Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Natural Conditions

2.2. The Research Site Mogot

2.3. Data Description

2.3.1. Meteorological Observations

2.3.2. Heat Dynamics in Soil

2.3.3. Landscape Surveys

- hill peaks with relatively well-drained thin mountain permafrost-taiga (partially podzolized) soils on stony eluvium occupied by sparse larch shrubs, lingonberry and lichen;

- the middle and lower steep parts of the slopes of the shadow exposure with mountain sod-taiga soils and podburs under larch forest with the Labrador tea and shrubs;

- the middle parts of the slopes of the light exposure with mountain taiga on permafrost soils under the larch forest with lingonberry (with fragments of rhododendron) and secondary birch trees;

- the lower parts of the slopes and delluvial-solifluction valleys with peat-taiga soils under sparse swampy larches with Labrador tea, blueberry and dwarf birch;

- the bottoms of valleys and floodplains of rivers with alluvial-marsh (in the lower reaches of rivers – with alluvial-layered gley) soils occupied by larch, blueberry, sphagnum and, in places, blueberry-sedge;

- large-walled falls in the upper reaches of streams with sandy loam soils under spruce forest with green moss.

2.3.4. Streamflow

2.4. Methods

2.5. Parameterization of the Hydrograph Model

2.5.1. Preparation of Input Meteorological Information

2.5.2. Parameterization of the Hydrograph Model

- The watershed divides are located at the altitudes of more than 850 m and are characterized by well-drained soils. Vegetation is represented by sparse larch. The soil layer has a capacity of 100-120 cm. The top layer consists of a dry layer of lichens with transition to loam and sandy loam.

- The shadow slopes located within the elevations of 650-850 m, have pronounced soil layer formed by forest litter. At this RFC, due to sufficient soil moisture, there grows the lushest vegetation, represented by the species of Labrador tea and cowberry larch forest. The soil organic layer thickness is more than 20 cm, the depth of the seasonal thaw depth reaches 120 cm. The steeper shadow slopes, where precipitation losses are not as high as at other RFCs, represent the main landscape producing streamflow.

- The light-exposed slopes, also located within the range of altitudes from 650 to 850 m, are characterized by higher amount of solar radiation, deeper thaw depth reaching in average 160 cm, and the least developed vegetation, consisting of the species of Labrador tea, cowberry larch forest and secondary birch forests. The thickness of the organic layer is 15-20 cm, the soil column primarily consists of sandy loam, common at depths of 40-160 cm.

- River valleys bottoms are common at the altitudes less than 650 m. They are presented by waterlogged blueberry larch forests, sphagnum moss, with some areas covered by blueberry-sedge plant complex. A distinctive feature of this complex is the presence of peat layer and thick moss cover. The thaw depths reach the lowest values compared to other RFC, namely 30-40 cm.

3. Results and Discussion

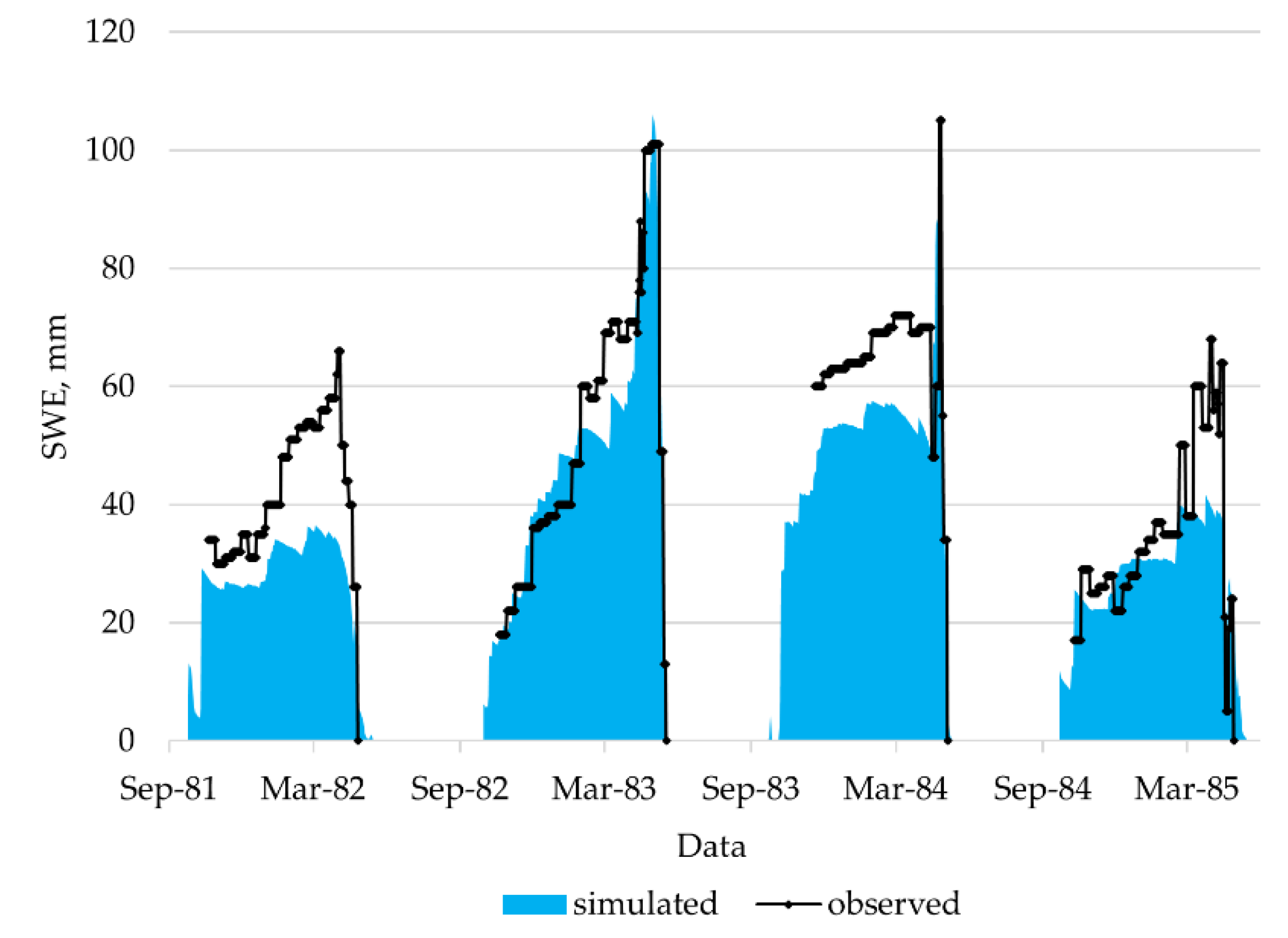

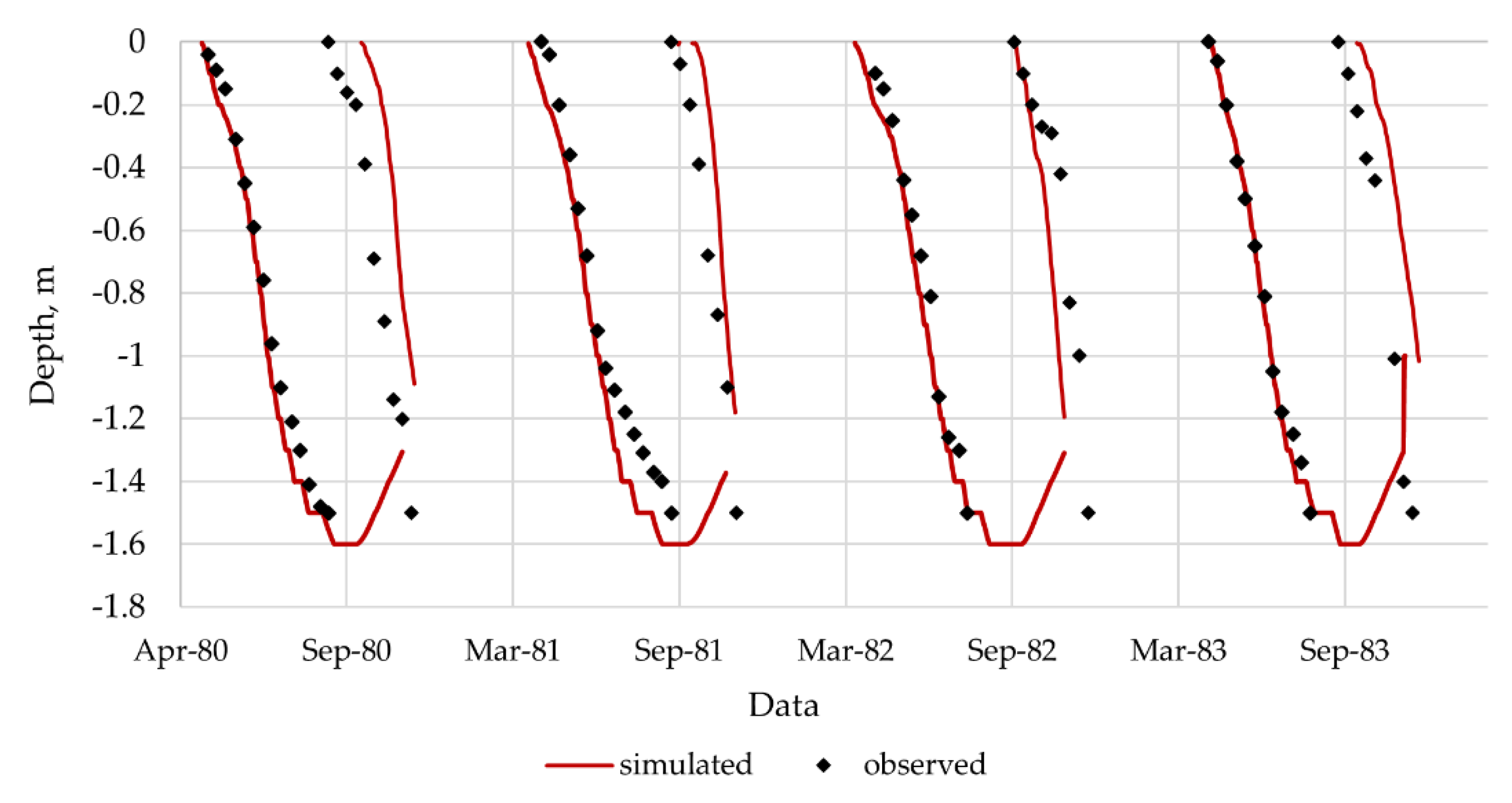

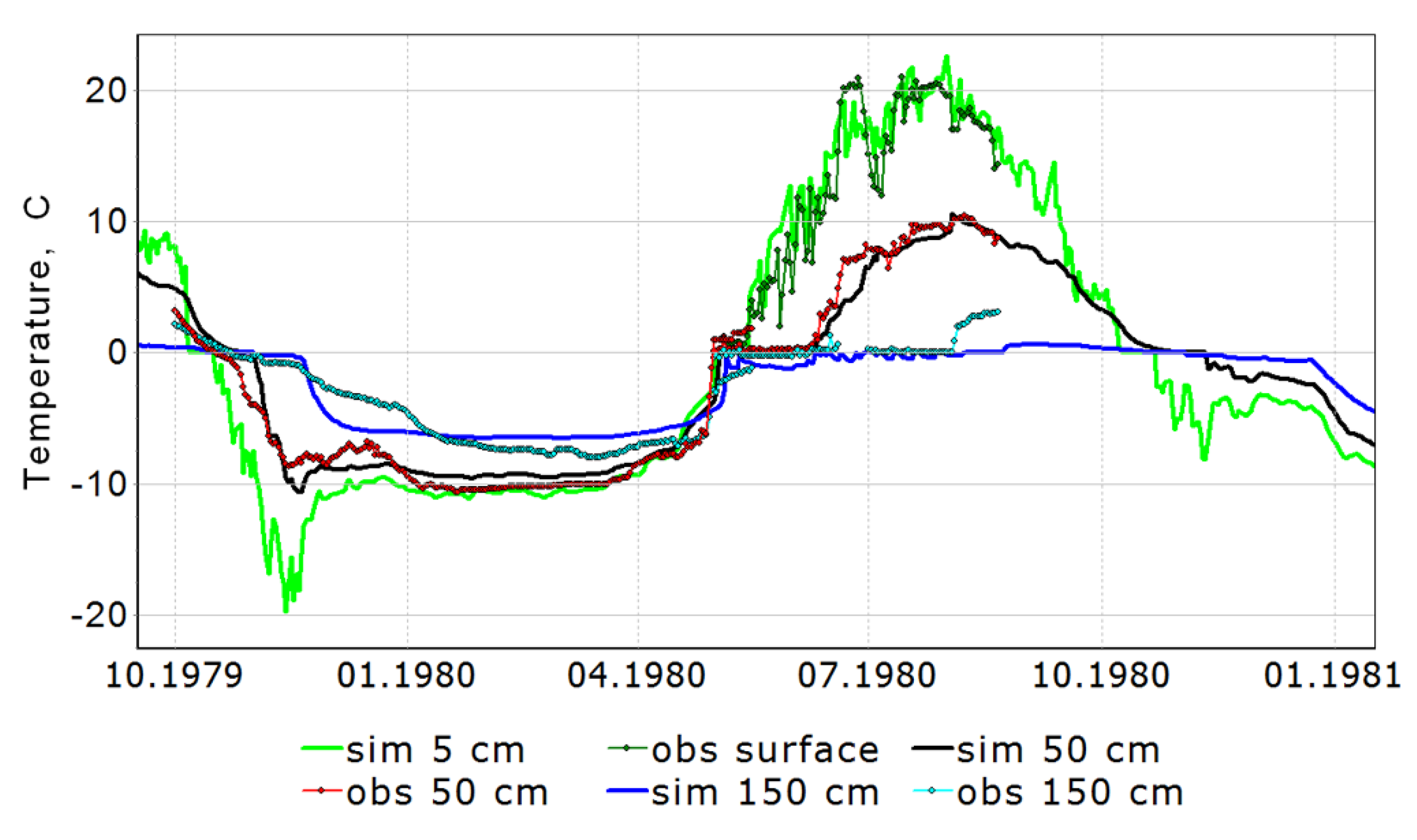

3.1. Modeling of the State Variables

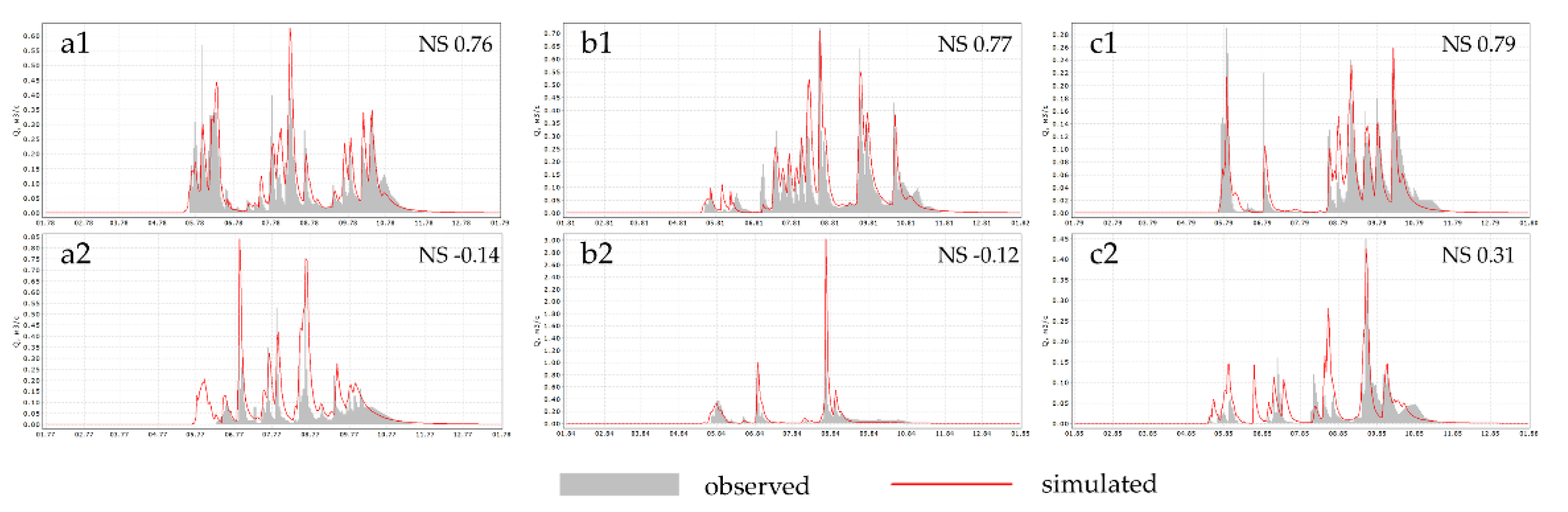

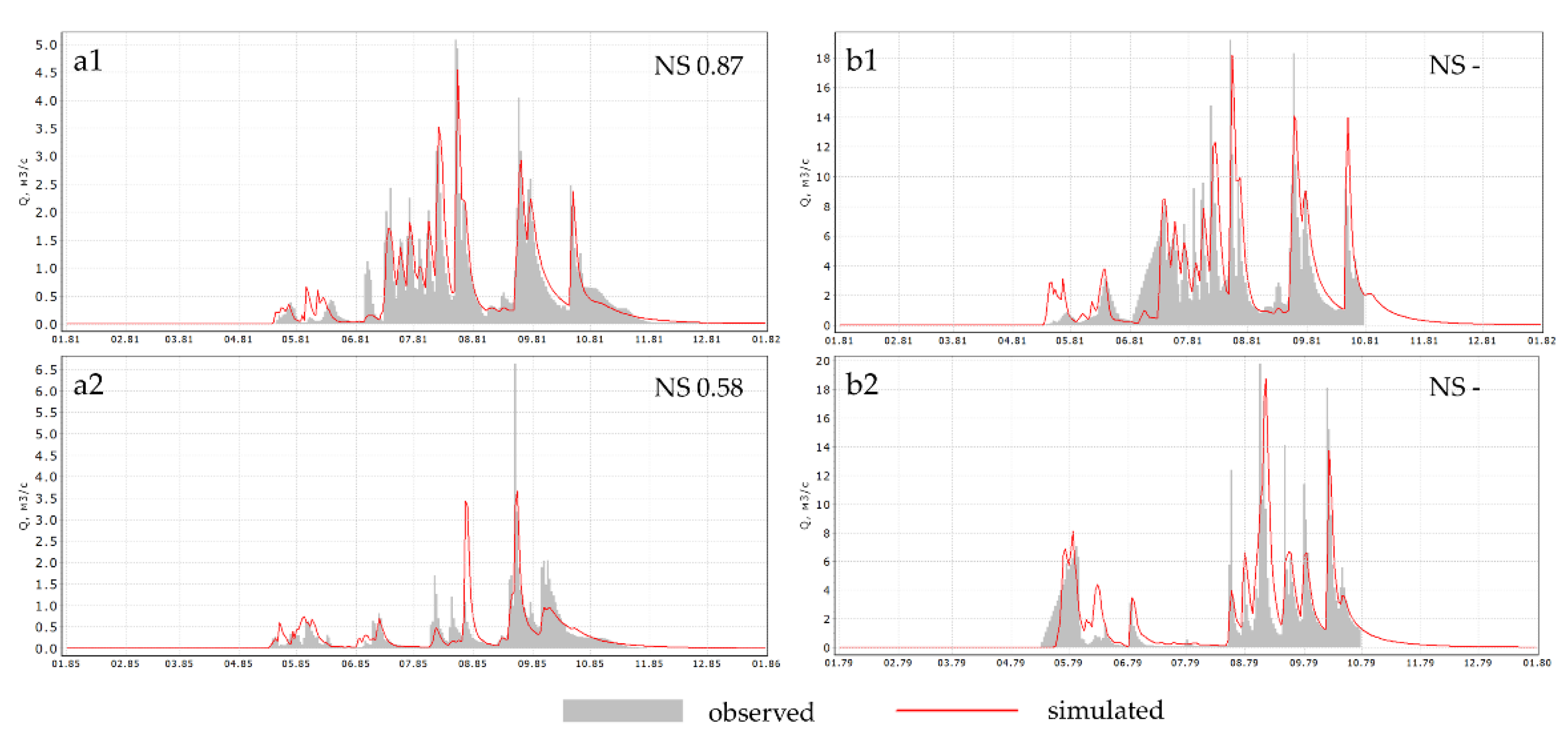

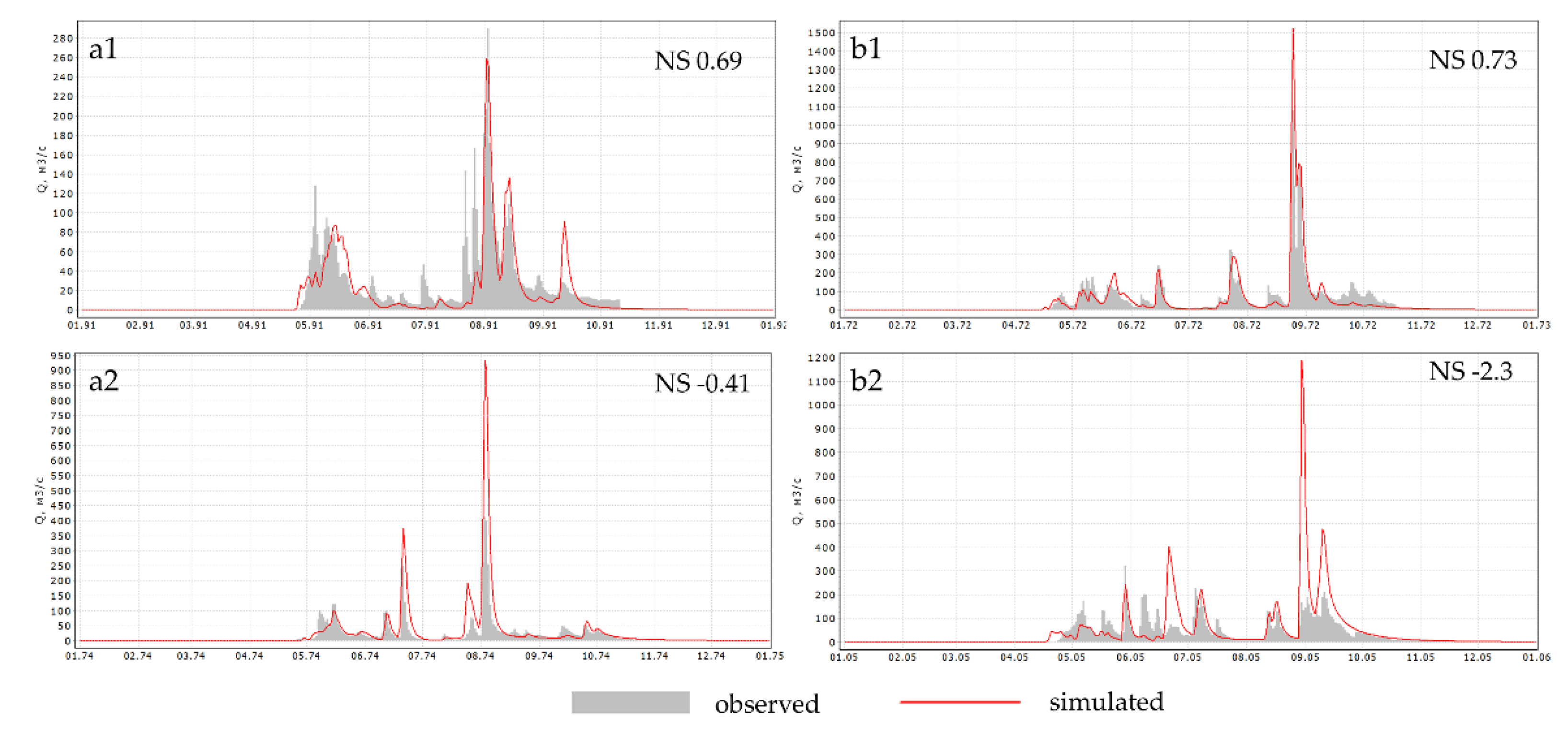

3.2. Modeling of Streamflow at Small Watersheds

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varra, G.; Della Morte, R.; Tartaglia, M.; Fiduccia, A.; Zammuto, A.; Agostino, I.; Booth, C.A.; Quinn, N.; Lamond, J.E.; Cozzolino, L. Flood. Susceptibility Assessment for Improving the Resilience Capacity of Railway Infrastructure Networks. Water 2024, 16(18), 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russian Railways. Available online: https://dvzd.rzd.ru (accessed on 11 November 2024). (in Russian).

- Streletskiy, D.; Clemens, S.; Lanckman, J.P.; Shiklomanov, N. The costs of Arctic infrastructure damages due to permafrost degradation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstyukov, A. B.; Sherstyukov, B. G. Spatial features and new trends in thermal conditions of soil and depth of its seasonal thawing in the permafrost zone. Russ. Meteorol. Hydrol. 2015, 40, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/reports/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Anisimov, O.; Streletskiy, D. Geocryological Hazards of Thawing Permafrost. Arctika XXI Century 2015, 2, 60–74. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Hjort, J.; Streletskiy, D. , Doré, G.; Wu, Q.; Bjella, K.; Luoto, M. Impacts of permafrost degradation on infrastructure. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2022, 3, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratiev V., G. The age-old, but not eternal problem of railways on permafrost. Transport of the Russian Federation. A journal about science, practice, and economics 2008, 3-4, 16-17. (In Russian).

- Kudryavtcev, S.; Valtceva, T.; Kotenko, Z.; Kazharsrki, A.; Paramonov, V.; Saharov, I.; Sokolova, N. Reinforcing a railway embankment on degrading permafrost subgrade soils. Advances in intelligent systems and computing. Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021, 1258, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walvoord, M.A.; Kurylyk, B.L. Hydrologic impacts of thawing permafrost — A Review. Vadose Zone J. 2016, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bring, A.; Fedorova, I.; Dibike, Y.; Hinzman, L.; Mård, J.; Mernild, S.H.; Prowse, T.; Semenova, O.M.; Stuefer, S.L.; Woo, M.-K. Arctic terrestrial hydrology: A synthesis of processes, regional effects, and research challenges. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2016, 121, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, W. L.; Hayashi, M.; Chasmer, L. Permafrost-thawinduced land- cover change in the Canadian subarctic: Implications for water resources. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connon R.F., Quinton W.L., Craig J. R.; Hayashi. M. Changing hydrologic connectivity due to permafrost thaw in the lower Liard River valley, NWT. Canada Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 4163–78. [CrossRef]

- Ridder, N.N.; Pitman, A.J.; Westra, S.; Ukkola, A.; Do, H.X.; Bador, M.; Hirsch, A.L.; Evans, J.P.; Di Luca, A.; Zscheischler, J. Global hotspots for the occurrence of compound events. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Ouyang, M.; Peeta, S.; He, X.; Yan, Y. Vulnerability assessment and mitigation for the Chinese railway system under floods. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 137, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermann, P.; Schöbel, A.; Kundela, G.; Thieken, A.H. Estimating flood damage to railway infrastructure—The case study of the March River flood in 2006 at the Austrian Northern Railway. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 2485–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Gao, G.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Huang, D.; Chen, D.; Li, Y. A comprehensive risk assessment of Chinese high-speed railways affected by multiple meteorological hazards. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 38, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRK.ru. Available online: https://www.irk.ru (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- David, A.; Schmalz, B. Flood hazard analysis in small catchments: Comparison of hydrological and hydrodynamic approaches by the use of direct rainfall. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.; Loukas, A.; Vasiliades, L.; Aronica, G.T. Flood inundation mapping sensitivity to riverine spatial resolution and modelling approach. Nat. Hazards 2016, 83 (Suppl. S1), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, K.; Filatova, T.; Need, A.; Bin, O. Avoiding or mitigating flooding: Bottom-up drivers of urban resilience to climate change in the USA. Global Environmental Change, 2019, 59, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocca, L.; Melone, F.; Moramarco, T. Distributed rainfall–runoff modelling for flood frequency estimation and flood forecasting. Hydrological processes 2011, 25(18), 2801–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogger, M.; Pirkl, H.; Viglione, A.; Komma, J.; Kohl, B.; Kirnbauer, R.; Merz, R.; Blöschl, G. Step changes in the flood frequency curve: Process controls. Water Resources Research 2012, 48, W05544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviroli, D.; Zappa, M.; Schwanbeck, J.; Gurtz, J.; Weingartner, R. Continuous simulation for flood estimation in ungauged mesoscale catchments of Switzerland – Part I: modelling framework and calibration results. Journal of Hydrology 2009, 377(1-2), 191-207. [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.; Babister, M.; Nathan, R.; Weeks, W.; Weinmann, E.; Retallick, M.; Testoni, I. Australian Rainfall and Runoff: A Guideto Flood Estimation, Commonwealth of Australia, Geoscience Australia, 2019.

- BAM is a project of the NKVD of the USSR. Baikal-Amur Railway. Publisher: Baikal-Amur railway, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Russia, 1945; 273 p. (in Russian)

- Vasilenko, N.G. Hydrology of the BAM Zone Rivers: Field Researchers; Nestor-Historia: SPb., Russia, 2013; 672 p. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Water resources of the rivers of the BAM zone; Hydrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1977; 272 p. (in Russian).

- Zhang, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kadota, T.; Ohata, T. Sublimation from snow surface in southern mountain taiga of eastern Siberia. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, D21103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kubota, J.; Ohata, T.; Vuglinsky, V. Influence of Snow Ablation and Frozen Ground on Spring Runoff Generation in the Mogot Experimental Watershed, Southern Mountainous Taiga of Eastern Siberia. Nordic Hydrology 2006, 37, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. Estimation of Snowmelt Infiltration into Frozen Ground and Snowmelt Runoff in the Mogot Experimental Watershed in East Siberia. International Journal of Geosciences 2013, 4, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practical recommendations for the calculation of hydrological characteristics in the zone of economic development of BAM; Hydrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1986; 180 p.

- Laperdin, V.K.; Kachura, R.A. Cryogenic hazards in the zone of linear natural and technical complexes in the south of Eastern Siberia. Cryosphere of the Earth 2009; 13(2), 27-34. (In Russian).

- Makarieva, O.; Nesterova, N.; Haghighi, A.T.; Ostashov, A.; Zemlyanskova, A. Challenges of Hydrological Engineering Design in Degrading Permafrost Environment of Russia. Energies 2022, 15, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochava, V.B.; Nedeshev, V.G. The geography of BAM. BAM: problems, prospects; Molodaya Gvardiya: Moscow, Russia, 1976; pp. 140–152. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Fotiev, S.M.; Danilova, N.S.; Sheveleva, N.S. Geocryological conditions of the Middle Siberia; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1974; 148 p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Makarieva, O. , Nesterova, N., Lebedeva, L., Sushansky, S. Water balance and hydrology research in a mountainous permafrost watershed in upland streams of the Kolyma River, Russia: a database from the Kolyma Water-Balance Station, 1948–1997. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 689–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, Y. B. , Semenova (Makarieva), O. M.; Vinogradova, T. A. An approach to the scaling problem in hydrological modelling: the deterministic modelling hydrological system. Hydrological Processes 2011, 25, 1055–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, O.; Lebedeva, L.; Vinogradov, Yu. Simulation of subsurface heat and water dynamics, and runoff generation in mountainous permafrost conditions, in the Upper Kolyma River basin, Russia. Hydrogeology Journal 2013, 21(1), 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva, L.; Semenova (Makarieva), O.; Vinogradova, T. Simulation of Active Layer Dynamics, Upper Kolyma, Russia, using the Hydrograph Hydrological Model. Permafrost and Periglac. Process. 2014, 25(4), 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, J.; Brown, T.; Fang, X.; Shook, K.R.; Pradhananga, D.; Armstrong, R.; Harder, Ph.; Marsh, C.; Costa, D.; Krogh, S.; Aubry-Wake, C.; Annand, H.; Lawford, P.; He, Z.; Kompanizare, M.; Moreno, J.I. The Cold Regions Hydrological Modelling Platform for hydrological diagnosis and prediction based on process understanding. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 615, 128711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Shook, K.; Spence, C.; Pomeroy, J.; Whitfield, C. Modelling the regional sensitivity of snowmelt, soil moisture, and streamflow generation to climate over the Canadian Prairies using a basin classification approach. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2023, 27, 3525–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xia, J.; She, D.; Jing, Z.; Hong, S.; Song, Z.; Wang, G. Parameter Regionalization With Donor Catchment Clustering Improves Urban Flood Modeling in Ungauged Urban Catchments. Water Resources Research 2024, 60, e2023WR035071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D,; Choi, Y. H.; Kim, J. Multiobjective Automatic Parameter Calibration of a Hydrological Model. Water 2017, 9(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, A.; Elshorbagy, A. Automatic Calibration of Hydrological Models in the Newly Reconstructed Catchments: Issues, Methods and Uncertainties. EGUGeneral Assembly 2010, 12, EGU2010–2253-1. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, F.; Sylvain, J.-D.; Drolet, G.; Poulin, A.; Arsenault, R. Enhancing physically based and distributed hydrological model calibration through internal state variable constraints. EGUsphere 2024, 2024-3353. (preprint). [CrossRef]

- Smit, E.; Zijl, G.M.; Riddell, E.; Van Tol, J.J. Model calibration using hydropedological insights to improve the simulation of internal hydrological processes using SWAT+. Hydrological Processes 2024, 38(5), e15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, Yu. B. , Vinogradova, T. A. Mathematical modeling in hydrology; Akademiya: Moscow, Russia, 2010; 304 p. [Google Scholar]

- Nesterova, N.; Makarieva, O.; Post, D. A. Parameterizing a hydrological model using a short-term observational dataset to study runoff generation processes and reproduce recent trends in streamflow at a remote mountainous permafrost basin. Hydrological Processes 2021, 35(7), e14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, M.; Hrachowitz, M.; Savenije, H. H. G.; Mariéthoz, G.; Schaefli, B. Improving the Predictive Skill of a Distributed Hydrological Model by Calibration on Spatial Patterns With Multiple Satellite Data Sets. Water Resources Research 2020, 56, e2019WR026085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, K.; Ferreira, V. G.; Bai, P. Hydrologic Model Calibration With Remote Sensing Data Products in Global Large Basins. Water Resources Research 2022, 58, e2022WR032929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Mai, J.; Do, H. X.; Gronewold, A.; Reeves, H.; Eberts, S.; Niswonger, R.; Regan, R. S.; Hunt, R. J. Can Hydrological Models Benefit From Using Global Soil Moisture, Evapotranspiration, and Runoff Products as Calibration Targets? Water Resources Research 2023, 59, e2022WR032064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Parajka, J.; Széles, B.; Greimeister-Pfeil, I.; Vreugdenhil, M.; Komma, J.; Valent, P.; Blöschl, G. The value of satellite soil moisture and snow cover data for the transfer of hydrological model parameters to ungauged sites. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2022, 26, 1779–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Kumar, D. N. Optimizing parameter estimation in hydrological models with convolutional neural network guided dynamically dimensioned search approach. Advances in Water Resources 2024, 194, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudunuru, M.; Son, K.; Jiang, P.; Hammond, G.; Chen, X. Scalable deep learning for watershed model calibration. Frontiers in Earth Science 2022, 10, 1026479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Archfield, S.; Wagener, T. Transferring rainfall runoff model parameters to ungauged catchments: Does the metric by which hydrologic similarity is defined actually matter? EGUGeneral Assembly 2012, 14, EGU2012–13910. [Google Scholar]

- Feigl, M.; Thober, S.; Schweppe, R.; Herrnegger, M.; Samaniego, L.; Schulz, K. Automatic regionalization of model parameters for hydrological models. Water Resources Research 2022, 58(12), e2022WR031966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xia, J.; She, D.; Jing, Z.; Hong, S.; Song, Z.; Wang, G. Parameter Regionalization With Donor Catchment Clustering Improves Urban Flood Modeling in Ungauged Urban Catchments. Water Resources Research 2024, 60, (7), e2023WR035071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gauge | Catchment area, km2 | The average height of the catchment area, m | Length of the riverbed network, km | Average catchment slope, º/˚˚ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Onyx stream | 3.0 | 780 | 2.0 | 190 |

| The Filiper stream | 4.7 | 710 | 5.1 | 147 |

| The Zakharyonok stream | 5.8 | 700 | 4.2 | 171 |

| The Nelka River | 30.8 | 850 | 27.0 | 170 |

| Soil parameters | The method of determining the parameter | Lichens | Plant litter | Moss | Light loam | Sandy loam | Peat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density, kg/m3 | field | 1680 | 1300 | 520 | 2600 | 2600 | 1700 |

| Porosity, m3/ m3 | field | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.83 |

| Maximum water holding capacity, m3/ m3 | field | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.40 |

| Filtration coefficient, mm/min | field | 24 | 12 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| Heat capacity, J /(kgºC) | assessment by soil type | 780 | 840 | 1930 | 830 | 830 | 1930 |

| Heat conductivity, W/(mºC) | assessment by soil type | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Hydraulic parameter, m3/s | expert assessment, calibration |

The active layer Top organic layer: 10 Lower mineral layer: 0.005 |

|||||

| Gauges | Period | Yo | Ys | P | E | Qo | Qs | NS (m/av) |

NS (max, гoд) |

NS (min, гoд) |

| Onyx stream | 1976-1985 | 243 | 342 | 607 | 259 | 0.66 | 1.20 | 0.65/0.64 | 0.79(1979) | 0.31(1985) |

| Filiper stream | 1976-1985 | 255 | 346 | 634 | 285 | 1.37 | 3.02 | 0.55/0.40 | 0.77(1981) | -0.12(1984) |

| Zakharyonok stream | 1976-1985 | 216 | 363 | 628 | 260 | 1.51 | 2.88 | 0.35/0.26 | 0.76(1978) | -0.14(1977) |

| Nelka River | 1976-1985 | 295 | 323 | 658 | 327 | 9.73 | 15.2 | 0.71/0.70 | 0.87(1981) | 0.58(1985) |

| Tsyganka River | 1976-1985 | - | 308 | 617 | 306 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unakha River - Unakha | 1966-1994 | 327 | 342 | 640 | 300 | 875 | 456 | 0.46/ 0.40 | 0.69(1991) | -0.41(1974) |

| Tynda River - Tynda | 1966-2012 | 286 | 293 | 645 | 354 | 1450 | 2500 | 0.52/0.31 | 0.73(1972) | -2.3(2005) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).