1. Introduction

The fine-structure constant,

α, is one of the universe’s most significant and enigmatic constants, valued at approximately 1/137. This fundamental constant plays a crucial role in determining the strength of electromagnetic interactions, influencing the behavior of charged particles like electrons and protons. It shapes atomic structure, quantum electrodynamics (QED), and photon-matter interactions, with implications across diverse areas in physics, including quantum field theory and relativistic frameworks. One intriguing aspect of α is its dimensionless nature, making it universally applicable across various physical contexts. Despite advances in physics, the fine-structure constant remains an unsolved puzzle, both in its specific numerical value and as a profound challenge to our understanding of the fundamental laws of the universe [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

In this paper, we propose a novel approach to understanding the fine-structure constant by exploring a potential relationship among the mathematical constant π, the electron’s rotational dynamics, and relativistic effects characterized by the Lorentz factor. The electron’s intrinsic spin significantly influences its interaction with electromagnetic fields [

7,

8]. Although electron spin is a quantum mechanical property, it can also be examined through a relativistic lens, particularly in high-speed scenarios where the electron’s velocity approaches the speed of light. In such cases, the Lorentz factor (γ) modifies the electron’s observed properties according to special relativity. At high velocities, the electron’s effective mass and interaction with electromagnetic fields are altered, impacting how its rotation (or spin) is perceived.

Section 2 presents an in-depth analysis of the relationship between the π/γ ratio and the origin of the fine-structure constant. By examining the interaction between the electron’s rotation and this Lorentz factor, we aim to investigate whether α can be derived from a ratio involving π and these fundamental relativistic corrections. We propose that α, which encapsulates the strength of electromagnetic interactions, may emerge from a ratio involving π, the electron’s relativistically corrected rotation, and a specific Lorentz factor. In our approach, we introduce a Lorentz factor of 430, representing a relativistic correction that influences the electron’s behavior. This correction may provide insight into why α has its specific value and its relation to deeper principles in quantum mechanics and special relativity.

Section 3 discusses the deviation of the electron’s anomalous magnetic moment due to spin, which relates to the π/γ ratio, and

Section 4 concludes the discussion. Ultimately, this paper seeks to advance the quest to demystify the fine-structure constant by proposing a new perspective that emphasizes the role of electron spin and relativistic effects, governed by the Lorentz factor, in determining the value of α. If successful, this approach could help bridge the gap between quantum mechanics, relativity, and the fundamental constants shaping our understanding of the universe.

2. The Relationship Between π/γ and The Fine-Structure Constant

The fine-structure constant, α, characterizes the splitting of atomic spectral lines, first observed in the hydrogen atom. This constant is closely associated with an electron’s spin and orbital angular momentum, as described in Bohr’s atomic model. Arnold Sommerfeld later extended Bohr’s model by introducing relativistic corrections and elliptical orbits, using α to account for the fine structure observed in hydrogen’s spectral lines [

9,

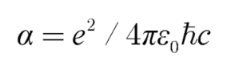

10]. Additionally, α plays a crucial role in determining the strength of the electromagnetic interaction between elementary charged particles. The fine-structure constant, α, is defined as follows:

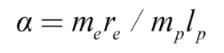

where e is the electron charge, ε

0 is the permittivity of free space, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, and c is the speed of light in a vacuum (approximately 3×10

8 m/s). From equation (1.1), we see that the term 1/4πε

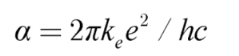

0 is Coulomb’s constant. Thus, we can rewrite equation (1.1) as:

where h is Planck’s constant, which is approximately 6.626×10

−34 J·s, and k

e is approximately 8.99×109 N·m

2/C

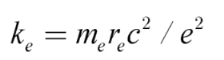

2. In certain contexts, k

e can also be expressed in terms of the electron’s mass and classical radius [

11] as follows:

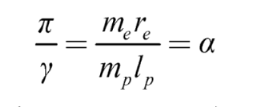

where m

e and r

e are the electron’s rest mass and classical radius which are equal to 9.1×10

−31 kg and 2.82×10

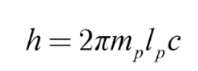

−15 meters, respectively. Similarly, Planck’s constant can be expressed in terms of Planck’s mass and length [

12,

13]:

where m

p and l

p are Planck’s mass and length, valued at 2.176×10

−8 kg and 1.616×10

−35 meters, respectively. Using equations (1.2) – (1.4), we can express the fine-structure constant in terms of:

In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed the concept of matter waves in his doctoral thesis. This idea, suggesting that elementary particles like electrons exhibit wave-like properties [

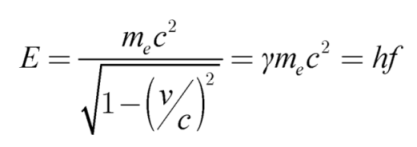

14], became a foundational aspect of quantum mechanics. The relativistic energy from a matter wave can be expressed by the equation:

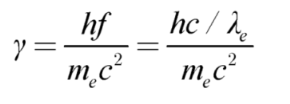

where γ is the Lorentz factor and f is the frequency of the matter wave. From equation (1.6), we find that

where λ

e is the wavelength of the electron’s matter wave. This wavelength can be determined as twice the radius of an electron, as described in a Nobel Prize-winning chemistry study from 2023 [

15]. Thus, equation (1.7) can be rewritten as:

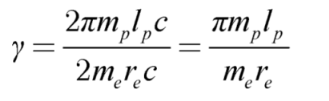

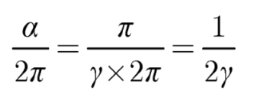

Considering the equations (1.5) and (1.8), we can express the relationship of the fine-structure constant as:

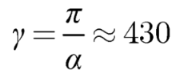

we know that α is approximately 1/137. Then, γ is equal to

Examining equation (1.10) shows that a free electron has a rotational velocity corresponding to a γ factor of approximately 430. With this rotational speed, the electron’s velocity reaches 0.9999973c, which is nearly the speed of light. Notably, α is a dimensionless quantity, representing the ratio of π to γ, both of which are also dimensionless.

3. The Electron Anomalous Magnetic Moment and the π/γ Ratio

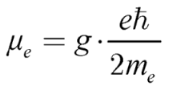

The fine-structure constant, α, and the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron are fundamental to understanding the behavior of charged particles, the strength of their interactions, and achieving precision measurements in quantum electrodynamics (QED). The anomalous magnetic moment,

ae, represents the deviation of the electron’s actual magnetic moment from the value predicted by Dirac theory, which accounts only for basic relativistic effects and spin interactions. In Dirac’s theory, the electron’s magnetic moment is given by

where

g is the electron’s gyromagnetic ratio, also known as the

g-factor, which is theoretically set to 2 [

16,

17,

18]. However, due to higher-order QED effects, the experimentally measured

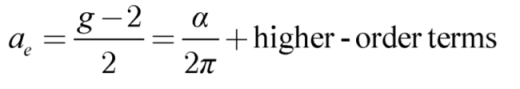

g-factor deviates slightly from 2. This deviation results from interactions between the electron and the quantized electromagnetic field, which can be understood as exchanges of virtual photons and electron-positron pairs. The theoretical prediction for the anomalous magnetic moment involves an infinite series of QED corrections, expressed as:

Although Dirac’s theory sets g = 2, Schwinger’s calculations of QED corrections introduced a first-order correction term of

α/2π, which matches experimental measurements to a high degree of precision [

19]. By examining equations (1.10) and (1.12), we can express the leading-order correction term

α/2π in terms of π/γ, finding:

which is approximately 1/860 or about 0.00116. This relationship underscores that both the fine structure constant and the anomalous magnetic moment arise from interactions between electrons and the quantized electromagnetic field, with both phenomena closely related to γ, a dimensionless constant critical for QED precision predictions.

4. Conclusions

This study explores a novel approach to understanding the fine-structure constant, α, by examining its connection to the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron through the ratio π/γ. Our findings indicate that α, a fundamental constant influencing the strength of electromagnetic interactions, can be interpreted as a simple ratio involving π and a relativistic Lorentz factor, γ. This ratio aligns with the electron’s relativistic spin dynamics, providing insights into the electron’s rotational behavior at velocities near the speed of light.

The anomalous magnetic moment, arising from electron spin interactions and deviations in the electron’s magnetic moment from Dirac theory, is a central aspect of quantum electrodynamics corrections. By connecting α to π/γ, our approach suggests that both the fine-structure constant and the anomalous magnetic moment share a deep-rooted relationship influenced by relativistic and quantum corrections to electron dynamics. Specifically, the factor γ ≈ 430 corresponds to an electron velocity approaching 0.9999973c, emphasizing the near-light speed rotational effects contributing to the values of both α and the magnetic moment anomaly.

In this framework, α emerges not only as a dimensionless constant but as an expression of the electron’s relativistically corrected rotational dynamics, framed within the π/γ ratio. This proposition offers a unified perspective that links quantum mechanics, relativistic effects, and fundamental constants, providing a potential pathway toward a deeper understanding of the values and origins of constants that shape our physical theories. Future research could further investigate this relationship and its implications for bridging gaps between QED, relativity, and the foundational principles governing charged particle interactions.

References

- Dirac, P.A.M. “Quantised Singularities in the Electromagnetic Field. ” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A 1931, 133, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, F. “The Radiation Theories of Tomonaga, Schwinger, and Feynman. ” Physical Review 1952, 87, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Sherbon, M. A. Fundamental Nature of the Fine-Structure Constant. International Journal of Physical Research 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.-C. Atomic physics determination of the fine structure constant. National Science Review 2020, 7, 1797–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butto, N. A New Theory on the Origin and Nature of the Fine Structure Constant. Journal of High Energy Physics. Gravitation and Cosmology 2020, 6, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. D. (1998). Classical Electrodynamics. Wiley.

- Sakurai, J. J. , & Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerfeld, A. Atomic Structure and Spectral Lines, London: Methuen, 118, 1923.

- Kragh, H. Niels Bohr and the Quantum Atom, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Shulman, M.E. On the Structure of Electrons and Other Charged Leptons. Journal of High Energy Physics Gravitation and Cosmology 2017, 3, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Humpherys, Natural Planck Units and the Structure of Matter and Radiation, Quantum Speculations 3 (2021), 1–20.

- Askar Abdukadyrov, Fundamental Values of Length, Time, and Speed, Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences 4, No. 4 (2020) 2050008:1-8.

- De Broglie, L. (1924) Recherches sur la théorie des quanta. PhD Thesis, Masson, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Quantum dots — seeds of nanoscience, The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2023 - NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2023/press-release/.

- Mohr, P.J. , Taylor, B.N. and Newell, D.B. CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2010. Reviews of Modern Physics 2012, 84, 1527–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, A. , Toichiro K. and Makiko N., “Theory of the Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Electron”. Atoms 2019, 7, 28. [CrossRef]

- Marius Arghirescu, An Explanation of the Anomalous Magnetic Moment of Electron and of Muon in Accordance with a Pre-Quantum Vortexial Model of Particle and of Magnetic Moment. Journal of Particle Physics 2020, 4. [CrossRef]

- J. Schwinger, On Quantum Electrodynamics and the Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Physical Review 1948, 73, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).