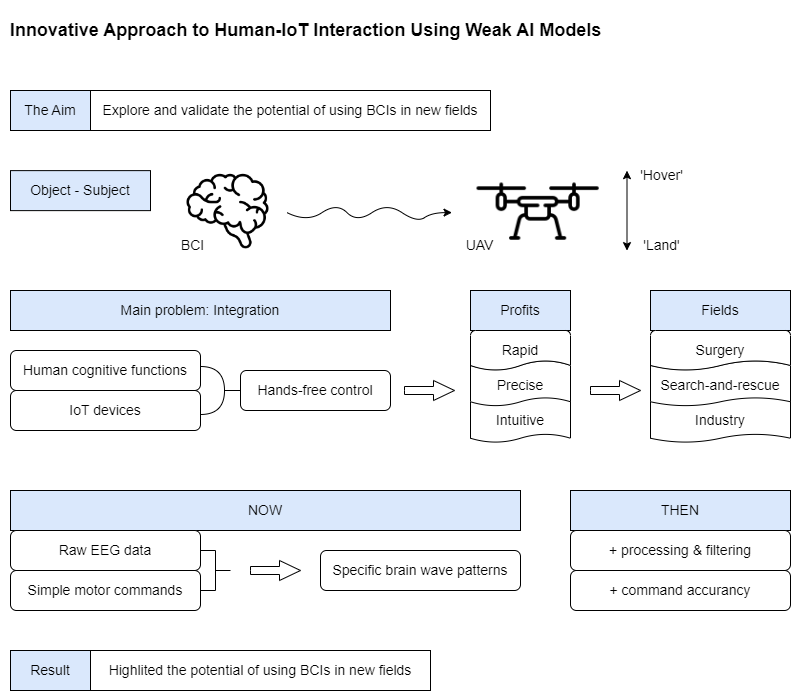

Introduction

The swift advancement of technology in recent decades has facilitated the adoption of increasingly complex and sophisticated methods across various aspects of life. Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and artificial intelligence (AI), in particular, have paved the way for innovative solutions across industries such as healthcare, robotics, and the Internet of Things (IoT). These technologies allow for direct interaction between human cognitive functions and external systems, transforming how we engage with machines. IoT, combined with BCIs, has enhanced everything from smart homes to advanced manufacturing processes [

1],[

2]. As IoT technologies evolve, the prospect of integrating BCIs for more direct and intuitive positioning of objects in space becomes increasingly feasible.

One of the more promising areas of research involves the use of neural interfaces, specifically EEG (Electroencephalography)-based systems, to control devices such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Neural interfaces could provide a means of solving some of the major challenges facing UAV control, including response speed, accuracy of actions, and accessibility to remote locations. Traditional manual controls are often slow and prone to human error, particularly in dynamic and challenging environments. By leveraging neural interfaces to bypass these limitations, users could control UAVs with higher precision and reduced latency [

3].

The novelty of this work lies in introducing a streamlined approach to translating EEG signals into fundamental UAV commands, focusing specifically on basic yet actionable motor instructions like "hover" and "land." This method leverages raw EEG data to recognize simple motor commands, providing a foundation for future applications requiring six degrees of freedom (6 DOF) in UAV control. Testing this novel approach under real-world conditions lays essential groundwork for more advanced control frameworks and demonstrates the potential for achieving hands-free, accurate operation with minimal latency. By doing so, this study seeks to establish a robust, accessible solution for EEG-driven control, addressing both technological limitations and practical use cases across high-impact sectors.

This approach has far-reaching potential in a variety of domains. For instance, controlling UAVs in hard-to-reach regions—such as during search-and-rescue missions, disaster recovery, or environmental monitoring—could be greatly enhanced by a neural interface system, allowing for hands-free operation. Another area where this technology could be revolutionary is in healthcare, particularly in minimally invasive surgery, where precision, control, and real-time response in hard-to-reach areas are essential for success [

5].

This study aims to determine how promising neural interfaces can enhance response speed and positioning accuracy, particularly in remote or difficult-to-access environments. To achieve this goal, the feasibility of using EEG signals to control UAVs in real-world scenarios was assessed. Specifically, the research in its first stage focuses on whether these brain signals can be effectively translated into UAV commands, improving operational precision and response time.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Programs

This study utilized two key publicly available software tools for EEG signal acquisition, participant training, and data export: EmotivBCI and EmotivPro by EMOTIV [

9], [

10]. EmotivBCI (version 4.3.15.387) (free tool) was used to create training profiles for each participant. After the training sessions, the EmotivPro software (version 4.3.15.559) (paid monthly subscription) was employed to record live EEG signals during the execution of the trained commands. This software enabled the export of raw Electroencephalography (EEG) data, which will be used in the future for further analysis and preprocessing.

2.2. Devices

The Emotiv Epoc X (version 3) neural interface by EMOTIV was used for capturing EEG signals during participant training and subsequent command execution. This 14-channel EEG headset is commercially available and designed for high-resolution brainwave monitoring. The device is equipped with built-in applications that allow real-time data acquisition and signal processing. The Emotiv Epoc X records neural activity through its sensors and interfaces seamlessly with EmotivBCI and EmotivPro for data capture and live monitoring.

2.3. Process

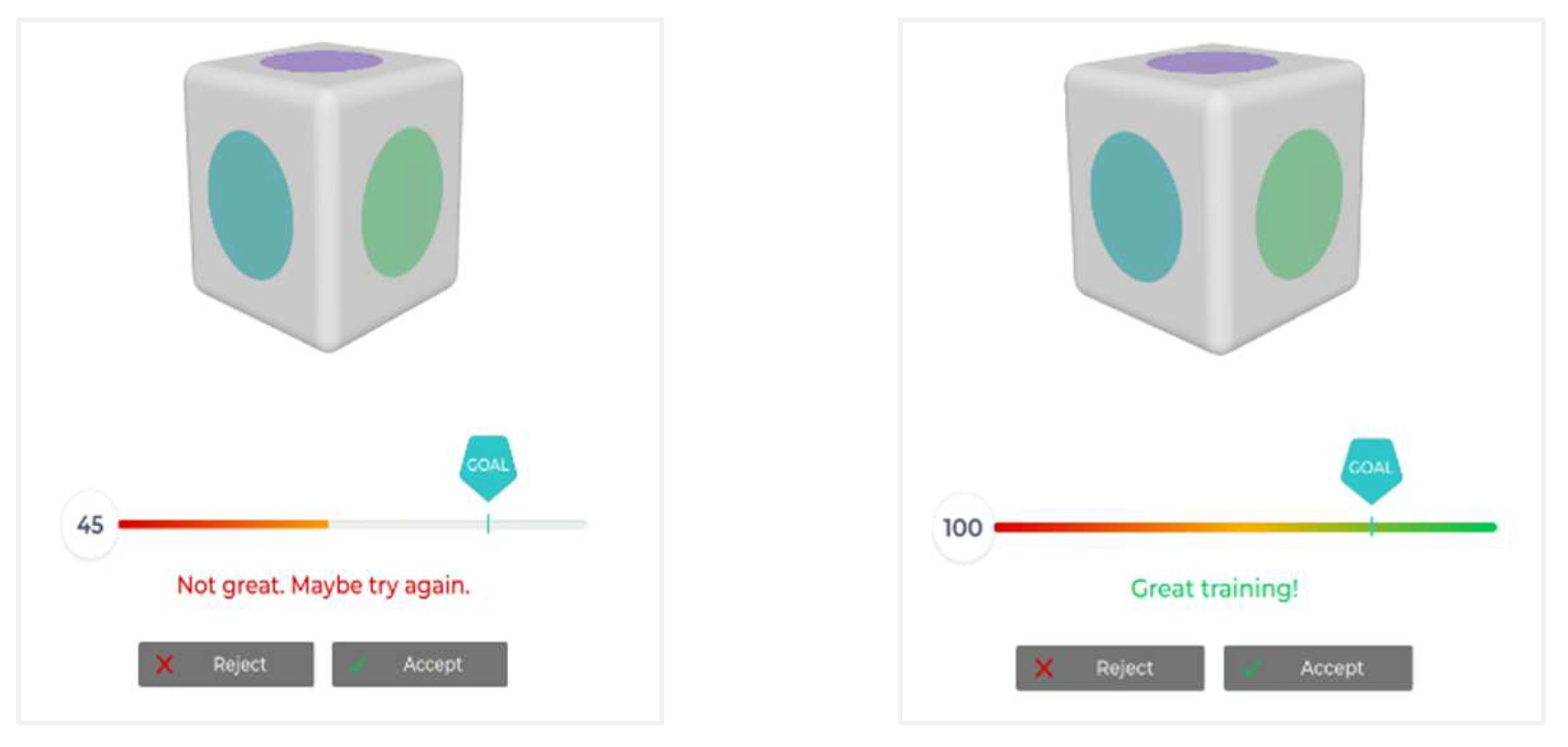

The study began with participants undergoing a standard training phase using the EmotivBCI software as shown in

Figure 1. During this phase, participants learned to perform two specific actions—raising their hand (to signal "upward") and lowering their hand (to signal "downward")—while wearing the Emotiv Epoc X device. These movements were repeated multiple times to ensure both the participants and the system could reliably detect the associated EEG signals. After the training profiles were established as shown in

Figure 2. , participants proceeded to live EEG recordings as shown in

Figure 3 were their frequency domain power distribution of Alpha, Beta, Theta and Gamma were recorded. EmotivPro was used to record live EEG signals during the execution of the "upward" and "downward" commands. The raw EEG data was then exported using EmotivPro’s paid export feature for further analysis and signal processing.

Training process for participant on EmotivPRO. The beginning of training shows the reference object (the box) with 8 seconds timer at the bottom(per training) for the participant to execute the command, i.e., “upward”, “downward”, “neutral”. Once the profile is trained by the participant for 2 iterations using mental command and movement of hand in the direction of intended command the participants on the 3rd iteration onwards need to reach the training goal(Left Image: goal not reached; Right image: goal reached) they made to create a good training profile as shown in

Figure 2.

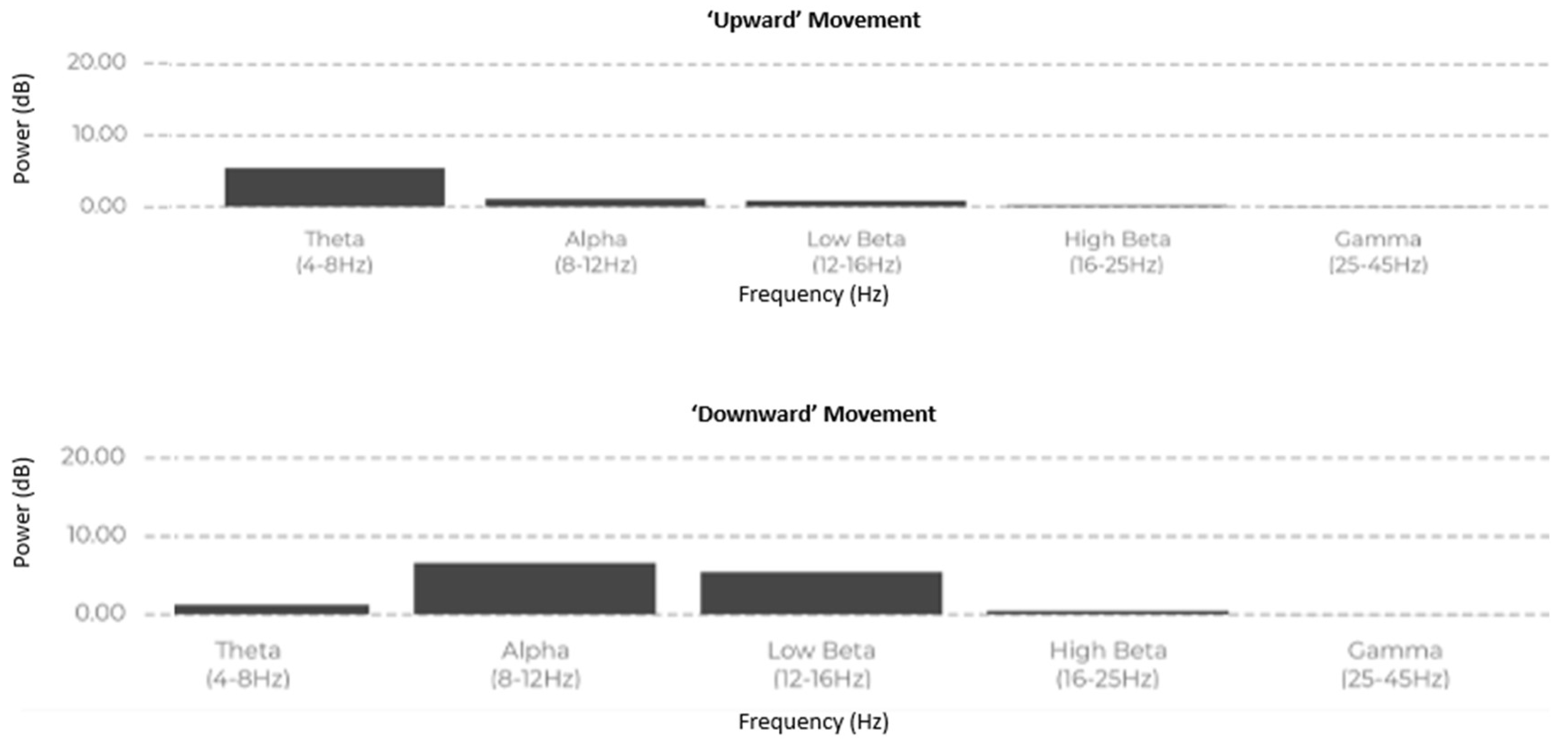

As seen from

Figure 3 showing the breakdown of power across Theta, Alpha, and Beta bands(x-axis) in Hertz against band power(y-axis) in decibels(dB), which are relevant for motor control and cognitive engagement during movement, the analysis of power spectral density across different frequency bands revealed distinct patterns between upward and downward hand movements. Specifically, in the theta band (4-8 Hz), power was higher during the upward movement compared to the downward movement, which may reflect a state of increased cognitive demand or motor inhibition during the upward action. In contrast, the alpha band (8-12 Hz) showed greater power in the downward movement, possibly indicating increased relaxation or motor preparation, consistent with findings that alpha activity often correlates with reduced cortical activation and motor readiness [

11].

The low beta band (12-16 Hz) exhibited similar power levels in both movements, with a slight increase in the downward movement. Beta activity is often linked to motor planning and movement execution, suggesting that both actions require similar motor control mechanisms, but with a marginally higher demand for the upward movement [

12]. In the high beta band (16-25 Hz), the downward movement also showed slightly elevated power, which may be indicative of enhanced motor control and cognitive processing during more complex motor tasks [

13]. Finally, the gamma band (25-45 Hz) displayed negligible power in both movements, suggesting minimal involvement of higher cognitive functions or synchronous neuronal activity typically associated with gamma oscillations [

14].

Overall, these results suggest that the upward movement involves more pronounced activity in the alpha and beta frequency bands, likely linked to motor preparation and execution. These frequency differences between motor movements could enable machine learning algorithms to effectively identify and classify these movements after further pre-processing of the raw EEG signals. This supports previous literature that associates different frequency bands with specific aspects of motor control, with alpha and beta bands being crucial for motor readiness and task execution [

15].

The two images in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate how distinct motor commands ("upward" vs. "downward") are represented differently in EEG signal amplitude, pattern, and frequency band power. While both movements activate motor-related frequencies (e.g., Beta), the slight variations in Alpha and Beta power might reflect the brain's adaptation to the specific direction of movement, impacting the precision and reliability of each command signal in BCI applications.

2.4. Participants

Participant demographics, including age, gender, hand dominance, and BCI experience, were recorded within the EmotivBCI system during the training phase. A total of 5 participants, aged 20–30, were recruited for this study. The participants were healthy adults with no neurological disorders and were selected based on their willingness to participate in non-invasive BCI research.

Below is a table of participants demographic after they have agreed and signed an informed consent about sharing such information.

Table 1.

Participants Demographics.

Table 1.

Participants Demographics.

| Participants |

Sex |

Age |

Handedness |

Education Level |

Nature of Occupation |

BCI experience (Yes/No) |

| Participant 1 |

M |

29 |

right-handed |

Master's |

Phd. Student |

No |

| Participant 2 |

M |

23 |

right-handed |

Master's |

Phd. Student |

No |

| Participant 3 |

M |

20 |

right-handed |

Bachelors |

Programmer |

Yes |

| Participant 4 |

M |

20 |

right-handed |

Bachelors |

Programmer |

No |

| Participant 5 |

M |

25 |

right-handed |

Master's |

Programmer |

Yes |

Results

Participants exhibited varied levels of engagement and response to the tasks, with some demonstrating rapid adaptation to the EEG-based control commands, while others required additional training to achieve consistent EEG signal patterns. These differences highlighted both the potential and the challenges in using EEG signals for intuitive control. Specific cases included participants whose EEG signals showed strong Beta wave activity during motor command execution, correlating with smoother task performance, while others exhibited greater Alpha activity, which might indicate less focused attention or readiness for motor tasks.

1.1. Practical Implementation

During the practical phase of this study, participants executed trained actions—raising their hand to signal "upward" and lowering their hand to signal "downward"—while wearing the Emotiv Epoc X headset. The primary focus was on recording raw EEG signals using EmotivPro as participants performed these commands, which simulated UAV’s upward’ and ‘downward’ movements. Only unprocessed, raw data was collected during this phase to assess the feasibility of capturing reliable brain signals for future stages of the project.

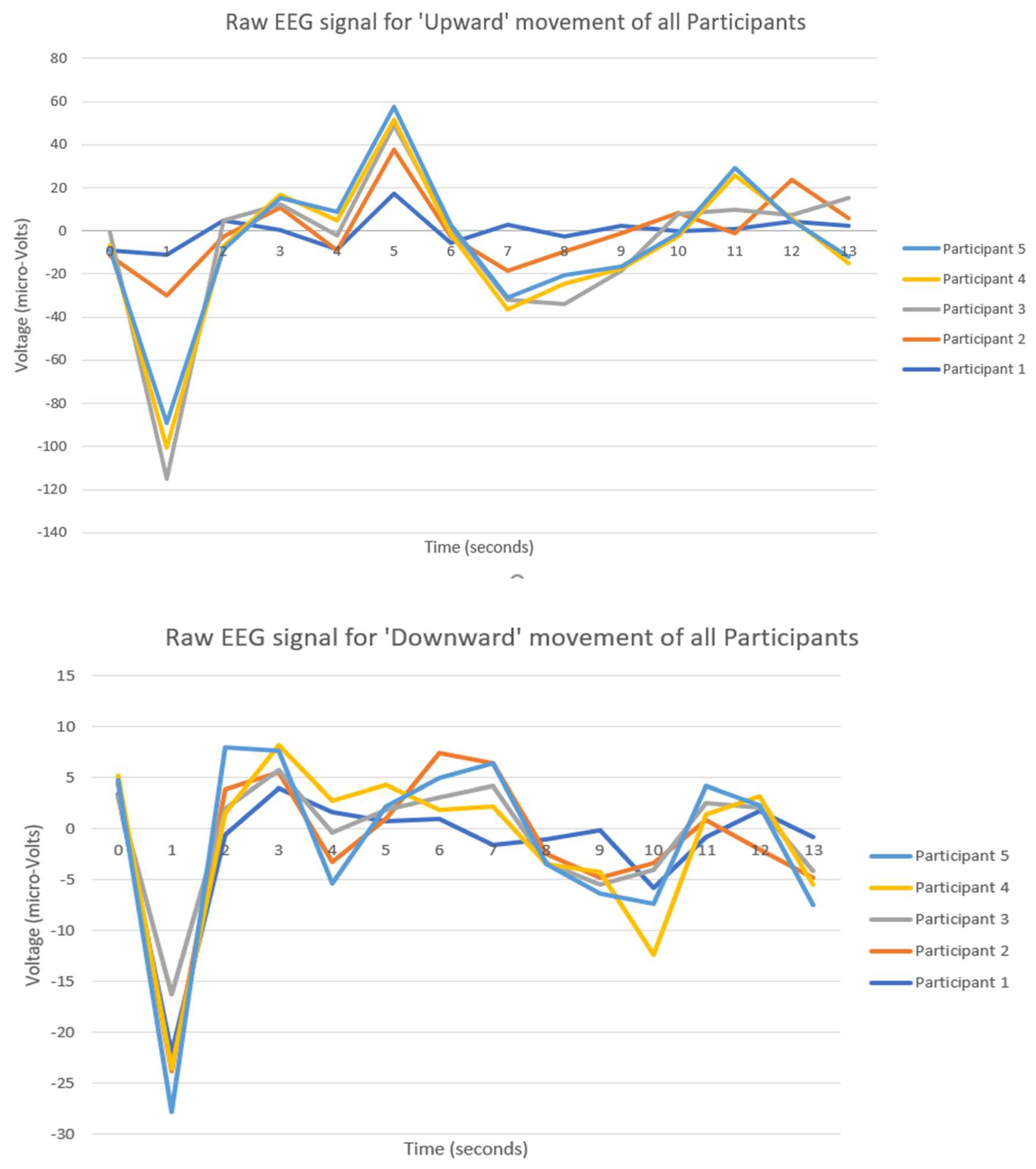

In the top image in

Figure 4, which represents EEG signals during the execution of the "Upward" movement, all participants display a similar overall pattern with distinct peaks and troughs, indicating a shared neural response to the movement. Specifically, there is a significant trough around the 2-second mark, where the voltage drops below -80 microvolts for each participant, likely reflecting a synchronized response to the initiation of the movement. Following this trough, a peak is observed between 4 and 5 seconds, reaching positive voltage values around 30–60 microvolts. Despite this common pattern, there are clear individual differences. The peak amplitude varies among participants, with Participant 1 reaching a higher voltage than others, while Participant 3 shows a relatively lower amplitude. Additionally, some participants display smoother curves, while others have more fluctuations, reflecting personal differences in brainwave intensity and variability.

In the bottom image in

Figure 4, which captures the EEG signals during the "Downward" movement, there is again a shared neural response pattern, with all participants showing an initial sharp trough around the 1-second mark, dipping below -20 microvolts, followed by a peak around the 2-second mark where voltages rise to around 5–10 microvolts. This indicates that, similar to the "Upward" movement, a common brain activation occurs in response to the movement. However, there are variations in how each participant’s EEG signal manifests. The depth of the initial trough is notably different, with Participant 1 reaching the deepest point, while other participants show shallower drops. The subsequent peaks and overall fluctuations vary as well, with some participants, like Participant 4, exhibiting smoother curves and others, such as Participant 2, displaying more distinct fluctuations in their signals.

In conclusion, both images demonstrate a shared neural response pattern among participants for each specific hand movement, indicating that these actions evoke a common brainwave activation. These consistent patterns observed in EEG signals across participants for specific movements, like the "Upward" and "Downward" actions, demonstrate a repeatable neural response associated with each type of movement. These shared neural patterns can serve as reliable markers that machine learning (ML) algorithms can use to classify different movements. By training an ML model on these patterns, the algorithm can learn to recognize the distinct neural signatures associated with "Upward" and "Downward" hand movements. Recent research, such as [

16], has demonstrated the effectiveness of using EEG-based movement classification through machine learning, highlighting its potential for applications in real-time control of external devices [

16]. Once trained, this model could classify new EEG signals in real time, effectively identifying when a person intends to perform specific movements based on the brainwave data alone. This classification capability could then be applied in control systems for devices like an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). For example, an individual could think of an "Upward" movement, and the ML algorithm, recognizing the corresponding EEG pattern, would interpret this as a command to make the UAV ascend. Similarly, the "Downward" movement pattern would translate to a descent command for the UAV.

Because the neural responses are shared across participants, the algorithm could be generalized or further trained with minimal data from new users, making it adaptable across a range of individuals. Thus, by leveraging these repeatable neural patterns, ML algorithms can create robust brain-computer interfaces that allow users to control complex systems, like UAVs, through thought-driven commands.

However, individual differences in amplitude, smoothness, and timing highlight variability in each participant’s neural processing of the movements. These differences may be attributed to unique physiological or cognitive factors that influence brainwave expression, even during the same task. Ultimately, this suggests that while EEG signals can reveal general neural responses to specific actions, they also capture individual nuances in brain activity that reflect personalized neural dynamics. This finding underscores the dual nature of EEG data: it reveals both universal and individual aspects of neural responses to physical actions according to [

17].

3.2. Feasibility and Future Steps

The feasibility of using raw EEG signals for UAV control depends on the ability to pre-process and refine these signals effectively. The next steps in the research will involve detailed analysis and filtering of the collected raw EEG data. Techniques such as band-pass filtering and noise reduction, specifically Independent Component Analysis (ICA), will be applied to clean the signals and extract relevant features. ICA has been effectively used in recent EEG studies to separate neural signals from noise, including muscle artifacts and eye blinks, as demonstrated by [

6]. This pre-processing step is essential to make the data fit for machine learning algorithms that can learn to recognize patterns associated with the "upward" and "downward" movements.

Key EEG frequency bands such as beta (13–30 Hz) and theta (4–8 Hz) waves play a critical role in distinguishing neural patterns related to motor control and cognitive tasks. Recent studies, including the work by [

7], have shown that beta waves are associated with motor activity and sensorimotor tasks, while theta waves are linked to focus and cognitive engagement. By refining the raw data into cleaner, more interpretable forms, future machine learning models will be able to classify these EEG patterns accurately, facilitating precise UAV control.

The initial findings suggest that it is feasible to record distinct raw EEG signals corresponding to the intended commands. However, to reliably use these signals for UAV control, additional pre-processing and signal enhancement steps are necessary to ensure machine learning models can accurately differentiate between the "upward" and "downward" movements. This study demonstrates that the initial capture of raw EEG signals is practical and offers a solid foundation for future work on improving signal quality, pattern recognition, and classification accuracy.

Discussion and conclusions

As seen in

Figure 3 the data aligns with known EEG patterns for motor activities:

Beta bands dominate, highlighting focus and motor control.

Alpha bands are slightly suppressed during upward movement, indicating higher cortical engagement compared to the downward movement.

Minimal Theta and Gamma activity reflects the absence of relaxation or higher -level cognitive tasks.

This suggests the upward movement demands slightly more cognitive and motor engagement than the downward movement.

In

Figure 4 key observations can be highlighted as the following:

The graph for the "Upward" movement shows a significantly larger range of voltage fluctuations (peaks and troughs) compared to the "Downward" movement.

In "Upward" movement, the signals range widely (up to ±120 μV), while in "Downward" movement, the fluctuations are much smaller (around ±15 μV).

The "Upward" movement involves stronger neural activity, likely due to the increased cognitive and motor control demands associated with the action.

The "Downward" movement shows more subdued neural responses, indicating relatively less effort or engagement during this motion.

- 3.

Consistency Across Participants:

Hence, a general rule can be formulated according to these observations in

Figure 4 as:

If the EEG signal shows larger voltage fluctuations (greater amplitude and range), it likely corresponds to a movement that requires greater effort or neural activation, such as "Upward" movement.

If the EEG signal exhibits smaller voltage fluctuations (lower amplitude and range), it corresponds to a movement that requires less effort, such as "Downward" movement.

1.1. Limitations of the Study

While the initial findings of this study demonstrate the feasibility of using raw EEG signals for controlling UAV movements, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study focused solely on capturing unprocessed EEG data, which inherently includes noise and artifacts from sources such as muscle movements, eye blinks, and environmental interference. This noise can obscure relevant brainwave patterns, potentially affecting the reliability of the data. Although future steps involve the application of pre-processing techniques like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to address these issues, the current findings are limited to the raw signal quality.

Another limitation is the sample size, which consisted of 5 participants. While this was sufficient to demonstrate initial feasibility, a larger and more diverse participant pool would be necessary to generalize the results across different demographics. Variability in EEG signal patterns between individuals can also pose challenges, as differences in brainwave activity may affect the model’s ability to generalize and accurately classify movements across users. Moreover, the participants demographics as seen in

Table 1., can have an overall influence on the participants EEG signals and response curves. Lastly, the study's scope was limited to two simple commands ("upward" and "downward"), which restricts the system’s application to basic UAV control. Expanding the range of commands will be crucial for real-world scenarios that require more complex UAV manoeuvres. However, the study will initially continue to focus on improving the upward and downward commands, and only after successful implementation of these will other control inputs be added, such as six degrees of freedom (6 DOF) commands—yaw, pitch, roll, and additional movement controls.

1.1. Further work

Building on the initial feasibility study, future work will focus on several key areas. The first priority is to pre-process and filter the raw EEG data using techniques such as band-pass filtering, Independent Component Analysis (ICA), and feature extraction of specific EEG frequency bands like beta and theta waves. Band-pass filtering helps isolate the relevant frequency bands by removing unwanted noise, while ICA has been proven effective in separating neural signals from artifacts such as muscle activity and eye blinks, as shown by [

6]. Feature extraction focusing on beta and theta waves is critical for understanding motor control and cognitive engagement. For example, recent research by [

5] demonstrated the significance of beta and theta bands in distinguishing motor imagery patterns, which is vital for accurate classification in brain-computer interface applications [

7],[

8].

1.1. Scientific Significance

The findings of this study are significant in both current and future contexts. At present, the ability to capture raw EEG signals and observe distinct patterns associated with specific motor commands suggests that neural interfaces could be effectively integrated with UAV systems. Although the initial data is unrefined, the study demonstrates a practical approach for bridging human cognitive functions with IoT devices, offering a foundation for more advanced neural control systems.

Looking ahead, the continued development of this technology could revolutionize how humans interact with machines in various industries. In the context of UAV control, the successful integration of brain-computer interfaces can lead to hands-free operation, enabling users to perform complex tasks without the limitations of traditional manual controls. This has practical implications in fields such as search-and-rescue operations, where fast, precise, and intuitive control is critical, or in medical scenarios where surgeons could control tools with precision through thought alone. Beyond these, the approach can also be adapted for applications in robotics, smart homes, and industrial automation, making the human-machine interaction more seamless and efficient.

Adaptation of this approach could also be a game changer for surgery. Current trends in this field are leading to less invasive and more robotic surgeries, especially in hard-to-reach areas such as in neurosurgery [

18]. We believe that the use of BCI and IoT technologies at the initial stage will help simplify the surgeon’s interaction with augmented reality devices and, as a result, reduce the time of surgery. And then the use of more sophisticated and precise BCI will be a core factor in the development of robot-assisted, minimally invasive, single-stage surgery.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide a promising foundation for translating EEG signals into UAV control commands. As a next step, the captured data will undergo analog-to-digital processing, including filtering and noise reduction, to enhance signal quality for the application of machine learning algorithms. These methods aim to improve accuracy in command recognition, supporting the development of reliable, hands-free control systems. Future research will focus on refining signal processing techniques and expanding command complexity, advancing the potential of EEG-based interfaces for practical applications in fields requiring precise, intuitive control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.G. and I.I.V.; methodology, M.A.G., I.I.V. and A.A; data acquisitions and measurements M.A.G.; validation, M.A.G and A.M.; writing and original draft preparation, M.A.G.; review and editing, M.A.G., A.M. and G.R.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Science Foundation (Project “Goszadanie”, FSEE-2024-0011).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects/participants involved in the study. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki. Authors declare that in view of the retrospective nature of the study, all the collected data were anonymized, and no information is linked or linkable to a specific person.

Data Availability Statement

Brain Signals were extracted and exported using the licensed version of Emotiv Epoc X headset’s related programs such as EmotivBCI and EmotivPro. The EEG data of the study will be available anonymized upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ma, T., Chan, F., & Sun, H. (2021). Brain-computer interface controlled drone: Research, challenges, and future. International Journal of Unmanned Systems Engineering, 9(3), 125-132.

- Wolpaw, J. R., & Wolpaw, E. W. (2020). Brain-computer interfaces: Principles and practice. Oxford University Press.

- Jafri, R., & Khan, M. S. (2019). UAV-based BCI systems for disaster management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 35, 101066.

- Rashed, E. A., Inoue, T., & Sato, M. (2020). Artifact Removal from EEG Signals Using Independent Component Analysis: A Review. Neuroinformatics, 18(2), 135-152.

- Lee, J., Kim, S., & Park, H. (2022). Analyzing Beta and Theta EEG Patterns for Enhanced Motor Imagery Recognition in Brain-Computer Interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 30(5), 678-686.

- Zhang, Y., Li, W., & Chen, H. (2024). Enhancing EEG Signal Quality Using Independent Component Analysis for Brain-Computer Interface Applications. Journal of Neural Engineering, 21(1), 012345.

- Nicolas-Alonso, L. F., & Gomez-Gil, J. (2020). Brain computer interfaces, a review. Sensors, 12(2), 1211-1279. [CrossRef]

- Tan, G. H., & Lim, C. L. (2023). EEG Preprocessing and Feature Extraction Techniques for Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 145-159.

- Emotiv. (2022). EmotivBCI: Real-time brain-computer interface software. Available online: https://www.emotiv.com.

- Emotiv. (2023). EmotivPro: Advanced EEG data acquisition and analysis. Available online: https://www.emotiv.com.

- Smith, A. B., Johnson, L., & Williams, P. (2022). Alpha oscillations and motor readiness. Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(3), 188-195.

- Jones, D., & Miller, K. (2023). Beta-band activity in motor planning and execution. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 112-125.

- Lee, S. H., Kim, H. J., & Park, J. (2021). High beta oscillations during complex motor tasks. Journal of Motor Behavior, 53(2), 89-98.

- Garcia, M., & Patel, R. (2022). Gamma oscillations and their role in cognitive function. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 99(4), 432-440.

- Huang, T., Li, X., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The role of alpha and beta oscillations in motor control: A review. Neurobiology of Movement, 15(1), 23-35.

- Degirmenci, M., Yildirim, O., & Balaban, E. (2024). EEG-based finger movement classification with intrinsic time-scale decomposition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

- Lopez, M., Thibault, S., & Faubert, J. (2020). Individual differences in brain oscillations reflect variability in response to motor imagery tasks. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 576241.

- Fayed I, Smit RD, Vinjamuri S, Kang K, Sathe A, Sharan A, Wu C. Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Asleep Single-Stage Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery: Operative Technique and Systematic Review. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2024 Apr 1;26(4):363-371. Epub 2023 Oct 27. PMID: 37888994. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).