1. Introduction

Atomistic simulations of binding between anti-HIV agents and various biological systems containing complex biomacromolecules supplies a theoretical basis for the investigation of the microscopic level processes during the antiretroviral therapy. X-Ray crystallographic data about ligand–receptor complexes between proteins or nucleic acids receptors and drug molecules often become a starting model for these simulations. Alternatively, the starting models can be obtained from molecular docking of small molecules of drugs and the receptor molecules which requires a high-resolution 3D structure of the receptor. We believe that descriptors based only on analysis of structural data from experimental or computational studies cannot supply a detail description of ligand-receptor binding. The methods that use electron density distribution function or wavefunction are much more informative for the aforementioned purpose. Indeed, a number of studies of such ligand–receptor complexes in terms of methods employing electron density distribution function [

1,

2], NCI [

3,

4] and source function [

5,

6] were published recently. As a result, the detailed picture of ligand-receptor binding was recovered including nature and energy of all possible ligand – receptor interatomic interactions.

In the present article we discuss the intermolecular interactions of 1-[2-(2-benzoylphenoxy)ethyl]-6-methyluracil (

VMU-2012-05,

Scheme 1) that was patented in Russia as new prospective nonnucleoside inhibitor of reverse transcriptase in its single crystal and complexes with protein and nucleobases to evaluate the conformational stability of

VMU-2012-05 and its ability to bind with biomolecules (Patent RU2648998C1 [

7]). According to published preliminary studies,

VMU-2012-05 is characterized by rather low toxicity on rats [

8] and demonstrated high activity for wild and mutant HIV-1 that 2.5 times exceeds that for nevirapine [

7]. Thus, our study will be essential for a comprehensive understanding of the effect of

VMU-2012-05 on molecular scale. The electron density distribution, the type and energies of intermolecular interaction for crystalline

VMU-2012-05 could be obtained experimentally as a reference. The quantum crystallography methods were applied to molecular models of varying complexity from dimers of

VMU-2012-05 with nucleosides to a ligand-receptor complex as the reliable computational scheme to assess the role of the intermolecular interactions using the theoretical electron density distribution function. The study of the ligand-protein receptor binding can be carried out with QM/MM calculations, but the level of information value is in direct relation with the size of QM subsystem. The description of ligand to DNA/RNA binding is more complex task due to lack of accurate crystallographic data. In our previous study the model with ~ 500 atoms was used for the study of binding of ferrocene derivative to the fragment of DNA [

9] but the size of the model QM system required for correct description of DNA/RNA binding is unclear yet.

In order to evaluate effects of intermolecular interactions on molecular conformation of a flexible molecule in terms of energy, we performed conformational analysis of an isolated molecule of VMU-2015-05, compared stable conformations of an isolated molecule with that experimentally observed in crystal, and those in a model drug–nucleoside or a drug–aminoacid dimers as well as the ligand–protein complex. Herein we demonstrated that the main features of the stacking interactions and the H-bonding between the molecule of anti-HIV drugs and DNA/RNA can be sufficiently described using rather small models of stacking dimers. Vice versa, dimers of the drug and an aminoacid do not represent the ligand-protein binding; exhaustive study of binding situation with the methods based on electron density function requires all aminoacids surrounding the molecule of drug to be a part of the QM subsystem. The applied methodology paves the way to estimate the ability of a drug molecule to bind with biomolecules provided that the 3D structure of the receptor is unknown.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Collection, Reduction and Refinement

Single-crystals were grown by slow evaporation from a water-ethanol mixture at room temperature. A good quality single-crystal was selected from the precipitate and mounted on a MiTeGen® MiroMount® plastic loop. X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100(2) K on the Agilent Super Nova diffractometer equipped with the Oxford Cryostream cooling device and the Supernova microfocus X-ray source with the molybdenum anode (λ = 0.71073 Å). Omega and phi scans were carried out at several detector positions utilizing various exposure times to reach completeness and maintain sufficient redundancy at high diffraction angles. The measured intensities were integrated and corrected for absorption with the Rigaku OD CrysAlis Pro software [

10].

2.2. Independent Atom Refinement

Crystal structure was solved using the SHELXT [

11] software and refined against F

2hkl in anisotropic approximation for non-hydrogen atoms with SHELXL [

12] and OLEX2 [

13] programs. Riding hydrogens were used to calculate and refine hydrogen atomic positions. The obtained structure is shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Multipole Refinement

The charge distribution in

VMU-2012-05 was obtained using multipole formalism [

14] as implemented in the MoPro package [

15] with core and valence electron density derived from wave functions fitted to a relativistic Dirac-Fock solution. In the first step, the scale factor was refined from all data. After that, the high-order refinement (sin(θ) / λ > 0.7 Å) of atomic positions and atomic displacement parameters incorporating all non-hydrogen atoms was employed, followed by refinement of hydrogen atoms positions, with C–H, N–H, and O–H distances fixed at values obtained from neutron diffraction [

16]. The ADPs for hydrogen atoms were estimated using SHADE3 software [

17]. All non-hydrogen atoms were described at the octupolar level. For the H atoms, only the monopole population and the dipole populations were refined, while κ and κ’ were fixed to H atom theoretical values [

18]. Separate κ parameters were used for all non-hydrogen atoms. During the final stage of the refinement, the multipole parameters, positions, and thermal parameters of all non-hydrogen atoms and monopoles were refined. All bonded pairs of atoms satisfied the Hirshfeld criterion. The experimental and refinement parameters are listed in

Table S1 (Electronic Supporting Information, ESI). Maps of electron deformation density, of residual electron density, analysis of the residual density according to Meindl & Henn [

19,

20] and the DRK-plot obtained via the WinGX suite [

21] are also given and discussed in the Supporting Information.

2.4. Computational studies

Quantum chemical calculations were carried out by ORCA quantum chemistry program package [

22]. Initial geometry for quantum chemical calculations was taken from the X-ray study and then used to perform subsequent conformational analysis. Mercury program [

23] was applied to generate the initial structures for conformational search using molecular mechanics. The structures with the lowest energy were then optimized with B3LYP/def2-TZVPP method/basis combination. The results of conformational studies were used to construct the stacked dimers and to research the stacking interactions with nucleobases. To construct the initial models for the staked dimers the amino groups of the nucleobases were positioned opposite to the plane of monosubstitued phenyl cycle of

VMU-2012-05 at the distance of ~ 4 Å. Energies of the interactions between the nucleobase and

VMU-2012-05 were calculated as the difference between the total energy of the stacked dimer and its components. To account the dispersion interactions and to obtain more exact geometry on the hybrid DFT level the D3BJ correction [

24] was applied. Second derivatives matrices were calculated for all optimized structures to check the absence of positive eigenvalues. Harmonic frequencies and thermodynamic properties were calculated to define the values of zero-point energies and to correct previously calculated interaction energies in stacked dimers. To compare the values of the interaction energies in the stacked dimers obtained on hybrid DFT level, the additional DLPNO-CCDC(T)/6-311G(d,p) calculations were carried out.

2.5. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was carried out with the Cambridge Structural Database Gold software [

25] using the genetic algorithm and the 1S1V structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [

26] as a starting point. Prior to the docking procedure, the molecules of external water were removed from the 1S1V structure. After that the hydrogen atoms were added to the protein residues. To score the solutions, the GOLD score function was applied, and the results were then additionally rescored with the Chemscore function.

2.6. QM/MM Calculations

To reveal the strength and the nature of the interactions between

VMU-2012-05 and a protein molecule, a simplified model was calculated. The structure of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complex with the

VMU-2012-05 described above was used as the starting point. The coordinates of 906 atoms from the

VMU-2012-05 molecule, the surrounding peptide chains, and the water molecules were marked as an active region in the corresponding pdb file. After that, the QM region of 224 atoms was selected from the active region containing

VMU-2012-05 and its closest environment involved in intermolecular interactions. The number of the amino acid residues (18) exceeds typical molecular coordination number and should be sufficient to describe all interactions between

VMU-2012-05 and receptor molecules in the selected binding site. The next step was related to the structure optimization. The following combination was applied to optimize the geometry of the models: B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) with D3BJ correction for QM part and CHARMM force field for the rest of the amino acids′ residues. The water molecules in the MM part were described using the TIP3P model [

27]. The CHARMM parameters were used for

VMU-2012-05 moieties [

28,

29]. After the optimization, the size of the QM region was expanded up to 448 atoms to include the residues that more distant from the

VMU-2012-05 molecule to mimic the distribution of the electron density in the region of the ligand-receptor interactions. The geometry optimization, the hessian and the charge density calculations of the drug–receptor complex were carried out using the ORCA quantum chemistry program package [

22]. The charge density functions for the drug–receptor complex were analyzed in terms of QTAIM theory [

30], and the NCI method [

31] using Multiwfn software [

32].

3. Results and Discussion

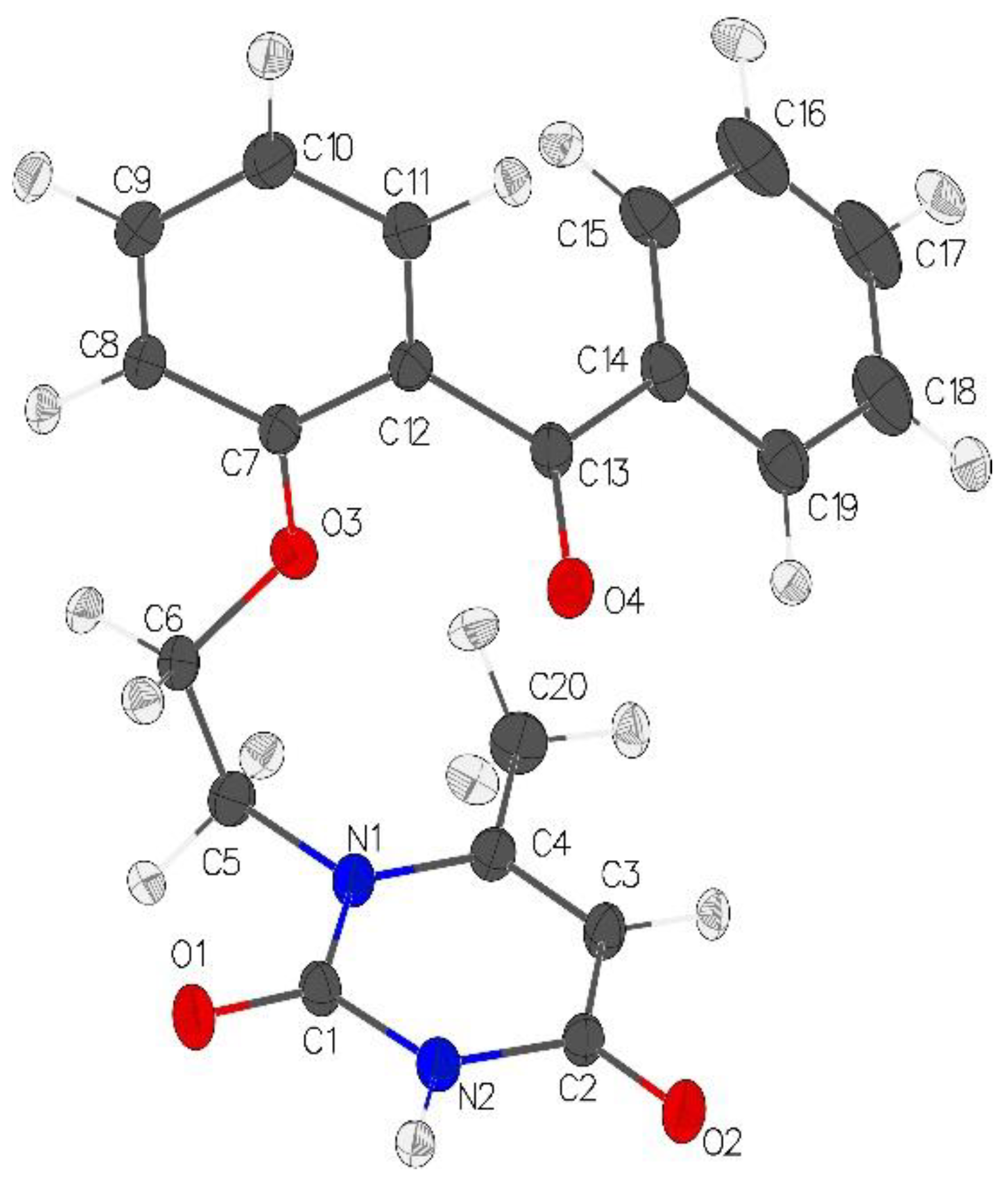

3.1. X-ray Study and Experimental Electron Density Analysis

Single crystals contain one molecule of

VMU-2012-05 in the asymmetric unit in the folded conformation (

Figure 1). The molecule remains neutral upon the crystallization with the hydrogen atom solely localized on the nitrogen atom of the heterocycle. This hydrogen atom takes part in the N2-H2...O2 bonding (N...O and H...O distances are 2.847(3) and 1.84 Å, respectively, ∟NOH = 170.3º) to assemble the

VMU-2012-05 molecules into the centrosymmetric H-bonded dimers. In addition, there are several weak C-H...O bonds. Analysis of the crystal packing also reveals the stacking interaction between the phenyl group and the uracil moiety of neighboring molecules with slightly inclined disposition of rings (the value of interplanar angle is 5.81(7)°, the distance between centroids of corresponding cycles is equal to 3.398(3) Å).

A characteristic feature of this molecule is that it has five acceptor groups per the only donor group. Note that most of the nucleoside inhibitors of HIV contain several groups that can form strong hydrogen bonds, especially NH, OH, C=O. Therefore, among all non-covalent interactions the strong hydrogen bonds play a key role for the stabilization of the crystal packing and the realization of the ligand-receptor complexes [

33,

34]. Instead, non-nucleoside HIV inhibitors usually do not possess potential donor groups suitable for appearance of the strong hydrogen bonds in the crystals. As a result, their crystalline packing is stabilized mainly by weak C–H...O bonds and van-der-Waals H...H interactions, while the contribution of strong hydrogen bonds to the lattice energy here is small. Recently, we demonstrated that the contribution of the hydrophobic interactions to the binding energy in the complex between a protein and lamivudine is comparable to that for the lattice energy of the tetragonal polymorph II of free base lamivudine despite the discrepancies in the molecular conformation, while the energies of the hydrophilic interactions decrease [

35]. For antitumor agent bicalutamide, both contributions and the total interaction energies were found to be nearly the same both for the experimental charge density studies and the QM/MM calculations [

36].

We performed the detailed study of the intermolecular interactions in the crystal of

VMU-2012-05 within the formalism of the Quantum Theory “Atoms in Molecules” (QTAIM) formulated by R. Bader, as well as using the Non-Covalent Interactions (NCI) method, using the results of the multipole refinement based on the high-resolution X-ray diffraction data. To evaluate the energy of the weak interactions we used the Espinosa-Mollins-Lecomte correlation formula that allows one to calculate required values using the potential energy density V(

r) in bond critical points (

bcps) as E

int = 0.5V(

r) [

37]. In addition, another formula E

int = 0.429G(

r) has been used for the evaluation of the hydrogen bonds and the weak interaction energies via kinetic energy density G(

r) [

38]. The corresponding values are given in the ESI.

The analysis of the experimental charge density function in the crystal of

VMU-2012-05 reveals

bcps related to all covalent bonds and the weak intra-/intermolecular interactions. All covalent bonds are characterized by the negative values of Laplacian and local energy density that corresponds to the shared type of interactions (detailed information can be found in ESI,

Table S1 and Figs. S1 – S5). At the same time, weak intra- and intermolecular interactions correspond to the closed-shell type of interactions with the positive values of Laplacian and local energy density in respective

bcps. QTAIM study reveals three intramolecular interactions, namely, the C–H...O bond between the methyl group bonded to the uracil fragment and bridging oxygen atom (C20–H202...O3), as well as two unusual contacts, O4...C4 and C19...C20. The first contact can be described as a peak-hole interaction, while the second one most probably belongs to weak dispersion interactions. These findings are in good agreement with the evaluated energies of the interaction (-3.7 and -1.5 kJ/mol). The hydrogen bond N2–H2...O2 was found to be the strongest intermolecular interaction, (-29.5 kJ/mol) while the energies of C–H...O and C–H...N bonds are much weaker (-2.3 – -7.6 kJ/mol and -2.2 – -3.7 kJ/mol). At the same time, only one

bcp (C16...N1) can be associated with the stacking interaction, so its strength was estimated as -2.7 kJ/mol. The sum of all intermolecular interactions, i.e. lattice energy (E

latt), was found to be -214.6 kJ/mol. The sum of the partial contributions of hydrophilic C–H...O and C–H...N weak interactions gives more than 50% (53.1 and 5.5%) of E

latt. Thus, the energy and the characteristics of the intermolecular interactions found in the crystal under study are typical for organic compounds. Comparison of the molecular conformations in crystal and isolated molecules, and analysis of the energies of rotational barriers and intermolecular interactions could allow revealing which of interactions mainly affect the conformation in a condensed matter.

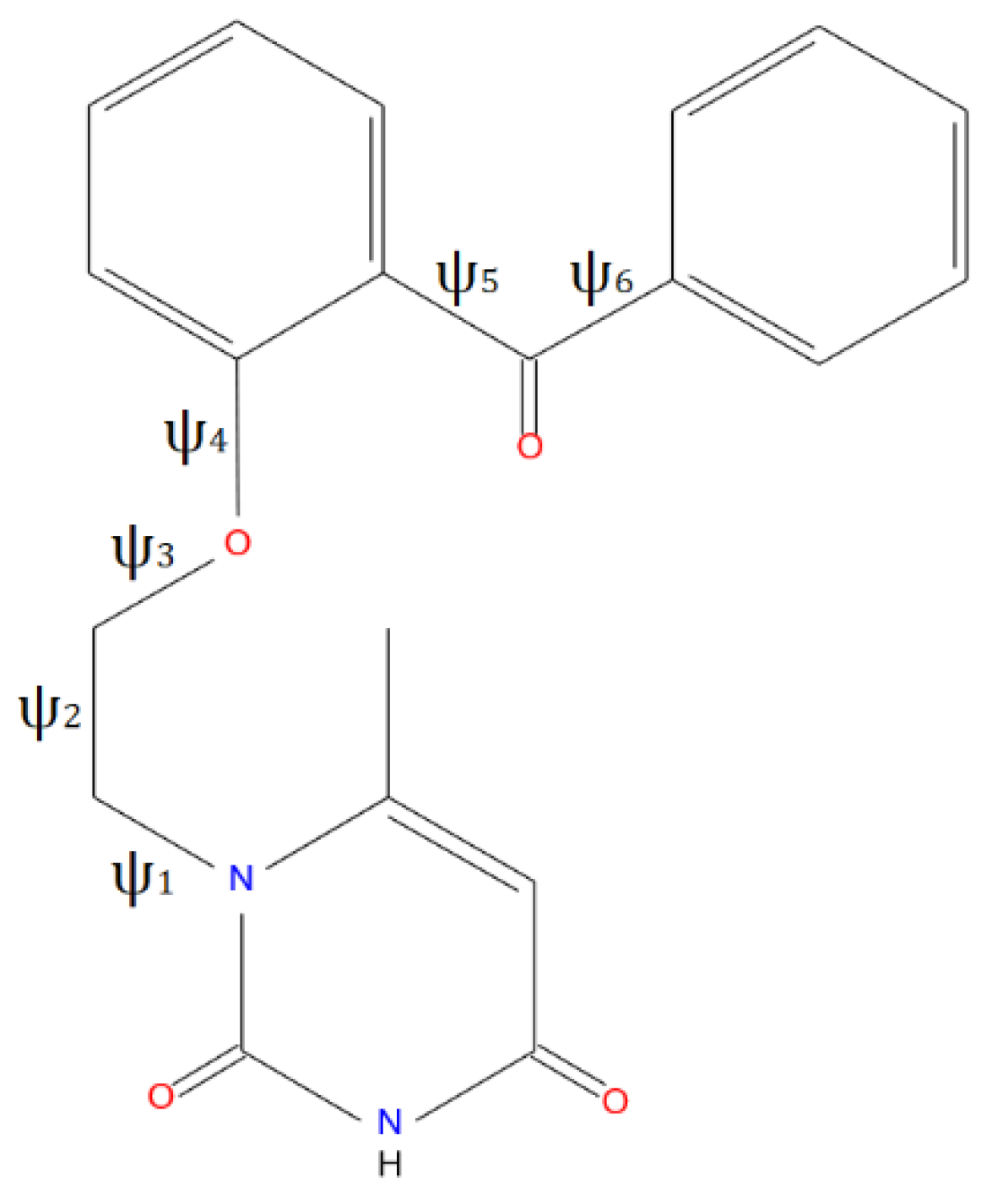

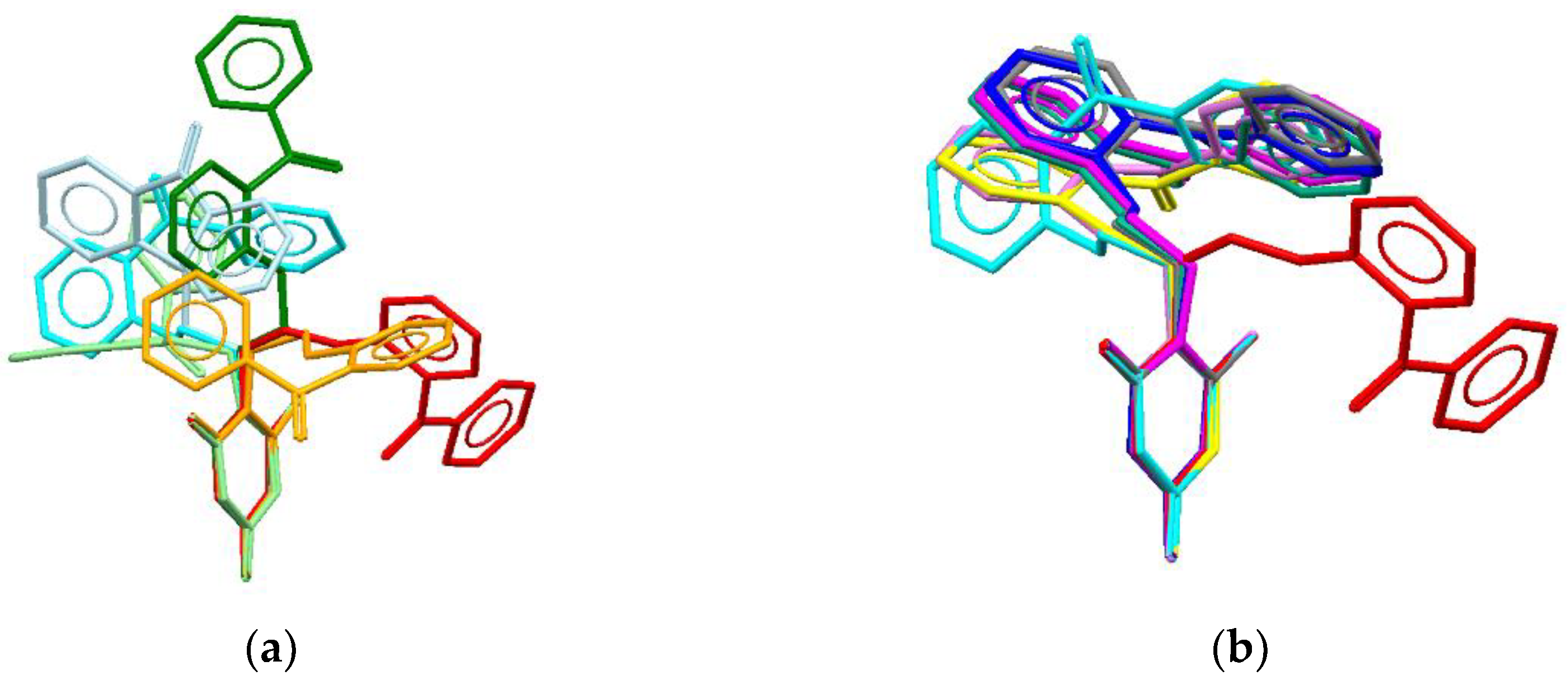

3.2. Molecular Flexibility and Conformational Analysis

Conformation of small flexible molecules in ligand-receptor complexes with biomacromolecules typically differs from that in their solid forms (polymorphs, solvates, cocrystals and salts). We can claim with a high degree of accuracy that an extended or linear conformation is preferable for ligand-receptor complexes, while in crystals of small molecules folded or globular conformations are favorable. Besides, prevalence of particular type of interactions can stabilize an extended or a folded conformation in both crystals and ligand-receptor complexes [

39]. The

VMU-2012-05 molecule contains three rigid aromatic groups connected by several single bonds that allow to change the mutual orientation of the former groups. As a result, the conformational energy can be described as a function of six dihedral angles (

Scheme 1). Accordingly, the conformational analysis of the isolated

VMU-2012-05 molecule reveals four stable conformers (

Table 1). The energy of the least favorable conformation exceeds the energy of the most favorable one by 14.23 kJ/mol. The majority of the conformers are in folded conformation except for the conformer

3 realize. Moreover, for all of them the conformation significantly differs from that found in the crystal structure (

Table 1,

Figure 2a).

In the case of

VMU-2012-05, the conformational changes can be expressed by the values of ψ1-ψ6 angles depicted in

Scheme 1 (the curves of corresponding rotation potentials are presented in

Figures S6–S11 in the ESI). The rotation barriers around the bonds in the oxyethyl moiety exceed 60 kJ/mol. At the same time, the rotation barrier that corresponds to the mutual displacement of two phenyl groups around two bridging C–C bonds is also too high for free rotation in solution (up to 32 kJ/mol). Upon transition of the most stable conformer

4 to the less favorable conformer

1 the ψ angles are changing not significantly, with the exception of ψ

4. Nevertheless, the change in the ψ

4 angle from -7.1 to -109.0° increases the full energy by less than 20 kJ/mol. On the other hand, more than 60 kJ/mol is necessary to change the ψ

3 angle by almost 360° (almost complete rotation around the O–C bond in oxyethyl moiety) and, therefore, to change significantly the mutual orientation of uracil and phenyl moieties. In the case of transition from conformer

4 to another unfavorable conformer

3 it is necessary to overcome several potential barriers as high as 35 kJ/mol. Thus, the conformational changes in

VMU-2012-05 are not fully forbidden but the energies of potential barriers significantly exceed experimental values of individual intermolecular interactions in crystal besides the hydrogen bond N2–H2...O2. Hence, a strong hydrogen bond is able to stabilize one of unfavorable conformations in the condensed matter, but the sum of weak interactions occurred between a pair of molecules can also act in a similar manner.

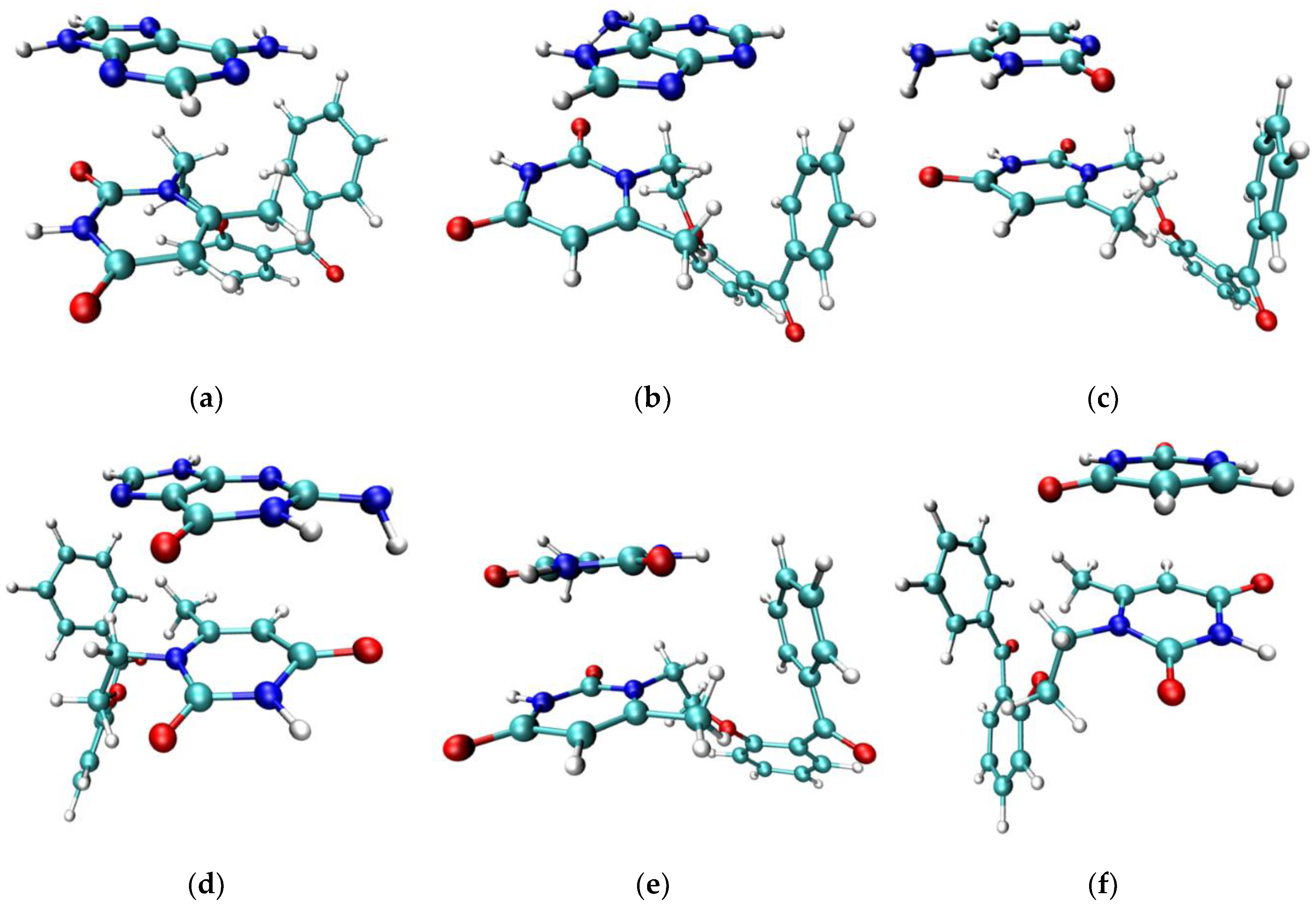

3.3. Modelling the Interactions of VMU-2012-05 in Dimers with Nucleobases

According to the results of macromolecular crystallographic studies, for instance [

40,

41,

42], the molecules of nucleoside inhibitors in its phosphate forms can bind with the fragments of DNA or RNA due to the stacking interactions between π-systems of corresponding nucleobases and the aromatic heterocycle of nucleoside fragment. Here the heterocycle is a chemically modified nucleobase fragment usually situated on top of the RNA or DNA fragment, so its’ role can be identified as the key factor that prevents the process of RNA or DNA transcription. The existence of such interactions in the case of non-nucleoside inhibitors of HIV is an open question because in the most of the complexes with the HIV inhibitors the corresponding molecules were found in the region far from any DNA or RNA fragments. According to ref. [

43] the role of the non-nucleoside inhibitor is to lock the HIV polymerase in an inactive conformation by means of weak intermolecular interactions. On the other hand, numerous examples of stacking interactions of the uracil fragment with nucleosides are observed in the Cambridge Structural Database. In order to evaluate stability of stacking interactions between

VMU-2015-05 and DNA/RNA we optimized dimers constructed by the stacking interaction between the 5-methyluracil fragment of one molecule of

VMU-2012-05 with one molecule of adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine or uracil.

Initial geometry of

VMU-2015-05 molecule in the stacked dimers was the most stable conformation

4. After optimization of geometry the conformation of

VMU-2012-05 has changed due to rotation of phenyl group around C–C bonds that correspond to changes of ψ

5 and ψ

6 torsion angles (

Figure 2b). However, the dimers remain to be connected by stacking interactions between the nucleoside cycles (

Figure 3). The analysis of the potential energy surface reveals two stable stacked dimers for adenosine and only one for the other nucleobases. Two stacked dimers with the adenosine molecule differ by the nature of the stacking interactions. In the first stacked dimer,

VMU-2012-05·with adenine (dimer

1), we found the stacking interaction between the uracil moiety of

VMU-2012-05 and the pyrimidine cycle of adenosine. In the second stacked dimer,

VMU-2012-05· adenine (dimer

2) the 1,3-pyrazol cycle of adenosine participates in stacking interaction instead of pyrimidine one.

In general, the mutual orientations of the uracil moiety and the heterocyclic fragment of nucleobases are non-parallel. The characteristic angle φ between the planes of the cycles involved in stacking interaction, varies in the wide range (1.968 – 12.923°). At the same time, the values of the distances between the centroids of the involved cycles and the inter-centroid shifts fall in the ranges 3.51 – 3.67 and 0.41 – 1.80 Å, respectively, that is indicative for rather high extent of overlapping of the corresponding π-systems. Energies of dissociation of

VMU-2012-05·adenine (dimer

2),

VMU-2012-05·cytosine and

VMU-2012-05·guanine dimers are significantly lower than those of other stacking dimers (

Table 2). The QTAIM analysis of stacked dimers demonstrates that the additional stabilization is provided by the hydrogen bond between the amino group bonded to the pyrimidine cycle of nucleobase and the carbonyl group of

VMU-2012-05(

Tables S4–S6, ESI). The effect of additional stabilization due to hydrogen bonding is assessed differently by B3LYP and DLPNO-CCDC(T) methods in the case of dimer

1 and dimer

2. In the case of the other stacked dimers, both methods gave nearly the same results.

Thus, the results of the calculations of the isolated stacked dimers of VMU-2012-05 allowed us to assume that the binding of this nonnucleoside anti-HIV agent with DNA or RNA can be rather strong even at absence of H-bonding. However, to afford the possibility of such interaction, the molecule of VMU-2012-05 should noticeably change conformation.

3.4. Modelling the Interactions of VMU-2012-05 with Receptor

The majority of previously reported reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors, both based on uracyl derivatives [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], and others [

50,

51,

52] were reported to occupy the same binding site forming a hydrogen bond with Lys101 and a number of hydrophobic interactions with Tyr181, Tyr188 and Trp229 residues. Taking into account that the

VMU-2012-05 belongs to 1,6-disubstituted uracyles, we can assume that the

VMU-2012-05 molecule can occupy the same binding site as TNK-651 [

45], HEF [

46], KRV [

47], MKC [

48] and GCA [

49] ligands. To mimic the interaction of

VMU-2012-05 with a protein receptor, the 1S1V structure of L100I mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase as receptor with its potential inhibitor TNK-651 (6-benzyl-1-benzyloxymethyl-5-isopropyluracyl) [

44] was taken from PDB as a starting model.

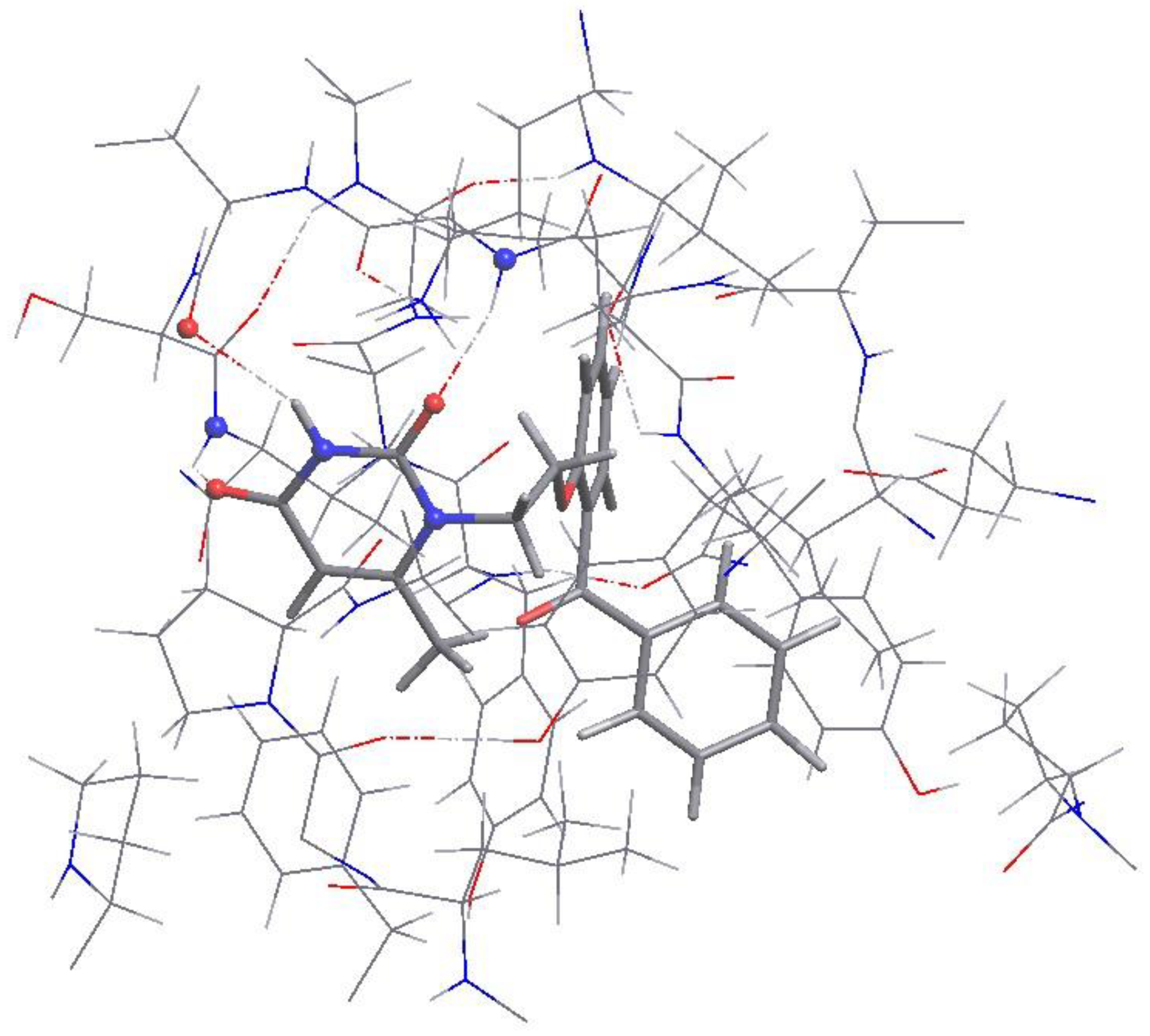

The overall conformation of

VMU-2012-05 molecule after optimization is close to those in the most unfavorable conformer

1 with an exception of rotation along the N1–C5 bond (

Table 1,

Figure 2). The complex resulting from QM/MM calculations possesses intermolecular distances between the receptor and

VMU-2012-05 typical for molecular crystals of organic compounds. Thus, the geometry of the calculated model is suitable for the subsequent analysis of the interactions between

VMU-2012-05 and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in terms of QTAIM theory and NCI method. We found three strong hydrogen bonds between the uracil moiety of ligand and the receptor residues (

Figure 4). These are N-H...O bonds where

VMU-2012-05 acts as a donor of N-H or acceptor of O=C groups for H-bonding with the LYS103 (instead of expected LYS101), VAL179 and VAL106 residues. Interesting that in X-rayed RT complexes with inhibitors, the amide groups of VAL179, VAL106 and SER105 residues are often do not take part in intraprotein H-bonds or take part in H-bonding with water molecules. Thus, geometry optimization affected not only ligand, but also macromolecular 3D conformations. The other interactions between

VMU-2012-05 and the peptide chains are hydrophobic as expected (

Figure 4,

Table S16, ESI). All H...O distances corresponding to the C-H...O interactions between ligand and receptor vary in the range 2.39-2.51 Å. At that, the most of the H...H distances between ligand and receptor exceed 2.14 Å, only one short H...H distance (2.022 Å) is observed that can correspond to the interaction between methyl group of isoleucine residue ILE96 and the methylene bridge of

VMU-2012-05. No stacking interactions were found in the complex.

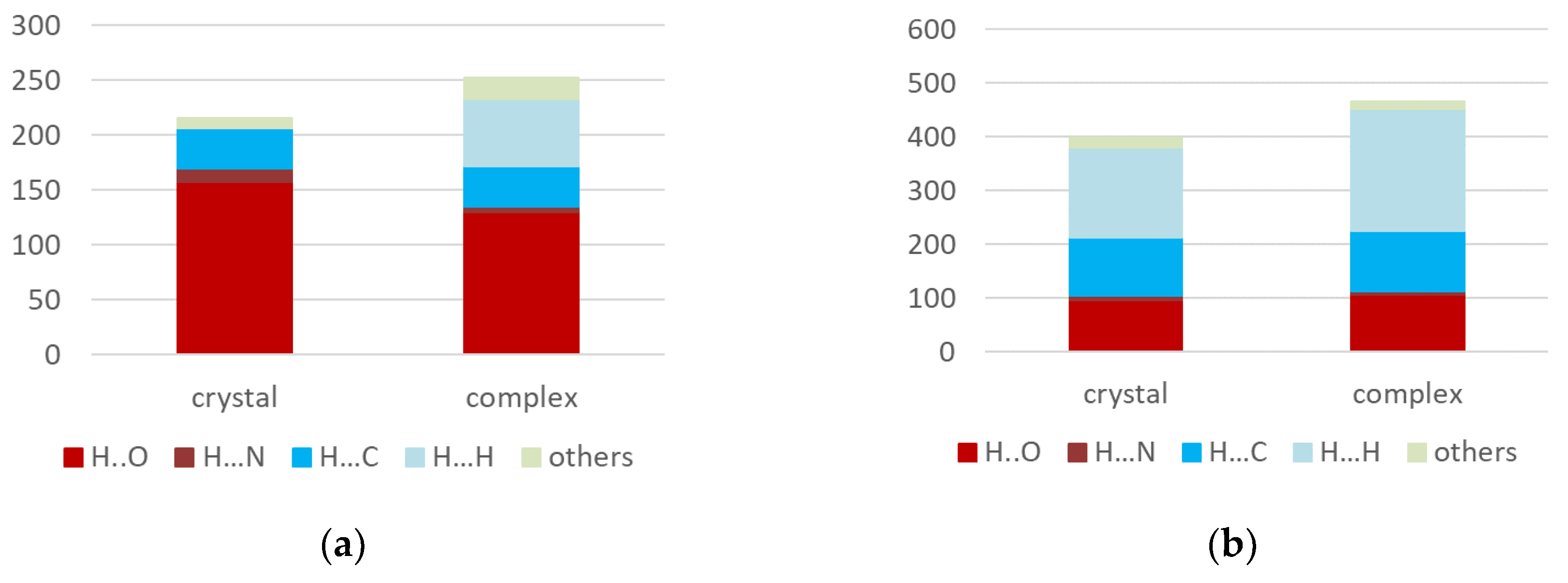

To calculate the electron density function, the QM region was expanded thus to cover all possible interactions of

VMU-2012-05 with the surrounding aminoacid residues. Subsequent study of the calculated electron density in terms of QTAIM theory has revealed that the strongest interactions are the hydrogen N-H...O bonds between uracil moiety of

VMU-2012-05 and LYS103/VAL179/VAL106 residues, respectively (-23.7, -15.6 and -13.8 kJ/mol,

Table S16, ESI). Note, that these interactions in previously reported complexes All interactions of other types (C-H...O, C-H...N, C-H...π, H...H, O...O, O...N) are noticeably weaker (-0.7 – -12.5 kJ/mol). The sum of energies of all interatomic interactions, i.e. ligand-receptor binding energy, is equal to -252.5 kJ/mol, which is 37.9 kJ/mol lower than the value of lattice energy. This discrepancy comes mainly from the additional H…H bonding and O…O plus the O…N bonding observed only in the complex. As a result, total energy of the hydrophobic interactions was higher in the complex, while the total energy of the hydrophilic hydrogen bonds decreased probably due to the larger cage occupied by

VMU-2012-05. Indeed, in the crystal and the complex the volume of the molecular Voronoi polyhedron was found to be 416 and 446 Å

3. The Voronoi tessellation also indicates increase in the contribution of hydrophobic interactions in complex as compared with crystal, although in general it underestimates the role of hydrophilic interactions (

Figure 5b).

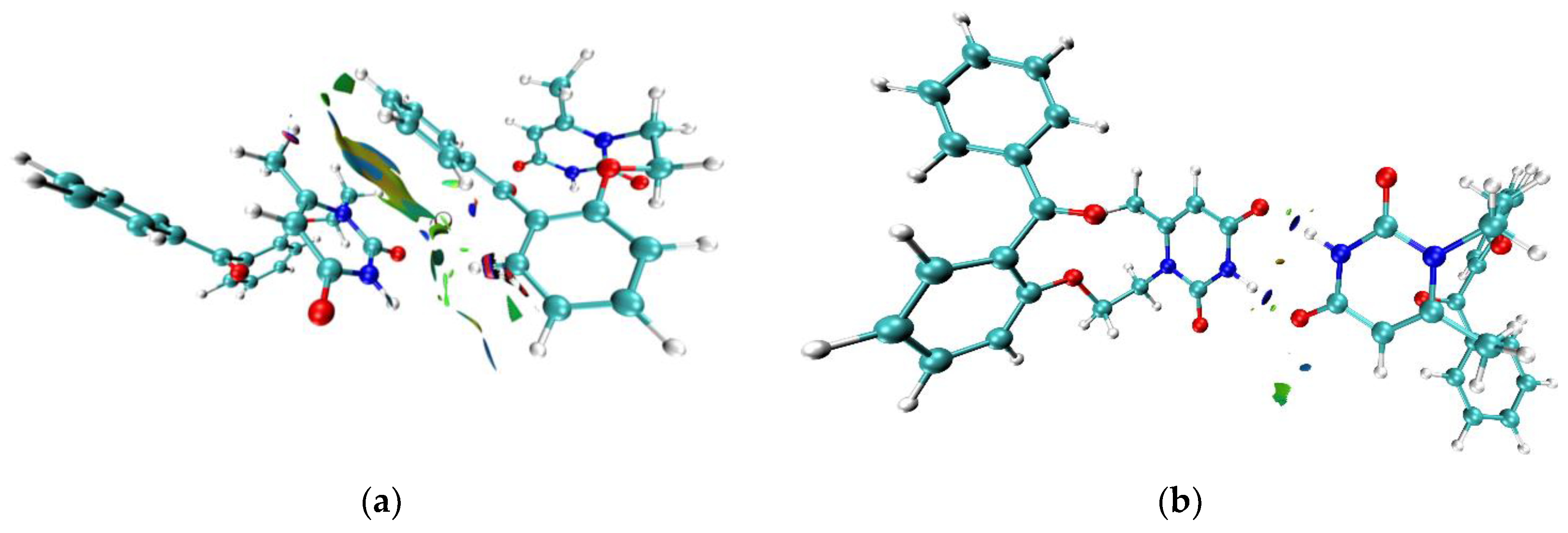

3.5. NCI Study of Intermolecular Interaction in Crystal, Stacking Dimers and the Model of Ligand-Receptor Interaction

NCI analysis was performed for pure

VMU-2012-5, its′ dimers with nucleobases, and in the ligand–receptor complex. The study of weak interactions in terms of NCI and the comparison with the results of QTAIM study reveals qualitative agreement between the positions of

bcps and RDG maxima. In addition, the shape and the volume of RDG maxima gives us complimentary information about the area of interaction between the atomic domains. In crystal of

VMU-2012-05 the stacking interaction corresponds to the shapeless planar isosurface (

Figure 6a). The most of the isosurface area is colored by light brown that is characteristic for the van-der-Waals interactions. Nevertheless, approximately one fourth of the corresponding area is light blue that reveals the attractive interactions between two atomic pairs (N2...C2 and H...C) of uracil and phenyl moieties, respectively. The intramolecular C-H...O bond can be characterized as mostly van-der-Waals type. In contrast to the stacking interaction and the C-H...O bond, the attractive nature is quite expectedly demonstrated for intermolecular N-H...O bonds (

Figure 6b). In the dimers between

VMU-2012-05 and nucleobases the study of RDG clearly reveals the role of stacking interaction and strong hydrogen bond in its stabilization. The stacking interaction in all studied dimers is characterized by rather large interaction area (

Figures S27–S29, ESI). For instance, in dimer

1 the stacking interaction can be distinguished as number of van-der-Waals interactions between the nitrogen and the carbon atoms of the adenine and the uracil moiety of

VMU-2012-05 assisted by the weak C-H...N bond. In more stable dimers

VMU-2012-05·adenine (dimer

2) and

VMU-2012-05·guanine the stacking interaction is assisted by one strong N-H...O and several weak H-bonds of other types. In addition, several intramolecular interactions in

VMU-2012-05 are observed that can be attributed as the C-H…π and C-H...O interactions.

The binding of

VMU-2012-05 with model HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is somewhat different as compared to the corresponding crystal structure and the stacked dimers. The

VMU-2012-05 molecule participates in several H-bonds of attractive character including two C-H...O bonds. At the same time, there are a lot of interactions of van-der-Waals type that play key role in the ligand-receptor binding (

Figure S30, ESI).

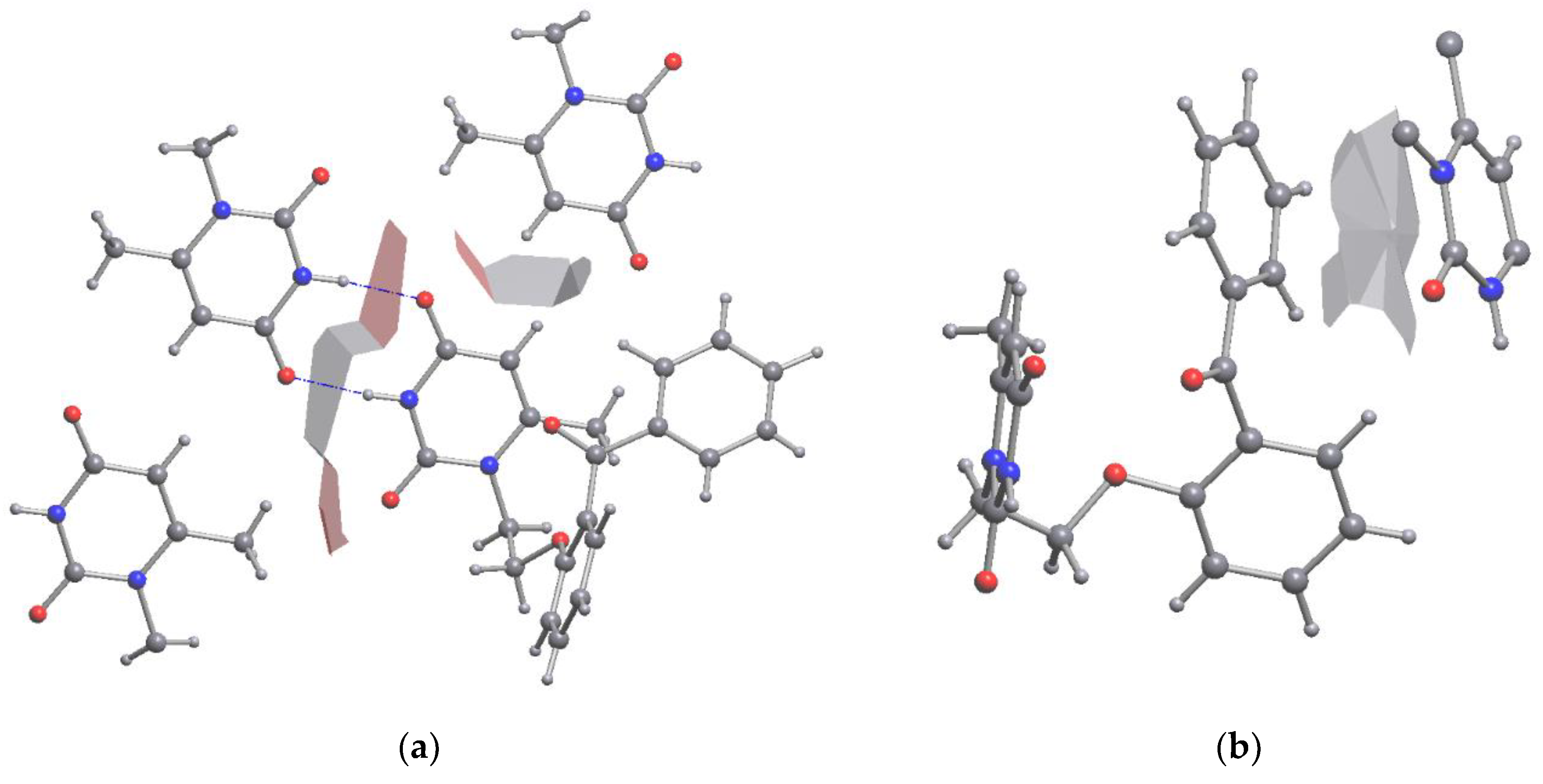

Similar visualization of the intermolecular surface between the interacted molecules can be obtained from the molecular Voronoi surfaces. It also reveals both stacking and H-bonded pairwise interactions both in the crystal (

Figure 7) and in the ligand-receptor complex (

Figure 8). The view of surfaces is similar with that obtained from the RDG function, demonstrating the potential of the molecular Voronoi surfaces for fast low-resource demanding analysis of the closest environment of molecules in any crystal, solid and associate.

4. Conclusions

In this work we demonstrate that even for molecules with large number of potential donors and acceptors of hydrogen bonding, the role of weak van der Waals interactions in the stabilization of its associates with biomacromolecules should not be underestimated. Sum of energies of these interactions can be large enough to stabilize an unfavorable conformation of a flexible molecule, and is often higher than energy of a strong, but individual interaction such as a hydrogen bond. For VMU-2012-05 molecule, the conformation analysis reveals four conformers with relative energies 0 – 14.2 kJ/mol. None of them were found in the condensed phases, either experimental (crystal), or theoretical (six dimers with nucleosides and a complex with HIV-1 reverse transcriptase). The experimental folded conformation is supported by the C–H…O, C…O and C…C intramolecular interactions with the overall energy of -13.0 kJ/mol, while all theoretical conformations are extended due to the rotation along oxyethyl moiety. Analysis of VMU-2012-05 : nucleoside associates demonstrates that overall (total) energies of C…C, N…C and C…H interactions between the nucleoside and the phenyl rings can reach -14.0 kJ/mol that is comparable with the energy of N–H…O hydrogen bonds observed in the crystal and calculated for the complex with HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (-7.5 – -29.5 kJ/mol). Counterintuitively, despite the number of H-bonds in the ligand–receptor complex exceeds that in the crystal due to the presence of numerous donors of H-bonding in the binding pocket of a macromolecule, the overall energy of N-H…O bonds in the crystal and in a complex is nearly the same. Stacking interactions in the binding pocket are also absent. Instead, the sum energy of H…H interactions which are typically ignored during discussion of structure-forming contacts increases from -0.9 to -61.7 kJ/mol instead. This fact indicates necessity of comparative analysis of full continuum of intermolecular interactions in both materials and biomolecules, that at the moment can be performed only by means of ED-based methods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, crystallographic data and details of refinement; relaxed scans of torsion angles; the information about interactions responsible for dimer stabilization and corresponding energies; the interactions between and protein receptor mode. CCDC 2380926-2380927 contain crystallographic information for IAM and MM refinement of this structure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.K.; formal analysis, A.R.R., A.I.S., A.A.K.; investigation, A.R.R., A.I.S., E.V.P., A.V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.R.; A.A.K., A.V.V.; writing—review and editing, A.A.K., A.V.V.; visualization, A.R.R., A.A.K., A.V.V.; funding acquisition, A.A.K. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 20-13-00241).

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Dr. E. A. Jain (Moscow State University) for presenting of powder sample of VMU-2012-05.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vega-Hissi, E.G.; Tosso, R.; Enriz, R.D.; Gutierrez, L.J. Molecular Insight into the Interaction Mechanisms of Amino-2H-Imidazole Derivatives with BACE1 Protease: A QM/MM and QTAIM Study. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015, 115, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrenova, M.G.; Krivitskaya, A.V.; Tsirelson, V.G. The QM/MM-QTAIM Approach Reveals the Nature of the Different Reactivity of Cephalosporins in the Active Site of L1 Metallo-β-Lactamase. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 7329–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firme, C.L.; Monteiro, N.K.V.; Silva, S.R.B. QTAIM and NCI Analysis of Intermolecular Interactions in Steroid Ligands Binding a Cytochrome P450 Enzyme – Beyond the Most Obvious Interactions. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2017, 1111, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, K.; Jezierska, A. Role of Non-Covalent Interactions in Carbonic Anhydrase I—Topiramate Complex Based on QM/MM Approach. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrenova, M.G.; Levina, E.O.; Tsirelson, V.G. Benchmark Studies of Hydrogen Bond Governing Reactivity of Cephalosporins in L1 Metallo-β-Lactamase: Efficient and Reliable QSPR Equations. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2021, 121, e26451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levina, E.O.; Khrenova, M.G.; Astakhov, A.A.; Tsirelson, V.G. Revealing Electronic Features Governing Hydrolysis of Cephalosporins in the Active Site of the L1 Metallo-β-Lactamase. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 8664–8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerov, F.F.; Novikov, M.S. Method for Producing Monosubstituted Derivatives of Uracil 2018.

- Вавилoва, В.А.; Шекунoва, Е.В.; Джайн (Кoрсакoва), Е.А.; Балабаньян, В.Ю.; Озерoв, А.А.; Макарoва, М.Н.; Макарoв, В.Г. ЭКСПЕРИМЕНТАЛЬНОЕ ИЗУЧЕНИЕ ТОКСИЧЕСКИХ СВОЙСТВ ПРЕПАРАТА VMU-2012-05 – ОРИГИНАЛЬНОГО НЕНУКЛЕОЗИДНОГО ИНГИБИТОРА ОБРАТНОЙ ТРАНСКРИПТАЗЫ ВИЧ-1. Фармация И Фармакoлoгия 2021, 9, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, A.N.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Simenel, A.A. Synthesis, Structure of 5,7-Dimethyl-3-Ferrocenyl-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Pyrazolo- [1,2-a]-Pyrazol-4-Ium Tetrafluoroborate. DFTB Calculations of Interaction with DNA. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1251, 132070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro. Version 1.171.41.106a. 2021.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT – Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J. a. K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.K.; Coppens, P. Testing Aspherical Atom Refinements on Small-Molecule Data Sets. Acta Crystallogr. A 1978, 34, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsch, C.; Guillot, B.; Lagoutte, A.; Lecomte, C. Advances in Protein and Small-Molecule Charge-Density Refinement Methods Using MoPro. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2005, 38, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H.; Bruno, I.J. Bond Lengths in Organic and Metal-Organic Compounds Revisited: X—H Bond Lengths from Neutron Diffraction Data. Acta Crystallogr. B 2010, 66, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, A.Ø. SHADE Web Server for Estimation of Hydrogen Anisotropic Displacement Parameters. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.; Abramov, Y.A.; Coppens, P. Density-Optimized Radial Exponents for X-Ray Charge-Density Refinement from Ab Initio Crystal Calculations. Acta Crystallogr. A 2001, 57, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meindl, K.; Henn, J. Foundations of Residual-Density Analysis. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, J.; Meindl, K. More about Systematic Errors in Charge-Density Studies. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv. 2014, 70, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An Update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Becker, U.; Riplinger, C. The ORCA Quantum Chemistry Program Package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 224108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From Visualization to Analysis, Design and Prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.J.; Grabowsky, S.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. Accurate and Efficient Model Energies for Exploring Intermolecular Interactions in Molecular Crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 4249–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonk, M.L.; Cole, J.C.; Hartshorn, M.J.; Murray, C.W.; Taylor, R.D. Improved Protein–Ligand Docking Using GOLD. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2003, 52, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, K.; Foloppe, N.; Baker, C.M.; Denning, E.J.; Nilsson, L.; MacKerell, A.D.Jr. Optimization of the CHARMM Additive Force Field for DNA: Improved Treatment of the BI/BII Conformational Equilibrium. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerell, A.D.Jr.; Feig, M.; Brooks, C.L. Improved Treatment of the Protein Backbone in Empirical Force Fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Clarendon Press, 1994; ISBN 978-0-19-855865-1.

- Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A.J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, M.A.; Ribone, S.R.; Moroni, G.N.; Briñón, M.C. Binding to Human Serum Albumin of Zidovudine (AZT) and Novel AZT Derivatives. Experimental and Theoretical Analyses. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 2779–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Barua, H.; Jyothi, V.G.S.S.; Dhondale, M.R.; Nambiar, A.G.; Agrawal, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Shastri, N.R.; Kumar, D. Cocrystals by Design: A Rational Coformer Selection Approach for Tackling the API Problems. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korlyukov, A.A.; Stash, A.I.; Romanenko, A.R.; Trzybiński, D.; Woźniak, K.; Vologzhanina, A.V. Ligand-Receptor Interactions of Lamivudine: A View from Charge Density Study and QM/MM Calculations. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korlyukov, A.A.; Malinska, M.; Vologzhanina, A.V.; Goizman, M.S.; Trzybinski, D.; Wozniak, K. Charge Density View on Bicalutamide Molecular Interactions in the Monoclinic Polymorph and Androgen Receptor Binding Pocket. IUCrJ 2020, 7, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.; Molins, E.; Lecomte, C. Hydrogen Bond Strengths Revealed by Topological Analyses of Experimentally Observed Electron Densities. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 285, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, I.; Alkorta, I.; Espinosa, E.; Molins, E. Relationships between Interaction Energy, Intermolecular Distance and Electron Density Properties in Hydrogen Bonded Complexes under External Electric Fields. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2011, 507, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vologzhanina, A.V.; Ushakov, I.E.; Korlyukov, A.A. Intermolecular Interactions in Crystal Structures of Imatinib-Containing Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoletti, N.; Chan, A.H.; Schinazi, R.F.; Anderson, K.S. Post-Catalytic Complexes with Emtricitabine or Stavudine and HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Reveal New Mechanistic Insights for Nucleotide Incorporation and Drug Resistance. Molecules 2020, 25, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Martinez, S.E.; Arnold, E. Structural Insights into HIV Reverse Transcriptase Mutations Q151M and Q151M Complex That Confer Multinucleoside Drug Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, 10.1128/aac.00224-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, V.; Vyas, R.; Fowler, J.D.; Efthimiopoulos, G.; Feng, J.Y.; Suo, Z. Structural and Kinetic Insights into Binding and Incorporation of L-Nucleotide Analogs by a Y-Family DNA Polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 9984–9995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnouf, R.; Ren, J.; Ross, C.; Jones, Y.; Stammers, D.; Stuart, D. Mechanism of Inhibition of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase by Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995, 2, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 2-Arylalkylthio-5-Iodine-6-Substituted-Benzyl-Pyrimidine-4(3H)-Ones as Potent HIV-1 Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. Molecules 2014, 19, 7104–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Nichols, C.E.; Chamberlain, P.P.; Weaver, K.L.; Short, S.A.; Stammers, D.K. Crystal Structures of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptases Mutated at Codons 100, 106 and 108 and Mechanisms of Resistance to Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 336, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Esnouf, R.; Garman, E.; Somers, D.; Ross, C.; Kirby, I.; Keeling, J.; Darby, G.; Jones, Y.; Stuart, D.; et al. High Resolution Structures of HIV-1 RT from Four RT–Inhibitor Complexes. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995, 2, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.L.; Son, J.C.; Guo, H.; Im, Y.-A.; Cho, E.J.; Wang, J.; Hayes, J.; Wang, M.; Paul, A.; Lansdon, E.B.; et al. N1-Alkyl Pyrimidinediones as Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Ren, J.; Esnouf, R.M.; Willcox, B.E.; Jones, E.Y.; Ross, C.; Miyasaka, T.; Walker, R.T.; Tanaka, H.; Stammers, D.K.; et al. Complexes of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase with Inhibitors of the HEPT Series Reveal Conformational Changes Relevant to the Design of Potent Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Ren, J.; Tanaka, H.; Baba, M.; Okamato, M.; Stuart, D.I.; Stammers, D.K. Design of MKC-442 (Emivirine) Analogues with Improved Activity Against Drug-Resistant HIV Mutants. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 4500–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapkouski, M.; Tian, L.; Miller, J.T.; Le Grice, S.F.J.; Yang, W. Complexes of HIV-1 RT, NNRTI and RNA/DNA Hybrid Reveal a Structure Compatible with RNA Degradation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Kim, M.-S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, W. Structure of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Cleaving RNA in an RNA/DNA Hybrid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdon, E.B.; Brendza, K.M.; Hung, M.; Wang, R.; Mukund, S.; Jin, D.; Birkus, G.; Kutty, N.; Liu, X. Crystal Structures of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase with Etravirine (TMC125) and Rilpivirine (TMC278): Implications for Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4295–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scheme 1.

Schematic view of VMU-2012-05 molecule and its′ torsion angles.

Scheme 1.

Schematic view of VMU-2012-05 molecule and its′ torsion angles.

Figure 1.

Molecular view of VMU-2012-05 in representation of atoms with thermal ellipsoids (drawn at p = 70%).

Figure 1.

Molecular view of VMU-2012-05 in representation of atoms with thermal ellipsoids (drawn at p = 70%).

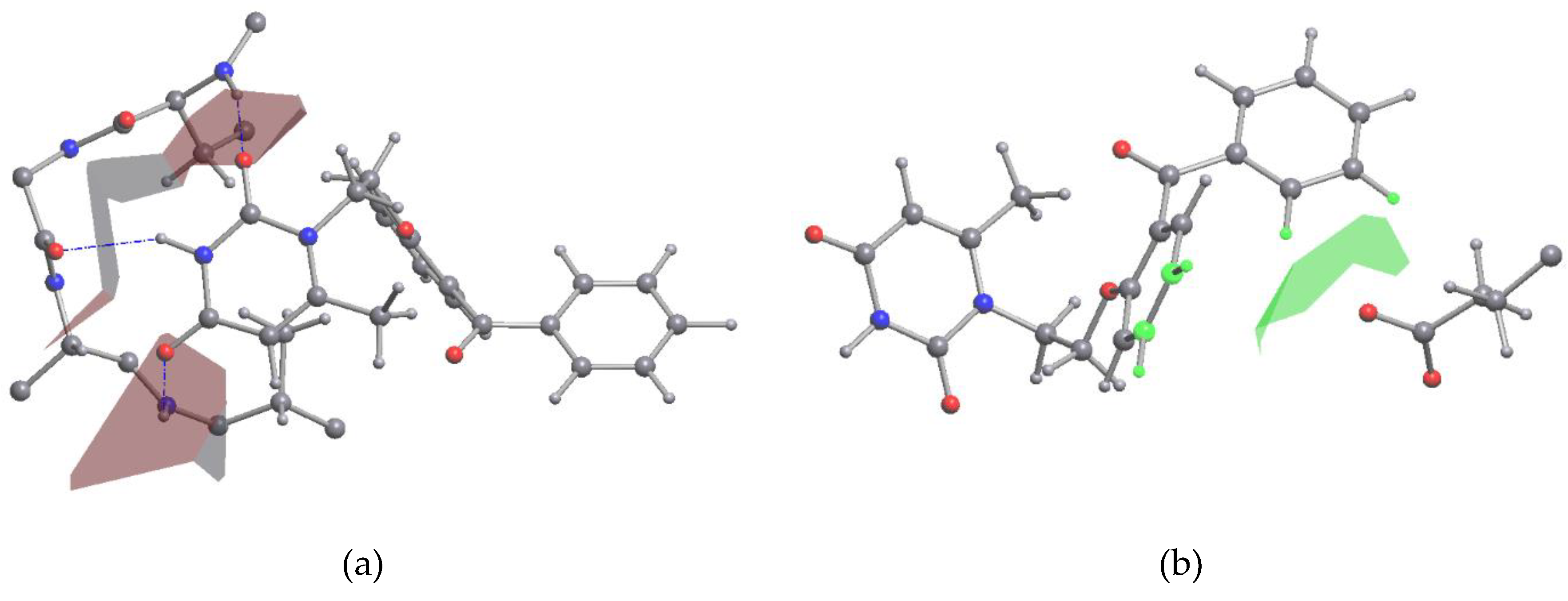

Figure 2.

Conformations of VMU-2012-05 in crystal (red), ligand – receptor complex (light-green), and (a) isolated conformers conformer1 (orange), conformer2 (light-blue), conformer3 (green), conformer4 (cyan), or (b) dimers with nucleosides dimer1 (yellow), dimer2 (violet), dimer VMU-2012-05·cytosine (blue), dimer VMU-2012-05·guanine (magenta), dimer VMU-2012-05·thymine (grey) and dimer VMU-2012-05·uracil (teal). Atoms of 6-methyluracil are overlaid.

Figure 2.

Conformations of VMU-2012-05 in crystal (red), ligand – receptor complex (light-green), and (a) isolated conformers conformer1 (orange), conformer2 (light-blue), conformer3 (green), conformer4 (cyan), or (b) dimers with nucleosides dimer1 (yellow), dimer2 (violet), dimer VMU-2012-05·cytosine (blue), dimer VMU-2012-05·guanine (magenta), dimer VMU-2012-05·thymine (grey) and dimer VMU-2012-05·uracil (teal). Atoms of 6-methyluracil are overlaid.

Figure 3.

General view of stacking dimers VMU-2012-05 and (a) adenine (dimer1), (b) adenine (dimer2), (c) cytosine, (d) guanine, (e) thymine, and (f) uracyl.

Figure 3.

General view of stacking dimers VMU-2012-05 and (a) adenine (dimer1), (b) adenine (dimer2), (c) cytosine, (d) guanine, (e) thymine, and (f) uracyl.

Figure 4.

Fragment of VMU-2012-05 and L100I mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complex after geometry optimization. Hydrogen bonds are shown with dashed lines. VMU-2012-05 and peptide chains are shown with sticks and wire models. O: red; N: blue; C: grey; H: white.

Figure 4.

Fragment of VMU-2012-05 and L100I mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complex after geometry optimization. Hydrogen bonds are shown with dashed lines. VMU-2012-05 and peptide chains are shown with sticks and wire models. O: red; N: blue; C: grey; H: white.

Figure 5.

Contribution of different types of interactions to (a) the sum energy of intermolecular interactions and (b) the surface of molecular Voronoi polyhedron.

Figure 5.

Contribution of different types of interactions to (a) the sum energy of intermolecular interactions and (b) the surface of molecular Voronoi polyhedron.

Figure 6.

3D isosurface of RDG function (0.4 a.u.) of VMU-2012-05 in the crystal colored according to the sign sign(λ2)ρ(r) function (0.03 - –0.03 a.u.). Negative values (the regions corresponding to attractive interactions) shown by blue color while positive ones shown by red color. The interactions of van-der-Waals type colored by green and yellow colors.

Figure 6.

3D isosurface of RDG function (0.4 a.u.) of VMU-2012-05 in the crystal colored according to the sign sign(λ2)ρ(r) function (0.03 - –0.03 a.u.). Negative values (the regions corresponding to attractive interactions) shown by blue color while positive ones shown by red color. The interactions of van-der-Waals type colored by green and yellow colors.

Figure 7.

3D Fragment of the molecular Voronoi polyhedron of VMU-2012-05 in crystal. (left) H-Bonds between uracil moieties, (b) the stacking between the terminal phenyl cycle of VMU-2012-05 and the uracyl ring.

Figure 7.

3D Fragment of the molecular Voronoi polyhedron of VMU-2012-05 in crystal. (left) H-Bonds between uracil moieties, (b) the stacking between the terminal phenyl cycle of VMU-2012-05 and the uracyl ring.

Figure 8.

3D Fragment of molecular Voronoi polyhedron of VMU-2012-05 in region of binding pocket. (a) H-Bonds between aminoacid residues and uracil moiety, (b) binding between terminal phenyl cycle of VMU-2012-05 and carbonyl atom of aminoacid residue.

Figure 8.

3D Fragment of molecular Voronoi polyhedron of VMU-2012-05 in region of binding pocket. (a) H-Bonds between aminoacid residues and uracil moiety, (b) binding between terminal phenyl cycle of VMU-2012-05 and carbonyl atom of aminoacid residue.

Table 1.

Dihedral angles and relative energies of VMU-2012-05 conformers.

Table 1.

Dihedral angles and relative energies of VMU-2012-05 conformers.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Crystal |

QM/MM |

| ψ1(C1-N1-C5-C6) |

98.851 |

-82.302 |

83.166 |

-78.978 |

79.860 |

105.354 |

| ψ2(N1-C5-C6-O3) |

-65.998 |

179.135 |

179.951 |

-65.129 |

62.106 |

-77.883 |

| ψ3(C5-C6-O3-C7) |

176.753 |

-158.865 |

84.448 |

-173.449 |

-168.290 |

163.802 |

| ψ4(C6-O3-C7-C8) |

-7.116 |

-30.347 |

-5.051 |

-109.040 |

-30.557 |

-2.086 |

| ψ5(C11-C12-C13-O4) |

-50.403 |

-43.700 |

123.764 |

43.704 |

112.074 |

-25.934 |

| ψ6(C15-C14-C13-O4) |

159.266 |

155.879 |

161.982 |

-150.230 |

-177.159 |

-172.634 |

| Relative energy, kJ/mol |

14.23 |

4.12 |

14.04 |

0 |

|

|

Table 2.

The structural parameters and energies of dissociation of stacked dimers.

Table 2.

The structural parameters and energies of dissociation of stacked dimers.

| Stacked dimer |

R1, Å |

R2, Å |

φ, ° |

ΔE1, kJ/mol |

ΔE2, kJ/mol |

|

VMU-2012-05·adenine (dimer1) |

3.554 |

1.412 |

1.968 |

-48.07 |

-54.33 |

|

VMU-2012-05·adenine (dimer2) |

3.586 |

1.660 |

9.394 |

-68.42 |

-60.74 |

|

VMU-2012-05·cytosine |

3.507 |

1.103 |

12.923 |

-77.81 |

-79.41 |

|

VMU-2012-05·guanine |

3.557 |

1.801 |

9.004 |

-76.85 |

-79.54 |

|

VMU-2012-05·thymine |

3.641 |

1.457 |

2.411 |

-42.06 |

-44.37 |

|

VMU-2012-05·uracil |

3.663 |

0.408 |

3.541 |

-53.15 |

-53.49 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).