1. Introduction

In around 20–30% of patients with Bell’s palsy or in any case of more severe facial nerve lesion, facial palsy does not heal completely. Instead, an aberrant reinnervation process develops, which is usually characterized by the occurrence of synkinesis [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This is an unintentional hyperactivation and co-movement of the facial muscles that occurs simultaneously with intentional facial movements [

2]. For example, movements of the corner of the mouth can lead to ipsilateral eye closure in the sense of oro-ocular synkinesis. Ultimately, any facial muscle in any combination with other facial muscles can be affected [

4].

The development of synkinesis requires an axonal damage. During regeneration, not all of the regrowing axons reach their original muscle to be innervated, but many sprout undirected into other peripheral branches of the facial nerve. Synkinesis occurs when an axon or several axons with the same function send sprouts to muscle fibers from two or more different muscles with physiological different functions, i.e., to the original target muscle and to any other muscle. This excessive muscle innervation can also lead to an increased activity and hypertonic state [

2,

5]. The physical disabilities are often accompanied by psychological impairments due to stigmatization and non-verbal communication [

2,

6,

7].

In addition to drug treatment with botulinum toxin, facial training is also considered as a treatment option for synkinesis [

8]. However, there are currently no international standard protocols for facial training or rehabilitation [

2]. One possible training principle is biofeedback, which has been used as a combination of visual and electromyography (EMG) feedback in Jena since 2012 to treat patients with post-paralytic facial synkinesis [

9]. The EMG biofeedback signals provide information about the state of activity of the facial muscles. Under the guidance of a specialized therapist, patients learn to perform symmetrical facial movements according to the interpretation of the biofeedback signals and to voluntarily avoid synkinesis occurring at the same time [

2].

The therapeutic principle of biofeedback has been used clinically for more than 50 years in the rehabilitation of neuromuscular disorders. Reviews have shown a positive therapeutic effect specifically for the use of biofeedback in rehabilitation after strokes, fecal and urinary incontinence, and the treatment of headaches [

10]. For facial nerve palsy, nevertheless, the evidence for the use of biofeedback in reviews is unclear due to the poor comparability of the individual studies. The use of a combination of EMG and visual feedback also makes it difficult to attribute therapy effects to the individual biofeedback modality in the evaluation [

10,

11,

12]. This also explains why, in a recently published Delphi method-based study, the facial therapy experts surveyed attached little importance to the use of biofeedback training in the rehabilitation of facial nerve palsies and didn´t rated it as an essential therapy option [

13].

This is all the more astonishing because the therapy effect of the intensified 10-day facial training was already demonstrated in previous studies as an improvement of the facial nerve palsy-related quality of life subjectively assessed by the patients [

14] and the grading objectively assessed by a trained examiner using the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS) [

9]. Starting from this, in the present study the training effect should be visualized by the change of the amplitudes of the routinely applied surface EMG biofeedback system as an objective outcome measure. It is hypothesized that relaxation of the facial muscles reflected by a reduction of the EMG amplitudes is a positive effect of this training.

The aim is not to record externally visible changes that occur after completing the combined biofeedback training, but also direct electrophysiological changes in the facial muscles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

This prospective observational and longitudinal study included patients with post-paralytic facial synkinesis of different etiologies who participated in the intensified 2-weeks-facial training combining electromyography and visual biofeedback training at the Facial-Nerve-Center of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Jena University Hospital, between April and July 2022. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jena University Jena, Germany (protocol code 2022-2589_1-BO; approved on 05 April 2022). All participants gave written informed consent prior to their inclusion in this study. There was no difference in treatment of the patients whether participating the study or not.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 18 years; a unilateral, chronic, peripheral facial palsy with stable symptoms for more than 6 months [

1] with needle electromyography (EMG) confirmed voluntary activity in the affected facial muscles including aberrant, synkinetic reinnervation, and participation in a two week-lasting biofeedback-based training of facial muscles at Facial-Nerve-Center, Jena University Hospital with existence of written consent.

The exclusion criteria were: acute facial nerve palsy, lack of signs of synkinetic reinnervation of the facial musculature in needle EMG, botulinum toxin treatments within the last 3 months before the start of training, and missing participation, discontinuation or interruption in EMG-biofeedback training for more than 2 training-days at the Facial-Nerve-Center Jena, lack of written consent from the patient or lack of capacity to consent [

6,

14].

2.3. Intensified 2-Weeks Biofeedback Training at Facial-Nerve-Center Jena

Since more than 10 years, the Facial-Nerve-Center offers a 2-weeks biofeedback training course developed specifically for the treatment of post-paralytic facial synkinesis. It is based on elements of biofeedback combined with Taub's Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) [

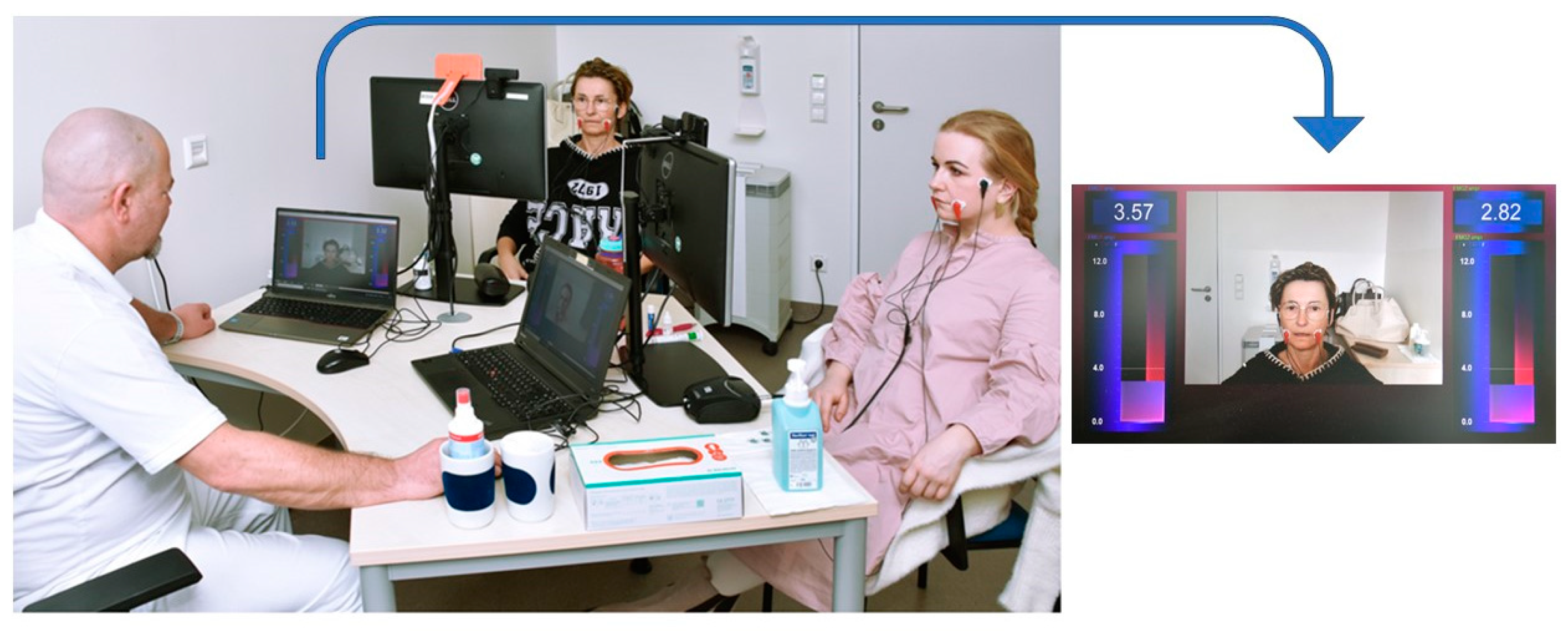

6]. The aim of this facial muscle training is to improve facial symmetry and muscle coordination, reduce motor deficits, and enable relaxation in the face to avoid interacting muscles to limit each other’s movements. By these physical improvements, psychosocial impairments are reduced as well. Usually, two patients were trained simultaneously on two consecutive weeks from Monday to Friday for three hours in the morning under the guidance of one of the two specialized therapists (hereinafter referred to as therapist A and B) at the Facial-Nerve-Center Jena and using a 2-chanal-surface EMG and visual biofeedback. For this purpose, two bipolar 24 x 30 mm foam hydrogel electrodes of the type Kendall H124SG (Cardinal Health, Dublin and Odio) are attached to each side of the face, recording the muscles of the cheek and mouth region. These electrodes were coupled with the NeXus-10 MKII biofeedback system (Mind Media, Roermond-Herten, Netherlands). One of the bipolar electrodes is placed over the arcus zygomaticus halfway between the angulus oculi lateralis and the ventral attachment of the auricle, the second in the area of the modiolus anguli oris on the cheek (

Figure 1. ). If the electrodes need to be repositioned in areas with pronounced scars, wrinkles or a beard, they are placed as close as possible to the original position and then symmetrically on the contralateral side of the face to avoid visual confusion for patients. Using Bio Trace software animations (Mind Media BV, Netherlands), the EMG activity of both halves of the face, which is proportional to the muscle activity, were then visualized numerically and as a vertical bars on a screen in front of the patient. Furthermore, a video-generated mirror image of the patient´s face is generated via webcam and displayed in the middle of the screen. The therapist sitting opposite also sees the EMG feedback bars and mirror images of their patients on their screen (

Figure 1) [

9].

Patients should learn to perform facial movements more symmetrically while consciously avoiding too strong movements of the contralateral side of the face and controlling unintended co-movements of other ipsilateral facial muscles in the sense of synkinesis. The aim is to equalize the activity level of both halves of the face during the exercises and to improve the conscious relaxation phases of the facial muscles between the individual exercises. Similar to Taub's principles, simpler exercises are initially learned in the first week of training with continuous feedback from the therapist, which are then combined into more complex movement sequences in the second week (

Table 1.).

Patients were also instructed to correct movements independently using the biofeedback signals [

15]. Patients were also given homework to repeat previously trained exercises alone without their therapist in the afternoons and at the weekend for about two hours with a hand mirror. Their training units and performance was documented by the patients themselves in a training diary. This should prepare the patients for regular self-motivated training after the instructed two weeks of training. A follow-up examination took place six months after the intensified training to evaluate the long-term effects and the success of the therapy [

9,

14,

15].

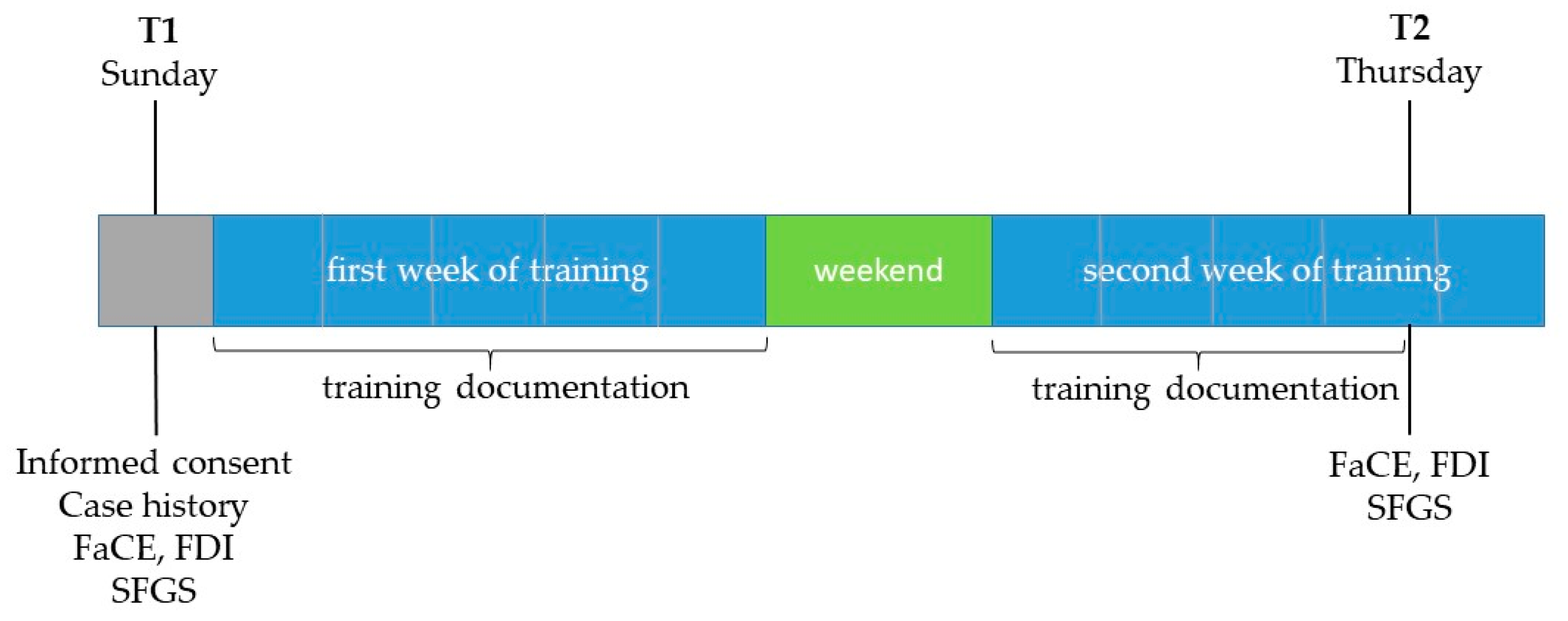

2.4. Measurement Times and Recorded Parameters

All grading assessments were performed at two time points: T1 = one day before the start of the training (mostly on Sunday before the training started on Monday) and T2 = on the afternoon of the day before the training ended (mostly on Thursday afternoon of the second training week) after completion of the second-last training day (

Figure 2). Of the 8 - 10 days on which the patients trained on site with biofeedback support, 7 - 9 training days between T1 and T2 were examined as part of the study.

At the first examination date (T1) all patients were personally informed about the study and patient history data were recorded. Furthermore, the facial palsy-related quality of life was assessed by the patients' self-assessment using the Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale (FaCE) and the Facial Disability Index (FDI) in the German version [

15]. With the help of the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System [

16], an additional assessment of facial nerve palsy was carried out by a non-blinded independent rater using photographs taken in a standardized way as part of the clinical routine. Finally, the patients were instructed to document the amplitudes of the surface EMG at a muscle relaxation task routinely performed daily during the beginning of their training on forms specially designed for this study.

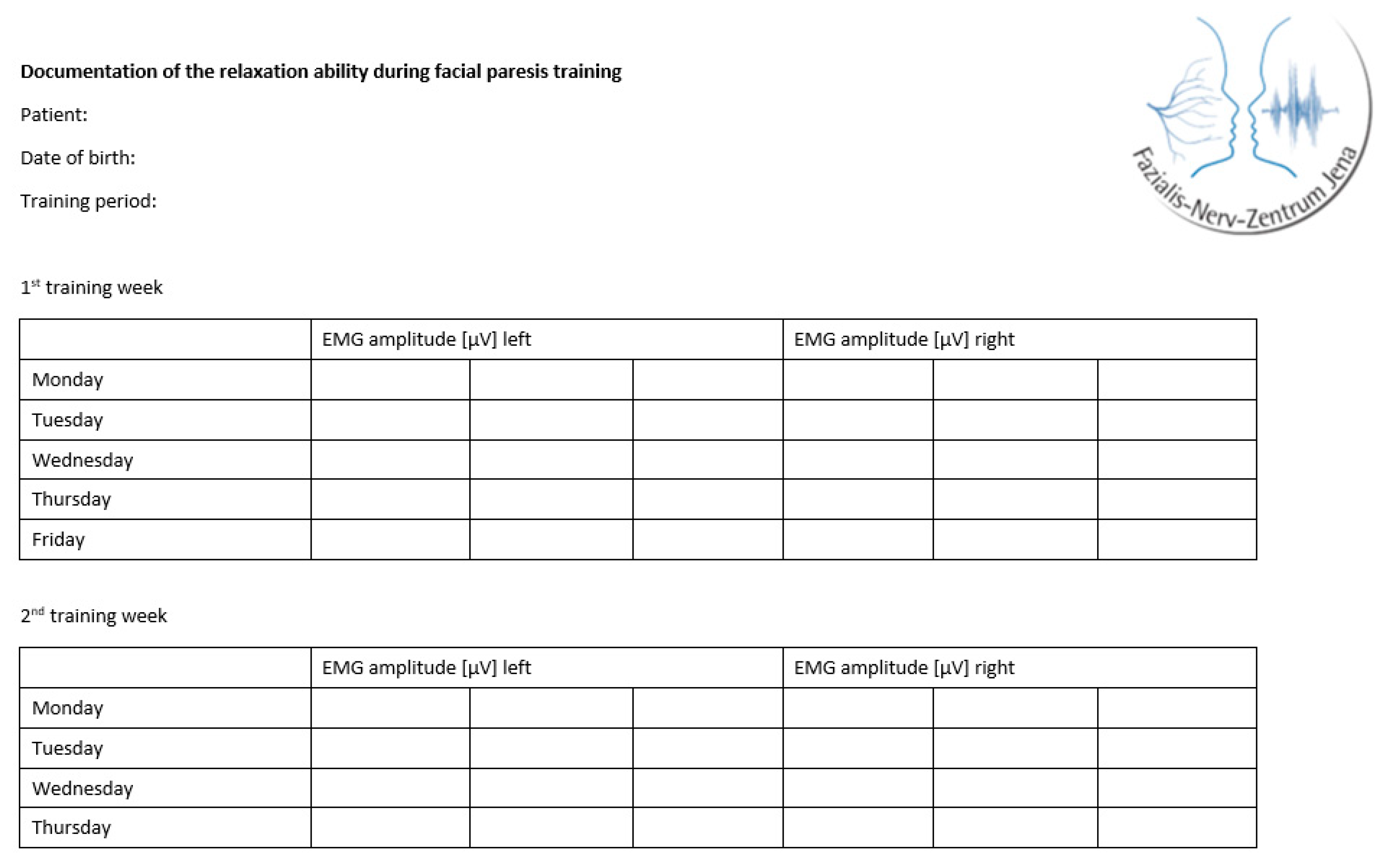

The training was individually adapted for each patient according to the personal therapy goals, motivation, and severity of the synkinesis and facial motion impairments of the paresis. Expecting an influence of the individualization on the training effects, for the study an additional training documentation was carried out. At the beginning of each training day, the patients routinely performed a muscle relaxation task and documented three EMG amplitudes in µV for each side of the face (

Figure 3 ).

To avoid mistakes of the self-documentation, all patients received a written instruction (

Appendix A Figure A1). They were contacted by telephone on the first days of training and reinstructed if necessary. The first author was also in close contact with the therapists, who were also informed about the documentation forms and were therefore able to support the patients in completing them. To avoid fatigue effects the amplitudes were recorded at the beginning of the training. When evaluating the documentation forms of each patient, the three EMG amplitudes recorded for each side of the face were transferred directly to the electronic data collection files of the study.

On the first (T1) and second examination date (T2) the patients completed the FaCE and FDI questionnaires. The completed training documentation forms were collected and standardized photo series, containing 12 photos each, were taken to assess the severity of facial nerve palsy using the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System.

2.5. Facial Clinemetric Evaluation and Facial Disability Index

The disease-specific Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale (FaCE) and the Facial Disability Index (FDI) in the validated German-language version were used to record the facial nerve palsy-related quality of life. In both questionnaires the patient self-assesses the limitations in quality of life resulting from the paresis [

16].

The scores are calculated according to the formulas given on the form of the German-language questionnaire, with the exception of the FaCE Facial Comfort. For this score, the formula had to be corrected as one of the three calculated items, namely item 16, does not appear in the German version and the original questionnaire [

16,

17]. Item 16 was replaced by item 13, which matches the content of this subscore and has not yet been calculated in the other subscores:

where #valid stands for the number of items within the domain for which an adequate response was given.

Low scores indicate a high level of restrictions on quality of life [

17,

18].

2.6. Sunnybrook Facial Grading System

With the help of the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (FSGS), an additional assessment of facial nerve palsy was carried out by the examiner regarding a series of twelve standardized photographs taken routinely and independently of the study before the start of training and after completion of the penultimate training day. The following nine facial expressions are photographed: (1) at rest, (2) frowning, (3) closing both eyes gently, (4) closing both eyes with maximum force, (5) wrinkling the nose, (6) raising both corners of the mouth with the mouth closed, (7) showing teeth, (8) pursing the lips, (9) blowing cheeks, (10) snarling, (11) pulling down both corners of the mouth, and (12) smiling naturally [

9]. The validated German version of this grading instrument was also used in this case [

19]. The calculation is made using the formulas given on the assessment form, with 100 points corresponding to normal facial function and 0 points corresponding to complete facial nerve palsy [

20]. Alternative grading systems such as the House-Brackmann score or the Stennert-Parese index, which also serve to assess the functionality and symmetry of the face, were not used in the international setting due to the recommendation to use the Sunnybrook Facial Nerve Grading System as standard [

21].

2.7. Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Distribution of continuous data was described using mean values, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum. Qualitative data were presented in absolute and relative frequencies. The EMG amplitudes of the two halves of the face were initially evaluated descriptively on a daily basis. Not all patients were connected to the EMG measurement directly on Monday of the first training week, the actual first training day, or were only able to record EMG amplitudes on the following weekdays due to public holidays. For this reason, the EMG amplitudes were not only plotted according to the weekdays of the training, but were also instead assigned to training days one to a maximum of nine in the order of the recorded values to improve comparability. Assuming a normal distribution of the EMG amplitudes [

22,

23,

24], the question of a significant side difference between the diseased and healthy half of the face was investigated using a t-test for samples with paired values [

25] for the individual training. The following limits apply to the Cohen's d effect size provided: from 0.2 there is a small effect size, from 0.5 a medium effect size and from 0.8 a large effect size [

26]. To assess the influence of training over time on the EMG amplitudes, these were analyzed separately for the diseased and healthy half of the face using a single-factor analysis of variance with repeated measures to test for significant changes in the amplitudes for each possible pairwise combination of training days. The advantage of this test is that it considers the independence of the individual measurement times. A Bonferroni correction was not performed, as this is generally considered too conservative and comparatively few significant results are obtained [

25,

27,

28].

A single-factor analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to investigate the correlation between the changes in EMG amplitudes and the respective therapist. First, the following 3 categories of therapists were formed: 1) therapist A over the entire training period; 2) therapist B over the entire training period and 3) change of therapist within the training period. The EMG amplitudes of all training days on both sides of the face were considered under the influence of the three categories of therapists as covariates. According to common convention, from eta-square = 0.3 is referred to as a medium effect and from eta-square = 0.5 as a strong effect [

25]. For all statistical tests, significance was two-sided and set to p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients' Characteristics

A total of 30 patients were included (76.7% female; median age at start of the training: 48.62 ± 12.41 years,

Table 2). A variety of etiologies of facial nerve palsy were recorded in the patient population. With 12 cases (40.0%), idiopathic palsy occurred most frequently, followed by nine cases (30.0%) after removal of a benign tumor. On average, patients were able to start the intensified biofeedback training 2.80 ± 2.41 years after the initial diagnosis (range: 1.12 to 10.99 years). 12 patients (40.0%) completed only 8 training days between T1 and T2 respectively 3 patients (10.0%) completed only 7 training days of the maximum of nine possible observed training days between the first and second measurement dates due to public holidays and organizational delays on the day of admission.

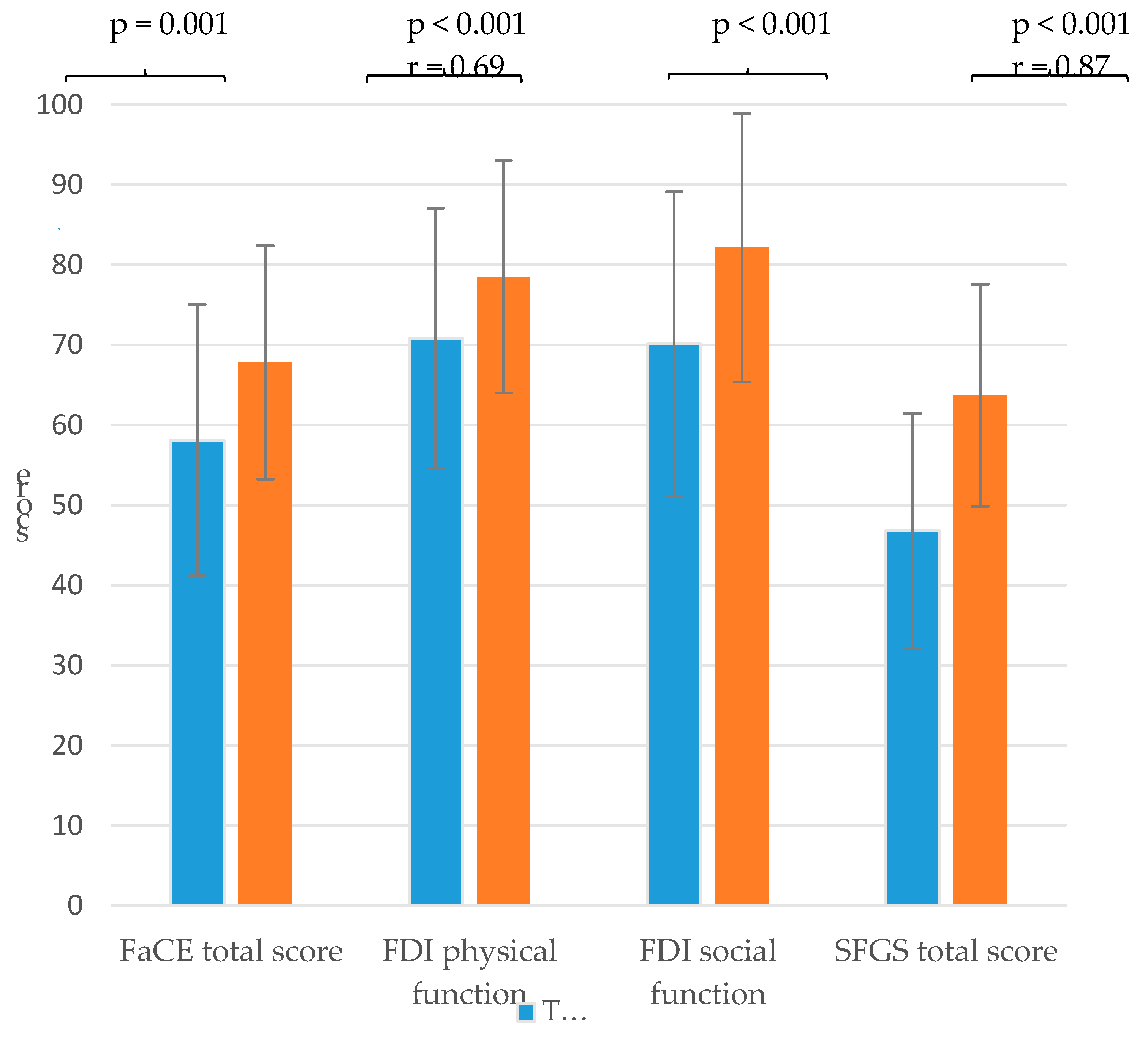

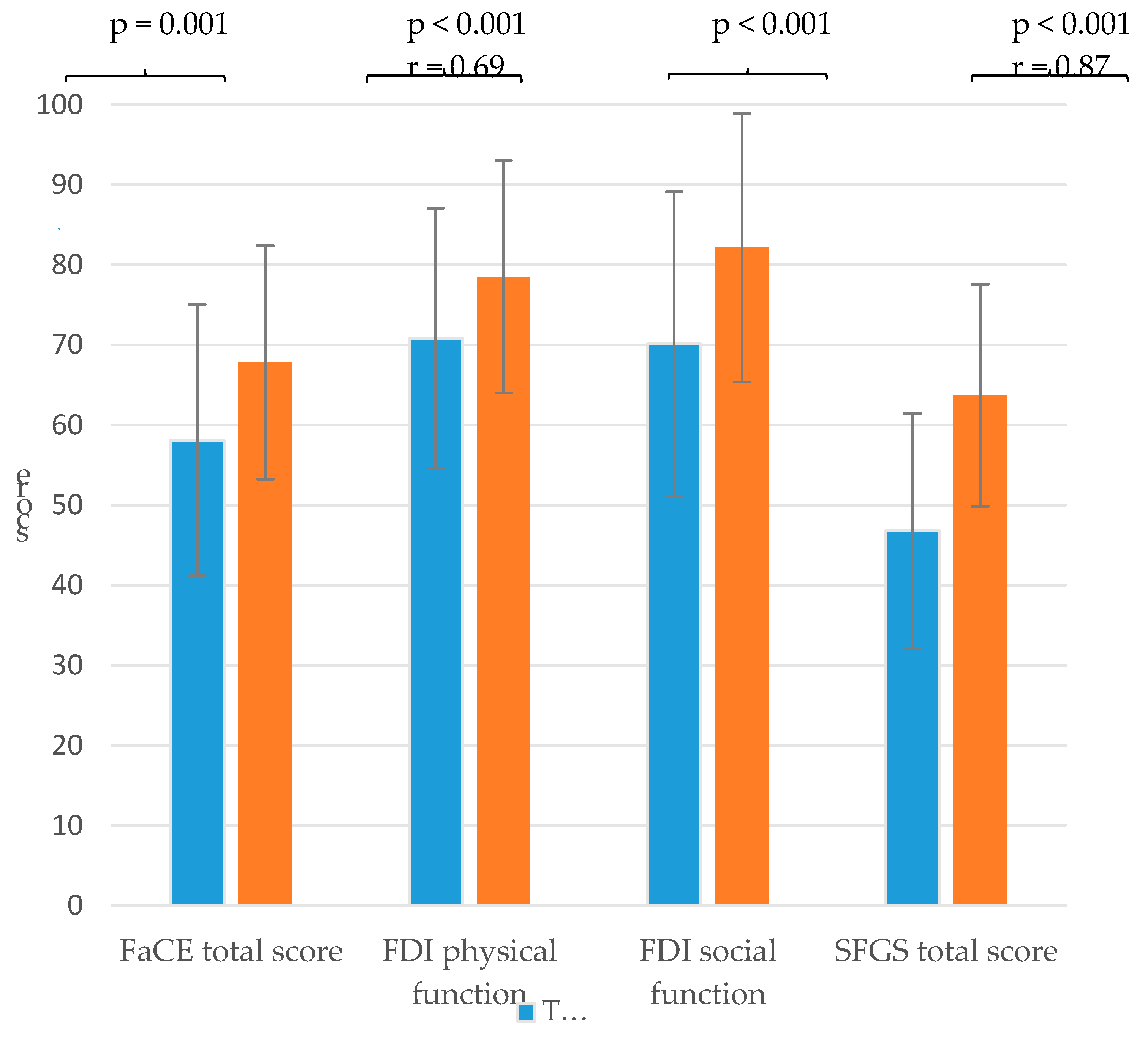

3.2. Facial Grading and Facial Palsy-Related Quality of Life

With regard to the facial palsy-related quality of life of the patients, the facial paresis training resulted in a significantly higher physical and social function score of FDI and a higher FaCE total score with a medium effect size. Furthermore, the training also resulted in a significant increase in the mean value of the SFGS with a large effect size (

Figure 4,

Appendix A Table A1).

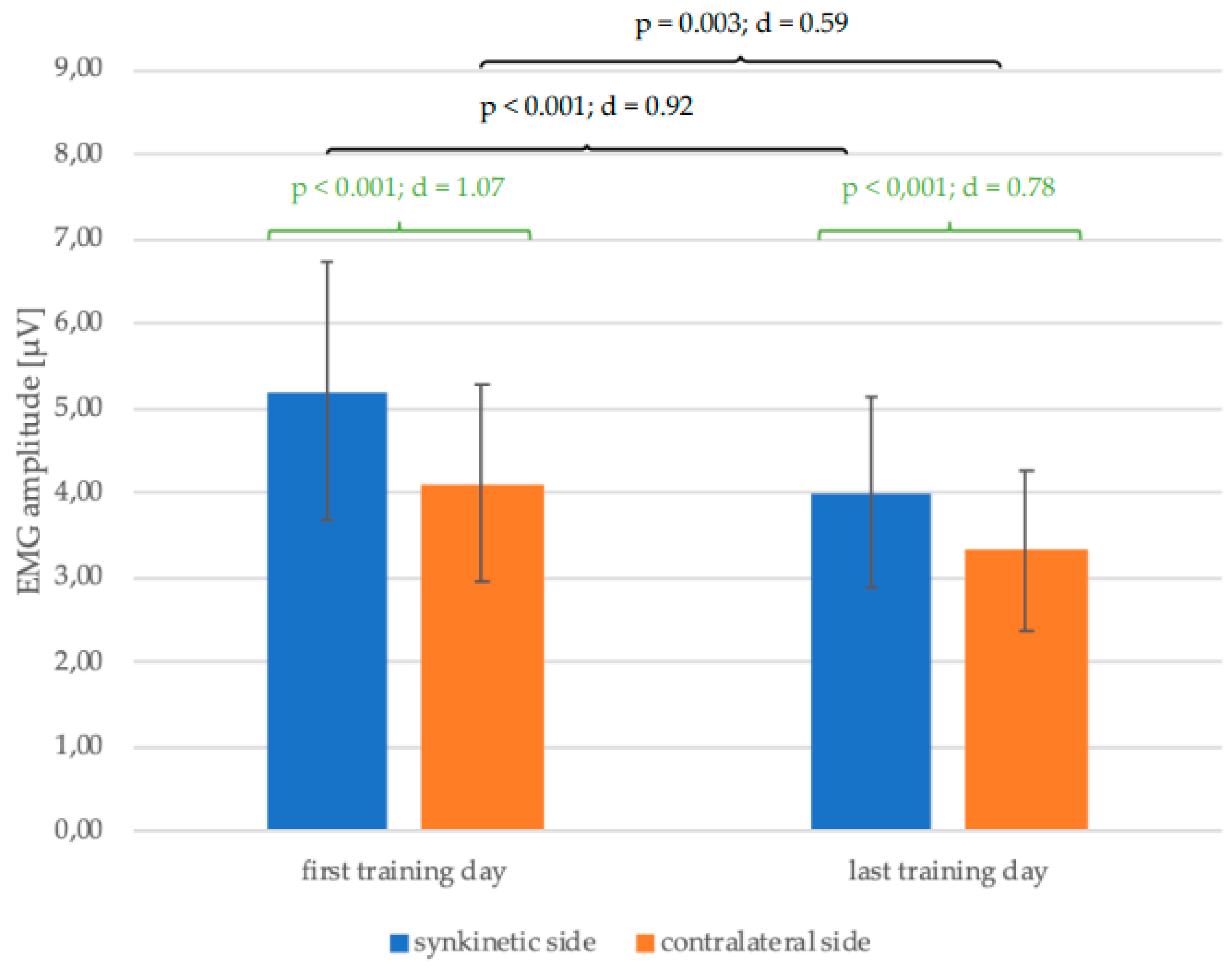

3.3. EMG Amplitudes

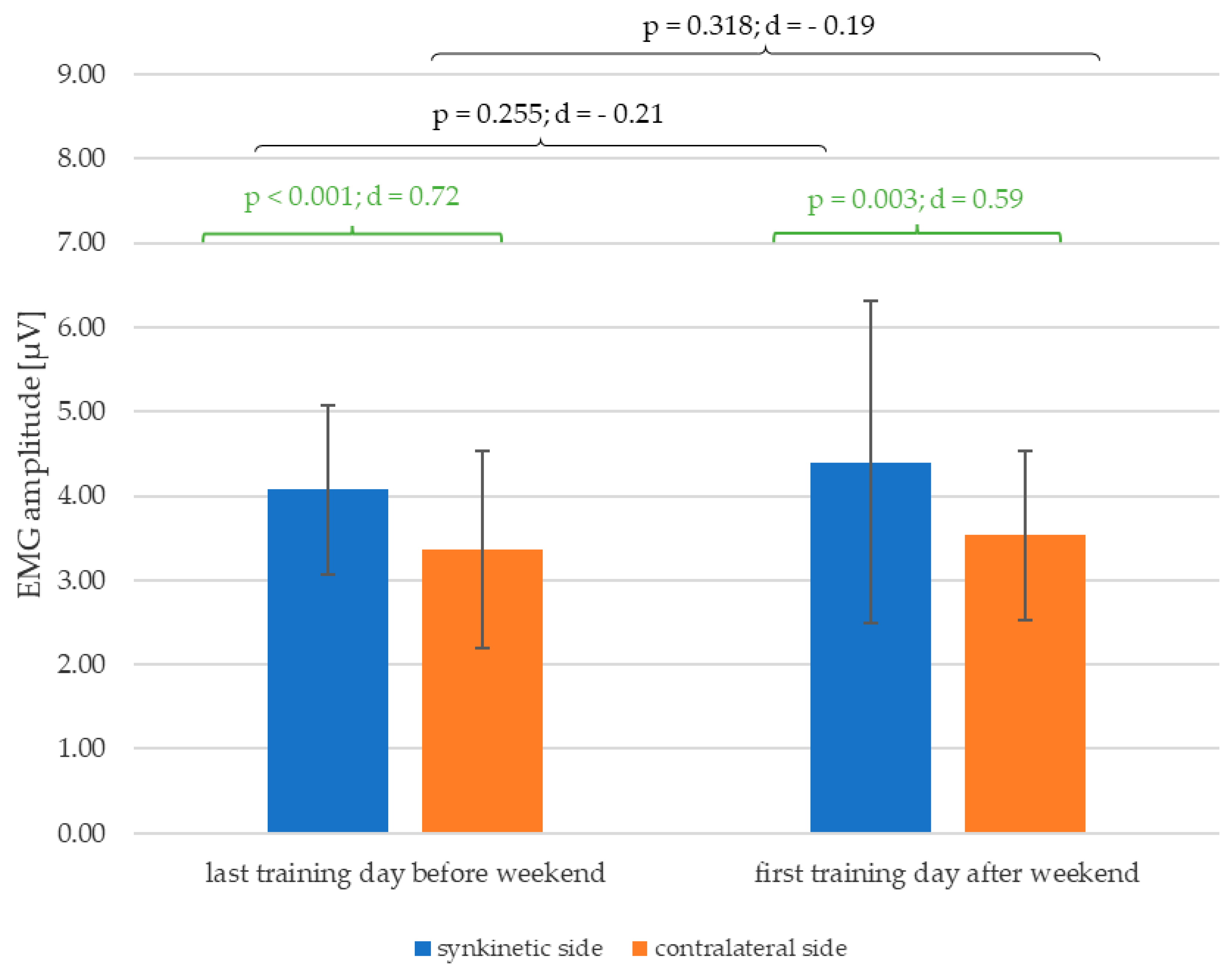

Figure 5 shows a reduction in the mean values of the EMG amplitudes of both halves of the face with completion of the training from the first to the last training day of all 30 patients. This change was significant for both the synkinetic (p < 0.001; d = 0.92) and contralateral (p = 0.003; d = 0.59) side with much higher effect size of Cohen's d on the synkinetic side (0.92 > 0.59). The EMG amplitudes of the synkinetic side were significantly higher than those of the contralateral side at both time points before and after training. This side difference, which was higher on the synkinetic side at the beginning of training (p < 0.001; d = 1.07), was lower but still present on the last day of training (p < 0.001; d = 0.78).

As shown in

Figure 6, the significant lateral difference in the EMG amplitudes of both halves of the face, which already existed at the last training day of the first week of training before the weekend (p < 0.001; d = 0.72), is still detectable for the first training day of the second week of training after the weekend (p < 0.001; d = 0.59) with at least a medium effect size. Furthermore, there was a trend of enlargement of mean values of the EMG amplitude of both halves of the face after the weekend in-between the training.

When comparing the EMG amplitudes of both halves of the face in pairs on each training day (

Figure 7), it is noticeable that up to and including the eighth day of training there was a significant difference between the synkinetic and contralateral side for the patient cohort under consideration, with at least medium to large effect sizes for Cohen's d. The EMG amplitudes of the synkinetic side were significantly higher than those of the contralateral side. After completion of the ninth day of training, no significant side difference (p = 0.058) could be determined with a medium effect size (Cohen's d = 0.53). But to this late time point of the training weeks, only n = 15 patients were still participating in the study, so the lack of significance is mostly explained by the lower number of subjects.

On the synkinetic side, there was a significant reduction in the EMG amplitudes of the pre-training measurements on the first training day compared to all other days as objective outcome measure of the training progresses. No significant change could be demonstrated for all other possible combinations of training days two to nine (

Table 3).

On the contralateral side, a significant reduction in EMG amplitudes could be measured from the first to the third, fifth and seventh to ninth day of training as objective outcome measure of the training progresses. Further significant differences could be demonstrated for the following combinations of training days: day 2 and 5; day 2 and 8, day 5 and 6, day 6 and 9 (

Table 4).

As shown in

Table 5, no significant influence of the respective instructed therapists or a change of therapist on the EMG amplitudes of the synkinetic (p = 0.891) and contralateral (p = 0.450) side of the face could be demonstrated.

4. Discussion

Similar to previous studies, a significant improvement in facial nerve palsy-related quality of life was also demonstrated for the patient cohort of the present study after completing the biofeedback training using the established patient-reported outcome measures FaCE and FDI [

14]. Again, a significant improvement in the objective grading of the SFGS by an examiner independent of the training was also demonstrated [

9]. Compared to other subjective measurement instruments, such as the House-Brackmann Scale, the SFGS is currently considered the most suitable because it can also be used to record very small changes in synkinesis after a therapeutic intervention. Another advantage is the very good intra- and inter-rater reliability [

21]. Dalla Toffola et al. also used the SFGS and were able to demonstrate that both - isolated training with the mirror and isolated training with EMG biofeedback - are effective. There was no significant difference between the two therapy groups with or without mirror [

29].

Based on this, the results of this study provide further insights into the pathophysiology of the therapeutic effect of combined biofeedback training in facial nerve palsy. Over the course of the nine observed training days, there was a significant decrease in the muscular tension of both halves of the face quantified via surface EMG during relaxation. The mean values of the EMG amplitudes of the affected side were significantly greater than those of the contralateral side. Only at the end of the training weeks after 9 days, when the training group was reduced down to n = 15 patients no significant side difference (p = 0.058) could be determined. In this respect, the biofeedback training at Facial-Nerve-Center in Jena should not be shortened with currently 10 training days supervised by specialized therapists.

At the start of the second week of training after the weekend, an increase in amplitudes was recognizable on both sides of the face, although this did not prove to be significant. Apparently, a break from training with the EMG feedback system over the weekend does not worsen the training progress significantly, but at least reverse the trend of reduced EMG values from training day to training day. Furthermore, the choice of therapist or a change of therapist during the training course has no influence on the change in EMG amplitudes over the training period. That can be interpreted as a sign for a good standardization and reproducibility of our training program.

In other studies, a further possibility for objectifying the training effects of rehabilitation programs for facial palsy was demonstrated by measuring changes in the opening width of the eyes on the basis of still images from video recordings of facial movements. For mirror-supported training, a reduction in asymmetries in the intervention group compared to the control group without therapy during synkinetic movements could be demonstrated [

30,

31]. The authors are aware that by examining EMG amplitudes during relaxation in this study, they have not contributed to a more uniform view of the therapeutic effects of facial paresis biofeedback training.

Also, in comparison to other studies, there was no control group with or without other therapeutic intervention such as physiotherapy in this study due to the complex implementation of the partial inpatient facial biofeedback training [

29,

32,

33]. As this biofeedback training is based on a fixed combination of visual and EMG-supported biofeedback, it was not possible to attribute the proven therapeutic effects to a single biofeedback modality. In line with the results of the review by Franz et al. [

34], it was shown that the amplitudes of the surface EMG in an open derivation are easy to record in everyday therapy and represent a further possibility for objectively recording therapy effects over time. The low invasiveness of this measurement method and the lower dependence of the results on the examiner compared to grading are also advantageous. In addition, the method offers the possibility of not only recognizing externally visible changes, but also recording the electrophysiological changes that occur directly in the facial musculature after completing biofeedback training for facial palsy. This showed that the recording of EMG amplitudes can also be used to record training successes within short observation periods. In the long term, the patients have to integrate their exercises into everyday life on their own, so that a further EMG-recording of the mimic muscles at the follow-up appointment after six months would be interesting for the investigation of long-term therapy effects in further studies.

5. Conclusions

It was shown that electrophysiological changes in the facial musculature and thus also the therapeutic effects of combined biofeedback training in patients with post-paralytic synkinetic facial nerve palsy can be objectively recorded by means of an openly visible surface EMG recording.

This finding may be useful for future randomized controlled studies. By extending the 2-channel EMG to a multi-channel examination, electrophysiological changes could be specifically examined for individual facial muscles in the future. The use of imaging techniques such as sonography or MRI, but also 3d videos or quantitatively analyzed photo series would also be conceivable for the objective detection of structural changes in the facial musculature following biofeedback training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.H. and G.F.V.; methodology, I.H., O.G.-L., G.F.V.; software, I.H.; validation, O.G.-L., I.H.; formal analysis, I.H.; investigation, I.H.; resources, O.G.-L., G.F.V.; data curation, I.H.; writing—original draft preparation, I.H.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, I.H.; supervision, G.F.V.; project administration, I.H.; funding acquisition, O.G.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Orlando Guntinas-Lichius acknowledges support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), grant GU-463/12-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany (protocol code No. 2022-2589_1-BO; approved on 05 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank the therapists Eva Miltner and Hendrik Möbius for their introduction to the training concept and support with the recording of training documentation data. We would also like to thank the patients for participating in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Written instructions on the documentation of facialis paresis training.

Figure A1.

Written instructions on the documentation of facialis paresis training.

Table A1.

Changes of Facial Clinemetric Evaluation (FaCE), Facial Disability Index (FDI) and Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS) and its subscores at baseline before start of the trainng (T1) and at the end of the training (T2).

Table A1.

Changes of Facial Clinemetric Evaluation (FaCE), Facial Disability Index (FDI) and Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS) and its subscores at baseline before start of the trainng (T1) and at the end of the training (T2).

| Item/Scores |

T1 |

T2 |

T1-T2 |

| Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

p-value |

effect size r |

| FaCE Facial Movement Score |

44.2 ± 19.8 |

51.1 ± 19.0 |

0.015 |

0.445 |

| FaCE Facial Comfort Score |

49.4 ± 25.0 |

62.8 ± 20.3 |

0.005 |

0.512 |

| FaCE Oral Function Score |

74.2 ± 22.5 |

79.58 ± 17.8 |

0.055 |

0.350 |

| FaCE Eye Comfort Score |

52.5 ± 27.9 |

60.4 ± 28.8 |

0.034 |

0.388 |

| FaCE Lacrimal Control Score |

65.8 ± 24.1 |

71.7 ± 28.4 |

0.071 |

0.330 |

| FaCE Social Function Score |

67.9 ± 26.1 |

81.0 ± 19.7 |

0.001 |

0.591 |

| FaCE Total Score |

58.1 ± 16.9 |

67.8 ± 14.6 |

0.001 |

0.634 |

| FDI physical function score |

70.8 ± 16.2 |

78.5 ± 14.5 |

<0.001 |

0.688 |

| FDI social function score |

70.1 ± 19.0 |

82.1 ± 16.8 |

<0.001 |

0.682 |

| SFGS Resting symmetry score |

10.7 ± 4.3 |

6.3 ± 3.9 |

<0.001 |

0.775 |

| SFGS Voluntary movement score |

64.8 ± 13.9 |

74.3 ± 11.7 |

<0.001 |

0.846 |

| SFGS Synkinesis score |

7.4 ± 2.4 |

4.2 ± 1.6 |

<0.001 |

0.802 |

| SFGS Total score |

46.8 ± 14.7 |

63.7 ± 13.8 |

<0.001 |

0.874 |

References

- Volk, G.F.; Klingner, C.; Finkensieper, M.; Witte, O.W.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. Prognostication of recovery time after acute peripheral facial palsy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Prengel, J.; Cohen, O.; Mäkitie, A.A.; Vander Poorten, V.; Ronen, O.; Shaha, A.; Ferlito, A. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy of facial synkinesis: A systematic review and clinical practice recommendations by the international head and neck scientific group. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 1019554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J. , Al-Hassani, F., & Kannan, R. Facial nerve disorder: a review of the literature. IJS Oncology 2018, 3, e65. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, C.J.; Neely, J.G. Patterns of facial nerve synkinesis. Laryngoscope 1996, 106, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizzadeh, B.; Nduka, C. Management of Post-Facial Paralysis Synkinesis; Elsevier Health Sciences: 2021.

- Mark, V. W. , & Taub, E. Constraint-induced movement therapy for chronic stroke hemiparesis and other disabilities. Restorative neurology and neuroscience 2004, 22, 317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlet, C.; Williamson, H.; Hotton, M.; Rumsey, N. 'Your face freezes and so does your life': A qualitative exploration of adults' psychosocial experiences of living with acquired facial palsy. Br J Health Psychol 2021, 26, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseman, J.; Mehta, R.P. Management of synkinesis. Facial Plast Surg 2008, 24, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, G.F.; Roediger, B.; Geißler, K.; Kuttenreich, A.M.; Klingner, C.M.; Dobel, C.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. Effect of an Intensified Combined Electromyography and Visual Feedback Training on Facial Grading in Patients With Post-paralytic Facial Synkinesis. Front Rehabil Sci 2021, 2, 746188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Noonan, K.M.; Freeman, M.; Ayers, C.; Morasco, B.J.; Kansagara, D. Efficacy of Biofeedback for Medical Conditions: an Evidence Map. J Gen Intern Med 2019, 34, 2883–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baricich, A.; Cabrio, C.; Paggio, R.; Cisari, C.; Aluffi, P. Peripheral Facial Nerve Palsy: How Effective Is Rehabilitation? Otology & Neurotology 2012, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, J.R.; Teixeira, E.C.; Moreira, M.D.; Fávero, F.M.; Fontes, S.V.; Bulle de Oliveira, A.S. Effects of exercises on Bell's palsy: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Otol Neurotol 2008, 29, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, C.; Beurskens, C.; Diels, J.; MacDowell, S.; Rankin, S. Consensus Among International Facial Therapy Experts for the Management of Adults with Unilateral Facial Palsy: A Two-Stage Nominal Group and Delphi Study. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, S. Veränderungen der allgemeinen und krankheitsspezifischen Lebensqualität nach Fazialis-Parese-Training mit EMG-Biofeedback am Universitätsklinikum Jena bei Patienten mit Defektheilung nach. Fazialisparese. Dissertation, Jena, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hoche, E. Evaluation eines Biofeedback-Trainings für Patienten mit postparalytischen Synkinesien nach peripherer Fazialisparese mittels Multikanal-Oberflächen-EMG der intrinsischen und extrinsischen aurikulären. Muskulatur. Dissertation, Jena, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Volk, G.F.; Steigerwald, F.; Vitek, P.; Finkensieper, M.; Kreysa, H.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. [Facial Disability Index and Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale: validation of the German versions]. Laryngorhinootologie 2015, 94, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.B.; Gliklich, R.E.; Boyev, K.P.; Stewart, M.G.; Metson, R.B.; McKenna, M.J. Validation of a patient-graded instrument for facial nerve paralysis: the FaCE scale. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanSwearingen, J.M.; Brach, J.S. The Facial Disability Index: reliability and validity of a disability assessment instrument for disorders of the facial neuromuscular system. Phys Ther 1996, 76, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T.; Lorenz, A.; Volk, G.F.; Hamzei, F.; Schulz, S.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. [Validation of the German Version of the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System]. Laryngorhinootologie 2017, 96, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.G.; Fradet, G.; Nedzelski, J.M. Development of a sensitive clinical facial grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996, 114, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, A.Y.; Gurusinghe, A.D.R.; Gavilan, J.; Hadlock, T.A.; Marcus, J.R.; Marres, H.; Nduka, C.C.; Slattery, W.H.; Snyder-Warwick, A.K. Facial nerve grading instruments: systematic review of the literature and suggestion for uniformity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015, 135, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T. Oberflächen-EMG-Untersuchungen zum Kontraktionsverhalten der Skelettmuskulatur unter lokaler Wärmeanwendung. lmu, 2002.

- Nazarpour, K.; Al-Timemy, A.H.; Bugmann, G.; Jackson, A. A note on the probability distribution function of the surface electromyogram signal. Brain Res Bull 2013, 90, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahib, M. Die interindividuelle Variabilität der oberflächen-elektromyographischen Aktivitätsverteilung von M. masseter und M. temporalis während des. Kauvorgangs. Dissertation, Jena, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, C. Basiswissen Medizinische Statistik; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 2019.

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortz, J.; Schuster, C. Statistik für Human-und Sozialwissenschaftler: Limitierte Sonderausgabe; Springer-Verlag: 2011.

- Fahrmeir, L.; Heumann, C.; Künstler, R.; Pigeot, I.; Tutz, G. Statistik: Der Weg zur Datenanalyse; Springer-Verlag: 2016.

- Dalla Toffola, E.; Tinelli, C.; Lozza, A.; Bejor, M.; Pavese, C.; Degli Agosti, I.; Petrucci, L. Choosing the best rehabilitation treatment for Bell’s palsy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2012, 48, 635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, S.; Kondo, K.; Yoshitomi, A.; Kanemaru, A.; Nakaya, M.; Yamasoba, T. Efficacy of Mirror Biofeedback Rehabilitation on Synkinesis in Acute Stage Facial Palsy in Children. Otol Neurotol 2021, 42, e936–e941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Toda, N.; Sakamaki, K.; Kashima, K.; Takeda, N. Biofeedback rehabilitation for prevention of synkinesis after facial palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003, 128, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, B.; Nedzelski, J.M.; McLean, J.A. Efficacy of feedback training in long-standing facial nerve paresis. The Laryngoscope 1991, 101, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurskens, C.H.G.; Heymans, P.G. Positive Effects of Mime Therapy on Sequelae of Facial Paralysis: Stiffness, Lip Mobility, and Social and Physical Aspects of Facial Disability. Otology & Neurotology 2003, 24, 677–681. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, L.; de Filippis, C.; Daloiso, A.; Biancoli, E.; Iannacone, F.P.; Cazzador, D.; Tealdo, G.; Marioni, G.; Nicolai, P.; Zanoletti, E. Facial surface electromyography: A systematic review on the state of the art and current perspectives. American Journal of Otolaryngology 2024, 45, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Training setting. The typical training setup with two patients and a therapist sitting opposite is shown on the left side. The activity of the facial muscles is recorded using electromyography via adhesive electrodes and displayed on a screen to the left and right of a webcam-based mirror image as a two vertical feedback bars and numbers. Patients and therapist see the same screens.

Figure 1.

Training setting. The typical training setup with two patients and a therapist sitting opposite is shown on the left side. The activity of the facial muscles is recorded using electromyography via adhesive electrodes and displayed on a screen to the left and right of a webcam-based mirror image as a two vertical feedback bars and numbers. Patients and therapist see the same screens.

Figure 2.

Overview of measurement times and recorded parameters (T1- first examination date; T2- second examination date. FaCE: Facial Clinemetric Evaluation; FDI: Facial Disability Index; SFGS: Sunnybrook Facial Grading System). Grey: assessment-day; Blue: intervention period; Green: no intervention.

Figure 2.

Overview of measurement times and recorded parameters (T1- first examination date; T2- second examination date. FaCE: Facial Clinemetric Evaluation; FDI: Facial Disability Index; SFGS: Sunnybrook Facial Grading System). Grey: assessment-day; Blue: intervention period; Green: no intervention.

Figure 3.

Tabular template to document the ability to relax.

Figure 3.

Tabular template to document the ability to relax.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the mean values and standard deviation of the sum scores of the Facial Clinimetric Evaluation (FaCE), the Facial Disability Index (FDI) and the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS) of the the baseline measuremen before start of the training (T1) and second measurement at the end of the training (T2) with p-values and effect size r.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the mean values and standard deviation of the sum scores of the Facial Clinimetric Evaluation (FaCE), the Facial Disability Index (FDI) and the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS) of the the baseline measuremen before start of the training (T1) and second measurement at the end of the training (T2) with p-values and effect size r.

Figure 5.

Change in the mean values and standard deviation of the EMG amplitudes from the first to the last training day (black) and the side differences (green) on the first and last training day with p-values and Cohen's d for all 30 patients.

Figure 5.

Change in the mean values and standard deviation of the EMG amplitudes from the first to the last training day (black) and the side differences (green) on the first and last training day with p-values and Cohen's d for all 30 patients.

Figure 6.

Change in the mean values and standard deviation of the EMG amplitudes over the weekend between the first and second week of training in between (black) and the side differences (green) on the day before and after the weekend with p-values and Cohen's d.

Figure 6.

Change in the mean values and standard deviation of the EMG amplitudes over the weekend between the first and second week of training in between (black) and the side differences (green) on the day before and after the weekend with p-values and Cohen's d.

Figure 7.

Change in the mean values and standard deviation of the EMG amplitudes from each training day 1 - 9 of both halves of the face and indication of the side differences with p-values and Cohen's d; significant results marked in bold; n – number of patients.

Figure 7.

Change in the mean values and standard deviation of the EMG amplitudes from each training day 1 - 9 of both halves of the face and indication of the side differences with p-values and Cohen's d; significant results marked in bold; n – number of patients.

Table 1.

Overview of the most frequently performed facial paresis training exercises.

Table 1.

Overview of the most frequently performed facial paresis training exercises.

| List of exercises |

|---|

| Long eyelid closure |

| Closed smile |

| Open smile |

| Pursed lips/ kissing mouth |

| Closed smile with transition to kissing mouth |

| Pursed lips with transition to showing teeth |

| Open smile with transition to "O"/"U" |

| Letter exercise O/U |

| Letter exercise E/I |

| Letter exercise A |

| Alternating one-sided smile, then both sides |

| Show teeth |

| wrinkle nose |

| Raise/lower eyebrows |

| Puff out cheeks |

Table 2.

Patients' Characteristics.

Table 2.

Patients' Characteristics.

| Parameter |

Absolute (N) |

Relative (%) |

| All |

30 |

100.0 |

| Gender |

|

| Male |

7 |

23.3 |

| Female |

23 |

76.7 |

| Handedness |

|

| Right |

30 |

100.0 |

| Left |

0 |

0 |

| Etiology |

|

| idiopathic |

12 |

40.0 |

| postoperative with benign tumor |

9 |

30.0 |

| Ramsay Hunt syndrome |

6 |

20.0 |

| traumatic |

3 |

10.0 |

| congenital |

0 |

0 |

| postoperative with malignant tumor |

0 |

0 |

| cerebral insult |

0 |

0 |

| Localization of the paresis |

|

| right |

15 |

50.0 |

| left |

15 |

50.0 |

| Presence of oro-ocular synkinesis |

|

| yes |

30 |

100.0 |

| no |

0 |

0 |

| Therapist week 1 |

|

| Therapist A |

10 |

33.3 |

| Therapist B |

20 |

66.7 |

| Therapist week 2 |

|

| Therapist A |

19 |

63.3 |

| Therapist B |

11 |

36.7 |

| Number of training days completed between the first (T1) and second (T2) measurement point |

|

| 9 training days |

15 |

50.0 |

| 8 training days |

12 |

40.0 |

| 7 training days |

3 |

10.0 |

| |

Mean ± SD |

Median, range |

| Age at beginning of facial palsy in years |

45.88 ± 13.71 |

47.33; 18.45–70.31 |

| Age at start of training in years |

48.62 ± 12.41 |

48.84; 24.05–71.43 |

| Height in m |

1.71 ± 0.09 |

1.70; 1.56–1.89 |

| Weight in kg |

78.90 ± 17.84 |

72.5; 48.0–150.0 |

| BMI in kg/m2

|

26.08 ± 6.43 |

24.95; 16.61–43.36 |

| Period between beginning of facial palsy and reinnervation in years (n = 28*) |

0.33 ± 0.25 |

0.27; 0.04–1.03 |

| Time between beginning of facial palsy and first contact with Facial-Nerve-Center in years |

2.11 ± 2.30 |

1.21; 0.44–9.79 |

| Time between beginning of facial palsy and first measurement (T1) in years |

2.80 ± 2.41 |

1.84; 1.12–10.99 |

Table 3.

P-values (top row, significant results marked in bold) of the change in EMG amplitudes of the synkinetic side for each possible combination of training days with 95% confidence interval in brackets.

Table 3.

P-values (top row, significant results marked in bold) of the change in EMG amplitudes of the synkinetic side for each possible combination of training days with 95% confidence interval in brackets.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 1 |

|

0.017

(0.2 – 1.7) |

0.001

(0.6 – 1.9) |

0.018

(0.2 – 2.1) |

0.002

(0.6 – 2.2) |

0.011

(0.3 – 1.9) |

0.003

(0.6 – 2.4) |

0.001

(0.7 – 2.2) |

0.001

(0.7 – 2.1) |

| 2 |

0.017

(0.2 – 1.7) |

|

0.202

(-0.8 – 0.2) |

0.549

(-1.0 – 0.6) |

0.118

(-1.0 – 0.1) |

0.570

(-0.8 – 0.5) |

0.121

(-1.3 – 0.2) |

0.066

(-1.1 – 0.0) |

0.097

(-1.0 – 0.1) |

| 3 |

0.001

(0.6 – 1.9) |

0.202

(-0.2 – 0.8) |

|

0.764

(-0.5 – 0.7) |

0.483

(-0.5 – 0.2) |

0.536

(-0.3 – 0.6) |

0.382

(-0.8 – 0.3) |

0.172

(-0.5 – 0.1) |

0.564

(-0.7 – 0.4) |

| 4 |

0.018

(0.2 – 2.1) |

0.549

(-0.6 – 1.0) |

0.764

(-0.7 – 0.5) |

|

0.374

(-0.7 – 0.3) |

0.879

(-0.7 – 0.8) |

0.327

(-1.0 – 0.3) |

0.305

(-0.9 – 0.3) |

0.516

(-1.0 – 0.5) |

| 5 |

0.002

(0.6 – 2.2) |

0.118

(-0.1 – 1.0) |

0.483

(-0.2 – 0.5) |

0.374

(-0.3 – 0.7) |

|

0.340

(-0.3 -0.8) |

0.688

(-0.7 – 0.5) |

0.601

(-0.4 – 0.3) |

0.938

(-0.6 – 0.6) |

| 6 |

0.011

(0.3 – 1.9) |

0.570

(-0.5 – 0.8) |

0.536

(-0.6 – 0.3) |

0.879

(-0.8 – 0.7) |

0.340

(-0.8 – 0.3) |

|

0.052

(-0.7 – 0.0) |

0.117

(-0.8 – 0.1) |

0.232

(-0.8 – 0.2) |

| 7 |

0.003

(0.6 – 2.4) |

0.121

(-0.2 – 1.3) |

0.382

(-0.3 – 0.8) |

0.327

(-0.3 – 1.0) |

0.688

(-0.5 – 0.7) |

0.052

(0.0 – 0.7) |

|

0.900

(-0.4 – 0.5) |

0.669

(-0.3 – 0.5) |

| 8 |

0.001

(0.7 – 2.2) |

0.066

(0.0 – 1.1) |

0.172

(-0.1 – 0.5) |

0.305

(-0.3 – 0.9) |

0.601

(-0.3 – 0.4) |

0.117

(-0.1 – 0.8) |

0.900

(-0.5 – 0.4) |

|

0.795

(-0.4 – 0.6) |

| 9 |

0.001

(0.7 – 2.1) |

0.097

(-0.1 – 1.0) |

0.564

(-0.4 – 0.7) |

0.516

(-0.5 – 1.0) |

0.938

(-0.6 – 0.6) |

0.232

(-0.2 – 0.8) |

0.669

(-0.5 – 0.3) |

0.795

(-0.6 – 0.4) |

|

Table 4.

P-values (top row, significant results marked in bold) of the change in EMG amplitudes of the contralateral side for each possible combination of training days with 95% confidence interval in brackets.

Table 4.

P-values (top row, significant results marked in bold) of the change in EMG amplitudes of the contralateral side for each possible combination of training days with 95% confidence interval in brackets.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 1 |

|

0.075

(-0.1 – 1.0) |

0.005

(0.2 – 1.0) |

0.050

(0.0 – 1.2) |

0.006

(0.3 – 1.6) |

0.128

(-0.2 – 1.2) |

0.018

(0.2 – 1.4) |

0.009

(0.2 – 1.3) |

0.006

(0.3 – 1.4) |

| 2 |

0.075

(-0.1 – 1.0) |

|

0.608

(-0.6 – 0.4) |

0.652

(-0.8 – 0.5) |

0.031

(-0.9 – 0.0) |

0.916

(-0.6 – 0.5) |

0.198

(-0.9 – 0.2) |

0.084

(-0.7 – 0.0) |

0.059

(-0.8 – 0.0) |

| 3 |

0.005

(0.2 – 1.0) |

0.608

(-0.4 – 0.6) |

|

0.935

(-0.4 – 0.4) |

0.147

(-0.8 – 0.1) |

0.714

(-0.4 – 0.6) |

0.409

(-0.7 – 0.3) |

0.377

(-0.6 – 0.2) |

0.158

(-0.7 – 0.1) |

| 4 |

0.050

(0.0 – 1.2) |

0.652

(-0.5 – 0.8) |

0.935

(-0.4 – 0.4) |

|

0.076

(-0.7 – 0.0) |

0.694

(-0.5 – 0.7) |

0.460

(-0.7 – 0.3) |

0.507

(-0.7 – 0.4) |

0.210

(-0.7 – 0.2) |

| 5 |

0.006

(0.3 – 1.6) |

0.031

(0.0 – 0.9) |

0.147

(-0.1 – 0.8) |

0.076

(0.0 – 0.7) |

|

0.039

(0.0 – 0.8) |

0.467

(-0.2 – 0.5) |

0.262

(-0.1 – 0.5) |

0.584

(-0.2 – 0.3) |

| 6 |

0.128

(-0.2 – 1.2) |

0.916

(-0.5 – 0.6) |

0.714

(-0.6 – 0.4) |

0.694

(-0.7 – 0.5) |

0.039

(-0.8 – 0.0) |

|

0.052

(-0.6 – 0.0) |

0.153

(-0.7 – 0.1) |

0.033

(-0.7 – 0.0) |

| 7 |

0.018

(0.2 – 1.4) |

0.198

(-0.2 – 0.9) |

0.409

(-0.3 – 0.7) |

0.460

(-0.3 – 0.7) |

0.467

(-0.5 – 0.2) |

0.052

(0.0 – 0.6) |

|

0.851

(-0.3 – 0.3) |

0.672

(-0.4 – 0.3) |

| 8 |

0.009

(0.2 – 1.3) |

0.084

(0.0 – 0.7) |

0.377

(-0.2 – 0.6) |

0.507

(-0.4 – 0.7) |

0.262

(-0.5 – 0.1) |

0.153

(-0.1 – 0.7) |

0.851

(-0.3 – 0.3) |

|

0.441

(-0.4 – 0.2) |

| 9 |

0.006

(0.3 – 1.4) |

0.059

(0.0 – 0.8) |

0.158

(-0.1 – 0.7) |

0.210

(-0.2 – 0.7) |

0.584

(-0.3 – 0.2) |

0.033

(0.0 – 0.7) |

0.672

(-0.3 – 0.4) |

0.441

(-0.2 – 0.4) |

|

Table 5.

Interaction between the change of the EMG amplitude and the therapists.

Table 5.

Interaction between the change of the EMG amplitude and the therapists.

| |

p-value |

partial η² |

| Interaction between the change of EMG amplitude of the synkinetic side and therapists A, therapist B and change of therapists |

0.891 |

0.365 |

| Interaction between the change of EMG amplitude of the contralateral side and therapists A, therapist B and change of therapists |

0.450 |

0.603 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).