1. Introduction

In many commercial formulations of emulsions and suspensions, high molecular weight polymers are often added, although the reasons for adding the polymers vary from one application to another [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

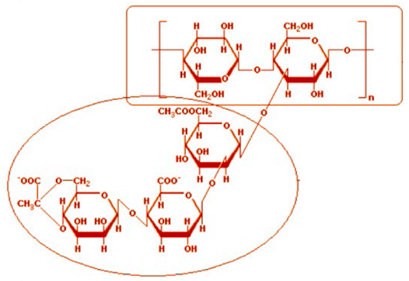

6]. In many applications, polymers are used as thickeners to modify the rheology of the continuous phase and to impart high viscosity and yield value on that phase. The thickening effect causes the emulsion droplets or solid particles of suspensions to remain suspended in the continuous medium, and thus sedimentation/creaming of emulsions and suspensions is eliminated and the shelf life of the product is extended. In food emulsions and suspensions, there is an additional purpose for adding polymeric thickeners (mainly polysaccharides) to the continuous phase and that is to impart the required mouth-feel properties, pleasing appearance, and texture to the food products and to improve their moisture retention. Some examples of polymeric thickening agents used widely in emulsion and suspension formulations are sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), hydroxyethyl cellulose, xanthan gum, guar gum, gum tragacanth, gum karaya, gum Arabic, locust bean gum, and polyacrylamides. The rheology and thickening effect of polymeric agents is well studied in the literature [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Recently, nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) has gained significant attention as a rheology modifier and thickening agent due to its surface charge and high aspect ratio. Nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) in the form of cellulose nanocrystals is a versatile cost-effective nanomaterial [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. It is derived from cellulose, the most abundant organic polymer on earth sourced from wood, cotton, and agricultural residues. NCC is often produced through acid hydrolysis of cellulose fibers in the form of rod-shaped nanocrystals with diameters typically ranging from a few nanometers to 100 nm and lengths up to several hundred nanometers. The nanocrystals of NCC exhibit a highly crystalline structure with glucose units aligned parallel along their longitudinal axis. Consequently, NCC exhibits exceptional mechanical properties such as high tensile strength and stiffness. Due to its biodegradability and biocompatibility, NCC is an environmentally friendly alternative compared with petroleum-based materials. Furthermore, it is a sustainable material derived from renewable resources. Also, the surface chemistry of NCC allows for facile functionalization. Different functional groups could be attached to the surface of nanocrystals to tailor their properties for specific applications. This versatility extends their applicability to many industrial applications. The rheology and thickening effect of NCC is well studied in the literature [

32,

33,

36].

The broad objective of this work was to investigate the interactions between polymers and NCC with the goal to develop novel hybrid NCC-polymer thickeners and rheology modifiers. To that end, the rheology of mixtures of NCC and polymer was investigated over a broad range of concentrations of NCC and polymer. To our knowledge, this is the first study where the interactions between NCC and polymers are investigated and the corresponding thickening effect established using rheology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

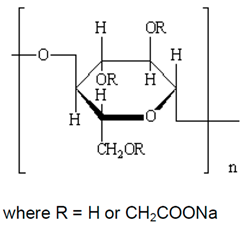

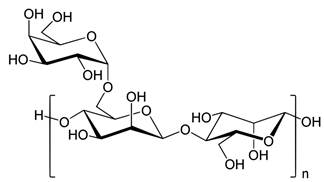

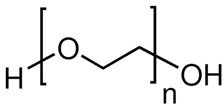

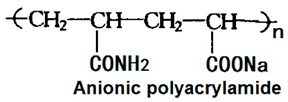

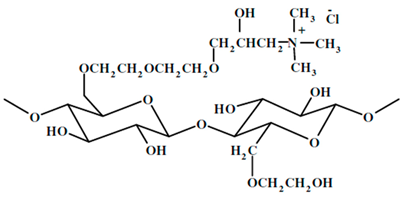

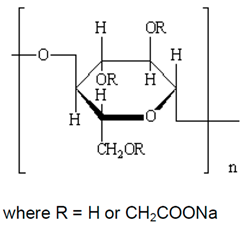

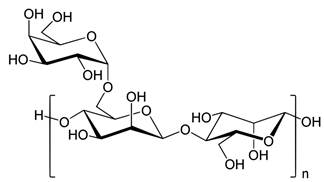

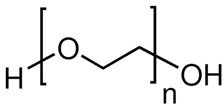

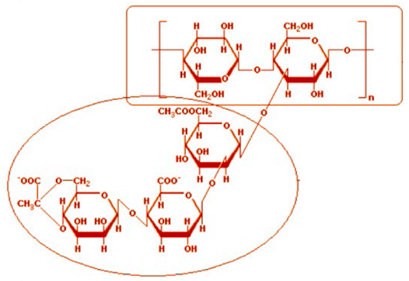

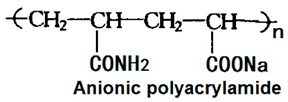

Six different polymers, three anionic (CMC, polyacrylamide, xanthan gum), two non-ionic (guar gum, polyethylene oxide), and one cationic (quaternary ammonium salt of hydroxyethyl cellulose) were investigated.

Table 1 lists the polymers investigated. The chemical structure and uses of polymers are also summarized in the table.

NCC, was supplied by CelluForce Inc., Windsor, On, Canada, under the trade name of NCC NCV100-NASD90. The nanocrystals were manufactured using sulfuric acid hydrolysis of wood pulp.

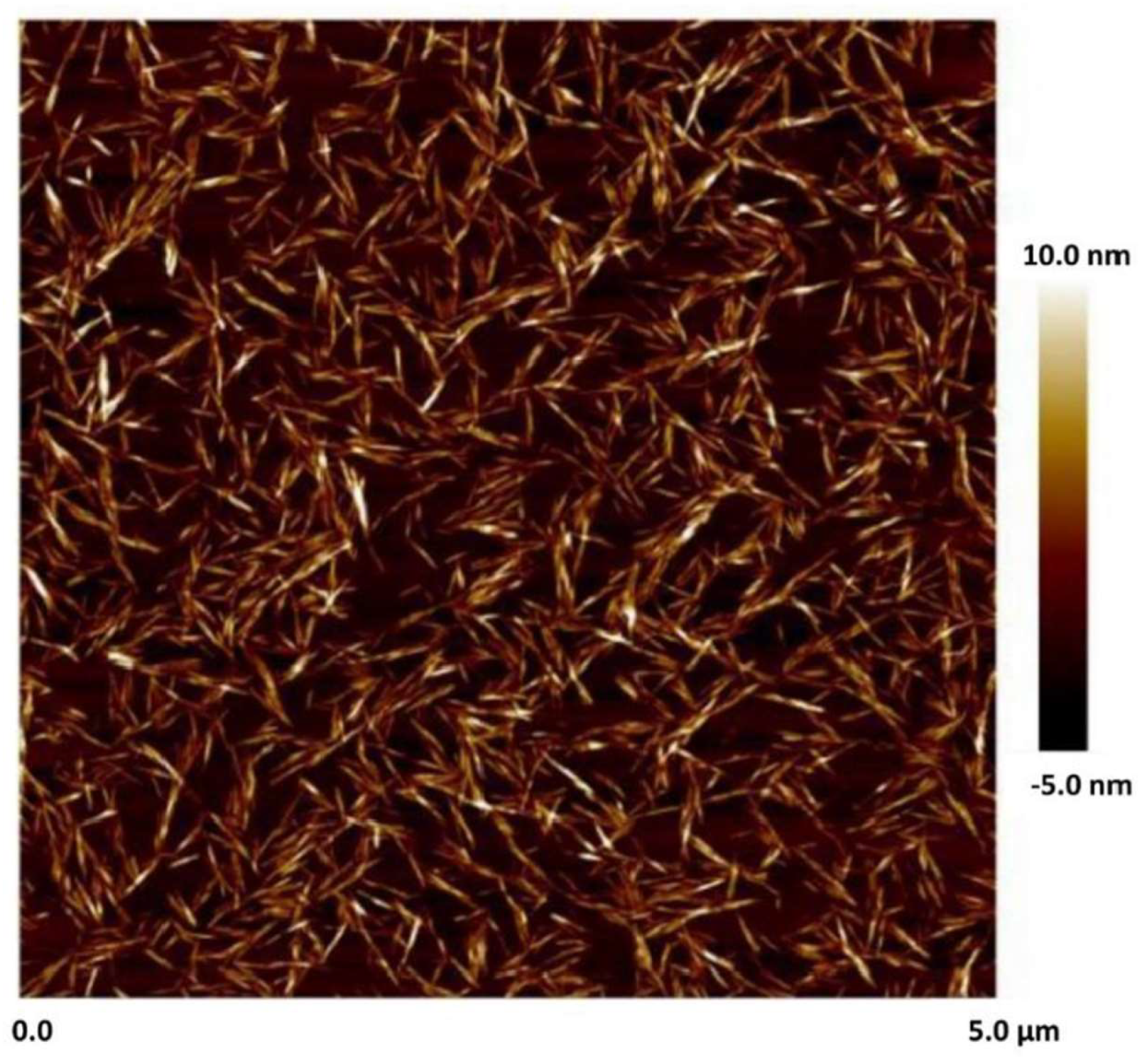

Figure 1 shows the atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of cellulose nanocrystals. Clearly, nanocrystals are rod shaped particles. The mean length and width of nanocrystals are 76 nm and 3-4 nm, respectively [

32].

2.2. Preparation of Polymer Solutions

Solutions of polymer were prepared in batches of approximately 1 kg at room temperature () by adding a known amount of polymer to a known amount of de-ionized water. Gentle mixing of the solution was maintained during the addition of polymer using the homogenizer. The solution was finally homogenized in the homogenizer at a high speed for a fixed duration. The speed and duration of mixing varied with the concentration of the polymer. Each polymer solution at different concentrations was prepared freshly. The solution was left unstirred at room temperature for at least three hours before any measurements were made to eliminate any air entrapped during mixing and to cool down the sample to room temperature.

2.3. Preparation of Mixtures of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Polymer Solutions

The mixtures of NCC and polymer solutions were prepared in batches of approximately 1 kg at room temperature () by slowly dispersing a known amount of NCC into a known amount of polymer solution. The mixing of the mixture was maintained using a turbine homogenizer (Gifford-Wood, model 1L) at a fixed speed. The mixture was homogenized until the nanocrystals were dispersed and homogenized completely. To increase the NCC concentration of the mixture, the required amount of more NCC was added slowly to the known amount of an existing lower NCC concentration mixture and the mixture was homogenized at a high speed for a fixed duration. The speed and duration of mixing varied with the concentrations of NCC and polymer. The solution was left unstirred at room temperature for at least three hours before any measurements were made to eliminate any air entrapped during mixing and to cool down the sample to room temperature.

2.4. Measurements

Two Fann co-axial cylinder viscometers with different torsion spring constants and a Haake co-axial cylinder viscometer with three different bobs (inner cylinders) were used to measure the rheological properties. It was necessary to use different devices (Fann and Haake) and bobs to cover a broad range of viscosities exhibited by the fluids.

Table 2 gives the relevant dimensions of the viscometers used in this work. In the Fann viscometer, the inner cylinder is kept stationary, and the outer cylinder is rotated. However, in the Haake viscometer, the inner cylinder is rotated, and outer cylinder is kept stationary. The rotational speed varied from 0.9 to 600 rpm in the Fann viscometer and from 0.01 to 512 rpm in the Haake viscometer. The viscometers were calibrated using viscosity standards of known viscosities. All the viscosity measurements were carried out at room temperature

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

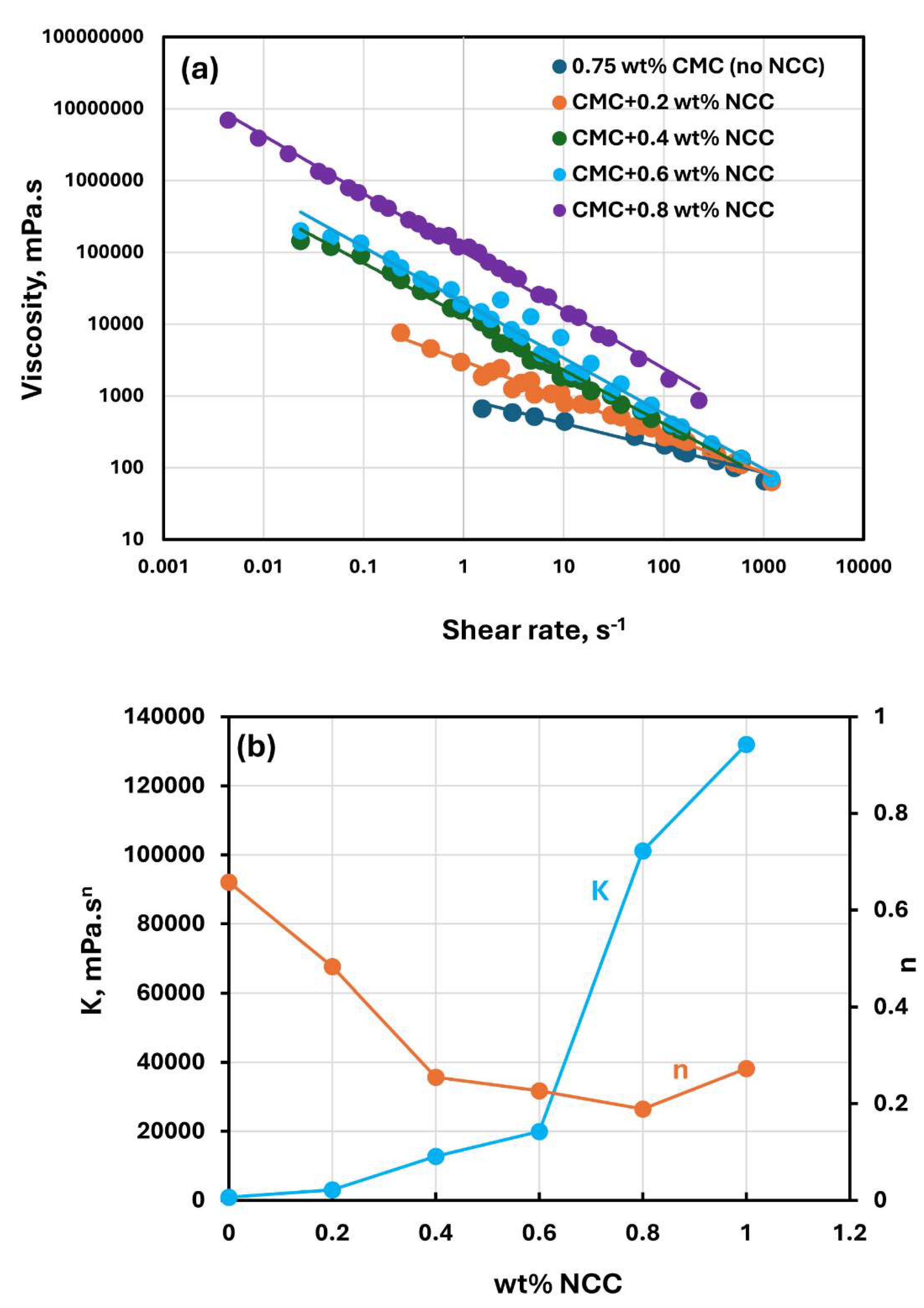

3.1. Rheology of CMC Polymer Solutions and NCC- CMC Mixtures

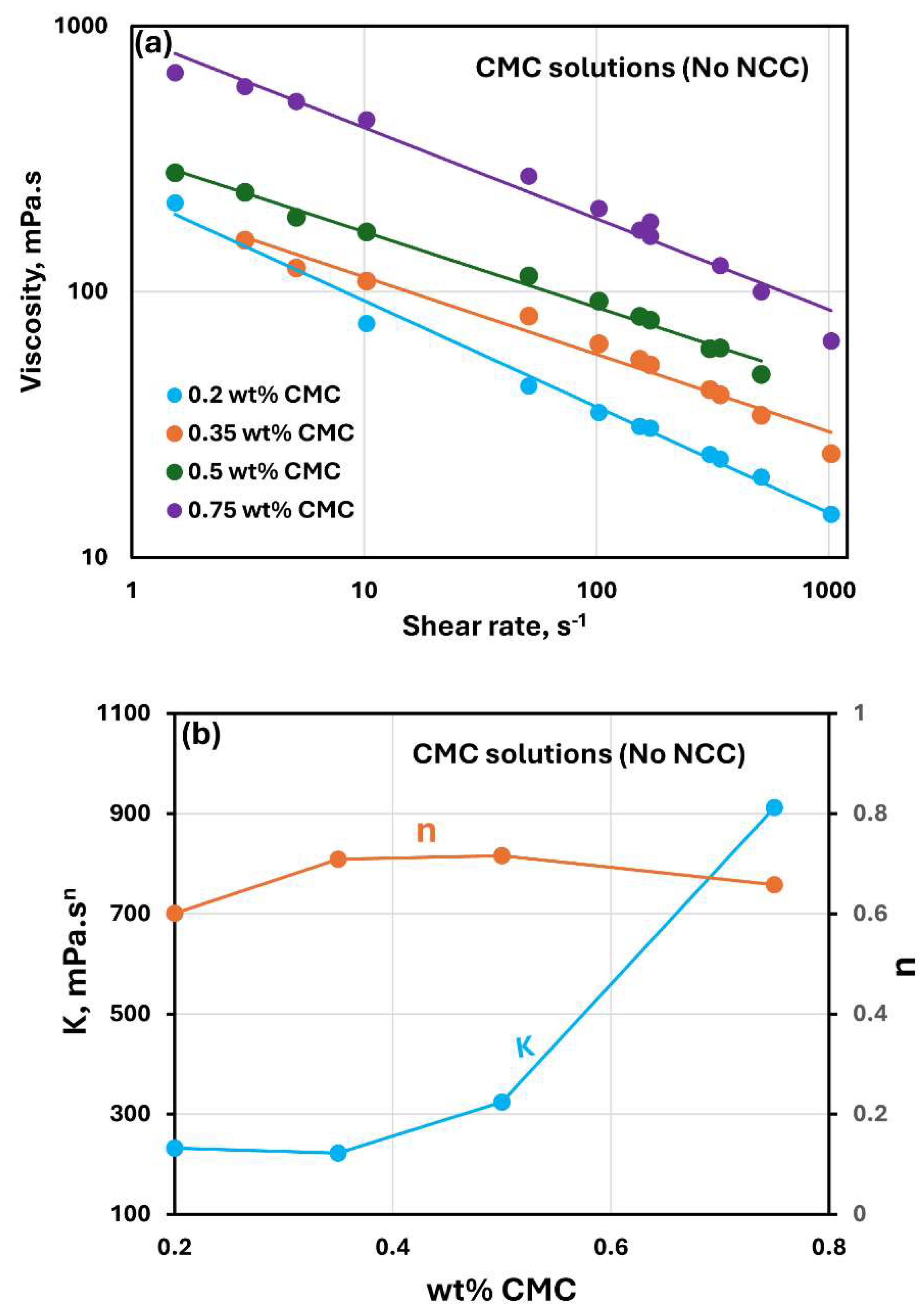

Figure 2 shows the rheological data for CMC polymer solutions without any NCC addition. The polymer solutions are non-Newtonian shear-thinning, that is, the viscosity decreases with the increase in the shear rate. The shear-thinning behaviour of polymer solutions is due to stretching and alignment of polymer molecules with shear in the direction of flow. Viscosity versus shear rate data for polymer solutions follow a linear relationship, see

Figure 2(a), indicating power-law behavior. The power-law model is given as:

where

is shear stress,

is shear rate,

is consistency index, and

is flow behavior index.

Figure 2(b) shows the variations of power-law constants (

) of polymer solutions with CMC concentration. The consistency index

increases with the increase in CMC concentration especially at high concentrations. The flow behavior index

is less than one as expected for a shear-thinning fluid. It varies only marginally with the increase in CMC concentration.

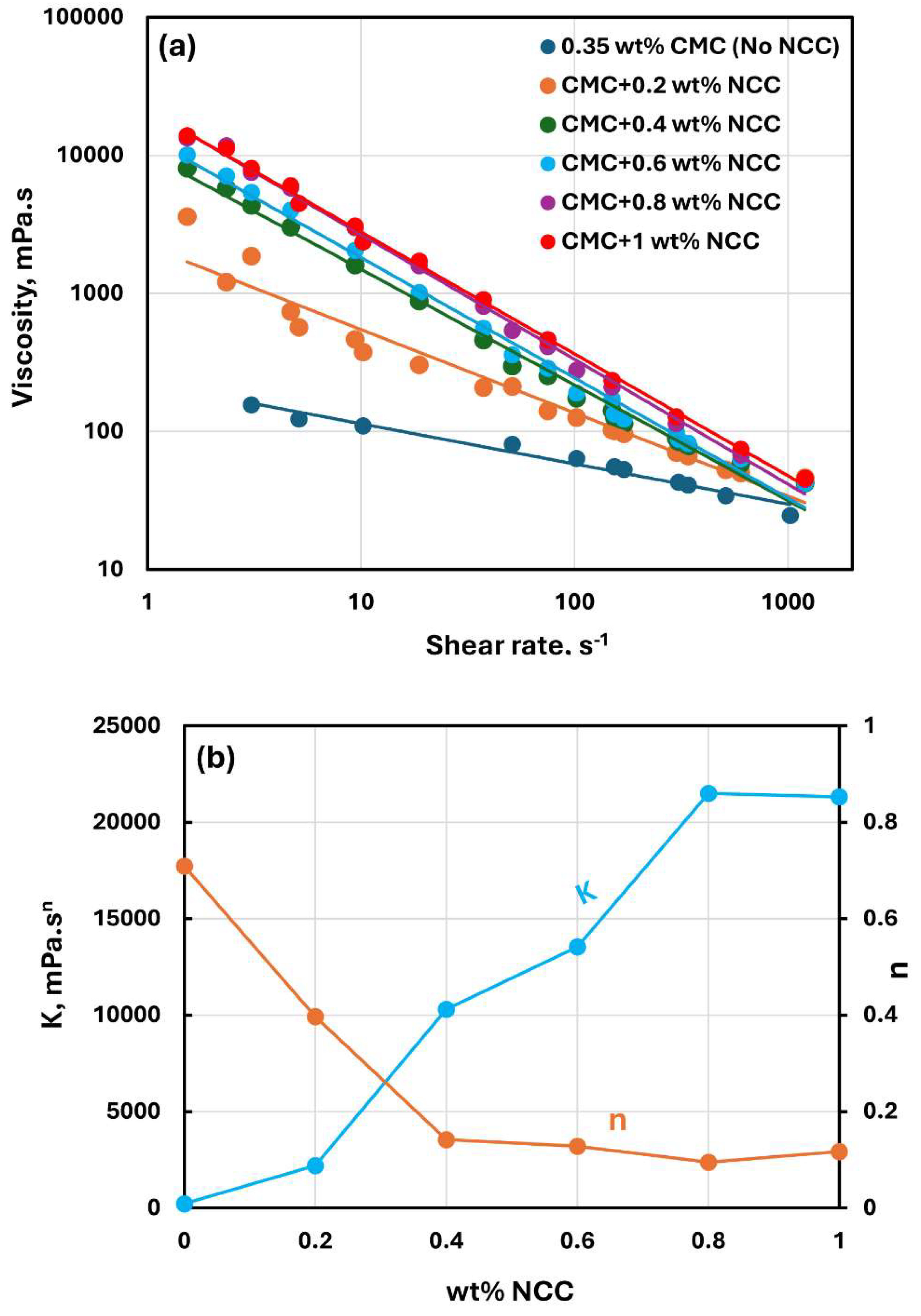

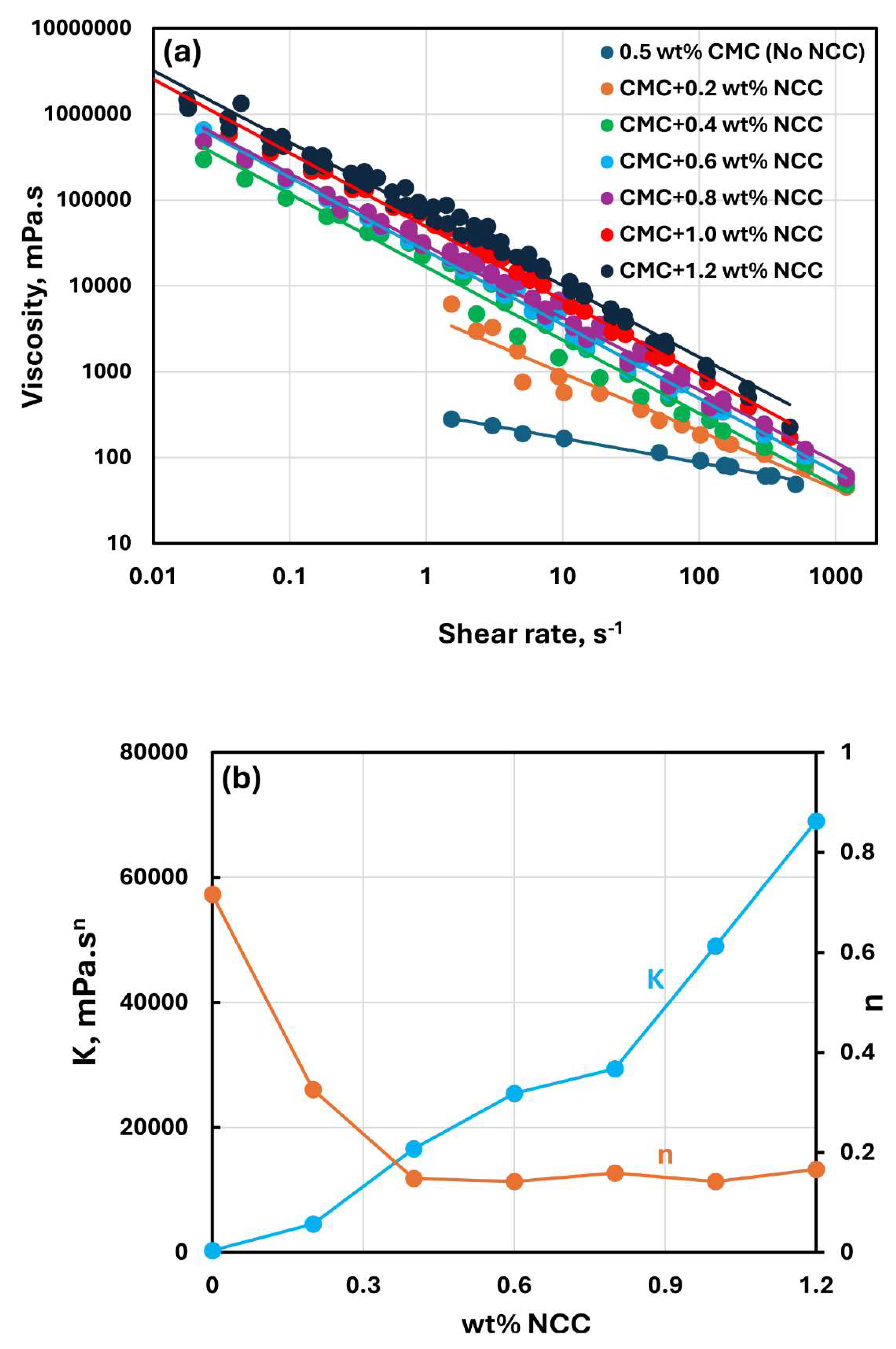

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the rheological behavior of mixtures of NCC and CMC polymer solutions. The NCC concentration varies from 0 to as high as 1.2 wt% in increments of 0.2 wt%. The flow curves (viscosity versus shear rate plots) for NCC-CMC mixtures can be described well by the power law model, Equation (2). The addition of NCC to CMC solution has a strong influence on the consistency and flow behavior of the system as reflected in the power law parameters:

and

. At a given CMC concentration, the consistency index

increases sharply whereas the flow behavior index

decreases sharply with the increase in NCC concentration. Thus, the addition of cellulose nanocrystals to CMC polymer solution makes the system more viscous and shear-thinning.

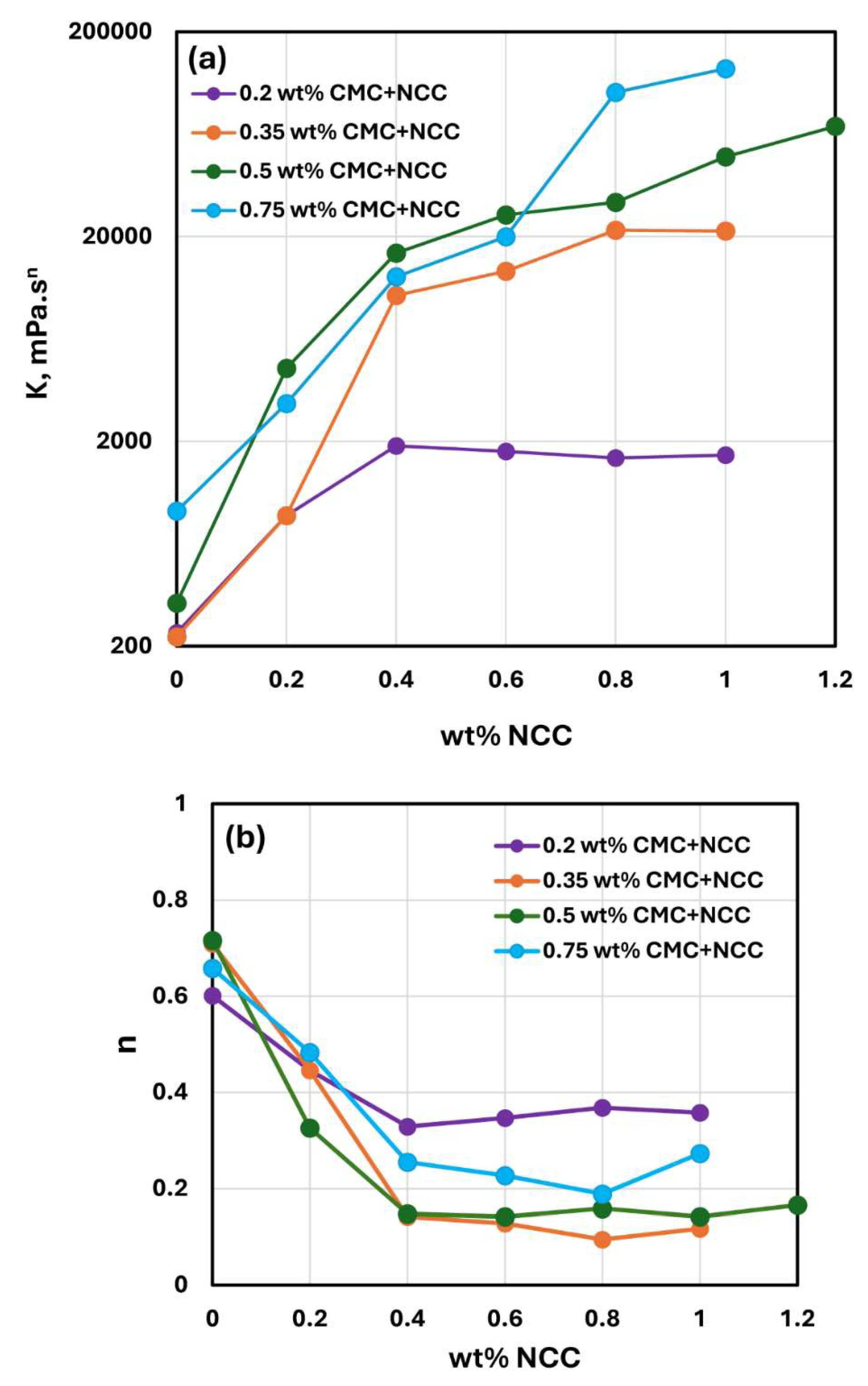

Figure 6 compares the consistency index

and flow behavior index

values for NCC-CMC mixtures with different concentrations of CMC. With the increase in CMC polymer concentration, the consistency index

generally increases at any given NCC concentration, especially at high NCC concentrations. No clear trend is observed in the flow behavior index

with the increase in CMC concentration.

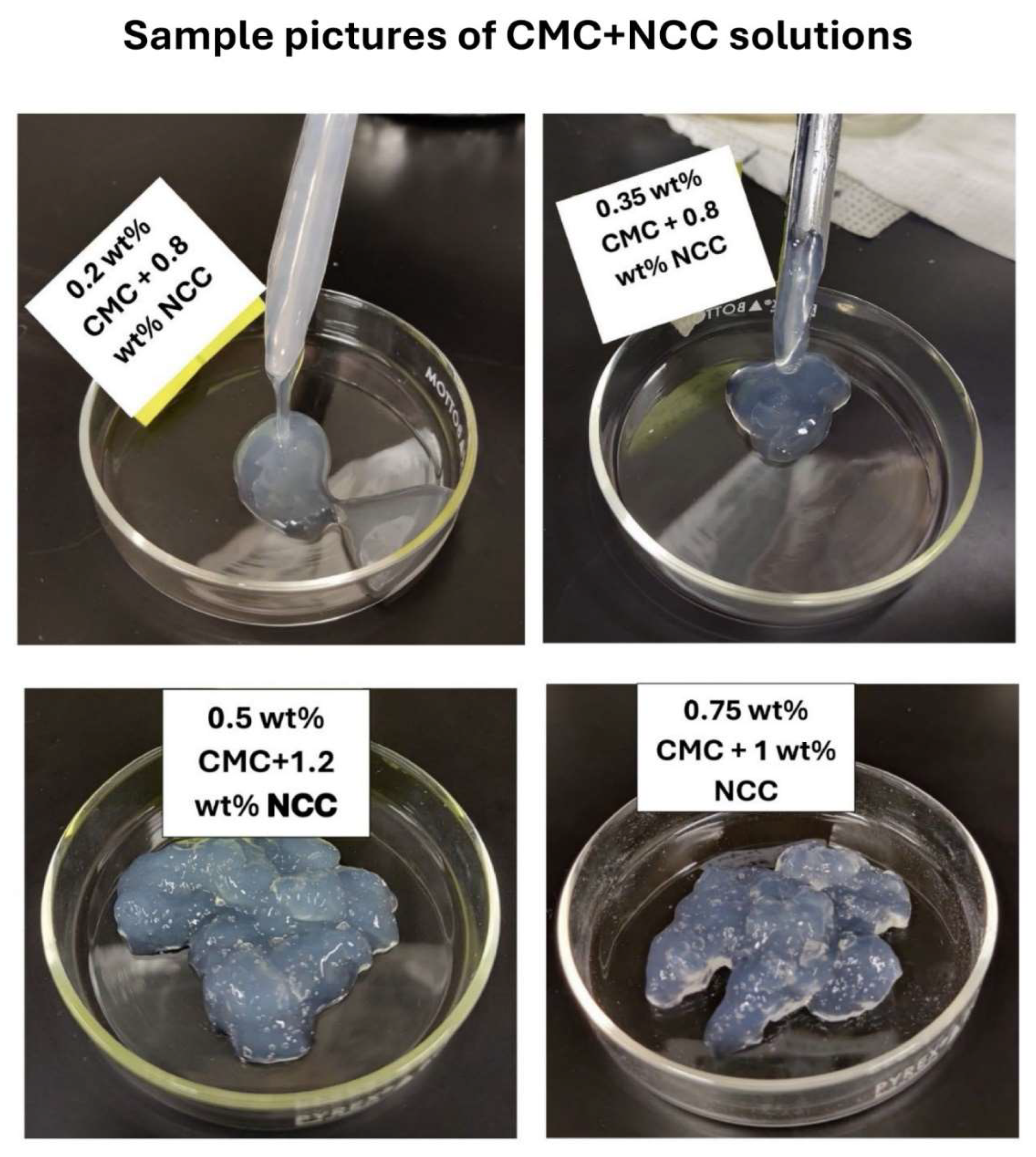

Figure 7 shows the images of the samples of NCC-CMC mixtures. The mixture is fluidic at low CMC and NCC concentrations. The mixture appears as a gel at high CMC and NCC concentrations.

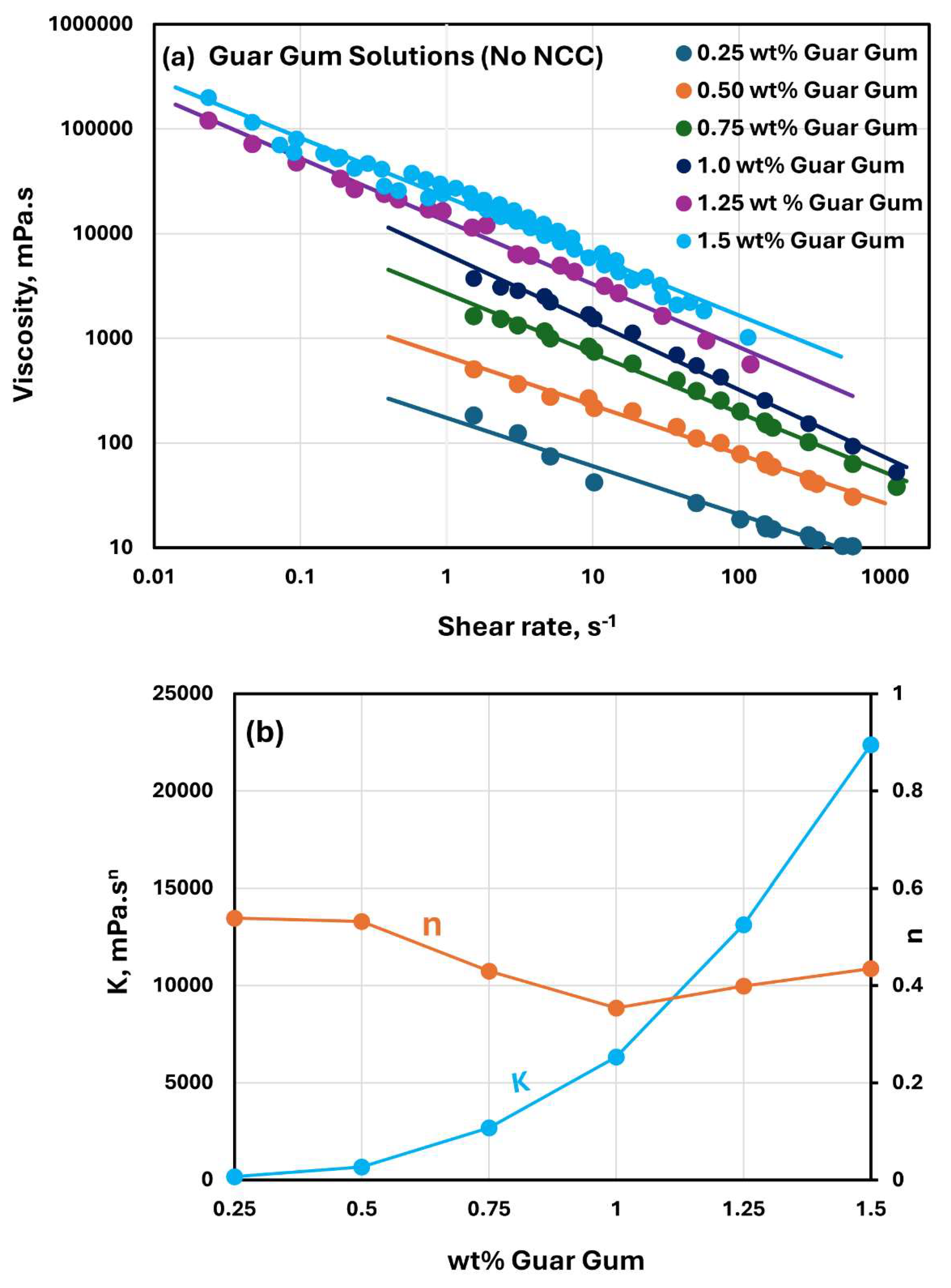

3.2. Rheology of Guar Gum Solutions and NCC-Guar Gum Mixtures

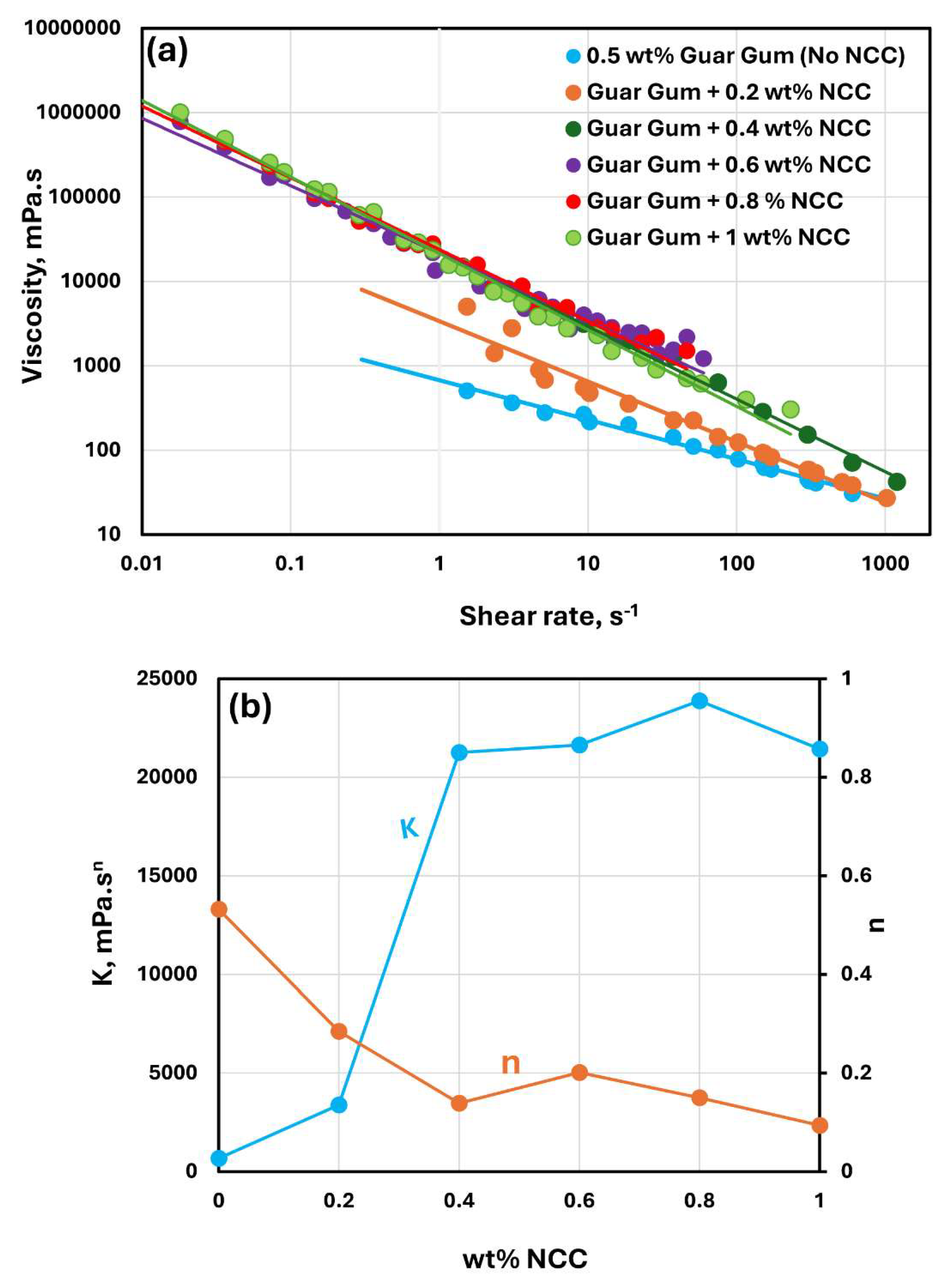

The rheological behavior of guar gum solutions without any NCC addition is shown in

Figure 8. The guar gum solutions are highly shear-thinning, and they follow the power-law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

increases with the increase in guar gum concentration. The flow behavior index

is in the range of 0.35-0.54 over the guar gum concentration investigated. A relatively low value of

is indicative of a high degree of shear-thinning in guar gum solutions.

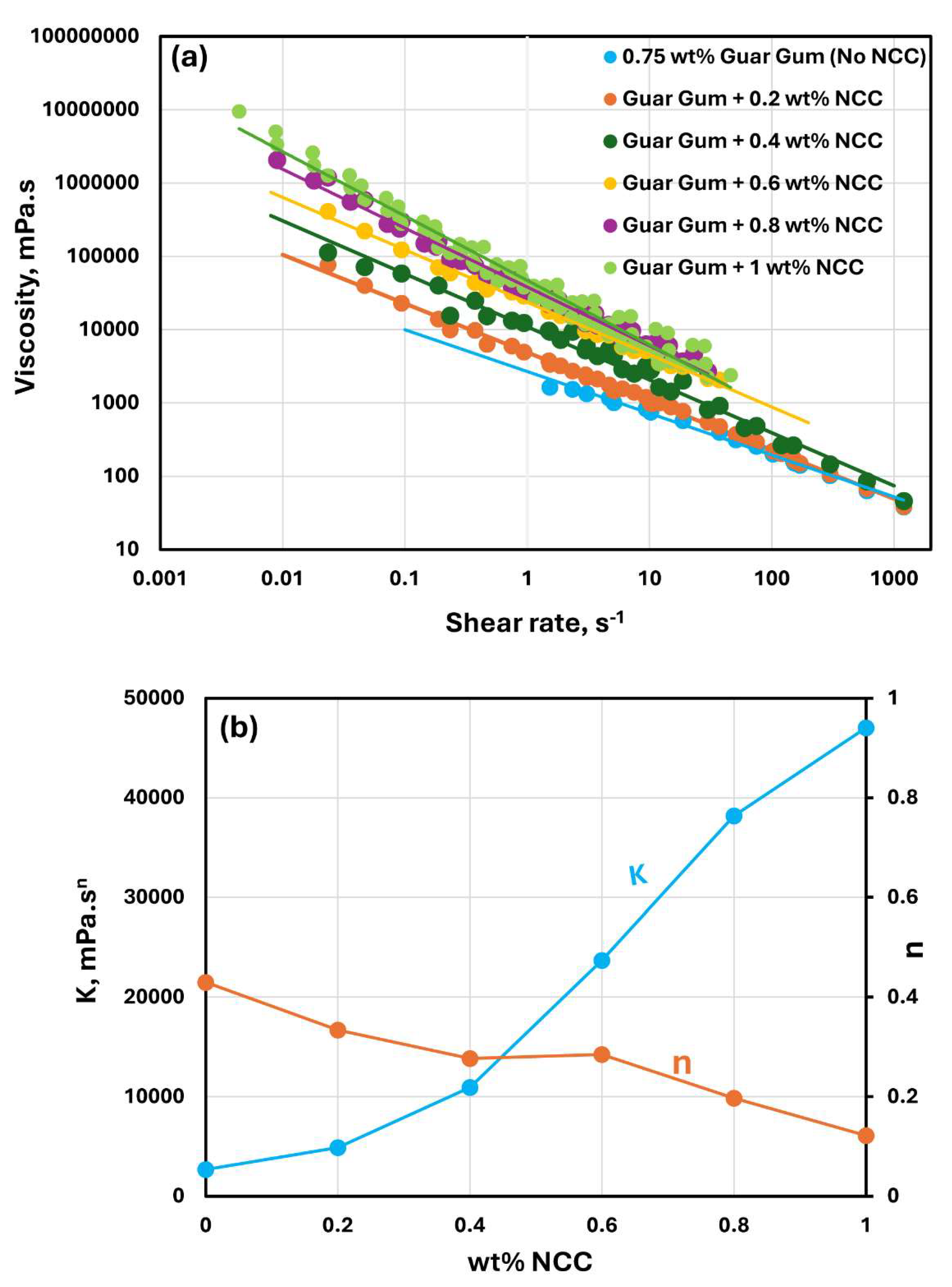

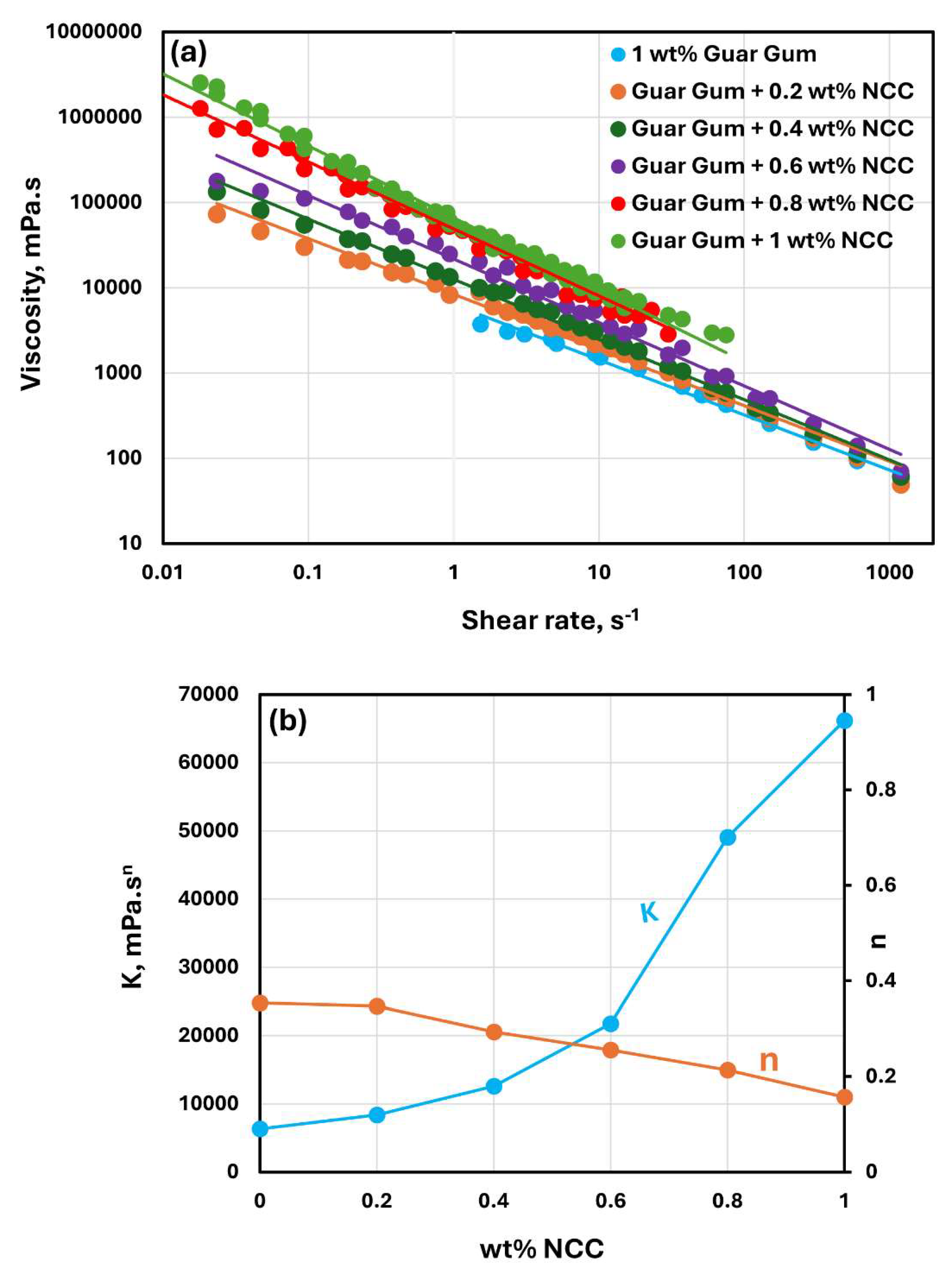

The rheological behavior of mixtures of NCC and guar gum solution are shown in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. The NCC concentration varies from 0 to 1.0 wt% in increments of 0.2 wt%. The mixtures of NCC and guar gum solution are highly shear-thinning. The viscosity versus shear rate data for NCC-Guar Gum mixtures can be described well by the power law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

increases sharply and the flow behavior index

decreases with the increase in NCC concentration at any given guar gum concentration. Thus, the mixture of NCC and guar gum solution becomes more viscous and shear-thinning with the addition of cellulose nanocrystals to the guar gum solution.

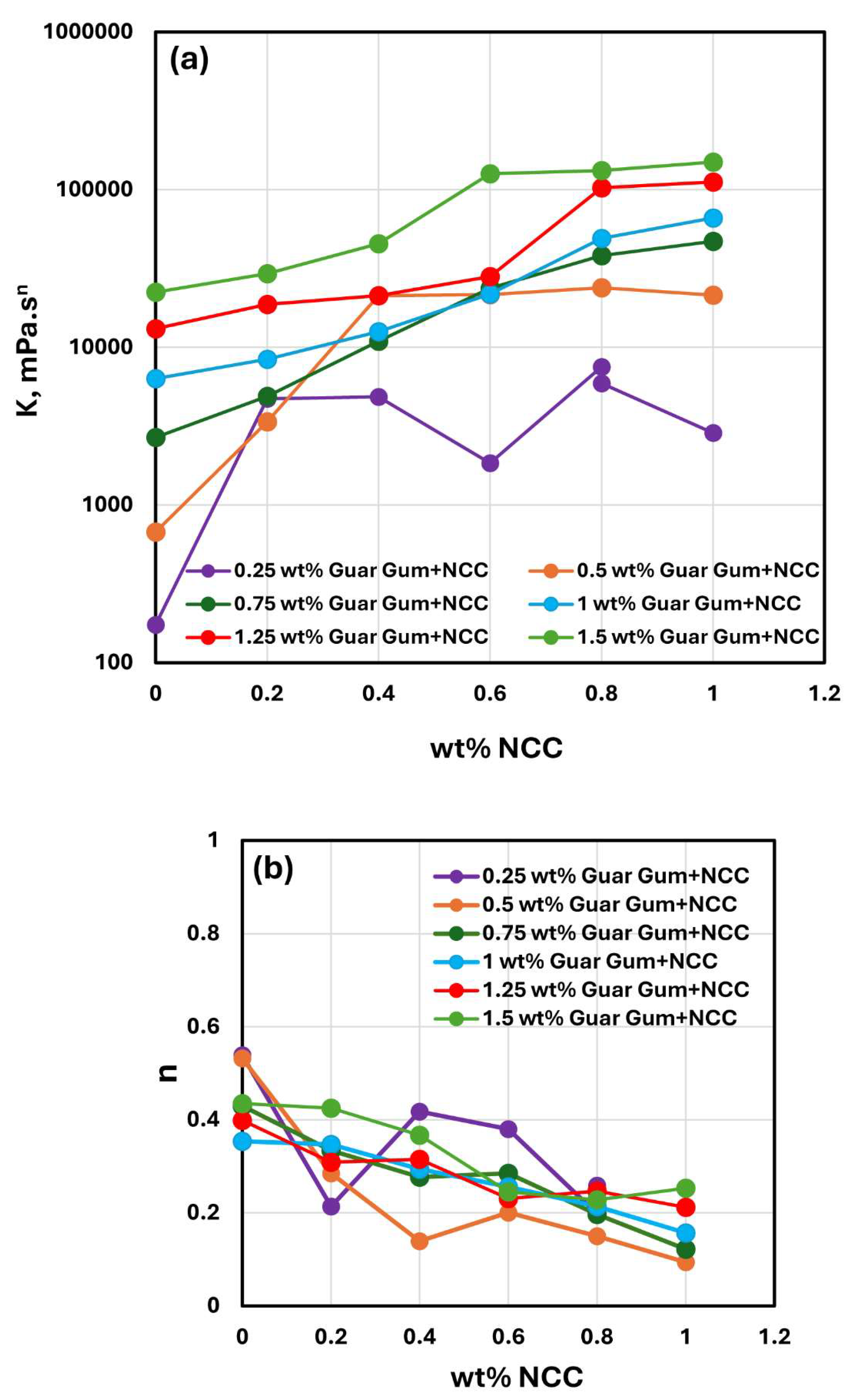

The consistency index

and flow behavior index

values for NCC-Guar Gum mixtures with different concentrations of guar gum are compared in

Figure 12. With the increase in guar gum concentration, the consistency index

generally increases at any given NCC concentration. No clear trend is observed in the flow behavior index

with the increase in guar gum concentration. However, the flow behavior index generally decreases with the increase in NCC concentration at any given guar gum concentration.

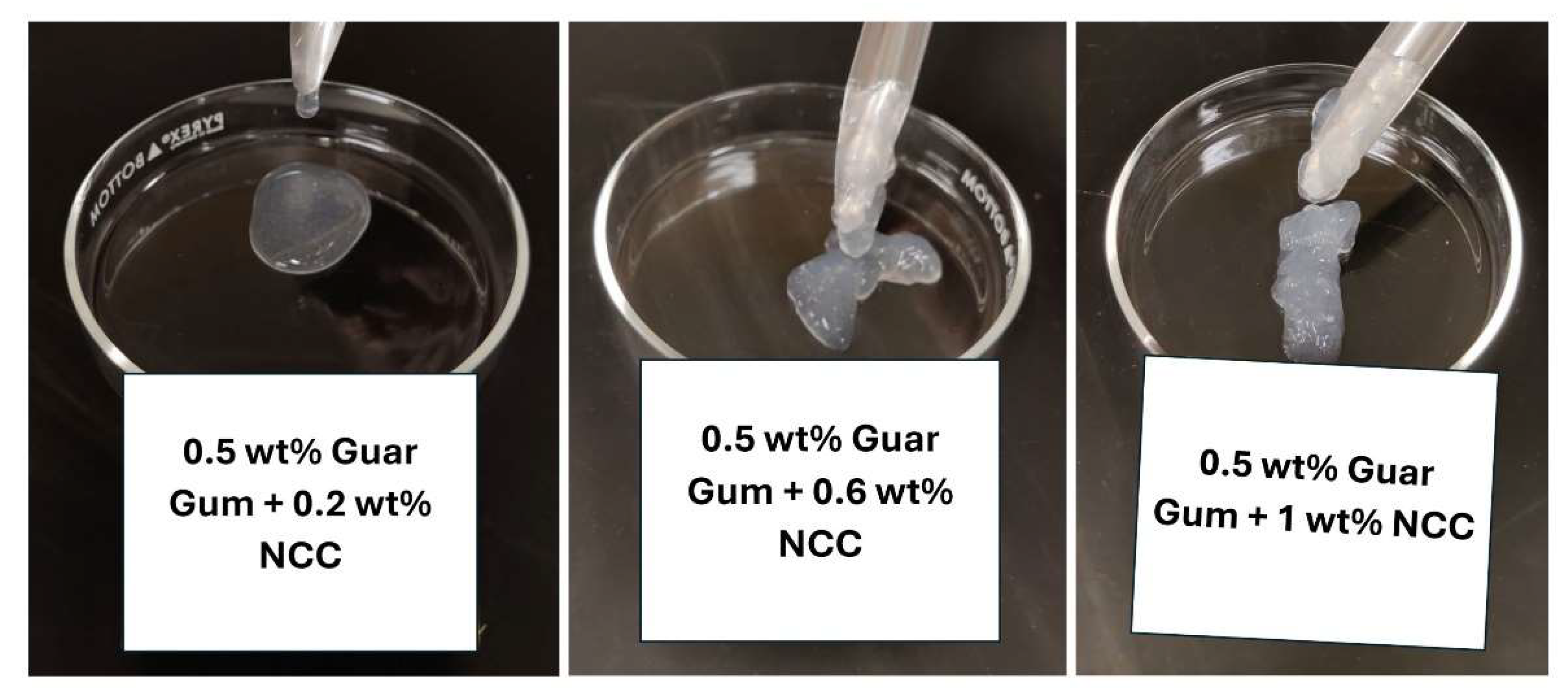

The images of the samples of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures with increasing NCC concentration but fixed guar gum concentration of 0.5 wt% are shown in

Figure 13. The mixture is fluidic at low CMC and NCC concentrations. The mixture is fluidic at low NCC concentration but becomes a gel at high concentration.

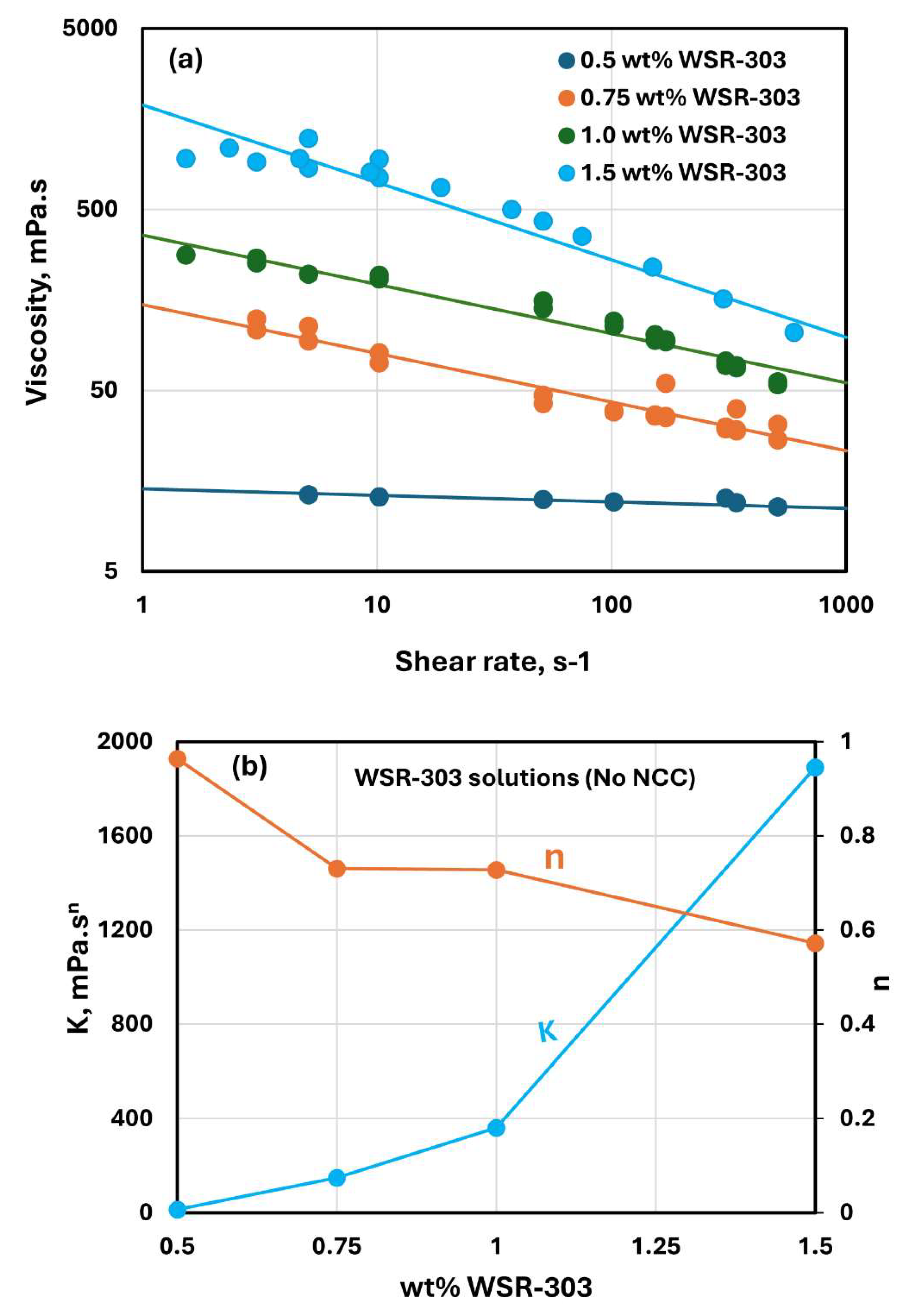

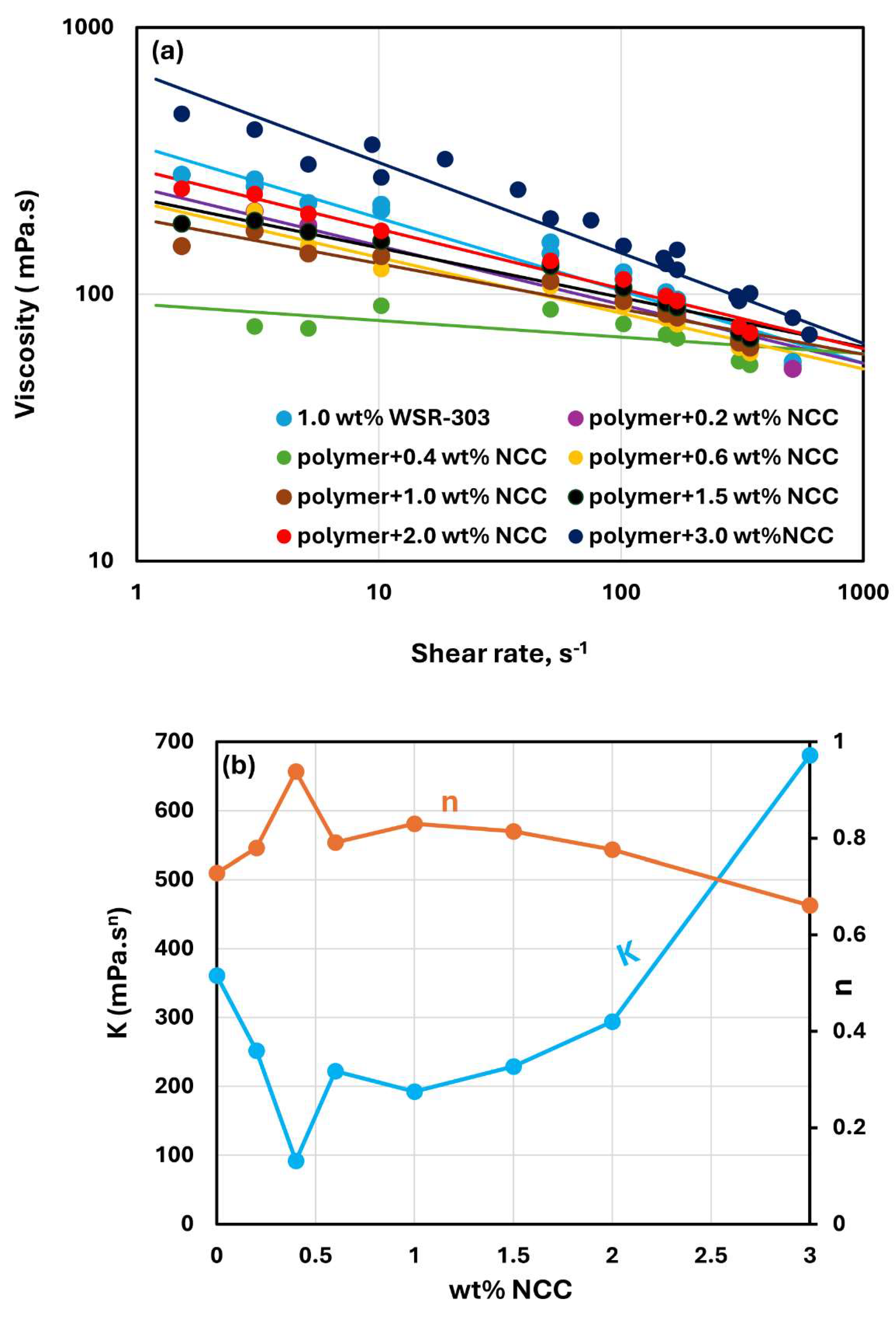

3.3. Rheology of WSR-303 Solutions and NCC-WSR Mixtures

The flow curves of WSR-303 solutions without any NCC addition are shown in

Figure 14. The WSR-303 solutions are shear-thinning, and they follow the power-law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

increases and the flow behavior index

decreases with the increase in WSR-303 concentration. The flow behavior index

of the WSR-303 solutions is in the range of 0.57-0.96 over the WSR-303 concentration investigated. Note that WSR-303 solutions are less shear-thinning as compared with CMC and guar gum solutions. For example, the flow behavior index

of the guar gum is in the range of 0.35-0.54 over the guar gum concentration investigated.

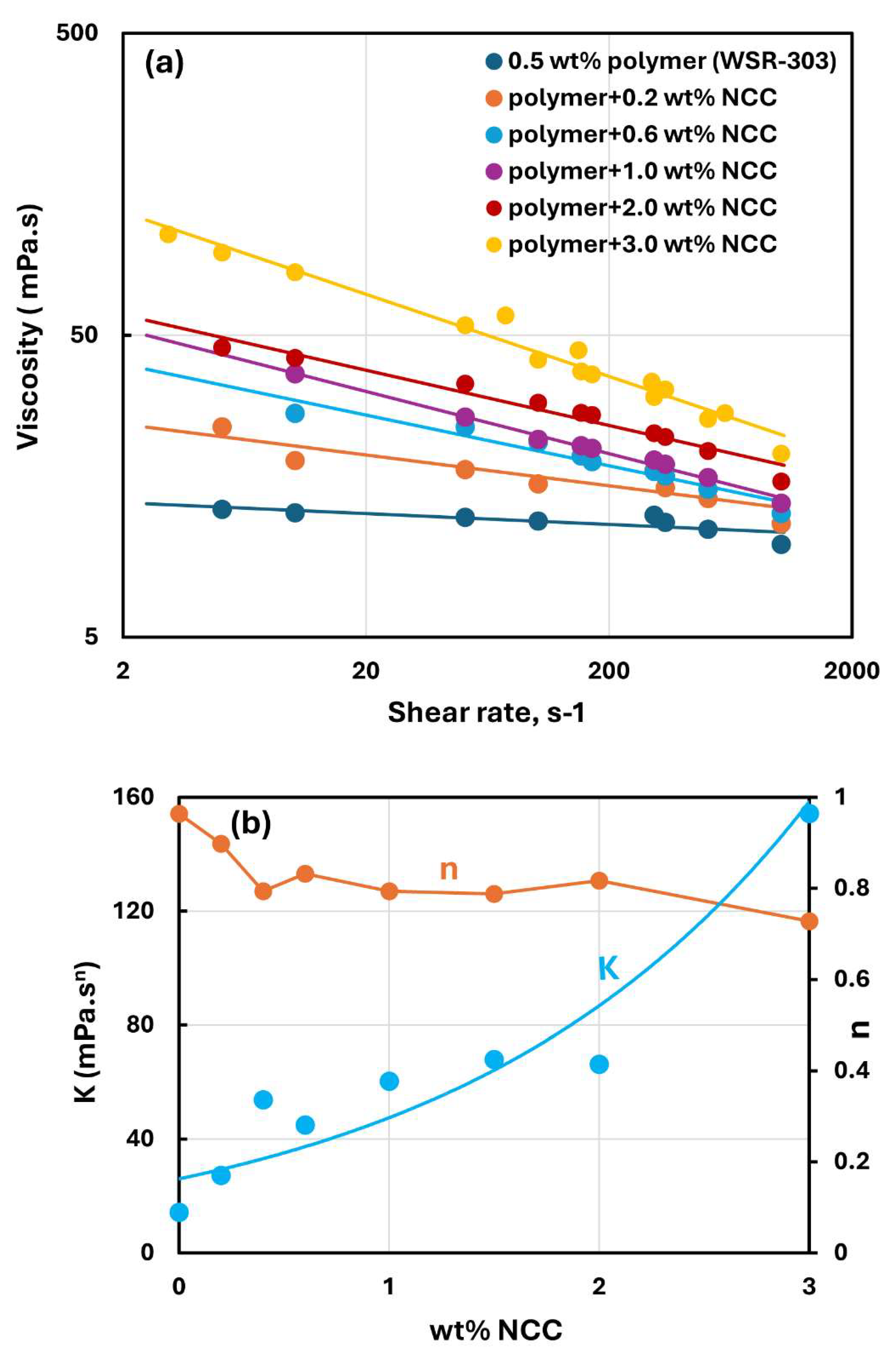

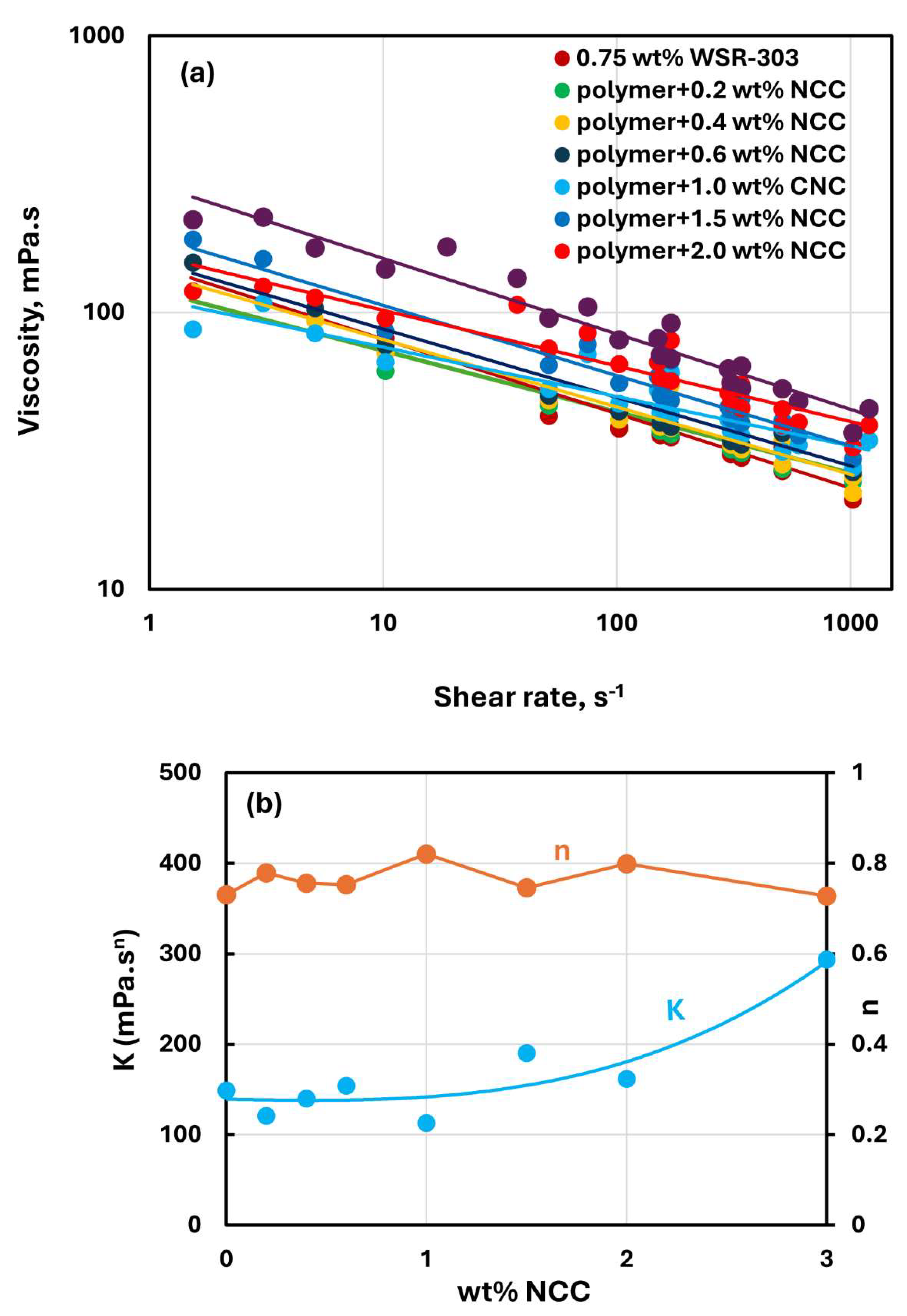

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show the rheological behavior of mixtures of NCC and WSR-303 polymer solutions. The NCC concentration varies from 0 to 3 wt%. The flow curves (viscosity versus shear rate plots) for NCC-WSR-303 mixtures can be described satisfactorily by the power law model, Equation (2). For polymer (WSR-303) concentrations at 0.5 wt% (

Figure 15) and 0.75 wt% (

Figure 16), the addition of NCC to WSR-303 solution causes an increase in the consistency index and a decrease in the flow behavior index of the system. However, the increase in

and a decrease in

with the increase in NCC concentration are only modest. At a WSR-303 concentration of 1 wt% (

Figure 17), the consistency index

and flow behavior index

exhibit unusual behavior. The consistency index (

) decreases initially with the increase in NCC concentration, reaches a minimum value and rises with further increase in NCC concentration. The flow behavior index (

) increases initially to a maximum value before decreasing with the increase in NCC concentration.

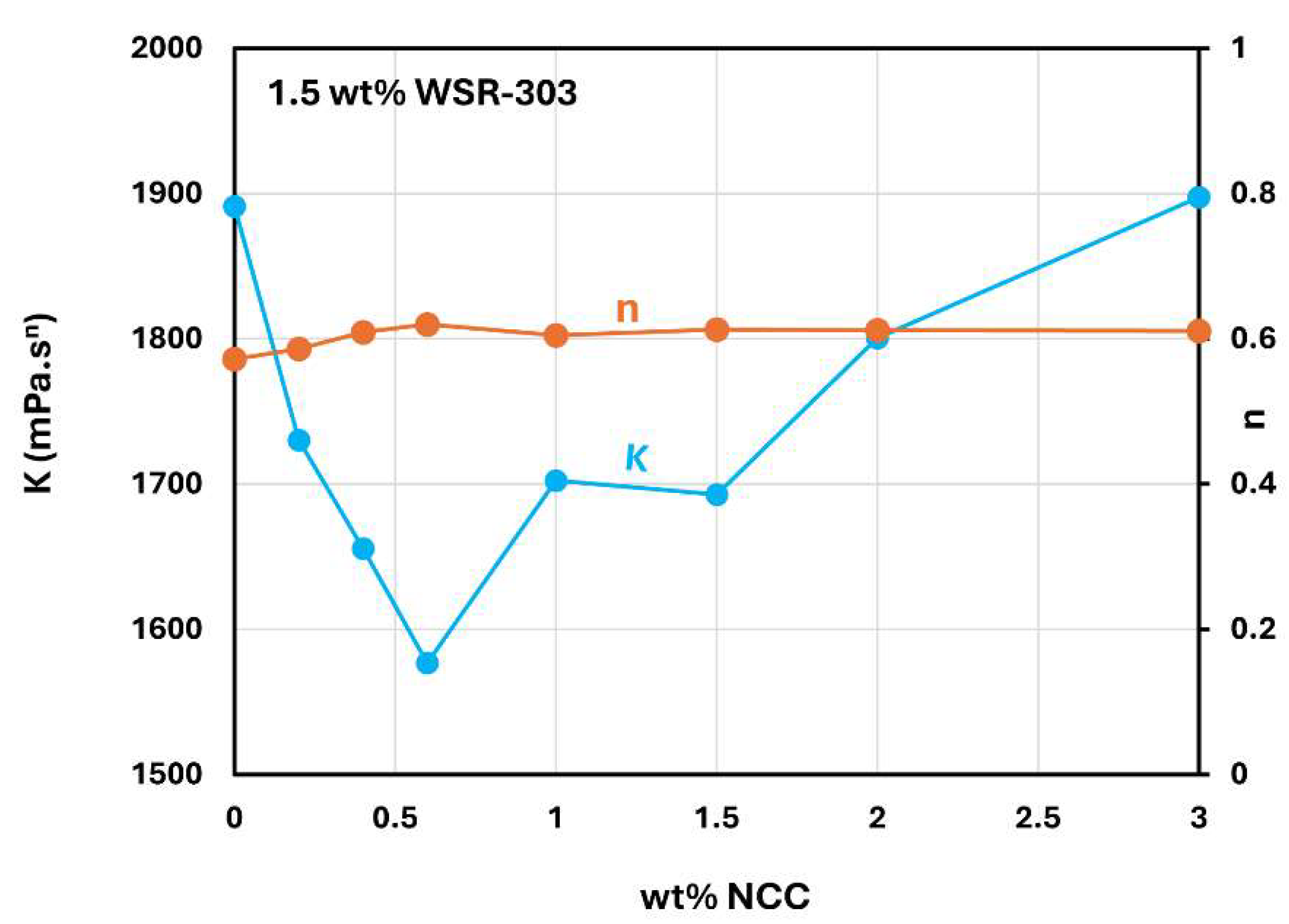

Figure 18 shows the consistency index (

) and flow behavior index (

) of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a WSR-303 concentration of 1.5 wt%. With the increase in NCC concentration, the consistency index (

) goes through a sharp minimum whereas the flow behavior index (

) remains nearly constant around 0.6.

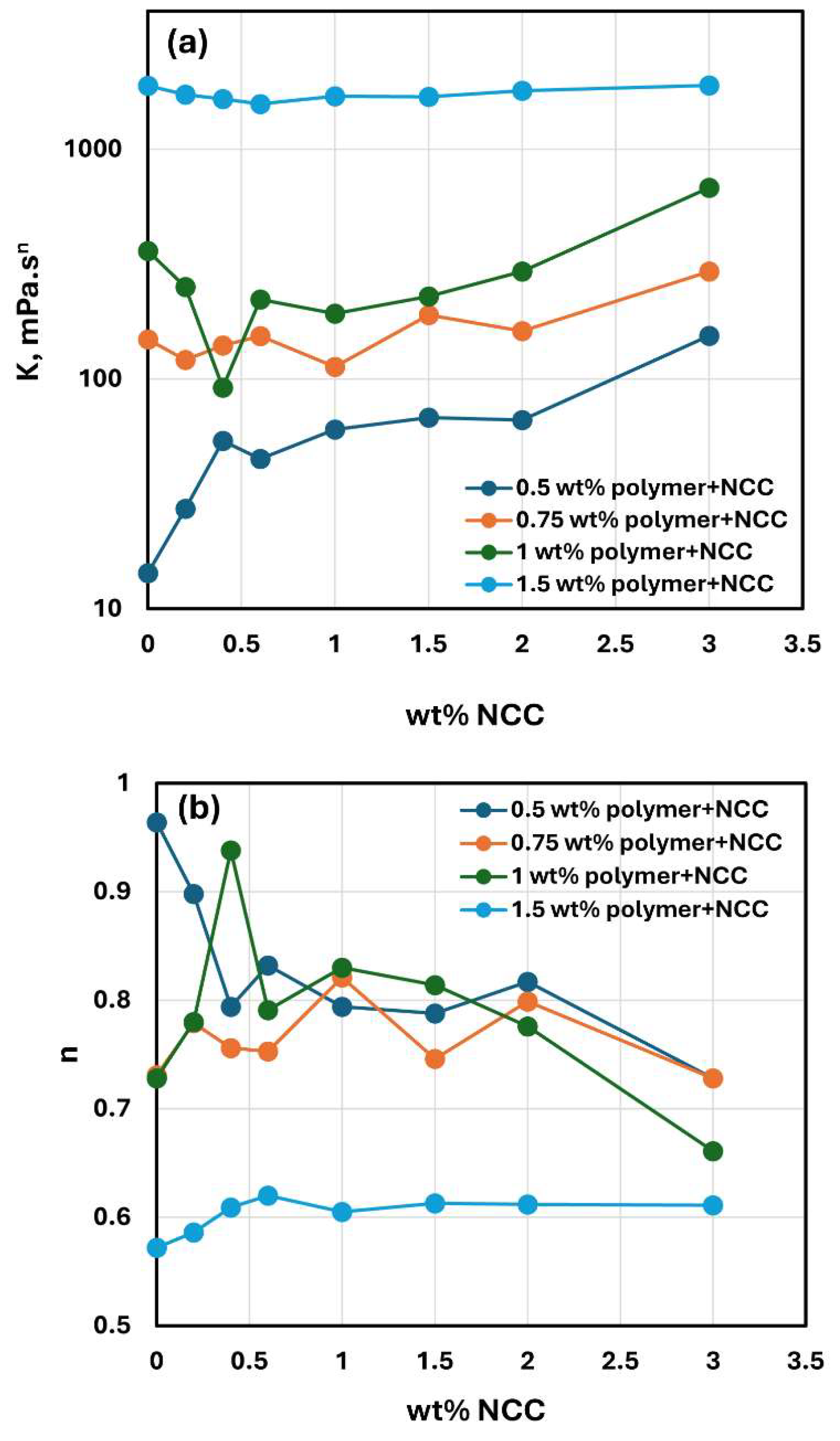

Figure 19 compares the consistency index

and flow behavior index

values for NCC-WSR-303 mixtures with different concentrations of WSR-303. At NCC concentrations higher than 1 wt%, the consistency index

increases with the increase in NCC concentration at any given WSR-303 concentration. At NCC concentrations lower than 1 wt%, the consistency index

exhibits a minimum for mixtures with WSR-303 concentrations 1 wt% and 1.5 wt%. The flow behavior index

of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures is similar when WSR-303 concentration is less than 1 wt%. A sharp drop in

occurs when the WSR-303 concentration increases from 1 wt% to 1.5 wt%, indicating that NCC-WSR-303 mixtures are highly shear-thinning at a high WSR-303 concentration of 1.5 wt% over the full range of NCC concentration investigated.

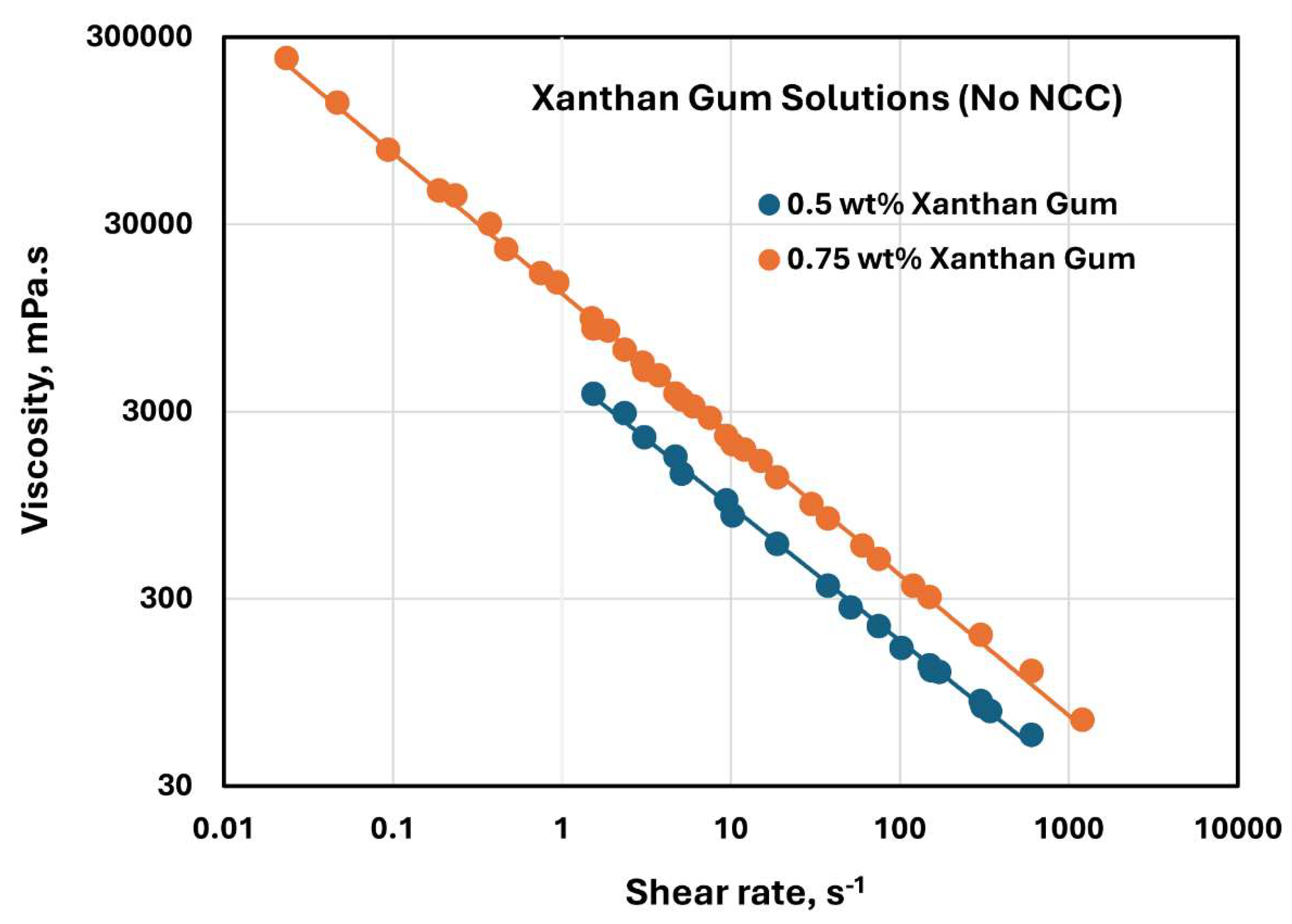

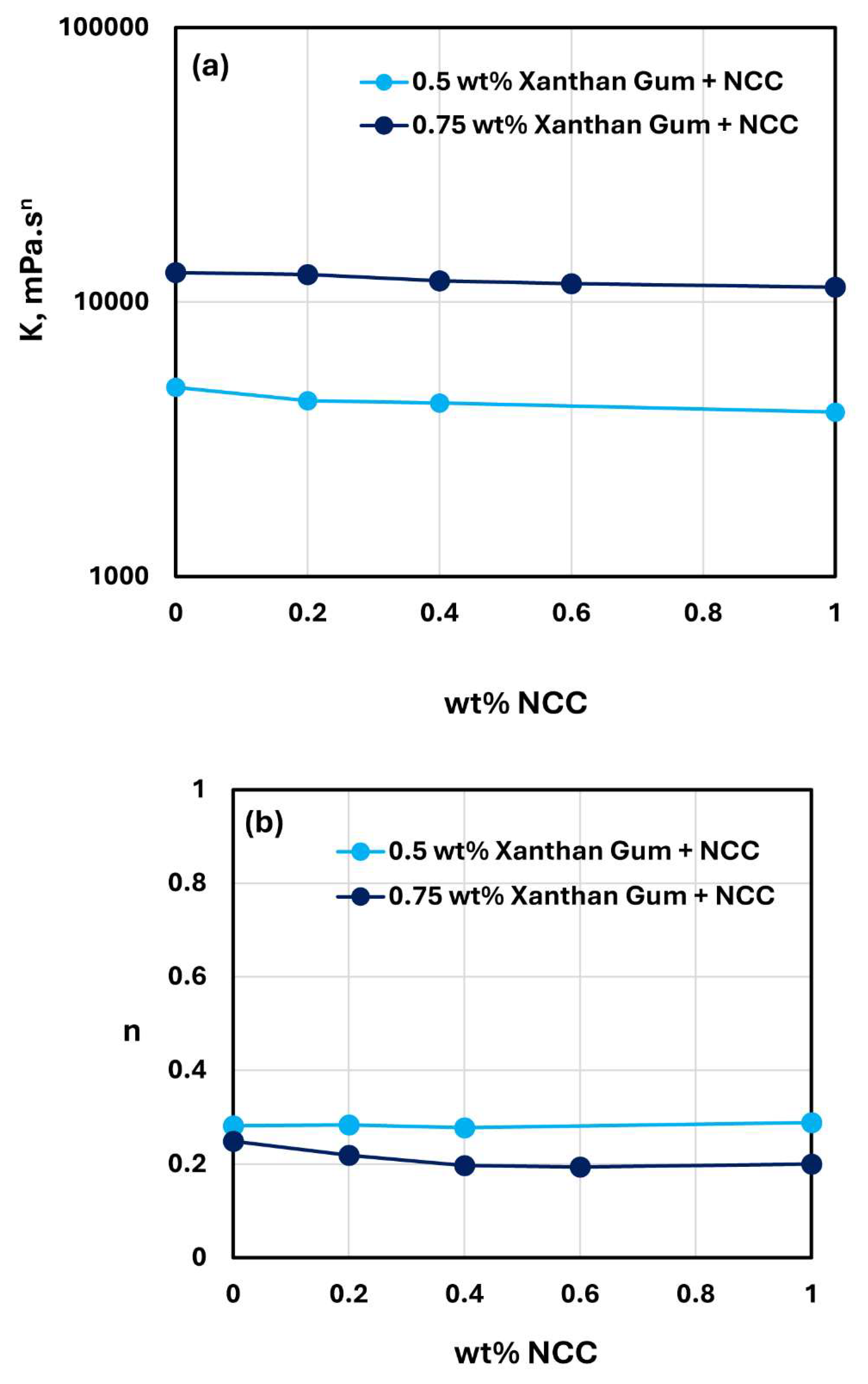

3.4. Rheology of Xanthan Gum Solutions and NCC-Xanthan Gum Mixtures

The rheological behavior of Xanthan gum solutions without any NCC addition is shown in

Figure 20. The data were obtained at two xanthan gum concentrations of 0.5 and 0.75 wt%. As shown in the figure, the xanthan gum solutions are highly shear-thinning, and they follow the power-law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

increases substantially with the increase in xanthan gum concentration from 0.5 to 0.75 wt%. The value of

is 4888.3 mPa.s

n at xanthan gum concentration of 0.5 wt% and 12798 mPa.s

n at xanthan gum concentration of 0.75 wt%. The flow behavior index

decreases from 0.282 at xanthan gum concentration of 0.5 wt% to 0.249 at xanthan gum concentration of 0.75 wt%.

The rheological behavior of mixtures of NCC and Xanthan gum solutions was studied over the NCC concentration range of 0 to 1 wt%. The viscosity versus shear rate data obtained for NCC-Xanthan gum mixtures was fitted satisfactorily by the power law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

and flow behavior index

values for NCC-Xanthan Gum mixtures with different concentrations of Xanthan gum are compared in

Figure 21. At any given Xanthan gum concentration, the consistency index

and flow behavior index

are almost constant with the increase in NCC concentration. Thus, NCC addition to Xanthan gum solutions has negligible effect on the rheology of NCC-Xanthan gum mixtures.

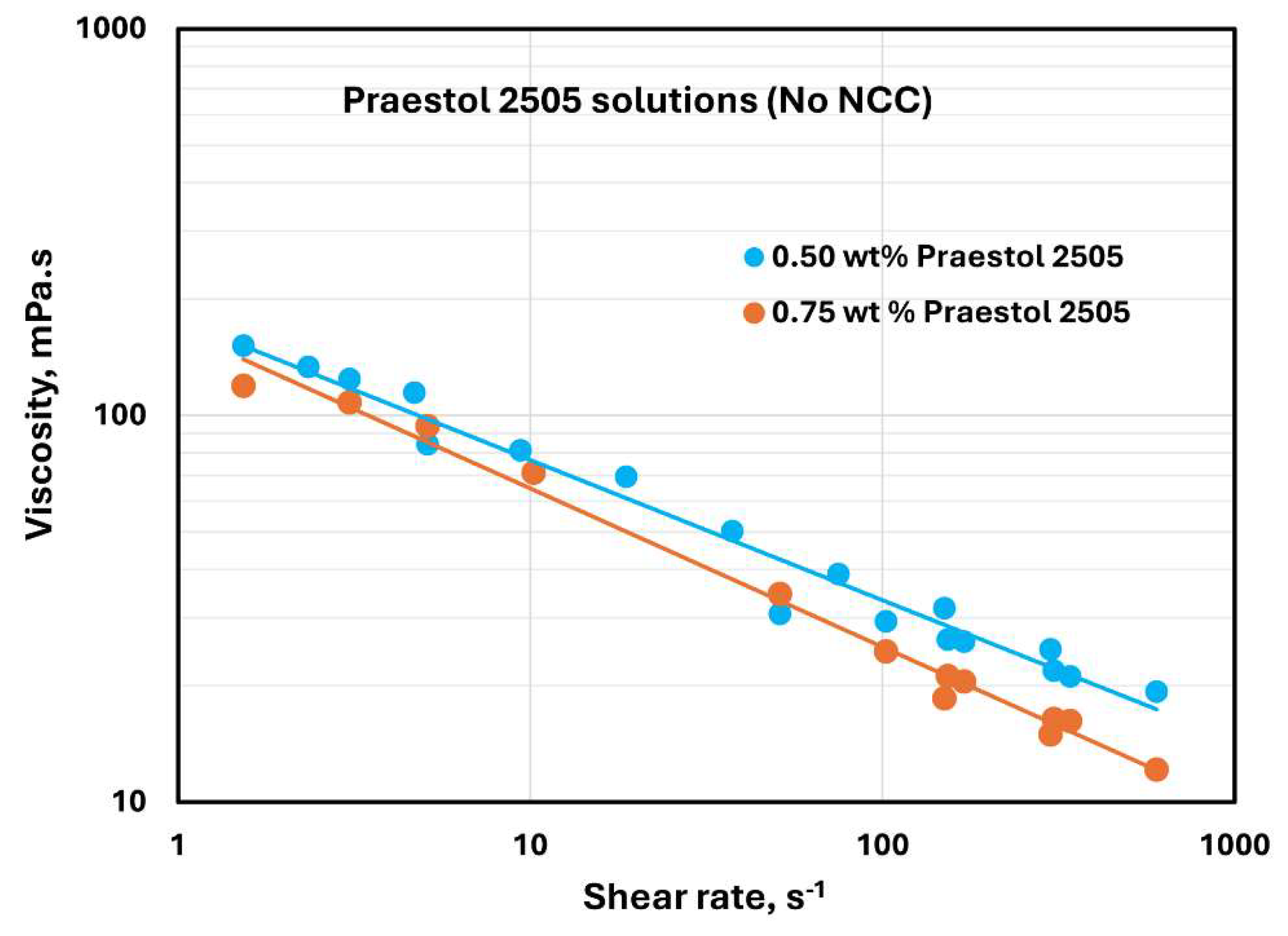

3.5. Rheology of Praestol 2505 Solutions and NCC-Praestol 2505 Mixtures

The flow curves of Praestol 2505 polymer solutions without any NCC addition are shown in

Figure 22 at two different polymer concentrations of 0.5 and 0.75 wt%. The Praestol 2505 polymer solutions are shear-thinning, and they follow the power-law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

values are 176.73 and 166.45 mPa.s

n at 0.5 and 0.75 wt% polymer concentrations, respectively. The flow behavior index

values of the Praestol 2505 polymer solutions are 0.637 and 0.59 at 0.5 and 0.75 wt% polymer concentrations, respectively.

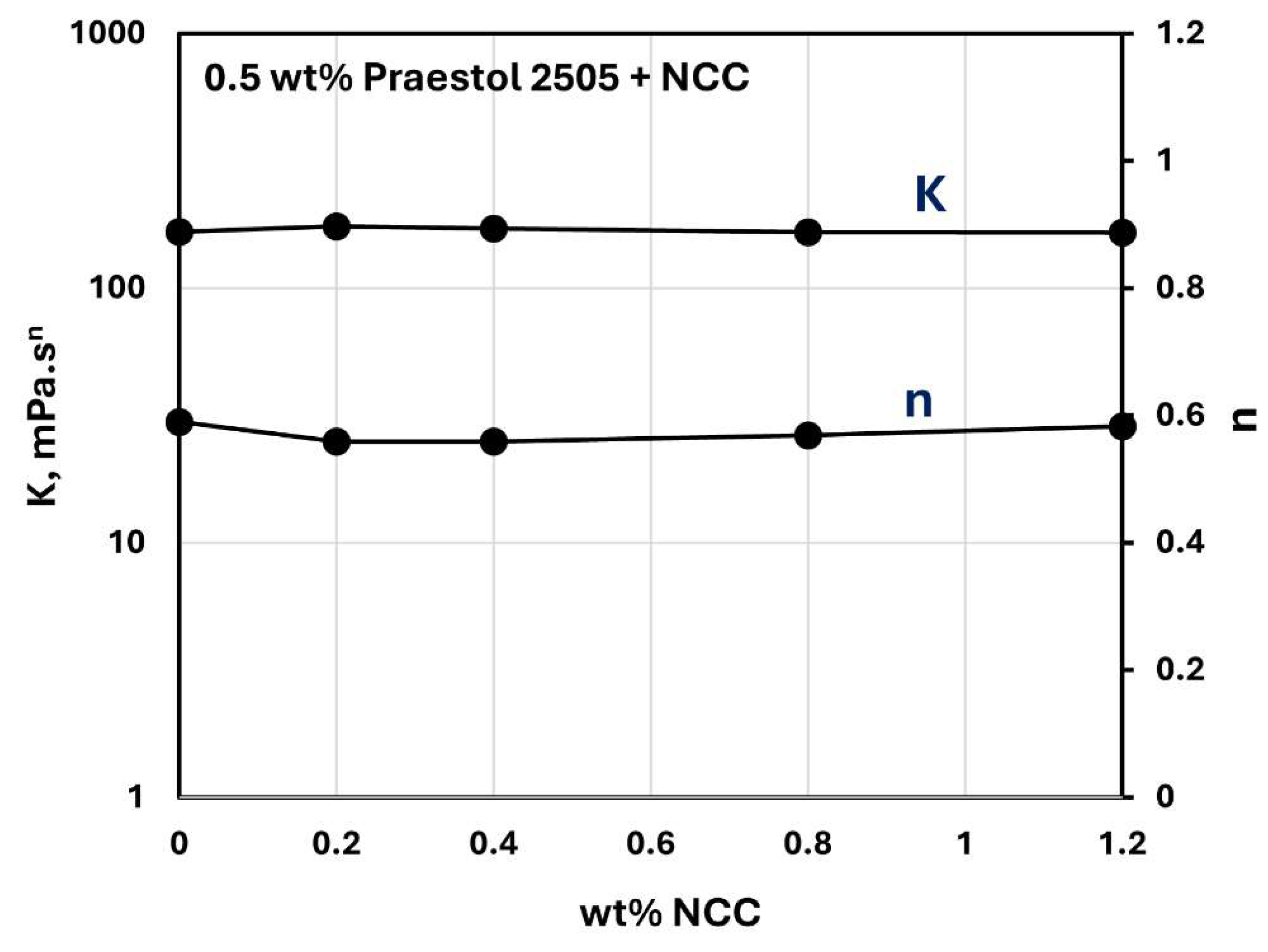

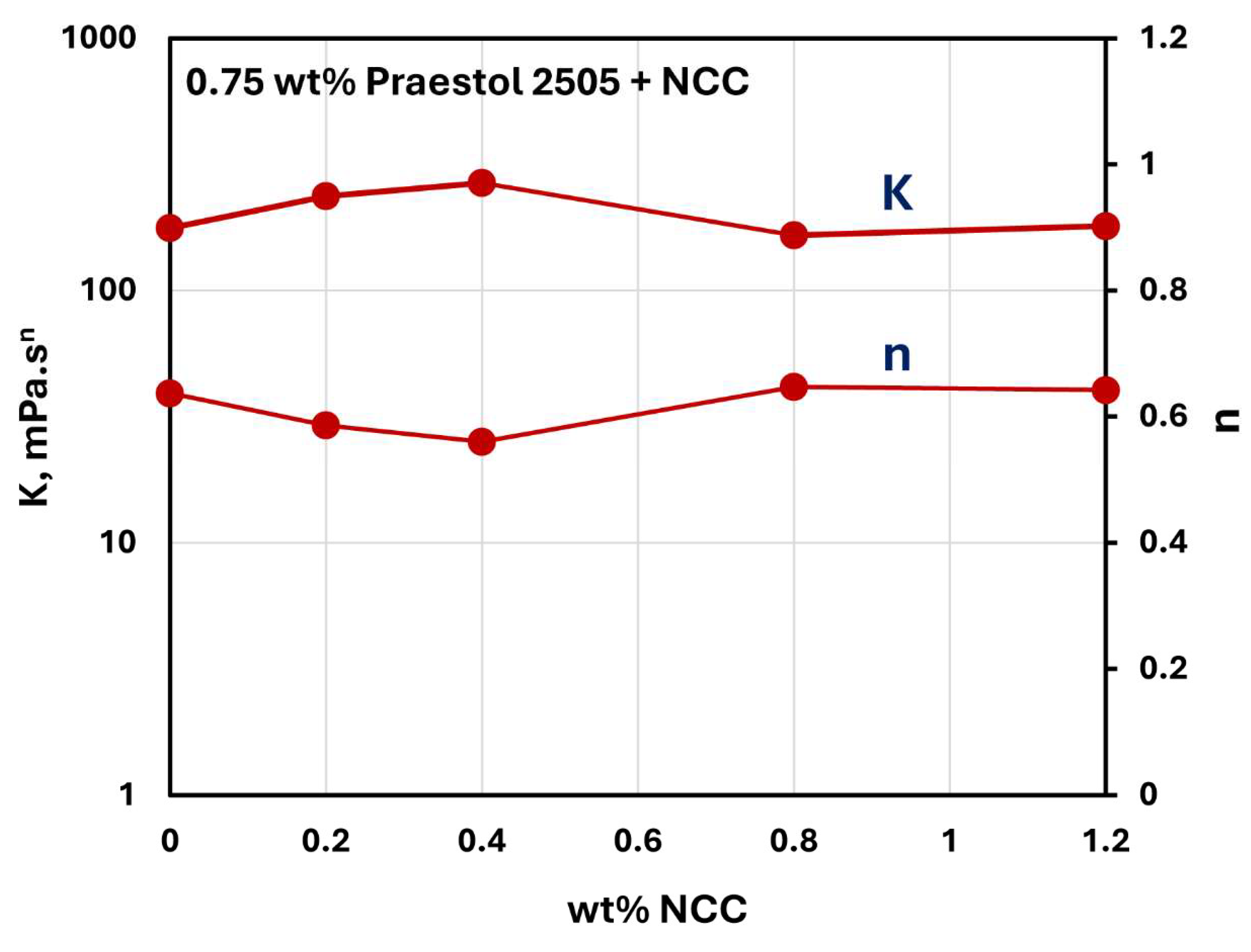

Figure 23 and

Figure 24 show the influence of NCC addition on the consistency index

and flow behavior index

of NCC-Praestol 2505 mixtures with NCC concentration at two different concentrations of Praestol 2505. The consistency index

and flow behavior index

are nearly constant with the increase in NCC concentration. Thus, the addition of cellulose nanocrystals to Praestol 2505 polymer solutions is negligible.

3.6. Rheology of JR-400 Solutions and NCC-JR-400 Mixtures

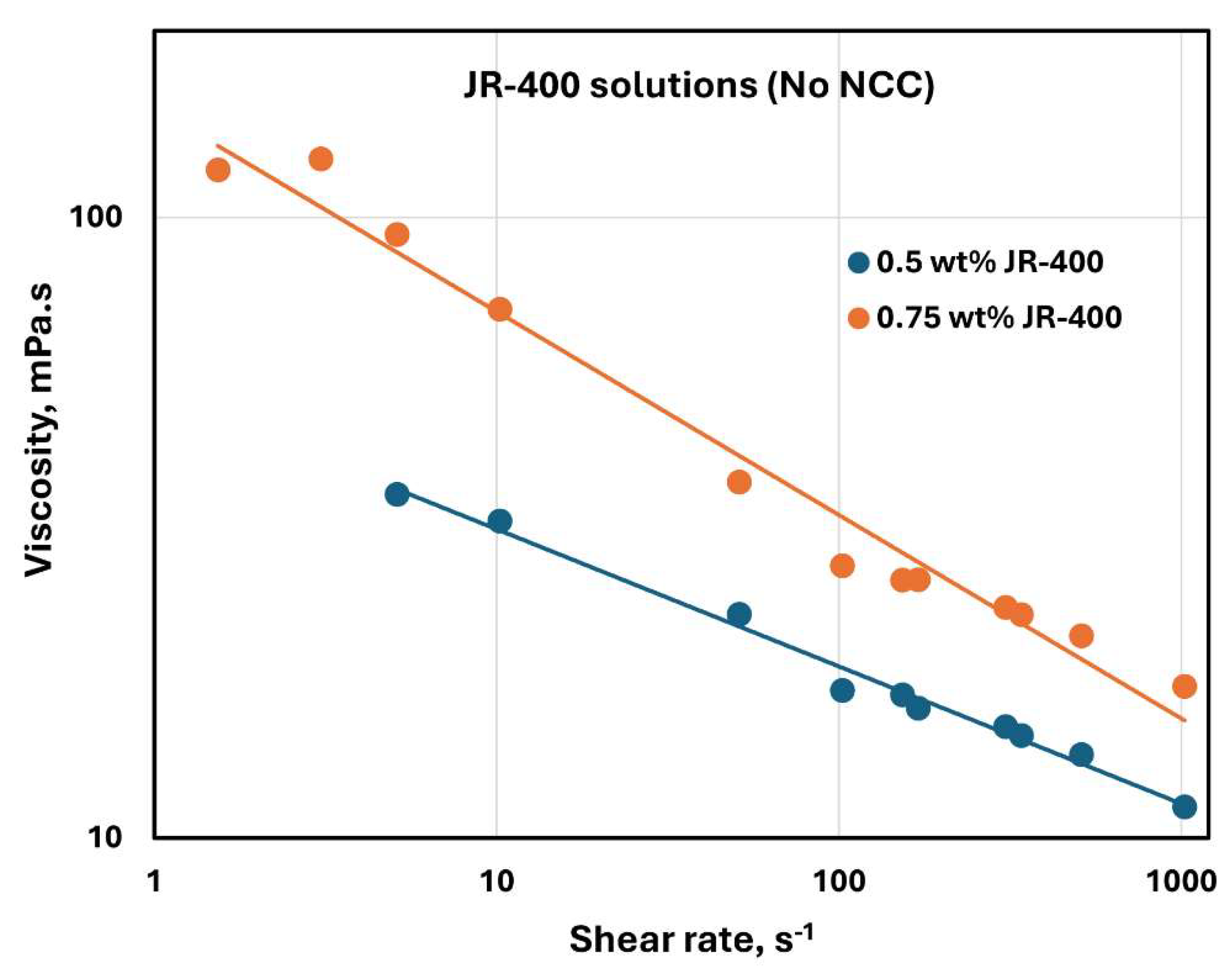

The rheological behavior of JR-400 polymer solutions without any NCC addition is shown in

Figure 25. The data were obtained at two JR-400 concentrations of 0.5 and 0.75 wt%. The JR-400 polymer solutions are shear-thinning, and they follow the power-law model, Equation (2). The consistency index

increases substantially with the increase in JR-400 concentration from 0.5 to 0.75 wt%. The value of

is 52.32 mPa.s

n at JR-400 concentration of 0.5 wt% and 150.08 mPa.s

n at JR-400 concentration of 0.75 wt%. The flow behavior index

decreases from 0.779 at JR-400 concentration of 0.5 wt% to 0.672 at JR-400 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

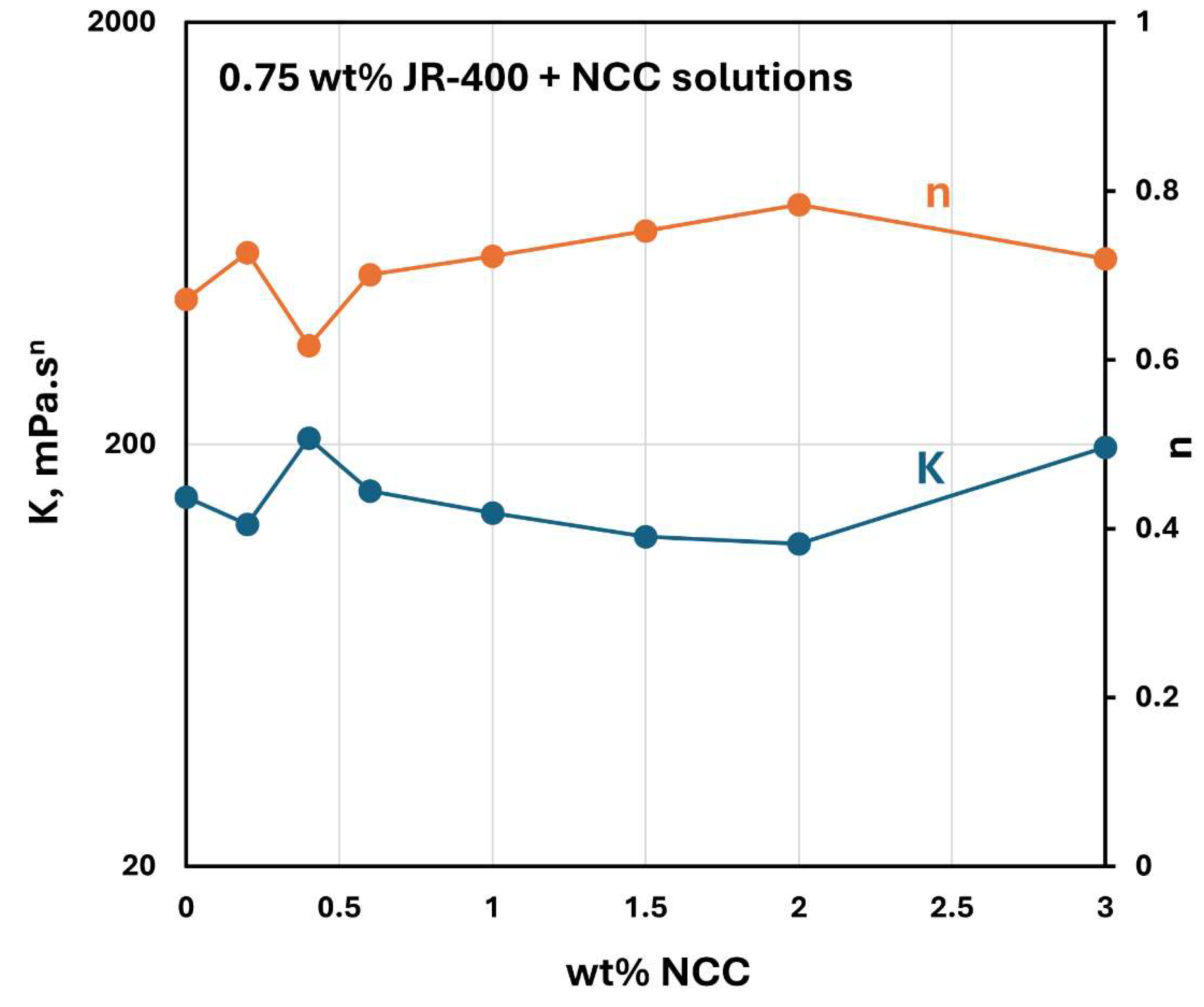

The influence of NCC addition to JR-400 polymer solution is shown in

Figure 26. The power-law constants

and

for NCC-JR-400 mixtures are plotted as a function of NCC concentration, keeping the JR-400 polymer concentration constant at 0.75 wt%. As can be seen, the consistency index

and flow behavior index

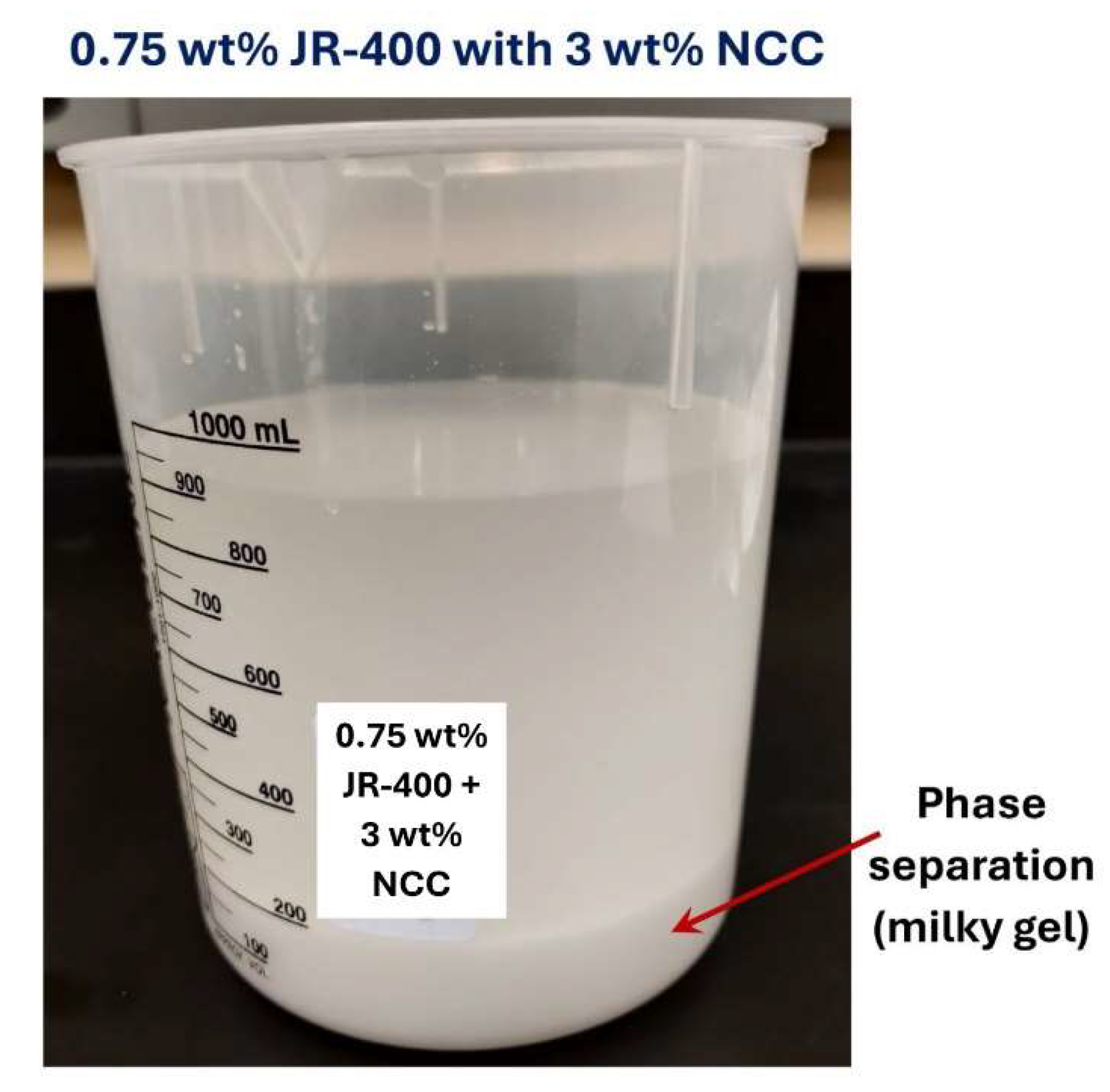

remain nearly constant with the NCC addition. Thus, the addition of cellulose nanocrystals to JR-400 polymer solution has a negligible effect on the rheological properties of the NCC-JR-400 mixture. Interestingly, phase separation (see

Figure 27) occurred in NCC-JR-400 mixture when the NCC concentration of the mixture was increased to 3 wt%. A thick layer of milky gel (concentrated suspension of cellulose nanocrystals in polymeric aqueous phase) was observed at the bottom of the container. This observation is not unexpected as the NCC and JR-400 polymer are oppositely charged and they likely form aggregates and precipitate out.

4. Discussion

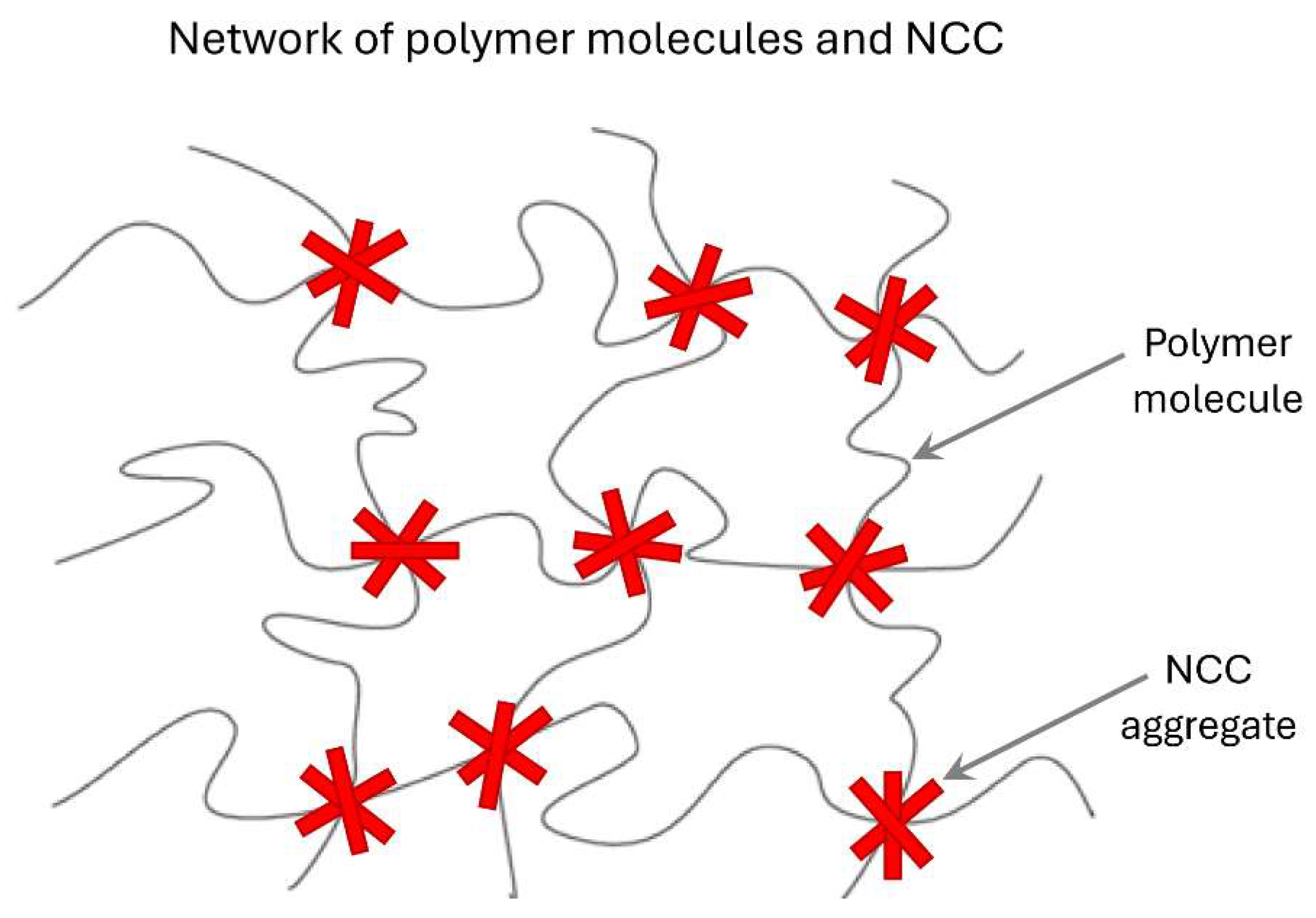

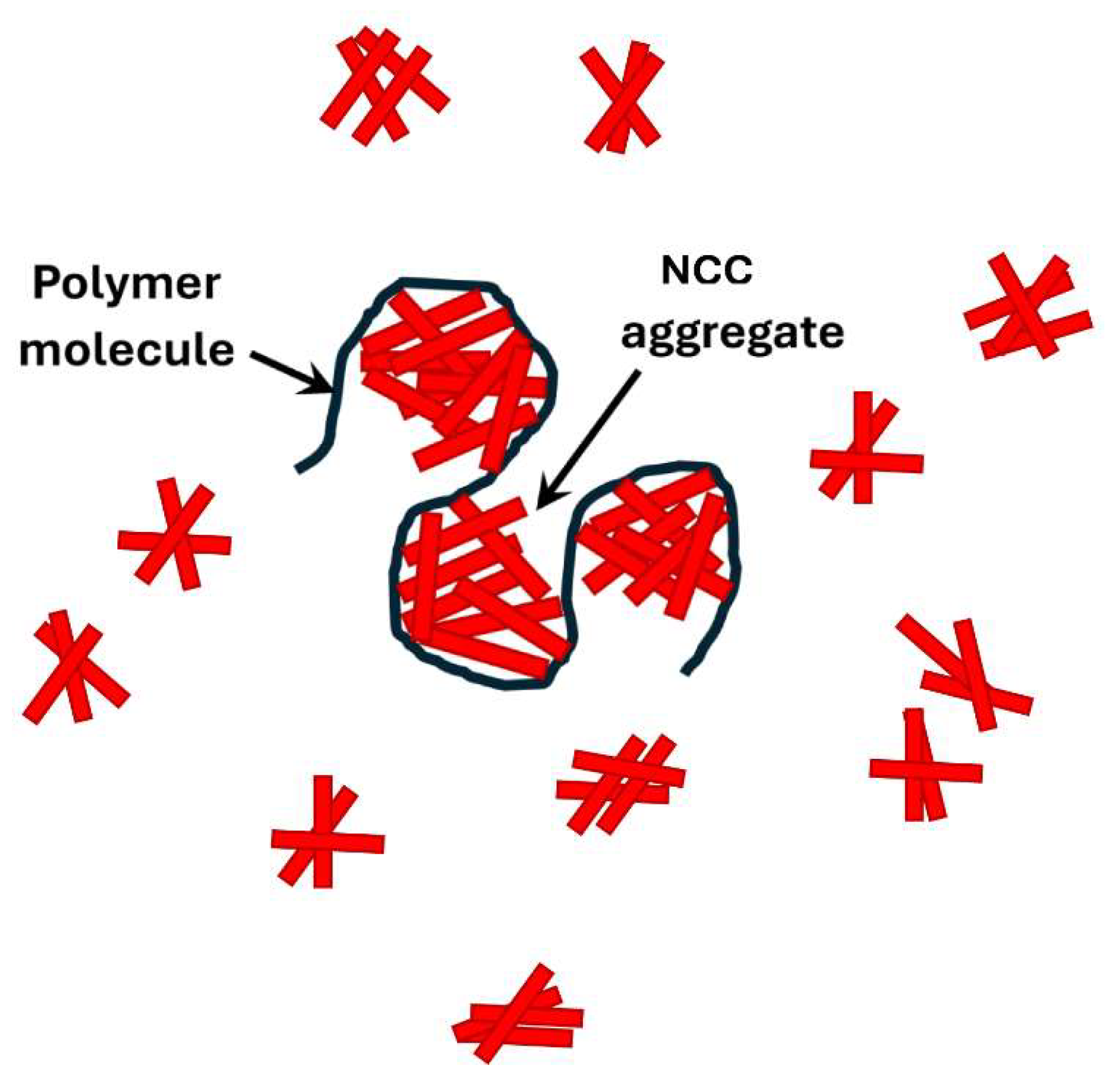

The interactions between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals (NCC) and different polymers are summarized in

Table 3. Mixtures of NCC-CMC and NCC-Guar Gum exhibit strong interactions as reflected in their rheological parameters (

and

). The high values of

and low values of

exhibited by these mixtures are likely to be due to the formation of a three-dimensional interconnected structure of nanocrystal aggregates and polymer macromolecules as depicted schematically in

Figure 28.

The decrease in consistency index (

) and the observed minimum in

in NCC-WSR-303 mixtures with the addition of cellulose nanocrystals to WSR-303 solution is likely due to folding or collapse of polymer chains upon the addition of nanocrystals. While the exact nature of interactions between nanocrystals and polymer chains is not known, some possibilities are depicted schematically in

Figure 29. In

Figure 29(a), the nanocrystals form aggregates at various locations on the polymer chain. In

Figure 29(b), the polymer molecule wraps around the aggregates of cellulose nanocrystals. In

Figure 29 (c), the polymer chains collapse on to the aggregates of cellulose nanocrystals. The folding or collapse of polymer chains can explain the decrease in consistency of NCC-polymer mixtures. In NCC-polymer mixtures where the changes in rheological properties are observed to be negligible (Xanthn Gum, Praestol 2505, JR-400), it is possible that some of the NCC aggregated with the polymer chains resulting in folding of chains and some of the NCC remained in the aqueous phase, as shown schematically in

Figure 30. The folding of the polymer chains would tend to decrease the consistency whereas the addition of NCC to the aqueous phase would tend to increase the consistency. Due to these two opposing effects, there occurs negligible changes in the rheological properties of the NCC-polymer mixtures.

Finally, it should be noted that the discussion of NCC-polymer microstructure presented here is somewhat speculative as there is no experimental proof available at present. Clearly further studies are needed to explore the microstructure details of NCC-polymer mixtures experimentally using appropriate imaging techniques.

5. Conclusions

The interactions between the cellulose nanocrystals (referred to as NCC) and the polymers were investigated experimentally using rheological measurements. The polymers studied were anionic sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), non-ionic guar gum, non-ionic polyethylene oxide (WSR-303), anionic xanthan gum, anionic polyacrylamide (Praestol 2505), and cationic quaternary ammonium salt of hydroxyethyl cellulose (JR-400). Based on experimental work, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The interaction between cellulose nanocrystals (negatively charged) and anionic polymer CMC is strong. The consistency index increases sharply, and the flow behavior index decreases sharply upon addition of NCC to CMC solution. The changes in consistency and flow behavior indices are explained in terms of the formation of a three-dimensional network of NCC aggregates and polymer chains.

The interaction between cellulose nanocrystals and non-ionic guar gum is also strong. The consistency index rises substantially, and flow behavior index decreases with the addition of NCC to guar gum solution. However, the increase in consistency index observed in NCC-Guar gum mixtures with the addition of NCC is less severe as compared with the changes observed in NCC-CMC mixtures.

The interaction between cellulose nanocrystals and non-ionic polymer WSR-303 is moderate. However, the interaction is both positive and negative in that the consistency index increases as well as decreases depending upon the polymer and NCC concentrations. At polymer concentrations above 0.75 wt%, the consistency index goes through a minimum upon addition of NCC.

The interactions between cellulose nanocrystals and the following polymers are found to be weak in nature: anionic xanthan gum, anionic Praestol 2505, and cationic JR-400. The changes observed in the consistency and flow behavior indices upon addition of NCC to polymer solutions are small or negligible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.; methodology, R.P., P.D. and S.P.; validation, R.P., P.D. and S.P.; formal analysis, R.P.; investigation, R.P., P.D. and S.P.; resources, R.P.; data curation, R.P., P.D. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.; writing—review and editing, R.P.; visualization, R.P.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Discovery Grant awarded to R.P. by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pal, R. Rheology of emulsions containing polymeric liquids. Encyclopedia of Emulsion Technology, Becher, P.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, USA, 1996; Volume 4, pp. 93–263. [Google Scholar]

- Blanshard, J.M.V.; Mitchell, J.R. Polysaccharides in Food. Butterworths: London, 1979.

- Dickinson, E.; Stainsby, G. Colloids in Food. Applied Science: London, 1982.

- Graham, H.D. Food Colloids. AVI Publishing: Westport, Conn., USA, 1977.

- Whisler, R.L.; BeMiller, J.N. Industrial Gums. Academic Press: New York, USA, 1973.

- Dickinson, E. Food Polymers, Gels, and Colloids. Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 1991.

- Schurz, J. Rheology of polymer solutions of the network type. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1991, 16, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Raveshiyan, S.; Amini, Y.; Zadhoush, A. A critical review with emphasis on the rheological behavior and properties of polymer solutions and their role in membrane formation, morphology, and performance. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 319, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosic, R.; Pelipenko, J.; Kocbek, P.; Baumgartner, S.; Bester-Rogac, M.; Kristl, J. The role of rheology of polymer solutions in predicting nanofiber formation by electrospinning. European Polymer Journal 2012, 48, 1374–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, R.I.; Kibbelaar, H.V.M.; Deblais, A.; Bonn, D. Rheology of emulsions with polymer solutions as the continuous phase. J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 2022, 310, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T. Rheology of stiff-chain polymer solutions. J. Rheol. 2022, 66, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annable, T.; Buscall, R.; Ettelaie, R.; Whittlestone, D. The rheology of solutions of associating polymers: Comparison of experimental behavior with transient network theory. J. Rheol. 1993, 37, 695–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.G.; Desai, P.S. Modeling the rheology of polymer melts and solutions. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2015, 47, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ge, J.; Wu, H.; Guo, H.; Shan, J.; Zhang, G. Phase behavior of colloidal nanoparticles and their enhancement effect on the rheological properties of polymer solutions and gels. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 8513–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.; Colby, R.H. Rheology of entangles polyelectrolyte solutions. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohle, K.; Yoshida, T.; Tasaka, Y.; Mural, Y. Effective rheology mapping for characterizing polymer solutions utilizing ultrasonic spinning rheometry. Experiments in Fluids. 2022, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Katashima, T. Rheological studies on polymer networks with static and dynamic crosslinks. Polymer Journal 2021, 53, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, P.; Schweissinger, E.; Maier, S.; Hilf, S.; Sirak, S.; Martini, A. Effect of polymer structure and chemistry on viscosity index, thickening efficiency, and traction coefficient of lubricants. J. Molecular Liquids 2022, 359, 119215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathapan, R.; Thapa, R.; Garnier, G.; Tabor, R.F. Modulating the zeta potential of cellulose nanocrystals using salts and surfactants. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2016, 509, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Hsieh, Y. Preparation and properties of cellulose nanocrystals: rods, spheres, and network. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 82, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Vidal, D.; Bertrand, F.; Tavares, J.R.; Heuzey, M. Evidence-based guidelines for the ultrasonic dispersion of cellulose nanocrystals. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2021, 71, 105378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaeiarani, J.; Bajwa, D.S.; Chanda, S. Cellulose nanocrystal-based composites: A review. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021, 5, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Biswas, S.K.; Han, J.; Tanpichai, S.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; Das, A.K.; Yano, H. Surface and interface engineering for nanocellulosic advanced materials. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2002264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trache, D.; Hussin, M.H.; Haafiz, M.K.M.; Thakur, V.K. Recent progress in cellulose nanocrystals: sources and production. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 1763–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X.; Haq, A.; Ullah, R.; Khan, F.U.; Iqbal, M. Advance study of cellulose nanocrystals properties and applications. J. Polymers and Environment 2020, 28, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Ullah, A.; Fan, H.; Ullah, R.; Haq, F.; Khan, F.U.; Iqbal, M.; Wei, J. Cellulose nanocrystals applications in health, medicine, and catalysis. J. Polymers and Environment 2021, 29, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose processing properties and potential applications. Current Forestry Reports 2019, 5, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderfleet, O.M.; Cranston, E.D. Production routes to tailor the performance of cellulose nanocrystals. Nature Reviews/Materials 2021, 6, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Ogunsona, E.; Mekonnen, T. Trends in advanced functional material applications of nanocellulose. Processes 2019, 7, 10–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dou, C.; Pal, L.; Hubbe, M.A. Review of electrically conductive composites and films containing cellulosic fibers or nanocellulose. BioResources 2019, 14, 7494–7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mekonnen, T.H. Cellulose nanocrystals enabled sustainable polycaprolactone based shape memory polyurethane bionanocomposites. J.Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 611, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinra, S.; Pal, R. Rheology of Pickering emulsions stabilized and thickened by cellulose nanocrystals over broad ranges of oil and nanocrystal concentrations. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei-Sabet, S.; Hamad, W.Y.; Hatzikiriakos, S.G. Rheology of nanocrystalline cellulose aqueous suspensions. Langmuir 2012, 28, 17124–17133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadar, R.; Fazilati, M.; Nypelo, T. Unexpected microphase transitions in flow towards nematic order of cellulose nanocrystals. Cellulose 2020, 27, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignon, F.; Challamel, M.; De Geyer, A.; Elchamaa, M.; Semeraro, E.F.; Hengl, N.; Jean, B.; Putaux, J.; Gicquel, E.; Bras, J.; Prevost, S.; Sztucki, M.; Narayanan, T.; Djeridi, H. Breakdown and buildup mechanisms of cellulose nanocrystal suspensions under shear and upon relaxation probed by SAXS and SALS. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 260, 117751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Meng, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Fu, S.; Ma, L.; Harper, D. Rheological behavior of cellulose nanocrystal suspension: influence of concentration and aspect ratio. J. Appl. Poly. Sci. 2014, 131, 40525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.N. Effect of pH on the aggregation behavior of cellulose nanocrystals in aqueous medium. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 125078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

AFM image of NCC [

32].

Figure 1.

AFM image of NCC [

32].

Figure 2.

Rheological behavior of CMC polymer solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 2.

Rheological behavior of CMC polymer solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 3.

Rheological behavior of NCC-CMC mixtures at a fixed CMC concentration of 0.35 wt%.

Figure 3.

Rheological behavior of NCC-CMC mixtures at a fixed CMC concentration of 0.35 wt%.

Figure 4.

Rheological behavior of NCC-CMC mixtures at a fixed CMC concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 4.

Rheological behavior of NCC-CMC mixtures at a fixed CMC concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 5.

Rheological behavior of NCC-CMC mixtures at a fixed CMC concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 5.

Rheological behavior of NCC-CMC mixtures at a fixed CMC concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 6.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-CMC mixtures at different CMC concentrations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-CMC mixtures at different CMC concentrations.

Figure 7.

Images of samples of NCC-CMC mixtures.

Figure 7.

Images of samples of NCC-CMC mixtures.

Figure 8.

Rheological behavior of guar gum solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 8.

Rheological behavior of guar gum solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 9.

Rheological behavior of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at a fixed Guar Gum concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 9.

Rheological behavior of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at a fixed Guar Gum concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 10.

Rheological behavior of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at a fixed Guar Gum concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 10.

Rheological behavior of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at a fixed Guar Gum concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 11.

Rheological behavior of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at a fixed Guar Gum concentration of 1 wt%.

Figure 11.

Rheological behavior of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at a fixed Guar Gum concentration of 1 wt%.

Figure 12.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at different Guar Gum concentrations.

Figure 12.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures at different Guar Gum concentrations.

Figure 13.

Images of samples of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures.

Figure 13.

Images of samples of NCC-Guar Gum mixtures.

Figure 14.

Rheological behavior of WSR-303 solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 14.

Rheological behavior of WSR-303 solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 15.

Rheological behavior of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 15.

Rheological behavior of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 16.

Rheological behavior of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 16.

Rheological behavior of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 17.

Rheological behavior of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 1 wt%.

Figure 17.

Rheological behavior of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 1 wt%.

Figure 18.

Consistency index () and flow behavior index () of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 1.5 wt%.

Figure 18.

Consistency index () and flow behavior index () of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at a fixed WSR-303 concentration of 1.5 wt%.

Figure 19.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at different concentrations of WSR-303.

Figure 19.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-WSR-303 mixtures at different concentrations of WSR-303.

Figure 20.

Rheological behavior of Xanthan gum solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 20.

Rheological behavior of Xanthan gum solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 21.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Xanthan gum mixtures at different concentrations of Xanthan gum.

Figure 21.

Comparison of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Xanthan gum mixtures at different concentrations of Xanthan gum.

Figure 22.

Rheological behavior of Praestol 2505 polymer solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 22.

Rheological behavior of Praestol 2505 polymer solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 23.

Variations of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Praestol 2505 mixtures with NCC concentration at Praestol 2505 concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 23.

Variations of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Praestol 2505 mixtures with NCC concentration at Praestol 2505 concentration of 0.5 wt%.

Figure 24.

Variations of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Praestol 2505 mixtures with NCC concentration at Praestol 2505 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 24.

Variations of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-Praestol 2505 mixtures with NCC concentration at Praestol 2505 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 25.

Rheological behavior of JR-400 polymer solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 25.

Rheological behavior of JR-400 polymer solutions without any NCC addition.

Figure 26.

Variations of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-JR-400 mixtures with NCC concentration at JR-400 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 26.

Variations of consistency index and flow behavior index of NCC-JR-400 mixtures with NCC concentration at JR-400 concentration of 0.75 wt%.

Figure 27.

Phase separation in JR-400-NCC mixture. The JR-400 concentration is 0.75 wt% and NCC concentration is 3 wt%.

Figure 27.

Phase separation in JR-400-NCC mixture. The JR-400 concentration is 0.75 wt% and NCC concentration is 3 wt%.

Figure 28.

Three-dimensional network structure of nanocrystal aggregates and polymer macromolecules.

Figure 28.

Three-dimensional network structure of nanocrystal aggregates and polymer macromolecules.

Figure 29.

Possible interactions between cellulose nanocrystals (NCC) and polymer chains resulting in a decrease in the consistency of NCC-polymer mixtures.

Figure 29.

Possible interactions between cellulose nanocrystals (NCC) and polymer chains resulting in a decrease in the consistency of NCC-polymer mixtures.

Figure 30.

Free NCC aggregates and NCC-polymer aggregates present in NCC-polymer mixtures.

Figure 30.

Free NCC aggregates and NCC-polymer aggregates present in NCC-polymer mixtures.

Table 1.

Different polymers investigated in this work

Table 1.

Different polymers investigated in this work

| Trade name |

Chemical name, polymer type (ionic or non-ionic), and structure |

Industrial uses |

| Hercules Cellulose Gum, manufactured by Hercules Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA |

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). It is an anionic water- soluble polymer.

|

It is used as a thickener, stabilizer, emulsifier, and water retention agent in food products. It is also used as a drug carrier, binder, film-forming material in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. It is used in drilling fluids and as an anti-coagulant in paper and textile industries. It is also used as a detergent, flocculant, and chelating agent in various industries. In oil and mining industries, it is used as a flotation agent. |

| Guar Gum, supplied by Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada |

Galactomannan polysaccharide. It is a non-ionic water-soluble polymer.

|

It is a gel-forming agent that can be used for thickening cold and hot liquids, making cottage cheeses, curds, yoghurt, sauces, soups, frozen desserts, providing soluble dietary fiber, stabilizing emulsions. It is also used in dairy products, condiments, baked goods, and non-food products. |

| Polyox WSR-303, ChemPoint, Bellevue, WA, USA |

Polyethylene oxide. It is a non-ionic water-soluble polymer.

|

High molecular weight thickener and binder. It is also used as a film former, lubricant, and retention aid. It is used in the manufacturing of ceramics, building and construction materials, lubricants, papermaking, and electronics materials. |

| Kelzan, manufactured by CP Kelco, Atlanta, GA, USA |

Xanthan gum polysaccharide. It is an anionic water-soluble polymer.

|

It is a common food additive. It is used as a thickening agent in toothpaste and other industrial products. It improves texture and consistency in ice cream, salad dressings, and baked goods. |

Praestol 2505, manufacured by Stcokhausen Inc., Krefeld, Germany.

|

Polyacrylamide. It is an anionic water-soluble polymer.

|

It is a flocculant used in many applications such as dewatering sludges, treating municipal wastewater, and clarifying raw or surface water for drinking water production. |

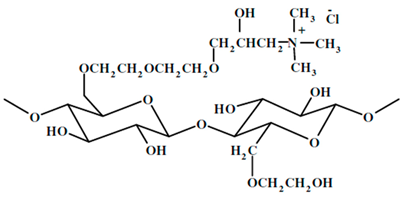

| UCARE polymer JR-400, manufactured by Dow chemical company, Midland, Michigan, USA |

Quaternary ammonium salt of hydroxyethyl cellulose. It is a cationic water- soluble polymer. The structure of the repeat unit is as follows:

|

It is used extensively in the preparation of hair and skin care products such as: shampoos, conditioners, body washes, facial cleansers, liquid and bar soaps, moisturizers. |

Table 2.

Relevant dimensions of viscometers used in this study.

Table 2.

Relevant dimensions of viscometers used in this study.

| Viscometer |

|

|

Length of inner cylinder |

Gap-width |

| Fann 35A/SR-12 (low torsion spring constant) |

1.72 cm |

1.84 cm |

3.8 cm |

0.12 cm |

| Fann 35A (high torsion spring constant) |

1.72 cm |

1.84 cm |

3.8 cm |

0.12 cm |

| Haake Roto- visco RV 12 with MV I |

2.00 cm |

2.1 cm |

6.0 cm |

0.10 cm |

| Haake Roto- visco RV 12 with MV II |

1.84 cm |

2.1 cm |

6.0 cm |

0.26 cm |

| Haake Roto- visco RV 12 with MV III |

1.52 cm |

2.1 cm |

6.0 cm |

0.58 cm |

Table 3.

Summary of interactions between NCC and polymer.

Table 3.

Summary of interactions between NCC and polymer.

| Polymer |

NCC-Polymer combination. The sign of electric charge is indicated as superscript. |

Comments |

| Anionic (CMC) |

NCC- P-

|

Strong interaction observed between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals and anionic polymer. The consistency index increases sharply with the addition of NCC to CMC solution indicating that the addition of NCC makes the solution much more viscous and thicker. The flow behavior index decreases sharply with the addition of NCC to CMC solution indicating an increase in the degree of shear-thinning. The images of NCC-CMC mixtures show gel-type material at high NCC concentrations. |

| Non-ionic (Guar Gum) |

NCC- P0

|

Strong interaction observed between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals and non-ionic polymer. The consistency index increases substantially and the flow behavior index decreases significantly with the addition of NCC to guar gum solution. However, the changes observed in consistency index and flow behavior index with the addition of NCC in NCC-Guar gum mixtures are less severe as compared with the changes observed in NCC-CMC mixtures. |

| Non-ionic (WSR-303) |

NCC- P0

|

Moderate interaction observed between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals and non-ionic polymer. At low polymer concentrations, the consistency index increases upon addition of NCC. At high polymer concentrations, the consistany index goes through a minimum, that is, it decreases intitially and then rises with the addition of NCC. |

| Anionic (Xanthan Gum) |

NCC- P-

|

Weak interaction observed between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals and anionic polymer based on consistency index data; consistency index remains nearly constant upon addition of NCC to polymer solution. |

| Anionic (Praestol 2505) |

NCC- P-

|

Weak interaction observed between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals and anionic polymer. The addition of NCC to polymer has negligible effect on consistency index. |

| Cationic (JR-400) |

NCC- P+

|

Weak interaction observed between negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals and cationic polymer. The addition of NCC to polymer has negligible effect on consistency index. Precipitation of nanocrystals occurs at high concentration of NCC. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).