Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

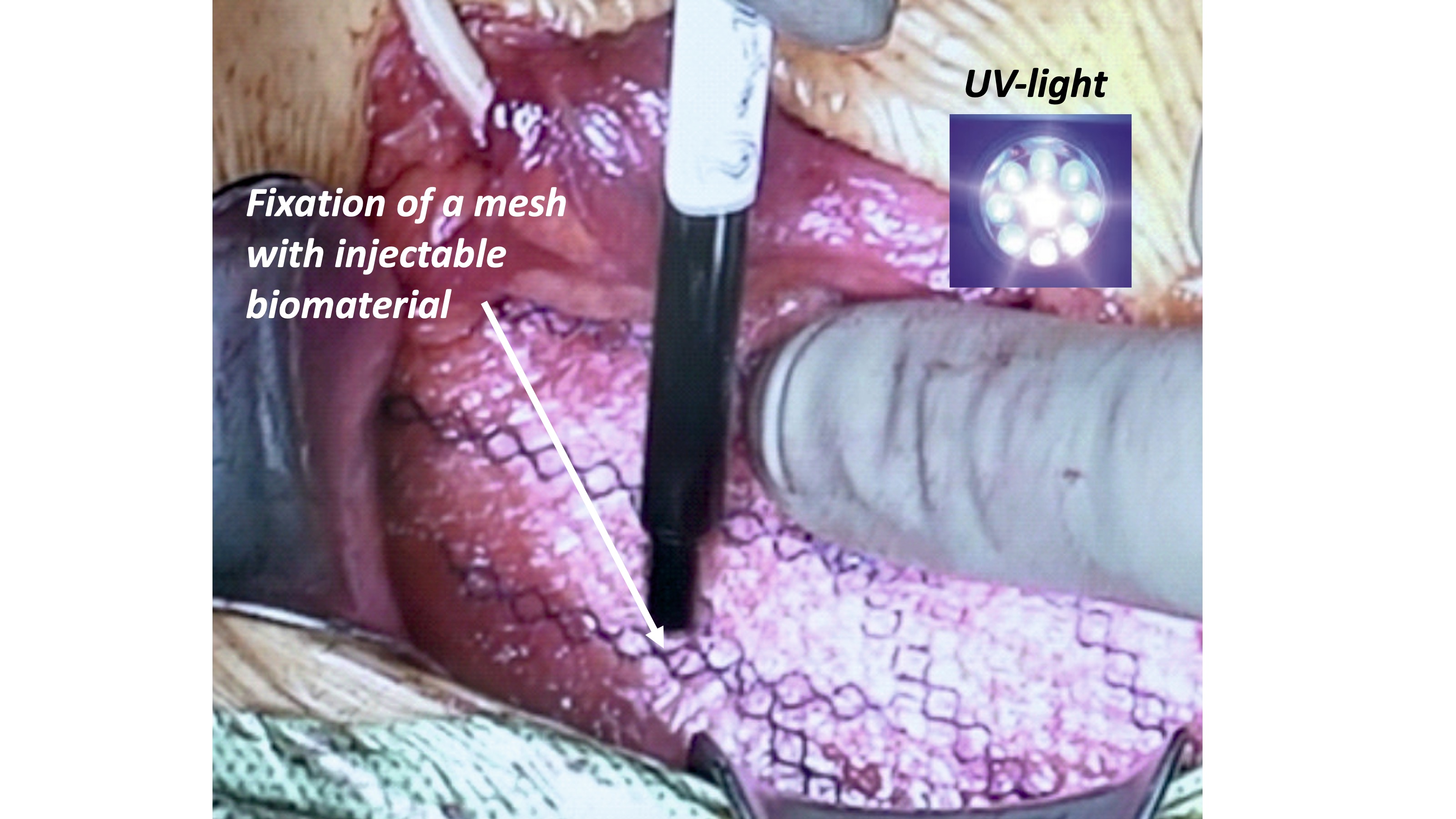

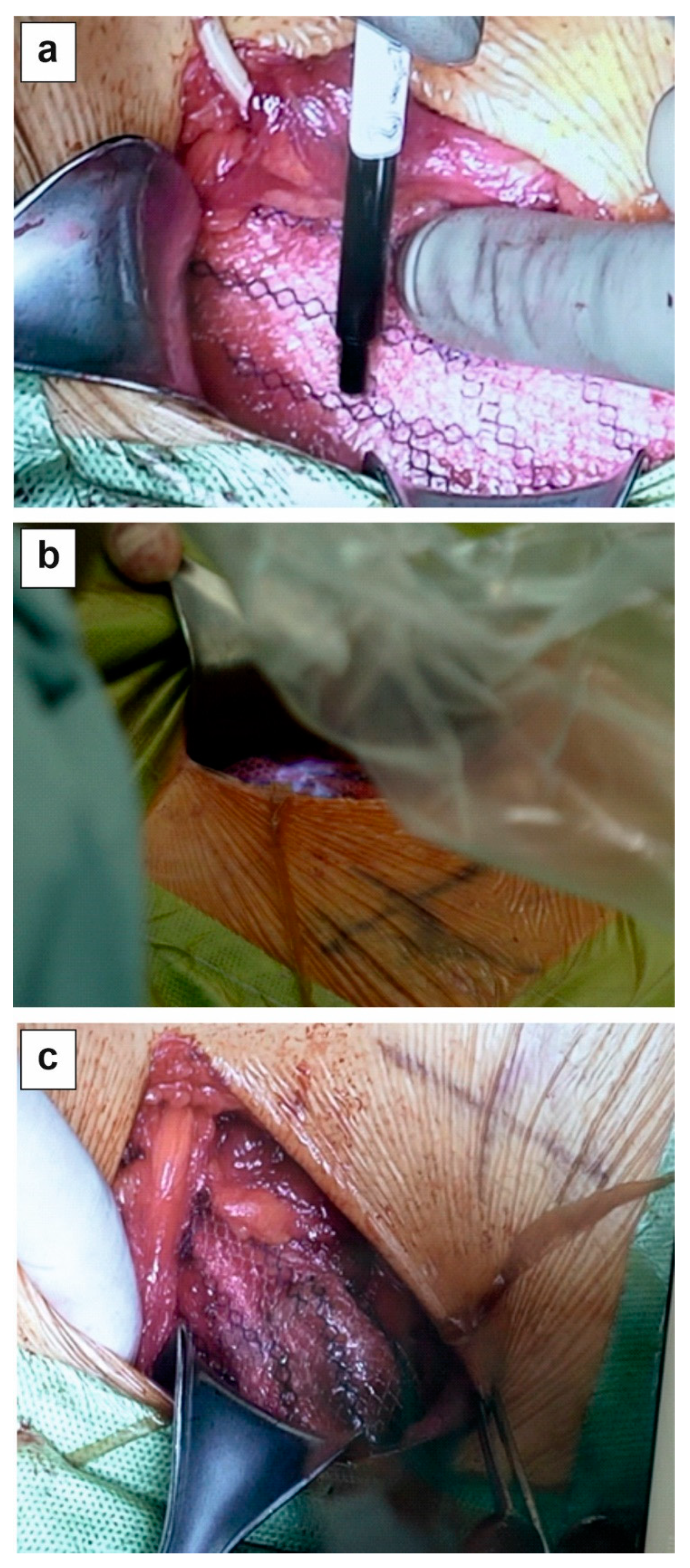

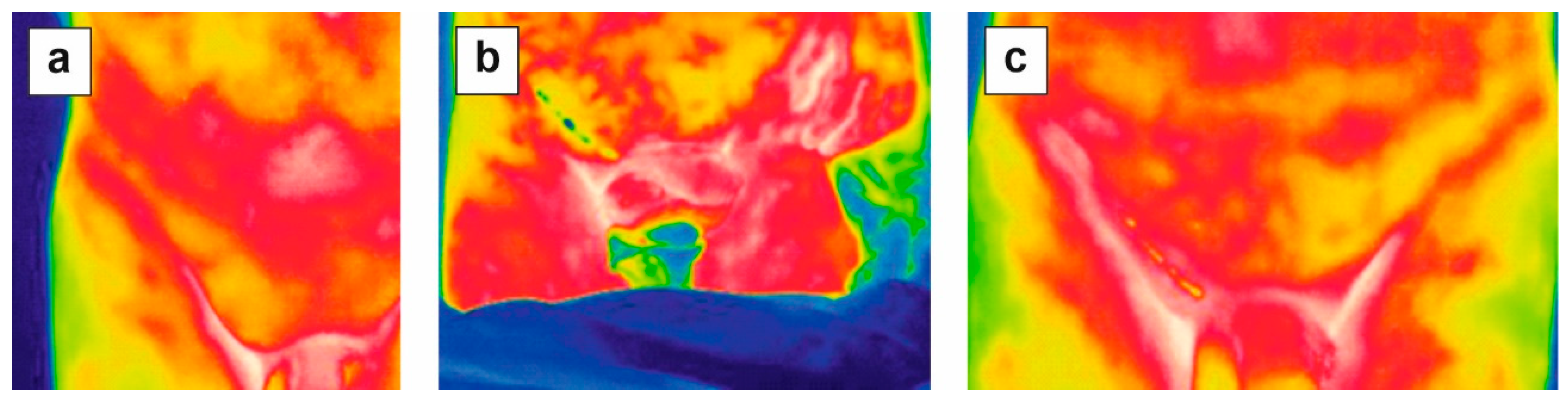

2.1. PhotoBioCure Material

2.2. Patients

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Postoperative Care

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

| PhotoBioCure Fixationa | Suture Fixationa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Mean Value (±SD) | Mean Value (±SD) | |

| Pain | |||

| before surgery | 8.60 (2.19) | 8.60 (2.30) | |

| 1st day | 22.60 (1.95) | 21.80 (2.17) | |

| 8th days | 13.40 (1.14) | 12.40 (1.34) | |

| 6th weeks | 3.40 (1.82) | 3.60 (1.14) | |

| 12th months | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 24th months | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Restriction of activity | |||

| before surgery | 12.80 (4.66) | 11.80 (3.42) | |

| 1st day | 35.00 (3.16) | 34.30 (3.35) | |

| 8th days | 18.40 (3.65) | 17.40 (3.36) | |

| 6th weeks | 6.60 (1.34) | 6.60 (2.41) | |

| 12th months | 1.40 (1.14) | 1.00 (0.00) | |

| 24th months | 1.20 (0.84) | 1.00 (0.00) | |

| ap > 0.05, Friedman test | |||

4. Statistical Method

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hollinsky, C.; Kolbe, T.; Walter, I.; Joachim, A.; Sandberg, S.; Koch, T.; Rülicke, T. Comparison of a New Self-Gripping Mesh with Other Fixation Methods for Laparoscopic Hernia Repair in a Rat Model. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2009, 208, 1107–1114. [CrossRef]

- Nikkolo, C.; Lepner, U. Chronic pain after open inguinal hernia repair. Postgrad. Med. 2015, 128, 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.K.; Amid, P.K.; Chen, D.C. Groin Pain After Inguinal Hernia Repair. Adv. Surg. 2016, 50, 203–220. [CrossRef]

- Kim-Fuchs C, Angst E, Vorburger S, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing sutured with sutureless mesh Wxation for Lichtenstein hernia repair: Long-term results. Hernia 2012; 16(1): 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Helbling, C.; Schlumpf, R. Sutureless Lichtenstein: First results of a prospective randomised clinical trial. Hernia 2003, 7, 80–84. [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, G.; Pettinari, D.; Cavalli, M.; Avesani, E.; Ec, A. A modified Lichtenstein hernia repair using fibrin glue. J. Minimal Access Surg. 2006, 2, 129–33. [CrossRef]

- Lovisetto F, Zonta S, Rota E, et al. Use of human fibrin glue (Tissucol) versus staples for mesh fixation in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernioplasty: A prospective, randomized study. Ann Surg 2007; 245(2): 222–231. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zheng, X.; Gu, Y.; Guo, S. A Meta-Analysis Examining the Use of Fibrin Glue Mesh Fixation versus Suture Mesh Fixation in Open Inguinal Hernia Repair. Dig. Surg. 2014, 31, 444–451. [CrossRef]

- Trisca, R.; Oprea, V.; Toma, M.; Bucuri, C.E.; Stancu, B.; Grad, O.; Gherman, C. The Effectiveness of Cyanoacrylates versus Sutures for Mesh Fixation after Lichtenstein Repair (SCyMeLi STUDY) A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyze of Randomized Controlled Trials. Chirurgia 2024, 119, 87–101. [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowiecki, S.; Pierściński, S.; Szczęsny, W. The Glubran 2 glue for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein’s hernia repair: a double-blind randomized study.. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2012, 7, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Odobasic, A.; Krdzalic, G.; Hodzic, M.; Hasukic, S.; Sehanovic, A.; Odobasic, A. The Role of Fibrin Glue Polypropylene Mesh Fixation in Open Inguinal Hernia Repair. Med Arch. 2014, 68, 90–93. [CrossRef]

- Ladurner, R.; Drosse, I.; Bürklein, D.; Plitz, W.; Barbaryka, G.; Kirchhoff, C.; Kirchhoff, S.; Mutschler, W.; Schieker, M.; Mussack, T. Cyanoacrylate Glue for Intra-abdominal Mesh Fixation of Polypropylene-Polyvinylidene Fluoride Meshes in a Rabbit Model. J. Surg. Res. 2011, 167, e157–e162. [CrossRef]

- Haroon, M.; Morarasu, S.; Morarasu, B.C.; Al-Sahaf, O.; Eguare, E. Assessment of feasibility and safety of cyanoacrylate glue versus absorbable tacks for inguinal hernia mesh fixation. A prospective comparative study.. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2022, 17, 90–98. [CrossRef]

- Skrobot, J.; Zair, L.; Ostrowski, M.; El Fray, M. New injectable elastomeric biomaterials for hernia repair and their biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 182–192. [CrossRef]

- Taboada, G.M.; Yang, K.; Pereira, M.J.N.; Liu, S.S.; Hu, Y.; Karp, J.M.; Artzi, N.; Lee, Y. Overcoming the translational barriers of tissue adhesives. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 310–329. [CrossRef]

- Pradas MM, Vicent MJ. Polymers in Regenerative Medicine: Biomedical Applications from Nano- to Macro-Structures. Polymers in Regenerative Medicine: Biomedical Applications from Nano- to Macro-Structures. 2014. p. 1–393.

- El Fray, M.; Skrobot, J.; Bolikal, D.; Kohn, J. Synthesis and characterization of telechelic macromers containing fatty acid derivatives. React. Funct. Polym. 2012, 72, 781–790. [CrossRef]

- Fortelny, R.H.; Petter-Puchner, A.H.; Redl, H.; May, C.; Pospischil, W.; Glaser, K. Assessment of Pain and Quality of Life in Lichtenstein Hernia Repair Using a New Monofilament PTFE Mesh: Comparison of Suture vs. Fibrin-Sealant Mesh Fixation. Front. Surg. 2014, 1, 45. [CrossRef]

- Jeroukhimov, I.; Dykman, D.; Hershkovitz, Y.; Poluksht, N.; Nesterenko, V.; Ben Yehuda, A.; Stephansky, A.; Zmora, O. Chronic pain following totally extra-peritoneal inguinal hernia repair: a randomized clinical trial comparing glue and absorbable tackers. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Mathes T, Prediger B, Walgenbach M, et al. Mesh fixation techniques in primary ventral or incisional hernia repair. Vol. 2021, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Vindal, A. Gelatin–resorcin–formalin (GRF) tissue glue as a novel technique for fixing prosthetic mesh in open hernia repair. Hernia 2009, 13, 299–304. [CrossRef]

- Hoyuela, C.; Juvany, M.; Carvajal, F.; Veres, A.; Troyano, D.; Trias, M.; Martrat, A.; Ardid, J.; Obiols, J.; López-Cano, M. Randomized clinical trial of mesh fixation with glue or sutures for Lichtenstein hernia repair. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 688–694. [CrossRef]

- Mitura, K.; Garnysz, K.; Wyrzykowska, D.; Michałek, I. The change in groin pain perception after transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair with glue fixation: a prospective trial of a single surgeon’s experience. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 4284–4289. [CrossRef]

- Fortelny, R.H.; Petter-Puchner, A.H.; May, C.; Jaksch, W.; Benesch, T.; Khakpour, Z.; Redl, H.; Glaser, K.S. The impact of atraumatic fibrin sealant vs. staple mesh fixation in TAPP hernia repair on chronic pain and quality of life: results of a randomized controlled study. Surg. Endosc. 2011, 26, 249–254. [CrossRef]

- Tish, S.; Krpata, D.; AlMarzooqi, R.; Huang, L.-C.; Phillips, S.; Fafaj, A.; Tastaldi, L.; Alkhatib, H.; Zolin, S.; Petro, C.; et al. Comparing 30-day outcomes between different mesh fixation techniques in minimally invasive inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 2020, 24, 961–968. [CrossRef]

- Bellad, A.P.; Pratap, K.A. Effectiveness of tissue adhesive versus conventional sutures in the closure of inguinal hernia skin incisions: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int. Surg. J. 2018, 5, 1797–1801. [CrossRef]

| PhotoBioCure Fixationa [min] (±SD) |

Suture fixationa [min] (±SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Average operating timeb | 52.00 (3.08) | 60.20 (3.70) |

| Postoperative hospital stay | 1 day | 1 day |

| Average time to resumption of normal activity | 6 weeks | 6 weeks |

| Duration of follow-up | 24 | 24 |

| Intraoperative complications (n) | 0 | 0 |

| a n = 5, b p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test |

| Follow-Up Period | Fixation | Mean Pain Scorea (±SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1st day | PhotoBioCure | 2.6 (0.55) |

| 8th day | PhotoBioCure | 0.8 (0.84) |

| 6th week | PhotoBioCure | 0 |

| 12th month | PhotoBioCure | 0 |

| 24th month | PhotoBioCure | 0 |

| a p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test | ||

| PhotoBioCure Fixationa,b | Suture Fixationa,b | |

|---|---|---|

| Follow-Up Period | Mean Value of Severity [%](±SD) | Mean Value of Severity [%](±SD) |

| 1st day | 54.08 (9.74) | 65.32 (4.26) |

| 8th days | 40.98 (9.54) | 49.45 (5.92) |

| 6th weeks | 30.38 (8.94) | 36.57 (2.21) |

| 12th months | 8.28 (1.71) | 8.97 (1.71) |

| 24th months | 1.38 (1.50) | 1.38 (0,96) |

| ap < 0.05, ANOVA test (among methods); b p > 0.05 Mann-Whitney U test (between methods) | ||

| SF-36 | Mean Valuea(±SD) |

|---|---|

| preoperatively | 77.8 (6.72)b |

| 6th weeks postoperatively | 71.6 (6.34)b |

| 12th months postoperatively | 88.2 (4.82)b |

| 24th months postoperatively | 92.4 (3.26)b |

| ascore of 100 indicates the highest quality of life, with lower scores reflecting deterioration; b p < 0.05, ANOVA test | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).