speech recognition. GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), a powerful model for text generation, utilizes an autoregressive approach and pre-training on large datasets to produce highly coherent text. SBERT (Sentence-BERT) extends BERT by generating efficient sentence embeddings, which are particularly effective for semantic similarity and clustering tasks. These models represent key advancements in NLP, improving how machines understand, generate, and manipulate language [23].

Analysis: GPT and SBERT stand out in terms of accuracy, with GPT excelling in tasks requiring contextual understanding and SBERT demonstrating superior performance in semantic similarity tasks. When it comes to speed, word embedding models like Word2Vec are the fastest due to their simplicity and lightweight nature, while SBERT, optimized for embedding generation, offers faster inference compared to GPT. However, resource requirements vary significantly: word embeddings are highly lightweight and efficient, making them ideal for resource-constrained applications, whereas GPT, with its massive size and transformer-based architecture, demands substantial computational power for both training and inference.

Table 11.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for semantic analysis.

Table 11.

The performance of NLP Algorithms for semantic analysis.

| Algorithm. |

Accuracy |

Speed |

Resource Requierment |

| Word Embedding Models |

Moderate |

Fast |

Low |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) |

High |

Slow |

High |

| GPT |

Very high |

Slow |

High |

| SBERT |

High |

Fast |

Moderate |

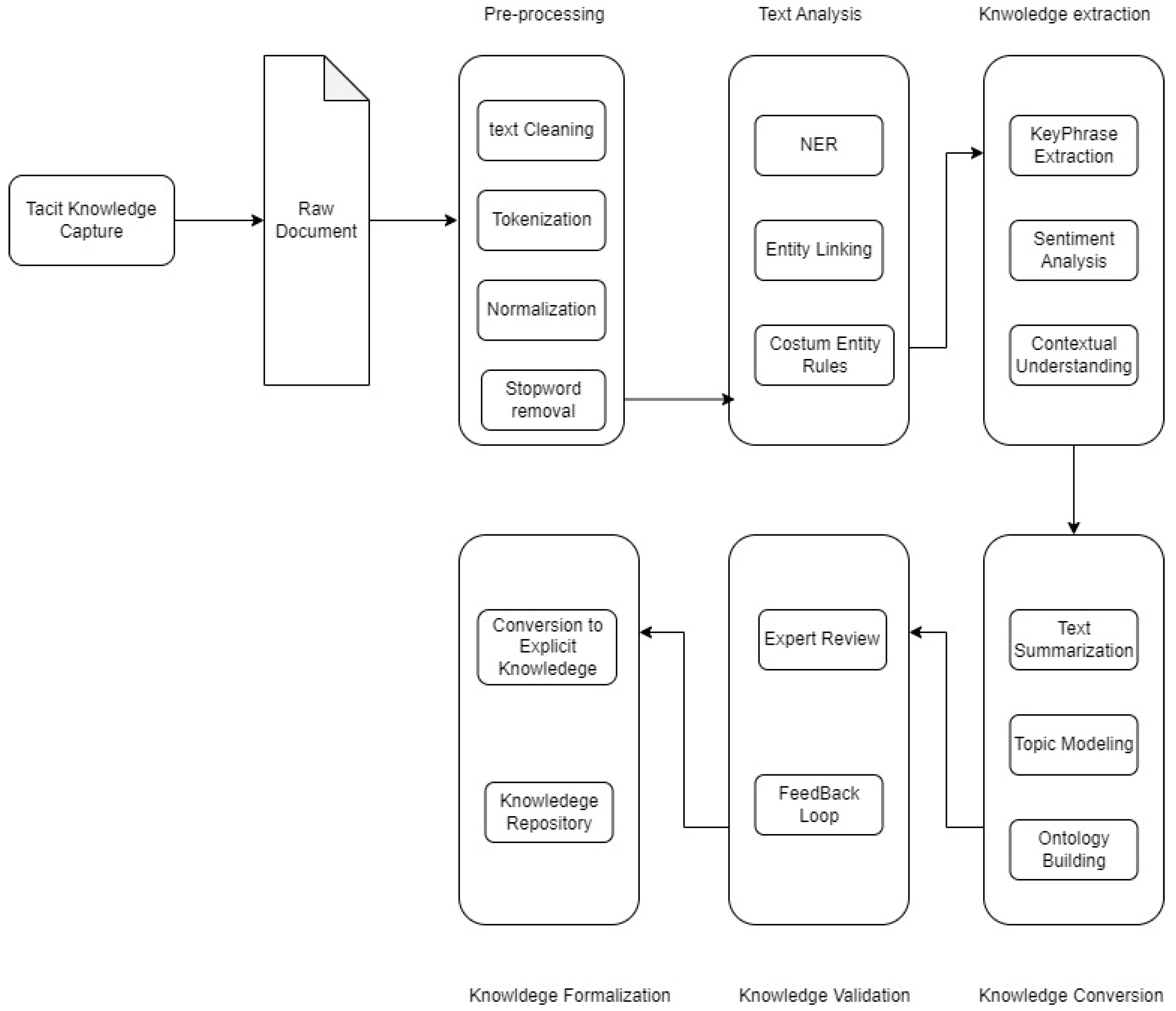

After conducting a comprehensive comparative analysis of various NLP algorithms, we propose utilizing the algorithms listed in the table for tacit knowledge conversion. These algorithms were selected based on their proven effectiveness, adaptability, and performance across a wide range of tasks, from text preprocessing to advanced understanding and summarization.

Table 12.

The proposed NLP algorithms for tacit knowledge conversion.

Table 12.

The proposed NLP algorithms for tacit knowledge conversion.

| Task |

The Proposed NLP Algorithm for tacit knwoledge conversion |

| Text Cleaning |

Regex-based Cleaning |

| Tokenization |

Hugging Face Tokenizers |

| Stopword Removal |

SpaCy Stopwords |

| Named Entity Recognition (NER) |

BERT-based NER |

| Entity Linking |

DBpedia Spotlight |

| Keyphrase Extraction |

KeyBERT |

| Sentiment Analysis |

Transformer-based Models |

| Clustering |

DBSCAN |

| Contextual Understanding |

Sentence-BERT |

| Text Summarization |

BART (Abstractive Summarization) |

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. SBERT for Tacit Knowledge Conversion

- ⮚

SBERT

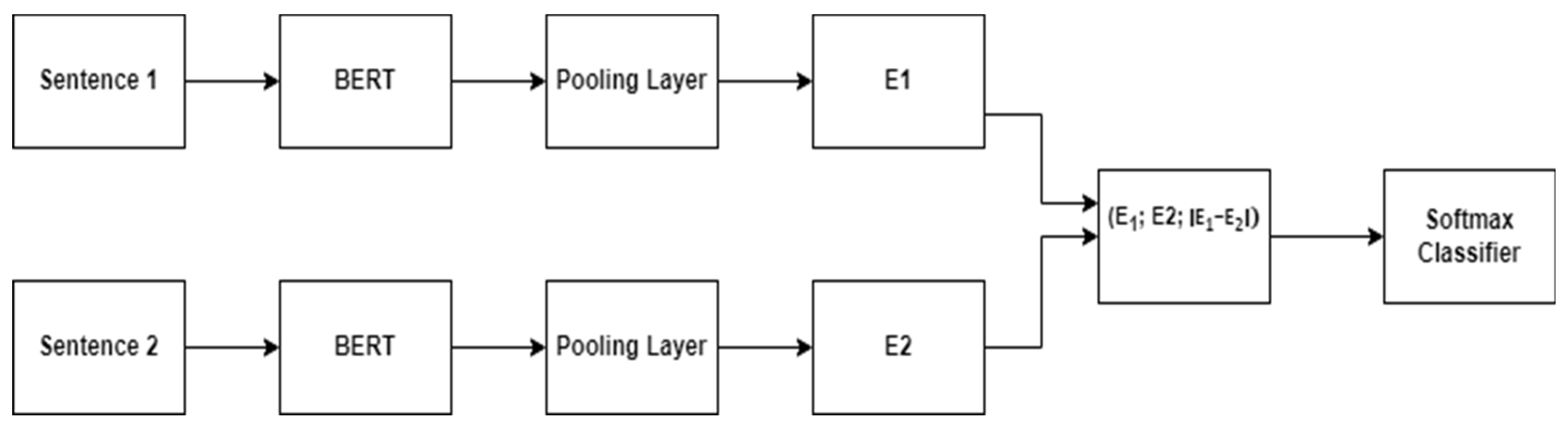

After conducting a thorough comparative analysis of various Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms and selecting the most suitable one for each specific task, we now focus on one of the most pivotal models in the field for tacit knowledge conversion: SBERT (Sentence-BERT). SBERT stands out for its ability to generate high-quality sentence embeddings that effectively capture the semantic meaning of text. This makes it an essential tool for tasks such as knowledge retrieval, information clustering, and, most importantly, the conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. In this section, we will provide an overview of SBERT’s architecture, highlighting its relevance in knowledge management systems especially in tacit knowledge conversion.NLP systems that handle large volumes of text require effective sentence embeddings, and one of the most advanced algorithms for this task is SBERT (Sentence-BERT). Using Siamese twin networks, SBERT minimizes the distance between embeddings of similar examples and maximizes it for dissimilar ones. This contrastive learning approach enables SBERT to capture both word order and semantics in text sequences. While earlier models focused on context-based word embeddings, SBERT combines both word-level and sentence-level understanding [24] It consistently outperforms previous models across a range of tasks, particularly when trained on larger datasets, showcasing improved scalability and performance.

SBERT has demonstrated remarkable success on benchmarks such as Semantic Textual Similarity and information retrieval tasks. Its ability to generate high-quality sentence or paragraph embeddings is crucial for Phase 1 of Nonaka’s SECI framework, which focuses on converting tacit knowledge. Unlike traditional BERT models, which require repetitive queries for each sentence, SBERT efficiently pairs a query sentence with multiple document sentences without recalculating the query embedding each time, making it scalable for real-time applications. By modifying BERT’s architecture to include pooling operations, SBERT creates sentence embeddings that preserve the semantic context of the entire sentence while remaining fast and scalable. As a result, SBERT is now regarded as one of the most effective methods for generating sentence embeddings in NLP tasks.

Figure 3.

SBERT architecture.

Figure 3.

SBERT architecture.

- ⮚

Input Representation:

Two sentences S1 and S2 are given as inputs.

Tokenize S1 and S2 using a shared tokenizer

- ⮚

Shared Encoding via BERT:

Pass S1 and S2 through identical pre-trained BERT models BERT

shared.

- ⮚

Pooling Layer:

Aggregate token embeddings into fixed-size sentence embeddings:

Common pooling strategies:

Use the [CLS] token embedding.

Compute the mean of all token embeddings.

Compute the max value across embeddings.

- ⮚

Similarity/Task Computation:

Compare the sentence embeddings E1 and E2 using a similarity metric or task-specific logic.

For similarity: Compute cosine similarity Sim (E1, E2).

For classification: Concatenate E

1 and E

2, and pass through a classifier:

- ⮚

Output:

Generate embeddings E1 and E2 that are:

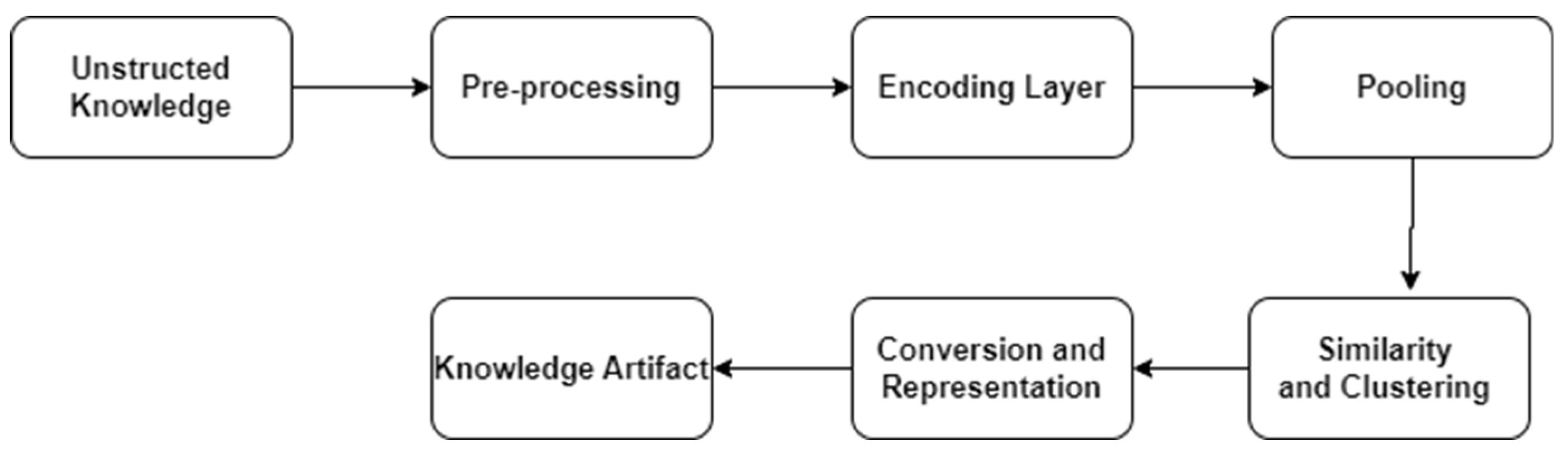

Tacit Knowledge Conversion involves transforming unstructured, implicit knowledge into structured, explicit forms that can be shared and utilized.

SBERT can be used to process and compare text data, cluster similar concepts, or identify implicit patterns from unstructured content like documents, discussions, or interview transcripts. Below is a conceptual SBERT-based architecture tailored for tacit knowledge conversion.

Figure 4.

The proposed SBERT Architecture for tacit knowledge conversion.

Figure 4.

The proposed SBERT Architecture for tacit knowledge conversion.

- ⮚

Input Layer (Unstructured Text Sources):

Unstructured text inputs can be collected from various sources, including employee feedback gathered through surveys, performance reviews, and suggestion boxes, as well as meeting transcripts derived from audio or video recordings, handwritten notes, or summaries. Additionally, research papers and case studies provide valuable text data, often sourced from academic databases or organizational archives. Informal communication, such as emails and chat logs, further contributes to unstructured text inputs, offering insights from casual interactions within teams or across organizations.

Let S

1, S2,…, Sn be the set of unstructured sentences, each representing an instance of tacit knowledge:

where:

Si is a sentence, expressed as a sequence of words or tokens (w1, w2,…, wm) for a sentence Si, and d represents the dimensionality of each token embedding.

- ⮚

Preprocessing Layer:

Tokenization and normalization involve preprocessing text data to enhance its usability for analysis. This includes removing noise, such as redundant phrases and formatting inconsistencies, to ensure cleaner inputs. Sentences can then be tokenized using advanced tools like SBERT’s tokenizer, which enables the extraction of key phrases or thematic sentences for more focused analysis.

The sentence S

i is tokenized into subword units w

1,w

2,…,w

m and mapped into embeddings using a tokenizer. This generates token embeddings:

where:

ej is the embedding of token wj, and k is the embedding dimension.

- ⮚

Encoding Layer (Shared SBERT Backbone):

Each sentence or segment is processed using a pre-trained SBERT model to generate dense sentence embeddings. These embeddings capture the semantic meaning of the text, enabling a more nuanced representation of the underlying information.

where:

tj ∈ Rk is the contextualized embedding of token wj.

- ⮚

Pooling

The sentence embedding ei is generated by applying a pooling function on the contextualized token embeddings t1, t2,…,tm. Pooling can be done in multiple ways:

ei is the final sentence embedding, which is the mean of all token embeddings.

- ⇗

Max Pooling:

ei is the element-wise maximum of the token embeddings. Clustering and Similarity Analysis (Knowledge Aggregation):

To find similarities between sentences S

i and S

j, we compute the cosine similarity between their sentence embeddings ei and ej:

where:

ei⋅ej is the dot product between the two sentence embeddings.

∥ei∥ and ∥ej∥ are the L2 norms (magnitudes) of the embeddings.

Once the sentence embeddings are computed, clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means) are used to group similar sentences together. The k-means algorithm involves the following steps:

C1, C2,…, Ck (initial centroid locations)

- ⇗

Assign each sentence to the nearest centroid

- ⇗

Update centroids based on assignments

Clusterj is the set of sentences assigned to centroid Cj.

- ⮚

Conversion and Representation:

Tacit knowledge is transformed into explicit forms, such as rules, guidelines, or models, through techniques like embedding-based clustering and summarization. Additionally, multiple sources of explicit knowledge can be combined to create higher-order concepts, with embeddings used to pinpoint redundancies and uncover synergies among the different knowledge sources.

- ⮚

Output Layer (Knowledge Artifacts):

Structured knowledge artifacts can be created in various forms, including concise summaries, organized taxonomies, and comprehensive knowledge graphs, to systematically represent and manage information.

This is a Pseudocode that demonstrates the process of clustering unstructured text data using Sentence-BERT (SBERT) embeddings and the KMeans clustering algorithm. Here’s a step-by-step explanation:

documents = [“Tacit knowledge is difficult to express.”,

“Effective teams often learn by doing.”,

“Collaboration fosters innovation.”]

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

model = SentenceTransformer (’paraphrase-MiniLM-L6-v2’)

embeddings = model.encode (documents)

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

Num_clusters = 2 # Adjust based on data

Clustering_model = KMeans (n_clusters=num_clusters)

clustering_model.fit (embeddings)

Cluster_labels = clustering_model.labels_

Clusters = {i: [] for i in range (num_clusters)}

For idx, label in enumerate (cluster_labels):

Clusters [label].append (documents [idx])

For cluster, sentences in clusters.items ():

Print (f”Cluster {cluster} :”)

For sentence in sentences:

Print (f” - {sentence}”)