Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

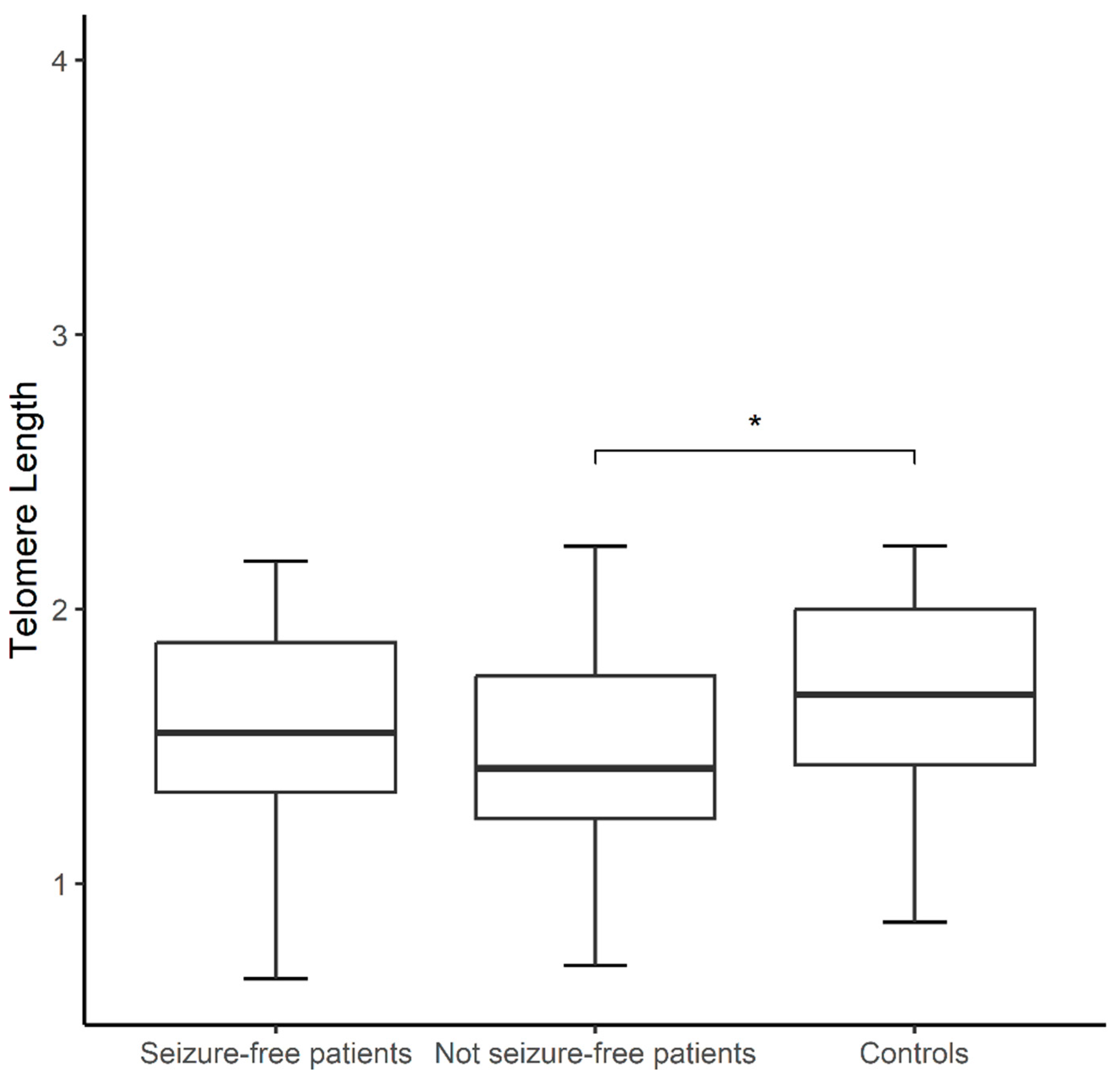

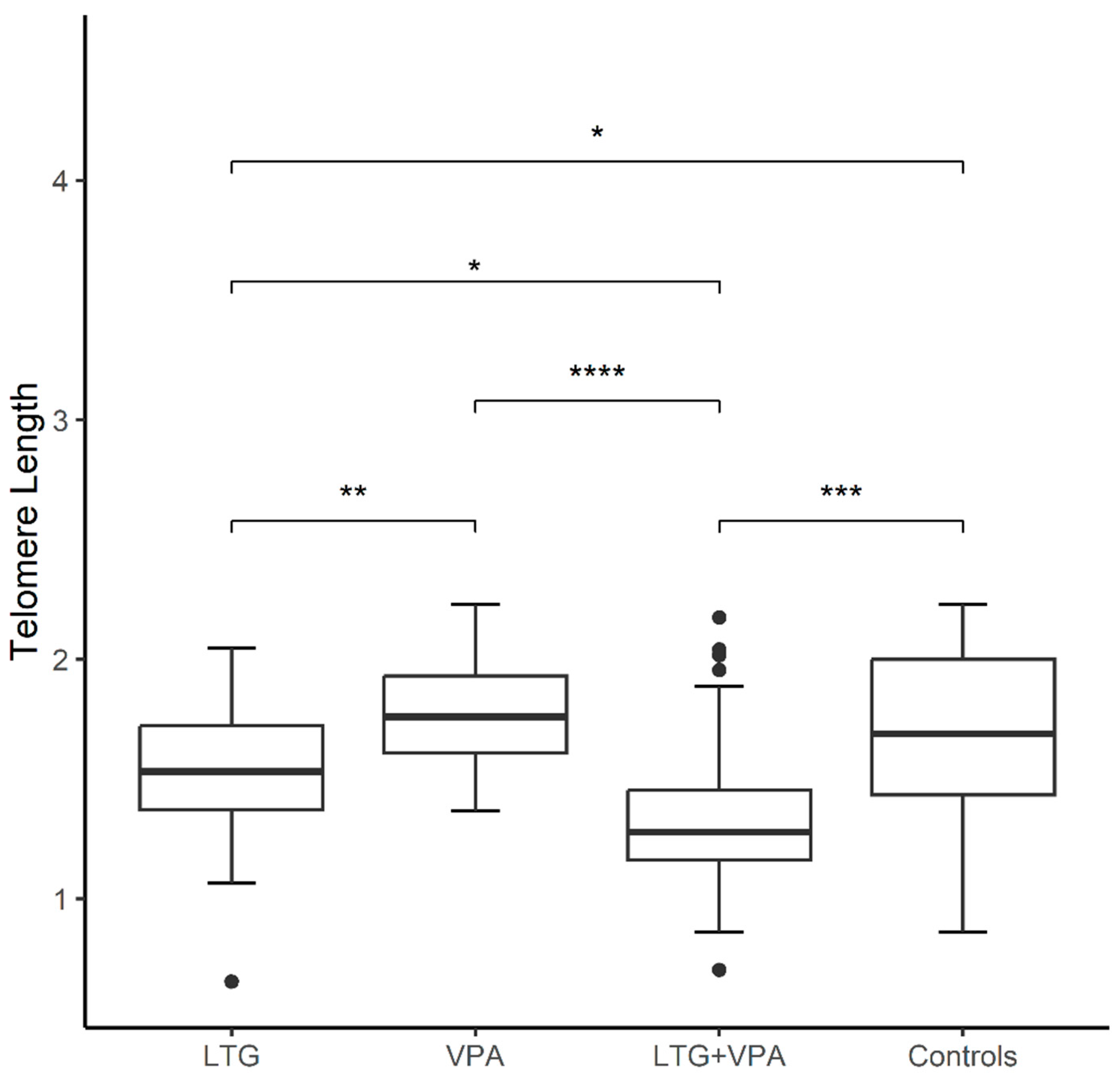

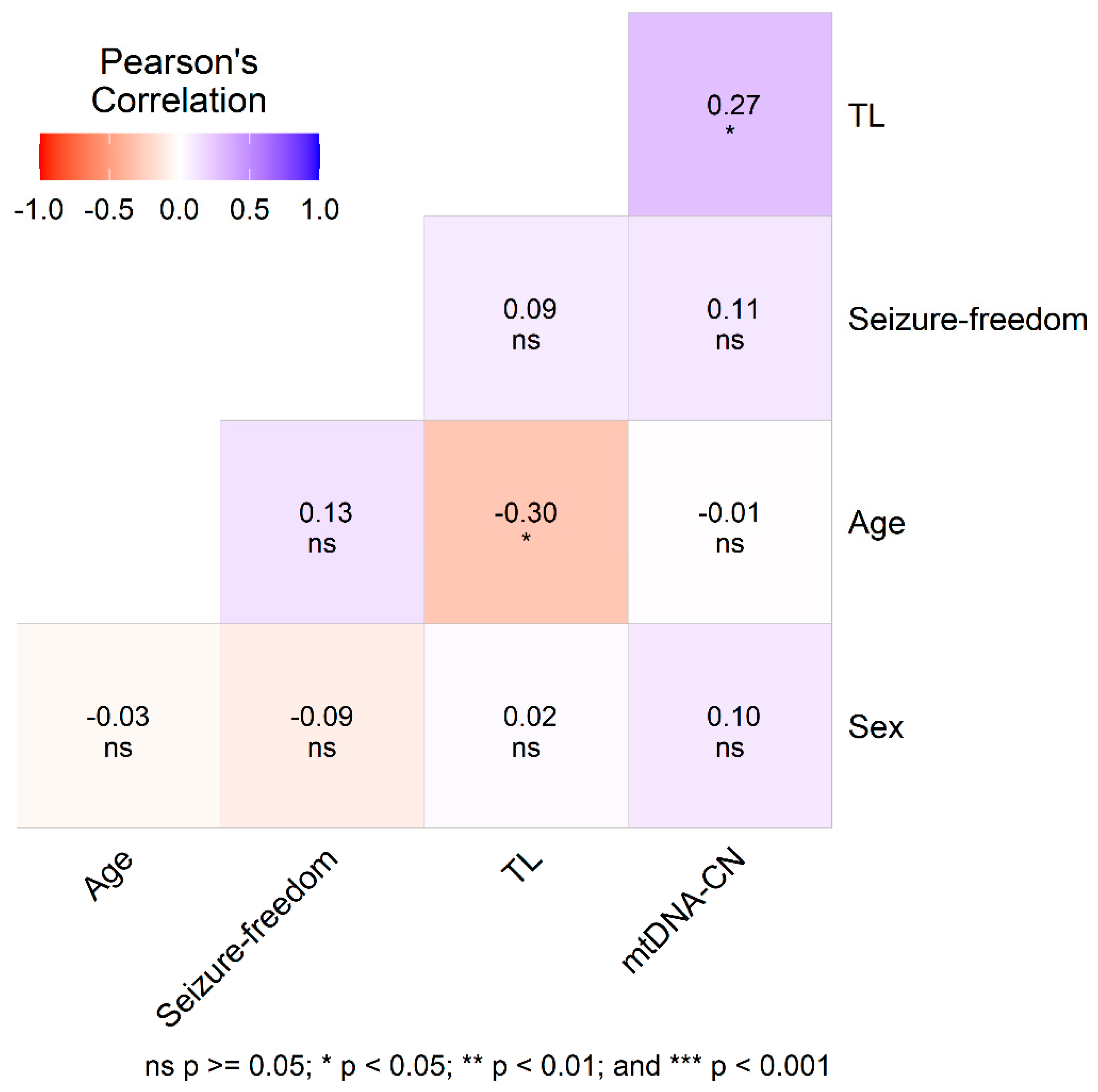

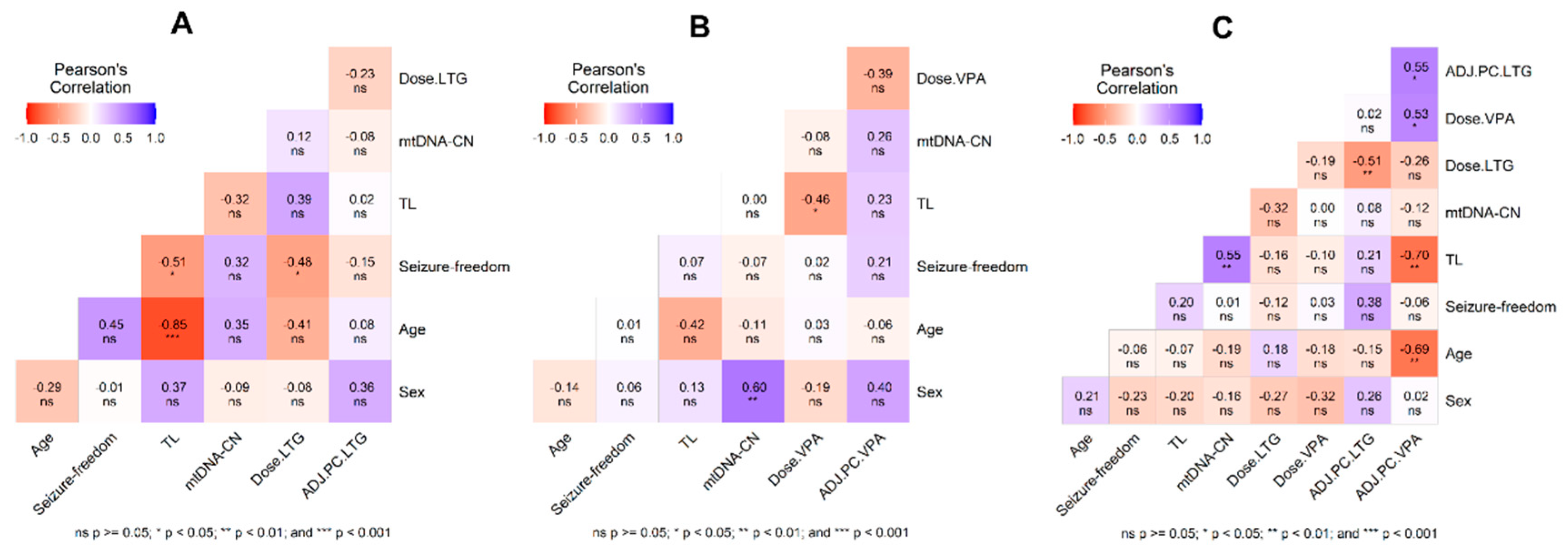

Background/Objectives: Antiseizure drugs (ASDs) are the primary therapy for epilepsy and the choice varies according to the seizure type. Epilepsy patients experience chronic mitochondrial oxidative stress and increased levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, recognizable hallmarks of biological aging, however few studies have explored aging markers in epilepsy. Herein, we addressed for the first time the impact of ASDs on molecular aging by measuring telomere length (TL) and mtDNA copy number (mtDNA-CN). Methods: Using QPCR, in epilepsy patients compared to matched healthy controls (CT), and its association with plasma levels of ASDs and other clinical variables. The sample comprised 64 epilepsy patients and 64 CT. Patients were grouped on monotherapy with lamotrigine (LTG) or valproic acid (VPA), and those treated with a combination therapy (LTG+VPA). Multivariable logistic regression was applied to analyze obtained data. Results: mtDNA-CN was similar between patients and controls, and none of the comparisons were significant for this marker. TL was shorter in not seizure-free patients than CT (1.50±0.35 vs. 1.68±0.34, p<0.05), regardless of the ASD therapy. These patients exhibited the highest proportion of adverse drug reactions. TL was longer in patients on VPA monotherapy, followed by patients on LTG monotherapy and by patients on LTG+VPA combined scheme (1.77±0.24; 1.50±0.32; 1.36±0.37 respectively, p<0.05), suggesting that ASD treatment differentially modulates TL. Conclusions: Our findings suggest that clinicians could consider TL measurements to decide the best ASD treatment option (VPA and/or LTG) to help predict ASD response in epilepsy patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Clinical Data of Patients

2.3. Relative Quantification of Telomere Length and mtDNA Copy Number

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

| Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) |

Total patients (%) (n=64) |

Patients on LTG (%) (n=18) |

Patients on VPA (%) (n=19) |

Patients on LTG+VPA (%) (n=27) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | ||||

| Nervousness or distress | 38.9 | 25.0 | 5.9 | 69.2 |

| Fatigue or tiredness | 35.6 | 50.0 | 11.8 | 42.3 |

| Drowsiness | 35.6 | 18.8 | 41.2 | 42.3 |

| Weight gain | 39.0 | 31.3 | 47.1 | 38.5 |

| Insomnia | 32.2 | 43.8 | 11.8 | 38.5 |

| Alopecia | 25.4 | 18.8 | 11.8 | 38.5 |

| Feeling groggy | 22.0 | 12.5 | 5.9 | 38.5 |

| Thick or swollen gums | 20.7 | 31.3 | 11.8 | 20.0 |

| Hyperactivity | 13.6 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 23.1 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 10.2 | 12.5 | 5.9 | 11.5 |

| Weight loss | 8.6 | 12.5 | 5.9 | 8.0 |

| Hirsutism | 6.8 | 6.3 | 0 | 11.5 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Abdominal pain or gastritis | 33.9 | 18.8 | 11.8 | 57.7 |

| Constipation | 23.7 | 12.5 | 17.6 | 34.6 |

| Diarrhea | 13.6 | 6.3 | 17.6 | 15.4 |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 13.6 | 0 | 11.8 | 23.1 |

| Cutaneous | ||||

| Allergy (mild rash) | 5.1 | 0 | 5.9 | 7.7 |

| Allergy (moderate or severe rash or Steven Johnson) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Facial edema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurological | ||||

| Memory failure | 50.8 | 43.8 | 35.3 | 65.4 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 45.8 | 31.3 | 35.3 | 61.5 |

| Headache | 42.4 | 56.3 | 17.6 | 50.0 |

| Shaking (tremors) | 35.6 | 18.8 | 29.4 | 50.0 |

| Dizziness or vertigo | 27.1 | 12.5 | 17.7 | 42.3 |

| Trouble speaking | 25.4 | 25.0 | 17.6 | 30.8 |

| Slow thinking | 23.7 | 25.0 | 11.8 | 30.8 |

| Confusion | 18.6 | 18.8 | 29.4 | 11.5 |

| Double or blurred vision or nystagmus | 16.9 | 18.8 | 5.9 | 23.1 |

| Difficulty walking (ataxia) | 13.6 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 15.4 |

| Instability | 10.2 | 0 | 11.8 | 15.4 |

| Paresthesia | 8.5 | 6.3 | 0 | 15.4 |

| Parkinsonism | 8.5 | 6 | 11.8 | 7.7 |

| Diplopia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Choreoathetosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychiatric | ||||

| Aggression or irritability | 50.8 | 50 | 29.4 | 65.4 |

| Depression or sadness | 47.5 | 43.8 | 47.1 | 50.0 |

| Humor changes | 37.3 | 31.3 | 52.9 | 30.8 |

| Hallucinations, agitation, delirium | 13.6 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 23.1 |

| Manic episode | 6.8 | 0 | 5.9 | 11.5 |

| Suicidal ideation | 6.8 | 6.3 | 17.6 | 0 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organization WH. Epilepsy: a public health imperative: summary. 2019 [cited 2024 Nov 19]; Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/325440.

- Málaga I, Sánchez-Carpintero R, Roldán S, Ramos-Lizana J, García-Peñas JJ. [New anti-epileptic drugs in Paediatrics]. An Pediatr. 2019 Dec;91(6):415.e1-415.e10. [CrossRef]

- Hakami T. Neuropharmacology of Antiseizure Drugs. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2021 Sep;41(3):336–51. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Juárez IE, López-Zapata R, Gómez-Arias B, Bravo-Armenta E, Romero-Ocampo L, Estévez-Cruz Z, et al. [Refractory epilepsy: use of the new definition and related risk factors. A study in the Mexican population of a third-level centre]. Rev Neurol. 2012 Feb 1;54(3):159–66.

- Barrett JH, Iles MM, Dunning AM, Pooley KA. Telomere length and common disease: study design and analytical challenges. Hum Genet. 2015 Jul;134(7):679–89. [CrossRef]

- Eitan E, Hutchison ER, Mattson MP. Telomere shortening in neurological disorders: an abundance of unanswered questions. Trends Neurosci. 2014 May;37(5):256–63. [CrossRef]

- Ridout KK, Ridout SJ, Price LH, Sen S, Tyrka AR. Depression and telomere length: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016 Feb;191:237–47. [CrossRef]

- Apetroaei MM, Fragkiadaki P, Velescu B Ștefan, Baliou S, Renieri E, Dinu-Pirvu CE, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic Considerations on Telomere Biology: The Positive Effect of Pharmacologically Active Substances on Telomere Length. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jul 13;25(14):7694. [CrossRef]

- Martinsson L, Wei Y, Xu D, Melas PA, Mathé AA, Schalling M, et al. Long-term lithium treatment in bipolar disorder is associated with longer leukocyte telomeres. Transl Psychiatry. 2013 May 21;3(5):e261. [CrossRef]

- Powell TR, Dima D, Frangou S, Breen G. Telomere Length and Bipolar Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jan;43(2):445–53. [CrossRef]

- Squassina A, Pisanu C, Congiu D, Caria P, Frau D, Niola P, et al. Leukocyte telomere length positively correlates with duration of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 Jul;26(7):1241–7. [CrossRef]

- Courtes AC, Jha R, Topolski N, Soares JC, Barichello T, Fries GR. Exploring accelerated aging as a target of bipolar disorder treatment: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2024 Oct 23;180:291–300. [CrossRef]

- Hough CM, Bersani FS, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Reus VI, Lindqvist D, et al. Leukocyte telomere length predicts SSRI response in major depressive disorder: A preliminary report. Mol Neuropsychiatry. 2016 Jul;2(2):88–96. [CrossRef]

- Rasgon N, Lin KW, Lin J, Epel E, Blackburn E. Telomere length as a predictor of response to Pioglitazone in patients with unremitted depression: a preliminary study. Transl Psychiatry. 2016 Jan 5;6(1):e709. [CrossRef]

- Polho GB, Cardillo GM, Kerr DS, Chile T, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV, et al. Antipsychotics preserve telomere length in peripheral blood mononuclear cells after acute oxidative stress injury. Neural Regen Res. 2022 May;17(5):1156–60. [CrossRef]

- Bersani FS, Lindqvist D, Mellon SH, Penninx BWJH, Verhoeven JE, Révész D, et al. Telomerase activation as a possible mechanism of action for psychopharmacological interventions. Drug Discov Today. 2015 Nov;20(11):1305–9. [CrossRef]

- Elvsåshagen T, Vera E, Bøen E, Bratlie J, Andreassen OA, Josefsen D, et al. The load of short telomeres is increased and associated with lifetime number of depressive episodes in bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1–3):43–50. [CrossRef]

- Kim KC, Choi CS, Gonzales ELT, Mabunga DFN, Lee SH, Jeon SJ, et al. Valproic Acid Induces Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Expression during Cortical Development. Exp Neurobiol. 2017 Oct;26(5):252–65.

- Miranda DM, Rosa DV, Costa BS, Nicolau NF, Magno L a. V, de Paula JJ, et al. Telomere shortening in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2020 Oct;166:106427. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Liu X, Ding X, Wang F, Geng X. Telomere and its role in the aging pathways: telomere shortening, cell senescence and mitochondria dysfunction. Biogerontology. 2019 Feb;20(1):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Sahin E, Colla S, Liesa M, Moslehi J, Müller FL, Guo M, et al. Telomere dysfunction induces metabolic and mitochondrial compromise. Nature. 2011 Feb 17;470(7334):359–65. [CrossRef]

- Zole E, Ranka R. Mitochondria, its DNA and telomeres in ageing and human population. Biogerontology. 2018 Jul;19(3–4):189–208. [CrossRef]

- Zsurka G, Kunz WS. Mitochondrial dysfunction and seizures: the neuronal energy crisis. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Sep 1;14(9):956–66. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann RF, Wang Y, Yuan P, Zhou R, Li X, Alesci S, et al. Common effects of lithium and valproate on mitochondrial functions: Protection against methamphetamine-induced mitochondrial damage. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(6):805–22. [CrossRef]

- Scaini G, Rezin GT, Carvalho AF, Streck EL, Berk M, Quevedo J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: Evidence, pathophysiology and translational implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016 Sep 1;68:694–713. [CrossRef]

- Kageyama Y, Deguchi Y, Kasahara T, Tani M, Kuroda K, Inoue K, et al. Intra-individual state-dependent comparison of plasma mitochondrial DNA copy number and IL-6 levels in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2022 Feb 15;299:644–51. [CrossRef]

- Chang CC, Jou SH, Lin TT, Lai TJ, Liu CS. Mitochondria DNA Change and Oxidative Damage in Clinically Stable Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. PLoS ONE. 2015 May 6;10(5):e0125855. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Efstathopoulos P, Millischer V, Olsson E, Wei YB, Brüstle O, et al. Mitochondrial DNA copy number is associated with psychosis severity and anti-psychotic treatment. Sci Rep. 2018 Aug 24;8(1):12743. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M, Heaphy CM, Griffith JK, Parellada E, Esmatjes E, et al. Telomere length and pulse pressure in newly diagnosed, antipsychotic-naive patients with nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009 Mar;35(2):437–42. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar V, Rajasekaran A, Subbanna M, Kalmady SV, Venugopal D, Agrawal R, et al. Leukocyte mitochondrial DNA copy number in schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020 Oct;53:102193. [CrossRef]

- Lee EH, Han MH, Ha J, Park HH, Koh SH, Choi SH, et al. Relationship between telomere shortening and age in Korean individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease compared to that in healthy controls. Aging. 2020 Dec 15;13(2):2089–100. [CrossRef]

- Pyle A, Anugrha H, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Yarnall A, Burn D, Hudson G. Reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number is a biomarker of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2016 Feb;38:216.e7-216.e10. [CrossRef]

- Petersen MH, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Sørensen SA, Nielsen JE, Hjermind LE, Vinther-Jensen T, et al. Reduction in mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral leukocytes after onset of Huntington’s disease. Mitochondrion. 2014 Jul;17:14–21. [CrossRef]

- Breuer LEM, Boon P, Bergmans JWM, Mess WH, Besseling RMH, de Louw A, et al. Cognitive deterioration in adult epilepsy: Does accelerated cognitive ageing exist? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016 May;64:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014 Apr;55(4):475–82. [CrossRef]

- Najafi MR, Malekian M, Akbari M, Najafi MA. Magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography findings in a sample of Iranian patients with epilepsy. J Res Med Sci Off J Isfahan Univ Med Sci. 2018;23:106. [CrossRef]

- Westover MB, Cormier J, Bianchi MT, Shafi M, Kilbride R, Cole AJ, et al. Revising the “Rule of Three” for inferring seizure freedom. Epilepsia. 2012 Feb;53(2):368–76. [CrossRef]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002 May 15;30(10):e47. [CrossRef]

- Refinetti P, Warren D, Morgenthaler S, Ekstrøm PO. Quantifying mitochondrial DNA copy number using robust regression to interpret real time PCR results. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Nov 13;10(1):593. [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R [Internet]. Boston, MA: RStudio, PBC.; 2024. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Olivoto T, Lúcio AD. metan: An R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Jarman S, editor. Methods Ecol Evol. 2020 Jun;11(6):783–9. [CrossRef]

- Rahman M, Awosika AO, Nguyen H. Valproic Acid. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 19]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559112/.

- Douglas-Hall P, Dzahini O, Gaughran F, Bile A, Taylor D. Variation in dose and plasma level of lamotrigine in patients discharged from a mental health trust. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2017 Jan 1;7(1):17–24. [CrossRef]

- Dreier JW, Laursen TM, Tomson T, Plana-Ripoll O, Christensen J. Cause-specific mortality and life years lost in people with epilepsy: a Danish cohort study. Brain. 2023 Jan 4;146(1):124–34. [CrossRef]

- Avanesian A, Khodayari B, Felgner JS, Jafari M. Lamotrigine extends lifespan but compromises health span in Drosophila melanogaster. Biogerontology. 2010 Feb;11(1):45–52. [CrossRef]

- Evason K, Collins JJ, Huang C, Hughes S, Kornfeld K. Valproic acid extends Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. Aging Cell. 2008 Jun;7(3):305–17. [CrossRef]

- Okazaki S, Numata S, Otsuka I, Horai T, Kinoshita M, Sora I, et al. Decelerated epigenetic aging associated with mood stabilizers in the blood of patients with bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2020 May 4;10(1):129. [CrossRef]

- Luo X, Ruan Z, Liu L. Causal relationship between telomere length and epilepsy: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Epilepsia Open. 2023 Dec;8(4):1432–9. [CrossRef]

- Shao L, Young LT, Wang JF. Chronic treatment with mood stabilizers lithium and valproate prevents excitotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress in rat cerebral cortical cells. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Dec 1;58(11):879–84. [CrossRef]

- Eren I, Naziroğlu M, Demirdaş A. Protective effects of lamotrigine, aripiprazole and escitalopram on depression-induced oxidative stress in rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2007 Jul;32(7):1188–95. [CrossRef]

- Park WJ, Lee JH. Positive correlation between telomere length and mitochondrial copy number in breast cancers. Ann Transl Med. 2019 Apr;7(8):183. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Vázquez A, Sánchez-Badajos S, Ramírez-García MÁ, Alvarez-Luquín D, López-López M, Adalid-Peralta LV, et al. Longitudinal Changes in Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Telomere Length in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Genes. 2023 Oct 7;14(10):1913. [CrossRef]

- Russo R, Kemp M, Bhatti UF, Pai M, Wakam G, Biesterveld B, et al. Life on the battlefield: Valproic acid for combat applications. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020 Aug;89(2S Suppl 2):S69–76. [CrossRef]

- Romoli M, Mazzocchetti P, D’Alonzo R, Siliquini S, Rinaldi VE, Verrotti A, et al. Valproic Acid and Epilepsy: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Evidences. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2019;17(10):926–46. [CrossRef]

- Salamati A, Majidinia M, Asemi Z, Sadeghpour A, Oskoii MA, Shanebandi D, et al. Modulation of telomerase expression and function by miRNAs: Anti-cancer potential. Life Sci. 2020 Oct 15;259:118387. [CrossRef]

- Chang CC, Chen PS, Lin JR, Chen YA, Liu CS, Lin TT, et al. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number Is Associated With Treatment Response and Cognitive Function in Euthymic Bipolar Patients Receiving Valproate. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022 Aug 4;25(7):525–33. [CrossRef]

- Pipek LZ, Pipek HZ, Castro LHM. Seizure control in mono- and combination therapy in a cohort of patients with Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy. Sci Rep. 2022 Jul 19;12(1):12350. [CrossRef]

- Costa B, Vale N. Understanding Lamotrigine’s Role in the CNS and Possible Future Evolution. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 23;24(7):6050. [CrossRef]

- Deepa D, Jayakumari N, Thomas SV. Oxidative stress is increased in women with epilepsy: Is it a potential mechanism of anti-epileptic drug-induced teratogenesis? Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012 Oct;15(4):281–6. [CrossRef]

- Jang EH, Lee JH, Kim SA. Acute Valproate Exposure Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Autophagy with FOXO3a Modulation in SH-SY5Y Cells. Cells. 2021 Sep 23;10(10):2522. [CrossRef]

- Sitarz KS, Elliott HR, Karaman BS, Relton C, Chinnery PF, Horvath R. Valproic acid triggers increased mitochondrial biogenesis in POLG-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Genet Metab. 2014 May;112(1):57–63. [CrossRef]

- Finsterer J. Toxicity of Antiepileptic Drugs to Mitochondria. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;240:473–88. [CrossRef]

- Kong FC, Ma CL, Zhong MK. Epigenetic Effects Mediated by Antiepileptic Drugs and their Potential Application. http://www.eurekaselect.com [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 3]; Available from: https://www.eurekaselect.com/article/101309. [CrossRef]

- Stettner M, Krämer G, Strauss A, Kvitkina T, Ohle S, Kieseier BC, et al. Long-term antiepileptic treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors may reduce the risk of prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev Off J Eur Cancer Prev Organ ECP. 2012 Jan;21(1):55–64. [CrossRef]

- Ni G, Qin J, Li H, Chen Z, Zhou Y, Fang Z, et al. Effects of antiepileptic drug monotherapy on one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation in patients with epilepsy. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0125656. [CrossRef]

- Yang N, Guan QW, Chen FH, Xia QX, Yin XX, Zhou HH, et al. Antioxidants Targeting Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress: Promising Neuroprotectants for Epilepsy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:6687185. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, et al. Association of Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Telomere Length with Prevalent and Incident Cancer and Cancer Mortality in Women: A Prospective Swedish Population-Based Study, Cancers, vol. 13, no. 15, Art. no. 15, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Garcia C, Zeleke H, Rojas A. Impact of Stress on Epilepsy: Focus on Neuroinflammation—A Mini Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jan;22(8):4061. [CrossRef]

- Carver AJ, Hing B, Elser BA, Lussier SJ, Yamanashi T, Howard MA, et al. Correlation of telomere length in brain tissue with peripheral tissues in living human subjects. Front Mol Neurosci [Internet]. 2024 Mar 7 [cited 2024 Dec 3];17. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/molecular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2024.1303974/full. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n= 64) | Controls (n = 64) | |||||

| Total (n= 64) | Male (n= 31) | Female (n= 33) | Total (n= 64) | Male (n= 31) | Female (n= 33) | |

| Sex (%) | 100 | 48 | 52 | 100 | 48 | 52 |

| Age in years mean ± SD (range) | 32.0 ± 13.10 (18-73) | 32.48 ± 14.20 (18-72) | 31.6 ± 12.3 (18-73) | 32.0 ± 13.0 (18-73) | 32.5 ± 14.30 (73-18) | 31.4 ± 11.9 (19-72) |

| Not seizure-free patients* | 42 | 19 | 23 | NA | NA | NA |

| Seizure-free patients* | 22 | 12 | 10 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG monotherapy group | Patients (n= 18) | Controls (n = 18) | ||||

| Total (n= 18) | Male (n= 7) | Female (n= 11) | Total (n=18) | Male (n=7) | Female (n=11) | |

| Sex (%) | 100 | 39 | 61 | 100 | 39 | 61 |

| Age in years, mean ± SD (range) | 34.2 ± 14.9 (18-72) | 39.6 ± 27.7 (18-72) | 30.8 ± 9.39 (19-49) | 34.3 ± 15.3 (18-73) | 40.0 ± 21.4 (18-73) | 30.6 ± 9.17 (19-47) |

| Not seizure-free patients* | 13 | 5 | 8 | NA | NA | NA |

| Seizure-free patients* | 5 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG dose in mg; mean ± SD | 225.0 ± 113.0 | 236.0 ± 103.0 | 218.0 ± 123.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG PC, n = (Subtherapeutic / therapeutic /supratherapeutic) | (7 / 11 / 0) | (3 / 8 / 0) | (4 / 3 / 0) | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG PC μg mL−1; mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 3.6 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 5.74 ± 4.1 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG adjusted PC (µg mL-1 dose Kg-1) | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA monotherapy group | Patients (n= 19) | Controls (n = 18) | ||||

| Total (n= 19) | Male (n=9) | Female (n= 10) | Total (n= 19) | Male (n= 9) | Female (n= 10) | |

| Sex (%) | 100 | 57 | 43 | 100 | 57 | 43 |

| Age in years, mean ± SD (range) | 32.8 ± 12.3 (20-67) | 34.4 ± 14.8 (21-67) | 31.0 ± 9.42 (20-49) | 32.7 ± 12.0 (21-66) | 34.2 ± 14.5 (21-66) | 31.0 ± 9.19 (21-49) |

| Not seizure-free patients* (n= 9) | 9 | 4 | 5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Seizure-free patients* (n = 10) | 10 | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA dose in mg; mean ± SD⤉ | 932.0 ± 437.0 | 1100.0 ± 477.0 | 844.0 ± 397.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA PC, n = (Subtherapeutic / therapeutic / supratherapeutic) ⤉ | (0 / 17 / 0) | (0 / 9 / 0) | (0 / 8 / 0) | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA PC, μg mL−1; mean ± SD ⤉ | 68.1 ± 20.6 | 60.3 ± 16.7 | 76.9 ± 22.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA adjusted PC (µg mL-1 dose Kg-1) ⤉ | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG+VPA combined therapy group | Patients (n= 27) | Controls (n= 27) | ||||

| Total (n= 27) | Male (n= 14) | Female (n=13) | Total (n= 27) | Male (n=14) | Female (n= 13) | |

| Sex (%) | 100 | 52 | 48 | 100 | 52 | 48 |

| Age in years, mean ± SD (range) | 30.1 ± 12.6 (18-73) | 27.6 ± 7.64 (19-48) | 32.8 ± 16.4 (18-73) | 29.9 ± 12.3 (18-72) | 27.6 ± 7.44 (18-47) | 32.4 ± 15.9 (19-72) |

| Not seizure-free patients* | 20 | 9 | 11 | NA | NA | NA |

| Seizure-free patients* | 7 | 5 | 2 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG dose in mg; mean ± SD | 189.0 ± 84.7 | 211.0 ± 92.4 | 165.0 ± 71.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG PC, n = (Subtherapeutic / therapeutic / supratherapeutic) | (1 / 21 / 5) | (1 / 10 / 3) | (0 / 11 / 2) | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG PC, μg mL−1; mean ± SD | 9.8 ± 4.3 | 9.8 ± 4.6 | 9.7 ± 4.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| LTG adjusted PC (µg mL-1 dose Kg-1) | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 2.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA dose in mg; mean ± SD | 1039.0 ± 496.0 | 1189.0 ± 476.0 | 950 ± 122.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA PC, n = (Subtherapeutic / therapeutic / supratherapeutic) § | (0 / 15 / 1) | (0 / 6 / 0) | (0 / 9 / 1) | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA PC, μg mL−1; mean ± SD § | 74.8 ± 25.5 | 76.8 ± 15.9 | 80.0 ± 33.9 | NA | NA | NA |

| VPA adjusted PC (µg mL-1 dose Kg-1) § | 2.7 ± 1.6 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | NA | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).