1. Introduction

China’s rapid economic growth in recent years has been accompanied by an increasingly fast-paced lifestyle and high-pressure work environments, contributing to heightened mental stress [

1,

2]. This trend has emerged as a significant factor in the prevalence of mental health issues such as insomnia, depression, and cardiovascular disorders [

3]. Among the most affected demographic are young adults' aged 35–44, particularly those residing in large urban centers, where demanding professional and social conditions prevail [

4]. Addressing the mental health challenges faced by this group is a pressing concern within China’s broader agenda for sustainable social development.

Emerging evidence suggests that exposure to natural environments can serve as an effective, low-cost intervention for improving mental health outcomes [

5]. However, the intensification of urbanization has led to a steady decline in accessible natural spaces, positioning urban parks as critical environments for fostering connections with nature. Optimizing the role of urban parks in mitigating mental stress is, therefore, an urgent priority [

6].

Perceived restoration, also known as psychological recovery, involves the improvement of emotional, cognitive, and physical well-being through the alleviation of stress and fatigue [

7,

8]. This concept is frequently explored within the framework of Kaplan's Attention Restoration Theory, which emphasizes the restorative benefits of environments that reduce cognitive fatigue. The Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) is widely used to assess psychological recovery, alongside physiological measures such as changes in blood pressure, blood glucose, and skin conductance [

9,

10]. Self-reported evaluations of physical and mental recovery further complement these methods, offering a holistic view of perceived restoration [

6].

A growing body of research underscores the role of urban parks in promoting perceived restoration. For example, studies using virtual reality (VR) simulations have demonstrated that environments designed to support rest, relaxation, and social interaction significantly enhance psychological recovery [

11]. Specific sensory inputs, such as the sounds of birdsong, and seasonal landscape features, such as winter scenes along park pathways, have been identified as particularly effective [

12,

13]. Urban parks can be broadly categorized into four dimensions: natural elements (e.g., vegetation and water bodies), perceptual elements (e.g., quietness and spatial seclusion), rest elements (e.g., comfortable seating and relaxation areas), and activity elements (e.g., fitness and recreational facilities) [

1,

2,

14].

In addition to supporting perceived restoration, urban parks often foster emotional bonds between visitors and their environments, a phenomenon known as place attachment [

15]. This concept encompasses two key dimensions: place dependence and place identity[

19,

20]. Place dependence refers to the functional reliance on a location to meet specific needs, such as recreational or infrastructural activities, while place identity reflects an emotional connection and a sense of alignment with a place's values and significance [

16,

17,

18]. Place attachment not only shapes visitors' emotional experiences and behavioral loyalty but also influences their intention to revisit parks, thereby establishing a dynamic link between parks and their users [

19].

Given these considerations, an important question arises: does place attachment mediate the relationship between urban parks and perceived restoration among young adults'? While prior research has highlighted the restorative effects of urban parks, limited studies have examined the intermediary role of place attachment in this context. Exploring the interplay between urban parks, place attachment, and perceived restoration can provide valuable insights into the design and management of parks to better support the well-being of younger populations.

Research Questions:

Q1: Do urban parks influence young adults' perceived restoration?

Q2: Does place attachment mediate the relationship between urban parks and young adults' perceived restoration?

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Urban Parks and the Perceived Restoration of Young Adults'

Extensive research has established that urban parks play a significant role in enhancing visitors' perceived restoration through their unique environmental features [

20,

21]. For instance, the soundscapes of urban parks, encompassing natural sounds such as birdsong, flowing water, and rustling leaves, are known to promote psychological recovery and relaxation [

22,

23,

24]. Other studies have highlighted the importance of ecological attributes such as tree diversity, expansive green coverage, and the presence of flowers and lawns, which collectively contribute to improved health perceptions and overall well-being [

9,

25].

Evidence also suggests that specific park elements elicit varied emotional responses [

26,

27,

28]. For example, research focusing on college students found that environments featuring plants and water foster positive emotions, while those dominated by paved brick surfaces are more likely to evoke negative reactions [

29,

30]. However, while the perceived restoration of urban parks have been widely studied in general populations, there remains a notable gap in research specifically addressing young adults' [

31,

32]. This demographic is often exposed to heightened levels of mental stress due to societal pressures and urban living conditions, making them a critical focus for restorative interventions [

33].

Addressing this gap is essential to developing urban design strategies that can alleviate psychological stress more effectively in young adults'. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Urban parks have a significant positive impact on the perceived restoration of young adults'.

2.2. Place Attachment, Urban Parks, and Young Adults’ Perceived Restoration

The relationship between urban parks and place attachment has been extensively documented [

34,

35]. Studies have demonstrated that various park features, such as pedestrian accessibility, connectivity with surrounding environments, and satisfaction with amenities like playgrounds, positively influence place attachment [

36]. In multicultural contexts, research has shown that bicultural immigrants develop place attachment to urban parks through elements such as gardens, opportunities for social interaction, and visual appeal [

37]. Additionally, biodiversity within parks has been identified as a contributing factor to place attachment, mediated by spatial design, aesthetic qualities, and plant variety [

23].

Place attachment is also closely linked to perceived restoration [

38,

39]. For example, studies in historical districts have revealed that tourists' emotional connections to a place, shaped by its landscape and cultural elements, directly enhance their restorative experiences [

40]. Familiar environments that evoke relaxation and happiness are particularly effective in fostering perceived restoration [

41,

42]. Furthermore, frequent park visits and the ability to access parks on foot are strongly associated with higher levels of place attachment, emphasizing the role of emotional and behavioral engagement in shaping restorative outcomes [

43,

44].

These findings suggest that perceived restoration in urban parks is influenced not only by physical and environmental attributes but also by emotional connections and individual attitudes. Given the established interrelations between urban parks, place attachment, and perceived restoration, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Place attachment mediates the relationship between urban parks and young adults’ perceived restoration.

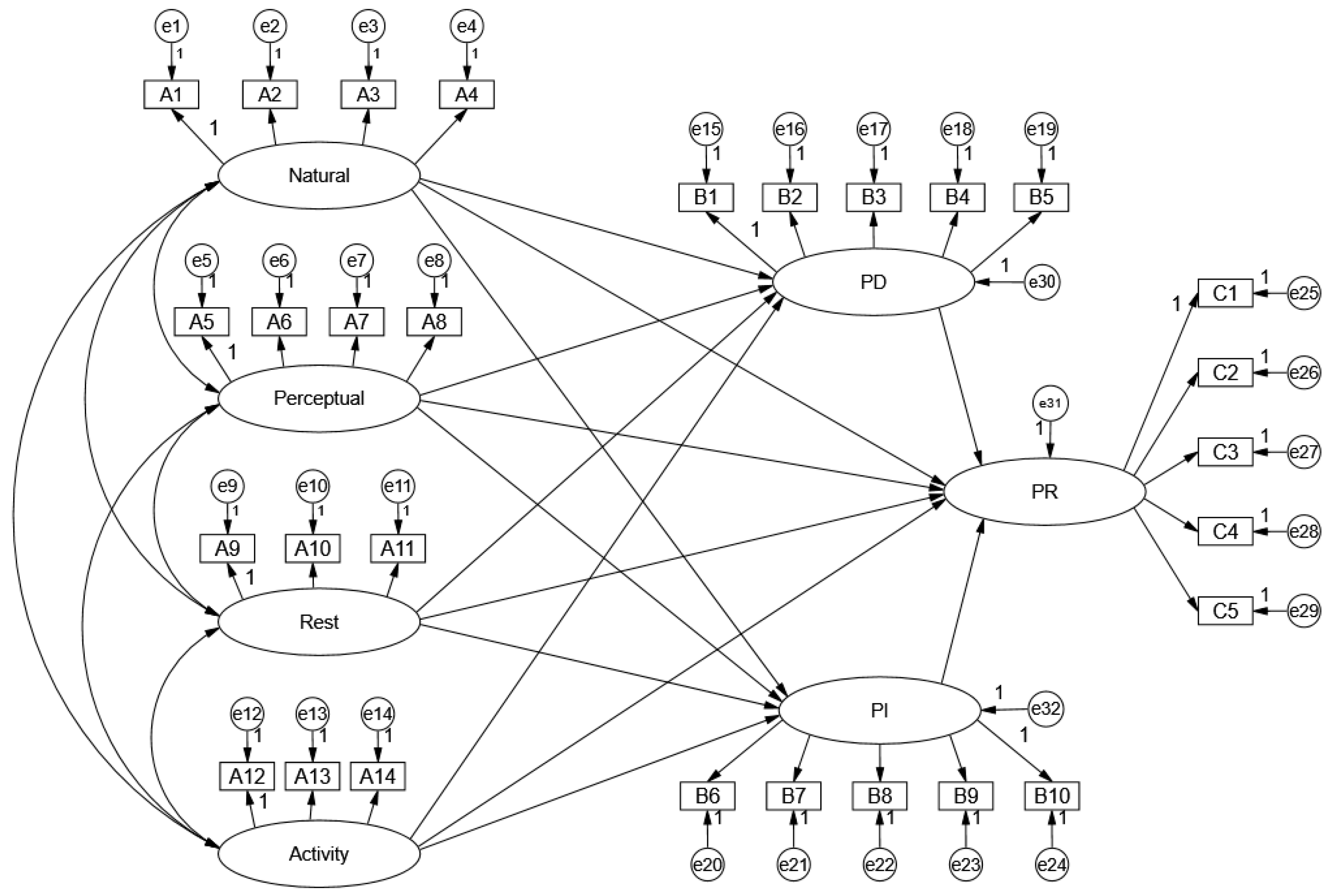

In summary, this study aims to explore the mediating role of place attachment in the relationship between urban parks and the perceived restoration of young adults'. To address this objective, a hypothetical model (illustrated in

Figure 1) is developed, which examines the interconnections among urban park attributes, place attachment, and perceived restoration. By investigating these relationships, the study seeks to provide actionable insights for urban park design and management, contributing to improved mental health outcomes for young populations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Study Area

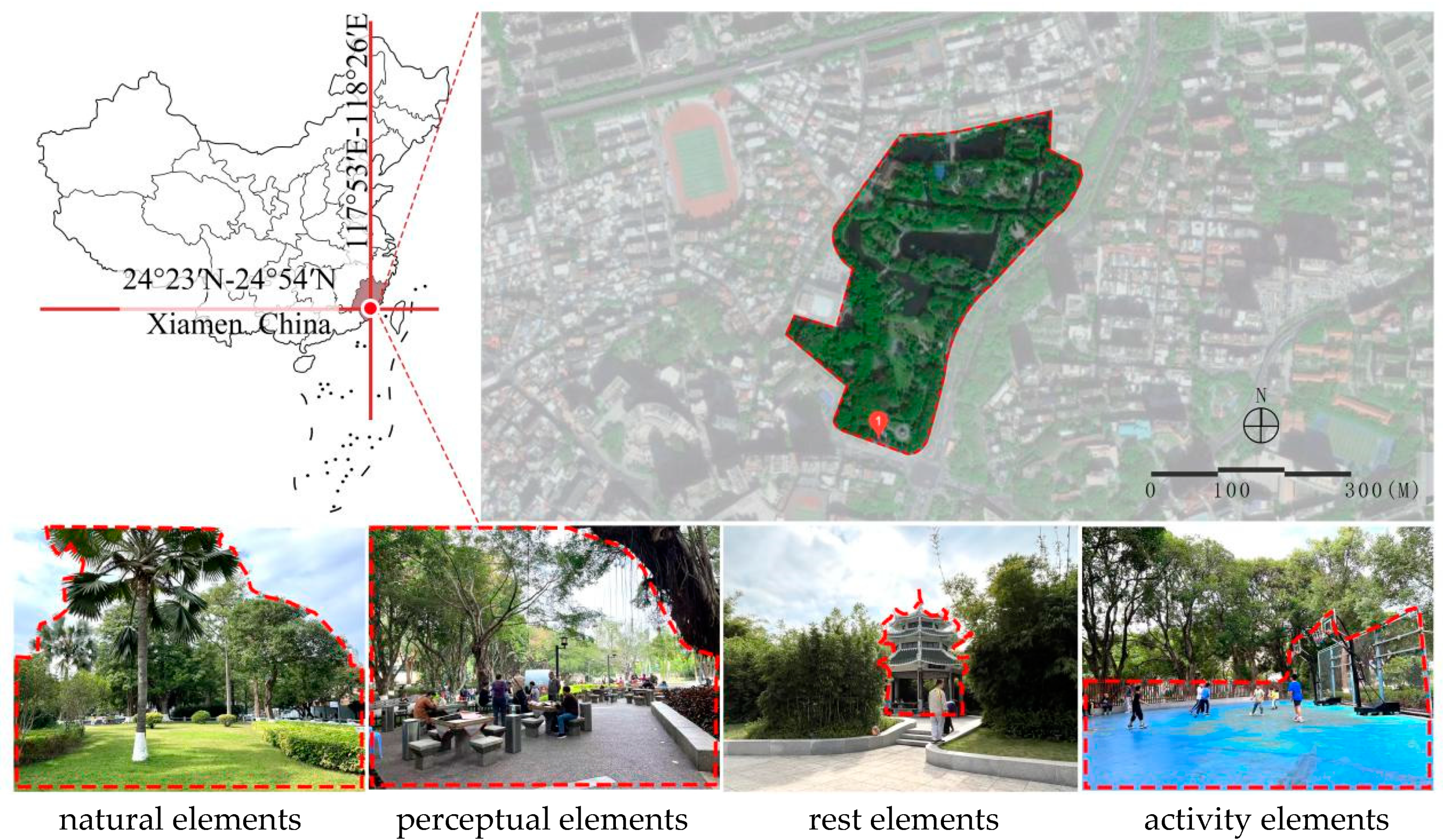

Xiamen, a coastal city in eastern China, had a Gross Domestic Product of approximately 111 billion USD by the end of 2023, with an urban area covering around 1,700 km² and a permanent population of 5.327 million. This study selected Zhongshan Park, located in Xiamen's central district, as the research site (

Figure 2). The park is situated in an area characterized by high building density, a substantial residential population, and well-developed recreational and sports facilities, aligning with the criteria required for this study.

3.2. Questionnaire Design, Data Collection and Analysis Methods

3.2.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire utilized in this study was meticulously structured into four distinct sections to comprehensively gather relevant data:

1. Demographic information: This section aimed to collect statistical data on urban park visitors, focusing on variables such as gender, age, education, and occupation. The study specifically targeted individuals aged 35-44 years, as this demographic often grapples with the dual responsibilities of career development, raising young children, and providing care for elderly family members [

4].

2. Urban park classification: Drawing upon Peng's framework [

40], this section categorized urban parks into 15 classes across four dimensions: natural elements, perceptual elements, activity elements, and rest elements. This classification facilitates a nuanced understanding of the diverse characteristics of urban parks.

3.Place attachment measurement: This section employed a measurement scale adapted from the research of Williams [

16], which encompasses 10 classes divided into two dimensions: place dependence and place identity. This approach allows for a thorough examination of the emotional and psychological connections individuals have with specific locations.

4. Perceived restoration assessment: Utilizing a self-assessment scale informed by the works of Peschardt, Diette, Maas, and Liu [

36,

37,

41,

45], this section included five classes designed to evaluate various aspects of perceived restoration. These aspects encompass fatigue elimination, vitality restoration, emotional calmness, and attention focus.

To ensure the validity of the questionnaire, the research team conducted a pre-survey following comprehensive training. This pre-survey, conducted in June 2024, garnered 91 responses. Participant feedback revealed semantic redundancy between the items "beautiful waterscape with strong ornamental value" and "rich waterscape" within the natural elements dimension. Consequently, the item "rich waterscape" was removed from the questionnaire. All other items exhibited satisfactory performance during the pre-survey, leading to the refinement of the urban park evaluation scale, which now comprises 14 classes. The finalized questionnaire employed a seven-point Likert scale to measure participant responses, ensuring a robust assessment of the constructs under investigation.

3.2.2. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

- 1)

Data collection

The survey was conducted utilizing a random sampling approach, specifically targeting young individuals visiting urban parks. Recognizing that many young adults' are typically engaged with work commitments during weekdays, data collection was strategically scheduled for weekends between July and September 2024. Surveys were administered during two peak attendance periods: from 7:00 to 10:00 a.m. and from 4:00 to 6:00 p.m., when park visitation rates were notably higher and temperatures were more conducive to outdoor activities. To ensure that respondents fully understood the questionnaire, detailed explanations were provided prior to their completion. A total of 330 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in 312 valid responses and achieving a commendable response rate of 94.54%.

- 2)

Data analysis methods

The study employed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) to rigorously test the proposed hypotheses. CFA was utilized to evaluate the relationships between observed and latent variables, thereby confirming the correlations posited in the proposed model. Following the guidelines established by the scholar named Hair, two critical indicators were employed to assess the validity of the CFA: composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). A CR value exceeding 0.6 indicates strong internal consistency of the construct, while an AVE value greater than 0.5 suggests that the latent variable effectively accounts for the variance in the observed variables [

37].

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to assess the relationships and strengths of correlations among latent variables. Hypotheses were evaluated by examining various goodness-of-fit indices, including the normed chi-square ratio (χ²/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). SEM analyses were conducted only after ensuring that the CFA indicators met the necessary thresholds. Additionally, bootstrapping techniques were applied to investigate the mediating effects between variables. Data preprocessing was performed using SPSS 24, while AMOS 23 was used for model testing and hypothesis validation.

4. Results

4.1. Basic Characteristics of the Sample

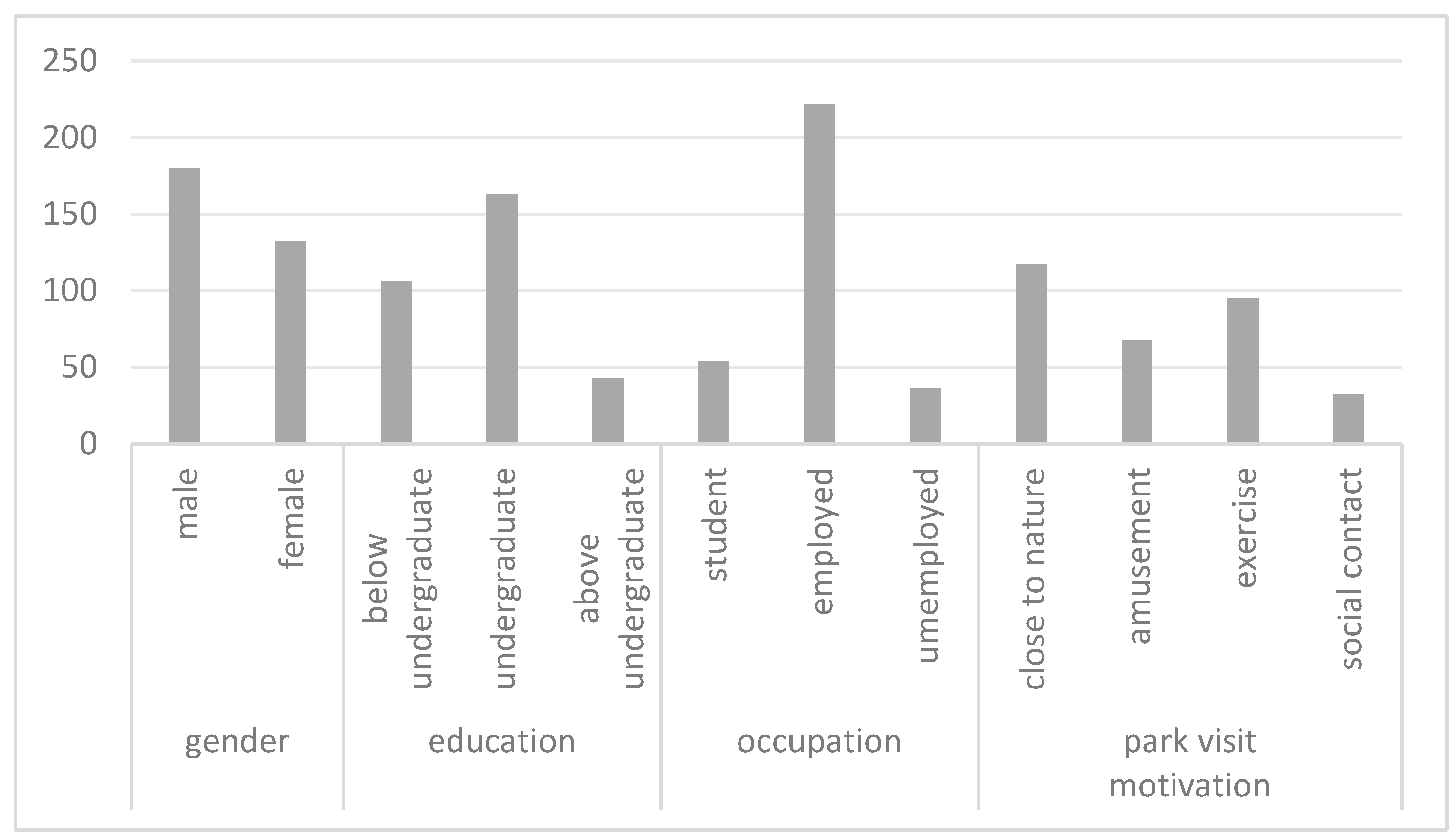

The demographic characteristics of the questionnaire participants are illustrated in

Figure 3. Analysis of the valid sample revealed that 57.7% of respondents were female, while 42.3% were male. Regarding age distribution. Educational attainment showed that 66.2% of respondents held a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 33.8% had a bachelor’s degree or lower. In terms of occupation, the majority of respondents were office workers, comprising 71.3% of the sample. Students accounted for 17.3%, and unemployed individuals made up 11.4% of the respondents. Participants' primary reasons for visiting the park varied, with the largest proportion (37.5%) citing proximity to nature as their motivation. Physical exercise was reported by 30.4% of respondents, while 21.8% visited for leisure and entertainment, and 10.3% for social interaction.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

The reliability and validity analysis yielded results presented in

Table 1. The indices measured in the study—including natural elements, perceptual elements, rest elements, and activity elements of urban parks, as well as place dependence and place identity within place attachment, and perceived restoration—demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha values exceeding 0.8.

Furthermore, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values for all indexes were above 0.7, the CR values were all greater than 0.8, and the AVE values exceeded 0.5, confirming indexes with good convergent validity and reliability. These results suggest that the questionnaire is consistent, stable, and suitable for confirmatory factor analysis.

4.3. Hypothesis Model Analysis

The SEM was evaluated for goodness-of-fit to determine whether the model met the recommended thresholds for fit indices. The analysis produced the following results: x²/df = 1.402 (< 5), RMSEA = 0.036 (< 0.08), GFI = 0.902 (> 0.9), IFI = 0.969 (> 0.9), NFI = 0.907 (> 0.9), CFI = 0.969 (> 0.9), and TLI = 0.964 (> 0.9). These values indicate that the model demonstrates a good fit to the data and satisfies the established criteria for model adequacy.

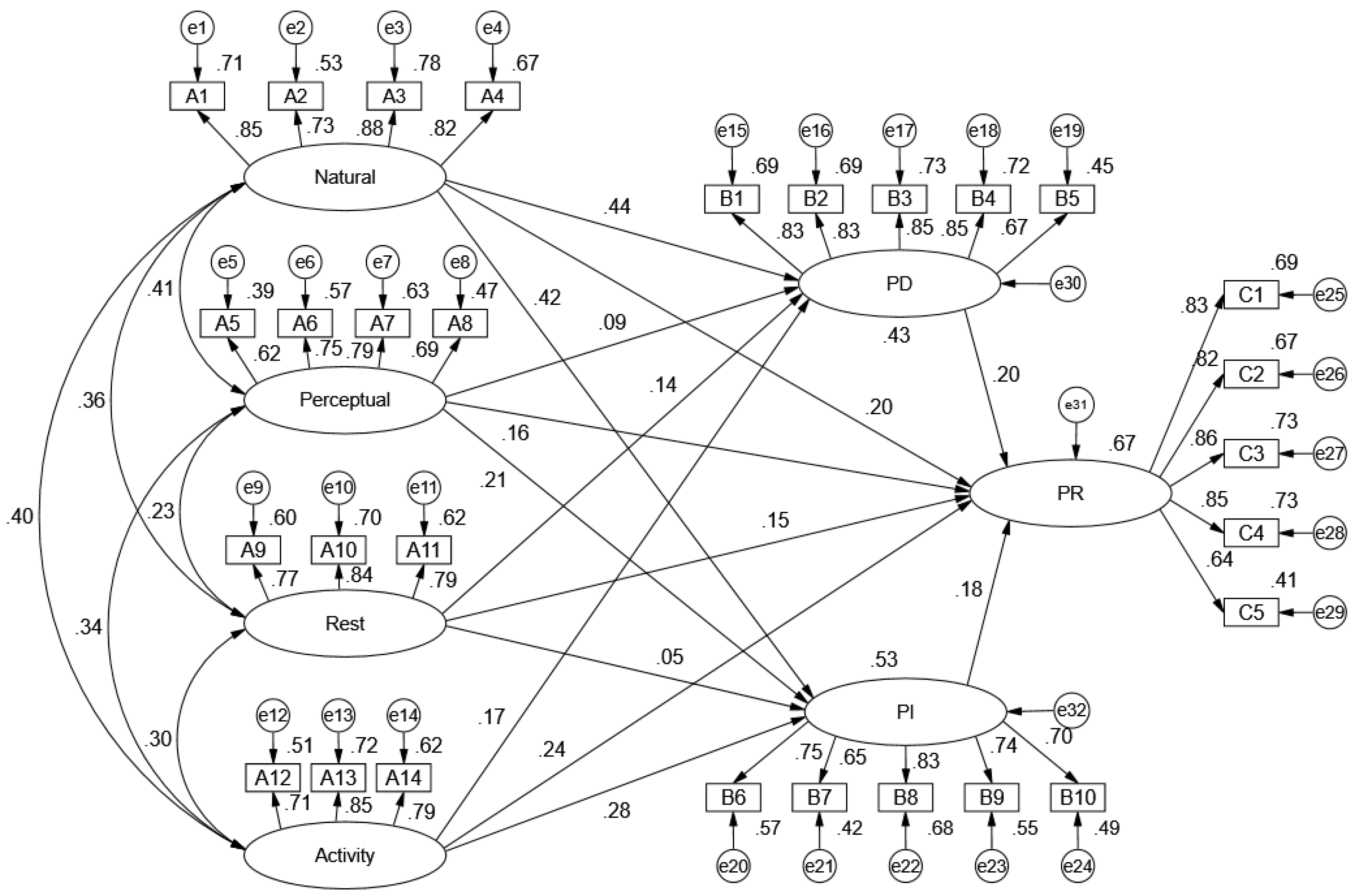

The final SEM results are presented in

Figure 4. The influence of each latent variable is assessed through the magnitude of the path coefficients, while the CR values and p-values are used to evaluate the validity of these coefficients. A path coefficient is considered significant if the CR value exceeds 1.96 or if the p-value is less than 0.05.

As presented in

Table 2, all four elements of the urban park exert a significant positive effect on young adults' perceived restoration (p < 0.05), confirming hypotheses H1a1, H1a2, H1a3, and H1a4. The standardized path coefficients of these elements on perceived restoration, ranked in descending order, are as follows: activity element (0.24) > natural element (0.20) > perceptual element (0.16) > rest element (0.15). Among these, the activity element demonstrates the strongest impact.

Regarding the relationship between urban park and place dependence, natural elements, rest elements, and activity elements have significant positive effects (p < 0.05), validating hypotheses H2a1, H2a5, and H2a7. The standardized path coefficients for these elements are as follows: natural elements (0.44) > activity elements (0.17) > rest elements (0.154), indicating that natural elements provide the greatest contribution to place dependence. Conversely, the perceptual element's effect on place dependence was not significant (p = 0.136 > 0.05).

Similarly, natural elements, perceptual elements, and activity elements significantly influence place identity (p < 0.05), supporting hypotheses H2a2, H2a4, and H2a8. The standardized path coefficients, in descending order, are: natural elements (0.42) > activity elements (0.28) > perceptual elements (0.16). Natural elements again exhibit the strongest impact on place identity, while the effect of rest elements on place identity was not significant (p = 0.219 > 0.05).

Additionally, the two dimensions of place attachment, place dependence and place identity, significantly and positively impact perceived restoration (p < 0.05), confirming hypotheses H2a9 and H2a10. These findings highlight the mediating role of place attachment in the relationship between urban parks and perceived restoration.

A mediation effect analysis was performed within the SEM model to further examine the multidimensional pathways through which the urban park influences young adults' perceived restoration. As detailed in

Table 3, the findings reveal that the urban park not only directly impacts young adults' perceived restoration but also enhances it indirectly through the mediating role of place attachment. This indicates that place attachment serves as a significant intermediary mechanism, amplifying the restorative effects of urban park on visitors.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Influence of Urban Park on Young Adults’ Perceived Restoration

The findings of this study indicate that the four elements of the urban park significantly and positively influence young adults' perceptions of health benefits. This direct impact is consistent with Peschardt’s research on the relationship between urban parks and visitors’ perceived restoration [

41,

45]. Among these elements, the activity component exerts the most substantial influence on young adults' perceptions of health benefits. This finding underscores the widely accepted notion that engaging in appropriate physical activities is essential for promoting overall health and well-being [

46,

47]. Consequently, the design and inclusion of diverse and dynamic activity spaces within urban parks are critical for enhancing the well-being of young individuals.

Natural elements also play a pivotal role in supporting the physical and mental health of young adults'. Research has demonstrated that interaction with nature can alleviate anxiety and improve mental health outcomes [

12,

13]. Therefore, incorporating diverse vegetation and aesthetically pleasing water features in park design is particularly valuable for young residents in densely urbanized areas.

Furthermore, the perceptual and rest elements contribute meaningfully to the health and well-being of young individuals. Secluded spaces and tranquil atmospheres facilitate social interactions among young visitors, while comfortable rest areas oriented toward scenic landscapes encourage prolonged stays in the park. Collectively, these features enhance the restorative experiences and health benefits derived from urban parks.

5.2. Place Attachment as a Mediator of Urban Parks' Impact on Young Adults' Perceived Restoration

The results of this study indicate that place attachment serves as an incomplete mediator in the relationship between urban parks and young adults' perceived restoration. Two distinct pathways were identified: the first being “urban park → place dependence → young adults’ perceived restoration,” and the second being “urban park → place identity → young adults’ perceived restoration.” This outcome may be attributed to the fact that the development of place dependence and place identity can increase the frequency of young adults' visits to parks [

16], or it may create a more relaxing environment for them [

30,

48]. Both factors contribute to an enhanced perception of restoration among young individuals.

Different elements of urban parks exert varying effects on place dependence and place identity, which are discussed in the following contents.

In the dimension of place dependence, natural elements, rest elements, and activity elements all demonstrate significant positive effects. Among these, natural elements exert the greatest influence on place dependence, aligning with findings from previous studies [

49]. This suggests that young adults' exhibit the highest functional dependence on the presence of plant species, their abundance, and aesthetically pleasing water features. While sports facilities, resting areas, and activity venues within urban parks also contribute positively to the establishment of place dependence, the impact of perceptual elements appears to be negligible.

This observation, supported by qualitative interviews with young participants, indicates that for many young individuals, the primary motivations for visiting parks are to engage with nature, relax, and exercise. Consequently, sports and rest facilities adequately meet their needs, while spatial design elements may have less relevance to their functional requirements.

In the context of place identity, natural elements, perceptual elements, and activity elements all significantly influence young adults' emotional identification. Notably, natural elements have the most pronounced effect on place identity, corroborating findings from earlier research [

23]. This underscores the strong emotional connection that young adults' have with natural elements, further emphasizing the importance of these elements.

Although activity elements and perceptual elements also positively impact the development of place identity, the influence of rest elements is not significant. This may be attributed to insights gathered from interviews, where young participants expressed that the aesthetic appeal of resting facilities—such as pavilions, benches, and pergolas—within Zhongshan Park is relatively low. Consequently, this lack of attention to rest elements may explain their insignificant impact on place identity.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

Several limitations of this study warrant acknowledgment. First, the research did not incorporate longitudinal tracking to examine the relationship between respondents' perceived restoration and their frequency of park visits. This omission limits the understanding of how these variables may interact over time. Future research could address this gap by implementing follow-up studies that monitor the long-term dynamics of this relationship, providing a more comprehensive view of the impact of urban parks on perceived restoration.

Second, this study did not control for specific demographic factors that could influence the overall conceptual model. Variables such as gender, age, and education were not included as control variables, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Future research could enhance the robustness of these results by conducting subgroup analyses based on these demographic factors, thereby evaluating their impact on the relationships between urban parks, place attachment, and perceived restoration.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the role of place attachment in mediating the relationship between urban park and young adults' perceived restoration, thereby establishing an initial impact mechanism. The findings demonstrate that urban park can directly enhance young adults' perceived restoration and indirectly influence it through the mediating effect of place attachment. This mediation operates through two pathways, with the path involving place dependence proving more effective than the one involving place identification. These insights extend the scope of research on the health benefits of urban park for young visitors and provide practical guidance for creating youth-friendly environments in urban park renewal projects. Additionally, the study complements existing health research on highly stressed demographic groups in China.

Additionally, the study revealed that different elements of urban park—natural elements, perceptual elements, rest elements, and activity elements—affect the two dimensions of place attachment (place dependence and place identification) in distinct ways. Natural and activity elements positively contribute to the formation of both place dependence and place identification, with natural elements exerting the strongest influence. However, perceptual elements were not significantly associated with place dependence, and rest elements did not significantly contribute to place identification. These findings hold significant implications for fostering stronger emotional connections between young visitors and urban parks, aiding in the design of environments that effectively support place attachment.

Author Contributions

Research methodology, software, data correction, C.R.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, editing, M.T.Z; data collection, Y. Y.; review and editing, L.Z.G, and P.H.

Funding

Please add:The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Zhangzhou College of Science & Technology grant number 2k202309.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Potwarka, L.R.; Smale, B.J.A.; Havitz, M.E. Association of Parkland Proximity with Neighborhood and Park-Based Physical Activity: Variations by Gender and Age. Leisure Sciences 2009, 31, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.H.; Knuiman, M.; Collins, C.; Douglas, K.; Ng, K.; Lange, A.; Donovan, R.J. Increasing Walking: How Important Is Distance to, Attractiveness, and Size of Public Open Space? American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Saini, A. ; KironJeet Sustaining Mental Health amidst High-Pressure Job Scenarios: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Pellegrini, P.; Ma, J.; Shi, L. Investigating the Influence of Elements in Pocket Parks on the Psychological Restoration of Young People: A Study from Guiyang and Chongqing in Southwest China. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 0, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Rockett, I.R.H.; Lv, Q.; Cottrell, R.R. Stress Status and Related Characteristics among Urban Residents: A Six-Province Capital Cities Study in China. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e30521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Attention and Emotion Recovery Effects of Urban Parks during COVID-19—Psychological Symptoms as Moderators. Forests 2022, 13, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Bardwell, L.V.; Slakter, D.B. The Museum as a Restorative Environment. Environment and Behavior 1993, 25, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Rodiek, S.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y. Stress Recovery and Restorative Effects of Viewing Different Urban Park Scenes in Shanghai, China. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2016, 15, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W. & G. Validation of a Measure of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness.; Department of Psychology, Göteborg University: Göteborg, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, P.J.; Jung, T.; Swenson, A. Effects of the Aural and Visual Experience on Psycho-Physiological Recovery in Urban and Rural Environments. Applied Acoustics 2020, 169, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, X. White Spaces Unveiled: Investigating the Restorative Potential of Environmentally Perceived Characteristics in Urban Parks during Winter. Forests 2023, 14, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebel, K.; Marselle, M.; Dean, A.J.; Rhodes, J.R.; Bonn, A. Urban Green Space Soundscapes and Their Perceived Restorativeness. People and Nature 2021, 3, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Li, X.; Yang, T.; Tan, S. Research on the Relationship between the Environmental Characteristics of Pocket Parks and Young People’s Perception of the Restorative Effects—A Case Study Based on Chongqing City, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, D.; Fulthorp, K.; Paris, C.M. Examining the Relationship between Place Attachment and Behavioral Loyalty in an Urban Park Setting. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2019, 25, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative Experience and Self-Regulation in Favorite Places. Environment and Behavior 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursyamsiah, R.A.; Setiawan, R.P. Does Place Attachment Act as a Mediating Variable That Affects Revisit Intention toward a Revitalized Park? Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 64, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. Forest Science 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Shi, J.; Lu, T.; Furuya, K. Sit down and Rest: Use of Virtual Reality to Evaluate Preferences and Mental Restoration in Urban Park Pavilions. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 220, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-J.; Ho, L.-C.; Suppakittpaisarn, P. Investigating the Interplay between Senior-Friendly Park Features, Perceived Greenness, Restorativeness, and Well-Being in Older Adults. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2024, 94, 128273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Visual and Auditory Environments in Parks on Visitors’ Landscape Preference, Emotional State, and Perceived Restorativeness. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2024, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Sun, Y.; Beckmann-Wübbelt, A.; Saha, S. Characteristics of Urban Park Recreation and Health during Early COVID-19 by on-Site Survey in Beijing. npj Urban Sustain 2023, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Fu, E.-K.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.-X.; Huang, Z.; Cai, S.-Z.; Jia, Y. Empirical Study of Landscape Types, Landscape Elements and Landscape Components of the Urban Park Promoting Physiological and Psychological Restoration. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2020, 48, 126488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Jia, T. Humanization of Nature: Testing the Influences of Urban Park Characteristics and Psychological Factors on Collegers’ Perceived Restoration. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2023, 79, 127806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, Md.; Teimouri, R.; Degirmenci, K.; Alanjagh, F.A. Association between Park Visits and Mental Health in a Developing Country Context: The Case of Tabriz, Iran. Landscape and Urban Planning 2020, 199, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapuano, M.; Ruotolo, F.; Ruggiero, G.; Masullo, M.; Maffei, L.; Galderisi, A.; Palmieri, A.; Iachini, T. Spaces for Relaxing, Spaces for Recharging: How Parks Affect People’s Emotions. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2022, 81, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, Y. Public Emotions and Visual Perception of the East Coast Park in Singapore: A Deep Learning Method Using Social Media Data. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2024, 94, 128285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shi, S.; Runeson, G. Developing Place Attachment in Master-Planned Residential Estates in Sydney: The Influence of Neighbourhood Parks. Buildings 2023, 13, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, M.; Spielhofer, R.; Wissen Hayek, U.; Kienast, F.; Grêt-Regamey, A. Greater Place Attachment to Urban Parks Enhances Relaxation: Examining Affective and Cognitive Responses of Locals and Bi-Cultural Migrants to Virtual Park Visits. Landscape and Urban Planning 2023, 232, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, M.; Meng, Q.; Yang, D.; Liu, F. Effects of Forest on Birdsong and Human Acoustic Perception in Urban Parks: A Case Study in Nigeria. Forests 2022, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.; Hartig, T.; Markevych, I.; Tilov, B.; Dimitrova, D. Urban Residential Greenspace and Mental Health in Youth: Different Approaches to Testing Multiple Pathways Yield Different Conclusions. Environmental Research 2018, 160, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakınlar, N.; Akpınar, A. How Perceived Sensory Dimensions of Urban Green Spaces Are Associated with Adults’ Perceived Restoration, Stress, and Mental Health? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2022, 72, 127572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, M.; Tabrizi, A.M.; Bauer, N.; Kienast, F. Place Attachment through Interaction with Urban Parks: A Cross-Cultural Study. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 61, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Dong, S.; Wu, H.C.; Li, Y.; Su, T.; Xia, B.; Zheng, J.; Guo, X. Key Impact Factors of Visitors’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviour: Personality Traits or Interpretive Services? A Case Study of Beijing’s Yuyuantan Urban Park, China. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 2018, 23, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Huang, Q.T.; Lan, S.R. Tourists’ environmental preferences, perceived restoration and perceived health at Fuzhou National Forest Park. Resources Science 2018, 40, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-515309-3.

- Wilkie, S.; Clements, H. Further Exploration of Environment Preference and Environment Type Congruence on Restoration and Perceived Restoration Potential. Landscape and Urban Planning 2018, 170, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, L.; Huang, S. (Sam); Xiong, Q. Impact of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness on Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavior: Examining the Mediation of Place Attachment and the Moderation of Ecocentrism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 56, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.Y.; Tan, S.H. Study on the Influencing Mechanism of Restoration Effect of Urban Park Environment: A Case Study of Chongqing. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2018, 34, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Associations between Park Characteristics and Perceived Restorativeness of Small Public Urban Green Spaces. Landscape and Urban Planning 2013, 112, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diette, G.B.; Lechtzin, N.; Haponik, E.; Devrotes, A.; Rubin, H.R. Distraction Therapy With Nature Sights and Sounds Reduces Pain During Flexible Bronchoscopya. Chest 2003, 123, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Vries, S. de; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green Space, Urbanity, and Health: How Strong Is the Relation? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, E.E.; Xiao, X.; Nettles, J.M.; Iretskaia, T.A.; Manning, R.E. Park Visitors’ Place Attachment and Climate Change-Related Displacement: Potential Shifts in Who, Where, and When. Environmental Management 2021, 68, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho-Pivoto, A.; Raimundo, S.; de Oliveira Santos, G.E. Contributions of Visitation in Parks to Health and Wellness: A Comparative Study between Natural and Urban Parks in Brazil. Tourism Planning & Development, 2024; 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions for Improving Depression, Anxiety and Distress: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Br J Sports Med 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallal, P.C.; Lee, I.-M.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Powell, K.E. The Future of Physical Activity: From Sick Individuals to Healthy Populations. Int J Epidemiol 2024, 53, dyae129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricchiolo, F.; Mosca, O.; Paolini, D.; Fornara, F. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment Dimensions in the Relationship Between Local Social Identity and Well-Being. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 645648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, R.; Basu, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Estoque, R.C.; Kumar, P.; Johnson, B.A.; Mitra, B.K.; Mitra, P. Residents’ Place Attachment to Urban Green Spaces in Greater Tokyo Region: An Empirical Assessment of Dimensionality and Influencing Socio-Demographic Factors. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2022, 67, 127438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).