1. Introduction

Hand-arm vibration exposure is an important risk factor in the workplace. Long-term exposure to hand-arm vibration may lead to a variety of pathological changes in the upper limbs, including vascular, neurological, and musculoskeletal disorders [

1]. The complex of these disorders is known as hand-arm vibration syndrome (HAVS) [

1].

According to the ISO frequency weighting curve for quantifying hand-arm vibration exposure, vibration-induced adverse health effects are believed to be mainly concentrated in the frequency range between 16 and 1250 Hz [

2]. Although early studies showed that both low and high frequency vibration can lead to impaired blood circulation and subsequent tissue damage in the upper extremities [

3], more recent studies indicate frequency-range-specific effects of hand-arm vibration exposure in different human physiological systems [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Experimental rat tail studies and some epidemiological evidence have shown that the effect of vibration exposure on the peripheral vascular and sensorineural systems is more pronounced in the higher frequency range above 100 Hz [

4,

6,

7]. However, biomechanical experiments suggest that vibration-induced musculoskeletal damage is more likely to occur in the low frequency range below 50 Hz due to the resonant frequency of bone [

8].

Although the theory of a frequency-range-specific effect of hand-arm vibration on the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders is widely accepted in the scientific community, no epidemiological data are available to date to support this hypothesis. In order to quantitatively assess the effect of frequency-range-specific hand-arm vibration exposure on the risk of musculoskeletal disorders, we performed an analysis among the study sample of the German Hand-Arm Vibration Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Study Population

The German Hand-Arm Vibration Study is a multicenter industry-based case-control study conducted between January 1, 2010 and November 30, 2021. The design and description of the study population have been previously published in detail [

9]. Briefly, 209 male cases and 614 male controls were recruited from members of the German Social Accident Insurance institutions in the construction, underground coal mining, woodworking, and metal working industries.

The cases are patients with musculoskeletal disorders who were suspected by local physicians of having the legal occupational disease with the number 2103 (German: BK No. 2103) because of their work history involving exposure to hand-arm vibration. Occupational disease no. 2103 is a group of musculoskeletal disorders defined as including one of the following six clinical diagnoses:

The controls were selected as a random sample of all types of newly reported compensable occupational injuries. They were matched to the cases by gender, birth year, industrial sectors, and reporting years. As all cases were selected to have jobs involving exposure to hand-arm vibration, controls were also randomly selected from those with jobs involving exposure to hand-arm vibration.

2.2. Equipment-Exposure-Database for Quantifying Hand-Arm-Vibration Exposure

As described previously [

9], an exposure database for power tool vibrations for quantifying hand-arm vibration exposure has been established and continuously expanded by the German Social Accident Insurance since the mid-1980s. The database currently contains more than 700 hand-held power tools. Their frequency-range-specific vibration values were measured according to standardized industrial hygiene measurement protocols under real operating conditions. The subdivision of the frequency-weighted acceleration is based on the procedure described in the German standard VDI 2057-2 [

10] (see section 2.4 for more information). In addition to the vibration levels, information on the work process and materials used was also documented. This information is essential for quantifying work-related vibration exposures, as vibration exposures vary greatly when technical power tools are used on different working materials and for different purposes.

In addition, product information for the technical power tools (including manufacturer, year, weight, drive type, rated power, rotational speed etc.) was also added to the database, providing this information was available.

2.3. Exposure Assessment Methods

Standardized face-to-face interviews were carried out among cases and controls by specially trained safety engineers from the German Social Accident Insurance institutions. Most of them have more than ten years’ professional experience and have extensive knowledge of the work organization, working process, technical power tools and materials used at workplaces in the related industries.

Besides demographic characteristics, leisure activities, sports, and musculoskeletal comorbidities, the individual work history of all participants was assessed in detail. Exposure assessment focused on technical power tools and working materials used at the workplaces, including daily working hours and the frequency and duration of use of various technical power tools. Combining this information with the above-described equipment-exposure-database < made it possible to estimate and calculate detailed exposure values for the entire period of the previous working life of each study participant.

2.4. Determining Hand-Arm-Vibration Exposure Values

Vibration generated by the technical power tools was measured in three orthogonal directions (x, y, and z) according to international standard ISO 5349-1:2001 [

11]. Vibration values are expressed as accelerations a

hwx, a

hwy, and a

hwz in the three measuring directions under a given specific frequency range. The vibration total value (a

hv) is determined as the root-sum-of-squares of the three component values (a

hwx, a

hwy and a

hwz):

In addition to the vibration total value (ahv), acceleration (ahw) in the direction along the forearm (direction z) is also considered in the exposure-response analyses of this study.

According to the recommended frequency range of 4-1250 Hz and 4-50 Hz in the German standard VDI 2057-2 [

10], four additional frequency ranges (two below and two above 50 Hz) were defined to investigate the frequency-range-specific vibration exposure: 4-20 Hz, 4-31.5 Hz, 4-50 Hz, 4-80 Hz, 4-100 Hz.

The root-mean-squares of the frequency-weighted acceleration (a

hw) for each frequency range are obtained with the aid of electronic frequency filters or calculated by taking the root-mean-squares of the unweighted accelerations (a

hi) and multiplying them by the weighted factor W

hi given in Table B1 of the German standard VDI 2057-2 [

10].

The energy-based averaging of the partial root-mean-squares of the frequency weighted acceleration can be calculated by taking into consideration the associated frequency bands for the parts of the frequency ranges:

ahwi(4-20 Hz) = frequency-range-specific vibration exposure value calculated for spectrum of 4-20 Hz.

ahwi(4-31,5 Hz) = frequency-range-specific vibration exposure value calculated for spectrum of 4-31,5 Hz.

ahwi(4-50 Hz) = frequency-range-specific vibration exposure value calculated for spectrum of 4-50 Hz.

ahwi(4-80 Hz) = frequency-range-specific vibration exposure value calculated for spectrum of 4-80 Hz.

ahwi(4-100 Hz) = frequency-range-specific vibration exposure value calculated for spectrum of 4-100 Hz.

ahwi(4-1250 Hz) = frequency-range-specific vibration exposure value calculated for spectrum of 4-1250 Hz.

The total value ahvi for the respective frequency ranges were calculated accordingly.

Frequency-range-specific daily vibration exposures from using various technical power tools at different time periods of a day are quantified according to international standard ISO 5349-1:2001 [

11] and expressed in terms of 8-hour energy-equivalent root-sum-of-squares of the related frequency-range-specific acceleration magnitude:

where

ahv(8) = daily vibration exposure in three measuring directions

hw(8) = daily vibration exposure in the direction along the forearm

T0 = reference duration of 8 hours (conventional daily working time)

Ti = daily working hours of using power tool i

ahvi = acceleration in three measuring directions of the power tool i

ahwi = acceleration in the direction along the forearm of the power tool i

n = total number of power tools used in a day

The cumulative doses of hand-arm-vibration exposure are expressed as the sum-of-squares of daily vibration exposure over the course of an entire working life:

where

Dhv = cumulative vibration doses in three measuring directions

Dhw = cumulative vibration doses in the direction along the forearm

ahvi(8) = daily vibration exposure of three measuring directions at day i

ahwi(8) = daily vibration exposure in the direction along the forearm at day i

di = number of working days with a daily exposure of ahvi(8) (ahwi(8))

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC. USA).

We quantified the basic characteristics of the cases and controls by using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were described with mean, standard deviation (SD), median and range, and categorical variables with frequencies. Chi-square tests were used to examine the crude differences of categorical variables. Bi- and multivariable conditional logistic regression analyses (with SAS syntax PROC PHREG) were applied to quantify the exposure-response relationship between cumulative hand-arm-vibration exposure doses and the risk of musculoskeletal disorders according to occupational disease No. 2103. Cumulative vibration exposure was used in the statistical model as a continuous variable or in the quintile category. As published previously [

9], study centers, body-mass-index, gout, arm fracture, rheumatism, generalized OA, injury and inflammatory disorders of hand, elbow or shoulder joints have been considered as potential confounders in the exposure-response-analyses. To evaluate the relevance of a confounder in exposure-response estimation, stepwise backwards analyses were calculated. If a potential confounder did not change the effect estimates (odds ratio (OR)) of vibration exposure by at least 10%, this confounder was not considered in the final model of the analyses. At the end study centers, generalized OA, injury and inflammatory disorders of hand, elbow or shoulder joints were considered as relevant confounders in the final model of the analyses. The threshold for statistical significance was set to p<0.05. As all analyses are explorative, no adjustment for multiple testing has been made.

3. Results

As previously published [

9], a total of 823 male participants were recruited for this study. The average age was about 52 (range: 22-84) years. No difference between cases and controls regarding the body-mass-index (BMI) could be shown (p=0.941). However, joint injuries and musculoskeletal co-morbidities (such as gout, inflammatory disorders of the upper extremities, knee OA, hip OA, spinal OA, and generalized OA) were significantly more common among the cases than those among the controls (s.

Table 1).

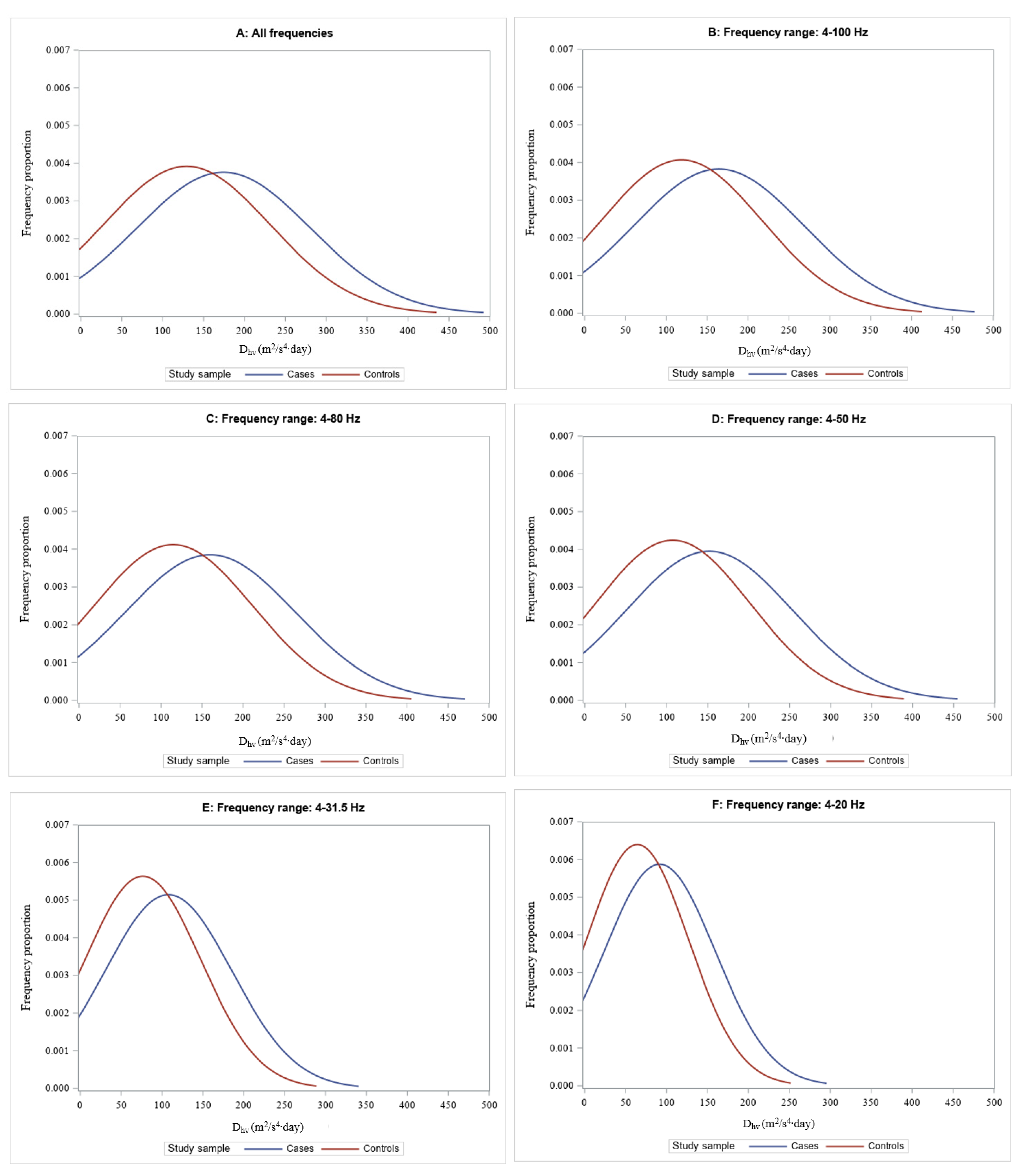

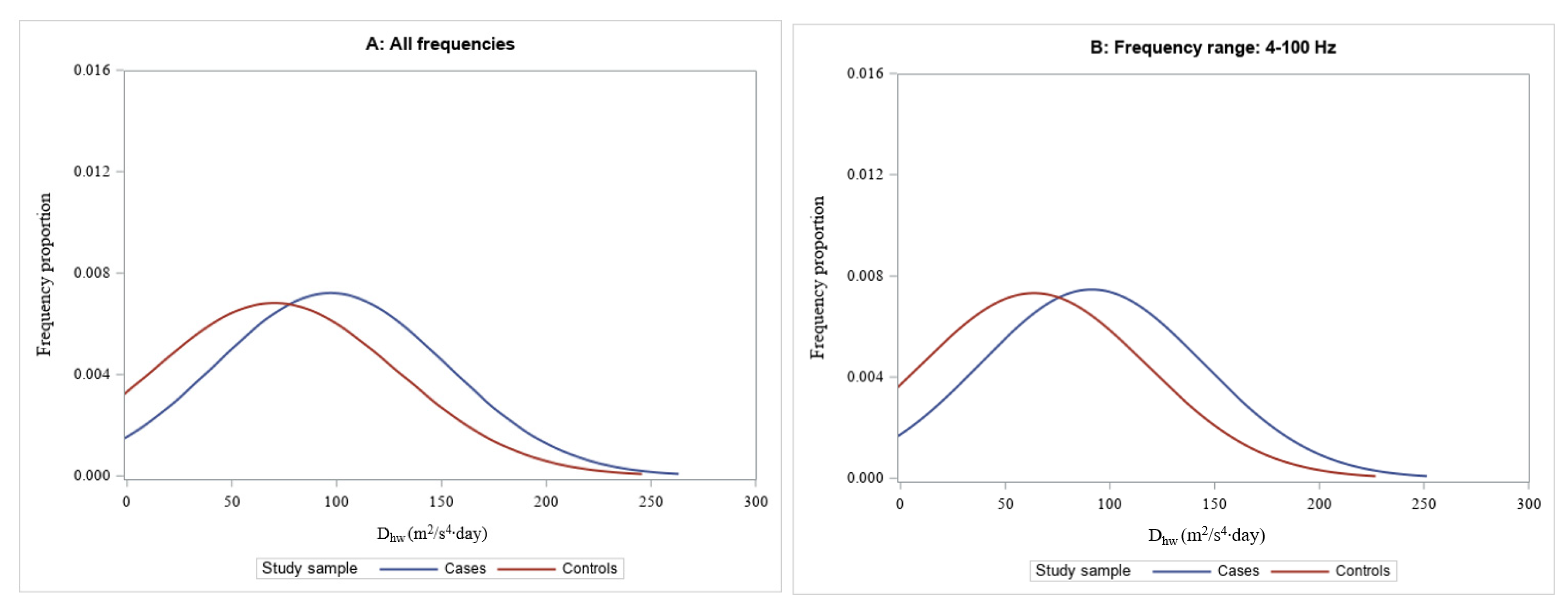

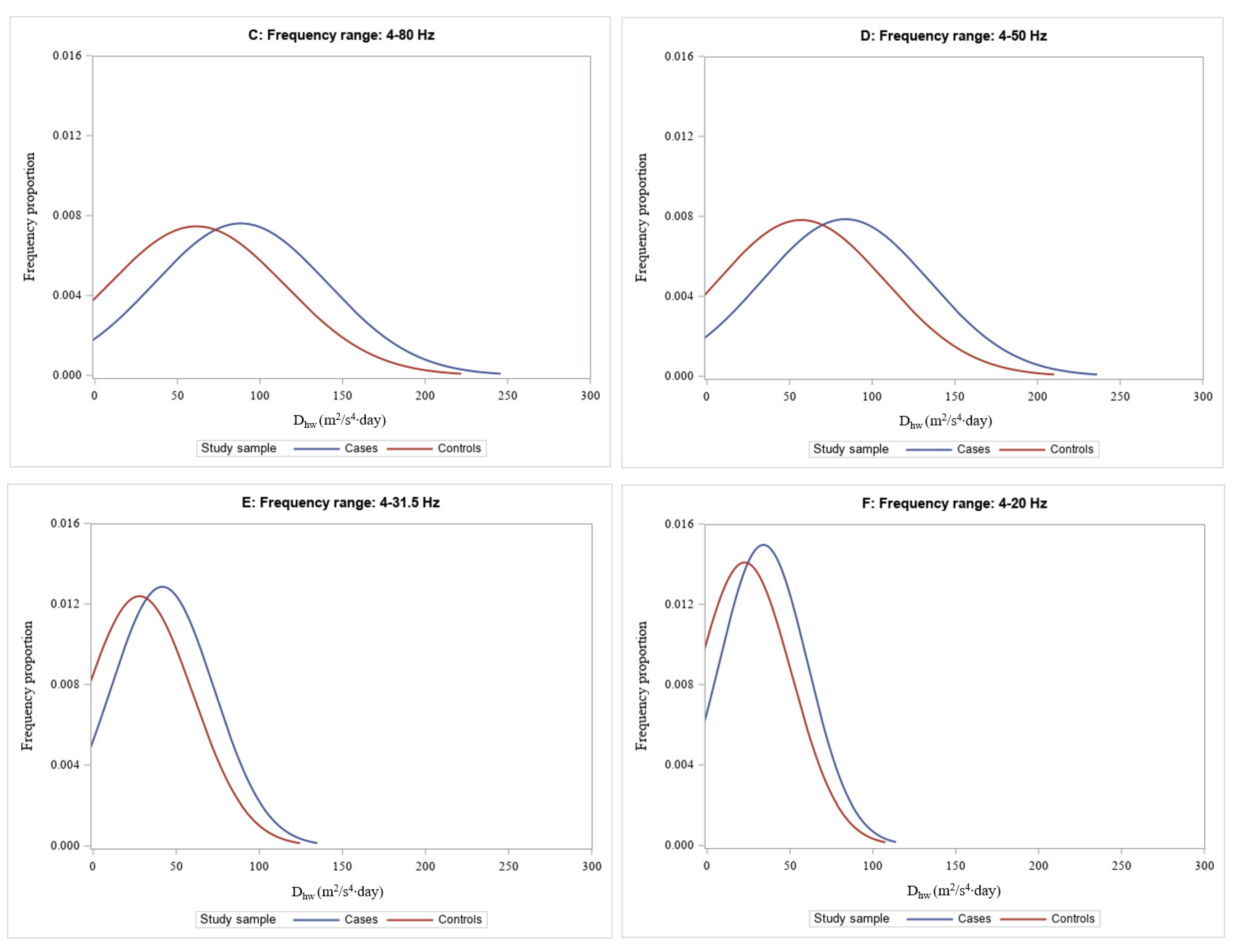

The frequency-range-specific long-term cumulative hand-arm vibration and the corresponding distribution of exposure doses are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1-2, respectively. As eight individuals (three cases and five controls) had missing frequency-range-specific exposure values, they were excluded from this analysis, leaving 815 individuals for the final analyses of this study. In general, the median values of the long-term cumulative vibration exposure doses are about 2-3 times higher in the cases than in the controls. These differences are more pronounced in the low frequency range (frequency < 50 Hz), especially for D

hw values.

The frequency-range-specific dose-response relationships between long-term vibration exposure doses (D

hv and D

hw) and musculoskeletal disorders according to occupational disease No. 2103 are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4 for

Dhv and

Dhw values, respectively. After adjusting for relevant cofounders (study center, generalized osteoarthritis, injury and inflammatory disorders of the hand, elbow, or should joints), regression analyses showed consistent and statistically significant dose-response relationships between cumulative hand-arm vibration exposure and the risk of musculoskeletal disorders. The effect estimates (ORs) of vibration exposure increase with increasing frequency ranges and are the highest for D

hv values in the frequency range of 4-80 Hz and for D

hw values in the frequency range of 4-31.5 Hz. The dose-response relationships remain consistent and statistically significant even after additional adjustment for vibration dose at all frequencies. The effect estimates (ORs) for vibration doses above 50 Hz become even larger after adjustment for vibration doses at all frequencies. This suggests that hand-arm vibration exposure at frequencies above 50 Hz has little effect on the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limbs.

Compared to the findings given in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the effect of vibration exposure at all frequencies (4-1250 Hz) on the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limbs disappears after additional adjustment for vibration dose at different frequency ranges, especially for vibration dose within 50 Hz (s.

Table 5). This further and clearly shows that the effect of hand-arm vibration exposure on musculoskeletal disorders was mainly in the low frequency range below 50 Hz.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first clear epidemiologic evidence of a frequency-range-specific effect of hand-arm vibration exposure on the risk of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. The results of this study confirm the previous hypotheses that the effect of hand-arm vibration exposure on the risk of musculoskeletal disorders of upper limbs is more pronounced in the low frequency range ≤ 50 Hz.

This is an industry-base case-control-study. The strengths and limitations of the study design have been discussed previously [

9]. Briefly, Vibration-induced musculoskeletal disorders have a long and gradual course of development and are less cause specific. This makes a longitudinal epidemiologic study extremely time-consuming and expensive. Therefore, an industry-based case-control study provides a good alternative to the conventional cohort study. Since only newly reported cases (within one year) were included in this study, it should be considered as an incidence study. In comparison to a population-based design, in the chosen industry-based design a high proportion of study participants are exposed to high levels of vibration exposure. Therefore, this design increases not only the statistical power for the initial purpose of this study (compared to a population-based design for the same sample size), but also provides relevant evidence in quantifying exposure-response relationships for work-related and vibration-induced musculoskeletal disorders.

In this study, the controls were selected as a random sample of all types of compensable occupational injuries. Compensable occupational injuries are injuries that lead to at least three days absence from work. There is no indication that occupational injuries in all parts of body are associated with hand-arm-vibration exposure. We even found that there is no significant association between injury of the upper limbs and hand-arm-vibration exposure doses among the controls in this study (comparison between persons with and without upper limb injury: p=0.1543 in Wilcoxon two-sample test). Therefore, the sampling strategy for controls in this study (random sample of occupational injuries) is unlikely to bias the distribution of hand-arm-vibration exposure when compared to the initial baseline population. The controls selected reflect the vibration exposure for a random sample of the initial baseline population.

Like all published occupational epidemiological studies, this study has some limitations. One limitation could be that all cases in this study were suspected (by local physicians) of having legal occupational disease No. 2103. This at least means that all cases have had vibration exposure in their work history. Many of them may even have had long years of employment with vibration exposure, although the magnitude of exposure level could not be estimated by the local physicians. To avoid a systemic bias, we only recruited controls who had been exposed to hand-arm vibration at work in the past. Our previous analyses demonstrated that there is no difference between the cases and the controls regarding employment duration and the initial vibration values of the technical power tools used [

9]. Therefore, the sampling strategy in this study is unlikely to have introduced any systemic bias in the quantification of exposure-response-relationships.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, there are some important strengths in this study. Besides the practical design and large sample size, one striking strength of this study is the exposure assessment method. Exposure assessment is the most important and difficult part of an occupational epidemiological study. Recall bias and objective assessment of historical exposure data are the common challenges in assessing historical occupational exposures. In the absence of detailed historical employment records, personal interviews have to be conducted and recall bias is usually unavoidable. In this study, the personal interviews focus mainly on the collection of relevant technical power tools used in the workplaces. As described above, the face-to-face interviews were carried out by specially trained safety engineers who have extensive knowledge of the work process and the technical power tools and materials used in these industries. This knowledge is crucial for accurately formulating target questions and assessing the plausibility of responses during the face-to-face interview. This minimizes the potential for recall bias. These engineers are also responsible for linking the technical power tools identified in the work history to the equipment-exposure-matrix. This is very important because the same power tools can have different vibration levels when used on different materials. These engineers ensure the correct assignment of the power tools used in the work history and in the exposure matrix, and thus a valid assessment of the historical vibration exposures. Furthermore, the values of hand-arm-vibration exposures were quantified in this study objectively based on an equipment-exposure-matrix. Since all vibration values in the exposure-database were determined in the field under real operating conditions in accordance with national and international standards and regulations [

10,

11], the exposure assessment method used allows for a standardized, objective, and valid quantification of both daily and long-term vibration exposure.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study provides clear evidence of a frequency-range-specific dose-response relationship between hand-arm vibration exposure and the risk of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. The effect of vibration exposure on the risk of upper limb musculoskeletal disorders is mainly concentrated in the frequency range ≤ 50 Hz. This suggests that the current ISO frequency weighting curve for quantifying hand-arm vibration exposure is reasonable and can be well used for vibration-related risk assessment, especially for musculoskeletal disorders. A differentiated assessment as proposed in the German standard VDI2057-2 is therefore not required for the retrospective risk assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and F.B.; methodology, Y.S., F.B. and U.K; validation, W.E., U.N., C.V., U.K. and N.R; formal analysis, Y.S.; investigation, W.E., U.N. and C.V.; data curation, W.E., U.N. and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, U.K, N.R. and F.B.; project administration, W.E., F.B. and Y.S.; funding acquisition, W.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Social Accident Insurance, grant number FP-297.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Youakim: S. Hand-arm vibration syndrome. BCMJ 2009, 51, 10.

- Bovenzi, M. Epidemiological evidence for new frequency weightings of hand-transmitted vibration. Ind Health 2012; 50(5) :377-387. [CrossRef]

- Matikainen, E.; Leinonen, H.; Juntunen, J.; Seppäläinen, A.M. The effect of exposure to high and low frequency hand-arm vibration on finger systolic pressure. EJAP 1987, 56, 440-443. [CrossRef]

- Krajnak, K.; Riley, D.A.; Wu, J.; McDowell, T.; Welcome, D.E.; Xu, X.S.; Dong, R.G. Frequency-dependent effects of vibration on physiological systems: experiments with animals and other human surrogates. Ind Health 2012, 50(5), 343-353. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.J. Frequency-dependence of psychophysical and physiological responses to hand-transmitted vibration. Ind Health 2012, 50(5), 354-369. [CrossRef]

- Bovenzi, M.; Lindsell, C.J.; Griffin, M.J. Acute vascular responses to the frequency of vibration transmitted to the hand. Occup Environ Med 2000, 57(6), 422-430. [CrossRef]

- Krajnak, K.; Miller, G.R.; Waugh, S. Contact area affects frequency-dependent responses to vibration in the peripheral vascular and sensorineural systems. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2018, 81(1-3), 6-19. [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M. [Effect of gripping and pressure force under vibration load, Research Report Hand-Arm Vibrations III] in German, German Social Accident Insurance, Sankt Augustin, Germany, 1992, 39-104.

- Sun, Y.; Bochmann, F.; Dohlich, J.; Eckert, W.; Ernst, B.; Freitag, C.; Nigmann, U.; Raffler, N.; Samel, C.; van den Berg, C.; Kaulbars, U. Exposure–response relationship between work-related hand–arm vibration exposure and musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremities: the German hand-arm vibration study. JOSE 2024, 30, 304-11. [CrossRef]

- VDI Standard 2057-2: Human exposure to mechanical vibrations - Hand-arm vibration. Beuth, Berlin (Match 2016).

- Mechanical vibration – measurement and evaluation of human exposure to hand-transmitted vibration. International Standard Organization; 2001. Standard No. ISO 5349-1: 2001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).