Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

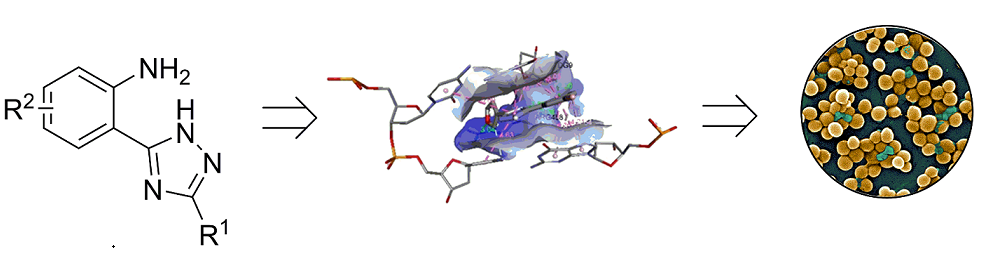

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

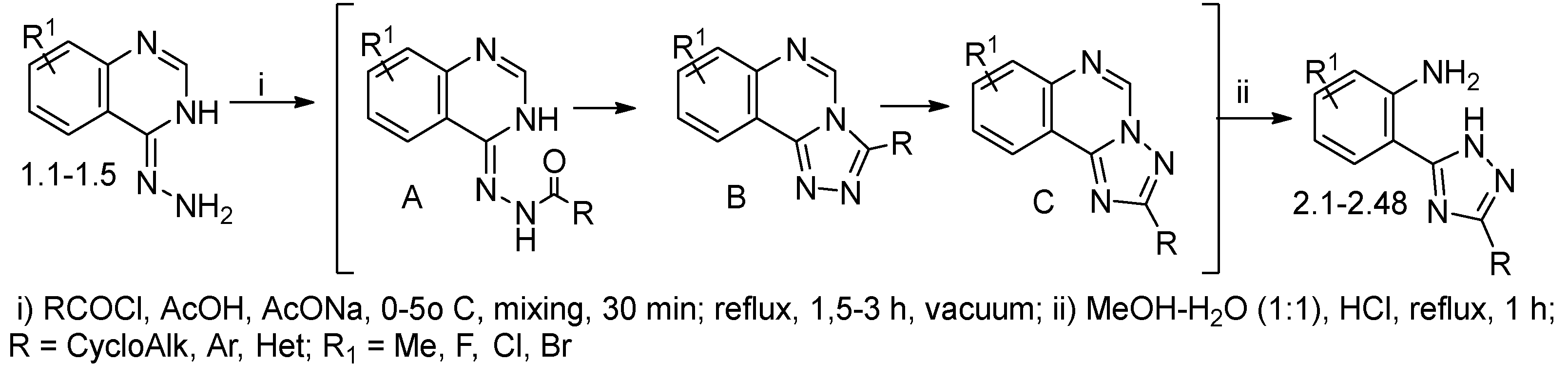

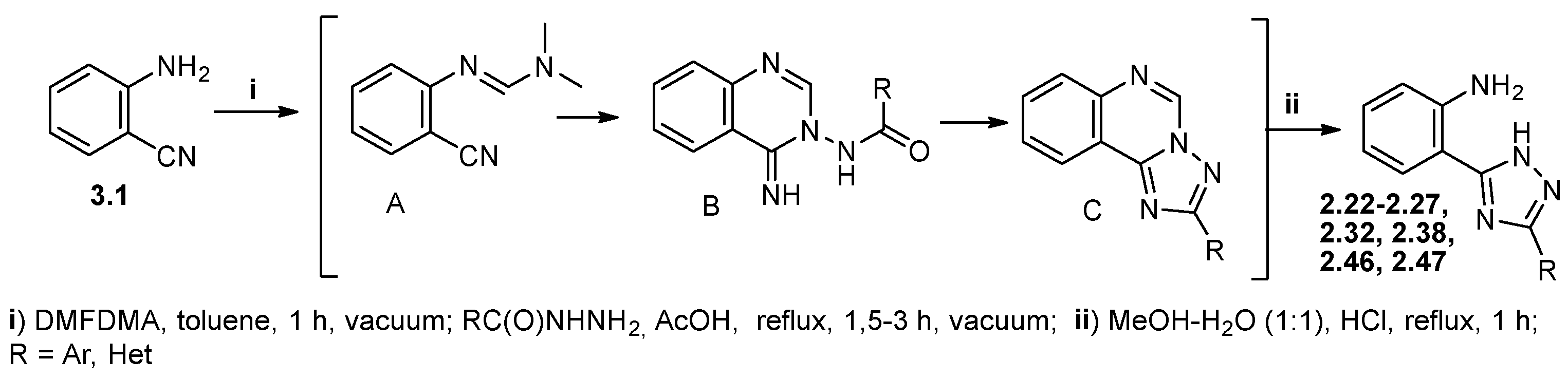

2.1. Chemical Studies

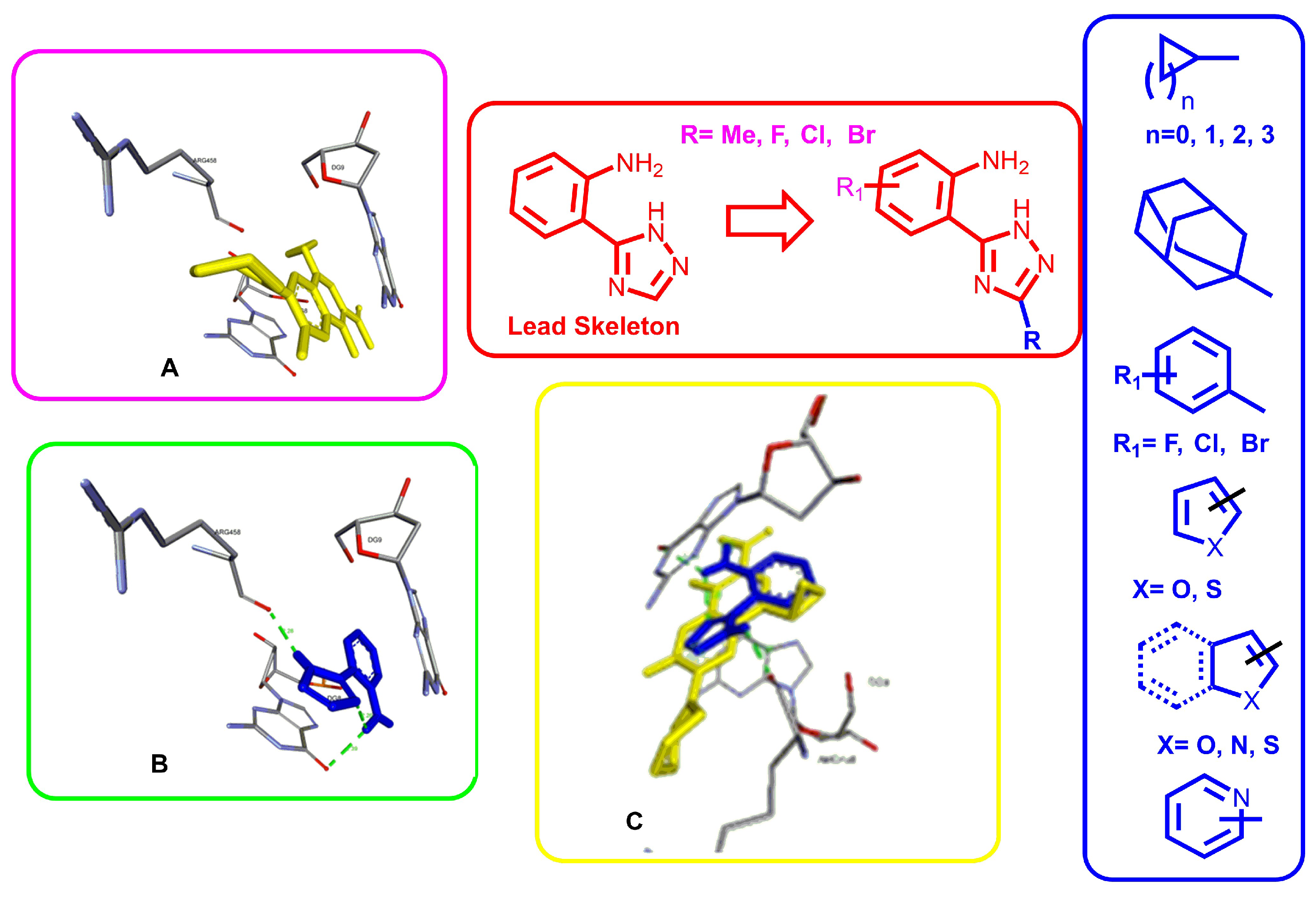

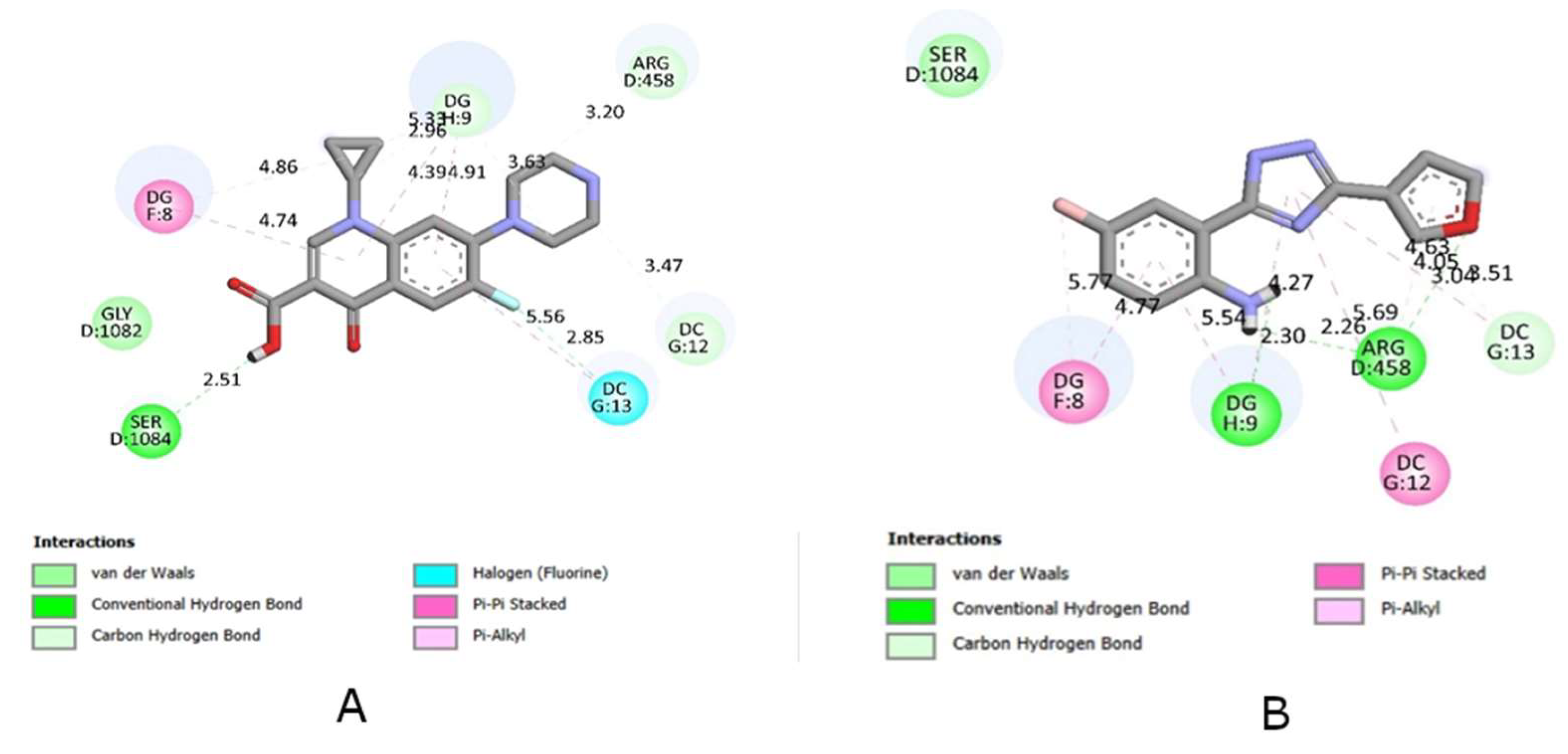

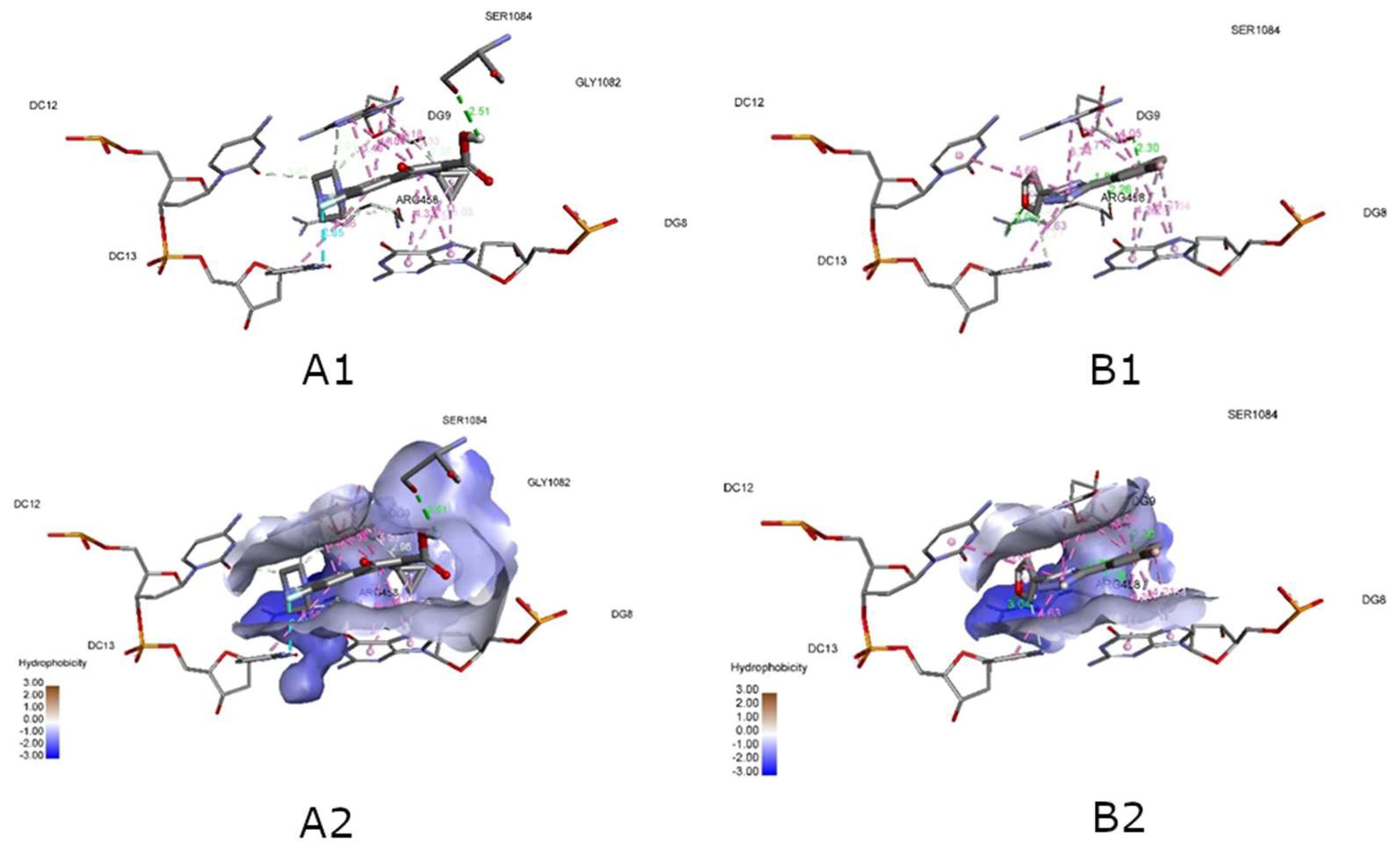

2.2. Molecular Docking Studies

2.3. Anti-Staphylococcal Activity of Synthesized Compounds

2.4. SAR-Analysis

- introduction of cyclopropane fragment to the 3rd position of the triazole fragment of the 2-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)aniline leads to the appearance of an antibacterial effect against St. aureus. The extension of the aliphatic cycle by one or more homologous units increases the antibacterial effect, and the presence of the classic “pharmacophoric” fragment of adamantane in the molecule leads to a high anti-staphylococcal effect. Conversely, modification of the aniline moiety of the molecule through the introduction of halogens results in a loss of antibacterial activity in nearly all instances. This phenomenon is likely associated with alterations in the “ligand-receptor” conformation.

- replacing the cycloalkyl fragment at the 3rd position of triazole cycle with phenyl fragment does not lead to a loss of anti-staphylococcal activity. Whereas the introduction of a halogen to the phenyl fragment in 3rd position leads to its reduction, the relocation of fluorine to the ortho position results in a significant increase thereof.

- introduction of 5 or 6 membered heterocyclic fragments to the 3rd position of triazole cycle, which are electron donors due to the heteroatom (O, N, S) unambiguously leads to high anti-staphylococcal activity. The aforementioned phenomenon is associated with an increase in π-electron interactions with nucleotides and, consequently, a greater similar content in the active site of the enzyme. Notably, the introduction of donor (methyl group) or acceptor (halogens) substituents to the aniline moiety leads to an enhancement of activity.

2.5. SwissADME Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthetic Section

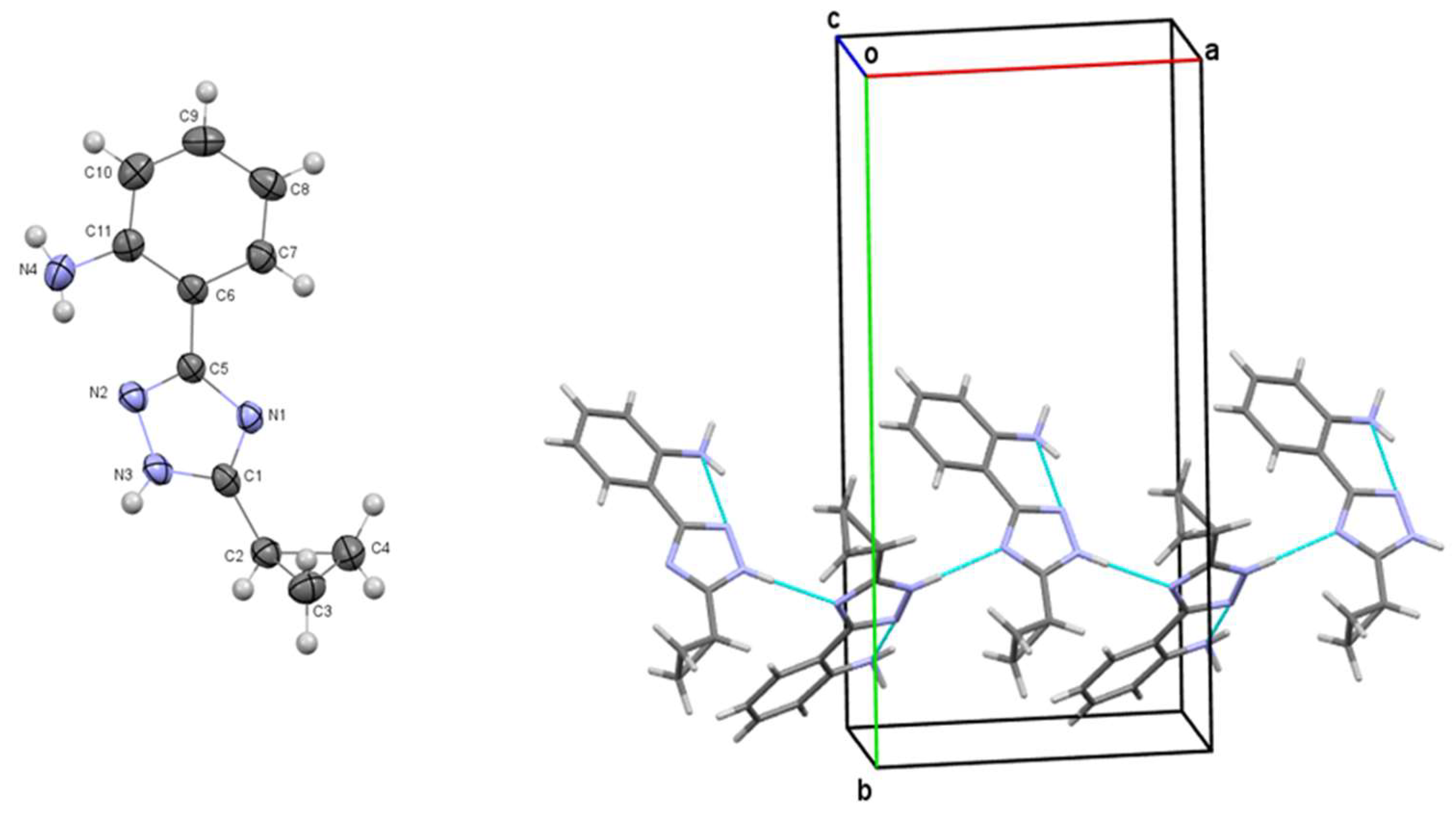

3.2. X-Ray Crystallographic Study of 2-(3-cyclopropyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)aniline (2.1)

3.3. Molecular Docking

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

3.5. SwissADME-Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Aleam, R. H. A.; George, R. F.; Georgey, H. H.; Abdel-Rahman H. M. Bacterial virulence factors: a target for heterocyclic compounds to combat bacterial resistance. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 36459-36482. [CrossRef]

- Koulenti, D.; Xu, E.; Mok, I. Y. S.; Song, A.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Armaganidis, A.; Lipman, J.; Tsiodras S. Novel Antibiotics for Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Positive Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2019, 7(8), 270. ttps://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7080270.

- Theuretzbacher U. Resistance drives antibacterial drug development. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2011, 11(5), 433–438. [CrossRef]

- Vimalah, V.; Getha, K.; Mohamad, Z. N.; Mazlyzam, A. L. A Review on Antistaphylococcal Secondary Metabolites from Basidiomycetes. Molecules 2020, 25, 5848. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Wright, G. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature, 2016, 529, 336–343. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Blasi, F.; Curtis, N.; Kaplan, S.; Lazzarotto, T.; Meschiari, M.; Mussini, C.; Peghin, M.; Rodrigo, C.; Vena, A.; Principi, N.; Bassetti M. New Antibiotics for Staphylococcus aureus Infection: An Update from the World Association of Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders (WAidid) and the Italian Society of Anti-Infective Therapy (SITA). Antibiotics 2023, 12, 742. [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. M.; Seiple, I. B.; Myers, A. G. The evolving role of chemical synthesis in antibacterial drug discovery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53(34), 8840-69. [CrossRef]

- Doytchinova, I. Drug Design-Past, Present, Future. Molecules 2022, 27(5), 1496. [CrossRef]

- Anstead, G.M.; Cadena, J.; Javeri, H. Treatment of infections due to resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Methods Mol Biol. 2014, 1085, 259-309. [CrossRef]

- Bisacchi, G. S.; Manchester, J. I. A New-Class Antibacterial–Almost. Lessons in Drug Discovery and Development: A Critical Analysis of More than 50 Years of Effort toward ATPase Inhibitors of DNA Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1(1), 4–41. [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Sankhe, K.; Suvarna, V.; Sherje, A.; Patel, K.; Dravyakar, B. DNA gyrase inhibitors: Progress and synthesis of potent compounds as antibacterial agents. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 923-938. [CrossRef]

- Durcik, M.; Tomašič, T.; Zidar, N.; Zega, A.; Kikelj, D.; Mašič, L. P.; Ilaš, J. ATP-competitive DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV inhibitors as antibacterial agents. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2019, 29(3), 171–180. [CrossRef]

- Dighe, S. N.; Collet, T. A. Recent advances in DNA gyrase-targeted antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 199, 112326. [CrossRef]

- Ruo-Jun, M.; Xu-Ping, Z.; Yu-Shun, Y.; Ai-Qin, J.; Hai-Liang Z. Recent Progress in Small Molecular Inhibitors of DNA Gyrase. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28(28), 5808-5830. [CrossRef]

- Poonam, P.; Ajay, K.; Akanksha, K.; Tamanna, V.; Vritti P. Recent Development of DNA Gyrase Inhibitors: An Update. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24(10), 1001-1030. [CrossRef]

- Ashley, R.E.; Dittmore, A.; McPherson, S.A.; Turnbough, C.L., Jr; Neuman, K.C.; Osheroff, N. Activities of gyrase and topoisomerase IV on positively supercoiled DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45(16), 9611-9624. [CrossRef]

- Hiasa H. (2018). DNA Topoisomerases as Targets for Antibacterial Agents. Methods Mol Biol, 1703: 47-62. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R. R.; Thapaliya, D.; Lemonovich, T. L.; Bonomo R. A. Gepotidacin: a novel, oral, «first-in-class’ triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections and urogenital gonorrhoea. J. Antimicrob Chemother, 2023, 78(5), 1137-1142. [CrossRef]

- Terreni, M.; Taccani, M.; Pregnolato, M. New Antibiotics for Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Strains: Latest Research Developments and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2671. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Badshah, S.L.; Muska, M.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, K. The Current Case of Quinolones: Synthetic Approaches and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 268. [CrossRef]

- Millanao, A.R.; Mora, A.Y.; Villagra, N.A.; Bucarey, S.A.; Hidalgo, A.A. Biological Effects of Quinolones: A Family of Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Agents. Molecules 2021, 20, 26, 7153. [CrossRef]

- Fesatidou, M.; Anthi, P.; Geronikaki, A. Heterocycle Compounds with Antimicrobial Activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26(8), 867-904. [CrossRef]

- Murugaiyan, J.; Kumar, P.A.; Rao, G.S.; Iskandar, K.; Hawser, S.; Hays, J.P.; Mohsen, Y.; Adukkadukkam, S.; Awuah, W.A.; Jose, R.A.M.; et al. Progress in Alternative Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance: Focus on Antibiotics. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 200. [CrossRef]

- Boparai, J.K.; Sharma, P.K. Mini Review on Antimicrobial Peptides, Sources, Mechanism and Recent Applications. Protein Pept Lett. 2020, 27(1), 4-16. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri Sovari, S.; Zobi F. Recent Studies on the Antimicrobial Activity of Transition Metal Complexes of Groups 6–12. Chemistry 2020, 2, 418-452. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Tengfei, W.; Jiaqi, X.; Gang, H. Antibacterial activity study of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, S022352341930358-. [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, M.; Świątek, P. 1,2,4-Triazoles as Important Antibacterial Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2021. 14(3), 224. [CrossRef]

- Kazeminejad, Z.; Marzi, M.; Shiroudi, A.; Kouhpayeh, S.A.; Farjam, M.; Zarenezhad, E. Novel 1, 2, 4-Triazoles as Antifungal Agents. Biomed Res Int. 2022, 22, 4584846. [CrossRef]

- Xuemei, G.; Zhi, X. 1,2,4-Triazole hybrids with potential antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Arch. Pharm. 2020, e2000223. [CrossRef]

- Jie, L.; Junwei, Z. The Antibacterial Activity of 1,2,3-triazole- and 1,2,4-Triazole-containing Hybrids against Staphylococcus aureus: An Updated Review (2020- Present). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22(1), 41-63. [CrossRef]

- Sergeieva, T.; Bilichenko, M.; Kholodnyak, S.; Monaykina, Yu.; Okovytyy, S.; Kovalenko, S.; Voronkov, E.; Leszczynski, J. (). Origin of Substituent Effect on Tautomeric Behavior of 1,2,4-Triazole Derivatives. Combined Spectroscopic and Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 10116−10122. [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, O.O.; Okovytyy, S.I.; Sviatenko, L.K.; Voronkov, E.O.; Shabelnyk, K.Р.; Kovalenko S.I. Tautomeric behavior of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives: combined spectroscopic and theoretical study. Struct Chem. 2023, 34, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Francis, J. E.; Cash, W. D.; Psychoyos, S.; Ghai, G.; Wenk, P.; Friedmann, R. C.; Atkins, C.; Warren, V.; Furness, P.; Hyun, J. L.; Stone, G. A.; Desai, M.; Williams, M. Structure-activity profile of a series of novel triazoloquinazoline adenosine antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, 1014-1020. [CrossRef]

- Balo, C.; López, C.; Brea, J. M.; Fernánde, F.; Caamaño, O. Synthesis and Evaluation of Adenosine Antagonist Activity of a Series of [1,2,4]Triazolo [1,5-c]quinazolines. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55(3), 372–375. [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.; Sreenivasa, S.; Govindaiah, S.; Chandramohan, V.; Shetty, P. R. Synthesis, biological screening, in silico study and fingerprint applications of novel 1,2,4-triazole derivatives. J Het. Chem. 2020, 57, 2010– 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kholodnyak, S.V.; Schabelnyk, K.P.; Zhernova, G.О.; Sergeieva, T.Yu.; Ivchuk, V.V.; Voskoboynik, O.Yu.; Kovalenko, S.І.; Trzhetsinskii, S.D.; Okovytyy, S.I.; Shishkina, S.V. (). Hydrolytic cleavage of pyrimidine ring in 2-aryl-[1,2,4]triazolo [1,5-c]-quinazolines: physico-chemical properties and hypoglycemia activity of the synthesized compounds. News of pharmacy 2015, 3(83), 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, O. O.; Sviatenko, L. K.; Shabelnyk, K. P.; Kovalenko, S. I.; Okovytyy, S. I. Synthesis and hydrolytic decomposition of 2-hetaryl [1,2,4]triazolo [1,5-c]quinazolines: DFT Study. Struct Chem. 2024, 35, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, S. I.; Antypenko, L. M.; Bilyi, A. K.; Kholodnyak, S. V.; Karpenko, O. V.; Antypenko, O. M.; Mykhaylova, N. S.; Los, T. I.,; Kolomoets, O. S. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of 2-(Alkyl-, Alkaryl-, Aryl-, Hetaryl-)-[1,2,4]triazolo [1,5-c]quinazolines. Sci. Pharm. 2013, 81(2), 359-391. [CrossRef]

- Breitmaier E. Structure elucidation by NMR in organic chemistry: a practical guide, third edition, Wiley 2002, 270р. ISBN: 978-0-470-85007-7.

- Zefirov, Y.V. Reduced intermolecular contacts and specific interactions in molecular crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 1997, 42, 865–886. https://inis.iaea.org/search/searchsinglerecord.aspx?recordsFor=SingleRecord&RN=30003683.

- Tao, L., Zhang, P., Qin, C., Chen, S.Y., Zhang, C., Chen, Z., Zhu, F., Yang, S.Y., Wei, Y.Q., Chen, Y.Z. Recent progresses in the exploration of machine learning methods as in-silico ADME prediction tools Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 86, 83-100. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B.W., Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [CrossRef]

- Muegge, I.; Heald, S.L.; Brittelli, D. Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1841–1846. [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Combin. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68. [CrossRef]

- Egan, W.J.; Merz, K.M.; Baldwin, J.J. Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3867–3877. [CrossRef]

- Martin, Y.C. A bioavailability score. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3164–3170. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, X. 6,7-Dimorpholinoalkoxy quinazoline derivatives as potent EGFR inhibitors with enhanced antiproliferative activities against tumor cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2018, 147, 77-89. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. () A Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112-122. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.S.S.; Kumar, S.R.; Kumar, N.N.; Ajith, S. Molecular docking studies of gyrase inhibitors: weighing earlier screening bedrock. In Silico Pharmacol. 2021, 9, 2. [CrossRef]

- MarvinSketch version 20.21.0, ChemAxon http://www.chemaxon.com.

- Trott, O.; Olson ,A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010, 31(2), 455–61. [CrossRef]

- Discovery Studio Visualizer v21.1.0.20298. Accelrys Software Inc., https://www.3dsbiovia.com.

- Baber, J. C.; Thompson, D.C.; Cross J. B.; Humblet C. GARD: A Generally Applicable Replacement for RMSD. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49(8), 1889–1900. [CrossRef]

- Warren, G. L.; Andrews, C. W.; Capelli, A.; Clarke, B.; LaLonde, J. M.; Lambert, M. H.; Head, M. S. et al. (). A critical assessment of docking programs and scoring functions. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 49(20), 5912-5931. [CrossRef]

- DockRMSD. Docking Pose Distance Calculation. 2022. https://seq.2fun.dcmb.med.umich.edu//DockRMSD.

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2020. ISBN 978-1-68440-066-9 [Print]; ISBN 978-1-68440-067-6 [Electronic]).

- SwissADME. http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php#. (Accessed 27 October 2024) accessed.

- Bilyi AK, Antypenko LM, Ivchuk VV, Kamyshnyi OM, Polishchuk NM, Kovalenko SI. 2-Heteroaryl-[1,2,4]triazolo [1,5-c]quinazoline-5(6 H)-thiones and Their S-Substituted Derivatives: Synthesis, Spectroscopic Data, and Biological Activity. ChemPlusChem. 2015;80(6):980-9.

- Nosulenko IS, Voskoboynik OY, Berest GG, Safronyuk SL, Kovalenko SI, Kamyshnyi OM, et al. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of 6-Thioxo-6,7-dihydro-2H-[1,2,4]triazino [2,3-c]-quinazolin-2-one Derivatives. Scientia pharmaceutica. 2014;82(3):483-500.

| Compounds | Affinity (kcal/mol) | Compounds | Affinity (kcal/mol) | Compounds | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA1 | -6.3 | 2.17 | -5.5 | 2.34 | -8.1 |

| 2.1 | -6.7 | 2.18 | -5.6 | 2.35 | -7.9 |

| 2.2 | -7.4 | 2.19 | -6.1 | 2.36 | -8.3 |

| 2.3 | -8.4 | 2.20 | -6.3 | 2.37 | -8.3 |

| 2.4 | -7.1 | 2.21 | -6.0 | 2.38 | -8.9 |

| 2.5 | -7.1 | 2.22 | -7.9 | 2.39 | -8.5 |

| 2.6 | -7.6 | 2.23 | -8.3 | 2.40 | -7.9 |

| 2.7 | -7.4 | 2.24 | -8.4 | 2.41 | -9.2 |

| 2.8 | -7.6 | 2.25 | -8.0 | 2.42 | -8.1 |

| 2.9 | -7.5 | 2.26 | -8.5 | 2.43 | -8.6 |

| 2.10 | -8.6 | 2.27 | -8.2 | 2.44 | -8.9 |

| 2.11 | -8.4 | 2.28 | -8.6 | 2.45 | -8.5 |

| 2.12 | -7.8 | 2.29 | -8.9 | 2.46 | -8.0 |

| 2.13 | -8.1 | 2.30 | -8.6 | 2.47 | -7.8 |

| 2.14 | -8.3 | 2.31 | -8.7 | 2.48 | -8.7 |

| 2.15 | -7.8 | 2.32 | -7.5 | Ciprofloxacin | -6.7 |

| 2.16 | -8.1 | 2.33 | -7.8 | - | - |

| Compounds | R | R1 | MIC, μM | MBC, μM | MBC/MIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | cyclopropyl | H | 62.4 | 124.8 | 2 |

| 2.2 | cyclopropyl | 6-Me | 933.4 | 933.4 | 1 |

| 2.3 | cyclopropyl | 5-F | 458.2 | 916.5 | 2 |

| 2.4 | cyclopropyl | 4-Cl | 852.2 | 852.2 | 1 |

| 2.5 | cyclobutyl | H | 14.6 | 23.3 | 1.5 |

| 2.6 | cyclobutyl | 6-Me | 876.1 | 876.1 | 1 |

| 2.7 | cyclobutyl | 5-F | 430.6 | 861.2 | 2 |

| 2.8 | cyclobutyl | 4-Cl | 402.1 | 804.2 | 2 |

| 2.9 | cyclopentyl | H | 27.4 | 438.0 | 16 |

| 2.10 | cyclopentyl | 6-Me | 825.4 | 825.4 | 1 |

| 2.11 | cyclopentyl | 5-F | 203.0 | 406.0 | 2 |

| 2.12 | cyclopentyl | 4-Cl | 47.6 | 47.6 | 1 |

| 2.13 | cyclohexyl | H | 26.8 | 206.3 | 7.7 |

| 2.14 | cyclohexyl | 6-Me | 390.1 | 390.1 | 1 |

| 2.15 | cyclohexyl | 5-F | 192.1 | 768.3 | 4 |

| 2.16 | cyclohexyl | 4-Cl | 361.3 | 723.6 | 2 |

| 2.17 | adamantyl-1 | H | 10.6 | 21.2 | 2 |

| 2.18 | adamantyl-1 | 6-Me | 10.1 | 20.2 | 2 |

| 2.19 | adamantyl-1 | 5-F | 320.1 | 640.2 | 2 |

| 2.20 | adamantyl-1 | 4-Cl | 304.1 | 608.2 | 2 |

| 2.21 | adamantyl-1 | 4-Br | 267.9 | 535.7 | 2 |

| 2.22 | Ph | H | 26.4 | 211.6 | 8 |

| 2.23 | 4-FC6H4 | H | 196.6 | 786.6 | 4 |

| 2.24 | 4-ClC6H4 | H | 92.3 | 184.6 | 2 |

| 2.25 | 4-BrC6H4 | H | 317.3 | 634.6 | 2 |

| 2.26 | 2-FC6H4 | H | 12.4 | 24.8 | 2 |

| 2.27 | furan-2-yl | H | 221.0 | 442.0 | 2 |

| 2.28 | furan-3-yl | 6-Me | 13.0 | 52.0 | 4 |

| 2.29 | furan-3-yl | 5-F | 25.6 | 51.2 | 2 |

| 2.30 | furan-3-yl | 4-Cl | 11.9 | 23.8 | 2 |

| 2.31 | furan-3-yl | 4-Br | 5.2 | 10.4 | 2 |

| 2.32 | thiophen-2-yl | H | 103.2 | 206.4 | 2 |

| 2.33 | thiophen-2-yl | 5-F | 24.0 | 48.0 | 2 |

| 2.34 | thiophen-3-yl | 6-Me | 12.2 | 12.2 | 1 |

| 2.35 | thiophen-3-yl | 5-F | 6.1 | 48.0 | 8 |

| 2.36 | thiophen-3-yl | 4-Cl | 45.2 | 180.8 | 4 |

| 2.37 | thiophen-3-yl | 4-Br | 77.8 | 311.3 | 4 |

| 2.38 | benzofuran-2-yl | H | 180.9 | 361.8 | 2 |

| 2.39 | benzofuran-2-yl | 6-Me | 10.7 | 21.4 | 2 |

| 2.40 | benzofuran-2-yl | 5-F | 42.5 | 84.9 | 2 |

| 2.41 | benzofuran-2-yl | 4-Cl | 20.1 | 40.2 | 2 |

| 2.42 | benzofuran-2-yl | 4-Br | 140.7 | 140.7 | 1 |

| 2.43 | benzothiophen-2-yl | H | 171.0 | 342.0 | 2 |

| 2.44 | indol-2-yl | H | 181.6 | 363.2 | 2 |

| 2.45 | pyridin-2-yl | H | 105.3 | 210.6 | 2 |

| 2.46 | pyridin-3-yl | H | 13.2 | 52.8 | 4 |

| 2.47 | pyridin-4-yl | H | 105.3 | 210.6 | 2 |

| 2.48 | pyridin-4-yl | Br | 79.1 | 158.2 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4.7 | 9.6 | 2 |

| Physicochemical descriptors & predicted pharmacokinetic properties* | Compounds | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.17 | 2.18 | 2.26 | 2.28 | 2.30 | 2.31 | 2.34 | 2.35 | 2.39 | 2.46 | CF** | |

| MW (Da) (< 500) | 294.39 | 308.42 | 252.27 | 240.26 | 260.68 | 305.13 | 256.33 | 260.29 | 290.32 | 237.26 | 331.34 |

| n-ROTB (< 10) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| n-HBA (< 10) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| n-HBD (≤ 5) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| TPSA (< 140, Ų) | 67.59 | 67.59 | 87.82 | 80.73 | 80.73 | 80.73 | 95.83 | 95.83 | 80.73 | 80.48 | 74.57 |

| logP (≤ 5) | 3.21 | 3.54 | 2.05 | 2.06 | 2.30 | 2.34 | 2.74 | 2.69 | 3.07 | 1.66 | 1.10 |

| Molar refractivity | 88.11 | 93.08 | 73.68 | 68.89 | 68.94 | 71.63 | 74.50 | 69.49 | 86.40 | 69.45 | 95.25 |

| Gastrointestinal absorption | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| Blood–brain barrier permeation | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Druglikeness | |||||||||||

| Lipinski (Pfizer) filter [42] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Veber (GSK) filter [43] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Muegge (Bayer) filter [44] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Ghose filter [45] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Egan filter [46] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Bioavailability Score [47] | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Lead-likeness | no | no | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).