1. Introduction

Charcot neuroarthropathy (CN) or osteo-neuroarthropathy has been well described prior to this. This condition is well known to be the sequelae due to poor diabetic control. This condition has left a big loophole in regard to the treatment. The treatment options may be of conservative, operative and even may be resorted to amputation. The complexity of the condition and the known fact of high risk of infection and failure of the treatment has been a financial burden to the healthcare system worldwide.

The pathology that causes CN, somewhat has been laid based upon “Neuro-traumatic theory” and “Neuro-inflammatory theory”[

1]. Despite these theories, the true incidence and prevalence of the CN has not been truly known. In southeast Ireland, prevalence of 0.26%; 40 CN patients out of 15,608 persons with diabetes[

2]. In the East Midlands of England, 0.04%; 90 patients out of 205,033 persons with diabetes were reported to have CN[

3]. Midfoot CN has been reported as the commonest; 59.2%, followed by ankle 22.6%, hindfoot 10% and forefoot 8%[

4]. The incidence of CN is not related to the type of diabetes. 0.1%-7.5% of patients with diabetes have CN, and 29% of peripheral neuropathy in diabetes, has CN[

5].

There are various of classification or descriptions stages have been previously established to identify and group the condition. Eichenholtz orchestrated a temporal based approach and used radiographical and clinical appearance to divide Charcot into different neuropathic stages. The first stage was acknowledged as Prodromal or Stage 0; patients with underlying diabetic neuropathy may present with a minor trauma or sprain of the ankle or foot. The following Stage 2 or Fragmentation stage, whereby it is evidenced with the presence of bony destruction of the joints in the foot or ankle that may result in a laxity or joint subluxation. Stage 3, also described as Coalescence phase, in which the periarticular fracture fragments are being resorbed and new bone formation would be seen in radiographs. Stage 4 was described as a stage of Reconstruction or Resolution, in which the bone becomes more evident and stable with or without unresolved deformity. In the year 1992, Brodsky et al. proposed another classification based on the frequency of occurrence. There were 3 main types were described with the third one had subtypes ‘a’ and ‘b’. His data revealed, 70% of CN was involving the Lisfranc joint and the navicular-cuneiform joints; Type 1. Type 2, with a total of about 20% of the total number of cases involved Chopart joints, subtalar joints and calcaneo-cuboid joints in various combinations. Type 3A involving the ankle joint and Type 3B was involving the calcaneus, collectively about 10%[

6].

Sanders and Frykberg classification, described the distribution of CN based on the anatomical locations or zones on the foot and ankle[

7]. Zone 1 involves the forefoot or the metatarsophalangeal and interphalangeal joint of the foot. Zone 2 involves the tarsometatarsal joints which involves the metatarsal bases, cuneiforms and cuboid. Zone 3 was identified as the Chopart joint or the naviculocuneiform joints. The ankle was labelled as zone 4, which may or may not involve the subtalar joint. Lastly, Zone 5 was the isolated involvement of the calcaneum which commonly due to avulsion of the achilles tendon from the posterior tubercle of calcaneus[

7].

Schon in 1998, further described the midfoot CN based on radiographic anatomical location in the midfoot (types I-IV) and also based on clinical judgement on the severity and collapse of the midfoot (range and stages A-C). Type I, was the Lisfranc pattern where there was involvement of the first to third metatarsocuneiform joints which may progress to fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joints. Type II, naviculocuneiform joints involvement that may progress to the central column at the middle and lateral metatarsocuneiform joints and fourth and fifth cuboid laterally. Type III, the perinavicular pattern, with progress involving the fourth fifth metatarsocuboid joints and eventual calcaneocuboid joints. Type IV, the transverse tarsal pattern, with the greatest deformity described at the talonavicular joint; in both medially and centrally[

8], [

9].

There is no dedicated classification that has been described to elaborate possible deformities or description of bone loss involving the ankle CN. This is probably due to the fact that it is rare with a low level of incidence. Furthermore, there may be lack of knowledge in identifying these conditions early as many may have not encountered it or little experience on diagnosing ankle Charcot, as the incidence rates are only 3-8 per 1000 diabetic population per year[

10], [

11]. We believe it is important to have one, in order to help in terms of transformation of the appropriate information from one medical professional to the other. This would make it easier to understand the stage and preemptively make advanced strategized planning for a patient.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of patients who had been diagnosed with CN was performed. This was a collective pool of patients under the care of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) over a period of 10 years. Most patients had a deformity which was apparent clinically, that altered the hindfoot alignment resulting in gait abnormalities. The clinical findings during follow-ups, serial radiographs in the form of X-rays and CT Scans of the involved ankle and condition related outcomes of these patients were extracted from the clinical case records and our foot and ankle Charcot database.

The patients with a complete radiological and clinical details were included in this study. The follow up time frame was not a factor to be considered in this study, thus no minimum or maximum follow up timeline was required.

A number of 75 ankles were identified, 71 patients with 4 of them had bilateral ankle deformity. In this cohort, 48 male patients and 23 female patients was included. All of the identified patients had been under the follow up with a senior foot and ankle surgeon under the MFT.

The parameters review was based on the coronal and sagittal plane deformity. We also looked for ankle or subtalar joint dislocation or subluxation. In addition to the mentioned, the evident bone loss due to the longstanding or ongoing deformity was evaluated, which was part of the new proposed classification system. The description of bone loss involving the hindfoot region; distal tibia/plafond, talus and calcaneum, is a simple subjective X-ray description. There was no need for quantification of the bone loss in this classification as it would not dictate anything. It is rather to convey a message from one to the other, to provide a rough ideation on the extent of the deformity. We structured a simple alphabetical Ankle Charcot Classification; ABCDEF, which is quite straight forward in terms of understanding and ease of use.

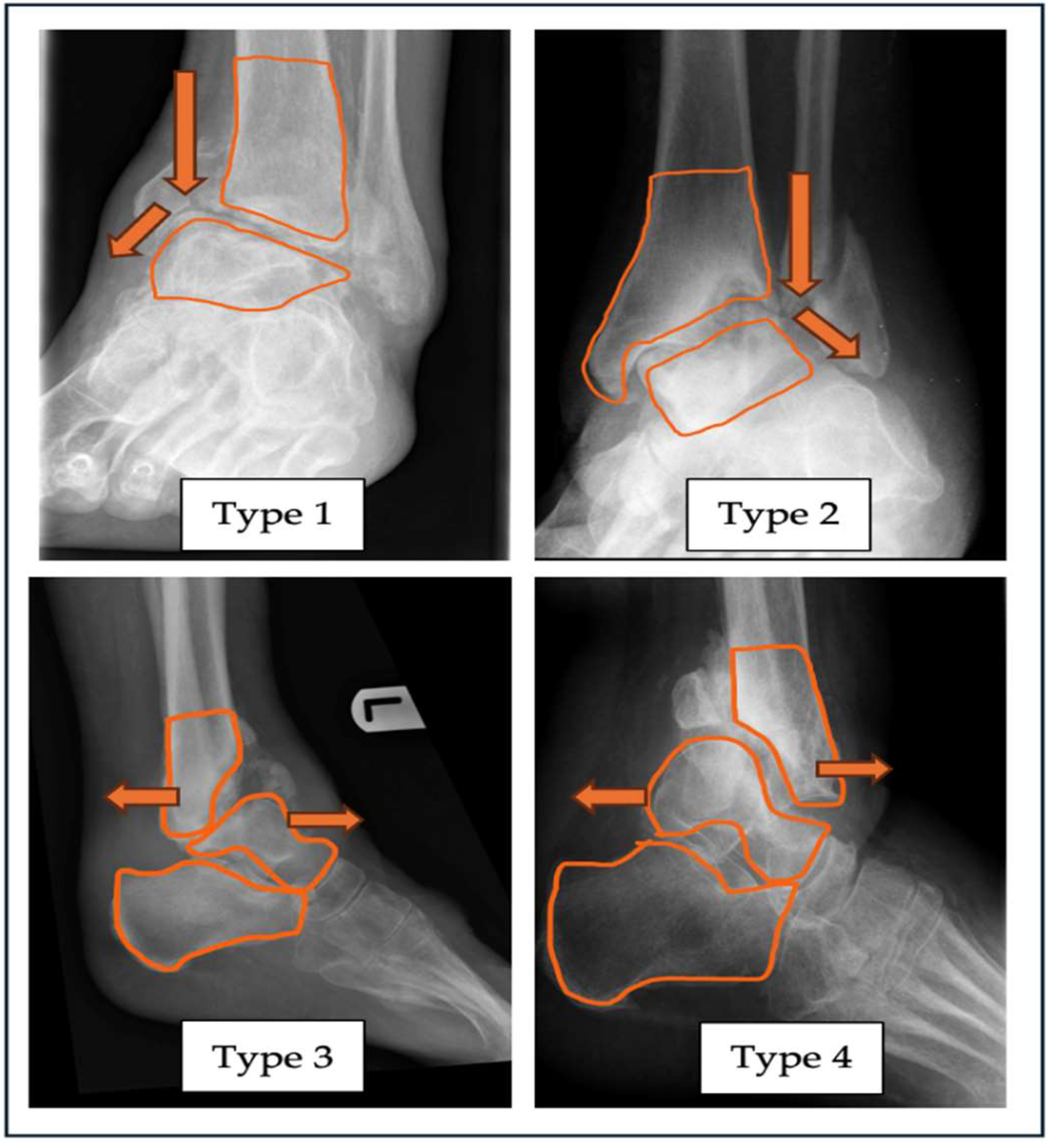

Figure 1.

Radiograph with superimposed illustrations of four different types of alignment deformities related to ankle CN; Type 1-Varus, Type 2-Valgus, Type 3-Anterior angulation, Type 4-Posterior Angulation of the ankle joint.

Figure 1.

Radiograph with superimposed illustrations of four different types of alignment deformities related to ankle CN; Type 1-Varus, Type 2-Valgus, Type 3-Anterior angulation, Type 4-Posterior Angulation of the ankle joint.

To expand the abbreviation, “A” ALIGNMENT is coined for alignment of the ankle joint in coronal; varus (Type 1) or valgus (Type 2) deformity. Sagittal plane deformity can be classified with the plane of either anterior (Type 3) or posterior (Type 4) angulation of the involved joint. Along with the description of the alignment, the observed joint subluxation and dislocation can be included. If the diagnosis of ankle Charcot is confirmed, in the absence of the any alignment deformity, thus it can be classified as Type N (neutral). If any case, a combined deformity with subluxation and/or dislocation, which refers to a multiplanar deformity, it can be classified as Type 5.

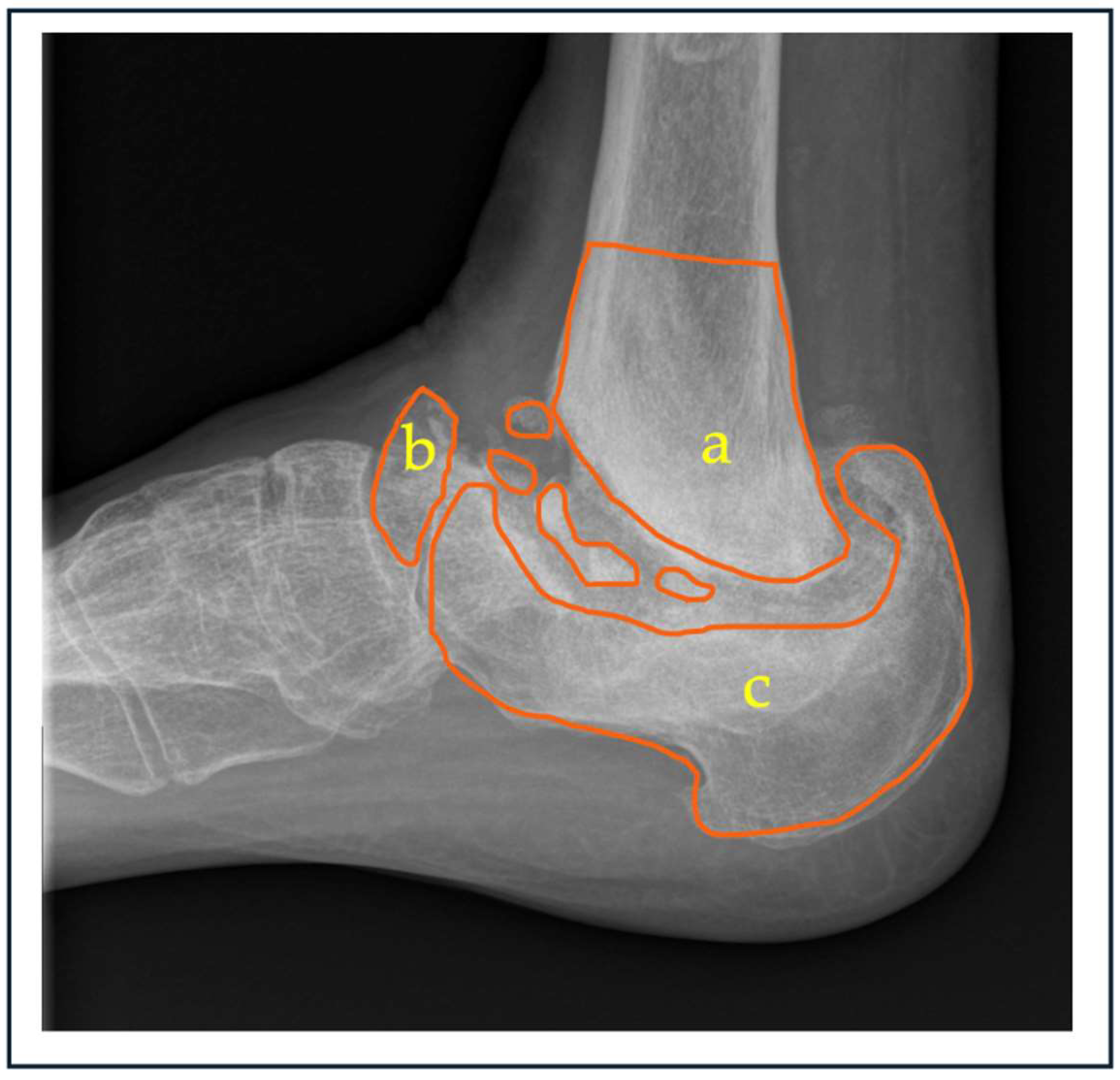

Next, from the proposed classification, “B” BONE STOCK which denotes to the presence of bone loss, subtype a,b,c and d. Subtypes in this category refers to tibia, talus, calcaneum and combined form of bone loss respectively. This can be further dissected and quantified subjectively into groups; mild, moderate and severe based on CT scans.

Figure 2.

Radiograph representing anatomical sites of possible bone loss in ankle charcot, a; distal tibia, b; talus and c; calcaneum. Extent of osseous loss can be varying depending on the chronicity of the condition.

Figure 2.

Radiograph representing anatomical sites of possible bone loss in ankle charcot, a; distal tibia, b; talus and c; calcaneum. Extent of osseous loss can be varying depending on the chronicity of the condition.

The next component, “C” CUTANEOUS refers to the cutaneous or skin condition at the time of the patient is seen. Simplest way of describing this would be as ulcerated or non-ulcerated skin of the involved ankle. Further details which can be included in this category would be the presence of infection or not.

The level diabetic control is labelled as “D” DIABETIC CONTROL. Most of the times when a diabetic patient is treated for Charcot, the underlying disease control are often missed out. The success of a treatment solely depends on the disease control itself. Easiest tool of monitoring would be the levels of glycated hemoglobins; Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). This categorization would be based on HbA1c level either less than 53mmmol/L (7.0%) or more than the mentioned. If the patient falls under the less than category, it would be classified as green, and if more than the accepted values it would be labelled as red.

We have incorporated the Eichenholtz classification; “E” EICHENHOLTZ in our classification system as well. The ankle Charcot can be staged as Stage 0-3, depending at the point of examination of the involved ankle. This would be a guide on the timing and choice of treatment intended depending on the stage of the disease.

The component “F” FOOT PERFUSION refers to perfusion of the foot at the point of examination of the foot. This can be done at outpatient set up, with the hand-held doppler scans. In this classification system, PM refers to pulse-monophasic, PD refers to pulse-diphasic, and PT refers to pulse-triphasic.

A simple example of putting in all the components which was described above, Infected-Dislocated Type 2B PD Stage 3. To expand this, it simply explains an ankle which has the element of infection, with a dislocated or subluxated ankle or subtalar joints, valgus in alignment with bone loss over the talus, pulses are diphasic waves and in the consolidation stage.

Table 1.

M-CAN;Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy Classification System. PM – pulse monophasic, PD – pulse diaphasic, PT – pulse triphasic.

Table 1.

M-CAN;Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy Classification System. PM – pulse monophasic, PD – pulse diaphasic, PT – pulse triphasic.

| “A” - Alignment |

Varus

(Type 1) |

Valgus

(Type 2) |

Anterior

(Type 3) |

Posterior

(Type 4) |

| |

Neutral – label as Type N

Combined Label as Type 5

|

| Dislocation Yes / No |

| “B” - Bone loss |

Tibia

(Subtype a) |

Talus

(Subtype b) |

Calcaneum (Subtype c) |

Combined

(Subtype d) |

| Can further grade the bone loss based on severity – Mild / Moderate / Severe |

| |

*Leave it unlabelled if there are no bone loss present |

“C” - Cutaneous

condition |

|

Ulcerated |

Non-ulcerated |

|

| |

Infected |

|

|

|

| |

Non-Infected |

|

|

|

| |

“D” – Diabetic

Control |

HbA1c < 53 mmmol/L (7.0%) |

HbA1c > 53mmmol/L

(7.0%) |

| NICE guidelines UK 2015 |

“E”- Eichenholtz

Stage |

Stage 0

Prodromal |

Stage 1

Destruction |

Stage 2

Coalescence |

Stage 3

Consolidation |

| “F”–Foot Perfusion (Pulse/Doppler) *Toe pressure can be used as alternative |

Monophasic

(PM) |

Diaphasic

(PD) |

Triphasic

(PT)

|

|

3. Results

Following the detailed review on the ankle X-rays in the anteroposterior (AP), lateral and obliques view we have managed to classify all 71 patients; 75 feet in total. Left sided ankle deformity was 44 and 31 for right sided deformity. MRI scans was used to look at the ankles as well, to stratify and group these patients based on the stage of which they are in, according to the Eichenholtz description. There use of CT scan was helpful in assessing the amount of bone stock, which is helpful in terms of surgical planning.

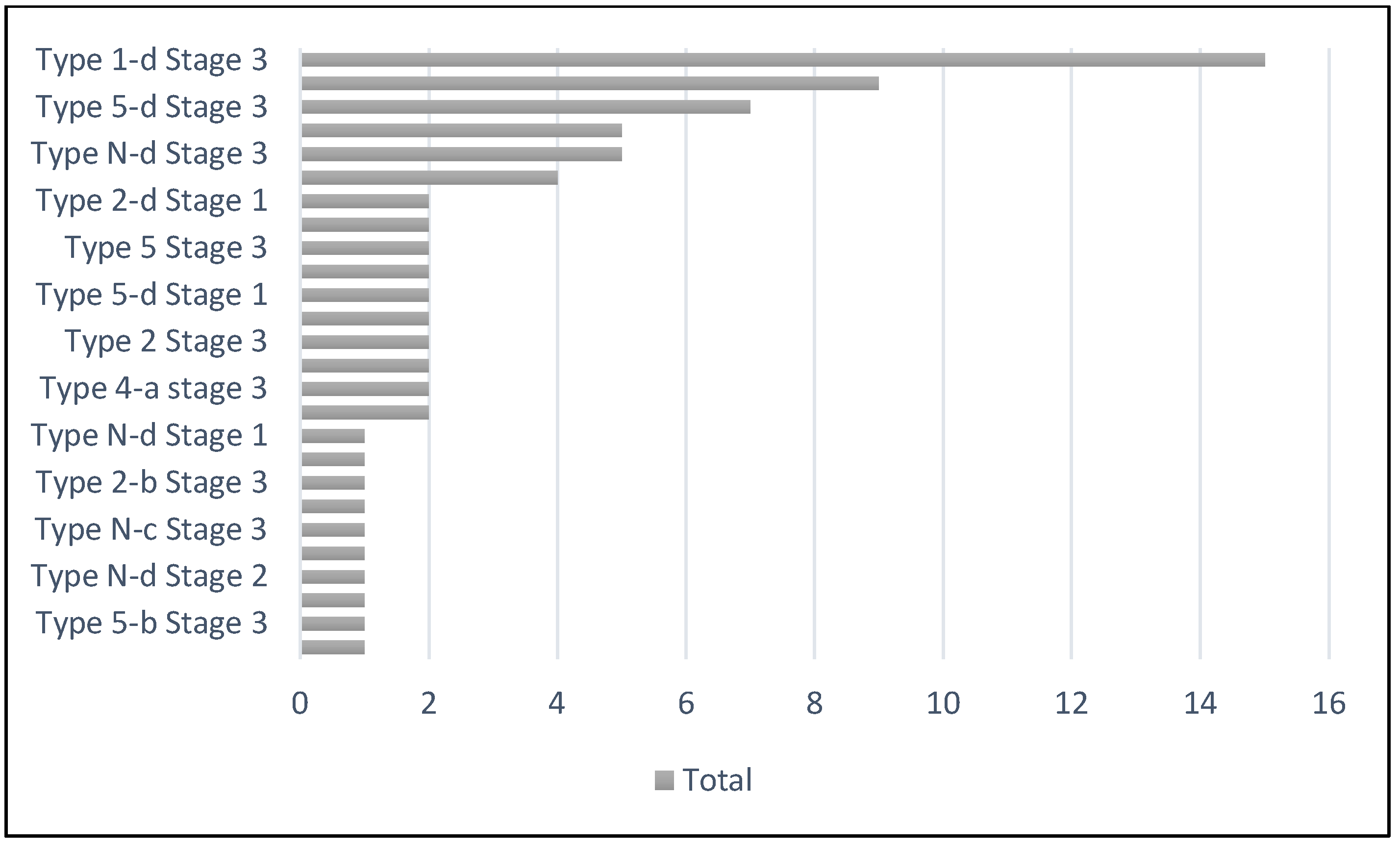

A total number of 15 patients of the entire lot, fell in the classification group of Type 1-d Stage 3. Elaboration to this would be, ankle varus deformity with combined form of bone loss which may be distal tibia-talus or talus-calcaneum. Stage 3, as mentioned earlier refers to the consolidation stage of the Charcot based upon Eichenholtz classification.

Looking further, Type 2-d stage 3 is the second largest in the distribution, accounting nine out of the total number. This is valgus ankle deformity with combined form of bone loss, in the consolidative phase of Charcot. The remainder of the patients fell in numerous other groups as depicted in the chart 1.

Chart 1.

Total number of patients according to the types of deformity and stages of Ankle CN.

Chart 1.

Total number of patients according to the types of deformity and stages of Ankle CN.

The table 2 below shows the count of the number of distal tibia and talus with osteodestruction. This is a combined value, which infers that the patient might have isolated distal tibia osteodestruction, isolated talus osteodestruction or an individual patient might even have a combined distal tibia-talus osteodestruction. Other observed form was talus-calcaneum and distal tibia-talus-calcaneum osteodestruction and other associated in the form of talo-navicular, anterior calcaneal process, posterior calcaneal tuberosity and midfoot Charcot deformity.

Table 2.

Count of total number of patients with bone loss involving distal tibia and talus.

Table 2.

Count of total number of patients with bone loss involving distal tibia and talus.

| |

Count of Tibia bone loss |

Count of Talus bone loss |

| Yes |

49 |

51 |

| Nil |

26 |

24 |

| Grand Total |

75 |

75 |

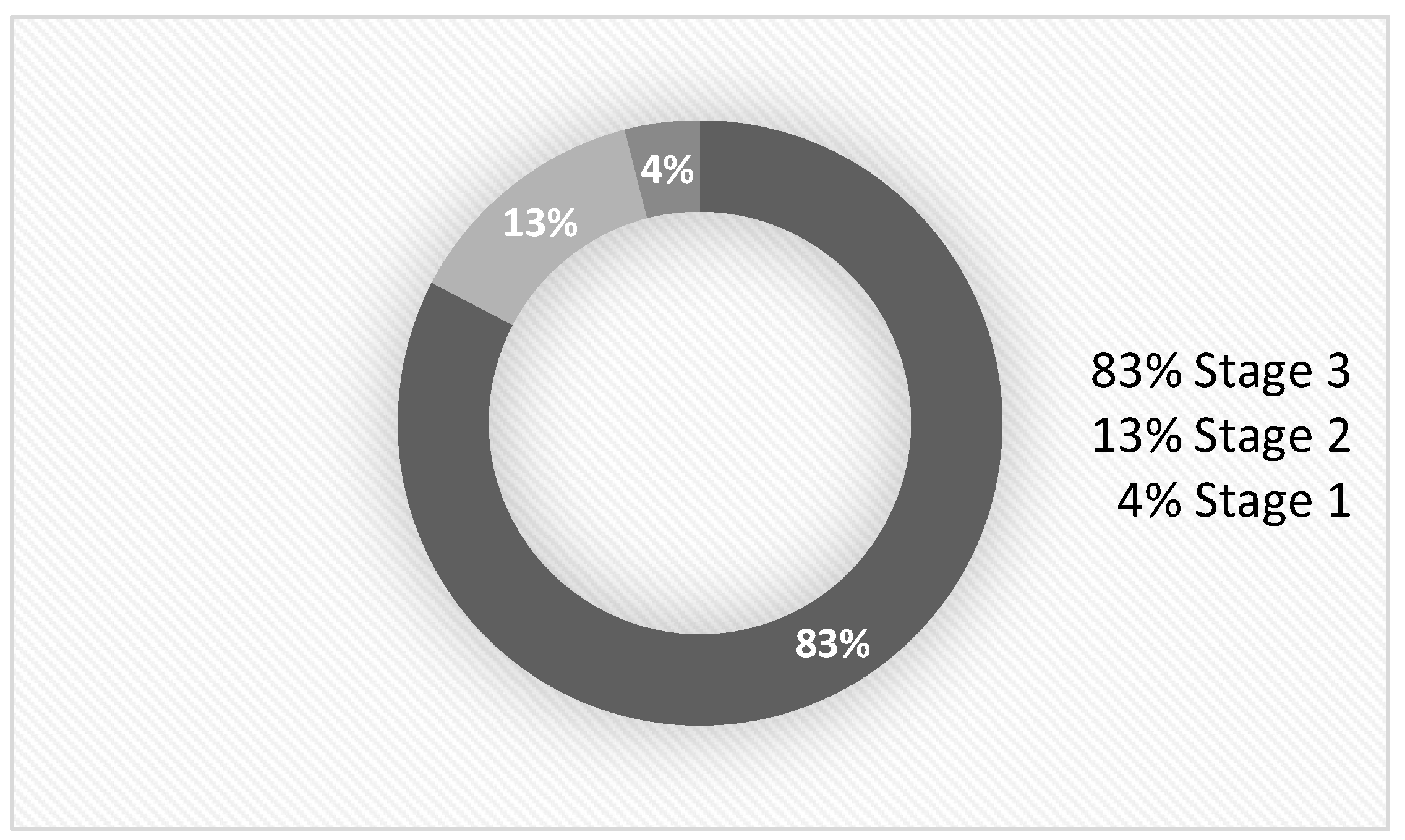

Majority of the patients upon evaluation were in Stage 3 of Eichenholtz stage of charcot; chart 2. A total of 62 patients were reported in this group.

Chart 2.

Distribution of patients in respective stages of Eichenholtz.

Chart 2.

Distribution of patients in respective stages of Eichenholtz.

4. Discussion

Chronic diabetic patients are vulnerable to progress and develop CN in their fifth or sixth decades of their life. It is believed most of them would have been diabetic to start with for at least 10 years before the onset of CN[

5]. Both T1DM and T2DM group of patients, are at risk of fractures. The bending resistance, trabecular stability and stiffness are significantly reduced. The microarchitectural analysis revealed increased cortical porosity with reduced cross sectional bone area and a low trabecular bone score (TBS)[

12]. All the mentioned above are clear evidence to support the fact that diabetics have a very poor bone quality. This reduced bone density would predispose the diabetics with CN to incline towards developing the described deformities based on the nature of force or trauma in the involved ankle.

The lateral ankle ligament complex is known to be the weakest link in terms of providing stability. In the most trivial injuries, the anterior talo-fibular ligament (ATFL) fails which eventually would lead to ankle instability[

13]. In the case of CN, due to the ongoing pathology of repeated inflammation surrounding the ankle, the integrity of the lateral ligament complex if often questionable. This would eventually fail in stability and lead to the varus angulation and further associated osteodestruction will fall in place. This fact again supports our findings which revealed varus ankle angular deformity as the commonest in the case of ankle CN.

The altered ankle stability due to failed ATFL which lead to varus angulation in CN, would predispose to abnormal loading of the talus onto the medial fork of the ankle. Over time, this loading would disintegrate the osseous stability of the weak medial distal tibia or the medial malleolar portion of the ankle. Based on the 3D-CT bone morphometrical analysis, the medial distal tibia has the most porous nature as compared to the lateral distal tibia[

14]. The reduced in density over the medial distal tibia predisposes for a break in the medial wall of the ankle fork. This explains the reason to the commonest deformity of ankle CN, varus ankle. This varus deformity could also result following significant bone loss or resorption of the talus due to prolonged unprotected axial loading at weightbearing, which causes instability of the joint that propagate to further worsened varus angulation.

Physiological hindfoot alignment is a known parameter, which is zero degrees to 5 degrees[

15]. This is in the normal anatomy where the normal ankle works with axial loading. In the case of a CN, this normal hindfoot valgus could be detrimental in long term. With the reduction bone mineral density in diabetics with CN, would predispose for fragility fractures[

12], [

16]. This weakened bone over the medial ankle with the constant normal valgus loading of the hindfoot would eventually lead to insufficiency or fragility fracture of the medial distal tibia or the medial malleolus. Progressively, in the normal nature of the hindfoot valgus, following the fracture of the medial fork, the ankle follows the pattern and result in the valgus deformity as what we found to be the second commonest pattern in our series of patients.

Multivariate investigative methods have been described to diagnose CN. Plain radiographs, CT scans, MRI scans and unlabelled or labelled bone scans are significantly recognised modalities. The above mentioned could facilitate in picking up from earlier stages to the end stages of the disease progression. In terms of preoperative management, the identification of the amount bone loss as mentioned is our classification, both CT scan and MRI scans are relatively important. MRI scans is pivotal in differentiating acute CN from osteomyelitis that may dictate the choice of temporizing or definitive stabilization[

5], [

17]. CT scans would be helpful in later consolidated stages of the disease, that would help in pre-operative planning and treatment staging[

17]. Thus, we had included the amount of bone loss in our classification system, which can be based easily of plain radiographs, or with a more quantitative advanced imaging by means of MRI and CT scans. The ideas is to convey a clear state of the deformity that would help decorate the appropriate plan of management either conservative or surgically.

The idea of including the glycaemic control in (HbA1c) our classification was to incorporate the message of reviewing the current diabetic control in the patient at the present point of time and for subsequent review on the control. It is devastatingly important to achieve a good glycaemic control to control and prevent the progression of diabetic neuropathy, inherently CN. The NICE guideline recommends a HbA1c target 48 mmol/mol (6.5%)[

18]. Those patients with poorer control are predisposed for ulceration with or without infection. Furthermore, poor glycaemic control may hinder or worsen a surgical wound if a surgical method of stabilization was the choice. A study looking in wound healing potential in relation to HbA1c control, suggested that a range between 7.0% and 8.0% would potentiate good wound healing with reduced risks of mortality in diabetic foot ulcers[

19].

Muller et al. elaborated that, existence of peripheral arterial disease would be a direct contributor to delayed or disturbed wound healing in a foot and ankle surgery. Their study recommends that patients undergoing any form of foot and ankle surgery should be evaluated thoroughly pre-operatively and best to obtain the ankle-brachial pressure index prior[

20]. This would. About 40% of patients with CN are likely to have peripheral arterial disease, however this was significantly lower in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. The chances of developing ischaemia in patients with CN is less likely as compared with patients with diabetic foot problems or ulcers[

21]. It is however important to know the arterial status of these patients, as most severe deformities require surgical stabilization, thus the risks of wound complications can be well explained and anticipated.

In this study, there are certain limitations. We have not discussed in detail pertaining the methods of management for each type of the described deformity. There is a need for a more detailed elaboration pertaining the planning of management in each type of deformities. We describe a classification that could help carry the message of the disease from one person to the other. This could make ease the receiving or primary treating surgeon to obtain a brief clarification of what he or she is going to be dealing with. No doubt the management of CN has been a financial burden to the healthcare system worldwide, but an emerging new classification may help in early identification and management of these patients at the earliest and preventing the need for amputations.

In conclusion, developing a new ankle CN classification would be significantly important in the need to handle and manage each cases carefully. The need to understand the patterns of deformity would be elementally important to sketch a management plan, conservatively or surgically. It helps to highlight the deforming forces that need to be address in prevention of worsening of the deformity and skin breakdown. Identifying the osseous loss would help dictate the approach to surgery and the type of fixation required in providing a stable construct.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this paper as it was an audit and review of radiographs and providing a retrospective, observational and a descriptive classification. An approval from the local departmental governance lead was obtained to review and perform this audit on the clinical data, based on pre-existing records.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived in view that there was no contact with patients in any form during the conduct, with ensured data protection following approval from the local departmental governance lead.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- K. A. Cole and D. C. Jupiter, “Charcot neuroarthropathy in diabetic patients in Texas,” Prim Care Diabetes, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Marshall, C. Meyer, M. Hurst, H. Hughes, and P. Burns, “Prevalence of Ankle Charcot Neuroarthropathy Presenting in a Tertiary Care Center,” Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 114–118, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Metcalf et al., “Prevalence of active Charcot disease in the East Midlands of England,” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 1371–1374, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Najefi, R. Brown, and C. Loizou, “Classification and management of the midfoot Charcot diabetic foot,” Orthop Trauma, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 49–55, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. B. Ergen, S. E. Sanverdi, and A. Oznur, “Charcot foot in diabetes and an update on imaging,” Nov. 20, 2013. [CrossRef]

- V. B. Bregovskiy, S. A. Osnach, V. N. Obolenskiy, A. G. Demina, A. L. Rybinskaya, and V. G. Protsko, “CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHARCOT NEUROOSTEOARTHROPATHY: EVOLUTION OF VIEWS AND UNSOLVED PROBLEMS,” Jul. 01, 2024, Russian Association of Endocrinologists. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Rosskopf, C. Loupatatzis, C. W. A. Pfirrmann, T. Böni, and M. C. Berli, “The Charcot foot: a pictorial review,” Dec. 01, 2019, Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Schon, S. B. Weinfeld, G. A. Horton, and S. Resch, “Radiographic and Clinical Classification of Acquired Midtarsus Deformities,” 1998.

- L. C. Schon et al., “The Acquired Midtarsus Deformity Classification System-Interobserver Reliability and Intraobserver Reproducibility,” 2002.

- E. Gouveri, “Charcot osteoarthropathy in diabetes: A brief review with an emphasis on clinical practice,” World J Diabetes, vol. 2, no. 5, p. 59, 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. Galhoum et al., “Management of ankle charcot neuroarthropathy: A systematic review,” Dec. 01, 2021, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- K. Kupai, H. L. Kang, A. Pósa, Á. Csonka, T. Várkonyi, and Z. Valkusz, “Bone Loss in Diabetes Mellitus: Diaporosis,” Jul. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- D. E. Attarian, H. J. McCrackin, D. P. DeVito, J. H. McElhaney, and W. E. Garrett, “Biomechanical Characteristics of Human Ankle Ligaments,” 1985.

- Z. J. Tsegai et al., “Trabecular and cortical bone structure of the talus and distal tibia in Pan and Homo,” Am J Phys Anthropol, vol. 163, no. 4, pp. 784–805, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Pires, C. Lôbo, C. De Cesar Netto, and A. Godoy-Santos, “Hindfoot alignment using weight-bearing computed tomography,” Journal of the Foot & Ankle, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 239–242, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Verdin, G. G. Botek, J. D. Miller, J. D. Kingsley, and D. Plyler, “Association of Anatomical Location of Neuroarthropathic (Charcot’s) Destruction with Age-and Sex-Matched Bone Mineral Density Reduction,” J Am Podiatr Med Assoc, vol. 114, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Andrea B.Rosskopf, Christos Loupatatzis, Christian W. A. Pfirrmann, Thomas Boni, and martin C. Berli, “The Charcot foot: a pictorial review | Enhanced Reader,” Insights Imaging, no. 77, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. P. O’Hare et al., “The new NICE guidelines for type 2 diabetes - a critical analysis,” 2015, ABCD (Diabetes Care) Ltd. [CrossRef]

- J. X. Shumin, W. Yang, H. Lei, X. Shanshan, and Z. Z. Tang, “Reasonable Glycemic Control Would Help Wound Healing During the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers,” Diabetes Therapy, vol. 10. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Müller et al., “Significant prevalence of peripheral artery disease in patients with disturbed wound healing following elective foot and ankle surgery: Results from the ABI-PRIORY (ABI as a PRedictor of Impaired wound healing after ORthopedic surgerY) trial,” Vascular Medicine (United Kingdom), vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 118–123, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Wukich, K. M. Raspovic, and N. C. Suder, “Prevalence of Peripheral Arterial Disease in Patients With Diabetic Charcot Neuroarthropathy,” Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 727–731, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).