1. Introduction

The mechanical integrity of a cell is essential to its function and the tissues and organ systems that it supports [

1,

2]. Cell volume stabilization is a fundamental function to preserve the mechanical integrity of a cell [

3]. Cell volume stabilization along time is based on the balance among forces acting on the cell membrane which emanate from electrochemical and fluid-mechanical mechanisms [

4]. The experimental characterization of force equilibrium at the nanoscale level is a highly complex task because of the difficulty of performing measurements

in vivo (see [

5]), and the presence of two regimes of mechanical behavior in living cells, at short and long time scales (see [

6]).

Based on these considerations, we address in this article the theoretical study of cell volume dynamics and apply the formulation to the process of production of aqueous humor (AH) in the eye. AH is a slowly moving fluid that is continuously produced by the ciliary body of the eye, whose main function is to keep the anterior segment of the eye clean from metabolic wastes and to preserve the spherical shape of the eyeball by establishing the intraocular pressure (IOP) (see [

7,

8,

9,

10]).

Keeping IOP within normal levels (10 to 21 mmHg) is central to prevent the occurrence and progression of neurodegenerative diseases of the retina such as glaucoma [

11,

12,

13]. This opens up the question to understand the biophysical mechanisms that determine the value of IOP and, consequently, the causes of the pathology, and to devise effective therapies for its cure. In this respect, the development of a mathematical model and of a computational virtual laboratory (CVL) for the simulation of AH production has been object of investigation in recent years (see [

14,

15,

16,

17]).

In this article, we propose a theoretical formulation based on homogeneous mixtures including neutral and charged solutes (see [

18], Chapter 13) and utilizing a model reduction procedure from three spatial dimensions to zero spatial dimensions. The model resulting from reduction is a coupled system of highly stiff nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODE) which are solved using the

-method and the

Matlab function

ode15s. Simulation tests are run to characterize the values of model parameters at baseline conditions in AH production. The model is subsequently used to investigate the relative importance of (a) impermeant charged proteins; (b) sodium-potassium pump; and (c) carbonic anhydrase in the AH production process. Results suggest that (a) and (b) play a role whereas (c) does not have a significant weight, at least for low CO

2 values.

2. Materials and Methods

In

Section 2.1 we describe the geometrical representation of the cell volume and surface; in

Section 2.2 we describe the heterogeneous structure of the cell membrane; in

Section 2.3 we provide a conceptual scheme of transport of water and solute across the cell membrane. In

Section 2.4 we introduce a continuum model of the cell based on the theory of mixtures, to describe the spatial and temporal response of the cell volume to the concomitant action of fluid and electrochemical forces. In

Section 2.5 we derive a reduced-order model of the cell volume that comprises ordinary differential and algebraic equations. Finally, in

Section 2.6 and

Section 2.7 we describe the compact form of the reduced-order model and its numerical approximation, respectively. In Appendices

Appendix A and

Appendix B, we provide the expressions of the fluid velocity, molar flux densities and net production rates that are involved in cellular metabolism.

2.1. Geometrical Description of the Cell

Let

denote the time variable (units: s). We denote by

the three-dimensional (3D) body representing the cell at time

t and

the volume of the cell at time

t, such that

is the value of the cell volume at time

,

being the cell radius in the initial (undeformed) configuration (units:

m). From the point of view of Continuum Mechanics the body is a deformable, electrically charged, homogeneous mixture comprising a fluid constituent,

moving charged solute constituents (ions) and

moving neutral solute constituents (see [

18], Chapter 13). The cell volume contains also impermeant charged proteins whose chemical valency and molar density is such that electroneutrality holds in ionic homeostasis conditions (see [

3] and [

19]). The boundary of

is denoted by

and

is the outward unit normal vector on

. The surface of the cell at time

t is denoted by

, such that

is the value of the cell surface at time

. In the remainder of the article, we denote by

the spatial coordinate vector of any point of the cell with respect to a fixed system of reference. We also refer to the interior of

as the intracellular region (shortly,

), to the exterior of

as the extracellular region (shortly,

) and to the surface of

as the membrane (shortly,

m).

Assumption 1. We assume that cell deformation occurs only in the radial direction and that it does not depend on the position on the cell surface.

Assumption 2. We assume that the electric potential, solute concentrations and fluid pressure in the extracellular region are given functions of space and time.

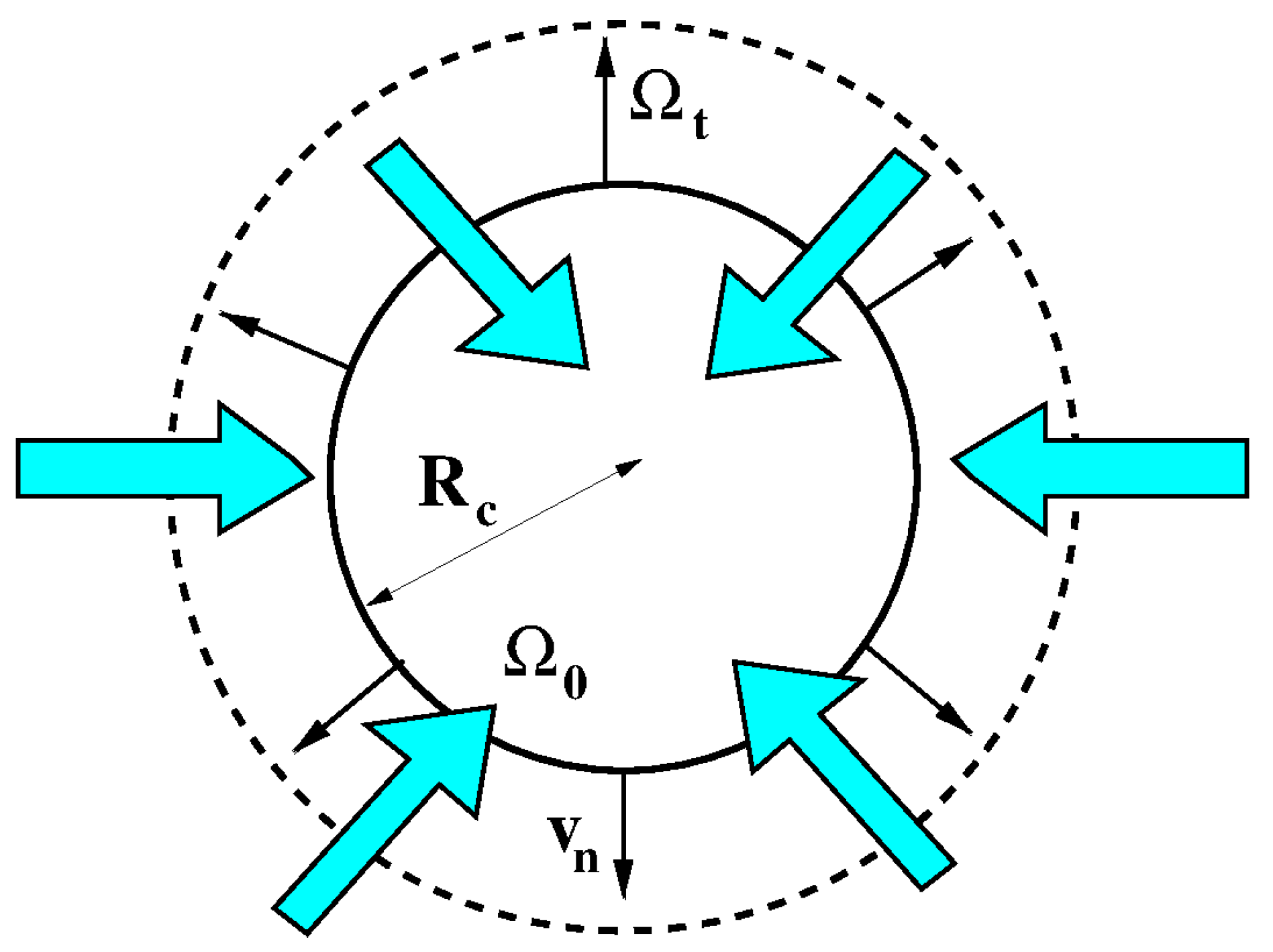

Figure 1 illustrates in solid line and dashed line the initial and deformed configurations of the cell, respectively. In agreement with Assumption 1, both configurations are spherical.

2.2. Porous and Lipid Structure of the Cell Membrane

The intra and extracellular regions are separated by a 3D membrane whose thickness

is such that the ratio

is

. In the limit

, the geometrical representation of the 3D membrane degenerates into the two-dimensional (2D) manifold

. The membrane surface can be represented as an heterogeneous porous medium whose solid constituent is lipid material. The lipid surface is impermeable to water and solutes whereas the pore surface allows the exchange of fluid and solutes between intra and extracellular regions. The pore surface contains a variety of membrane proteins, denoted by

. Each membrane protein

is characterized by a dimensionless function

, henceforth referred to as surface fraction, defined as

where

is the total area occupied by the protein

at time

t.

Assumption 3.

Let . We assume that

Equation (1b) implies that

The first type of membrane protein that we introduce in this article is the aquaporin (AQP), which is a specialized protein for rapid transmembrane water exchange between intracellular and extracellular regions (see [

20,

21,

22]). The quantity

represents the AQP surface fraction. Other membrane proteins on the cell surface comprise carrier proteins, which permit neutral solute exchange through the cell membrane by the mechanism of facilitated diffusion (see [

23] and [

24]), and ion channels, ion exchangers and ion pumps, which permit charged solute exchange through the cell membrane (see [

25]). The total surface fractions for each considered membrane protein are defined as:

in such a way that the total pore surface fraction is

The remainder of the cell surface is occupied by the lipid constituent of the membrane, whose surface fraction is

Assumption (3) implies that the membrane protein surface fractions in (2) do not depend on time, and that also the lipid surface fraction does not depend on time because of (

4).

2.3. Water and Solute Transport Across the Cell Membrane

In this section we provide a conceptual scheme of transport of water and solute across the cell membrane and we refer to [

21] and [

26] for more details about the subject.

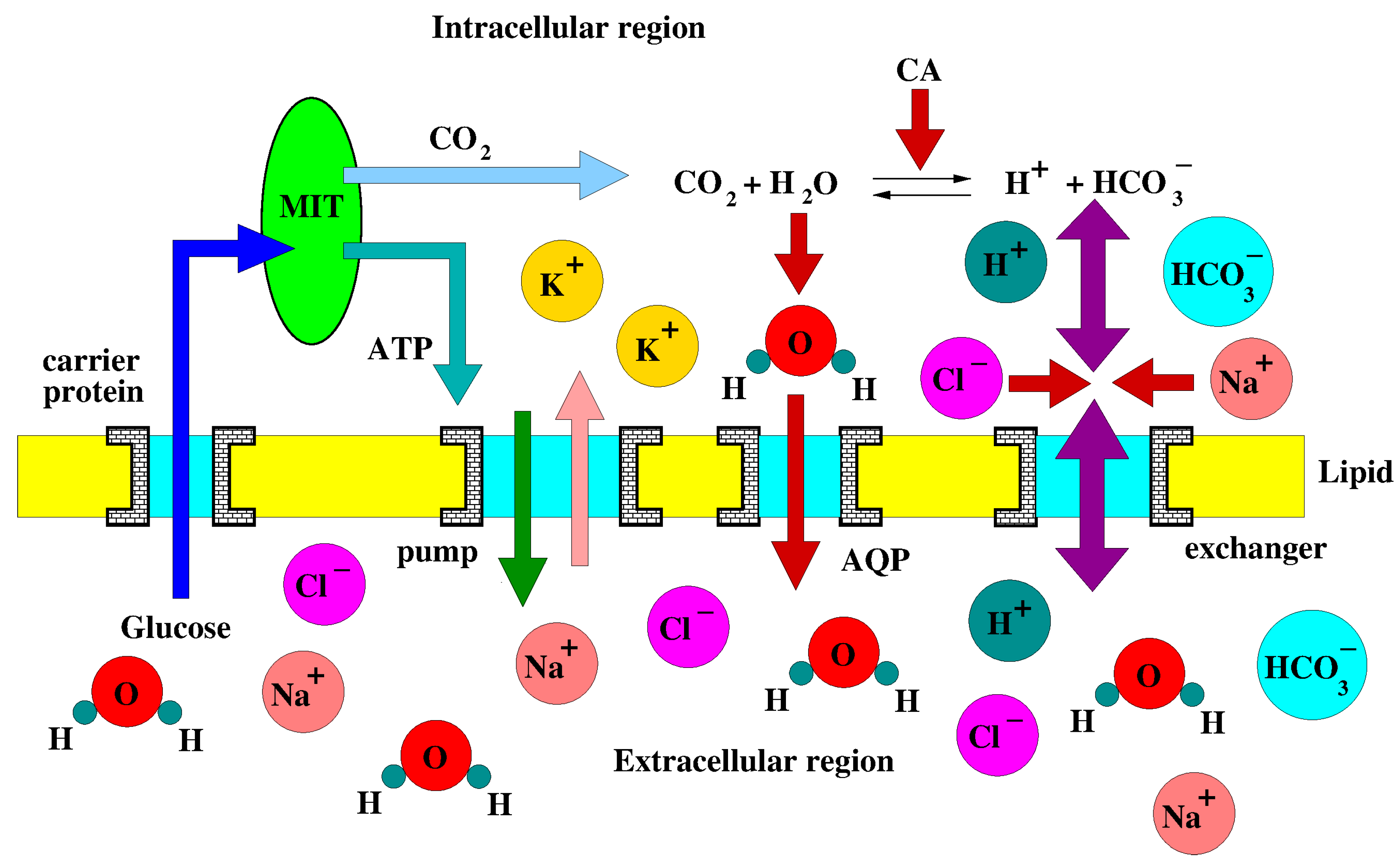

Figure 2 illustrates a schematic representation of a zoomed view of the cell membrane and of the intra and extracellular regions. The scheme shows water molecules and solutes (neutral and charged) in motion across the membrane.

Assumption 4. Based on the scheme in Figure 2 we make the following assumptions:

-

A1.

Water is transported across the membrane, in a selective manner, via aquaporins;

-

A2.

Water and solutes are co-transported across the membrane via ionic channels and carrier proteins;

-

A3.

Water velocity inside ionic channels and carrier proteins is the same as water velocity inside aquaporins.

2.4. Continuum-Based Model of the Cell

This section is structured in four subsections devoted to fluid motion, neutral and charged solutes, and electric potential.

2.4.1. Fluid Motion

Assumption 5. We assume that water flow is slow and inertial forces can be neglected with respect to the viscous effects.

According to Assumption 5, the motion of water flow across the cell membrane can be described by the linear Stokes equation system (see [

18], Section 10.5.1):

where

(units:

) and

p (units:

) are the fluid velocity and pressure inside the aquaporin, respectively,

is the fluid stress tensor (units:

),

is the force density acting on the fluid (units:

),

is the fluid dynamic viscosity (units:

) and

is the symmetric gradient operator.

Equation (

5a) expresses mass conservation in local form; equation (5b) expresses linear momentum balance in local form; equation (5c) is the constitutive law for a Newtonian fluid.

2.4.2. Neutral solutes motion

We denote by

the set of neutral solutes, with

. Each solute

is described by its number density

and molar density

(units:

). The advection-diffusion model is adopted to represent the motion of neutral solutes across the cell membrane (see [

18], Chapter 12):

Equations (6a) express mass balance in local form for each solute

. The vector

is the molar flux density of solute

(units:

) accounting for a passive advective contribution due to water motion inside the carrier protein channel (see Assumption 4-A2), and a diffusive contribution expressed by Fick’s law in which

is the diffusion coefficient of solute

(units:

). The scalar functions

and

represent production and consumption rates of

(units:

).

2.4.3. Charged solutes motion

We denote by

the set of charged solutes (ions) with

. Each ion

is described by its number density

, molar density

, charge number

, diffusion coefficient

and electric mobility

(units:

). The number and molar densities are related by the equation

(units:

), where

is Avogadro’s constant. The diffusion coefficient and the electric mobility are proportional through Einstein’s relation

where

is the thermal voltage (units:

V),

,

T and

q denoting Boltzmann’s constant, absolute temperature and electron charge, respectively. The Nernst-Planck (NP) model is adopted to represent ion transport and exchange across the cell membrane (see [

18], Chapter 13):

Equations (8a) express mass balance in local form for each ion

. The vector

is the molar flux density of ion

, accounting for a passive ion molar flux density

and an active ion molar flux density

. The vector

is the velocity-extended NP equation for ion electrodiffusion and accounts for a passive advective contribution and a diffusive contribution expressed by Fick’s law (see [

18], Chapter 13). The vector field

is the generalized drift velocity of ion

due to water motion inside the ion channel (see Assumption 4-A2) and Faraday’s law under quasi-static approximation (see [

18], Chapter 14)

where

and

are the electric field (units:

) and electric potential (units: V), respectively.

The vector expresses passive ion exchange mediated by transporters and co-transporters. The scalar functions and represent production and consumption rates of .

2.4.4. Electric potential

The spatial and temporal distribution of the electric potential

across the cell membrane is described by the following differential system:

where

is the dielectric permittivity of the cell membrane lipid layer (units:

) and

F is Faraday’s constant (units:

). Equation (9a) is a consequence of Maxwell’s equations (see [

27] and [

18], Chapter 4) and expresses the continuity of the total electric current density

(units:

), given by the sum of the total conduction current density

and the displacement current density

, in which the electric field

is expressed as a function of the electric potential

via equation (8f).

2.5. Cell Reduced-Order Model

This section is structured in five subsections devoted to the derivation of the reduced-order model for cell surface normal velocity, cell volume, neutral and charged solute molar densities and electric potential.

2.5.1. Time evolution of normal velocity across a single AQP

We make the following assumption on the geometry of the AQP shown in

Figure 2.

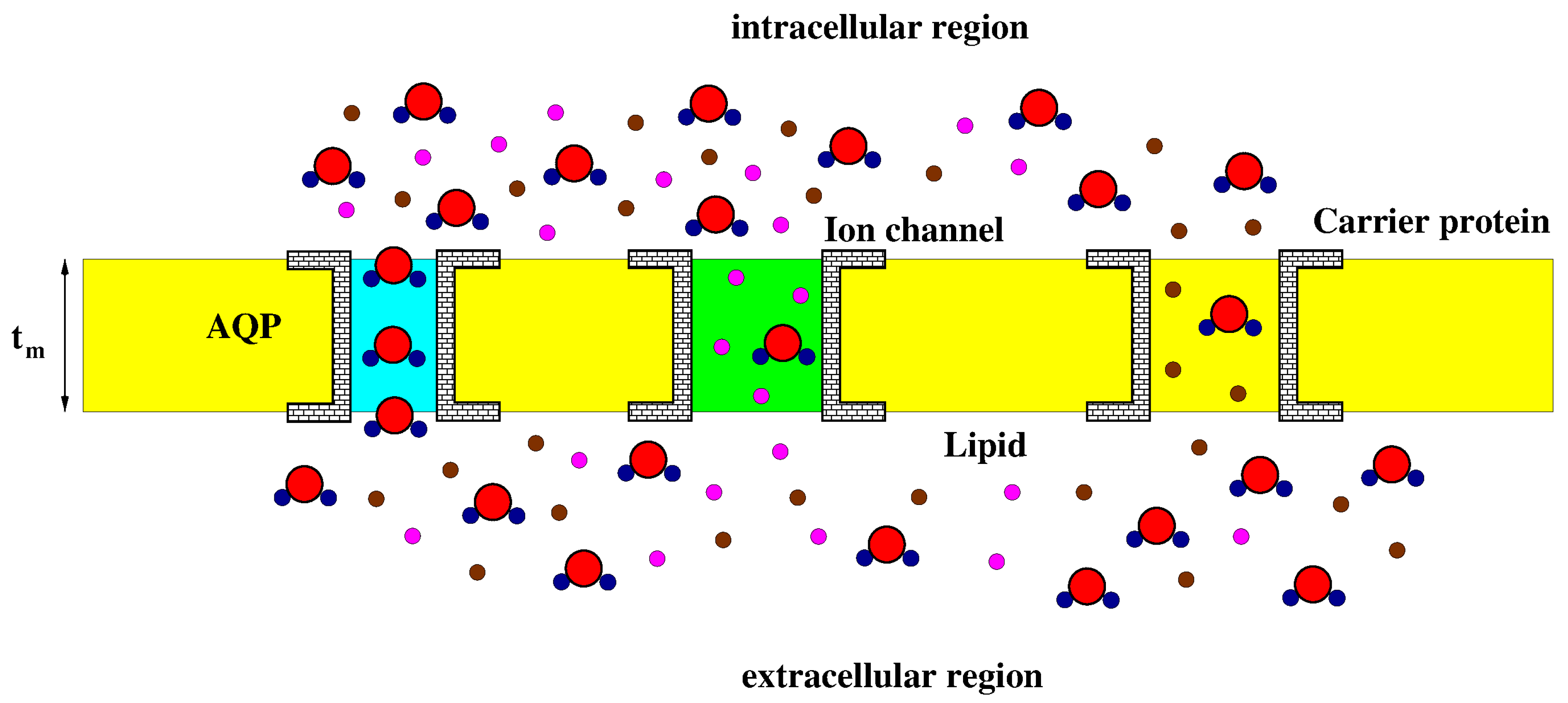

Assumption 6. The AQP is geometrically represented as a cylinder with radius and axial length as depicted in Figure 3.

Moreover,

Assumption 7. We assume that:

-

1.

the fluid velocity has only the axial component ;

-

2.

, with and ;

-

3.

(Poiseuille flow);

-

4.

the force density has only the axial component ;

-

5.

, with and .

Inserting Assumptions A7 into equations (5) we obtain the following expression of the normal fluid velocity inside the pore channel of the AQP

Integrating (10a) we get

For any function

, we define the transmembrane difference operator

Setting

in (10b) and applying the definition (10c) to the variables

p and

, we obtain

where

is the hydraulic conductivity of the membrane (units:

) and

is the total osmo-oncotic pressure,

C being an arbitrary integration constant. Relation (10d) is Starling’s equation [

28] and represents the mathematical expression of the normal fluid velocity across the single aquaporin.

2.5.2. Time Evolution of Cell Surface Normal Velocity

In order to determine the motion of the whole cell surface, we need to define an average normal fluid velocity to represent the collective contribution of the AQPs. To this purpose, we denote by

the surface density of aquaporins, defined as the number

of AQPs per square meter, and by

the total surface area occupied by the AQPs. Using Assumption 3, we obtain

Let us introduce the total water volumetric flow rate across the cell surface (units:

)

and the average normal fluid velocity across the cell surface

where

is given by (11a) and

is given by (10d).

The pore fluid velocity

is typically quite large (even thousands of

, see [

29]) to favor a fast transmembrane exchange of water molecules. The average normal fluid velocity

, instead, is considerably smaller (less that

, see [

30]). For this reason, in the remainder of the article, we introduce the following definition.

Definition 1.

Let us denote by the cell surface normal velocity. We set

where is defined in (10d).

2.5.3. Time evolution of cell volume

The time evolution of

is described by the cell mass balance equation in integral form (see [

18], Chapter 6)

where

is the mass density of water (units:

),

is the mass of the cell at time

t (units:

), and

is the intracellular water mass density net production rate,

and

being water mass density production and consumption rates, respectively (units:

).

Assumption 8.

We assume that:

where and represent the time-dependent intracellular water mass density production and consumption rates, and the shape function Φ is such that

Using Tr.1 in Assumptions A4, using Definitions 1 and A8 into the right-hand side of (13), and noting that

, with

, we obtain the following reduced-order model of cell volume motion:

where

is given by (10d) and

is the water volume net production rate (units:

), having set

and

for every

.

2.5.4. Time Evolution of Neutral Solutes

The time evolution of neutral solute molar density is described by the mass balance equation in integral form

where

is the normal molar flux density of

over the cell surface

, and

is the net production rate of intracellular solute

,

and

being production and consumption rates, respectively (units:

).

Assumption 9.

We assume that:

where and are time-dependent intracellular neutral solute molar densities and normal molar flux densities over the cell surface, respectively, and the shape function is such that

where is the surface fraction of the carrier protein that allows the transmembrane exchange of the neutral solute β. We also assume that equations similar to (15) apply to and .

Using Assumptions A9 in (

13c) we obtain the following reduced-order model for each neutral solute molar density:

where

is the initial value of the intracellular neutral solute molar density,

, and

is the net production rate of solute

(units:

).

2.5.5. Time evolution of charged solutes

The time evolution of charged solute molar density is described by the mass balance equation in integral form

where

is the normal molar flux density of

over the cell surface

, and

is the net production rate of intracellular ion

,

and

being production and consumption rates, respectively (units:

).

Assumption 10.

We assume that:

where is the time-dependent intracellular molar density of ion , the functions and are time-dependent normal molar flux densities over the cell surface representing passive ion transport and exchange, respectively, the function is a time-dependent normal molar flux density over the cell surface representing ion exchange through active pumps, and the shape functions , and are such that:

where , and are the surface fractions of the membrane protein associated with passive transport, passive exchange and active pump-mediated exchange of ion α, respectively. We also assume that equations similar to (8) apply to and .

Using Assumptions A10 in (21) we obtain the following reduced-order model for each charged solute molar density:

where

is the initial value of the intracellular charged solute molar density,

, and

is the net production rate of ion

(units:

).

2.5.6. Time evolution of membrane potential

For any

, the membrane potential is defined as

The time evolution of the membrane potential is described by the charge balance equation in integral form

where

and

are the normal derivative of the electric potential and the normal total conduction current density over the cell surface

, respectively.

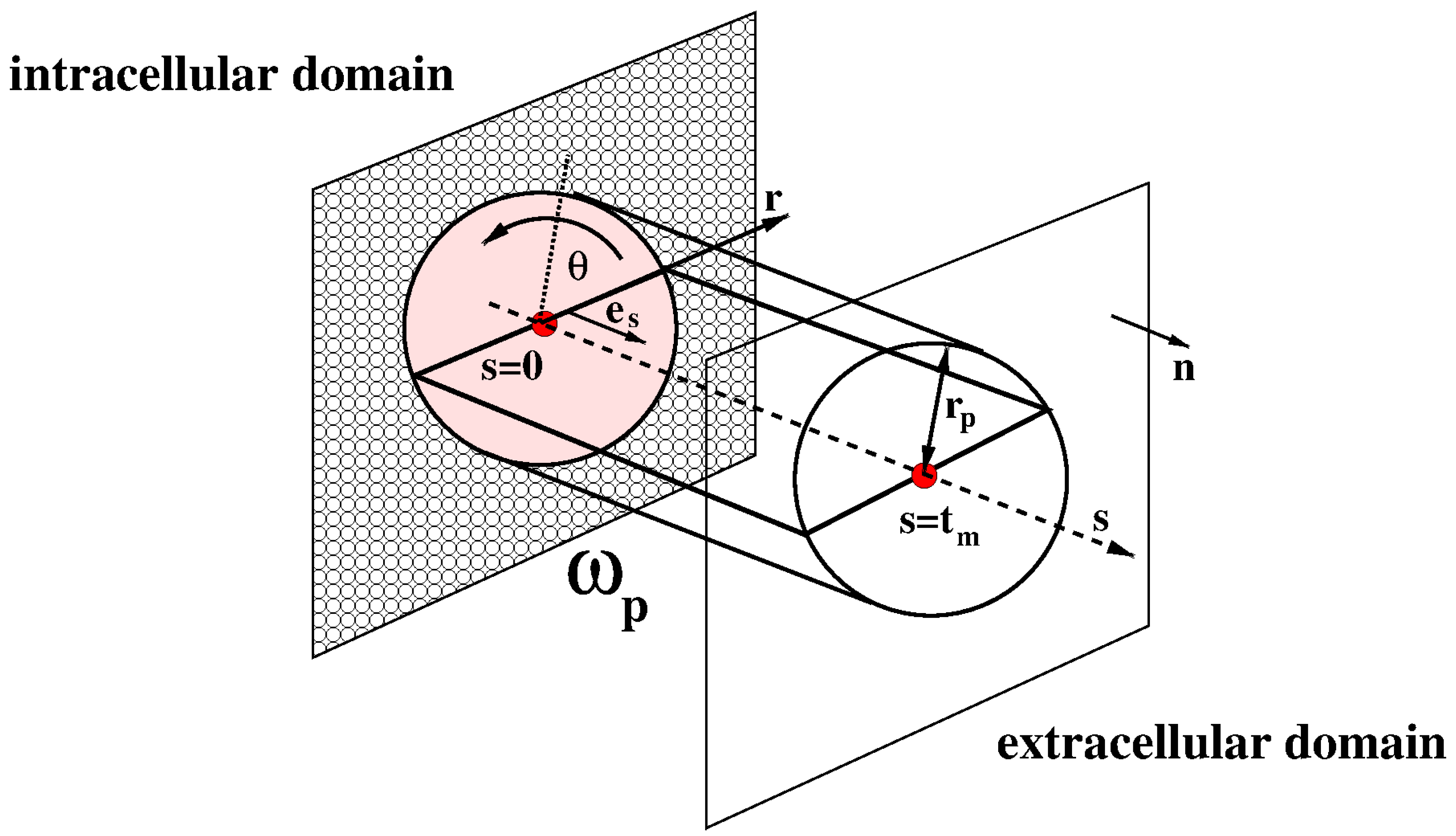

Assumption 11. We assume that the electric potential is a piecewise linear continuous function across the cell membrane thickness (see Figure 4).

Using Assumption 11 into the left-hand side of (26), we get

where

is the cell specific capacitance (units:

). The right-hand side of (26) is given by the following expression

where

is the total conduction current flowing across the cell membrane at time

t (units: A), defined as

Replacing (27) and (29) into (26) we obtain the following reduced-order model for the membrane potential:

where

is the normal total conduction current density over the cell surface defined in (24b), and

is the initial value of the membrane potential.

2.6. Compact Form of the Cell Reduced-Order Model

Let us introduce the vector of dependent variables:

where:

are the column vectors containing the time values of neutral and charged solute molar densities.

Let us define the vector of source terms:

where

and

are column vectors of size

and

, respectively, containing the time values of neutral and charged solute normal molar flux densities, whereas

(and

),

(and

) are column vectors of size

and

, respectively, containing the time values of intracellular neutral and charged solute production (and consumption) terms.

Finally, let us define the column vector containing the initial condition of the model:

where

and

are column vectors of size

and

, respectively, which contain the values of the initial conditions for the intracellular neutral and charged solute molar densities.

The equation system constituting the model of cell volume motion can be written in compact form as:

System (37) comprises differential equations and algebraic equations, represented by the constitutive laws for the normal molar flux densities of neutral and charged solutes and for the production and consumption rates of water and solutes. The expressions of the normal fluid velocity on the cell surface and normal molar flux densities are provided in

Appendix A whereas the expressions of production and consumption rates are provided in

Appendix B.

2.7. Numerical Approximation

The mathematical model proposed in this article is implemented within a Computational Virtual Laboratory (CVL) for the simulation of cell volume motion.

The

-method (see [

18], Chapeter 3) and the

Matlab tool

ode suite are used for the numerical approximation of (37) (see [

31]). In the case of

-method, the values

and

are utilized,

corresponding to the Backward Euler (BE) method and

corresponding to the Crank Nicolson (CN) method. In the case of the

Matlab tool

ode suite, the functions

ode15s or

ode23tb are utilized because they are specifically tailored to solve stiff problems like the one object of the present article (see [

32], Chapeter 11). The function

ode15s is endowed with a variable-order Backward Differentiation Formulae (BDF) method, whereas the function

ode23tb uses the trapezoidal rule coupled with a BDF of order 3.

The CVL allows the user to consider physical situations of increasing complexity, starting from the solution of the sole Cauchy problem (16) in which the fluid velocity is a given function of time and the production and consumption terms are functions of time and cell volume. Simulation complexity can be increased by adding charged and neutral solutes, intracellular reactions and transmembrane ion exchange mechanisms, as well as the presence of impermeant protein charges in both intra and extracellular regions. This hierarchy of scenarios is investigated in

Section 3 where the accuracy and reliability of model predictions is verified against analytical solutions and available data.

4. Discussion

Cell volume stabilization is a fundamental function to preserve the mechanical integrity of a cell [

3]. Keeping the cell volume constant along time is the result of the balance among forces acting on the cell membrane from both intra and extracellular sides, which emanate from electrochemical and fluid-mechanical mechanisms [

4]. The experimental characterization of force equilibrium at the scale of the cell membrane is a nontrivial task, on the one hand, because of the difficulty of performing measurements

in vivo (see [

5]), and, on the other hand, the presence of two distinct regimes of mechanical behavior in living cells. In fact, a combination of experimentation and theoretical analysis shows that living mammalian cytoplasm behaves as an equilibrium material at short time scales whereas it behaves as an out-of-equilibrium material at long time scales [

6].

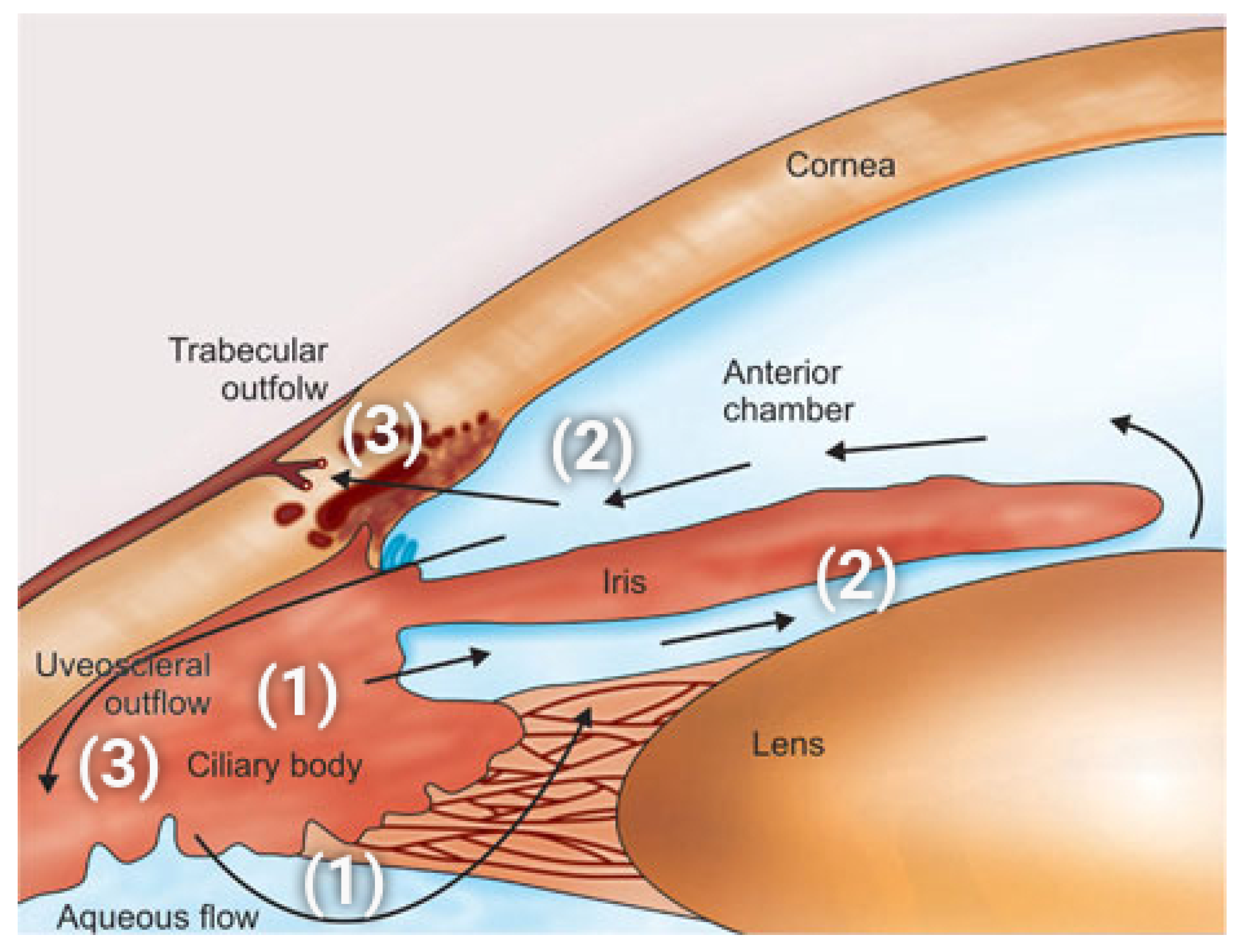

Based on these considerations, we address in this article the theoretical study of cell volume dynamics with the aim of applying the formulation to the process of production of aqueous humor (AH) in the eye. AH is a slowly moving fluid that is (1) continuously produced by the ciliary body of the eye; (2) flows from the posterior into the anterior chamber of the eye; (3) is drained out of the eye throughout two main outflow pathways (see [

7,

8,

9,

10]). The sequence: (1) AH production; (2) AH flow; and (3) AH outflow is schematically represented in

Figure 11.

The main function of AH is to keep the anterior segment of the eye clean from the metabolic waste of the surrounding tissues and to preserve the spherical shape of the eyeball by establishing the intraocular pressure (IOP) as the value of AH fluid pressure in correspondance of which the volumetric flow rate of AH that is produced by the ciliary body equals the volumetric flow rate of AH that is drained out by the outflow pathways in the anterior segment of the eye (see [

35]). Successful control of the IOP within normal levels (10 to 21 mmHg) is central to prevent the occurrence and progression of neurodegenerative diseases of the retina such as glaucoma [

11,

12,

13]. Therefore, unraveling the biophysical mechanisms that concur to determine the value of IOP may be of significant help to understand the causes of glaucoma and to develop effective therapies for its cure.

The development of a mathematical model and of a CVL for the simulation of the process of production, flow and outflow of AH has been subject of investigation in recent years (see [

14,

15,

16,

17]). Our proposed formulation is characterized by the following features: (F.1) it is based on the use of homogeneous mixtures including neutral and charged solutes (see [

18], Chapter 13); (F.2) it is defined at the level of the single cell; and (F.3) it utilizes a model reduction procedure from three spatial dimensions to zero spatial dimensions. Feature (F.1) confers a solid theoretical foundation to the proposed model. Features (F.2) and (F.3) make the model structure simple and the computational schemes fast and suitable for adoption in a clinical environment. The model is a consistent generalization of previous approaches [

3,

4] as it shares with them the same conceptual simplifying assumption of working at the level of the single cell. This assumption is applied here to evaluate the collective behaviour of the cells in the CE of the eye in the process of production of AH.

The model that we propose in these pages has also limitations: (L.1) the dependence of all the variables from the spatial coordinate is neglected; (L.2) several important transmembrane mechanisms regulating solute exchange are not considered in the simulations; (L.3) statistical variability of parameters is not accounted for. Limitation (L.1) is a consequence of the use of the 3D-to-0D reduction procedure. Limitation (L.2) is a choice to prevent proliferation of model parameters thereby rendering easier the analysis of simulation predictions. Limitation (L.3) is a consequence of the choice of using a mechanistic (continuum-based) approach. We intend to remove all of these limitations in future extensions of the formulation considered in the present article.

4.1. The Impact of the Oncotic Pressure Due to the Impermeant Charge

In this simulation we solve system (37) in the time interval

with the same set of parameters as in

Section 3.2, except the reflection coefficient

which is set equal to

(

Matlab vector notation). By doing so, the weight of the contribution of the oncotic pressure difference (A3h) to the total osmo-oncotic pressure difference (A3k) increases progressively from 0% (

) to 100 % (

), thereby allowing us to investigate the impact of the oncotic pressure difference on AH simulation.

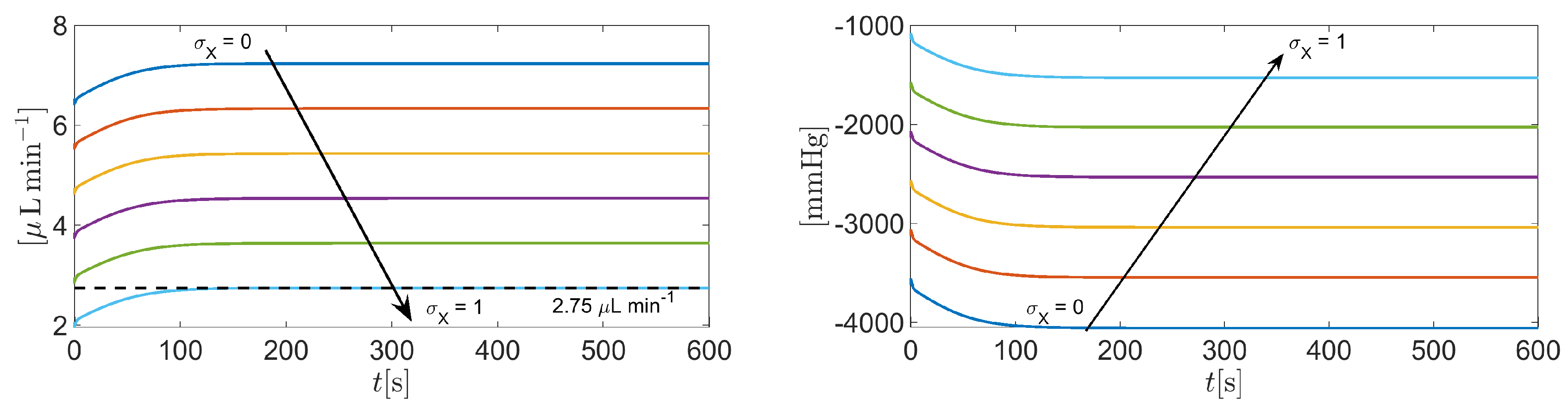

Figure 12 (left panel) illustrates the time evolution of the total volumetric flow rate

as a function of time

t in the interval

. Results indicate that the smaller

, the larger the predicted total volumetric flow rate of AH. In particular, the value of

predicted by the model that is compatible with the given intracellular and extracellular fluid pressures (20mmHg and 15 mmHg, respectively) is obtained for

. To better understand the effect of including properly the impermeant charge in AH modeling, we illustrate in

Figure 12 (right panel) the time evolution of the total osmo-oncotic pressure difference

in the interval

. We see that the magnitude of

largely exceeds the contribution from hydrostatic pressure difference (equal to

) for every value of

. Moreover, for every

the oncotic pressure difference

is always positive whereas the total osmotic pressure difference

is always negative, so that, as

increases, the magnitude of the total osmo-oncotic pressure difference decreases, to reach the value of

.

4.2. The impact of the Na+/K+ ATPase

In this simulation we solve system (37) in the time interval

with the same set of parameters as in

Section 3.2, except the amplification coefficient

in (A10e) which is set equal to

(

Matlab vector notation). By doing so, the weight of the contribution of the sodium/potassium pump to the electrochemical balance of the cell increases progressively from 0% (

) to 100 % (

), with respect to the working conditions of

Section 3.2, thereby allowing us to investigate the impact of the Na

+/K

+ ATPase on AH simulation.

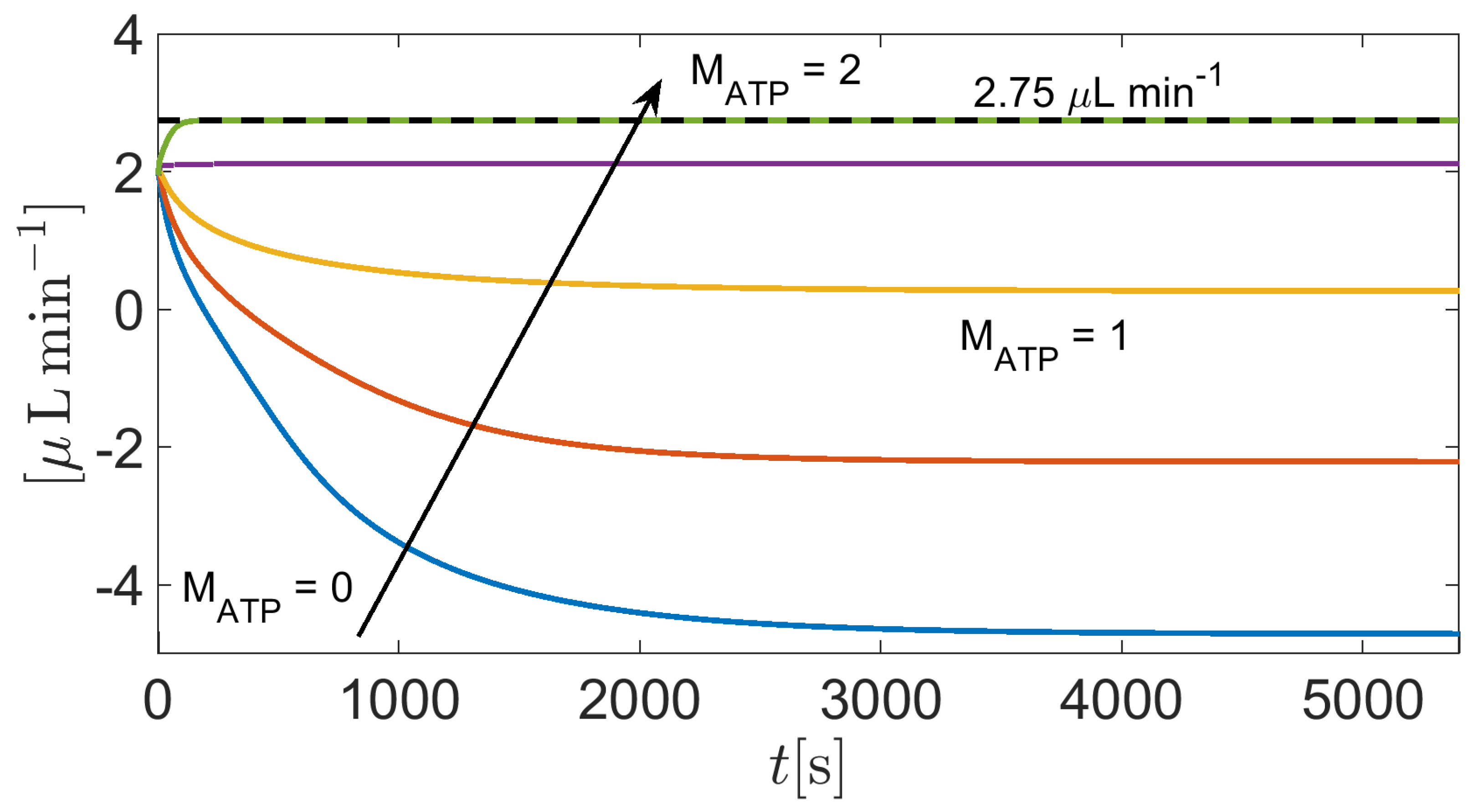

Figure 13 illustrates the time evolution of the total volumetric flow rate

as a function of time

t in the interval

. Results indicate that for

(corresponding to values of

, the predicted total volumetric flow rate of AH is negative. This means that the pump does not have enough energy to move sodium out from the cell and potassium into the cell, so that the accumulation of sodium in the cytoplasm attracts chlorine from the extracellular region, eventually leading to the inversion of fluid flow. The predicted total volumetric flow rate of AH becomes positive for

. This means that the pump does have enough energy to move sodium out of the cell and potassium into the cell, preventing chlorine accumulation in the cell cytoplasm. For increasing values of the ATP concentration (

) water flux is favored, reaching a physiological level when

.

4.3. The impact of carbonic anhydrase

In this simulation we solve system (37) in the time interval

with the same set of parameters as in

Section 3.2, except the amplification coefficient

in Equations (A7c)- (A7d) which is set equal to

(

Matlab vector notation). By doing so, the weight of the contribution of the CA enzyme to improve the reaction rate of CO

2 hydration increases progressively from 0% (

) to 100 % (

), with respect to the working conditions of

Section 3.2, thereby allowing us to investigate the impact of the CA enzyme on AH simulation.

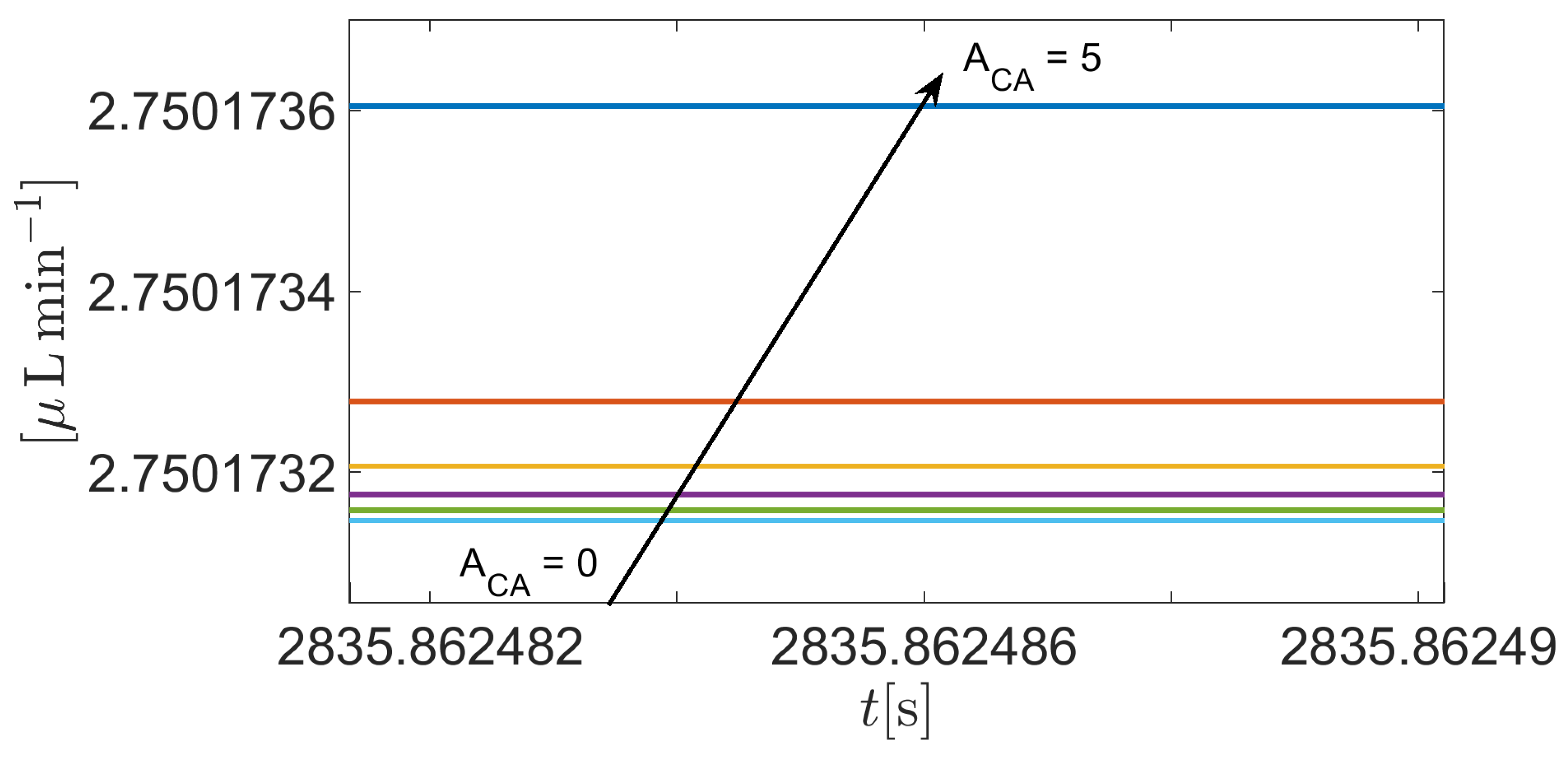

Figure 14 illustrates a zoomed detail of the time evolution of the total volumetric flow rate

as a function of time

t in the interval

. Results indicate that

is practically independent of the concentration of the CA enzyme. Further tests with higher values of the amplification parameter

do not show significant variation of the predicted value of

, this probably to be ascribed to the low value of the intracellular carbon dioxide molar density (cf.

Figure 9).

4.4. The impact of IOP

In this simulation we solve system (37) in the time interval

with the same set of parameters as in

Section 3.2, except the value of IOP which is taken in the range [15, 150]mmHg. By doing so, we want to investigate the response of the model in the case of highly hypertensive patients.

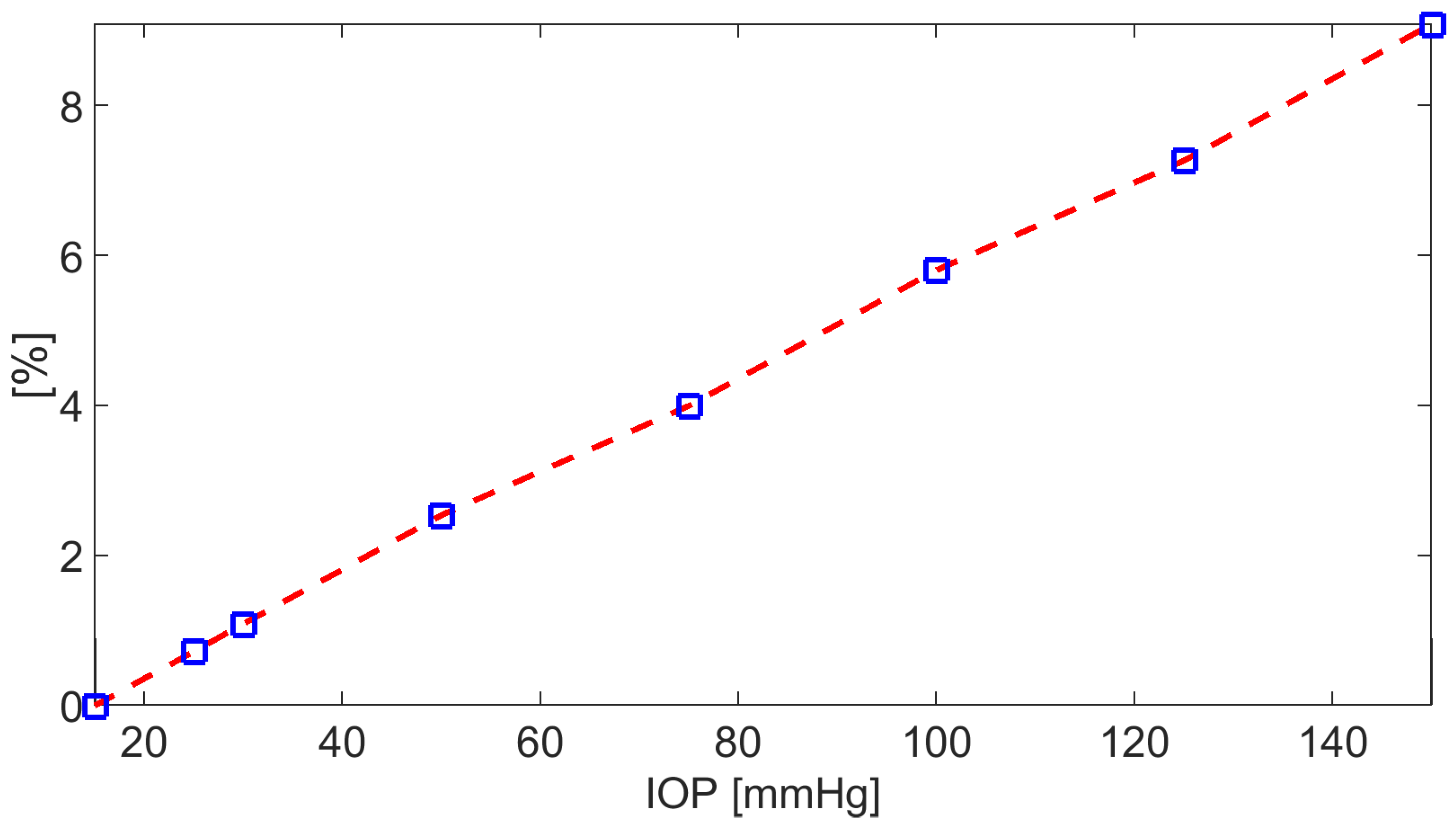

Figure 15 illustrates the % difference between

at 15mmHg and

evaluated in correspondence of IOP in the interval [15, 150]mmHg. The trend is linear with respect to IOP, which agrees with the following expression for fluid velocity

where

=20 mmHg is the intracellular fluid pressure (corresponding to the estimated fluid pressure in the CE upon assuming 25mmHg in the ciliary capillaries), and

is the total osmo-oncotic difference. Since

turns out to be negative with respect to

t, as IOP increases, we see from (47) that

diminishes, which explains the fact that also

diminishes. We notice that for IOP=30 mmHg, which is a typical value of the intraocular pressure in hypertensive individuals, the % difference between

at 15mmHg and

is 1.09% which increases to 2.54% for IOP=50 mmHg.

5. Conclusions

In this article we have proposed, analyzed and numerically investigated a reduced-order mathematical description of cellular volume homeostasis. The model accounts for intracellular reactions and transmembrane mechanisms for neutral and charged solute exchange. Hydrostatic and osmo-oncotic pressure differences are used in the context of Starling’s Law to compute the velocity of the fluid which drives the motion and radial deformation of the cell volume.

The model is implemented within the context of a CVL that is applied to the study of the process of AH production in the human eye. The scope of the simulations is to test the potential of the CVL to assess the relative quantitative importance of the biophysical mechanisms that underlie AH production, in the perspective of its use as a supporting tool to integrate and complement in vivo experiments and artificial intelligence-based methodologies for the analysis of data on a statistically significant number of patients.

The main conclusions of the model simulations suggest the importance of impermeant charged proteins and Na+/K+ ATPase on the level and direction of AH production, whereas AH production seems to be independent on CA concentration, at least for low values of CO2 concentration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and G.C.; methodology, R.S.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S., B.S. and G.A.; formal analysis, R.S., A.L. and G.G.; investigation, R.S., G.A.; resources, A.H. and G.G.; data curation, R.S. and K.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S., B.S., A.L., K.W. and A.H.; visualization, R.S.; supervision, A.H.; project administration, A.H. and G.G.; funding acquisition, A.H., A.V., B.S. and G.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Solid line: initial cell configuration. Dashed line: deformed cell configuration. The cyan arrows indicate water flow. The cell is increasing its volume (cell swelling).

Figure 1.

Solid line: initial cell configuration. Dashed line: deformed cell configuration. The cyan arrows indicate water flow. The cell is increasing its volume (cell swelling).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the structure of the cell membrane. AQP: aquaporin (cyan). The ion channel is drawn in green. Water molecules (red and dark blue), charged solutes (magenta) and neutral solutes (brown) are illustrated. The lipid constituent is drawn in yellow. The AQP is selective to water molecules whereas the ion channel permits the co-transport of ions and water.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the structure of the cell membrane. AQP: aquaporin (cyan). The ion channel is drawn in green. Water molecules (red and dark blue), charged solutes (magenta) and neutral solutes (brown) are illustrated. The lipid constituent is drawn in yellow. The AQP is selective to water molecules whereas the ion channel permits the co-transport of ions and water.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional schematic representation of an aquaporin. The cylindrical domain is the pore channel, is the membrane thickness and is the aquaporin radius.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional schematic representation of an aquaporin. The cylindrical domain is the pore channel, is the membrane thickness and is the aquaporin radius.

Figure 4.

Transmembrane electric potential.

Figure 4.

Transmembrane electric potential.

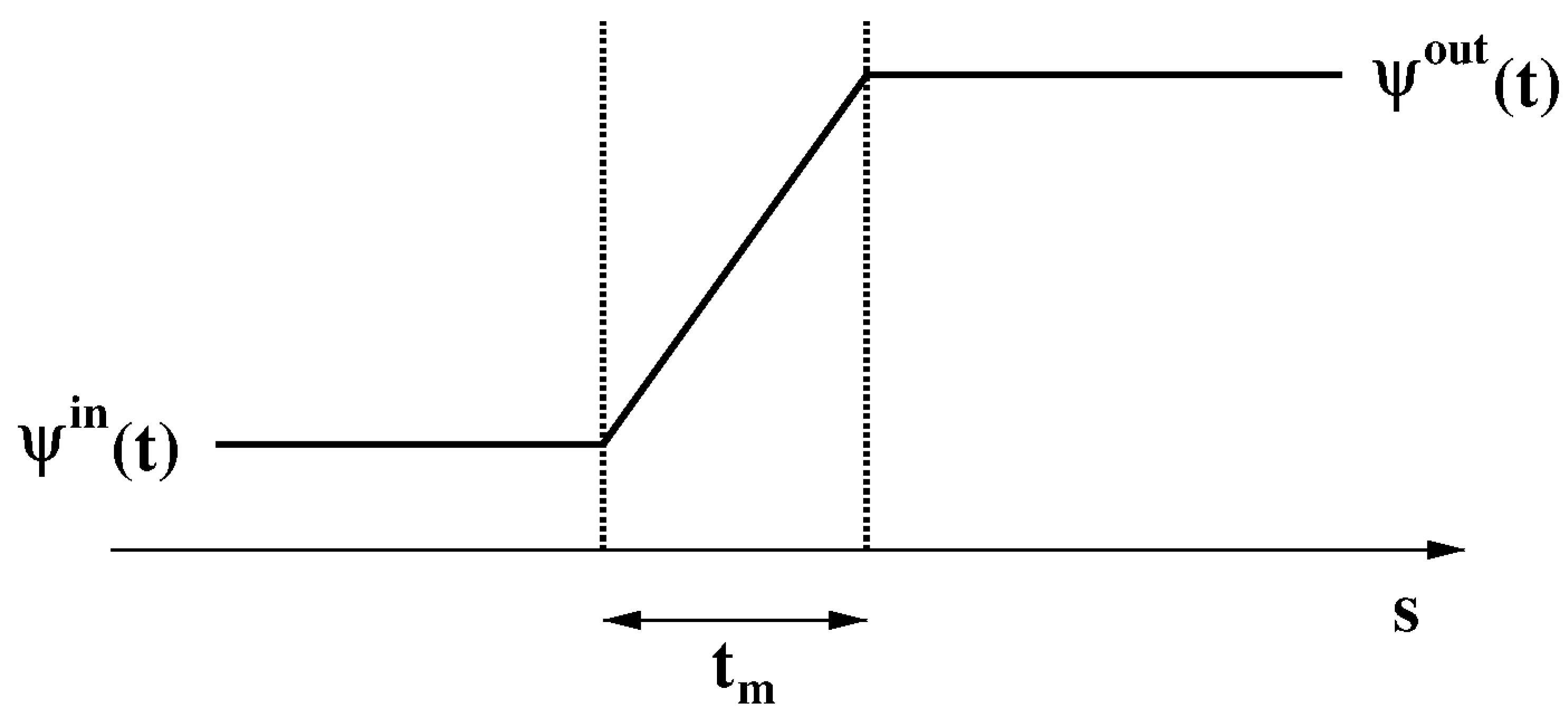

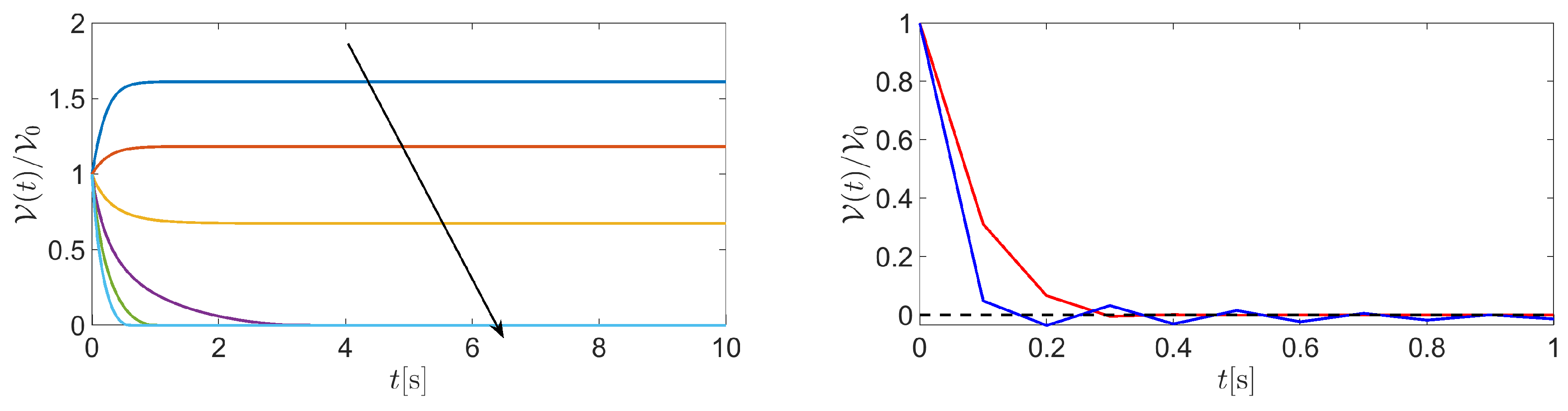

Figure 5.

Left panel: plot of . Right panel: plot of in the time interval . The values of the input data are: , , , and . Right panel:

Figure 5.

Left panel: plot of . Right panel: plot of in the time interval . The values of the input data are: , , , and . Right panel:

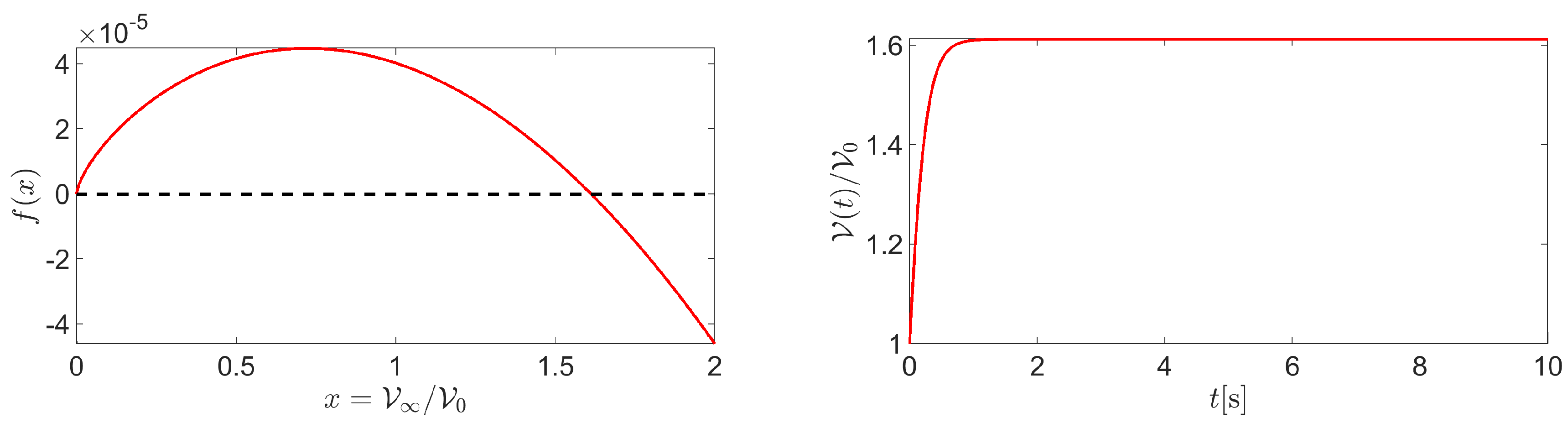

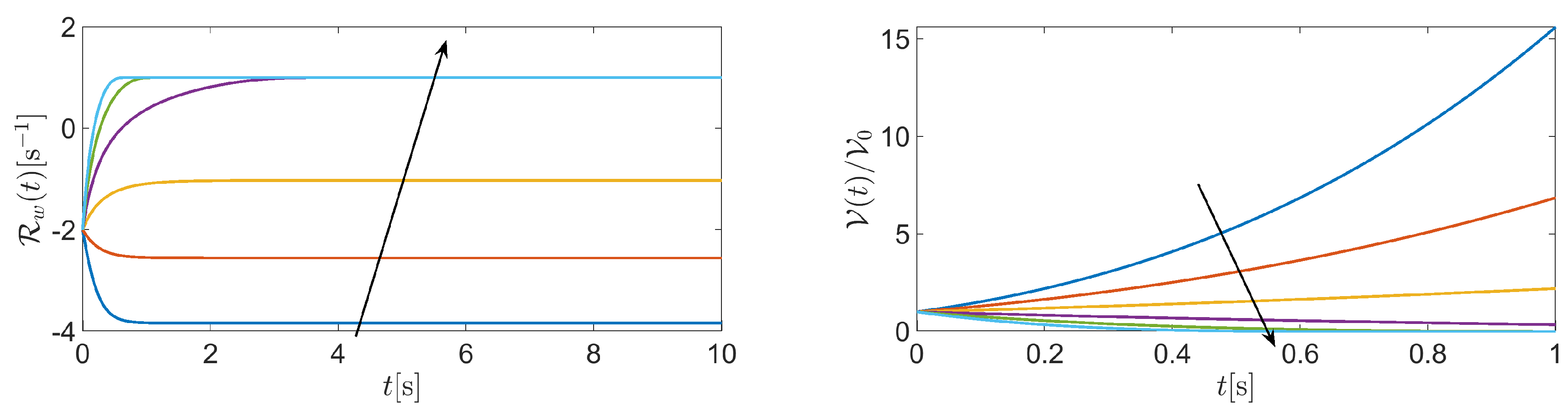

Figure 6.

Left panel: plot of in the time interval . Fluid velocity varies in the range . The arrow indicates velocity increase from negative to positive values. Right panel: plot of in the time interval .

Figure 6.

Left panel: plot of in the time interval . Fluid velocity varies in the range . The arrow indicates velocity increase from negative to positive values. Right panel: plot of in the time interval .

Figure 7.

Left panel: plot of the water volume net production rate in the time interval . Right panel: plot of in the time interval in the case where for every . Fluid velocity varies in the range . The arrow indicates velocity increase from negative to positive values.

Figure 7.

Left panel: plot of the water volume net production rate in the time interval . Right panel: plot of in the time interval in the case where for every . Fluid velocity varies in the range . The arrow indicates velocity increase from negative to positive values.

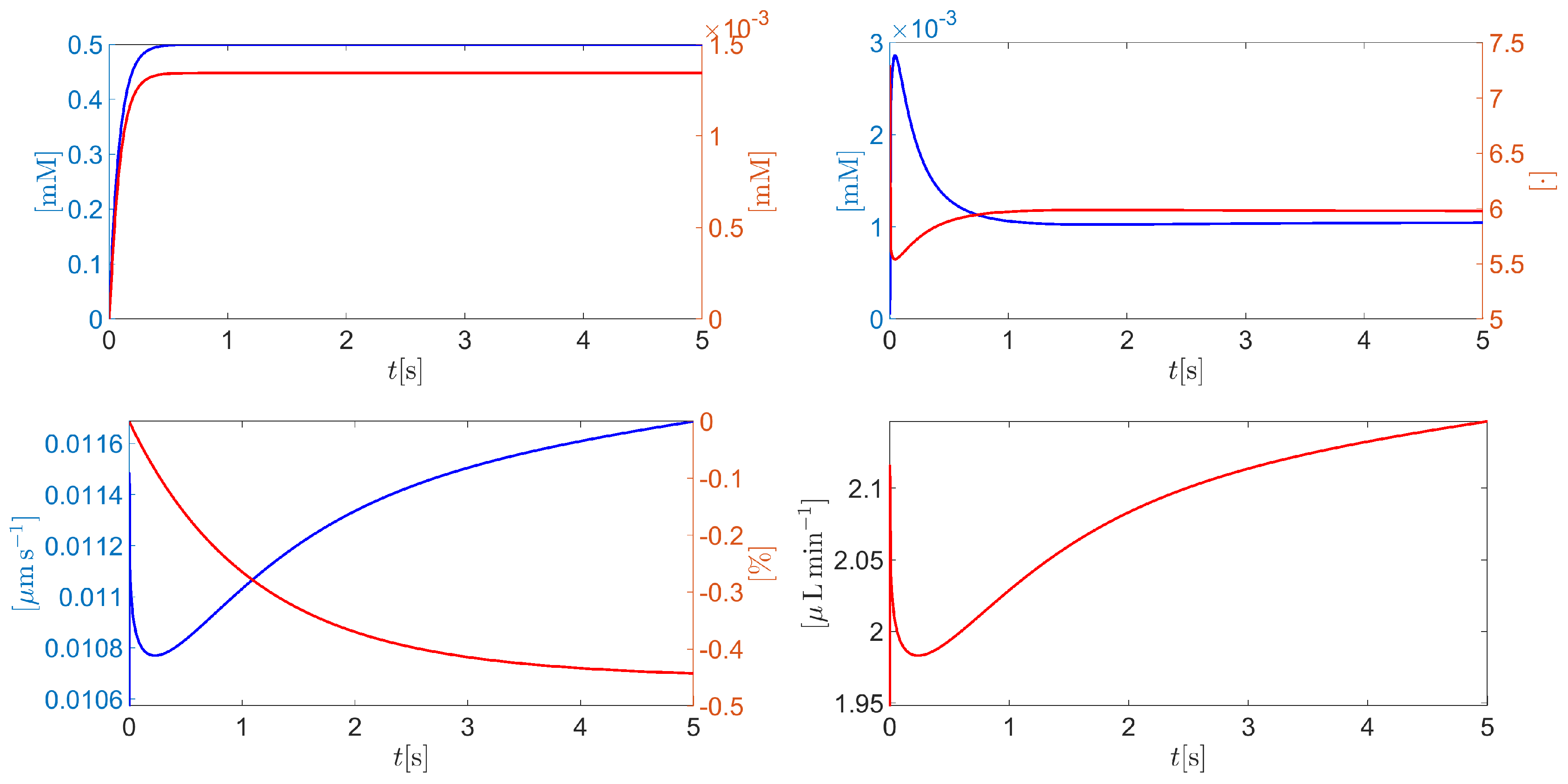

Figure 8.

Left panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Right panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Middle panel (bottom): total AH volumetric flow rate for .

Figure 8.

Left panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Right panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Middle panel (bottom): total AH volumetric flow rate for .

Figure 9.

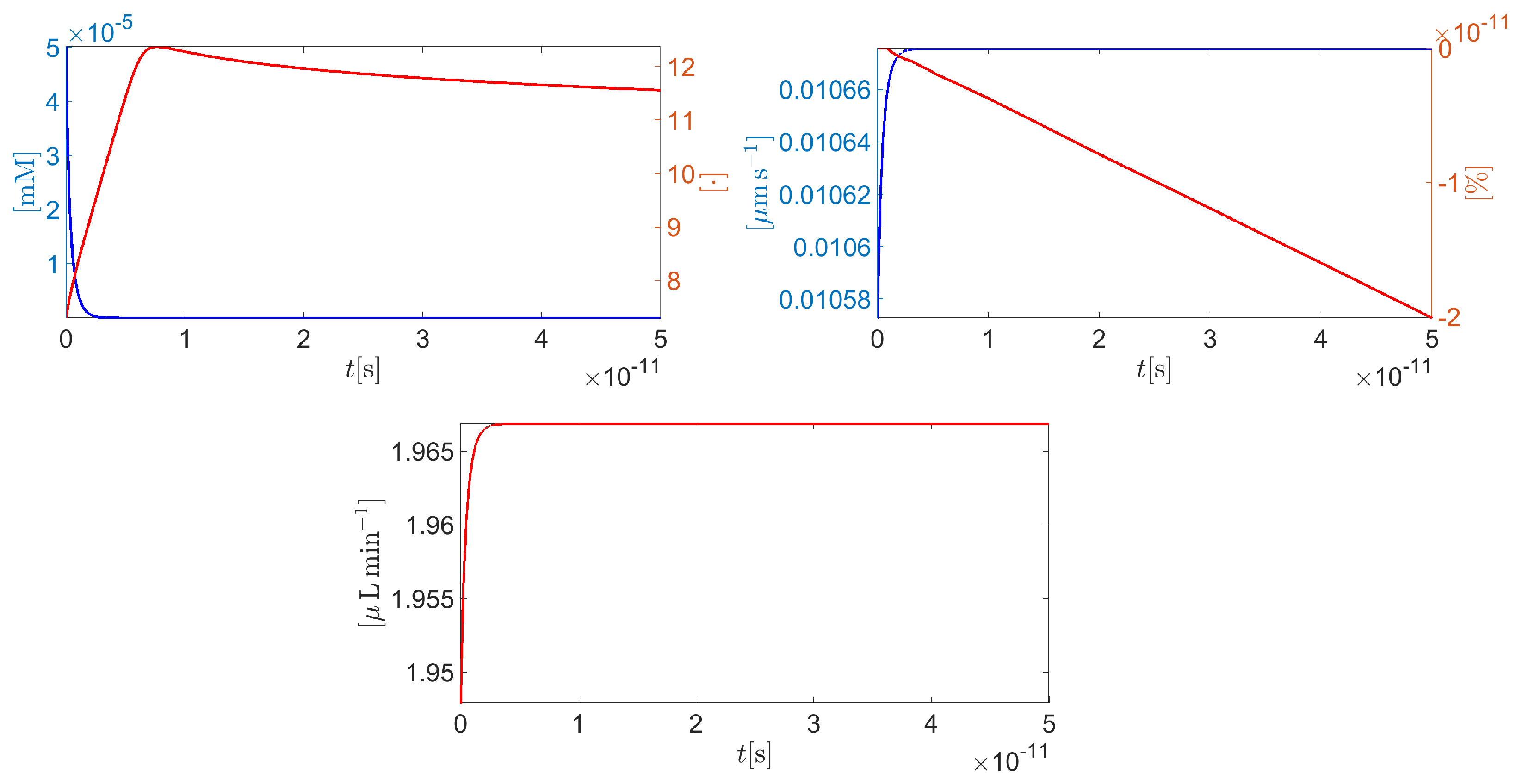

Top left panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Top right panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Bottom left panel: blue curve: average cell normal surface velocity , red curve: percentage volume variation , . Bottom right panel: total AH volumetric flow rate for .

Figure 9.

Top left panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Top right panel: blue curve: , red curve: , . Bottom left panel: blue curve: average cell normal surface velocity , red curve: percentage volume variation , . Bottom right panel: total AH volumetric flow rate for .

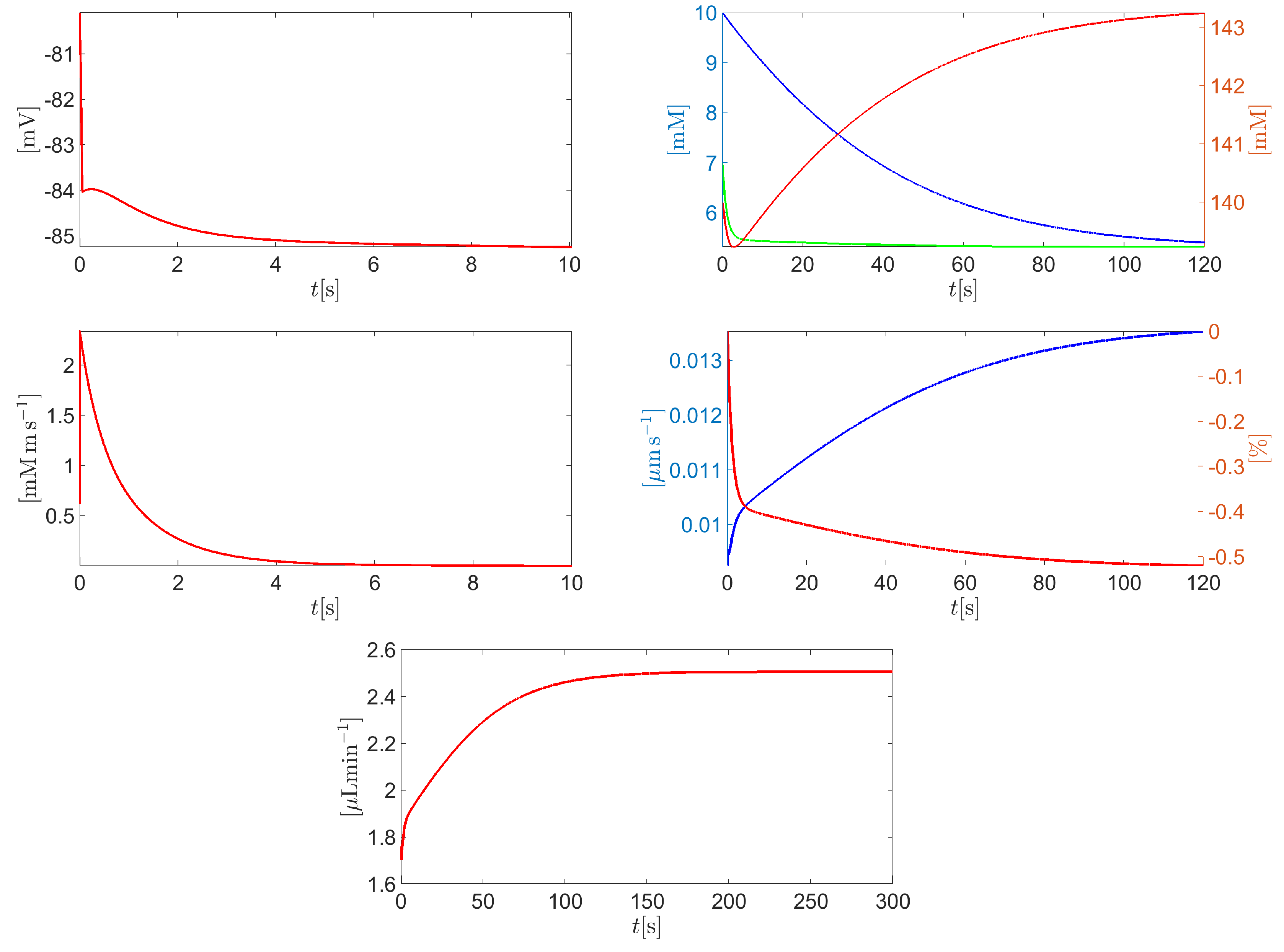

Figure 10.

Top left panel: zoom of the membrane potential (units: ) in the time interval . Top right panel: zoom of (blue curve); (red curve); (green curve) (units: ) in the time interval . Middle left panel: zoom of chlorine molar flux density (units: ) in the time interval . Middle right panel: zoom of (blue curve); (red curve) in the time interval . Bottom center panel: zoom of the total AH volumetric flow rate in the time interval .

Figure 10.

Top left panel: zoom of the membrane potential (units: ) in the time interval . Top right panel: zoom of (blue curve); (red curve); (green curve) (units: ) in the time interval . Middle left panel: zoom of chlorine molar flux density (units: ) in the time interval . Middle right panel: zoom of (blue curve); (red curve) in the time interval . Bottom center panel: zoom of the total AH volumetric flow rate in the time interval .

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the processes involved in AH dynamics. (1): AH production; (2): AH flow; (3): AH outflow. Reprinted from R. Ramakrishnan et al, Diagnosis & Management of Glaucoma, Chapter 9 Aqueous Humor Dynamics, 10.5005/jp/books/11801_9, (2013) [

34]; used in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the processes involved in AH dynamics. (1): AH production; (2): AH flow; (3): AH outflow. Reprinted from R. Ramakrishnan et al, Diagnosis & Management of Glaucoma, Chapter 9 Aqueous Humor Dynamics, 10.5005/jp/books/11801_9, (2013) [

34]; used in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Figure 12.

Left panel: total AH volumetric flow rate for as a function of . The black dashed line indicates the physiological value of , equal to 2.75 , when IOP = 15 mmHg. Right panel: total osmo-oncotic pressure difference for as a function of .

Figure 12.

Left panel: total AH volumetric flow rate for as a function of . The black dashed line indicates the physiological value of , equal to 2.75 , when IOP = 15 mmHg. Right panel: total osmo-oncotic pressure difference for as a function of .

Figure 13.

Total AH volumetric flow rate for as a function of . The black dashed line indicates the physiological value of , equal to 2.75 , when IOP = 15 mmHg.

Figure 13.

Total AH volumetric flow rate for as a function of . The black dashed line indicates the physiological value of , equal to 2.75 , when IOP = 15 mmHg.

Figure 14.

Zoomed view of total AH volumetric flow rate for as a function of . The physiological value of is equal to 2.75 when IOP = 15 mmHg.

Figure 14.

Zoomed view of total AH volumetric flow rate for as a function of . The physiological value of is equal to 2.75 when IOP = 15 mmHg.

Figure 15.

Plot of the % difference between at baseline conditions and for IOP in the interval [15, 150] mmHg, with .

Figure 15.

Plot of the % difference between at baseline conditions and for IOP in the interval [15, 150] mmHg, with .

Table 1.

Model parameters: symbol, value and units.

Table 1.

Model parameters: symbol, value and units.

| Symbol |

Value |

Units |

| T |

298.15 |

K |

|

|

m |

|

|

m |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.9974 |

|