1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction of Research Needs and Research Background

Recent years have witnessed a marked increase in interest regarding the development and application of wearable exoskeletons and robotic limbs. Wearable exoskeletons are increasingly being utilized within industrial and service sectors to mitigate physical exertion and improve operational efficiency. Furthermore, these interventions are integral in the realm of medical rehabilitation, facilitating the restoration of limb mobility in patients who have sustained injuries [

1,

2,

3].Wearable robotic appendages are designed to augment the user with an auxiliary limb, metaphorically referred to as a 'third hand' or 'third leg,' to facilitate the performance of tasks that are challenging to execute unilaterally [

4,

5,

6]. Despite the distinct functionalities of wearable exoskeletons and these robotic limbs, they both necessitate a fundamental criterion: synchronized operation with human users. Wearable exoskeletons must coordinate their kinematics to align with the biomechanics of the human body, and similarly, wearable robotic appendages are required to precisely interpret the user's motor intentions to facilitate effective integration with native limb movements. Attaining the outlined objectives necessitates imperative research into the recognition of human movement intention. The study encompasses the classification of movement patterns, the identification and prognostication of joint kinematics, as well as the recognition and anticipation of distal limb endpoint trajectories [

7,

8,

9].

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) constitutes an intriguing domain with substantial application prospects; however, it is concurrently confronted with various technical challenges:

- (1)

High-caliber, accurately annotated datasets are indispensable for the development of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) models; however, the acquisition of such datasets necessitates considerable time and financial investment. Furthermore, a significant deficiency in the diversity of activities and participant demographics is observed within numerous datasets.

- (2)

Sensor Constraints: Wearable devices equipped with accelerometers and gyroscopes are subject to constraints, notably with respect to energy autonomy, data retention capacity, and communication range. Experimental limitations may impact the feasibility of uninterrupted activity surveillance.

- (3)

Identifying complex or overlapping activities continues to present a formidable challenge within the field. The detection of simple activities such as walking or running is more straightforward; however, the accurate classification of more complex activities that encompass multiple actions or require interactions with objects presents a greater challenge.

- (4)

Real-time processing presents a significant challenge in the implementation of Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems, particularly when aiming for low-latency data processing. The computational requirements of sophisticated algorithms are substantial, and their deployment is further complicated in resource-limited contexts such as mobile devices.

- (5)

Privacy Concerns: The integration of wearable sensors for continuous health monitoring elicits significant concerns regarding the protection of personal privacy. Implementing protocols for the collection, storage, and processing of data that safeguard user privacy is of paramount importance.

1.2. Introduction of Mechanomyography (MMG) and Surface Electromyography (sEMG) in Human Activity Recognition

The application of mechanomyography (MMG) and surface electromyography (sEMG) techniques for identifying human movements has garnered significant attention in recent scholarly works. Studies, such as Shinohara et al. (1997), have established a direct correlation between the MMG signals from the quadriceps and the intensity of physical exertion during intense cycling tests. Sahin et al. (2012) applied wavelet analysis to raw EMG signals to enhance feature extraction, facilitating the classification of these signals through a multilayer perceptron neural network and Bayesian discrimination methods. Balbinot et al. (2013) constructed a neuro-fuzzy model that interprets myoelectric signals captured via surface electrodes to delineate arm motion patterns. Kainz et al. (2014) proposed a method for tracking hand movements and recognizing gestures that combined SEMG with depth-sensing video technology. Frank et al. (2019) achieved effective human-robot collaboration in hazardous settings by integrating surface EMG with data from wearable inertial sensors. Moin et al. (2020) described a portable EMG biosensing device equipped with adaptive machine learning algorithms for the detection of hand gestures. Jaramillo-Yánez et al. (2020) performed an extensive review of the literature concerning the use of EMG data and machine learning algorithms for the real-time identification of hand gestures. Sheng et al. (2021) unveiled a multi-sensory system that integrates sEMG, NIRS, and MMG to create a resilient human-machine interface that remains unaffected by muscle fatigue [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Comparison of two signals:

- (1)

Sensitivity to Different Aspects:

Electromyography (EMG) exhibits heightened sensitivity to the electrical activity correlates with muscle activation, providing a direct measure of the neural stimulation impinging upon the muscle. MMG exhibits a heightened sensitivity to the mechanical characteristics of the muscle, encompassing parameters such as stiffness, elasticity, and the magnitude of force generated.

- (2)

Complementary Use:

The concurrent utilization of EMG and MMG serves to afford a more integrated and detailed insight into the physiological dynamics of muscle function. EMG is capable of delineating the timing of muscle activation, whereas MMG provides insight into the alterations of a muscle's mechanical properties throughout the contraction phase.

- (3)

Ease of Use:

EMG, especially the needle EMG variant, necessitates a more elaborate preparation and precise calibration process, which may pose increased technical challenges. MMG configurations typically exhibit simplified installation and operational procedures, particularly when integrated with contemporary accelerometer-based platforms.

In conclusion, although EMG remains the benchmark for assessing muscle activation and is extensively employed across numerous domains, MMG presents a non-invasive methodology that yields significant revelations regarding the mechanical dynamics of muscular activity. The determination to utilize either option, or the combined application of both, is contingent upon the particular research inquiry or the specific clinical requirement.

1.3. Introduction of Regression Algorithm in Human Activity Recognition

Recent years have witnessed substantial progress in the domain of human activity recognition, with a particular emphasis on the application of time series regression algorithms for the analysis of data captured by body-mounted sensors. Trabelsi et. al. in 2012 developed an unsupervised methodology that employed Multiple Hidden Markov Model Regression (MHMMR) for the analysis of three-dimensional acceleration data, with the objective of recognizing various activities. Chamroukhi et. al. in 2013 delved into the concurrent segmentation of multivariate time series data by employing hidden process regression, aiming to refine the accuracy of human activity recognition processes. Trabelsi et al. in 2013 introduced an unsupervised methodology that employs Hidden Markov Model (HMM) regression for the automated recognition of activities utilizing raw acceleration data. In 2016, the problem of human activity recognition was reframed as a joint segmentation task for multidimensional time series, Safi et. al. employed Hidden Markov Model Regression (HMMR) in conjunction with an expectation-maximization algorithm. The findings of these investigations underscore the critical role of regression algorithms in achieving precise and computationally efficient human activity recognition. On a different note, Seto et. al. in 2015 concentrated on the classification of multivariate time series for the purpose of human activity recognition, employing Dynamic Time Warping template selection methodology. The research highlighted a deliberate approach to minimize the intricacies associated with feature extraction processes. Additionally, Sikder et. Al in 2017 developed an innovative log-sum distance metric to assess discrepancies among sequences of positive integers, subsequently employing this measure for the monitoring and identification of human activities through the analysis of motion sensor data. Trelinski et al. in 2020 introduced an aggregation of multi-channel Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) designed for multi-class time-series classification, with a particular emphasis on depth-based human activity recognition. This study delineates the progressive development of algorithms designed to analyze multivariate time series data, with a specific focus on their application within the domain of human activity recognition. Subsequently, Qi et al. in 2020 introduced an adaptive recognition and real-time monitoring system designed for the detection of human activities, featuring an unsupervised online learning algorithm which operates without the dependency on predefined class constraints. The comprehensive review of the literature elucidates the variety of methodologies and algorithms currently under development for the recognition of human activities through the application of time series regression techniques. This underscores the critical necessity for ongoing innovation within this domain, as documented across multiple studies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Human motion intention recognition is a critical area of research with applications in robotics, prosthetics, human-computer interaction, and rehabilitation. Despite significant progress, there are several challenges and limitations that researchers continue to face. Here are some of the key shortcomings in the field:

- (1)

Data Quality and Availability

In the realm of human motion analysis, data variability is a significant consideration, influenced by inter-individual anatomical discrepancies, physiological variations, and distinct kinematic patterns. The observed inter-individual variability poses a significant challenge for the creation of models capable of achieving robust generalizability across diverse user populations.

- (2)

Sensor Limitations

Invasive vs. Non-invasive sensors offer an alternative to invasive counterparts, such as intramuscular electromyography (EMG), which, while delivering high-fidelity data, are impractical for continuous, daily application due to their intrusive nature.Non-invasive sensor technologies, such as surface electromyography (sEMG) and accelerometers, offer enhanced user convenience; however, they are susceptible to signal interference from noise and cross-talk artifacts.

Optimal sensor positioning and precise calibration are fundamental to ensuring the integrity and reliability of data acquisition processes. Nevertheless, the execution of these procedures is characterized by substantial temporal demands and necessitates specialized knowledge that may not be universally accessible across various environments.

- (3)

Algorithmic Challenges

Feature extraction entails the intricate process of deriving significant attributes from the unprocessed data captured by sensors. Subtle discrepancies in distinct movements can be challenging to discern, which consequently may result in inaccuracies during the recognition of intended actions.

Real-time processing of sensor data is critical for the functionality of numerous applications, including the precise control of prosthetic limbs and exoskeletal systems. Real-time algorithms must meticulously equilibrium precision with computational efficiency, a task that presents considerable difficulties.

Generalization of Models: It has been observed that models, having been well-trained on discrete tasks or tailored to specific individuals, frequently exhibit suboptimal generalization capabilities when faced with novel tasks or applied to different user populations. The limited generalizability of numerous existing systems constrains their applicability in practical scenarios.

- (4)

User Variability and Adaptation

Individual variation is a hallmark of human motor patterns, with each subject exhibiting distinct kinematic profiles that are subject to temporal fluctuations. These fluctuations may arise from a variety of influences, including but not limited to fatigue, injury, or the process of learning. Adapting to such modifications represents a complex challenge for systems.

Users are required to acquire proficiency in manipulating the system, concurrently, the system must possess the capability to acclimate to the dynamic behavioral patterns of the user. The bidirectional learning mechanism is characterized by its complexity, necessitating the employment of advanced algorithmic strategies.

- (5)

Contextual Understanding

Environmental Variables: The operational context of the user can profoundly influence the fidelity and subsequent interpretation of sensor data quality. For instance, the functionality of sensors can be adversely affected by various environmental factors, including electromagnetic interference, ambient temperature, and relative humidity.

The task complexity associated with inferring intentions is significantly reduced in simple, controlled settings, as compared to the challenges encountered within intricate and dynamic contexts. Contemporary systems frequently encounter challenges when addressing the context-dependent characteristics inherent to human movement.

To surmount the encountered challenges, a comprehensive strategy that integrates multidisciplinary expertise is essential. This strategy necessitates the amalgamation of cutting-edge developments in sensor technology, the application of machine learning algorithms, insights from biomechanical research, and principles of human-centered design. Sustained investigation and interdisciplinary cooperation are imperative for surmounting the current constraints and propelling advancements in the domain of human motion intention recognition.

1.4. Introduction of Mechanomyography Extraction

Mechanomyography (MMG) signals have been successfully applied across a diverse range of fields in recent years [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Nevertheless, the measurement of MMG may be susceptible to interference from gesture artifacts and gravitational influences. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of MMG signals and to broaden the scope of their application, it was imperative to eliminate gesture artifacts and high-frequency noise from the recorded data. In previous investigations, three distinct methodologies have been employed to reduce gesture artifacts [

32,

33].

- (1)

Utilize microphone sensors to collect MMG signals

The employment of microphone sensors for the acquisition of MMG is advantageous, as it mitigates interference from gesture artifacts and gravitational acceleration effects. The frequency response of the microphone sensor within the 10-50Hz range exhibited non-linear characteristics, which consequently led to the infiltration of external sound noise into the MMG signals.

- (2)

Reduce limb movements during the experiment

In certain studies, including investigations into myocardial mechanics through the analysis of MMG signals and assessments of quadriceps strength in relation to MMG signals, the researchers constrained the amplitude of limb movements. Such constraints were extraneous to the objectives of our experimental protocol. The established thresholds are not applicable within the context of dynamic human activities.

- (3)

Remove gesture artifact by filter

To mitigate the inevitable presence of gesture artifacts in dynamic human gesture research, it is conventional to employ filtering techniques for their removal in industrial applications. Commonly utilized filters include Butterworth bandpass filters and wavelet bandpass filters. During the preprocessing of the raw acceleration (ACC) signal, bandpass filters were applied to eliminate certain low-frequency components[

34,

35,

36].The empirical mode decomposition (EMD) algorithm has been extensively employed for the processing of nonlinear and non-stationary signals. EMD, however, is prone to the influence of extraneous noise, which can precipitate issues such as modal aliasing and the emergence of spurious modes[

37,

38,

39].

Mechanomyography (MMG) represents an intriguing area of research with substantial promise; however, it confronts numerous obstacles related to the extraction of signals.

- (1)

Signal integrity within Myoelectric signals, specifically those categorized as Multi-channel MMG signals, is frequently compromised by the presence of noise. This noise contamination is attributable to a multitude of variables, including but not limited to, the displacement of skin, the positioning of sensors, and the transmission of ambient vibrations. The difficulty in acquiring pristine and dependable data is thereby heightened.

- (2)

Sensitivity Variability in MMG Sensors: Variations in the sensitivity of MMG sensors can introduce discrepancies during the data acquisition phase. High amplitude sensitivity is essential for the detection of minute muscle vibrations; however, this elevated sensitivity may concurrently augment the levels of noise encountered.

- (3)

The current literature demonstrates a deficiency in standardized methodologies for the collection and subsequent analysis of MMG data. This absence of uniform protocols presents a significant obstacle to the comparative assessment of findings among disparate studies.

- (4)

Data interpretation: The analysis of myoelectric manifestations of gastrocnemius activity necessitates the deployment of advanced algorithms and computational models, which currently remain in the phase of active refinement and development. The intricacy associated with the coordination of muscular movements contributes significantly to the challenge encountered in this domain.

- (5)

Integration of MMG Measurement Modalities with Complementary Sensing Techniques: The amalgamation of Mechanomyography (MMG) with additional sensing modalities, such as electromyography (EMG) or accelerometry, enhances the breadth of physiological insights obtained. However, this concatenation of data streams necessitates sophisticated methodologies for data integration and subsequent analysis, thereby increasing the complexity associated with data fusion and interpretive processes.

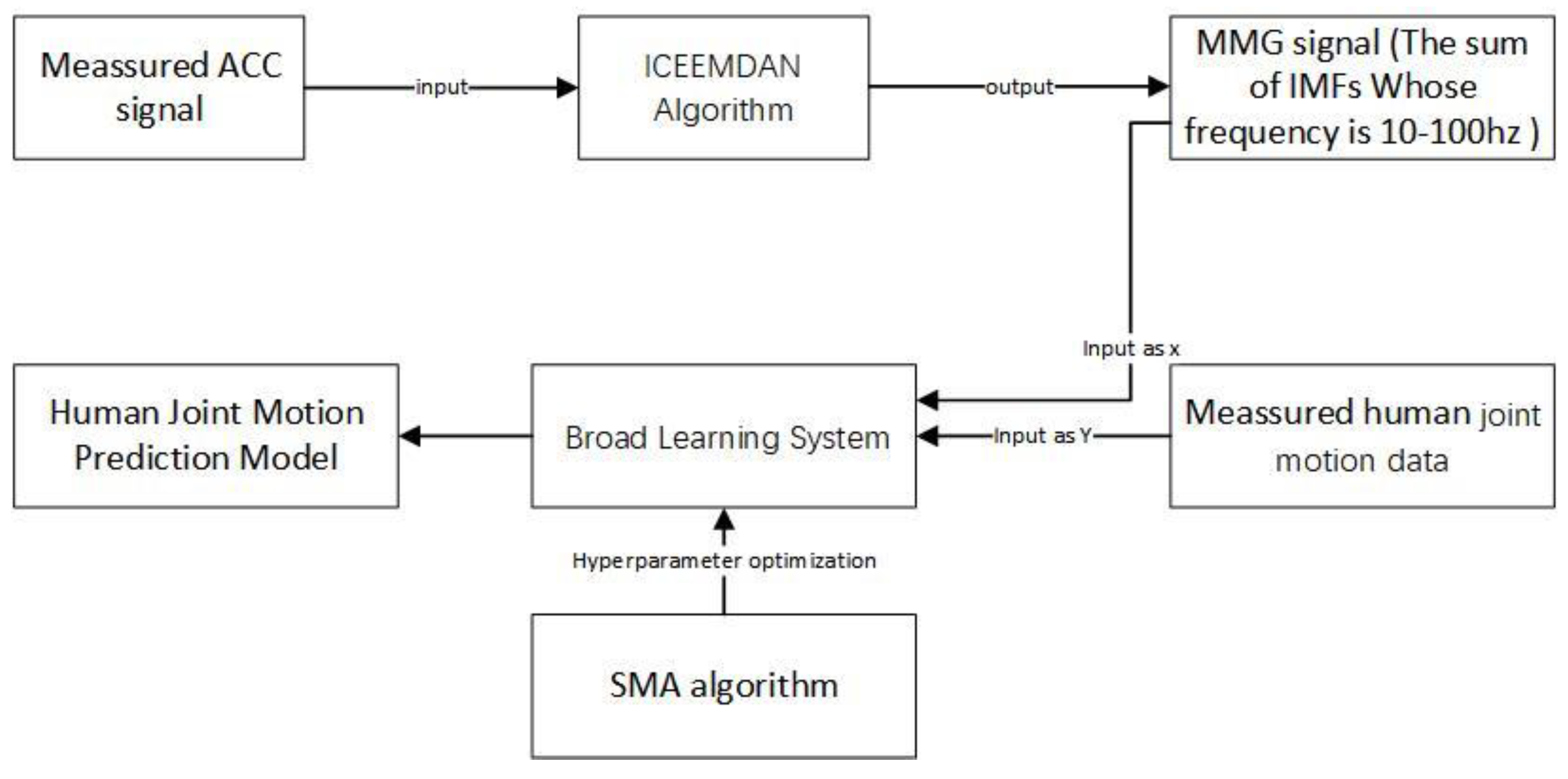

1.5. Introduction of This Research

In the present study, the Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (ICEEMDAN) algorithm [

40,

41,

42,

43] was employed for the extraction of MMG signals. Analysis of the envelope entropy revealed that the ICEEMDAN algorithm is superior in attenuating random noise present within MMG signals compared to conventional methods. Furthermore, a novel approach for estimating joint rotation angles has been introduced, utilizing the Broad Learning System. The parameters of this model were fine-tuned through the application of the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. The implementation of the SMA-BLS algorithm has significantly augmented the generalization capabilities of the joint angle prediction model, concurrently enhancing the model's training efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Process

The experiment starts on January 2, 2024 and ends on January 5, 2024. From January 2 to January 5, 2024, the data were accessed for research purposes and authors had access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection. 12 participants volunteered for inclusion in the study. All participants were fully informed regarding the nature of the research and provided informed consent prior to the commencement of the experimental protocol. In the present investigation, participants performed the consistent-speed arm front raise, elbow curl, and arm side raise exercises. Concurrently, MMG for the anterior deltoid, middle deltoid, posterior deltoid, and biceps were recorded. To enhance the amplitude of the MMG signals, subjects were instructed to hold a 2 kg weight throughout the exercises.

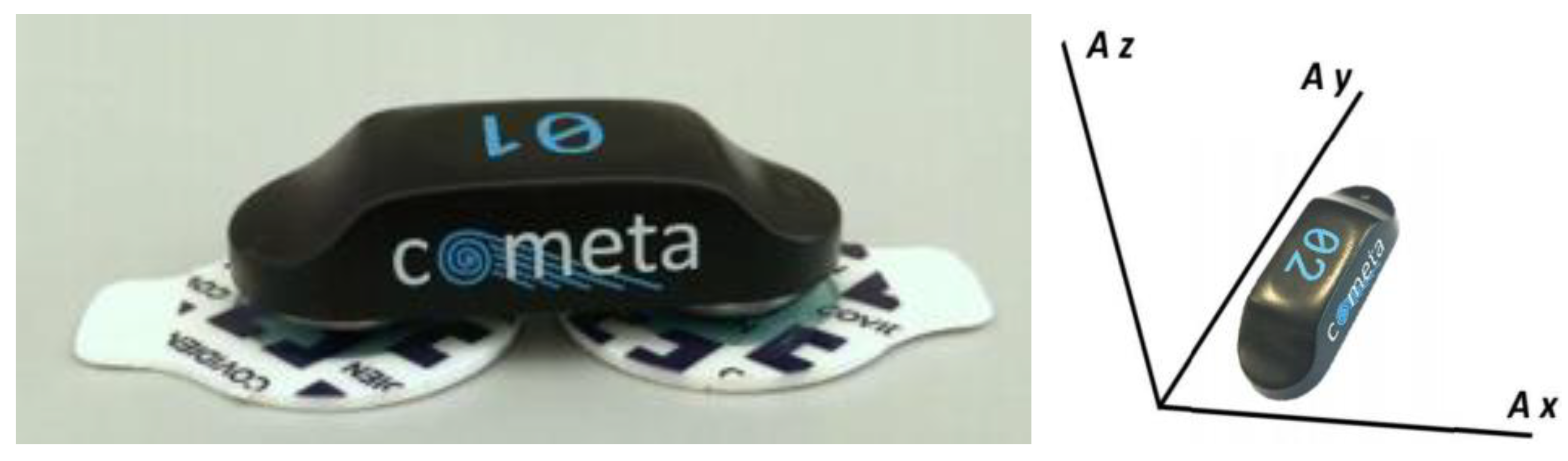

MMG were derived from the acceleration signal data acquired via the Cometa wireless myoelectricity device—a state-of-the-art wireless instrument manufactured by Cometa, Italy. The device was shown in

Figure 1. The instrument is capable of acquiring triaxial acceleration data, with the capability to configure the sampling rate up to 1000 Hz. The apparatus was strategically positioned over the anterior, middle, and posterior deltoid regions, throughout the course of the active movement protocol. To mitigate measurement inaccuracies, myoelectric sensors for detecting MMG signals were affixed to the muscle tissue using adhesive double-sided tape.

In the present study, a 9-axis Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) was utilized to record the angular displacement data of the joint throughout the exercise regimen. The IMU was shown in

Figure 2. The Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), integrating a triaxial accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer, provides robust functionality for tracking comprehensive motion dynamics. Attachment of the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) to the humerus facilitated the acquisition of precise joint angle data. The position of IMU and myoelectricity device was shown in

Figure 3.

2.2. MMG Signal Extraction Method Based on ICEEMDAN Algorithm

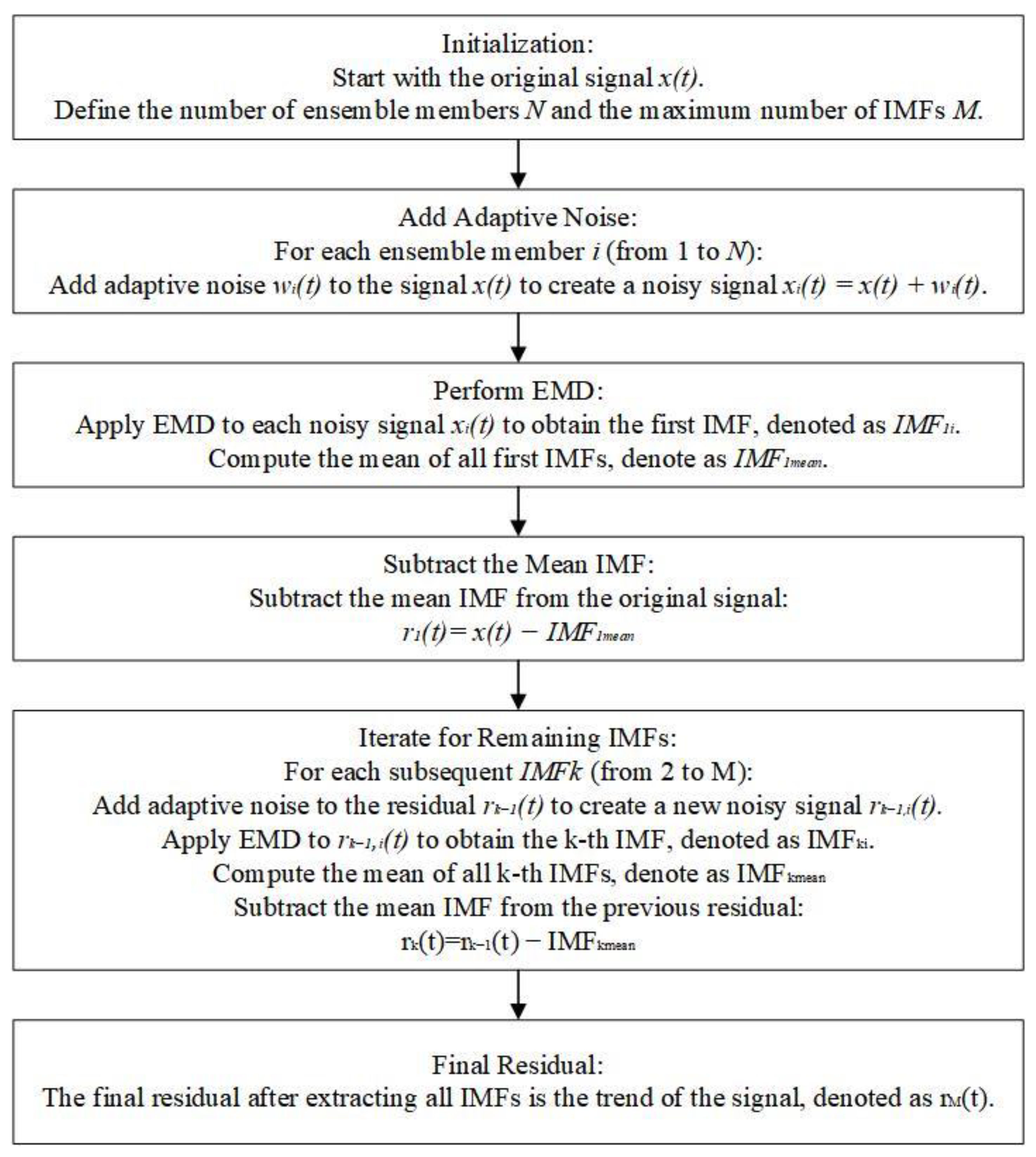

In this research, The ICEEMDAN was utilized to extract MMG signal from acceleration signal collected from deltoid muscles. ICEEMDAN represents a sophisticated advancement in signal processing methodologies, specifically developed to rectify certain inherent limitations observed within the conventional Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) algorithm and its ensemble variant, the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD).The overarching objective of the ICEEMDAN algorithm is to facilitate a decomposition process that is both more resilient and precise for non-stationary and nonlinear signals, concurrently minimizing mode mixing and enhancing computational performance. The flow chat of ICEEMDAN was shown in

Figure 4.

2.3. Human Joint Rotation Angle Estimation Model Based on SMA-BLS

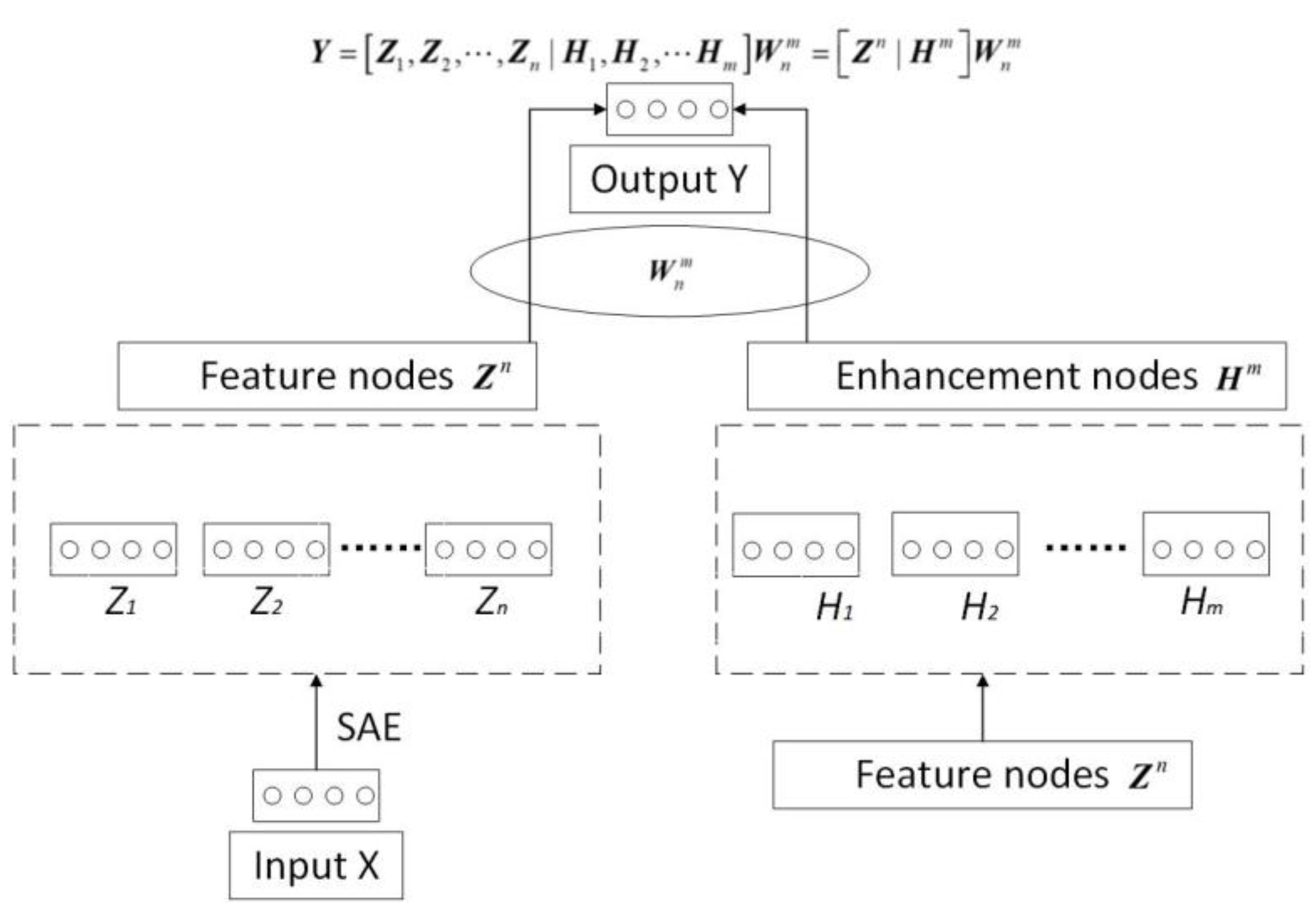

In this research, the Broad learning system (BLS) was utilized for human joint angle prediction, and the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) was utilized for optimization of hyperparameters in BLS. The structure of BLS was shown in

Figure 5, and the structure of human joint angle prediction method was shown in

Figure 6. The following was an introduction to BLS and SMA.

2.3.1. Broad Learning System

The Broad Learning System (BLS) represents an innovative machine learning architecture, introduced as a substitute for conventional deep learning methodologies. Its primary objectives are to streamline the complexity of the model structure and to expedite the training phase. The hypothesis was introduced by a team of investigators from Guangdong University of Technology in the year 2017.The BLS has been architected to deliver elevated performance across diverse computational tasks such as classification, regression, and clustering. Notably, it accomplishes this with a substantial reduction in computational resource demands, in contrast to the more intensive requirements of deep neural networks.

Steps of the Broad Learning System:

Commence with the foundational raw input dataset, which may manifest in diverse formats including visual imagery, temporal sequences, or structured tabular records.

Feature Extraction: As an elective step, initial feature preprocessing can be conducted to enhance the intrinsic characteristics of the dataset prior to subsequent analyses. The inclusion of this step is not mandatory, since the BLS is capable of processing raw data without prior manipulation.

- (2)

Initialize Feature Nodes (FNs):

Generate random projections by constructing a collection of random projection matrices. High-dimensional feature space via these matrices. The quantity of feature nodes (N) and the magnitude of dimensions for random projections (D) represent critical hyperparameters that necessitate careful specification and adjustment.

Utilize random projection matrices to transform the input data, resultant in the generation of feature node representations. This can be expressed as follows:

where

X is the input data,

W is the random projection matrix, and

Z is the transformed feature nodes.

- (3)

Enhancement Nodes (ENs) Generation:

Develop Enhancement Nodes: Formation of enhancement nodes is achieved through the application of rudimentary transformations to the existing feature nodes. Transformations may encompass linear combinations, nonlinear functions, or a variety of additional computational operations. The optimization of enhancement nodes facilitates the augmentation of the discriminative capacity within the feature representation framework.

Integrate functional nodes (FNs) and enhancement nodes (ENs): The concatenation of FNs and ENs constitutes the composite feature representation, facilitating the refinement of the ultimate feature set. This can be expressed as follows:

where

E is the enhancement nodes.

- (4)

Ridge Regression for Output Mapping:

Set Up Ridge Regression: Use ridge regression to map the combined feature representation H to the output. Ridge regression adds a regularization term to the loss function to prevent overfitting.

Solve for Weights: The weights β for the ridge regression can be solved using the following formula:

where Y is the target output, λ is the regularization parameter, and I is the identity matrix.

- (5)

Model Training and Prediction

Training: During training, the model learns the weights β using the training data.

Prediction: For new input data, apply the same transformations to generate the feature nodes and enhancement nodes, and then use the learned weights β to make predictions:

- (6)

Incremental Learning:

Incorporation of Novel Data and Features: The model architecture allows for the integration of new data or additional features by simply adding fresh feature nodes, thereby negating the need for complete retraining of the existing model. Revise the feature nodes and subsequently recalibrate the weight parameters to accommodate the updated values.

Incorporate Additional Enhancement Nodes: Analogously, the procedure allows for the integration of supplementary enhancement nodes to refine and elevate the model's performance attributes. Revise the enhancement nodes and recalibrate the system to determine the updated weights.

2.3.2. Slime Mould Algorithm

The Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) constitutes a metaheuristic optimization technique inspired by natural processes, specifically emulating the foraging and adaptive behavior exhibited by the slime mould Physarum polycephalum. The algorithm was initially proposed by Li et al. The algorithm, developed in 2020, has garnered significant interest due to its demonstrated efficiency and efficacy in addressing a diverse array of optimization challenges.

Steps of the Broad Learning System:

- (1)

Initialization:

A cohort of prospective solutions, metaphorically analogous to slime moulds, is produced through random generation.

Each solution is denoted by a position vector, represented as Xi, with i serving as the index indicative of the particular solution's identity.

- (2)

Fitness Evaluation:

The efficacy of each solution is assessed by means of an objective function, which quantifies its performance. The optimal solution, characterized by the highest or lowest fitness metric as dictated by the specific problem context, is determined.

- (3)

Position Update:

The spatial coordinates of the solution set are iteratively refined by emulating the foraging behavior exhibited by Physarum polycephalum, commonly known as slime mould. the updated iterative equation is as follows:

where:

is the position of the

i-th solution at iteration

t.

is the position of the best solution at iteration

t.

and

are random numbers, with

uniformly distributed in [0, 1] and

in [-1, 1].

- (4)

Boundary Handling:

Should the new positional coordinates of a solution entity surpass the defined limits of the search space, they are they realigned to ensure they remain contained within the established boundaries.

- (5)

Fitness Re-evaluation:

The fitness of each revised solution is reassessed, and the optimal solution is accordingly updated should a more superior alternative be identified.

- (6)

Iteration:

The iterative procedure continues until a predefined termination condition is fulfilled, including the attainment of a maximum iteration count or the achievement of an acceptable level of solution quality.

3. Results

3.1. The Results of MMG Signal Extraction

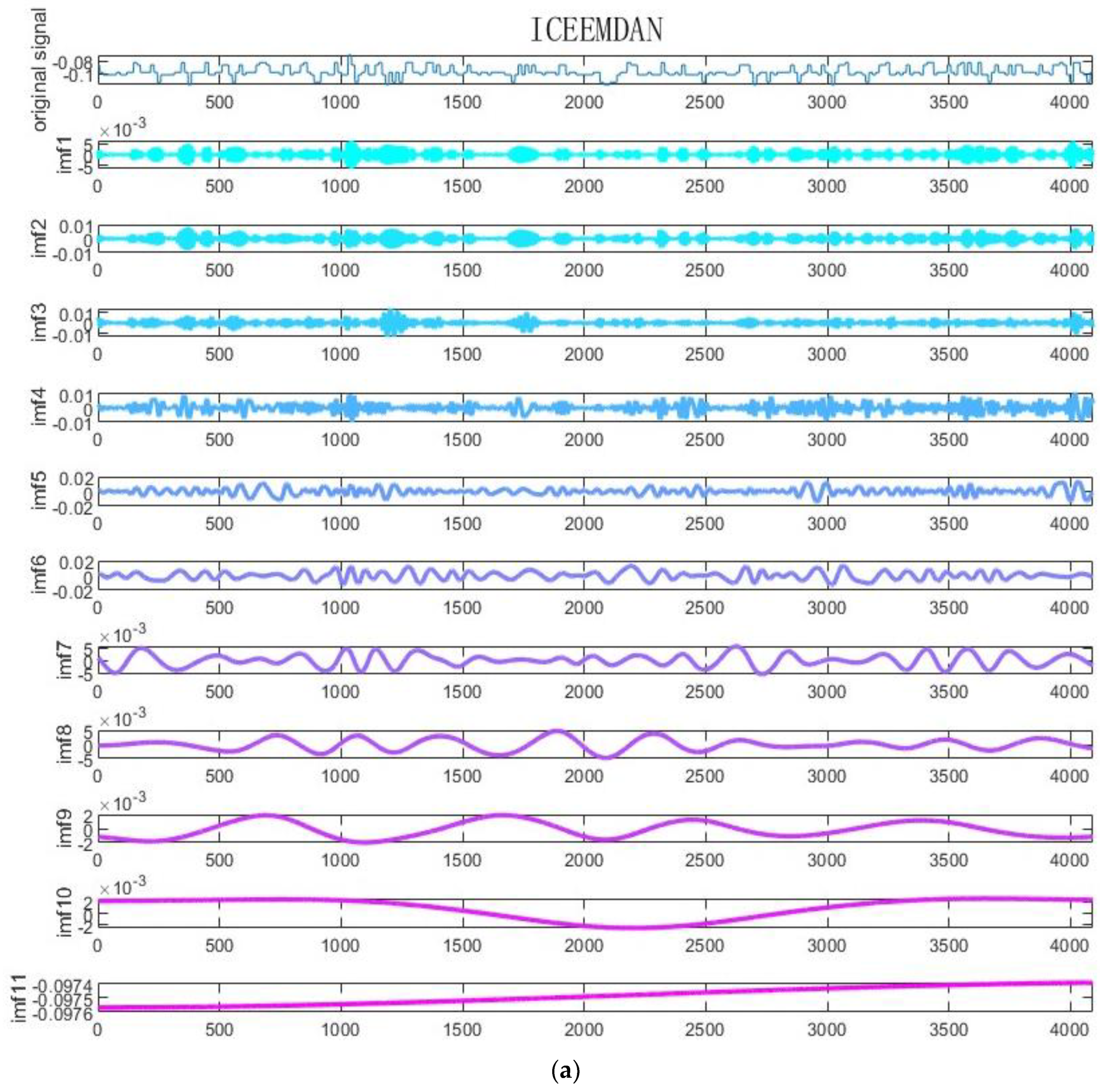

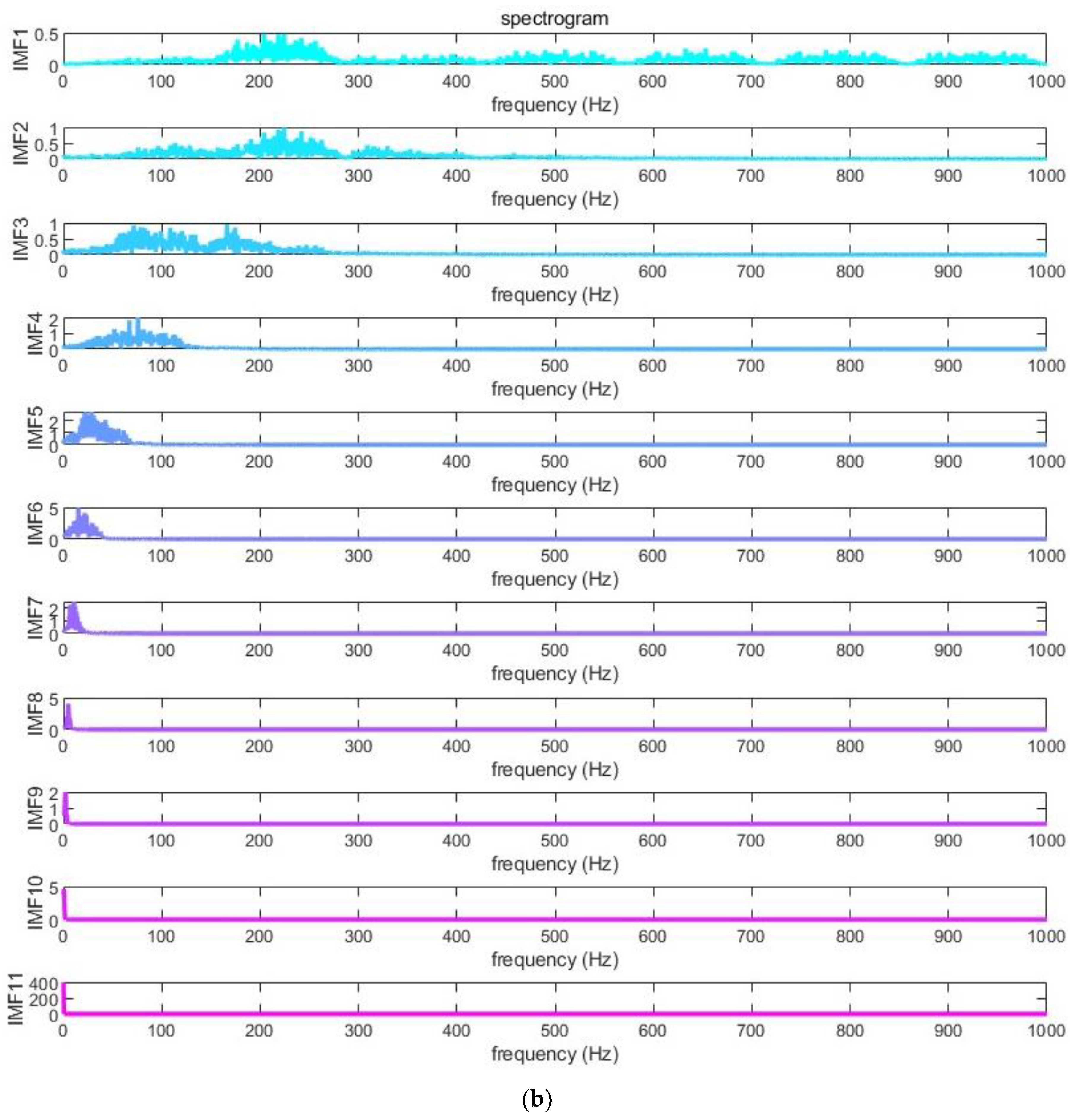

The decomposition outcomes of the biceps' original signal utilizing the ICEEMDAN algorithm are presented in

Figure 7a,b. The imf5-8, characterized by a central frequency range of 10-100 Hz, was identified as the MMG signal. Other Investigational Magnetic Fields (IMFs) pertained to high-frequency noise, as well as comprising elements of gravitational acceleration and the acceleration associated with limb movements. Upon aggregating the decomposition outcomes, it was observed that the artifact in the ACC signal, post-processing with the ICEEMDAN algorithm, corresponded to the IMF characterized by a lower central frequency. Concurrently, the MMG signal was identified as the IMF component exhibiting an intermediate central frequency, consistently present across all four muscle types.

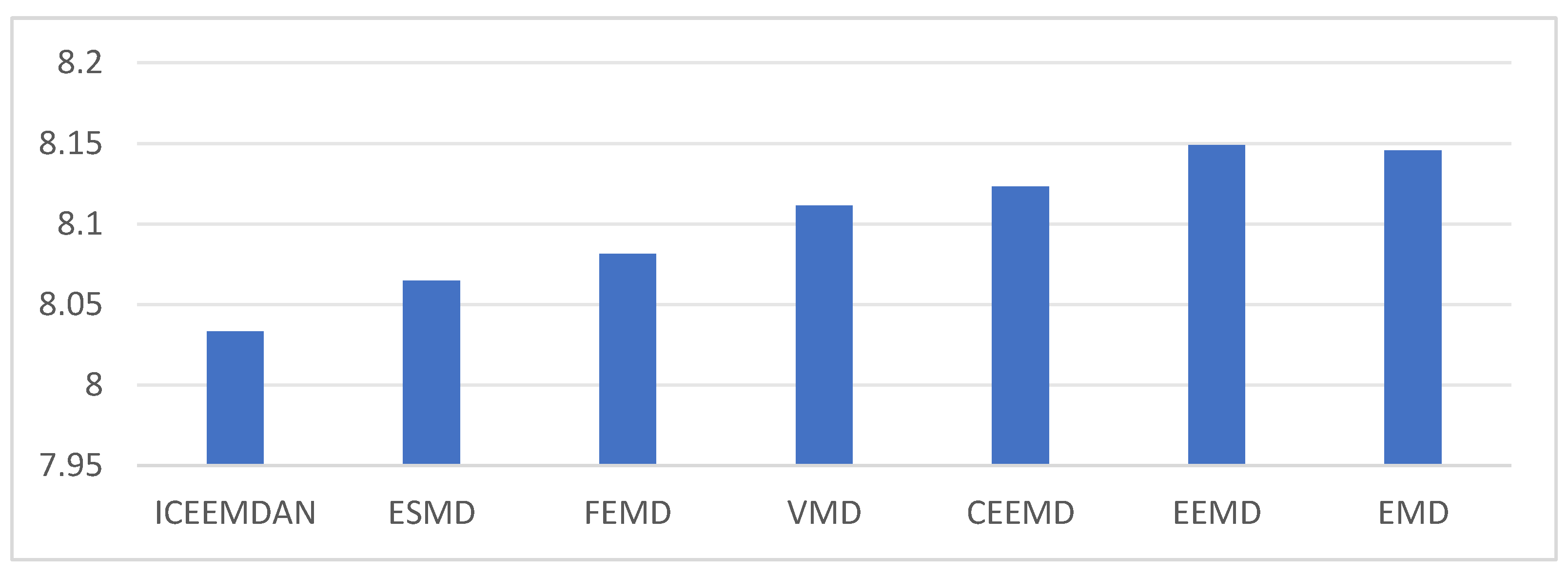

Furthermore, the efficacy of the proposed method was benchmarked against six additional algorithms: Ensemble Synchro-squeezing Mode Decomposition (ESMD), Fast Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (FEMD), Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (CEEMD), Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD), and Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD).The ICEEMDAN algorithm demonstrated the lowest envelope entropy, indicating that the Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) derived from this method harbored the least amount of random noise. Consequently, these IMFs preserved the maximal integrity of the MMG signal, as well as the gravity acceleration and limb movement acceleration data. Envelope entropy of different extraction methods was shown in

Figure 8.

3.2. The Results of MMG Signal Preprocessing

The MMG signal underwent a series of preprocessing steps, as delineated below:

- (1)

DC offset elimination;

- (2)

Full-wave rectification;

- (3)

Linear envelope extraction

- (4)

Normalization.

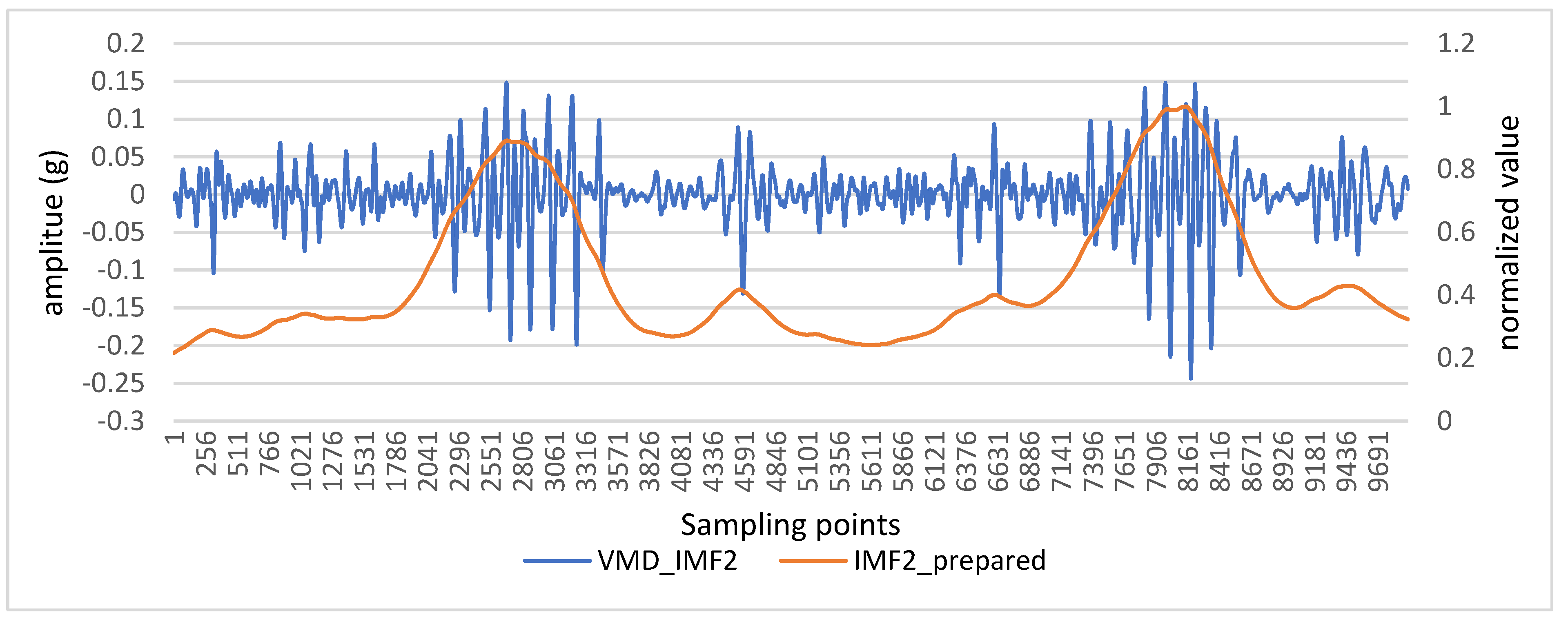

Figure 9 illustrates the MMG signals, comparing their characteristics pre- and post-application of a multi-stage preprocessing algorithm. The graphical representation clearly demonstrated that the nonstationary MMG signal, which is typified by significant variability, was converted into a more regular and stationary form following the preprocessing procedure.

3.3. Joint Angle Prediciotn Results

3.3.1. Forecasting Test Result of Single Person and Multi-Person

In this inquiry, the information from three distinct workout routines was merged sequentially as lateral raises, front raises, and curls.

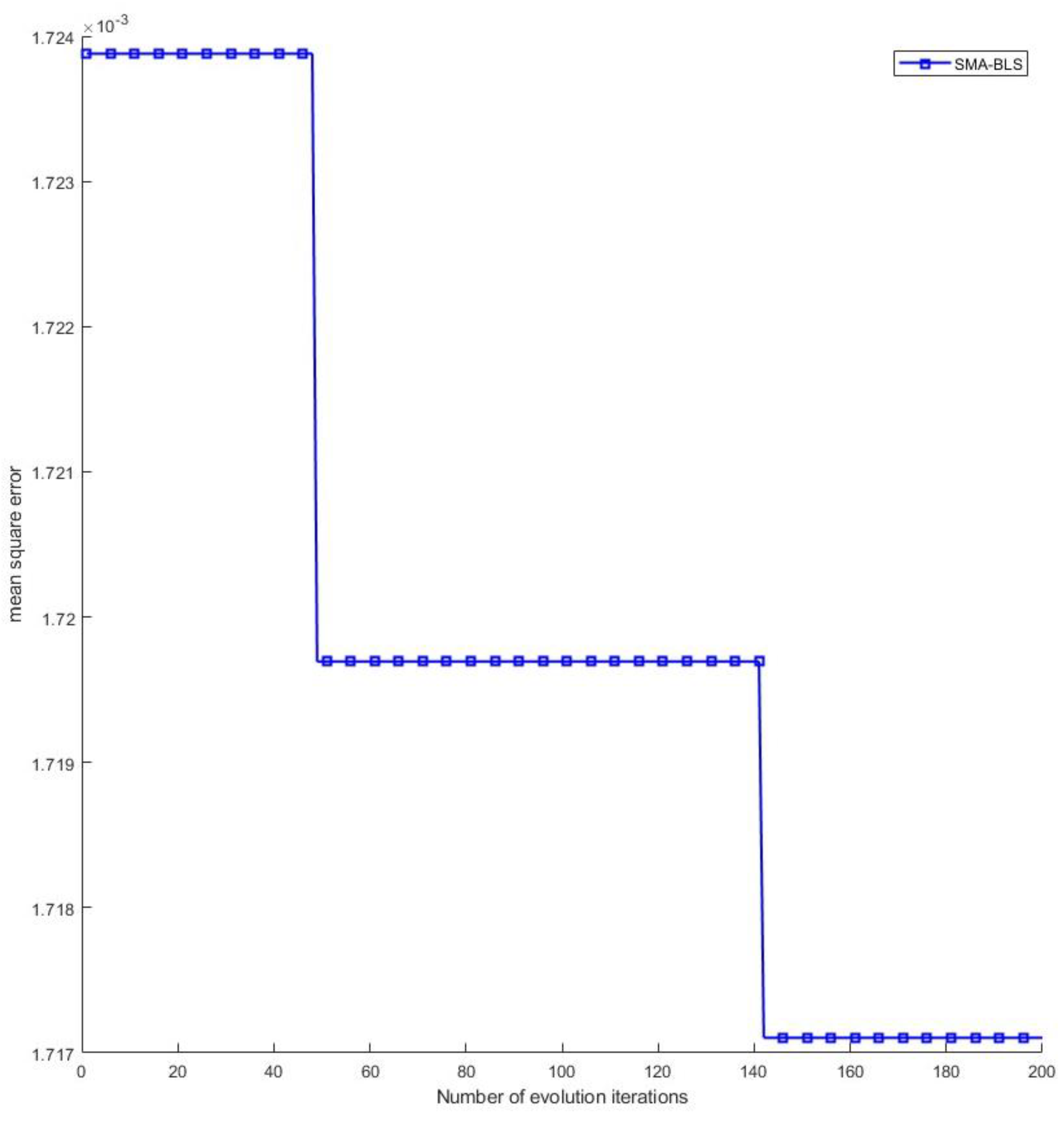

Figure 10 displays the progressive outcomes of SMA-BLS, utilizing MSE as the criterion for evaluating performance.

Table 1 reveals the refined parameters.

Table 2 showcases the SMA-BLS performance on individual datasets, and

Table 3 exhibits the outcomes on datasets involving multiple individuals. Both tables confirm SMA-BLS's exceptional predictive precision in both contexts. Notably, for solo datasets, subject S02 achieved peak accuracy with the following indices: MSE = 0.0015, RMSE = 0.0329, MAE = 0.0094, and R

2 = 0.977. For collective datasets, the peak metrics were: MSE = 0.0017, RMSE = 0.0362, MAE = 0.0095, and R

2 = 0.971.

Table 3 further highlights the Slime Mould algorithm's proficiency in fine-tuning BLS hyperparameters, markedly elevating prediction reliability.

3.3.2. Forecasting Test Result of Different MMG Extraction Methods

Table 4 delineated the comparative predictive outcomes of various myoelectric signal extraction techniques utilizing multi-subject datasets. The findings revealed that the ICEEMDAN algorithm yielded the maximal prediction accuracy when compared to other methods evaluated. The analysis indicates that the MMG signals isolated utilizing the ICEEMDAN algorithm exhibit the highest degree of correlation with human joint angles. Furthermore, the ICEEMDAN algorithm demonstrates superior noise suppression capabilities compared to other methodologies.

3.3.3. Forecasting Test Result of Different Forecast Methods

The comparative analysis conducted on Sheet 6 revealed that the SMA-BLS algorithm exhibits superior efficiency and boasts enhanced prediction accuracy when contrasted with other algorithms evaluated. Sheet 6 illustrates the comparative outcomes of various forecasting methodologies utilizing multi-person datasets, with the SMA-BLS algorithm exhibiting superior performance in terms of estimation accuracy and computational efficiency.

Table 5.

Forecasting test result of different forecast methods.

Table 5.

Forecasting test result of different forecast methods.

| Method |

MSE |

RMSE |

MAE |

R2 |

Training Time(s) |

Forecast Time(ms) |

| SMA-BLS |

0.0017 |

0.0362 |

0.0095 |

0.971 |

195±15.48 |

14.15±0.95 |

| BLS |

0.0041 |

0.0661 |

0.0601 |

0.936 |

15±1.25 |

14.56±0.99 |

| CNN |

0.0046 |

0.0727 |

0.0657 |

0.938 |

268±16.58 |

30.15±2.81 |

| SVM |

0.0032 |

0.0536 |

0.0531 |

0.943 |

308±19.52 |

29.84±2.12 |

| BP |

0.0047 |

0.0679 |

0.0657 |

0.939 |

136.28±16.74 |

29.2±2.9 |

| ELM |

0.0041 |

0.0606 |

0.0803 |

0.938 |

291±20.54 |

31.48±3.21 |

| RF |

0.0045 |

0.0667 |

0.0801 |

0.935 |

251±20.81 |

36.58±3.51 |

| RBF |

0.0045 |

0.0673 |

0.0641 |

0.931 |

261±11.69 |

19.85±1.84 |

| LSTM |

0.0042 |

0.0682 |

0.0784 |

0.920 |

61.28±4.95 |

24.19±2.6 |

3.3.4. Forecasting Test Result of Different Processing Parameters

Table 6 presents the forecasting test results for different envelope orders. The best envelope order for MMG is 2.

4. Discussion

In the present study, an isolation technique for MMG was developed utilizing the ICEEMDAN algorithm. ICEEMDAN had the following features:

- (1)

Adaptive Noise Addition:

Unlike EEMD, which adds fixed white noise, ICEEMDAN uses adaptive noise. The auditory signal is systematically modified across each phase of the decomposition process, with the level of introduced noise carefully calibrated to correspond with the prevailing characteristics of the signal at each respective stage. The implementation of this adaptive methodology facilitates the enhancement of mode separation quality, concurrently mitigating the deleterious effects of noise interference.

- (2)

Complete Ensemble Approach:

The ICEEMDAN method systematically employs a comprehensive ensemble strategy to mitigate the impact of introduced noise on the ultimate analytical outcomes. The computation of the ensemble mean for the Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) serves to nullify the cumulative effect of introduced noise. The implementation of this approach enhances the reliability and consistency of the decomposition process.

- (3)

Mode Mixing Reduction:

Utilizing a meticulous approach to adjust the noise level in conjunction with employing a comprehensive ensemble, the ICEEMDAN algorithm effectively mitigates mode mixing. The resultant physically meaningful intermolecular forces (IMFs) are characterized by distinct oscillatory modes, with each IMF corresponding to an individual mode of oscillation.

- (4)

Computational Efficiency:

ICEEMDAN has been architected to enhance computational efficiency relative to the EEMD method. The application of adaptive noise techniques and the complete ensemble method significantly diminishes the iterative requirement for achieving convergence, thereby rendering the approach appropriate for real-time utilization and the processing of extensive datasets.

information was utilized to evaluate the efficacy of the algorithms. The envelop entropy results indicated that the ICEEMDAN method was the most effective in removing random noise, thus preserving the majority of the MMG signal components.

Following the isolation and preprocessing of MMG, the novel method for estimating joint rotating angles, which is based on the Self-Modulating Algorithm with SMA-BLS, was employed during the performance of arm lateral raises, arm forward raises, and elbow curls. The BLS exhibited the following characteristics:

- (1)

Incremental Learning:

The BLS incorporates an incremental learning capability, enabling the network to integrate new features or nodes without the necessity of retraining the entire system architecture. The adaptability of this system facilitates a high degree of flexibility and efficiency, rendering it particularly suitable for real-time learning and dynamic adjustments.

- (2)

Flat Network Structure:

The architecture of the BLS network deviates from the multi-layered neuron configuration characteristic of deep learning models, employing instead a single, un-tiered structure. The architecture comprises a Feature Node (FN) layer, an Enhancement Node (EN) layer, and a Ridge Regression layer. The fully connected (FN) layer is responsible for the extraction of intrinsic features from the unprocessed input data. Subsequently, the enhancement layer (EN) amplifies the discriminatory attributes of these extracted features to facilitate improved recognition. Finally, the ridge regression layer performs a mapping function, translating the augmented features into the corresponding output.

- (3)

Fast Training Speed:

The flat architecture of the BLS, coupled with its capacity for incremental node addition, facilitates significantly faster training compared to deep neural networks. This characteristic renders it particularly apt for applications requiring expedited model updates.

- (4)

High Accuracy:

The BLS model, noted for its structural simplicity, exhibits accuracy that is either commensurate with or surpasses that of deep learning algorithms across a spectrum of tasks. This is particularly evident in scenarios where the available dataset is not of an excessively large magnitude.

- (5)

BLS exhibits a low computational overhead due to the reduced number of parameters that necessitate optimization, thereby diminishing overall computational expenses and energy usage. This attribute is particularly advantageous in both cloud-centric and edge computing infrastructures.

The characteristics of slime mould algorithm (SMA) were delineated as follows:

SMA exhibit a remarkable capacity to identify the most direct route between food sources, dynamically modifying their network architecture to enhance resource acquisition efficiency.

- (2)

Adaptability:

Organisms have the capability to modulate their neural networks in a dynamic manner in response to fluctuations in environmental conditions, including variations in food availability and the presence of physical barriers.

- (3)

Self-Organization:

The network architecture instantiated by SMA exhibits self-organizational properties, enabling the formation of intricate structural configurations in the absence of centralized regulatory mechanisms.

The enhancement of the SMA algorithm has markedly elevated the estimation precision of the BLS methodology. The integration of BLS training velocity advantages into the SMA-BLS model has resulted in a superior joint angle recognition algorithm characterized by high precision and minimal computational expenditure.

5. Conclusions

In the present investigation, we introduced an innovative methodology for the estimation of rotational angles of the shoulder joints, leveraging Mechanomyography (MMG) signals in conjunction with a Broad Learning System that has been enhanced by the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA-BLS). The primary contributions of the present study encompass the following aspects:

- (1)

Signal Extraction and Processing:

ICEEMDAN was proposed to extract MMG signals from raw acceleration data. The employed technique successfully delineated the MMG signal, maintaining an equilibrium between the suppression of artifactual noise and the preservation of signal integrity with minimal distortion.

- (2)

Model Development:

The Slime Mould Algorithm-Optimized Broad Learning System (SMA-BLS) was employed for the estimation of joint rotational angles. The BLS is recognized for its capability to incrementally incorporate additional samples into its dataset without the necessity for retraining, thereby substantially diminishing computational expenses. Following optimization via the SMA, the estimation accuracy has been markedly enhanced.

- (3)

Application Potential:

The novel paradigm facilitates the manipulation of wearable exoskeleton robots, enabling the provision of instantaneous feedback regarding articulatory kinematics. The findings carry profound implications for their application across various fields, including rehabilitation, sports science, and human-computer interaction. The utilization of both the extracted MMG and gesture artifacts enables the estimation of joint angles, thereby providing adaptability across diverse operational contexts.

- (4)

Validation and Performance:

The model's efficacy was confirmed via a series of experimental validations encompassing three distinct activity types, yielding results that consistently demonstrated precise estimations of joint rotational angles.

The evaluation of the predictive accuracy for both individual and aggregated subject datasets revealed marked precision, characterized by minimal Mean Squared Error (MSE), reduced Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and diminished Mean Absolute Error (MAE), alongside elevated R2 coefficients. These metrics collectively affirm the model's resilience and its capacity for broad applicability.

Future Work:

Subsequent investigations may be directed toward expanding the utilization of the suggested model to additional articulations and encompassing more intricate motion patterns. The incorporation of sophisticated sensor arrays and real-time data processing algorithms into the model has the potential to significantly augment its applied functionality. Investigative enhancement of the SMA, alongside the examination of additional bio-inspired computational methods, has the potential to yield improved performance metrics and an expanded scope of application.

Funding

Please add: This work was supported by Postgraduate Research Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant number KYCX23-0512).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work involved human subjects in its research. Approval of all ethical and experimental procedures and protocols was granted by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University under approval number 2021-SR109.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the experiment participants and Postgraduate Research Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province for their support of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vélez-Guerrero M A, Callejas-Cuervo M, Mazzoleni S. Artificial intelligence-based wearable robotic exoskeletons for upper limb rehabilitation: A review[J]. Sensors, 2021, 21(6): 2146. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández A, Lobo-Prat J, Font-Llagunes J M. Systematic review on wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait training in neuromuscular impairments[J]. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation, 2021, 18(1): 22. [CrossRef]

- Crea S, Beckerle P, De Looze M, et al. Occupational exoskeletons: A roadmap toward large-scale adoption. Methodology and challenges of bringing exoskeletons to workplaces[J]. Wearable Technologies, 2021, 2: e11. [CrossRef]

- Jing H, Zheng T, Zhang Q, et al. Human Operation Augmentation through Wearable Robotic Limb Integrated with Mixed Reality Device[J]. Biomimetics, 2023, 8(6): 479. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Hernandez U, Metcalfe B, Assaf T, et al. Wearable assistive robotics: A perspective on current challenges and future trends[J]. Sensors, 2021, 21(20): 6751. [CrossRef]

- Thalman C, Artemiadis P. A review of soft wearable robots that provide active assistance: Trends, common actuation methods, fabrication, and applications[J]. Wearable Technologies, 2020, 1: e3. [CrossRef]

- Gu F, Chung M H, Chignell M, et al. A survey on deep learning for human activity recognition[J]. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 2021, 54(8): 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Kaseris M, Kostavelis I, Malassiotis S. A Comprehensive Survey on Deep Learning Methods in Human Activity Recognition[J]. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 2024, 6(2): 842-876. [CrossRef]

- Meng Z, Zhang M, Guo C, et al. Recent progress in sensing and computing techniques for human activity recognition and motion analysis[J]. Electronics, 2020, 9(9): 1357. [CrossRef]

- Minoru Shinohara; Motoki Kouzaki; Takeshi Yoshihisa; Tetsuo Fukunaga; "Mechanomyography of The Human Quadriceps Muscle During Incremental Cycle Ergometry", EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF APPLIED PHYSIOLOGY AND OCCUPATIONAL, 1997.

- Ugur Sahin; Ferat Sahin; "Pattern Recognition with Surface EMG Signal Based Wavelet Transformation", 2012 IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SYSTEMS, MAN, 2012.

- Alexandre Balbinot; Gabriela Favieiro; "A Neuro-fuzzy System for Characterization of Arm Movements", SENSORS (BASEL, SWITZERLAND), 2013.

- Ondrej Kainz; Frantisek Jakab; "Approach to Hand Tracking and Gesture Recognition Based on Depth-Sensing Cameras and EMG Monitoring", ACTA INFORMATICA PRAGENSIA, 2014.

- Andrea, E. Frank; Alyssa Kubota; Laurel D. Riek; "Wearable Activity Recognition for Robust Human-robot Teaming in Safety-critical Environments Via Hybrid Neural Networks", 2019 IEEE/RSJ INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INTELLIGENT, 2019.

- Ali Moin; Andy Zhou; Abbas Rahimi; Alisha Menon; Simone Benatti; George Alexandrov; Senam Tamakloe; Jonathan Ting; Natasha Yamamoto; Yasser Khan; Fred Burghardt; Luca Benini; Ana C. Arias; Jan M. Rabaey; "A Wearable Biosensing System with In-sensor Adaptive Machine Learning for Hand Gesture Recognition", NATURE ELECTRONICS, 2020.

- Andrés Jaramillo-Yánez; Marco E Benalcázar; Elisa Mena-Maldonado; "Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition Using Surface Electromyography and Machine Learning: A Systematic Literature Review", SENSORS (BASEL, SWITZERLAND), 2020.

- X. Sheng; Xuecong Ding; Weichao Guo; Lei Hua; Mian Wang; Xiangyang Zhu; "Toward An Integrated Multi-Modal SEMG/MMG/NIRS Sensing System for Human–Machine Interface Robust to Muscular Fatigue", IEEE SENSORS JOURNAL, 2021.

- Dorra Trabelsi; Samer Mohammed; Yacine Amirat; Latifa Oukhellou; "Activity Recognition Using Body Mounted Sensors: An Unsupervised Learning Based Approach", THE 2012 INTERNATIONAL JOINT CONFERENCE ON NEURAL NETWORKS, 2012.

- Faicel Chamroukhi; Samer Mohammed; Dorra Trabelsi; Latifa Oukhellou; Yacine Amirat; "Joint Segmentation Of Multivariate Time Series With Hidden Process Regression For Human Activity Recognition", ARXIV-STAT.ML, 2013.

- Dorra Trabelsi; Samer Mohammed; Faicel Chamroukhi; Latifa Oukhellou; Yacine Amirat; "An Unsupervised Approach For Automatic Activity Recognition Based On Hidden Markov Model Regression", ARXIV-STAT.ML, 2013. (IF: 4).

- Michael S. Ryoo; Thomas J. Fuchs; Lu Xia; Jake K. Aggarwal; Larry H. Matthies; "Robot-Centric Activity Prediction from First-Person Videos: What Will They Do to Me?", 2015 10TH ACM/IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON HUMAN-ROBOT, 2015.

- Skyler Seto; Wenyu Zhang; Yichen Zhou; "Multivariate Time Series Classification Using Dynamic Time Warping Template Selection For Human Activity Recognition", ARXIV-CS.AI, 2015.

- Khaled Safi; Samer Mohammed; Ferhat Attal; Mohamad Khalil; Yacine Amirat; "Recognition of Different Daily Living Activities Using Hidden Markov Model Regression", 2016 3RD MIDDLE EAST CONFERENCE ON BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING, 2016.

- Faisal Sikder; Dilip Sarkar; "Log-Sum Distance Measures and Its Application to Human-Activity Monitoring and Recognition Using Data From Motion Sensors", IEEE SENSORS JOURNAL, 2017.

- Lu Peng; Shan Liu; Rui Liu; Lin Wang; "Effective Long Short-term Memory with Differential Evolution Algorithm for Electricity Price Prediction", ENERGY, 2018.

- Jacek Trelinski; Bogdan Kwolek; "Ensemble of Multi-channel CNNs for Multi-class Time-Series Classification. Depth-Based Human Activity Recognition", 2020.

- Wen Qi; Hang Su; Andrea Aliverti; "A Smartphone-Based Adaptive Recognition and Real-Time Monitoring System for Human Activities", IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON HUMAN-MACHINE SYSTEMS, 2020.

- M. A. Islam, K. Sundaraj, R. B. Ahmad, N. U. Ahamed and M. A. Ali, "Mechanomyography Sensor Development, Related Signal Processing, and Applications: A Systematic Review," in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 2499-2516, July 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi, W. Dong, W. Lin and Y. Gao, "Soft Wearable Robots: Development Status and Technical Challenges," in Sensors, vol. 22, no. 19, Art. no. 7584, Oct 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi, W. Dong, W. Lin, L. He, X. Wang, P. Li and Y. Gao, "Human Joint Torque Estimation Based on Mechanomyography for Upper Extremity Exosuit," in Electronics, vol. 11, no. 9, Art. no. 1335, Apr 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Ibitoye, N. A. Hamzaid, J. M. Zuniga and A. K. A. Wahab, "Mechanomyography and muscle function assessment: A review of current state and prospects," in Clinical Biomechanics, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 691-704, June 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Wang, H. Wu, C. Xie and L. Gao, "Suppression of Motion Artifacts in Multichannel Mechanomyography Using Multivariate Empirical Mode Decomposition," in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 19, no. 14, pp. 5732-5739, 15 July15, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Gao, W. Lu, D. Wang, H. Cao and G. Zhang, "A Novel Noise Suppression and Artifact Removal Method of Mechanomyography Based on RLS, IGWO-VMD, and CEEMDAN," in Journal of Sensors, vol. 2022, Art. no. 4239211. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Christiano and T. J. Fitzgerald, "The band pass filter," in international economic review, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 435-465, June 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Hussin, G. Birasamy and Z. Hamid, "Design of butterworth band-pass filter," in Politeknik & Kolej Komuniti Journal of Engineering and Technology, vol. 1, no. 1, Dec 2016.

- J. Casson, D. C. Yates, S. Patel and E. Rodriguez-Villegas, "An analogue bandpass filter realisation of the Continuous Wavelet Transform," 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, France, 2007, pp. 1850-1854. [CrossRef]

- N. Rehman and D. P. Mandic. "Multivariate empirical mode decomposition." in Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 466, no. 2117, pp. 1291-1302, Dec 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lei, J. Lin, Z. He and M. J. Zuo, "A review on empirical mode decomposition in fault diagnosis of rotating machinery," in Mechanical systems and signal processing, vol. 35, no. 1-2, pp. 108-126, Feb 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Barbosh, P. Singh and A. Sadhu, "Empirical mode decomposition and its variants: A review with applications in structural health monitoring." in Smart Materials and Structures, vol. 29, no. 9, Aug 2020, Art. no. 093001. [CrossRef]

- Ran C, Xiao P, Luo Z, et al. Identification of pipeline intrusion signals based on ICEEMDAN-FE-AIT and F-ELM in the uwDAS system[J]. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2024.

- Kou Z, Yang F, Wu J, et al. Application of ICEEMDAN energy entropy and AFSA-SVM for fault diagnosis of hoist sheave bearing[J]. Entropy, 2020, 22(12): 1347. [CrossRef]

- Emeksiz C, Tan M. Wind speed estimation using novelty hybrid adaptive estimation model based on decomposition and deep learning methods (ICEEMDAN-CNN)[J]. Energy, 2022, 249: 123785. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Bu J, Yang Z, et al. A denoising method for loaded coal-rock charge signals based on a joint algorithm of IWT and ICEEMDAN[J]. IEEE Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gong X, Zhang T, Chen C L P, et al. Research review for broad learning system: Algorithms, theory, and applications[J]. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 2021, 52(9): 8922-8950. [CrossRef]

- Chen C L P, Liu Z. Broad learning system: An effective and efficient incremental learning system without the need for deep architecture[J]. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 2017, 29(1): 10-24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Li J, Lu G, et al. Analysis and variants of broad learning system[J]. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, 2020, 52(1): 334-344. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Chen H, Wang M, et al. Slime mould algorithm: A new method for stochastic optimization[J]. Future generation computer systems, 2020, 111: 300-323. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Li C, Mafarja M, et al. Slime mould algorithm: a comprehensive review of recent variants and applications[J]. International Journal of Systems Science, 2023, 54(1): 204-235. [CrossRef]

- Gharehchopogh F S, Ucan A, Ibrikci T, et al. Slime mould algorithm: A comprehensive survey of its variants and applications[J]. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 2023, 30(4): 2683-2723. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).