1.Introduction to Organic Farming Economics

The discussion of the organic farming economics has benefited greatly by the work of this paper. Traditionally input-intensive, agrochemical-based agriculture has improved yields and addressed issues related to global food security during the 1960s green revolution. But the environment and public health have been impacted by the persistent, unbalanced, and frequently excessive use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers [

1]. Thus, over time, there has been a rise in demand for organic and non-chemical agricultural products. Consumer demand for natural products has increased at a rate of 16% annually during the last ten years [

2]. Additionally, growing demand for foods that are not genetically modified (GMO) and the rising prices of chemical inputs like pesticides and fertilisers are pushing farmers towards organic and ecologically friendly farming practices [

3]. According to the FAO, organic farming relies less on external agricultural inputs like synthetic pesticides and chemical fertilisers and a greater emphasis on ecosystem management [

4]. However, at the policy level, there have been questions raised over how well organic farming can feed the world's population. These issues are particularly pertinent in densely populated regions such as South Asia, where organic farming affects yield, profitable farming, and income per unit of agricultural output. The fear has increased as a result of recent limitations on Sri Lanka's food security brought on by the nation's switch to organic farming. Multiple investigations have shown that organic farming significantly lowers crop yields, while other studies show that crop production variability has increased [

5]. Studies have also shown that the benefits of organic farming, such as higher soil organic carbon content, organic matter, and biodiversity at the farm level, more than make up for yield losses by improving sustainability. As a result, perspectives regarding the advantages and disadvantages of organic agriculture vary greatly [

6].

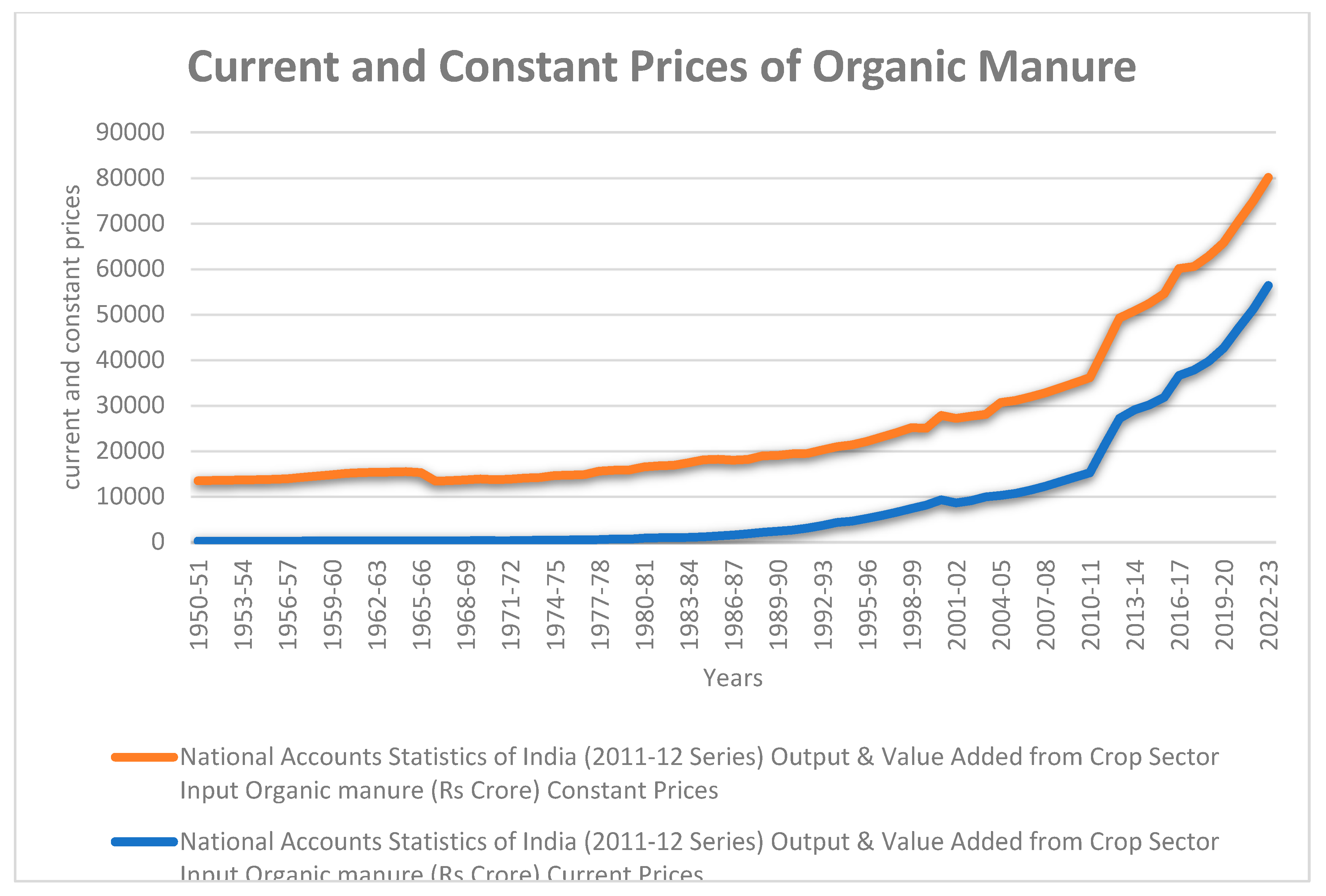

Table 1 shows the production of organic manure by India.

Chart 1.

Data on India's "Output & Value Added from the Crop Sector" for organic manure inputs, especially, from 1950–51 to 2022–23 is shown. In the framework of India's National Accounts Statistics, it provides figures at both current and constant prices, showing the evolution of spending on organic manure over time (based on the 2011-12 series).

Chart 1.

Data on India's "Output & Value Added from the Crop Sector" for organic manure inputs, especially, from 1950–51 to 2022–23 is shown. In the framework of India's National Accounts Statistics, it provides figures at both current and constant prices, showing the evolution of spending on organic manure over time (based on the 2011-12 series).

1.2. Consumption and Export Trends of Organic Food in India

Many people have the false impression that organic food is merely a flimsy idea intended mainly for wealthy nations. Furthermore, a large portion of organic food is produced just for export, despite India's best efforts to emphasise this. It's not true, though. Many people seek out organic food for local consumption, despite the fact that 50% of India's organic food output is intended for export. Children's health was the primary deterrent to the general public's shift towards organic food consumption. Food that is organic is also more expensive in India—by more than 25%—than food that is conventional. However, because organic food is thought to have additional health advantages and has been deemed totally safe for household use, many parents are now willing to pay this greater price. The fact that there are an increasing number of organic food stores in India indicates that the country's consumption of organic food is rising. These days, a lot of restaurants and retail food stores have to serve organic food. India's consumption pattern of organic food differs significantly from that of Western nations. However, Indian consumers of organic food need to be educated. Many consumers are unaware of the distinction between natural and organic food.

Many consumers buy products that have the tag "Natural," assuming them to be Organic.

In addition, consumers do not know about the authentication process. Since Indian domestic retail is not certified, it has many fake organic products available for sale. Due to the growing number of farmers using organic farming methods, India is exporting more organic food for consumption. India is now a major supplier of organic herbs, spices, and basmati rice, among other products. Over 53% of India's current organic food production is exported, which is significantly higher than the country's organic food exports in 2003–04, when they made up roughly 6–7% of all agricultural products produced in India [

7]. The total India total organic food items’ export 11,295 sale (Tons) including all organic food such as Rice, Wheat, Pulses, oilseeds vegetables and fruits, tea., etc.

Currently, India exports the following organic food products:

Organic Cereals- Rice, Wheat, Maize etc.

,, Pulses- Black gram, red gram

,, Fruits- Mango, Orange, Pineapple, Banana, Walnut, Cashew nut etc.

,, Oils and Oils Seeds- Soyabean, Sunflower, Mustard, Cotton seed, Castor etc.

,, Vegetables- Tomato, potato, Garli, Brinjal etc.

,, Herbs and Spices- Turmeric, Chilli, Black pepper, Clove, White pepper etc.

Others- Coffee, Tea, Sugar, Cotton etc.

1.3. Indian Rural Financial System’s Use of Organic farming

It is possible to highlight and utilise the importance of organic farming in India's rural economy in order to address the country's growing food security issue. An agricultural issue has arisen due to a significant rise in the industrialisation of rural areas.

Using naturally produced and decomposable materials for growth and supplying resistance to various crops in a direct or indirect way against various infections are two aspects of organic farming. It's not like organic farming wasn't done in the past. Since ancient times, people have always used naturally occurring materials to boost output, prevent disease, and control pests. utilising a variety of natural goods and byproducts, such as cakes, cow dungs, neem leaves, turmeric, and other materials are still used in India to keep pests away. serve as preserving agents. The late 1850s saw the introduction of artificial fertilisers in an effort to boost production. The following are the primary arguments in favour of encouraging organic farming in India's rural economy:

Organic fertilisers don't produce any hazardous substances as intermediates, making them entirely safe. In comparison to chemical fertilisers, organic fertilisers are often used in far smaller amounts. Furthermore, whereas large amounts of water are necessary for chemical fertilisers to activate their molecules, organic fertilisers do not require similar circumstances. Moreover, chemical fertilisers consistently have negative, long-lasting effects on the environment or farm products. Chemical fertilisers always have the potential to react with chemicals used to eradicate different diseases and pests, creating toxic chemical compounds as a result of the combination's cumulative effects. But when using organic fertilisers, this circumstance is avoided.

1.4. Organic and Conventional Production Systems: A Comparative Analysis

1.4.1. General Comparisons

When compared to conventional farming methods, organic farming is characterised by higher output prices, lower yields, and lower input utilisation. This necessitates using more natural pest control techniques. asserted that because of their diversity, organic farms are less susceptible to specific pests or unfavourable weather, even when they use smaller fertilisers and insecticides. Even though it can be challenging to quantify and contrast naturally produced and conventional farming practices, there are substantial environmental advantages to this production method on farms [

8]. the significance of crop rotation in organic agricultural practices. Long-term sustainability, decreased CO2 emissions, and increased efficiency are some of its benefits. Roadside stands, farmers' markets, and community-supported agriculture are a few instances of shorter food supply chains that boost farmer income [

9].

compared systems based on organic legumes, organic animal-based systems, and conventional corn-soybean crop rotation. Regular weather produced higher yields for conventional agriculture. However, organic systems performed far better during drought circumstances (around 30%). Over the course of the 10-year analysis, there was an average decrease in maize production of just 3%. Reduced labour, fertiliser, and pesticide costs, together with increased seed and equipment costs, are the main factors contributing to organic production's lower overall cost of production. Peak times for organic production are different from conventional, despite the fact that labour costs are usually higher. Consequently, this makes it possible to hire labour at a lower cost. Over a ten-year period, organic maize proved to be 25% more lucrative than conventional maize, even after accounting for the substantial price premium (up to 140%) [

10].

1.4.2. Comparisons Particular to a Product

The most popular methods used by tiny farmers contract farms producing organic coffee in tropical Africa were composting, mulching, animal waste, and organic pesticides. Farmers were encouraged to join an organic system by higher net coffee revenue, which averaged 75%. The benefits from using more organic practices (cheap and efficient farming methods) were less than this impact. Because of the increased coffee yield, this was 9% per practice. Contracting offers a price premium if quality requirements are satisfied and appears to lessen farmer uncertainty around net returns [

11]. carried out a production and establishment research to give producers a tool for financial management and decision-making. They pointed out that growing blueberries is costly, and that yield and price per pound determine profitability. The type of soil, management techniques, and cultivar/variety grown all affect an established farm's yield. Additionally, there is a lot of variances in the time it takes to attain maximum productivity; some farms may take up to seven years [

12].

1.4.3. Switching Conventional Farming to Organic Agriculture

There are several factors that come into play while switching from conventional to organic farming. As previously shown, this calls for a change in perspective and a move away from strategies and inputs (synthetic chemicals) that are currently banned in favour of a more labour-intensive paradigm. The country's legislation and the goods will determine how long the transformation takes. It is necessary to use organic farming methods throughout this period.

Indicated that small-scale farmers in underdeveloped nations would benefit more from a transition to organic produce. With improved seeds, organic fertiliser, and technological support, they may increase their harvests. Although organic farming may require more work, the cheaper input costs may make up for it. However, organic conversions are not without risks. Because of tiny along with emerging organic markets, growing crops organically entails a larger price risk; nonetheless, organic yields typically do not change more than conventional yields [

13].

Economic and agricultural data from a comparative experiment of farming systems in central India over the 2007–2010 conversion phase. The impacts of conventional, organic, and biodynamic management on a crop rotation of wheat, soybeans, and cotton were investigated. Both cotton (229%), and wheat (227%) showed a discernible production variance between standard and organic agricultural practices in the first crop cycle. That difference did, however, significantly close in the next crop cycle. Because organic farming systems had lower variable production costs (but similar yields) in cycle two, their gross margins were much greater (+25%) than those of conventional farming systems, which on average had much larger gross margins in cycle one (+29%). Compared to traditional agricultural systems, organic farming techniques need less capital. Smallholder farmers, who usually lack the funds to buy inputs and would otherwise have to apply for loans, would find this of special interest. Because of this, organic farmers may be less vulnerable to the financial hazards brought on by changes in the price of synthetic fertilisers and angioprotectin’s [

14].

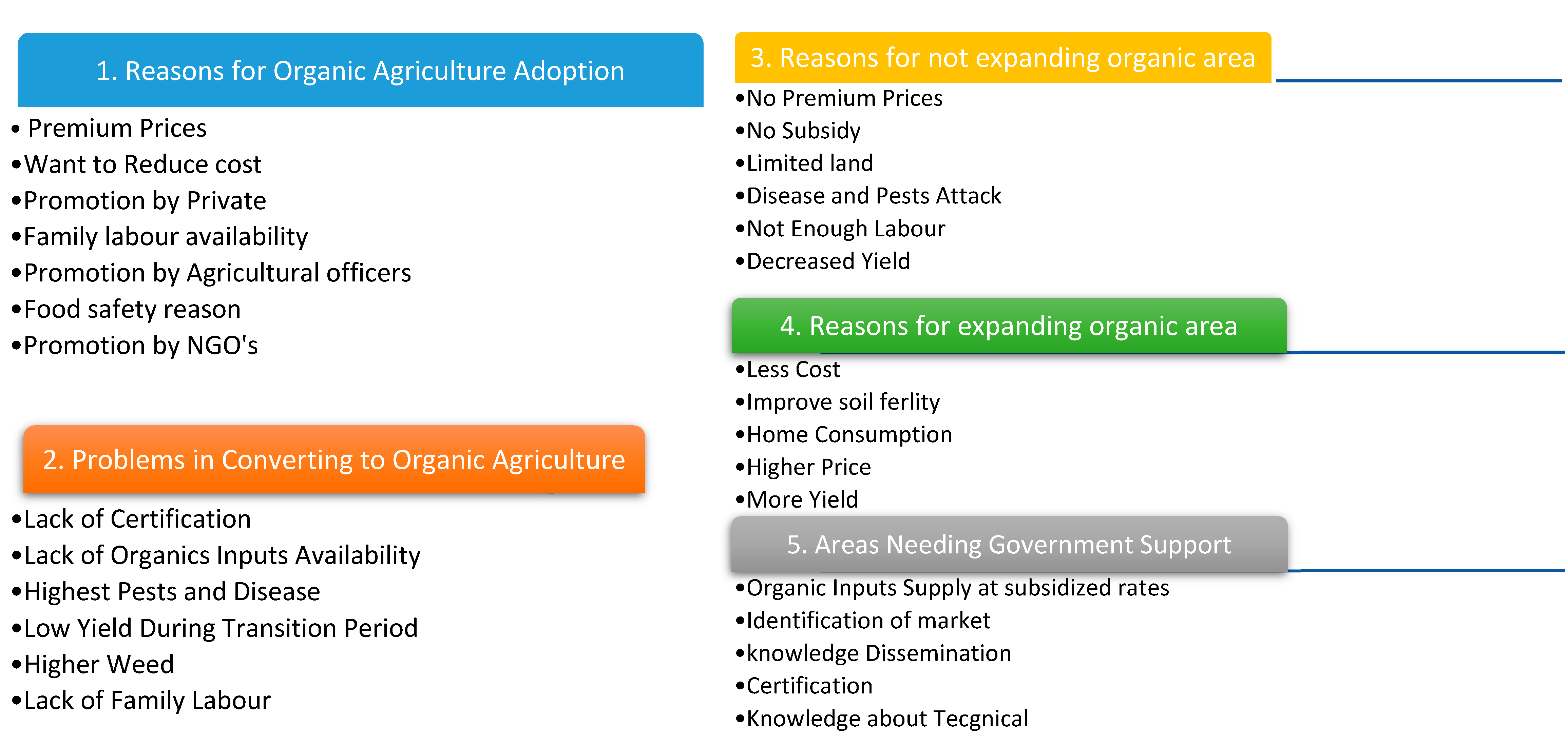

1.5. Farmers' Perceptions about Organic Agriculture

The behavioural principles established by Chetsumon and Wheeler were used in this part to evaluate farmers' attitudes regarding organic farming [

15]. There were five sections to the indicators (

Figure 1). A little over 46% of farmers claimed to have switched to organic farming for reasons related to food safety and health. Organic farming was adopted for a second reason: to lower manufacturing costs. The significance of agricultural officers' work was demonstrated by the fact that 32% of farmers stated they switched to organic farming as a result of guidance from these government officials. Because the majority of private businesses offer chemical pesticides and fertilisers, their ability to support organic farming was limited—only 12% of respondents said they would do so. The biggest obstacle to switching to organic farming, according to research, was that 57% of farmers lacked certification, which prevented them from charging a premium.

Moreover, labour (especially family labour) and organic input scarcity were major restriction, since labour-intensive organic farming requires more work than conventional farming. Farmers are reluctant to switch to organic farming even if it is less expensive. to broadly implement it because to its poor yields, increased labour and supervision needs, and absence of premium cost [

16]. For their personal needs, some farmers favour organic agriculture. requirements for consumption. In general, farmers believe that the government ought to assist in providing subsidised organic inputs and guaranteed top dollar for their product in order to encourage broader use type farming that is organic.

1.6. Market Trends in Organic Manure

India's market for organic goods is expanding quickly because to government support, growing environmental concerns, and growing health consciousness. In order to avoid synthetic chemicals, more Indian consumers are selecting organic fruits, vegetables, cereals, and spices. The Indian government has started programs such as the PKVY, which offers incentives for organic farming, to help farmers transition to organic methods. E-commerce companies and other retailers are expanding their selection of organic products to make them more accessible to customers. Notwithstanding this expansion, the organic industry still confronts obstacles like exorbitant certification costs, a weak supply chain, and a lack of knowledge among some customer segments. The expansion of India's organic agriculture is also greatly aided by export demand, especially from countries like the U.S. and Europe, which has made India a major supplier of organic produce worldwide.

In chart 1, demonstrates a consistent increase in organic manure prices in India between 1950–51 and 2022–23. Due to inflation, costs increased dramatically from ₹166.56 crore to ₹56355 crore at current pricing. actual costs increased more modestly from ₹13266.33 crore to ₹23761 crore in constant prices (2011–12 base), showing modest actual growth over time. This emphasises the effects of inflation as well as the steady rise in the cost of agricultural inputs.

Figures given from 2011-12 to 2022-23 are as per National Accounts Statistics 2024.

1.7. Demand from Consumers for Organic Products

Over the past ten years, there has been a significant surge of consumer demand towards organic products [

17]. Since organic products are made from natural components, artificial fertilisers and chemicals are presumably avoided. Therefore, to qualify as organic, a product needs to be approved by ecological accreditation, have been produced in a way that respects the land, avoids the use of chemicals, and protects its nutrients. By preventing ongoing exposure to chemical products, its consumption saves the health of farmers and laborers who produce it in addition to the consumers themselves. In addition, organic farmers work to guarantee resource sustainability as a sign of their concern for coming generations. Organic products are beneficial to both consumers and the environment. Because organic products are of superior quality, don't include any potentially dangerous ingredients, and don't contain synthetic additives, consumers see them as advantageous. By eliminating the use of harmful chemicals in the product's manufacturing, the damage to plant and animal species is reduced, and the water and soil are protected. Because they require more labor to produce, organic products create jobs. As a result, they help the environment, support ecosystem preservation, and promote more sustainable rural development.

The word "ecological" is becoming more and more common in consumers' lives, creating new demands that businesses try to meet [

18]. The behavior of those looking for alternatives to the consumption of conventional products reflects the growing concern in recent years for both personal health and the sustainability of the environment.

There is no information on the number of organic products consumed domestically. It is a fact, however, that as health consciousness and interest in organic farming grow, so does the home market's desire for organic products. Between 2022 and 2027, the food of Indian organic industry is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 25.25 percent, according to the IMARC analysis. exports of organic products throughout the previous three years [

19].

Table 2.

Showing Organic product exports by value over the previous three years.

Table 2.

Showing Organic product exports by value over the previous three years.

| Year |

Exported Qty (MT) |

Value (Crore) |

Value (USD Million) |

| 2019-20 |

638998 |

4686 |

689.1 |

| 2020-21 |

888179 |

7078.5 |

1040.96 |

| 2021-22 |

460320 |

5249.32 |

771.96 |

1.8. Government Policies and Subsidies in Organic Agriculture

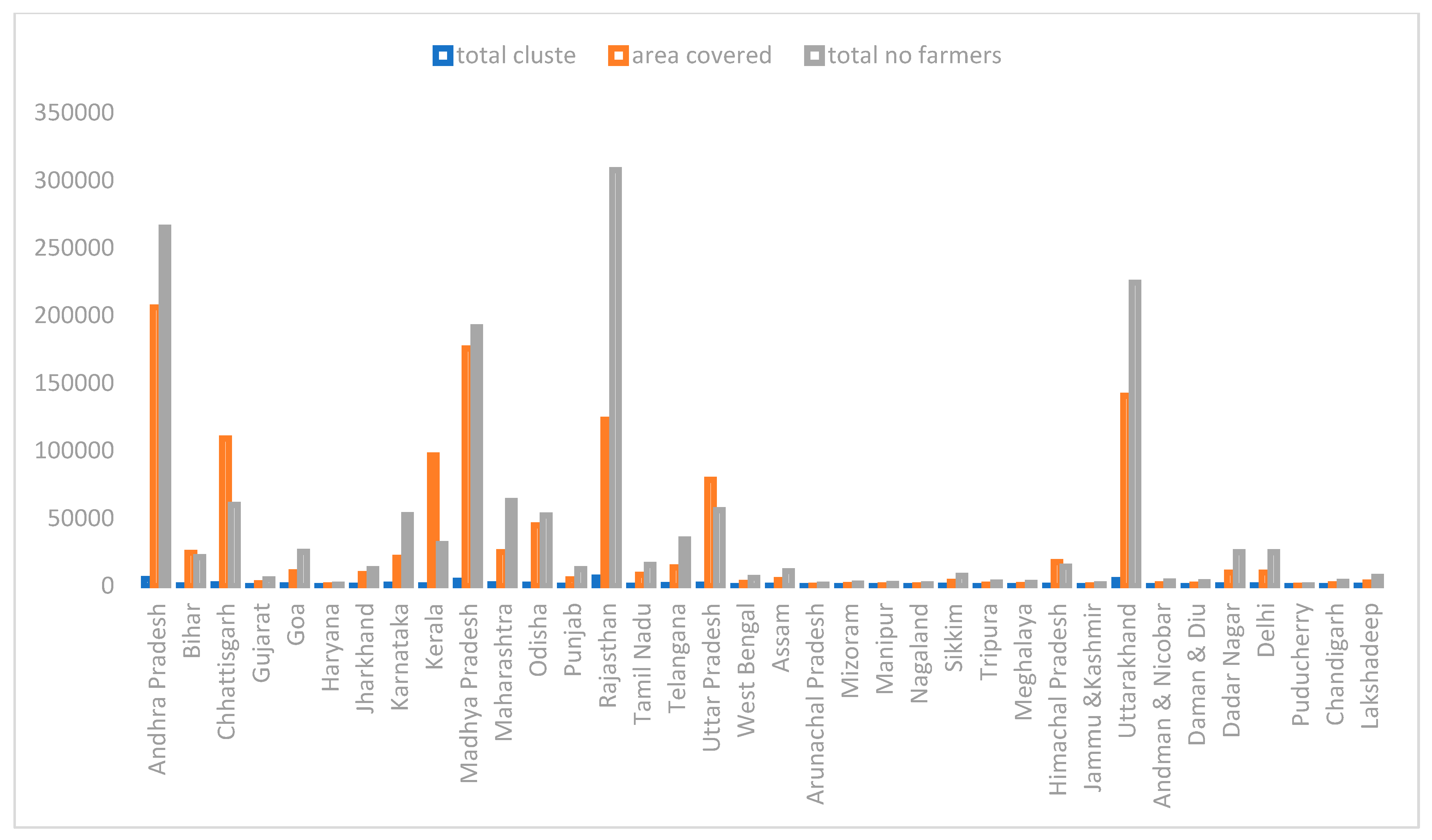

Since 2015–16, the government has promoted chemical-free organic farming through particular programs called the PKVY and MOVCDNER, in response to the growing demand for organic products. Both initiatives help organic farmers with post-harvest handling, including packaging and processing, as well as organic growing, certification, and marketing. information about the areas and farmers in different states that are involved in organic farming. As a subscheme of the PKVY, BPKP was introduced in 2020–22 to support traditional indigenous methods like Natural Farming (NF). The program encourages the recycling of biomass on farms, with a focus on biomass mulching, the use of cow dung-urine formulations, and plant-based preparations. It also emphasizes the elimination of all synthetic chemical inputs. Natural farming has so far occupied 4.09 lakh hectares of land, and a total of Rs. 4980.99 lakh has been made available in eight states across the country. Beginning with this program, the government has given individual farmers who own 8.0 hectares or more of land financial support for three years at a rate of 2700 per hectare in order to obtain certification under the PGS or NPOP through the Regional Council.

Organic farming improves crop productivity and soil fertility. Studies carried out as part of the ICAR-All India Network Programme on Organic Farming show that after five years, the yield of rabi crops stabilizes, while kharif and summer crops can provide yields equivalent to or marginally higher than those of conventional management within two to three years. "Organic inputs such as seeds, compost/vermi-compost, organic manure, bio-fertilizers, bio-pesticides, botanical extracts, etc. can be availed by farmers under the PKVY scheme at Rs 31000/ha for three years and under the MOVCDNER scheme at Rs 32500/ha for three years. Furthermore, organic produce marketing, value addition, certification, training, and the establishment of Farmers Producers Organizations (FPOs) can all receive assistance. For three years, BPKP offers financial support of Rs. 12200 per hectare for cluster formation, capacity building, certification, residue analysis, and routine monitoring by trained personnel [

20].

Chart 2.

Farmers, states, and areas covered by the Parampragat Krishi Vikas Yojana program since 2015–16.

Chart 2.

Farmers, states, and areas covered by the Parampragat Krishi Vikas Yojana program since 2015–16.

1.9. Challenges and Barriers in Organic Farming

However, a number of obstacles still exist even though organic farming is widely accepted in India. The numerous important issues brought to light in recent research are reviewed in this section.

1.9.1. Absence of Import and Domestic Market Policies

With a primary concentration and export-oriented production, India's current organic farming policy does not pay much consideration to the establishment of organic farming regulations for the local market and imports. In light of this, the lack of regulations governing organic production labelling standards and logos increases the likelihood that farmers and consumers will not be able to distinguish between organic and conventional products. As a result, since consumers are willing to pay for organic products, fraudulent activities keep legitimate parties from benefiting [

21].

1.9.2. Reduced Crop Production

In the early stages of production, farmers that convert to organic farming usually experience reduced yields. Additionally, the sustainability of organic crops is uncertain, making them unsustainable and raising production expenses [

22].

1.9.3. Insufficient Organic Seeds to Encourage Organic Agriculture

The native cultivars are susceptible to simultaneous use of genetic and fertilizer-sensitive planting materials and seeds due to their sensitivity to chemicals and fertilisers. This causes marked inequalities in access to premium organic seeds, scaring off farmers from adopting organic practices.

Issues of cooperation from all parties involved in India's sustainable agricultural sector need to be addressed. Sponsorship of research and improvement of technology could help the farmer adjust to consequences pertaining to climate change, along with the creations of awareness of organic farming benefits and laws for the protection of the facilities and assistance services of organic farmers. Governments may stimulate the production and distribution of naturally grown seeds, for example, by collaborating with seed companies and offering incentives to growers who utilize those seeds. Decomposition and organic fertilizers may also enhance long-term crop yields through stimulating soil fertility and decreasing dependence regarding artificial fertilizers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, with emphasis on ecological balance, health of the soil, and less dependency on artificial chemicals, organic farming emerges as a very promising alternative to conventional farming. Organic farming gradually replaces chemical-based farming because consumers demand more secure, healthy, and environmentally friendly food products. Because organic farming eliminates the risks of food pesticide and fertilizer residues and minimizes chemical pollution from soil and water, it reaps a rich harvest for both environmental and public health. With quality, nutritional benefits, and a contribution toward sustainable agriculture, the value of organic produce is accelerating. Still, despite its advantages, India's organic farming industry has several hardships to endure. Farmers often experience lower crop yields in the first years of conversion to organic farming, a factor that may affect profitability. It also entails more labour input and, in some cases, specific know-how and technical skills, such as in crop rotation, soil management, and pest control. Certification costs are too high for most small farmers, while procedures for getting certified are often cumbersome and inefficient. Availability of organic seeds and inputs remains a challenge, making it even harder for farmers who want to desert the conventional practice. Policy support in the form of infrastructure, technical assistance, and subsidies will help in wider adoption. With programs like MOVCD and PKVY, the Indian government is attempting to encourage organic farming after realizing these difficulties. These initiatives support certification and market connections, help establish Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), and offer financial aid for organic inputs. Reducing fraudulent activity and promoting consumer trust may be achieved by extending such policies to concentrate on the home market and controlling import standards.