Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

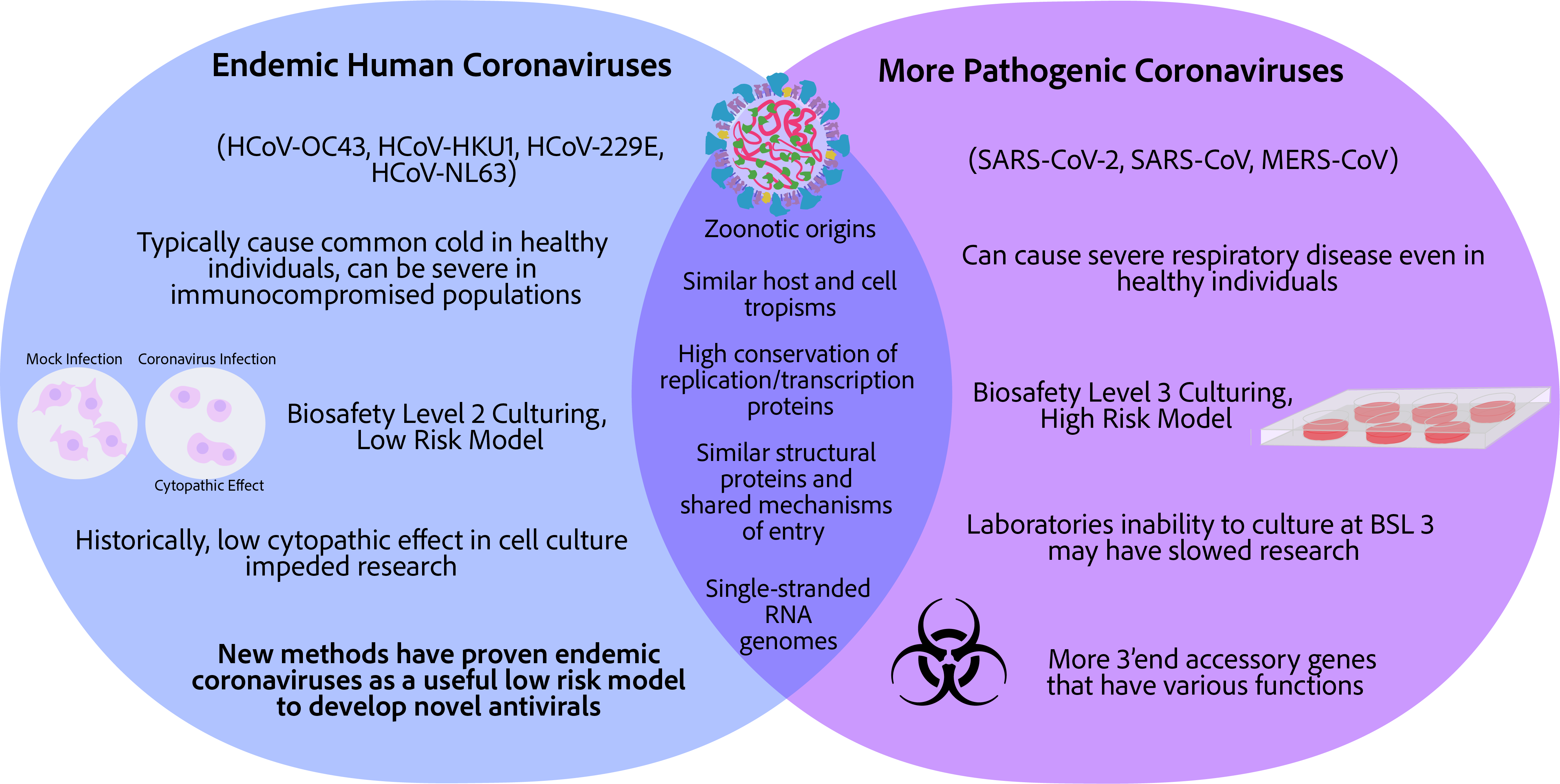

1. Introduction

2. Coronavirus Infection Basics

2.1. The Components of a Coronavirus Virion

2.2. Coronavirus Lifecycle in Brief

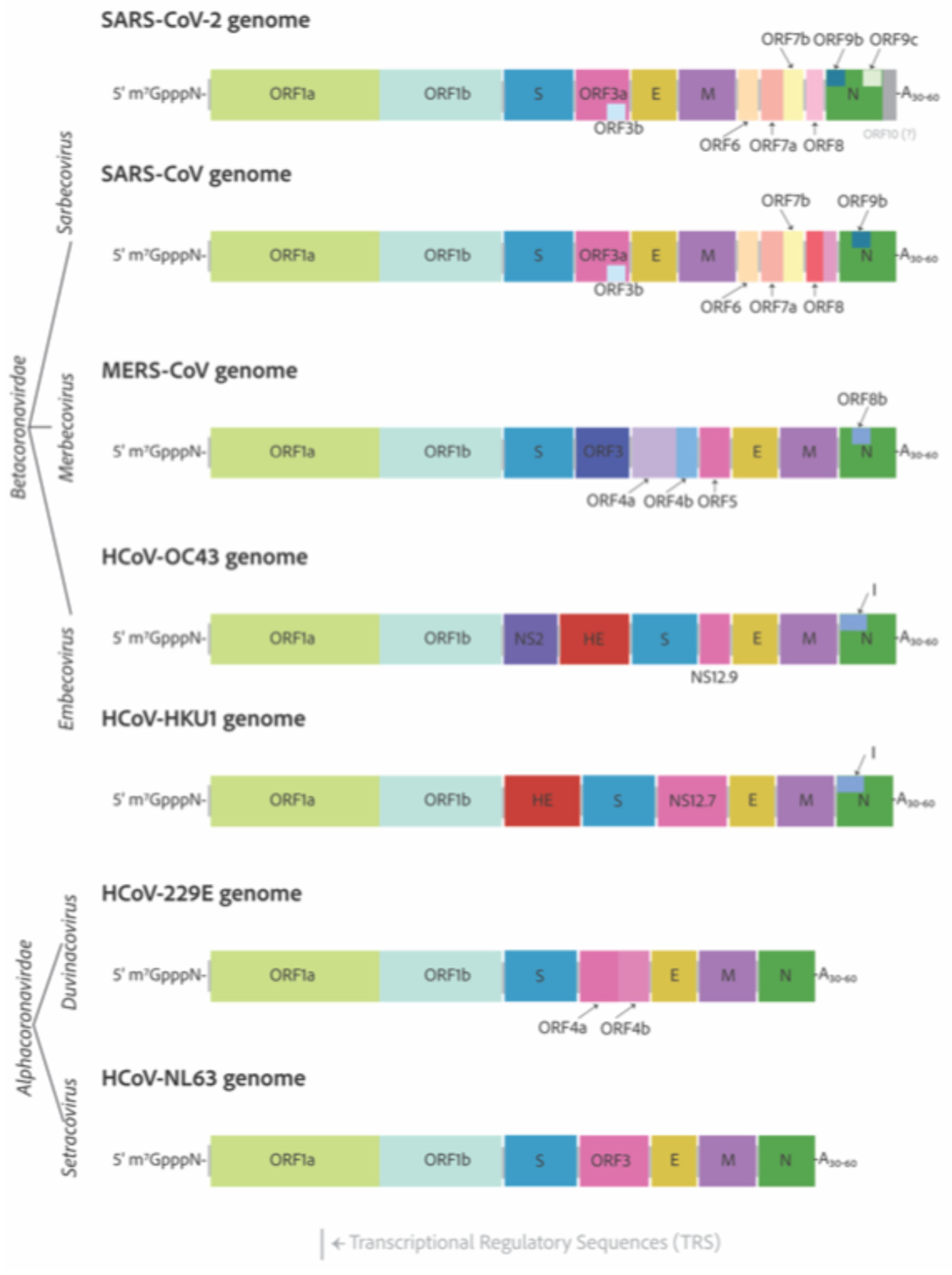

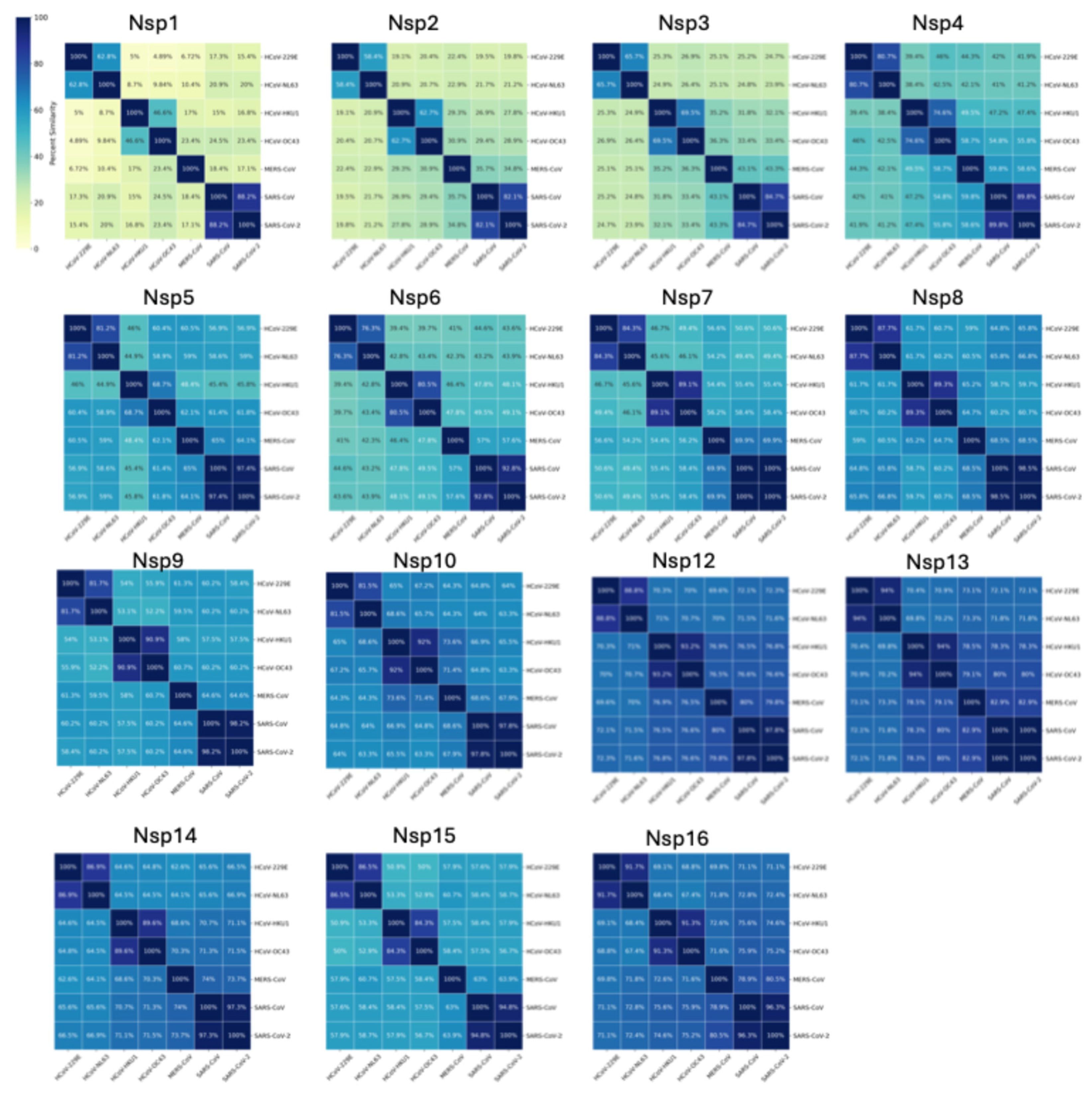

3. Genomes and Basic Genetic Differences

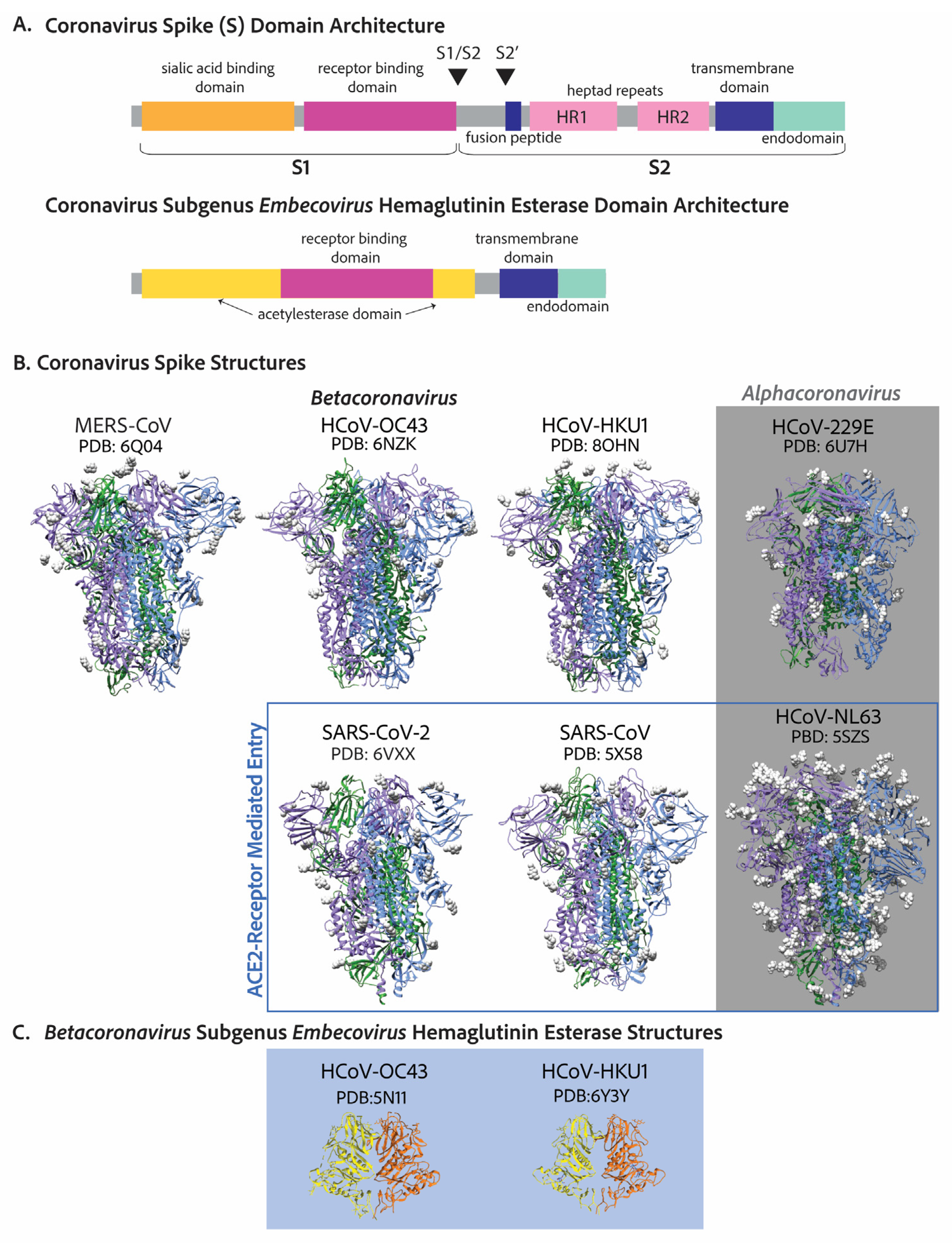

4. Cell Entry

|

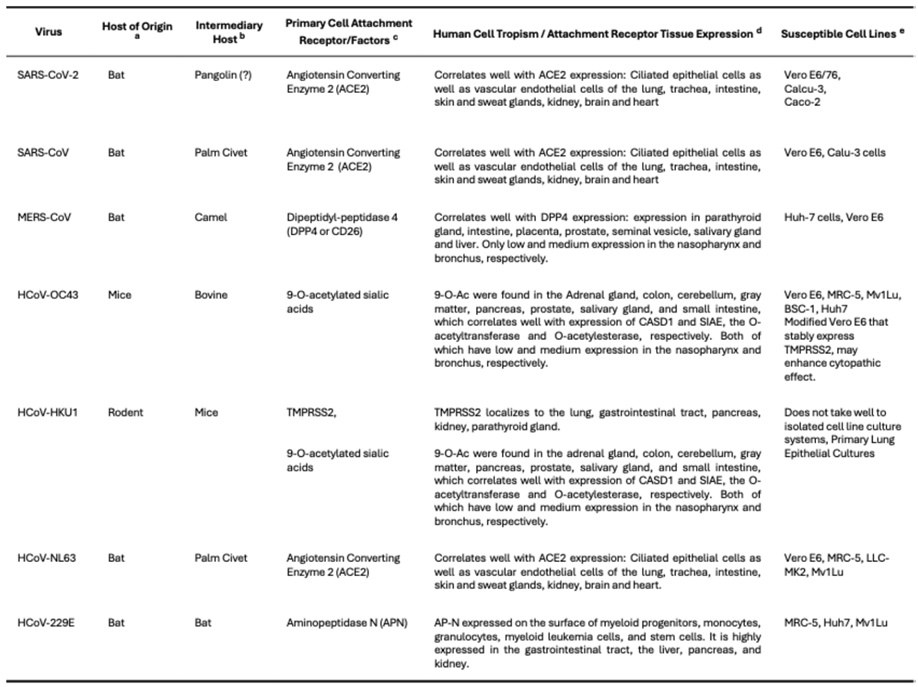

5. Evolution and Host Tropism—Cell Receptors and Cell Tropism

6. Pathogenicity

6.1. How Prevalent Are Endemic Coronaviruses?

6.2. What Kind of Disease Do Endemic Coronaviruses Cause?

6.3. A Note on Endemicity

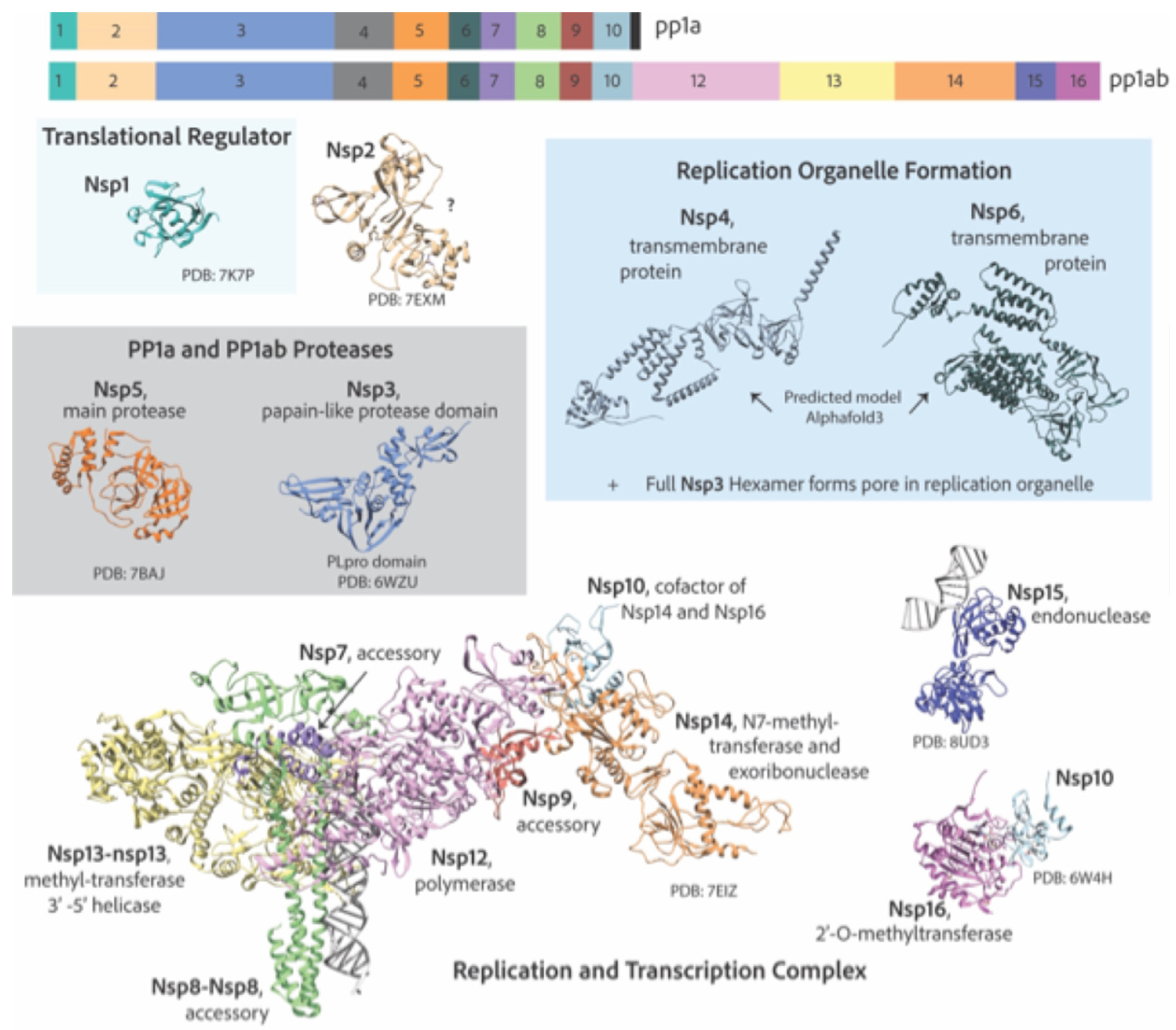

7. Replication and Transcription Proteins

7.1. Reorganization of Cellular Membranes to Form Replication Organelles

7.2. Viral Genome Replication and Transcription Inside Double Membranous Organelles

7.3. RNA Capping

7.4. Additional Functions of Non-Structural Proteins

8. Recent Advancements in Endemic Coronavirus Culturing and Discoveries Found in Endemic Coronaviruses

8.1. Low Viral Yields Impeded Research Involving Endemic Coronaviruses

8.2. Viral Quantification of Endemic Coronaviruses Proved Challenging

8.3. Recent Advancements in Endemic Coronavirus Culturing and Quantification

8.4. Examples of Endemic Coronaviruses as a Surrogate for the More Pathogenic Coronaviruses for Antiviral Discovery

9. Conclusions and Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaimes, J.A.; Andre, N.M.; Chappie, J.S.; Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Phylogenetic Analysis and Structural Modeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Reveals an Evolutionary Distinct and Proteolytically Sensitive Activation Loop. J Mol Biol 2020, 432, 3309–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shah, T.; Wang, B.; Qu, L.; Wang, R.; Hou, Y.; Baloch, Z.; Xia, X. Cross-species transmission, evolution and zoonotic potential of coronaviruses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1081370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Hoek, L. Human coronaviruses: what do they cause? Antivir Ther 2007, 12, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburne, A.F.; Bynoe, M.L.; Tyrrell, D.A. Effects of a “new” human respiratory virus in volunteers. Br Med J 1967, 3, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburne, A.F.; Somerset, B.A. Coronative antibody tires in sera of healthy adults and experimentally infected volunteers. J Hyg (Lond) 1972, 70, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ksiazek, T.G.; Erdman, D.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Zaki, S.R.; Peret, T.; Emery, S.; Tong, S.; Urbani, C.; Comer, J.A.; Lim, W.; et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003, 348, 1953–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, P.A.; Oberste, M.S.; Monroe, S.S.; Nix, W.A.; Campagnoli, R.; Icenogle, J.P.; Penaranda, S.; Bankamp, B.; Maher, K.; Chen, M.H.; et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 2003, 300, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosten, C.; Gunther, S.; Preiser, W.; van der Werf, S.; Brodt, H.R.; Becker, S.; Rabenau, H.; Panning, M.; Kolesnikova, L.; Fouchier, R.A.; et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003, 348, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrc, K.; Berkhout, B.; van der Hoek, L. The novel human coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1. J Virol 2007, 81, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Hoek, L.; Pyrc, K.; Jebbink, M.F.; Vermeulen-Oost, W.; Berkhout, R.J.; Wolthers, K.C.; Wertheim-van Dillen, P.M.; Kaandorp, J.; Spaargaren, J.; Berkhout, B. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med 2004, 10, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.; Lau, S.K.; Chu, C.M.; Chan, K.H.; Tsoi, H.W.; Huang, Y.; Wong, B.H.; Poon, R.W.; Cai, J.J.; Luk, W.K.; et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol 2005, 79, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouchier, R.A.; Hartwig, N.G.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Niemeyer, B.; de Jong, J.C.; Simon, J.H.; Osterhaus, A.D. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101, 6212–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fausto, A.; Otter, C.J.; Bracci, N.; Weiss, S.R. Improved Culture Methods for Human Coronaviruses HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63. Curr Protoc 2023, 3, e914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memish, Z.A.; Zumla, A.I.; Al-Hakeem, R.F.; Al-Rabeeah, A.A.; Stephens, G.M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med 2013, 368, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahkarami, M.; Yen, C.; Glaser, C.; Xia, D.; Watt, J.; Wadford, D.A. Laboratory Testing for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, California, USA, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 1664–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zai, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Potential of large “first generation” human-to-human transmission of 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmaker, L.; Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Verbeke, R.; Kersten, G.; Jiskoot, W.; Crommelin, D.J.A. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int J Pharm 2021, 601, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruell, H.; Vanshylla, K.; Weber, T.; Barnes, C.O.; Kreer, C.; Klein, F. Antibody-mediated neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. Immunity 2022, 55, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simon-Campos, A.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Weber, G.; Khoury, J.; Amar, M.; Stein, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Saliba, W. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in Reducing Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Mortality in High-Risk Patients. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, R.; Watanabe, N.; Bandou, R.; Yoshida, T.; Daidoji, T.; Naito, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Nakaya, T. A Cytopathic Effect-Based Tissue Culture Method for HCoV-OC43 Titration Using TMPRSS2-Expressing VeroE6 Cells. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirtzinger, E.E.; Kim, Y.; Davis, A.S. Improving human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) research comparability in studies using HCoV-OC43 as a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2. J Virol Methods 2022, 299, 114317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I.; Lee, C. Human Coronavirus OC43 as a Low-Risk Model to Study COVID-19. Viruses 2023, 15, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, P.S.; Perlman, S. Coronaviridae. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Howley, P.M., Knipe, D.M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philidelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 825–858. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.D.; Tyrrell, D.A. The morphology of three previously uncharacterized human respiratory viruses that grow in organ culture. J Gen Virol 1967, 1, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudoux, P.; Carrat, C.; Besnardeau, L.; Charley, B.; Laude, H. Coronavirus pseudoparticles formed with recombinant M and E proteins induce alpha interferon synthesis by leukocytes. J Virol 1998, 72, 8636–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guruprasad, L. Human coronavirus spike protein-host receptor recognition. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2021, 161, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S.; Millet, J.K. Coronavirus entry: how we arrived at SARS-CoV-2. Curr Opin Virol 2021, 47, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Langereis, M.A.; van Vliet, A.L.; Huizinga, E.G.; de Groot, R.J. Structure of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase offers insight into corona and influenza virus evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 9065–9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Koerhuis, D.; van den Burg, A.C.S.; Rozemuller, E.; Bosch, B.J.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Boons, G.J.; Huizinga, E.G.; et al. Coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase and spike proteins coevolve for functional balance and optimal virion avidity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 25759–25770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belshaw, R.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A. The evolution of genome compression and genomic novelty in RNA viruses. Genome Res 2007, 17, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, S. Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses. Stem Cell Res 2020, 50, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milewska, A.; Nowak, P.; Owczarek, K.; Szczepanski, A.; Zarebski, M.; Hoang, A.; Berniak, K.; Wojarski, J.; Zeglen, S.; Baster, Z.; et al. Entry of Human Coronavirus NL63 into the Cell. J Virol 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, K.; Szczepanski, A.; Milewska, A.; Baster, Z.; Rajfur, Z.; Sarna, M.; Pyrc, K. Early events during human coronavirus OC43 entry to the cell. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielian, M.; Rey, F.A. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: more than one way to make a hairpin. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuniga, S.; Cruz, J.L.; Sola, I.; Mateos-Gomez, P.A.; Palacio, L.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus nucleocapsid protein facilitates template switching and is required for efficient transcription. J Virol 2010, 84, 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuniga, S.; Sola, I.; Moreno, J.L.; Sabella, P.; Plana-Duran, J.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus nucleocapsid protein is an RNA chaperone. Virology 2007, 357, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohlman, S.A.; Baric, R.S.; Nelson, G.N.; Soe, L.H.; Welter, L.M.; Deans, R.J. Specific interaction between coronavirus leader RNA and nucleocapsid protein. J Virol 1988, 62, 4288–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazan, F.; Galan, C.; Enjuanes, L. The nucleoprotein is required for efficient coronavirus genome replication. J Virol 2004, 78, 12683–12688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturman, L.S.; Holmes, K.V. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res 1983, 28, 35–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturman, L.S.; Holmes, K.V. Characterization of coronavirus II. Glycoproteins of the viral envelope: tryptic peptide analysis. Virology 1977, 77, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, F.; Khan, K.S.; Le, T.K.; Paris, C.; Demirbag, S.; Barfuss, P.; Rocchi, P.; Ng, W.L. Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting. Mol Cell 2020, 80, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; Decroly, E.; Ziebuhr, J. The Nonstructural Proteins Directing Coronavirus RNA Synthesis and Processing. Adv Virus Res 2016, 96, 59–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebuhr, J.; Snijder, E.J.; Gorbalenya, A.E. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J Gen Virol 2000, 81, 853–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Dobbe, J.C.; Thiel, V.; Ziebuhr, J.; Poon, L.L.; Guan, Y.; Rozanov, M.; Spaan, W.J.; Gorbalenya, A.E. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J Mol Biol 2003, 331, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, M.M.; Akhlaghpour, M.; Neuman, B.W.; Buchmeier, M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural proteins 3, 4, and 6 induce double-membrane vesicles. mBio 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosert, R.; Kanjanahaluethai, A.; Egger, D.; Bienz, K.; Baker, S.C. RNA replication of mouse hepatitis virus takes place at double-membrane vesicles. J Virol 2002, 76, 3697–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; Limpens, R.; de Wilde, A.H.; de Jong, A.W.M.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Maier, H.J.; Faas, F.; Koster, A.J.; Barcena, M. A unifying structural and functional model of the coronavirus replication organelle: Tracking down RNA synthesis. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, G.; Limpens, R.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Laugks, U.; Zheng, S.; de Jong, A.W.M.; Koning, R.I.; Agard, D.A.; Grunewald, K.; Koster, A.J.; et al. A molecular pore spans the double membrane of the coronavirus replication organelle. Science 2020, 369, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevajol, M.; Subissi, L.; Decroly, E.; Canard, B.; Imbert, I. Insights into RNA synthesis, capping, and proofreading mechanisms of SARS-coronavirus. Virus Res 2014, 194, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sola, I.; Almazan, F.; Zuniga, S.; Enjuanes, L. Continuous and Discontinuous RNA Synthesis in Coronaviruses. Annu Rev Virol 2015, 2, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, S.; Matsuoka, Y.; Ueshiba, H.; Komatsu, N.; Itoh, K.; Shichijo, S.; Kanai, T.; Fukushi, M.; Ishida, I.; Kirikae, T.; et al. Dissection and identification of regions required to form pseudoparticles by the interaction between the nucleocapsid (N) and membrane (M) proteins of SARS coronavirus. Virology 2008, 380, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Dellibovi-Ragheb, T.A.; Kerviel, A.; Pak, E.; Qiu, Q.; Fisher, M.; Takvorian, P.M.; Bleck, C.; Hsu, V.W.; Fehr, A.R.; et al. beta-Coronaviruses Use Lysosomes for Egress Instead of the Biosynthetic Secretory Pathway. Cell 2020, 183, 1520–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forni, D.; Cagliani, R.; Pozzoli, U.; Mozzi, A.; Arrigoni, F.; De Gioia, L.; Clerici, M.; Sironi, M. Dating the Emergence of Human Endemic Coronaviruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, D.; Cagliani, R.; Clerici, M.; Sironi, M. Molecular Evolution of Human Coronavirus Genomes. Trends Microbiol 2017, 25, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forni, D.; Cagliani, R.; Arrigoni, F.; Benvenuti, M.; Mozzi, A.; Pozzoli, U.; Clerici, M.; De Gioia, L.; Sironi, M. Adaptation of the endemic coronaviruses HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E to the human host. Virus Evol 2021, 7, veab061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesheh, M.M.; Hosseini, P.; Soltani, S.; Zandi, M. An overview on the seven pathogenic human coronaviruses. Rev Med Virol 2022, 32, e2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, K.; Ping, X.; Yu, W.; Qian, Z.; Xiong, S.; Sun, B. The ns12.9 Accessory Protein of Human Coronavirus OC43 Is a Viroporin Involved in Virion Morphogenesis and Pathogenesis. J Virol 2015, 89, 11383–11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, S.; Gerlich, S.; Khan, A.; Rodl, S.; Bokenkamp, J.E.; Peker, E.; Zarges, C.; Faust, J.; Storchova, Z.; Raschle, M.; et al. The Orf9b protein of SARS-CoV-2 modulates mitochondrial protein biogenesis. J Cell Biol 2023, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.R.; Ye, Z.W.; Lui, P.Y.; Zheng, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, L.; Fung, S.Y.; Yuen, K.S.; Siu, K.L.; Yeung, M.L.; et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus ORF8b Accessory Protein Suppresses Type I IFN Expression by Impeding HSP70-Dependent Activation of IRF3 Kinase IKKepsilon. J Immunol 2020, 205, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriwilaijaroen, N.; Suzuki, Y. Roles of Sialyl Glycans in HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2556, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pohlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Ye, G.; Shi, K.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Aihara, H.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 581, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, G.; Nelli, R.K.; Phadke, K.S.; Bravo-Parra, M.; Mora-Diaz, J.C.; Bellaire, B.H.; Gimenez-Lirola, L.G. SARS-CoV-2 Is More Efficient than HCoV-NL63 in Infecting a Small Subpopulation of ACE2+ Human Respiratory Epithelial Cells. Viruses 2023, 15, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, H.; Pyrc, K.; van der Hoek, L.; Geier, M.; Berkhout, B.; Pohlmann, S. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102, 7988–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Shi, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Tong, P.; Guo, D.; Fu, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res 2013, 23, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Tomlinson, A.C.; Wong, A.H.; Zhou, D.; Desforges, M.; Talbot, P.J.; Benlekbir, S.; Rubinstein, J.L.; Rini, J.M. The human coronavirus HCoV-229E S-protein structure and receptor binding. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Pu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. TMPRSS2 and glycan receptors synergistically facilitate coronavirus entry. Cell 2024, 187, 4261–4271.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, N.; Schwartz, O. [TMPRSS2 is the receptor of seasonal coronavirus HKU1]. Med Sci (Paris) 2024, 40, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Walls, A.C.; Wang, Z.; Sauer, M.M.; Li, W.; Tortorici, M.A.; Bosch, B.J.; DiMaio, F.; Veesler, D. Structures of MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein in complex with sialoside attachment receptors. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2019, 26, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitjean, S.J.L.; Chen, W.; Koehler, M.; Jimmidi, R.; Yang, J.; Mohammed, D.; Juniku, B.; Stanifer, M.L.; Boulant, S.; Vincent, S.P.; et al. Multivalent 9-O-Acetylated-sialic acid glycoclusters as potent inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomris, I.; Unione, L.; Nguyen, L.; Zaree, P.; Bouwman, K.M.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Fok, J.A.; Rios Carrasco, M.; van der Woude, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike N-Terminal Domain Engages 9-O-Acetylated alpha2-8-Linked Sialic Acids. ACS Chem Biol 2023, 18, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M.A.; Walls, A.C.; Lang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Koerhuis, D.; Boons, G.J.; Bosch, B.J.; Rey, F.A.; de Groot, R.J.; et al. Structural basis for human coronavirus attachment to sialic acid receptors. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2019, 26, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.A.; Moons, S.J.; Timmermans, S.; de Jong, H.; Boltje, T.J.; Bull, C. Sialic acid O-acetylation: From biosynthesis to roles in health and disease. J Biol Chem 2021, 297, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Hesketh, E.L.; Shamorkina, T.M.; Li, W.; Franken, P.J.; Drabek, D.; van Haperen, R.; Townend, S.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Grosveld, F.; et al. Antigenic structure of the human coronavirus OC43 spike reveals exposed and occluded neutralizing epitopes. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rasool, S.; Fielding, B.C. Understanding Human Coronavirus HCoV-NL63. Open Virol J 2010, 4, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronker, M.F.; Creutznacher, R.; Drulyte, I.; Hulswit, R.J.G.; Li, Z.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Snijder, J.; Lang, Y.; Bosch, B.J.; Boons, G.J.; et al. Sialoglycan binding triggers spike opening in a human coronavirus. Nature 2023, 624, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkers, M.J.; Lang, Y.; Feitsma, L.J.; Hulswit, R.J.; de Poot, S.A.; van Vliet, A.L.; Margine, I.; de Groot-Mijnes, J.D.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.; Langereis, M.A.; et al. Betacoronavirus Adaptation to Humans Involved Progressive Loss of Hemagglutinin-Esterase Lectin Activity. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurdiss, D.L.; Drulyte, I.; Lang, Y.; Shamorkina, T.M.; Pronker, M.F.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Snijder, J.; de Groot, R.J. Cryo-EM structure of coronavirus-HKU1 haemagglutinin esterase reveals architectural changes arising from prolonged circulation in humans. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, V.M.; Muth, D.; Niemeyer, D.; Drosten, C. Hosts and Sources of Endemic Human Coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res 2018, 100, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D. Human coronaviruses: Origin, host and receptor. J Clin Virol 2022, 155, 105246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmam, S.; Vongphayloth, K.; Baquero, E.; Munier, S.; Bonomi, M.; Regnault, B.; Douangboubpha, B.; Karami, Y.; Chretien, D.; Sanamxay, D.; et al. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells. Nature 2022, 604, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Protein Atlas. Available online: proteinatlas.

- Uhlen, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; Sjostedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, K.N.; Wasik, B.R.; LaClair, J.R.; Buchholz, D.W.; Weichert, W.S.; Alford-Lawrence, B.K.; Aguilar, H.C.; Parrish, C.R. Expression of 9-O- and 7,9-O-Acetyl Modified Sialic Acid in Cells and Their Effects on Influenza Viruses. mBio 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Krishna, M.; Varki, N.M.; Varki, A. 9-O-acetylated sialic acids have widespread but selective expression: analysis using a chimeric dual-function probe derived from influenza C hemagglutinin-esterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91, 7782–7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langereis, M.A.; Bakkers, M.J.; Deng, L.; Padler-Karavani, V.; Vervoort, S.J.; Hulswit, R.J.; van Vliet, A.L.; Gerwig, G.J.; de Poot, S.A.; Boot, W.; et al. Complexity and Diversity of the Mammalian Sialome Revealed by Nidovirus Virolectins. Cell Rep 2015, 11, 1966–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, A.C.; Burkett, S.E.; Yount, B.; Pickles, R.J. SARS-CoV replication and pathogenesis in an in vitro model of the human conducting airway epithelium. Virus Res 2008, 133, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Ho, C.T.; Chuo, W.H.; Li, S.; Wang, T.T.; Lin, C.C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect Dis 2017, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, J. Cytopathic Effect Assay and Plaque Assay to Evaluate in vitro Activity of Antiviral Compounds Against Human Coronaviruses 229E, OC43, and NL63. Bio Protoc 2022, 12, e4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, H.L.; Bonavita, C.M.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Vilchez, B.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Anthony, S.J. The coronavirus recombination pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, H.L.; Letko, M.; Lasso, G.; Ssebide, B.; Nziza, J.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Liang, E.; Cranfield, M.; Han, B.A.; et al. The evolutionary history of ACE2 usage within the coronavirus subgenus Sarbecovirus. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; Lemey, P.; Jiang, X.; Lam, T.T.; Perry, B.W.; Castoe, T.A.; Rambaut, A.; Robertson, D.L. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Microbiol 2020, 5, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, S.; Xia, W.; Hughes, J.; Jiang, X.; Robertson, D.L. The animal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 373, 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenizia, C.; Galbiati, S.; Vanetti, C.; Vago, R.; Clerici, M.; Tacchetti, C.; Daniele, T. SARS-CoV-2 Entry: At the Crossroads of CD147 and ACE2. Cells 2021, 10, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qiu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Deng, X.; Xu, W.; Zheng, T.; Wu, P.; Xie, S.; Bian, W.; Zhang, C.; et al. AXL is a candidate receptor for SARS-CoV-2 that promotes infection of pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Res 2021, 31, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Lv, Y.; Moser, D.; Zhou, X.; Woehrle, T.; Han, L.; Osterman, A.; Rudelius, M.; Chouker, A.; Lei, P. ACE2-independent SARS-CoV-2 virus entry through cell surface GRP78 on monocytes—evidence from a translational clinical and experimental approach. EBioMedicine 2023, 98, 104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Yang, M.; Duan, Z.; Liu, L.; Lu, S.; Ma, L.; Cheng, R.; Wang, G.; et al. Human transferrin receptor can mediate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2024, 121, e2317026121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggen, J.; Jacquemyn, M.; Persoons, L.; Vanstreels, E.; Pye, V.E.; Wrobel, A.G.; Calvaresi, V.; Martin, S.R.; Roustan, C.; Cronin, N.B.; et al. TMEM106B is a receptor mediating ACE2-independent SARS-CoV-2 cell entry. Cell 2023, 186, 3427–3442.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. Cellular Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 across Human Tissues and Age-related Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in Immune-inflammatory Stromal Cells. Aging Dis 2021, 12, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.; Lee, P.; Tsang, A.K.; Yip, C.C.; Tse, H.; Lee, R.A.; So, L.Y.; Lau, Y.L.; Chan, K.H.; Woo, P.C.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination. J Virol 2011, 85, 11325–11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berche, P. The enigma of the 1889 Russian flu pandemic: A coronavirus? Presse Med 2022, 51, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monto, A.S.; DeJonge, P.M.; Callear, A.P.; Bazzi, L.A.; Capriola, S.B.; Malosh, R.E.; Martin, E.T.; Petrie, J.G. Coronavirus Occurrence and Transmission Over 8 Years in the HIVE Cohort of Households in Michigan. J Infect Dis 2020, 222, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, J.G.; Bazzi, L.A.; McDermott, A.B.; Follmann, D.; Esposito, D.; Hatcher, C.; Mateja, A.; Narpala, S.R.; O’Connell, S.E.; Martin, E.T.; et al. Coronavirus Occurrence in the Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) Cohort of Michigan Households: Reinfection Frequency and Serologic Responses to Seasonal and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronaviruses. J Infect Dis 2021, 224, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, S.R.; Bazzi, L.A.; Callear, A.P.; Petrie, J.G.; Malosh, R.E.; Foster-Tucker, J.E.; Smith, M.; Ibiebele, J.; McDermott, A.; Rolfes, M.A.; et al. Respiratory virus circulation during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) cohort. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023, 17, e13106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.M.; Winn, A.; Dahl, R.M.; Kniss, K.L.; Silk, B.J.; Killerby, M.E. Seasonality of Common Human Coronaviruses, United States, 2014-2021(1). Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killerby, M.E.; Biggs, H.M.; Haynes, A.; Dahl, R.M.; Mustaquim, D.; Gerber, S.I.; Watson, J.T. Human coronavirus circulation in the United States 2014-2017. J Clin Virol 2018, 101, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Gwee, S.X.W.; Ng, J.Q.X.; Lau, N.; Koh, J.; Pang, J. Wastewater surveillance to infer COVID-19 transmission: A systematic review. Sci Total Environ 2022, 804, 150060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, A.B.; Hughes, B.; Duong, D.; Chan-Herur, V.; Buchman, A.; Wolfe, M.K.; White, B.J. Wastewater concentrations of human influenza, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, and seasonal coronavirus nucleic-acids during the COVID-19 pandemic: a surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e340–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamre, D.; Procknow, J.J. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1966, 121, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, K.; Becker, W.B.; Chanock, R.M. Growth in suckling-mouse brain of “IBV-like” viruses from patients with upper respiratory tract disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1967, 58, 2268–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Guo, X.; Esper, F.; Weibel, C.; Kahn, J.S. Seroepidemiology of group I human coronaviruses in children. J Clin Virol 2007, 40, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkman, R.; Jebbink, M.F.; El Idrissi, N.B.; Pyrc, K.; Muller, M.A.; Kuijpers, T.W.; Zaaijer, H.L.; van der Hoek, L. Human coronavirus NL63 and 229E seroconversion in children. J Clin Microbiol 2008, 46, 2368–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerna, G.; Campanini, G.; Rovida, F.; Percivalle, E.; Sarasini, A.; Marchi, A.; Baldanti, F. Genetic variability of human coronavirus OC43-, 229E-, and NL63-like strains and their association with lower respiratory tract infections of hospitalized infants and immunocompromised patients. J Med Virol 2006, 78, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogimi, C.; Englund, J.A.; Bradford, M.C.; Qin, X.; Boeckh, M.; Waghmare, A. Characteristics and Outcomes of Coronavirus Infection in Children: The Role of Viral Factors and an Immunocompromised State. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019, 8, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Sun, H.; Ma, W.; Fang, T. A case of coronavirus HKU1 encephalitis. Acta Virol 2020, 64, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.J.; Zhou, M.Y.; He, X.Q.; Wu, Y.; Xie, X.L. The Role of Human Coronavirus Infection in Pediatric Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020, 39, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbour, N.; Day, R.; Newcombe, J.; Talbot, P.J. Neuroinvasion by human respiratory coronaviruses. J Virol 2000, 74, 8913–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.N.; Mounir, S.; Talbot, P.J. Human coronavirus gene expression in the brains of multiple sclerosis patients. Virology 1992, 191, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, N.; Cote, G.; Lachance, C.; Tardieu, M.; Cashman, N.R.; Talbot, P.J. Acute and persistent infection of human neural cell lines by human coronavirus OC43. J Virol 1999, 73, 3338–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, P.J.; Desforges, M.; St-Jean, J.; Jacomy, H. Coronavirus neuropathogenesis: could SARS be the tip of the iceberg? BMC Proc 2008, 2, S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, J.D.; Krogstad, P. SARS: the first pandemic of the 21st century. Pediatr Res 2004, 56, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-(mers-cov).

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19).

- Antia, R.; Halloran, M.E. Transition to endemicity: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2021, 54, 2172–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Boon, J.A.; Ahlquist, P. Organelle-like membrane compartmentalization of positive-strand RNA virus replication factories. Annu Rev Microbiol 2010, 64, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Krijnse-Locker, J. Modification of intracellular membrane structures for virus replication. Nat Rev Microbiol 2008, 6, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belov, G.A.; Nair, V.; Hansen, B.T.; Hoyt, F.H.; Fischer, E.R.; Ehrenfeld, E. Complex dynamic development of poliovirus membranous replication complexes. J Virol 2012, 86, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktorova, E.G.; Nchoutmboube, J.A.; Ford-Siltz, L.A.; Iverson, E.; Belov, G.A. Phospholipid synthesis fueled by lipid droplets drives the structural development of poliovirus replication organelles. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, P.; Blanchard, E.; Roingeard, P. Ultrastructural and biochemical analyses of hepatitis C virus-associated host cell membranes. J Gen Virol 2010, 91, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerflinger, S.Y.; Cortese, M.; Romero-Brey, I.; Menne, Z.; Tubiana, T.; Schenk, C.; White, P.A.; Bartenschlager, R.; Bressanelli, S.; Hansman, G.S.; et al. Membrane alterations induced by nonstructural proteins of human norovirus. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoops, K.; Barcena, M.; Limpens, R.W.; Koster, A.J.; Mommaas, A.M.; Snijder, E.J. Ultrastructural characterization of arterivirus replication structures: reshaping the endoplasmic reticulum to accommodate viral RNA synthesis. J Virol 2012, 86, 2474–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooze, J.; Tooze, S.; Warren, G. Replication of coronavirus MHV-A59 in sac- cells: determination of the first site of budding of progeny virions. Eur J Cell Biol 1984, 33, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- David-Ferreira, J.F.; Manaker, R.A. An Electron Microscope Study of the Development of a Mouse Hepatitis Virus in Tissue Culture Cells. J Cell Biol 1965, 24, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, C.S.; Tatti, K.M.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E.; Comer, J.A.; Lee, W.W.; Rota, P.A.; Bankamp, B.; Bellini, W.J.; Zaki, S.R. Ultrastructural characterization of SARS coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis 2004, 10, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijder, E.J.; van der Meer, Y.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.; Onderwater, J.J.; van der Meulen, J.; Koerten, H.K.; Mommaas, A.M. Ultrastructure and origin of membrane vesicles associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication complex. J Virol 2006, 80, 5927–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hemert, M.J.; van den Worm, S.H.; Knoops, K.; Mommaas, A.M.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Snijder, E.J. SARS-coronavirus replication/transcription complexes are membrane-protected and need a host factor for activity in vitro. PLoS Pathog 2008, 4, e1000054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, S. Double-Stranded RNA Sensors and Modulators in Innate Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2019, 37, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, P.; Johnson, M.A.; Almeida, M.S.; Horst, R.; Herrmann, T.; Joseph, J.S.; Neuman, B.W.; Subramanian, V.; Saikatendu, K.S.; Buchmeier, M.J.; et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the N-terminal domain of nonstructural protein 3 from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 2007, 81, 12049–12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, K.R.; Koetzner, C.A.; Masters, P.S. Characterization of a critical interaction between the coronavirus nucleocapsid protein and nonstructural protein 3 of the viral replicase-transcriptase complex. J Virol 2013, 87, 9159–9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Ge, J.; Huang, Y.C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Gao, S.; et al. Coupling of N7-methyltransferase and 3′-5′ exoribonuclease with SARS-CoV-2 polymerase reveals mechanisms for capping and proofreading. Cell 2021, 184, 3474–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagnola, G.; Govindarajan, V.; Pelletier, A.; Canard, B.; Peersen, O.B. The SARS-CoV nsp12 Polymerase Active Site Is Tuned for Large-Genome Replication. J Virol 2022, 96, e0067122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkolova, E.; Klima, M.; Nencka, R.; Boura, E. Structural analysis of the putative SARS-CoV-2 primase complex. J Struct Biol 2020, 211, 107548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevino, M.A.; Pantoja-Uceda, D.; Laurents, D.V.; Mompean, M. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp8 N-terminal domain folds autonomously and binds dsRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 10041–10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Ge, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, M.; et al. Cryo-EM Structure of an Extended SARS-CoV-2 Replication and Transcription Complex Reveals an Intermediate State in Cap Synthesis. Cell 2021, 184, 184–193.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Lafont, B.A.P.; Sil, D.; Li, Y.; Bollinger, J.M., Jr.; Krebs, C.; Pierson, T.C.; Linehan, W.M.; Rouault, T.A. Fe-S cofactors in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase are potential antiviral targets. Science 2021, 373, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Raza, M.K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.L.; Bollinger, J.M., Jr.; Krebs, C.; Rouault, T.A. An iron-sulfur cluster in the zinc-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 helicase modulates its RNA-binding and -unwinding activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2023, 120, e2303860120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimmons, W.J.; Woods, R.J.; McCrone, J.T.; Woodman, A.; Arnold, J.J.; Yennawar, M.; Evans, R.; Cameron, C.E.; Lauring, A.S. A speed-fidelity trade-off determines the mutation rate and virulence of an RNA virus. PLoS Biol 2018, 16, e2006459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferron, F.; Subissi, L.; Silveira De Morais, A.T.; Le, N.T.T.; Sevajol, M.; Gluais, L.; Decroly, E.; Vonrhein, C.; Bricogne, G.; Canard, B.; et al. Structural and molecular basis of mismatch correction and ribavirin excision from coronavirus RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115, E162–E171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckerle, L.D.; Lu, X.; Sperry, S.M.; Choi, L.; Denison, M.R. High fidelity of murine hepatitis virus replication is decreased in nsp14 exoribonuclease mutants. J Virol 2007, 81, 12135–12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.J.; Osinski, A.; Hernandez, G.; Eitson, J.L.; Majumdar, A.; Tonelli, M.; Henzler-Wildman, K.; Pawlowski, K.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. The mechanism of RNA capping by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2022, 609, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuman, S. The mRNA capping apparatus as drug target and guide to eukaryotic phylogeny. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2001, 66, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, K.; Karousis, E.D.; Jomaa, A.; Scaiola, A.; Echeverria, B.; Gurzeler, L.A.; Leibundgut, M.; Thiel, V.; Muhlemann, O.; Ban, N. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2020, 27, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujanic, L.; Shevchuk, O.; von Kugelgen, N.; Kalinina, A.; Ludwik, K.; Koppstein, D.; Zerna, N.; Sickmann, A.; Chekulaeva, M. The key features of SARS-CoV-2 leader and NSP1 required for viral escape of NSP1-mediated repression. RNA 2022, 28, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Hoskins, I.; Tonn, T.; Garcia, P.D.; Ozadam, H.; Sarinay Cenik, E.; Cenik, C. Genes with 5′ terminal oligopyrimidine tracts preferentially escape global suppression of translation by the SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 protein. RNA 2021, 27, 1025–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Rozovics, J.M.; Narayanan, K.; Semler, B.L.; Makino, S. SARS coronavirus nsp1 protein induces template-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNAs: viral mRNAs are resistant to nsp1-induced RNA cleavage. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, e1002433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kamitani, W.; DeDiego, M.L.; Enjuanes, L.; Matsuura, Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 facilitates efficient propagation in cells through a specific translational shutoff of host mRNA. J Virol 2012, 86, 11128–11137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokugamage, K.G.; Narayanan, K.; Huang, C.; Makino, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus protein nsp1 is a novel eukaryotic translation inhibitor that represses multiple steps of translation initiation. J Virol 2012, 86, 13598–13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saramago, M.; Costa, V.G.; Souza, C.S.; Barria, C.; Domingues, S.; Viegas, S.C.; Lousa, D.; Soares, C.M.; Arraiano, C.M.; Matos, R.G. The nsp15 Nuclease as a Good Target to Combat SARS-CoV-2: Mechanism of Action and Its Inactivation with FDA-Approved Drugs. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, F.; Jacomy, H.; Marceau, G.; Talbot, P.J. Titration of human coronaviruses, HcoV-229E and HCoV-OC43, by an indirect immunoperoxidase assay. Methods Mol Biol 2008, 454, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracci, N.; Pan, H.C.; Lehman, C.; Kehn-Hall, K.; Lin, S.C. Improved plaque assay for human coronaviruses 229E and OC43. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.; Fons, M.; Boldogh, I.; Rabson, A.S. Medical Microbiology. In Effects on Cells, 4th ed.; Baron, S., Ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, A.; Kehn-Hall, K. Viral concentration determination through plaque assays: using traditional and novel overlay systems. J Vis Exp 2014, e52065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baid, K.; Chiok, K.R.; Banerjee, A. Median Tissue Culture Infectious Dose 50 (TCID(50)) Assay to Determine Infectivity of Cytopathic Viruses. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2813, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. American Journal of Epidemiology 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, F.; Jacomy, H.; Marceau, G.; Talbot, P.J. Titration of human coronaviruses using an immunoperoxidase assay. J Vis Exp 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, M. A tale of two antiviral targets—and the COVID-19 drugs that bind them. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2022, 21, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, A.A.; Bullen, C.K.; Villabona-Rueda, A.F.; Thompson, E.A.; Turner, M.L.; Merino, V.F.; Yan, Y.; Kim, J.; Davis, S.L.; Komm, O.; et al. Sulforaphane exhibits antiviral activity against pandemic SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal HCoV-OC43 coronaviruses in vitro and in mice. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rajpoot, S.; Li, P.; Lavrijsen, M.; Ma, Z.; Hirani, N.; Saqib, U.; Pan, Q.; Baig, M.S. Repurposing dyphylline as a pan-coronavirus antiviral therapy. Future Med Chem 2022, 14, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, H.; Zou, P. Erythromycin Estolate Is a Potent Inhibitor Against HCoV-OC43 by Directly Inactivating the Virus Particle. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 905248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, S.; Zou, P.; Lu, L. Erythromycin Estolate Inhibits Zika Virus Infection by Blocking Viral Entry as a Viral Inactivator. Viruses 2019, 11, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Grotegut, S.; Jovanovic, P.; Gandin, V.; Olson, S.H.; Murad, R.; Beall, A.; Colayco, S.; De-Jesus, P.; Chanda, S.; et al. Inhibition of coronavirus HCoV-OC43 by targeting the eIF4F complex. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1029093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, M.; Robichaud, N.; Hulea, L.; Sonenberg, N.; Pelletier, J.; Topisirovic, I. Targeting the translation machinery in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015, 14, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).