Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Presenting a dataset that includes previously undefined movements in the field of basketball.

- Comparing high-performance feature extraction and machine learning methods aimed at action recognition in basketball.

- Offering a high-performance, low-cost action recognition system for the basketball field with fewer sensors.

- Integration of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to action recognition model.

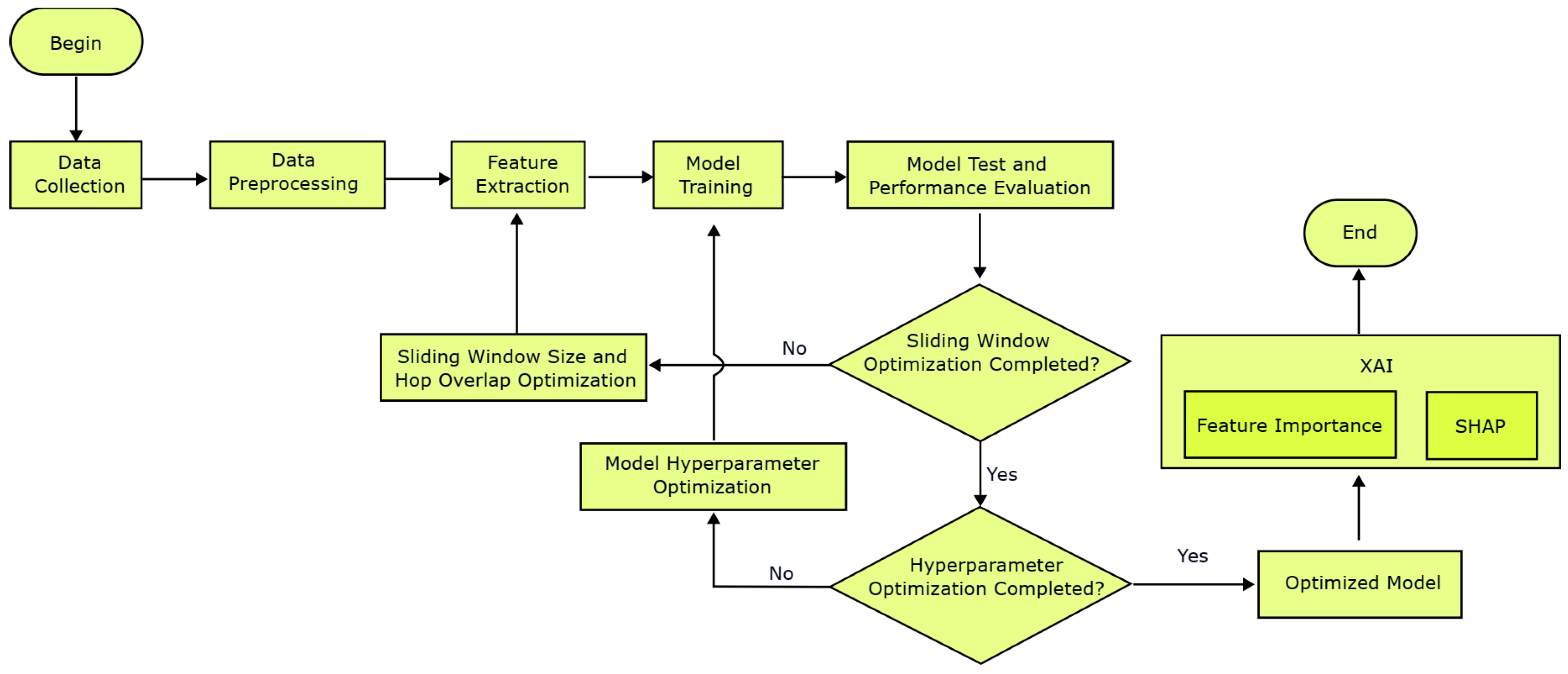

2. Materials and Methods

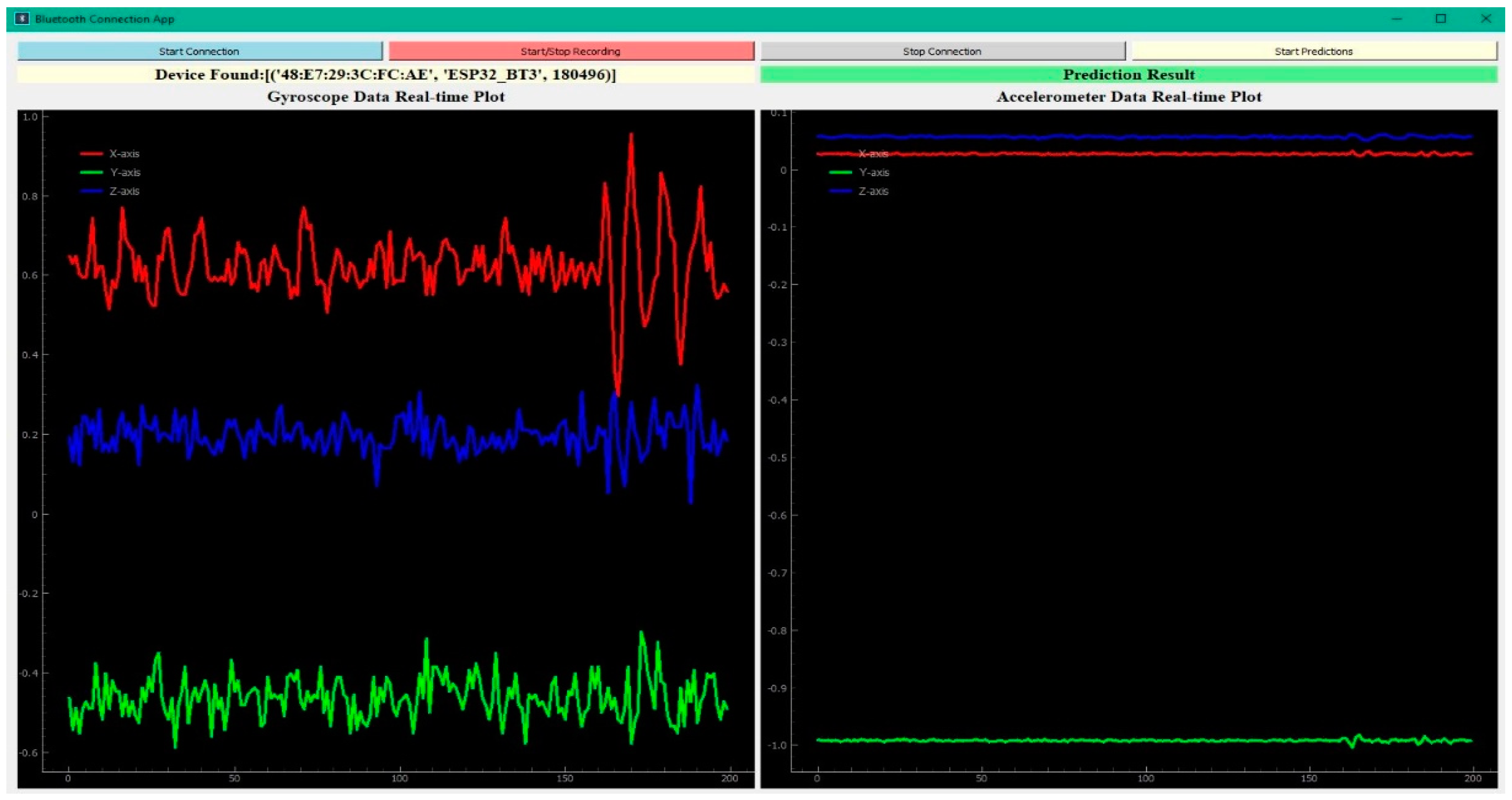

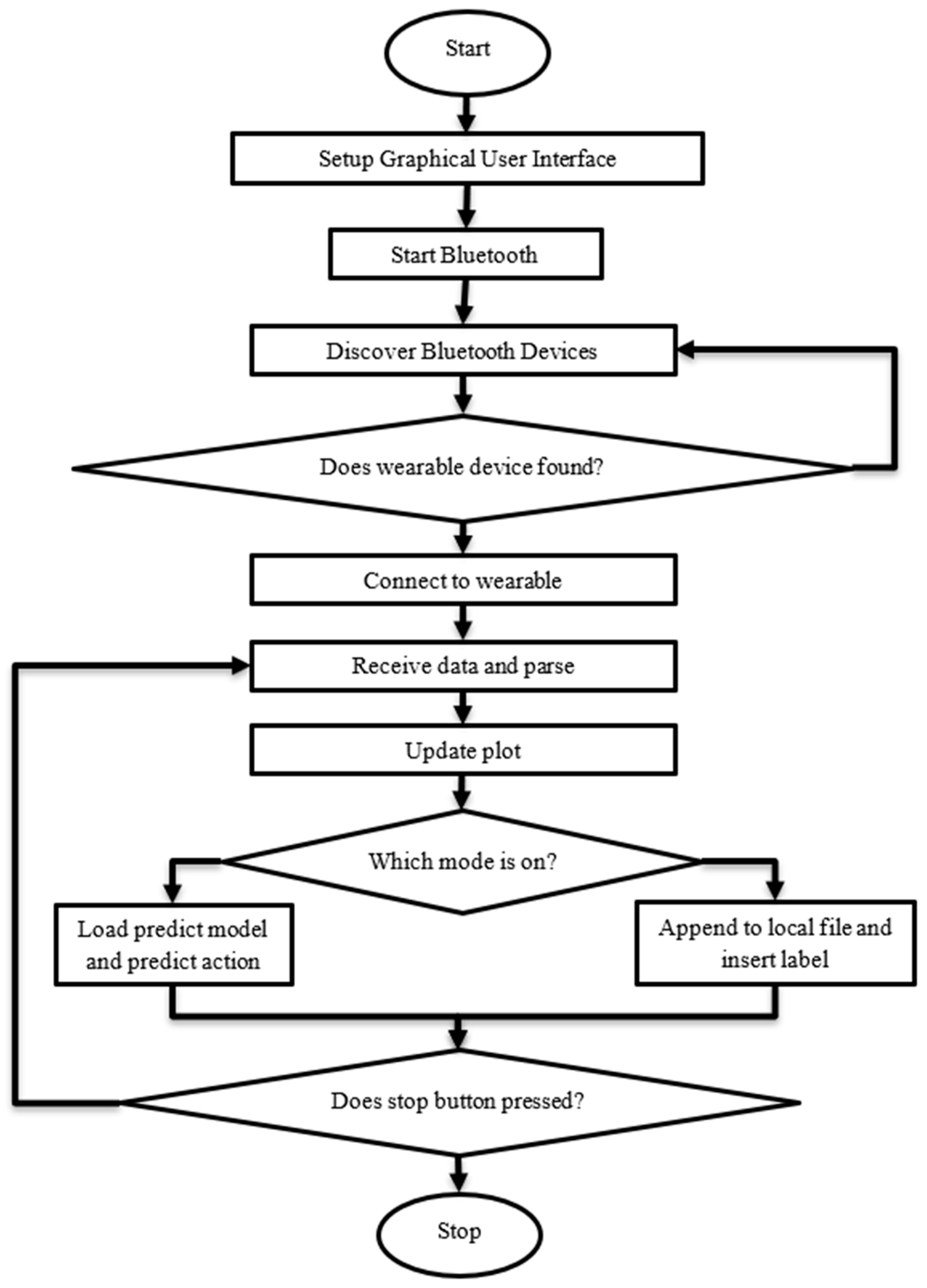

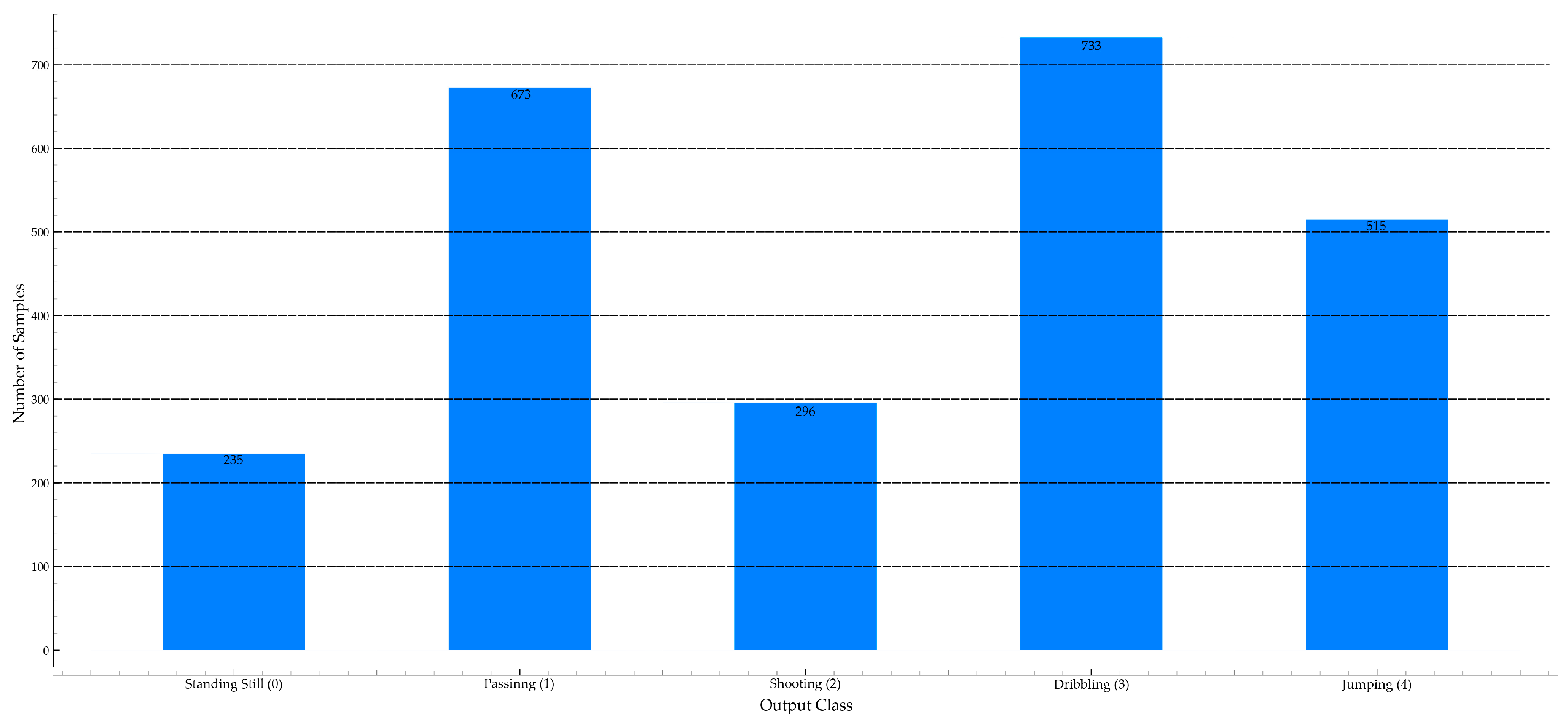

2.1. Data Collection and Labeling

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

2.3. Model Training and Test

2.3.1. K-Fold Cross Validation and Model Selection

2.3.2. Leave One Subject Out Cross Validation

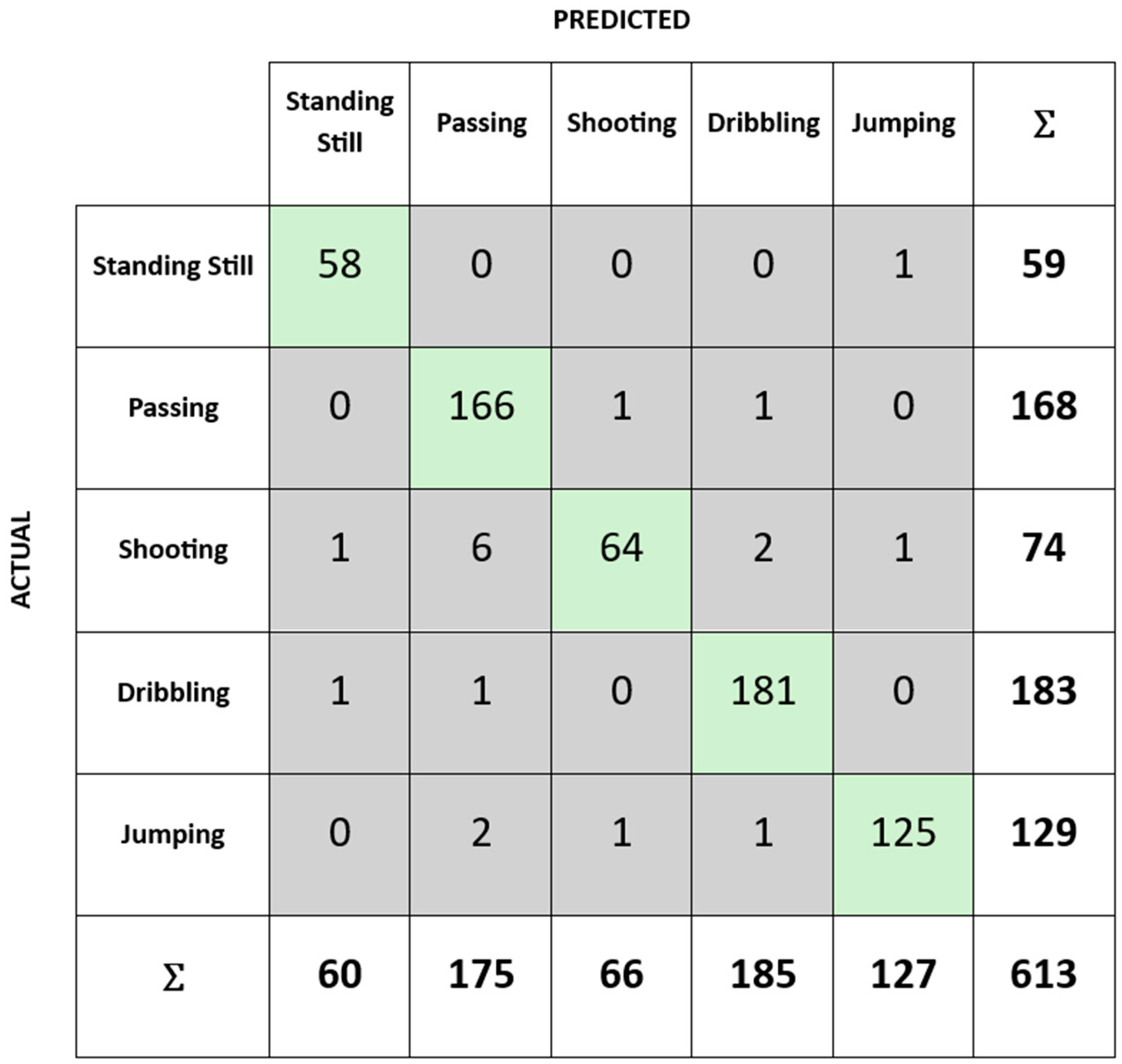

- Data Partitioning: For each iteration, data from one subject was completely withheld from the training set and used exclusively for testing. This process was repeated for all 21 subjects in the dataset, ensuring each subject served as the test set exactly once.

- Model Training: The selected learning algorithm was trained on the data from the remaining 20 subjects, utilizing the optimized hyperparameters identified in prior experiments.

- Evaluation: The trained model was then applied to the withheld subject's data to generate predictions. Performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were computed for each iteration.

- Aggregation: The final performance metrics were calculated by averaging the results across all iterations.

2.4. Action Classification Performance Metrics

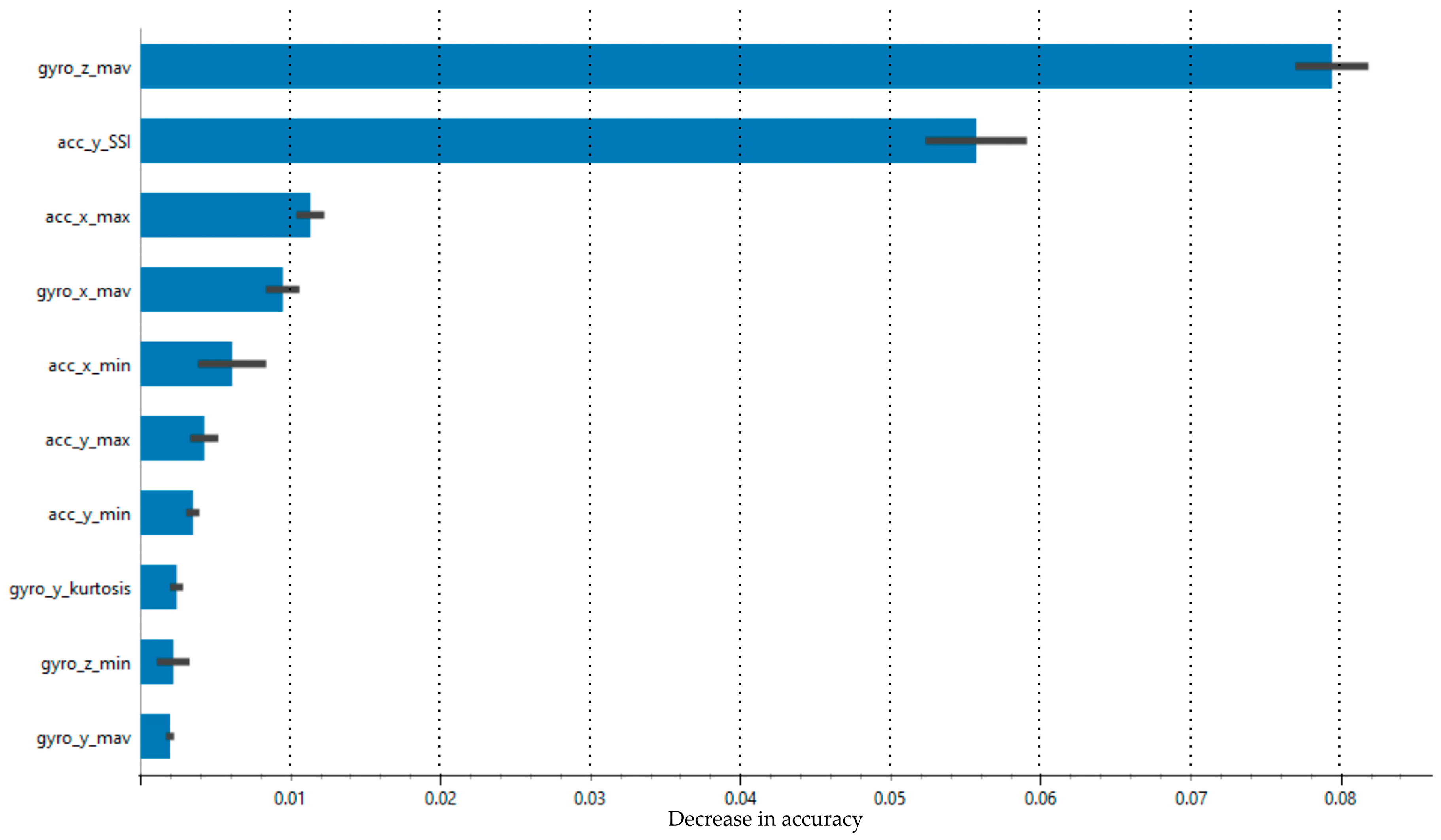

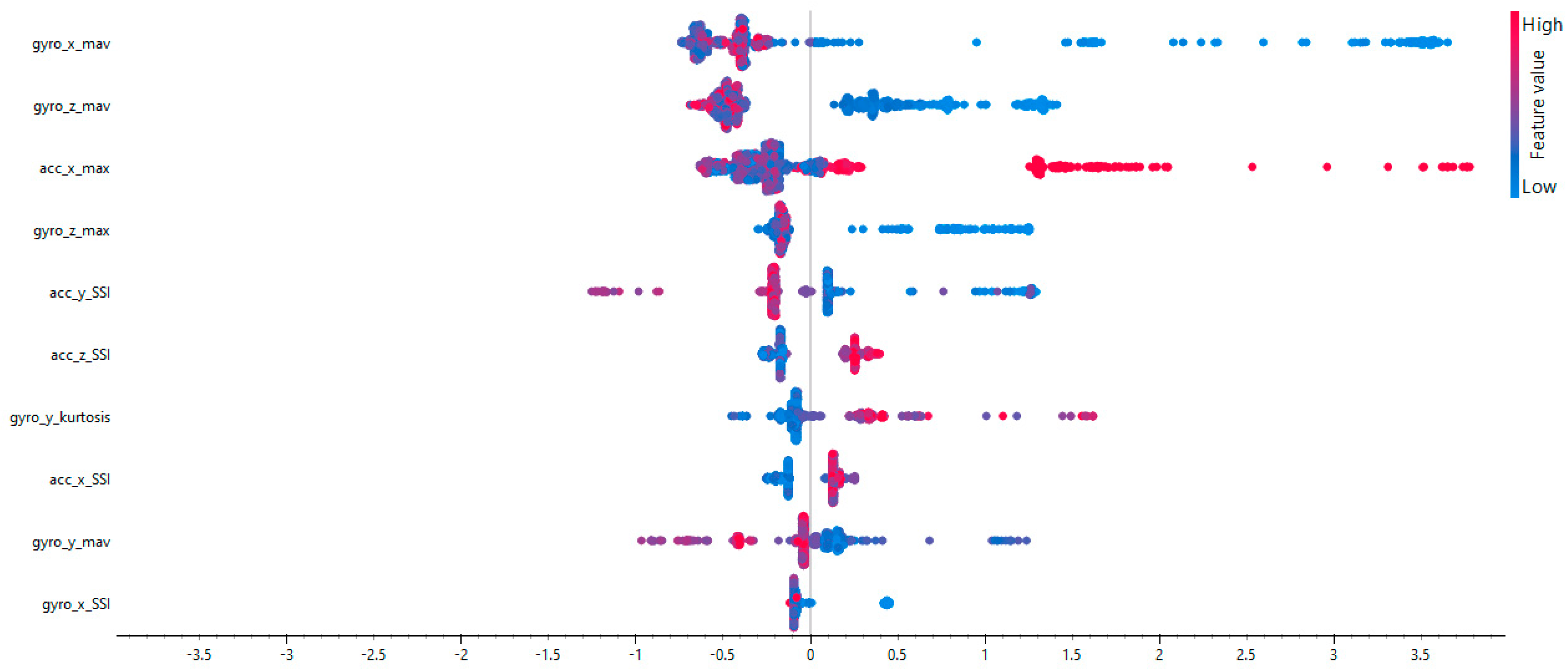

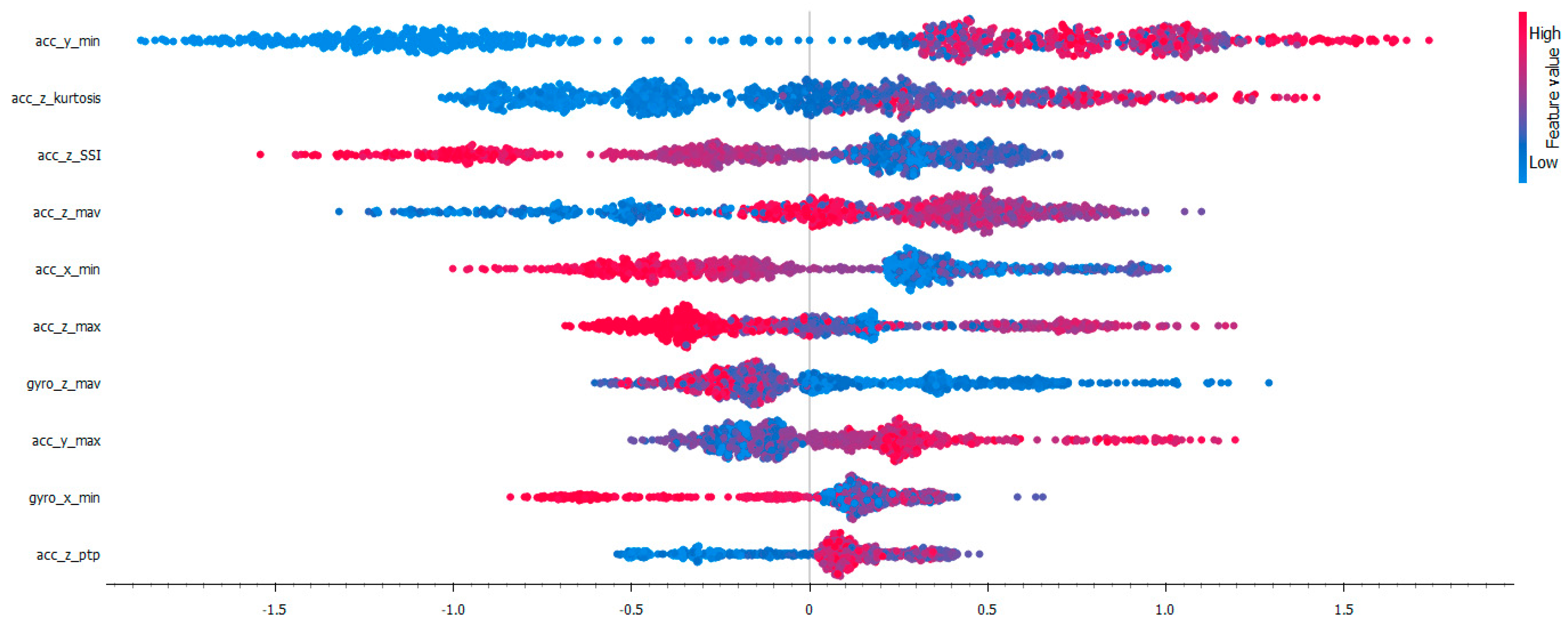

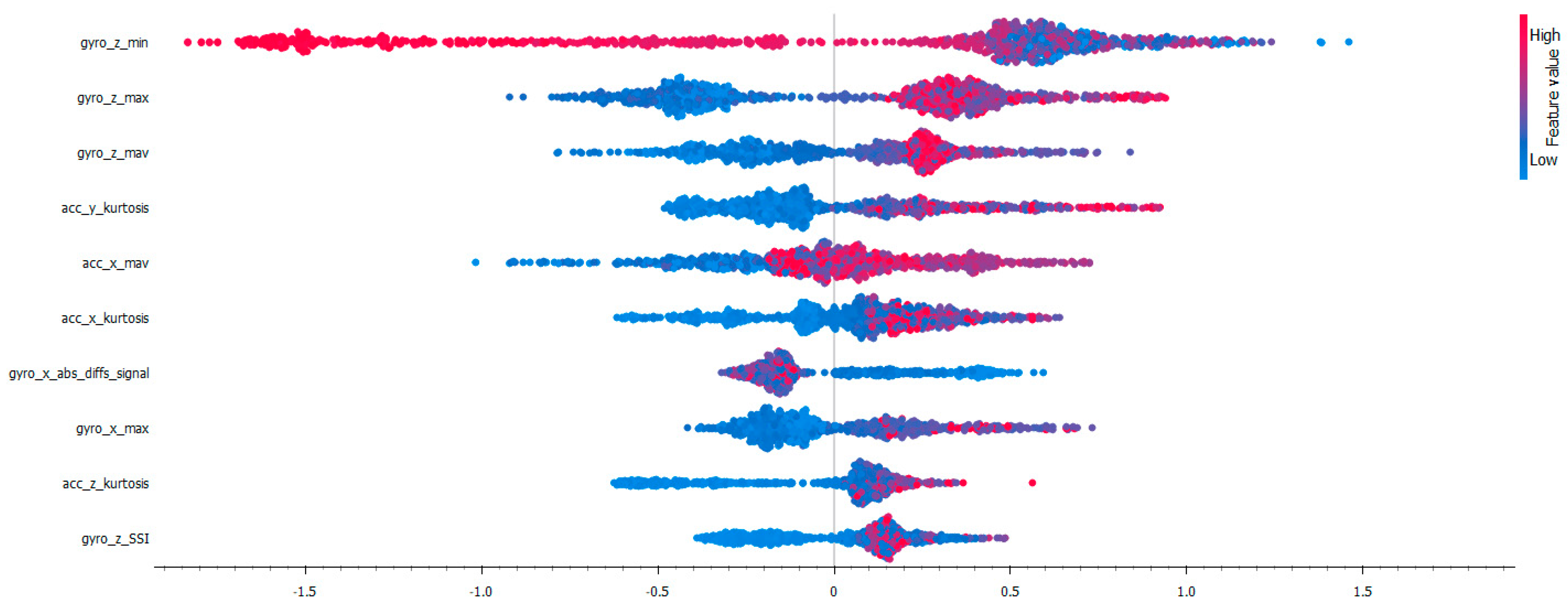

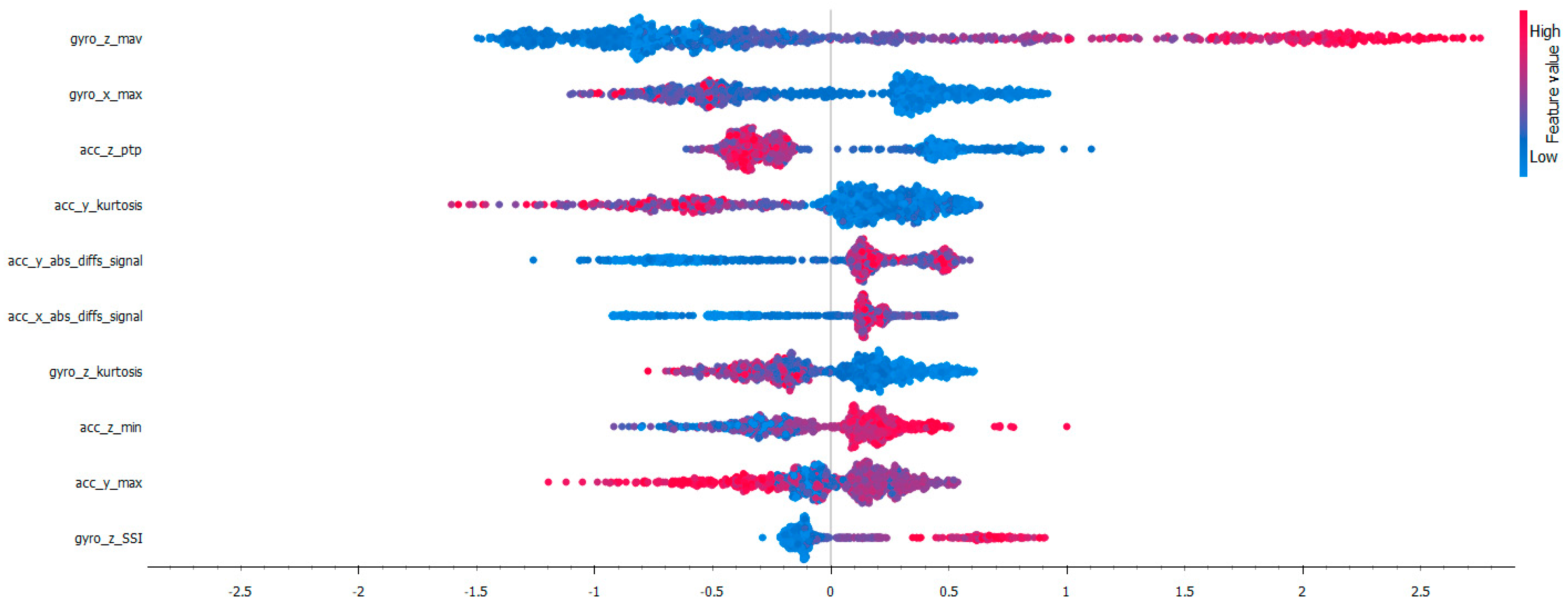

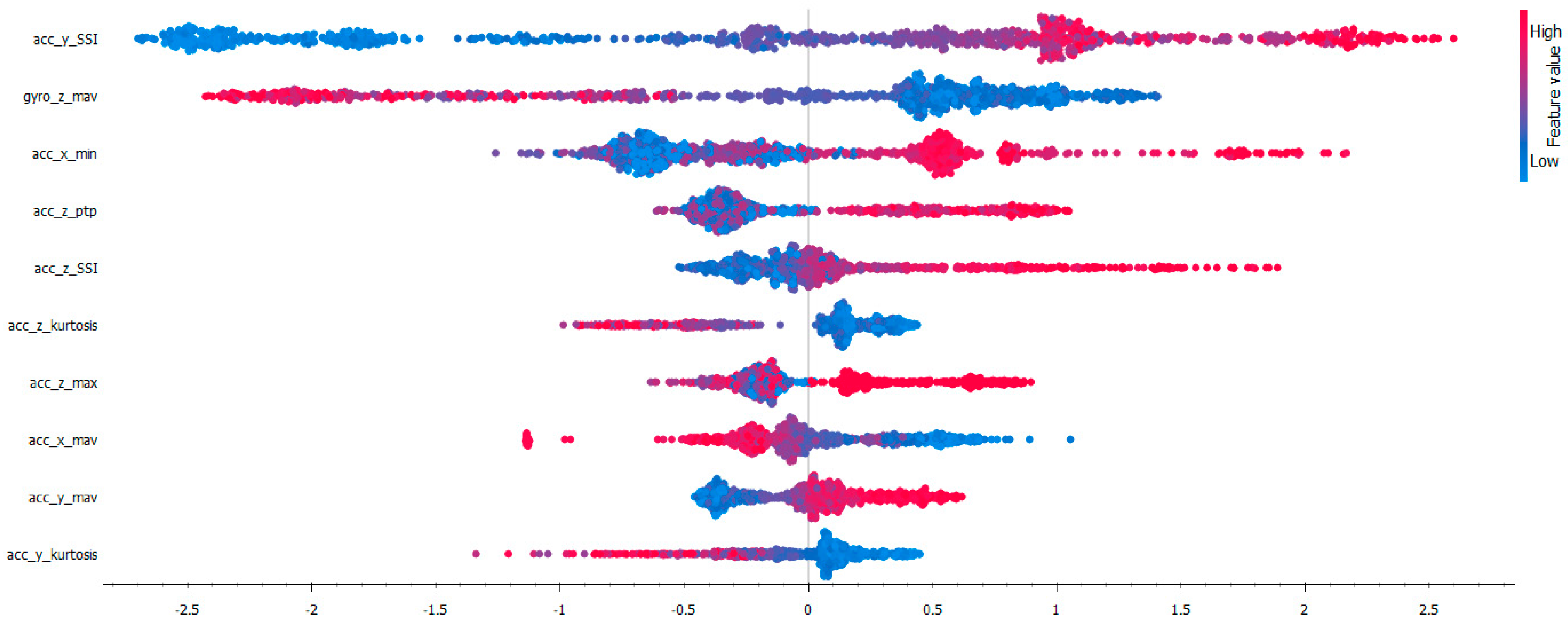

2.5. Optimized Model Explantion

- Model Training: A machine learning model is trained on the dataset, capturing the relationships between input features and the output.

- Shapley Value Calculation: For each prediction, SHAP computes Shapley values, which quantify the contribution of each feature by considering all possible combinations of features. The Shapley value ϕi for a feature i is calculated using the equation (1). In this equation N is the set of all features, S is a subset of features that does not include feature i, f(S) is the model’s prediction when only the features in subset S are included. f(S∪{i}) is the prediction when feature I is added to subset S.

- Feature Attribution: The calculated Shapley values are used to assign importance scores to each feature, indicating their influence on the model's output.

- Visualization: The results can be visualized using various plots to facilitate understanding of feature impacts on predictions

3. Results And Discussion

3.1. Model Selection with Sliding Window and Hyperparameter Optimization

3.2. Comparison with Related Works

4. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schack, T.; Bar-Eli, M. Psychological Factors of Technical Preparation. In Psychology of sport training; Meyer & Meyer Verlag, 2007; Volume 2, pp. 62–103. ISBN 978-1-84126-202-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chicomban, M. A Fundamental Component of Sports Training in The Basketball Game. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov• Vol 2009, 2, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, E.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Williams, A.M.; Tavares, F.; Janeira, M.A.; Maia, J. Modelling the Dynamics of Change in the Technical Skills of Young Basketball Players: The INEX Study. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0257767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D. Analysis of Influencing Factors and Development Trends of College Basketball Teaching Reform. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Education Science and Economic Development (ICESED 2019); Atlantis Press; 2020; pp. 288–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, S.R.; Dimick, K.M. Career Maturity and Professional Sports Expectations of College Football and Basketball Players. Journal of College Student Personnel 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, J.D.; Merrigan, J.J.; Ramadan, J.; Brown, R.S.; Cheng, G.T.; Hornsby, W.G.; Smith, H.; Galster, S.M.; Hagen, J.A. Simplifying External Load Data in NCAA Division-I Men’s Basketball Competitions: A Principal Component Analysis. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçkin, A.Ç.; Ateş, B.; Seçkin, M. Review on Wearable Technology in Sports: Concepts, Challenges and Opportunities. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lv, Q.; Zeng, X. Application of Wearable Sensors Based on Infrared Optical Imaging in Mobile Image Processing in Basketball Teaching. Opt Quant Electron 2024, 56, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.; Ma, R.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Sha, X.; Li, W.J. ANN-Enhanced IoT Wristband for Recognition of Player Identity and Shot Types Based on Basketball Shooting Motion Analysis. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.; Guo, X. Wearable Ultraviolet Sensor Based on Convolutional Neural Network Image Processing Method. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2022, 338, 113402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoareau, D.; Jodin, G.; Chantal, P.-A.; Bretin, S.; Prioux, J.; Razan, F. Synthetized Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) to Evaluate the Placement of Wearable Sensors on Human Body for Motion Recognition. The Journal of Engineering 2022, 2022, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R. Research on Basketball Shooting Action Based on Image Feature Extraction and Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 138743–138751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wang, X. Application of Wearable Inertial Sensor in Optimization of Basketball Player’s Human Motion Tracking Method. J Ambient Intell Human Comput 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehzangi, O.; Taherisadr, M.; ChangalVala, R. IMU-Based Gait Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Multi-Sensor Fusion. Sensors 2017, 17, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzemann, A.; Van Laerhoven, K. Using Wrist-Worn Activity Recognition for Basketball Game Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Sensor-based Activity Recognition and Interaction; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, September 20, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, G.B.; Dowling, B.; Troje, N.F.; Fischer, S.L.; Graham, R.B. Classifying Elite From Novice Athletes Using Simulated Wearable Sensor Data. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Mo, S.; Qu, X. Basketball Activity Classification Based on Upper Body Kinematics and Dynamic Time Warping. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 41, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggert, B.; Mundt, M.; Markert, B. IMU-Based Activity Recognition of the Basketball Jump Shot. ISBS Proceedings Archive 2020, 38, 344. [Google Scholar]

- Asmara, R.A.; Hendrawan, N.D.; Handayani, A.N.; Arai, K. Basketball Activity Recognition Using Supervised Machine Learning Implemented on Tizen OS Smartwatch. Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Elektro Komputer dan Informatika (JITEKI) 2022, 8, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, W. Basketball Motion Posture Recognition Based on Recurrent Deep Learning Model. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022, 2022, 8314777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzemann, A.; Romero, J.L.; Bock, M.; Laerhoven, K.V.; Lv, Q. Hang-Time HAR: A Benchmark Dataset for Basketball Activity Recognition Using Wrist-Worn Inertial Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, D. Deep Learning Algorithm Based Wearable Device for Basketball Stance Recognition in Basketball. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yan, D.; Peng, H.; Yang, T.; Sha, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L. Basketball Movements Recognition Using a Wrist Wearable Inertial Measurement Unit. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 1st International Conference on Micro/Nano Sensors for AI, Healthcare, and Robotics (NSENS); December 2018; pp. 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Gu, D. Research on Basketball Players’ Action Recognition Based on Interactive System and Machine Learning. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2021, 40, 2029–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, B.; Oberhofer, K.; Lorenzetti, S. Introducing a Time-Efficient Workflow for Processing IMU Data to Identify Sport-Specific Movement Patterns. Current Issues in Sport Science (CISS) 2023, 8, 060–060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ni, Z. Action Recognition Method of Basketball Training Based on Big Data Technology. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, J.A.; Zwart, A.S.; Perez, P.S.; Gurchiek, R.D.; McBride, J.M. Effect of IMU Location on Estimation of Vertical Ground Reaction Force during Jumping. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, M.H.; Berkvens, R.; Weyn, M. Chest-Worn Inertial Sensors: A Survey of Applications and Methods. Sensors 2021, 21, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, E.W.; Doyle, T.L.A.; Bonacci, J.; Fuller, J.T. Sensor Location Influences the Associations between IMU and Motion Capture Measurements of Impact Landing in Healthy Male and Female Runners at Multiple Running Speeds. Sports Biomechanics 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H.; Baskett, F.; Shustek, L.J. An Algorithm for Finding Nearest Neighbors. IEEE Transactions on Computers 1975, C–24, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of Decision Trees. Mach Learn 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, A.A.; Movahedi, N.; Ghorbani, K.; Eslamian, S. Decision Tree Algorithms. In Handbook of Hydroinformatics; Eslamian, S., Eslamian, F., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 171–187. ISBN 978-0-12-821285-1. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A Random Forest Guided Tour. TEST 2016, 25, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Desicion-Theoretic Generalization of on-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. In Proceedings of the Computational Learning Theory; Vitányi, P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1995; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Favaro, P.; Vedaldi, A. AdaBoost. In Computer Vision: A Reference Guide; Ikeuchi, K., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2014; pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-0-387-31439-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; pp. 132016785–794.

- Gholamiangonabadi, D.; Kiselov, N.; Grolinger, K. Deep Neural Networks for Human Activity Recognition With Wearable Sensors: Leave-One-Subject-Out Cross-Validation for Model Selection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 133982–133994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, A.; Glatard, T.; Shihab, E. Subject Cross Validation in Human Activity Recognition 2019.

- Bhuyan, B.P.; Srivastava, S. Feature Importance in Explainable AI for Expounding Black Box Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of International Conference on Data Science and Applications; Saraswat, M., Chowdhury, C., Kumar Mandal, C., Gandomi, A.H., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Katayama, T.; Takahashi, K.; Shimomura, Y.; Takizawa, H. XAI-Based Feature Importance Analysis on Loop Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium Workshops (IPDPSW); May 2024; pp. 782–791. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. The Analysis and Development of an XAI Process on Feature Contribution Explanation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); December 2022; pp. 5039–5048. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, T.; Chophuk, P.; Chinnasarn, K. Evolving Feature Selection: Synergistic Backward and Forward Deletion Method Utilizing Global Feature Importance. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88696–88714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Galazzo, I.B.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Lekadir, K.; Menegaz, G. A Perspective on Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods: SHAP and LIME. Advanced Intelligent Systems n/a 2024, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Shi, Z.; Yao, W.; Zhou, R.; Luo, F.; Wen, J. SHAP Algorithm for Transparent Power System Transient Stability Assessment: Critical Impact Factors Identification. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power System Technology (PowerCon); September 2023; pp. 01–06. [Google Scholar]

- Lellep, M.; Prexl, J.; Eckhardt, B.; Linkmann, M. Interpreted Machine Learning in Fluid Dynamics: Explaining Relaminarisation Events in Wall-Bounded Shear Flows. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2022, 942, A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X. Machine Learning Models Using SHapley Additive exPlanation for Fire Risk Assessment Mode and Effects Analysis of Stadiums. Sensors 2023, 23, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madej, M.; Rumiński, J. Optimal Placement of IMU Sensor for the Detection of Children Activity. In Proceedings of the 2022 15th International Conference on Human System Interaction (HSI); July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, M. Estimation of Vertical Jump Height Based on IMU Sensor. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics (ICCAR); April 2022; pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Name | Variable Abbreviation | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum | min | Min(x)=min(x1, x2,...xn) |

| Maximum | max | Max(x)=max(x1, x2,...xn) |

| Peak to Peak | ptp | PP(x)= max(x1, x2,...xn)- min(x1,x2,...xn) |

| Simple Square Integral | SSI | |

| Root Mean Square | rms | |

| Absolute Differences | abs_diffs_signal | |

| Mean Absolute | mav | |

| Skewness | skewness | |

| Kurtosis | kurtosis |

| Metric | Equation |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | |

| Precision | |

| Recall | |

| F1-Score |

| Window Size | Window Hop Overlap Percentage | KNN | DT | RF | AdaBoost | XGBosst |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 75 | 0.629 | 0.857 | 0.931 | 0.411 | 0.957 |

| 100 | 50 | 0.597 | 0.774 | 0.858 | 0.432 | 0.877 |

| 100 | 25 | 0.591 | 0.771 | 0.854 | 0.521 | 0.878 |

| 100 | 0 | 0.601 | 0.764 | 0.899 | 0.448 | 0.896 |

| 150 | 75 | 0.688 | 0.872 | 0.932 | 0.435 | 0.965 |

| 150 | 50 | 0.633 | 0.815 | 0.901 | 0.529 | 0.93 |

| 150 | 25 | 0.593 | 0.802 | 0.837 | 0.663 | 0.864 |

| 150 | 0 | 0.62 | 0.755 | 0.844 | 0.484 | 0.865 |

| 200 | 75 | 0.675 | 0.873 | 0.924 | 0.483 | 0.958 |

| 200 | 50 | 0.688 | 0.84 | 0.948 | 0.573 | 0.962 |

| 200 | 25 | 0.609 | 0.823 | 0.891 | 0.484 | 0.88 |

| 200 | 0 | 0.639 | 0.722 | 0.875 | 0.306 | 0.882 |

| 250 | 75 | 0.727 | 0.897 | 0.957 | 0.492 | 0.966 |

| 250 | 50 | 0.701 | 0.879 | 0.922 | 0.554 | 0.935 |

| 250 | 25 | 0.61 | 0.838 | 0.922 | 0.519 | 0.922 |

| 250 | 0 | 0.647 | 0.828 | 0.879 | 0.517 | 0.914 |

| Hyperparameter | Value | Median | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Estimators | 100 | 0.941 | 0.925 | 0.949 |

| 150 | 0.951 | 0.933 | 0.957 | |

| 200 | 0.955 | 0.935 | 0.961 | |

| Learning Rate | 0.01 | 0.919 | 0.902 | 0.929 |

| 0.05 | 0.947 | 0.943 | 0.955 | |

| 0.1 | 0.959 | 0.955 | 0.961 | |

| Maximum Depth | 3 | 0.941 | 0.902 | 0.949 |

| 4 | 0.949 | 0.921 | 0.957 | |

| 5 | 0.955 | 0.937 | 0.959 | |

| Minimum Child Weight | 1 | 0.947 | 0.929 | 0.959 |

| 2 | 0.945 | 0.931 | 0.957 | |

| 3 | 0.945 | 0.927 | 0.955 | |

| Subsample | 0.6 | 0.945 | 0.925 | 0.957 |

| 0.7 | 0.947 | 0.931 | 0.959 | |

| 0.8 | 0.945 | 0.929 | 0.957 |

| Reference | Number of Wearable and Placement | Actions | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | 5 sensors worn to back, lower legs and feet | Player Identity, Shot Types | Accuracy:0.985 |

| [15] | 1 sensor worn to wrist | Dribbling, Shooting, Blocking, Passing | Accuracy: 0.875 |

| [16] | 1 sensor worn to wrist, foot, waist | Player Level Classification | Accuracy: 0.847 |

| [17] | 39 sensors worn to upper body | Shooting, Passing, Dribbling, Lay-up | Precision: 0.984Recall: 0.983Specificity: 0.994 |

| [18] | 4 sensors worn to foot opposite to the shooting hand, lower back, upper back, shooting hand | 34 different exercises | Recall:0.975 Precision: 0.980 |

| [19] | 2 sensors worn to wrists | Low Dribbling, Crossover Dribbling, High Dribbling, Jump Shot | Accuracy: 0.816 |

| [20] | 2 sensors worn to wrist, foot, waist | Various Basketball Movements | Accuracy: 0.993 |

| [21] | 1 sensor worn to wrist | Dribbling, shot, pass, rebound, layup, walking, running, standing, sitting | F1-score: 0.24 |

| [22] | 1 sensor worn to wrist | Basketball Stances | Accuracy:0.994 |

| Purposed System | 1 sensor worn to back | Dribbling, Shooting, Passing, Lay-up, idle | Accuracy: 0.969 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).