1. Introduction

The area dedicated to horticultural crops in India has significantly expanded over the past few decades.

Punica granatum L., commonly known as Pomegranate, stands out as an ancient fruit crop often referred to as the "fruit of paradise" in Arabic and Hebrew [

1]. Its cultivation dates back to early historical periods, reflecting its rich heritage (Indian Council of Agricultural Research, 2015). "Pomegranate" derives from the ancient Egyptian word ‘Arhu-mani.’ The Romans originally referred to the fruit as "

Malum punicum" (punic apple or apple of Carthage), a name later formalized by Carl Linnaeus as

Punica granatum. Approximately 90% of the world's Pomegranate plantations are centered in Asia and Europe, with North Africa contributing 9% and North America less than 1% [

2]. In the Indian peninsular region, the cultivation of Pomegranate has spread extensively due to high demand and export potential, as well as favorable climatic conditions in arid and semi-arid provinces, especially in the Deccan Plateau, which includes Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu [

3]. Maharashtra, which contributes over 70% of India's Pomegranate cultivation area, is renowned for its Ganesh and Bhagwa varieties [

4], earning the designation of the “Pomegranate basket of India” [

5]. Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh are also notable contributors to Pomegranate production.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) recommend daily fruit consumption of 60g and 92g per person, respectively. However, the average intake is only 46g per person due to various [

6], revealing a significant gap between supply and demand. Pomegranates are rich in essential nutrients, including sugars, organic acids, polyphenols, and vitamins [

7], and they play a vital role in the treatment of conditions such as AIDS, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases [

8].

Despite its benefits, Pomegranate cultivation faces challenges, particularly from bacterial blight (BB), also known as nodal blight, black spot, oily spot, or Telya (a local name in Maharashtra) [

9]. This disease, caused by the proteobacterium

Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae, can lead to domestic demand declines and export market losses of up to 80% [

10], with yield losses ranging from 70% to 90% [

11]. Statistical reports indicate that 25% to 30% of total production costs are allocated to plant protection [

12], causing significant financial burdens that have led some farmers to uproot their crops due to unbearable losses. Hingoranii and Mehta (1952) described the symptoms of BB as irregular 2-5 mm spots on leaves and fruits, initially water-soaked and light brown, progressing to dark brown necrotic spots accompanied by chlorosis. Over time, L- or Y-shaped cracks develop on the fruit pericarp [

13]. The disease typically proliferates from June to October, peaking in September and October, before diminishing, leaving behind oily spots on fruit and leaves. Factors such as temperature, humidity, and rainfall influence disease severity, as do virulence factors like the Type III secretion system (T3SS), exopolysaccharides, extracellular enzymes, toxins, and quorum sensing signaling [

14,

15].

To mitigate bacterial blight, various conventional and contemporary methods have been explored, including the development of novel varieties through tissue culture [

16,

17], genetic modification [

18], and the application of synthetic agrochemicals, antibiotics, and pesticides. Standard chemotherapeutic agents against BB include streptocycline, Paushamycin, and combinations like streptocycline with copper oxychloride. Despite these efforts, production losses due to bacterial blight remain persistent.

The indiscriminate use of agrochemicals and antibiotics has severely impacted agricultural sustainability, leading to acute toxicity, long degradation periods, food chain accumulation, gene transfer to pathogens, ecosystem pollution, loss of genetic diversity, and reduced soil productivity [

19]. This has resulted in stringent regulations in various countries, complicating the management of plant diseases due to a scarcity of effective bactericides. Consequently, eco-friendly and cost-effective biocontrol methods are increasingly viewed as viable alternatives to support sustainable agriculture and green consumerism [

20].

Research has identified several microorganisms with antagonistic potential, including Pseudomonas sp., Rahnella aquatilis [

21], Trichoderma virida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Lactobacillus sp. that can serve as potential biocontrol agents. While certain species of Bacillus and Pseudomonas have been extensively studied for their efficacy against plant diseases, their effectiveness against bacterial blight remains limited. Therefore, there is considerable potential to explore other microorganisms with probiotic and antagonistic properties, such as lactic acid bacteria (LAB), as biocontrol agents against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae [

22].

LAB have been utilized in dairy and fermented foods since ancient times and are currently employed across various sectors due to their "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) status, as recognized by the FDA [

23]. The biocontrol potential of

Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Enterococcus, and

Pediococcus against fungal infections in Pomegranate fruits, suggesting the potential use of LAB for other plant diseases [

24]. Consequently, characterizing the antimicrobial substances produced by probiotic LABs is crucial. LAB-produced bacteriocins, which are positively charged, can interact with the negatively charged cell membranes of target pathogens through a "barrel-stave mechanism" [

25,

26], leading to membrane thinning and pore formation while preserving the integrity of the producer cells. Bacteriocins are recognized as safe, heat-tolerant, pH-stable, and exhibit a broad antimicrobial spectrum with bactericidal activity, often encoded by plasmids [

27]. Therefore, exploring eco-friendly, cost-effective biocontrol agents is essential for improving fruit production and minimizing economic losses. Despite isolating several bacteriocin-producing LABs, the search for new strains with antagonistic activity against

Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae remains crucial to expand the arsenal of available antimicrobial agents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling, Enrichment and Isolation of Lactic acid bacteria

Samples were collected aseptically from local agriculture and dairy farms, including whey, raw milk, curd, cheese, paneer, spoiled dairy products, rose inner petal whorls, and spoiled vegetables. Enrichment was carried out in sterile MRS medium by adding 1 ml (v/v) or 1 g (w/v) of sample and incubated micro-aerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. Isolation of LAB was performed as described by Reuben et al. (2019)[

28]After incubation, small, whitish, catalase and peroxidase-negative, discrete bacterial colonies were selected randomly and streaked on MRS agar to check the isolates’ purity. Isolates were preserved in MRS soft agar (0.7%) overlaid with glycerol at -20°C.

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. Punicae

Infected Pomegranate plant parts (fruit, leaf, twig) of the Ganesh variety from local orchards were aseptically collected. Surface sterilization was performed with 0.1% HgCl2 (w/v), and the samples were crushed in 2 ml sterile saline (0.85% NaCl). A 50 µl aliquot of the crushed sample was inoculated onto Glucose Nutrient Agar and incubated at 30°C for 48-72 hours [

29]. After incubation, discrete, convex, mucoid, bright yellow colonies were selected, purified, and identified using morphological and biochemical methods for further study.

2.3. Screening of Bacteriocin Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria

Isolated LAB were screened for antibacterial activity against isolated and identified

Xanthomonas axonopodis pv.

punicae (Xpp) using the agar overlay method ([

30].

2.4. Phylogenetic Identification of Promising LAB Isolate

LAB isolates were identified phylogenetically using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The PCR conditions included a 20 µl reaction mixture containing 30 ng template DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 µM each primer, and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase, utilizing universal Lac16S forward primer (5’AATGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCT3’) and Lac16S reverse primer (5’GAGGTGATCCAGCCGCAGGTT3’). Initial denaturation occurred at 94°C for 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 52°C for 30 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 30 seconds, with a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 minutes [

31]. A 600-700 bp amplicon was sequenced using an automatic gene sequencer (Hitachi-3130xl). The sequence was compared with LAB strains in the NCBI BLAST library, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 4.0 (

http://megasoftware.net/features.html), and the sequence was submitted to GenBank for accession.

2.5. Batch Fermentation and Extraction of Bacteriocin

Batch fermentation of bacteriocin was carried out in sterile MRS broth by inoculating 5% inoculum (5×10^5 cfu/ml) of the promising LAB isolate and incubating microaerobically at 37°C for 24 hours [

32]. Aliquots of samples (2 ml) were removed from the fermentation broth at 3-hour intervals, centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes, the pH was adjusted to 7.0, and 100 μl of catalase enzyme was added to neutralize the effect of H2O2 and evaluated for antibacterial activity against

Xpp. After fermentation, the produced bacteriocin was extracted by ammonium sulfate precipitation and chloroform-methanol extraction method [

33].

2.6. Ammonium Salt Precipitation and Chloroform-Methanol Extraction

The fermented broth was harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and the pH of the cell-free supernatant (CFS) was adjusted to 7.0 to neutralize acids. The CFS was precipitated and harvested by adding 70% ammonium sulfate and centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C, respectively. The pellet was suspended in 50 mM Sodium Phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and labelled as crude bacteriocin preparation (CBP). Further, the CBP was subjected to solvent extraction using an equal volume of a mixture of chloroform-methanol (2:1 v/v) for 1 hour at 4°C. The precipitate developed at the solvent-aqueous interface was collected, air-dried, and dissolved in 5 ml of 50 mM Sodium Phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and labelled as partially purified bacteriocin (PPB)[

33]. The protein concentration and antibacterial activity of CFS, CBP, and PPB were evaluated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer at 280 nm (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the agar well diffusion assay method (AWDA) respectively [

34]. The activity units of the extracted bacteriocin were determined by serial two-fold dilution and tested against

Xpp.

2.7. Purification of Bacteriocin

2.7.1. Cation Exchange Chromatography

Cation exchange chromatography was performed using an SP-Sepharose column (2 × 10 cm) prepared with 15 ml SP-Sepharose in 50 ml distilled water and equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.7). A 2.0 ml PPB sample was applied at a 0.5 ml/min flow rate. The column was washed with 30 ml of the same buffer and eluted with a stepwise gradient of 0.2-2 M NaCl in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, with fractions collected every 2 minutes. Protein concentration was measured at 280 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Elico) [

35], and antimicrobial activity was assessed by the AWDA method. Active fractions were further analyzed using gel filtration chromatography.

2.7.2. Gel Filtration Chromatography

Active fractions from cation exchange chromatography were further purified by gel filtration using Sephadex G-50. Two grams of Sephadex G-50 were soaked in 50 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) for 48 hours at room temperature. The gel was then packed into a 2 × 10 cm column. A 2 ml sample (active fraction) was loaded onto the column, which was eluted with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) at 0.5 ml/min, with fractions collected every 2 minutes [

36]. Active fractions were pooled and subjected to final purification by RP-HPLC.

2.7.3. Reverse Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC)

Final purification was performed using RP-HPLC on an Agilent TC system with a C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) from the Agilent 1100 series. The gradient was created using 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. A 2 ml active fraction from gel filtration chromatography was applied to the column. The column was first washed with 20% acetonitrile for 10 minutes and then eluted with a gradient of 0.1% TFA and 20-80% acetonitrile over 55 minutes [

36]. Fractions were collected every 5 minutes and assessed for protein concentration at 280 nm. Fractions with the highest protein concentrations were selected for antimicrobial activity studies.

2.8. Determination of Molecular Weight by SDS-PAGE

Active fractions from RP-HPLC showing significant antibacterial activity against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae (Xpp) were analyzed for molecular weight using SDS-PAGE, with a molecular weight marker (1.2 kDa to 70 kDa) (Sigma) as the standard.

2.9. Effect of Physical and Chemical Factors on Purified Bacteriocin

2.9.1. Effect of Temperature

The effect of temperature on the purified bacteriocin was assessed by heating 1 ml of the active fraction (from RP-HPLC) at 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, and 80°C. Samples were taken at 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes [

37] and tested for loss of antagonistic activity.

2.9.2. Effect of pH

The effect of pH was studied by adjusting the purified bacteriocin (1 ml) to pH 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. The sample was incubated at room temperature for 2 hours before testing the residual antibacterial activity against Xpp [

38].

2.9.3. Effect of Enzymes

The effects of proteolytic enzymes (trypsin, pepsin, and papain) were evaluated by incubating the bacteriocin with 1 mg/ml of each enzyme at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by residual activity testing against Xpp [

38].

2.10. Antibacterial Susceptibility of Purified Bacteriocin and MIC and MBC Spectra

The purified bacteriocin’s antibacterial activity checked against

Xanthomonas axonopodispv. punicae (Xpp) with AWDA by spreading 100µl of culture (5×10

5 cfu/ml) on Glucose Nutrient agar (NGA) and 100µl of purified bacteriocin added into the wells, plates kept in the refrigerator for 30 min. to diffuse bacteriocin in agar. After diffusion, plates were incubated at 30°C for 24hours. The MIC and MBC spectrum of purified Bacteriocin was carried out as per the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines [

39]. The Broth Microdilution method was used for MIC determination where the Glucose Nutrient Broth (NGB) was mixed with various dilutions of extracted and purified bacteriocin, inoculated with 100µl (5X10

5) Xpp, and incubated at 37°C for 48hrs. For MBC evaluation, the cultures from well showing MIC and above MIC concentrations were streaked on the NGA medium and incubated at 37

0C for 48hrs. [

40].

2.11. In Vivo Antibacterial Activity of Purified bacteriocin against Xpp

The antibacterial activity of RP-HPLC purified bacteriocin against isolated Xpp was determined by Detached Leaf Assay (DLA). In which fully expanded leaves of Pomegranate cv. Ganesh were collected and surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1min., followed by 2% Sodium hypochlorite for 3min. and finally washed with sterile distilled water. The isolated and identified Xpp culture (200μl) was inoculated (OD 600=0.4) on both control and test labelled leaves by gentle rubbing with abrasive and purified bacteriocin (400mg/ml) was sprayed over the leaves. The leaves were kept in plates and lined with sterilized filter paper to maintain humidity and incubated at 30

0C for 72hrs. and development of symptoms were monitored for 96 hrs [

41].

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)

A total of 33 presumed LAB colonies were isolated based on negative catalase activity. LAB were detected in all source samples, with the highest proportions found in curd and indigenous cow milk (isolation percentage (IP) 15.15% each) and a minimal presence in wine (3.30%).

3.2. Isolation of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. Punicae

Isolation of the bacterial blight pathogen is crucial for studying its etiology, spread, and management. Five colonies presumed to be Xanthomonas sp., characterized by their circular, convex, light to deep yellow, mucoid appearance, were isolated. These colonies were further characterized based on morphological and biochemical parameters.

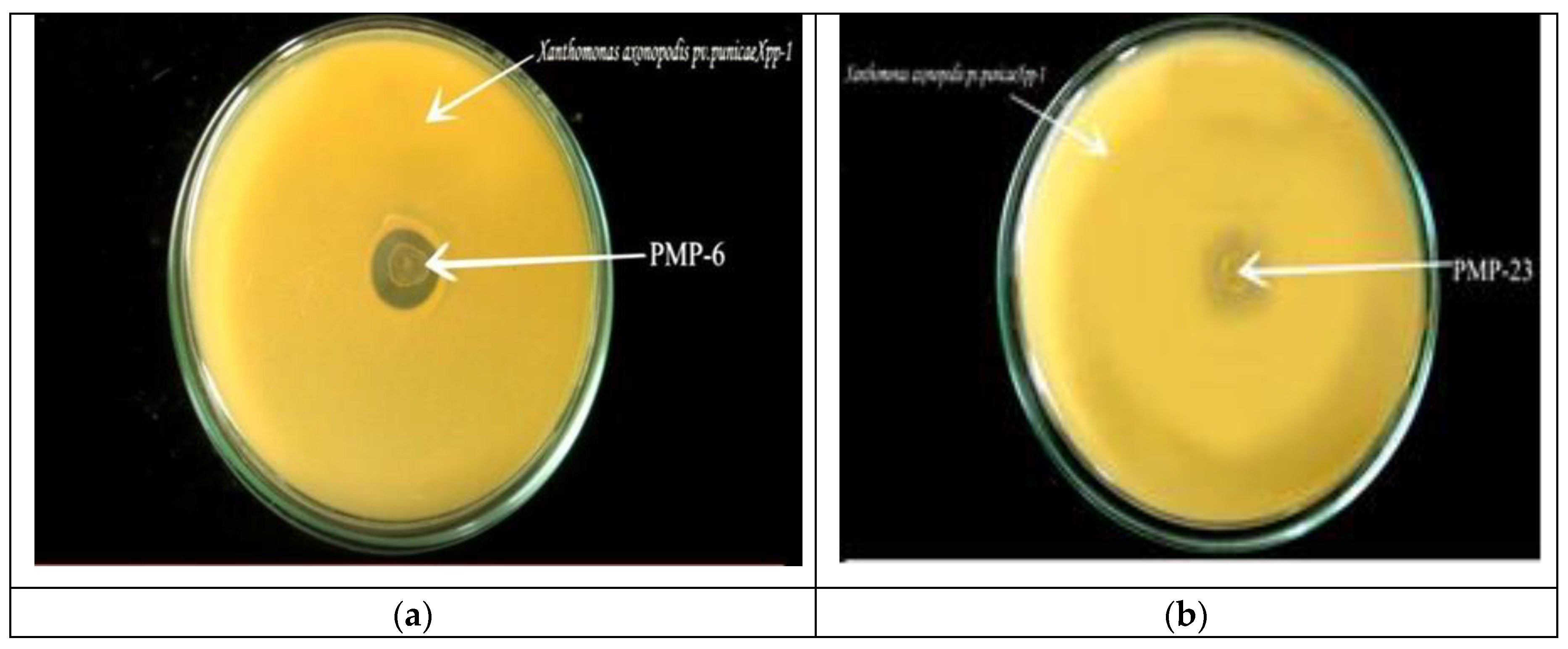

3.3. Screening of Bacteriocin Producing LAB

A total of 33 LAB isolates were screened for antibacterial activity against

Xanthomonas axonopodis pv.

punicae (Xpp-1). The isolates that exhibited a clear growth inhibition zone against Xpp-1 were selected as promising bacteriocin producers (Table 4). The screening revealed that, out of the 33 isolates, only 6 (PMP-6, PMP-13, PMP-18, PMP-23, PMP-27, and PMP-33) demonstrated a considerable zone of inhibition against Xpp-1 (

Figure 1). This indicates that 18.18% of the LAB isolates were bacteriocin producers. Of these 6 isolates, 3 exhibited clear and transparent inhibition zones, while the remaining 3 showed turbid or semi-transparent inhibition zones against the test microorganism.

3.4. Characterization of Promising LAB Isolates

Morphological and biochemical characterization identified the antibacterial activity of six presumed LAB isolates. Microscopic observations revealed that four out of six LAB isolates were rod-shaped, while two were cocci-shaped.

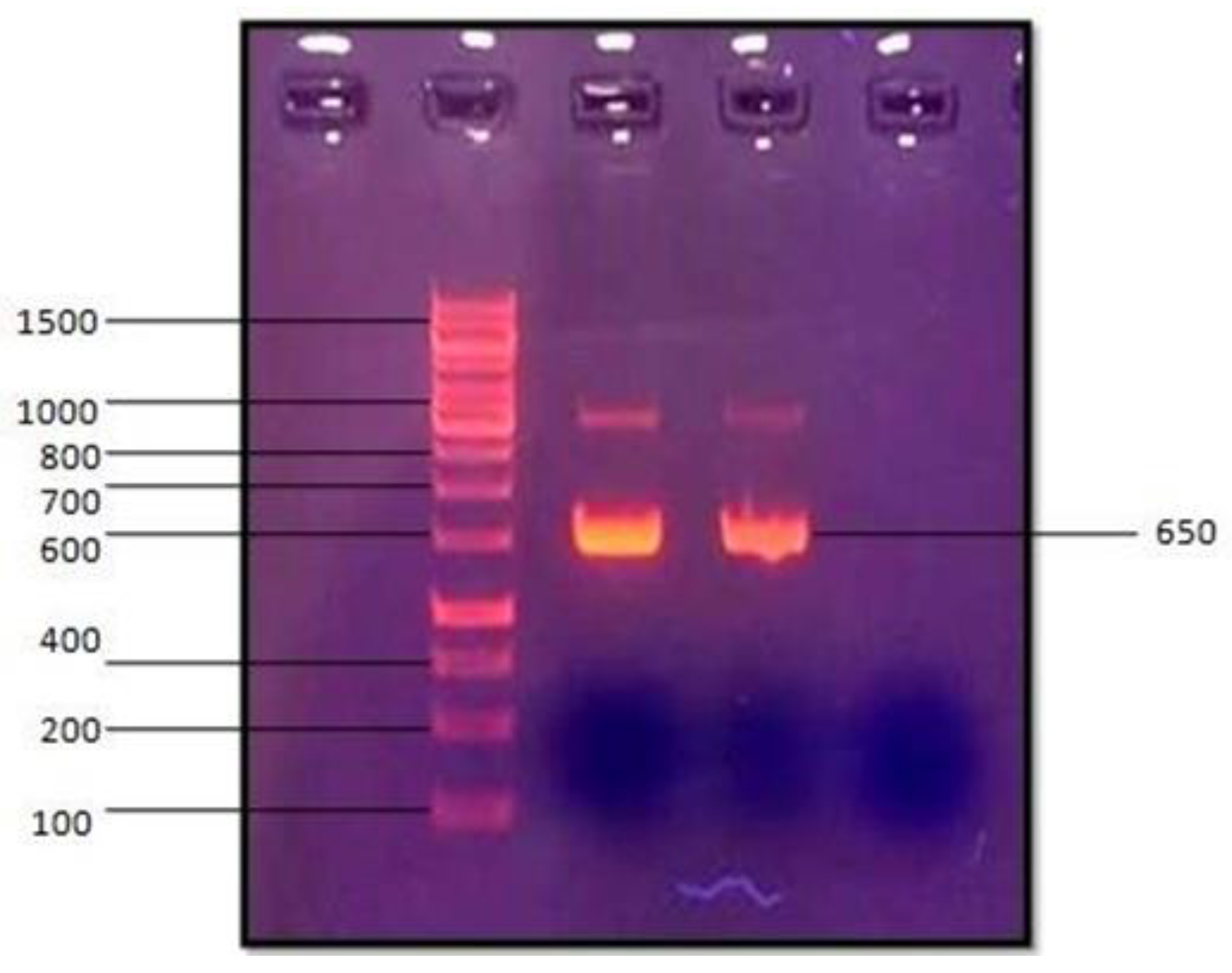

The antibacterial activity of isolates showing clear and transparent zones (PMP-6, PMP-13, and PMP-23) was confirmed separately in MRS broth, incubated micro aerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. Out of the three LAB isolates, only PMP-6 showed an effective and considerable growth inhibition zone against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. Punicae Xpp-1, while PMP-13 and PMP-23 did not show an inhibition zone. Hence, PMP-6 was selected as a promising bacteriocin producer and used for production studies.

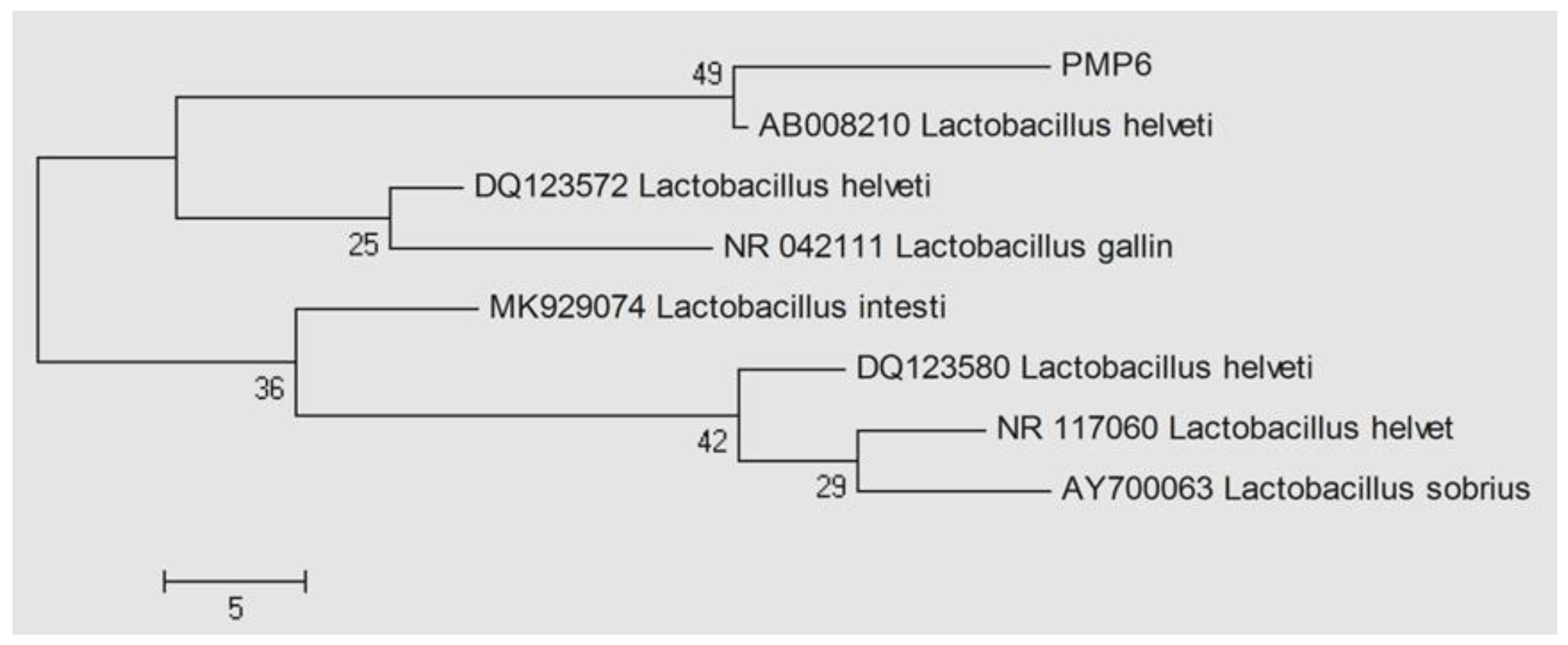

After confirmation of the antimicrobial activity of PMP-6, it was identified by PCR amplification (

Figure 2) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Results revealed that the gene sequence of PMP-6 shows maximum similarity with

Lactobacillus helveticus, which has accession number AB008210 (

Figure 3), so the isolate PMP-6 is designated Lactobacillus helveticus PMP-6. Further, the 16S rRNA gene sequence of PMP-6 was deposited into the National Centre of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with accession number MT444488.

3.5. Batch Fermentation, Extraction, and Purification of Bacteriocin from PMP-6

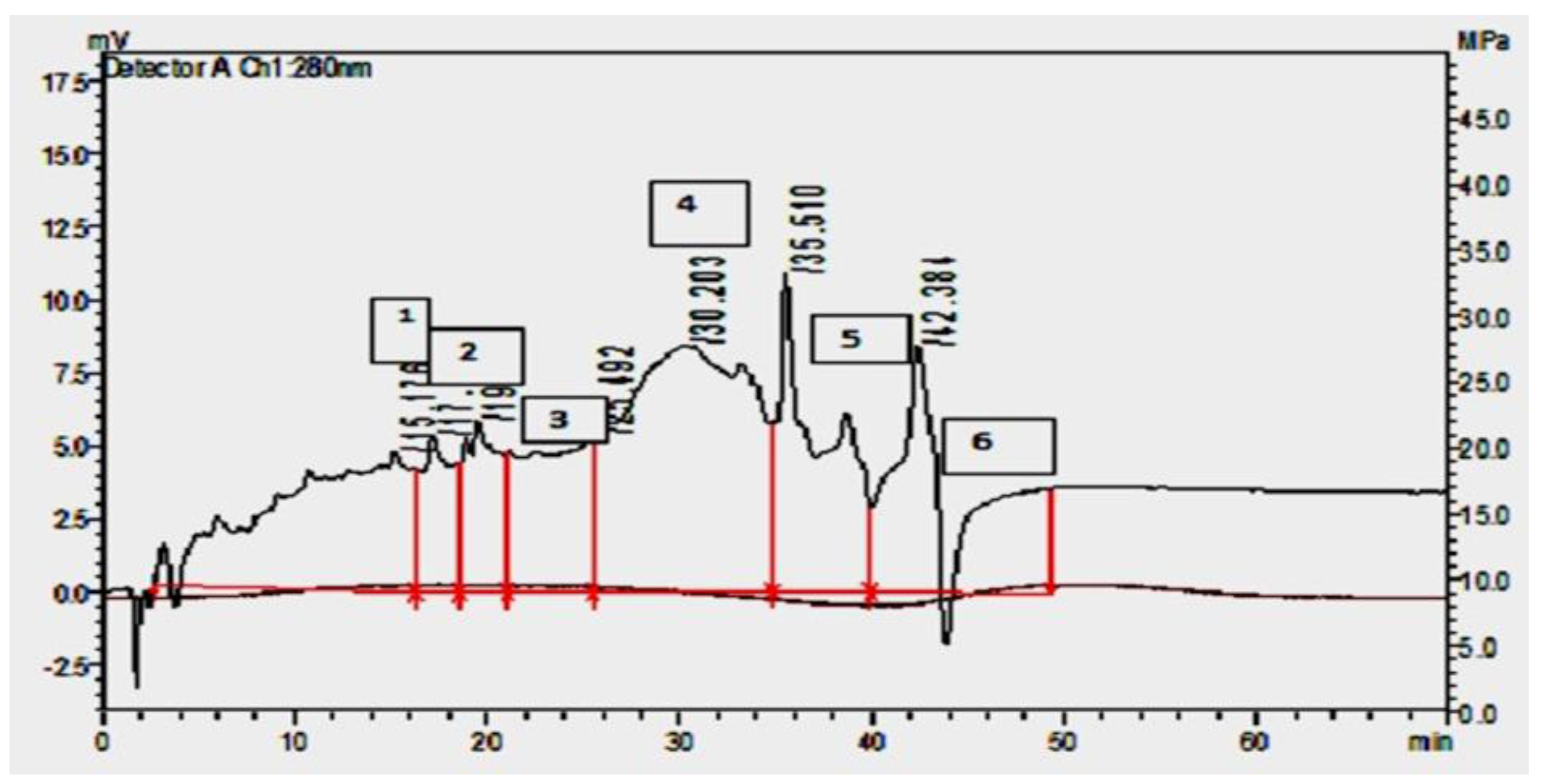

Batch fermentation results revealed that isolate PMP-6 showed maximum protein concentration and zone of growth inhibition against Xpp-1 at the exponential phase. At the same time, antibacterial activity decreased during the stationary and death phases (Data not shown). After evaluation of the antibacterial activity of cell-free supernatant (CFS), it is precipitated by Ammonium sulfate (CBP), pulled for solvent extraction (PPB), and used for antibacterial activity determination. A white precipitate was observed at the interface between Chloroform and culture supernatant fluid during extraction. Interestingly, the antibacterial activity of the interface layer was more significant than the solution collected from the lower and upper layers. However, the antibacterial activity of PPB against Xpp-1 showed an increased zone of growth inhibition compared to the zone observed in CFS. The PPB was purified by cation exchange, gel filtration, and Reverse Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC). Products obtained were evaluated for antibacterial activity. Moreover,

Table 1 represents the protein concentration, total activity, and specific activity of bacteriocin PMP-6 at subsequent purification step, and it inferred that the particular activity of bacteriocin PMP-6 was increased from 233.849AU/mg in CFS to 3615.81AU/mg in RP-HPLC. It is apparent from

Figure 4 that the peak shows graphs of RP-HPLC of bacteriocin PMP-6, in which fractions were collected at 34 to 36 min. The interval showed a maximum protein concentration. It is apparent from

Table 2 and

Figure 5 that bacteriocin PMP-6 showed an increasing zone of growth inhibition,

i.e., from 9 mm to 27 mm against test microorganism during the subsequent purification step.

Calculations:

Activity Units (AU/ml):AU/ml=Reciprocal of the highest dilution×1000/Volume of bacteriocin added

Protein Concentration: Measured by Nanodrop.

Total Protein:Total Protein=Protein Concentration x Total Volume

Total Activity:Total Activity=Activity (AU/ml) ×Total Volume

Specific Activity (AU/mg): Specific Activity = Total Activity of the subsequent purification step /Total Protein of the same step

Fold Purification:Fold Purification=Specific Activity of subsequent step / Specific Activity of crude preparation

Recovery:Recovery= (Total Activity of the subsequent step / Total Activity of crude preparation×100

3.6. Molecular Weight Determination of Purified Bacteriocin

The purified eluted fraction (showing maximum antibacterial activity) from RP–HPLC subjected to molecular weight determination studies (SDS-PAGE).

Figure 6 revealed that the molecular weight of isolated bacteriocin was ≈17kDa, as only one protein band was observed alongside the protein.

3.7. Effect of Physical and Chemical Factors on Bacteriocin PMP-6

3.7.1. Effect of Temperature

It is evident from

Table 3 that a purified bacteriocin PMP-6 showed the maximum residual antibacterial activity percentage (90.476%) against Xpp-1 at 40°C for 15 min. The residual antibacterial activity decreased at temperatures between 50oC and 800oC. However, antibacterial activity was completely lost at 80°C for 30, 45, and 60 min.

3.7.2. Effect of pH

pH stability of purified bacteriocin PMP-6 showed maximum residual antibacterial activity at pH 7 (95.238%), while antibacterial activity was completely lost at pH 10. However, at pH3 to pH6 and pH8-pH9, significantly less residual antibacterial activity was observed than at pH7 (

Table 3).

3.7.3. Effect of Enzymes

A purified fraction of bacteriocin PMP-6 was treated with various enzymes to verify the protein nature of bacteriocin.

Figure 7 and

Table 3 reveal that Trypsin lost antibacterial activity, while activity was retained after treatment with other used enzymes.

3.8. Antimicrobial Activity, MIC, and MBC of Purified PMP-6 Bacteriocin Against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae Xpp-1

Agar well diffusion assay (AWDA) of purified bacteriocin PMP-6 against

Xanthomonas axonopodis pv.punicae Xpp-1 showed growth inhibition of the stated test microorganism with a considerable zone of 24mm (Figure 9). Moreover, the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of bacteriocin PMP-6 against Xpp- 1 was found to be 300mg/ml and 400mg/ml respectively (

Table 4).

3.9. In Vivo Antibacterial Activity of RP-HPLC Purified Bacteriocin Against Xpp-1

In vivo, validation of antagonistic results of RP-HPLC purified PMP-6 bacteriocin against Xpp-1 was determined by Detached Leaf Assay (DLA).

Figure 8 revealed that, following incubation for 96 hrs., symptoms of bacterial blight (water-soaked oily spot) were initiated in the control sample. In contrast, no bacterial blight symptom was observed on leaves treated with PMP-6 purified bacteriocin. Moreover, leaves in the control set turned pale yellowish, while leaves in the test set seemed more greenish, fleshy, and healthy.

4. Discussion

LAB has attracted much more attention over the last few years due to the production of many critical antimicrobial peptides and bacteriocins. Total 33 presumed LAB isolated from various source samples such as Whey (IP 6.06%), Sheep milk (IP 9.09%), Indigenous cow milk (IP 15.15%), curd (IP1 5.15%), cheese (IP 6.06%), paneer (IP 9.09%), spoiled dairy products (IP 12.12%), rose inner petals (IP 6.06%), spoiled vegetables (IP 9.09%), and wine (IP 3.30%). All the used source samples persisted LAB in more or less proportion as isolation percentage (IP) varies from 3.30% to 15.15%, which indicates the wide distribution of LAB in the above-mentioned sources. Numerous reports revealed the isolation of LAB; Trias, et al., (2008) Isolated 56%, 77%, and 100% from Fresh Fruit, raw whole vegetables, and packaged ready-to-eat salad vegetables, respectively. Deshmukh and Thorat, (2014) Isolated and identified Lactobacillus similis RL7 from rose inner petals.

Pomegranate Bacterial blight (BB) pathogen Xanthomonas axonopodispv. punicaeisolated from infected plant source samples and identified on morphological and biochemical parameters. Many researchers reported similar morphological characteristics. Gargade and Kadam (2014) isolated Xanthomonas axonopodiespv. punicaefrom infected fruit showing mucoid, circular, convex, yellow, round, glistening, and raised colonies with Gram-negative rods, motile, positive for catalase, starch hydrolysis, and oxidase reaction. Chowdappa et al. (2018) isolated bacterial blight pathogen showing bright yellow and mucoid colonies from infected leaf and fruit samples. The biochemical character findings of isolated Xpp-1 matches the results of Raghuwanshi et al., (2013).

All the isolated 33 LABs were screened for their antagonistic potential against Xpp-1, and the percentage of bacteriocinogenic LAB was found to be 18.18%. Moreover, 3 LAB isolates showed an opaque (turbid) zone of growth inhibition during screening. The opaque zones observed during screening may be due to the precipitation of nutrient components in the growth medium by LAB’s acidic metabolites less permeability of bacteriocin to target bacterial cell or significantly less concentration of bacteriocin produced. Gajbhiye and Kapadnis, (2017) Detected 62.22% LAB isolates showed vigorous antifungal activity against used fungal pathogens. The bacteriocinogenic LAB was identified by morphological and biochemical parameters. Similar morphological and microscopic observations recorded by Wassie and Wassie, (2016). We did not get even a single report showing the antibacterial activity of LAB against Xanthomonas axonopodispv.punicaeso; we correlated our antagonistic LAB results with the other species of Xanthomonas and fungi. Hence, the difference in the percentage of bacteriocin-producing microorganisms may be due to the difference in test microorganisms and the source sample used for LAB isolation. Moreover, the current research would be the first report on antagonistic activity of LAB (Lactobacillus helveticusPMP-6) against isolated bacterial blight pathogen of Pomegranate.

A broth culture study of three LAB isolates (PMP-6, PMP-13, and PMP-26) showed, out of the three, only PMP-6 showed a considerable zone of growth inhibition against Xpp-1, while PMP-13 and PMP-23 do not show an inhibition zone. Hence, PMP-6 was selected as a promising bacteriocin producer, which was further identified by the 16S rRNA gene sequencing method and designated as

Lactobacillus helveticus PMP-6 (NCBI gene bank accession number MT 444488) based on Sequence homology in NCBI BLAST and phylogenetic tree (

Figure 3) and used for production studies. During screening studies using the agar overlay method, the isolates PMP-13 and PMP-23 showed growth inhibition against Xpp-1, but this activity was lost in the broth culture study. Hence, the antibacterial activity showed by these isolates during screening studies may be due to the production of organic acids or by any other metabolite (Hydrogen Peroxide), or some bacteria produce bacteriocin in less quantity that remains attached to the cell wall of the producer cell.

Batch fermentation results revealed that PMP-6 showed maximum protein concentration and zone of growth inhibition of Xpp-1 at the exponential phase, while antibacterial activity decreased during the stationary and death phases. Moreover, bacteriocin synthesis is a growth-associated phenomenon because production occurs during the mid-exponential phase and increases to reach a maximal level at the end of the exponential phase or the beginning of the early stationary phase, where maximal biomass was observed [

49]. Antagonism by LAB due to metabolic end products such as acids and Hydrogen peroxide can be erroneously attributed to producing bacteriocin-like compounds. Attributing the inhibitory activity of LABs’ bacteriocin requires the elimination of other metabolites produced by LAB isolates. The fermented broth was pulled for salt precipitation and solvent extraction using Chloroform: Methanol as it dispersed some bacteriocin aggregates. According to Burdick (1980), chloroform has a polarity index (PI), and solubility in water is 4.0 and 0.815%, respectively. These properties make chloroform most suitable for bacteriocin concentration. Bacteriocins are amphiphilic peptides with a high affinity towards lipid membranes. The interface between chloroform and aqueous media creates an ideal environment for the concentration of amphiphilic substances such as bacteriocins. Sufficient mixing of culture supernatant fluid with chloroform: methanol allows migration of bacteriocin from the aqueous to the interfacial layer [

51]. Atta et al. (2009) observed an increased growth inhibition zone after ammonium sulfate precipitation and solvent extraction using chloroform. The PPB was further purified by cation exchange, gel filtration, and RP-HPLC and evaluated for Protein concentration, Antibacterial activity, Specific activity, and Recovery. In RP-HPLC (

Figure 4), separations were substantially modified by using Trifluoroacetic Acid (onwards TFA) and acetonitrile [

53]. During RP-HPLC, the specific activity of purified bacteriocin (

Table 1) PMP-6 was increased; moreover, the zone diameter of growth inhibition of test microorganism was threefold increased as compared with CFS (

Table 2 and

Figure 5). These results correlate to observations recorded by Simova et al., (2009).

The molecular weight of bacteriocin PMP-6 (≈17kDa) (

Figure 6) was much higher than numerous researchers reported, possibly due to the unique

Lactobacillus strain used for production. So, following molecular weight, the bacteriocin PMP-6 may be classified in the Class III group. Evaluation of the effect of physical and chemical factors on bacteriocin is imperative for its efficacy and wide spectrum application, specifically for mitigating plant pathogens or plant diseases. The effect of temperature, pH, and enzymes was evaluated against bacteriocin PMP-6. It was revealed that the present bacteriocin is very effective at 40

0C temperature, pH7, and in the absence of proteases, specifically Trypsin (

Table 3) as at temperatures above 40

0C, pH below and above seven the antibacterial activity decreases and it is completely lost, in the presence of protease group of enzymes; which showed that the PMP-6 bacteriocin was sensitive to heat, pH and proteases group of enzymes (trypsin) (

Figure 7). Although this bacteriocin (PMP-6) was sensitive to above mentioned physical and chemical factors it would be very effective in the management of BB of Pomegranate; as the conditions mentioned above are prevalent in Pomegranate crop field and on fruit pericarp. The antibacterial activity of purified bacteriocin PMP-6 showed a zone of growth inhibition to 24mm zone of growth inhibition against Xpp-1 by AWDA; moreover, the concentration for MIC and MBC was found to be 300mg/ml and 400mg/ml, respectively (

Table 4). Hence, the MIC and MBC spectra represent the bacteriocin PMP-6, which possesses good antibacterial and bactericidal activity against tested blight pathogen Xpp-1. Furthermore, the ratio of MBC/MIC is calculated, and it is ≤ 2 for bacteriocin PMP-6, which implies it has bactericidal activity. [

55].

The In Vitro results of PMP-6 bacteriocin were further validated in the “In Vivo” condition by DLA method. The encouraging results were observed as symptoms were not developed in the treated sample for 96hrs. (

Figure 8)

5. Conclusion

LABs are important genera and have been used by humanity since ancient times as probiotics, but it is time to search and illustrate more novel properties for their possible applications in agriculture, veterinary, food packaging, and pharmaceuticals. In the present study, we get encouraging findings (probably the first report) for the possible application of LAB in crop protection concerning BB of Pomegranate. Moreover, the application of LAB helps to reduce the indiscriminate use of agrochemicals, resulting in lesser input cost, qualitative and quantitative Pomegranate production, and conservation of local biodiversity. The efficiency of bacteriocin from Lactobacillus helveticus PMP-6 against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. pumice Xpp- 1 under standard environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, and enzyme shows its capability against the BB sufficiently as it shows the bactericidal effect against the said pathogen. All the above results depict the conflict in the definition of bacteriocin, as bacteriocins are showing antimicrobial activity against closely related strains. Still, results of current research revealed antibacterial activity of isolated bacteriocin against non-closely related (Gram-negative) test microorganisms. Hence, it is of prime importance to reconsider the definition of bacteriocin for a wide-range understanding. However, the antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin was dependent on the receptor site of the test microorganism rather than its relatedness to the producer cell. The range of applications of antimicrobial metabolites of LAB will undoubtedly grow in the future because of their broad-spectrum activity. LAB antimicrobials can be exploited in feed and agriculture applications and in non–food applications such as pharmaceuticals, where they have not yet been effectively exploited commercially at a more excellent pace.

Author Contributions

A short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided for research articles with several authors. The following statements should be used: “Conceptualization, Pravin V. Deshmukh.; methodology, Pravin V. Deshmukh.; software, Pravin V. Deshmukh and Akshay M. Patil.; validation, Pravin V. Deshmukh, and Akshay M. Patil; formal analysis, Sopan Wagh.; investigation, Pravin Deshmukh.; resources, Sopan Wagh and Bhausaheb Pawar.; data curation, Akshay M. Patil.; writing—original draft preparation, Pravin Deshmukh, Akshay M. Patil and Sopan Wagh.; writing—review and editing, Pravin Deshmukh, Akshay Patil and Sopan Wagh.; visualization, Sopan Wagh.; supervision, Sopan Wagh and Bhausaheb Pawar.; project administration Pravin Deshmukh.; funding acquisition, Pravin Deshmukh.

Funding

This research received financial assistance from PunyashlokAhilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur, under the seed money for research scheme with sanction letter SUS/TA-2/2017-18/3902.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the chairperson and trustee of Sahakar Maharshi Shankarrao Mohite – Patil Pratisthan, Shankarnagar, Akluj, for constant support and encouragement throughout the work, would also like to thank Vice Chancellor PunyashlokAhilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur for providing research grant under the seed money for research scheme. Moreover, the authors also like to thank Dr. Sharma (Director, National Research Center for Pomegranate, Solapur), Dr. Manjunath (Scientist, NRCP, Solapur), Dr. Ruchi Agrawal (NRCP, Solapur) and Mr. Jaydeep (NRCP Solapur) for kind help in vivo validation of results by detached leaf assay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Pal, R.K.; Dhinesh Babu, K.; Singh, N. V; Maity, A.; Gaikwad, N. © Copyright ISHRD, Printed in India; 2014; Vol. 46;

- Chandra, R. ; Dhinesh Babu, • K; Vilas, •; Jadhav, T.; Teixeira Da Silva, J.A.

- Mir, M.; Umar, I.; Mir, S.; Rehman, M.; Rather, G.; Banday, S. Quality Evaluation of Pomegranate Crop-a Review. Int J Agric Biol 2012, 14, 658–667. [Google Scholar]

- VAIDEHI BABAN CHOPADE Sc, M.M.; Ed, B. 2015.

- KV, D.; D, R. Pomegranate Processing and Value Addition: Review. J Food Process Technol 2016, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.R.; Sanap, D.J. Economics of Production and Constraints in Pomegranate Cultivation in Vidarbha Region of Maharashtra. ~ 2153 ~ Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry.

- Shaygannia, E.; Bahmani, M.; Zamanzad, B.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. A Review Study on Punica Granatum L. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2016, 21, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansky, E.P.; Newman, R.A. Punica Granatum (Pomegranate) and Its Potential for Prevention and Treatment of Inflammation and Cancer. J Ethnopharmacol 2007, 109, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhange, M.; Hingoliwala, H.A. Smart Farming: Pomegranate Disease Detection Using Image Processing. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier, 2015; Vol. 58; pp. 280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Poovarasan, S.; Mohandas, S.; Paneerselvam, P.; Saritha, B.; Ajay, K.M. Mycorrhizae Colonizing Actinomycetes Promote Plant Growth and Control Bacterial Blight Disease of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L. Cv Bhagwa). Crop Protection 2013, 53, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shali, G.; Krishi, R.; Kendra, V.; Chowdappa, A.; Kamalakannan, A.; Kousalya, S.; Gopalakrishnan, C.; Venkatesan, K.; Shali Raju, G. Isolation and Characterization of Xanthomonas Axonopodis Pv. Punicae from Bacterial Blight of Pomegranate. ~ 3485 ~ Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry.

- ICAR 2015.

- Ashish; Arora, A. An Overview of Bacterial Blight Disease: A Serious Threat to Pomegranate Production. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology 2016, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Hu, B.; Venturi, V.; Liu, F. Proteomic Analysis Reveals Novel Extracellular Virulence-Associated Proteins and Functions Regulated by the Diffusible Signal Factor (DSF) in Xanthomonas Oryzae Pv. Oryzicola. J Proteome Res 2013, 12, 3327–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeilmeier, S.; Caly, D.L.; Malone, J.G. Bacterial Pathogenesis of Plants: Future Challenges from a Microbial Perspective: Challenges in Bacterial Molecular Plant Pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 2016, 17, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Rana, T.S.; Narzary, D.; Verma, N.; Meshram, D.T.; Ranade, S.A. Pomegranate Biology And Biotechnology: A Review. Sci Hortic 2013, 160, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munhuweyi, K.; Lennox, C.L.; Meitz-Hopkins, J.C.; Caleb, O.J.; Opara, U.L. Major Diseases of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.), Their Causes and Management—A Review. Sci Hortic 2016, 211, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terakami, S.; Matsuta, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Sugaya, S.; Gemma, H.; Soejima, J. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of the Dwarf Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L. Var. Nana). Plant Cell Rep 2007, 26, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Gómez, A.; Celador-Lera, L.; Fradejas-Bayón, M.; Rivas, R. Plant Probiotic Bacteria Enhance the Quality of Fruit and Horticultural Crops. AIMS Microbiol 2017, 3, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Félix, J.D.; Silva, L.R.; Rivera, L.P.; Marcos-García, M.; García-Fraile, P.; Martínez-Molina, E.; Mateos, P.F.; Velázquez, E.; Andrade, P.; Rivas, R. Plants Probiotics as a Tool to Produce Highly Functional Fruits: The Case of Phyllobacterium and Vitamin C in Strawberries. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T, B.; KK, B. Common Bacterial Blight (Xanthomonas Axonopodis Pv. Phaseoli) of Beans with Special Focus on Ethiopian Condition. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 2017, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini D B, S.J.P. Invitro Evaluation of Botanicals and Biocontrol Agents against Pomegranate Bacterial Blight Pathogen. Int J Innov Res Sci Eng Technol 2015, 04, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Tsuji, G.; Higashiyama, M.; Ogiyama, H.; Umemura, K.; Mitomi, M.; Kubo, Y.; Kosaka, Y. Biological Control of Bacterial Soft Rot in Chinese Cabbage by Lactobacillus Plantarum Strain BY under Field Conditions. Biological Control 2016, 100, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, M.; Kapadnis, B. Bio-Efficiency of Antifungal Lactic Acid Bacterial Isolates for Pomegranate Fruit Rot Management. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences India Section B - Biological Sciences 2018, 88, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- «d Ennahar, S.; Sashihara, T.; Sonomoto, K.; Ishizaki, A. B: IIa Bacteriocins.

- Chen, Y.; Ludescher, R.D.; Montville, T.J. Electrostatic Interactions, but Not the YGNGV Consensus Motif, Govern the Binding of Pediocin PA-1 and Its Fragments to Phospholipid Vesicles †; 1997; Vol. 63;

- Ross, R.P.; Morgan, S.; Hill, C. P: and Fermentation.

- Reuben, R.C.; Roy, P.C.; Sarkar, S.L.; Alam, R.U.; Jahid, I.K. Isolation, Characterization, and Assessment of Lactic Acid Bacteria toward Their Selection as Poultry Probiotics. BMC Microbiol 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargade, V.A.; Kadam, D.G. Antibacterial activity of some herbal extracts and traditional biocontrol agents against Xanthomonas axonopodis price; 2014; Vol.

- Deshmukh, P.; Thorat, P. Extraction and Purification of Bacteriocin from Lactobacillus Brevis CB-2 and Lactobacillus Zymae WHL-7 for Their Antimicrobial Activity. DAV International Journal of Science 2018.

- Bringel, F.; Castioni, A.; Olukoya, D.K.; Felis, G.E.; Torriani, S.; Dellaglio, F. Lactobacillus Plantarum Subsp. Argentoratensis Subsp. Nov., Isolated from Vegetable Matrices. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005, 55, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalán, Z.; Németh, E.; Baráth, Á.; Halász, A. Influence of Growth Medium on Hydrogen Peroxide and Bacteriocin Production of Lactobacillus Strains**.

- Burianek, L.L.; Yousef, A.E.

- Schllllnger, U.; Kaya, M.; Lucke, F.-K.; Schillinger, U. Behaviour of Listerla Monocytogenes in Meat and Its Control by a Bacteriocin-Producing Strain o f Lactobacillus Sake; 1991; Vol. 70;

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Bu, Y.; Yi, H.; Zhang, L.; Han, X.; Ai, L. Purification and Partial Characterization of Bacteriocin Lac-B23, a Novel Bacteriocin Production by Lactobacillus PlantarumJ23, Isolated from Chinese Traditional Fermented Milk. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, K.; Fatiha, D.; Halima, Z.K.; Nour Eddine, K. Characterization and Purification of Bacteriocin Produced by Enterococcus Sp. GHB26 Isolated from Algerian Paste of Dates Ghars. Afr J Microbiol Res 2016, 10, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Zohra, R.R.; Tarar, O.M.; Qader, S.A.U.; Aman, A. Screening, Purification and Characterization of Thermostable, Protease Resistant Bacteriocin Active against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA). BMC Microbiol 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Castro, P.Y.; Méndez-Romero, J.I.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Acedo-Félix, E.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B. Antimicrobial Activity and Partial Characterization of Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substances Produced by Lactobacillus Spp. Isolated from Artisanal Mexican Cheese. J Dairy Sci 2015, 98, 8285–8293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Hoque, M.A.; Sarker, A.K.; Satter, M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.N.I. Characterization and Profiling of Bacteriocin-like Substances Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria from Cheese Samples. Access Microbiol 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, S.D.; Sadiq, A.L.O.; Safitri, W.A.; Dewi, S.S.; Prastiyanto, M.E. The Antibacterial Activities of Bacteriocin Pediococcus Acidilactici of Breast Milk Isolate to against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; Institute of Physics Publishing, November 22 2019; Vol. 1374. [Google Scholar]

- Ippokoppa 2017.

- Trias, Baneras, R. ; Montesinos, E.; Badosa, E. Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fresh Fruit and Vegetables as Biocontrol Agents of Phytopathogenic Bacteria and Fungi. International Microbiology 2008, 11, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, P.V.; Thorat, P. R. Detection of Antimicrobial Efficacy of Novel Bacteriocin Produced from Lactobacillus Similis RL7. Int J Adv Res (Indore) 2014, 2, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargade, V.; Kadam, D. Antibacterial Activity of Some Herbal Extracts and Traditional Biocontrol Agents against Xanthomonas Axonopodis Punicae. Journal of International Academic Research for Multidisciplinary 2014, 2, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdappa, A.; Kamalakannan, A.; Kousalya, S.; Gopalakrishnan, C.; Venkatesan, K.; Raju, G.S. Isolation and Characterization of Xanthomonas Axonopodis Pv. Punicae from Bacterial Blight of Pomegranate. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2018, 7, 3485–3489. [Google Scholar]

- Raghuwanshi, K.S.; Hujare, B.A.; Chimote, V.P.; Borkar, S.G. Characterization of Xanthomonas Axonopodis Pv. Punicae Isolates from Western Maharashtra and Their Sensitivity To Chemical Treatments. The Bioscan 2013, 8, 845–850. [Google Scholar]

- Gajbhiye, M.; Kapadnis, B. Bio-Efficiency of Antifungal Lactic Acid Bacterial Isolates for Pomegranate Fruit Rot Management. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences India Section B - Biological Sciences, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassie, M.; Wassie, T. Isolation and Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Raw Cow Milk. International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences 2016, 3, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cheigh, C.I.; Choi, H.J.; Park, H.; Kim, S.B.; Kook, M.C.; Kim, T.S.; Hwang, J.K.; Pyun, Y.R. Influence of Growth Conditions on the Production of a Nisin-like Bacteriocin by Lactococcus Lactis Subsp. Lactis A164 Isolated from Kimchi. J Biotechnol 2002, 95, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdick, J. High Purity Solvent Guide; Ed. Przyby.; Burdik and Jackson Laboratories Inc., Muskegon, Michigan, USA. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Burianek, L.L.; Yousef, A.E. Solvent Extraction of Bacteriocins from Liquid Cultures. Lett Appl Microbiol 2000, 31, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta, H.; Refaat, B.; El-Waseif, A. Application of Biotechnology for Production, Purification and Characterization of Peptide Sntibiotic Produced by Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum, NRRL B-227. Global Journal of Biotechnology and Biochemistry 2009, 4, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Mant, C.T.; Hodges, R.S. Effects of Ion-Pairing Reagents on the Prediction of Peptide Retention in Reversed-Phase High-Resolution Liquid Chromatography. J Chromatogr 1987, 386, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simova, E.D.; Beshkova, D.B.; Dimitrov, Z.P. Characterization and Antimicrobial Spectrum of Bacteriocins Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Bulgarian Dairy Products. J Appl Microbiol 2009, 106, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasu, E.N.; Ahor, H.S.; Borquaye, L.S. Peptide Extract from Olivancillaria Hiatula Exhibits Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Activity. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Screening of bacteriocin-producing Lactic acid bacteria by the Agar overlay method. Plated on MRS agar and overlayed with Xpp-1, the clear zone (PMP-6) and turbid zone (PMP -23) of growth inhibition of Xpp-1 were observed following incubation at 37°C for 24 hrs.

Figure 1.

Screening of bacteriocin-producing Lactic acid bacteria by the Agar overlay method. Plated on MRS agar and overlayed with Xpp-1, the clear zone (PMP-6) and turbid zone (PMP -23) of growth inhibition of Xpp-1 were observed following incubation at 37°C for 24 hrs.

Figure 2.

16S rRNA gene amplification of PMP-6 LAB isolate by Polymerase Chain Reaction (From The hand, the second well was loaded with marker, and the third and fourth wells were loaded with 16S rRNA gene).

Figure 2.

16S rRNA gene amplification of PMP-6 LAB isolate by Polymerase Chain Reaction (From The hand, the second well was loaded with marker, and the third and fourth wells were loaded with 16S rRNA gene).

Figure 3.

The phylogenetic tree of PMP-6 LAB isolates according to 16S rRNA gene sequence, BLAST, and MEGA 4.0 showed similarity with Lactobacillus helveticus (AB008210); numbers at the nodes indicate bootstrap values on neighbor-joining analysis.

Figure 3.

The phylogenetic tree of PMP-6 LAB isolates according to 16S rRNA gene sequence, BLAST, and MEGA 4.0 showed similarity with Lactobacillus helveticus (AB008210); numbers at the nodes indicate bootstrap values on neighbor-joining analysis.

Figure 4.

RP - HPLC purification of ppb from pmp-6 inferred fractions collected at 34 to 36 mins. Shows the highest protein concentration at 280 nm detector.

Figure 4.

RP - HPLC purification of ppb from pmp-6 inferred fractions collected at 34 to 36 mins. Shows the highest protein concentration at 280 nm detector.

Figure 5.

Antibacterial activity of bacteriocin from LAB isolate PMP-6 against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae Xpp-1 at various purification stages by AWDA method showed that the zone diameter of growth inhibition increased as purification progressed. The clear zones indicate inhibition of bacterial growth by cell-free supernatant, ammonium sulfate precipitation, dialysis, fractions from cation exchange chromatography, gel filtration chromatography, and RP-HPLC, compared to the sterile distilled water control.

Figure 5.

Antibacterial activity of bacteriocin from LAB isolate PMP-6 against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae Xpp-1 at various purification stages by AWDA method showed that the zone diameter of growth inhibition increased as purification progressed. The clear zones indicate inhibition of bacterial growth by cell-free supernatant, ammonium sulfate precipitation, dialysis, fractions from cation exchange chromatography, gel filtration chromatography, and RP-HPLC, compared to the sterile distilled water control.

Figure 6.

Molecular weight analysis of RP-HPLC purified bacteriocin from PMP-6 by SDS-PAGE. RP-HPLC purified PMP-6 bacteriocin loaded on SDS-PAGE gel for molecular weight analysis and observed a single band having molecular weight to ≈ 17KD alongside of marker (From left: Well A-D, F, and G are empty, well E: sample (RP-HPLC fraction) and last well contain molecular weight marker).

Figure 6.

Molecular weight analysis of RP-HPLC purified bacteriocin from PMP-6 by SDS-PAGE. RP-HPLC purified PMP-6 bacteriocin loaded on SDS-PAGE gel for molecular weight analysis and observed a single band having molecular weight to ≈ 17KD alongside of marker (From left: Well A-D, F, and G are empty, well E: sample (RP-HPLC fraction) and last well contain molecular weight marker).

Figure 7.

The effect of different enzymes on the antibacterial activity of purified PMP-6 bacteriocin by the agar-well diffusion method showed that antibacterial activity was lost when treated with Trypsin.

Figure 7.

The effect of different enzymes on the antibacterial activity of purified PMP-6 bacteriocin by the agar-well diffusion method showed that antibacterial activity was lost when treated with Trypsin.

Figure 8.

Antibacterial activity of PMP-6 against Xpp-1 by DLA showed no symptoms of BB observed on leaves for 96 hrs. (a) – Control (Without treatment), (b) – Control (Sterile Distilled Water), (c) – Test (Treated with RP-HPLC purified PMP-6 bacteriocin), (d) – Symptoms of BB on leaves in control set inoculated with Xpp-1.

Figure 8.

Antibacterial activity of PMP-6 against Xpp-1 by DLA showed no symptoms of BB observed on leaves for 96 hrs. (a) – Control (Without treatment), (b) – Control (Sterile Distilled Water), (c) – Test (Treated with RP-HPLC purified PMP-6 bacteriocin), (d) – Symptoms of BB on leaves in control set inoculated with Xpp-1.

Table 1.

Purification steps for bacteriocin produced by PMP-6 include protein concentration, total activity, and specific activity.

Table 1.

Purification steps for bacteriocin produced by PMP-6 include protein concentration, total activity, and specific activity.

| Purification step |

Volume (ml) |

Protein (mg/ml) |

Total Protein

(mg) |

Activity units

(AU/ml) |

Total Activity

(AU) |

Specific Activity

(AU/mg) |

Purification fold |

Recovery (%) |

| CFS |

500 |

3.421±0.014 |

1710.5 |

800±1 |

400000 |

233.849±0.5 |

1 |

100 |

| CBP |

100 |

2.754±0.005 |

275.4 |

3200±1.52 |

320000 |

1161.94±0.5 |

4.96 |

80 |

| PPB |

50 |

1.891±0.0015 |

94.55 |

6400±1.52 |

320000 |

3384.45±0.02 |

14.47 |

80 |

| RP-HPLC |

10 |

1.77±0.005 |

17.7 |

6400±1 |

64000 |

3615.81±0.01 |

15.46 |

16 |

Table 2.

Zone diameter of growth inhibition of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. pumice Xpp-1 by bacteriocin from PMP-6 at subsequent purification steps.

Table 2.

Zone diameter of growth inhibition of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. pumice Xpp-1 by bacteriocin from PMP-6 at subsequent purification steps.

Sr.

No. |

Isolates |

Zone diameter (mm) of growth inhibition against Xanthomonas

axonopodispv. PunicaeXpp-1 |

| Cell-free supernatant |

(70%) Ammonium

salt, and solvent extraction |

Chromatographic methods |

Cation

exchange |

Gel

filtration |

RP–

HPLC |

| 1 |

PMP-6 |

9±0.5 |

12±1 |

15±0.5 |

23±0.57 |

27±1 |

Table 3.

Effect of Temperature, pH, and Enzyme on antibacterial activity of PMP-6. bacteriocin.

Table 3.

Effect of Temperature, pH, and Enzyme on antibacterial activity of PMP-6. bacteriocin.

Sr.

No. |

Effect of Parameter |

Zone diameter (mm) of growth inhibition of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae Xpp-1

|

% of Residual Activity against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae Xpp-1

|

| |

|

(0C) |

Exposure Timeinmin. |

|

|

1. |

Control |

370C |

15 |

21±0.5 |

100 |

| 30 |

22±0.5 |

100 |

| 45 |

21±0.5 |

100 |

| 60 |

23±1.0 |

100 |

Temperature |

40 |

15 |

19±0.5 |

90.476 |

| 30 |

18±0.5 |

81.818 |

| 45 |

15±1.0 |

71.428 |

| 60 |

14±0.5 |

60.869 |

50 |

15 |

16±1.52 |

76.190 |

| 30 |

15±0.57 |

68.181 |

| 45 |

12±1.15 |

57.142 |

| 60 |

10±0.57 |

43.478 |

60 |

15 |

13±0.57 |

61.904 |

| 30 |

12±0.57 |

54.545 |

| 45 |

10±0.57 |

47.619 |

| 60 |

08±0.57 |

34.782 |

70 |

15 |

10±0.57 |

47.619 |

| 30 |

09±0.57 |

40.909 |

| 45 |

07±1.0 |

33.333 |

| 60 |

06±0.57 |

26.086 |

80 |

15 |

08±1.15 |

38.095 |

| 30 |

00 |

0.00 |

| 45 |

00 |

0.00 |

| 60 |

00 |

0.00 |

2. |

Control |

6.5 |

24±1.0 |

100 |

pH |

3.0 |

05±0.57 |

20.833 |

| 4.0 |

08±1.15 |

33.333 |

| 5.0 |

11±1.0 |

45.833 |

| 6.0 |

18±1.52 |

75.00 |

| 7.0 |

20±1.73 |

95.238 |

| 8.0 |

14±1.52 |

58.333 |

| 9.0 |

04±0.57 |

16.666 |

| 10 |

00 |

0.00 |

3. |

Control |

Untreated |

24±1.52 |

100 |

Enzymes |

Trypsin |

00 |

0.00 |

| Pepsin |

00 |

0.00 |

| Amylase |

19±1.0 |

79.166 |

| Lipase |

18±1.15 |

75.00 |

| Alkaliphosphatase |

15±0.57 |

65.500 |

| Catalase |

17±1.73 |

70.833 |

Table 4.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Spectra of Bacteriocin PMP-6 against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae (Xpp-1).

Table 4.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Spectra of Bacteriocin PMP-6 against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae (Xpp-1).

Concentration of Bacteriocin PMP-

6 (mg/ml) |

Growth of Xpp-1at 600 nm |

Number of colonies |

MIC

(mg/ml) |

MBC

(mg/ml) |

| 500 |

- |

00 |

300 |

400 |

| 450 |

- |

00 |

| 400 |

- |

00 |

| 350 |

- |

3±0.57 |

| 300 |

- |

5±1.52 |

| 250 |

+ |

Not determined |

| 200 |

+ |

Not determined |

| 150 |

+ |

Not determined |

| 100 |

+ |

Not determined |

| 50 |

+ |

Not determined |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).