1. Introduction

Two outstanding problems in the early evolution of the Earth concern the origins of the Moon and of the two large low-velocity provinces (LLVPs) sitting on the core-mantle boundary (CMB). The African and Pacific LLVPs extend thousands of kilometers laterally and possibly more than 1000 km vertically above the CMB [

1,

2,

3]. They are characterized by low seismic wave velocities compared to the lower mantle generally. The velocity anomalies suggest that the LLVPs have a different chemical composition than the surrounding mantle.

Numerous suggestions have been made for the origin of these structures. One possibility is that LLVPs represent subducted oceanic crust that has accumulated over billions of years [

4]. Recent simulations indicate, however, that subducted oceanic crust would have higher rather than lower velocities relative to the surrounding mantle [

5]. Oceanic crust would also have been too thin and lacking in negative buoyancy to survive the descent to the CMB intact and form structures there [

6]. Alternative models feature LLVPs originating from crystallized remnants of a basal magma ocean or from incomplete core-mantle differentiation [

7,

8] or as anomalies linked to Fe

3+ enrichment of the mantle mineral bridgmanite [

8].

Concerning the origin of the Moon, studies of moon rocks have shown that the isotopic compositions for oxygen, chromium, titanium, potassium and silicon of the Moon are very similar to those of the bulk silicate Earth (BSE, i.e., mantle + crust) (see [

9] and references therein). For oxygen and silicon – the two most abundant elements on the Earth and the Moon – the compositions are identical.

These similarities are hard to explain in scenarios involving collisions of Earth with other bodies. In the giant impact hypothesis, for example, collision of a Mars-sized body (‘Theia’) with the proto-Earth created a debris ring, which then coalesced to form the Moon. Theia would almost certainly have had different isotopic ratios than the proto-Earth, however, and so little if any of its mass could have ended up in the Moon.

To address this problem, it has been suggested that a fast-moving, small impactor collided with a proto-Earth having two to three times the angular momentum of the present Earth-Moon system [

10]. This could generate a moon formed almost entirely of the proto-Earth’s mantle but required separate mechanisms to shed the excess angular momentum. An alternative suggestion – that a high-speed head-on collision between bodies of similar mass yielded a homogeneous Earth and Moon – also would have left the system with too much angular momentum [

11].

More recently, a novel proposal links the origin of the Moon to that of the LLVPs. The absence of a Theia isotopic signature in the Earth and the Moon can be explained if the fragments of Theia sank down all the way to the lower mantle, there to become the future LLVPs [

12].

At the same time, the most straightforward hypothesis to explain the isotopic similarities of the Earth and the Moon is that the Moon was formed entirely of mantle and crust material of the proto-Earth [

9]. In his classic ‘fission’ model, George Darwin [

13] proposed that the Moon separated from a hot and rapidly spinning Earth. Centrifugal forces and resonant effects of solar tides overpowered gravity at the equatorial regions, leading to the Moon’s formation. To boost the tidal and centrifugal forces, Darwin’s model was later refined by supposing that formation of the Earth’s core triggered a faster rotation rate for the proto-Earth [

14,

15]. Together with a reduction in the Earth’s moment of inertia, this would have allowed Earth’s rotation period to reach the critical value of 2.65 hours required for Moon separation in Darwin’s model. The Earth-Moon system today has only 27% of the angular momentum that such a fast-spinning proto-Earth would have had, however, and a convincing rationale for the fate of the other angular momentum has yet to be found [

9].

Alternatively, supposing that the angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system changed only slightly over time and that there was no giant impactor, some authors have suggested that the lunar separation might have been assisted by an explosion occurring deep inside the Earth [

16,

17,

18]. In their ‘deep georeactor’ model, de Meijer et al. [

9] proposed that an explosion near the CMB was triggered by nuclear fission. Unlike natural nuclear georeactors, such as those in Gabon, the proposed deep georeactors employ fast-moving neutrons and are more akin to fast breeder reactors [

19]. They arise in their model through the concentration of lithophilic, fissile elements like U and Th in the CMB region in a so-called ‘hidden reservoir’. The existence of such a mantle reservoir segregated from normal plate tectonics had earlier been suggested by the finding of elevated Sm/Nd and

142Nd/

144Nd ratios in mantle rocks compared to chondrite samples [

20].

In their initial model, about 2.5 ⨯ 10

30 J of energy was required to expel the Moon from the Earth’s surface. This value was obtained assuming that the angular momentum of the proto-Earth was similar to that of the present Earth-Moon system and that the oblateness of the proto-Earth was

a/

c = 2, where

a and

c are the Earth’s long and short axes respectively. This energy estimate was later reduced to 10

29 J, when the model was found to be still physically relevant for

a/

c = 1.2 [

21].

Hydrodynamic modelling showed that a shock wave created by rapidly expanding plasma could disrupt and expel overlying mantle rock. Immediately after separation from the Earth, the Moon was estimated to orbit the Earth at a distance rEM = 1 ⨯ 108 m with a rotation period ~3.8 days. The proto-Earth’s rotation period would have been ~5.8 hours, immediately increasing after the separation event to ~9.0 hours.

As discussed in

Section 2, the georeactor model of the Moon’s origin has several difficulties relating to the possibility of verification, the placement of the fissile elements and the timing of their detonation.

In this paper, it is proposed, as in [

12], that the origins of the Moon and the LLVPs are indeed connected. But rather than modelling the LLVPs as remnants of Theia, we propose that the precursors of the two LLVPs predated the Moon’s existence. We then adapt the deep georeactor model by substituting an alternative energy source for the explosion. This energy is derived from a theoretical process involving the cosmological constant, Ʌ, and a conversion of gravitational energy to electromagnetic energy. With this new source, energy steadily accumulated over millions of years in the LLVPs until an explosion in one of them – presumably the precursor of the Pacific LLVP – ejected the Moon. The origins of the LLVPs, plate tectonics and large igneous provinces (LIPs) are then placed in a unified scheme.

The Ʌ process at the center of our model is suggested to be ubiquitous in nature. It involves a slow conversion of gravitational energy to electromagnetic energy in proportion to the Hubble constant,

H0 [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This energy release, which we term the ‘Ʌ luminosity’, balances the energy lost from photons due to the Hubble redshift. Evidence for it can be found in the excess heat radiated from planets [

22,

27,

28] and the bolometric luminosities of white dwarfs, neutron stars and supermassive black holes [

23]. The Ʌ luminosity also forms the basis for a model of quantum gravity [

25,

26].

Recently, it was proposed that gravity and the Ʌ luminosity together drive a cosmic cycle operating on photons of the cosmic microwave background [

26]. In the first part of the cycle, photon energy is absorbed via the Hubble redshift to drive gravity. In the second part, these energy-depleted photons are then reenergized by the Ʌ luminosity. The latter process furnishes the cosmological constant Ʌ, in Einstein’s original sense of a cosmic counterbalancing agent to gravity.

As discussed in

Section 4, about one-third of the heat released via this process inside the Earth would be generated in the core, at a present rate of about 10

22 J/yr. Since the core’s volume is only about one eighth of the Earth’s, the rate of energy accumulation per unit volume would be over three times higher in the core than in the Earth generally. In the period just after core segregation on the proto-Earth, the efficient modern system of heat delivery to the surface via deep mantle plumes and plate tectonics was not yet in place. Any heat generated in the core would thus have been trapped by the poorly conducting mantle. This energy buildup culminated in explosive release of the moon-forming materials.

The Earth’s geological history unfolds in three distinct phases in our model. The first of these is the formation of the two proto-LLVPs. Here we build on recent evidence given by Ma and Tkalčić [

29] for a toroidal equatorial belt of superheated fluids existing just below the CMB. This belt has seismic velocities ~2% lower than in the core generally. This distribution was considered consistent with light elements like O and H being relatively more abundant in the torus than in the outer core generally and also with the observed pattern of greater heat transfer in equatorial than in polar regions.

We propose that this equatorial belt in the outer core is generated by heat released with the Ʌ luminosity and that an analogous belt formed on the proto-Earth. Superheated material from the proto-belt, likewise rich in lighter elements, then traversed the boundary at certain points and mixed with mantle material. Diurnal resonance pressures generated by solar tides, together with requirements for rotational balance, eventually created two prominent equatorial bulges – the precursors of the two antipodal LLVPs. Superheated light elements would have become relatively more concentrated in these magmatic structures.

With plate tectonics and large plume conduits for heat not yet available, energy would have steadily built up in the proto-LLVPs until the required 10

29–10

30 J of energy accumulated in one of them. A cataclysmic explosion then ejected overlying mantle material into a low Earth orbit. The sequence of steps from the explosion event to Moon formation then essentially follows that of de Meijer et al. [

9], which was later updated [

21]. With subsequent release of pressure in the core following the explosion, the other proto-LLVP did not experience a similar event.

In the final, ongoing phase, the Ʌ luminosity mechanism would account for later events on the Precambrian and the present Earth that have resisted clear explanation thus far. After the Moon ejection, pressures would soon have started to build in the LLVPs again. Subsequent release of volatiles under pressure would have been expedited by crevices and conduits that the Moon ejection had formed. A cycle of pressure buildup in the core followed by explosive release in superplume explosions would then account for the periodic formation of large igneous provinces (LIPs) and their associated mass extinctions. Eventually, continuing heat release from the LLVPs gave rise to the efficient modern system of plate tectonics.

The paper is arranged as follows. In the first section, we briefly consider some specific problems of the deep georeactor model for the Moon’s origin. We then review the evidence and theoretical basis for the Ʌ luminosity. The origins of the LLVPs and the Moon through the action of the Ʌ luminosity are then described in the next section, while the origins of plate tectonics are considered in the one following. We lastly discuss the possibilities for verification of the model.

3. Geological Energy from Ʌ

The deep georeactor model of the Moon’s origin was proposed by de Meijer et al. because no other source of energy seemed available to eject the proto-lunar material into a low Earth orbit. There is, however, theoretical and observational evidence for a quite different source of explosive energy: the internal heating of all bodies due to conversion of gravitational energy to photonic energy via Ʌ.

Decay of the Earth’s internal gravitational energy had long been seen as a possible driver of Earth’s geology. This was largely connected with Dirac’s notion of a decreasing gravitational constant [

35]. Pascual Jordan suggested that the resulting gravitational decay gave rise to a slow expansion of the Earth’s radius [

36,

37,

38,

39]. The supposed expansion involved phase changes within the Earth. The problem of Dirac-type theories, however, is that there has been little evidence that the gravitational constant

G changes over time.

In a different vein, the author proposed a gravitational conversion process involving the Hubble redshift of light [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The basic concept is that the Hubble redshift ‘flips’ photons (positive energy) to gravitons (a hidden form of photonic energy) and that a reverse process converts graviton energy back to ordinary photon energy. In the former instance, the lost photon energy is directed towards gravitation, making gravitational energy wells more negative, while the reverse process reenergizes photon energy in the universe. Balance between those two processes would imply that the cosmic pools of gravitational and electromagnetic energy remain constant over time.

The theoretical basis for these processes was suggested to lie in a different conceptualization of spacetime: as being entirely photonic in nature. In this picture, spacetime is comprised of filaments of photon pairs (gravitons) which interconnect all the masses of the observable universe. The energy of the photonic filaments is assumed to be equal in magnitude to the gravitational potential energy of the masses they connect, |U|. As real energy quanta, the total amount of photonic energy (and thus |U|) in these filaments must have a constant value in the universe. When two particles approach each other in gravitation, increasing their share of the total |U|, other spacetime filaments must therefore diminish in energy by amounts which offset this energy increase.

In this configuration, gravity can be modeled as an absorption of photonic energy in these filaments due to the Hubble redshift. To have symmetry, the reverse process must then transfer energy from this photonic spacetime back to ordinary photons. The resulting blueshift in these photons can be identified with the cosmological constant, Ʌ, in Einstein’s original sense [

26].

Through the model Ʌ process, energy would slowly be released within every mass or system of masses – from a single atom to the universe as a whole. Recent evidence from planets, white dwarfs, neutron stars and SMBHs suggests that energy is released at the rate:

where

U is the internal gravitational energy (conventionally negative),

H0 is the Hubble constant and

LɅ is the ‘Ʌ luminosity’. The latter term replaces the one previously used – the Hubble luminosity – to emphasize the possible links with cosmology.

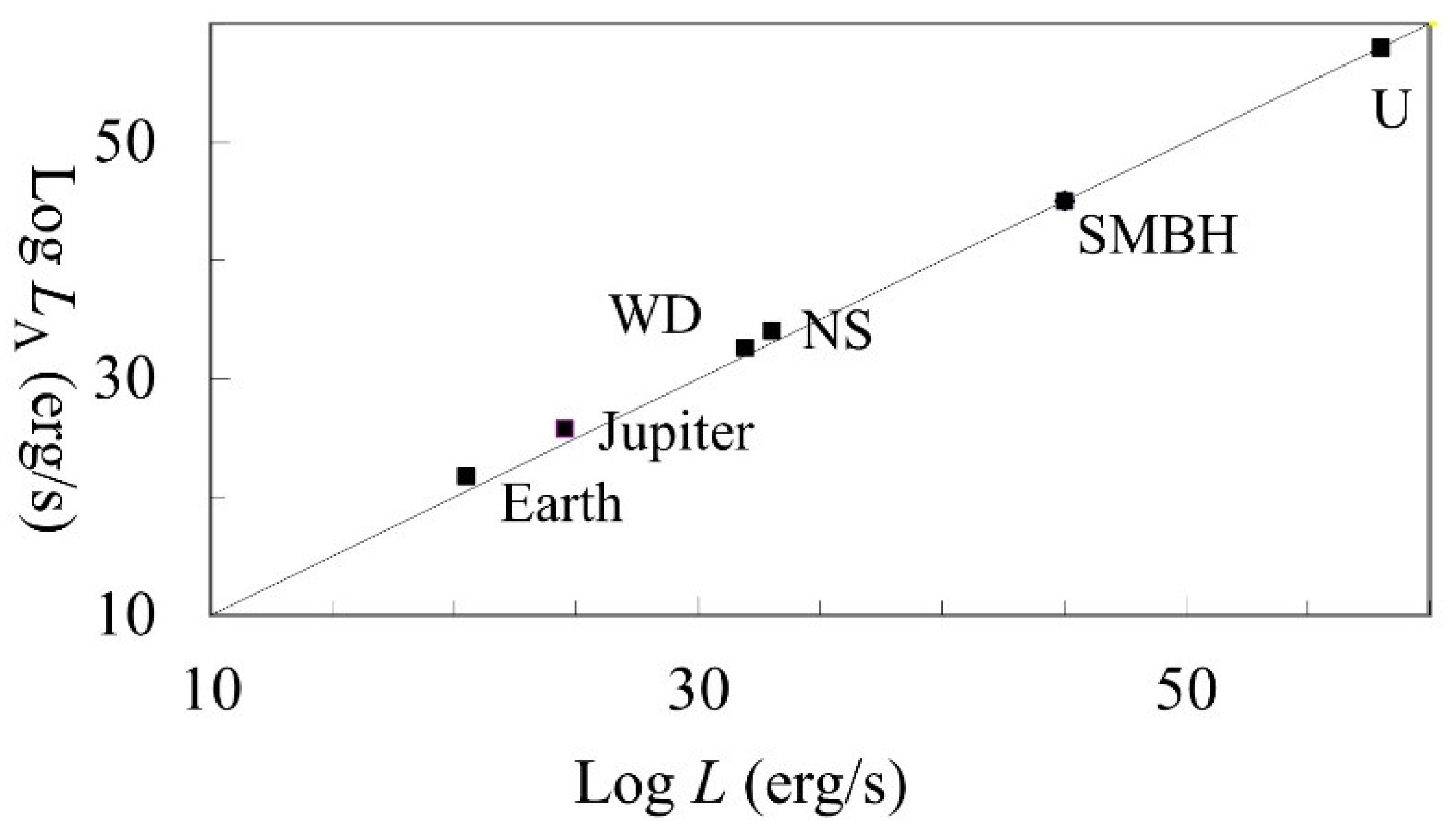

Since

U is proportional to

M2 in these systems, the energy release in these large bodies would be enormous. In main sequence stars like the Sun, the Hubble luminosity would be dwarfed by stellar fusion. In collapsed stars, such as white dwarfs and neutron stars, the dependence on

R-1 gives rise to luminosities far greater than stellar fusion. This is shown in

Figure 1.

Relation to Black Holes and Cosmology

The Ʌ luminosity was also recently associated with black holes and a black hole universe, one which may or may not involve cosmic expansion [

26]. Here the universe and black holes are proposed to have shell-like structures. These structures are stabilized by the Ʌ luminosity, which energizes photons of the characteristic blackbody radiation confined within these shells. In the case of the universe these are photons of the cosmic microwave background. The energized photons exert outward pressures on the baryons of the shells. In the universe, they thus function as Einstein’s cosmological constant Ʌ, stabilizing the cosmic shell against gravitational collapse. The same process prevents shell black holes from collapsing to a singularity.

In terms of general relativity, these shell structures can be described using the Ni solutions for their field equations [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. With the Ni solutions, originally applied to the structures of neutron stars, the spacetime within spherical shells of matter is not flat and Minkowski, as conventionally assumed, but is instead curved. The Ni solutions in addition can possibly explain certain cosmological anomalies, such as the Hubble tension. It is the Ʌ luminosity, however, which forms and stabilizes these shell structures.

4. Origin of LLVPs and the Moon

We next consider the specific sequence of steps which gave rise to the LLVPs and the Moon from the Ʌ luminosity in our model. Based on Hf–W analyses of lunar rocks, the Moon’s formation is estimated to have occurred 50–150 Ma after core–mantle differentiation [

31]. If we suppose that the Earth’s system of mantle plumes and plate tectonics was not yet in place, then during this ~100 Ma interval any heat added to the core via the Ʌ luminosity would have largely trapped there by the poorly conducting mantle.

This trapped energy would then have been available to power an equatorial belt in the outer core antecedent to the one described by Ma and Tkalčić [

29]. Those authors suggested that the seismic velocities in the belt are consistent with a high concentration of light elements, like H and O. Circulation of this fluid in the toroidal belt on the proto-Earth would have given rise to the Earth’s magnetic field. The mechanism and energy requirements for the geodynamo, either on present Earth or the proto-Earth, are still not well understood [

45]. One estimate of the maintenance energy of the geodynamo is that it roughly equals the total heat flow of 46 TW [

34], well above current estimates for heat release in the core at present. Prior to significant plume flows, this route for energy dissipation from the core could have been the primary one.

In analogy with Darwin’s model, solar tidal forces would then have acted on the heated fluids of the toroidal belt. Diurnal resonance pressures induced by the solar tides gave rise to two magmatic provinces extending outwards from the belt: the forerunners of the Pacific and African LLVPs. The antipodal positioning possibly arose to mitigate instabilities in the proto-Earth’s rotation that might otherwise have been induced by a single province.

A core origin of LLVP material is consistent with present-day LLVPs having elevated Fe compared to the lower mantle. The presence of iron has been suggested to account for the low shear velocities of the LLVPs [

8]. Given that the low seismic velocities seen in the Ma-Tkalčić toroidal belt were attributed to elevated concentrations of light elements, like O and H [

29], the low velocities in LLVPs might also reflect their enrichment with light elements from this belt.

Moon Ejection by Ʌ Explosion

The next step in our model sequence is the Moon ejection event. As noted above, this event required the release of 10

29–10

30 J of energy from a point just above the CMB. The present hypothesis requires that this energy was generated in the Earth’s core, primarily through the Ʌ luminosity (Equation (1)). Of the Earth’s gravitational potential energy, it is estimated that 36.8% is in the core and of that only 2.1% in the inner core [

46]. Thus, over one-third of the energy generated inside the Earth through the Ʌ luminosity would be deposited directly in the outer core. The remaining two-thirds would be released in the mantle. By virtue of the mantle’s far greater volume, however, the temperatures produced in the outer core would far exceed the mantle temperatures.

Using the currently estimated value for Earth’s

U of −2.5 ⨯ 10

32 J and a value for

H0 of 2.2 ⨯ 10

-18 sec

-1, the Earth’s total Ʌ luminosity would be 550 TW. From the estimates above, ~200 TW of this would be generated in the outer core and the remaining ~350 TW in the mantle. These values far exceed the usual estimates for heat flows in the core and mantle. As described previously and again in

Section 5, however, they can possibly be linked to phase changes induced in the mantle associated with mantle plumes, the emergence of plate tectonics and a slightly increasing Earth radius [

28].

Taking the rate of energy generation in the core of 200 TW and a short time interval between core segregation and Moon origin of 50 Ma, the total energy generated in the core would have been 3 ⨯ 10

29 J. Even with this short interval, this is more than the 1 ⨯ 10

29 J energy needed to explosively form the Moon using the updated estimate in [

21]. As noted above, that estimate allows the nascent Earth-Moon system to have

L/

L0 ≈ 1 and

a/

c ≈ 1.2.

This energy would have been generated at precisely the right position in the Earth’s outer core to form the Ma-Tkalčić torus. Superheated light elements in the torus and attached proto-LLVPs would steadily have raised temperatures and pressures therein. Then, when ~10

29 J of energy accumulated in one of the LLVP precursors, an explosive release of this energy created the Moon. The subsequent steps in the evolution of the Earth-Moon system would essentially follow those in [

9].

The large and circular Pacific basin has been resurfaced many times by plate tectonics. Its great size – together with the relatively late activity of the African superplume – suggest that the Moon was ejected above the structure that was precursor to the Pacific LLVP. In relation to Darwin’s original hypothesis, it had been supposed by Osmond Fisher that the Moon arose from the trench region of the Pacific [

34].

Following the Moon ejection event, heat release from the core would thereafter have been assisted by new conduits formed as a result of the explosion itself. Accordingly, the temperatures and pressures within the LLVP precursors would never again have reached the levels attained just prior to the Moon’s ejection. For this reason, a second major ejection event above the African proto-LLVP may have been suppressed.

5. Origin of Mantle Plumes, Plate Tectonics and Large Igneous Provinces

In the third phase of planetary evolution, following ejection of the Moon, heat dispersal in deep mantle plumes emerging from the proto-LLVPs gives rise to novel modes of plate tectonics. As emphasized previously [

28], the Ʌ luminosity would release heat within the Earth at a rate far greater than the currently estimated heat budget ~46 TW. To account for this large discrepancy there would need to be energy sinks in the Earth to consume the extra energy.

One possibility, previously suggested in [

28], is based on the finding that deep mantle plumes extend all the way down to the CMB and are also much larger than had hitherto been expected [

47]. These plumes are here presumed to have first risen from the proto-LLVPs. While deep mantle plumes presently appear to easily traverse the 670 km barrier into the upper mantle, much evidence suggests that subducting slabs encounter greater resistance crossing this barrier on the other way towards the CMB. Nolet et al. [

48] observed that if the mass flows do not balance, there would be a net flow of mass from the deep lower mantle into the upper mantle. In this case, due to the lower pressures existing in the upper mantle, the excess mass of plume materials reaching there would transform to minerals with lower densities than they had at the mantle base. An increase in the mantle volume and therefore the Earth’s radius would then be implied [

28].

The magnitude of the total potential radial increase was estimated using the African superplume. In their estimate of the total rising volume flux Qv in deep mantle plumes, Nolet et al. excluded the African superplume, arguing that its great width invalidated the simple assumptions they had used. With those assumptions, the heat flow Qc for the African superplume alone would have been 25.4 TW, almost as much as their upper estimate for the entire plume heat flux ~30 TW. The corresponding flux Qv for the African superplume would have been 477 km3 yr–1, twice the rate of subducted oceanic lithosphere.

Given the large role of the African superplume in the present rifting in Africa and the earlier breakup of Pangaea, however, their estimates may be far too low. Taking their data for the African superplume and using a simple volume conversion factor – for high-density lower mantle material to low-density upper mantle material – it was estimated that the rate of radial increase of the Earth due to this plume alone would be 0.13 mm yr

-1 [

28]. To raise the Earth this much would require ~100 TW of power in the African superplume, far greater than the estimate of 25.4 TW in [

48]. Assuming a proportional increase in

Qv for the remaining plumes, the total plume power could be 200‒300 TW. The associated expansion rates would then be 0.2‒0.3 mm yr

-1. These rates would be consistent with observations in space geodetic, gravimetric and seismic studies which indicate a radial increase at present of 0.1–0.4 mm yr

–1 [

49,

50,

51].

Of the 550 TW added to the Earth via the total Ʌ luminosity, slow Earth expansion could thus conceivably account for perhaps 200‒300 TW of it. Another possible large sink is the Earth’s geodynamo. If the Earth’s geodynamo has a maintenance energy two or three times the estimate in [

34], or ~100–150 TW, it could account for much of the remainder.

Relation to Large Igneous Provinces

Like the LLVPs, the origins of the LIPs have been the subject of much debate. Flood basalts and LIPs have Sm/Nd ratios consistent with a derivation from the LLVPs [

52]. Palaeo-geographic relationships between Phanerozoic LIPs and LLVPs further suggest that most LIPs that erupted in the past 320 Myr did so directly over an LLVP [

53,

54,

55]. The geographical locations of LIPs are also statistically correlated with those of LLVPs [

56]. The heat-generating capacity of the Ʌ luminosity near the CMB, by promoting mantle melting, mantle upwelling and plume generation at the LLVPs, would be consistent with these LLVP-derived explanations for the LIPs.

At the same time, an alternative origin suggested for the LIPs is that plate-related stresses induce ruptures of the lithosphere allowing melt from shallow sources in the upper mantle to reach the surface via convection. This is not inconsistent with the present hypothesis, however, as the energy powering the plate ruptures in the end would also be provided largely by the Ʌ luminosity.

6. Discussion

In their model, de Meijer et al. saw no source of energy but nuclear fission for the 2.5 ⨯ 10

30 J of energy required to explosively eject the Moon. In this paper, we have identified a possible alternative source of energy for the explosion derived from the previously suggested Ʌ luminosity. Since these two models have broad similarities following the explosion, the main points of comparison lie in the events preceding it. In

Section 2, some difficulties were pointed out concerning the availability of sufficient radiogenic energy to power the explosion.

Prospects for testing the feasibility of the present model based are somewhat better. While the general relationship in

Figure 1 affords basic support for the existence of the Ʌ luminosity, confirming evidence in classes of objects on different scales is still needed. For planets, it would be necessary to distinguish it from other possible sources of internal heat, such as deep georeactors and hypothesized planetary cold fusion [

34,

57]. One approach would be to measure the heat emission from very small bodies, such as icy planetary moons or asteroids. Here radiogenic energy would largely be absent and in some cases tidal energy would be minimized. Even amongst chondritic planetoids and moons, a signature of the Ʌ luminosity could be detectable. This is because

LɅ would be generally proportional to

M2, while radiogenic heating would scale roughly linearly with

M.

Further research on deep mantle plumes and their heat and volume fluxes could also shed light on how much energy the Ʌ luminosity is generating inside the Earth at present. In our model, this energy is the prime driver of geological processes. If linked to slow expansion of the upper mantle, the plume fluxes in addition are important sinks for Ʌ energy in our scheme. Studies of the geodynamos of Earth and other planets are also needed to constrain their contributions to internal heat budgets.

Evidence for the Ʌ luminosity might also be found in quantum experiments conducted at temperatures near absolute zero. Due to the Ʌ luminosity, a mass cannot be cooled all the way to 0 degrees K. A miniscule heat emission would always take place, perhaps detectable in experiments involving quantum interference effects. Indirect evidence for the model could also come with further theoretical insights into the fundamental processes underlying gravity and its proposed reverse process, the Ʌ luminosity. These include fitting the Ʌ luminosity more fully within the general relativity framework and connecting the underlying model of photonic spacetime to quantum physics.

Lastly, in this paper we have not addressed the evolution of the Earth-Moon system after the Moon-forming explosion in terms of its angular momentum, energy and Earth-Moon separation. While this evolution may have proceeded in the manner described by de Meijer et al., evidence of a general secular increase in the orbits of moons and planets possibly suggests that here too a gravitational decay process could be involved [

58,

59].