1. Introduction

Agriculture is vital for human survival and the global economy. In 2020, this primary sector was valued at nearly 3.8 billion USD [

1]. With the world’s population projected to exceed 10 billion by 2060 [

2], the demand for food is set to rise, putting pressure on farmers to increase crop yields while minimizing environmental impact. This pressure has led to widespread use of fertilizers, as well as to deforestation [

3].

Fertilizers, proven beneficial in agriculture since ancient times [

4], include exogenous organic matter (EOM) like minerals, compost, wood ash and manure. These substances enhance farm productivity by enriching soil nutrients and improving its chemical and physical properties [

5]. However, excessive fertilizer use can harm the environment, causing soil degradation, water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions [

6]. Nitrogen is a key factor for plant growth, but when in excess it can have detrimental effects on both humans and the environment. In Europe, agricultural nitrogen contributes significantly to water pollution, with nitrates and organic nitrogen compounds from fertilizers and manure seeping into groundwater and flowing into surface water [

7].

Intense nitrate pollution can render water undrinkable and foster excessive algae growth in aquatic ecosystems, leading to eutrophication [

8]. This harms biodiversity, fisheries and recreation, emphasizing the need to combat excess nitrogen in the environment. To address this issue, the European Union (EU), for example, issued the

nitrates directive [

9] to regulate fertilizers use. One proposed solution is implementing

closed periods for organic fertilizer in nitrate-vulnerable zones [

10]. Closed periods restrict fertilizer spreading to specific time windows, depending on local features and situation. Compared to ground surveying, spaceborne Earth observation (EO) techniques may represent a cost-effective tool to check directive compliance by identifying manure application events in agriculture [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of multispectral satellite imagery, particularly from Sentinel-2, in identifying areas where livestock manure is applied. A pivotal study [

17] carried out a preliminary identification of spectral indexes that can support the detection of manuring events, focusing on farmlands located in France. This research demonstrated that Sentinel-2 imagery can effectively detect changes in spectral characteristics resulting from the application of exogenous organic matter (EOM) such as GWC and livestock manure. Specifically, the analysis revealed significant spectral differences in Sentinel-2 images taken before and after the application of EOM. This indicates that satellite imagery can be a reliable tool for identifying when and where these amendments are applied in agricultural landscapes. The study, however, identifies several limitations; for example, Sentinel-2 struggles to detect low EOM application rates, and its spatial and temporal resolution may miss rapid agricultural changes, affecting accuracy. Moreover, soil, crops, and environmental variability make the generalizability of spectral indices across regions even more difficult. Lastly, since the research was conducted in a specific region of France, the findings may not apply to areas with different climates or agricultural practices.

Another study [

18] achieved an

F-1 test score of around 89% by developing a pixel-wise manure detection method between two consecutive Sentinel-2 acquisitions. The authors suggest that certain wavelengths in the near-infrared and visible spectrum are most effective for capturing the unique reflectance characteristics of freshly manured fields. Moreover, their results highlighted the importance of timing in data acquisition. In fact, the effectiveness of remote sensing in detecting manure decreases over time as the manure decomposes and its spectral signature fades. However, limitations include environmental variability, limited field validation and, most importantly, a priori knowledge of fertilization dates, which is not always available.

Another interesting study reported in [

19] introduces a new spectral index that can effectively detect areas where livestock manure and digestate have been spread. This index is based on the spectral response of bare soil compared to that of the manure and digestate, demonstrating its potential usefulness in agricultural monitoring. The proposed spectral index achieves an accuracy of 62.53% when detecting manure spreading, which is considered a promising result. This level of accuracy, however, may not be sufficient for all applications, particularly in precision agriculture where effective decision-making requires higher levels of confidence. Moreover, the effectiveness of the spectral index relies on the availability and accuracy of ancillary datasets, such as soil moisture and precipitation. Variations or inaccuracies in these datasets could impact the reliability of the spectral index in detecting manure spreading.

Generally, multispectral data is the primary choice for detecting manure cover over crop fields due to its capacity to capture vegetation and soil responses to organic amendments. However, based on our review of scientific literature, it emerged that no more than one paper incorporated radar and thermal data for this purpose. In [

20], the authors utilized random forest models that combined C-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data, multispectral and thermal imagery, along with other predictive variables, to monitor soil moisture conditions indicative of liquid manure applications. This analysis focused on sprayfields in eastern North Carolina, USA, where distinct patterns of manure application across various fields and timeframes were identified. By leveraging different types of remotely sensed data, the study was able to derive both the timing and location of manure applications, providing insights into the frequency and scheduling of these events.

Inspired by this approach, our study builds on these findings by applying similar techniques to detect solid cow manure applications. We considered several aspects of this prior work, particularly its use of integrated data sources, as we adapted the methodology to address the specific challenges associated with identifying solid manure applications. Our work presents an innovative method for identifying manure application events through multi-time series analysis, uniquely combining the identification of event dates with an exploration of correlations across optical, radar, and thermal indices. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this approach is the first of its kind. This approach aims to enhance the robustness of detection while also clarifying the role and importance of each index involved. The primary goal is to simplify predictive models by reducing the number of input features, thus making the models more efficient and easier to interpret. By integrating this method with the approach outlined in the previously referenced study [

18], there is potential to detect manure applications over various time series and determine their spatial distribution on farmland within specified time frames.

To achieve these goals, the study leverages Machine Learning (ML) techniques, which are widely used in Earth Observation (EO) applications. A range of ML models were implemented, trained, and evaluated using several performance metrics, including their ability to generalize across data sets [

21]. This comprehensive assessment allows for a comparison of model strengths, ending up with the most effective approach for detecting and mapping manure application events over time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ground Truth Data

Manuring data about crop fields located in Spain were sourced from the “Satellite imagery dataset of manure application on pasture fields” [

22]. The average field size exceeds 10,000 square meters, with a total of 30 fields that lie inside the region depicted in

Figure 1 (top).

The Italian dataset was added to assess generalization capabilities, enabling mixed training and testing. In a first subset, manure application dates for 26 fields in Northern Italy were determined through on-site surveying. A second subset was sourced from the regional DUSAF (Destination of Use of Agricultural and Forestry Soils) [

23] archive referring to year 2018 in the Lombardy region of Northern Italy. Here, agricultural parcels in use could be delineated but manuring dates were unavailable, and only statistical evaluations could be made. Those farmlands coordinates were obtained via Google Earth Engine (GEE). A total of around 300 fields, the area of interest is depicted in

Figure 1 (bottom), were included, with an average field size of almost 32,000 square meters.

2.2. Satellite Data

In this work, we used Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Landsat-8 data due primarily to their open-data policy, offering free access to spaceborne sensing data. These satellites offer a comprehensive range of sensors, enabling both SAR (Sentinel-1) and optical/thermal (Sentinel-2, Landsat-8) imaging. This combination allows us to extract essential indices for monitoring the effects of manure application.

Sentinel-1 revisits the same location on the Earth every 6 days, Sentinel-2 every 5 days and Landsat-8 every 16 days. These revisit times ensure continuous monitoring, allowing for timely observation of changes in agricultural fields. Their long-term operation also provides consistent data streams for detecting long-term environmental trends.

Regarding spatial resolution, Sentinel-1 offers C-band radar imaging with a spatial resolution of 15 meters in standard Interferometric Wide (IW) swath for both VV and VH polarizations. Sentinel-2 provides multi-spectral imagery with resolutions ranging from 10 to 60 meters depending on the band, while Landsat-8 offers 30-meter resolution for multi-spectral data and 15 meters for panchromatic imaging. These high spatial resolutions enable detailed analysis of crop health and soil conditions, supporting precise environmental monitoring.

2.3. Methods

The methodology illustrated in

Figure 2 involves several steps aimed at analyzing time series data from agricultural fields and applying machine learning to detect the impact of manure application. First, datasets from agricultural fields located in Spain and Italy were collected. These datasets consisted of Sentinel-1 SAR data plus Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 optical satellite data collected in a period of time. Crop fields from two different regions were selected to ensure robustness and generality of the analysis, allowing the models to perform across different geographical areas.

Next, various optical and radar indices were extracted from the time series data. These indices, such as vegetation, water content, or radar-based measures, provide important insights about the physical properties of the soils. The goal of this extraction step is to determine the most relevant indicators of how manure application influences the fields.

Once the indices were extracted, a filtering process was applied to narrow down the most important and uncorrelated indices. The first part of this step involved computing the importance of each index, identifying those that are most impacted by manure application. Then, a correlation analysis was performed to ensure that only uncorrelated indices were selected, avoiding redundancy. This is important because highly correlated features can lead to overfitting, where the model learns patterns that don’t generalize well when new data is presented in input.

After filtering, the remaining indices were used as the final dataset for training machine learning models. To prepare the data further, two processing steps were carried out. This included class balancing, a technique used to handle imbalances in the dataset, such as when fields without manure application vastly outnumber fields with. Additionally, feature normalization was applied to standardize the scale of the data. This step is crucial for certain models that are sensitive to the magnitude of input features.

Finally, a variety of machine learning models were trained and validated using this processed, final dataset. The models included logistic regression, linear discriminant analysis, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbor, and random forest. Each model has different strengths, and the goal was to identify which one performed best at classifying fields based on whether manure had been applied. By comparing their performance, the most accurate and generalizable model could be selected to detect in-field changes resulting from manure application.

2.4. Feature Extraction

A Python library was developed and made publicly available in a PyPI repository named

ee-satellites [

24,

25] to extract the identified indexes from optical, thermal, radar satellite data. This tool simplifies working with satellite data from Sentinel-1 (Ground Range Detected) [

26], Sentinel-2 (Surface Reflectance) [

27], and Landsat-8 (Top Of Atmosphere) [

28]. It also allowed to automatically apply cloud masking, image compositing and other data-cleaning steps, while exploiting multi-threading for efficient parallel processing of requests to GEE.

For each acquisition over an area of interest, the mean values of its spectral bands were calculated for that region, using the GEE

reduceRegion function. Clouds and shadows filtering was also applied to improve data quality. Subsequently, other spectral indexes were computed using the obtained mean band values (examples are provided in

Figure 3). The described extraction phase allows to reduce the number of requests to GEE, resulting in a significant speedup in the feature extraction procedure.

2.5. Features Importance and Correlation Analysis

As mentioned in the introduction, prior analysis is essential to identify the key features affected by manure application on farmlands. This involves tracking feature trends throughout the year and assessing their possible changes (or lack thereof) across manure application; this helps guiding feature selection for subsequent model development.

A

feature importance parameter

I has been therefore defined for each feature as the absolute difference of the feature’s value immediately after and before manure application (AM and BM, respectively), divided by the maximum absolute difference in feature values between any two consecutive acquisitions when manure was not applied. The analytical expression is presented in eq.

1, where

is the absolute value, and ¬ means “not”:

Feature selection is a critical process employed to enhance model performance and prevent overfitting by identifying and retaining only the most relevant features from a dataset. By selecting a subset of informative features, it is possible to reduce the complexity of the model, thereby minimizing the risk of overfitting, which occurs when a model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen data. To assess statistical significance, a one-sample t-test was conducted, with the threshold set to the commonly used value of . A value of p below the threshold suggests that the observed change was not the result of pure chance. If a correlation analysis is performed on the different indexes, it can be noticed that the majority of them are strongly correlated, for both the fields located in Italy and those in Spain. Therefore, only a subset of the indexes among the most mutually uncorrelated, and most impacted by manure application has been considered (for both optical, radar and thermal indexes). For example, regarding multispectral optical indexes, this subset contains: EOMI3, NSNDVI, EOMI1 and SDI. Then, those indexes were passed as input to different ML models as described in the following subsection.

2.6. Techniques

The different datasets underwent a meticulous transformation process to prepare them for ingestion in ML models. Each row was carefully modified to encapsulate the indexes variations between consecutive satellite acquisitions, together with a flag (binary variable) that indicates whether manuring took place between the previous and the current considered acquisitions. It is to be noted that samples with manuring flag 1 are much rarer than those with flag 0, as there may be one or two manuring episodes generating a positive sample for each observed field, but several acquisition dates across an agricultural season generating negative samples.

Thus, to mitigate class imbalance issues, both undersampling and oversampling techniques have been considered [

29]. More specifically, in undersampling, random samples from the majority class were picked - without replacement - while in oversampling, samples from the minority class were replicated multiple times. Feature selection played a crucial role in enhancing model performance [

30]. A forward feature selection approach was employed, systematically identifying the most relevant input indexes for a range of ML classifiers. Thus, only those features that significantly improved train and test accuracy without overfitting nor underfitting have been used. These classifiers included Logistic Regression [

31], Linear Discriminant Analysis [

32], Support Vector Classifier [

33], K-Nearest Neighbors [

34], and Random Forest Classifier [

35]. For each model, hyperparameters tuning [

36] has been applied, more specifically a grid-search technique. Grid search is a simple yet effective method for hyperparameter tuning, that is typically used to optimize one or two hyperparameters (sometimes three). If the best combination is found at the edge of the grid, the parameter range may need to be expanded to capture the optimal value. Identifying a suitable set of potential values can be challenging, but exploratory tests can help determine an appropriate range. For hyperparameters with values spanning different orders of magnitude, using a geometric progression is advisable. The results can reveal the model’s sensitivity to different hyperparameters and indicate which ones need careful tuning. If resources allow, repeating the search with a finer grid around the initial best combination can improve results.

Furthermore, to address variations in feature values, multiple scaling techniques were considered [

37], including Min-Max, Mean-Var, Max-Abs, and Robust scaling. Finally, to assess and validate model performances comprehensively, Stratified Cross-Validation was selected to ensure more reliable and unbiased assessments of models’ performances [

38].

3. Results and Discussion

Once the selected features were extracted from all crop fields, the initial phase of analysis focused on evaluating how manure application impacts the visible spectrum in a subset of randomly selected fields. This preliminary examination aimed to identify any observable changes in reflectance within the visible light range that could be attributed to manure application. However, application of manure did not produce distinct changes in the visible spectrum, suggesting that visual spectrum data alone may be insufficient for effective detection. This finding highlights the need to incorporate additional indices that extend beyond the visible spectrum, such as those derived from infrared data.

Figure 4 illustrates this limitation, presenting a few examples.

The next step of the study aimed to identify the spectral features most influenced by manure application on crop fields, as summarized in

Table 1. This process involved calculating each index’s importance using eq.

1, which quantifies the relevance of each spectral index in distinguishing between manured and non-manured fields. Moreover,

p-values were calculated to assess the statistical significance of each index’s response to manure application, as detailed in

Section 2. This analysis was performed on crop fields located in Spain to determine how different spectral indices responded within this specific environmental and agricultural context. The results indicated that most of the spectral indices had

p-values well below the significance threshold of 0.05, suggesting that these indices showed statistically significant differences between fields with and without manure application.

After identifying the spectral features most impacted by manure application, the next step involved examining the temporal trends of a few key indices for a set of randomly selected reference crop fields, all located in Spain. This analysis aimed to observe how these indices fluctuated over time in response to manure application events and to better understand their behavior. The trends are displayed in

Figure 5, which showcase the changes in selected indices across multiple acquisitions for these fields. It is important to note that the values shown in these charts are not the actual raw index values. Instead, each index value has been scaled to a standardized range of -1 to +1, for visualization purposes.

The effects of manure application on crop fields are uneven, with some fields showing more pronounced changes in specific indices than others. This variability can be attributed to differences in soil composition and conditions, and even the timing and rate of manure application, which all influence how strongly these indices respond. Furthermore, these indices naturally fluctuate over the year due to seasonal crop growth, weather patterns, and other environmental factors, meaning that changes in index values are not solely driven by manure applications.

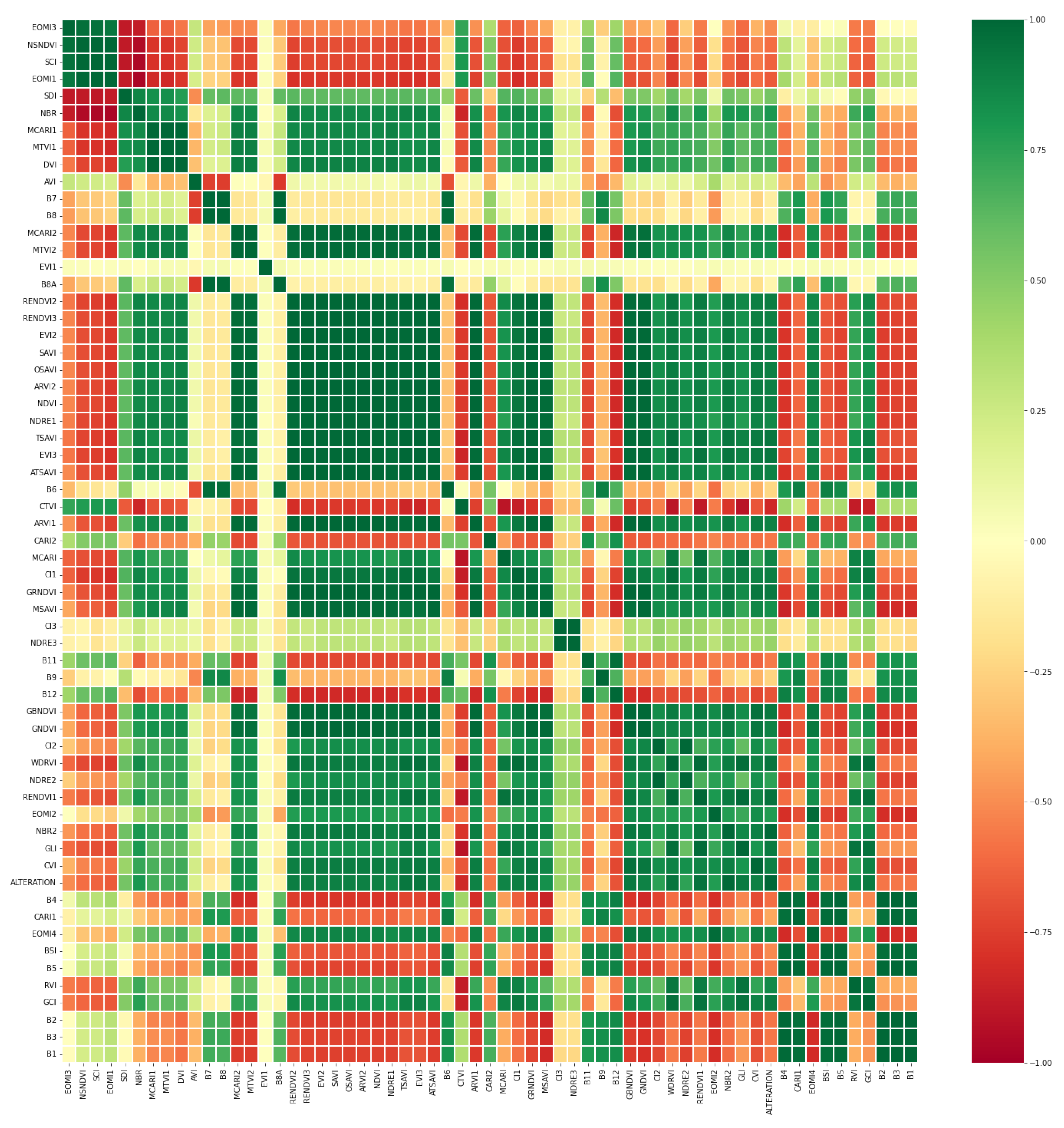

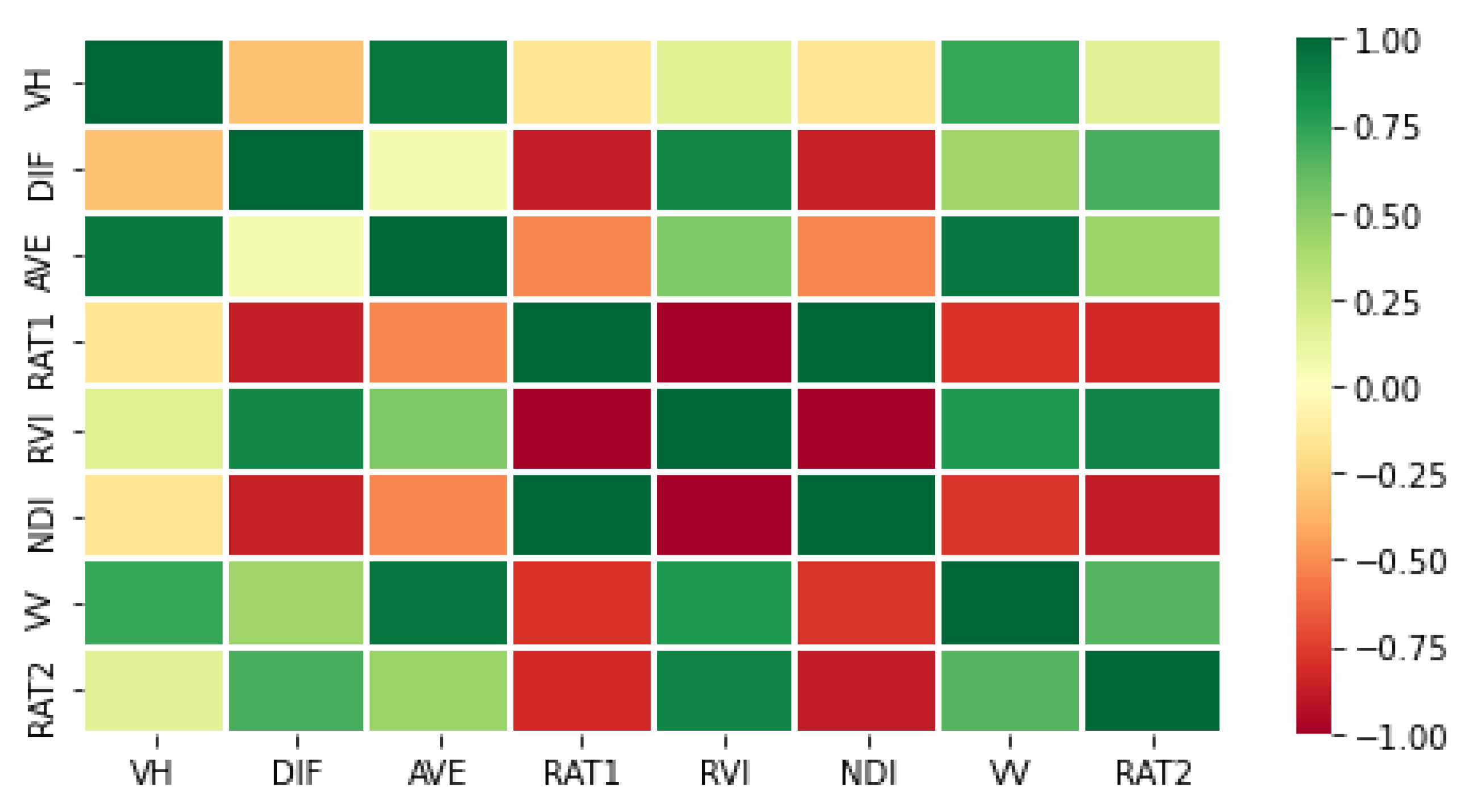

Further analysis indicated that many of the spectral indices examined in this study display significant correlations with each other, as illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7. This correlation implies redundancy if all indices are used simultaneously in the model. However, our model relies not on absolute index values but rather on the differences between consecutive satellite acquisitions for each index. By leveraging temporal changes, the model aims to capture dynamic shifts that occur following manure application, rather than static index values that might be affected by other environmental factors.

The next phase, following this initial analysis of index importance and correlation, is to develop and train the machine learning models using these selected features. These models will be designed to predict manure application events based on the observed changes in index values between two dates. Initially, the model will be tested on Spanish crop fields, the same context from which the training data was derived. Subsequently, the model’s ability to generalize will be tested in Italy, to assess whether it can detect manure application in regions with diverse environmental and agricultural conditions.

After conducting data analysis and balancing the DataFrames to ensure an even representation of manure and non-manure application events, multiple machine learning models were evaluated to determine their effectiveness. This evaluation involved a 5-fold cross-validation approach, which consists of splitting the data into five parts and training the models on four parts while validating on the fifth, rotating through different sets to ensure robust performance testing. Additionally, this process was repeated across different random seeds to further validate the consistency and reliability of the model results. Two main configurations of the models were compared to assess their accuracy in detecting manure applications. The first configuration focused on Machine Learning models trained on specific Sentinel-2 indices, selected for their sensitivity to changes caused by manure application. These indices were chosen based on initial analyses that identified which spectral bands were most impacted by manure presence. The second configuration used features derived from Sentinel-1 SAR data, allowing for a comparative analysis of optical versus radar-based manure detection capabilities. To optimize the models, index normalization was applied to the data, with various scaling techniques tested to ensure that features were appropriately scaled and comparable. Among these techniques, the Max-Abs scaler produced the best results, as determined through a forward feature selection process. This process involved iteratively adding features and assessing their impact on model performance, ultimately identifying the optimal feature set and scaling method to improve detection accuracy.

With the datasets balanced to ensure an equal representation of manure and non-manure events, model evaluation focused on general accuracy as the primary metric. Results showed a clear distinction between the effectiveness of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 data for detecting manure applications. Specifically, spectral indices derived from Sentinel-2 outperformed those derived from Sentinel-1 SAR data in terms of prediction capabilities. For the models based on Sentinel-1 SAR data, accuracy scores for most classifiers were only slightly better than a random classifier, with accuracy ranging between 0.50 and 0.64. This poor performance suggests that C-band radar data did not contain meaningful indicators of manure application, possibly due to radar’s limited sensitivity to the types of changes that manure induces in soil and crop properties. In contrast, models using data from Sentinel-2, which captures reflectance in visible and infrared bands, led to far better performance levels. Among the models tested, Support Vector Classification (SVC) stood out as particularly effective, demonstrating both high accuracy and the ability to generalize well across different data samples. These findings are detailed in

Table 2, which provides a comparative overview of classifier performance across different datasets and configurations.

The next step of the study evaluated the model’s ability to generalize manure application detection across different geographic regions. Specifically, the model, which was initially trained on crop field data from Spain, was tested on crop fields located in Italy. This testing aimed to assess whether the spectral signature of manure application remained consistent in a different geographic and environmental context. Results showed a notable drop in accuracy, decreasing from 90% for the Spanish fields to 83% for the Italian fields. This reduction indicates that while the model retained some predictive capability, its effectiveness decreased significantly when applied to fields outside the region it was trained on. This fact suggest that the spectral signature of manure application is influenced by regional factors, such as soil type, climate, and crop species, which may vary between Spain and Italy. Further insights are provided by the confusion matrix in

Table 3, which shows true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative classifications. The matrix highlights specific areas where the model struggled to correctly identify manure application in the Italian fields, underscoring the need for additional regional data or adaptations to improve cross-regional generalization.

As a validation step, independent models were trained specifically on data from Italian farmland to assess whether region-specific training could improve the model’s performance in detecting manure applications. These Italian-trained models used the same set of features, normalization methods, and cross-validation techniques as those applied to the Spanish farmland models, ensuring consistency in model configuration and evaluation. The training process utilized 5-fold Stratified Cross Validation (K), a method that divides the dataset into five equally sized, stratified subsets. In each fold, one subset is used for validation while the remaining four are used for training, rotating through each subset to ensure that each portion of the data is validated once. Stratification was used to maintain balanced representation of manure and non-manure events across each fold, which enhances the reliability and robustness of the results. Because the Italian dataset was balanced to contain equal representations of both classes, accuracy alone was chosen as the metric for performance comparison, as it provides a straightforward measure of the models’ success rate in distinguishing manure application events.

Table 4 presents the accuracy results, allowing for a direct comparison with the performance of models trained on Spanish data.

As previously discussed, the models trained on Italian farmland demonstrated a reduction in performance compared to the Spanish models when evaluated on the Italian dataset itself. However, the Italian models showed a significant improvement in their ability to generalize to other, unseen Italian farmland. This is particularly evident in the increase in recall for the “manured” class, which increased from 30% to nearly 75%. The substantial improvement in recall suggests that the Italian models were better in recognizing manure applications within the same geographic region, even when tested on different fields. This increase in performance supports the hypothesis that the spectral signature of manure application is regionally consistent, meaning that the model could better detect manure application events within the familiar environmental context of Italian farmland. This consistency may arise from similar soil types, crop varieties, climate conditions, and agricultural practices across the region, which likely result in more uniform spectral responses to manure application. In contrast, the Spanish-trained models performed worse on Italian data, reinforcing the idea that manure’s spectral signature can be influenced by geographical factors. These findings highlight the importance of region-specific model training to enhance detection accuracy, as spectral signatures may differ across areas due to local environmental variations.

To qualitatively evaluate the model’s performance in a broader context within Italy, an additional test was conducted using the DUSAF dataset, which provides comprehensive agricultural land use data. This dataset allowed the model to be assessed on a larger and more varied set of samples, giving insight into its behavior over diverse field types and conditions across Italy. However, as detailed in

Section 2, the DUSAF dataset lacks precise, field-specific records of manure application events. Consequently, the analysis was limited to general statistical observations rather than exact validation of manure application events.

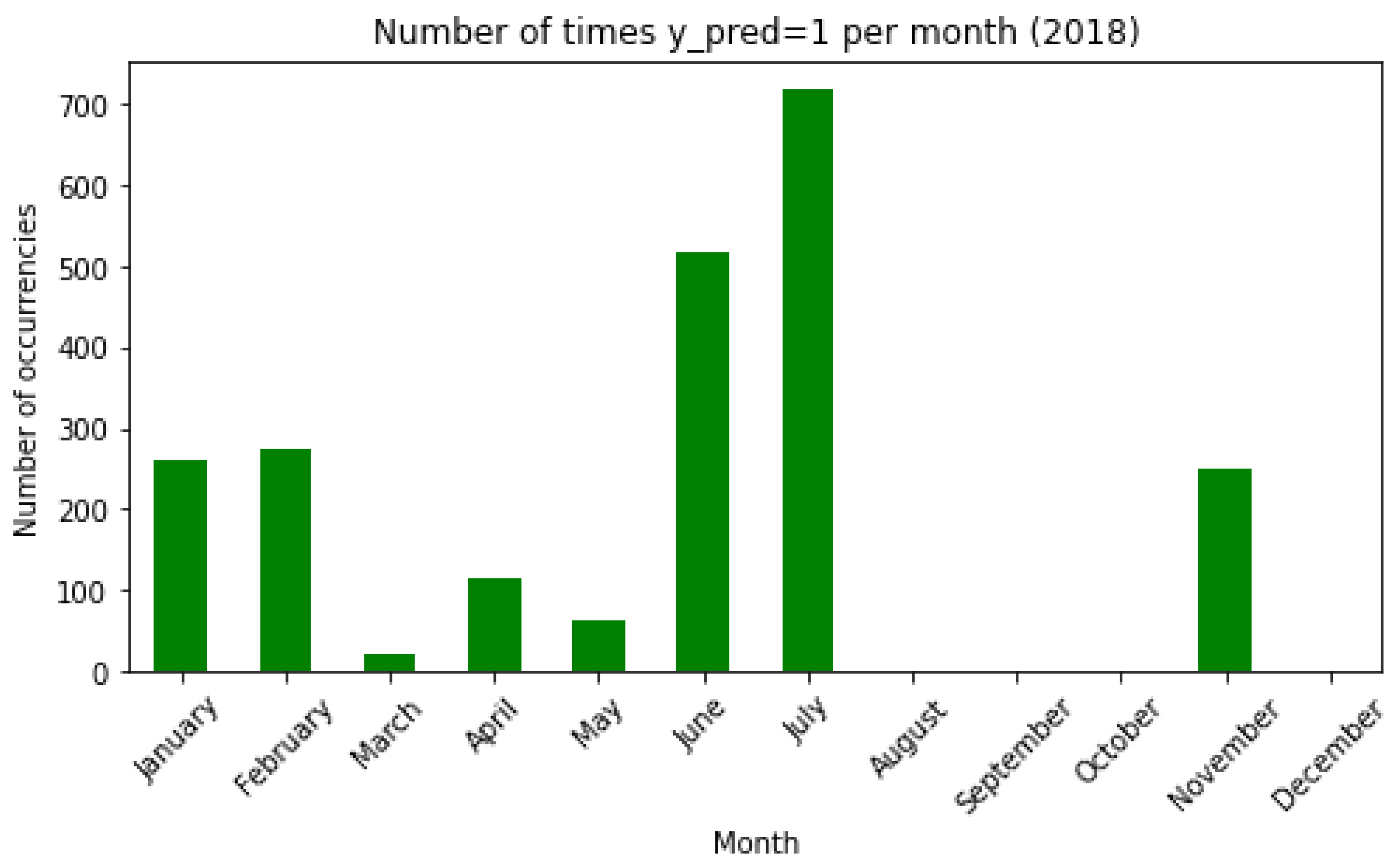

The results obtained based on the DUSAF dataset revealed patterns in manure detection that aligned with seasonal expectations in some cases. As expected, manure application detections were more frequent in spring, which is a typical period for spreading manure to enrich the soil before the growing season. However, the model also detected an unexpectedly high number of manure application cases during the summer months. This was surprising because manure application is less common in summer due to crop growth stages and higher temperatures, which can lead to nutrient volatilization and reduced effectiveness.

Figure 8 illustrates these seasonal detection patterns, highlighting both the expected spring peak and the unusual summer increase in the detected manure events. This discrepancy could be due to environmental factors or spectral characteristics in summer that the model may misinterpret as signs of manure application. Alternatively, it may reflect limitations in the dataset itself, where certain land use or soil conditions trigger false positives in the model.

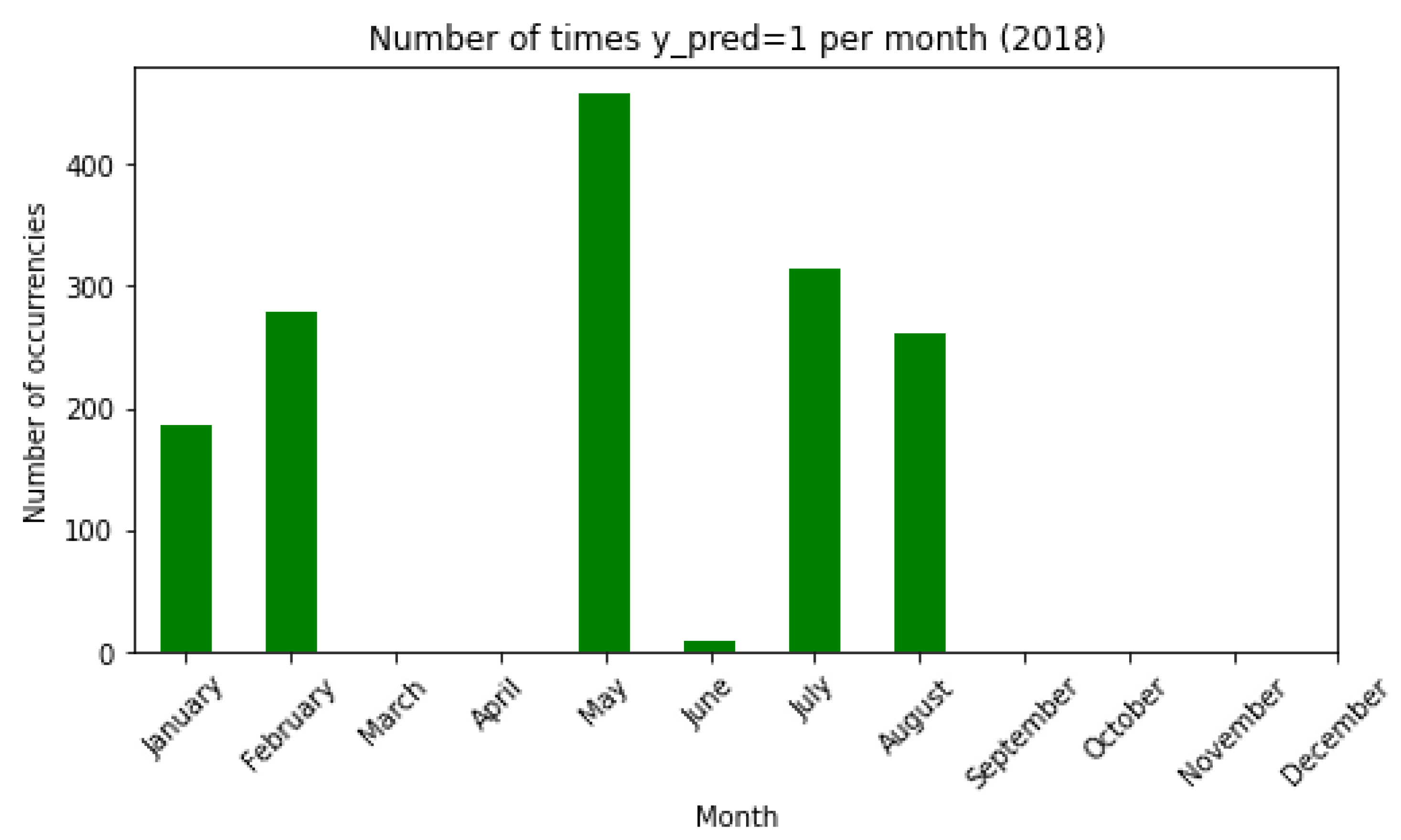

To improve performance, thermal indexes from Landsat-8 were combined with optical ones from Sentinel-2, considering that manure may affect thermal properties. Since temporal sampling was different, each thermal acquisition from Landsat-8 was associated with the nearest Sentinel-2 multispectral acquisition. Notwithstanding the misalignment in temporal sampling among thermal and multispectral inputs, this approach enhanced the model performance in both Spanish (90% to 92% accuracy increase) and Italian context (70% to 82% accuracy increase). Thus, fusing mutispectral and thermal data increased detection rate during the expected spring period, while reducing the number of presumed false positives (

Figure 9).

In summary, combining Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 indexes, despite differences in resolution and band alignment, outperformed using Sentinel-2 alone, highlighting the value of thermal data in this context.

4. Conclusions

In this study we outlined the development and evaluation of a machine learning-based method for detecting manure application in agricultural fields, highlighting its potential as a tool for environmental monitoring and regulatory compliance, particularly with respect to the EU Nitrates Directive. The model demonstrated promising accuracy in identifying manure application events, despite being trained on a relatively limited dataset. These preliminary results indicate that Machine Learning approaches can effectively support remote sensing applications in agriculture, offering insights and a foundation for future enhancements.

One significant finding of our study is that combining optical indices from Sentinel-2 with thermal indices from Landsat-8 improved classification performance, even though the two satellite datasets are not temporally aligned. Additionally, the spectral signature of manure applications showed greater consistency within fields from the same geographical area, underscoring the influence of regional environmental factors, such as soil type, climate, and crop characteristics, on spectral behavior.

Regarding future developments, expanding the study to include manured fields from diverse geographical regions could validate and refine the model’s robustness in varied environmental conditions. Moreover, the involvement of additional spectral indices, particularly those sensitive to organic matter, may further enhance detection accuracy. By incorporating cost-sensitive learning methods, it is possible to address class imbalances and reduce data loss, improving model performance and applicability across larger datasets. Finally, expanding the dataset itself is also essential for training more generalizable models aimed at agricultural monitoring on a larger scale.

Figure 1.

Smallest rectangles encircling all analyzed fields. (Top) Plots located in northern Spain and (bottom) plots located in north-western Italy (CRS: EPSG:4326 - WGS 84).

Figure 1.

Smallest rectangles encircling all analyzed fields. (Top) Plots located in northern Spain and (bottom) plots located in north-western Italy (CRS: EPSG:4326 - WGS 84).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the overall methodology.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the overall methodology.

Figure 3.

Example of (Top) NDVI and (bottom) EOMI2, at a pixel-wise level, calculated near a farmland of interest, represented in black on the leftmost side.

Figure 3.

Example of (Top) NDVI and (bottom) EOMI2, at a pixel-wise level, calculated near a farmland of interest, represented in black on the leftmost side.

Figure 4.

Difference in the visible spectrum considering the Sentinel-2 acquisitions (50m scale) just before (top) and just after (bottom) manure application for three fields (namely - from left to right - P-BIPR3, P-PVPR4, P-PVPR7), identified by a geomarker.

Figure 4.

Difference in the visible spectrum considering the Sentinel-2 acquisitions (50m scale) just before (top) and just after (bottom) manure application for three fields (namely - from left to right - P-BIPR3, P-PVPR4, P-PVPR7), identified by a geomarker.

Figure 5.

Trend of selected Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 indices most impacted by manure application (Spanish context).

Figure 5.

Trend of selected Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 indices most impacted by manure application (Spanish context).

Figure 6.

Correlation between different Sentinel-2 indexes (Spanish context).

Figure 6.

Correlation between different Sentinel-2 indexes (Spanish context).

Figure 7.

Correlation between different Sentinel-1 indexes (Spanish context).

Figure 7.

Correlation between different Sentinel-1 indexes (Spanish context).

Figure 8.

Number of occurrences detected, per month, on the DUSAF daset using Sentinel-2 indexes only.

Figure 8.

Number of occurrences detected, per month, on the DUSAF daset using Sentinel-2 indexes only.

Figure 9.

Number of occurrences detected, per month, on the DUSAF (model combining Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 indexes).

Figure 9.

Number of occurrences detected, per month, on the DUSAF (model combining Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 indexes).

Table 1.

Top 5 Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 indexes most affected by manure application, for crop fields located in Spain.

Table 1.

Top 5 Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 indexes most affected by manure application, for crop fields located in Spain.

| Feature |

Name |

Sensor |

Equation |

Importance |

| EOMI3 |

Exogenous Organic Matter Index 3 |

Sentinel-2 |

|

0.720542 |

| NSNDVI |

NIR-SWIR Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

Sentinel-2 |

|

0.672114 |

| SCI |

Soil Composition Index |

Sentinel-2 |

|

0.661566 |

| EOMI1 |

Exogenous Organic Matter Index 1 |

Sentinel-2 |

|

0.628979 |

| SDI |

SWIR Difference Index |

Sentinel-2 |

|

0.584395 |

| VH |

VH polarization |

Sentinel-1 |

VH only |

0.366449 |

| DIF |

Difference |

Sentinel-1 |

|

0.362870 |

| AVE |

Average |

Sentinel-1 |

|

0.340196 |

| RAT1 |

Ratio 1 |

Sentinel-1 |

|

0.312078 |

| RVI |

Radar Vegetation Index |

Sentinel-1 |

|

0.305876 |

Table 2.

Accuracy of models using best indexes, trained on the Spanish context (left Sentinel-2, right Sentinel-1).

Table 2.

Accuracy of models using best indexes, trained on the Spanish context (left Sentinel-2, right Sentinel-1).

| Model |

Training accuracy |

Test accuracy |

Model |

Training accuracy |

Test accuracy |

| LR |

0.80 |

0.77 |

LR |

0.52 |

0.52 |

| LDA |

0.86 |

0.84 |

LDA |

0.51 |

0.50 |

| SVC |

0.90 |

0.88 |

SVC |

0.67 |

0.64 |

| KNN |

0.82 |

0.80 |

KNN |

0.67 |

0.62 |

| RFC |

0.85 |

0.83 |

RFC |

0.70 |

0.52 |

Table 3.

Confusion matrix of a model trained on Spanish context and tested on the Italian context. Please note that each considered field generates more than one sample, as identification is performed on each adjacent pair of acquisitions.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix of a model trained on Spanish context and tested on the Italian context. Please note that each considered field generates more than one sample, as identification is performed on each adjacent pair of acquisitions.

| |

Predicted |

| |

Not manured |

Manured |

| Actual |

Not manured |

199 |

27 |

| |

Manured |

14 |

5 |

Table 4.

Accuracy of models using best Sentinel-2 extracted indexes, trained on the Italian context.

Table 4.

Accuracy of models using best Sentinel-2 extracted indexes, trained on the Italian context.

| Model |

Train acc. |

Test acc. |

| LR |

0.58 |

0.54 |

| LDA |

0.65 |

0.60 |

| SVC |

0.70 |

0.69 |

| KNN |

0.68 |

0.57 |

| RFC |

0.78 |

0.63 |