1. Introduction

In recent years, research has increasingly focused on the prevalence and assessment of vestibular dysfunction (VD) in children with hearing loss, particularly sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Many studies have reported an increased prevalence of VD in paediatric populations with SNHL, with and without cochlear implantation [

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, estimates of the prevalence of VD among these populations vary widely, ranging from 20% to 85% [

10]. Despite high prevalence rates of VD reported among paediatric populations with SNHL, relatively limited focus has been observed among infant populations.

Over the past decade, many studies have attempted to substantiate the direct causal mechanisms for VD in children with SNHL [

11,

12,

13]. It is theorized that the close embryological relationship between the cochlear and vestibular systems may contribute to this comorbidity [

7,

14], as any underlying aetiologies causing SNHL may also cause direct disturbance to the vestibular structures [

4,

15].

The vestibular system plays a crucial role in the mechanism of motor function, such as gaze and neck stability and coordination of head and neck movement relative to the body [

16]. Consequently, children with SNHL and unilateral or bilateral vestibulopathy often exhibit delays in motor and balance performance, including crawling and walking [

17]. In infants, this manifests itself as delayed gross motor development resulting from reduced ‘postural control, locomotion and gait’ [

4].

VD in infants can vary depending on the degree and configuration of SNHL, with severe-to-profound SNHL being the most associated with significant VD [

18]. This is likely due to the shared susceptibility of both the cochlear and vestibular systems to congenital, perinatal and acquired risk factors [

19].

The comorbidity of hearing loss, VD and subsequent motor function delays can adversely impact an infant’s ‘spatial orientation, self-concept and joint attention’ development [

4,

6]. Additionally, this association may indirectly and adversely impact cognition, literacy, learning skills and broader psychosocial development [

4].

Since the establishment of Universal Newborn Hearing Screening (UNHS) programmes in many countries, increasing attention has been given to the value of early detection and rehabilitation of infants with permanent childhood hearing loss [

20]. Despite the growing body of evidence regarding the association between SNHL and VD in paediatric populations, vestibular assessments are not commonplace practice for infants with confirmed SNHL and are more commonly restricted to cochlear implant candidacy assessments [

21].

However, pioneering research conducted by Martens et al.; 2020 [

18] is exploring the feasibility of conducting vestibular assessments on infants with congenital or early onset SNHL. VIS-Flanders has implemented a vestibular screening pathway whereby all 6-month-old infants with congenital or early onset SNHL undergo vestibular screening using cVEMPs. It was reported that a significant proportion of the demographic screened elicited abnormal vestibular responses, particularly those with severe-to-profound SNHL and/or other comorbidities such as ‘meningitis…syndromes…congenital CMV and cochleovestibular anomalies.’ [

18]

While early vestibular assessment in infants with SNHL could enable more personalised and ‘deficit-specific’ rehabilitation plans [

1], arguments against its widespread implementation include the role of connexin 26 gene mutations which leaves the vestibular system without anomaly, cost-effectiveness concerns and the lack of large-scale studies providing substantial evidence to support its inclusion in UNHS programmes.

Therefore, conducting a scoping review is an important first step to determine the feasibility of further studies to determine if an additional component to the neonatal hearing screening programme in Ireland is essential and needed.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review (ScR) was conducted in accordance with the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [

22] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMAScR) extension statement [

23]. Prior to commencing, clear eligibility criteria for included data sources was established by utilizing the Population, Concept and Context (PCC) framework.

The inclusion parameters were as follows:

For the purpose of this review, infants were defined as human beings aged 0-12 months of age [

24]. Any data sources combining results from infants and older paediatric age groups required both to be reported separately.

- 2.

Concept: Articles which included at least one vestibular test in evaluating vestibular function in the target population. Vestibular tests in this study were defined as any test which measures the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), vestibulo-collic reflex (VCR) or vestibulo-spinal reflex (VSR) in isolation.

- 3.

Context: Articles were required to report one or more of the following: (i) Measures of association of VD in the target population (with/without cochlear implantation) or in comparison to healthy controls or other groups of children with SNHL (with/without cochlear implantation). (ii) Types of vestibular function tests carried out on target population (with/without cochlear implantation) in isolation or in comparison with other vestibular tests. (iii) Sensitivity and specificity of vestibular test(s).

- 4.

Other: Primary data or grey literature published in the English language and sourced during the searching time period between the 01/02/23 – 22/04/23 were evaluated for inclusion.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Articles with infants with temporary or isolated conductive hearing loss. Articles conducting vestibular assessments solely on infants with (i) hearing within normal limits or (ii) infants with hearing within normal hearing limits AND medical conditions which could be risk factors for the future development of SNHL. Articles using animal or non-human models. Position, or opinion papers which do not correlate or are outside the parameters of the study objectives.

An initial preliminary search of google scholar was conducted to provide an overview of the size and scope of available literature on the subject. JBI recommends the use of at least two databases for initial searching while establishing a complete search string, thus preliminary searches of PubMed and Embase were conducted [

22]. All relevant papers were assessed to establish appropriate text words, keywords, MeSH and index terms. Once the completed search string had been established, a comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, Wiley and Taylor & Francis. All articles were categorically logged and assessed for inclusion eligibility. Bibliographies of included sources were screened for any additionally relevant articles. Comprehensive searching of all databases was conducted from 01.02.23 – 07.02.23 and was updated on the 21.04.23. All included sources required access to full text and published in the English language. The data charting process began by separately assessing all included articles and presenting key information relating to the review objectives. Extraction tables were utilized to systematically map and collate all relevant information across all included articles. The objectives of the review were analysed prior to designing appropriate extraction tables for charting all relevant data. Critical appraisal of all articles included in the review was conducted where applicable using critical appraisal forms formulated by JBI [

25]. Critical appraisal of included articles was completed to systematically assess the overall quality and risk of bias across the included articles. The handling and summarisation of charted data collated all results from the included articles. As each article reported results differently, data was summarised in a manner which reflects the most appropriate method of data synthesis. Synthesis of results followed the order of the objectives stated at the start of the review.

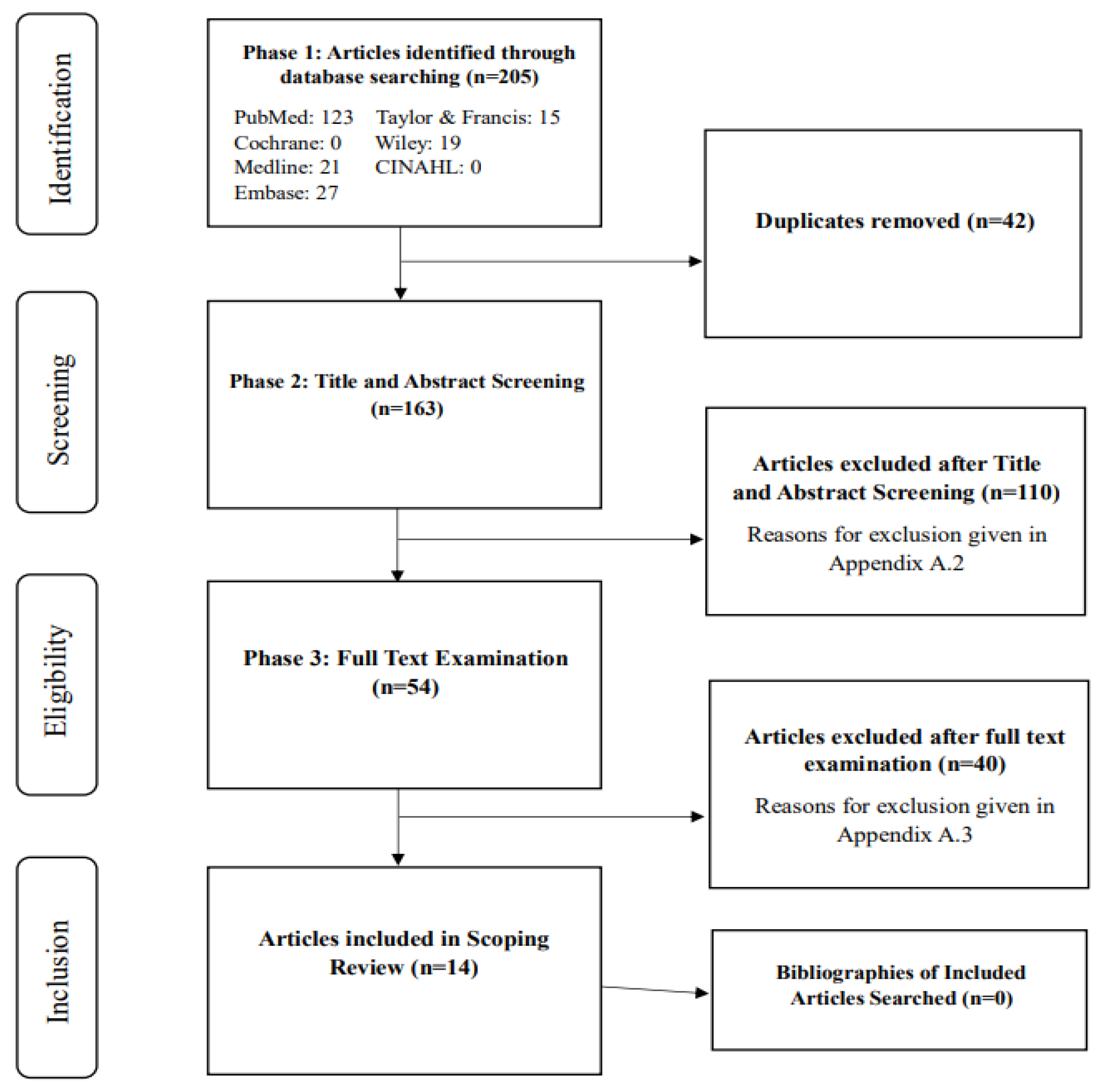

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

3. Results

This review comprised of 14 articles, including six prospective cohorts (two with specified longitudinal follow up), one cross-sectional, four case controls, two case studies and one feasibility study [

4,

18,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. A wide geographical variation was observed between the included articles ranging from Europe to Asia to North America and were published between 2005 and 2023. The majority of articles were of European origin [

4,

18,

26,

27,

28,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Most articles were conducted within hospital settings, with some using medical registries to recruit the sample population. Sample sizes varied widely, with more recently published articles generally consisting of larger sample sizes. Most studies reported age-matched controls, with a few consisting of older children or adults as comparator groups. The age range of study participants ranged from two to twelve months. The quality of the included articles were assessed using JBI CASP tools, with the majority of articles deemed as having a low to moderate risk of bias. Bias was not assessed in the feasibility study.

3.1. Characteristics of SNHL and Diagnosis:

The articles primarily reported the aetiology of SNHL as ‘congenital’ and/or ‘early onset’, with some articles focusing on specific target aetiology such as Usher syndrome Type 1, congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV), connexin 26 mutations, rubella and autosomal recessive hereditary nonsyndromic deafness. Diagnostic approaches for SNHL varied across the articles, with several using otoscopy, tympanometry and TEOAEs or DPOAEs. All articles reported the use of some form of auditory brainstem responses (ABR) assessment. Click-evoked ABR was the most reported method used, with two articles using automated ABR screening. Few articles detailed the frequencies tested during ABR assessments. Most articles reported the laterality and degree of SNHL, with degrees ranging from mild to profound. Several articles reported the proportion of participants with cochlear implantation at the time of vestibular assessment, although some articles did not report on this for subjects with severe-profound SNHL.

3.2. Vestibular Assessments and Sensitivity & Specificity Measures:

The timing of vestibular assessments varied across articles, with the youngest infants assessed at three months and others at six to twelve months. The most common vestibular test was cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (cVEMPs). Two articles conducted video head impulse testing (vHIT) on infants aged six to twelve months. Another article reported the use of calorics and cVEMP in combination on infants aged three months. A modified rotatory chair assessment was utilised on infants aged six to twelve months across three included articles and was determined as the least commonly used test. Testing protocols and normative cut-off values varied across articles, with only four articles reporting sensitivity and specificity values.

3.3. Measures of Association Between Vestibular Dysfunction and Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Infants

Most articles reported increased prevalence rates of VD in infants with congenital or early onset SNHL, with few articles reporting prevalence values separately for laterality and degree of SNHL. Six articles reported the specific types of VD observed among the sample population. The feasibility study primarily reported success rates of vestibular assessment in the specified target population.

4. Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to preliminarily assess the size and scope of available evidence regarding vestibular assessment on infants with congenital or early onset SNHL (with or without cochlear implantation) under twelve months of age.

The primary objectives of this review were to: to 1. Identify the prevalence of VD infants with congenital or early onset SNHL, 2. Identify which vestibular assessment tests/protocols are conducted on this population, 3. Report sensitivity and specificity values for identified vestibular assessment tests/protocols.

Given that paediatric vestibular assessment is rarely performed outside the realms of cochlear implant candidacy, few articles have focused on the infant population. This scarcity of literature justified the need for a scoping review to map the available evidence on this subject area. This review included mainly observational studies, as they were deemed the most appropriate in providing robust evidence for the research question.

The primary purpose of conducting vestibular assessments on infants is to differentiate between normal and abnormal vestibular function, while accounting for the developmental and maturation stage of the infant. Four vestibular function tests were identified across included articles: cVEMPs, vHIT, calorics and rotational chair testing. cVEMPs were observed as the most commonly observed assessment tool in the target population across the included articles. Martens et al. (2023) [

37] reported a 90% success rate for cVEMPs in six-month-olds compared to 70% for vHIT and 72.9% for the rotatory chair. This agreed with Verrecchia et al. (2019) [

32] who reported cVEMPs to be highly reproducible and feasible in infants as young as 2.3 months. Zagólski O (2007) [

33] reported similar results among his cohort of eighteen three-month-old infants, stating that this form of assessment was feasible in this age group although issues relating to cooperation could impact clinicians’ ability to obtain reliable and reproducible results. These reports closely correlate with studies conducted on older children, indicating cVEMPs are both feasible and child friendly.

Other vestibular assessments, such as ‘minimized rotational chair’ was deemed easy to perform and was favoured by Teschner et al (2008) [

31]. Similar findings were reported in older children by Maes et al. (2014) [

2]. Caloric testing in infants was reported to be more invasive and presented more limitations than cVEMPs, whereby reduced responses could be misinterpreted as bilateral vestibular hypofunction [

34,

35]. Other issues relating to correct irrigation due to smaller ear canal size were reported as a concern potentially leading to high levels of interindividual result variability [

34,

35]. Dhont et al. (2022) [

27] found vHIT to be sensitive in detecting dysfunction in six-to-twelve-month-olds, similarly reported in older paediatric populations with more pronounced VD.

The age at which vestibular assessments were conducted varied widely across the studies. Shen et al. (2022) [

29] reported that vestibular organ maturation at three months allowed for response rates equivalent to adults when using bone-conducted cVEMPs. However, Martens et al. (2023) [

37] recommended conducting assessments at six months old to ensure increased cooperation and reduce confounding factors related to maturation development. However, Sheykholesami et al (2005) [

30] stated that accurate and reproducible results could be obtained from 2.3-month-old infants, although longer latencies in P13 and N23 were observed due to immature maturation.

Significant variations in sensitivity and specificity were reported across the vestibular tests, indicating that these tests may be complementary to each other rather than fixed substitutions. Several articles did not report these metrics, highlighting a gap in the literature. A previous systematic review conducted by Verbecque et al (2017) [

10] on older children (>3y) reported cVEMP sensitivity between 48% and 100%, with a specificity range of 30% to 100%. This compared to a previous study conducted on an adult population with SNHL which yielded a sensitivity of 91.4% and specificity of 95.8% (Fife et al.; 2017). In comparison, Zagólski O (2007) [

33] reported a cVEMP sensitivity and specificity of 100% when utilizing calorics in comparison. Dhont et al (2022) reported a vHIT 30% sensitivity and 91% specificity in infants with congenital SNHL attributed to CMV, reported similarly by Duarte et al (2022) [

21]. Further, in infants with cCMV and early onset SNHL, sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 91% was reported. Martens et al (2023) [

37] refrained from presenting such measures, stating that validity of such measures could not be substantiated due to conflicts between results relating to other utilized vestibular tests.

Higher prevalence rates of VD in infants with congenital or early onset SNHL was observed across all included articles [

4,

18,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The evidence included in this review reported that infants with severe-profound unilateral or bilateral SNHL were at a higher risk of VD compared to infants with mild-moderate SNHL. Often this risk was exacerbated by the presence of additional medical conditions rendering the infant more susceptible to presenting with SNHL. This finding correlates with articles conducted on older populations which reported higher prevalence of VD in those with greater degrees of SNHL. The observed high prevalent rates of VD in infants with congenital or early onset SNHL across included articles indicates that vestibular assessments potentially should be conducted on this population in an accurate, reliable, and reproducible modality. However, the review noted several limitations, including potential biases due to small sample sizes, the lack of randomization, and the risk of confounding factors across the included studies. The review also highlighted the need for larger-scale studies with more rigorous methodologies to provide more definitive conclusions.

Overall, the results of this scoping review illustrate promising results both in feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of vestibular assessment in the target population. The review emphasizes the need for further research, particularly large-scale, prospective cohort studies, to establish standardised clinical criteria and normative values. The limited number of available literature highlights the necessity for increased robust evidence to support policy changes and the implementation of targeted interventions.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, this scoping review provided a sound presentation of the size and scope of available evidential literature of vestibular assessment in infants with SNHL. The results of this review signals for the potential value of conducting targeted vestibular assessment using cVEMPs in infants with congenital or early onset SNHL within the UNHS. As implementing such an intervention would be costly and time-consuming on already overburden healthcare systems, it is recommended that such targeted vestibular assessments could be initially conducted on infants with greater degrees of hearing loss, such as the infants with unilateral/bilateral moderate-profound SNHL. Further targeted assessments should also be conducted on infants with specific risk factors for the comorbidity such as but not limited to; meningitis, cCMV, rubella and those exposed to ototoxic medications. Vestibular assessment fulfils a potentially crucial role in the identification and management opportunities for infants with SNHL who have been reported to be at a higher risk of VD [

7]. Substantiating this link alongside with developing the most appropriate method of assessing this population has the potential to provide valuable insights into more individualised rehabilitation processes. Through earlier detection of VD in infants with SNHL, clinicians can provide targeted intervention strategies in optimizing the developmental outcomes for this population. Additionally, vestibular assessment can help identify particular aetiologies of sensorineural hearing loss [

17]. Both hearing loss and VD are linked to specific prenatal abnormalities and genetic diseases [

38]. Clinicians can acquire more diagnostic data by assessing the vestibular system, which may help in identifying the underlying cause of the hearing loss. For genetic counselling, predicting developmental outcomes, and directing medical and surgical procedures, this information is essential. Martens et al (2019) [

4] have designed a potential pathway for introducing vestibular screening seamlessly into the UNHS programme, which could be potentially implemented across the globe. cVEMPs is reported as a suitable screener for VD in this review. Although, due to its limitations in which part of the system it assesses, other suitable and child-friendly assessments should be considered as potentially complementary tests to minimize any overlooked VD. Importantly, it is recommended that bone conducted cVEMPs should be utilized to overcome potential middle ear pathology such as middle ear effusion, which is highly prevalent in infants and young children [

39]. Sensitivity and specificity values in this population vary across studies with reports ranging from 20-85% [

10]. With increasing evidential literature modifying assessment protocols, clearer sensitivity and specificity values can be developed. Although, promising results have been presented in this review, further research is required to substantiate previous findings. The small number of articles available to review on the research question demonstrates the overall lack of meaningful evidence in support of curating national policy changes or intervention implementation. Further research which rectifies the limitations identified in previous research would add to the body of evidence in enabling more focused national policies and practice recommendations. A national study conducted on a large-scale generalisable population through a prospective cohort design would provide increased observational study power. Although, more uniform clinical criteria and normative cut off values relating to vestibular assessment must be substantiated a priori to guide meaningful research to better inform the research question. Overall, the results of this scoping review illustrate promising results both in feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of VD in the target population. With an increased number of evidential literatures both on smaller and large-scale populations with proper implementation design and resource application, clinicians would be enabled to guide the way in providing early detection opportunities for all infants with congenital or early onset SNHL.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Angeli, S. Value of Vestibular Testing in Young Children With Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2003, 129, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, L.; De Kegel, A.; Van Waelvelde, H.; Dhooge, I. Rotatory and Collic Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential Testing in Normal-Hearing and HearingImpaired Children. Ear and Hearing 2014, 35, e21–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyewumi, M.; Wolter, N.E.; Heon, E.; Gordon, K.A.; Papsin, B.C.; Cushing, S.L. Using Balance Function to Screen for Vestibular Impairment in Children With 55 Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Cochlear Implants. Otology & Neurotology 2016, 37, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, S.; Dhooge, I.; Dhondt, C.; Leyssens, L.; Sucaet, M.; Vanaudenaerde, S.; Rombaut, L.; Maes, L. Vestibular Infant Screening – Flanders: The implementation of a standard vestibular screening protocol for hearing-impaired children in Flanders. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2019, 120, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadsbøll, E.; Erbs, A.W.; Hougaard, D.D. (2022). Prevalence of abnormal vestibular responses in children with sensorineural hearing loss. European Archives of OtoRhino-Laryngology. [CrossRef]

- Wiener-Vacher, S.R. Vestibular disorders in children. International Journal of Audiology 2008, 47, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, S.L.; Papsin, B.C.; Rutka, J.A.; James, A.L.; Gordon, K.A. Evidence of Vestibular and Balance Dysfunction in Children With Profound Sensorineural Hearing Loss Using Cochlear Implants. The Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, T.G.T.; Venosa, A.R.; Sampaio, A.L.L. Association between Hearing Loss and Vestibular Disorders: A Review of the Interference of Hearing in the Balance. International Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery 2015, 04, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Heet, H.; Guggenheim, D.S.; Lim, M.; Garg, B.; Bao, M.; Smith, S.L.; Garrison, D.; Raynor, E.M.; Lee, J.W.; Wrigley, J.; Riska, K.M. A Systematic 56 Review on the Association Between Vestibular Dysfunction and Balance Performance in Children With Hearing Loss. Ear & Hearing 2021, 43, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbecque, E.; Marijnissen, T.; De Belder, N.; Van Rompaey, V.; Boudewyns, A.; Van de Heyning, P.; Vereeck, L.; Hallemans, A. Vestibular (dys)function in children with sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. International Journal of Audiology 2017, 56, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraders, M.; Oostrik, J.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Strom, T.M.; van Wijk, E.; Kunst, H.P.M.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; Cremers, C.W.R.J.; Admiraal, R.J.C.; Kremer, H. Mutations in PTPRQ Are a Cause of Autosomal-Recessive Nonsyndromic Hearing Impairment DFNB84 and Associated with Vestibular Dysfunction. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2010, 86, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioacchini, F.M.; Alicandri-Ciufelli, M.; Kaleci, S.; Magliulo, G.; Re, M. Prevalence and diagnosis of vestibular disorders in children: A review. International 51 Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2014, 78, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, K.; Usami, S. Vestibular nerve deficiency and vestibular function in children with unilateral hearing loss caused by cochlear nerve deficiency. Acta OtoLaryngologica 2021, 141, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuniga, M.G.; Dinkes, R.E.; Davalos-Bichara, M.; Carey, J.P.; Schubert, M.C.; King, W.M.; Walston, J.; Agrawal, Y. Association Between Hearing Loss and Saccular Dysfunction in Older Individuals. Otology & Neurotology 2012, 33, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudoux, A.; Vitry, S.; El-Amraoui, A. Vestibular Deficits in Deafness: Clinical Presentation, Animal Modeling, and Treatment Solutions. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Luxon, L.M. Development and assessment of the vestibular system. International Journal of Audiology 2008, 47, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janky, K.L.; Thomas, M.L.A.; High, R.R.; Schmid, K.K.; Ogun, O.A. Predictive Factors for Vestibular Loss in Children With Hearing Loss. American Journal of Audiology 2018, 27, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, S.; Dhooge, I.; Dhondt, C.; Vanaudenaerde, S.; Sucaet, M.; Rombaut, L.; Boudewyns, A.; Desloovere, C.; Janssens de Varebeke, S.; Vinck, A.-S.; Vanspauwen, R.; Verschueren, D.; Foulon, I.; Staelens, C.; Van den Broeck, K.; De Valck, C.; Deggouj, N.; Lemkens, N.; Haverbeke, L.; De Bock, M. Vestibular Infant Screening (VIS)–Flanders: results after 1.5 years of vestibular screening in hearing-impaired children. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 21011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaga, K. Vestibular compensation in infants and children with congenital and acquired vestibular loss in both ears. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 1999, 49, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.; Cordeiro De Souza Pereira, E.; Kerlyne, K.; Torres, C.; Monforte, A.; Ii, M.; Lima, A.; Ledesma, L. (2020). Evaluation of the Newborn Hearing Program. SciELO. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, Cabral, & Britto. Vestibular assessment in children aged zero to twelve years: an integrative review. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Elsevier, 2022; 88. [CrossRef]

- JBI. (2022). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. JBI Global Wiki. Available online: https://jbi-globalwiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687770/11.3+The+scoping+review+and+summar y+of+the+evidence.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E.A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M.G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S. 57 PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. (2019). Infants (0-1 years). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/infants.html.

- Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu P-F. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Dhondt, C.; Maes, L.; Rombaut, L.; Martens, S.; Vanaudenaerde, S.; Van Hoecke, H.; De Leenheer, E. and Dhooge, I. Vestibular Function in Children With a Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: 3 Years of Follow-Up. Ear & Hearing 2021, 42, pp.76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondt, C.; Maes, L.; Martens, S.; Vanaudenaerde, S.; Rombaut, L.; Sucaet, M.; Keymeulen, A.; Van Hoecke, H.; De Leenheer, E. and Dhooge, I. Predicting Early Vestibular and Motor Function in Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. The Laryngoscope 2022, 133, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, L.; De Kegel, A.; Van Waelvelde, H.; De Leenheer, E.; Van Hoecke, H.; Goderis, J. and Dhooge, I. Comparison of the Motor Performance and Vestibular Function in Infants with a Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection or a Connexin 26 Mutation. Ear and Hearing 2017, 38, e49–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; He, K.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Kaga, K.; Duan, M.; Yang, J. and Jin, Y. Cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in 3-month-old infants: Comparative characteristics and feasibility for infant vestibular screening. Frontiers in Neurology, 2022; 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykholesami, Kaga, Megerian, C.A. and Arnold, J.O. Vestibular-Evoked Myogenic Potentials in Infancy and Early Childhood. Laryngoscope 2005, 115, 1440–1444. [CrossRef]

- Teschner, Neuburger, Gockeln, Lenarz and Lesinski-Schiedat ‘Minimized rotational vestibular testing’ as a screening procedure detecting vestibular areflexy in deaf children: screening cochlear implant candidates for Usher syndrome Type I. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2008, 265, 759–763. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrecchia, L.; Galle Barrett, K. and Karltorp, E. The feasibility, validity and reliability of a child friendly vestibular assessment in infants and children candidates to cochlear implant. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2019, 135, 110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagólski, O. Vestibular System in Infants With Hereditary Nonsyndromic Deafness. Otology & Neurotology 2007, 28, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagólski, O. Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials and caloric stimulation in infants with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 2008, 122, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagólski, O. Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials and caloric tests in infants with congenital rubella. B-ENT 2009, 5, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, S.; Dhooge, I.; Dhondt, C.; Vanaudenaerde, S.; Sucaet, M.; Van Hoecke, H.; De Leenheer, E.; Rombaut, L.; Boudewyns, A.; Desloovere, C.; Vinck, A.-S.; de Varebeke, S.J.; Verschueren, D.; Verstreken, M.; Foulon, I.; Staelens, C.; De Valck, C.; Calcoen, R.; Lemkens, N. Three Years of Vestibular Infant Screening in Infants With Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Pediatrics 2022, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, S.; Maes, L.; Dhondt, C.; Vanaudenaerde, S.; Sucaet, M.; De Leenheer, E.; Van Hoecke, H.; Van Hecke, R.; Rombaut, L. and Dhooge, I. (2023). Vestibular Infant Screening–Flanders: What is the Most Appropriate Vestibular Screening Tool in Hearing-Impaired Children? Ear & Hearing, Publish Ahead of Print. [CrossRef]

- Frejo, L.; Giegling, I.; Teggi, R.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Rujescu, D. Genetics of vestibular disorders: pathophysiological insights. Journal of Neurology 2016, 263, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2015, August 18). Ear Infections in Children. NIDCD. Available online: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/ear-infectionschildren.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).