1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the leading cancers that most frequently affect women worldwide, with 604,000 new cases occurring annually and more than 300,000 deaths due to this disease [

1]. In recent years, the increased occurrence and mortality of this type of cancer have been observed in young women, even those under 40 years of age. In Latin America, 83,200 women are diagnosed, and 35,680 die each year, with a high proportion (52%) of patients under 60 years of age [

2].

To combat advanced local cervical cancer, a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is used to increase the survival rate of patients and try to ensure that the tumor does not recur due to the existence of residual cancer cells [

3,

4]. However, chemotherapeutic agents lack selectivity, causing cytotoxic effects on both cancer cells and normal cells, which causes severe adverse effects that may be transient or persist for long periods, such as thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, anemia due to hematological toxicity and bone marrow depression, which decreases the quality of life of patients [

5]. This obstacle in treatment can be overcome by targeted or localized therapy, which limits the toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents by promoting their action at the tumor site, avoiding systemic action. This type of therapy offers advantages such as protection from drug degradation in the bloodstream, improved drug stability and bioavailability, selective administration, and decreased toxic side effects.

Easy access to the cervix through the vagina provides a convenient and suitable route for local administration of drugs such as chemotherapeutic agents. Nowadays, different devices are used for vaginal administration of drugs, such as suppositories for the treatment of bacterial infections, gels and films, among others; however, these drug delivery vehicles have disadvantages such as low intravaginal adherence and short residence time or low loading capacity of the drug in the pharmaceutical form [

6,

7,

8].

Drug delivery systems made of natural or synthetic biomaterials, such as drug-loaded electrospun polymeric fibers, are being used at micro and nanometric scales. These systems have great advantages, such as high loading capacity due to the large surface area in relation to the volume of the fibers, prolonged and controlled drug release, flexibility, biodegradability and biocompatibility since the polymers that make up the fibers are compatible with the human body [

9].

Coaxial electrospinning has been used to fabricate micro/nanofibers with shell/core structures of different polymers in a single step, thereby achieving improved combined properties in a single fiber [

10,

11]. Electrospinning is a process by which fibers are obtained by stretching viscoelastic polymer solutions to which a specific voltage is applied so that fine jets of solution are expelled from the needle to the collector, depositing the formed fibers in the latter [

12].

Polycaprolactone (PCL) is an FDA-approved polymer of great importance for its mechanical properties, miscibility with a wide range of other polymers, thermal and chemical stability, permeability, biodegradability, biocompatibility. It has good mechanical rigidity at the physiological level [

10,

13]. Despite having applications in drug delivery systems, its use is limited by its hydrophobic nature, low encapsulation and unwanted burst release of the drug. However, this difficulty can be solved by using it in drug delivery systems in combination with other hydrophilic polymers such as polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). This synthetic polymer has applications as a drug carrier due to its hydrophilic nature, physiological compatibility, non-toxicity, temperature resistance and pH stability [

14,

15,

16].

The current study developed a polycaprolactone/polyvinylpyrrolidone sheath/core coaxial fiber biofilm loaded with the chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin by coaxial electrospinning technique. The two polymers used were chosen for their biodegradability and compatibility with the human body; PCL, used for the sheath of the fibers, provides good mechanical properties, while PVP was used for the inner part of the fiber due to its hydrophilic nature that favors the wettability of the biofilm and its dissolution in the aqueous vaginal environment and release of cisplatin. Furthermore, PVP has adhesive properties that improve the intravaginal residence time of the biofilm. The chemotherapeutic agent used, cisplatin, encapsulated in the internal/nuclear part of the fiber, is the primary drug used in chemotherapy due to its high efficacy in cases of advanced cancer, but it causes nephrotoxicity, which is why, in many cases, it is replaced by other chemotherapeutics; however, its transport using the application of the fiber biofilm locally on the cervix could allow the reduction of adverse effects, including kidney damage, allowing its continued use. Furthermore, the developed pharmaceutical form is a relatively easy alternative to apply, similar to vehicles currently used at the cervical level, such as ovules with medication to control infections. The developed polymeric system allows the release of the drug in a constant and sustained manner controlled by the degradation rate of the polymers, allowing the drug's bioavailability for longer periods of time. This study aimed to evaluate the biofilm manufactured for its application in localized therapy for the treatment of cervical cancer. The goal was to reduce the side effects that the chemotherapeutic agent causes when applied systemically, which would improve the quality of life of patients during and after their healing process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polycaprolactone (PCL, Mn=80,000 g/mol) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Mn=40,000 g/mol) was purchased from Hunan Juren Chemical Hitechnology Co., Ltd., China. Chloroform and dimethylformamide (DMF) were obtained from J. T. Baker (USA). Cisplatin (CDDP) was supplied by Accord Farma (Mexico City). All other reagents were used as received without further purification. Female Wistar rats weighing 90 to 100 g were provided by the Bioterium of the Biosciences Center of the Faculty of Agronomy and Veterinary Medicine of the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí (FAV-UASLP).

2.2. Coaxial Fiber Biofilm Electrospinning

To fabricate the coaxial fiber biofilm by electrospinning, individual polymer solutions of polycaprolactone and polyvinylpyrrolidone were initially prepared, for which the choice of suitable solvents for their dissolution and the concentration-viscosity of the resulting solution were considered, a factor that directly impacts the formation of the fibers. The coating solution was prepared by dissolving PCL (30% w/v) in a mixture of chloroform: DMF (3:1). PVP (85% w/v), the polymer of the inner part of the fibers, was dissolved in the same solvent mixture but in a different proportion (chloroform: DMF 2:1). The polymer solutions were kept under constant magnetic stirring for 24 hours to achieve a homogeneous solution. The PVP solution was added to a cisplatin-DMF solution at two drug concentrations, 0.2 mg/mL and 0.6 mg/mL, according to previous reports of IC50 on SiHa, CaSki, C-33 A, and HeLa cells [

11,

17,

18,

19] and stirred for 12h. The PCL/PVP sheath/core fiber biofilm was fabricated by a coaxial electrospinning system (TL electrospinning & spray unit model TL-01 Tong Li Tech Co.). An experimental design was carried out to determine the optimal parameters, considering a review of previous reports and investigating the influence of process parameters on fiber formation; individual polymeric fibers were developed, and then coaxial electrospinning was carried out. The Supplementary Material provides additional information. Two individual syringes, connected via hoses in the concentric coaxial configuration, were used for the sheath and core solutions. The flow of polymer solutions was maintained using separate pumps, 3 mL and 2 mL, for the sheath and core parts, respectively. The applied electric voltage, the distance between the needle and the collector, and the rotation speed of the latter were 10 cm, 13-16 kV, and 230-290 rps. The resulting randomly deposited fibers were collected on waxed paper. The biofilm was left to dry in an oven to evaporate solvent residues. The fibers were observed with a Nikon Eclipse Ci POL petrographic microscope and NIS Element software during the optimization of the electrospinning process,

Figure 1G.

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of the Fibers

2.3.1. SEM Analysis

Morphological analysis of the fibrous biofilm was obtained by observation in a Helios G4 CX dual-beam scanning electron microscope (SEM) by mounting the samples on pieces of metal surfaces using double-sided conductive tape, using an acceleration voltage of 10 and 15 kV. Fiber diameters were analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, MD, USA). The average fiber diameter and percentage size distribution were determined from the SEM images by measuring 100 fiber segments randomly selected from 5 fields. To confirm the coaxial nature of the fibers, cross-sectional micrographs of a fractured fragment of the sample previously treated with liquid nitrogen were obtained.

2.3.2. FTIR Analysis

The presence of the polymer and drug functional groups in the coaxial fiber biofilm was determined by Attenuated total reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy analysis (ATR-FTIR) in the spectral region between the range of 500-4000 cm-1. Spectra were obtained for each sample: pure PCL, pure PVP, cisplatin, PCL/PVP fibers, and PCL/PVP/cisplatin fibers.

2.3.3. Contact Angle Analysis

To evaluate the fibrous biofilm's hydrophobic/hydrophilic nature, water contact angle measurements were carried out using a goniometer using the sessile drop technique (Biolin Scientific, Theta Lite) and analyzed with OneAttension software. A biofilm segment of coaxial fibers was placed on a glass slide. A drop of deionized water (2.5 µL) was placed on the surface of the fibers with a micrometer syringe; subsequently, images were captured to evaluate the contact angle using the Young-Laplace equation at 10 s time.

2.3.4. Tensile Test

To evaluate the biofilm's mechanical properties, the average tensile strength of the fibers was calculated using an Instron 3369 universal machine and Instron Bluehill Lite software; the test was performed at room temperature. The samples were cut to obtain a segment 10 cm long and 0.12 to 0.19 mm thick. The reference conditions for this test were a length of 100 mm and a speed of 1 mm/min. The force required for tearing was calculated as the tensile strength of the fibers. Four measurements were taken.

2.4. In Vitro Degradation Assay

The degradation of the fibrous biofilm was determined by measuring its weight loss and FTIR analysis. The biofilm was cut into small fragments (1 cm2) and incubated in PBS pH 4.07 as a test medium at 37°C for 10 and 14 days and 1, 3, and 6 months. After incubation, the biofilm fragments were rinsed with water, air-dried, and weighed to determine their weight loss due to degradation. The weights of 3 independent samples were measured for each time point. In addition, FTIR spectra of the biofilm fragments were obtained at the end of the test.

2.5. In Vitro Release Assay

Fragments weighing 20 mg of PCL/PVP/cisplatin fibrous biofilm were immersed in 10 mL of PBS (pH 4.07) at 37°C. At predetermined intervals, 1 mL of release buffer was removed for analysis and replaced with 1 mL of fresh PBS for continuous incubation. The amount of cisplatin present in the buffer was determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy at 202 nm. The results were presented as a percentage of cumulative release (Equation 1):

Qt is the amount of cisplatin released at time t, and QT is the total amount of cisplatin in the biofilm. Samples were processed in triplicate. The calibration curve was performed based on standard solutions of cisplatin with concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 1.4 mg/ml.

2.6. Hemolysis Assay

Erythrocyte suspension was used, which was exposed to segments of the fibrous biofilm. Incubation was carried out at 37°C for 3 hours with constant agitation. The samples were then centrifuged at 1400 rpm for 10 min, and the absorbance of hemoglobin released in the supernatant (1 mL) was recorded at 545 nm. NanodropOne thermoscientific was used to measure absorbance. The erythrocyte suspension with PBS was taken as a negative control, while the erythrocyte dilution with 20% Triton-X-100 was taken as a positive control. The blank was 1x PBS. The assay was performed in triplicate. The percentage of hemolysis was calculated using the following equation (Equation 2):

2.7. Biocompatibility Assay

For this assay, NIH3T3 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) were used. Cell viability was determined using the MTT method. The assay aimed to evaluate the biocompatibility of PCL/PVP fibers in non-cancerous cells. A disk of approximately 10 mg of PCL/PVP fiber biofilm weight (previously sterilized under UV light) was added to the wells (96-well plate) with medium and cells in triplicate, and they were incubated for 24 h. As a negative control, wells with cells in culture medium were used, and as a positive control, cells treated with a 10% hydrogen peroxide solution were used. After incubation, the culture medium and treatments were removed and 50 µL of MTT solution was added. The microplate was incubated at 37°C, 5% CO

2 for 4 hours. After incubation, it was transferred to a microplate reader with a 570 nm filter to read the absorbance. Cell viability was calculated relative to cell viability under control conditions (Equation 3):

OD570e = is the mean value of the measured optical density of the test sample.

OD570b = is the mean value of the measured optical density of the blank.

2.8. Cytotoxicity Assay

HeLa cells (1x104)/well were seeded with exposure to segments of electrospun coaxial fibers to evaluate their cytotoxic capacity and cultured for 72 h. 50 μL of MTT 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for four hours. The absorbance was observed at 570 nm, as described in the previous paragraph.

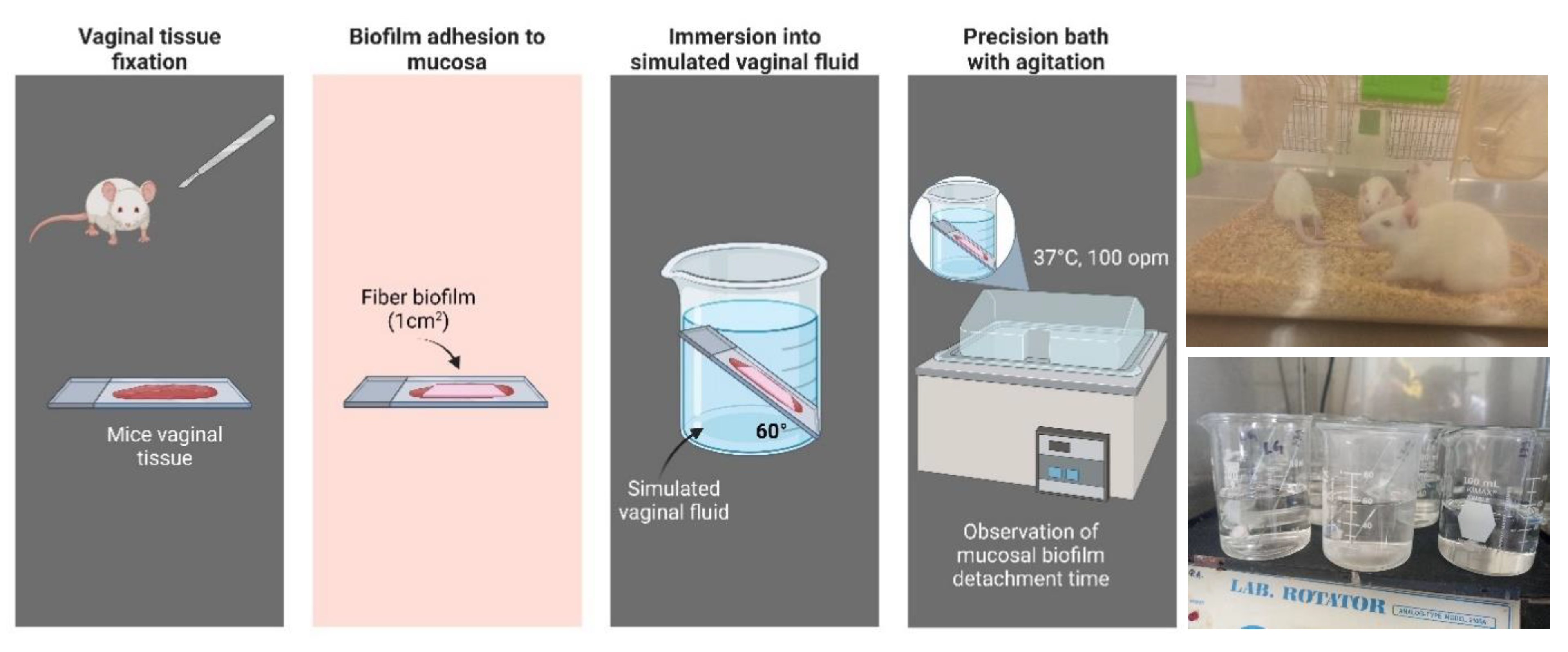

2.9. Assessment of Mucoadhesion

Four female Wistar rats (~90-100 g) were used for this assay, from which the vaginal tissue was carefully isolated to preserve the mucosa; the protocol for its use in this assay was approved by the CIACYT Research Ethics Committee (registration number CIACYT-CEI-007). To humanely euthanize the rats, the procedure was carried out following the Mexican Official Standard NOM-062-ZOO-1999, which dictates the technical specifications for the production, care and use of laboratory animals to eliminate or minimize pain and stress. The animal was placed in a closed receptacle containing cotton soaked with chloroform, ensuring that the skin was not in direct contact with the anesthetic; inhalation of the vapors led to cessation of breathing and death. To determine the residence time of the biofilm on the mucosa, a vaginal tissue sample was fixed to a glass slide with cyanoacrylate adhesive; the nanofiber biofilm fragment (1cm2) was then adhered to the mucosa by applying a pressure of 500 g for 30 s. It was then placed at a 60° angle into a beaker with simulated vaginal fluid (SVF). The preparation was placed in a precision shaking bath (100 opm) at a temperature of 37°C. Residence time was determined by observation of the samples in quadruplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Evaluation

SEM micrographs showed developed fibers with continuous morphology, without beads or interrupted segments, with a rough surface and random orientation, as shown in

Figure 1. The concentration and viscosity of the polymer solution play an essential role in obtaining fibers since an excessive increase in viscosity prevents the passage of the solution through the capillary in the electrospinning system; on the other hand, very low viscosity values generate breakage of the fibers in the form of drops [

20]. The average diameters obtained by analysis with ImageJ software were compared between fibers without CDDP and fibers with this drug. The average diameter of coaxial fibers without the drug was 4.43 ± 1.18 µm; coaxial fibers PCL/PVP loaded with the drug presented an average diameter of 5.78 ± 2.41 µm and 6.72 ± 2.29 µm for loading 0.2 mg and 0.6 mg of cisplatin, respectively. According to the results obtained, the cisplatin fibers showed a slight increase in the average diameter, which could be attributed to the ionic nature of cisplatin, which when added to the PVP nuclear solution for electrospinning, increased the voltage necessary to obtain the fibers, which consequently increased the diameter; that is, the composition of the polymer-drug solution affects parameters of the electrospinning process such as voltage, which produces variations in the size or morphology of the fibers [

20,

21].

Furthermore, as shown in the SEM micrograph in

Figure 2, a clear differentiation between the core and sheath layers of the fiber is observed, confirming the successful formation of the PCL/PVP coaxial fiber, as already reported in previous works [

22,

23]. These results allow determine that the CDDP drug was found encapsulated in the polymeric core part of the fiber; furthermore, the delimitation between the inner and outer layers of the fiber was achieved by the fast and efficient electrospinning process even though the mixture of solvents used for the preparation of the polymeric solutions was the same except for the proportions of each solvent, the immiscibility of the polymeric solutions was achieved [

24].

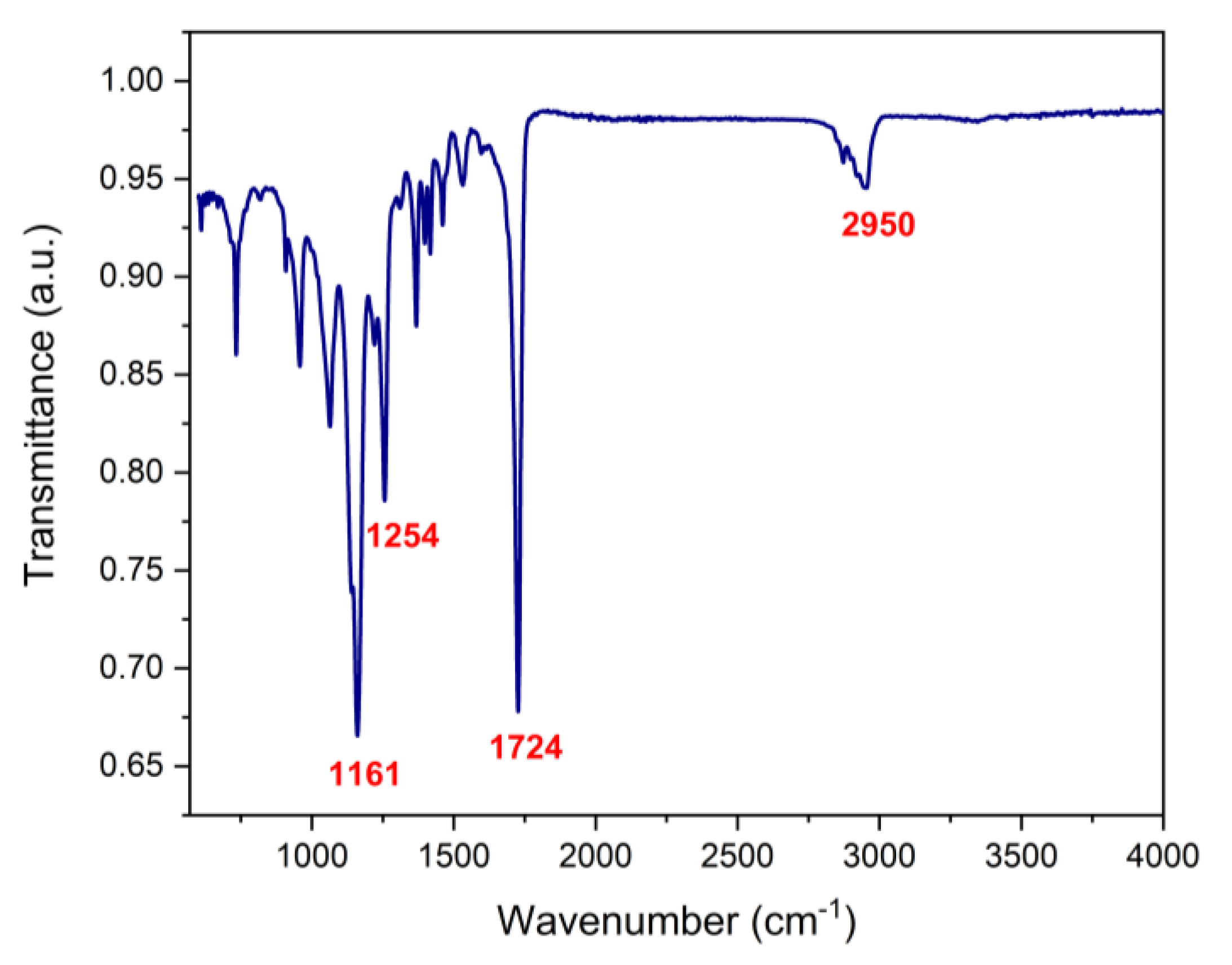

3.2. FTIR Analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was used to determine the presence of the biopolymers and cisplatin in the biofilm.

Figure 3 shows the transmittance spectra of PCL, PVP, cisplatin and PCL/PVP biofilm with and without the drug. Characteristic PCL bands are observed at 1161 cm

-1 (C-O stretching), 1254 cm

-1 (C-O-C stretching), 1724 cm

-1 (C=O stretching), 2865 cm

-1 (CH

2 symmetric stretching), 2950 cm

-1 (C-H stretching). The bands 1290 cm

-1 (CH

2 twisting), 1496 cm

-1 (CH

2 scissor mode), 1660 cm

-1 (C=O stretching) belong to polyvinylpyrrolidone components [

25,

26]. Finally, the bands corresponding to cisplatin were 799 cm

-1 (N-H stretching), 1290 cm

-1 (symmetric amine bending mode), 3200 cm

-1 (amine stretching), 3280 cm

-1 (amine stretching), 1536 cm

-1 (N-H stretching) and a prominent band of 1311 cm

-1 (N-H stretching), which can be observed in the spectra of drug-loaded biofilms [

11]. The appearance of bands corresponding to polymers and cisplatin in the spectra demonstrates their presence in the manufactured fibers.

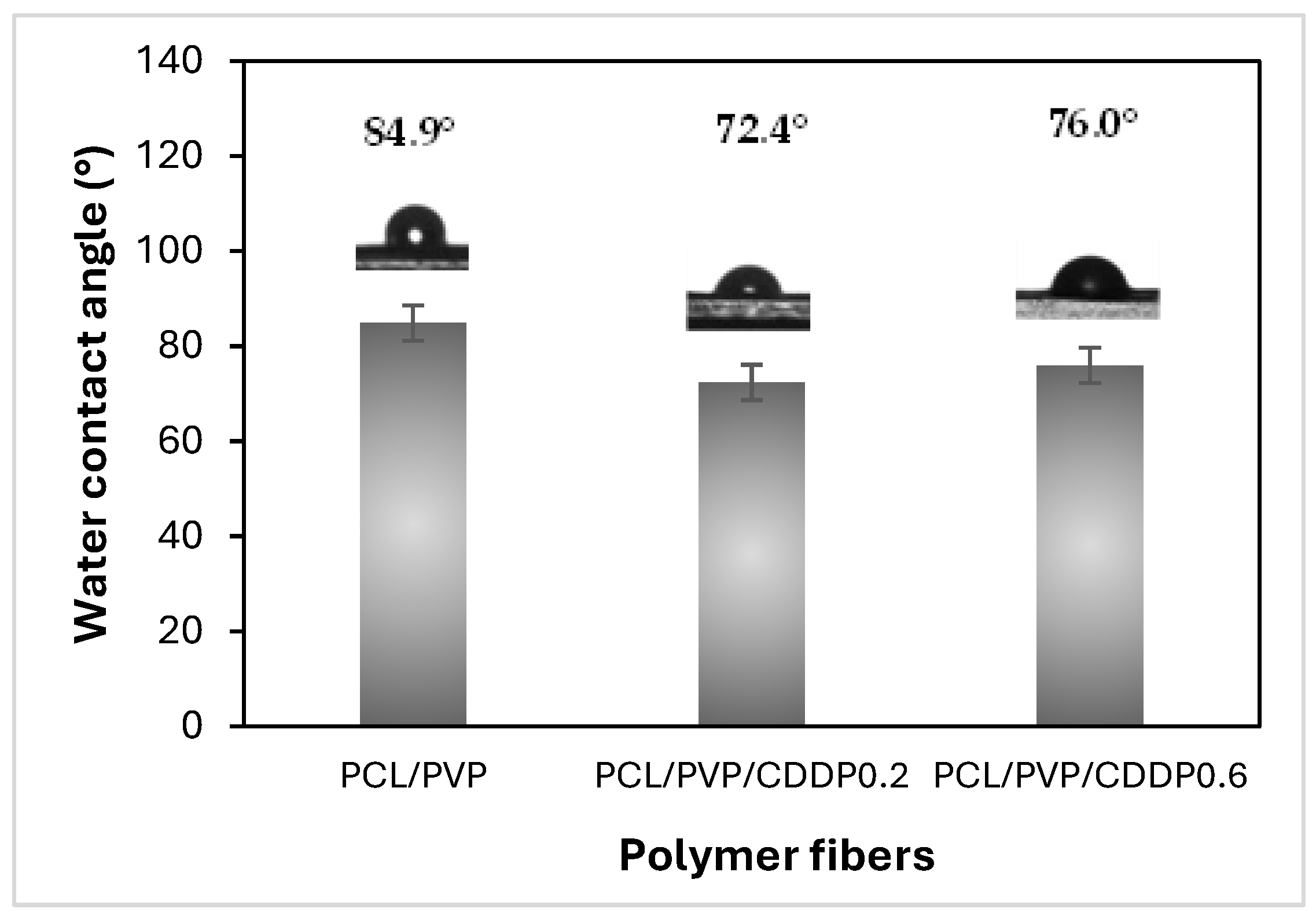

3.3. Contact Angle

Contact angle measurement is an indicator of the degree of hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, which can predict the wettability, adhesion and dissolution capacity of fibrous biofilm in the vaginal environment. In addition, wettability is of great importance for the subsequent diffusion of the drug carried by polymeric fibers [

27,

28]. The contact angle classification is divided into four categories depending on the angle value measured. Surfaces with an angle <25° and 25 to 90° are considered super hydrophilic and highly hydrophilic, respectively. On the other hand, if the measured surface has an angle of 90 to 150° or >150°, it is hydrophobic or superhydrophobic; the smaller the contact angle with water, the more hydrophilic the surface of the material. As shown in

Figure 4, both biofilms of coaxial fibers without CDDP and those loaded with the drug are highly hydrophilic since the contact angle value was less than 90° [

10]. In previous studies, water contact angle values of 115 to 130° have been reported in PCL composite fibers, which confirms their hydrophobic nature [

8,

15]. However, when combined with other polymers of a hydrophilic nature, such as chitosan or PVP, either in uniaxial or coaxial sheath/core fibers, the contact angle decreases, improving the hydrophilicity of the material surface. Although the fibers developed in this work comprise hydrophobic PCL, the hydrophilic PVP polymer favors the biofilm's hydrophilicity. The improved hydrophilicity caused by the action of PVP, which is not found on the fibers' surface, may be due to low amounts of this polymer present in the sheath part; the fibers' porosity and the relative permeability of PCL enable this filtration.

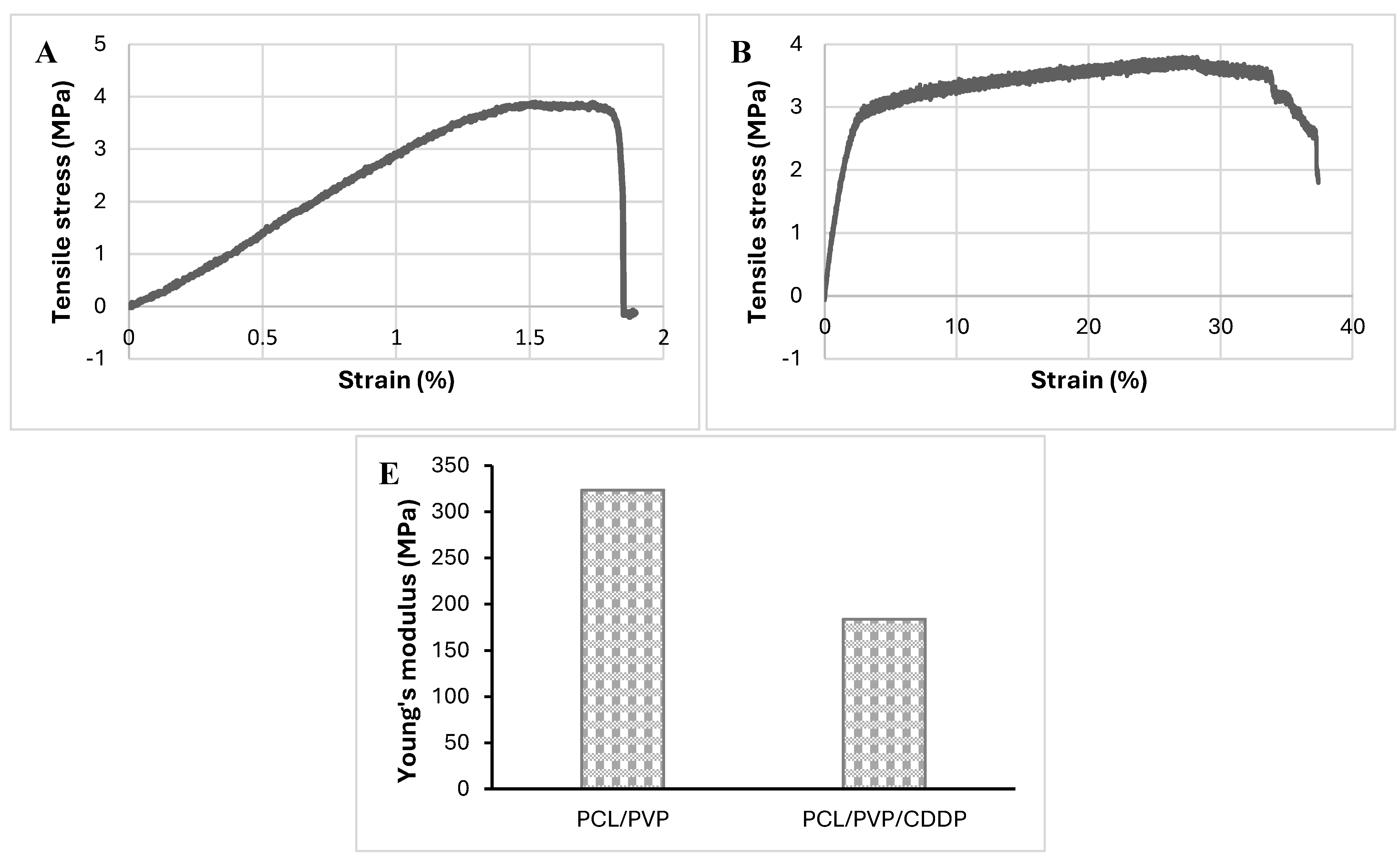

3.4. Mechanical Properties of Coaxial Fibrous Biofilm

The mechanical strength of PCL/PVP and PCL/PVP/CDDP biofilm was determined using the Instron universal machine.

Figure 5 shows the stress-strain curves and Young's modulus graph. PCL/PVP biofilm presented tensile strength and strain of 3.88 MPa and 1.52 ± 0.27%, respectively. On the other hand, the biofilm with incorporated CDDP showed similar tensile strength (3.80 MPa); however, the % strain was higher (27.12 ± 7.02%, 17 times higher). Similar results have been reported in previous studies where increased resistance to deformation was reported in nanofibers loaded with cisplatin and other drugs compared to the deformation in plain nanofibers [

10,

29]. Additionally, the results of Young's modulus showed a noticeable difference between the fibers with CDDP and those without it, being higher in the latter (174.5 MPa vs 309.6 MPa), which indicates that the biofilm without pharmacological load presents greater rigidity and resistance to deformation, however, as shown in the stress-strain curves, the PCL/PVP/CDDP biofilm offers a high deformation capacity before breaking occurs, therefore, although it is less rigid, it may be a convenient option for vaginal application. Although it has been reported in previous works that the addition of PVP to PCL and other polymers in the manufacture of fibers compromises their mechanical properties due to poor interaction between polymers [

30,

31], in the fibers developed in this work of PCL/PVP, the synergy between both polymers combined the good mechanical resistance of PCL with the dissolving properties of PVP for pharmacological release [

32,

33,

34].

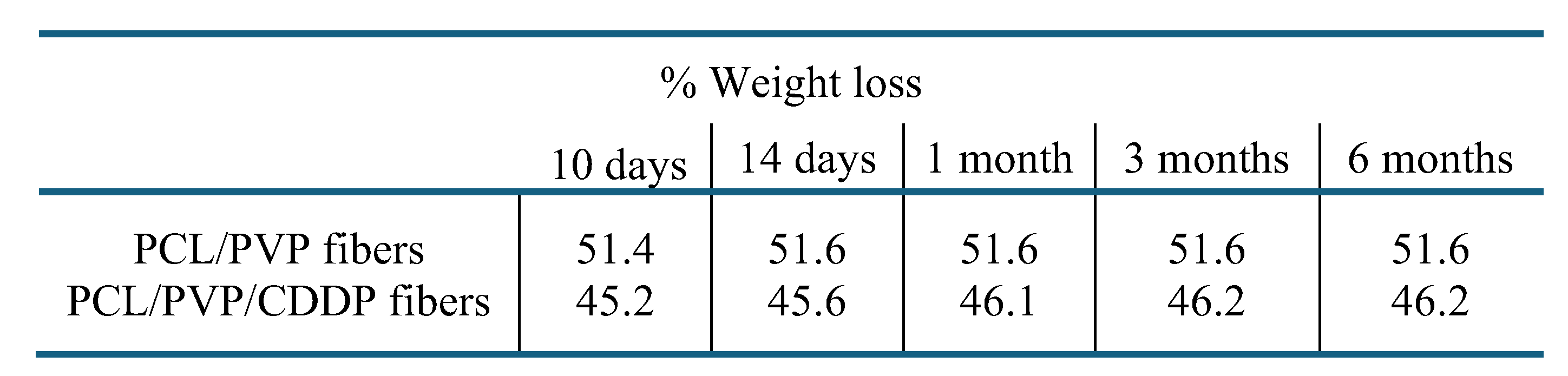

3.5. Biofilm Degradation

The degradation of the coaxial fiber biofilm was determined by measuring its weight loss during different time intervals (

Table 1). Notable weight loss occurred from the tenth day both in the fibers without cisplatin and in those containing it (51.4% and 45.2%); however, at the end of the test, the percentage of weight loss did not vary greatly with respect to that observed on day 10. These results demonstrate the biodegradability of the developed biofilm. The pH of the test solution, which was initially low (4.07), similar to the acidic vaginal environment, did not show significant variations. Infrared spectra of the fiber fragments were obtained at the end of the test and it was determined that the weight loss occurred due to the degradation of the PVP polymer; in the spectrum (

Figure 6), bands corresponding only to the PCL polymer are observed at positions 1161 cm

-1 (C-O stretching), 1254 cm

-1 (C-O-C stretching), 1724 cm

-1 (C=O stretching) and 2950 cm

-1 (C-H stretching); however, the bands corresponding to PVP do not appear, indicating that this last polymer is not present and has already been degraded. Previous studies have reported similar results in degradation assays of PCL and PVP polymers, finding that the latter dissolves rapidly. At the same time, PCL requires a longer time to degrade [

35]. PCL has been described to have a long time for hydrolytic degradation [

36]; working groups have reported low degradation rates in coaxial fibers of which PCL is a part; additionally, they determined that the weight loss was mainly due to other hydrophilic polymers that are part of the polymeric structure [

37,

38]. In our laboratory, the real-time degradation test (ISO 10993-13 standard) is being conducted, in which the exposure time is extended to determine the time of complete degradation of the biofilm.

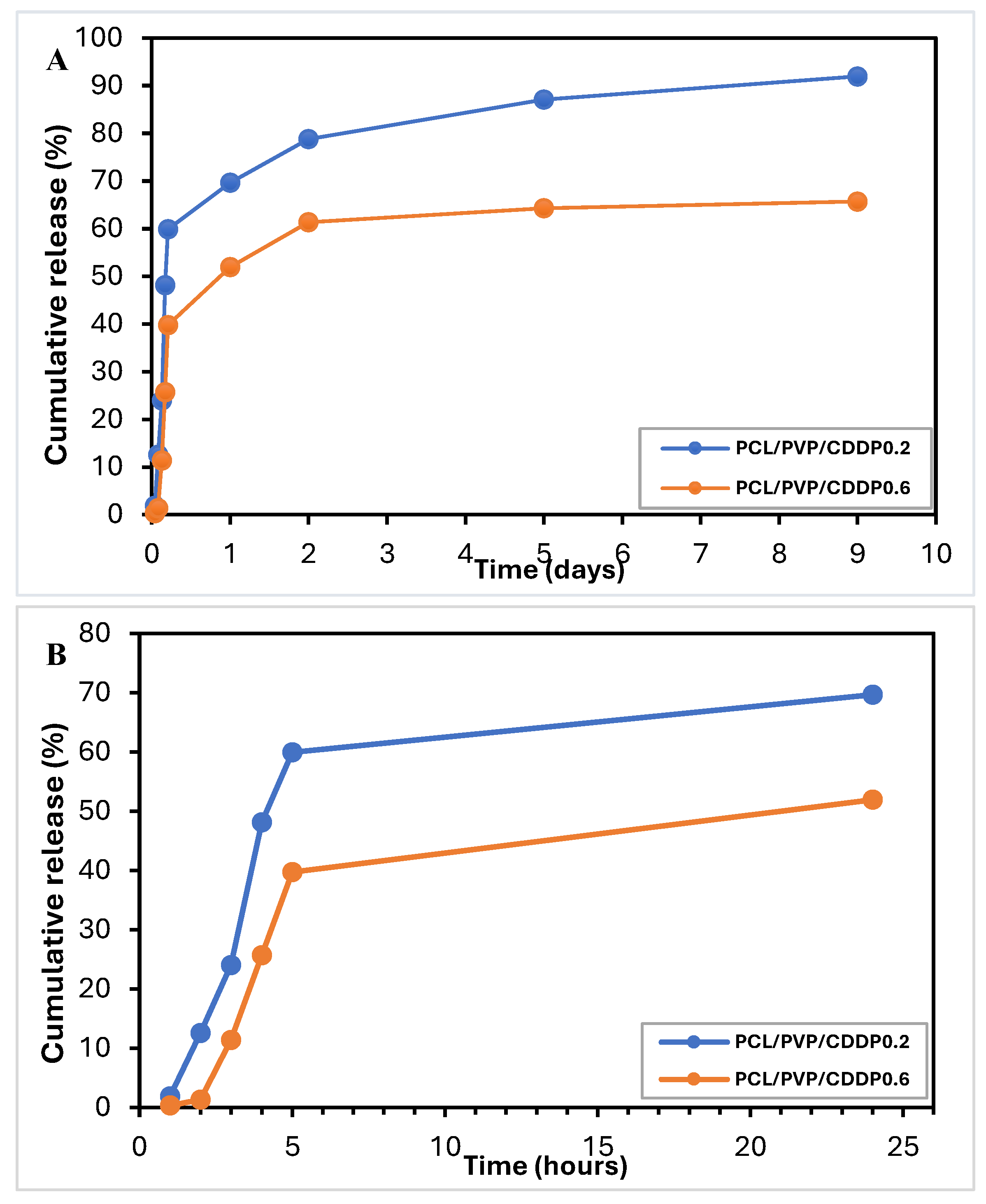

3.6. In Vitro Release of Cisplatin

The use of micro/nanofibers as drug delivery systems by electrospinning provides the possibility of efficient encapsulation. The encapsulation efficiency was calculated (EE%=( Amount of free CDDP in the supernatant/Total amount of CDDP added)*100) by UV-Vis spectroscopy measurements at 202 nm after the complete dissolution of a fiber fragment in PBS. The encapsulation efficiency of cisplatin was ~75-92%, which is consistent with similar values of % encapsulation of cisplatin and other bioactive substances in nanofibers reported in previous studies [

10,

14,

29]. Data from the in vitro cisplatin release test from coaxial fibrous biofilm are presented in

Figure 7A, B. The samples showed a biphasic release profile: initially, a rapid release followed by a slow and sustained release. The explosive release of the first stage occurred in the first 5 hours, reaching a CDDP release of 59.9% and 39.7%. After this initial release, the constant and sustained release of the drug occurred, finding a cumulative release on day 9 of 92% and 65.7% for the fibers with lower and higher cisplatin load, respectively; this two-stage release of CDDP and other bioactive substances as tissue regeneration promoters from polymeric nanofibers has already been reported by other working groups [

17,

39]. The release mechanism is probably diffusion through the manufactured fibers' pores, holes or imperfections. Because PVP is a hydrophilic polymer and therefore soluble in water, it dissolves, releasing CDDP (initial release phase) and, in turn, creates pores through which the buffer can penetrate to the innermost part of the coaxial fiber to achieve diffusion and release of the remaining CDDP during the second slow and sustained phase. Other working groups have described similar results for releasing substances such as bioactive agents through devices composed of simple or coaxial polymeric fibers [

40,

41]. This hypothesis can be confirmed by the results of the degradation test, where the weight loss was approximately half of the initial weight and the FTIR spectrum shows the absence of the PVP polymer, indicating its dissolution. Furthermore, according to the results obtained from the water contact angle measurements, the surface of the fibrous biofilm is highly hydrophilic since the values obtained were low, therefore, the surface (PCL coating) probably contains PVP in low quantities due to filtration from the nuclear part of the fiber, which contributes to the formation of cavities that facilitate drug diffusion. In turn, due to its hydrophobic nature, the presence of coaxial fibers of PCL polymer in the shell reduces the explosive release. Previous studies have already reported that PCL can function as a protective barrier to prevent rapid drug release in core-shell structures [

10,

27]. According to the cisplatin release profile in our study, it is possible to use the biofilm of coaxial fibers shell/core PCL/PVP as a controlled-release delivery system.

3.7. In Vitro Biosafety Assays of the Fibrous Biofilm

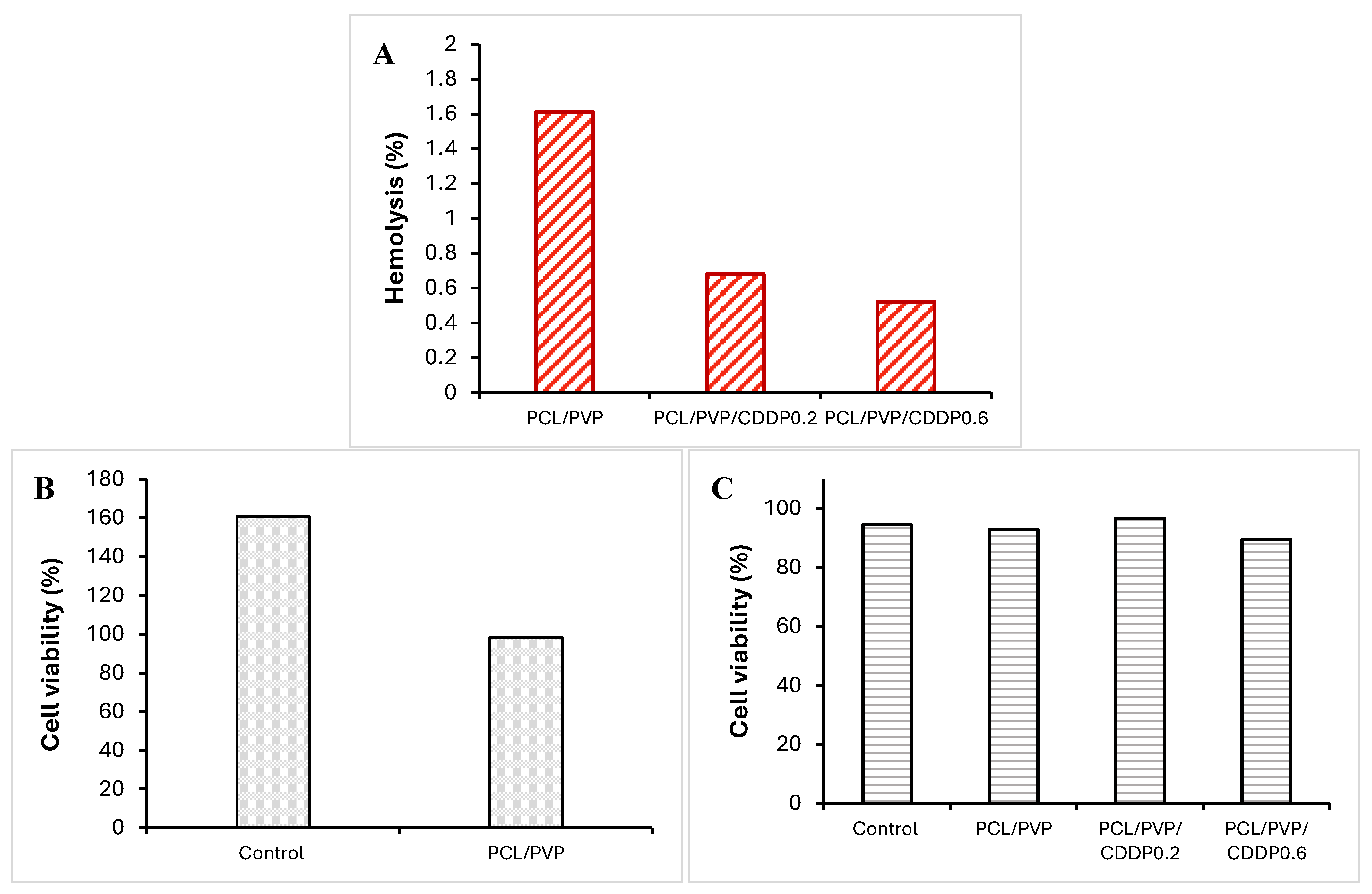

The % hemolysis, biocompatibility and cytotoxicity of the coaxial fibrous biofilm on erythrocytes, NIH3T3 cells and HeLa cells were evaluated, respectively; graphs with the results are shown in

Figure 8. The % hemolysis for PCL/PVP fibers without the drug was 1.61%, while for fibers loaded with 0.2 mg and 0.6 mg of cisplatin, the % hemolysis was 0.68% and 0.52%, respectively,

Figure 8A. That is, all fiber segments tested in the analysis presented % hemolysis less than 2%, which is lower than accepted values (<5%) as proposed by ASTM F756-00 [

42]. Therefore, PCL/PVP coaxial fibers can be used in localized cervical cancer therapy without causing hemolysis of red blood cells since the very low hemolysis percentage indicates good blood compatibility of the biopolymers. According to the results obtained in the biocompatibility test performed on NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts, when exposed to coaxial PCL/PVP fibers, no toxicity occurred, showing high cell viability, so these biomaterials were biocompatible (figure 8B). Previous studies have reported the excellent compatibility of PCL polymer fibrous scaffolds in mouse dermal fibroblasts and human dermal fibroblasts [

35,

43,

44,

45]. On the other hand, the results obtained in the cytotoxicity assay in HeLa cells showed similar cell viability in cells exposed to PCL/PVP fibers without drug with control cells (93.1% vs 94.4%). When comparing cells exposed to fibers with CDDP at low concentration with control cells, it was observed that viability is comparable (96.7%); however, cells exposed to fibers loaded with cisplatin at a higher concentration exhibited a slight decrease in cell viability (89.3%),

Figure 8C; which suggests the need for a higher drug load within the fibers or the fibers contain the drug efficiently encapsulated in its nuclear part of PVP and a longer exposure time to the fiber biofilm is necessary since the cytotoxicity assay was carried out with 24-hour exposure. The encapsulation efficiency allows using the developed fiber system as a local drug carrier with controlled release, dependent on polymeric degradation.

3.8. Mucoadhesion and Residence Time

Local therapy aims to administer cisplatin chemotherapy using the developed fiber biofilm through the vaginal route, which provides easy access to the cervix and is currently used for the application of bioactive substances through various pharmaceutical forms such as ovules or gels. The mucoadhesion test allowed the evaluation of the capacity of the biofilm to adhere to the vaginal mucosa at the time of administration since the objective is to maintain it for an extended period to allow the release of the drug in a sustained and controlled manner. The simulated vaginal fluid used in the test mimics the vaginal environment [

46,

47]. The constant production and secretion of fluids is a factor that could affect the permanence of the fibrous biofilm and, consequently, the release of the transported drug. Adherence to the vaginal mucosa of the fibrous biofilm fragments was observed for more than 15 days, with no sign of detachment despite being kept under constant agitation and in FVS,

Figure 9. These results allowed us to determine that the biofilm has a high mucoadherence to the vaginal wall. To obtain an effective localized delivery system for chemotherapeutic agents at the vaginal level, it must comply with the critical characteristic of adherence since, in this way, it ensures that the biofilm remains in place for a sufficient period for the release of the drug. The PVP polymer, a component of the fibrous biofilm, provides adhesive properties that improve the intravaginal mucoadherence of the biofilm [

48,

49].

4. Conclusions

The coaxial electrospinning technique successfully developed the biofilm of cisplatin-loaded polycaprolactone/polyvinylpyrrolidone shell/core fibers. The fabricated fibers showed continuous, bead-free morphology, defined shell/core structure, and diameters ranging from 3 to 9 µm, which could be a promising drug microcarrier system. The microfibers demonstrated a two-phase cisplatin release profile: an initial burst release followed by a slow release over 8 days. Polycaprolactone provided mechanical strength to the fibers and, due to its long hydrolytic degradation time and hydrophobic nature, it was possible to avoid explosive release of all the encapsulated drug; on the other hand, polyvinylpyrrolidone provided hydrophilic and adhesive properties to the surface of the fibers, which favors dissolution in the vaginal environment and mucoadhesion of the biofilm to the intravaginal wall long enough to allow the release and bioavailability of the drug at the target site. The fibrous biofilm exhibits high cytocompatibility, as demonstrated by erythrocytes and NIH3T3 cells exposure. The developed drug delivery system using microfibers could improve the efficacy of cisplatin treatment through local application. Based on the results obtained, the fibrous biofilm presents desirable characteristics for use as a drug delivery system in the treatment of cervical cancer; however, it is essential to carry out ex vivo and in vivo studies in order to use it in patients. The use of combinations of polymers with different properties and the electrospinning technique with its modifiable parameters allows the fabrication of nano and microstructures with improved characteristics such as mucoadhesiveness and optimal release profiles for their application in treating this complex disease. This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Additional information is provided in the Supplementary Material. The graphical abstract was created in BioRender,

https://BioRender.com/b68b902. It is licensed under an Academic Publishing License.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data processing, methodology, validation, writing - original draft, M.S.S.-L; funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, review and editing, L.E.A.-Q. and V.A.E.-B; research, M.S.S.-L. and L.E.A.-Q. The authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.S.S.-L. Acknowledging the financial support of CONAHCYT through a postdoc scholarship 479977 and project 2092. This research received no external funding, public, commercial or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of CIACYT Research Ethics Committee (registration number CIACYT-CEI-007, October 13, 2023).

Data Availability Statement

Specific queries regarding the data of this study may be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Advanced Materials Division and the Applied Geosciences Laboratory of the Instituto Potosino de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica for allowing us to use their equipment and facilities. The authors also acknowledge the Laboratory of Biomedical Applications of Optoelectronics-CIACYT-UASLP, where the FTIR measurements for this study were performed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Cáncer cervicouterino, datos y cifras (2020). Cáncer cervicouterino (who.int).

- Pan American Health Organization. Plan of Action for Cervical Cancer. Prevention and Control 2018–2030. 2018. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/plan-action-cervical-cancer-prevention-and-control-2018-2030.

- Wang, X., Liu, S., Guan, Y., Ding, J., Ma, C., Xie, Z. (2021). Vaginal drug delivery approaches for localized management of cervical cancer. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 174, 114–126. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., Gupta, M. K. (2017). Possible role of nanocarriers in drug delivery against cervical cancer. Nano Reviews & experimentos, 8, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Ordikhani, F., Arslan, M. E., Marcelo, R., Sahin, I., Grigsby, P., Schwarz, J. K., Azab, A. K. (2016). Drug Delivery Approaches for the Treatment of Cervical Cancer. Pharmaceutics, 8, 23. [CrossRef]

- Cevher, E., Acma, A., Sinani, G., Aksu, B., Zloh, M., Mulazimoglu, L. (2014). Bioadhesive tablets containing cyclodextrin complex of itraconazole for the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 69, 124–136. [CrossRef]

- Fan, M., Ferguson, L., Rohan, L., Meyn, L., Hillier, S. (2011). Vaginal film microbicides for HIV prevention: a mixed methods study of women’s preferences. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 87, A263. [CrossRef]

- Mosallanezhad, P., Nazockdast, H., Ahmadi, Z., Rostami. (2022). A. Fabrication and characterization of polycaprolactone/chitosan nanofibers containing antibacterial agents of curcumin and ZnO nanoparticles for use as wound dressing. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 1027351. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Sinha-Ray, S. (2018). A Review on Biopolymer-Based Fibers via Electrospinning and Solution Blowing and Their Applications. Fibers, 6, 1-53.

- Yaoa, Z. C., Wanga, J. C., Ahmad, Z., Lia, J. S., Chang, M. W. (2019). Fabrication of patterned three-dimensional micron scaled core-sheath architectures for drug patches. Materials Science & Engineering C., 97, 776–783.

- Keskar, V., Mohanty, P. S., Gemeinhart, E. J., Gemeinhart R. A. (2006). Cervical cancer treatment with a locally insertable controlled release delivery system. Journal of Controlled Release, 115, 280–288.

- Muhammad, Z. A. Z., Darman, N., Norazuwana, S., Siti, K. K. (2023). Overview of Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering Applications. Polymers (Basel), 15(11), 2418.

- Siddiqui, N., Kishori, B., Rao, S., Anjum, M., Hemanth, V., Das, S., Jabbari, E. (2021). Electropsun Polycaprolactone Fibres in Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Molecular Biotechnology. 63, 363–388. [CrossRef]

- Sruthi, R., Balagangadharan, K., Selvamurugan, N. (2020) Polycaprolactone/polyvinylpyrrolidone coaxial electrospun fibers containing veratric acid-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for bone regeneration. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 193, 111110.

- Ajinkya, A. S., Piyush, R., Prabhanjan, G., Pr Regulation of biphasic drug release behavior by graiyanka, R., Anand, K., Baijayantimala, G., Neeti, S. (2020). Poly (vinylpyrrolidone) iodine engineered poly (ε-caprolactone) nanofibers as potential wound dressing materials. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 110, 110731.

- López-Mendoza, C. M., Terán-Figueroa, Y., Alcántara-Quintana, L.E. (2020). Use of biopolymers as carriers for cancer treatment. Journal of bioengineering and biomedicine research, 4 (2), 6-22.

- Zong, S., Wang, X., Yang, Y., Wu, W., Li, H., Ma, Y., Lin, W., Sun, T., Huang, Y., Xie, Z., Yue, Y., Liu, S., Jing, X. (2015). The use of cisplatin-loaded mucoadhesive nanofibers for local chemotherapy of cervical cancers in mice. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 93, 127–135.

- Słonina, D., Kabat, D., Biesaga, B., Janecka-Widła, A., Szatkowski, W. (2021). Chemopotentiating effects of low-dose fractionated radiation on cisplatin and paclitaxel in cervix cancer cell lines and normal fibroblasts from patients with cervix cancer. DNA Repair (Amst), 103, 103113.

- Li, M., Lu, B., Dong, X., Zhou, Y., He, Y., Zhang, T., Bao, L. (2019). Enhancement of cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity against cervical cancer spheroid cells by targeting long non-coding RNAs. Pathology-Research and Practice, 215(11), 152653. [CrossRef]

- Haider, A., Haider, S., Kang, I. K. (2018). A comprehensive review summarizing the effect Of Electrospinning parameters and potential applications of nanofibers in biomedical and biotechnology. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 11, 1165-1188.

- Duque Sánchez, L. M., Rodriguez, L., López, M. (2014). Electrospinning: la era de las nanofibras. Revista Iberoamericana de Polímeros, 14, 10-27.

- Lee, B. S., Yang, H. S., Yu, W. R. (2014). Fabrication of double-tubular carbon nanofibers using quadruple coaxial electrospinning. Nanotechnology, 25 (46), 465602.

- Lee, B. S., Jeon, S. Y., Park, H., Lee, G., Yang, H. S., Yu, W. R. (2014). New electrospinning nozzle to reduce jet instability and its application to manufacture of multi-layered nanofibers. Scientific Reports, 4, 6758. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Zussman, E., Yarin, A., Wendorff, J., Greiner, A. (2003). Compound Core–Shell Polymer Nanofibers by Co-Electrospinning. Advanced Materials, 15, 1929-1932.

- Cam. M. E., Ertas, B., Alenezi, H., Hazar-Yavuz, A. N., Cesur, S., Ozcan, G. S., Ekentok, C., Guler, E., Katsakouli, C., Demirbas, Z., Akakin, D., Eroglu, M. S., Kabasakal, L., Gunduz, O., Edirisinghe, M. (2021). Accelerated diabetic wound healing by topical application of combination oral antidiabetic agents-loaded nanofibrous scaffolds: An in vitro and in vivo evaluation study. Materials Science & Engineering C materials for biological applications, 119, 111586.

- Chi, Z., Zhao, S., Feng, Y., Yang, L. (2020). On-line dissolution analysis of multiple drugs encapsulated in electrospun nanofibers. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 588, 119800.

- Park, S.C., Kim, M.J., Choi, K., Kim, J., Choi, S.O. (2018). Influence of shell compositions of solution blown PVP/PCL core-shell fibers on drug reléase and cell growth. RSC Adv, 8 (57), 32470-32480.

- Banafshe, A., Nazanin, G., Saman, B., Jaleh, T., Mahboubeh, A., Hamid, F. (2022). Electrospun hybrid nanofibers: Fabrication, characterization, and biomedical applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 10, 986975.

- Aggarwal, U., Goyal, A. K., Rath, G. (2017). Development and characterization of the cisplatin loaded nanofibers for the treatment of cervical cancer. Materials Science and Ingeneering C, 75, 125-132.

- Sun, B., Duan, B., Yuan, X. (2006). Preparation of core/shell PVP/PLA ultrafine Fibers by coaxial Electrospinning. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 102, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, S., Afshar, S., Rostami, A., Ghazalian, M., Nazockdast, H. (2020). Co-electrospun poly(lactic acid)/gelatin nanofibrous scaffold prepared by a new solvent system: morphological, mechanical and in vitro degradability properties. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials, 70(8), 545–553.

- Kumar, N., Sridharan, D., Palaniappan, A., Dougherty, J. A., Czirok, A., Isai, D. G., Mergaye, M., Angelos, M. G., Powell, H. M., Khan, M. (2020). Scalable Biomimetic Coaxial Aligned Nanofiber Cardiac Patch: A potential model for “clinical trials in a dish”. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8, 567842. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., Yang, P., Jia, Y., Zhang, Y., Ye, Q., Zeng, S. (2016). Regulation of biphasic drug release behavior by graphene oxide in polyvinyl pyrrolidone/poly(ε-caprolactone) core/sheath nanofiber mats. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 146, 63-9.

- Labet, M., Thielemans, W. (2009). Synthesis of polycaprolactone: a review. Chemical Society Reviews, 38(12), 3484-504. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Suárez, A. S., Dastager, S. G., Bogdanchikova, N., Grande, D., Pestryakov, A., García-Ramos, J. C., Pérez-González, G. L., Juárez-Moreno, K., Toledano-Magaña, Y., Smolentseva, E., Paz-González, J. A., Popova, T., Rachkovskaya, L., Nimaev, V., Kotlyarova, A., Korolev, M., Letyagin, A., Villarreal-Gómez, L. J. (2020). Electrospun Fibers and Sorbents as a Possible Basis for Effective Composite Wound Dressings. Micromachines (Basel), 11(4), 441.

- Sun, H., Mei, L., Song, C., Cui, X., Wang, P. (2006). The in vivo degradation, absorption and excretion of PCL-based implant. Biomaterials, 27, 1735–1740.

- Masoumi, N., Larson, B. L., Annabi, N., Kharaziha, M., Zamanian, B., Shapero, K.S., Cubberley, A. T., Camci-Unal, G., Manning, K.B., Mayer, J.E., Khademhosseini, A. (2014). Electrospun PGS: PCL Microfibers Align Human Valvular Interstitial Cells and Provide Tunable Scaffold Anisotropy. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 3, 929–939.

- Hou, L., Zhang, X., Mikael, P. E., Lin, L., Dong, W., Zheng, Y., Simmons, T. J., Zhang, F., Linhardt, R.J. (2017). Biodegradable and Bioactive PCL-PGS core-shell fibers for tissue engineering, American Chemical Society Omega, 2, 6321–6328. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. C., Udangawa, R. N., Chen, J., Mancinelli, C. D., Garrudo, F. F., Mikael, P. E., Cabral, J., Ferreira, F. C., Linhardt, R. (2020). Kartogenin-loaded coaxial PGS/PCL aligned nanofibers for cartilage tissue engineering. Materials Science & Engineering C, Materials for Biological Applications, 107, 110291.

- Zhang, Y. Z., Wang, X., Feng, Y., Li, J., Lim, C. T., Ramakrishna, S. (2006). Coaxial Electrospinning of (Fluorescein Isothiocyanate-Conjugated Bovine Serum Albumin)-Encapsulated Poly(E-caprolactone) Nanofibers for Sustained Release. Biomacromolecules, 7, 1049-1057.

- Hongliang J., Yingqian H., Pengcheng Z., Yan L., Kangjie Z. (2006). Modulation of Protein Release from Biodegradable Core–Shell Structured Fibers Prepared by Coaxial Electrospinning. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research part B Applied Biomaterials, 79(1), 50-7.

- ASTM F756-17, 2017, Standard Practice for Assessment of Hemolytic Properties of Materials. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA (CRD217).

- Viscusi, G., Paolella, G., Lamberti, E., Caputo, I., Gorrasi, G. (2023). Quercetin-Loaded Polycaprolactone-Polyvinylpyrrolidone Electrospun Membranes for Health Application: Design, Characterization, Modeling and Cytotoxicity Studies. Membranes (Basel), 13(2), 242.

- Zhao, P., Jiang, H., Pan, H., Zhu, K., Chen, W. (2007). Biodegradable fibrous scaffolds composed of gelatin coated poly(e-caprolactone) prepared by coaxial Electrospinning. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 83(2), 372-82.

- Sadeghi-avalshahr, A. R., Nokhasteh, S., Molavi, A. M., Mohammad-pour, N., Sadeghi, M. (2020). Tailored PCL Scaffolds as Skin Substitutes Using Sacrificial PVP Fibers and Collagen/Chitosan Blends. International Journal of Molecular Science, 21(7), 2311.

- Owen, D. H., Katz, D. F. (1999). A vaginal fluid simulant. Contraception, 59 (2), 91-95.

- Lee, C. H., Wang, Y., Shin, S-C., Chien, Y. W. (2002). Effects of chelating agents on the rheological property of cervical mucus. Contraception, 65(6), 435-440.

- Huang, L., Cao, K., Hu, P., Liu, Y. (2019). Orthogonal experimental preparation of Sanguis Draconis- Polyvinylpyrrolidone microfibers by Electrospinning. Journal of Biomaterials Science Polymer Edition, 30(4), 308-321. [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, A. J. M., Schowen, R. L., Topp. E. M. (2004). Polyvinylpyrrolidone-drug conjugate: synthesis and release mechanism. Journal of Controlled Release, 94(1), 91-100.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).