Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

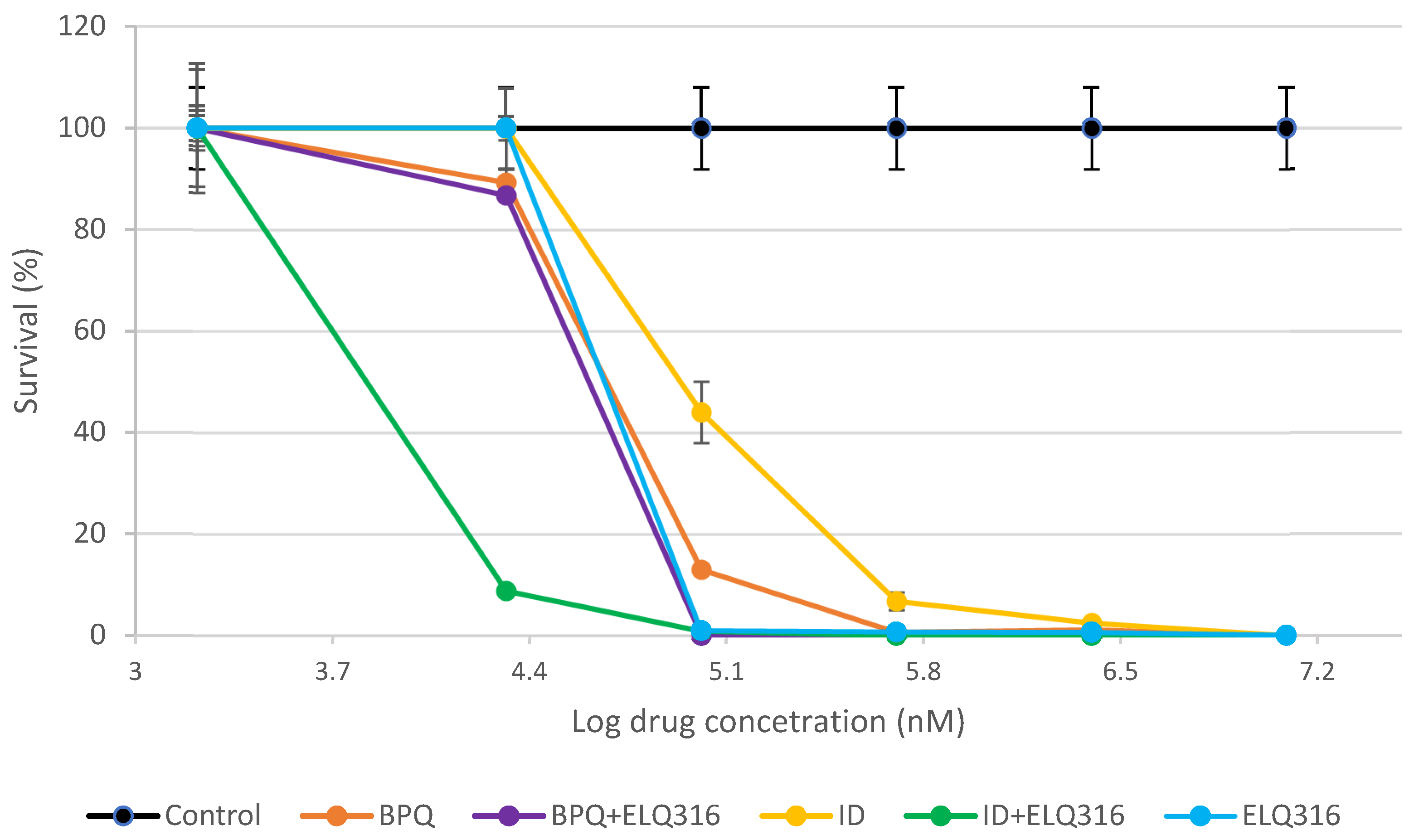

Background/Objectives: B. bigemina is a highly pathogenic and widely distributed tick-borne disease parasite responsible for bovine babesiosis. The development of effective and safe therapies is urgently needed for global disease control. The aim of this study was to compare the effects of endochin-like quinolone (ELQ316), buparvaquone (BPQ), imidocarb (ID), and the combinations of ID + ELQ-316 and BPQ + ELQ-316, on in vitro survival of B. bigemina. Methods: Parasites at a starting parasitemia level of 2%, were incubated with each single drug and combination of drugs, ranging from 25 to 1200 nM of concentration over four consecutive days. The inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50%) and 99% (IC99%) were estimated. Parasitemia levels were evaluated daily using microscopic examination. Data were statistically compared using the non-parametrical KruskallWallis test. Results: All drugs tested significantly inhibited (p<0.05) the growth of B. bigemina at 2% parasitemia. The combination of ID + ELQ-316 exhibited lower mean IC50% (9.2); confidence interval 95% (8.7 – 9.9) than ID (IC50%: 61.5; confidence interval 95%: 59.54 - 63.46), ELQ-316 (IC50%: 48.10; confidence interval 95%: 42.76 – 58.83), BPQ (IC50%: 44.66; confidence interval 95%: 43.56 – 45.81), and BPQ + ELQ-316 (IC50%: 27.59; confidence interval: N/A). Parasites were no longer viable in cultures treated with the BPQ + ELQ-316 combination, as well as with BPQ alone at a concentration of 1200 nM, on days 2 and 3 of treatment, respectively.; Conclusions: BPQ and ID increase the babesiacidal effect of ELQ-316. The efficacy of these combinations deserves to be evaluated in vivo, which could lead to a promising and safer treatment option against B. bigemina.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Comparative inhibitory effects of BPQ, ID and ELQ-316 and the combinations ELQ-316+BPQ and ELQ-316+ID against B. bigemina in vitro replication

2.2. Drug Potency

| Drugs | IC50% (nM) | IC99% (nM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95 % CI | Mean | 95 % CI | ||

| ID + ELQ-316 | 9.248 | (8.667 – 9.887) | 65.52 | (61.35 – 69.81) | |

| BPQ + ELQ-316 | 27.59 | N/A | 34.23 | N/A | |

| BPQ | 44.66 | (43.56 – 45.81) | 156.4 | (148.9 – 164.4) | |

| ELQ-316 | 48.10 | (42.76 – 58.83) | 133 | (102.2 – 155.6) | |

| ID | 61.49 | (59.54 - 63.46) | 441.4 | (392.3 – 498) | |

2.3. Time and drug concentration required to reach 0% survival after treatment

| Single drugs and combination treatments | Time post-treatment with drug (h) | Time post-treatment without drug (h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | 72 | 96 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | 120 | |

| BPQ | - | 1200 | 600 to 1200 | (--------------- 150 to 1200 ------------) | ||||

| BPQ + ELQ-316 | 1200 | 300 to 1200 | (------------------------- 75 to 1200 ----------------------) | |||||

| ELQ-316 | - | 1200 | 600 to 1200 | (--------------- 150 to 1200 ------------) | ||||

| ID+ELQ-316 | - | 600 to 1200 | (--------- 150 to 1200 -------) | (------ 75 to 1200 -----) | ||||

| ID | - | - | 600 - 1200 | 300-1200 | (----- 150 to 1200 ----) | |||

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical reagents

4.2. Parasites Culture

4.3. In vitro growth of initial inhibitory assay

4.4. Viability after Treatment

4.5. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asrar, R.; Farhan, H.R.; Sultan, D.; Ahmad, M.; Hassan, S.; Kalim, F.; Shakoor, A.; Muhammad Taimoor Ihsan, H.; Shahab, A.; Ali, W.; et al. Review Article Bovine Babesiosis; Review on Its Global Prevalence and Anticipatory Control for One Health. Cont. Vet J 2022, 2, 42–49.

- Bock, R.; Jackson, L.; De Vos, A.; Jorgensen, W. Babesiosis of Cattle. Parasitology 2004, 129, S247–S269. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.S.; Sengupta, P.P.; Paramanandham, K.; Suresh, K.P.; Chamuah, J.K.; Rudramurthy, G.R.; Roy, P. Bovine Babesiosis: An Insight into the Global Perspective on the Disease Distribution by Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 283, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pipano, E.; Hadani, A. Control of Bovine Babesiosis. In Malaria and Babesiosis. Ristic, M. Ambroise-Thomas, P. Kreier, J.P.; Springer: Berlin/ Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 263–303.

- He, L.; Bastos, R.G.; Sun, Y.; Hua, G.; Guan, G.; Zhao, J.; Suarez, C.E. Babesiosis as a Potential Threat for Bovine Production in China. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.; Gadahi, J.A.; Bhutto, B.; Tunio, S.; Vistro, W.A.; Tunio, H.; Bhutto, S.; Ram, T. Babesiosis: Current Status and Future Perspectives in Pakistan and Chemotherapy Used in Livestock and Pet Animals. Heliyon 2023, e17172, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Vial, H.J.; Gorenflot, A. Chemotherapy against Babesiosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 138, 147–160. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-J.; Yamasaki, M.; Nakamura, K.; Sasaki, N.; Murakami, M.; Kumara, B.; Rajapakshage, W.; Ohta, H.; Maede, Y.; Takiguchi, M. Development and Characterization of a Strain of Babesia Gibsoni Resistant to Diminazene Aceturate In Vitro. J. Vet. Med. Sci 2010, 72, 765–771.

- Tuntasuvan, D.; Jarabrum, W.; Viseshakul, N.; Mohkaew, K.; Borisutsuwan, S.; Theeraphan, A.; Kongkanjana, N. Chemotherapy of Surra in Horses and Mules with Diminazene Aceturate. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 110, 227–233. [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda, J.; Olvera-Ramírez, A.; Aguilar-Tipacamú, G.; Cantó, G.J. Current Advances in Detection and Treatment of Babesiosis; 2012; Vol. 19, pp. 1504–1518;

- Bailey, G. Buparvaquone Tissue Residue Study. Final Report. NSW Department of Primary Industries. 2013, 1–152.

- Cardillo, N.M.; Lacy, P.A.; Villarino, N.F.; Doggett, J.S.; Riscoe, M.K.; Bastos, R.G.; Laughery, J.M.; Ueti, M.W.; Suarez, C.E. Comparative Efficacy of Buparvaquone and Imidocarb in Inhibiting the in Vitro Growth of Babesia Bovis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024a, 15. [CrossRef]

- Carter, P. Assessment of the Efficacy of Buparvaquone for the Treatment of “benign” Bovine Theileriosis. Tick Fever Centre Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation. 2011, 1–12.

- Checa, R.; Montoya, A.; Ortega, N.; González-Fraga, J.L.; Bartolomé, A.; Gálvez, R.; Marino, V.; Miró, G. Efficacy, Safety and Tolerance of Imidocarb Dipropionate versus Atovaquone or Buparvaquone plus Azithromycin Used to Treat Sick Dogs Naturally Infected with the Babesia Microti-like Piroplasm. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Goud, S.K.; Vijayakumar, K.; Davis, J.; Tresamol, P.V.; Ravishankar, C.; Devada, K. Efficacy of Different Treatment Regimens against Oriental Theileriosis in Naturally Infected Cattle. Indian J. Vet. Med 2021, 40, 14–19.

- Hudson, A.T.; Randall, A.W.; Fry, M.; Ginger, C.D.; Hill, B.; Latter, V.S.; McHardy, N.; Williams, R.B. Novel Anti-Malarial Hydroxynpahthoquinones with Potent Broad Spectrum Anti-Protozoal Activity. Parasitology 1985, 90, 45–55.

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, A.K.; Pal, Y.; Dwivedi, S.K. In-Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy Trial with Artemisinin Derivative, Buparvaquone and Imidocarb Dipropionate against Babesia Equi Infection in Donkeys. J. Vet. Med. Sci 2003, 65, 1171–1177.

- Muraguri, G.R.; Ngumi, P.N.; Wesonga, D.; Ndungu, S.G.; Wanjohi, J.M.; Bang, K.; Fox, A.; Dunne, J.; McHardy, N. Clinical Efficacy and Plasma Concentrations of Two Formulations of Buparvaquone in Cattle Infected with East Coast Fever (Theileria Parva Infection). Res. Vet. Sci. 2006, 81, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, G.M.; Kirvar, E.; Thomas, E.M.; Sparagano, O.; Brown, C.G.D. Stage-Specific Activity in Vitro on the Theileria Infection Process of Serum from Calves Treated Prophylactically with Buparvaquone. Vet. Parasitol. 1998, 80, 127–136.

- Nugraha, A.B.; Tuvshintulga, B.; Guswanto, A.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Rizk, M.A.; Gantuya, S.; El-Saber Batiha, G.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Sivakumar, T.; Yokoyama, N.; et al. Screening the Medicines for Malaria Venture Pathogen Box against Piroplasm Parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. : Drugs Drug Resist. 2019, 10, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Aguado-Martinez, A.; Manser, V.; Balmer, V.; Winzer, P.; Ritler, D.; Hostettler, I.; Solís, D.A.; Ortega-Mora, L.; Hemphill, A. Buparvaquone Is Active against Neospora Caninum in Vitro and in Experimentally Infected Mice. Int. J. Parasitol. : Drugs Drug Resist. 2015, 5, 16–25. [CrossRef]

- Fray, M.; Pudney, M. Site of Action of the Antimalarial Hydroxynaphthoquinone,2- [Trans-4-(40chlorophenyl)Cyclohexyl]-3-Hydroxy-1,4,-Naphthoquinone (566c80). Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992, 40, 914–919. [CrossRef]

- Mhadhbi, M.; Chaouch, M.; Ajroud, K.; Darghouth, M.A.; BenAbderrazak, S. Sequence Polymorphism of Cytochrome b Gene in Theileria Annulata Tunisian Isolates and Its Association with Buparvaquone Treatment Failure. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Sharifiyazdi, H.; Namazi, F.; Oryan, A.; Shahriari, R.; Razavi, M. Point Mutations in the Theileria Annulata Cytochrome b Gene Is Associated with Buparvaquone Treatment Failure. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 431–435. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.V.; Bruzual, I.; Pou, S.; Winter, R.; Dodean, R.A.; Smilkstein, M.J.; Krollenbrock, A.; Nilsen, A.; Zakharov, L.N.; Riscoe, M.K.; et al. Targeted Structure-Activity Analysis of Endochin-like Quinolones Reveals Potent Qi and Qo Site Inhibitors of Toxoplasma Gondii and Plasmodium Falciparum Cytochrome Bc1 and Identifies ELQ-400 as a Remarkably Effective Compound against Acute Experimental Toxoplasmosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1574–1584. [CrossRef]

- Lawres, L.A.; Garg, A.; Kumar, V.; Bruzual, I.; Forquer, I.P.; Renard, I.; Virji, A.Z.; Boulard, P.; Rodriguez, E.X.; Allen, A.J.; et al. Radical Cure of Experimental Babesiosis in Immunodeficient Mice Using a Combination of an Endochin-like Quinolone and Atovaquone. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 1307–1318. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.R.; Bruno, P.M.; Gilbert, L.A.; Capron, K.L.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Hemann, M.T. Defining Principles of Combination Drug Mechanisms of Action. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.G.; Bastos, R.G.; Stone Doggett, J.; Riscoe, M.K.; Pou, S.; Winter, R.; Dodean, R.A.; Nilsen, A.; Suarez, C.E. Endochin-like Quinolone-300 and ELQ-316 Inhibit Babesia Bovis, B. Bigemina, B. Caballi and Theileria Equi. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, N.; Balmer, V.; Müller, J.; Müller, N.; Winter, R.; Pou, S.; Nilsen, A.; Riscoe, M.; Francisco, S.; Leitao, A.; et al. Activities of Endochin-Like Quinolones Against in Vitro Cultured Besnoitia Besnoiti Tachyzoites. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, N.M.; Villarino, N.F.; Lacy, P.A.; Riscoe, M.K.; Doggett, J.S.; Ueti, M.W.; Chung, C.J.; Suarez, C.E. The Combination of Buparvaquone and ELQ316 Exhibit a Stronger Effect than ELQ316 and Imidocarb Against Babesia Bovis In Vitro. Pharmaceutics 2024b, 16, 1402. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.A.; El-Sayed, S.A.E.-S.; Igarashi, I. Diminazene Aceturate and Imidocarb Dipropionate-Based Combination Therapy for Babesiosis – A New Paradigm. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102145. [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, R.A.; Viscaino, O.G.; Gonzalez, E.F.; Adams, L.G. Chemoprophylaxis (Imidocarb) against Babesia Bigemina and Babesia Argentina Infections. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1973, 34, 1153–1161.

- Silva, M.G.; Villarino, N.F.; Knowles, D.P.; Suarez, C.E. Assessment of Draxxin® (Tulathromycin) as an Inhibitor of in Vitro Growth of Babesia Bovis, Babesia Bigemina and Theileria Equi. Int. J. Parasitol. : Drugs Drug Resist. 2018, 8, 265–270. [CrossRef]

- Mazuz, M.L.; Golenser, J.; Fish, L.; Haynes, R.K.; Wollkomirsky, R.; Leibovich, B.; Shkap, V. Artemisone Inhibits in Vitro and in Vivo Propagation of Babesia Bovis and B. Bigemina Parasites. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 135, 690–694. [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.; Kelly, J.X.; Smilkstein, M.J.; Hinrichs, D.; Koop, D.R.; Riscoe, M.K. Optimization of Endochin-like Quinolones for Antimalarial Activity. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 127, 545–551. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.A.; El-Sayed, S.A.E.S.; El-Khodery, S.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Discovering the in Vitro Potent Inhibitors against Babesia and Theileria Parasites by Repurposing the Malaria Box: A Review. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 274, 108895. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.A.; El-Sayed, S.A.E.S.; Nassif, M.; Mosqueda, J.; Xuan, X.; Igarashi, I. Assay Methods for in Vitro and in Vivo Anti-Babesia Drug Efficacy Testing: Current Progress, Outlook, and Challenges. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 279, 109013. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.A.; El-Sayed, S.A.E.S.; AbouLaila, M.; Tuvshintulga, B.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Large-Scale Drug Screening against Babesia Divergens Parasite Using a Fluorescence-Based High-Throughput Screening Assay. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 227, 93–97. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.A.; El-Sayed, S.A.E.-S.; Terkawi, M.A.; Youssef, M.A.; El Said, E.S.E.S.; Elsayed, G.; El-Khodery, S.; El-Ashker, M.; Elsify, A.; Omar, M.; et al. Optimization of a Fluorescence-Based Assay for Large-Scale Drug Screening against Babesia and Theileria Parasites. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125276. [CrossRef]

- Mehlhorn, H. Babesiacidal Drugs. In Encyclopedia of Parasitology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016; pp. 1–11.

- Nilsen, A.; Miley, G.P.; Forquer, I.P.; Mather, M.W.; Katneni, K.; Li, Y.; Pou, S.; Pershing, A.M.; Stickles, A.M.; Ryan, E.; et al. Discovery, Synthesis, and Optimization of Antimalarial 4(1H)-Quinolone-3-Diarylethers. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3818. [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.G.; Ristic, M. Babesia Bovis: Continuous Cultivation in a Microaerophilous Stationary Phase Culture. Science 1980, 207, 1218–1220.

- Bennett, T.N.; Paguio, M.; Gligorijevic, B.; Seudieu, C.; Kosar, A.D.; Davidson, E.; Roepe, P.D. Novel, Rapid, and Inexpensive Cell-Based Quantification of Antimalarial Drug Efficacy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1807. [CrossRef]

| Drug treatment (nM) |

BPQ | ID | ELQ316 | ID+ELQ316 | BPQ+ELQ316 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median range (%) | |||||

| 25 | 89.26 (84.30-92.98) | 100 (88-100) | 100 (89.26-100) | 8.80 (6.94-11.9) | 86.78 (79.34-100) |

| 75 | 13.02 (8.68-13.64)a,b | 44.01 (38.43-49.59)b | 0.87 (0.62-0.99) a,b | 0.87 (0.62-0.99) c,a | 0 c |

| 150 | 0.62 (0.37-0.74)a | 6.76 (2.48-11.03)a | 0.65 (0.5-1.12)a | 0 c | 0 c |

| 300 | 1.12 (0.99-1.86)a | 2.48 (1.24-3.72)a | 0.53 (0.37-0.87)a,b | 0 c | 0 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).