Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Vegetable Extracts as Functional Food Ingredients

2.1. Obesity and Hyperglycemia

2.2. Dyslipidemia

2.3. Hypertension, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Pro-Inflammatory State

3. Safety Concerns

4. Technological Aspects

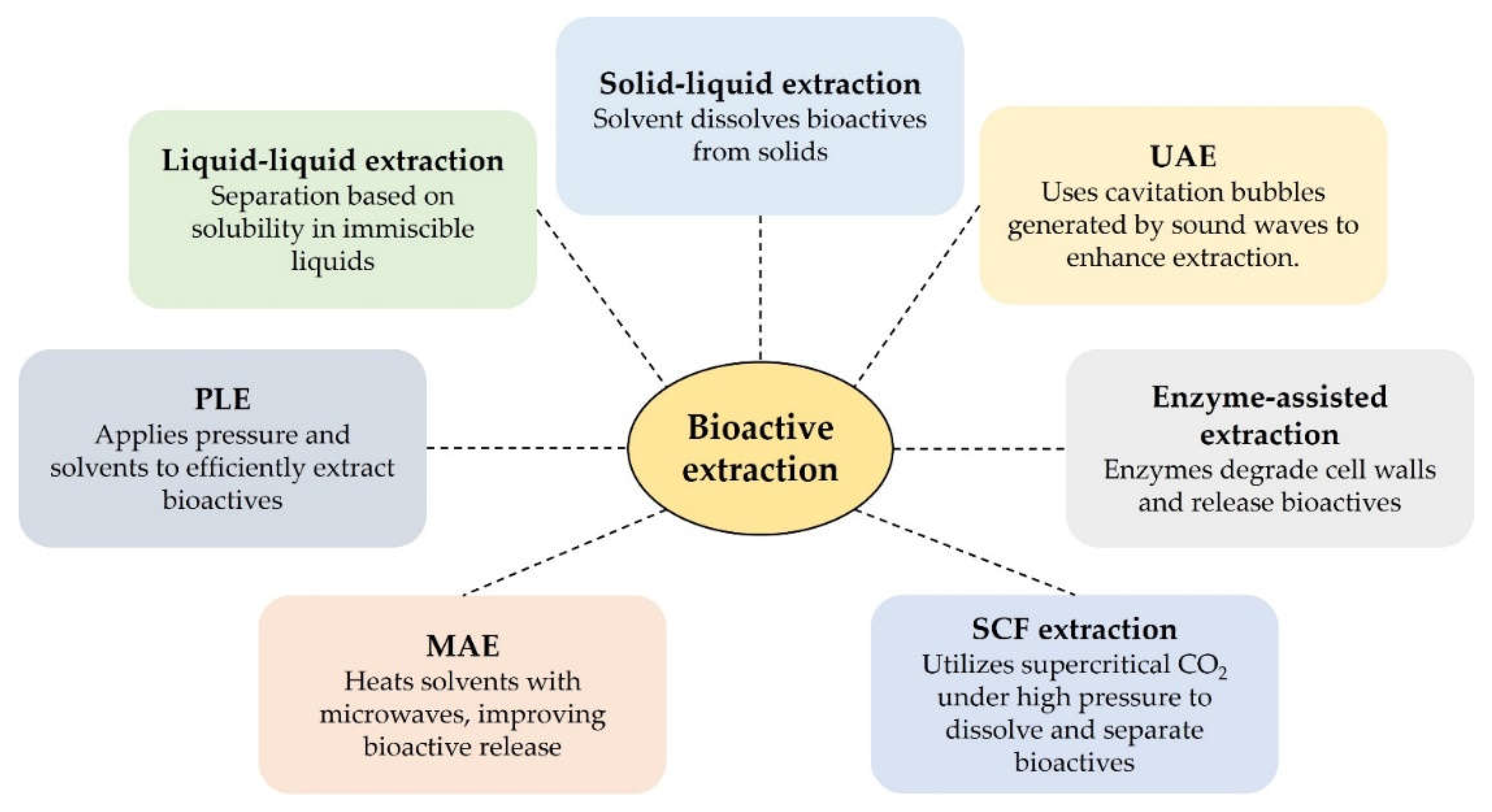

4.1. Extraction Techniques

4.2. Encapsulation and Delivery Systems

4.3. Stabilization and Shelf-Life Improvement

4.4. Vegetable Extracts as Functional Food Ingredients

4.5. Formulation Into Functional Foods, Scalability, and Industrial Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, L.A.; Canani, L.H.; Lisboa, H.R.K.; Tres, G.S.; Gross, J.L. Aggregation of features of the metabolic syndrome is associated with increased prevalence of chronic complications in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2004, 21, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, E.; Monaghan, M.; Sreenivasan, S. Pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Zimmet, P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 1998, 15, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Detection, E. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA, 2001, 285, 2486. [Google Scholar]

- IDF, 2005. International Diabetes Federation: The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Available online: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/Metabolic_syndrome_def.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Belwal, T.; Bisht, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Ullah, H.; Khan, H.; Pandey, A.; Bhatt, I.D.; Echeverría, J. Phytopharmacology and clinical updates of Berberis species against diabetes and other metabolic diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, 2018. Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- WHO, 2019. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- WHO, 2019. Hypertension. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Kaur, J. Assessment and screening of the risk factors in metabolic syndrome. Med. Sci. 2014, 2, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, F.; Helenius-Hietala, J.; Puukka, P.; Färkkilä, M.; Jula, A. Interaction between alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome in predicting severe liver disease in the general population. Hepatology, 2018, 67, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongraw-Chaffin, M.; Foster, M.C.; Anderson, C.A.; Burke, G.L.; Haq, N.; Kalyani, R.R.; Ouyang, P.; Sibley, C.T.; Tracy, R.; Woodward, M.; Vaidya, D. Metabolically healthy obesity, transition to metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1857–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, H.; Ryan, D.A.; Celzo, M.F.; Stapleton, D. Metabolic syndrome: Definition and therapeutic implications. Postgrad. Med. 2012, 124, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rask Larsen, J.; Dima, L.; Correll, C.U.; Manu, P. The pharmacological management of metabolic syndrome. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matfin, G. Developing therapies for the metabolic syndrome: Challenges, opportunities, and... the unknown. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 1, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzad, M.; Negah, R.; Suveer, B.; Neda, R. A review of thiazolidinediones and metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes with focus on cardiovascular complications. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 967–973. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.S.; Chan, E.W.; Wong, A.Y.; Chen, L.; Seto, W.K.; Wong, I.C.; Leung, W.K. Aspirin and risk of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A territory-wide study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasnoor, M.; Barohn, R.J.; Dimachkie, M.M. Toxic myopathies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018, 31, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, M.R.; Bakris, G.L.; Bushinsky, D.A.; Mayo, M.R.; Garza, D.; Stasiv, Y.; Wittes, J.; Christ-Schmidt, H.; Berman, L.; Pitt, B. Patiromer in patients with kidney disease and hyperkalemia receiving RAAS inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. The modification of natural products for medical use. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2017, 7, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.M.; Liu, X.; Izzo, A.A. Trends in use, pharmacology, and clinical applications of emerging herbal nutraceuticals. British J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1227–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Jang, B.H.; Ko, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Park, J.S.; Hwang, E.H.; Song, Y.K.; Shin, Y.C.; Ko, S.G. Herbal medicines for treating metabolic syndrome: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 2016, 5936402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; De Filippis, A.; Khan, H.; Xiao, J.; Daglia, M. An overview of the health benefits of Prunus species with special reference to metabolic syndrome risk factors. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 144, 111574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Daglia, M. Phytonutrients in the management of glucose metabolism. In The Role of Phytonutrients in Metabolic Disorders; Khan, H., Akkol, E., Daglia, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 163–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, H.; De Filippis, A.; Santarcangelo, C.; Daglia, M. Epigenetic regulation by polyphenols in diabetes and related complications. Med. J. Nutrition. Metab. 2020, 13, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, S.; Mazzone, T. Adipose tissue changes in obesity and the impact on metabolic function. Transl. Res. 2014, 164, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M.; Paschke, R. Visceral adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2003, 128, 2319–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lotfy, M.; Adeghate, J.; Kalasz, H.; Singh, J.; Adeghate, E. Chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: A mini review. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2017, 13, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, J.; Dagur, G.; Warren, K.; Smith, N.L.; Khan, S.A. Genitourinary complications of diabetes mellitus: An overview of pathogenesis, evaluation, and management. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2017, 13, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozougwu, J.; Obimba, K.; Belonwu, C.; Unakalamba, C. The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. 2013, 4, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Sommella, E.; Santarcangelo, C.; D’Avino, D.; Rossi, A.; Dacrema, M.; Minno, A.D.; Di Matteo, G.; Mannina, L.; Campiglia, P.; Magni, P.; Daglia, M. Hydroethanolic extract of Prunus domestica L.: Metabolite profiling and in vitro modulation of molecular mechanisms associated to cardiometabolic diseases. Nutrients, 2022, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, L.; Park, H.J.; Lee, D.; Kim, H. Anti-obesity effects of the flower of Prunus persica in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients, 2019, 11, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belwal, T.; Bisht, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Ullah, H.; Khan, H.; Pandey, A.; Bhatt, I.D.; Echeverría, J. Phytopharmacology and clinical updates of Berberis species against diabetes and other metabolic diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Pan, Y.; Xu, L.; Tang, D.; Dorfman, R.G.; Zhou, Q.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, S.; Zou, X. Berberine promotes glucose uptake and inhibits gluconeogenesis by inhibiting deacetylase SIRT3. Endocrine, 2018, 62, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C. Berberine inhibits PTP1B activity and mimics insulin action. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 397, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, B.-S.; Choi, S.B.; Park, S.K.; Jang, J.S.; Kim, Y.E.; Park, S. Insulin sensitizing and insulinotropic action of berberine from Cortidis rhizoma. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, M.; Yan, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, F.; Hu, Z.; Cui, A.; Ma, F.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Q.; Chen, X. Berberine attenuates hepatic steatosis and enhances energy expenditure in mice by inducing autophagy and fibroblast growth factor 21. British J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asekenye, C.; Alele, P.E.; Ogwang, P.E.; Olet, E.A. Hypoglycemic effect of leafy vegetables from Ankole and Teso sub-regions of Uganda: Preclinical evaluation using a high fat diet-streptozotocin model. Res. Sq. [Online ahead of print]. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tucakovic, L.; Colson, N.; Santhakumar, A.B.; Kundur, A.R.; Shuttleworth, M.; Singh, I. The effects of anthocyanins on body weight and expression of adipocyte’s hormones: Leptin and adiponectin. J. Funct. Foods, 2018, 45, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Esposito, C.; Piccinocchi, R.; De Lellis, L.F.; Santarcangelo, C.; Minno, A.D.; Baldi, A.; Buccato, D.G.; Khan, A.; Piccinocchi, G.; Sacchi, R.; Daglia, M. Postprandial glycemic and insulinemic response by a Brewer’s spent grain extract-based food supplement in subjects with slightly impaired glucose tolerance: A monocentric, randomized, cross-over, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients, 2022, 14, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainstein, J.; Ganz, T.; Boaz, M.; Bar Dayan, Y.; Dolev, E.; Kerem, Z.; Madar, Z. Olive leaf extract as a hypoglycemic agent in both human diabetic subjects and in rats. J. Med. Food, 2012, 15, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, R.; Lal, B. Effect of Trigonella foenum-graecum (fenugreek) seeds on glycaemic control and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A double blind placebo controlled study. J. Assoc. Physicians India, 2001, 49, 1057–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.D.; Raghuram, T.C. Hypoglycaemic effect of fenugreek seeds in non-insulin dependent diabetic subjects. Nutr. Res. 1990, 10, 731–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madar, Z.; Abel, R.; Samish, S.; Arad, J. Glucose-lowering effect of fenugreek in non-insulin dependent diabetics. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1988, 42, 51–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fukino, Y.; Ikeda, A.; Maruyama, K.; Aoki, N.; Okubo, T.; Iso, H. Randomized controlled trial for an effect of green tea-extract powder supplementation on glucose abnormalities. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 953–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, M.C.; Hulston, C.J.; Cox, H.R.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Green tea extract ingestion, fat oxidation, and glucose tolerance in healthy humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 778–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.L.; Lane, J.; Coverly, J.; Stocks, J.; Jackson, S.; Stephen, A.; Bluck, L.; Coward, A.; Hendrickx, H. Effects of dietary supplementation with the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate on insulin resistance and associated metabolic risk factors: Randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 886–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T. Pathophysiology of diabetic dyslipidemia. J. Atherosclerosis Thromb. 2018, 25, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chien, S.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yeh, H.-Y. Epidemiology of dyslipidemia in the Asia pacific region. Int. J. Gerontol. 2018, 12, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbikay, M. Therapeutic potential of Moringa oleifera leaves in chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimeur, A.; Ulmann, L.; Mimouni, V.; Guéno, F.; Pineau-Vincent, F.; Meskini, N.; Tremblin, G. The role of Odontella aurita, a marine diatom rich in EPA, as a dietary supplement in dyslipidemia, platelet function and oxidative stress in high-fat fed rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormund, K.; Braun, J.; Rohrmann, S.; Bopp, M.; Ballmer, P.; Faeh, D. Mediterranean diet and mortality in Switzerland: An alpine paradox? Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Saqib, Q.N.U.; Ashraf, M. Zanthoxylum armatum DC extracts from fruit, bark and leaf induce hypolipidemic and hypoglycemic effects in mice-in vivo and in vitro study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wat, E.; Wang, Y.; Chan, K.; Law, H.W.; Koon, C.M.; Lau, K.M.; Leung, P.C.; Yan, C.; San Lau, C.B. An in vitro and in vivo study of a 4-herb formula on the management of diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Phytomedicine, 2018, 42, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasa, V.; Tumaney, A.W. Evaluation of the anti-dyslipidemic effect of spice fixed oils in the in vitro assays and the high fat diet-induced dyslipidemic mice. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Gallegos, E.M.; Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Lucio, J.G.D.; Arias-Rico, J.; Cruz-Cansino, N.; Ortiz, M.I.; Cariño-Cortés, R. In vitro bioaccessibility and effect of Mangifera indica (Ataulfo) leaf extract on induced dyslipidemia. J. Med. Food, 2018, 21, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lellis, L.F.; Morone, M.V.; Buccato, D.G.; Cordara, M.; Larsen, D.S.; Ullah, H.; Piccinocchi, R.; Piccinocchi, G.; Balaji, P.; Baldi, A.; Di Minno, A.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Sacchi, R.; Daglia, M. Efficacy of food supplement based on monacolins, γ-oryzanol, and γ-aminobutyric acid in mild dyslipidemia: A randomized, double-blind, parallel-armed, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients, 2024, 16, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, L.F.; Schneeman, B.O.; Davis, P.A.; Gallaher, D.D.; Waggoner, C.R. Consumption of prunes as a source of dietary fiber in men with mild hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 53, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.H.; Ghasemi, Z.; Sepahi, S.; Rahbarian, R.; Mozaffari, H.M.; Mohajeri, S.A. Hypolipidemic effect of Lactuca sativa seed extract, an adjunctive treatment, in patients with hyperlipidemia: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot trial. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 23, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Bove, M.; Giovannini, M.; Borghi, C. Three-arm, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial evaluating the metabolic effect of a combined nutraceutical containing a bergamot standardized flavonoid extract in dyslipidemic overweight subjects. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2094–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, H.; Ogata, Y. Effect of bitter melon extracts on lipid levels in Japanese subjects: A randomized controlled study. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 4915784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, S.A.; Zhang, R.; Thakur, V.; Reisin, E. Hypertension and the metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2005, 330, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conn, V.S.; Ruppar, T.M.; Chase, J.-A.D. Blood pressure outcomes of medication adherence interventions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, T.; Krause, T.; O’Flynn, N. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Andriolo, V.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food groups and risk of hypertension: A systematic review and doseresponse meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziomalos, K.; Athyros, V.G.; Karagiannis, A.; Mikhailidis, D.P. Endothelial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome: Prevalence, pathogenesis and management. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Vázquez, F.J.; Ibarra-Alvarado, C.; Rojas-Molina, A.; Rojas-Molina, J.I.; Yahia, E.M.; Rivera-Pastrana, D.M.; Rojas-Molina, A.; Zavala-Sánchez, M.Á. Nutraceutical value of black cherry Prunus serotina Ehrh. fruits: Antioxidant and antihypertensive properties. Molecules, 2013, 18, 14597–14612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liman, A.A.; Salihu, A.; Onyike, E. Effect of methanol extract of baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) fruit pulp on NG-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) induced hypertension in rats. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2021, 28, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, S.; Jo, C.; Lee, K.; Ham, I.; Choi, H.Y. Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxant effect of Prunus persica branch on isolated rat thoracic aorta. Nutrients, 2019, 11, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, E.L.; Liu, A.H.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S.; Shafaei, A.; Boyce, M.C.; Wood, L.G.; McCahon, L.; Koch, H.; Sim, M.; Hill, C.R.; Parmenter, B.H. Cruciferous vegetables lower blood pressure in adults with mildly elevated blood pressure in a randomized, controlled, crossover trial: The VEgetableS for vaScular hEaLth (VESSEL) study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, F.R.; Kamkhah, A.F. Antihypertensive effect of Nigella sativa seed extract in patients with mild hypertension. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 22, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, C.; Daou, R.M.; Al Hazzouri, A.; Hamdan, Z.; Ghadieh, H.E.; Harbieh, B.; Romani, M. Garlic and Hypertension: Efficacy, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Implications. Nutrients, 2024, 16, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ried, K.; Frank, O.R.; Stocks, N.P. Aged garlic extract lowers blood pressure in patients with treated but uncontrolled hypertension: A randomised controlled trial. Maturitas, 2010, 67, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhakumar, A.B.; Kundur, A.R.; Fanning, K.; Netzel, M.; Stanley, R.; Singh, I. Consumption of anthocyanin-rich Queen Garnet plum juice reduces platelet activation related thrombogenesis in healthy volunteers. J. Funct. Foods, 2015, 12, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhakumar, A.B.; Kundur, A.R.; Sabapathy, S.; Stanley, R.; Singh, I. The potential of anthocyanin-rich Queen Garnet plum juice supplementation in alleviating thrombotic risk under induced oxidative stress conditions. J. Funct. Foods, 2015, 14, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns Kraft, T.F.; Dey, M.; Rogers, R.B.; Ribnicky, D.M.; Gipp, D.M.; Cefalu, W.T.; Raskin, I.; Lila, M.A. Phytochemical composition and metabolic performance-enhancing activity of dietary berries traditionally used by native North Americans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akindele, A.J.; Adeneye, A.A.; Salau, O.S.; Sofidiya, M.O.; Benebo, A.S. Dose and time-dependent sub-chronic toxicity study of hydroethanolic leaf extract of Flabellaria paniculata Cav.(Malpighiaceae) in rodents. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adewunmi, C.O.; Ojewole, J.A.O. Safety of traditional medicines, complementary and alternative medicines in Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2004, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhitsup, A.; Chen, V.L.; Fontana, R.J. Estimated exposure to 6 potentially hepatotoxic botanicals in US adults. JAMA Netw. Open, 2024, 7, e2425822–e2425822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa Lima, C.M.; Fujishima, M.A.T.; de Paula Lima, B.; Mastroianni, P.C.; de Sousa, F.F.O.; da Silva, J.O. Microbial contamination in herbal medicines: A serious health hazard to elderly consumers. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, C.h.; Zhang, H.; Dong, L.; Chen, S. Heavy metal contaminations in herbal medicines: Determination, comprehensive risk assessments, and solutions. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Tofte, J.I.A.; Mølgaard, P.; Winther, K. Harnessing the potential clinical use of medicinal plants as anti-diabetic agents. Botanics Targets Ther. 2012, 2, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellión-lbarrola, M.C.; Montalbetti, Y.; Heinichen, O.; Alvarenga, N.; Figueredo, A.; Ferro, E.A. Isolation of hypotensive compounds from Solanum sisymbriifolium. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 70, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Khan, M.A.; Arshad, M.; Zafar, M. Ethnophytotherapical approaches for the treatment of diabetes by the local inhabitants of district Attock (Pakistan). Ethnobotanical Leafl. 2006, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, L.M.S.; Escobar, A.; Souccar, C.; Remigio, M.A.; Mancebo, B. Pharmacological and toxicological evaluation of Rhizophora mangle L., as a potential antiulcerogenic drug: Chemical composition of active extract. J. Pharmacognosy Phytother. 2010, 2, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi, S.O.; Akindele, A.J.; Awodele, O.; Anunobi, C.C.; Adeyemi, O.O. A 90 day chronic toxicity study of Nigerian herbal preparation DAS77 in rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, H.K. Ethnopharmacology and systems biology: A perfect holistic match. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijinu, T.P.; Rani, M.P.; Sasidharan, S.P.; Shanmugarama, S.; Govindarajan, R.; George, V.; Pushpangadan, P. Clinical significance of herb–drug interactions. In Nutraceuticals: A Holistic Approach to Disease Prevention; Ullah, H., Rauf, A., Daglia, M., Eds.; De Gruyter: Germany, 2024; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Seden, K.; Dickinson, L.; Khoo, S.; Back, D. Grapefruit-drug interactions. Drugs, 2010, 70, 2373–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.S.; Wei, G.A.N.G.; Dey, L. American ginseng reduces warfarin’s effect in healthy patients: A randomized, controlled trial. ACC Curr. J. Rev. 2004, 13, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Abdul, M.I.; Jiang, X.; Williams, K.M.; Day, R.O.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Liauw, W.S.; Xu, H.; McLachlan, A.J. Pharmacodynamic interaction of warfarin with cranberry but not with garlic in healthy subjects. British J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Malmir, H.; Mirmiran, P.; Shabani, M.; Hasheminia, M.; Azizi, F. Fruit and vegetable intake modifies the association between ultra-processed food and metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joana Gil-Chávez, G.; Villa, J.A.; Fernando Ayala-Zavala, J.; Basilio Heredia, J.; Sepulveda, D.; Yahia, E.M.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Technologies for extraction and production of bioactive compounds to be used as nutraceuticals and food ingredients: An overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Azmin, S.N.H.; Abdul Manan, Z.; Wan Alwi, S.R.; Chua, L.S.; Mustaffa, A.A.; Yunus, N.A. Herbal processing and extraction technologies. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2016, 45, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Sit, N. Extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials using combination of various novel methods: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 119, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.J. Principles of extraction and the extraction of semivolatile organics from liquids. In Sample Preparation Techniques in Analytical Chemistry; Mitra, S., Ed.; Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, USA, 2003; pp. 37–138. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, H.; Omiya, M.; Miki, Y.; Umemura, T.; Esaka, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Teshima, N. Evaluation of the adsorption properties of nucleobase-modified sorbents for a solid-phase extraction of watersoluble compounds. Talanta, 2020, 217, 121052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, S.; Kleeberg, K.K.; Fritsche, J. Recent developments and applications of solid phase microextraction (SPME) in food and environmental analysis—A review. Chromatography, 2015, 2, 293–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Tomao, V.; Virot, M. Ultrasound-assisted extraction in food analysis. In Handbook of Food Analysis Instruments; Otles, S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, 2008; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Jambrak, A.R.; Mason, T.J.; Lelas, V.; Herceg, Z.; Herceg, I.L. Effect of ultrasound treatment on solubility and foaming properties of whey protein suspensions. J. Food Eng. 2008, 86, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.S.; Rao, P.; Rathod, V.K. Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, N.A.; Attan, N.; Wahab, R.A. An overview of cosmeceutically relevant plant extracts and strategies for extraction of plant-based bioactive compounds. Food Bioprod. Process. 2018, 112, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasrija, D.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Techniques for extraction of green tea polyphenols: A review. Food Bioprod. Process. 2015, 8, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, G. Supercritical fluids: Technology and application to food processing. J. Food Eng. 2005, 67, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Naraniwal, M.; Kothari, V. Modern extraction methods for preparation of bioactive plant extracts. Int. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2012, 1, 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, D.; Rekha, B.N.; Gogate, P.R.; Rathod, V.K. Extraction of vanillin from vanilla pods: A comparison study of conventional Soxhlet and ultrasound assisted extraction. J. Food Eng. 2009, 93, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Hong, J.Y.; Chun, H.S.; Lee, S.K.; Min, H.Y. Ultrasonication assisted extraction of resveratrol from grapes. J. Food Eng. 2006, 77, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of five isoflavones from Iris tectorum Maxim. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 78, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Niu, G.; Lio, H. Comparision of microwave assisted extraction and conventional extraction techniques for the extraction of tanshinones from Saliva miltiorrhiza bunge. Biochem. Eng. J. 2002, 12, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huie, C.W. A review of modern sample-preparation techniques for the extraction and analysis of medicinal plants. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 373, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Tripathi, R.; Kamat, S.D.; Kamat, D.V. Comparative study of phenolics and antioxidant activity of phytochemicals of T. chebula extracted using microwave and ultrasonication. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 194–197. [Google Scholar]

- Reverchon, E.; Marco, I. Supercritical fluid extraction and fractionation of natural matter. J. Supercrit Fluids. 2006, 38, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksovski, S.; Sovova, H.; Urapova, B.; Poposka, F. Supercritical CO2 extraction and Soxhlet extraction of grape seeds oil. Bull. Chem. Technol. Macedonia, 1998, 17, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, V.; Gupta, A.; Naraniwal, M. Comparative study of various methods for extraction of antioxidant and antibacterial compounds from plant seeds. J. Nat. Remedies, 2012, 12, 162–173. [Google Scholar]

- Moelants, K.R.; Lemmens, L.; Vandebroeck, M.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Van Loey, A.M.; Hendrickx, M.E. Relation between particle size and carotenoid bioaccessibility in carrot-and tomato-derived suspensions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11995–12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.J.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Charman, W.N. Lipids and lipidbased formulations: Optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W.; Porter, C.J. Formulation of lipid-based delivery systems for oral administration: Materials, methods and strategies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.N.; Amidon, G.L. A mechanistic approach to understanding the factors affecting drug absorption: A review of fundamentals. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 620–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Actis-Goretta, L.; Leveques, A.; Rein, M.; Teml, A.; Schäfer, C.; Hofmann, U.; Li, H.; Schwab, M.; Eichelbaum, M.; Williamson, G. Intestinal absorption, metabolism, and excretion of (-)-epicatechin in healthy humans assessed by using an intestinal perfusion technique. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, G.; Ceyhan, T.; Çatalkaya, G.; Rajan, L.; Ullah, H.; Daglia, M.; Capanoglu, E. Encapsulated phenolic compounds: Clinical efficacy of a novel delivery method. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 23, 781–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Ullah, H.; Martorell, M.; Valdes, S.E.; Belwal, T.; Tejada, S.; Sureda, A.; Kamal, M.A. Flavonoids nanoparticles in cancer: Treatment, prevention and clinical prospects. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 69, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.R.; Botrel, D.A.; Fernandes, R.V.D.B.; Borges, S.V. Encapsulation as a tool for bioprocessing of functional foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 13, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naczk, M.; Shahidi, F. Phenolics in cereals, fruits and vegetables: Occurrence, extraction and analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 41, 1523–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly) phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhilarasi, P.N.; Karthik, P.; Chhanwal, N.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Nanoencapsulation techniques for food bioactive components: A review. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2013, 6, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Bhandari, B. Encapsulation of polyphenols–a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munin, A.; Edwards-Le’vy, F. Encapsulation of natural polyphenolic compounds; a review. Pharmaceutics, 2011, 3, 793–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M. Materials of natural origin for encapsulation. In Handbook of Encapsulation and Controlled Release; Mishra, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2015; pp. 517–540. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, A.; Sousa, A.; Azevedo, J.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Effect of cyclodextrins on the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, H.M.; Elnaggar, Y.S.R.; Abdallah, O.Y. Improved oral bioavailability of the anticancer drug catechin using chitosomes: Design, in-vitro appraisal and in-vivo studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 565, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, J.; Chen, B.; Xi, J.; Long, P.; Zhang, L.; Hou, R. Nanoemulsion delivery system of tea polyphenols enhanced the bioavailability of catechins in rats. Food Chem. 2018, 242, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadari, A.; Gudem, S.; Kulhari, H.; Bhandi, M.M.; Borkar, R.M.; Kolapalli, V.R.M.; Sistla, R. Enhanced oral bioavailability and anticancer efficacy of fisetin by encapsulating as inclusion complex with HPbCD in polymeric nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. 2017, 26, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; Aborehab, N.M.; Abdelhafez, M.M.; Ismail, S.H.; Maurice, N.W.; Azzam, M.A.; Alseekh, S.; Fernie, A.R.; Salama, M.M.; Ezzat, S.M. Anti-obesity effect of a tea mixture nano-formulation on rats occurs via the upregulation of AMP-activated protein kinase/sirtuin-1/glucose transporter type 4 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma pathways. Metabolites, 2023, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanathorn, J.; Kawvised, S.; Thukham-mee, W. Encapsulated mulberry fruit extract alleviates changes in an animal model of menopause with metabolic syndrome. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorado, D.; Fernandez, M.; Orozco, J.; Lopera, Y.; Muñoz, D.L.; Acín, S.; Balcazar, N. Metabolic activity of anthocyanin extracts loaded into non-ionic niosomes in diet-induced obese mice. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreerekha, P.R.; Dara, P.K.; Vijayan, D.K.; Chatterjee, N.S.; Raghavankutty, M.; Mathew, S.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Anandan, R. Dietary supplementation of encapsulated anthocyanin loaded-chitosan nanoparticles attenuates hyperlipidemic aberrations in male Wistar rats. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christman, L.M.; Dean, L.L.; Allen, J.C.; Godinez, S.F.; Toomer, O.T. Peanut skin phenolic extract attenuates hyperglycemic responses in vivo and in vitro. PLoS ONE, 2019, 14, e0214591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, W.C.S.; da Silva, A.A.; Veggi, N.; Kawashita, N.H.; de França Lemes, S.A.; de Barros, W.M.; da Conceiçao Cardoso, E.; Converti, A.; de Melo Moura, W.; Bragagnolo, N. Acute and subacute oral toxicity assessment of dry encapsulated and nonencapsulated green coffee fruit extracts. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.A.; Hameed, A.; Nazir, Y.; Naz, T.; Wu, Y.; Suleria, H.A.R.; Song, Y. Microencapsulation and the characterization of polyherbal formulation (PHF) rich in natural polyphenolic compounds. Nutrients, 2018, 10, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanjiru, J.; Gathirwa, J.; Sauli, E.; Swai, H.S. Formulation, optimization, and evaluation of Moringa oleifera leaf polyphenol-loaded phytosome delivery system against breast cancer cell lines. Molecules, 2022, 27, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbaz, M.U.; Arshad, M.; Mukhtar, K.; Nabi, B.G.; Goksen, G.; Starowicz, M.; Nawaz, A.; Ahmad, I.; Walayat, N.; Manzoor, M.F.; Aadil, R.M. Natural plant extracts: An update about novel spraying as an alternative of chemical pesticides to extend the postharvest shelf life of fruits and vegetables. Molecules, 2022, 27, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabot, G.L.; Schaefer Rodrigues, F.; Polano Ody, L.; Vinícius Tres, M.; Herrera, E.; Palacin, H.; Córdova-Ramos, J.S.; Best, I.; Olivera-Montenegro, L. Encapsulation of bioactive compounds for food and agricultural applications. Polymers, 2022, 14, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouin, S. Microencapsulation: Industrial appraisal of existing technologies and trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Influence of process conditions on the physicochemical properties of açai (Euterpe oleraceae Mart.) powder produced by spray drying. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuck, L.S.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Microencapsulation of grape (Vitis labrusca var. Bordo) skin phenolic extract using gum Arabic, polydextrose, and partially hydrolyzed guar gum as encapsulating agents. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidinejad, A. The road ahead for functional foods: Promising opportunities amidst industry challenges. Future Postharvest and Food, 2024, 1, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, K.; Piskin, E.; Xiao, J.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Fruit juice industry wastes as a source of bioactives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6805–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanakis, C.M. Functionality of food components and emerging technologies. Foods, 2021, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alu’datt, M.H.; Alrosan, M.; Gammoh, S.; Tranchant, C.C.; Alhamad, M.N.; Rababah, T.; Alzoubi, H.; Ghatasheh, S.; Ghozlan, K.; Tan, T.C. Encapsulation-based technologies for bioactive compounds and their application in the food industry: A roadmap for food-derived functional and health-promoting ingredients. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions: An emerging platform for increasing the efficacy of nutraceuticals in foods. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces, 2020, 194, 111202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Encapsulation technique | Definition | Uses | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spray-drying | A method where active ingredients are mixed with a wall material, atomized in a hot chamber, and dried into powder. | Used for shelf-life enhancement and encapsulation of various active compounds. | Low cost, easy scalability, and improved product stability. | Limited number of wall materials can be used. |

| Freeze-drying | Freezing active materials to form ice, followed by sublimation in vacuum to create porous, powdered products. | Encapsulation of temperature-sensitive materials like aromas and volatile oils. | Simple process, preserves sensitive compounds effectively. | Time-consuming and high energy costs. |

| Extrusion | Polymer solution containing active material is extruded through a nozzle into a gel solution. | Used for encapsulating both hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. | Simple, laboratory-friendly, produces high shelf-life capsules. | Difficult and expensive to scale up. |

| Emulsification | Involves creating emulsions of two immiscible liquids (water and oil) stabilized by emulsifiers. | Encapsulation of oil-soluble compounds like dietary fats and sterols. | Provides both liquid and powder encapsulation options. | Requires specific emulsifiers for stabilization. |

| Coacervation | Separation of phases leading to the formation of encapsulated materials within polymeric walls. | High-efficiency encapsulation with controlled release properties. | High encapsulation efficiency and control over material release. | Capsules are often unstable and production cost is high. |

| Molecular inclusion | Based on hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions between polar molecules. | Encapsulation of polar molecules, commonly using cyclodextrins. | Compatible with a wide range of polar compounds. | Limited use outside of specific polar interactions. |

| Ionic gelation | Encapsulation using microbeads in biopolymer gels, formed by methods like spraying or extrusion. | Commonly used for suspending active materials in polymer solutions. | Simple and adaptable to various active materials. | Limited by the biopolymer’s properties and stability in different environments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).