1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most prevalent and one of the deadliest forms of pancreatic cancer, with a poor prognosis due to factors such as late-stage diagnosis, high recurrence rates, metastasis, and intratumoral heterogeneity [

1]. The aggressiveness of PDAC is further compounded by cancer cell plasticity, including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [

2]. Additionally, pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), cancer stem cells (PCSCs), and the immunosuppressive, desmoplastic, and hypovascular tumor microenvironment (TME) contribute significantly to treatment challenges and chemoresistance [

3]. PDAC typically develop mechanisms that suppress natural killer (NK) cell function. As a result, PDAC remains resistant to current therapies. NK cells, which are cytotoxic lymphocytes, play a crucial role in eliminating tumor cells and virally infected cells as part of the innate immune response. Chemotherapy impacts the immune system through damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and alters the activating and inhibitory receptors on NK cells [

4].

Current standard therapies for metastatic PDAC, such as FOLFIRINOX (a combination of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine/nano albumin- bound paclitaxel, provide only limited survival benefits compared to gemcitabine monotherapy [

5,

6]. Chemoresistance in PDAC is driven by various mechanisms, including alterations in over 165 drug resistance genes, modulation of microRNAs (miRNAs), cancer stem cell induction, and overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) genes. Changes in the TME and immune surveillance also play significant roles in resistance [

3]. Furthermore, the two major molecular subtypes of PDAC—classical epithelial (E) and qusimesechymal (QM)—along with the key role of EMT, have been shown to impact treatment response in both preclinical and clinical settings [

7].

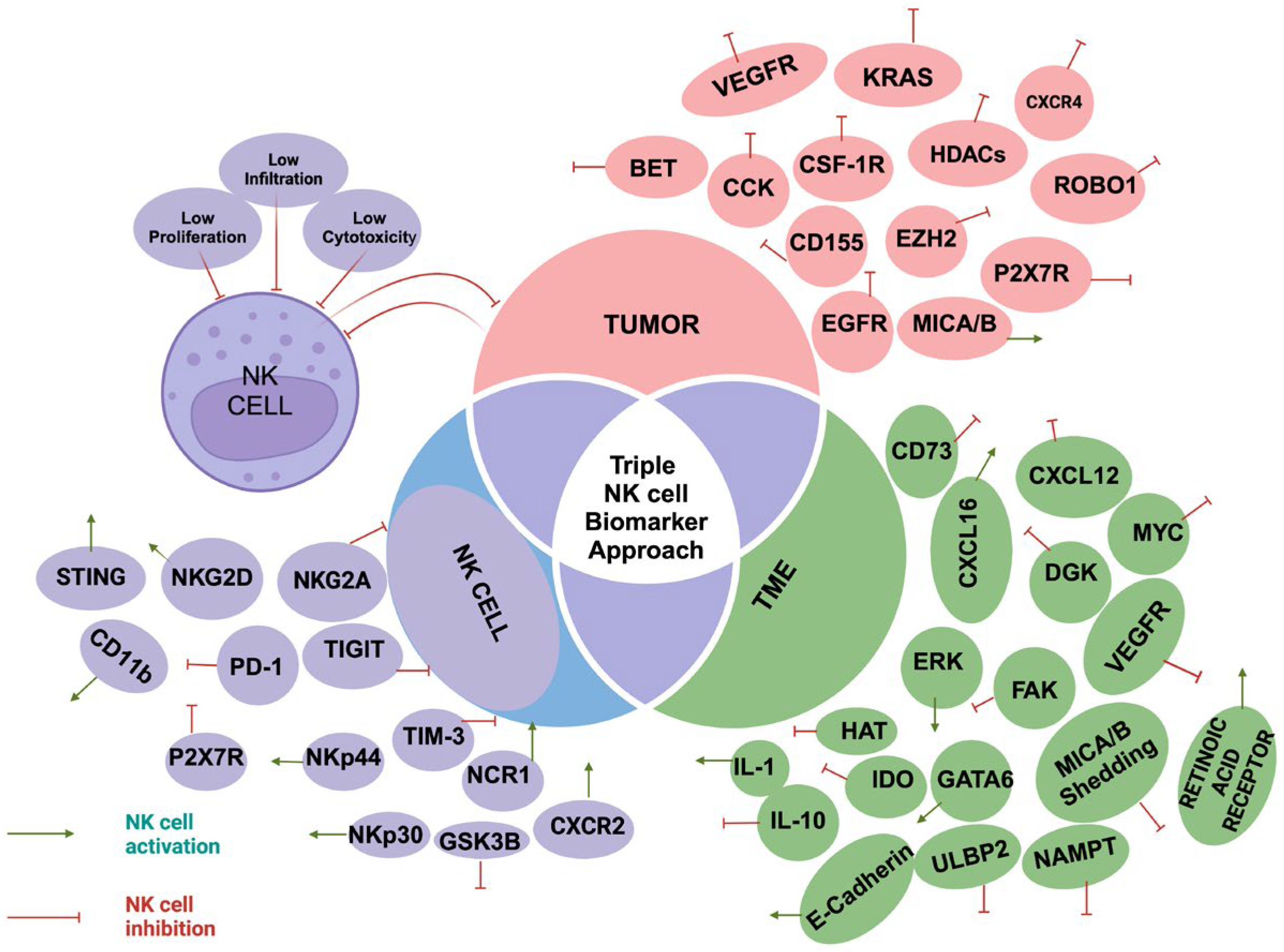

This review will focus on the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of NK cells in overcoming PDAC resistance. We will examine three key components: NK cell phenotypes, tumor characteristics, and changes in the TME. Specifically, we will discuss mechanisms of NK cell suppression, including alterations in NK cell abundance, function, and tumor infiltration. By using a "triple NK cell biomarker approach (

Figure 1) we aim to identify biomarkers [

Table 1] and targets associated with NK cell cytotoxicity in tumor cells, the TME, and NK cells. This integrated approach has the potential to provide critical insights into overcoming PDAC chemoresistance and facilitating the development of personalized therapeutic strategies.

This figure illustrates the three key components: the tumor, the tumor microenvironment (TME), and their interaction with NK cell activity. It highlights the three main mechanisms of NK cell suppression—reduced NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and infiltration. Additionally, the figure shows various tumor and TME elements and markers that can either activate or suppress NK cells.

Table 1.

NK Cell Applications in the Management of Treatment-Resistant Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC), using Triple Biomarker Approach.

Table 1.

NK Cell Applications in the Management of Treatment-Resistant Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC), using Triple Biomarker Approach.

| Biomarker/Target |

Source |

Impact on

NK cells |

Therapeutic

approach |

References |

| BET |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

Bromodomain inhibitors (increasing NKGD ligand

MICA expression). |

[37] |

| CCK |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

CCK inhibitors |

[50,51] |

| CD11b |

NK cell |

Activating |

CD11b agonists |

[26,133] |

| CD155 |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

Targeting alternating splicing of CD155 |

[112] |

| CD73 |

TME |

Inhibitory |

CD73 inhibitors or Diclofenac |

[58,110] |

| CSF-1R |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

CSF-1R inhibitors |

[87,88,106] |

| CXCL12 |

TME |

Inhibitory |

CXCL12 inhibitors |

[34,125] |

| CXCL16 |

TME |

Activating |

NRP-body |

[127] |

| CXCR2 |

NK cell |

Activating |

IL-1 therapy |

[32,33] |

| CXCR4 |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

CXCR4 antagonists |

[6,31,33] |

| DGK |

TME |

Inhibitory |

DGK inhibitors |

[107] |

| E-cadherin |

TME |

Activating |

EZH2 inhibitors, E-cadherin upregulation |

[62,122] |

| EGFR mutation |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

Cetuximab + IL-21 |

[90] |

| ERK |

TME |

Activating |

NRP-body |

[127] |

| EZH2 |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

EZH2 knockdown or inhibitors, microRNA-26a, EZH2 blockade trametinib/palbociclib |

[79,122] |

| FAK |

TME |

Inhibitory |

FAK inhibitors |

[27,28] |

| GATA6 |

TME |

Activating |

GATA6 inhibitors |

[17,18] |

| GSK3B |

NK cell |

Inhibitory |

GSK3B inhibitors |

[81] |

| HAT |

TME |

Inhibitory |

HAT inhibitors, curcumin |

[80] |

| HDACs |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

HDAC inhibitors |

[81] |

| IDO |

TME |

Inhibitory |

IDO inhibitors |

[48,136] |

| IL-1 |

TME |

Activating |

IL-1 therapy |

[89,92,128] |

| IL-10 |

TME |

Inhibitory |

IL-10 inhibitors |

[9,57,86] |

| KRAS |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

NK adoptive cell transfer, NK cell infiltration inducers |

[12,69] |

| MICA/B shedding |

TME |

Inhibitory |

MICA/B inhibitors |

[30] |

| MICA/B expression |

Tumor cell |

Activating |

Low-dose gemcitabine |

[28,111] |

| MYC |

TME |

Inhibitory |

MYC inhibitors |

[13,75] |

| NAMPT |

TME |

Inhibitory |

NAMP inhibitors + metformin, STING agonists |

[15,82] |

| NCR1(NKp46) |

NK cell |

Activating |

IDO inhibitors, STAT3 inhibitors, NK cell engagers |

[135,142] |

| NKG2A |

NK cell |

Inhibitory |

NK cell engagers, NKG2A blockade |

[29,142] |

| NKG2D |

NK cell |

Activating |

NK cell engagers |

[135] |

| NKp30 |

NK cell |

Activating |

NK cell engagers |

[142] |

| NKp44(NCR2) |

NK cell |

Activating |

NK cell engagers |

[142] |

| P2X7R |

Tumor cell

NK cell |

Inhibitory |

P2X7 inhibitors |

[24,60,61] |

| PD-1 |

NK cell |

Inhibitory |

PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors + IL-6 inhibitors or

Lenvatinib; Lenvatinib + GVAX + CSF-1R inhibitors |

[103] |

| Retinoic acid receptors |

TME |

Activating |

ATRA |

[25] |

| ROBO1 |

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

ROBO1-targeted CAR NK therapy or NK cell infusion |

[118,119] |

| STING |

TME |

Activating |

STING agonists + gemcitabine |

[70,91] |

| TIGIT |

NK cell |

Inhibitory |

Trastuzumab + rituximab, and anti-TIGIT monoclonal antibody |

[94] |

| TIM-3 |

NK cell |

Inhibitory |

TIM-3 targeting |

[100,101] |

| ULBP2 |

TME |

Inhibitory |

ULBP2 downregulation by gemcitabine |

[56] |

| VEGFR |

TME

Tumor cell |

Inhibitory |

VEGFR inhibitors + anti-PD-L1 |

[103] |

2. NK Cells: Diagnostic Potential

NK cells are critical lymphocytes in the innate immune system, recognized for their pivotal role in tumorimmunosurveillance. They function by balancing of activating and inhibitory receptors, including cytokine receptors and those involved in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) [

4,

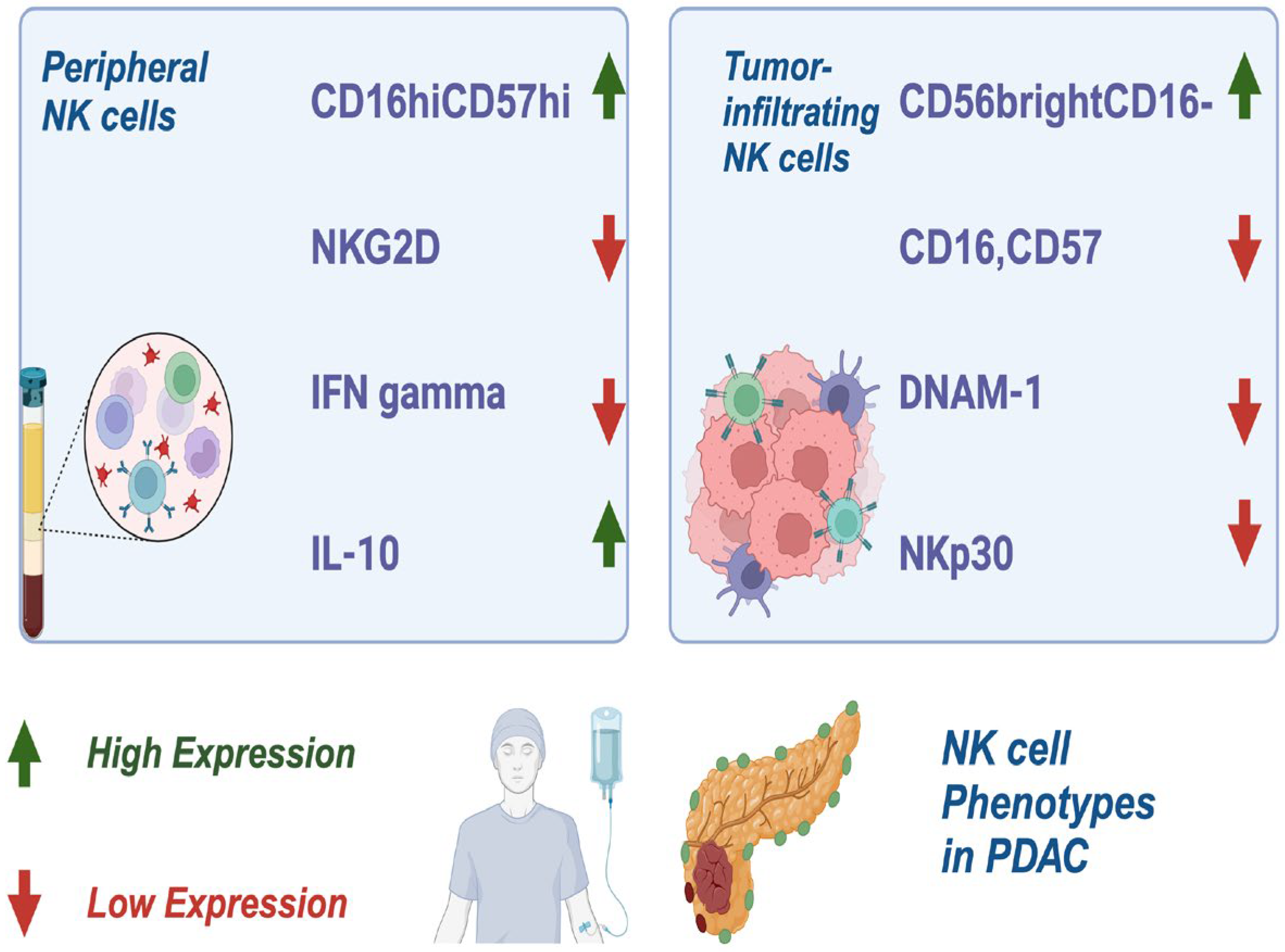

8]. In PDAC, peripheral NK cells exhibit a distinct phenotype characterized by CD16^hiCD57^high expression, reduced levels of NK group 2D receptor (NKG2D), low interferon-gamma (IFN-

γ) production, and elevated intracellular interleukin (IL)-10 [

9]. Tumor-infiltrating NK cells, in contrast, show downregulation of CD16, CD57, DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1), and NK cell p30-related proteins (NKP30), all of which impair their cytotoxic functions. Interestingly, CD56brightCD16 NK cells, a less cytotoxic phenotype, are often the predominant NK cell population in PDAC [

10] (

Figure 2).

In this figure, the distinct phenotypes of NK cells in PDAC are illustrated. Peripheral NK cells are characterized by high expression of CD16^hiCD57^high, reduced NKG2D receptor levels, low IFN-γ production, and elevated intracellular IL-10. Tumor-infiltrating NK cells exhibit further downregulation of key markers such as CD16, CD57, DNAM-1, and NKP30, impairing their cytotoxic activity. Additionally, the less cytotoxic CD56^brightCD16 NK cell subset is shown as the predominant population within PDAC tumors, highlighting the immune dysfunction associated with this malignancy.

2.1. Tumor Characteristics and Their Impact on NK Cell Function

The molecular heterogeneity of PDAC plays a major role in immune evasion, tumor progression, and resistance to treatment [

3]. Key mutations, including KRAS activation and the inactivation of tumor suppressors like CDKN2A, p53, SMAD4, PTEN, DPC4, MYC, and BRCA, significantly contribute to tumor progression and metastasis [

11].

Notably, while these mutations promote cancer progression, they also suppress NK cell activity, with p53, MYC, RAS, and PTEN alterations having the most pronounced effects on NK cell function [

12,

13].

Additionally, CD155, an adhesion molecule highly expressed in PDAC tissues, further impedes NK cell function by reducing the presence of CD226^+ and CD96^+ NK cells, thereby promoting immune escape [

14]. Enzymes involved in NAD+ metabolism, such as nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), also contribute to NK cell inhibition and chemoresistance, further complicating treatment responses [

15].

Epigenetic alterations, including the methylation of CpG sites, have been identified as significant factors influencing NK cell function and serve as prognostic markers for PDAC [

16]. Transcription factors like GATA-binding protein 6 (GATA6) and pathways such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-

β) signaling are associated with poor prognosis and impaired NK cell activity in especially in GATA-low PDAC [

17]. GATA6 overexpression leads to the downregulation of stemness such as CD133, ALDH, SOX9, leading to increase NK cell activity [

18]. In contrast, One Cut Homeobox 3 (ONECUT3) reprograms somatic cells to acquire stemness characteristics, further inhibiting NK cell function and promoting immune evasion [

19].

The microbiota, particularly Gammaproteobacteria, has been shown to contribute to chemoresistance by inactivating gemcitabine, which leads to reduced NK cell infiltration [

20]. Furthermore, PDAC cells exhibit significant metabolic plasticity, primarily through glycolytic pathways (Warburg effect), which not only foster chemoresistance but also suppress NK cell activity [

21]. Calcium signaling, via purinergic receptor 7 (P2X7R) and related pathways, also plays a critical role in NK cell dysfunction and tumor survival [

22,

23].

2.2. TME Changes and Their Impact on NK cell Function

The TME plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of PDAC. It is a complex and dynamic environment, composed of cellular stroma, extracellular matrix (ECM) components, and various soluble factors that interact to influence tumor behavior. Within this environment, specific biochemical and cellular mechanisms such as stress and metabolic signaling have a profound impact on NK cells. These mechanisms not only suppress NK cell cytotoxicity but also hinder their ability to proliferate and infiltrate the tumor [

3].

2.2.1. Cellular Stroma-NK Cell Interaction

An overview of the cellular components of the PDAC TME and their impact on NK cell function is essential for understanding the immune landscape of pancreatic cancer. The cellular stroma, rich in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), creates a complex microenvironment that profoundly influences NK cell activity [

7]. PSCs, when activated by cytokines like TGF-

β, promote fibrosis and create a dense, rigid (desmoplastic) tumor stroma that impairs NK cell infiltration [

24,

25]. In addition, CAFs can secrete signaling molecules that inhibit NK cells by downregulating key factors such as IFN-

γ, perforin, and granzyme or by downregulating of key activating receptors like NKG2D and DNAM-1 [

26,

27]. In some cases, particularly in PDAC with low desmoplasia, the metabolic state of CAFs can further suppress NK cell function. For example, metabolic reprogramming in the stroma may lead to an immune- suppressive environment, where NK cells are less effective in killing tumor cells [

15,

26]. Additionally, the upregulation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in CAFs, whether through gene amplification or mRNA upregulation, has been associated with reduced NK cell activity, further complicating the immune landscape of PDAC [

27]. FAK and steroid receptor coactivator (FAK/Src) signaling pathways have also been identified as key regulators of NK cell suppression [

28]. The activation of these pathways in cellular stroma can exacerbate NK cell dysfunction, highlighting their critical role in shaping immune responses in PDAC.

NK cell exhaustion, a hallmark of impaired immune function in PDAC, is characterized by the loss of activating receptors such as NKG2D and the upregulation of inhibitory receptors like PD-1, TIM-3, NKG2A, TIGIT, and LAG-3 [

29]. Additionally, the proteolytic shedding of MICA/B proteins, which normally engage activating NK receptors, further ex- acerbates NK cell dysfunction [

30]. Within the TME of PDAC, CD11b+ NK cells represent a distinct subset that can contribute to both immune surveillance and immune evasion, de- pending on their activation state. The balance between these opposing functions plays a critical role in shaping the overall immune response to PDAC [

26].

The role of chemokine signaling on NK cell trafficking are crucial for understanding NK cell function in the TME. Chemokine signaling (e.g., CXCR2 and IL-1) in PDAC patients can impair NK cell migration to tumor sites [

31,

32]. The downregulation of CXCR2 on NK cells, coupled with CXCR4 overexpression in PDAC, further promotes NK cell suppression and contributes to treatment resistance [

33,

34].

The contribution of epigenetic modifications and transcription factors to NK cell dysfunction underscores the intricate relationship between the TME and immune evasion. Epigenetic modifications play a pivotal role in altering NK cell function and contribute to immune evasion. In particular, histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and changes in glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta (GSK3B), have been identified as key regulators of NK cell cytotoxicity [

35,

36]. Transcription factors, such as GATA-binding protein 6 (GATA6) and TGF-

β signaling, have also been shown to affect NK cell activity in PDAC and are associated with prognosis. In GATA6-low PDAC, these epigenetic changes contribute to impaired NK cell function. Conversely, GATA6 overexpression leads to the downregulation of stem- ness markers (e.g., CD133, ALDH, SOX9), which further enhances NK cell activity [

17,

18]. Other transcription factors, such as Cbl, NF-

κB, RUNX3, and STAT, also modulate NK cell function, underscoring the interplay between transcriptional regulation and immune responses in PDAC [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Similarly, HOXA9 and FOXO, have been found to alter NK cell function [

40,

41,

42].

Additionally, the effects of tumor angiogenesis and microRNAs (miRNAs) on NK cell activity within the TME are critical factors influencing immune function in PDAC. Tumor angiogenesis in PDAC, involving NK cells, has been shown to affect immune function. For instance, STAT5-deficient NK cells overproduce VEGF-A, leading to a reduction in NK cell cytotoxicity [

43]. MicroRNAs, including both oncogenic (ocomiRs) and tumor-suppressive (tsmiRs) miRNAs, also regulate NK cell function. These miRNAs impact pathways like PI3K, contributing to PDAC aggressiveness and NK cell dysfunction [

44,

45,

46,

47].

Metabolic modulators and metabolic reprogramming within the TME have a significant impact on NK cell function in PDAC. Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), an enzyme produced by immunoregulatory cells, inhibits the expression of key NK cell receptors such as NKG2D and NKp46, impairing NK cell activity through STAT signaling pathways in PDAC [

48]. Additionally, NAD+-related proteins like SIRT1 and the deacetylation of FOXO are other crucial metabolic modulators that alter NK cell function [

49]. Metabolic reprogramming within the TME, including lipid metabolism and high-fat diets, also affects NK cell activity, with signaling pathways like cholecystokinin (CCK) and peroxisome proliferator- activated receptors (PPAR) contributing to this dysfunction. Together, these metabolic changes create an immune-suppressive environment that further hinders NK cell-mediated anti-tumor responses. [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55].

Stress and calcium signaling are other critical factors influencing NK cell function in PDAC as well. Stress-induced signaling, such as the expression of MIC-A/B and ULBPs, impairs NK cell activity through IL-6 and STAT3 signaling pathways. Elevated IL-6 levels in PDAC are particularly concerning, as they are associated with reduced NK cell-mediated IFN-

γ secretion, which contributes to poor prognosis in PDAC patients [

56,

57]. Hypoxia is another key factor that alters NK cell function; under low oxygen conditions, HIF-1A is upregulated, leading to the downregulation of activating NK receptors such as NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, thereby promoting NK cell suppression [

8]. Additionally, the expression of CD73 in response to hypoxia further inhibits NK cell activity [

58]. Calcium signaling, particularly through channels like Orai1, STIM1, and P2X7, plays a role in chemotherapy resistance, with PSCs secreting IL-6 to increase store-operated calcium entry (SOCE), which further suppresses NK cell activity and promoting PDAC aggressiveness [

59,

60,

61].

This structure allows for a more holistic understanding of how diverse stromal components and molecular pathways contribute to NK cell suppression and immune resistance in PDAC.

2.2.2. Extracellular Matrix (ECM)-NK Cell Interaction

The ECM plays a critical role in shaping the progression of PDAC and influencing NK cell function. Key ECM components such as collagen, proteoglycans, elastin, and integrins (e.g.,

α2

β1 and

αV

β3) are essential not only in tumor development but also in modulating NK cell behavior [

62,

63,

64]. The ECM provides structural support to the tumor while actively contributing to tumor growth, metastasis, and immune responses. One of the major ECM remodeling mechanisms in PDAC involves matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which de- grade ECM components, facilitating tumor cell invasion and migration. This remodeling of the ECM can also affect NK cell activation and has been identified as a potential predictive marker for PDAC prognosis [

65,

66].

Signaling pathways within the ECM contribute significantly to immune suppression in PDAC. Hyaluronic acid, Sonic Hedgehog (Shh), and Src/FAK signaling play important roles in desmoplasia, hypoxia, and angiogenesis, creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment that enhances PDAC progression and drug resistance [

67,

68]. In PDAC, KRAS mutations are frequently observed, activating both Shh and NF-

κB pathways. Studies on MT-KRAS PDAC models and BxPC-3 cells show significant activation of these pathways, while wild-type KRAS cells exhibit minimal or no activation. Silencing KRAS in MT-KRAS cells reduces the activation of these pathways, underscoring their dependence on KRAS mutations. These pathways not only promote tumor growth but also contribute to NK cell suppression, suggesting that KRAS mutations are crucial in regulating immune evasion mechanisms within the TME [

69].

Furthermore, the Src/FAK pathway, activated by growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth fac- tor (FGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), enhances tumor cell survival and immune escape [

70]. Another important signaling mechanism in PDAC is TGF

β signaling, which acts at both the cellular and ECM levels and is implicated in promoting immune suppression and treatment resistance. Although targeting TGF

β and Shh pathways has shown promise in preclinical studies, clinical application remains controversial due to mixed results [

71].

In addition to these signaling pathways, stress-induced mechanisms such as the creation of a fibrotic stroma, hypovascularization, and immunosuppression further complicate treatment resistance in PDAC. The ECM environment, in combination with these stress factors, impairs NK cell function and limits the effectiveness of therapies [

72]. For instance, Death-Associated Protein 1 (DAP1), a modulator of autophagy, has been linked to treatment resistance in PDAC. DAP1 expression is low in several malignancies, including PDAC, and its potential role in influencing NK cell functionality and therapy resistance is an emerging area of research [

73].

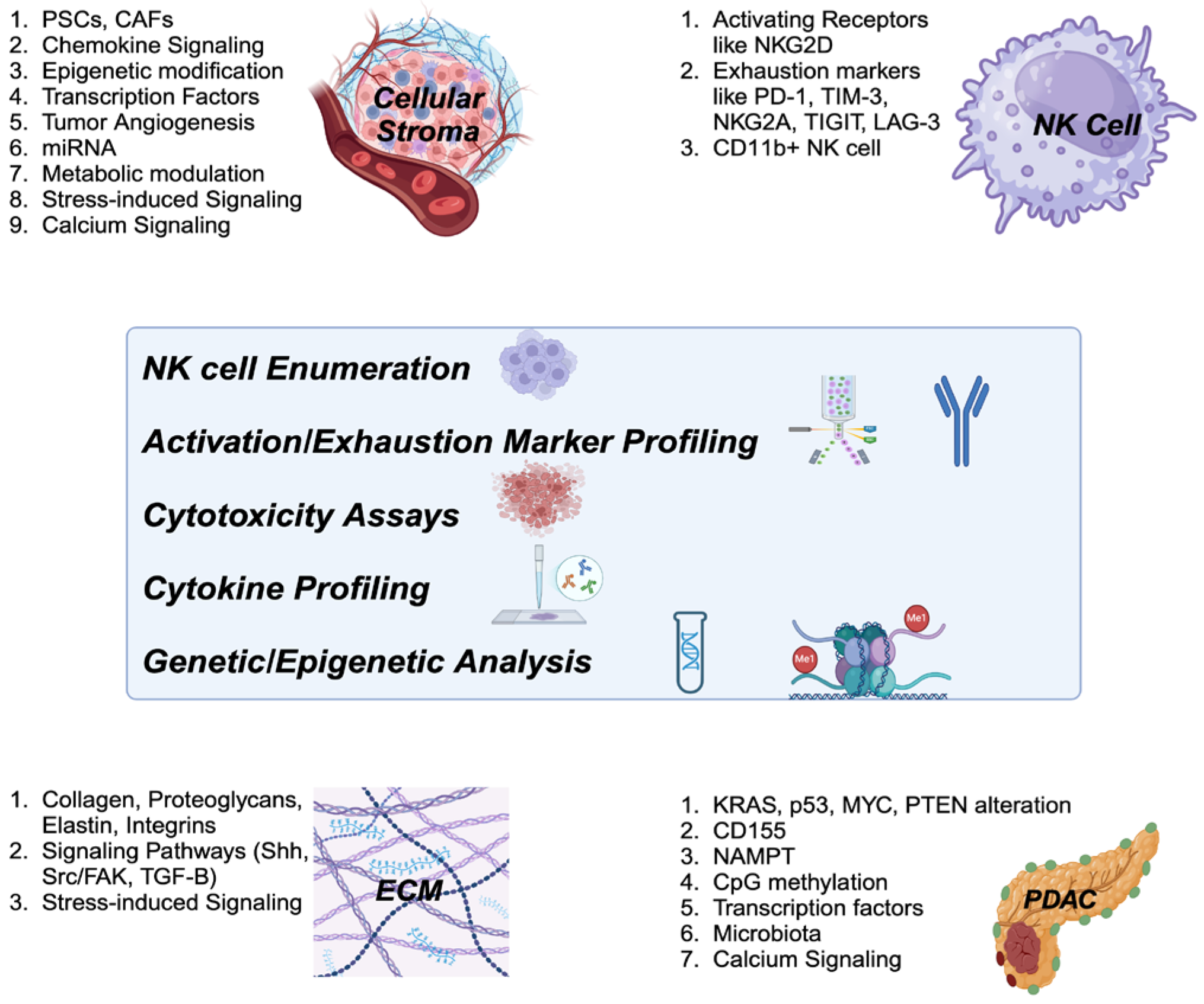

The diagnostic approach to assessing NK cell function provides crucial insights into the immune landscape of cancer, particularly PDAC. Diagnostic approaches such as NK cell enumeration, activation/exhaustion marker profiling, cytotoxicity assays, cytokine profiling, and genetic/epigenetic analyses can provide valuable insights into NK cell activity within the TME. Understanding the etiology of NK cell suppression in the context of PDAC, particularly focusing on tumor characteristics and TME changes, is essential for designing the most effective diagnostic approaches (

Figure 3). This knowledge helps identify immune dysfunction and guides the selection of NK cell-related biomarkers for accurate prognosis and therapeutic decisions. It also aids in the development of personalized immunotherapies, such as NK cell-based treatments and immune checkpoint inhibitors, and supports monitoring treatment responses, ultimately improving patient outcomes and advancing precision oncology.

This figure outlines the diagnostic strategies for assessing NK cell function in the context of cancer, particularly PDAC. Approaches such as NK cell enumeration, profiling of activation and exhaustion markers, cytotoxicity assays, cytokine profiling, and genetic/epigenetic analyses provide essential information on NK cell activity within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Understanding the underlying causes of NK cell suppression in PDAC, with a focus on tumor-specific characteristics and TME alterations, is key to developing effective diagnostic methods.

3. NK cells: Therapeutic Potential

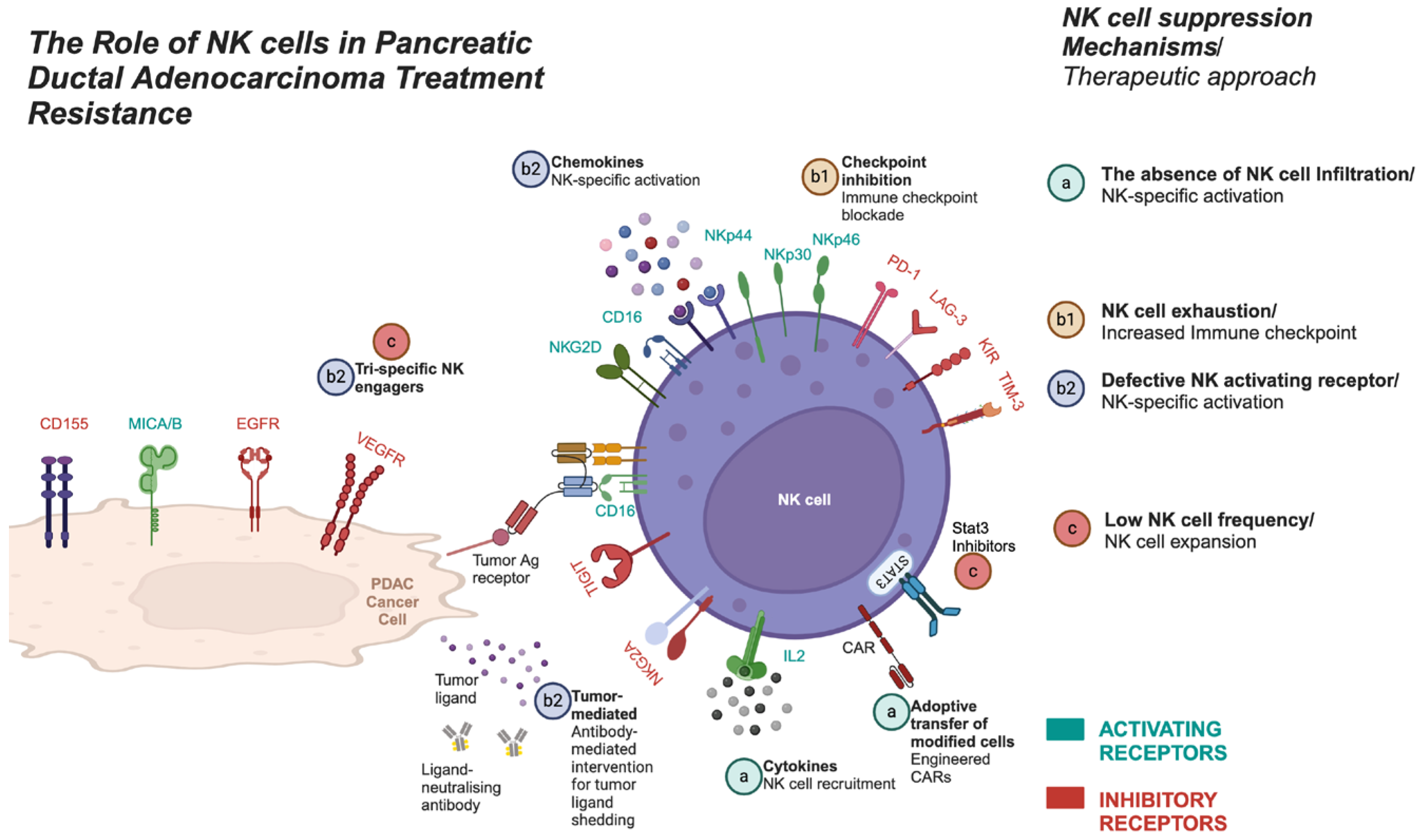

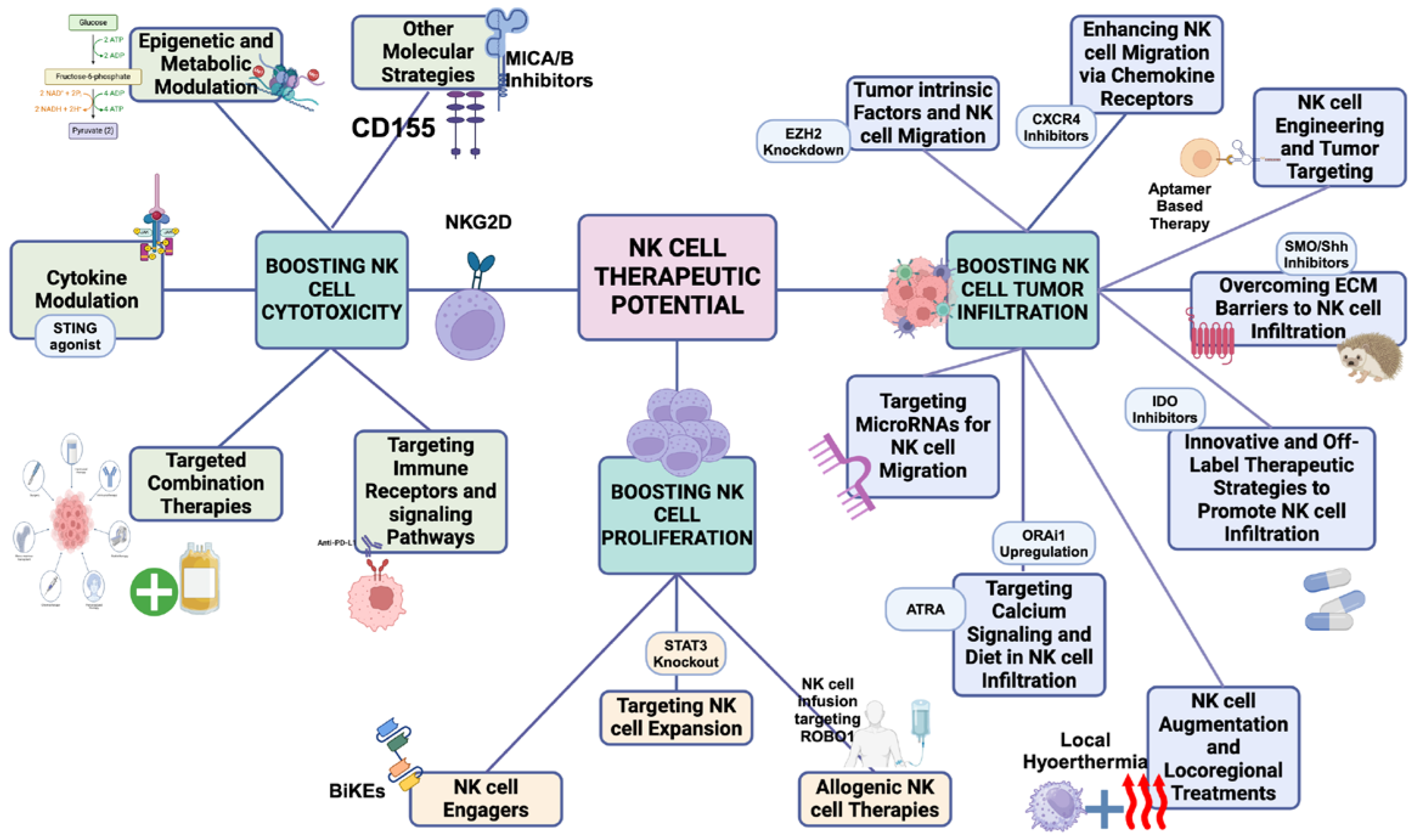

Understanding PDAC treatment resistance is crucial, especially when addressing the main suppressive mechanisms within tumor and the TME that limit NK cell function. These include reduced NK cell cytotoxicity, impaired proliferation, and limited tumor infiltration (

Figure 4). Efforts to counter these suppressive factors have led to various therapeutic strategies (

Figure 5 ) targeting tumor cells, cancer stem cells, ECM remodeling, and enhancing NK cell activity in PDAC [

74,

75]. Enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity, increasing NK cell frequency, and improving tumor infiltration are pivotal strategies for optimizing therapeutic outcomes in PDAC. Notably, chemotherapy (e.g., gemcitabine) has shown potential in increasing NK cell activity [

76], but the challenge remains to overcome resistance and optimize NK cell function within the PDAC TME. Understanding how these strategies impact the phenotypic subtypes of PDAC (E/QM states) is crucial. For example, FOLFIRINOX, one of the most effective therapies for PDAC, can initially provide significant therapeutic benefits. However, over time, it may drive tumor subtypes toward a more immunosuppressive mesenchymal state, ultimately reducing NK cell activity and contributing to treatment resistance. In contrast, therapies like vitamin D have shown promise in reducing EMT, enhancing NK cell function and potentially mitigating some of the immunosuppressive effects within the TME [

77,

78].

This figure illustrates the three main mechanisms by which NK cell activity is suppressed—low NK cell proliferation, tumor infiltration, and NK cell cytotoxicity—along with strategies to address each of these suppression mechanisms:

a) NK cell tumor infiltration defects:The first mechanism depicts impaired NK cell infiltration into tumors. Strategies to overcome this include NK cell recruitment and adoptive transfer using CAR NK cells. b1) NK cell exhaustion: NK cell exhaustion is characterized by the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules like PD-1, which reduce NK cell cytotoxicity. Immunotherapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors, can help reverse this exhaustion. b2) Defective activatory receptor signaling:This mechanism addresses defective or inhibitory activatory receptor signaling. Blockade of inhibitory receptors (e.g., KIRs, NKG2A) and activation of NK cell receptors using NK cell engagers can enhance NK cell function. c) Low NK cell frequency:The third mechanism illustrates diminished NK cell abundance. This can be targeted by STAT3 inhibitors, which promote NK cell expansion. Additionally, NK cell engagers can be used to stimulate NK cell proliferation, further enhancing their presence and activity.

This figure outlines various therapeutic strategies to enhance NK cell function in cancer treatment, categorized into three key goals: Boosting NK cell cytotoxicity, boosting NK cell proliferation, and promoting NK cell tumor infiltration.

Boosting NK cell cytotoxicity (left section): Strategies focus on enhancing NK cell killing activity, including epigenetic and metabolic modulation, cytokine modulation, immune checkpoint inhibition, targeted combination therapies, and immune receptor signaling pathway targeting to activate NK cells and improve tumor response.Boosting NK cell proliferation (middle section): Approaches aimed at expanding NK cell numbers, such as NK cell expansion, NK cell engagers, and allogeneic NK cell therapies, to strengthen immune responses. Promoting NK cell tumor inftltration (right section): Methods to enhance NK cell migration into tumors, including targeting tumor-intrinsic factors, chemokine receptor modulation, NK cell engineering, overcoming ECM barriers, and exploring innovative therapies to improve NK cell infiltration and effectiveness.

3.1. Boosting NK cell cytotoxicity

Enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity is central to overcoming immune suppression in PDAC. Several therapeutic strategies aim to activate NK cells and bypass immunosuppressive barriers, improving their ability to eliminate tumor cells. Key strategies include epigenetic modulation, metabolic modulation, cytokine modulation, and targeting immune checkpoints.

3.1.1. Epigenetic and Metabolic Modulation

Targeting epigenetic regulators such as EZH2, a histone methyltransferase, can enhance NK cell killing activity by reversing immune-suppressive factors in PDAC. EZH2 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through interaction with SNAI1 (Snail), down- regulating E-cadherin and suppressing NK cell function. Inhibiting of EZH2 can restore NK cell activity and promote NK cell-mediated killing of PDAC cells [

79]. Moreover, hi- stone acetyltransferase (HAT) inhibitors (e.g., curcumin), HDACs blockers, and IDH1/2 inhibitors are being explored for their potential to enhance NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in PDAC [

80]. These epigenetic modulators offer a potential avenue for activating NK cells and improving immune responses in PDAC. Preclinical studies have also indicated that simultaneous inhibition of GSK3B and HDACs can enhance gemcitabine-induced apoptosis by NK cells [

81].

In addition, metabolic modulation has emerged as a promising strategy for enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity in PDAC. NAD+ supplementation, combined with STING agonists and type I interferon signaling, activate NAD-consuming enzymes and enhances PDAC sensitivity to therapies like NAMPT inhibitors, boosting NK cell function [

82]. Modifying the NAD+/NADH ratio can also induce apoptosis and enhance the effects of metformin in PDAC by targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs) [

83]. Metformin has shown potentiai in enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity in other cancers [

84], and in PDAC. Sancho et al. used metformin as a mitochondrial-targeted agent to target PDAC CSCs, demonstrating that targeting MYC can sensitize resistant CSCs to metformin [

75].

3.1.2. Cytokine Modulation

Cytokines play a critical role in regulating NK cell function and modulating the immune response in PDAC. IL-12 has been shown to enhance NK cell cytotoxicity, while blockading IL-10 can reduce NK cell suppression and boost antitumor immunity in PDAC and other tumors [

85,

86]. In addition, in poorly differentiated high-grade PDAC, particularly with a mesenchymal subtype, elevated secretion of colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) promotes the differentiation of monocytes into anti-inflammatory M2-like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). These M2-like TAMs facilitate tumor progression and immune sup- pression [

87]. However, CSF-1 inhibitors can shift TAMs toward an M1-like phenotype, which secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1

β, IFN-

γ, and IL-15, thereby enhancing NK cell function and antitumor immunity [

88,

89].

Combination therapies using cytokines for enhanced NK cell cytotoxicity have shown promise in boosting NK cell cytotoxicity in PDAC. For instance, combining cetuximab with IL-21 has significantly enhanced NK cell activity in EGFR-positive PDAC, regardless of KRAS mutation status [

90].

Additionally, the STING pathway has been identified as a potential target for enhancing NK cell function. Activation of the STING pathway, particularly through the use of STING agonists like DMXAA, has been shown to promote type I interferon (IFN-I) responses and improve the antitumor properties of NK cells. In combination with gemcitabine, STING agonists may stimulate the immune system by promoting inflammatory cytokine production, further enhancing the immune response against PDAC [

70,

91].

Another strategy to boost NK cell function in PDAC is the use of combing NK cells with TGF-

β neutralizers. TGF-

β is an immunosuppressive cytokine that often contributes to immune evasion in the tumor microenvironment. By neutralizing TGF-

β, the immune response can be enhanced, and NK cell activity can be restored, promoting better tumor elimination [

71,

92].

3.1.3. Targeted Combination Therapies

Targeted combination therapies aim to enhance NK cell cytotoxicity and improve tumor elimination in PDAC by utilizing multiple modalities. The coordinated activation of

NKG2D, DNAM-1, and natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) plays a significant role in NK cell-mediated elimination of PDAC tumor cells [

31]. In parallel, targeting STAT3 on NKp46+ cells has been shown to enhance NK cell cytotoxicity [

93], providing another avenue for therapeutic intervention.

Co-administration of trastuzumab, rituximab, and the anti-TIGIT monoclonal antibody BMS-986207 has been demonstrated to increase NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [

94].

Locoregional and inhibitory interventions such as FAK inhibition, are increasingly being explored as methods to counteract the immunosuppressive and fibrotic characteristics of the PDAC TME [

95]. In an animal model of PDAC, a combination of checkpoint immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and FAK inhibition led to a complete response and long-term survival [

96]. FAK inhibitors boost immune surveillance by reversing the fibrotic, immuno- suppressive properties of the PDAC TME, thus increasing the tumors’ responsiveness to immunotherapy [

97,

105]. Notably, FAK inhibition has been shown to enhance the sensitivity of PDAC cells to radiation in laboratory settings [

98], providing a promising prospective therapeutic approach for clinical use.

3.1.4. Targeting Immune Receptors and Signaling Pathways

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, in combination with other modalities, have shown promising potential in modulating immune responses in PDAC, particularly for overcoming the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. For example, the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab, when combined with the CD40 agonist sotigalimab and gemcitabine/nano-albumin-bound paclitaxel, has been shown to enhance NK cell-mediated tumor destruction and improve overall treatment efficacy [

99]. By targeting PD-L1, durvalumab helps reverse immune sup- pression within the TME, enabling NK cells and other immune cells to better target and eliminate cancer cells. In addition to PD-L1, other immune checkpoint molecules such as TIM-3 and TIGIT are also being explored as potential targets to further enhance NK cell cytotoxicity and improve therapeutic outcomes [

100,

101].

Another strategic approach involves using PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors to prevent NK cell exhaustion, thereby enhancing their antitumor activity in PDAC [

102]. Clinical trials are currently evaluating combinations of VEGFR inhibitors with anti-PD-L1 therapies in solid tumors, including PDAC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03797326, NCT04887805) [

103]. Additionally, a case report showed a complete response in a heavily pretreated PDAC patient following treatment with a combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab. These results underscore the potential of checkpoint inhibitors, like those targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and TIM-3, in restoring NK cell function and improving tumor elimination [

100,

101,

104].

Moreover, targeting signaling pathways, such as pyruvate kinase muscle 2 (PKM2), which regulates PD-L1 expression, could further enhance NK cell function and overcome resistance in PDAC [

105]. Studies also suggest that combining Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene-transduced autologous pancreatic cancer vaccines (GVAX) with CSF-1R inhibitors and anti-PD-1 therapy can increase IFN-

γ levels and enhance NK cell cytotoxicity [

106]. Additionally, blocking both IL-6 and PD-1 has been shown to increase antitumor activity, likely due to enhanced NK cell cytotoxicity [

57].

Supplementarily, manipulating signaling pathways represents another promising avenue for augmenting NK cell function. Targeting diacylglycerol kinase (DGK)

ζ, a negative regulator of NK cell activity, is one of the promising strategy for modulating signaling pathways to enhance NK cell function in PDAC and recent studies are exploring the use of DGK inhibitors to improve NK cell-mediated tumor elimination [

107]. Similarly, post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination, have been shown to alter NK cell signaling [

108]. For instance, Cbl knockdown can decrease Vav protein ubiquitination, leading to increased NK cell killing activity, highlighting a novel avenue for enhancing NK cell function in PDAC [

109].

3.1.5. Other Molecular Strategies

Several novel molecular strategies are being explored to regulate NK cell activity and enhance immune responses in PDAC. For example, CD73, a membrane-bound nucleotidase that generates extracellular adenosine, plays a key role in immune suppression. Inhibition of CD73 by diclofenac has shown promising results in managing PDAC metastasis, demonstrating greater efficacy than CD73-blocking antibodies. Furthermore, diclofenac has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of gemcitabine, promoting NK cell activity in PDAC models and possibly improving overall therapeutic outcomes [

110].

A preclinical study demonstrated that low-dose gemcitabine treatment leads to increased MICA/B expression, enhancing NK cell function in PDAC, rather than directly promoting cytotoxicity [

111]. However, inhibiting the cleavage and release of MIC molecules from the tumor surface could potentially enhance NKG2D-dependent cytotoxicity [

30].

Other strategies involve targeting alternative splicing of CD155, which may help over- come immune evasion by tumor cells [

112]. Targeting the complement system pathway may provide an additional mechanism to combat drug resistance in PDAC. This strategy could help modulate the immune environment, increasing NK cell activity and tumor cell recognition [

113].

Lastly, the use of aptamers, small single-stranded oligonucleotides, may assist in remodeling immune cell phenotypes from a protumor to an antitumor state, enhancing the immune system’s ability to fight cancer [

114].

3.2. Boosting NK Cell Proliferation

Increasing NK cell proliferation has been shown to correlate with improved outcomes in various cancers, including PDAC [

115]. Several strategies have been explored to enhance NK cell numbers and their functional activity, particularly in solid tumors like PDAC. These strategies can be categorized into three main approaches: targeting NK cell expansion, using NK cell engagers, and utilizing allogeneic NK cell therapies.

3.2.1. Targeting NK Cell Expansion

One approach to boosting NK cell numbers involves directly modulating their expansion. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of targeting specific molecules to increase NK cell proliferation. For example, antibodies targeting CD3 and CD52 have been shown to increase the abundance of effector NK cells in the peripheral blood of PDAC mouse models [

116]. Additionally, knocking out the STAT3 pathway has been shown to increase the proliferation of cytotoxic NK cells, thereby enhancing their tumor-killing capacity [

93]. These findings underscore the importance of targeting key signaling pathways to promote NK cell expansion.

3.2.2. NK Cell Engagers

Another promising strategy for enhancing NK cell proliferation is the use of NK cell engagers, such as bi-specific and tri-specific NK cell engagers (BiKEs and TriKEs). These engineered molecules are designed to bring NK cells in close proximity to tumor cells, facilitating more efficient tumor-targeting and promoting NK cell proliferation [

93,

117]. By engaging multiple targets simultaneously, BiKEs and TriKEs not only boost NK cell numbers but also enhance their tumor-killing capacity, making them an exciting therapeutic avenue for PDAC and other cancers.

3.2.3. Allogeneic NK Cell Therapies

Allogeneic NK cell-based therapies are emerging as a promising approach for treating solid tumors, including PDAC. A number of studies have investigated the safety and efficacy of NK cell infusion therapies. For instance, in a study focused on PDAC with liver metastasis, NK cell infusion targeting the roundabout guidance receptor 1 (ROBO1) was found to be safe and led to stable disease in patients following five months of weekly infusions [

118,

119,

120]. Further supporting this approach, ROBO1 was overexpressed in liver metastatic CK19+ PDAC cells, suggesting that targeting ROBO1 with NK cell therapies could effectively overcome metastatic spread in PDAC [

22,

119].

3.3. Promoting NK Cell Tumor Infiltration

In PDAC tumors, NK cells are often scarce, accounting for less than 0.5% of the immune cell population, which contributes to the poor prognosis of the disease. Since mutations in the KRAS gene are the earliest genetic variation in PDAC [

120] and lead to a loss of NK cells in precancerous stages, several strategies to enhance NK cell tumor infiltration [

121] and NK adoptive cell transfer are being explored as promising therapeutic interventions. These approaches focus on modulating tumor-intrinsic factors, chemokine pathways, and the tumor microenvironment (TME) to improve NK cell presence in tumors and overcome therapeutic resistance.

3.3.1. Tumor-Intrinsic Factors and NK Cell Migration

Tumor-intrinsic factors play a critical role in NK cell migration and infiltration. For example, EZH2 knockdown or the combination of EZH2 blockade with senescence-inducing therapies, such as trematinib/palbociclib, has resulted in increased NK cell migration and even complete responses in some PDAC mouse models [

122]. Research by Hu et al. further demonstrated that enhancing NK cell infiltration into tumors led to increased tumor necrosis and prolonged survival in PDAC mouse models, compared to controls [

123].

3.3.2. Enhancing NK Cell Migration via Chemokine Receptors

Modifying the chemokine receptor environment is another effective strategy to improve NK cell infiltration. For example, CXCR2 ligands or CXCR4 blockade have been shown to enhance NK cell recruitment into PDAC tumors [

31,

33]. Interferons stimulate the release of CXCL10, which further promotes NK cell migration toward the tumor site [

124]. A clinical trial is exploring the combination of NOX-A12, a CXCL12 antagonist, with pembrolizumab in PDAC to enhance NK cell recruitment and improve immune responses by both directly targeting the tumor-promoting chemokine CXCL12 and releasing the brakes on the immune system [

125].

3.3.3. NK Cell Engineering and Tumor Targeting

NK cell engineering also holds promise for improving NK cell infiltration and targeting PDAC cells. One such strategy involves using aptamers to attach and modify NK cells to facilitate targeting toward cancer cells [

126]. NOX-A12, an aptamer targeting CXCL12, is currently undergoing clinical trials for PDAC treatment. By blocking CXCL12, NOX-A12 aims to disrupt the tumor-promoting microenvironment, hinder cancer progression, and enhance NK cell activity [

45].

Another innovative approach is the use of NK-cell-recruiting protein-conjugated antibodies (NRP-bodies). These antibodies can induce NK cell infiltration into tumors by binding to CXCL16, while simultaneously activating Ras Homolog Family Member A (RhoA) through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling cascade, further boosting NK cell- mediated tumor targeting [

127].

3.3.4. Overcoming ECM Barriers to NK Cell Infiltration

The ECM is a significant barrier to NK cell infiltration in PDAC, and targeting ECM- related resistance mechanisms in PDAC, including desmoplasia, may also serve as a viable modality to combat chemoresistance, as improved penetration and NK cell are anticipated outcomes. Several strategies like the use of MMP inhibitors [

128], hyaluronidase, Shh inhibitors, fibroblast activation protein (FAP) targeting agents, and CXCR4 inhibitors have been discussed to managing therapeutic resistance in PDAC [

3]. For example, the application of IPI-269609, a potent hedgehog inhibitor, has shown promise in controlling tumor growth; however, it does not potentiate the effect of gemcitabine [

129]. In contrast, Saridegib (IPI-926), a newer class of hedgehog inhibitors and a potent smoothened (Smo) receptor antagonist, has improved chemotherapy delivery by normalizing the tumor vasculature [

130]. Blocking the Src/FAK pathway with VS-4718 has been shown to decrease the density of the ECM and potentiate the effect of chemotherapy [

27,

28,

96,

97,

98]. Additionally, vitamin D analogs have been shown to increase the concentration and efficacy of gemcitabine by reducing tumor-associated fibrosis and increasing NK cell activity [

131,

132].

By targeting molecules like BRD4 and CD11b, we can modulate the TME, which helps address barriers like desmoplasia (fibrosis) and other ECM-related factors that restrict immune cell infiltration. CD11b agonists reconfigure innate immunity, making PDAC more responsive to immunotherapies [

133]. Findings from two preclinical models of PDAC high- light the potential of using a bromodomain inhibitor to simultaneously target both the tumor and its microenvironment. Additionally, this research reveals that Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), which regulates gene expression and influences various cellular processes including NK cell migration, is essential in shaping the TME in the liver, a critical site for metastasis in PDAC [

134].

3.3.5. Innovative and Off-Label Therapeutic Strategies to Promote NK Cell Infiltration

Innovative therapies are also being explored to enhance NK cell infiltration in PDAC. Salmonella-based therapy coupled with enzymatic depletion of tumor hyaluronan using PEGPH20 for targeting IDO, have resulted in complete regression of PDAC [

135]. A combination of IDO inhibitors and vaccine therapy is also under investigation in PDAC, showing promise in overcoming immune resistance [

136].

Concurrently, therapy involving CCK-receptor antagonists has the potential to diminish tumor-associated fibrosis in PDAC, thereby boosting the effectiveness of immune checkpoint antibody therapy in PDAC mouse models [

51,

137] ProAgio is also currently under investigation as a potential therapeutic target for reducing tumor-associated fibrosis in patients with PDAC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05085548) [

138].

As an extension of these approaches, tumor fibrosis is an important prognostic factor in PDAC, and reducing fibrosis while boosting NK cell migration could enhance immune cell infiltration into tumors. The phenotyping of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), including inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), myofibroblast-like CAFs (myCAFs), and mesenchymal CAFs (meCAFs), is crucial for understanding and targeting the TME. Interestingly, inhibitors of the JAK/STAT pathway have been shown to increase the myCAF to iCAF ratio, resulting in better tumor control [

92]. Moreover, the presence of meCAFs has been linked to improved NK cell infiltration and responses to gemcitabine/nano-albumin-bound paclitaxel/anti-PD-1 therapy in PDAC patients [

139].

Furthermore, off-Label therapeutic strategies combined with chemotherapy has been shown to enhance NK cell infiltration into tumors. For instance, Losartan, a conventional antihypertensive agent, was shown to reduce fibrosis by preventing the expression of TGF-

β [

140], and its efficacy was tested in combination with FOLFIRINOX in PDAC patients, yielding satisfying results [

141].

3.3.6. NK Cell Augmentation and Locoregional Treatments

Combining various locoregional treatments with NK cell augmentation may also enhance NK cell tumor infiltration in PDAC, while simultaneously increasing cytotoxicity. Modalities such as local hyperthermia using radiofrequency ablation, irreversible electroporation, and focused ultrasound-derived cavitation are being explored for their ability to improve NK cell infiltration [

95]. Notably, a study by Gauthier et al. developed a potent tri-specific NK cell engager (TriKE) to target a tumor-specific antigen and two receptors on NK cells (NKp46 and CD16). By engaging these receptors, TriKEs direct NK cells toward tumor cells, enhancing their ability to target and destroy cancerous cells effectively [

142]. Therefore, this combination approach may lead to more effective tumor targeting and better therapeutic outcomes in PDAC.

3.3.7. Targeting Calcium Signaling and Diet in NK Cell Infiltration

Targeting calcium signaling is another promising approach to enhance NK cell infiltration. Identifying and targeting specific components of the Ca2+ toolkit through pharmacological agents or gene therapies may offer potential avenues for therapeutic intervention. In the context of PDAC treatment, both gemcitabine and 5-fluorouracil have been found to upregulate ORAi1, a key protein involved in SOCE, which influences tumor–TME inter- actions and enhances NK cell infiltration. These findings suggest a potential link between SOCE-mediated Ca2+ signaling and the response to chemotherapy in PDAC [

24,

59].

Furthermore, understanding the complex interaction between dietary factors, CCK signaling, and other elements such as hypoxia signaling can aid in the development of new therapeutic modalities to overcome resistance in managing PDAC [

51,

127]. Interestingly, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), an active metabolite of vitamin A, can alter PSCs, potentially preventing matrix remodeling and reducing cancer cell invasion, thereby indirectly supporting NK cell tumor infiltration [

25].

3.3.8. Targeting MicroRNAs for NK Cell Enhancement

Manipulating microRNAs offers a promising strategy for enhancing NK cell function. For instance, microRNA-301a was found to be upregulated in human PDAC tissues, promoting NF-

κB activation and tumor growth. Inhibiting microRNA-301a or increasing Nkrf levels can reduce NF-

κB target gene expression and indirectly enhance NK cell infiltration, which could slow xenograft tumor growth [

143]. MicroRNA-26a has been shown to inhibit the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process by downregulating EZH2 expression, reducing NK cell suppression, and improving the outcomes of immunotherapy [

79,

144]. Also noteworthy, this strategy not only addresses the tumor’s invasive characteristics but also aims to enhance the efficacy of existing immunotherapies by promoting a more favorable immune environment. Consequently, the exploration of microRNA-26a as a therapeutic agent in PDAC could represent a promising avenue for overcoming resistance and improving patient outcomes.

4. Discussion, Conclusion and Future Directions

PDAC remains one of the most challenging malignancies due to its intrinsic phenotypic heterogeneity, complex TME, and associated therapeutic resistance. Despite certain genomic uniformity, PDAC tumors exhibit significant variability in immune landscape, cellular components, and therapeutic responses, which complicates treatment approaches. These challenges underscore the need for personalized tumor-TME phenotyping, which could predict treatment responses and guide the design of more effective multi-target therapies.

Genomic alterations, including mutations in key oncogenes like KRAS, p53, and MYC, along with metabolic modulation and epigenetic changes such as the overexpression of factors like NAMPT and ONECUT3, and low expression of GATA6 play pivotal roles in suppressing NK cell function and promoting tumor progression in PDAC [

11,

15,

19]. These modifications lead to immune evasion, where NK cells are rendered less effective, contributing to therapeutic resistance. Specifically, mutations in KRAS lead to increased activation of pathways such as Shh and NF-

κB, which further suppress NK cells tumor infiltration and their cytotoxicity, exacerbating tumor growth and limiting the efficacy of current treatments [

67,

69,

129,

130]. The immunosuppressive TME in PDAC is a critical factor in NK cell dysfunction. In PDAC, NK cells are subjected to multiple mechanisms of dysfunction, including impaired proliferation, diminished cytotoxicity or exhaustion, and diminished infiltration. These issues arise largely from the presence of immunosuppressive molecules like TGF-

β [

24,

25], IDO [

48], and immune checkpoint proteins (PD-1, TIM-3, TIGIT) [

29]. NK cell augmentation through strategies like STAT3 knockout or FAK inhibition has shown promise in increasing NK cell frequency and enhancing cytotoxicity [

93]. Despite challenges like MICA/B shedding and the potential for excessive NK cell accumulation, strategies to increase the surface expression of MICA/B on tumor cells could allow NK cells to more specifically target cancer cells [

28,

30]. Combination therapies, including those that combine immune check-point inhibitors (e.g., PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors) with chemotherapies are currently under investigation [

99]. These approaches aim to overcome NK cell exhaustion and increase their ability to target and eliminate PDAC cells.

Overcoming ECM barriers to NK cell infiltration is also crucial for enhancing NK cell- mediated immune responses in PDAC. The dense, fibrotic nature of the ECM, characterized by the presence of CAFs and increased ECM proteins like collagen, creates mechanical barriers that restrict the movement of immune cells into tumors [

3,

7]. To overcome these barriers, various strategies have been explored, such as using MMP inhibitors, hyaluronidase, and agents that target FAK signaling or CD11b modulators to degrade the ECM and facilitate NK cell infiltration [

27,

48,

97,

98,

128,

133]. Additionally, targeting CAFs and enhancing NK cell function represents a promising dual strategy to improve the immune response in PDAC. By reducing CAFs, which are major contributors to immunosuppression and fibrosis, and boosting NK cell infiltration, this approach can enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy and immunotherapy [

92]. Targeting immune checkpoint proteins, such as TIM-3 or TIGIT, in combination with therapies that modulate CAF activity, could further enhance NK cell-mediated tumor clearance. The success of such combination therapies could be greatly enhanced by identifying specific CAF subtypes (e.g., myCAFs vs. iCAFs) that regulate tumor progression and immune responses. Modifying the chemokine receptor environment is another promising strategy to promote NK cell infiltration. The use of therapies targeting the chemokine receptor environment, such as CXCR2 ligands, CXCR4 inhibitors or aptamers, has demonstrated potential in increasing NK cell recruitment into PDAC tumors. Notably, NOX-A12, a CXCL12 antagonist, in combination with pembrolizumab, is currently being explored in clinical trials to enhance NK cell recruitment and improve immune responses [

122,

125].

Off-label drugs like metformin, losartan, and diclofenac have also shown potential to enhance NK cell activity, suggesting that pharmacological modulation of the TME, along with conventional therapies, can lead to better clinical outcomes in PDAC [

75,

110,

141]. The use of Vitamin D analogs, have been suggested to reduce EMT and tumor-associated fibrosis, further enhancing NK cell activity and improving treatment outcomes with FOLFIRI- NOX [

77,

78].

Innovative NK cell-engaging therapies, such as bi-specific and tri-specific NK cell engagers

(BiKEs and TriKEs), provide another exciting avenue for boosting NK cell activity. These engineered molecules can direct NK cells to tumors more effectively, potentially overcoming the challenges posed by NK cell exhaustion or inadequate tumor targeting. In addition, strategies like CAR NK cell therapy are being explored to modify NK cells to better recognize and kill tumor cells. These strategies, when combined with other therapies that address the TME, offer significant promise for improving NK cell function and clinical outcomes in PDAC [

88,

114,

142,

143,

144].

To overcome these barriers, a "triple NK cell biomarker approach" that integrates three key components of cancer—tumor characteristics, TME factors, and NK cell function—while focusing on the three primary mechanisms of NK cell suppression (diminished NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and tumor infiltration) is essential for understanding the mechanisms of therapy resistance and predicting treatment efficacy. This approach would provide valuable insights into how these factors interact to inhibit NK cell responses, helping to identify novel therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, the future of PDAC treatment relies on restoring NK cell function within both the tumor and the TME. This concept underscores the idea that cancer is, at its core, an immunologic disease rather than purely a genetic one. By employing a comprehensive, triple biomarker approach that identifies key biomarkers from the tumor, TME, and NK cells, we can begin to target crucial immune-suppressive pathways and reprogram the ECM. By targeting key immune-suppressive pathways, modulating the ECM, and developing innovative NK cell-engaging therapies, we can enhance the immune response against PDAC and improve clinical outcomes. Overcoming the challenges of NK cell engineering, improving their in vivo persistence, and integrating personalized immunotherapies will be essential for advancing the treatment of PDAC. Moving forward, the development of strategies that combine NK cell augmentation, ECM modulation, and reprogramming of the cellular stroma holds great potential for improving the efficacy of PDAC therapies.

Author Contributions

S.F contributes to the conceptualization and design of the review content. M.T. and L.H.J contributes equally to supervision. S.F. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read and approved the final submitted version. L.H.J provided funding acquisition for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- R. L. Siegel, K. D. Miller, H. E. Fuchs, Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA A, Cancer J Clin (2021). [CrossRef]

- P. Bailey, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer, Nature (2016). [CrossRef]

- W. J. Ho, E. M. Jaffee, L. Zheng, The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer- clinical challenges and opportunities, Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2020). [CrossRef]

- L. Bracci, G. Schiavoni, A. Sistigu, Immune-based mechanisms of cytotoxic chemotherapy: implications for the design of novel and rationale-based combined treatments against cancer, Cell Death Differ (2014). [CrossRef]

- T. Conroy, F. Desseigne, M. Ychou, FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer, N Engl J Med (2011). [CrossRef]

- V. Hoff, D. D. Ervin, T. Arena (2013). [link]. [CrossRef]

- B. Bassani, D. Baci, M. Gallazi, Natural Killer Cells as Key Players of Tumor Progression and Angio- genesis: Old and Novel Tools to Divert Their Pro-Tumor Activities into Potent Anti-Tumor Effects, Cancers (2019). [CrossRef]

- M. Balsamo, C. Manzini, Hypoxia downregulates the expression of activating receptors involved in NK- cell-mediated target cell killing without affecting ADCC, Eur J Immunol (2013). [CrossRef]

- F. Marcon, J. Zuo, H. Pearce, NK cells in pancreatic cancer demonstrate impaired cytotoxicity and a regulatory IL-10 phenotype, Oncoimmunology (2020). [CrossRef]

- T. L. Frankel, W. Burns, J. Riley, Identification and characterization of a tumor infiltrating CD56(+)/CD16 (-) NK cell subset with specificity for pancreatic and prostate cancer cell lines, Cancer Immunol Immunother (2010). [CrossRef]

- C. Bazzichetto, F. Conciatori, C. Luchini, From Genetic Alterations to Tumor Microenvironment: The Ariadne’s String in Pancreatic Cancer, Cells (2020). [CrossRef]

- E. L. Briercheck, R. Trotta, L. Chen, PTEN Is a Negative Regulator of NK Cell Cytolytic Function, J Immunol Ref [Internet] (2015). [CrossRef]

- S. Swaminathan, A. S. Hansen, L. D. Heftdal, MYC functions as a switch for natural killer cell- mediated immune surveillance of lymphoid malignancies, Nat Commun (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y. P. Peng, C. H. Xi, Y. Zhu, Altered expression of CD226 and CD96 on natural killer cells in patients with pancreatic cancer, Oncotarget (2016). [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, Z. Zhang, N. Zhang, Subcellular NAMPT-mediated NAD(+) sal- vage pathways and their roles in bioenergetics and neuronal protection after ischemic injury, J Neurochem (2019). [CrossRef]

- M. L. Stone, K. B. Chiappinelli, H. Li, Epigenetic therapy activates type I interferon signaling in murine ovarian cancer to reduce immunosuppression and tumor burden, Proc Natl Acad Sci (2017). [CrossRef]

- K. Duan, G. H. Jang, R. C. Grant, The value of GATA6 immunohistochemistry and computer-assisted diagnosis to predict clinical outcome in advanced pancreatic cancer, Scientific reports (2021). [CrossRef]

- Y. Peng, W. Gong, GATA6 impairs pancreatic cancer cells stemness by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, Research Square (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Shi, Y. Tsang, Y. Yang, Identification of ONECUT3 as a stemness-related transcription factor regulating NK cell-mediated immune evasion in pancreatic cancer, Sci Rep (2023). [CrossRef]

- Q. Yu, R. C. Newsome, M. Beveridge, Intestinal microbiota modulates pancreatic carcinogenesis through intratumoral natural killer cells, Gut Microbes (2022). [CrossRef]

- D. E. Biancur, A. C. Kimmelman, The plasticity of pancreatic cancer metabolism in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance, Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Bioenerg (2018). [CrossRef]

- J. V. Audenaerde, D. Waele, J. Smits, Elj, Interleukin-15 stimulates natural killer cell-mediated killing of both human pancreatic cancer and stellate cells, Oncotarget (2017). [CrossRef]

- I. Novak, H. Yu, L. Magni, Purinergic Signaling in Pancreas-From Physiology to Therapeutic Strategies in Pancreatic Cancer, Int J Mol Sci (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. Giannuzzo, M. Saccomano, J. Napp, Targeting of the P2X7 receptor in pancreatic cancer and stellate cells, Int J Cancer (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. Chronopoulos, B. Robinson, M. Sarper, ATRA mechanically reprograms pancreatic stellate cells to suppress matrix remodeling and inhibit cancer cell invasion, Nat Commun (2016). [CrossRef]

- Dickson, CD11b agonism overcomes PDAC immunotherapy resistance, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hep- atol (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Zaghdoudi, E. Decaup, I. Belhabib, FAK activity in cancer-associated fibroblasts is a prognostic marker and a druggable key metastatic player in pancreatic cancer, EMBO Mol Med (2020). [CrossRef]

- G. Moncayo, D. Lin, M. T. Mccarthy (2016). [link]. [CrossRef]

- C. Duault, A. Kumar, A. T. Khani, Activated natural killer cells predict poor clinical prognosis in high-risk B-and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Blood (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. F. D. Andrade, E. Tay, R. Pan, Antibody-mediated inhibition of MICA and MICB shedding promotes NK cell-driven tumor immunity, Science (2018). [CrossRef]

- S. A. Lim, J. Kim, S. Jeon (2019). [link]. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Herremans, D. D. Szymkiewicz, A. N. Riner, The interleukin-1 axis and the tumor immune microenvironment in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Neoplasia 28 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. M. Hertzer, G. W. Donald, O. J. Hines, CXCR2: a target for pancreatic cancer treatment, Expert Opin Ther Targets (2013). [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, R. Yan, J. Li, Pancreatic cancer cells assemble a CXCL12-keratin 19 coating to resist immunotherapy, bioRxiv (2022). [CrossRef]

- D. Han, K. Wang, T. Zhang, Natural killer cell-derived exosome- entrapped paclitaxel can enhance its antitumor effect, Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (2020). [CrossRef]

- N. Sato, T. Ohta, H. Kitagawa, FR901228, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest and subsequent apoptosis in refractory human pancreatic cancer cells, Int J Oncol (2004). [CrossRef]

- A. P. Cribbs, P. Filippakopoulos, M. Philpott, Dissecting the Role of BET Bromodomain Proteins BRD2 and BRD4 in Human NK Cell Function, Frontiers in Immunology (2021). [CrossRef]

- K. Hirose, Y. Omori, R. Higuchi, Clinicopathological relevance of SMAD4 and RUNX3 in patients with resected pancreatic cancer, Pancreas (2024). [CrossRef]

- M. Horvath, STAT proteins and transcriptional responses to extracellular signals, Trends Biochem Sci (2000) 1624–1632. [CrossRef]

- D. Bock, C. E. Demeyer, S. Degryse, S, HOXA9 Cooperates with Activated JAK/STAT Signaling to Drive Leukemia Development, Cancer Discov (2018). [CrossRef]

- A. S. Hemida, et al., HOXA9 and CD163 potentiate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression., Diagnostic pathology 19 (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Ling, X. Dong, L. Wang, et al., MiR-27a-regulated FOXO1 promotes pancreatic ductal adenocar- cinoma cell progression by enhancing Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity. Am J Transl Res. 15 (2019).

- M. Geindreau, F. Ghiringhelli, M. Bruchard, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, a Key Modulator of the Anti-Tumor Immune Response, International Journal of Molecular Sciences (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Ha, V. Kim, Regulation of microRNA biogenesis, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2014). [CrossRef]

- H. Kaur, J. G. Bruno, A. Kumar, Aptamers in the therapeutics and diag- nostics pipelines, Thera- nostics 8 (2018) 4016–4048. [CrossRef]

- M. Jones, A. Lal, MicroRNAs, wild-type and mutant p53: more questions than answers, RNA Biol 9 (6) (2012) 781–791. [CrossRef]

- B. Baradaran, R. Shahbazi, M. Khordadmehr, Dysregulation of key microRNAs in pancreatic cancer development, Biomed Pharmacother (2019). [CrossRef]

- Y. P. Peng, J. J. Zhang, W. B. Liang, Elevation of MMP-9 and IDO induced by pancreatic cancer cells mediates natural killer cell dysfunction, BMC cancer (2014). [CrossRef]

- C. Canto, R. H. Houtkooper, E. Pirinen, The NAD(+) precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity, Cell Metab (2012). [CrossRef]

- S. R. Niavarani, C. Lawson, O. Bakos, Lipid accumulation impairs natural killer cell cytotoxicity and tumor control in the postoperative period, BMC Cancer (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Nadella, J. Burks, A. Al-Sabban, Dietary fat stimulates pancreatic cancer growth and promotes fi- brosis of the tumor microenvironment through the cholecystokinin receptor, Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol (2018). [CrossRef]

- J. Spielmann, W. Naujoks, M. Emde (2020). [link]. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, J. K. Colby, X. Zuo, The Role of PPAR-delta in Metabolism, Inflammation, and Cancer: Many Characters of a Critical Transcription Factor, Int J Mol Sci (2018). [CrossRef]

- X. Michelet, L. Dyck, A. Hogan, Metabolic reprogramming of natural killer cells in obesity limits antitumor responses, Nat Immunol (2018). [CrossRef]

- A. Butera, M. Roy, C. Zampieri, p53-driven lipidome influences non-cell- autonomous lysophospho- lipids in pancreatic cancer, Biol Direct (2022). [CrossRef]

- X. Lin, M. Huang, F. Xie, Gemcitabine inhibits immune escape of pancreatic cancer by down regulating the soluble ULBP2 protein, Oncotarget 7 (43) (2016) 70092–70099. [CrossRef]

- F. L, Q. Q, W. P, et al., Serum levels of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 are indicators of prognosis in pancreatic cancer., J Int Med Res (2018). [CrossRef]

- A. M. Chambers, S. Matosevic, Immunometabolic Dysfunction of Natural Killer Cells Mediated by the Hypoxia-CD73 Axis in Solid Tumors, Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Feske, ORAI1 and STIM1 deficiency in humans and mice: roles of store- operated Ca2+ entry in the immune system and beyond (2009). [CrossRef]

- L. Magni, R. Bouazzi, The P2X7 Receptor Stimulates IL-6 Release from Pancreatic Stellate Cells and Tocilizumab Prevents Activation of STAT3 in Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Cell (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Baroja-Mazo, A. P. ´ ın French, F. Lucas-Ruiz, P2X7 receptor activation impairs antitumor activity of natural killer cells, Br J Pharmacol (2023). [CrossRef]

- H. Huang, R. A. Svoboda, A. J. Lazenby, Up-regulation of N-cadherin by Collagen I-activated Dis- coidin Domain Receptor 1 in Pancreatic Cancer Requires the Adaptor Molecule Shc1, J Biol Chem (2016). [CrossRef]

- J. Xiong, L. Yan, C. Zou, Integrins regulate stemness in solid tumors: an emerging therapeutic target, J Hematol Oncol (2021). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Desgrosellier, L. A. Barnes, D. J. Shields, An integrin αvβ3-c-Src oncogenic unit promotes anchorage- independence and tumor progression, Nat Med (2009). [CrossRef]

- A. J. ska Typu´ c, M. Matejczyk, S. Rosochacki, Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), the main extra- cellular matrix (ECM) enzymes in collagen degradation as a target for anticancer drugs, J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem (2016). [CrossRef]

- M. Kaasinen, J. H. om, H. Mustonen, Matrix Metalloproteinase 8 Expression in a Tumor Predicts a Favorable Prognosis in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Int J Mol Sci (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. S. Jeng, C. F. Chang, S. S. Lin, Sonic Hedgehog Signaling in Organogenesis, Tumors, and Tumor Microenvironments, Int J Mol Sci (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. D. Theocharis, M. E. Tsara, N. Papageorgacopoulou, Pancreatic carcinoma is characterized by elevated content of hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfate with altered disaccharide composition, Biochim Biophys Acta (2000). [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, D. Wang, Y. Dai, Positive Crosstalk Between Hedgehog and NF-kB Pathways Is Dependent on KRAS Mutation in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Front Oncol (2021). [CrossRef]

- W. Jing, D. Mcallister, E. P. Vonderhaar, STING agonist inflames the pancreatic cancer immune microenvironment and reduces tumor burden in mouse models, J Immunother Cancer (2019). [CrossRef]

- D. R. Principe, K. E. Timbers, L. G. Atia, TGFβ Signaling in the Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment, Cancers (Basel) (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Jewett, J. Kos, Y. Fong, NK Cells Shape Pancreatic and Oral Tumor Microenvironments; Role in Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Metastasis, Semin Cancer Biol (2018). [CrossRef]

- H. Song, H. Liu, X. Wang (2024). [link]. [CrossRef]

- Skorupan, M. P. Dominguez, S. L. Ricci, Clinical Strategies Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Cancers (2022). [CrossRef]

- P. Sancho, E. Burgos-Ramos, A. Tavera, MYC/PGC-1α Balance Determines the Metabolic Phenotype and Plasticity of Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells, Cell Metab (2015). [CrossRef]

- D. W. Dawson, M. E. Fernandez-Zapico, Gemcitabine Activates Natural Killer Cells to Attenuate Pancreatic Cancer Recurrence, Gastroenterology (2016). [CrossRef]

- R. L. Porter, N. Magnus, V. Thapar, Epithelial to mesenchymal plasticity and differential response to therapies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (2019). [CrossRef]

- F. Bianchi, M. Sommariva, V. L. Noci, Aerosol 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 supplementation: A strategy to boost anti-tumor innate immune activity, PLoS One (2021). [CrossRef]

- R. Duan, W. Du, W. Guo, EZH2: a novel target for cancer treatment, J Hematol Oncol (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Bugide, Epigenetic Mechanisms Dictating Eradication of Cancer by Natural Killer Cells, Trends in cancer (2018). [CrossRef]

- M. Edderkaoui, C. Chheda, B. Soufi, An Inhibitor of GSK3B and HDACs Kills Pancreatic Cancer Cells and Slows Pancreatic Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Mice, Gastroenterology (2018). [CrossRef]

- M. Parisotto, N. Vuong-Robillard, P. Kalegari, The NAMPT Inhibitor FK866 Increases Metformin Sensitivity in Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Cancers (2022). [CrossRef]

- X. Guo, S. Tan, T. Wang, NAD+ salvage governs mitochondrial metabolism, invigorating natural killer cell antitumor immunity, Hepatology (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Crist, B. Yaniv, S. Palackdharry, Metformin increases natural killer cell functions in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma through CXCL1 inhibition, J Immunother Cancer (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Sheinin, The role of the p40 family in pancreatic cancer, Cancer Res 3694 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. M. Sullivan, X. Jiang, P. Guha, Blockade of interleukin 10 potenti- ates antitumor immune function in human colorectal cancer liver metastases, Gut (2023). [CrossRef]

- A. Steins, M. F. Bijlsma, High-grade mesenchymal pancreatic ductal adeno- carcinoma drives stromal deactivation through CSF-1, EMBO Reports (2020). [CrossRef]

- M, Remodeling tumor immune microenvironment via targeted block- ade of PI3K-γ and CSF-1/CSF- 1R pathways in tumor associated macrophages for pancreatic cancer therapy, J Control Release (2020). [CrossRef]

- I. Mattiola, Priming of human resting NK cells by autologous m1 macrophages via the engagement of IL-1β, IFN-β, and IL-15 pathways, J Immunol (2015). [CrossRef]

- E. L. Mcmichael, A. C. Jaime-Ramirez, K. D. Guenterberg, IL-21 enhances natural killer cell response to cetuximab-coated pancreatic tumor cells, Clin Cancer Res (2017). [CrossRef]

- K. C. Lam, Microbiota triggers STING-type I IFN-dependent monocyte reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment, Cell (2021). [CrossRef]

- G. Biffi, T. E. Oni, B. Spielman, IL1-Induced JAK/STAT Signaling Is Antagonized by TGFβ to Shape CAF Heterogeneity in the Pancreatic Ductal adenocarcinoma, Cancer Discov (2019). [CrossRef]

- M. Piper, B. V. Court, A. Muller, Targeting Treg-Expressed STAT3 Enhances NK-Mediated Surveil- lance of Metastasis and Improves Therapeutic Response in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Clin Cancer Res (2022). [CrossRef]

- F. Xu, A. Sunderland, Y. Zhou, Blockade of CD112R and TIGIT signaling sensitizes human natural killer cell functions, Cancer Immunol Immunother (2017). [CrossRef]

- T. Lambin, C. Lafon, R. A. Drainville, Locoregional therapies and their effects on the tumoral microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, World J Gastroenterol (2022). [CrossRef]

- V. E. Lander, J. I. Belle, N. L. Kingston, Stromal Reprogramming by FAK Inhibition Overcomes Radiation Resistance to Allow for Immune Priming and Response to Checkpoint Blockade, Cancer Discov (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Jiang, S. Hegde, B. L. Knolhoff, Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy, Nat Med (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. A. Mohamed, A. Thomsen, M. Follo, FAK inhibition radiosensitizes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells in vitro, Strahlenther Onkol (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. J. P. on, D. M. Maurer, M. H. Hara, Sotigalimab and/or nivolumab with chemotherapy in first- line metastatic pancreatic cancer: Clinical and immunologic analyses from the randomized phase 2 PRINCE trial, Nat Med (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. M. Zeidan, R. S. Komrokji, A. M. Brunner, TIM-3 pathway dysregulation and targeting in cancer, Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, Y. Huang, L. Tan, Increased Tim-3 expression in peripheral NK cells predicts a poorer prognosis and Tim-3 blockade improves NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in human lung adenocarcinoma, Int Immunopharmacol (2015). [CrossRef]

- M. Alvarez, F. Simonetta, J. Baker, Indirect Impact of PD-1/PD-L1 Block- ade on a Murine Model of NK Cell Exhaustion, Front Immunol (2020). [CrossRef]

- L. Villanueva, Z. Lwin, D. Graham, Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for patients with previously treated biliary tract cancers in the multicohort phase II LEAP-005 study, Journal of Clinical Oncology (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Chen, S. Yang, L. Fan, Combined Antiangiogenic Therapy and Immunotherapy Is Effective for Pancreatic Cancer with Mismatch Repair Proficiency but High Tumor Mutation Burden: A Case Report, Pancreas (2019). [CrossRef]

- Q. Xia, J. Jia, C. Hu, Tumor-associated macrophages promote PD-L1 expression in tumor cells by regulating PKM2 nuclear translocation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Oncogene (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. T. Saung, S. Muth, D. Ding, Targeting myeloid-inflamed tumor with anti-CSF-1R antibody ex- pands CD137+ effector T cells in the murine model of pancreatic cancer, J ImmunoTherapy Cancer (2018). [CrossRef]

- E. Yang, B. K. Singh, Diacylglycerol Kinase ζ Is a Target To Enhance NK Cell Function, J Immunol (2016). [CrossRef]

- G. Levkowitz, H. Waterman, S. A. Ettenberg, Ubiquitin ligase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation underlie suppression of growth factor signaling by c- Cbl/Sli-1, Mol Cell (1999). [CrossRef]

- H. S. Kim, A. Das, C. C. Gross, Synergistic Signals for Natural Cytotoxi- city Are Required to Overcome Inhibition by c-Cbl Ubiquitin Ligase, Immunity (2010). [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, X. Yu, Y. Yuan, CD73, a Promising Therapeutic Target of Diclofenac, Promotes Metastasis of Pancreatic Cancer through a Nucleotidase Independent Mechanism, Adv Sci (2022). [CrossRef]

- T. Miyashita, K. Miki, T. Kamigaki, Low-dose gemcitabine induces major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain A/B expression and enhances an antitumor innate immune response in pancreatic cancer, Clin Exp Med (2017). [CrossRef]

- P. K. B. c, T. L. Rovivs, G. Cinamon, Targeting PVR (CD155) and its receptors in anti-tumor therapy, Cell Mol Immunol (2019). [CrossRef]

- N. Hussain, D. Das, A. Pramanik, Targeting the complement system in pancreatic cancer drug resis- tance: a novel therapeutic approach, Cancer Drug Resist (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Alhamhoom, A. Sobeai, H. M. Alsanea, Aptamer-based therapy for targeting key mediators of cancer metastasis (Review), Int J Oncol (2022). [CrossRef]

- L. Chiossone, Natural killer cells and other innate lymphoid cells in cancer, Nat Rev Immunol (2018). [CrossRef]

- I. Masuyama, T. Murakami, Ex vivo expansion of natural killer cells from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells costimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD52 monoclonal antibodies, Cytotherapy (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. Kumar, A. T. Khani, S. Swaminathan. [link]. [CrossRef]

- C, Y. N. Li, H, Robo1-specific chimeric antigen receptor natural killer cell therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis, J Cancer Res Ther (2020). [CrossRef]