Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

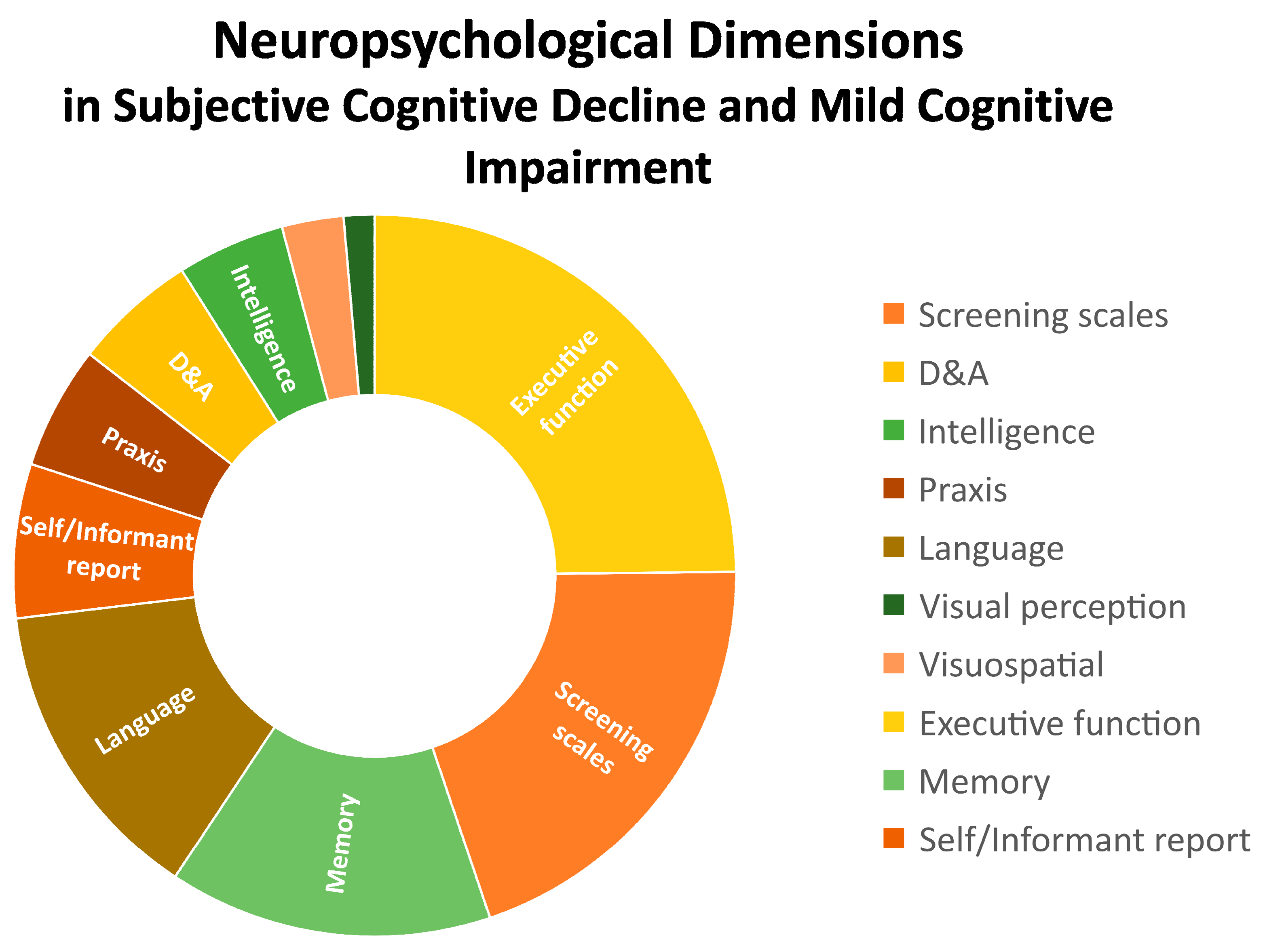

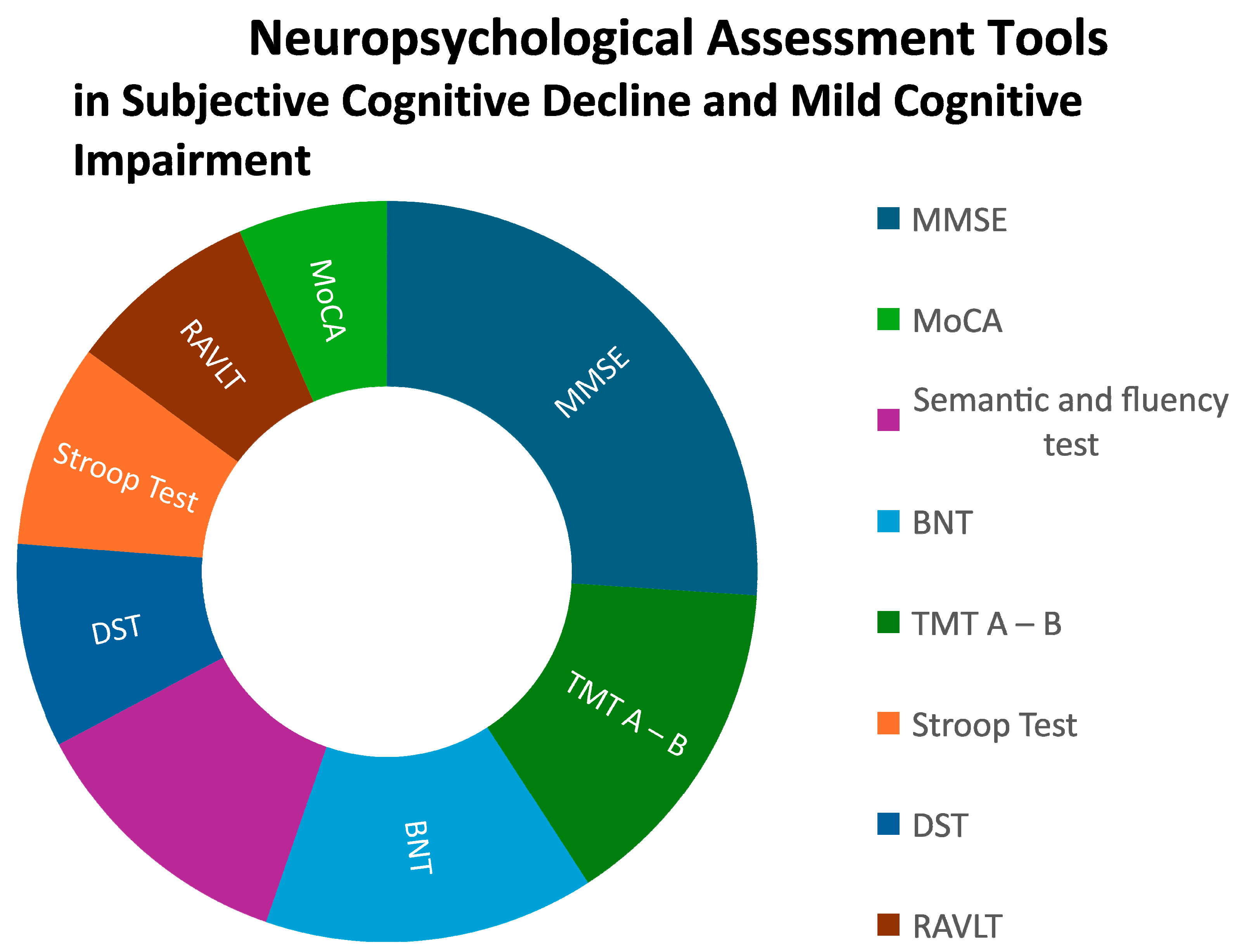

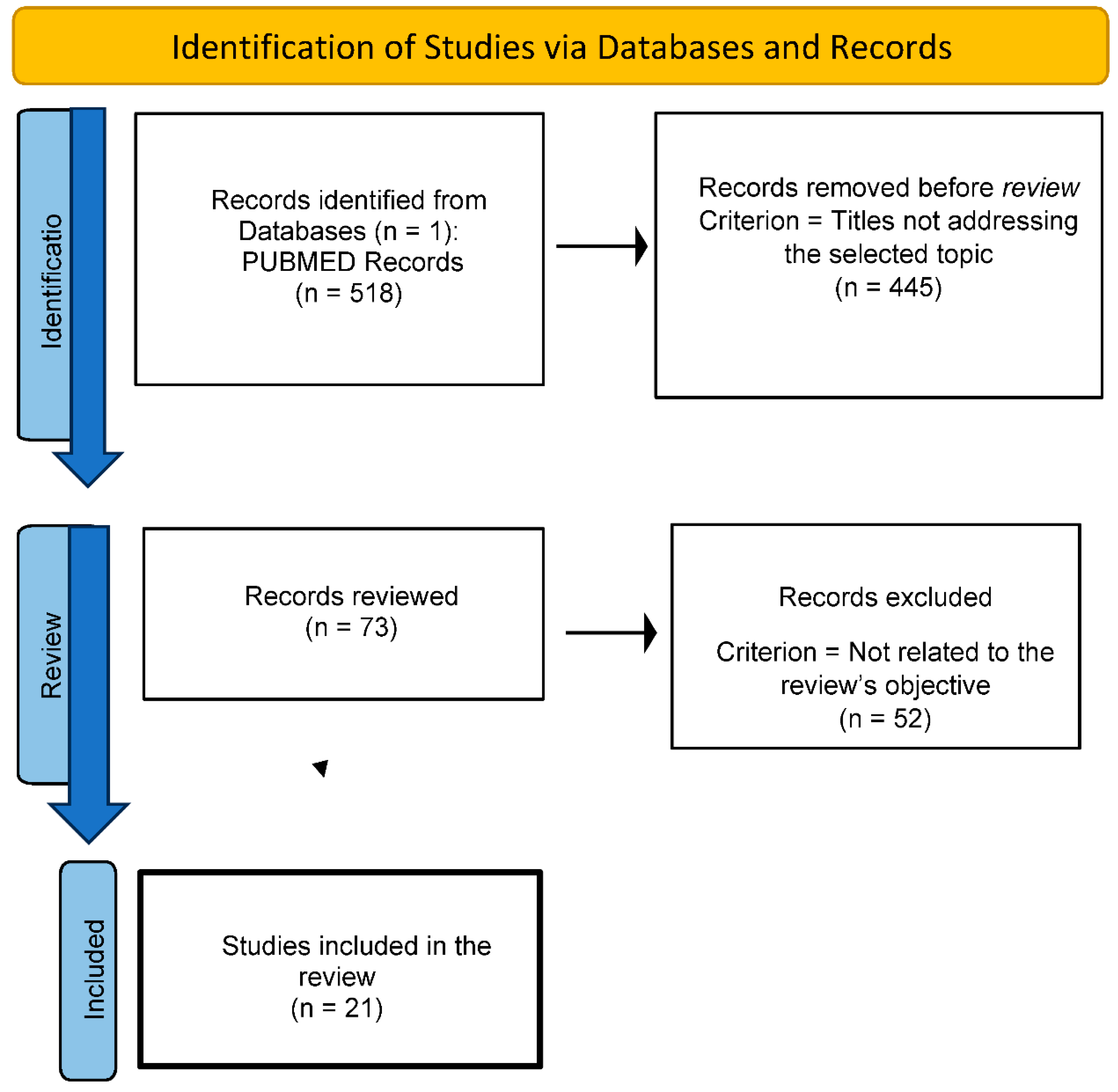

In an aging world with an increasing prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases that could benefit from early diagnosis and interventions, neuropsychological testing is key when defining cognitive profiles of middle aged and older people. Detecting subtle cognitive changes such as those referred to in subjective cognitive complaints - a clinical entity scarcely studied- and underdiagnosed early stages of Mild Cognitive Impairment is critical for early detection and preventive interventions in primary care settings. This systematic review analyzed empirical data (Pubmed database, between 2009 and 2024) from 21 papers with an exploratory, cross-sectional and prospective scope in this field. A part of screening tests (20%), a wide spectrum of neurocognitive tests was used to assess specific domains. Executive functions (25%), language (14%), and memory (14%) were the three most common, eligible for brief cognitive assessment, as compared to praxis (6%), intelligence (5%) and visual / visuospatial perception (4%). Interestingly, self or informant reports and the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms (depression and anxiety) emerged as domains to be considered. A need for methodological consensus appeared as a strong limitation, even in those main dimensions, where MSE (51,6%), TMT A-B (29,4%), Semantic and fluency test (23,8%), BNT (28,6%), Stroop Test (17,6%), DST (17,6%), RAVLT (16,7%) and MoCA (12,9%) were the most common tools. However, stronger efforts to ensure greater specificity and sensitivity to early changes as well as consensus on which neuropsychological protocols/domains and clinical analysis should contain are needed to respond to the increasing mental health demands of the aging population.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic Search (Databases, Descriptors, Search Formulas)

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Empirical research on neuropsychological tools used in the study of subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment.

- -

- Studies published in the last 15 years with a specific population focus on individuals aged 60 years or older.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Studies addressing neuropsychological tests for subjective cognitive decline in other clinical contexts.

- -

- Research exploring neuropsychological assessments in advanced stages of dementia.

2.4. Flow Chart

3. Results

| Authors [Reference] Country |

Sample Subjects’ diagnosis (gender ratio) [mean age] {mean years of education} |

Dimensions assessed |

Tests used |

| Migliacci et al. [16] Argentina |

204 subjects with MCI 51 aMCI (36W:15M) [75.07] 11 naMCI (7W:4M) [69.63] 142 MCImult (104W:38M) [70.58] {-} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, ADAS, CDR, MDRS - WAIS Transitive and intransitive praxis, CDT, RCFT Semantic and fluency test, BNT - RCFT Digits, FAB, TMT A – B, Stroop Test, Wisconsin Test, SMOCT, RAVLT, RBMT |

| Saunders and Summers [17] Australia |

131 subjects (68 W and 63 M): 25 HC [69] {13.5} 32 subjective-MCI [71]{13} 60 amnestic-MCI [71] {13.1} 14 mild AD [76] {12} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

- - WTAR, FSIQ - BNT - - - RAVLT, PAL - |

|

Abbate et al. [18] Italy |

119 subjects with MCI (74 W:45 M) [77.38] {9.27} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE - - RCFT VFT, PNT - - RCPM, TMT, DST, DCT PRT Informant reports on cognitive functioning (structured interview) |

| van Harten et al. [19] Netherlands |

132 participants with SCC (56 W:76 M) [61.4] {6} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE - - - Naming category fluency - - TMT A-B, DST VAT, RAVLT - |

| Toledo et al. [20] USA |

522 subjects (253 W:269 M) 307 CN subjects (138 W:169 M) [73.9] {-} 71 subjects SCC (25 W:46 M) [71.6] {-} 51 subjects executive SCI (21 W:30 M) [77.3] {-} 66 subjects memory SCI (49 W:17 M) [75] {-} 27 subjects multi-domain SCI (20 W:7 M) [78] {-} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, ADAS - - - - - - - - - |

| Seo et al. [21] Korea |

265 participants (178 W:79 M) 188 CN subjects (120 W:60 M) [71.94] {9.69} 77 subjects pre-DCL (58 W:19 M) [72.64] {9.64} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, SNSB GDS - RCFT CPFT, K-BNT - RCFT TMT A-B, DST, Stroop test, SVLT SMCQ (informant report) |

| Verfaillie et al. [22] Netherlands |

233 participants SCD (107 W: 125 M) [62.82] {5.32} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE GDS - - Fluency Animals - - TMT A-B, DST, Stroop test RAVLT, VAT - |

| Fogarty et al. [23] England |

55 participants (35 W:20 M) 23 subjects mild AD (9 W:14 M) [73.95] {15.56} 32 adult control subjects (26 W:6 M) [69.84] {13.96} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, MoCA GDS - - - - - - - BRIEF-A |

| Bae et al. [24] South Korea |

1442 participants (-) [-] {-} 1088 HC subjects (-) [-] {-} 354 SCC (-) [-] {-} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, K-DRS - - - - - - - - - |

| Rios et al. [25] Mexico |

69 subjects MCI (54 W:15 M) [71.79] {2.76} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, CCT YDS WAIS RCF BNT, semantic fluency - - TMT, Wisconsin Test, RCPM GBMV SCS (informant report) |

| Viviano et al. [26] USA, Netherlands |

83 participants (51 W:32 M) 35 adults with SCI (22 W:13 M) [68.5] {-} 48 adults without SCI (29 W:19 M) [67.08] {-} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, BFI GDS, BDI - - - - - - WMS - |

| Valech et al. [27] Spain |

68 normal subjects (46 W:22 M) 52 HC (33 W:19 M) [63.87] {11.96} 16 pre-AD (13 W and 3 M) [66.5] {9.56} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE HADS - - BNT, BDAE, Semantic fluency VOSP - TMT A, Stroop test MAT, FCSRT-IR SCD-Q |

| Czornik et al. [28] Austria |

54 subjects with SCD and MCI (28 W:26 M) [66.8] {12.5} 12 SCD 14 aMCI 28 naMCI |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, NTBV - - - - - - - WMT SIMS, SRSI |

| Pérez et al. [29] Spain |

195 participants SCD (121 W:74 M) [65.71] {14.94} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

- - WAIS - Letter semantic, verbal fluency - - TMT A-B, RSCS-BADS, AI-SKT - - |

| Kim et al. [30] Korea |

1442 participants (886 W:556 M) [≥65 years] 1088 HC subjects (642 W:446 M) {5.66} 354 SCC subjects (244 W:110 M) {3.33} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE-KC - - - - - - K-DRS - - |

| Hao et al. [31] China |

615 subjects SCD plus (378 W:228 M) [-] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MoCA - - CDT Fluency Test - - TMT B AVLT-H SCD-Q |

| Esmaeili et al. [32] - |

62 subjects (-) [-] {-} 17 SCC subjects 30 amnestic-MCI subjects 15 HC subjects |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

- - - - - - - ANT - - |

| Garrido et al. [33] Spain |

136 subjects (67 W:59 M) 28 young adults with SCC (17 W:11 M) [21] {-} 37 young adults without SCC (16 W:11 M) [23] {-} 32 older adults with SCC (18 W:14 M) [63] {-} 39 older adults without SCC (16 W:23 M) [65] {-} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE - - RCFT Phonological fluency, Semantic fluency - - TMT A-B, Stroop Test, DST, IGT FCSRT MFE-30 |

| Li et al. [34] China |

201 subjects (105 W and 96 M) 95 AD [68.23] {10.68} 106 FTLD [63.24] {9.93} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

MMSE, MoCA HAMD-21 - - - - - FBI - NPI |

| Oliver et al. [35] USA |

3019 healthy older adults 831 with SCD (635 W:196 M) 2188 without SCD (1660 W:528 M) [73.6] {14.74} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

- - - - BNT NC PM, Line Orientation DST, SDMT, Stroop test WMSR, EBS, WLMR - |

| Morrison et al. [36] Canada |

273 subjects 97 with SCD (36 W:61 M) 176 without SCD (90 W:86 M) [72.97] {16.66} |

Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self / Informant report |

ADAS-13, MMSE, MoCA - - - - - - - - - |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; Buckley, R.F.; van der Flier, W.M.; Han, Y.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Rabin, L.; Rentz, D.M.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Saykin, A.J.; et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, T.M. Subjective cognitive decline, anxiety symptoms, and the risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F. Subjective and objective cognitive decline at the pre-dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 264, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C.; Smith, G.E.; Waring, S.C.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Kokmen, E. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 1999, 56, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, P.G.; Cucarella, J.O.; Maciá, E.S.; López, B.B. Review and update of the criteria for objective cognitive impairment and its involvement in mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Rev. De Neurol. 2021, 72, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.L.S.; Morales, C.T. Revisión del constructo deterioro cognitivo leve: aspectos generales. Rev. De Neurol. 2011, 52, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Beaumont, H.; Ferguson, D.; Yadegarfar, M.; Stubbs, B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandiaran, M. Neuropsicología y diagnóstico temprano. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología. 2011; 46, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begali, V.L. Neuropsychology and the dementia spectrum: Differential diagnosis, clinical management, and forensic utility. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 46, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez A, Slachevsky A, Serrano C. Manual de buenas prácticas para el diagnóstico de demencias. Banco Interamericano de desarrollo. 2020. http://lac-cd.org/2020/06/17/manual-de-buenas-practicas-para-el-diagnostico-de-la-demancia/.

- Mattke, S.; Batie, D.; Chodosh, J.; Felten, K.; Flaherty, E.; Fowler, N.R.; Kobylarz, F.A.; O'Brien, K.; Paulsen, R.; Pohnert, A.; et al. Expanding the use of brief cognitive assessments to detect suspected early-stage cognitive impairment in primary care. Alzheimer's Dement. 2023, 19, 4252–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. , C.P.; V., C.V. Contribución de la neuropsicología al diagnóstico de enfermedades neuropsiquiátricas. Rev. Medica Clin. Las Condes 2012, 23, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnero-Pardo, C.; Rego-García, I.; Llorente, M.M.; Ródenas, M.A.; Carrillo, R.V. Utilidad diagnóstica de test cognitivos breves en el cribado de deterioro cognitivo. Neurol. 2022, 37, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. he PRISMA 2020 statement : an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliacci, M.L.; Scharovsky, D.; Gonorazky, S.E. Deterioro cognitivo leve: características neuropsicológicas de los distintos subtipos. Rev. De Neurol. 2009, 48, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.L.J.; Summers, M.J. Attention and working memory deficits in mild cognitive impairment. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2009, 32, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, C.; Trimarchi, P.D.; Nicolini, P.; Bergamaschini, L.; Vergani, C.; Mari, D. Comparison of Informant Reports and Neuropsychological Assessment in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Am. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Other Dementiasr 2011, 26, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Harten, A.C.; Smits, L.L.; Teunissen, C.E.; Visser, P.J.; Koene, T.; Blankenstein, M.A.; Scheltens, P.; van der Flier, W.M. Preclinical AD predicts decline in memory and executive functions in subjective complaints. Neurology 2013, 81, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, J.B.; Bjerke, M.; Chen, K.; Rozycki, M.; Jr, C.R.J.; Weiner, M.W.; Arnold, S.E.; Reiman, E.M.; Davatzikos, C.; Shaw, L.M.; et al. Memory, executive, and multidomain subtle cognitive impairment. Neurology 2015, 85, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.H.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.H.; Choo, I.H. Altered Executive Function in Pre-Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2016, 54, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfaillie, S.C.; Slot, R.E.; Tijms, B.M.; Bouwman, F.; Benedictus, M.R.; Overbeek, J.M.; Koene, T.; Vrenken, H.; Scheltens, P.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Thinner cortex in patients with subjective cognitive decline is associated with steeper decline of memory. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 61, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, J.; Almklov, E.; Borrie, M.; Wells, J.; Roth, R.M. Subjective rating of executive functions in mild Alzheimer's disease. Aging Ment. Heal. 2016, 21, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, B.; Chang, S.; Lee, D.W.; Cho, M. [P3–535]: ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SUBJECTIVE MEMORY COMPLAINTS AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS IN A COMMUNITY SAMPLE OF ELDERLY WITHOUT COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION. Alzheimer's Dement. 2017, 13, P1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Gallardo ÁM, Muñoz-Bernal LF, Aldana-Camacho LV, et al. Perfil neuropsicológico de un grupo de adultos mayores diagnosticados con deterioro cognitivo leve. Rev Mex Neuroci. 2017, 18(5):2-13.

- Viviano, R.P.; Hayes, J.M.; Pruitt, P.J.; Fernandez, Z.J.; van Rooden, S.; van der Grond, J.; Rombouts, S.A.; Damoiseaux, J.S. Aberrant memory system connectivity and working memory performance in subjective cognitive decline. NeuroImage 2018, 185, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valech, N.; Tort-Merino, A.; Coll-Padrós, N.; Olives, J.; León, M.; Rami, L.; Molinuevo, J.L. Executive and Language Subjective Cognitive Decline Complaints Discriminate Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease from Normal Aging. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017, 61, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czornik, M.; Merten, T.; Lehrner, J. Symptom and performance validation in patients with subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2019, 28, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cordón, A.; Monté-Rubio, G.; Sanabria, A.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Valero, S.; Abdelnour, C.; Marquié, M.; Espinosa, A.; Ortega, G.; Hernandez, I.; et al. Subtle executive deficits are associated with higher brain amyloid burden and lower cortical volume in subjective cognitive decline: the FACEHBI cohort. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, B.; Chang, S.; Lee, D.; Bae, J. Relationship between subjective memory complaint and executive function in a community sample of South Korean elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Gao, G.; Jia, J.; Xing, Y.; et al. Demographic characteristics and neuropsychological assessments of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) (plus). Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, M.; Nejati, V.; Shati, M.; Vatan, R.F.; Chehrehnegar, N.; Foroughan, M. Attentional network changes in subjective cognitive decline. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 34, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Chaves, R.; Perez, V.; Perez-Alarcón, M.; Crespo-Sanmiguel, I.; Paiva, T.O.; Hidalgo, V.; Pulopulos, M.M.; Salvador, A. Subjective Memory Complaints and Decision Making in Young and Older Adults: An Event-Related Potential Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Quan, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cai, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Early-stage differentiation between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobe degeneration: Clinical, neuropsychology, and neuroimaging features. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 981451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, M.D.; Morrison, C.; Kamal, F.; Graham, J.; Dadar, M. Subjective cognitive decline is a better marker for future cognitive decline in females than in males. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.; Dadar, M.; Shafiee, N.; Villeneuve, S.; Collins, D.L. Regional brain atrophy and cognitive decline depend on definition of subjective cognitive decline. NeuroImage: Clin. 2021, 33, 102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, A.; Casey, D.; Arnaoutoglou, N.A. Cognitive tests for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the prodromal stage of dementia: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Initiative, F.T.A.D.N.; Pereira, T.; Ferreira, F.L.; Cardoso, S.; Silva, D.; de Mendonça, A.; Guerreiro, M.; Madeira, S.C. Neuropsychological predictors of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: a feature selection ensemble combining stability and predictability. BMC Med Informatics Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.C.C.; Machado, L.; Bulgacov, T.M.; Rodrigues-Júnior, A.L.; Costa, M.L.G.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Sougey, E.B. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in the elderly? Int. Psychogeriatrics 2018, 31, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongsiriyanyong, S.; Limpawattana, P. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice: A Review Article. Am. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Other Dementiasr 2018, 33, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueper, J.K.; Speechley, M.; Montero-Odasso, M. The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog): Modifications and Responsiveness in Pre-Dementia Populations. A Narrative Review. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2018, 63, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J. Cognitive assessment tools for mild cognitive impairment screening. J. Neurol. 2019, 268, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lario, P.L.; Jiménez, L.A.; Gómez, R.S.; Ustárroz, J.T. Propuesta de una batería neuropsicológica de evaluación cognitiva para detectar y discriminar deterioro cognitivo leve y demencias. Rev. De Neurol. 2015, 60, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G.; Quaranta, D.; Vita, M.G.; Marra, C. Neuropsychological Predictors of Conversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer's Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2013, 38, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, P.; Etcharry-Bouyx, F.; Verny, C. Executive functions in clinical and preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 169, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster-Cordero, F.; Giménez-Llort, L. The Challenge of Subjective Cognitive Complaints and Executive Functions in Middle-Aged Adults as a Preclinical Stage of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, R.; Whitfield, T.; Said, G.; John, A.; Saunders, R.; Marchant, N.L.; Stott, J.; Charlesworth, G. Affective symptoms and risk of progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in subjective cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, T.M. Depression, subjective cognitive decline, and the risk of neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isella, V.; Villa, L.; Russo, A.; Regazzoni, R.; Ferrarese, C.; Appollonio, I.M. Discriminative and predictive power of an informant report in mild cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, M.L.; Dalpubel, D.; Ribeiro, E.B.; de Oliveira, E.S.B.; Ansai, J.H.; Vale, F.A.C. Subjective cognitive impairment, cognitive disorders and self-perceived health: The importance of the informant. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2019, 13, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfel, J.M.; Barnes, L.L.; Capuano, A.; Sampaio, M.C.d.M.; Wilson, R.S.; Bennett, D.A. Informant-Reported Discrimination, Dementia, and Cognitive Impairment in Older Brazilians. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2021, 84, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, R.J.; Langlais, B.T.; Dueck, A.C.; Henslin, B.R.; Johnson, T.A.; Woodruff, B.K.; Hoffman-Snyder, C.; Locke, D.E.C. Personality Changes During the Transition from Cognitive Health to Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terracciano, A.; Luchetti, M.; Stephan, Y.; Löckenhoff, C.E.; Ledermann, T.; Sutin, A.R. Changes in Personality Before and During Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 1465–1470.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.T.; Seward, K.; Patterson, A.; Melton, A.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Evaluation of Available Cognitive Tools Used to Measure Mild Cognitive Decline: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).