1. Introduction

Early reperfusion is the main goal in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Timely reperfusion may prevent the death of ischemic myocytes and reduces microcirculatory damage, and manifestations of the no-reflow phenomenon [[1,2,3,4]. The no-reflow phenomenon is defined as the absence of complete myocardial perfusion at the level of the microcirculatory bed after elimination of the cause of coronary artery occlusion [[4,5,6,7]. Depending on the method of diagnosis, the incidence of no-reflow phenomenon in patients with STEMI is up to 67% according to different sources [

4]. The review by Konijnenberg (2020) proposed a new collective term “coronary microvascular dysfunction”, which combines two main mechanisms of diminished myocardial perfusion in the microcirculatory bed in patients with STEMI after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: manifestations of ischemia/reperfusion injury of the coronary microvasculature and embolization of the distal coronary artery by thrombus fragments and atherosclerotic plaque components [

6].

A distinction is made between primary (early) no-reflow, which is caused by a prolonged period of myocardial ischemia with a low level of residual blood flow (subendocardial and intramural layers), and secondary no-reflow, which is caused by ischemia-reperfusion injury and is manifested by a progressive deterioration of myocardial perfusion in areas of restored blood flow [

1,

8,

9]. The main mechanism of primary and secondary no-reflow is endotheliocyte edema, which occurs at the stage of myocardial ischemia and worsens with the restoration of blood flow [

9,

10]. Electron microscopic evidence suggests that intracellular swelling of cardiomyocytes and endotheliocytes occurs during ischemia and results in protrusion of cell membranes [

9,

11,

12]. Although endotheliocytes are more resistant to ischemic injury, with prolonged ischemia, swelling endotheliocytes develop membrane blebs (membrane-bound bodies), the size of which depends on the duration of ischemia. With prolonged ischemia, intracellular edema leads to complete occlusion of the microvascular lumen and to the appearance of primary no-reflow, the pathomorphologic sign of which is coagulation necrosis [

1,

9]. In case of moderate damage to endotheliocytes, reperfusion injury additionally increases edema of endotheliocytes, cardiomyocytes and intercellular space, leading to extravascular compression of microvessels and occlusion of their lumen with formation of blood stasis and delayed no-reflow [

4,

7].

During ischemia, conditions of increased microvascular permeability are established; therefore, intercellular edema forms from the moment of restoration of blood flow. Ischemia, reactive oxygen species, as well as histamine, thrombin, and other active substances produced during reperfusion activate myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which leads to endothelial contraction, disruption of intercellular contacts, and a sharp increase in vascular permeability [

13,

14]. This results in myocardial edema and hemorrhage [[4,5,6,7,15]. According to literature data, mice with genetic knockout of 210 kDa MLCK as well as wild type mice treated with a small-molecule MLCK inhibitor are more resistant to lung injury in experimental models of sepsis due to preservation of microvascular endothelial barrier function [

16]. This evidence suggests that pharmacological inactivation of MLCK may be beneficial for attenuation of cardiac tissue edema and reperfusion injury.

A promising antiedematous drug for adjuvant therapy of myocardial infarction is a novel proteolytically stable peptide inhibitor of MLCK, PIK7, designed at the National Medical Research Center of Cardiology Named after Academician E.I. Chazov, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation [

17]. Given the known role of increased vascular permeability in the no-reflow phenomenon and the possible benefit of MLCK inhibition [

18], we investigated the effect of PIK7 on coronary vascular permeability and no-reflow-limiting efficacy in

in vivo model of ischemia and reperfusion of rat myocardium.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of PIK7 on the vascular permeability in the no-reflow zone in the rat model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Thioflavin S was used to map the boundaries of the no-reflow zone, and a modified Miles test using indocyanine green [

19] instead of Evans blue was used to assess the severity of increased vascular permeability in the risk zone.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was performed on male Wistar rats of the SPF category (age 16-20 weeks, weight 350-400 grams, Novosibirsk nursery) in accordance with the protocol approved by the Commission for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Almazov National Medical Research Centre (PZ_23_6_Sonin_DL_V3, 06.14.2023).

Modeling of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion

The study used an in vivo model of regional ischemia-reperfusion of the rat myocardium. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane gas anesthesia with constant monitoring and maintenance of body temperature 37 ° C ± 0.5 ° (ATC1000-220, World Precision Instruments, Inc., USA). Rats underwent tracheostomy and artificial lung ventilation (CWE-SAR-830/AP, World Precision Instruments, Inc, USA) with a gas mixture with 60% oxygen (respiratory rate - 60/min, respiratory volume - 3 ml/100 g body weight). Artificial ventilation was regulated by repeated analyses of arterial blood gases throughout the experiment (Analyzer i-STAT® System, Abbot, USA). Arterial blood was taken from the right common carotid artery through a catheter (PE-50 polyethylene tube, Intramedic, USA) connected to a sensor (Baxter, USA) for measuring blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) using PhysExp software (Cardioprotect LLC, Russia). Femoral vein catheterization was performed for infusion of the tested solutions and dyes.

The chest was opened by an incision in the fourth intercostal space to induce regional ischemic reperfusion injury. The ribs were bred to expose the heart, then the pericardium was opened and a 6.0 polypropylene ligature with an atraumatic needle was inserted under the main branch of the left coronary artery, approximately 2 mm from its beginning [

37]. The ends of the ligature were passed through an occluder – a small polyethylene tube ~ 7-8 cm (PE-90, Intramedic, USA) and brought out. Myocardial ischemia was initiated after the end of surgical procedures and a 30-minute stabilization period. Reversible myocardial ischemia was created by shifting the occluder down the ligatures and applying a surgical clamp to the occluder to prevent it from shifting backwards. Hemodynamic parameters were recorded immediately before the 30-minute occlusion, 5 and 15 minutes after occlusion, at the beginning of reperfusion (at the 5th minute) and then every 30 minutes until the end of the experiment.

A solution of indocyanine green (ICG) at a dose of 1 mg/kg (Pulse Medical Systems, AG, Germany) was injected in rats intravenously for assessing the severity of vascular permeability in the myocardial infarction zone in the first minutes of reperfusion (ICG0’) or at the 90th minute of reperfusion (ICG90’). ICG was dissolved in distilled water, then NaCl was added to the ICG solution to obtain a NaCl concentration of 0.9% and a final ICG concentration of 2 mg/ml and administered in 1 minute in a volume of 0.5 ml.

A solution of 4% thioflavin S (ThS) in 0.9% NaCl solution in a volume of 0.7 ml was bolus injected at the end of the 2-hour reperfusion period, 15 seconds before heart excision to measure the size of the no-reflow zone.

Pharmacological substances

PIK 7 and sodium nitroprusside (Naniprus, Sopharma) were diluted in 0.9% NaCl solution immediately before injection and injected intravenously separately (without mixing with each other). The basic dose of PIK7 2.5 mg/kg used in this study was comparable to PIK7 concentration effective in experiments with cultured endothelial cells - 100 uM [

17]. Given the volume of circulating blood in rat 55-70 ml/kg, we estimated peak concentration of PIK7 in blood following its bolus i/v administration as approximately 50 uM. Additionally, a higher dose of PIK7 was used (40 mg/kg) to probe dose-efficacy relationship. This higher dose of PIK7 was non-toxic based on previous rodent data [

17].

The rate of intravenous injection of sodium nitroprusside was regulated by the blood pressure limit, so that during its injection it was in the range of 40-50 mmHg [

20].

Exclusion criteria: SAD <50 mmHg and/or heart rate <300 at any time during the experiment.

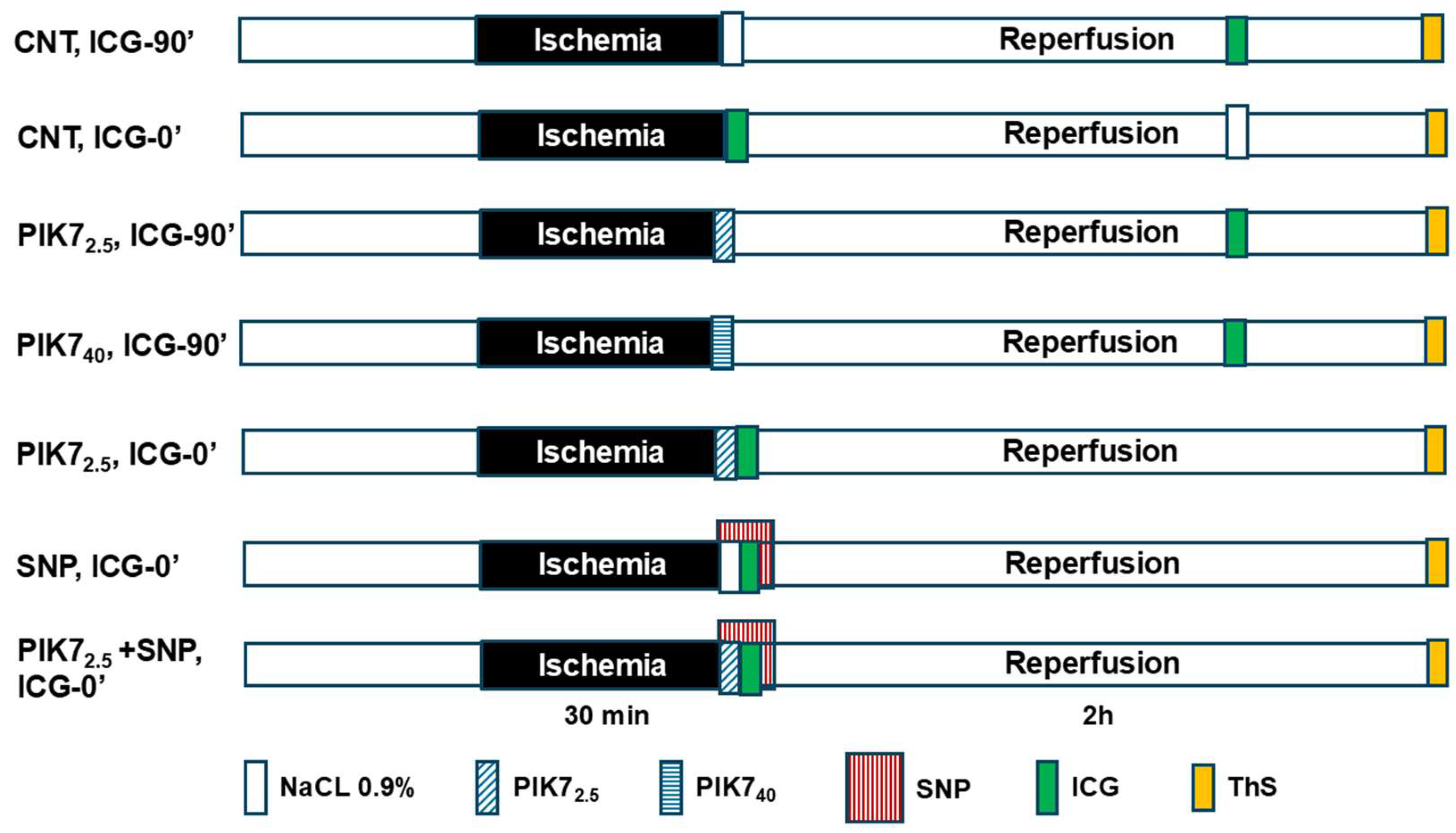

Figure 1 shows the protocol of the experimental study.

1. In the «CNT, ICG90’» group, 30-minute ischemia and 120-minute reperfusion were created; a bolus of ICG solution was injected intravenously for 1 min at the 90th minute of reperfusion. Bolus ThS was intravenously injected 10 seconds before the excision of the heart (n = 9).

2. The protocol of the «CNT, ICG0’» group is identical to the protocol of the «CNT, ICG90’» group, except that the ICG solution was intravenously injected during 1 minute of reperfusion (n=7).

3. The protocol of the «PIK7 2.5, ICG90’» group is identical to the protocol of the «CNT, ICG90’» group, except that 30 seconds before the end of ischemia, an intravenous solution of PIK7 was injected at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg for 1 minute (n=7).

4. The protocol of the «PIK7 40, ICG90’» group is identical to the protocol of the «PIK7 2.5, ICG90’» group, except that PIK7 was injected at a dose of 40 mg/kg (n=7).

5. The protocol of the group «PIK7 2,5, ICG0’» is identical to the protocol of the «PIK7 2,5, ICG90’» group, except that ICG was injected in the first minute of reperfusion immediately after the injection of PIK7 (n=3).

6. The protocol of the «SNP, ICG0’» group is identical to the protocol of the «CNT, ICG0’» group, except that intravenous injection of sodium nitroprusside solution began 30 seconds before the end of ischemia, and ICG solution was injected into another femoral vein within 1 minute of reperfusion (n=6).

7. The protocol of the «PIK7 2.5+SNP, ICG0’» group is identical to the protocol of the «CNT, ICG0’» group, except that intravenous injection of two solutions was started 30 seconds before the end of ischemia: sodium nitroprusside at a dose of 60 µg/kg and PIK7 at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg followed by injection of ICG (n=10).

Visualization of ischemic reperfusion injury ex vivo

The left coronary artery was re-occluded at the end of the experiment (after 2 or 120 minutes of reperfusion), after which 2.5 ml of 2.0% Evans Blue (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, California) was injected through the femoral vein to identify the risk zone. The hearts were cut out and cut into five slices 2 mm thick parallel to the atrioventricular sulcus. The basal surface of each slice was photographed using a digital camera. The slices were immersed in a 1% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, ICN Pharmaceuticals, USA) at a temperature of 37 °C (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes and photographed again to identify the infarction area and register the fluorescence area and ICG intensity. The images were analyzed using ImageJ (

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij /). The risk area (Evans-negative area) was expressed as a percentage of the entire section, and the area of the myocardial necrosis zone (TTC-negative areas) was expressed as a percentage of the risk area. The values of the risk area and the infarction area for each heart were obtained by summing the data for the slices and calculating the average values.

Methods of fluorescence registration

Registration of ICG fluorescence in the near-infrared range (820-900 nm) under excitation with radiation of 780-810 nm was carried out using a specially developed optical imaging system for the near-infrared fluorescence range [

19,

38]. It includes a diode laser with a wavelength of 808 nm, providing excitation of infrared fluorescence, and a multispectral video system.

A tube illuminator was used for visualizing ThS fluorescence, in which a short-arc mercury lamp HXP 120VIS Osram, with a power of 120 watts, was used as a light source. The radiation was selected by switchable light filters (in this case, a bandpass filter with a central wavelength of 390 nm, a width of 40 nm, FF01-390/40-25) and a liquid light guide for radiation delivery. Image registration was carried out using a multispectral shooting system based on a highly sensitive RGB television matrix.

Comparison of ICG and ThS fluorescence intensity in the zone of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury

The obtained images with ICG and ThS fluorescence were evaluated using Image Pro Plus programs. To study the nature of the intensity of ICG and ThS fluorescence, a grid was drawn on the images of the risk zone of the second and third slices from apex of the heart, the number of sectors and cells of which were the same and tied to the boundaries of the risk zone (Figure 8b). The grid formed in this way was then transferred to images of slices stained with TTC, and with ICG and ThS fluorescence.

The grid allows compare the intensity of ICG and ThS fluorescence in the same section, as well as to find the dependence of the boundaries of increased vascular permeability with the zones of necrosis and no-reflow. The area of interest (ROI) was allocated in each cell in the area at risk (AAR) and in each cell of the reference sector. Then, within the selected ROI, the average value of the fluorescence intensity was calculated, which was expressed in conventional units (a.u.). To compare the fluorescence intensity between any cell in the AAR with an intact zone, the corresponding cell in the reference sector in the interventricular septum equidistant from the boundary sectors of the AAR was selected.

The quantitative comparison was carried out using the contrast parameter, subtracted by the formula: contrast=(ROIaar-ROIref)÷ROIref, where ROIaar is the average value of the fluorescence intensity in a cell in AAR, ROIref is the average value of the fluorescence intensity in a cell in the reference zone. Before measuring contrast, the average value of background fluorescence measured at five randomly selected points around the measured slice was subtracted from the average values of fluorescence intensity [

19].

Comparison of no-reflow zone sizes based on ICG and ThS fluorescent images

To calculate the no-reflow zones, planimetric imaging of cardiac sections was performed in the ImageJ program. For measurement of area of the no-reflow zone, boundaries were outlined in ICG and ThS fluorescence images. The boundaries of the no-reflow zones were delineated by the peaks of ICG or ThS fluorescence, within which the outer zone with the maximum level of vascular permeability and the inner, non-fluorescent region are located.

UHR ECG registration and signal processing

The original method of reliable electrocardiographic control of ischemia appearance in investigations with experimental animals was used for continuous electrocardiogram monitoring and control of ischemia and reperfusion onset [

39,

40]. The ECG SVR method aims to study the fine structure of electrocardiac signals (ECS) and reveal additional meaningful diagnostic information for early detection of electrophysiologic changes in the heart caused by ischemia.

Myocardial histology

The heart samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 hours. Next, the material was dehydrated and impregnated with paraffin according to the generally accepted standard procedure. For histological analysis, sections with a thickness of no more than 5 microns were made, followed by trichromic staining using the Mallory method (BioVitrum, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation). Morphometry of 5-µm sections was used to quantify stasis regions (areas occupied by erythrocytes) using a Nikon Eclipse Ni-U optical microscope, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 200× magnification and the NIS-Elements BR 4.3 computer program (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Stasis areas (target area) in the intramural layer of the risk area (total area 3 mm2) were detected using the ImageJ Color threshold tool. The percentage of the target area was calculated using the formula: (target area /total area) × 100%.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

For electron microscopic examination, pieces of tissue with a thickness of 1.0–1.5 mm were prefixed in a mixture of 0.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde cooled to 4 ° C, diluted with 0.1 M cacodilate buffer (pH 7.2–7.4). It was fixed in a 1% solution of osmium tetrachloride (all reagents are Sigma–Aldrich, USA) cooled to 4 ° C after 1.5–2.0 hours. The material was dehydrated in solutions of ethyl alcohol of ascending concentration and absolute acetone. During dehydration, the tissue was contrasted with a 3.5% solution of uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol. Impregnation and filling with a mixture of araldites (Fluka, Switzerland) with sample orientation was performed under a magnifying glass. Polymerization was carried out in a thermostat at 37 ° C and 60 ° C during 3 days. Ultrathin sections (50-60 nm) were prepared using the LKB-III ultratome (LKB, Sweden). The registration of changes in the structure of tissues and their photofixation were carried out on transmission electron microscopy FEI Tecnai G2 Spitit BioTWIN (FEI Company, the Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV, provided by the Center for Collective Use of the Sechenov Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry of the RAS and on the transmission electron microscope HITACHI 7800 (Japan), provided by the Center for Preclinical and Translational Research of the Almazov National Medical Research Center.

Statistical analysis

The median of both the 25th and 75th percentiles [Me (25; 75%)] was used to describe features with a different distribution from the normal one. The T criterion (Wilcoxon paired criterion) was used to assess the reliability of differences before and after exposure. The U criterion (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney criterion) was used to assess the reliability of differences between two conjugate aggregates. Statistical data processing was carried out using the GraphPad Prizm 6 program.

3. Results

Effect of PIK7 and SNP on systemic hemodynamics

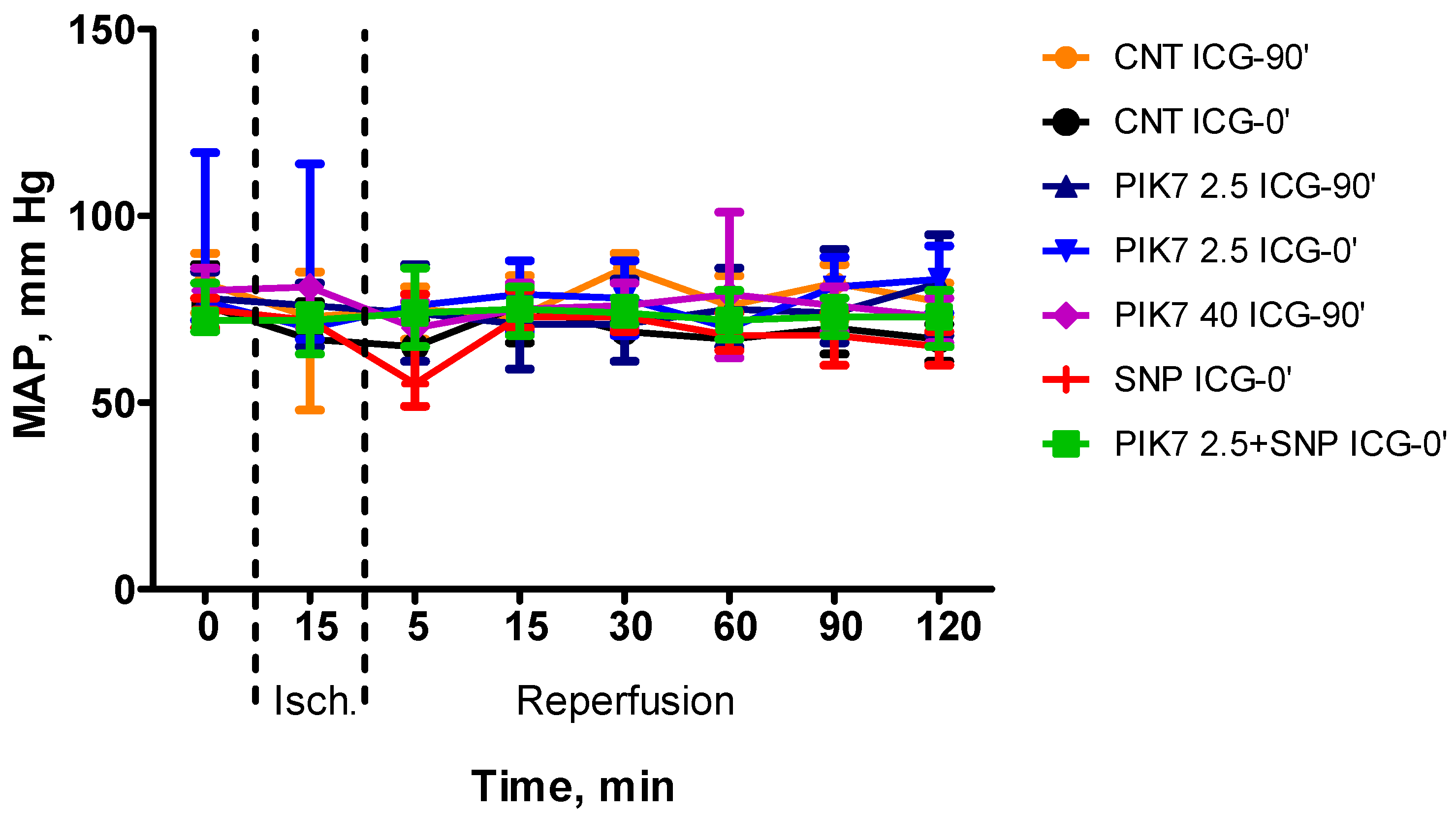

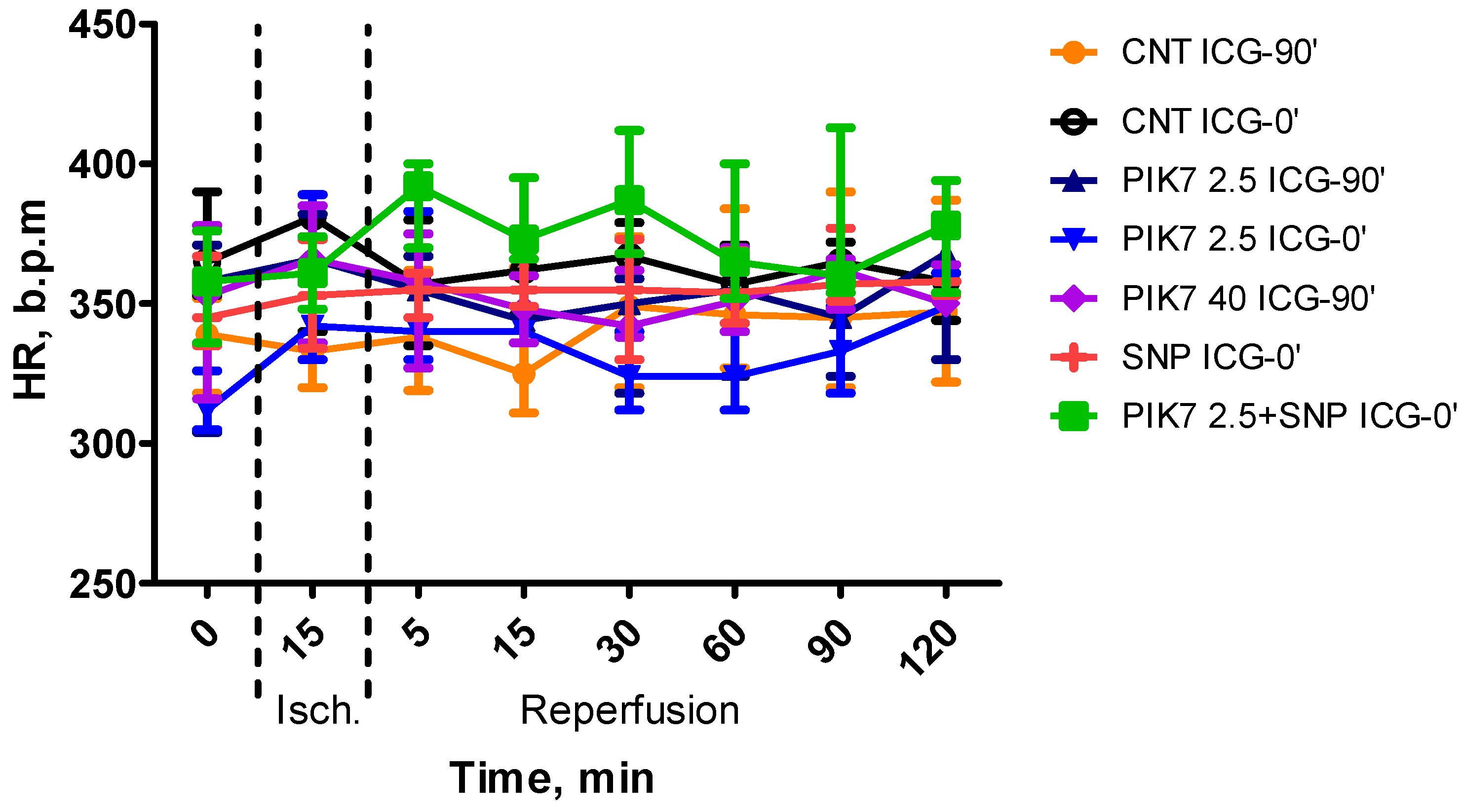

During the whole experiment, blood pressure and heart rate levels did not differ between the groups (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), except for the first minutes of reperfusion, when a short-term decrease in mean arterial pressure was observed after the end of PIK7 injection. Reaching its minimum, at 1-2 minutes after the end of PIK7 infusion (

Figure 4), mean BP gradually recovered within 3 to 5 minutes. This decrease was dose-dependent and resulted in a 25% [17.25-27.21] (p=0.0355) decrease in mean BP in all rats in the high dose PIK7 group (40 mg/kg) and only in three rats in the 2.5 mg/kg PIK7 group (ICG-90’).

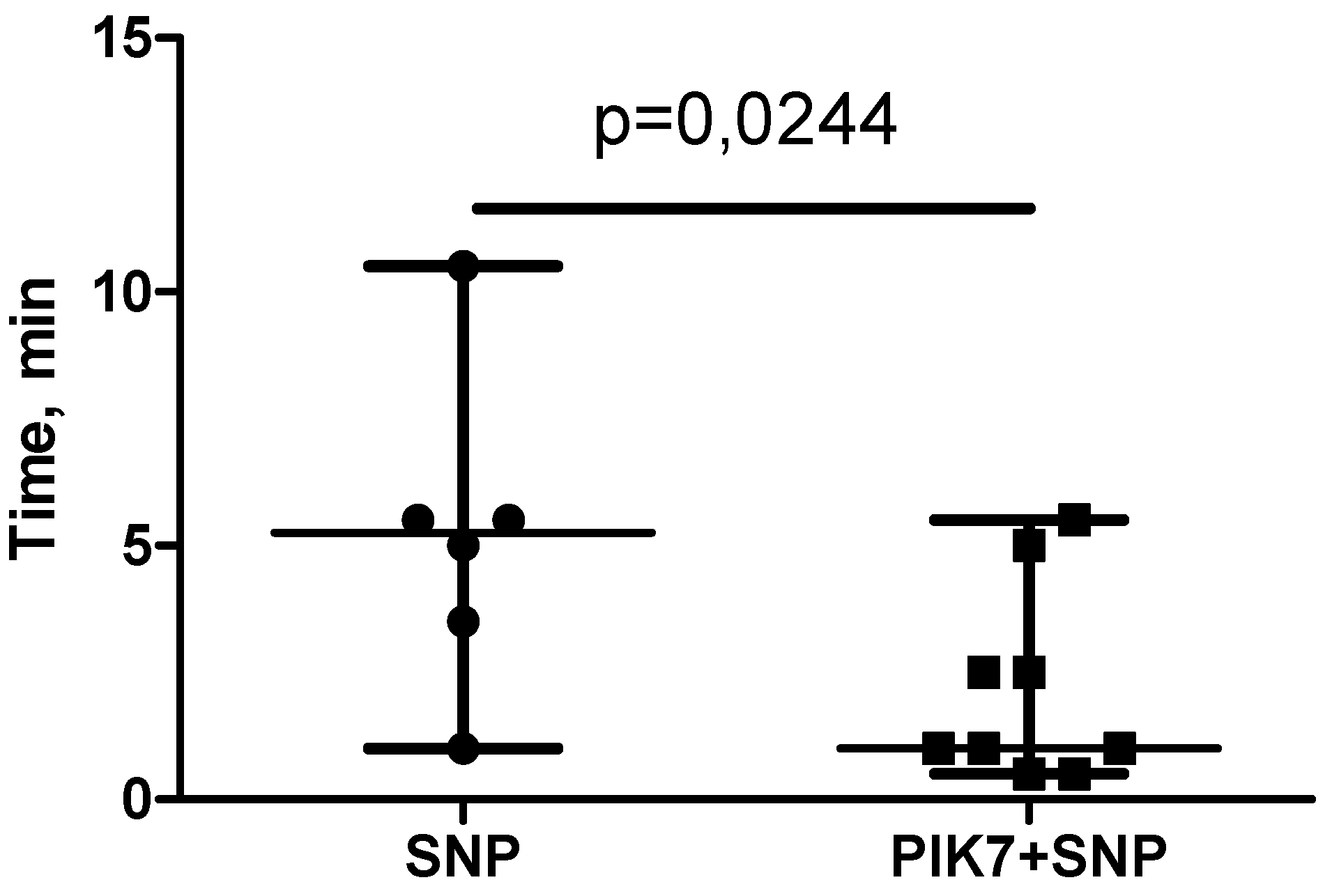

Although the dose (60 μg/kg) and volume (0.5 mL) of SNP were similar in the SNP and PIK7+SNP groups, the time of SNP administration was shorter in the SNP+PIK7 group. SNP in these groups was administered intravenously and continuously at a rate to achieve and maintain mean BP between 40-50 mmHg. To maintain the target BP in the PIK7+SNP group, a higher injection rate of SNP solution was required than in the group without PIK7. Due to the increased rate of SNP administration in the PIK7+SNP group, the time of its administration was significantly shorter than in the SNP group (

Figure 5).

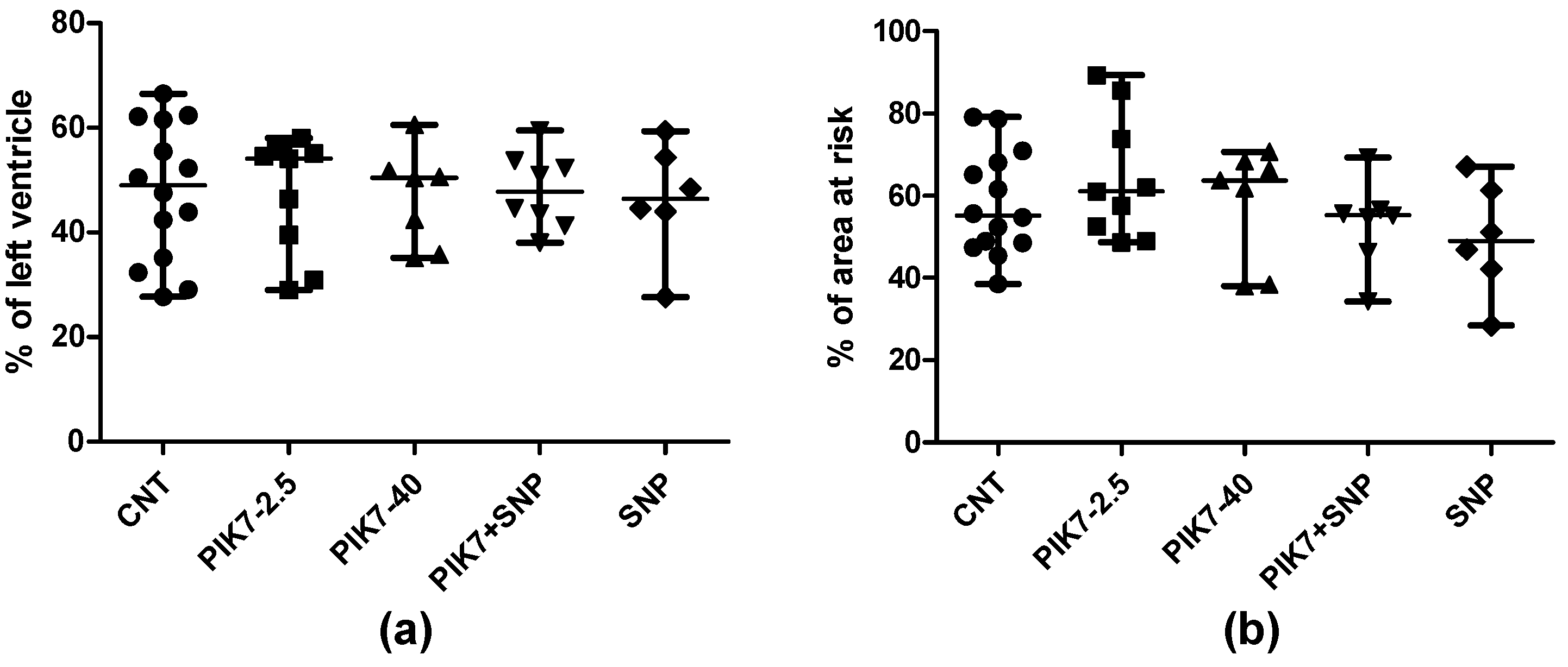

Myocardial infarction size

PIK7 administration had no effect on myocardial infarction size (

Figure 6). There were no significant differences in the area of risk zone between the groups. Also, there were no differences between the groups in the dynamics of the decrease in T wave amplitude at the 60th minute and 120th minute of reperfusion. In all experiments, a significant decrease in the spectral power density of the UHR ECG was recorded in the first minute of coronary artery occlusion which confirms the onset of myocardial ischemia. There were no differences in the spectral power density between the groups at all recording points.

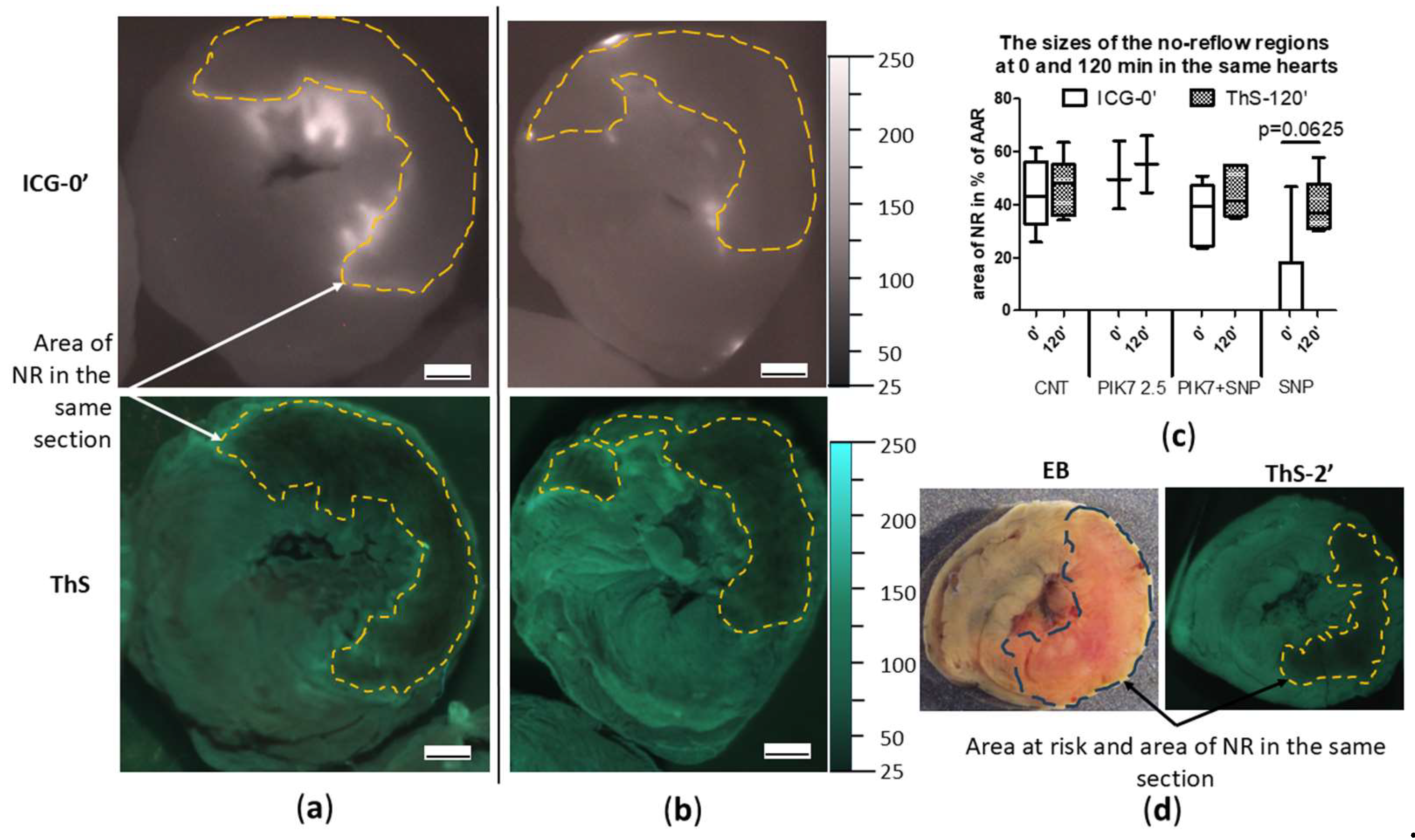

Size of no-reflow zones

Areas of “true”no-reflow immediately after reperfusion was detected by early ICG administration (ICG-0’), which was expressed in the absence or pronounced reduction of ICG accumulation in the intramural layer of the necrosis zone with intensive ICG retention in the subepicardial, subendocardial layers and border zones (

Figure 7a-7d). In representative cross-sectional images of control and PIK7-2.5 hearts, dashed lines indicate areas of primary no-reflow. To confirm the phenomenon of primary no-reflow detected using ICG, in one pilot experiment we used Thioflavin S (ThS), fluorescent vital dye staining the endothelium [

11]. ThS was intravenously injected into the rat at the second minute of reperfusion after 30-min ischemia and one minute before the rat was euthanized (ThS-2’). The result of this experiment confirmed the presence of primary no-reflow (

Figure 7d). On the left side of

Figure 7d is an image of a transverse apical slice of a heart stained with Evans blue (EB), where the dotted line delineates area at risk zone, which size in this heart was 50% of the left ventricular volume. On the right side of

Figure 7d is an image of the same slice in UV light, where the dotted line outlines the zone of primary no-reflow, the size of which in this heart was 55% of the risk zone, which is comparable to the size of the necrosis zone in the control group – 55% [48;69] (n=14). That indicates a pronounced blood flow disturbance in the first minutes of reperfusion in the central area of the risk zone that occupies about half of its total area. The area of the no-reflow zone measured by ICG-fluorescence imaging method almost did not change in its size during reperfusion (

Figure 7c) and was 45.7% [27.3;53.1] in the control group in the first minutes (ICG-0’) and 44.2% [35;54.2] at the end (ICG-90’).

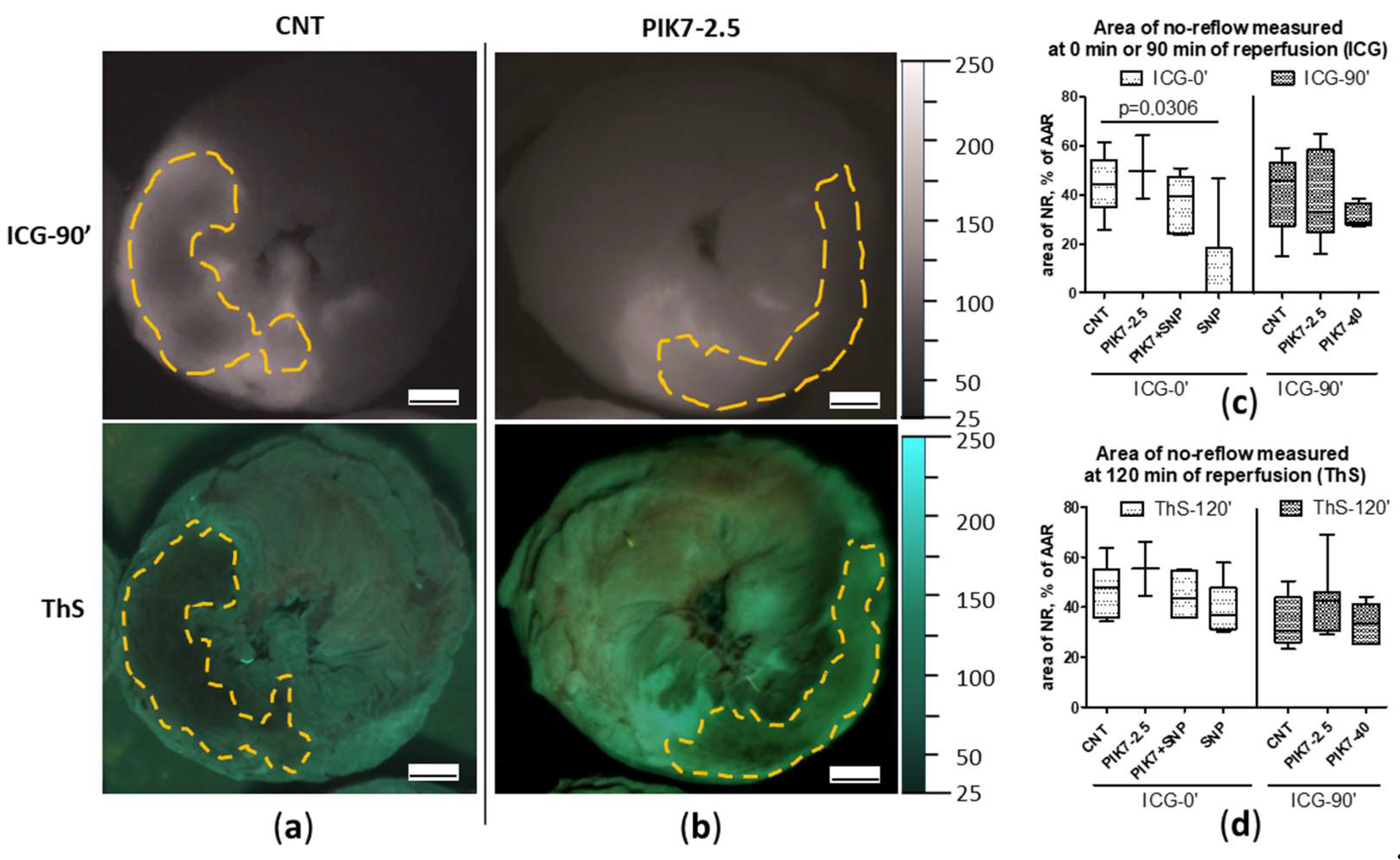

PIK7 administration did not affect the size of both the primary no-reflow area and the no-reflow area at the end of reperfusion (

Figure 7c,

Figure 8a-8d).

According to the original study plan, rats from the PIK7 group with early administration of ICG (ICG-0’) were to be compared with the control group (CNT, ICG-0’). However, early analysis of the data obtained in the beginning of the study revealed that early no-reflow occupies 4/5-5/6 of necrosis zone. We decided to change the original study plan and introduce two additional groups with sodium nitroprusside (SNP and SNP+PIK7) using rats from the PIK7-2.5 ICG-0’ group leaving only three rats, due to the redistribution of rats into two new groups.

Intravenous administration of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) during the first minutes of reperfusion resulted in a reduction or disappearance of the boundaries of the primary no-reflow zone recorded during early ICG administration (no-reflow area = 0% [0; 18]) (

Figure 8c), whereas its co-administration with PIK7 at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg (PIK7+SNP) abolished this effect of SNP on the size of the primary no-reflow area 39.4% [24.4; 47.2] (

Figure 8c).

After 2 hours of reperfusion, the size of the no-reflow zones did not differ between groups (

Figure 7c,

Figure 8c).

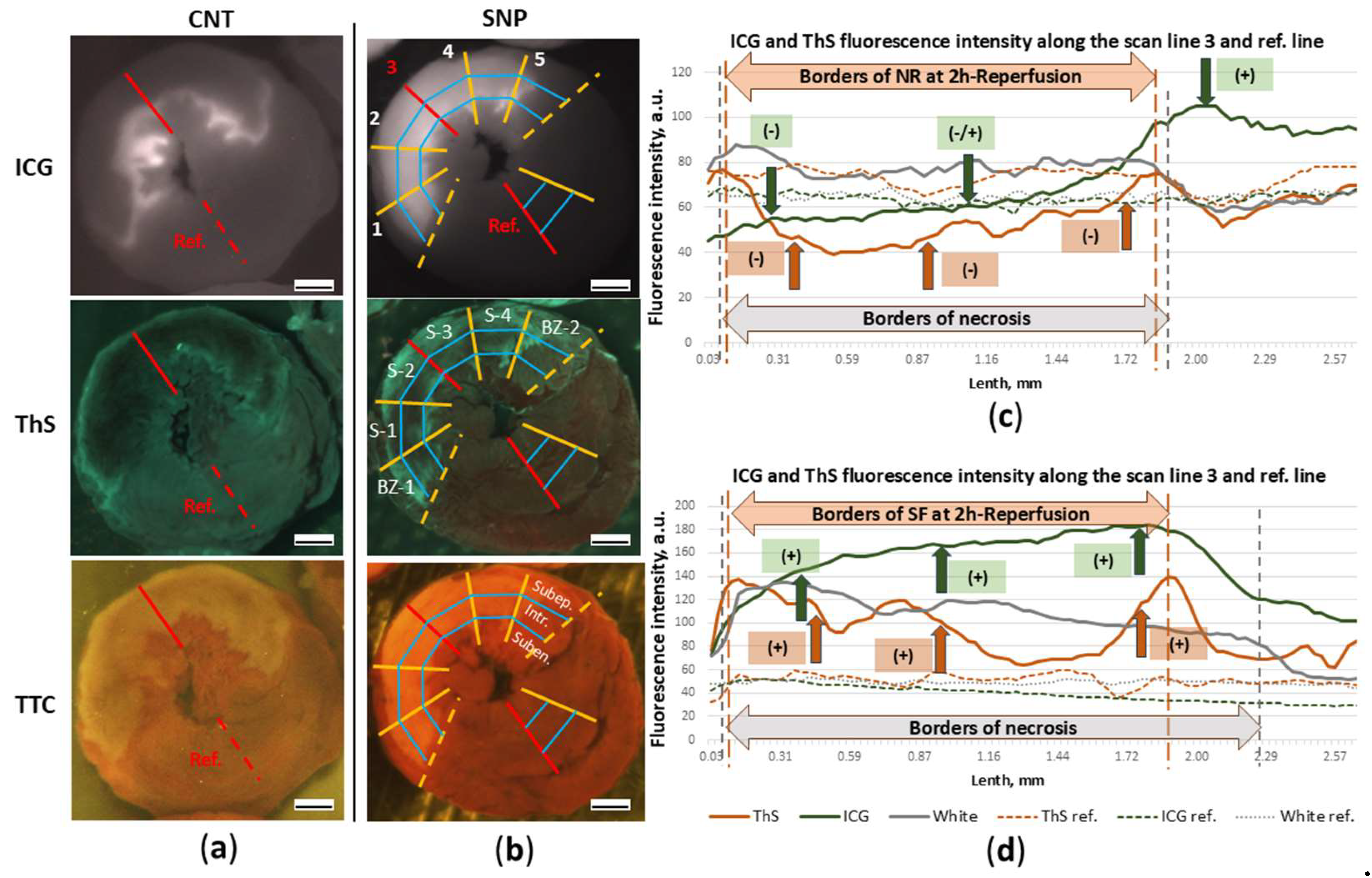

ICG- and ThS-fluorescence intensity

Figure 9a and 9b show images of transverse apical slices of hearts in the light of ICG- and ThS-fluorescence, from which graphs of the ICG and ThS fluorescence intensity were drawn along the central scanning lines (3 scan line) from the epicardium to the endocardium and reference lines (

Figure 9c, 9d). The graphs allow compare the distribution pattern of ICG-0’ and ThS in different layers of injured myocardium in the cross section of the left ventricular wall and fluorescence intensity of ICG-0’ and ThS in the control heart and the heart with SNP. By the threefold enhancement of ICG-fluorescence intensity (green line) compared with the reference level (dashed green line), it is evident that SNP significantly enhanced fluorophore accumulation during the first minutes of reperfusion. Intensification of ICG-fluorescence intensity against the reference-line (the background) of SNP action is marked on the graph by green arrows with positive “+” signs (positive contrast). In the control heart in the subepicardial layer of the injured zone ICG accumulation is lower than the reference level and is marked by negative sign “-” (negative contrast). In the intramural layer the level of ICG-fluorescence fluctuates between negative and positive contrast compared to the reference one, which indicates a low level of ICG accumulation in these layers of the damaged zone.

After two hours of reperfusion in the SNP rat, despite the increased vascular permeability in the injury zone during the first minutes of reperfusion, the intensity of ThS-fluorescence is higher (orange line) than in the reference zone (

Figure 9d). In the control experiment, in the same zone, the intensity of ThS-fluorescence is lower than in the reference zone (

Figure 9c). Consequently, SNP-induced short-term increase in blood flow in the injury zone, followed by an increase in vascular permeability at the beginning of reperfusion, does not reduce blood flow after two hours in the necrosis zone, leading to slow flow (SF) in infarct zone in some rats instead of no-reflow (

Figure 9d).

To evaluate the effect of PIK7 on vascular permeability and severity of microvascular obstruction, we compared the intensity of ICG- and ThS-fluorescence in the risk zone in each grid cell (

Figure 9b) of each heart in apical and middle slices (

Figure 10a-c). To compare the fluorescence intensities of the two fluorophores, we used the parameter “contrast”, which reflects the ratio between the fluorescence in the examined (injured) myocardial zone and the reference (remote) zone, which was calculated using a formula after subtracting the background fluorescence values (see Materials and methods). The contrast value is directly proportional to the fluorescence intensity in ROI, and its negative values occur when the fluorescence intensity of ROI decreases below the fluorescence intensity of reference zone.

Comparison of contrast of ICG-fluorescence intensity between sectors in the intramural layer of ICG-0’ groups

Comparison of contrast between the border and central sectors in the case of early ICG administration showed no differences in all groups. There were also no contrast differences between the PIK7-2.5 groups and the control group. ICG-fluorescence intensity levels were higher in the SNP group compared with the control group, particularly in the first inner sector (S-1) in the subepicardial (4.86 a.u. [1.46; 18.90] vs 0.67 a.u. [0.17; 0.97]) and intramural (6.15 a.u. [2.00; 14.76] vs 0.97 a.u. [0.67; 1.91]) layers (

Figure 10a). This indicates that SNP-induced enhancement of coronary blood flow in the entire risk zone, including the primary no-reflow area, resulted in pronounced hyperpermeability, a significant increase in ICG accumulation in the intramural layer leading to increase in its fluorescence intensity, especially in the S-1 sector, and a decrease in the primary no-reflow area (

Figure 7c).

Figure 10(c) and 10(d) show higher ThS fluorescence contrast value in central sector of apical slice and in central and border sectors in middle slice although these differences were not statistically significant. This suggests that in some rats, blood flow in the intramural layer and border sectors was preserved (slow flow) in the second hour of reperfusion, and there was increased vascular permeability in these areas. Fluorescence peaks at the edges of the necrotic zone indicate preserved blood flow and increased fluorophore accumulation.

Intravenous co-administration of SNP with PIK7 at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg partially reversed the hemodynamic effect of SNP at a dose of 60 µg/kg (

Figure 4,

Figure 5), accompanied by a two- to threefold decrease in ICG-0’ fluorescence intensity in all sectors, compared with the SNP group (

Figure 10a); there were also no differences in the size of the primary no-reflow area between the SNP+PIK7 and CNT groups (

Figure 8c).

Analysis of ThS-fluorescence in the PIK7 40 group revealed a slight decrease in contrast in the mid-slice at the edges of the no-reflow zone and a significant decrease in contrast in the first border zone (BZ-1) to -0.45 a.u. [-0.65;-0.18] vs. 0.44 a.u. [-0.43;0.92] in the control group (

Figure 9d), whereas comparison of the fluorescence intensity of ICG administered at 90 minutes (ICG-90’) showed no significant differences between the same groups of rats.

The severity of blood stasis

The absence of significant differences in the severity of microvascular obstruction is confirmed by the results of planimetric analysis of histologic transverse sections of hearts stained with Mallory trichrome. Thus, the area occupied by erythrocytes (stasis) in the control group was 11.1% [5.2; 13.6], and 9.7 [6.1; 11.9] and 10.1% [2.2; 13.8] in the PIK7-2.5 and PIK7-40 groups, respectively. In the two SNP groups, the area occupied by erythrocytes was also comparable to the control group: 12.3% [9.3; 15.4] in the SNP group and 14.6% [8.8; 17.8] in the SNP+PIK7 group. The area occupied by red blood cells in the remote zone did not exceed one percent.

Electron microscopy data

Ultrastructural signs of ischemia/reperfusion injury are shown in

Figure 11. Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe samples of the intramural layer of the necrosis zones after 30-min ischemia and 10-min reperfusion in control rat and rat injected with PIK7 2.5 mg/kg. Signs of irreversible damage of cardiomyocytes were visible in samples from rat with PIK7 2.5 and were obvious in control rat. In samples from the control rat we found marked mitochondrial edema, flakes, cristae separation and ruptures of the outer mitochondrial membrane, as well as vacuolization (

Figure 11a), intercellular edema and lipid spots were detected, indicating irreversible damage to the cardiomyocyte. The same signs of irreversible damage were seen in almost all cardiomyocytes in the sample from PIK7-2.5 heart, however, mild to moderate mitochondrial swelling was more commonly observed in the experimental sample (

Figure 11b). Mean mitochondrial area of the experimental sample was 0.71±0.02 μm

2 (n=145), which was half that of the control group: 1.43±0.06 μm

2 (n=282).

Although we found a few erythrocytes outside the capillaries (extravasation) in the control and experimental samples, there were a few cases of gap formation with separation of endotheliocytes (

Figure 11c) in the control group and none in the experimental sample. At the same time, there were signs of no-reflow phenomenon in two samples, such as a severe degree of endotheliocyte edema leading to complete obturation of the capillary lumen by membrane bulges (protrusions,

Figure 11d) and membrane-bound blebs extending into the capillary lumen. A quarter of capillaries in the control sample had normal outlines and isolated cases of spasm, and more than half of the capillaries had blood cells in the lumen. In contrast to the control sample in the experimental sample one third of capillaries had narrowed lumen due to more active tone.

4. Discussion

Ultrastructural alterations of the microvasculature caused by ischemia-reperfusion injury begin to form during ischemia [

12]. The experiments on dogs have shown that prolonged ischemia cause intracellular edema with appearance of membrane-bound blebs on the luminal surface of endotheliocytes, which partially or completely obturate the capillary lumen [

9,

12,

21]. The initial area of their appearance during ischemia is the center of the risk zone with low levels of residual blood flow and oxygen. When blood flow is restored in such areas, flow slows down or is not restored due to the development of primary (early) no-reflow [

9]. Obviously, it is possible to prevent or reduce the manifestations of primary no-reflow by timely reperfusion. The second stage of edema formation starts with reperfusion and is associated with myocardial reperfusion injury, during which intracellular edema increases and interstitial edema begins to form [

9,

22]. The interstitial edema is driven by two processes that happen simultaneously during reperfusion: the increased vascular permeability [

6,

22,

23] and decrease in myocardial lymphatic outflow from the injured myocardium [

24]. Increased vascular permeability cause microvascular leakage, which is considered as therapeutic target for ischemia and reperfusion injury [

25]. Reperfusion-induced interendothelial cellular gap formation is mediated by increasing activity MLCK [

14,

18,

26]. This fact prompted us to study the effectiveness of a new MLCK inhibitor PIK7 [

17] in a model of myocardial infarction in rats to evaluate its microvascular hyperpermeability counteracting effect and its capacity to limit no-reflow condition.

For the first time, using early ICG administration we have detected early no-reflow in rats after 30-min regional myocardial ischemia. In the circulation, ICG binds to albumin and high- and low-density lipoproteins, allowing its use as a marker of increased vascular permeability, since intact vascular endothelium is “impermeable” to albumin [

13,

27]. ICG-fluorescence images of control rats show that injected during the first minutes of reperfusion ICG accumulates only at the edges of the necrosis zone, where its maximum fluorescence intensity is observed. This indicates the highest vascular permeability at the edges of the necrosis zone, while the center of the necrosis zone in the intramural layer remains dark relative to the edges. Insufficient intensity of ICG-fluorescence in the center of the necrosis zone can be explained both by the absence of blood flow in this area and by the absence of increased vascular permeability in the center of the necrosis zone in conditions of low oxygen content and activators of endotheliocyte contraction triggering paracellular transport. Electron microscopy data of myocardial samples taken from the center of the necrosis zone of control and experimental rats at 10 minutes of reperfusion confirm the assumptions made based on ICG-fluorescence image analysis. In the center of the intramural layer of the risk zone, membrane-bound blebs within the capillary lumen were detected, which partially or completely obturated the lumen. This is likely related to endotheliocytes swelling during ischemia due to ionic transport dysregulation. In few fields of view, there was erythrocyte diapedesis, and in the control rat there were only single cases of endothelial intercellular gap formation.

Earlier in experiments in rats with 30-min ischemia, increased vascular permeability was observed throughout the necrosis area with a maximum in its center while early no-reflow was not detected both in vivo [19,28-30] and in experiments on the isolated heart [

31] in the presence of signs of irreversible damage to cardiomyocytes in the risk zone [

31]. Argano et al. (1996) reported the occurrence of no-reflow in the isolated blood-perfused rat heart model after 30-min ischemia and 40-80-min reperfusion and demonstrated the efficacy of SNP in its treatment [

20]. In other animal species, early no-reflow is also not pronounced or is absent after 30-min ischemia. For example, in rabbits, early no-reflow just begins to appear (12% of the risk zone) after 30-min myocardial ischemia [

21], and in dogs only after 90-min ischemia [

9]. The appearance of early no-reflow in the present study can be explained by the unusually low tolerance to ischemia of rat myocardial endotheliocytes. We did not change the experimental conditions in the present study. There are only two differences known to us from previous studies, which are the source of rats and the age of the rats (16 weeks), which were 4 weeks older than the previous rats. We found no unusual electrocardiographic measurements with either conventional or ultra-high-resolution ECG.

Reduced tolerance of endotheliocytes to ischemia was manifested in the appearance of early no-reflow after relatively short period of ischemia – 30 minutes. Intracellular edema covered the entire intramural layer and adjacent subendocardial and subepicardial regions in such a way that by the end of 30-min ischemia the size of the no-reflow zone occupied 40% of the risk zone. A leading role in the mechanism of early no-reflow in rats in this study is likely played by endothelial blebbing, because we found no evidence of significant vasoconstriction or external compression of capillaries in myocardial samples from control rats at 10 minutes of reperfusion. It is possible that blebbing occurs as defense mechanism to prevent endothelial cell necrosis when the usual ways of cell repair are no longer effective [

32]. Also, there is evidence that supports the version of intracellular edema, rather than the formation of the final stage of apoptosis, because of the fact that the final stage of apoptosis occurs only during the reperfusion phase [

33]. Nevertheless, the absence of enlargement of no-reflow area between the beginning and the end of reperfusion lead us to conclusion that injury of endothelial cells in one third of the entire risk zone occurred during ischemia. In other words, the comparison of no-reflow zone sizes obtained by ICG-0’ fluorescence images did not significantly differ from sizes of the no-reflow areas obtained by ThS-fluorescence images in the same rats in all groups except the SNP group. By the end of two-hour reperfusion, the size of no-reflow zones was 30-40% of the area of the risk zone, which is comparable to previous findings [

34].

The basic idea behind the inhibition of MLCK at the beginning of post-ischemic hyperemia is the reduction of no-reflow severity due to prevention of endothelial hyperpermeability and myocardial edema progression. This idea is supported by evidence of protective effect of MLCK inhibition in

in vitro [

14,

35] and

in vivo experiments [

36]. The genetic deficiency of 210 kDa MLCK in mice as well as MLCK inhibition by a small-molecule organic inhibitor increases resistance to lung injury in sepsis model by preserving the endothelial barrier function [

16]. In the present study peptide inhibitor PIK7 was used for inhibition of MLCK

in vivo [

17]. We anticipated that after a single administration of PIK7 at the very beginning of reperfusion, vascular permeability and intercellular edema in the risk zone would be reduced, which would reduce microvessels compression and ultimately improve microcirculation in injured myocardium.

Bolus intravenous administration of PIK7 just before the beginning of blood flow restoration decreased the intensity of ICG-0’ fluorescence (the level of contrast between the investigated zone and the reference zone), but not significantly due to the small number of observations (n=3). Electron microscopy of samples of intramural myocardium obtained at the 10th minute after injection of PIK7 2.5 mg/kg showed the anti-edema effect of PIK7 compared to the heart samples from the control group. Also, the samples from experimental animal showed an increase in the number of vessels in a state of pronounced tone compared to the control animal (40.7% and 7.5%, respectively). Interestingly, that in the intramural layer in control and experimental rats there was almost none of cases of weakening of intercellular contacts in capillaries. This suggests that in the center of the early no-reflow zone the endothelial barrier is preserved 10 minutes after the beginning of reperfusion due to reduced activation of endotheliocytes in conditions of insufficient blood flow. However, signs of short-term post-ischemic hyperemia were observed in control sample, accompanied by increased vascular permeability in the intramural layer, namely isolated cases of erythrocyte diapedesis. The consequences of which in the form of increased intra- and intercellular edema were reduced due to inhibition of MLCK in groups with PIK7 in the first minutes of reperfusion.

The anti-edema effect of PIK7 was transient, as revealed by ICG administration, at 90 minutes of reperfusion and comparison of ICG-fluorescence intensity in the necrosis zone between the three groups: CNT, PIK7-2.5, and PIK7-40. The levels of ICG accumulation did not differ between the groups.

To evaluate the efficacy of PIK7 under the conditions of vasodilator action used to treat primary no-reflow, PIK7 and SNP were administered simultaneously via different intravenous catheters. Co-injection of PIK7 solutions with SNP significantly shortened the infusion time of SNP compared with SNP without PIK7. The effect of PIK7 on the hypotensive effect of SNP allows us to consider PIK7 as a potential drug for the treatment of refractory vasoplegia.

The NO donor SNP eliminated primary no-reflow, but at the same time increased ICG-0’ fluorescence intensity of the necrosis zone, indicating an increase in vascular permeability over the entire area of the necrosis zone. Co-injection of PIK7 with SNP significantly reduced vascular permeability, but the area of primary no-reflow decreased not as significantly as in the SNP group. By the end of two-hour reperfusion, blood stasis was formed, the severity of which did not differ between the groups, and the infiltration of the intramural layer by segmented neutrophils (data not presented) was maximal in the PIK7-40 and SNP groups and minimal in the PIK7+SNP group.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, a single intravenous administration of MLCK inhibitor, PIK7, was found to reduce vascular hyperpermeability caused by ischemic and reperfusion injury and reduce edema at the onset of myocardial reperfusion. The effect of PIK7 at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg is transient and ceases within 90 minutes of reperfusion, so it is reasonable to evaluate its antiedemic effect with repeated administration or prolonged infusion. The early no-reflow detected for the first time in rats after 30-min ischemia reduces the area accessible for PIK7 action. Co-injection of PIK7 with SNP increases blood flow in the zone of early no-reflow while reducing the increased vascular permeability caused by SNP.

One more observation should be mentioned, which refers to the absence of significant differences in the areas of primary and secondary no-reflow zones, indicating a more significant ischemic myocardial damage and an insignificant role of reperfusion damage in rats with low myocardial tolerance to ischemia. There are opinions that microcirculatory damage in the zone at risk and no-reflow can increase myocardial infarct size [

22]. Our result with 30-min ischemia and two-hour reperfusion, as well as measurement of the no-reflow zone after 24-hour reperfusion in rats and mice, showed that the no-reflow zone is always smaller than the necrosis zone and is a consequence of irreversible myocardial damage rather than its cause [

19,

21].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., V.S. and M.G.; methodology, D.S., M.G. and V.S.; validation, D.S., M.M. and V.S.; formal analysis, D.S., M.M., D.M., N.S., K.B., I.An., .; investigation, D.S., M.M., K.B., A.K. and S.M.; resources, V.S., A.K., M.S., M.P. and K.Z.; data curation, D.S., D.M., N.S. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., I.Al., M.M. A.K. V.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S.; visualization, G.P., N.S. and N.P.; supervision, M.G. and V.S.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, Project 23-15-00151, https://rscf.ru/project/23-15-00151.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Commission for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Almazov National Medical Research Centre (protocol code PZ_23_6_Sonin_DL_V3 and date of approval 06.14.2023).

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kseniya A. Sterkhova for her excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miyazaki, S.; Fujiwara, H.; Onodera, T.; Kihara, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Wu, D.J.; Nakamura, Y.; Kumada, T.; Sasayama, S.; Kawai, C.; et al. Quantitative analysis of contraction band and coagulation necrosis after ischemia and reperfusion in the porcine heart. Circulation 1987, 75, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.; Gersh, B.J.; Mehran, R.; Brodie, B.R.; Brener, S.J.; Dizon, J.M.; Lansky, A.J.; Witzenbichler, B.; Kornowski, R.; Guagliumi, G.; Dudek, D.; Stone, G.W. Effect of Ischemia Duration and Door-to-Balloon Time on Myocardial Perfusion in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Analysis From HORIZONS-AMI Trial (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015, 8, 1966–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkabi, B.; Meir, G.; Zafrir, B.; Jaffe, R.; Adawi, S.; Lavi, I.; Flugelman, M.Y.; Shiran, A. Door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2021, 7, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.; Niccoli, G.; De Maria, G.; Brugaletta, S.; Montone, R.A.; Vergallo, R.; Benenati, S.; Magnani, G.; D’Amario, D.; Porto, I.; Burzotta, F.; Abbate, A.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Crea, F. Coronary microvascular obstruction and dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol 2024, 21, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloner, R.A.; Dai, W.; Hale, S.L. No-Reflow Phenomenon. A new target for therapy of acute myocardial infarction independent of myocardial infarct size. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2018, 23, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijnenberg, L.S.F.; Damman, P.; Duncker, D.J.; Kloner, R.A.; Nijveldt, R.; van Geuns, R.M.; Berry, C.; Riksen, N.P.; Escaned, J.; van Royen, N. Pathophysiology and diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Kastrati, A. Coronary No-Reflow after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Current Knowledge on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Clinical Impact and Therapy. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, L.A.; White, F.; Heggtveit, H.A.; Sanders, T.M.; Bloor, C.M.; Covell, J.W. Determinants of myocardial hemorrhage after coronary reperfusion in the anesthetized dog. Circulation 1982, 65, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, G.; Weisman, H.F.; Mannisi, J.A.; Becker, L.C. Progressive impairment of regional myocardial perfusion after initial restoration of postischemic blood flow. Circulation 1989, 80, 1846–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willerson, J.T.; Scales, F.; Mukherjee, A.; Platt, M.; Templeton, G.H.; Fink, G.S.; Buja, L.M. Abnormal myocardial fluid retention as an early manifestation of ischemic injury. Am J Pathol 1977, 87, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kloner, R.A.; Ganote, C.E.; Jennings, R.B. The “no-reflow” phenomenon after temporary coronary occlusion in the dog. J Clin Invest 1974, 54, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloner, R.A.; Rude, R.E.; Carlson, N.; Maroko, P.R.; DeBoer, L.W.; Braunwald, E. Ultrastructural evidence of microvascular damage and myocardial cell injury after coronary artery occlusion: which comes first? Circulation 1980, 62, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Malik, A.B. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev 2006, 86, 279–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Yi, W.; Zhang, C. Myosin Light Chain Kinase Modulates to Improve Myocardial Hypoxia/Reoxygenation Injury. J Healthc Eng 2022, 8124343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M.C.; Y-Rit, J.; Lando, U.; Kanmatsuse, K.; Mercier, J.C.; Ganz, W. The relationship of vascular injury and myocardial hemorrhage to necrosis after reperfusion. Circulation 1980, 62, 1274–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainwright, M.S. , Rossi, J., Schavocky, J., Crawford, S., Steinhorn, D., Velentza, A.V., Zasadzki, M., Shirinsky, V., Jia, Y., Haiech, J., Van Eldik, L.J., and Watterson, D.M. Protein kinase involved in lung injury susceptibility: evidence from enzyme isoform genetic knockout and in vivo inhibitor treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 62336238. [Google Scholar]

- Google Patents. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2682878C1/ru (accessed on 30 September 2024); EP 3858850 (Engl.): https://data.epo.org/gpi/EP3858850B1-NONAPEPTIDE-PREVENTING-INCREASED-HYPERPERMEABILITY-OF-VASCULAR-ENDOTHELIUM.

- Khapchaev, A.Y.; Shirinsky, V.P. Myosin Light Chain Kinase MYLK1: anatomy, interactions, functions, and regulation. Biochemistry 2016, 81, 1676–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonin, D.; Papayan, G.; Istomina, M.; Anufriev, I.; Pochkaeva, E.; Minasian, S.; Zaytseva, E.; Mukhametdinova, D.; Mochalov, D.; Aleksandrov, I.; Petrishchev, N.; Galagudza, M. Advanced technique of myocardial no-reflow quantification using indocyanine green. Biomed Opt Express 2024, 15, 818–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argano, V.; Galiñanes, M.; Edmondson, S.; Hearse, D.J. Effects of cardioplegia on vascular function and the “no-reflow” phenomenon after ischemia and reperfusion: studies in the isolated blood-perfused rat heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996, 111, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffelmann, T.; Kloner, R.A. Microvascular reperfusion injury: rapid expansion of anatomic no reflow during reperfusion in the rabbit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002, 283, H1099–H1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.H.; Ruze, A.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q.L.; Tang, J.; Xiefukaiti, N.; Gai, M.T.; Deng, A.X.; Shan, X.F.; Gao, X.M. The role and mechanisms of microvascular damage in the ischemic myocardium. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023, 80, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Wu, M.H.; Yuan, S.Y. Endothelial contractile cytoskeleton and microvascular permeability. Cell Health Cytoskelet 2009, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn, U.; Geissler, H.J.; Laine, G.A.; Allen, S.J. Myocardial fluid balance. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001, 20, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloka, J.A.; Friedrichson, B.; Wülfroth, P.; Henning, R.; Zacharowski, K. Microvascular leakage as therapeutic target for ischemia and reperfusion injury. Cells 2023, 12, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigor, R.R.; Shen, Q.; Pivetti, C.D.; Wu, M.H.; Yuan, S.Y. Myosin light chain kinase signaling in endothelial barrier dysfunction. Med Res Rev 2013, 33, 911–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, M.; Chernoff, J. An in vivo assay to test blood vessel permeability. J Vis Exp 2013, 73, e50062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffelmann, T.; Hale, S.L.; Dow, J.S.; Kloner, R.A. No-reflow phenomenon persists long-term after ischemia/reperfusion in the rat and predicts infarct expansion. Circulation 2003, 108, 2911–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, M.R.; de Waard, G.A.; Konijnenberg, L.S.; Meijer-van Putten, R.M.; van den Brom, C.E.; Paauw, N.; de Vries, H.E.; van de Ven, P.M.; Aman, J.; Van Nieuw-Amerongen, G.P.; Hordijk, P.L.; Niessen, H.W.; Horrevoets, A.J.; Van Royen, N. Dissecting the effects of ischemia and reperfusion on the coronary microcirculation in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0157233. [Google Scholar]

- Sonin, D.; Papayan, G.; Pochkaeva, E.; Chefu, S.; Minasian, S.; Kurapeev, D.; Vaage, J.; Petrishchev, N.; Galagudza, M. In vivo visualization and ex vivo quantification of experimental myocardial infarction by indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. Biomed Opt Express 2016, 8, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, B.J.; McCarthy, A. Endothelial cell “swelling” in ischaemia and reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1995, 27, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draeger, A.; Monastyrskaya, K.; Babiychuk, E.B. Plasma membrane repair and cellular damage control: the annexin survival kit. Biochem Pharmacol 2011, 81, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freude, B.; Masters, T.N.; Robicsek, F.; Fokin, A.; Kostin, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Ullmann, C.; Lorenz-Meyer, S.; Schaper, J. Apoptosis is initiated by myocardial ischemia and executed during reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2000, 32, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonin, D.L.; Pochkaeva, E.I.; Papayan, G.V.; Minasian, S.M.; Mukhametdinova, D.V.; Zaytseva, E.A.; Mochalov, D.A.; Petrishchev, N.N.; Galagudza, M.M. Cardio- and vasoprotective effects of quinacrine in an in vivo rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Bull Exp Biol Med 2024, 177, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.Y.; Wu, M.H.; Ustinova, E.E.; Guo, M.; Tinsley, J.H.; De Lanerolle, P.; Xu, W. Myosin light chain phosphorylation in neutrophil-stimulated coronary microvascular leakage. Circ Res 2002, 90, 1214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayburgh, D.R.; Barrett, T.A.; Tang, Y.; Meddings, J.B.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Watterson, D.M.; Clarke, L.L.; Mrsny, R.J.; Turner, J.R. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation-induced diarrhea in vivo. J Clin Invest 2005, 115, 2702–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himori, N.; Matsuura, A. A simple technique for occlusion and reperfusion of coronary artery in conscious rats. Am J Physiol 1989, 256, H1719–H1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Uk.; Papayan, G.V. Fluorescent endoscope system having improved image detection module. US Patent No US7635330, 22 12 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichenko, K.V.; Kordyukova, A.A.; Logachev, E.P.; Luchkova, L.M. Application of Radar Techniques of Signal Processing for Ultra-High Resolution Electrocardiography. Biomed Eng 2021, 55, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichenko, K.V.; Kordyukova, A.A.; Sonin, D.L.; Galagudza, M.M. Ultra-High-Resolution Electrocardiography Enables Earlier Detection of Transmural and Subendocardial Myocardial Ischemia Compared to Conventional Electrocardiography. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).