1. Introduction

Coagulation in newborns is a complex and dynamic process requiring the interplay of platelets, vascular endothelium, and clotting factors to achieve proper hemostasis. Any disruption in this balance can lead to thrombotic or hemorrhagic disorders. In neonates, the coagulation system is immature and undergoes significant developmental changes during the first six months of life [

1].

Catheter placement represents the most significant risk factor for neonatal thrombosis, accounting for 85–90% of thromboembolic events [

1]. Thrombosis in neonates has a profound clinical impact, occurring 40 times more frequently during the neonatal period compared to later life. Approximately 1% of neonates with vascular catheters develop thrombotic complications, of which 30% are asymptomatic [

2]. The risk of thrombosis increases with prolonged catheter duration and challenging catheter insertion. Additional risk factors, such as perinatal asphyxia, hypovolemia, sepsis, dehydration, polycythemia, and congenital heart defects, further contribute to a prothrombotic state [

3].

Early diagnosis and treatment of catheter-associated thrombosis are crucial for preventing severe complications such as pulmonary embolism, portal hypertension, infections, or even death. However, the optimal use, dosing, efficacy, and safety of thrombolytic agents in neonates remain poorly understood [

4].

The management of catheter-associated thrombotic events poses a significant challenge due to limited evidence and the absence of standardized treatment protocols, particularly given the high risk of complications. While treatment guidelines exist, they are primarily based on expert consensus and extrapolated data from adult studies, reflecting a lack of high-quality neonatal-specific research.

This paper aims to present two cases of neonatal intracardiac thrombi associated with central venous catheters, each managed with distinct therapeutic approaches tailored to specific risk factors.

2. Case Presentation

Clinical Case One

A 39-week-old neonate, born to a 30-year-old mother (G5, P3, A1) with no history of substance use. The mother’s blood type was A+, with negative VDRL and HIV test results. Prenatal care was adequate and included the use of hematinics starting in the second month of pregnancy. Gestational diabetes was diagnosed in the last month of pregnancy and managed with metformin. The neonate was delivered via cesarean section in a private hospital, with a birth weight of 4370 g and Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively.

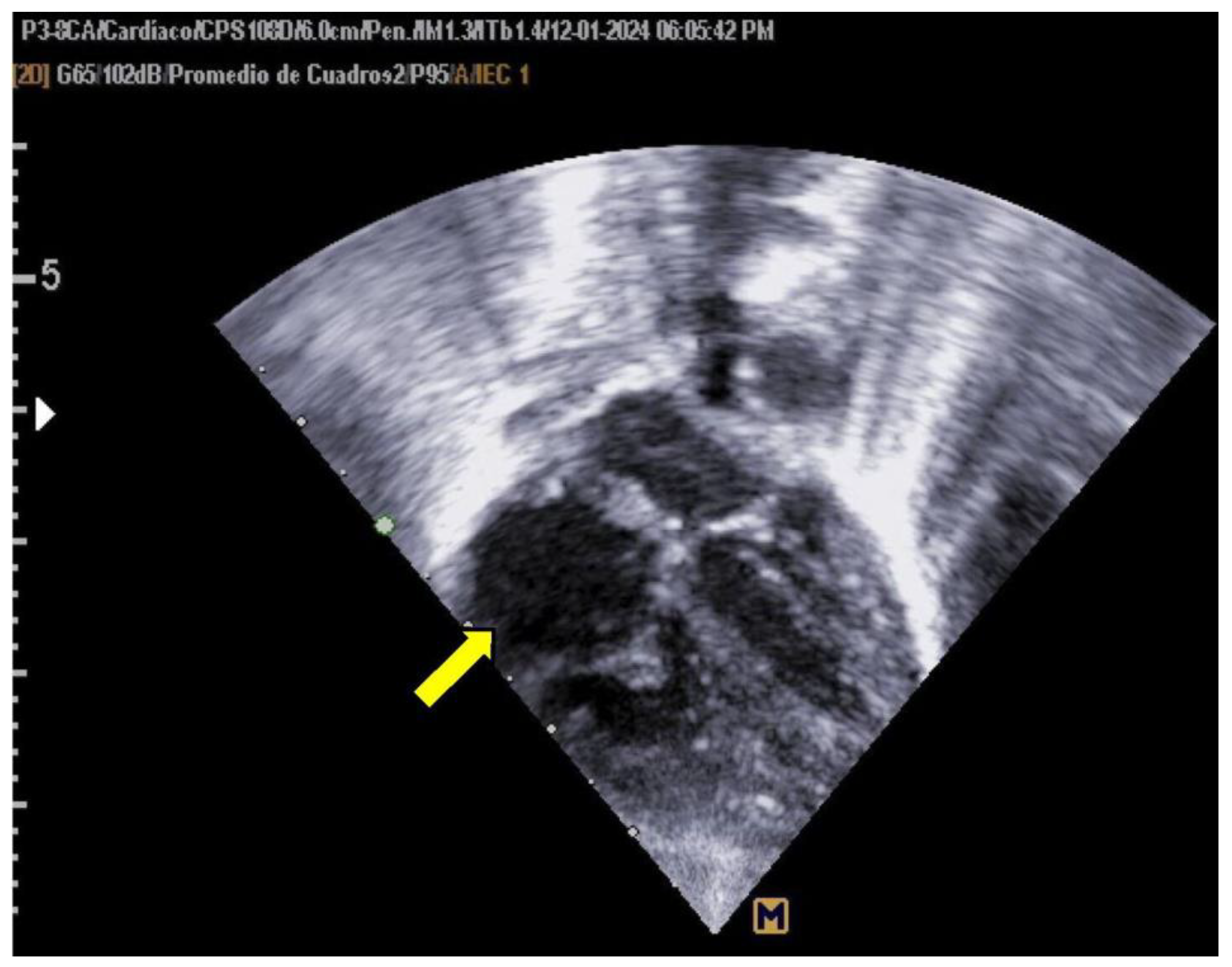

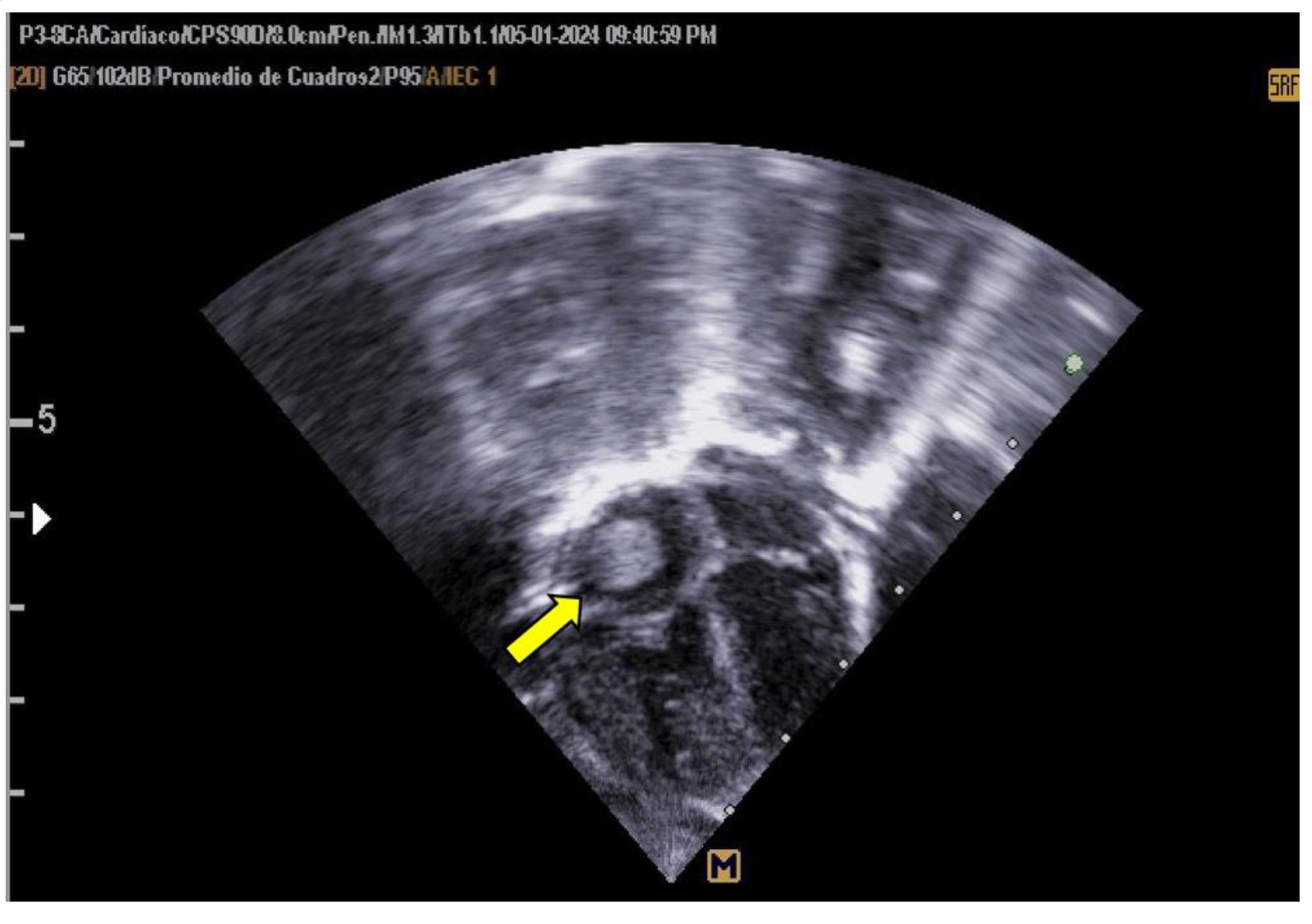

The neonate was referred to Hospital General de Cancún due to tachypnea. Oxygen therapy was initiated using a headbox, and a 5 Fr umbilical catheter was inserted without complications. A pediatric cardiology evaluation, prompted by the maternal history of gestational diabetes, revealed asymmetrical septal hypertrophy and a non-obstructive thrombus (measuring 0.94 × 0.83 cm) in the right atrium (as shown in

Figure 1).

Anticoagulation therapy was initiated with enoxaparin (1.7 mg/kg/day), and the central catheter was removed three days after starting anticoagulation. Enoxaparin was temporarily discontinued due to thrombocytopenia but was subsequently resumed, completing a total of 19 days of treatment.

During hospitalization, the thrombus did not obstruct the inferior vena cava. The neonate required supplemental oxygen for two days and was treated with antibiotics (ampicillin and amikacin). On day 5, the neonate developed septic shock, prompting an escalation to cefotaxime and later imipenem after a positive stool culture for Klebsiella. Vancomycin was added following the identification of Staphylococcus haemolyticus infection. A transfontanellar ultrasound performed initially was normal; however, a follow-up ultrasound one month later revealed findings consistent with a non-recent intraventricular hemorrhage (Papile grade II).

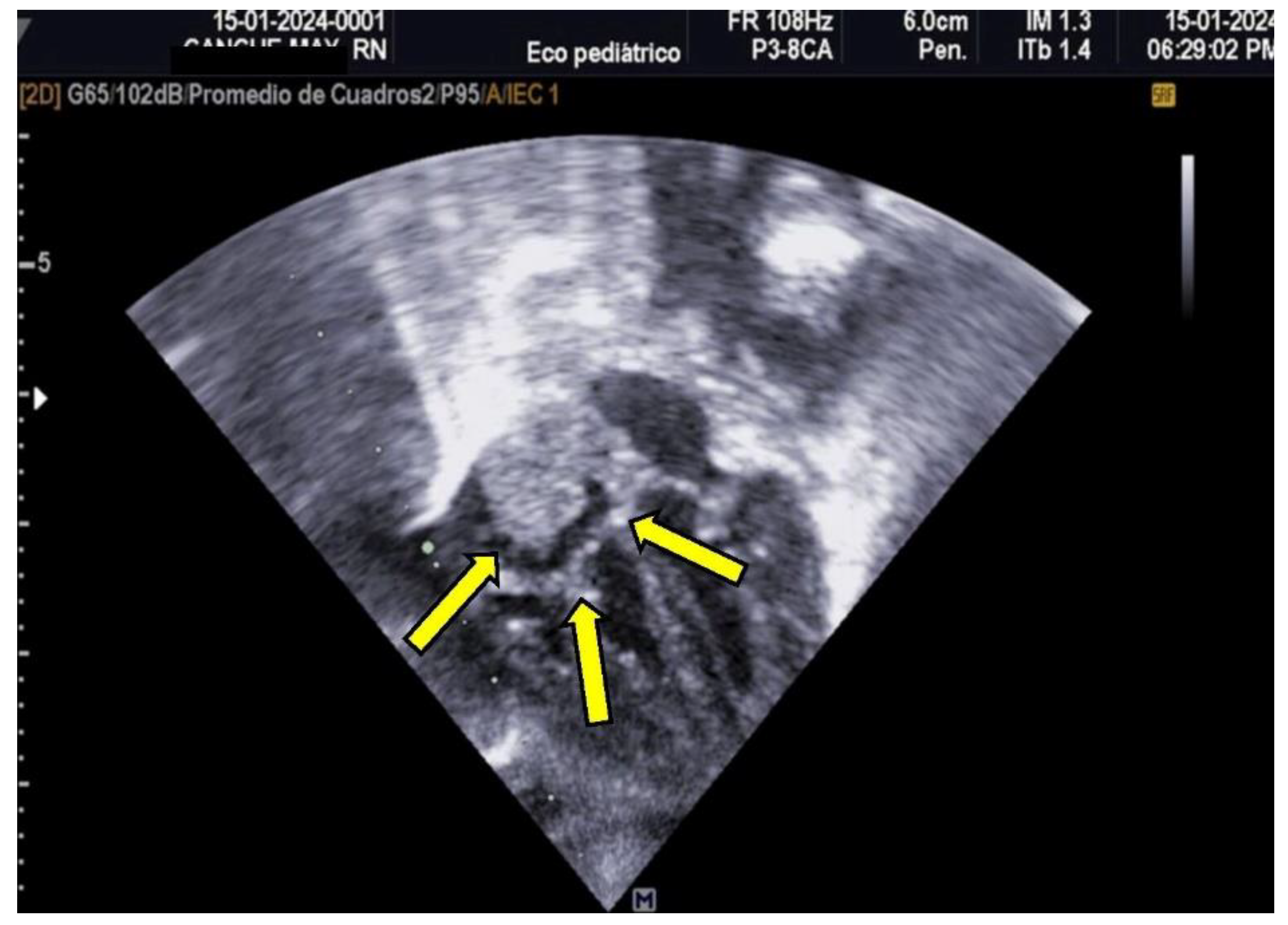

The patient was monitored weekly by a pediatric cardiologist. Despite no reduction in thrombus size during follow-up, the thrombus remained well-attached and non-pendulous, with no immediate indication for thrombolytic therapy. Due to the high risks associated with prolonged hospitalization, reinfection, and potential bleeding, the patient was discharged to avoid further complications. The family was counseled on embolization risks, and outpatient management with aspirin (AAS) was initiated. Follow-up evaluations were conducted weekly for two months and subsequently on a monthly basis. Complete thrombus resolution was observed by the sixth month, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Clinical Case Two

A 37-week-old neonate was born to a 19-year-old primigravida (G1) with no history of substance use. The mother’s blood type was O+, with negative HIV and VDRL test results. The pregnancy was uneventful, with eight prenatal visits. Gastroschisis was diagnosed at 20 weeks of gestation. Spontaneous labor occurred at 35.4 weeks, and attempts at uteroinhibition were unsuccessful. Delivery was via cesarean section with early cord clamping.

The neonate responded well to initial resuscitation, with the airway secured due to the gastroschisis, and a 3.5 Fr cannula was placed. The neonate's birth weight was 2765 g, length 45 cm, with Apgar scores of 7 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. Capurro assessment confirmed a gestational age of 37 weeks. Pediatric surgery successfully placed a silo without complications.

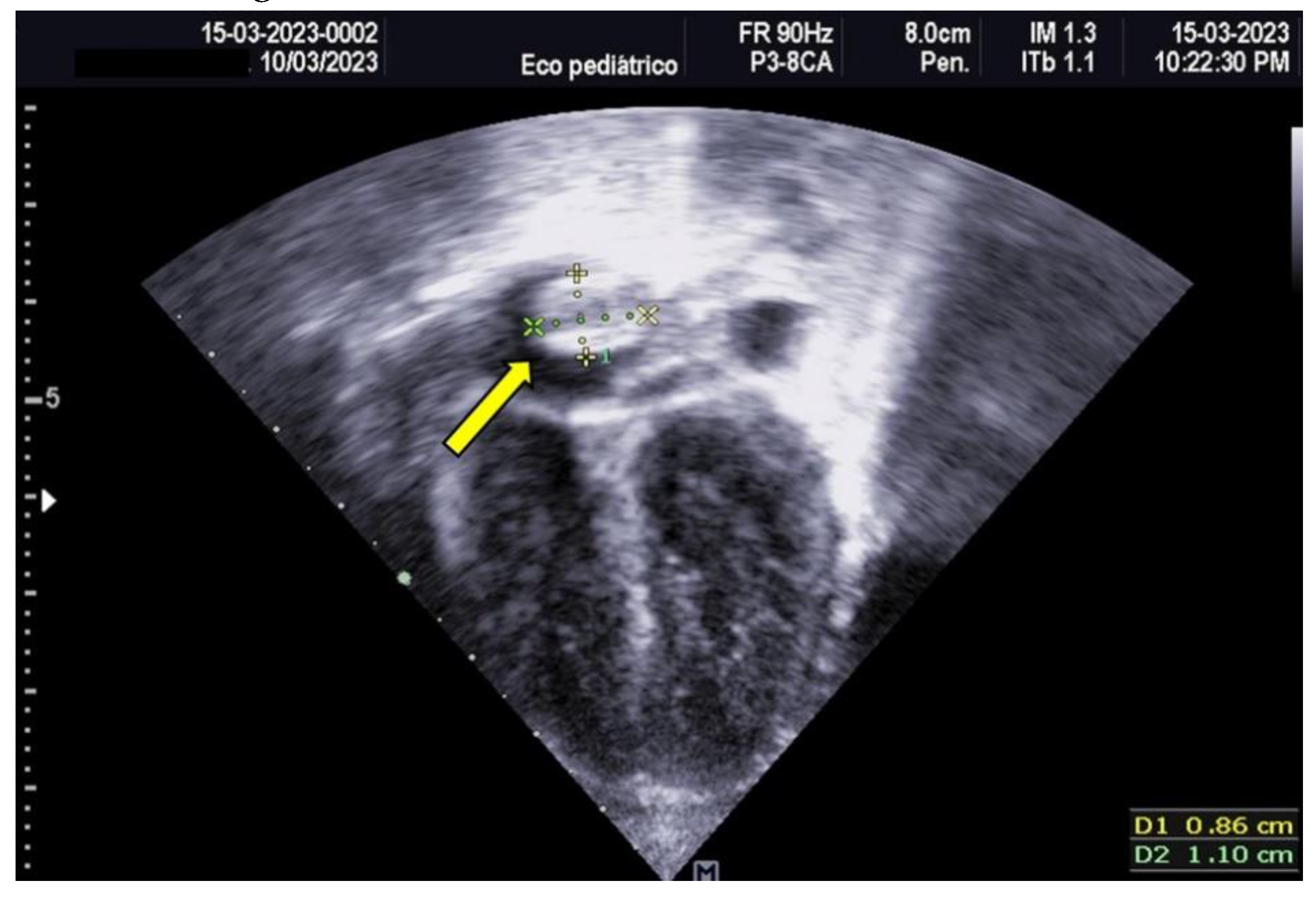

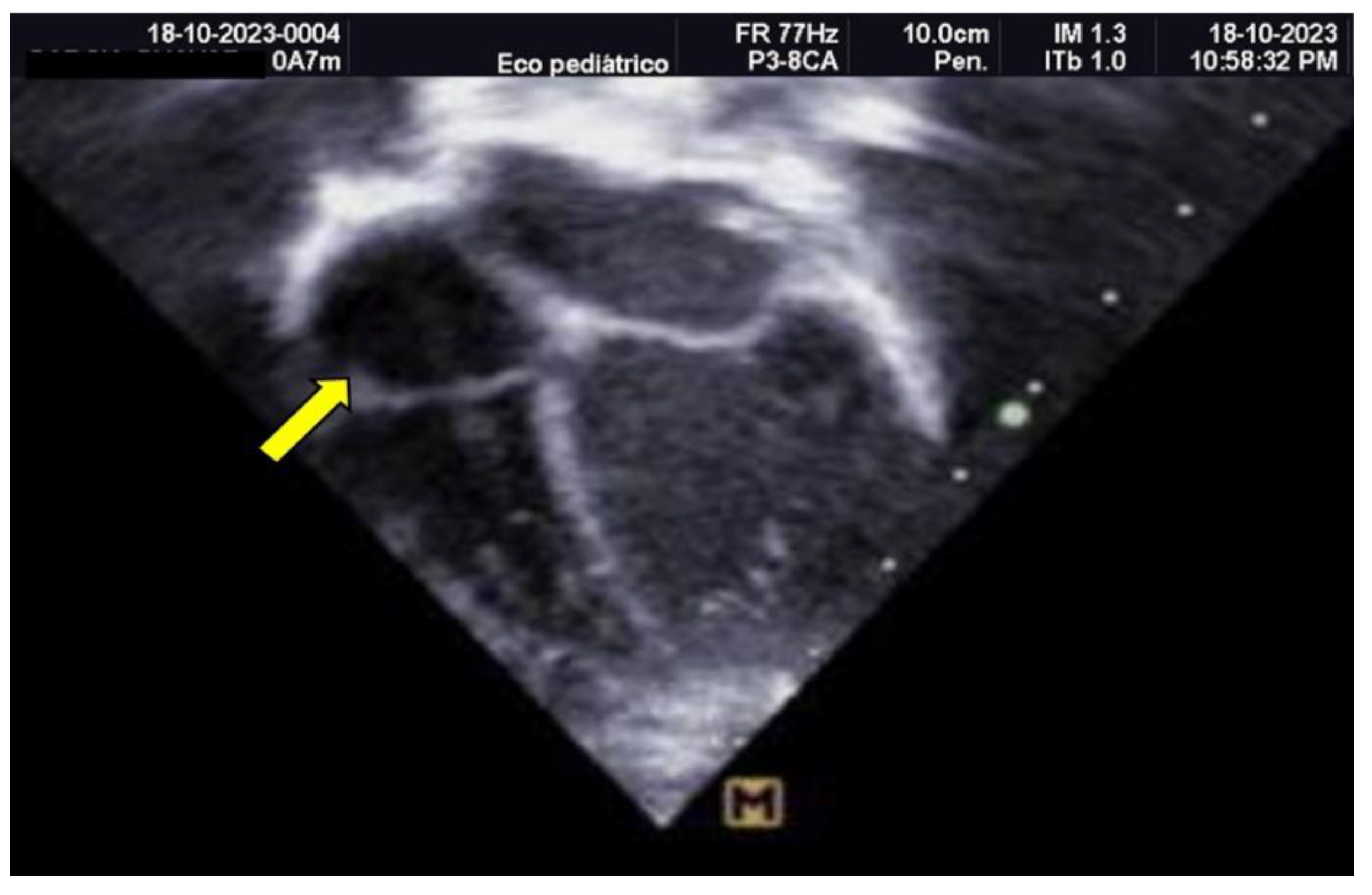

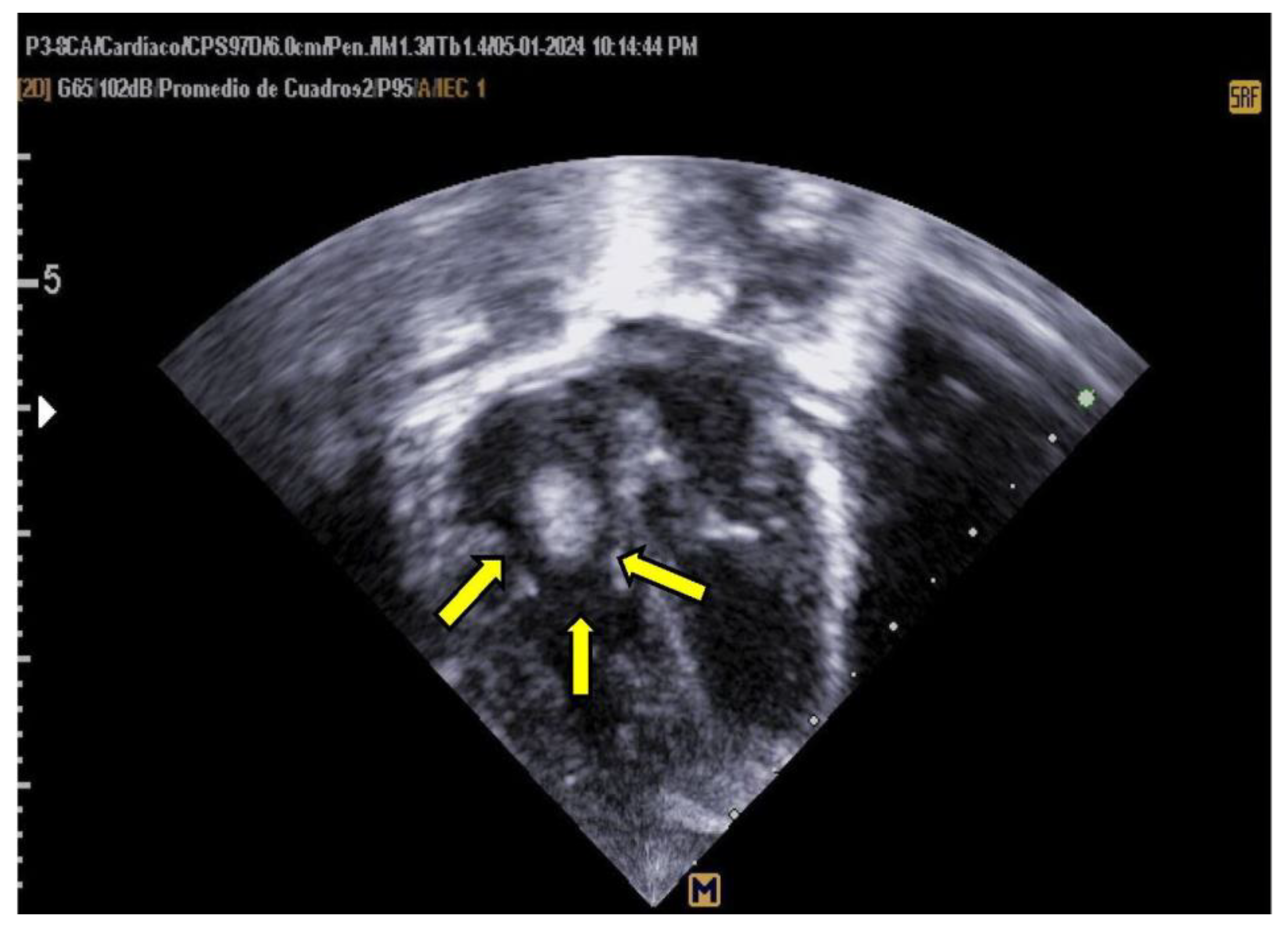

Empirical antimicrobial therapy with ampicillin and amikacin was initiated but later escalated to meropenem due to clinical signs of shock and poor response to initial treatment. Upon admission, a 4 Fr central venous catheter was placed in the left subclavian vein, with correct positioning verified by chest X-ray and adjusted by 1 cm. A pediatric cardiology consultation revealed a large thrombus measuring 1.5 × 0.7 cm in the right atrium, which was highly mobile and at risk of embolization, as shown in

Figure 3 and 4.

Due to prolonged coagulation times, alteplase was initially contraindicated. Fresh frozen plasma (10 mL/kg) was administered to improve plasminogen levels, followed by enoxaparin at a dose of 1.7 mg/kg/day. A hematology consult was requested for the management of coagulopathy; however, it could not be performed as the hospital lacked this service.

At 72 hours, alteplase therapy was initiated at a dose of 0.1 mcg/kg/h following the administration of fresh frozen plasma (10 mL/kg) and a heparin infusion (10 U/kg/h) for 72 hours. Echocardiographic assessments, conducted twice daily, demonstrated a 90% reduction in thrombus size within 48 hours, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram, Apical 4-Chamber View. The echocardiogram shows the resolution of the previously identified thrombus.

Figure 5.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram, Apical 4-Chamber View. The echocardiogram shows the resolution of the previously identified thrombus.

Figure 6.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram, Apical 4-Chamber View. The echocardiogram shows a recurrent thrombus measuring 1.5 x 1.8 cm, attached to the interatrial septum and pendulous during systole.

Figure 6.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram, Apical 4-Chamber View. The echocardiogram shows a recurrent thrombus measuring 1.5 x 1.8 cm, attached to the interatrial septum and pendulous during systole.

Figure 7.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram, Apical 4-Chamber View. The same thrombus is observed, descending through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle during diastole.

Figure 7.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram, Apical 4-Chamber View. The same thrombus is observed, descending through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle during diastole.

The patient’s condition worsened, with bilateral pleural effusions requiring thoracentesis, leading to shock and death at 15 days of life.

A transfontanellar ultrasound was performed at the time of admission, throughout hospitalization, and at discharge. All scans reported no evidence of intracranial bleeding

4. Discussion

In neonates, the physiological process that controls bleeding and maintains blood vessel integrity (hemostasis) is immature and undergoes significant changes during the first six months of life [

5]. Several factors contribute to the increased susceptibility of neonates to thrombotic events:

Lower levels of anticoagulant proteins, such as protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III, which are essential for inhibiting coagulation; Limited capacity of the fibrinolytic system, responsible for clot dissolution; Reduced platelet adhesion and aggregation; and Lower levels of immunoglobulins, particularly IgG, which affect both the immune response and hemostasis [

6].

Additionally, conditions such as sepsis, inflammation, hypoxia, and the presence of invasive devices or catheters further increase the risk of thrombosis. This is exacerbated by the small vessel diameter, high-osmolarity solutions, and impaired regulation of thrombopoiesis in neonates [

7].

Despite these vulnerabilities, certain aspects of the neonatal hemostatic system are compensatory, facilitating the maintenance of a dynamic equilibrium between coagulation and fibrinolysis in normal conditions. However, under stress, the limited reserves of the neonatal hemostatic system may fail, significantly increasing the risk of thrombosis in critically ill neonates [

7].

When using central venous catheters, several risk factors should be considered: the catheter’s location, the use of multilumen catheters, prolonged catheter duration (over 14 days, although some guidelines suggest durations exceeding six days also pose a risk), improper placement, the administration of parenteral nutrition, and the infusion of blood products [

7,

8].

Catheter insertion can damage the vascular endothelium, especially in neonates with small-caliber vessels, triggering inflammatory responses and activating the coagulation cascade. Endothelial injury increases the likelihood of clot formation at the insertion site. Additional contributing factors include vascular occlusion, turbulent or slowed blood flow, the nature of infusions, and the catheter material. The diameter of the catheter relative to the vessel lumen is critical; an oversized catheter can hinder blood flow around it, promoting stasis and thrombosis, particularly if the catheter remains in place for over 14 days [

8].

In neonates, thrombopoietin levels, which regulate platelet production, are elevated. Once a thrombus forms, treatment depends on its location and clinical severity [

9]

If necessary, central catheters should be removed after at least 3–5 days of anticoagulation, unless access to the vena cava is critical and the catheter remains functional [

7]. For a first thrombosis episode involving the vena cava, prophylactic enoxaparin is recommended, with dosing adjusted to prolong the partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and achieve anti-Xa levels between 0.5 and 1.0 U/mL [

8].

Anticoagulant therapy should continue at therapeutic doses until catheter removal. Thrombolytic therapy is reserved for cases of major vessel occlusion where organ or limb function is critically compromised, given the high risk of complications. In our patient, fibrinolytic therapy was chosen due to the significant embolization risk associated with the thrombus [

9].

The recommended management approach includes:

Central catheter removal: Performed following clinical and ultrasound evaluation.

Anticoagulation: Administration of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) at 1.5–2 mg/kg every 12 hours, adjusting the dose to achieve anti-Xa levels of 0.5–1 U/mL. Enoxaparin is the most commonly used LMWH in neonatology.

Thrombolysis: Indicated when anticoagulation fails or urgent reestablishment of flow is necessary. Thrombolytic agents can be administered intravenously or locally via intra-arterial or intrathrombus catheters. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), such as alteplase, is preferred in neonates due to fewer side effects compared to urokinase or streptokinase, although conclusive studies on dosing and duration are lacking. Typical doses range from 0.25–1 mg/kg/day, with intracerebral hemorrhage as the primary adverse reaction [

9].

Surgical thrombectomy: Considered a last resort due to the low body weight and high mortality risk in neonates, it is only employed when all other options fail [

10].

LMWH acts by inhibiting coagulation factors and platelet function, enhancing fibrinolysis, and promoting antithrombin activation. It specifically targets thrombin and factor Xa, though the optimal dosing, efficacy, and side effects of thrombolytic therapy in neonates remain unclear [

11].

In neonatal thrombolysis, daily cranial ultrasounds are essential, along with thrombus imaging every 12–24 hours. Thrombolytic infusion should be stopped once the clot dissolves or complications arise. Reocclusion remains a potential issue following fibrinolytic therapy [

9]. There is no consensus regarding the concurrent or subsequent use of heparin during rtPA infusion or the duration of administration. A median infusion dose of 0.2 mg/kg/h (range 0.15–0.3 mg/kg/h) has been shown to be effective and safe. Although the indications and dosing for thrombolytic therapy in neonates are not standardized, it may reduce long-term complications in selected patients [

11].

Careful catheter placement, appropriate site selection, and vigilant monitoring of neonates are critical for the early detection of thrombosis. Understanding neonatal hemostatic physiology is key to minimizing risks [

10]. Preventive strategies, such as anticoagulation during catheter placement, positioning the catheter tip outside the atrium, and ongoing medical education, may reduce the incidence and complications of thrombosis [

12].

The current approach to neonatal thrombosis treatment remains challenging, as no specific therapeutic protocol exists for this population due to the high risk of complications.

The use of enoxaparin in low-risk thrombi appears safe in neonates, although thrombolysis may require more time. Outpatient management with aspirin (ASA) is a viable option until resolution. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator should be reserved for thrombi with a high embolization risk due to its associated complications. Treatment safety and efficacy depend on the patient’s clinical condition, guided by clinical and ultrasound findings [

13].

Thrombi, depending on their size and location, can cause severe complications, including death, although most do not lead to significant long-term repercussions [

13]. A conservative approach may be justified for thrombi with benign characteristics. Enoxaparin and ASA are safe with proper monitoring, while fibrinolytics are indicated when thrombosis poses a threat to life or organ function, provided no absolute contraindications exist [

14].

The decision-making process in treating the first and second patients highlights the importance of individualized care in managing neonatal thrombotic conditions. An outpatient approach was chosen for the first patient due to the low risk of complications, resulting in satisfactory outcomes. In contrast, fibrinolytic therapy was employed in the second case due to the thrombus location and high embolization risk. Despite the potential for coagulopathy requiring hematological evaluation, the immediate risk of embolization necessitated fibrinolysis.