1. Introduction

In the recent past, investments in renewable energy (RE) resources have been increasing due to the increasing energy supply and the risk of depletion of fossil fuels and their environmental impacts. In addition to energy sources such as wind, geothermal, biomass and hydroelectricity, which are among the sustainable energy sources, the use of solar energy is increasing rapidly on a global scale with its high accessibility and easy installation advantages [

1,

2,

3]. In this regard, photovoltaic (PV) panel systems stand out as renewable, environmentally friendly and clean energy sources that convert light from the sun directly into electrical energy [

3,

4]. PV systems provide a powerful alternative to fossil fuels by facilitating our access to renewable energy and make a significant contribution to a sustainable energy future [

5,

6]. The widespread use of PV systems worldwide has had a multiplier effect on the increase in scientific research in this field. The main aim of all these researches is to obtain the highest efficiency from the PV module. Therefore, it is critical to understand the electrical dynamics behaviour of PV systems and to optimise them with an accurate mathematical model to obtain maximum power [

7,

8]. In this respect, it is aimed to estimate the optimal parameters by simulating an electrical model [

7].

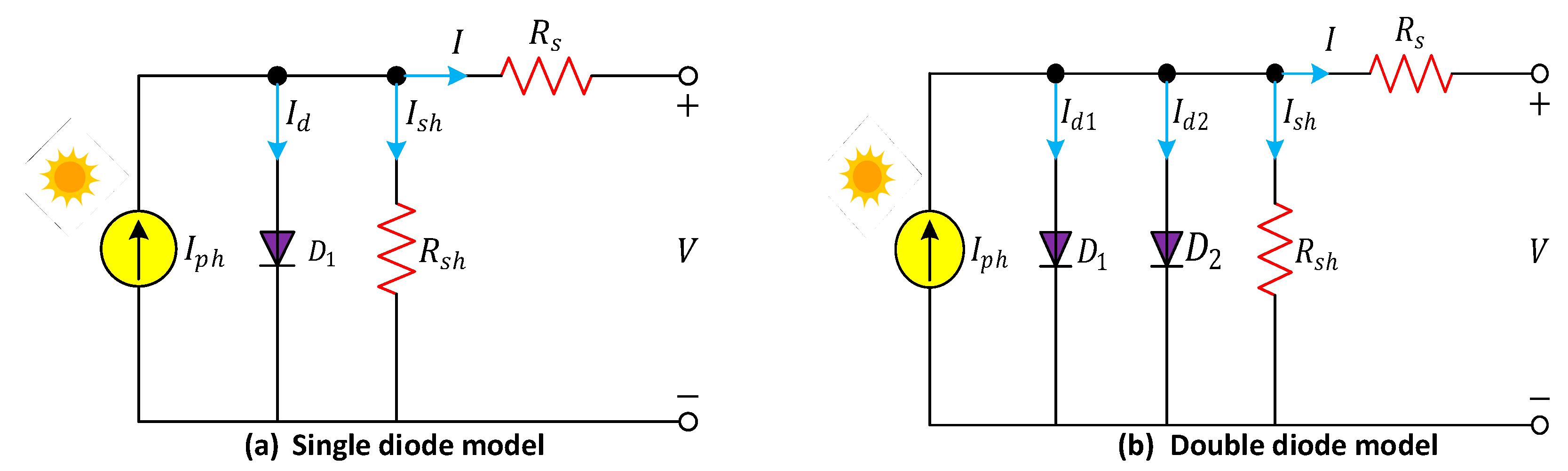

In the literature, single diode model (SDM) and double diode model (DDM) are widely used electrical models [

9]. SDM is the simplest and most practical model of PV cell. This model has 5 unknown parameters, namely photogeneration current (

), shunt resistance (

), series resistance (

), diode saturation current (

) and ideality factor (

). The DDM, obtained by connecting a second diode in parallel, is the electrical model used for more complex and precise calculations with 7 unknown parameters [

10]. In this context, the main objective of the calculation of unknown parameters is to design a PV cell model that will provide high accuracy and maximum power efficiency [

7,

10,

11]. One of the main challenges is to solve the nonlinear equation provided by these designed models and to determine the unknown parameters. Several methods including analytical, deterministic and meta-heuristic (MH) have been proposed in the literature to improve the efficiency of PV systems [

12]. Although analytical methods give fast results, they cause deviations in measured and calculated parameter values due to their dependence on initial values. Deterministic methods such as Newton-Raphson (NR), Gauss-Seidel have disadvantages such as high computation times [

13,

14]. Despite the disadvantages of analytical and deterministic approaches, MH optimisation methods have come to the fore [

15].

In recent years, MH optimisation algorithms have been frequently used to solve many engineering problems. Optimisation algorithms in PV cells provide the most efficient and optimal results by analysing the interrelationships of the basic parameters of the cell in depth. This enables PV systems to be used more effectively by increasing energy efficiency [

16,

17,

18]. There are some MH optimisation algorithms proposed in the literature such as atomic orbital search algorithm [

19], bald eagle search (BES) [

20], harris hawks optimization (HHO) [

21], improved jaya optimization algorithm (IJAYA) [

22], bacterial foraging algorithm (BFA) [

23], tunicate swarm algorithm (TSA) [

24], grey wolf optimization (GWO) [

25], differential evolution (DE) [

26], artificial bee swarm optimization (ABSO) [

27], honey badger algorithm (HBA) [

28], whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [

29], farmland fertility optimizer (FFO) [

30], ranking teaching learning based optimization (RTLBO) [

31], wind driven optimization (WDO) [

32], generalized oppositional teaching learning-based optimization (GOTLBO) [

33], weighted mean of vectors algorithm (INFO) [

34] etc. These algorithms provide solutions for parameter estimation in PV cells. However, current MH algorithms need to be investigated in more detail. In this context, it is important to introduce new optimisation algorithms for solar PV parameter extraction [

35]. In this study, a novel frilled lizard optimisation (FLO) algorithm is proposed as an efficient method for estimating PV model parameters.

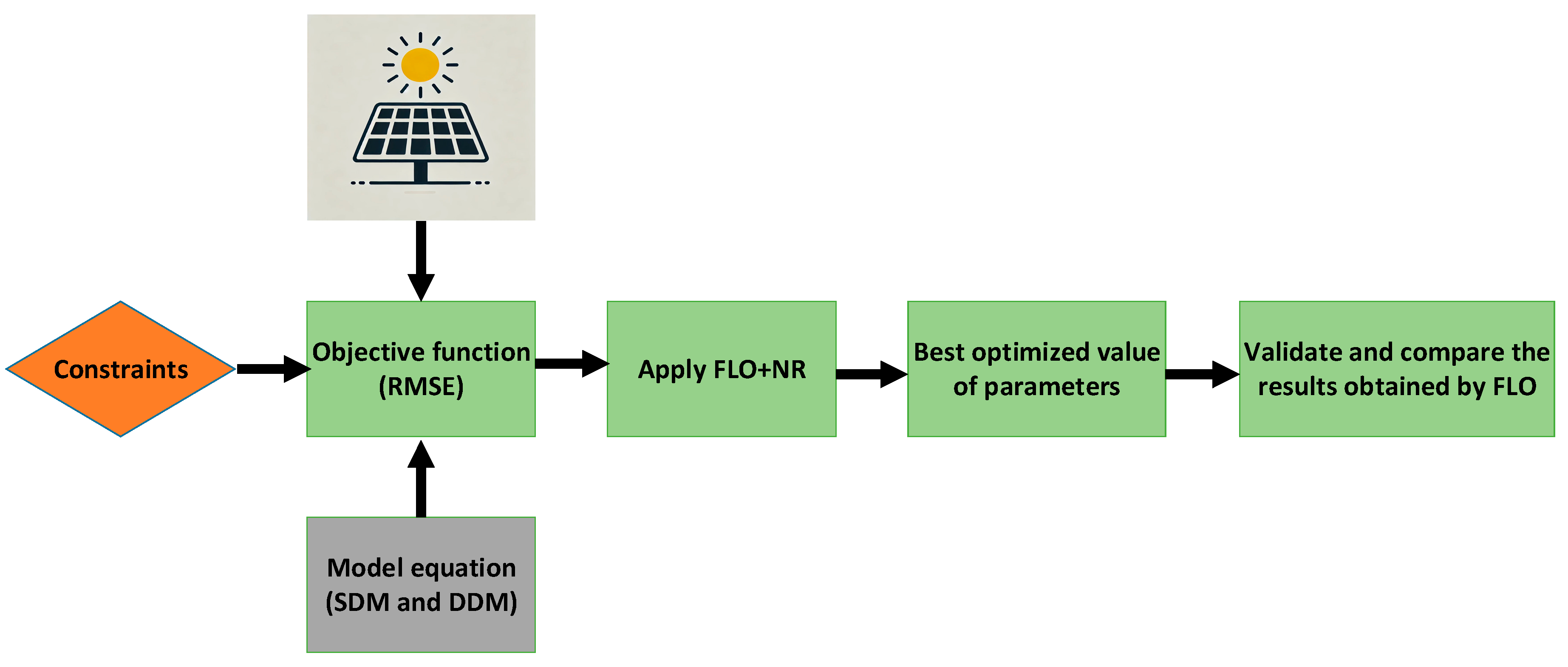

The FLO algorithm is inspired by the hunting and defence behaviour of the frilled lizard in nature and is devised to be used in solving complex problems. This optimisation algorithm is widely used in engineering, finance, energy management and health sciences [

36,

37,

38]. The FLO algorithm has a population-based approach and works with an initially randomly generated solution set. The objective function, which evaluates how good the solution is to achieve the target value, is critical for optimisation algorithms [

39,

40,

41]. In the optimisation of PV system parameters, the statistical term root mean square error (RMSE) is often used as the objective function. In this process, the decrease of the RMSE value in each iteration is an indication of improved performance. Since the relationship between current and voltage is nonlinear, the Newton-Raphson (N-R) numerical method is integrated to determine the solution points of the equations in the objective function [

41,

42,

43]. In this paper, a novel FLO algorithm is integrated with the N-R numerical method and used for the first time in the literature to solve the problem of estimating unknown parameters in PV cells.

This paper contributes to the literature both theoretically and practically by developing a new methodology for the optimisation of PV cells. The first use of the FLO algorithm in this field fills an important gap in the literature and breaks new ground to inspire future studies. In this context, the study offers an innovative perspective both theoretically and practically. The main contributions of this study can be listed as follows:

A novel and efficient FLO algorithm is used to estimate the unknown parameters in PV systems.

In particular, the N-R numerical method is integrated to analyse the nonlinear equation of RMSE more efficiently.

The performance of the proposed FLO algorithm is also calculated in detail with error metrics such as IAE, RE, MAE.

A comprehensive comparison of the obtained results with various algorithms found in the literature has been made.

In the following

Section 2, the mathematical formulation of the electrical models to be analysed and the objective function are introduced.

Section 3 further details the proposed FLO algorithm. In

Section 4, the experimental results obtained are evaluated and discussed. The last

Section 5 is organised in such a way that a conclusion is presented.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a novel FLO algorithm is proposed to estimate the unknown parameters in PV cells and N-R numerical method is integrated to improve the efficiency of the algorithm. In order to reveal the potential of the algorithm, analyses were performed on single and dual diode electrical models using R.T.C Fance, STM6-40/36 and Photowatt-PWP-201 real module data. In addition, IAE, RE and MAE error metrics were calculated. These error metric results, the lowest RMSE value obtained compared to other compared algorithms, consistent statistical metrics (such as max, min, mean, std, var) and highly accurate matched MPP point, suggest that the proposed FLO algorithm offers a powerful alternative that increases efficiency with precise parameter estimation, especially in PV cells. Furthermore, it is shown that the proposed FLO algorithm provides a strong agreement and parallelism between the I-V and P-V characteristics of the measured and estimated parameter values. As a result, FLO has a wide application potential in the design and performance analyses of solar energy systems. Especially, it is an effective tool for efficiency analyses of photovoltaic modules, simulation of panel performance and improving accuracy in system design. In addition, FLO's low error rates and results compatible with physical parameters support its use in the industrial field. This algorithm is expected to be useful in industrial applications to provide optimum design and efficiency in solar energy systems. The following topics are planned to be focussed in future studies.

The FLO algorithm will make significant contributions to the development of PV cell models in a more dynamic way through hybrid approaches created by integration with different algorithms.

Experimental studies will be carried out with module data including different operating conditions in order to verify the practical effectiveness of the FLO algorithm.

Studies will be carried out on the applicability of FLO algorithm to the solution of optimisation problems in various fields.

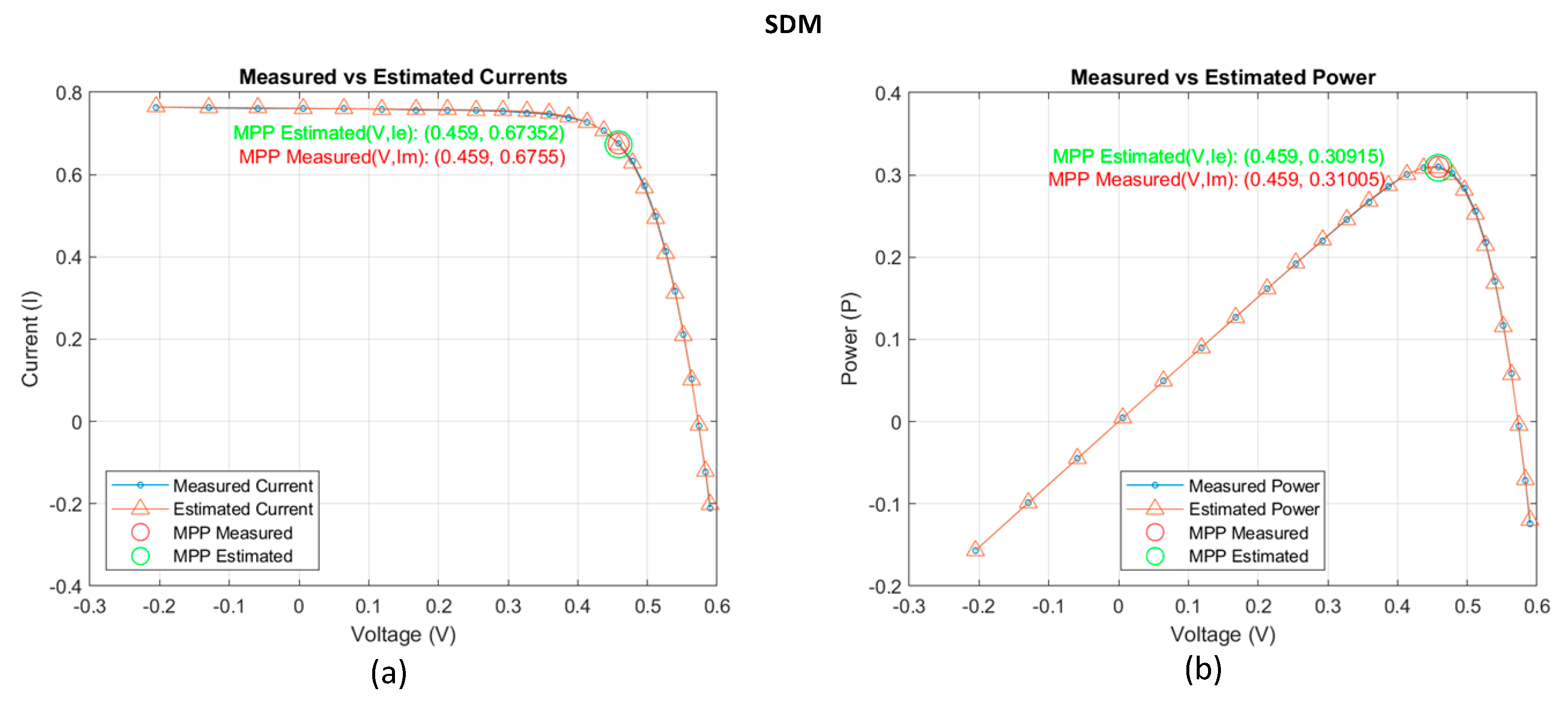

Figure 4.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for R.T.C France model (a) I-V of SDM, (b) P-V of SDM.

Figure 4.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for R.T.C France model (a) I-V of SDM, (b) P-V of SDM.

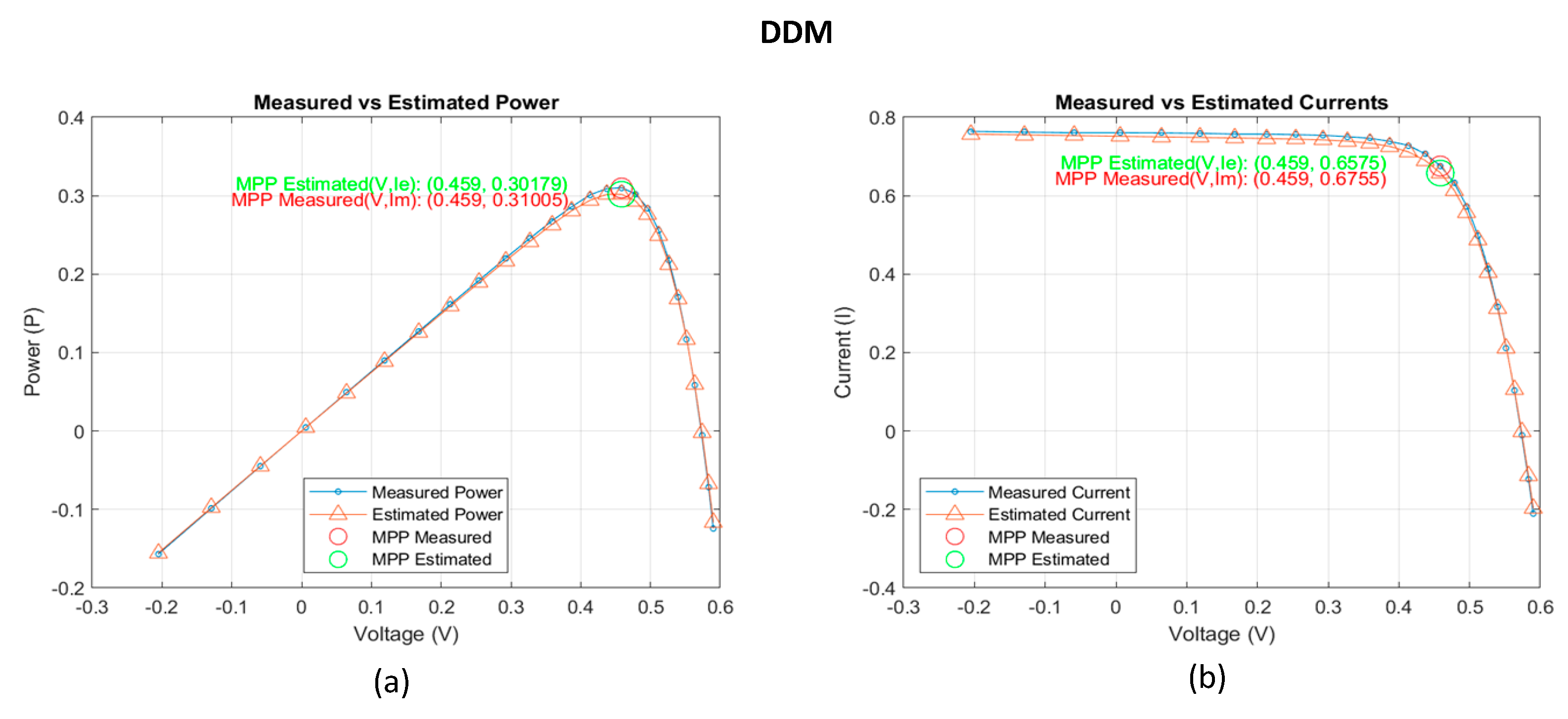

Figure 5.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for R.T.C France model (a) I-V of DDM, (b) P-V of DDM.

Figure 5.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for R.T.C France model (a) I-V of DDM, (b) P-V of DDM.

Figure 6.

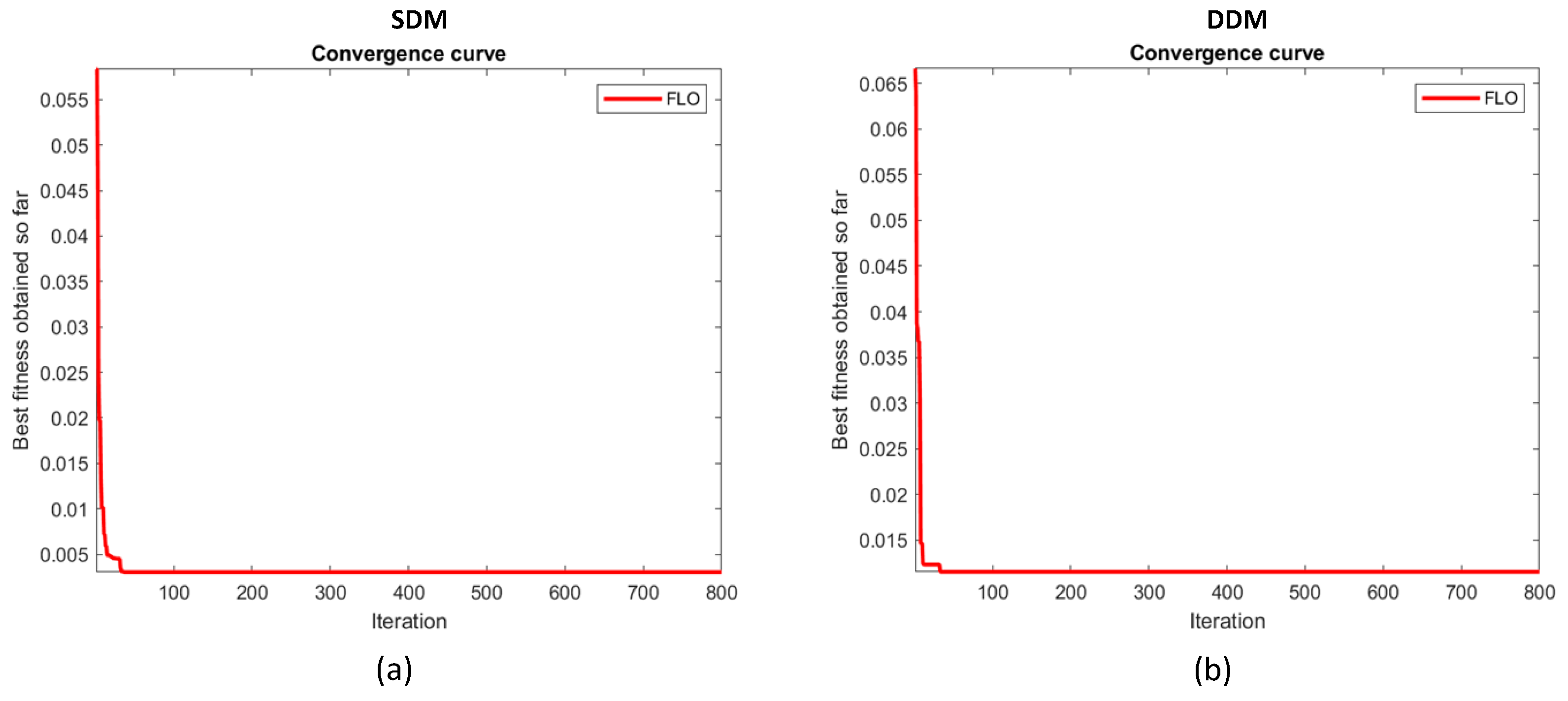

Convergence graph of proposed FLO algorithm for R.T.C France model: (a) SDM, (b) DDM.

Figure 6.

Convergence graph of proposed FLO algorithm for R.T.C France model: (a) SDM, (b) DDM.

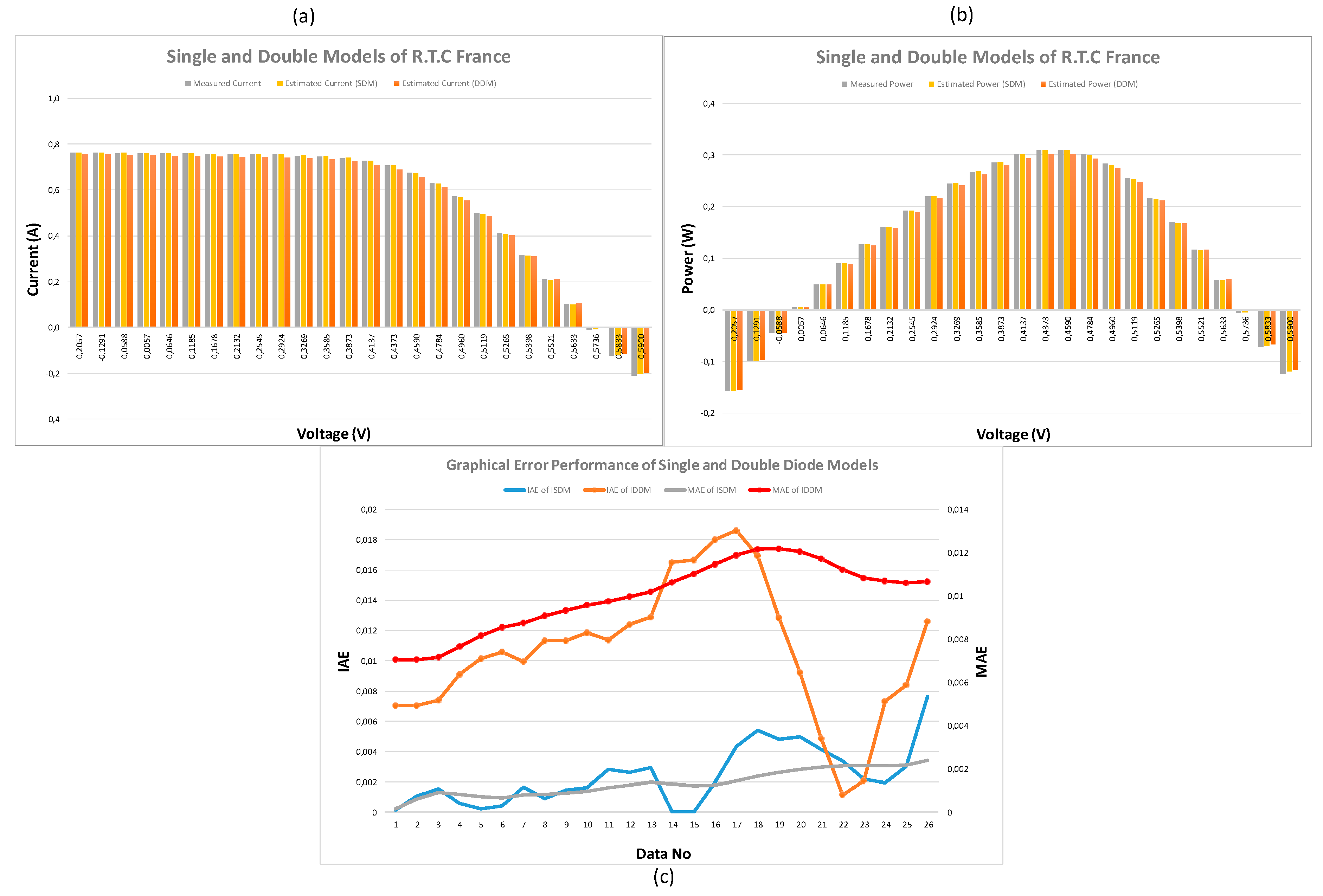

Figure 7.

Performance Comparison of Single and Double Diode Models Using FLO algorithm (a)I-V, (b)P-V and (c) Error Metrics for Each Data Point.

Figure 7.

Performance Comparison of Single and Double Diode Models Using FLO algorithm (a)I-V, (b)P-V and (c) Error Metrics for Each Data Point.

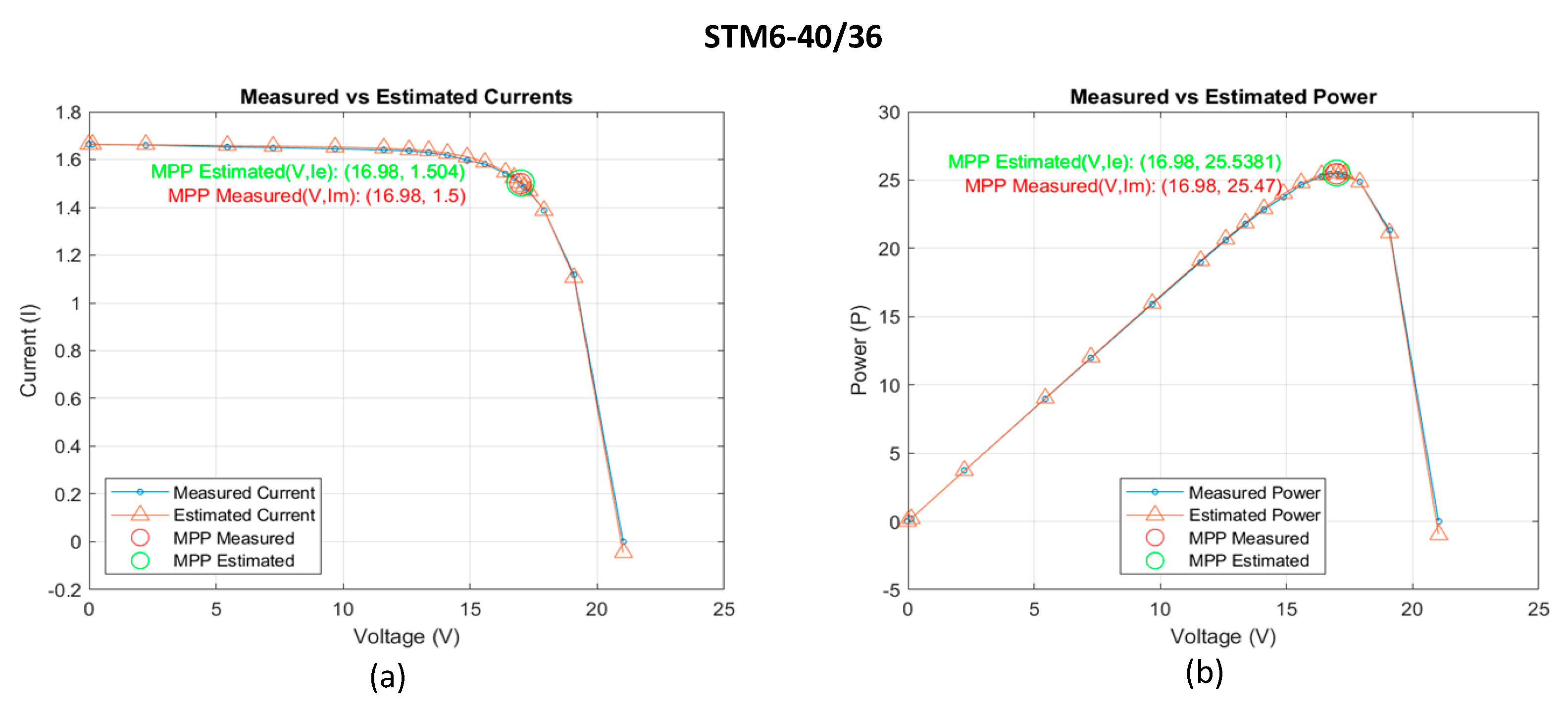

Figure 8.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for STM6-40/36 model (a) I-V curve. (b) P-V curve.

Figure 8.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for STM6-40/36 model (a) I-V curve. (b) P-V curve.

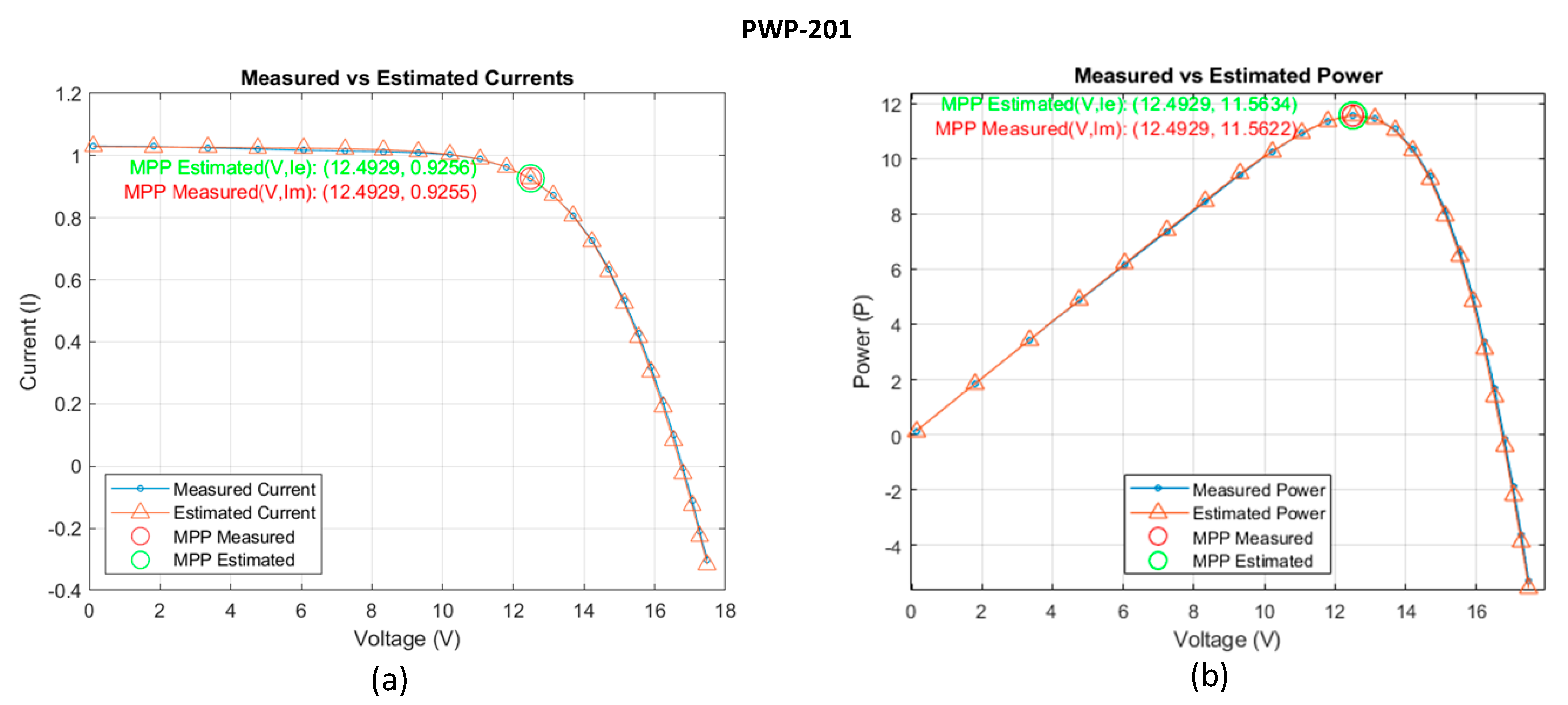

Figure 9.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for Photowatt PWP-201 model (a) I-V curve. (b) P-V curve.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the measured and the estimated data obtained by FLO algorithm for Photowatt PWP-201 model (a) I-V curve. (b) P-V curve.

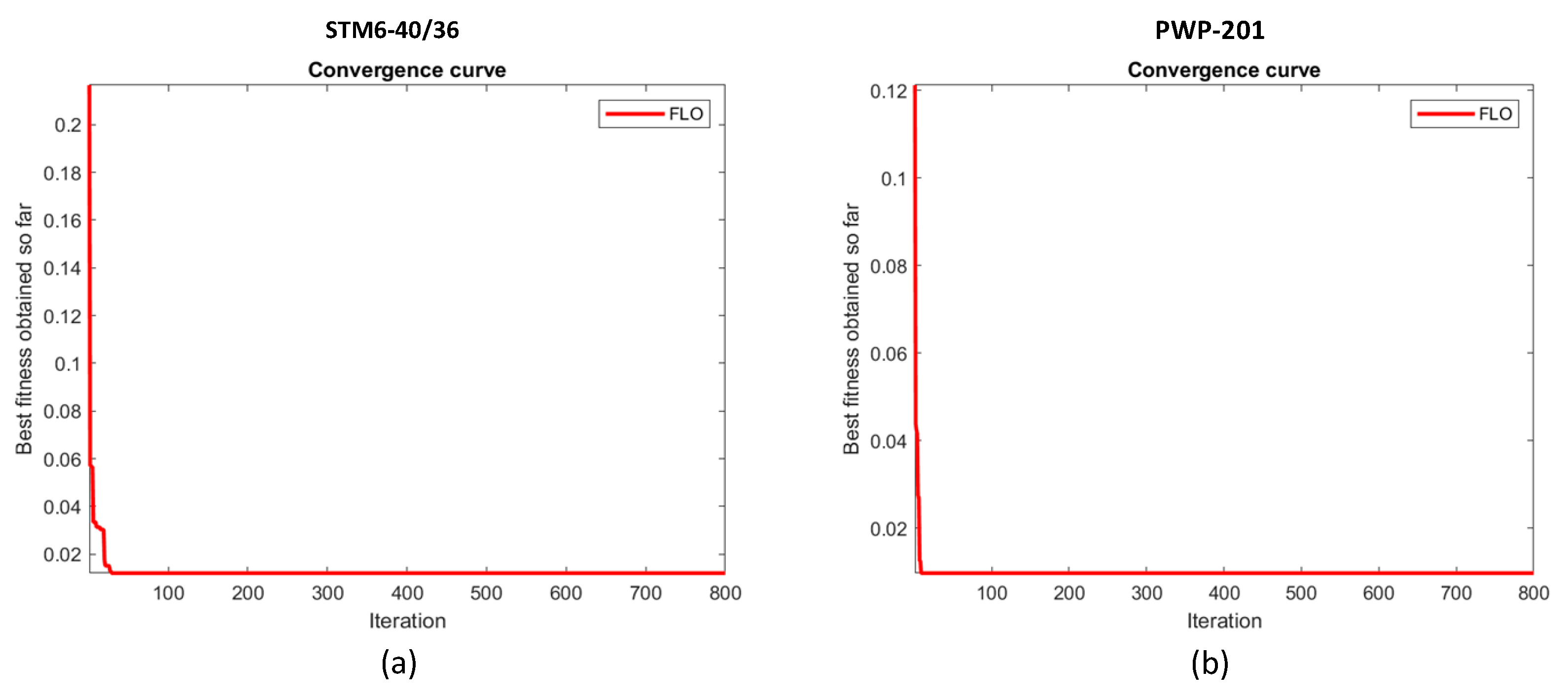

Figure 10.

Convergence graph of proposed FLO algorithm for: (a) STM6-40/36. (b) Photowatt PWP-201.

Figure 10.

Convergence graph of proposed FLO algorithm for: (a) STM6-40/36. (b) Photowatt PWP-201.

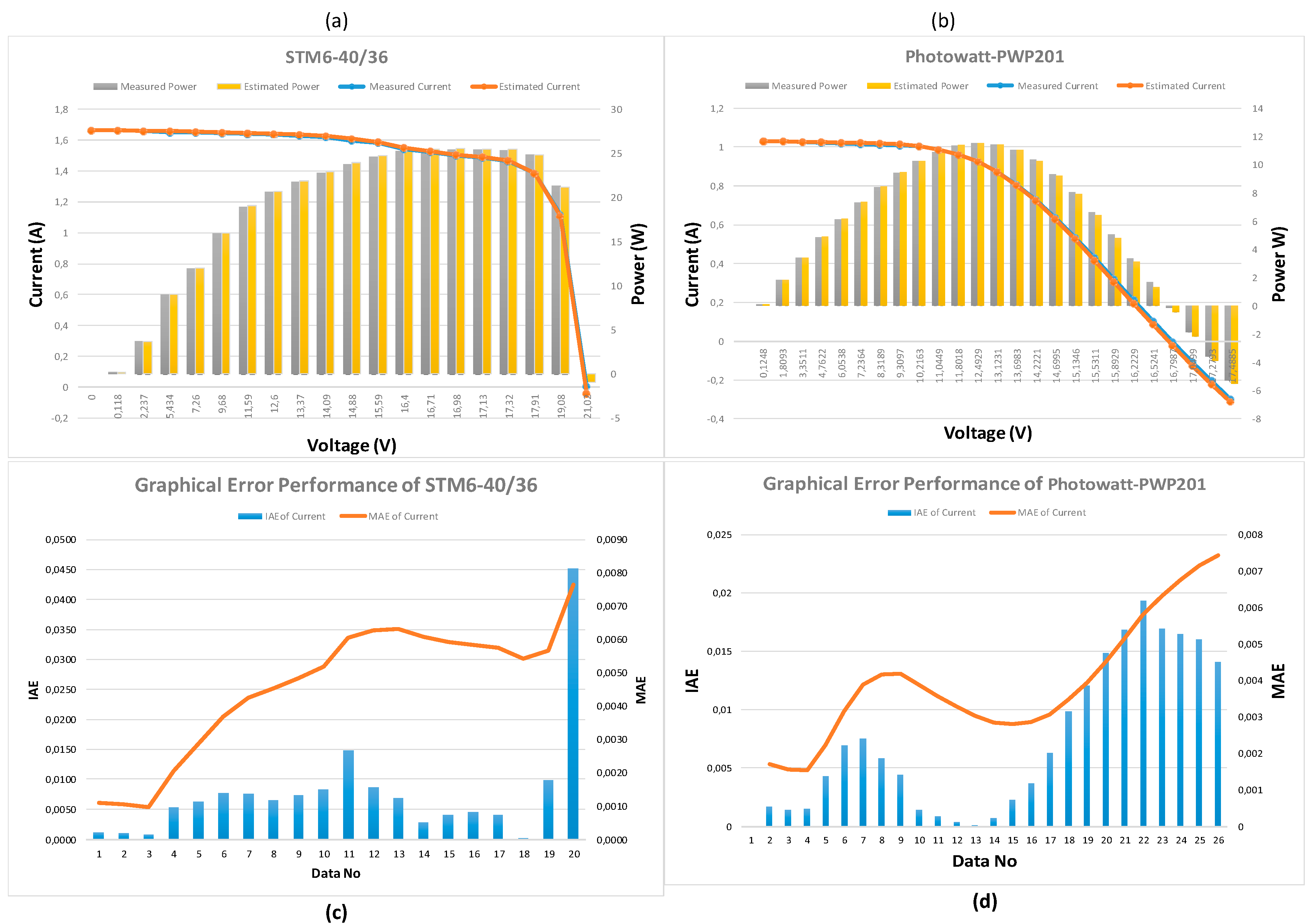

Figure 11.

Performance Comparison I-V, P-V and Error Metrics for Each Data Point; (a), (c) STM6-40/36 and (b), (d) Photowatt-PWP201.

Figure 11.

Performance Comparison I-V, P-V and Error Metrics for Each Data Point; (a), (c) STM6-40/36 and (b), (d) Photowatt-PWP201.

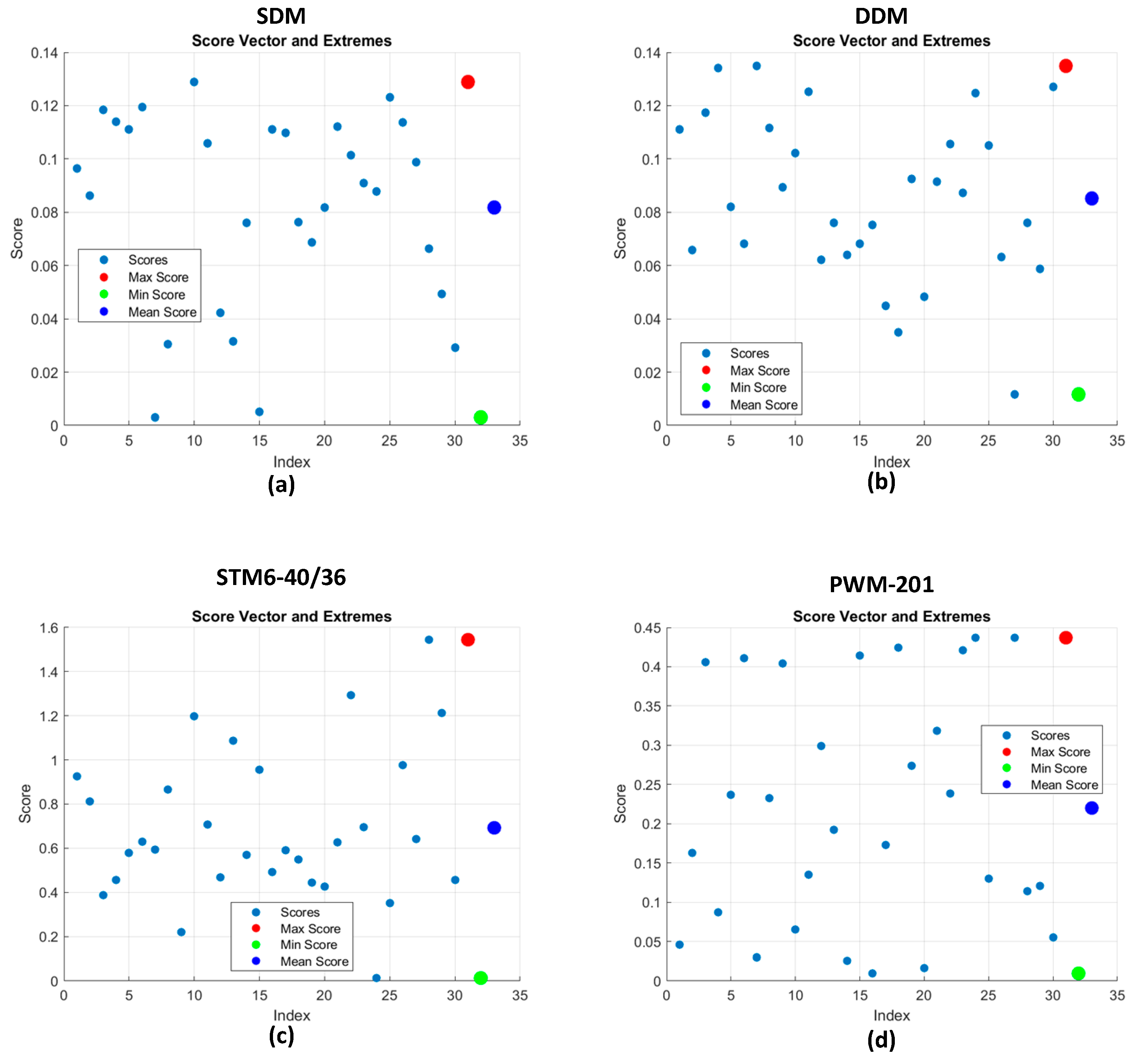

Figure 12.

Statistical scores (RMSE) of all runs (30) by FLO algorithm: (a) SDM. (b) DDM. (c) STM6-40/36 and (d) Photowatt PWP-201.

Figure 12.

Statistical scores (RMSE) of all runs (30) by FLO algorithm: (a) SDM. (b) DDM. (c) STM6-40/36 and (d) Photowatt PWP-201.

Table 3.

Comparison of result obtained from the FLO with other optimization techniques in the literature for DDM.

Table 3.

Comparison of result obtained from the FLO with other optimization techniques in the literature for DDM.

| Algorithm |

(A) |

(μA) |

(Ω) |

(Ω) |

|

(μA) |

|

RMSE |

| FLO (Proposed) |

0.752239 |

0.592485 |

0.0342579 |

38.0587 |

1.55789 |

0.646782 |

1.9019 |

0.011538 |

| PSO [57] |

0.7623 |

0.4767 |

0.0325 |

43.1034 |

1.5172 |

0.01 |

2 |

0.0166 |

| GA [52] |

0.7608 |

0.0001 |

0.0364 |

53.7185 |

1.3355 |

0.0001 |

1.481 |

0.36040 |

| SA [53] |

0.7623 |

0.4767 |

0.0345 |

43.1034 |

1.5172 |

0.01 |

2 |

0.01664 |

| PS [54] |

0.7602 |

0.9889 |

0.032 |

81.3008 |

1.6 |

0.0001 |

1.192 |

0.01518 |

| WOA [55] |

0.7658 |

2.9957E-07 |

0.0493 |

59.0196 |

1.4795 |

3.9438E-07 |

1.9201 |

0.0154 |

| OBSCA [56] |

0.794380 |

0.528673 |

0.03468 |

23.9696 |

1.527530 |

0.04440 |

2 |

0.024067 |

| BOA [56] |

0.78077 |

0.89987 |

0.03875 |

34.5559 |

1.47604 |

0.29385 |

1.99100 |

0.013564 |

Table 4.

Statistical error tests for SDM of R.T.C. France.

Table 4.

Statistical error tests for SDM of R.T.C. France.

| No |

Measured Data |

Estimation Data |

IAE |

RE |

MAE |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

-0.2057 |

0.7640 |

-0.1572 |

0.7642 |

-0.1572 |

0.00016 |

0.00004 |

0.0209 |

-0.0255 |

0.00016 |

| 2 |

-0.1291 |

0.7620 |

-0.0984 |

0.7631 |

-0.0985 |

0.00105 |

0.00014 |

0.1378 |

-0.1382 |

0.00060 |

| 3 |

-0.0588 |

0.7605 |

-0.0447 |

0.7620 |

-0.0448 |

0.00153 |

0.00009 |

0.2012 |

-0.2013 |

0.00091 |

| 4 |

0.0057 |

0.7605 |

0.0043 |

0.7611 |

0.0043 |

0.00059 |

0.00000 |

0.0776 |

0.0784 |

0.00083 |

| 5 |

0.0646 |

0.7600 |

0.0491 |

0.7602 |

0.0491 |

0.00023 |

0.00002 |

0.0303 |

0.0306 |

0.00071 |

| 6 |

0.1185 |

0.7590 |

0.0899 |

0.7594 |

0.0900 |

0.00044 |

0.00005 |

0.0580 |

0.0589 |

0.00067 |

| 7 |

0.1678 |

0.7570 |

0.1270 |

0.7587 |

0.1273 |

0.00168 |

0.00029 |

0.2219 |

0.2283 |

0.00081 |

| 8 |

0.2132 |

0.7570 |

0.1614 |

0.7579 |

0.1616 |

0.00091 |

0.00020 |

0.1202 |

0.1239 |

0.00082 |

| 9 |

0.2545 |

0.7555 |

0.1923 |

0.7570 |

0.1927 |

0.00148 |

0.00038 |

0.1959 |

0.1976 |

0.00090 |

| 10 |

0.2924 |

0.7540 |

0.2205 |

0.7556 |

0.2210 |

0.00163 |

0.00048 |

0.2162 |

0.2177 |

0.00097 |

| 11 |

0.3269 |

0.7505 |

0.2453 |

0.7533 |

0.2463 |

0.00283 |

0.00092 |

0.3771 |

0.3750 |

0.00114 |

| 12 |

0.3585 |

0.7465 |

0.2676 |

0.7491 |

0.2686 |

0.00261 |

0.00094 |

0.3496 |

0.3512 |

0.00126 |

| 13 |

0.3873 |

0.7385 |

0.2860 |

0.7415 |

0.2872 |

0.00295 |

0.00114 |

0.3995 |

0.3986 |

0.00139 |

| 14 |

0.4137 |

0.7280 |

0.3012 |

0.7280 |

0.3012 |

0.00002 |

0.00001 |

0.0027 |

0.0033 |

0.00129 |

| 15 |

0.4373 |

0.7065 |

0.3090 |

0.7065 |

0.3090 |

0.00003 |

0.00001 |

0.0042 |

0.0032 |

0.00121 |

| 16 |

0.4590 |

0.6755 |

0.3101 |

0.6735 |

0.3092 |

0.00198 |

0.00090 |

0.2931 |

0.2903 |

0.00126 |

| 17 |

0.4784 |

0.6320 |

0.3024 |

0.6277 |

0.3003 |

0.00432 |

0.00207 |

0.6835 |

0.6846 |

0.00144 |

| 18 |

0.4960 |

0.5730 |

0.2842 |

0.5676 |

0.2815 |

0.00540 |

0.00268 |

0.9424 |

0.9430 |

0.00166 |

| 19 |

0.5119 |

0.4990 |

0.2554 |

0.4942 |

0.2530 |

0.00481 |

0.00246 |

0.9639 |

0.9630 |

0.00182 |

| 20 |

0.5265 |

0.4130 |

0.2174 |

0.4080 |

0.2148 |

0.00498 |

0.00262 |

1.2058 |

1.2049 |

0.00198 |

| 21 |

0.5398 |

0.3165 |

0.1709 |

0.3124 |

0.1686 |

0.00415 |

0.00224 |

1.3112 |

1.3111 |

0.00208 |

| 22 |

0.5521 |

0.2120 |

0.1171 |

0.2086 |

0.1152 |

0.00338 |

0.00187 |

1.5943 |

1.5976 |

0.00214 |

| 23 |

0.5633 |

0.1035 |

0.0583 |

0.1013 |

0.0571 |

0.00220 |

0.00124 |

2.1256 |

2.1303 |

0.00215 |

| 24 |

0.5736 |

-0.0100 |

-0.0057 |

-0.0081 |

-0.0046 |

0.00194 |

0.00111 |

-19.4080 |

-19.4090 |

0.00214 |

| 25 |

0.5833 |

-0.1230 |

-0.0717 |

-0.1200 |

-0.0700 |

0.00300 |

0.00171 |

-2.4390 |

-2.3764 |

0.00217 |

| 26 |

0.5900 |

-0.2100 |

-0.1239 |

-0.2024 |

-0.1194 |

0.00764 |

0.00451 |

-3.6381 |

-3.6400 |

0.00238 |

| Sum of IAE |

|

|

|

|

|

0.06194 |

0.02812 |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Statistical error tests for DDM of R.T.C. France.

Table 5.

Statistical error tests for DDM of R.T.C. France.

| No |

Measured Data |

Estimation Data |

IAE |

RE |

MAE |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

-0.2057 |

0.7640 |

-0.1572 |

0.7570 |

-0.1557 |

0.00704 |

0.00144 |

0.9215 |

-0.9163 |

0.00704 |

| 2 |

-0.1291 |

0.7620 |

-0.0984 |

0.7550 |

-0.0975 |

0.00705 |

0.00091 |

0.9252 |

-0.9250 |

0.00705 |

| 3 |

-0.0588 |

0.7605 |

-0.0447 |

0.7531 |

-0.0443 |

0.00739 |

0.00043 |

0.9717 |

-0.9705 |

0.00716 |

| 4 |

0.0057 |

0.7605 |

0.0043 |

0.7514 |

0.0043 |

0.00909 |

0.00005 |

1.1953 |

1.1950 |

0.00764 |

| 5 |

0.0646 |

0.7600 |

0.0491 |

0.7499 |

0.0484 |

0.01014 |

0.00066 |

1.3342 |

1.3341 |

0.00814 |

| 6 |

0.1185 |

0.7590 |

0.0899 |

0.7484 |

0.0887 |

0.01058 |

0.00125 |

1.3939 |

1.3931 |

0.00855 |

| 7 |

0.1678 |

0.7570 |

0.1270 |

0.7471 |

0.1254 |

0.00994 |

0.00166 |

1.3131 |

1.3069 |

0.00875 |

| 8 |

0.2132 |

0.7570 |

0.1614 |

0.7457 |

0.1590 |

0.01131 |

0.00241 |

1.4941 |

1.4933 |

0.00907 |

| 9 |

0.2545 |

0.7555 |

0.1923 |

0.7442 |

0.1894 |

0.01133 |

0.00288 |

1.4997 |

1.4979 |

0.00932 |

| 10 |

0.2924 |

0.7540 |

0.2205 |

0.7422 |

0.2170 |

0.01183 |

0.00346 |

1.5690 |

1.5694 |

0.00957 |

| 11 |

0.3269 |

0.7505 |

0.2453 |

0.7391 |

0.2416 |

0.01136 |

0.00372 |

1.5137 |

1.5163 |

0.00973 |

| 12 |

0.3585 |

0.7465 |

0.2676 |

0.7341 |

0.2632 |

0.01240 |

0.00445 |

1.6611 |

1.6628 |

0.00996 |

| 13 |

0.3873 |

0.7385 |

0.2860 |

0.7256 |

0.2810 |

0.01290 |

0.00499 |

1.7468 |

1.7446 |

0.01018 |

| 14 |

0.4137 |

0.7280 |

0.3012 |

0.7115 |

0.2944 |

0.01649 |

0.00682 |

2.2651 |

2.2645 |

0.01063 |

| 15 |

0.4373 |

0.7065 |

0.3090 |

0.6899 |

0.3017 |

0.01665 |

0.00728 |

2.3567 |

2.3564 |

0.01103 |

| 16 |

0.4590 |

0.6755 |

0.3101 |

0.6575 |

0.3018 |

0.01800 |

0.00826 |

2.6647 |

2.6641 |

0.01147 |

| 17 |

0.4784 |

0.6320 |

0.3024 |

0.6134 |

0.2934 |

0.01861 |

0.00891 |

2.9446 |

2.9469 |

0.01189 |

| 18 |

0.4960 |

0.5730 |

0.2842 |

0.5561 |

0.2758 |

0.01692 |

0.00839 |

2.9529 |

2.9520 |

0.01217 |

| 19 |

0.5119 |

0.4990 |

0.2554 |

0.4862 |

0.2489 |

0.01283 |

0.00657 |

2.5711 |

2.5720 |

0.01220 |

| 20 |

0.5265 |

0.4130 |

0.2174 |

0.4038 |

0.2126 |

0.00921 |

0.00484 |

2.2300 |

2.2259 |

0.01205 |

| 21 |

0.5398 |

0.3165 |

0.1709 |

0.3117 |

0.1682 |

0.00483 |

0.00261 |

1.5261 |

1.5277 |

0.01171 |

| 22 |

0.5521 |

0.2120 |

0.1171 |

0.2109 |

0.1164 |

0.00113 |

0.00063 |

0.5330 |

0.5382 |

0.01123 |

| 23 |

0.5633 |

0.1035 |

0.0583 |

0.1056 |

0.0595 |

0.00208 |

0.00117 |

2.0097 |

2.0085 |

0.01083 |

| 24 |

0.5736 |

-0.0100 |

-0.0057 |

-0.0027 |

-0.0016 |

0.00729 |

0.00418 |

-72.9430 |

-72.9428 |

0.01068 |

| 25 |

0.5833 |

-0.1230 |

-0.0717 |

-0.1146 |

-0.0669 |

0.00838 |

0.00489 |

-6.8130 |

-6.8171 |

0.01059 |

| 26 |

0.5900 |

-0.2100 |

-0.1239 |

-0.1974 |

-0.1165 |

0.01260 |

0.00743 |

-6.0000 |

-5.9968 |

0.01067 |

| Sum of IAE |

|

|

|

|

|

0,27738 |

0,10030 |

|

|

|

Table 6.

Comparison of result obtained from the FLO with other optimization techniques in the literature for STM6-40/36.

Table 6.

Comparison of result obtained from the FLO with other optimization techniques in the literature for STM6-40/36.

| Algorithm |

(A) |

(μA) |

(Ω) |

(Ω) |

|

RMSE |

| FLO (Proposed) |

1.664394 |

1.955187 |

0.1534515 |

950.3287 |

58.27311 |

0.012036 |

|

TAPSO [58] |

1.66180 |

12.8424 |

0.00053 |

190.1861 |

1.77407 |

0.013423 |

|

ABC [59] |

1.5 |

1.6644 |

0.1796 |

547.416 |

53.5176 |

0.19253 |

|

CIABC [59] |

1.6642 |

1.676 |

0.1584 |

562.212 |

53.9136 |

0.02518 |

|

PSO [60] |

1.64 |

0.151 |

0.28 |

200.94 |

55.82 |

0.0241 |

|

SCA [60] |

1.74 |

0.252 |

0.86 |

100.52 |

54.51 |

0.0295 |

|

WDO [61] |

0.827900 |

42.22415 |

0.312870 |

772.4239 |

28.6336 |

0.0934228 |

Table 7.

Comparison of result obtained from the FLO with other optimization techniques in the literature for Photowatt-PWP201.

Table 7.

Comparison of result obtained from the FLO with other optimization techniques in the literature for Photowatt-PWP201.

| Algorithm |

(A) |

(μA) |

(Ω) |

(Ω) |

|

RMSE |

| FLO (Proposed) |

1.0308692 |

2.5494649 |

1.2662524 |

1408.5111 |

49.181231 |

0.0097545 |

|

WOA [55] |

1.3135 |

0 |

0.0622 |

16.229 |

49.4231 |

0.2838 |

|

SCA [62] |

1.03364 |

0.118 |

0.930711 |

1268.463 |

53.72168 |

0.0117780 |

|

FA [63] |

1.0424 |

4.6816 |

1.2042 |

1204.0547 |

497875 |

0.0103 |

|

ASO [64] |

1.2145 |

1.0826 |

0.2298 |

59.6881 |

44.3904 |

0.16898 |

|

Newton [59] |

1.0318 |

3.2875 |

1.2057 |

555.5556 |

48.45 |

0.7805 |

|

WDO [61] |

0.31735 |

3.682679 |

0.978698 |

184.19173 |

8.215487 |

0.104839 |

Table 8.

Statistical error tests for SDM of STM6-40/36.

Table 8.

Statistical error tests for SDM of STM6-40/36.

| |

Measured Data |

Estimation Data |

IAE |

RE |

MAE |

| No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0 |

1.663 |

0 |

1.6641 |

0 |

0.0011 |

0.0000 |

0.0661 |

- |

0.0011 |

| 2 |

0.118 |

1.663 |

0.196234 |

1.664 |

0.196352 |

0.0010 |

0.0001 |

0.0601 |

0.0601 |

0.0010 |

| 3 |

2.237 |

1.661 |

3.71566 |

1.6618 |

3.71737 |

0.0008 |

0.0017 |

0.0482 |

0.0460 |

0.0010 |

| 4 |

5.434 |

1.653 |

8.9824 |

1.6583 |

9.01137 |

0.0053 |

0.0290 |

0.3206 |

0.3225 |

0.0020 |

| 5 |

7.26 |

1.65 |

11.979 |

1.6562 |

12.0242 |

0.0062 |

0.0452 |

0.3758 |

0.3773 |

0.0029 |

| 6 |

9.68 |

1.645 |

15.9236 |

1.6527 |

15.9981 |

0.0077 |

0.0745 |

0.4681 |

0.4679 |

0.0037 |

| 7 |

11.59 |

1.64 |

19.0076 |

1.6476 |

19.0957 |

0.0076 |

0.0881 |

0.4634 |

0.4635 |

0.0042 |

| 8 |

12.6 |

1.636 |

20.6136 |

1.6425 |

20.6957 |

0.0065 |

0.0821 |

0.3973 |

0.3983 |

0.0045 |

| 9 |

13.37 |

1.629 |

21.7797 |

1.6363 |

21.8772 |

0.0073 |

0.0975 |

0.4481 |

0.4477 |

0.0048 |

| 10 |

14.09 |

1.619 |

22.8117 |

1.6273 |

22.929 |

0.0083 |

0.1173 |

0.5127 |

0.5142 |

0.0052 |

| 11 |

14.88 |

1.597 |

23.7634 |

1.6118 |

23.9834 |

0.0148 |

0.2200 |

0.9267 |

0.9258 |

0.0061 |

| 12 |

15.59 |

1.581 |

24.6478 |

1.5896 |

24.7824 |

0.0086 |

0.1346 |

0.5440 |

0.5461 |

0.0063 |

| 13 |

16.4 |

1.542 |

25.2888 |

1.5489 |

25.4018 |

0.0069 |

0.1130 |

0.4475 |

0.4468 |

0.0063 |

| 14 |

16.71 |

1.524 |

25.466 |

1.5269 |

25.515 |

0.0029 |

0.0490 |

0.1903 |

0.1924 |

0.0061 |

| 15 |

16.98 |

1.5 |

25.47 |

1.504 |

25.5381 |

0.0040 |

0.0681 |

0.2667 |

0.2674 |

0.0059 |

| 16 |

17.13 |

1.485 |

25.4381 |

1.4895 |

25.5151 |

0.0045 |

0.0770 |

0.3030 |

0.3027 |

0.0058 |

| 17 |

17.32 |

1.465 |

25.3738 |

1.4691 |

25.4441 |

0.0041 |

0.0703 |

0.2799 |

0.2771 |

0.0057 |

| 18 |

17.91 |

1.388 |

24.8591 |

1.3878 |

24.8556 |

0.0002 |

0.0035 |

0.0144 |

0.0141 |

0.0054 |

| 19 |

19.08 |

1.118 |

21.3314 |

1.1081 |

21.1423 |

0.0099 |

0.1891 |

0.8855 |

0.8865 |

0.0057 |

| 20 |

21.02 |

0 |

0 |

-0.045221 |

-0.950544 |

0.0452 |

0.9505 |

- |

- |

0.0076 |

| Sum of IAE |

|

|

|

|

|

0.1529 |

2.4106 |

|

|

|

Table 9.

Statistical error tests for SDM of Photowatt-PWP201.

Table 9.

Statistical error tests for SDM of Photowatt-PWP201.

| No |

Measured Data |

Estimation Data |

IAE |

RE |

MAE |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0.1248 |

1.0315 |

0.128731 |

1.0298 |

0.128525 |

0.0017 |

0.0002 |

0.1648 |

0.1600 |

0.0017 |

| 2 |

1.8093 |

1.03 |

1.86358 |

1.0286 |

1.86111 |

0.0014 |

0.0025 |

0.1359 |

0.1325 |

0.0016 |

| 3 |

3.3511 |

1.026 |

3.43823 |

1.0275 |

3.44318 |

0.0015 |

0.0050 |

0.1462 |

0.1440 |

0.0015 |

| 4 |

4.7622 |

1.022 |

4.86697 |

1.0263 |

4.88742 |

0.0043 |

0.0204 |

0.4207 |

0.4202 |

0.0022 |

| 5 |

6.0538 |

1.018 |

6.16277 |

1.0249 |

6.20464 |

0.0069 |

0.0419 |

0.6778 |

0.6794 |

0.0032 |

| 6 |

7.2364 |

1.0155 |

7.34856 |

1.023 |

7.40273 |

0.0075 |

0.0542 |

0.7386 |

0.7372 |

0.0039 |

| 7 |

8.3189 |

1.014 |

8.43536 |

1.0198 |

8.48403 |

0.0058 |

0.0487 |

0.5720 |

0.5770 |

0.0042 |

| 8 |

9.3097 |

1.01 |

9.4028 |

1.0144 |

9.44363 |

0.0044 |

0.0408 |

0.4356 |

0.4342 |

0.0042 |

| 9 |

10.2163 |

1.0035 |

10.2521 |

1.0049 |

10.2659 |

0.0014 |

0.0138 |

0.1395 |

0.1346 |

0.0039 |

| 10 |

11.0449 |

0.988 |

10.9124 |

0.98884 |

10.9216 |

0.0008 |

0.0092 |

0.0850 |

0.0843 |

0.0036 |

| 11 |

11.8018 |

0.963 |

11.3651 |

0.96341 |

11.37 |

0.0004 |

0.0049 |

0.0426 |

0.0431 |

0.0033 |

| 12 |

12.4929 |

0.9255 |

11.5622 |

0.9256 |

11.5634 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0108 |

0.0104 |

0.0030 |

| 13 |

13.1231 |

0.8725 |

11.4499 |

0.87318 |

11.4588 |

0.0007 |

0.0089 |

0.0779 |

0.0777 |

0.0028 |

| 14 |

13.6983 |

0.8075 |

11.0614 |

0.80525 |

11.0305 |

0.0022 |

0.0309 |

0.2786 |

0.2793 |

0.0028 |

| 15 |

14.2221 |

0.7265 |

10.3324 |

0.72283 |

10.2802 |

0.0037 |

0.0522 |

0.5052 |

0.5052 |

0.0029 |

| 16 |

14.6995 |

0.6345 |

9.32683 |

0.62823 |

9.23473 |

0.0063 |

0.0921 |

0.9882 |

0.9875 |

0.0031 |

| 17 |

15.1346 |

0.5345 |

8.08944 |

0.52465 |

7.94044 |

0.0099 |

0.1490 |

1.8428 |

1.8419 |

0.0035 |

| 18 |

15.5311 |

0.4275 |

6.63955 |

0.41547 |

6.45275 |

0.0120 |

0.1868 |

2.8140 |

2.8134 |

0.0039 |

| 19 |

15.8929 |

0.3185 |

5.06189 |

0.30363 |

4.82563 |

0.0149 |

0.2363 |

4.6688 |

4.6674 |

0.0045 |

| 20 |

16.2229 |

0.2085 |

3.38247 |

0.19168 |

3.10956 |

0.0168 |

0.2729 |

8.0671 |

8.0684 |

0.0051 |

| 21 |

16.5241 |

0.101 |

1.66893 |

0.081626 |

1.3488 |

0.0194 |

0.3201 |

19.1822 |

19.1818 |

0.0058 |

| 22 |

16.7987 |

-0.008 |

-0.13439 |

-0.024974 |

-0.419524 |

0.0170 |

0.2851 |

-212.1750 |

-212.1691 |

0.0063 |

| 23 |

17.0499 |

-0.111 |

-1.89254 |

-0.12747 |

-2.1733 |

0.0165 |

0.2808 |

-14.8378 |

-14.8351 |

0.0068 |

| 24 |

17.2793 |

-0.209 |

-3.61137 |

-0.22501 |

-3.88806 |

0.0160 |

0.2767 |

-7.6603 |

-7.6616 |

0.0071 |

| 25 |

17.4885 |

-0.303 |

-5.29902 |

-0.31709 |

-5.5455 |

0.0141 |

0.2465 |

-4.6502 |

-4.6514 |

0.0074 |

| Sum of IAE |

|

|

|

|

|

0,1856 |

2,6810 |

|

|

|

Table 10.

The statistical metrics of RMSE values provided by FLO algorithm for SDM. DDM. STP6-120/36 and Photowatt-PWP201.

Table 10.

The statistical metrics of RMSE values provided by FLO algorithm for SDM. DDM. STP6-120/36 and Photowatt-PWP201.

| RMSE |

Data Sets |

| Statistical metrics |

SDM |

DDM |

STM6-40/36 |

PWP-201 |

| Max |

0.12876 |

0.13501 |

1.54332 |

0.43731 |

| Min |

0.00303 |

0.01153 |

0.01203 |

0.00975 |

| Mean |

0.08168 |

0.08529 |

0.69211 |

0.21988 |

| Std |

0.03582 |

0.03090 |

0.33856 |

0.149 |

| Var |

0.00128 |

0.00095 |

0.11462 |

0.0222 |

Table 11.

Comparison of , and for proposed FLO algorithm.

Table 11.

Comparison of , and for proposed FLO algorithm.

| Data Sets |

Parameter |

Measured data |

FLO (Proposed) |

BMO [59] |

FA [59] |

HFAPS [59] |

| R.T.C France |

(v) |

0.459 |

0.459 |

0.449 |

0.4509 |

0.4506 |

|

() |

0.6755 |

0.67352 |

0.692 |

0.6894 |

0.6894 |

|

(w) |

0.31005 |

0.30915 |

0.3107 |

0.31085 |

0.31064 |

| STM6-40/36 |

(v) |

16.98 |

16.98 |

- |

17.045 |

16.973 |

|

() |

1.5 |

1.504 |

- |

1.494 |

1.500 |

|

(w) |

25.47 |

25.5381 |

- |

25.477 |

25.459 |

| PWM-201 |

(v) |

12.4929 |

12.4929 |

- |

12.618 |

12.645 |

|

() |

0.9255 |

0.9256 |

- |

0.9085 |

0.9125 |

|

(w) |

11.5622 |

11.5634 |

- |

11.463 |

11.539 |