1. Introduction

Quality of Service (QoS) is a well-known concept that ensures that the parameters and conditions desired by service users are met. For instance, in cloud computing, the QoS refers to the performance, reliability, and availability levels that an application and the underlying platform or infrastructure provide [

1]. QoS targets play a crucial role in decision-making related to cloud system management, capacity allocation, load balancing, and admission control. A service level agreement (SLA) between the service provider and the user typically outlines the services to be delivered and the expected performance metrics. An SLA can also specify how this performance will be measured and the penalties for failing to meet the agreed-upon levels.

In wired communication, such as in telephony, QoS describes various requirements, including response time, the probability of communication interruptions and losses, signal-to-noise ratio, crosstalk, echo, and loudness levels, among others. Recommendations for these QoS aspects can be found in an International Telecommunication Union (ITU) document [

2].

Within communication networks, QoS outlines the essential requirements the network must provide to ensure satisfactory service for users. It can be specified by conditions that must be met for effective communication between a source and a destination [

3]. The requirements for QoS vary across different applications, and specific challenges may arise within large backbone networks, as well as in inter-domain and intra-domain sections (

cf. examples in [

4,

5]), and Local Area Networks.

QoS within wireless Local Area Networks (LANs) is concerned with ensuring optimal network performance following user-defined requirements. Solutions mainly revolve around prioritizing traffic types and allocating resources to accommodate varying transmission needs, such as data, voice, and video. IEEE 802.11e standards, in particular, introduce modifications to the Medium Access Control (MAC) layer by establishing distinct priority levels—referred to as access categories—for effective classification and scheduling of traffic. Through the implementation of Enhanced Distributed Channel Access (EDCA), which utilizes a modified version of the widely utilized Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA) mechanism, high-priority traffic has a significantly increased probability of successful message transmission to the coordinating access point [

6].

Several tools at different layers of the OSI protocol help service providers ensure QoS for users with distinct requirements. Traffic Engineering (TE) manages queues with priorities and various packet-forwarding strategies, typically at the MAC layer.

Our paper focuses on QoS-aware routing, which aims to compute routes that guarantee specific QoS criteria. When multiple quality criteria are involved, QoS routing from a source to a destination leads to the multi-constrained (optimal) path problem (MC(O)P). In this context, the goal is to find a feasible path that meets the QoS constraints. This problem is NP-complete, meaning that the solutions proposed in the literature can be time-consuming, and there is no certainty of finding a solution even if one exists.

The most well-known efficient algorithm for exact resolution is SAMCRA, proposed in [

7]. Another algorithm, TAMCRA [

8], which limits the number of examined paths, performs computations with a finite, small probability of missing a path that satisfies all constraints. This study focuses on QoS routing challenges in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs).

WSNs gather data to transmit to applications requiring specific QoS standards, including bandwidth, delay, jitter, and packet loss. Data must be sent to a sink node, base station, or border router for further processing. Common applications include environmental monitoring, health tracking, and anomaly detection in real-time surveillance and alert systems. Additionally, WSNs may collaborate with control panels in Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs). Wireless Multimedia Sensor Networks (WMSNs) can facilitate new applications in healthcare, traffic monitoring, and CPSs. They allow for the visualization of rich content and support complex tasks such as identification and tracking.

Several tools in different OSI protocol layers help the service providers ensure QoS for various users with distinct requirements. Tools exist in the MAC layer; Traffic Engineering (TE) manages queues with priorities, different packet forwarding strategies, etc. (

cf. in

Section 2). Here, we focus on the QoS-aware routing to compute routes that offer guaranteed end-to-end QoS values. If there are multiple quality criteria, the QoS routing from a source to a destination leads to the multi-constrained (optimal) path problem (MC(O)P). In MCP, a feasible path concerning the QoS constraints is asked. Since this problem is NP-complete, the solutions proposed in the literature are time-consuming, and there is no guarantee of finding a solution even if the problem is feasible.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section enumerates selected, related studies from the large related work.

Section 3 gives our model for the multi-constrained path computation and highlights its main problems. Our propositions are presented in

Section 4. A comparison of the proposed quasi-optimal DODAG computation with two heuristic computations can be found in

Section 5. Conclusions and perspectives close this work.

Table 1.

Key Literature in QoS for WSNs and Related Domains.

Table 1.

Key Literature in QoS for WSNs and Related Domains.

| Reference |

Main Contribution |

Limitations/Gaps |

| Mahadevan et al. [1999] |

Introduced IntServ and DiffServ, foundational QoS architectures for TE. |

IntServ is resource-intensive and non-scalable for WSNs; DiffServ lacks fine-grained control in low-power devices. |

| Cisco [2017] |

Differentiated Services (DiffServ) approach for prioritizing traffic classes to meet QoS requirements. |

Less suited for resource-constrained WSNs; focused on Internet-scale networks. |

| Karakus et al. [2017] |

Provided a detailed overview of SDN architecture for centralized and programmable flow management to enhance QoS. |

Overhead in resource-limited WSNs and latency in centralized SDN designs. |

| Mostafaei et al. [2018] |

Highlighted SD-WSN improvements via OpenFlow for QoS provisioning in resource-constrained environments. |

Design flaws identified in SDN-based WSNs, with high computational overhead. |

| Samridhi et al. [2020] |

Compared SDN-enabled WSNs to conventional WSNs using RPL protocol; identified overhead trade-offs. |

Limited to small-scale testbeds; lacks large-scale experimental results. |

| Chandnani et al. [2023] |

Proposed a hybrid protocol for data aggregation and reactive routing to improve QoS at the network layer. |

Primarily simulation-based; lacks implementation in diverse environments. |

| Lenka et al. [2022] |

Suggested k-means clustering with fuzzy inference-based CH selection for IoT-enabled WSNs to enhance QoS. |

Computational complexity of CH selection in resource-constrained networks. |

| Benelhourri et al. [2023] |

Proposed an evolutionary genetic algorithm for CH selection in hierarchical WSN routing. |

Energy overhead during evolutionary optimization; potential scalability issues. |

| Gantassi et al. [2021] |

Combined K-means clustering with a mobile data collector (MDC) for QoS improvement in large-scale WSNs. |

MDC introduces additional complexity and latency; mobility optimization is not addressed. |

| Ghawy et al. [2022] |

Developed a multi-path protocol using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for traffic fairness and load balancing in WSNs. |

PSO may require high computation time; lacks real-world testing on dynamic WSN topologies. |

| Pundir et al. [2021] |

Systematic review of ML applications in QoS provisioning, offering a comprehensive framework for performance parameter evaluation. |

Few real-world implementations; focus on theoretical aspects of ML in WSNs. |

| Afroz et al. [2021] |

Proposed an energy-efficient MAC protocol using Q-Learning and adaptive modulation for QoS improvement. |

Limited to specific scenarios; may lack scalability in diverse WSN applications. |

| Singh et al. [2024] |

Introduced reinforcement learning for multi-objective QoS optimization in edge-enabled WSN-IoT systems. |

High computational demand for reinforcement learning in real-time settings. |

2. Related Work

Table 2.

Summary of Literature Review on QoS in WSNs and IoT.

Table 2.

Summary of Literature Review on QoS in WSNs and IoT.

| Ref. |

Objectives |

Strength |

Limitations |

| [9] |

Propose IntServ and DiffServ for QoS-aware networking. |

Differentiated Services offer scalable and cost-effective QoS mechanisms. |

IntServ is resource-intensive and not scalable for WSNs. DiffServ is less suited for WSN constraints. |

| [10] |

Overview of SDN concepts and advantages for TE. |

Centralized control and programmability for optimized resource allocation. |

SDN introduces additional overhead and centralized failure risks. |

| [11] |

Hybrid protocol for routing and data aggregation in WSNs. |

Enhances routing efficiency and data collection. |

Not explicitly tested for energy efficiency in large-scale deployments. |

| [12] |

Propose hierarchical routing for IoT using k-means clustering and fuzzy inference. |

Effective cluster head selection and reduced intra-cluster communication. |

May involve high computational costs in CH selection. |

| [13] |

Genetic algorithm for cluster head selection in WSNs. |

Energy-efficient CH selection and routing. |

Fitness function tuning can be computationally intensive. |

| [14] |

QoS optimization in 6G-enabled WSN-IoT using reinforcement learning. |

Pareto-optimal solutions for multiple QoS metrics. |

Complexity of simultaneous multi-objective optimization. |

| [15] |

Systematic review of ML-based QoS techniques in WSNs. |

Comprehensive analysis of QoS parameters and frameworks. |

Focuses on literature review without detailed implementation. |

Traffic Engineering (TE) proposes several tools to help the QoS in networks. Notable examples, for instance, the classification of flows, the class-based or priority-based, policy-based scheduling to handle queues, or the flow rate limitations to avoid congestion (

e.g., flow control in TCP and traffic shaping). For reliable communication, acknowledgment-based solutions exist in TCP and the

mechanism to avoid packet losses. Multi-path routing and duplicating messages using independent routes can improve fault tolerance and reliability. Intserv and Diffserv [

9] are the most known QoS-aware solutions. Integrated Services (IntServ) is based on an individual reservation of resources for each flow using the Resource Reservation Protocol (RSVP). In this architecture, all nodes must implement it and store many states for communications. Hence, this solution is not scalable, needs high resource consumption on the network nodes, and can not be applied in WSNs. Differentiated Services or DiffServ is a more affordable solution to meet the QoS requirements on the Internet. The DiffServ approach operates on the principle of traffic classification, ensuring preferential treatment for higher-priority traffic classes [

16].

The concept of Software Defined Networking (SDN) enables advanced, software-supported mechanisms. According to [

10], SDN is centralized, giving controllers global visibility of the network. It is programmable, separates the data and control planes, and optimizes flow management and resources. QoS provisioning becomes simpler and more practical for network administrators using the OpenFlow standard. In SD-WSNs, the SDN concept proposes the remote configuration of forwarding elements with forwarding rules for data packets of different flows. The computation is centralized in the control plane and can improve the operation of WSN [

17]. The performance of the conventional WSN networks using the RPL protocol and the SD-WSNs are compared in [

18]. The experimental results confirm the expected overhead required in an SD-WSN and indicate some design flaws in an SDN architecture. A review of the TE tools in classic networks and Software Defined Networks can be found in [

19].

Since sensors have limited capacities and energies, resource-intensive solutions of TE can not be applied in WSNs.

In WSNs, sensors may be far from the sink, gateway, and BR, and multi-hop communication is needed with sensors that are often routers as well. Wireless sensors are restricted in energy, bandwidth, computing capacity, and storage. WSNs can be installed in difficult, harsh, or even hostile environments. Sensors can expire, be destroyed, or leave the network. Robustness is needed 1) to cover the area (eventually multiple times) and 2) for communication (to ensure a redundant topology and possible self-repair mechanisms). Therefore, routing is a delicate operation. For QoS in a sensor network, data aggregation and appropriate routing play an important role. The research presented in [

11] introduces a hybrid protocol for data aggregation and routing at the network layer, which enhances both data collection methodologies and the performance of a reactive routing protocol.

One of the most important applications of WSNs is in the Internet of Things (IoT). The authors in [

12] state that intelligent WSN routing is necessary for IoT to improve QoS. A hierarchical organization is proposed: k-means clustering is used, and in each cluster, a Cluster Head (CH) is selected using a fuzzy inference system. The sensors send data packets to its CH, and CH nodes send them to the sink node. To select appropriate CHs, an evolutionary (genetic algorithm) based routing algorithm with a new fitness function is proposed in [

13]. The study in [

20] presents a hybrid protocol that is a combination of the K-means method and mobile data collector (MDC) to improve the QoS of clustering protocols in Large-Scale Wireless Sensor Networks (LSWSNs). The objective is to enhance the election of CH (to reduce energy consumption in CHs). In addition, a mobile data collector is used as an intermediate node between the CH and the BS. For WSN-based IoT applications with a large volume of traffic loads and unfairness in network flow, a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is proposed to develop a multi-path protocol [

21].

The literature contains several propositions using Machine Learning (ML) techniques for QoS. ML is a good technique that improves with training, study, observation, or past data and predicts the outcome or behavior based on the collected data. A systematic review is presented in [

15]. This study also provides a framework for the performance parameters. The QoS parameters are scalability, throughput, energy, latency, packet loss ratio, packet error ratio, reliability, availability, maintainability, bandwidth, jitter, cost, bit error rate, periodicity, priority, deadline, confidentiality, integrity, safety, and security.

In the realm of next-generation 6G-enabled devices, QoS is critical. It ensures exceptional network performance and significantly enhances the end-user experience. A reinforcement learning-enhanced multi-objective optimization for QoS management in edge-enabled WSN-IoT is proposed in [

14]. The concerned objectives, such as energy use, latency, throughput, and coverage, are simultaneously optimized to obtain Pareto-optimal solutions.

2.1. QoS Routing Protocols

Comprehensive surveys have been conducted to review QoS-aware routing protocols for WSNs [

22,

23,

24].

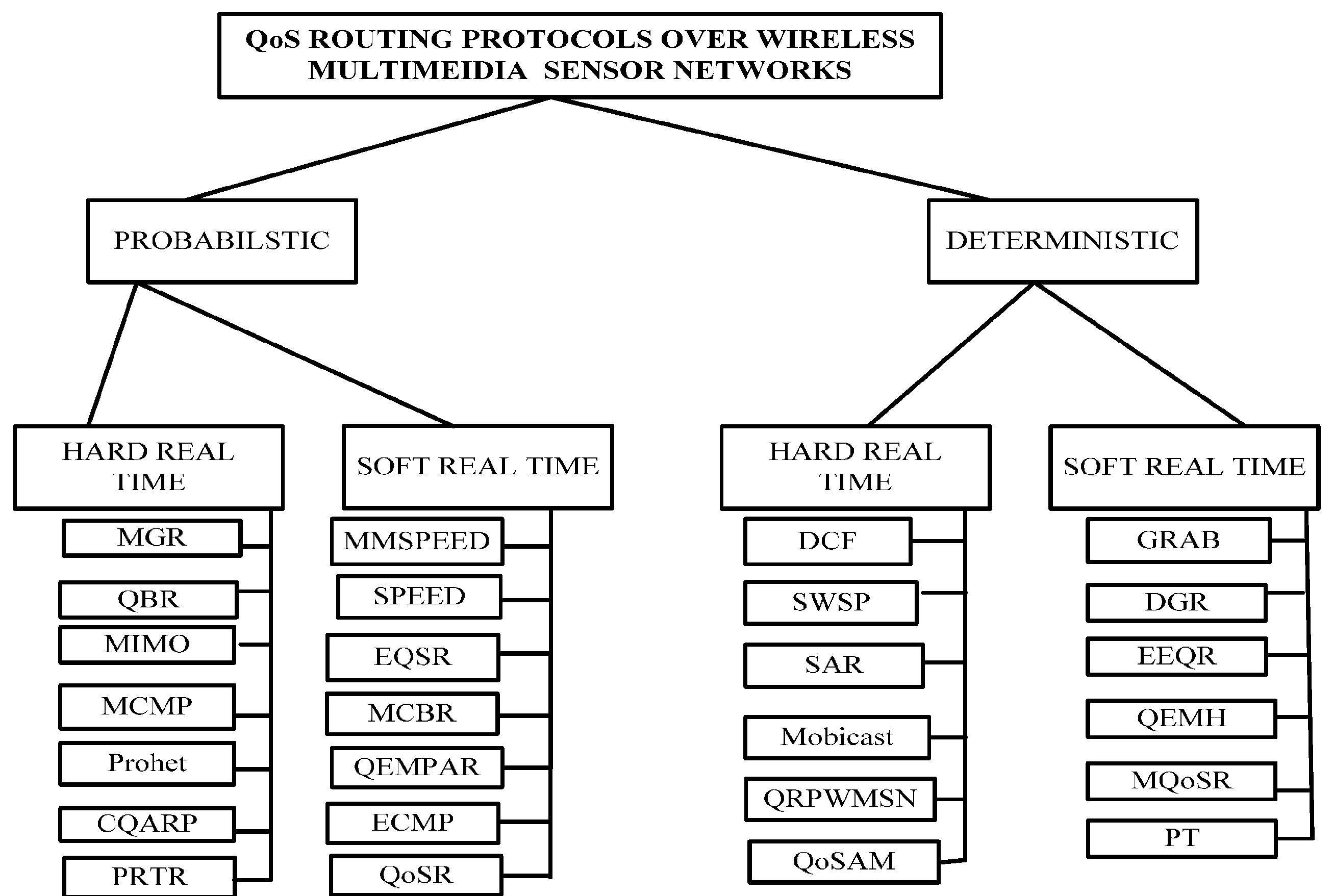

Figure 1 presents a classification of various protocols. This classification distinguishes between hard and soft QoS requirements, as well as probabilistic and deterministic models. Another classification in [

25] categorizes protocols into data-centric, self-organizing, hierarchical, location-aware, network flow, and QoS-aware categories.

QoS requirements are typically based on multiple parameters or metrics. Desired QoS outcomes can be expressed as constraints, indicating that the relevant QoS parameters must fall within specified intervals. A set of these constraints is the most straightforward way to describe QoS. Additionally, objective functions can be formulated to identify the preferred paths.

In [

26], the authors distinguish primary and composite metrics. The combination of multiple primary routing metrics gives a composite one that can lead to the optimization of more than one performance aspect. The proposed combinations are a weighted sum or a lexical combination of primary metrics. This latter needs a clear prioritization of the metrics inspected with strict priority. The paper [

27] specifies simple routing metrics and some combinations to create combined, composite routing metrics. Based on a routing algebra, the authors prove that the routing protocol converges to optimal paths and can be used successfully in the RPL protocol.

RPL is a standard routing protocol that builds a multi-hop, tree-based mesh topology over lossy links. It primarily facilitates the transmission of data from sources or sensors to sinks or Border Routers (BRs). This standard IPv6 routing protocol defines the distributed construction of routes through an objective function (OF), which is responsible for selecting the optimal links for the route map. However, RPL is susceptible to challenges associated with mobility and reliability.

An efficient, adaptive link-quality estimation (LQE) is essential to select the best routing path under time-varying network conditions. A reinforcement learning-based link quality estimation can be found in [

28]. In [

29], for the multi-constrained QoS routing in Low-Power and Lossy Networks (LLNs), using RPL, a new Objective Function (OF) and two heuristic routing algorithms with QoS constraints for LLNs are proposed. The non-linear length can consider any number of metrics and constraints for QoS routing, and it is defined as follows.

Definition 1.

Let and be the vector of K link values in the edge e and the vector of the tolerated K values on the QoS paths. The non-linear length (NL) of a path P is a scalar

2.1.1. Non-Linear Length and RPL Related Protocols in WSNs

The authors in [

30] compute an auxiliary edge weight

for each edge

e with a constant value

W. As indicated in the paper, it is possible to replace this constant by

. One can consider the auxiliary weight as a ”projection” of the non-linear length on the edge. A shortest path calculation is performed using this weight to find the QoS paths.

A method compatible with RPL and based on the non-linear length has been formulated in [

29]. In the DODAG construction, each node is supposed to store the weight vector computed from the sink to this node (the DIO message contains the cumulated weight vector). The node is the preferred parent among the feasible ones, ensuring the node’s minimal non-linear length. The decision is sent to the neighbors. This algorithm connects all nodes in the sub-tree rooted at the node to the root with the same path (which is not always a feasible solution for certain nodes).

[

31] discusses modifications to determine the best paths for all nodes, ideally arriving at an optimal solution. The primary changes involve a mechanism based on deferred decisions. Nodes need sufficient time to gather alternative paths from potential parent and child nodes. This approach ensures that all necessary information is available for making optimal decisions. Note that this solution requires significant computing power and adds important delays before the system’s reaction. Additional changes are also discussed by limiting the number of examined paths by an integer value

k (similarly to the computation in [

8]). The results illustrate that the exact route computation is not recommended with the resources of LLNs.

Key issues related to our topic include the infeasibility of QoS requirements, inadequate formulation, oversimplification, the homogenization of heterogeneous cases, dynamic networks, unstable routes, and severe overload, among others.

Noteworthy solutions to address these issues include traffic classification, prioritization, centralized computation, leveraging fog and edge resources, hierarchical organization, clustering, machine learning techniques, and multi-path routing.

The following section specifies the purpose of our recent investigation on the QoS routing in WSN.

3. Model & Problem Formulation

A graph model represents the network topology to formulate the fundamental routing decision problem.

3.1. Graph Model

We suppose wireless communication. The graph nodes correspond to sensors, relays, actuators, sinks, etc. To simplify, we suppose the sources are sensors, which can also be relays, and the sinks are gateways/Border Routers. Two nodes can directly communicate within each other’s communication range. In large networks, sending messages directly to sinks is impossible, and multi-hop communication is necessary. We suppose symmetric communication links. Under this hypothesis, the topology is represented by an undirected graph (a digraph is in the case of asymmetric links). Positive values of QoS-related metrics are associated with the edges in E. Note that important QoS-related metrics and constraints, such as the remaining energy and the state of the routers, can also be used for routing. However, this study focuses only on the QoS path computation based on link values.

Table 3.

Glossary of Modeling Terms.

Table 3.

Glossary of Modeling Terms.

| Term |

Description |

|

An undirected graph representing the topology (a digraph is in the case of asymmetric links). |

|

The vector of K link values in the edge e. |

|

The vector of the tolerated K values on the QoS paths. |

|

The scalar non-linear length of a path P . |

The most commonly used metrics and their types are mentioned in the RFC6551 [

32]. Metrics can be either aggregated or recorded. The values characterizing a path can be derivative, cumulative values from the link values. In a nutshell, metrics are categorized into

Additive metrics: the value associated with the path is the sum of the link values ( e.g., the delay).

Multiplicative metrics: the path value is the product of the link values (e.g., the probability of the transmission without losses).

Bottleneck-type metrics: the most critical link value characterizes the path. (e.g., the bandwidth).

Our work focuses on aggregated additive metrics. The routing decision aims to find QoS-aware paths (a set of paths) from the sources to the sinks. This objective is formulated mainly in two ways.

3.2. Multi-Objective vs. Multi-Constrained Routing

In the

multi-objective formulation, more than one objective function is established to be optimized simultaneously. For instance, one is to minimize the cost, and the other is to maximize the bandwidth. These objectives can be contradictory; the path that minimizes cost may not be the best for bandwidth, and vice versa. A solution is considered Pareto optimal if no objective can be improved without compromising at least one of the others. There may be several Pareto optimal solutions for a given problem. Readers can find related routing analyses in [

33] and examples in [

34]. Additionally, multiple metrics can be combined into a composite metric, allowing multi-objective research to be reformulated as a single-objective optimization problem.

Multi-constrained routing is a key driver to support QoS for real-time multimedia applications in wireless mesh networks (WMNs) [

34]. The model corresponds to the well-known multi-constrained path problem (MCP). The objective of MCP is to find a feasible (or, in some cases, optimal) path concerning a set of QoS constraints. Since this problem is NP-complete, the solutions proposed in the literature are either time-consuming or do not guarantee finding a solution, even if the problem is feasible. Some of the most efficient algorithms are the mentioned SAMCRA and TAMCRA algorithms. Examples of routing protocols can be found, for instance, in [

29,

35].

The paper by Shin et al. [

34] is notable for proposing a multi-constrained routing protocol that identifies problematic links responsible for QoS degradation and replaces them with an alternative path through a local repair mechanism. Multiple objectives and constraints can be integrated to delineate the goals of the routing process [

36].

3.3. Targeted Challenges

We are focusing on the problem of the multi-constrained routing from sensors to sinks/BRs. Since the RPL protocol is a standard, our investigation is mainly concerned with this protocol. RPL constructs a strict, tree-like, destination-oriented, directed acyclic graph for routing. The set of paths from the sensors to the sink/BR comprises a directed incast route. It is known that, under multiple QoS constraints, it is not always a directed tree [

29].

Challenge 1: A unique DODAG can not satisfy the QoS from all sensors.

A single DODAG may not always be sufficient for multi-constrained QoS routing in a given WSN and QoS requirement.

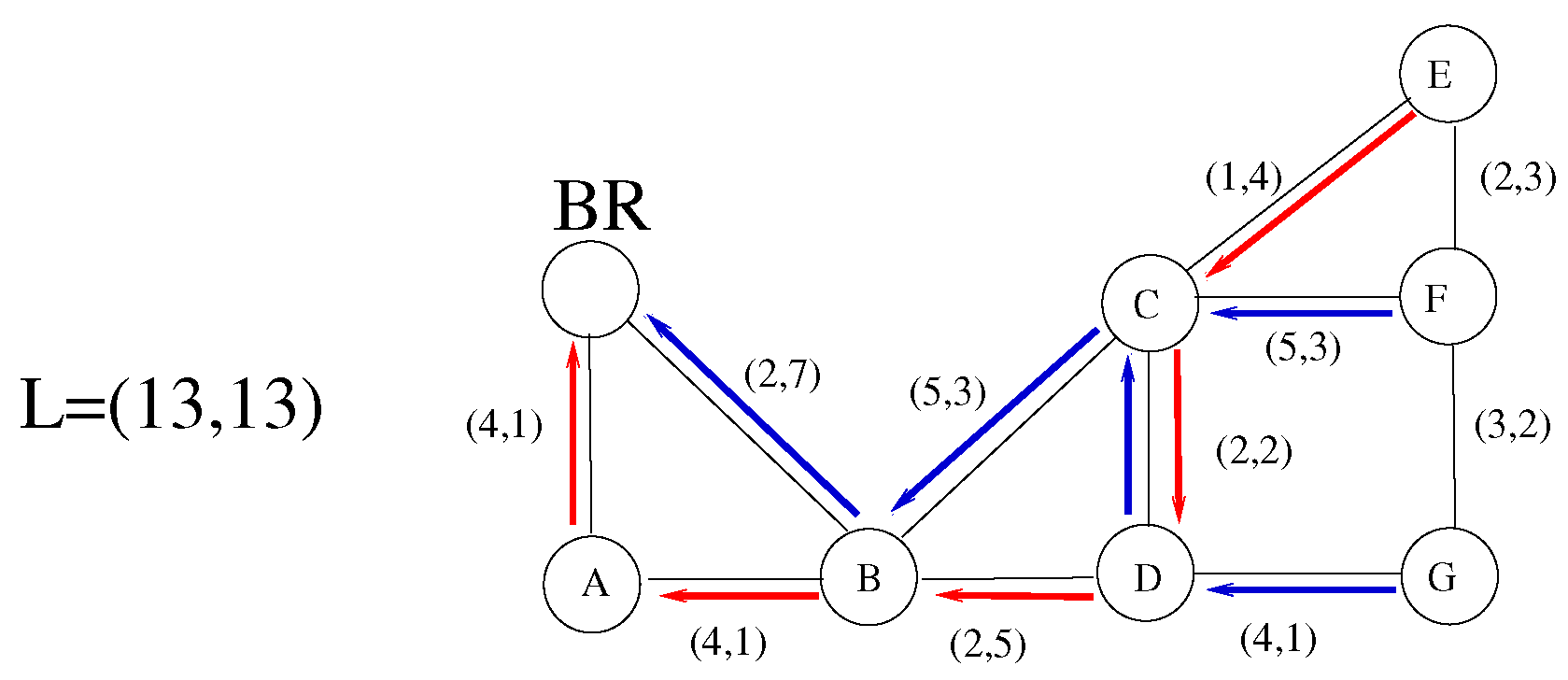

Figure 2 illustrates that a DODAG can not work for all nodes, even in a small domain. Suppose we have two additive QoS parameters (

e.g., delay, cost). The maximal tolerated values (the QoS limits at BR) are

, and the link values are indicated in the figure. Only the indicated blue and red QoS paths from nodes E, F, and G to BR can be used. There is no single QoS-compatible DODAG from these nodes to the BR. Nodes B, C, and D are in both QoS paths; they can use the blue or red path to send messages to the BR. Conversely, the routing decision for messages coming from children is not simple at these nodes. For instance, at node C, messages from node E must be outed to node D, but messages from F must be transmitted to B.

Challenge 2. Paths from sensors far from the BR may not meet QoS demands.

Let

represent the vector of the QoS requirements in the network shown in

Figure 2. None of the routes from nodes E, F, and G to the BR fulfill this QoS requirement. Routes from nodes E, F, and G to the BR satisfy this QoS requirement.

Challenge 3: The optimal DODAG under QoS constraints is NP-hard.

Assuming that distances are calculated using a non-linear length function based on multiple additive metrics, the DODAG can be viewed as a minimum cost diameter-constrained arborescence directed from its non-root nodes (sources) to the root node (BR). The undirected version of this problem, which involves only one additive hop distance, is known to be NP-hard [

37]. Furthermore, the minimum cost r-arborescence problem, where

r refers to the root node, is also NP-hard [

38]. We conjecture that the problem of directed diameter-constrained r-arborescence using non-linear weights is also NP-hard.

4. Propositions

Recognizing that RPL is the standard routing protocol for LLN, this study aims to enhance its applicability in challenging QoS routing conditions through targeted modifications. One viable solution to mitigate the challenges associated with device limitations in WSNs is to offload tasks to external devices. This approach not only optimizes performance but also extends the network’s capabilities.

4.1. Architecture for Offloaded Route Computation

While cloud resources are frequently utilized in various applications, their physical distance from WSN devices can result in unacceptable latency for applications that require stringent QoS. The issues inherent in cloud computing are emphasized in [

39]. Data centers often struggle to accommodate the rapid growth of extensive data volumes.

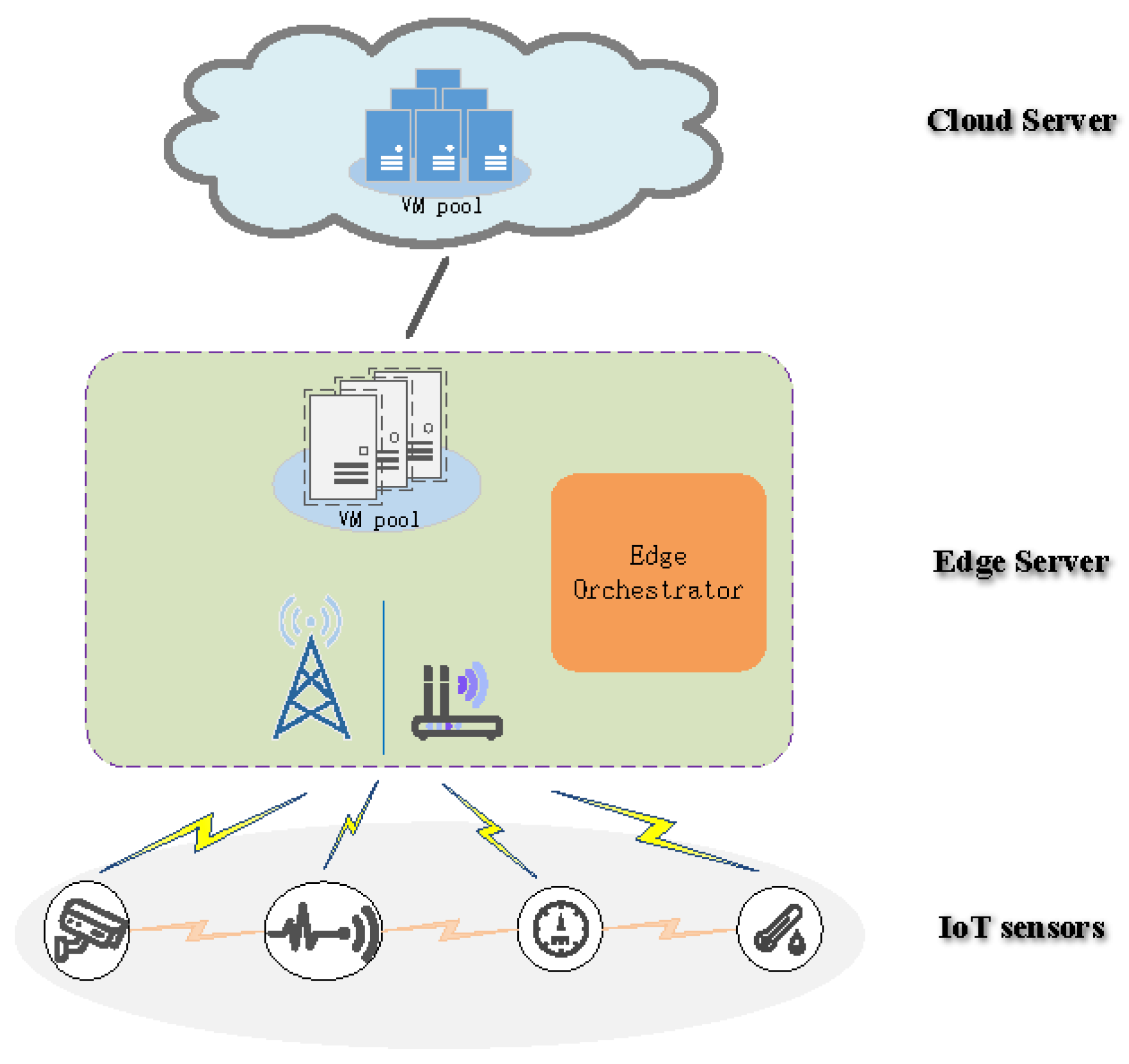

The computational load at the data centers is reduced by solving problems locally, following the Fog and Edge Computing technique, which can also provide a distributed, reduced computational load at the data center networks. Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) is a promise for offloading tasks with stringent delay requirements and computing at the edge of networking technology.

Figure 3 depicts a potential global architecture for this model. MEC seeks to leverage the physical proximity to end devices, thereby minimizing latency, ensuring efficient network operations, and enhancing the overall user experience.

A review paper [

41] presents the research status of task offloading in WSN in an edge computing environment. As indicated in [

42], computation offloading using MEC can help notably the tasks of smart and mobile nodes. It can significantly improve the performance of WSN, taking the functions of computation and based on energy and storage services of edge servers.

The deployment of Edge Computing produces new challenges. Since the applied architectures and task offloading strategies can impact the applications’ performance differently, finding good parameters for scheduling the offloaded tasks on the edge-cloud system is a challenging optimization [

43,

44]. Energy-efficient computation offloading decisions are also challenges. In [

40], a cloud-assisted edge computing framework in an IoT environment is presented. A comparison of Fog Computing, Cloudlet, and Mobile Edge Computing implementations can be found in [

45].

4.2. Centralized Route Computation, Protocol CeRPL

Since the computation of QoS-aware paths can be expensive and an important quantity of paths may exist, the distributed computation of the DODAG by the small elements is difficult, and feasible paths can be lost with the local parent selections. Moreover, in the case of conflicts (

e.g., when paths from different children need different parents,

cf. the example illustrated in

Figure 2), a broad overview of the domain can be useful.

Offloading the computation of a good (possibly optimal) DODAG or a good set of DODAGs satisfying the QoS requirement between the BR and the source nodes is a promising solution. The functioning and computation separation is founded on the following elements.

QoS aware route computation based on the topology graph and the QOS requirement.

Configuration/reconfiguration of the network.

Monitoring of the network, advertisement of changes.

Functioning, data gathering using the classic mechanism of RPL.

4.2.1. Route Computation

Since the optimal DODAG computation is NP-hard, the computation targets a ”good” solution. The offloaded computation has three steps:

Computation of paths corresponding to the QoS requirement,

Construction of DODAG(s) from the paths.

Adding redundancies to ensure robustness.

Conceptually, the following categories of paths are distinguished:

feasible paths, those that correspond to the end-to-end constraints,

dominated paths, those that are dominated (in the sense of Pareto), and

ready paths, those that can not have feasible successors by adding adjacent edges.

Corresponding to the first step, Algorithm 1 in the Appendix describes the centralized computation of the QoS-aware paths in the reverse direction: from the sink/BR to the sources. The direction of the paths is changed at the end of the computation.

The algorithm stores in an array the feasible paths from the BR to the nodes The element contains the paths for the noden. Initially, a fictive, zero-weighted path is created for the BR. It is marked as not ready. Then, a loop ”while” iterates over the nodes and the paths to the nodes. If a path is not ready, its successor paths are created. If a successor path is feasible, it is stored for its ”destination” node. It is indicated as a dominated path if another path at the last node dominates the new path. A new path is always stored as a ”not ready” path (its possible successors must be analyzed later). Not feasible paths are not stored. After the evaluation of its successors, a path becomes ”ready” to avoid useless future assessment. A faster version of the computation can be obtained by restricting it to store only the non-dominated paths instead of all feasible paths. In this case, the dominated paths are not marked but deleted (Lines 28-29).

Based on the set of feasible paths, the second step concerns the construction of the DODAGs. First, a first arborescence is built. The optimal DODAG (or the set of DODAGs) is difficult to compute; all feasible path combinations must be examined. To avoid this, a greedy algorithm is applied (cf. Algorithm 2). The set of stored paths of the nodes is examined, and the paths are examined in increasing order of minimal non-linear lengths. If there is no conflict between the DODAG under construction and the candidate path, the path is added to the DODAG.

The conflict is detected as follows:

a) A common prefix of the path and the DODAG is computed starting from the BR. Let be the last node of this prefix (if there is no common prefix, ).

b) The second part from of the new path is analyzed. There is a conflict if there is a common node with the DODAG.

If no conflict is detected, the path is added to the DODAG. The result is an acyclic graph directed from the BR to the leaves. For RPL, the direction of the arcs is reversed.

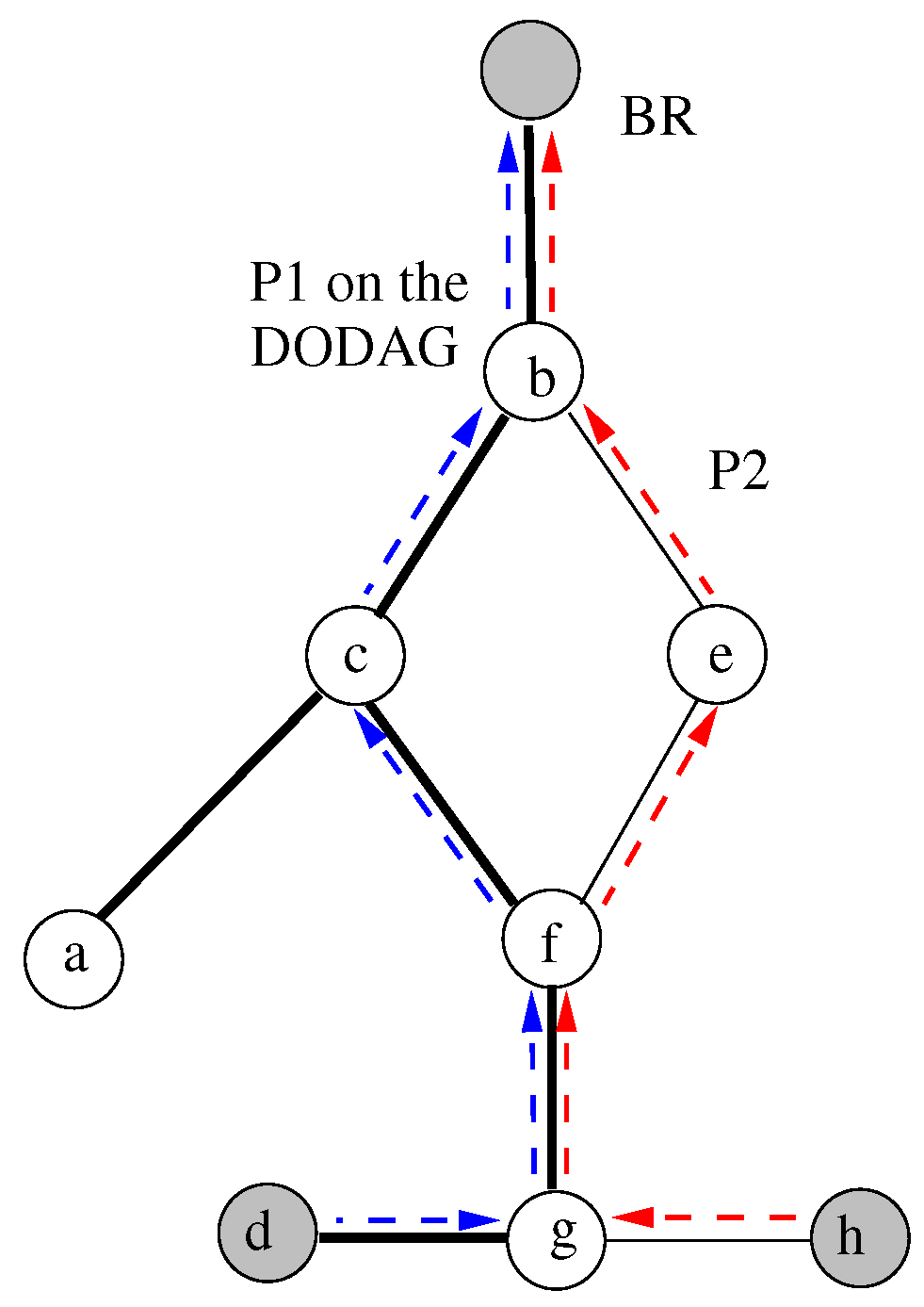

A conflict is illustrated in

Figure 4. Adding the path

to the existing DODAG makes the routing decision impossible at the node

f. To satisfy the QoS constraint, the parent node on the path from

d to the BR is

c, and from

h, the parent is the node

e. The indicated paths can not belong to the same DODAG. If the computed DODAG does not cover all nodes having a feasible path in the domain, new DODAG(s) must be constructed using the same algorithm but based only on the node’s feasible paths.

In the next part of the construction, redundancies are added to the trees to help the local repair mechanism while operating the routing. Paths from the leaves up to the BR are examined to search for alternative parents. Let a be a node on the examined path with rank k (the node’s rank is its hop distance from the BR). Let be the vector containing the maximal link values from the leaves in the sub-tree rooted in a. Let b an adjacent node of a on a path different from the path of a with a rank at most k. Let and be the vector of QoS metrics on the arc and on the path from b to the respectively. Suppose that gives the end-to-end QoS requirement. If , then the arc can be added to the DODAG as an arc going to an alternative parent node (to the node b). The computation is given by the pseudo-code of Algorithm 3.

4.2.2. Configuration of the Network

The network must be (re)configured initially or later when modifications occur and a new set of DODAGs is available. The reconfiguration must delete some old connections and set up the new ones. A good reconfiguration process should not interrupt the existing communications to the BR, and it should be as fast as possible. Some studies can be found on the reconfiguration process for paths and trees (multicast trees in optical networks) [

46,

47].

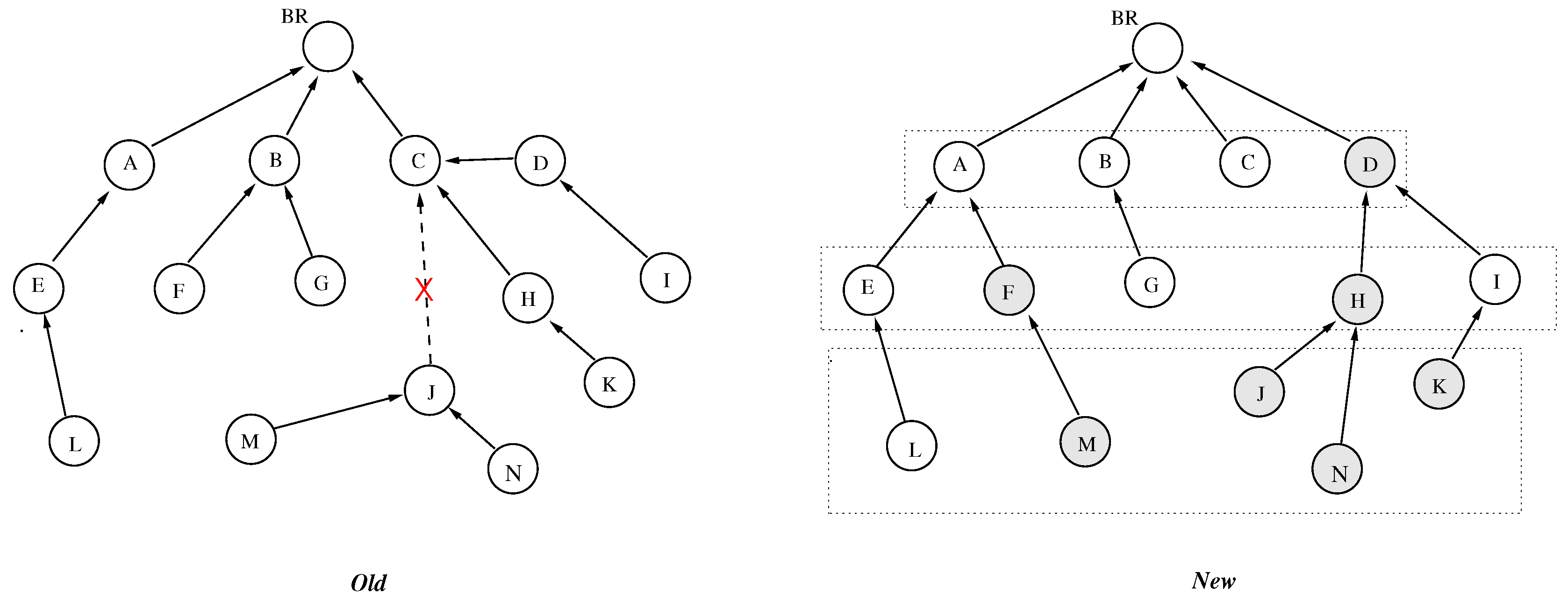

The reconfiguration generally follows a schedule. A subset of (independent) nodes can be reconfigured at each step. The list of nodes to be reconfigured (gray nodes in

Figure 5) is given. In the complementary node-set, the nodes have the same parent configuration in the two DODAGs. A particularity of the DODAGs is that the new configuration setup simultaneously removes the old one. The existing traffic will not be interrupted while the new connection is established.

The edge servers calculate the new DODAG. We suppose that this DODAG contains a feasible path to each covered node. The old version is also available on the server if it is a reconfiguration.

Figure 5 shows the two (

and

) topologies. Let the reconfiguration be considered. As the figure indicates, a subset of nodes must be reconfigured, while others can keep their old configuration. (The first configuration is a particular case; all nodes must be changed.)

A greedy, priority-based, and downstream reconfiguration is proposed. The procedure starts from the BR, configuring the nodes to be modified rank par rank. First, the nodes without parents must be configured. This downstream method does not interrupt the sending of messages to the BR: at each step, a path is established between the nodes in the DODAG and the BR.

4.2.3. Monitoring of the Network

The WSN must guarantee operation without interruptions and meet the QoS requirements for QoS-aware applications. If there are topology changes (due to mobility, disappearance of nodes, or important changes of QoS link values), advertisements for the edge servers are needed. If a local repair can correct the problem, no intervention is needed from the servers. The changes are indicated thanks to monitoring. Since the availability of the nodes and the quality of the communications (the link values) should be controlled, active monitoring is applied [

48]. To balance the power load of monitors, an alternated and scheduled set of active monitors is applied [

49]. The measured values are sent to the BR (and edge servers) using a dedicated simple DODAG.

4.2.4. Functioning

When the RPL Instances and DODAGs are configured, the network works as a 6LowPAN network and the data gathering and sent to the BR correspond to the normal functioning of RPL.

Note that the protocol is suitable for applications where finding multiple feasible paths is important (e.g., networks where fault tolerance or alternative paths are needed).

5. Experimental Analysis of Algorithms

We tested three solutions: the offloaded computation of the quasi-exact solution described in the previous sections (indicated as

in the following) and two constructions based on different objective functions: the auxiliary weight-based construction of a DODAG [

30] (indicated as heuristic

), and the construction using the non-linear length of the paths to parent nodes [

29] (indicated as

in the following). The two DODAG constructions were realized in parallel with the offloaded computation (by simulating the cooperation of nodes and not in a network simulator).

For the objective function of , we assumed that the auxiliary weights could be used as a simple additive metric, and a shortest path tree rooted at the BR was computed. For , we assumed that all cumulative non-linear lengths at the potential parent nodes are available, and the parent with the minimal non-linear length is selected for each node. The WSN topology was generated as follows:

the coordinates of the nodes have been generated randomly inside a square

the links between the nodes within each other’s communication range have been created, and k independent random link values have been associated with each link.

For the algorithms, we used C++ and the Leda library [

50].

5.1. Parameter Settings

Some parameters of the topology were variable: the dimension of the square, the number of nodes inside the square, the number and the position of the BRs, and the communication range of the nodes (we supposed homogeneous ranges).

The number of links in the graphs was not deterministic since the node’s positions were generated randomly. Moreover, we generated k uncorrelated random link values from an interval , and a tolerated maximal QoS value L was also defined for each computation. In each experiment presented hereafter, we indicate the varied values.

5.2. Runs & Results

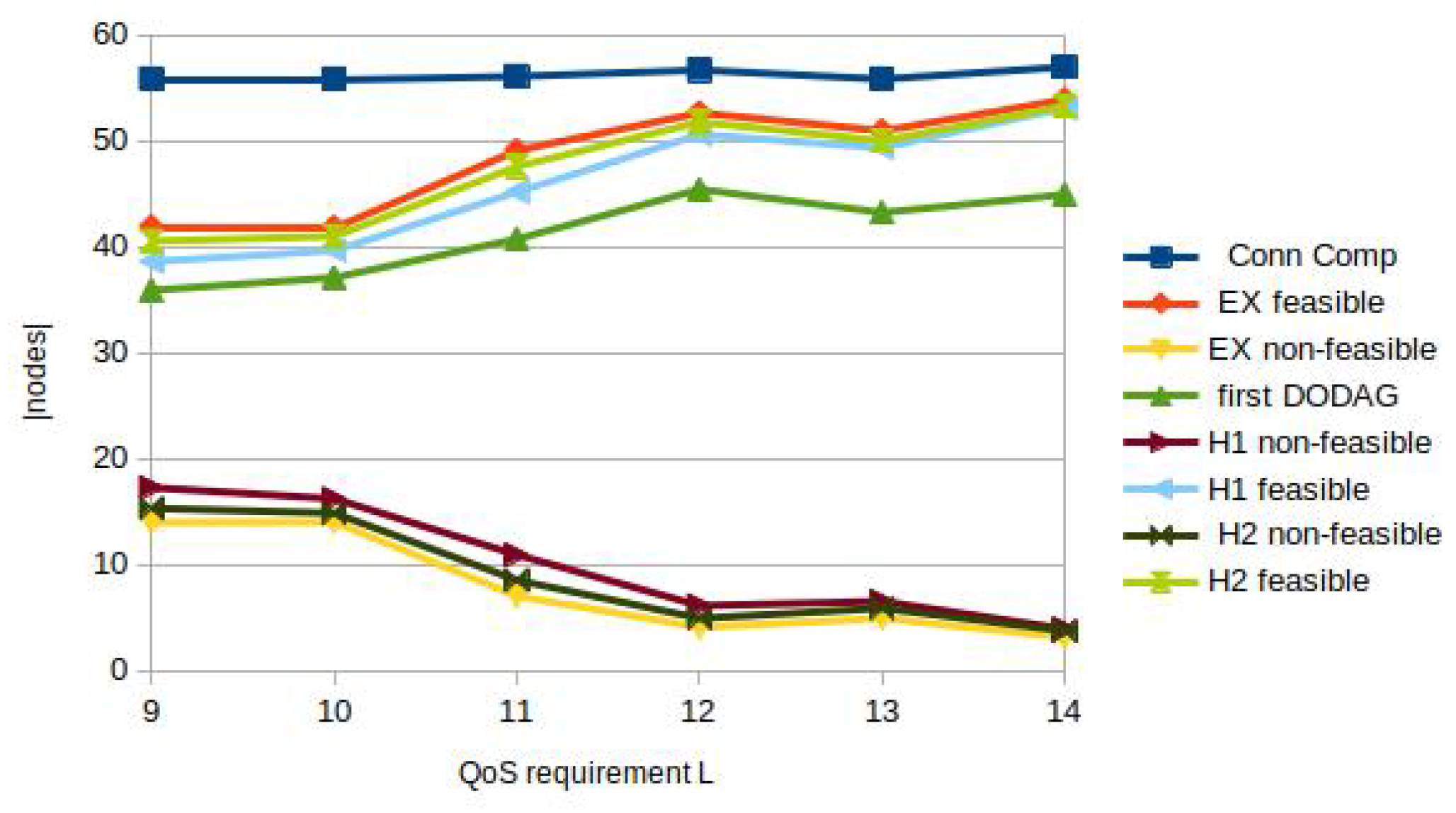

5.2.1. Effect of the Harshness

In the first case, we examined the results of the three DODAG computations regarding the harshness

L. The WSNs were placed inside a square of 100 * 100, and the communication range of nodes was 20. The random topologies were generated with 60 nodes (including a fixed BR in the center of the network). All link parameters were set using the uniform distribution from the interval

. The QoS requirement

L varied from 9 to 14. For each configuration, the computations were performed 20 times. The results in

Table 4 and

Table 5 are average values of 20 runs. The tables illustrate the loss of QoS-aware sensors using the greedy heuristic algorithms compared to the exact solution. The spanning trees (the DODAGs) computed by the greedy algorithms cover all accessible sensors, but some sensors can not meet the QoS requirement. It is also shown by the maximal non-linear lengths, which can be important for these sensors. The best paths can not always be grouped into one DODAG, probably because paths cross (

cf. Figure 4). Note that in the offloaded exact computation, further DODAGs can be computed, and all ”feasible” nodes can be covered. The table indicates only the number of nodes covered by the first DODAG.

Figure 6.

Number of feasible / non-feasible source nodes with different QoS requirements L.

Figure 6.

Number of feasible / non-feasible source nodes with different QoS requirements L.

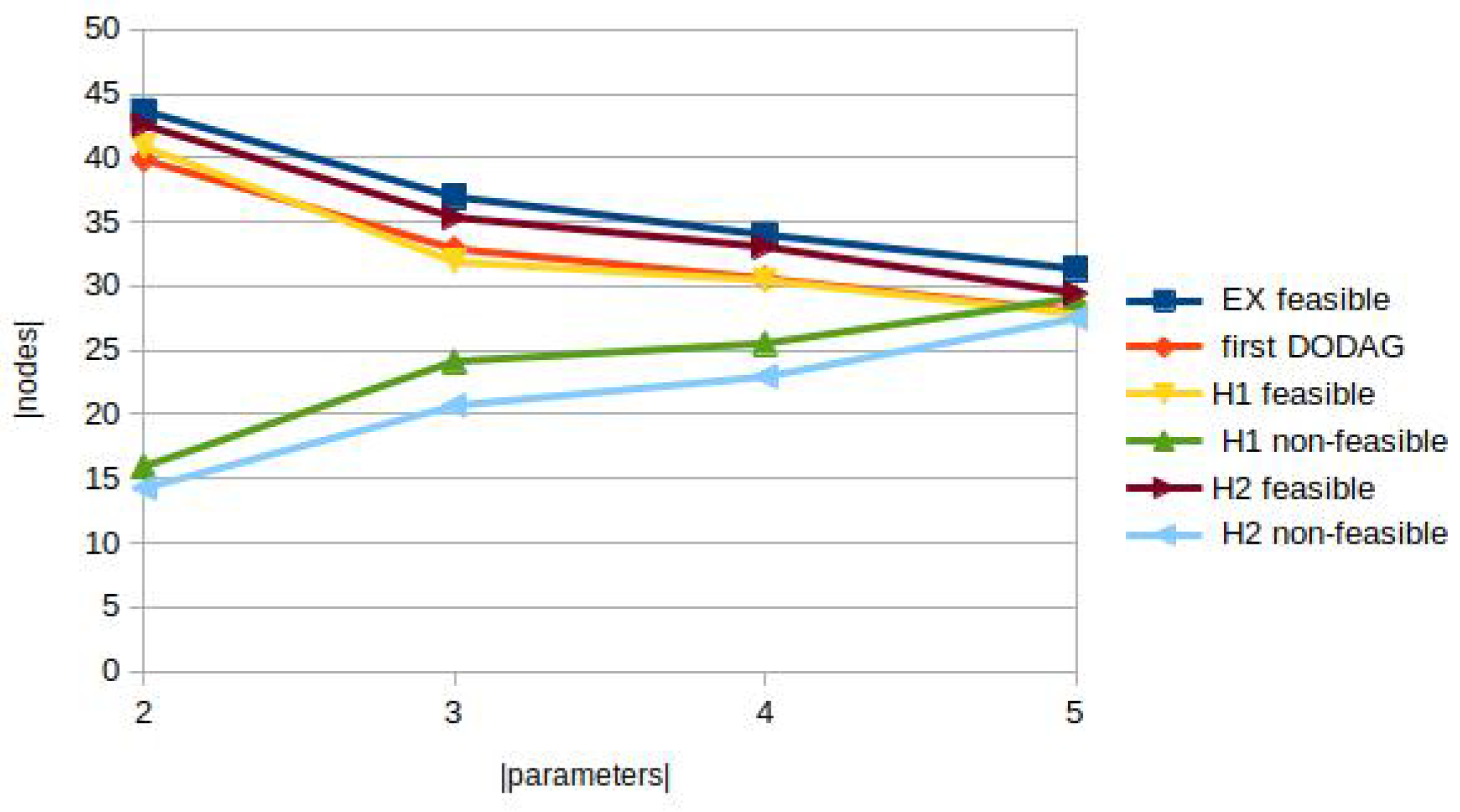

5.2.2. Effect of the Number of QoS Parameters

In this paragraph, the number of the additive link parameters was varied. As in the previous case, 60 nodes with a communication range of 20 were randomly placed inside a 100 * 100 square. The existing links were associated with 2,3,4, and 5 uncorrelated values. Each value was randomly generated from the interval

, and the QoS requirement

L for the paths was equal to 10. The results in

Table 6 are also averages of 20 runs. The first part of the table indicates the average number of feasible and dominated paths during the computation. The second part shows the performance of the three algorithms.

Following the results in

Table 6, the number of uncorrelated QoS parameters influences the number of feasible solutions. Increasing this number from 2 to 5 shows that the number of overall feasible paths decreases. In parallel, we can observe from

Table 7 that the non-linear lengths from the source to the BR increase by increasing the number of parameters. That is, there are fewer and fewer paths that can satisfy the QoS constraints simultaneously by increasing the number of constraints.

Figure 7.

Number of feasible / non-feasible nodes depending on the number of QoS parameters.

Figure 7.

Number of feasible / non-feasible nodes depending on the number of QoS parameters.

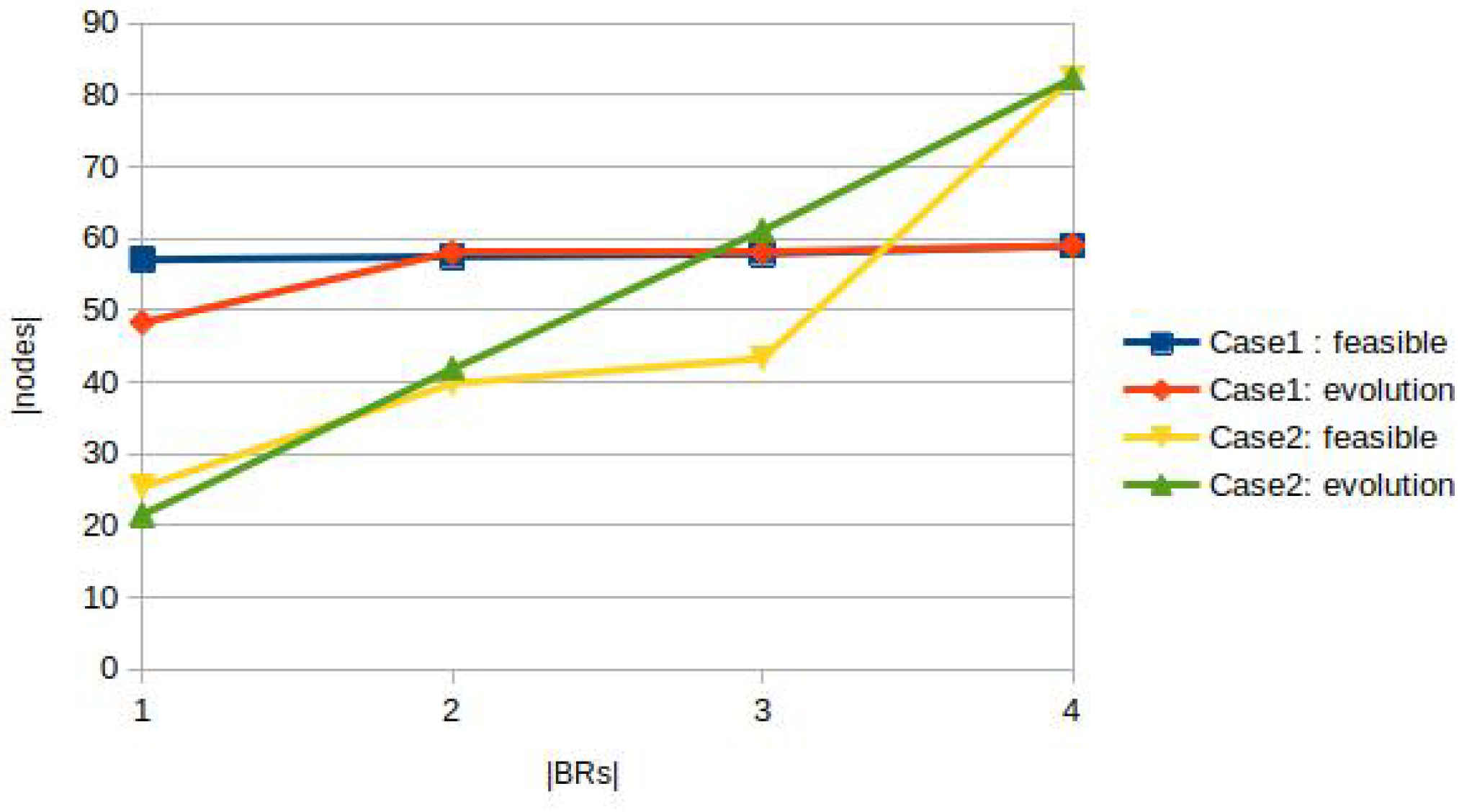

5.2.3. Effect of the Number & Placement of BRs

If there are multiple BRs, the data satisfying the defined QoS requirement can be collected from a larger set of sources (sensors). The QoS-aware paths can cover more sensors. If the BRs are placed carefully, the number of sources covered by QoS-aware paths linked to at least one BR can be considerably increased. Careful sizing of data collection involves a thorough analysis of the network geometry (the number and placement of sensors, communication ranges, and existing links). Based on these elements and the QoS requirement, the number and position of the BRs needed can be determined. Methods such as the well-known K-means and/or the distance-based decomposition of Voronoï can be useful. In our work, we limited the analysis to two simple cases. In all cases, the dimension of the observed square was 100* 100. In the first case, 60 sensors with a communication range of 25 were installed. The nodes were highly connected, the first column in

Table 8 indicates that the number of sensors not connected to the (first) BR can be neglected. There are approximately 50 feasible nodes with only one BR, and the number can reach 57-59 (on 59 nodes) with multiple BRs. Since there are several feasible nodes with only one BR, the improvement by applying further BRs is slight. The right part of

Table 8 illustrates the cases where four BRs were added successively to the same network. This part indicates the detailed progression corresponding to the last line in the left part of the table. The second experiment concerned 120 nodes with a small communication range (12 here). As the results indicate, an important set of nodes is not connected to the first BR. First, only 20 - 25 nodes are feasible on 120 nodes. Using 2 to 4 BRs, the number of feasible nodes and the number of nodes in the first DODAG computed by the offloaded algorithm increase considerably.

Figure 8.

The effect of the number of BRs depends also on the QoS requirement.

Figure 8.

The effect of the number of BRs depends also on the QoS requirement.

6. Conclusions & Perspectives

Since computing QoS paths matching several constraints is hard for small devices, offloading from sensors executing RPL to edge servers is a solution. Even though the calculations are generally difficult, they are feasible in the edge servers for several hundred nodes. If the QoS requirement is relatively low and/or the density of the nodes is high, the number of feasible paths is high. Limiting the number of feasible/dominated paths can accelerate the computation of a near-optimal DODAG.

Tests comparing three DODAG computations show that combined-length-based and classic DODAG constructions can introduce loss of feasible QoS paths. Quasi-optimal computation can lead to path crossings (which is impossible with a simple DODAG in RPL). To solve the conflicted routing problem in the cases of path crossing, multiple DODAGs must be used.

The tests also indicate that dimensioning a WSN under QoS agreement is a careful task. The topological data, the density of the nodes, the intensity of the interference, etc., need prudent analysis. The performance of the network can be improved, the asked QoS can be ensured by increasing the number of equitably placed BRs. The offloaded computation can also solve the dimensioning and the calculation of good sensor clusters when multiple BRs are available.

Future investigations can improve the offloaded computation.

If the number of feasible and/or non-dominated paths is important, a k-limited, TAMCRA-like computation can alleviate and accelerate the DODAG computation. Future analysis is needed to decide when the alleviation is needed (e.g., by finding a threshold).

The optimal DODAG computation based on the optimal paths is an NP-hard task. Further investigations are needed to find good heuristics.

For the reconfiguration of large networks a fast method is needed to schedule the changes without losing communications.

Appendix A

|

Algorithm 1 Computation of the QoS aware paths |

Require: h The topology graph , with the coordinates of the nodes , and a vector of QoS values of edges

-

Ensure: An array P of sets of feasible paths from the to each node

- 1:

global variables - 2:

, bool

- 3:

n, v, w, node

- 4:

e, edge

- 5:

, , Path

- 6:

, array of set of Paths

- 7:

for alldo

- 8:

- 9:

end for - 10:

create a fictive path with the single node

- 11:

- 12:

false - 13:

whiledo▹ While there are not yet evaluated paths - 14:

true - 15:

for all do

- 16:

set of edges

- 17:

for all path do

- 18:

if then

- 19:

break - 20:

end if

- 21:

for all edge do

- 22:

- 23:

▹ a new path - 24:

if then

- 25:

if then

- 26:

;; mark as dominated - 27:

end if

- 28:

- 29:

▹ mark paths dominated by

- 30:

false - 31:

end if

- 32:

end for

- 33:

- 34:

end for

- 35:

end for

- 36:

end while

return

P

|

|

Algorithm 2 Computation of the DODAG(s) |

Require: The topology graph , the array P of set of QoS paths per nodes -

Ensure: A set of DODAGs

global variables

a, n node

node set

, , Path

D graph▹ DODAG: a directed graph

set of graphs▹ The resulted DODAGs

for all do▹ For the nodes covered in P

end for

▹

while

do

▹ A new empty DODAG for all do

if then

while do

▹ the path with minimal non-linear length

▹ The part of after

▹ crosses D in a

if ∄a then▹ There is no conflict

end if

end while

end if

end for

end while return

|

|

Algorithm 3:Add redundancies to a DODAG |

Require: The topology graph , a DODAG

-

Ensure: The modified DODAG D

global variables

a, b node

node set

for all do▹ For the nodes covered by D

for all do

if then

end if

end for

end for return

D

|

References

- Ardagna, D.; Casale, G.; Ciavotta, M.; Pérez, J.F.; Wang, W. Quality-of-service in cloud computing: modeling techniques and their applications. Journal of Internet Services and Applications 2014, 5. doi:10.1186/s13174-014-0011-3. [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union . E.800 : Definitions of terms related to quality of service; Recommendation E.800 (09/08). https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-E.800-200809-I/en, 2008. Online; accessed 25 September 2024.

- Crawley, E.; Nair, R.; Rajagopalan, B.; Sandick, H. A Framework for QoS-based Routing in the Internet. RFC 2386, Internet Engineering Task Force, 1998.

- Howarth, M.; Flegkas, P.; Pavlou, G.; Wang, N.; Trimintzios, P.; Griffin, D.; Griem, J.; Boucadair, M.; Morand, P.; Asgari, A.; Georgatsos, P. Provisioning for interdomain quality of service: the MESCAL approach. IEEE Communications Magazine 2005, 43, 129–137. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2005.1452841. [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, G.; Guerin, R.; Kamat, S.; Orda, A.; Tripathi, S. Intradomain QoS routing in IP networks: a feasibility and cost/benefit analysis. IEEE Network 1999, 13, 42–54. doi:10.1109/65.793691. [CrossRef]

- Mangold, S.; Choi, S.; Hiertz, G.R.; Klein, O.; Walke, B. Analysis of IEEE 802.11 e for QoS support in wireless LANs. IEEE wireless communications 2003, 10, 40–50.

- Mieghem, P.V.; Kuipers, F.A. Concepts of exact QoS routing algorithms. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2004, 12, 851–864.

- De Neve, H.; Van Mieghem, P. TAMCRA: a tunable accuracy multiple constraints routing algorithm. Comput. Commun. 2000, 23, 667–679. doi:10.1016/S0140-3664(99)00225-X. [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, I.; Sivalingam, K. Quality of Service architectures for wireless networks: IntServ and DiffServ models. Proceedings Fourth International Symposium on Parallel Architectures, Algorithms, and Networks (I-SPAN’99), 1999, pp. 420–425. doi:10.1109/ISPAN.1999.778974. [CrossRef]

- Karakus, M.; Durresi, A. Quality of Service (QoS) in Software Defined Networking (SDN): A survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 80, 200–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2016.12.019. [CrossRef]

- Chandnani, N.; Khairnar, C.N. Quality of Service (QoS) Enhancement of IoT WSNs Using an Efficient Hybrid Protocol for Data Aggregation and Routing. SN Computer Science 2023, 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-02165-6. [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.; Pradhan, S.K.; Nanda, A. Quality of Service (QoS) Enhancement of IoT based Wireless Sensor Network Using Fuzzy Best First Search Approach. 2022 International Conference on Intelligent Controller and Computing for Smart Power (ICICCSP), 2022, pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICICCSP53532.2022.9862411. [CrossRef]

- Benelhouri, A.; Idrissi-Saba, H.; Antari, J. An evolutionary routing protocol for load balancing and QoS enhancement in IoT enabled heterogeneous WSNs. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2023, 124, 102729. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2023.102729. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Kumar, N.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Dhiman, G.; Viriyasitavat, W.; Sapsomboon, A. Next-Gen WSN Enabled IoT for Consumer Electronics in Smart City: Elevating Quality of Service Through Reinforcement Learning-Enhanced Multi-Objective Strategies. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2024, Early Access, 1–1. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3446988. [CrossRef]

- Pundir, M.; Sandhu, J.K. A Systematic Review of Quality of Service in Wireless Sensor Networks using Machine Learning: Recent Trend and Future Vision. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 188, 103084. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103084. [CrossRef]

- The Cisco Learning Network. QoS architecture models: IntServ vs DiffServ. https://learningnetwork.cisco.com/message/650042#650042, 2017. Online; accessed 22 June 2019.

- Mostafaei, H.; Menth, M. Software-defined wireless sensor networks: A survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2018, 119, 42–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2018.06.016. [CrossRef]

- Samridhi, S.; Liscano, R. Performance comparison of a Software Defined and Wireless Sensor Network. 2020 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), 2020, pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ISNCC49221.2020.9297181. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.R.; Guleria, A.; Devi, M.S. Traffic Engineering in Software Defined Networks: A Survey. Journal of Telecommunications and Information Technology 2016, 4, 3 – 14.

- Gantassi, R.; Gouissem, B.B.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; el Khediri, S.; Hasnaoui, S. Optimizing Quality of Service of Clustering Protocols in Large-Scale Wireless Sensor Networks with Mobile Data Collector and Machine Learning. Secur. Commun. Networks 2021, 2021, 5531185:1–5531185:12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5531185. [CrossRef]

- Ghawy, M.Z.; Amran, G.A.; AlSalman, H.; Ghaleb, E.; Khan, J.; AL-Bakhrani, A.A.; Alziadi, A.M.; Ali, A.; Ullah, S.S.; Li, X. An Effective Wireless Sensor Network Routing Protocol Based on Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm 2022. 2022. doi:10.1155/2022/8455065. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.; Elleithy, K. Real-Time QoS Routing Protocols in Wireless Multimedia Sensor Networks: Study and Analysis. Sensors 2015, 15, 22209–22233. doi:10.3390/s150922209. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Khan, S.; Ahmad, R.; Sohail, M.; Singh, D. Quality of Service of Routing Protocols in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Review. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 1846–1871. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2654356. [CrossRef]

- Agarkhed, J.; Dattatraya, P.Y.; Patil, S.R. Performance Evaluation of QoS-Aware Routing Protocols in Wireless Sensor Networks. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Informatics; Satapathy, S.C.; Prasad, V.K.; Rani, B.P.; Udgata, S.K.; Raju, K.S., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp. 559–569.

- Chandel, A.; Chouhan, V.S.; Sharma, S. A Survey on Routing Protocols for Wireless Sensor Networks. Advances in Information Communication Technology and Computing; Goar, V.; Kuri, M.; Kumar, R.; Senjyu, T., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. 143–164.

- Karkazis, P.; Trakadas, P.; Leligou, H.C.; Sarakis, L.; Papaefstathiou, I.; Zahariadis, T. Evaluating routing metric composition approaches for QoS differentiation in low power and lossy networks. Wireless Networks 2013, 19, 1269–1284. doi:10.1007/s11276-012-0532-2. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotis, K.; Panagiotis, T.; Helen, L.; Sarakis, L.; Papaefstathiou, I.; Zahariadis, T. Evaluating routing metric composition approaches for QoS differentiation in low power and lossy networks. Wireless Networks 2013, 19. doi:10.1007/s11276-012-0532-2. [CrossRef]

- Ancillotti, E.; Vallati, C.; Bruno, R.; Mingozzi, E. A reinforcement learning-based link quality estimation strategy for RPL and its impact on topology management. Computer Communications 2017, 112, 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2017.08.005. [CrossRef]

- Khallef, W.; Molnár, M.; Benslimane, A.; Durand, S. Multiple constrained QoS routing with RPL. ICC: International Conference on Communications; IEEE: Paris, France, 2017; Bridging People, Communities, and Cultures. doi:10.1109/ICC.2017.7997081. [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Sen, A.; Zhang, W.; Tang, J.; Thulasiraman, K. Finding a path subject to many additive QoS constraints. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2007, 15, 201–211. doi:10.1109/TNET.2006.890089. [CrossRef]

- Khallef, W.; Molnar, M.; Bensliman, A.; Durand, S. On the QoS routing with RPL. 2017 International Conference on Performance Evaluation and Modeling in Wired and Wireless Networks (PEMWN), 2017, pp. 1–5. doi:10.23919/PEMWN.2017.8308028. [CrossRef]

- Barthel, D.; Vasseur, J.; Pister, K.; Kim, M.; Dejean, N. Routing Metrics Used for Path Calculation in Low-Power and Lossy Networks. RFC 6551, 2012. doi:10.17487/RFC6551. [CrossRef]

- Clímaco, J.; Pascoal, M. Multicriteria path and tree problems: Discussion on exact algorithms and applications. International Transactions in Operational Research 2012, 19. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3995.2011.00815.x. [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Lee, D. An Efficient Local Repair-Based Multi-Constrained Routing for Congestion Control in Wireless Mesh Networks. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 2893494:1–2893494:17.

- Torkzadeh, S.; Soltanizadeh, H.; Orouji, A.A. Multi-constraint QoS routing using a customized lightweight evolutionary strategy. Soft Computing 2018, 23, 693 – 706.

- Anh Quang, P.T.; Sanner, J.M.; Morin, C.; Hadjadj-Aoul, Y. Multi-objective multi-constrained QoS Routing in large-scale networks: A genetic algorithm approach. 2018 International Conference on Smart Communications in Network Technologies (SaCoNeT), 2018, pp. 55–60. doi:10.1109/SaCoNeT.2018.8585634. [CrossRef]

- Julstrom, B. Greedy heuristics for the bounded diameter minimum spanning tree problem. Journal of Experimental Algorithmics, 14, 1:1.1-1:1.14. ACM Journal of Experimental Algorithmics 2009, 14. https://doi.org/10.1145/1498698.1498699. [CrossRef]

- Goemans, M.X. Lecture notes in Computer Assisted Diagnosis, 2007.

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Fang, C.; Zhang, P. Ultra-Low Latency Multi-Task Offloading in Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32569–32581. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3061105. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L. Energy-Efficient Collaborative Task Computation Offloading in Cloud-Assisted Edge Computing for IoT Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19. doi:10.3390/s19051105. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, F. Overview of Task Offloading of Wireless Sensor Network in Edge Computing Environment. 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), 2023, pp. 1018–1022. doi:10.1109/ICEICT57916.2023.10245473. [CrossRef]

- Osibo, B.K.; Jin, Z.; Ma, T.; Marah, B.D.; Zhang, C.; Jin, Y. An edge computational offloading architecture for ultra-low latency in smart mobile devices. Wirel. Netw. 2022, 28, 2061–2075. doi:10.1007/s11276-022-02956-4. [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, J.; Aldossary, M. A novel approach for IoT tasks offloading in edge-cloud environments. J. Cloud Comput. 2021, 10. doi:10.1186/s13677-021-00243-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, W.; Yu, Y. Research on Intelligent Scheduling Mechanism in Edge Network for Industrial Internet of Things. Security and Communication Networks 2022, 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5358873. [CrossRef]

- Dolui, K.; Datta, S.K. Comparison of edge computing implementations: Fog computing, cloudlet and mobile edge computing. 2017 Global Internet of Things Summit (GIoTS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–6.

- Cousin, B.; Molnar, M. Fast reconfiguration of dynamic networks. 2007 International Workshop on Dynamic Networks. IRISA/INSA, 2007, pp. 1–6.

- Cousin, B.; Adépo, J.C.; Oumtanaga, S.; Babri, M. Tree reconfiguration without lightpath interruption in WDM optical networks. Int. J. Internet Protoc. Technol. 2012, 7, 85–95. doi:10.1504/IJIPT.2012.050217. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Shahraki, A.; Taherkordi, A. Deep Learning for Network Traffic Monitoring and Analysis (NTMA): A Survey. Computer Communications 2021, 170, 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2021.01.021. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, B.; Molnár, M.; Saleh, M.; Benslimane, A.; Kassem, S. Dynamic Distributed Monitoring for 6LoWPAN-based IoT Networks. Infocommunications journal 2023. doi:https://doi.org/10.36244/ICJ.2023.1.7. [CrossRef]

- Mehlhorn, K.; Näher, S. LEDA: A Platform for Combinatorial and Geometric Computing; Cambridge University Press, 1999.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).