1. Introduction

In recent years, the importance of research related to hydrocarbon migration pathways in the exploration and development of oil and gas reservoirs has gradually increased, further promoting the development of the theoretical system of hydrocarbon migration(Guo et al.,2023; Hu et al.,2022). The concept of migration pathways emerged after the concept of the petroleum system and was first put forward in the middle of the 20th century. Up to now, it can be divided into the following two viewpoints. The first viewpoint advocates that the comprehensive combination of various migration channels and various factors in a certain petroleum system should be called the migration pathways. The second viewpoint points out that in a certain petroleum system, all the migration paths connecting source rocks and traps form the migration pathways. The difference between the two lies in that the former includes the hydrocarbon migration channels inside the source rocks(Fu and Meng, 2004; Zhang et al.,2000).

The concept of migration pathways came into being in the era when conventional reservoirs were the main reservoirs, and there was no concept of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs at that time(Zhang et al.,2022). This has led to the fact that previous studies on migration pathways focused on the parts with high underground migration capabilities, while relatively little knowledge was gained about the parts with medium or poor underground migration capabilities. When studying the migration performance of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs, it is necessary to consider not only the parts with good migration capabilities in the migration pathways but also the importance of the combination of migration pathways with good and poor migration capabilities in restricting hydrocarbon migration. Secondly, when previous researchers studied migration pathways, they only considered secondary migration and did not study the situation of the internal migration pathways of source rocks in primary migration(Jia et al.,2016; Jiang et al.,2023; Jin et al.,2022; Li et al.,2015; Zhang et al.,2022; Zhang et al.,2023; Zhou et al.,2022).

As a bridge connecting source rocks and reservoirs, the migration pathways, together with source rocks and traps, constitute the essential elements of the oil and gas reservoir system(Wang et al.,2019; Yang et al.,2015; Zhang and Zhao, 2023). Due to the complexity of the factors influencing the hydrocarbon migration pathways, the research level of the migration pathways is far behind that of source rocks and traps, and it has always been a weak link in the field of hydrocarbon migration research. At present, the research on migration pathways mainly focuses on high-porosity and high-permeability sand bodies, faults and fractures, unconformity surfaces, and composite migration pathways, and there has been no differential classification research from the aspects of source rocks and sandstone reservoirs(Ju, 2022; Liu et al.,2021; Shi et al.,2022; Wang et al.,2021; Xu et al.,2019; Zeng et al.,2019; Zhang et al.,2023).

To sum up, to further improve the research theory of migration pathways, this research will mainly focus on the cores and thin sections with differences in oil-bearing properties. Combined with conventional porosity and permeability tests, tests on the changes of permeability under different circumstances, and data such as cast thin sections, it will analyze the characteristics of hydrocarbon migration of source rocks and sandstone reservoirs under various conditions. On this basis, differential analysis and summary will be carried out on the characteristics of migration pathways of different rock types.

2. Geological Setting

The Upper Paleozoic in the Ordos Basin is located in the western part of the North China Plate and is one of the important oil and gas basins in China, with a broad distribution range and unique geological features(Liu et al.,2024). The development of the Upper Paleozoic in the Ordos Basin is affected by various geological factors(Liu et al.,2024). In terms of the tectonic background, it lies on the North China Craton and has experienced a long geological evolution process. The Caledonian Movement caused the whole basin to uplift and undergo erosion, shaping the early paleogeographic pattern. During the Hercynian Movement, the interior of the basin was dominated by uplift and subsidence movements, which controlled the distribution of sedimentary facies belts and the changes in strata thickness at different stages of the Upper Paleozoic and also played a key role in the formation of coal-measure source rocks. The Indosinian Movement and the Yanshan Movement further modified the tectonic morphology of the basin and promoted the formation and finalization of oil and gas reservoirs. This series of tectonic movements jointly laid the foundation for the current geological appearance of the Upper Paleozoic(Sun et al.,2024; Wu et al.,2024; Yuan et al.,2024).

From the perspective of tectonic unit division, the Upper Paleozoic in the Ordos Basin can be divided into multiple tectonic units, such as the Yimeng Uplift, Weibei Uplift, Tianhuan Depression, and Shanbei Slope(Xiao et al.,2005). The Yimeng Uplift is located in the northern part of the basin and has been in an uplifted state for a long time. The thickness of the Upper Paleozoic strata is relatively thin, and some formations are missing. The structure is relatively simple, mostly consisting of gentle folds and a small number of faults. Although the current oil and gas exploration level is relatively low, it still has certain potential. The Weibei Uplift is located in the southern part of the basin. The tectonic activities here are relatively complex, with multiple faults and folds developed. The Upper Paleozoic strata have suffered different degrees of erosion, but there are often good oil and gas shows in the surrounding areas, making it one of the key areas for oil and gas exploration. The Tianhuan Depression is located in the western part of the basin, extending in a nearly north-south direction. The Upper Paleozoic strata here have a relatively large sedimentary thickness, and a thick set of paralic and continental clastic rock strata has been developed. Source rocks are well developed here and it is an important oil and gas generation and accumulation area in the basin. The Shanbei Slope is located in the middle of the basin. It is a large westward-dipping monocline structure. The structure is relatively simple and the strata are gentle. The Upper Paleozoic sandstone reservoirs are well developed and have a good configuration relationship with the source rocks. It is the main target area for oil and gas exploration in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin, and several large gas fields have been discovered here(Liu et al.,2022; Hua et al.,2012; Li et al.,2014; Wang et al.,2024).

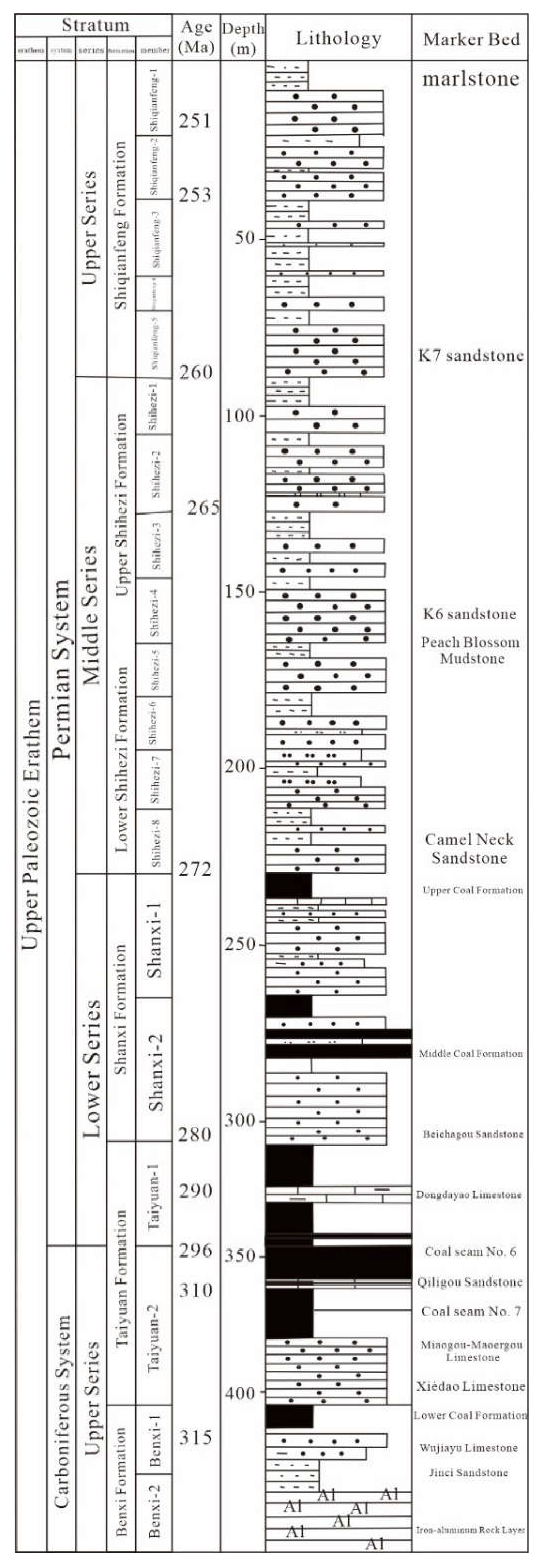

The target strata for this study are the Upper Paleozoic in the Ordos Basin, which contains several important stratigraphic formations, such as the Benxi Formation, Taiyuan Formation, and Shanxi Formation(

Figure 1). Among them, the Benxi Formation has developed paralic sedimentary strata, including coal seams, dark mudstones, and sand bodies. It is not only a formation where source rocks are developed but also some sand bodies are potential reservoirs. The Taiyuan Formation also has paralic sedimentary strata. Coal seams, dark mudstones, and other source rocks are widely distributed, and various types of sand bodies provide conditions for oil and gas storage. The Shanxi Formation is mainly composed of continental clastic rocks. Sandstone reservoirs are relatively well developed and, combined with source rocks, form a good source-reservoir-cap combination, making it an important oil and gas exploration formation. Some sandstone reservoirs in the Shanxi Formation have relatively good physical properties and stable distribution, which are one of the key factors for forming Upper Paleozoic oil and gas reservoirs.

3. Experimental Methods

This experiment mainly selects mudstone (coal) and sandstone samples from the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin. By measuring and comparing relevant experimental data of permeability and porosity in parallel and perpendicular to the bedding planes, as well as before and after fracturing, the oil-gas migration situations of mudstone (coal) and sandstone in parallel and perpendicular to the bedding planes can be analyzed. The influences of fractures on oil-gas migration in different lithological strata before and after fracturing can be obtained.

3.1. Experimental Principles, Instruments, and Steps for the Study of the Differences in Conducting Performance of Full-Diameter Argillaceous Rocks and Coal Rocks.

According to the petroleum and natural gas industry standard of the People’s Republic of China SY-T5336-1996, the Conventional Core Analysis Method, the permeability tests were carried out on the full-diameter samples collected. The differences in their conducting performance were analyzed by measuring the permeability in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the bedding planes of heterogeneous rocks such as fractured argillaceous rocks and coal rocks mentioned above. The principles, instruments, and equipment, as well as the method steps for the measurement, are as follows:

- (1)

Measurement Principle

When gas flows in a rock sample, the following formula for calculating permeability can be obtained according to Darcy’s law of one-dimensional steady-state filtration of gas (Liu,2010):

In the formula:

ka represents the permeability of the rock, with the unit of μm²;

Qo represents the flow rate of air passing through the rock per unit time, with the unit of cm³/s;

μ represents the viscosity of the fluid, with the unit of 10⁻3 Pa·s;

L represents the length of the rock, with the unit of cm;

p1 and p2 represent the pressure differences before and after the fluid passes through the rock, with the unit of MPa;

A represents the cross-sectional area through which the air passes through the rock, with the unit of cm².

(2)

Instruments and Equipment

The instruments used in the experiment are as follows:

① Permeameter;

② Full-diameter core holder;

③ Vacuum pump;

④ Pressure pump;

⑤ High-pressure gas cylinder;

⑥ Air compressor.

- (3)

Experimental Steps

① After removing oil (salt) from the samples to be tested, dry them and place them in a desiccator for standby.

② Use 2 - 3 standard blocks to test the instrument’s reliability. That is, compare the measured values with the calibrated values. If the relative error does not exceed 5%, the instrument is considered qualified.

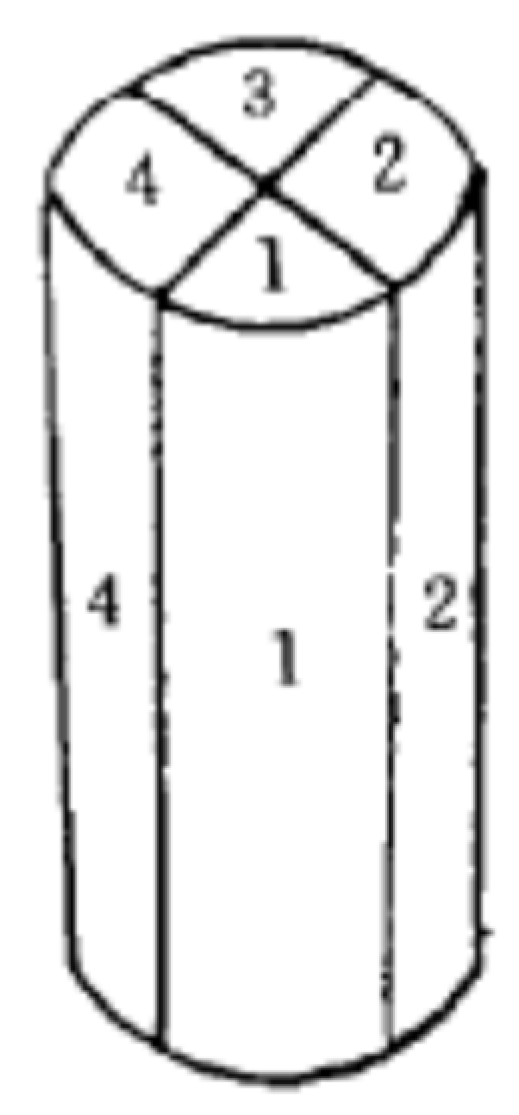

③ Divide the side surface of the cylindrical rock sample into four equal parts (as shown in

Figure 3-). Surfaces 1 and 3 are a pair of air inlet and outlet surfaces, and surfaces 2 and 4 are another pair of air inlet and outlet surfaces. Select a pair of air inlet and outlet surfaces (1, 3) as the measurement direction, and surfaces 2 and 4 perpendicular to surfaces 1 and 3 are taken as another measurement direction. In the measurement report, the permeability value in the middle is marked as Rmax, and the other two measured values are marked as R90.

④ Cover surfaces 1 and 3 with two metal meshes of corresponding sizes, and then cover the meshes with two smooth metal arc plates of the same size.

Figure 2.

Equal Division Diagram of the Side Surface of the Rock Sample.

Figure 2.

Equal Division Diagram of the Side Surface of the Rock Sample.

⑤ Place the metal mesh and the arc plate on one pair of surfaces of the core, and fix them with rubber bands. Evacuate the air and send the core into the holder, ensuring that the rock sample and the upper and lower plungers are on the same central line. Push a pressure 0.05 MPa higher than the confining pressure into the top of the core, and then add a confining pressure of 1.4 - 2.8 MPa. To avoid turbulence, the flow velocity of the test gas should be less than 8 cm³/s. After the flow velocity becomes stable, record the upstream and downstream pressures (C value, hw) and the value of the restrictor.

⑥ When measuring the vertical permeability, place a sieve of the corresponding size on each of the upper and lower end surfaces of the rock sample. Evacuate the air, send the core into the core holder, and then release the air. Apply an upward pressure of 0.05 MPa higher than the confining pressure, and then add a confining pressure of 1.4 - 2.8 MPa. Start to measure the flow velocity. After the flow velocity becomes stable, record the upstream and downstream pressures and the flow value of the restrictor.

⑦ After a batch of samples has been measured, it is necessary to use 2 - 3 standard samples to measure their values to verify the reliability of the instrument throughout the entire testing process.

Based on the measurement results of the permeability in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the bedding planes of the samples as well as the observation results of the pore structure of the casting thin sections, the differences in the conducting performance in different directions of the full-diameter argillaceous rocks and coal rocks are compared and analyzed. On this basis, the charging direction of natural gas in the full-diameter argillaceous rocks and coal rocks is judged.

3.2. Experimental Principles, Instruments, and Steps for the Study of the Differences in Conducting Performance of Porous and Fractured Mudstones and Sandstones

According to the petroleum and natural gas industry standard SY-T5336-1996 of the People’s Republic of China, the Conventional Core Analysis Method, the permeability tests were carried out on the collected sandstone and mudstone samples. The principles, instruments, and equipment, as well as the method steps for the measurement, are as follows:

(1) Measurement Principle

The experimental principle is the same as that in

Section 3.1.

(2) Instruments and Equipment

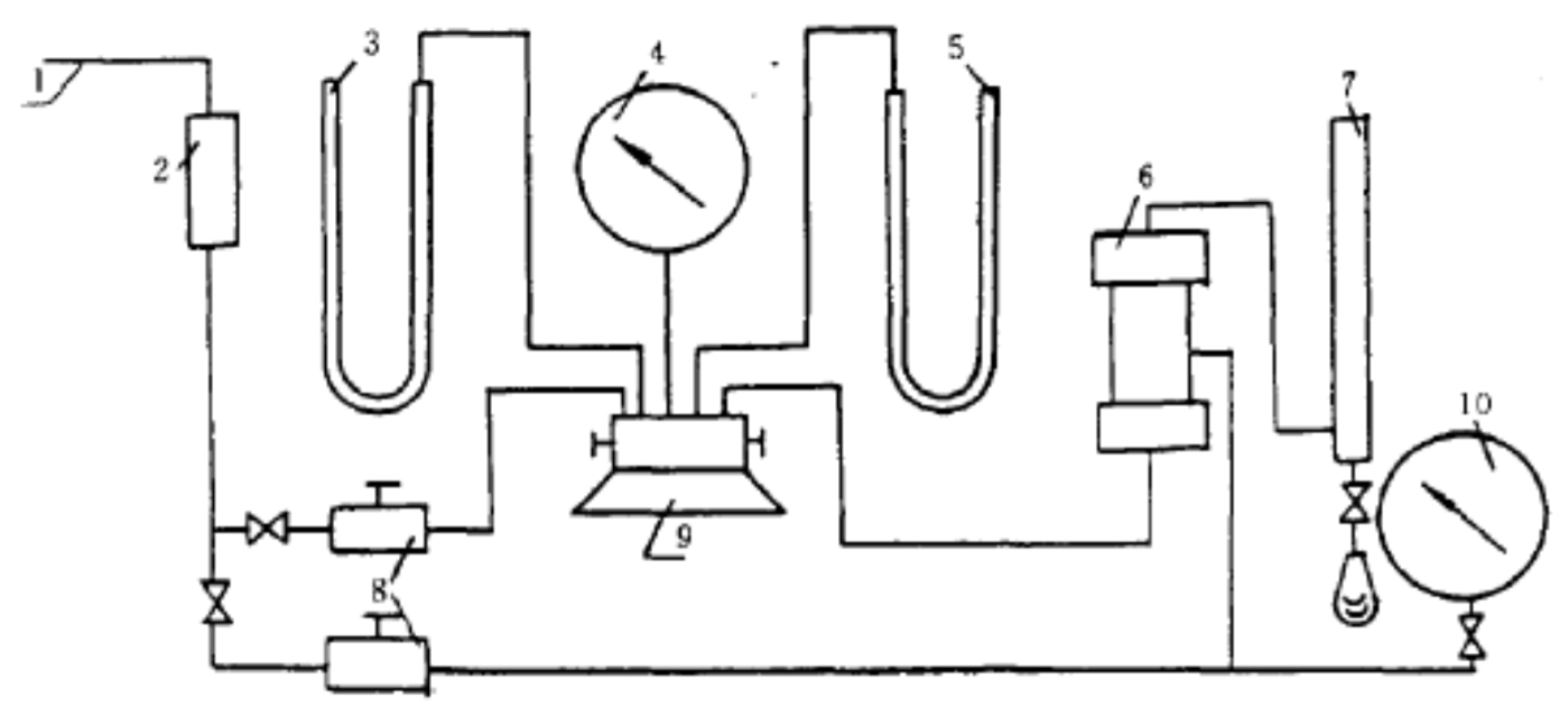

The schematic diagram of the permeameter, which is one of the processes for measuring gas permeability, is shown in

Figure 3-2. It specifically includes:

① Pressure gauges, mercury manometers, and water column manometers;

② Soap film flow meters or restrictors;

③ Hassler-type core holders. The Hassler-type core holders are suitable for cylindrical rock samples. To seal the rock samples, the rubber sleeves in the holders should have good elasticity, and the confining pressure should be set at 1.4 - 2.8 MPa.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of the Permeameter.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of the Permeameter.

1-Gas source;2-Drying tower;3-Mercury manometer;4-Standard pressure gauge;5-Water column manometer;6-Core holder;7-Soap film flowmeter;8-Regulating valve;9-Six-way valve seat;10-Pressure gauge

(3) Experimental Steps

① Use 3 - 5 standard blocks to check the instrument’s reliability. Compare the measured values of the standard blocks with their calibrated values. If the relative error is within 5%, the instrument used is considered qualified.

② For the measurement of core dimensions, vernier calipers can be used to measure regularly shaped rock samples. If the rock samples need to be encapsulated with other materials, use calipers to measure their lengths, and use other methods to measure their volumes. Then divide the total volume by the length to obtain the average cross-sectional area of the rock samples.

③ Load the rock samples to be tested into the appropriate core holders and apply the sealing pressure.

④ When dry gas passes through the rock samples, measure the flow velocity of the gas and adjust the pressure difference at both ends of the rock samples by adjusting the flow velocity of the gas. Record the inlet and outlet pressures as well as the gas flow velocity.

⑤ After a batch (one time) of samples has been measured, re-measure the standard blocks according to the requirements in the first step of this procedure. Compare the measured values with the standard values to check whether they meet the requirements. If they do not meet the requirements, find out the reasons and re-measure the samples.

Based on the measurement results of the permeability in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the bedding planes of the samples as well as the observation results of the pore structure of the casting thin sections, compare and analyze the differences in the conducting performance in different directions of the porous and fractured mudstone and sandstone samples. On this basis, judge the charging direction of natural gas in the permeable and fractured mudstone and sandstone.

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Experiments on Porosity and Permeability of Mudstone Samples in the Directions Parallel and Perpendicular to the Bedding Plane

Through conventional permeability experiments on 12 mudstone samples in 3 groups, the test results are shown in

Table 1. For sample E13Y6N, the porosities in the direction parallel to the bedding plane were measured to be 10.2% and 9.1% respectively, and the permeabilities were 0.0802×10⁻³μm² and 130.0×10⁻³μm² respectively (sample E13Y1NH2 contains fractures). In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the porosities were 10.4% and 9.9% respectively, and the permeabilities were 0.0440×10⁻³μm² and 0.0618×10⁻³μm² respectively; the average value was 0.0529×10⁻³μm². For sample E13Y1N, the porosities in the direction parallel to the bedding plane were 1.4% and 1.6% respectively, and the permeabilities were 0.0194×10⁻³μm² and 0.0189×10⁻³μm² respectively, with an average value of 0.0192×10⁻³μm². In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the porosities were 0.7% and 0.8% respectively, and the permeabilities were 0.0216×10⁻³μm² and 0.0162×10⁻³μm² respectively; the average value was 0.0189×10⁻³μm². For sample E9Y8N, the porosities in the direction parallel to the bedding plane were 1.4% and 1.5% respectively, and the permeabilities were 0.0551×10⁻³μm² and 0.1080×10⁻³μm² respectively, with an average value of 0.0816×10⁻³μm². In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the porosities were 2.2% and 1.1% respectively, and the permeabilities were 0.0223×10⁻³μm² and 0.0205×10⁻³μm² respectively; the average value was 0.0214×10⁻³μm².

The difference in porosity between the direction parallel to the bedding plane and that perpendicular to the bedding plane of mudstone is not significant either. The permeabilities are generally between 0.0162-0.108×10⁻³μm². The average permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is 0.0603×10⁻³μm², and the average permeability in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is 0.03107×10⁻³μm². The permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is higher than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane.

It can be seen from the above that the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of mudstone is higher than that in the vertical direction, and the ratio of the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane to that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is generally between 1.013 - 3.811.

4.2. Experiment on the Variation Laws of Porosity and Permeability of Mudstone Samples in Two Directions under Pressurization and Depressurization Conditions

To simulate the burial and uplift processes of hydrocarbon source rocks under real underground conditions as much as possible, based on the above experiments, some mudstone samples were selected and vertically pressurized. During the pressurization process, the changes in their permeability with the variation of pressure were measured. After the pressurization measurement was completed, the samples were depressurized, and the changes in the samples’ permeability as the pressure decreased were measured simultaneously.

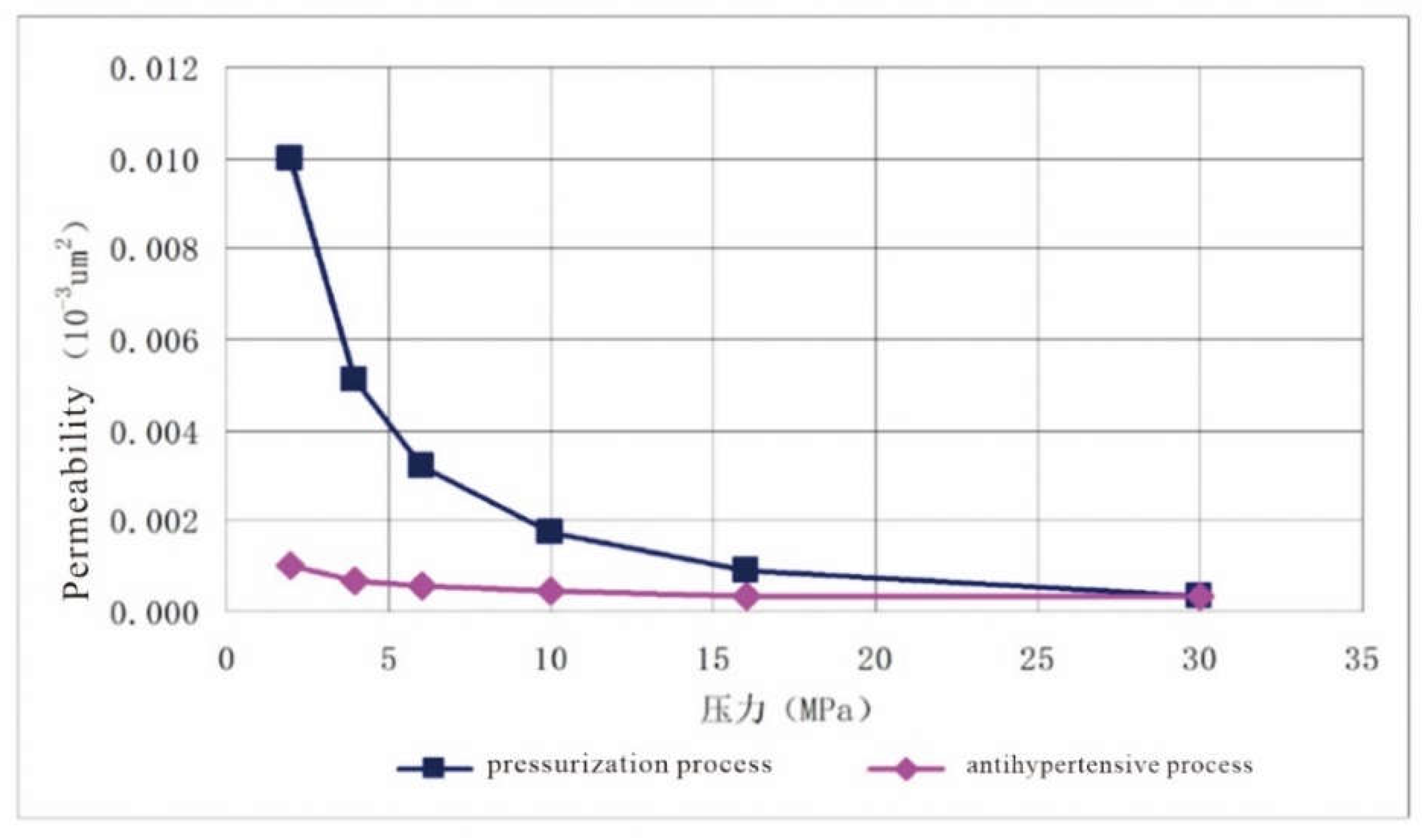

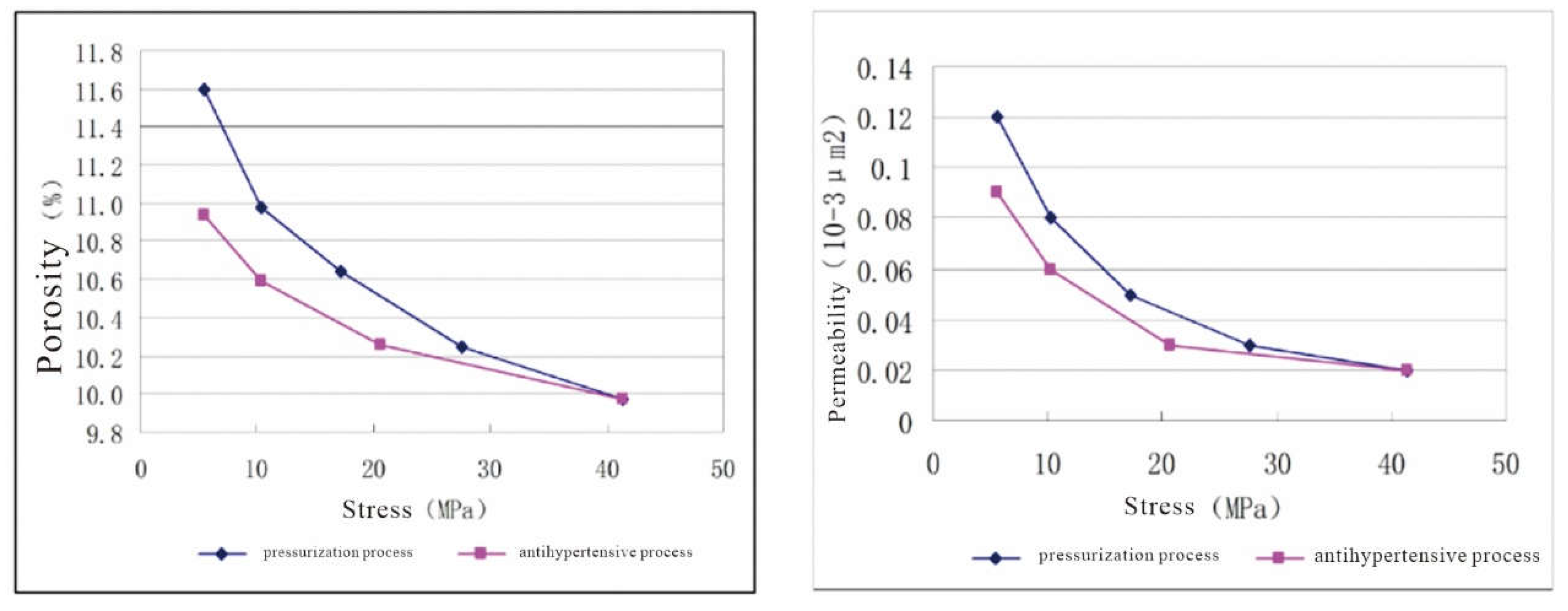

Figure 4 shows two permeability variation curves of a certain sample during the pressurization process and the depressurization process. As can be seen from the figure, during the process in which the pressure increased from the initial state to 10 MPa, the permeability of this sample dropped rapidly by 80%. During the process in which the pressure increased from 10 MPa to 30 MPa, the permeability decreased relatively slowly. Eventually, after the pressurization process was completed, the permeability of the mudstone sample was only about 3% of the original value. During the depressurization process, the permeability of the sample gradually recovered, with an increase of approximately 75%.

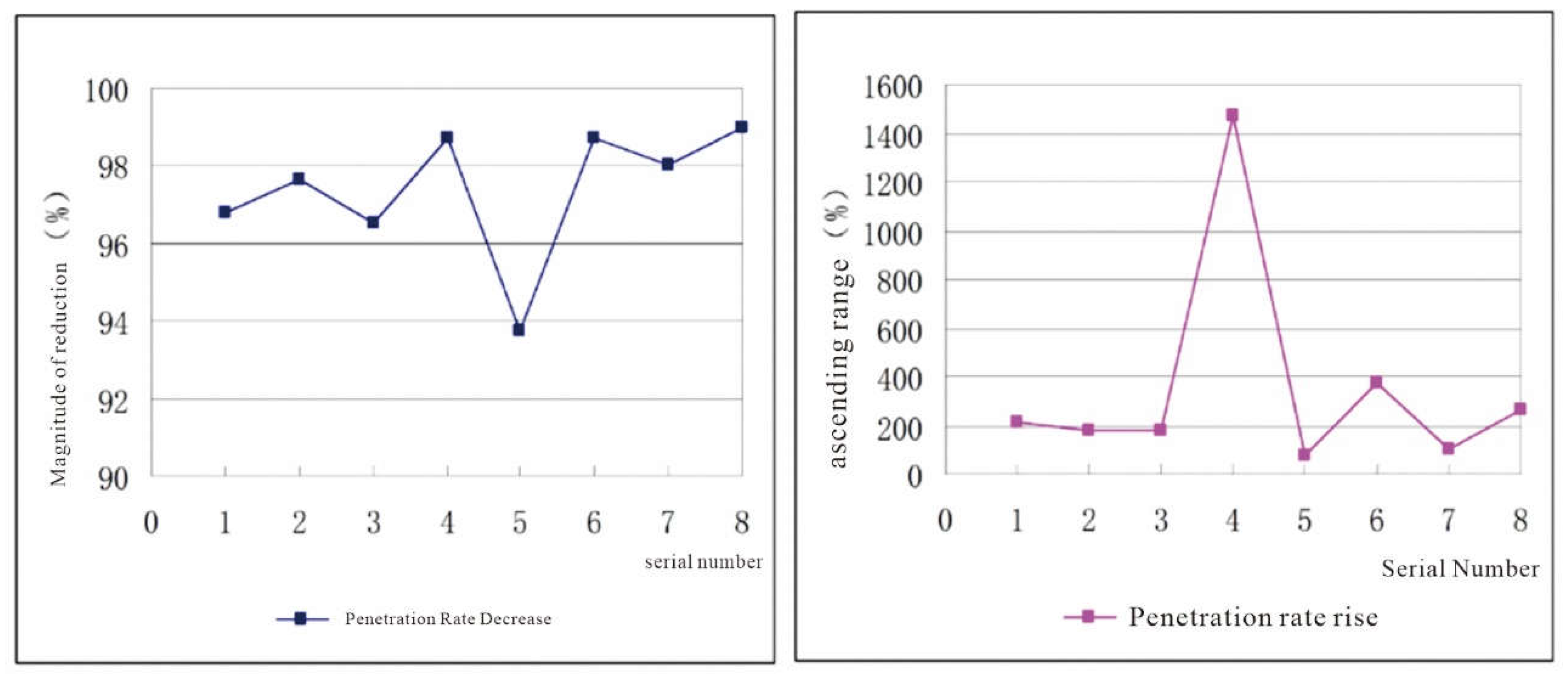

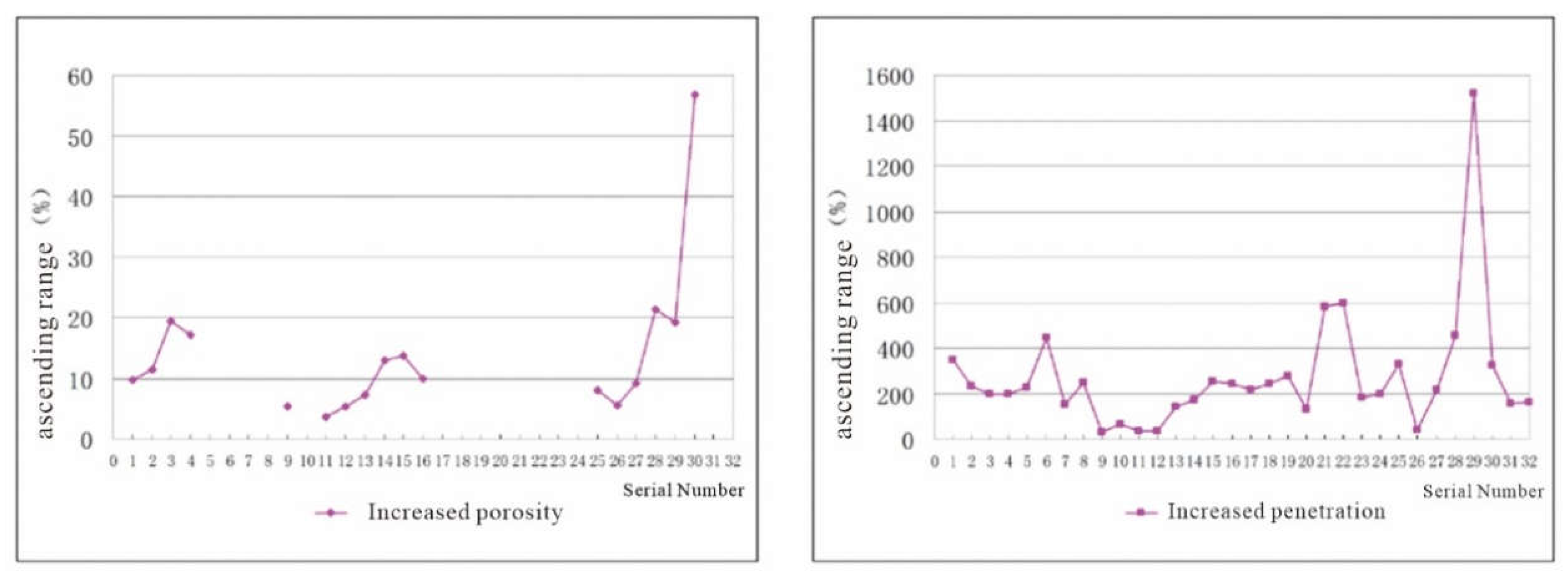

As shown in

Figure 5, through the analysis of the experimental results of several groups of samples measured, the reduction and increase ranges of their permeability during the pressurization and depressurization processes were obtained. During the pressurization process, the reduction ranges of the permeability of several groups of samples were between 93.72% and 98.96%, and the average value was 97.38375%. Under the pressure of 30 MPa, the permeability was only 97% of the original value.

During the depressurization process, the increase ranges of the permeability of several groups of samples were between 75.51% and 1472.65%, and the average value was 357.6275%. It can be seen that the permeability of mudstone increased significantly during the depressurization process.

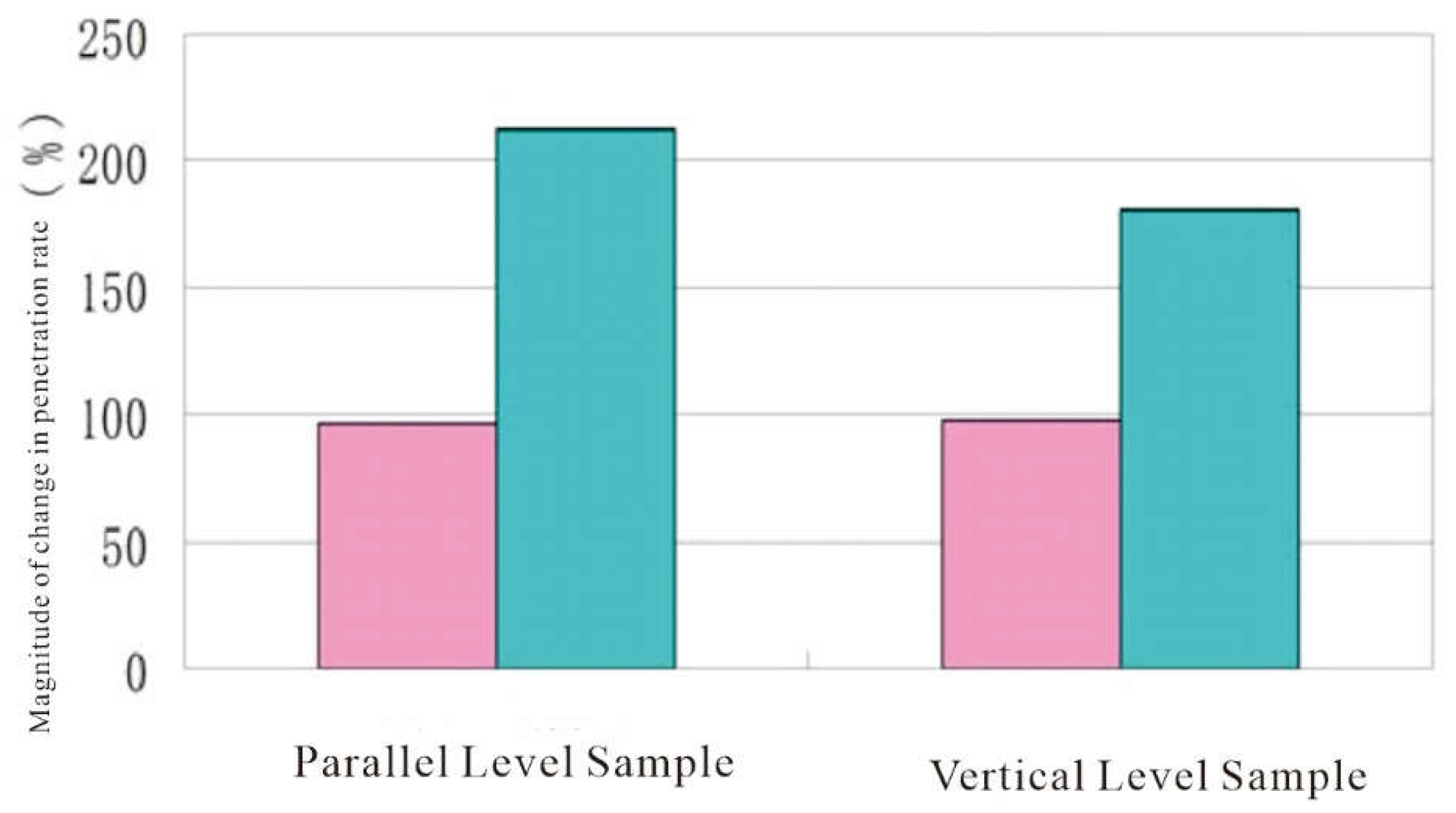

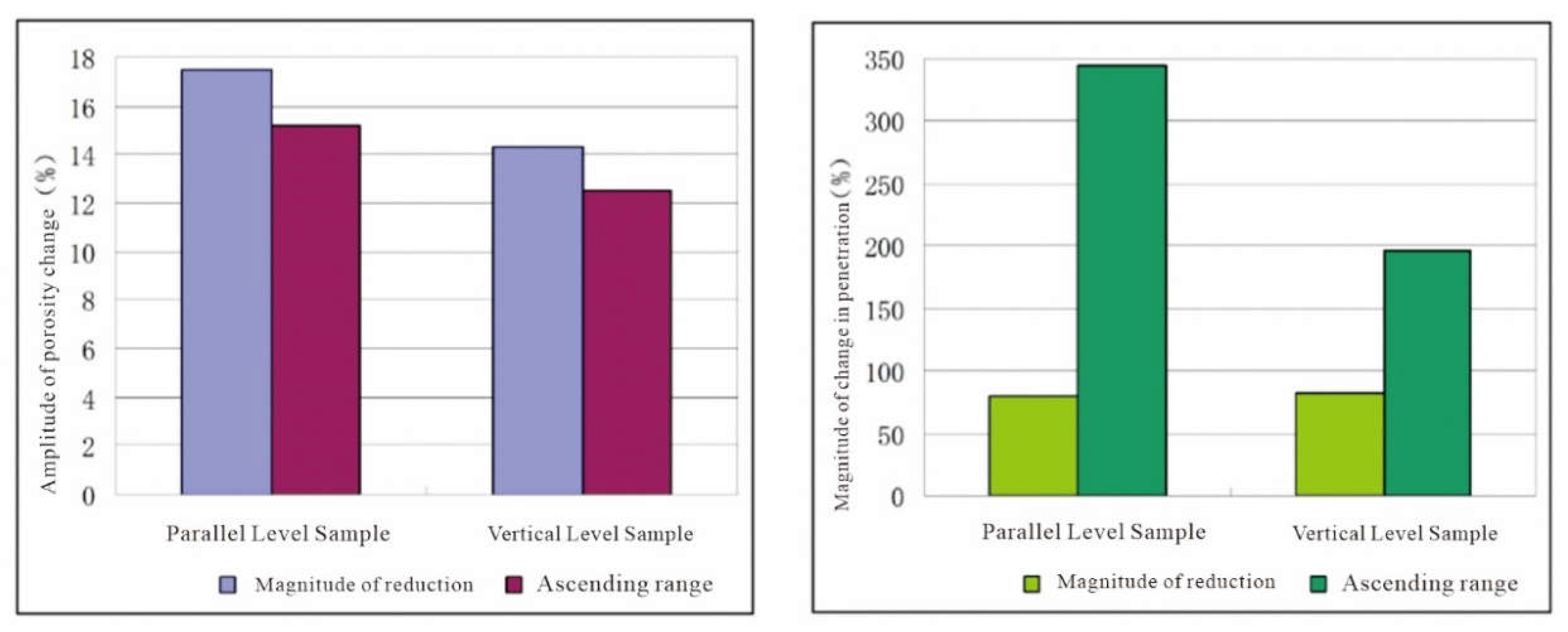

As shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, in the experiments of pressurization and depressurization, the variation laws of permeability of mudstone samples in two directions were measured simultaneously. During the pressurization process, the permeabilities of the mudstone in both the direction parallel to the bedding plane and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane showed a decreasing trend. Among them, the average reduction rate of permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane was 96.72%, and that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane was 98.04%. This indicates that during the burial process, the permeability of the mudstone samples decreased rapidly, and the permeabilities in both the direction parallel to the bedding plane and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane decreased significantly.

However, the situation was different during the depressurization process. The increased range of permeability in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane was significantly smaller than that in the direction parallel to the bedding plane. The average value of the former was 211.80%, while that of the latter was 180.39%. This indicates that during the depressurization process, the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is better than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, that is, in the underground uplift environment, the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is superior to that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane.

4.3. Experiment on the Changes in Permeability of Mudstone Samples Before and After Fracturing, as well as the Changes in Permeability During Pressurization and Depressurization After Fracturing

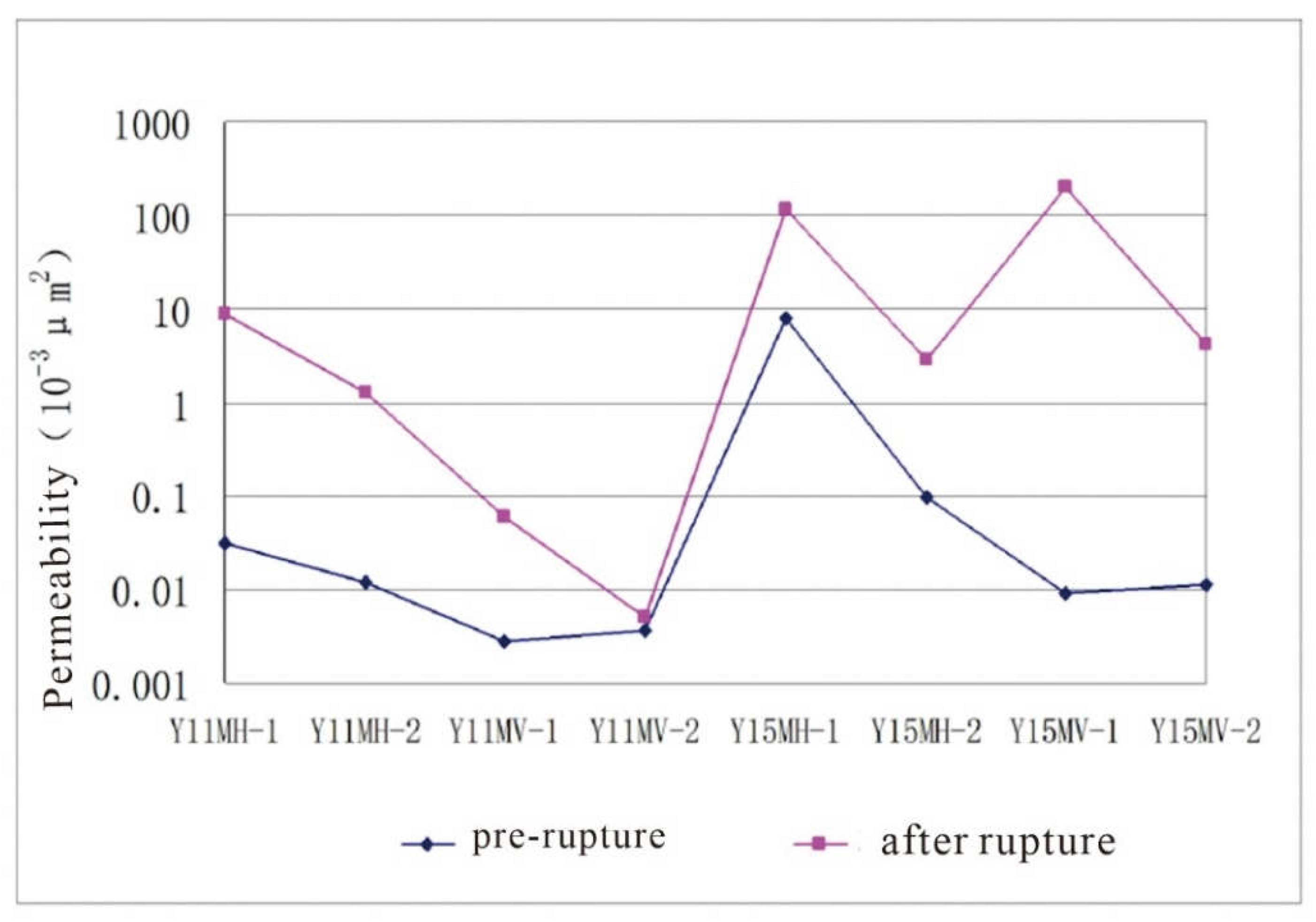

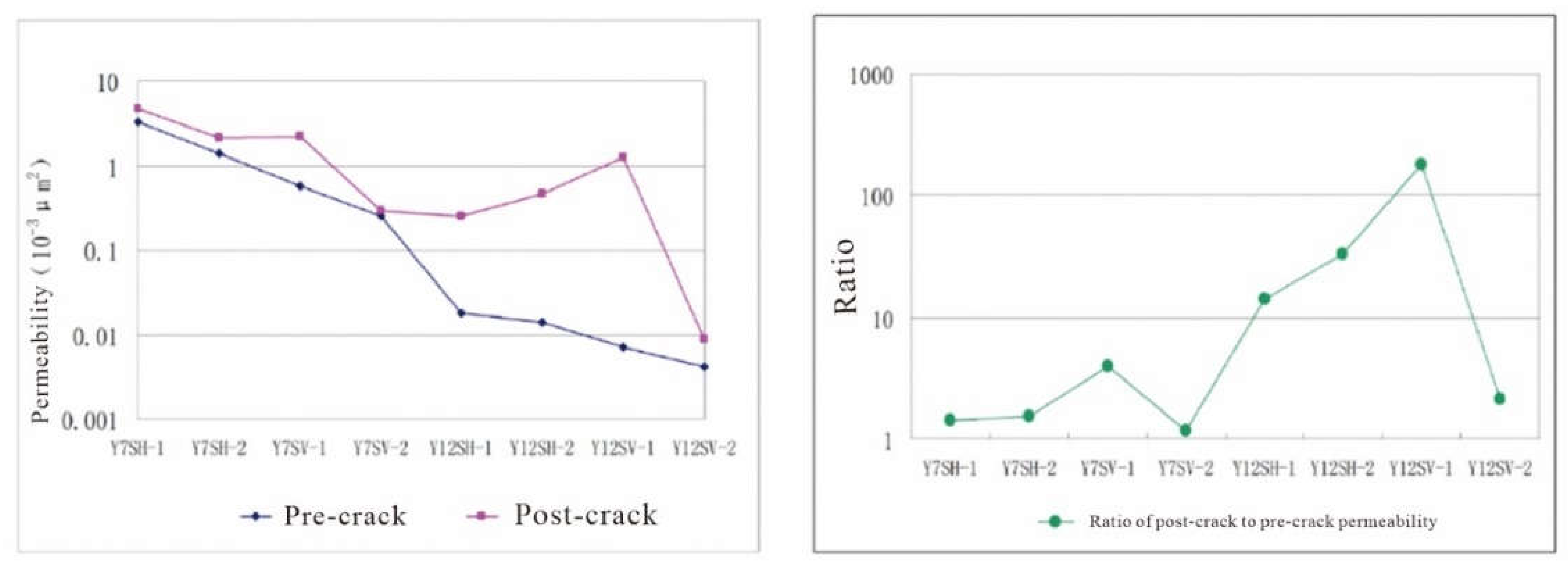

In real underground situations, as the burial depth further increases, mudstone will develop fractures and break, which leads to significant changes in the permeability of mudstone. The purpose of this experiment is to study the variation law of permeability before and after its fracturing.

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the permeability data of mudstone samples before and after fracturing. We can see that the permeability of mudstone has been significantly improved after fracturing. The average permeability after fracturing is about 41 times that before fracturing, and at its highest, the ratio of permeability before and after fracturing even reached 21,000.

The sample data mentioned above indicates that the fractures in mudstone have a significant improving effect on the permeability of mudstone. The experiment further illustrates that mudstone and the fractures it generates can serve as a migration system to constrain the migration of oil and gas.

Further experiments on the changes in permeability during pressurization and depressurization were carried out on the already fractured mudstone samples. It was found that there were differences in the obtained results. For some samples, the permeability would decrease significantly with further pressurization and depressurization. For some other samples, the permeability would further increase whether during pressurization or depressurization. And for still some samples, there was little change in permeability. During this process, since the permeability of the mudstone itself had been compacted to almost the limit, the influence of its permeability on the experimental results was negligible. During the further pressurization process, the factor that had the greatest impact on the permeability test results was the fractures generated after fracturing. Due to the differences in the extension directions and the number of fractures generated by different samples with pressurization, it might lead to different permeability test results for each sample. In summary, it is speculated that the reason for this phenomenon might be related to the directions and number of fractures in the mudstone. For this reason, we conducted further experiments to explore the impact of the fracture extension direction on the permeability results measured during pressurization.

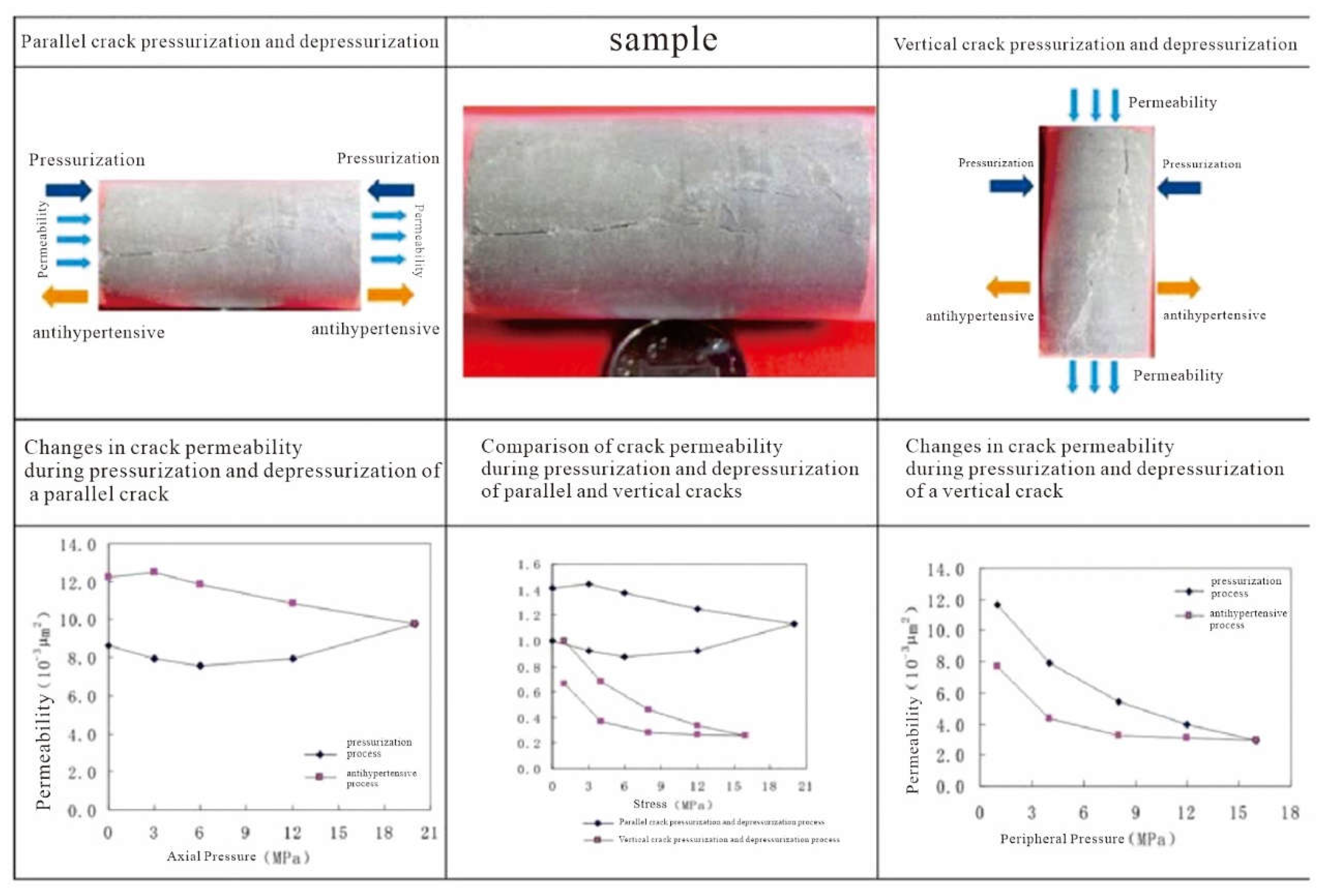

According to the test results, under the pressurization condition where the pressure is parallel to the fractures, the permeability of the fractures increases with the increase in pressure. During the depressurization process, the permeability further increases and is greater than that in the initial state. However, under the pressurization condition where the pressure is perpendicular to the fractures, the permeability of the fractures decreases rapidly with the increase in pressure. During the depressurization process, the permeability gradually recovers but is less than that in the initial state. This indicates that after the mudstone is fractured, the changes in its permeability during further burial or uplift are related to the directions and numbers of the fractures generated. If most of the fractures generated after the mudstone is fractured are perpendicular to the bedding plane, the permeability of these fractures will drop sharply during the further pressurization process. If most of the fractures generated after the mudstone is fractured are parallel to the bedding plane, the permeability will eventually increase slightly with the increase in pressure. Generally speaking, the conducting performance of fractures parallel to the bedding plane is usually better than that of fractures perpendicular to the bedding plane. But overall, as long as fractures are generated in the mudstone, its permeability will be significantly changed.

Figure 8.

Changes in the permeability of mudstone fractures during the pressurization and depressurization processes with fractures in different directions (Liu,2022).

Figure 8.

Changes in the permeability of mudstone fractures during the pressurization and depressurization processes with fractures in different directions (Liu,2022).

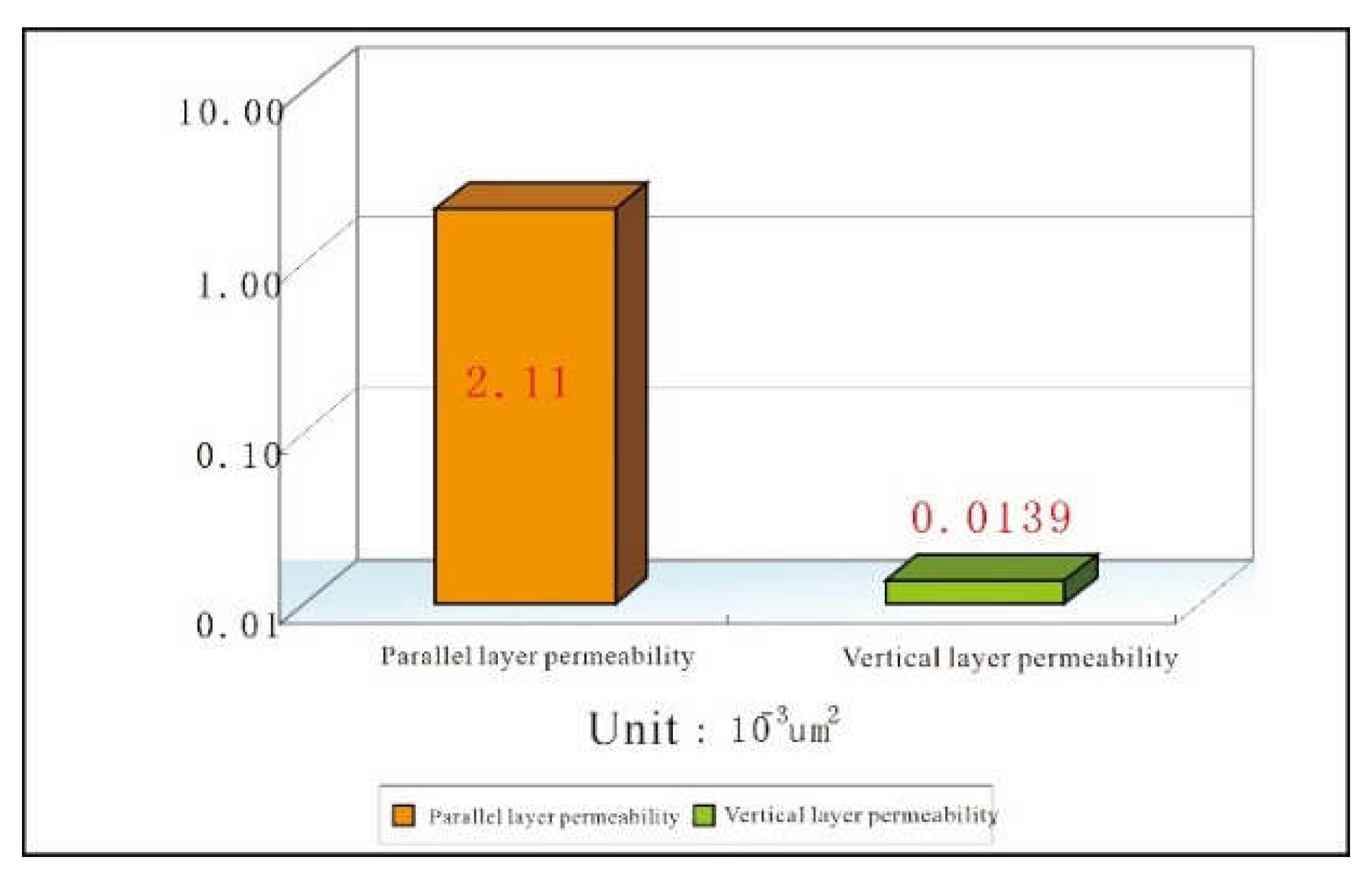

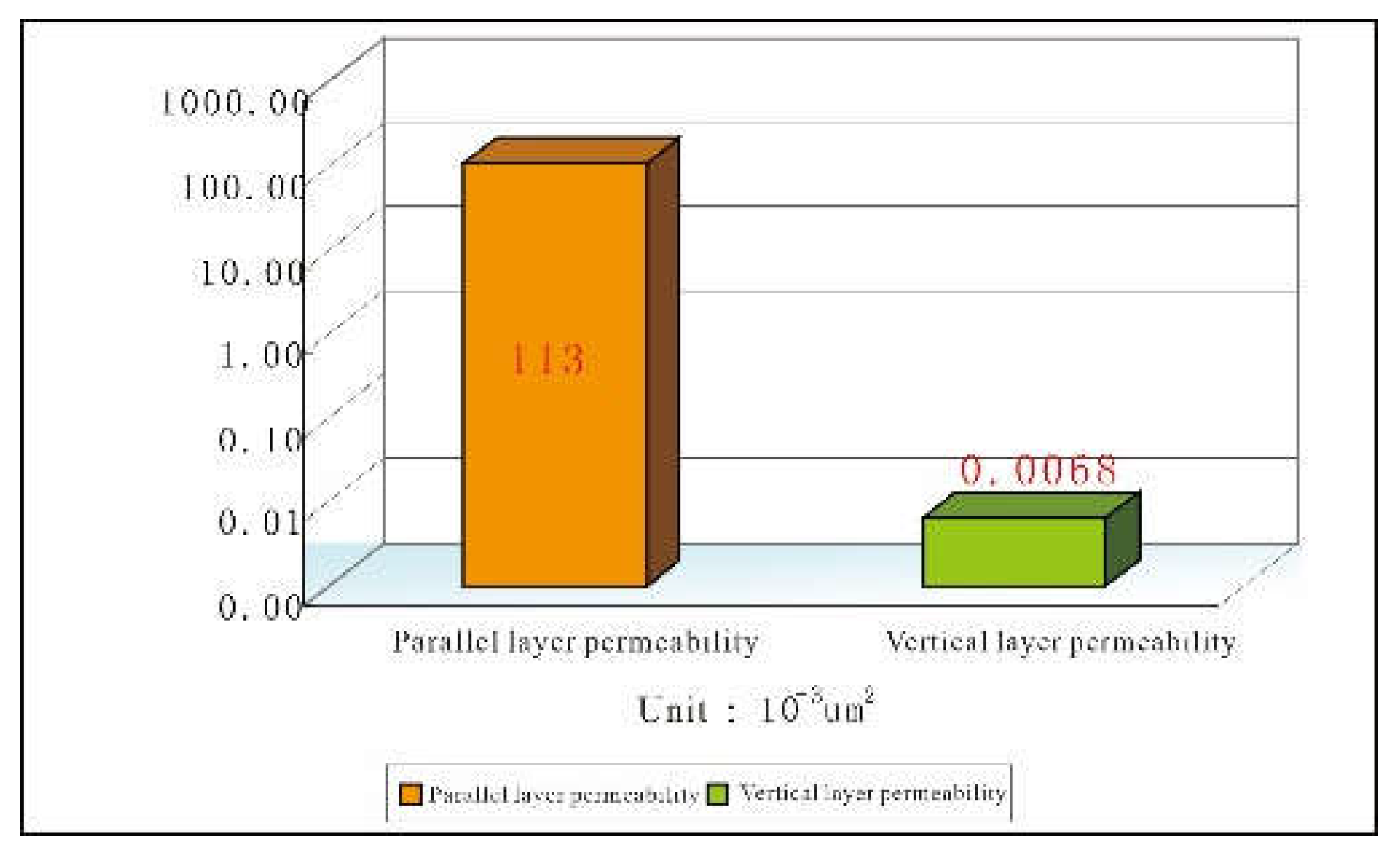

4.4. Experiments on the Porosity and Permeability of Sandstone Samples in the Directions Parallel and Perpendicular to the Bedding Plane

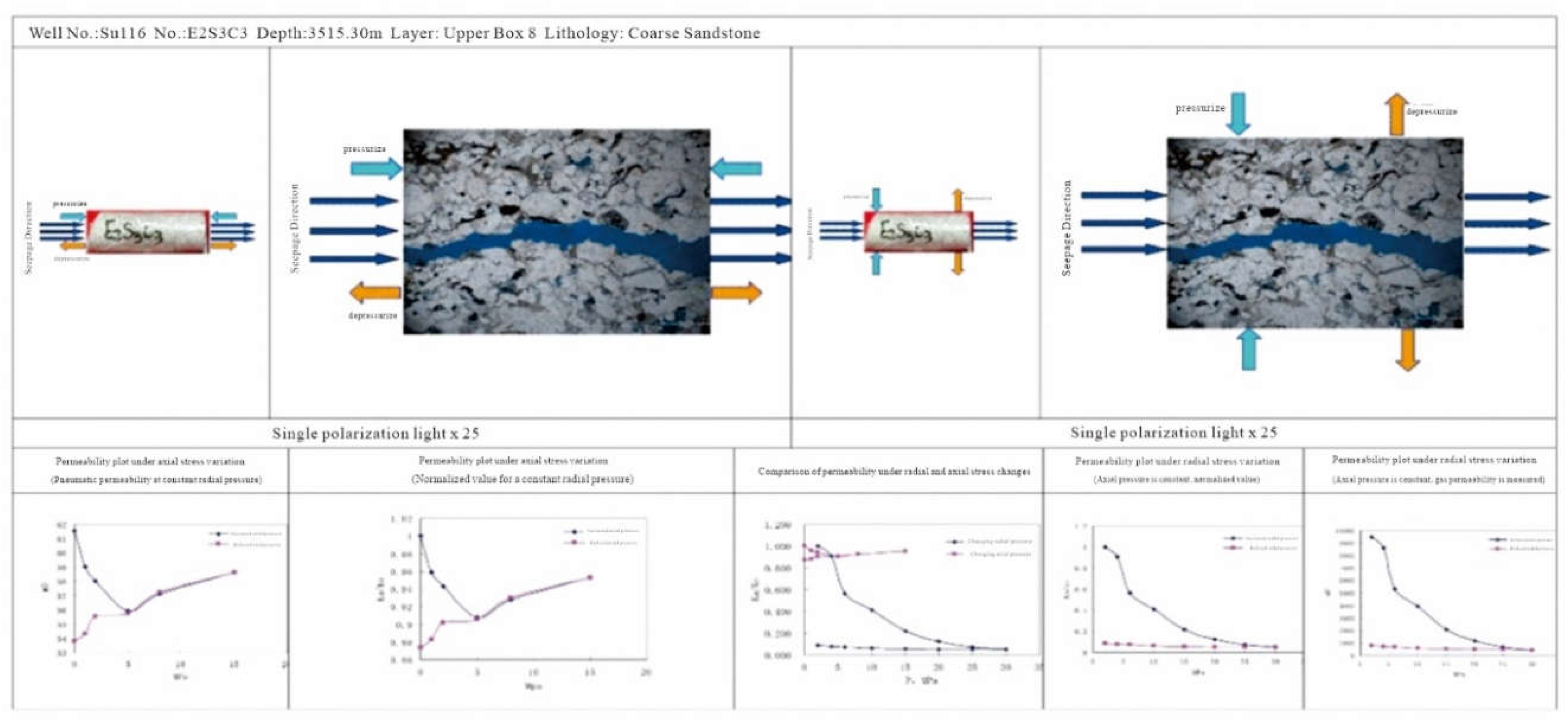

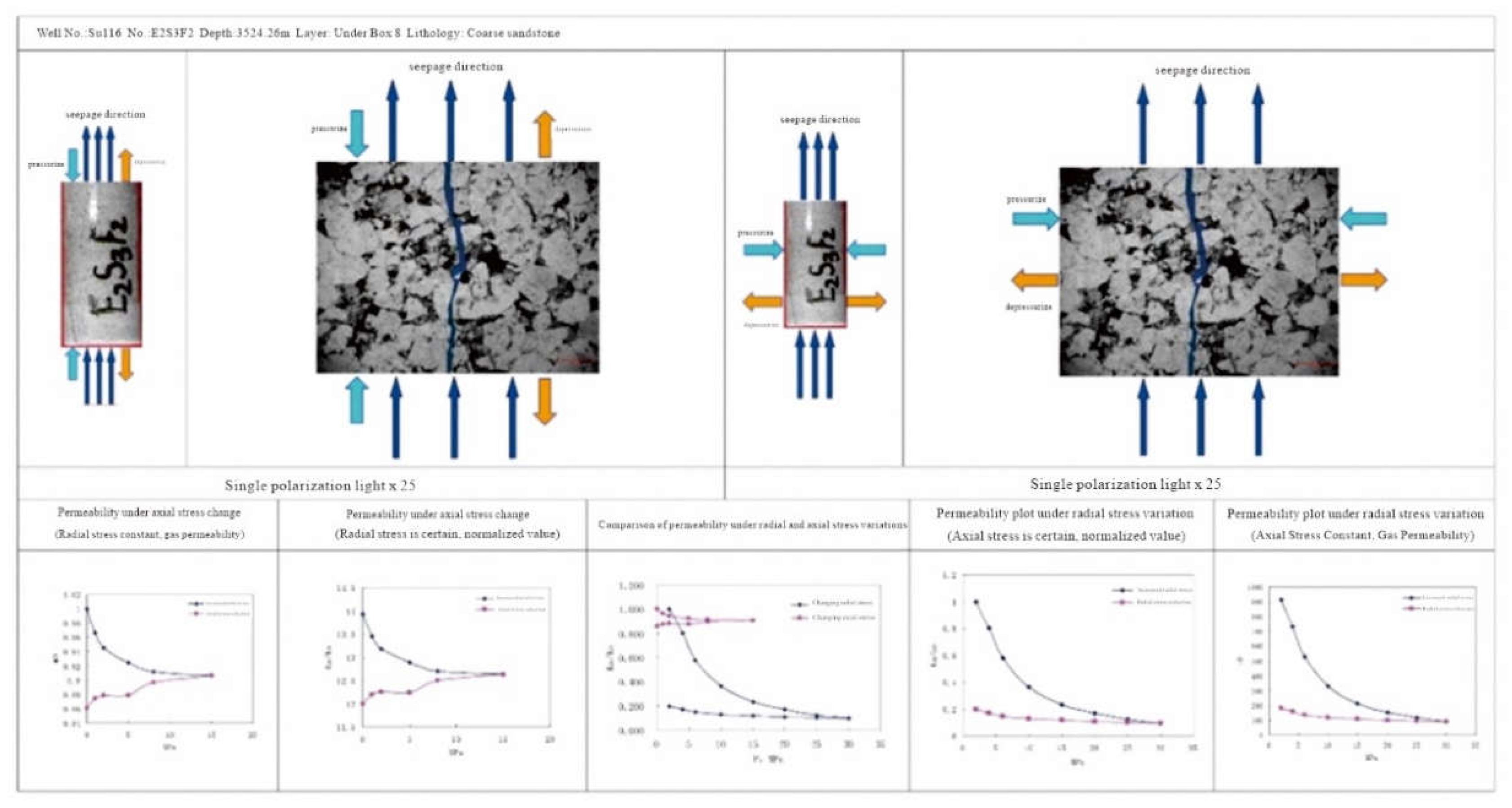

The results of permeability in different directions of three groups of samples measured in the experiment are shown in

Table 2. For fine sandstone, the porosities in the direction parallel to the bedding plane are 1.3% and 1.3% respectively, and the permeabilities are 0.0486×10⁻³ μm² and 0.0492×10⁻³ μm² respectively. The average permeability is 0.0489×10⁻³ μm². In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the porosities are 1.9% and 2.4% respectively, and the permeabilities are 0.0391×10⁻³ μm² and 0.0317×10⁻³ μm² respectively. The average permeability is 0.0354×10⁻³ μm². For medium sandstone, the porosities in the direction parallel to the bedding plane are 7.3% and 7.7% respectively, and the permeabilities are 0.182×10⁻³ μm² and 0.181×10⁻³ μm² respectively. The average permeability is 0.182×10⁻³ μm². In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the porosities are 5.2% and 6.1% respectively, and the permeabilities are 0.072×10⁻³ μm² and 0.073×10⁻³ μm² respectively. The average permeability is 0.072×10⁻³ μm². For coarse sandstone, the porosities in the direction parallel to the bedding plane are 9.8% and 10.2% respectively, and the permeabilities are 4.540×10⁻³ μm² and 3.150×10⁻³ μm² respectively. The average permeability is 3.845×10⁻³ μm². In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the porosities are 10.3% and 9.7% respectively, and the permeabilities are 1.170×10⁻³ μm² and 1.580×10⁻³ μm² respectively. The average permeability is 1.375×10⁻³ μm².

It can be seen from the above that for porous sandstone, there is not much difference in porosity between the direction parallel to the bedding plane and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, but there is a relatively large difference in permeability. The permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is higher than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, and the ratio of the two is generally between 1.38 and 2.80.

4.5. Experiment on the Variation Rules of Porosity and Permeability in Two Directions of Sandstone Samples under Pressurization and Depressurization Conditions

Figure 9 shows two curves of porosity and permeability changes of a certain sample during the pressurization process and the depressurization process. As shown in the figure, during the process when the pressure increased from the initial state to 42 MPa, the permeability of this sample dropped rapidly by 83%. Eventually, after the pressurization process ended, the permeability of the sandstone sample was only about 17% of the original value. During the depressurization process, the permeability of the sample gradually recovered, and the growth rate of the permeability was approximately 78%. However, during these two processes, the porosity of the sample did not change significantly, and its variation range was roughly around 10%.

As shown in the final results after pressurization in

Figure 10,

Figure 11, and

Figure 12, the porosity of each sample showed a decreasing phenomenon. The sample with the lowest decrease amplitude was 4.51%, and the highest reached 56.65%, with an average value of about 16.03%. The decreased amplitude of the permeability was more obvious. The sample with the lowest decrease amplitude was 35.93%, and the highest reached 98.27%, with an average value of about 81.22%. Secondly, we can find that the decreased amplitude of the permeability is related to the shale content in the sandstone. The higher the shale content, the greater the decreased amplitude of the permeability.

During the depressurization process, the porosity of each sample also showed an increasing phenomenon. The lowest increase amplitude was 3.66%, the highest reached 56.82%, and its average value was about 13.88. The lowest increase amplitude of the permeability was 31.79%, the highest was 1520%, and its average value was about 271.06%.

4.6. Experiment on the Changes in Permeability of Sandstone Samples before and After Fracturing and on the Changes in Permeability during Pressurization and Depressurization after Fracturing

Figure 13 shows the permeability data of sandstone samples before and after fracturing. It can be seen from the figure that the permeability of sandstone has been improved to a certain extent after fracturing. The average ratio of the permeability after fracturing to that before fracturing is above 1, and at its highest, the ratio of the permeability before and after fracturing even reaches 178.57.

The above sample data indicate that the fractures in sandstone have a certain improving effect on the permeability of sandstone. The experiment further illustrates that sandstone and the fractures it generates can serve as a migration system to constrain the migration of oil and gas.

As illustrated in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, analogous to the observations made in the mudstone samples, the subsequent pressurization and depressurization experiments on fractured sandstone samples revealed a notable decline in permeability in some samples, whereas, in other samples, permeability exhibited a marked increase under either pressurization or depressurization. Additionally, some samples demonstrated minimal alterations in permeability.

According to the experimental results shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, the experiment has proved that it is similar to the nature of fractures in mudstone samples. Under the pressurization condition where the pressure is parallel to the fractures, the fracture permeability increases with the increase in pressure, and during the depressurization process, the permeability increases further and is greater than the permeability in the initial state. However, under the pressurization condition where the pressure is perpendicular to the fractures, the fracture permeability decreases rapidly with the increase in pressure, and during the depressurization process, the permeability gradually recovers but is also less than the permeability in the initial state. To sum up the above experiments, this shows that when the fractured sandstone is further buried or uplifted, the change in its permeability is also related to the direction and number of fractures it generates.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of the Differences in Conduction Performance of Porous Mudstone

It can be known from the analysis of the porosity measurement results that the connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of porous mudstone is better than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. According to the results of the permeability measurement experiment, the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of porous mudstone is much higher than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. From the above analysis, it can be seen that in porous mudstone samples, there is an obvious correlation between the permeability in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the bedding plane and the pore structure of the rock. In the direction with high permeability, the connectivity of the pore structure is better (

Figure 16).

In summary, for porous mudstone samples, the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is greater than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. The pore connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is good, while that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is poor.

5.2. Analysis of the Differences in Conduction Performance of Fractured Mudstone (Coal)

Through microscopic observation of cast thin sections, micro-fractures are developed in the directions parallel to the bedding plane of full-diameter mudstone and coal rocks, and the connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is better than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. According to the experimental results, the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of full-diameter mudstone and coal rocks is higher than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, and the permeability of fractured mudstone samples is also much greater than that of porous mudstone samples. In fractured mudstone and coal rock samples, there is an obvious correlation between the rock permeability and its pore structure. In the direction with high permeability, the connectivity of the pore structure is better (

Figure 17).

In summary, for fractured mudstone (coal) samples, the permeability is the highest along the fracture direction, followed by the direction parallel to the bedding plane, and the lowest in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. The connectivity is the best along the fracture direction, the pore connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane comes second, and the connectivity in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is relatively poor (

Figure 18).

5.3. Analysis of the Differences in Conduction Performance of Porous Sandstone

Through the measurement of conventional permeability and the observation of cast thin sections, the shape of the grains of porous clastic sandstone is determined by the relative sizes of the long axis, intermediate axis, and short axis of the clasts. According to the length ratios of the three axes of the clasts, the clastic grains can be divided into four shapes: spherical, ellipsoidal, oblate, and prolate. When the clastic grains are deposited, the long-axis direction of the grains tends to be parallel to the horizontal direction. As a result, there are more throats per unit area in the horizontal direction, while the number of throats in the vertical direction is relatively small. That is to say, in the direction parallel to the bedding plane, there are more channels through which oil and gas can migrate, while in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, the channels for oil and gas migration are relatively fewer (

Figure 19). This determines that under the same driving force, oil and gas preferentially migrate along the direction parallel to the bedding plane. In addition, intragranular fractures and grain-edge fractures are easily formed in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of porous sandstone. These tiny fractures communicate with the pores and increase the connectivity of the pores. In the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane of porous sandstone, micro-fractures are not developed and the pore connectivity is poor.

It can be seen from the analysis of the experimental results that in porous sandstone samples, there is an obvious correlation between the permeability in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the bedding plane and the pore structure of the rock. In the direction with high permeability, the connectivity of the pore structure is better (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21).

In summary, for porous sandstone samples, the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is always greater than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. The pore connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is good, while that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is poor.

5.4. Analysis of the Differences in Conduction Performance of Fractured Sandstone

It can be known through microscopic observation of cast thin sections that for samples containing fractures, the fractures are mainly flat and have uneven apertures, and the connectivity of the pore structure is the best along the fracture direction. In sandstone samples with developed fractures, whether it is fractures parallel to the bedding plane or nearly perpendicular fractures that are developed, the permeability of the sandstone is the highest along the fracture direction, followed by the direction parallel to the bedding plane, and the permeability in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is the lowest. Moreover, the coarser the grain size of the sandstone is, the higher the permeability will be. From the above analysis, it can be seen that there is an obvious correlation between the permeability of the sandstone in the directions along the fracture, parallel to the bedding plane and perpendicular to the bedding plane, and the pore structure of the rock. In the direction with high permeability, the connectivity of the pore structure is better (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21).

In summary, for fractured sandstone samples, the seepage ability is the strongest along the fracture direction, followed by the direction parallel to the bedding plane, and the weakest in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. The connectivity is the best along the fracture direction, the pore connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane comes second, and the connectivity in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is relatively poor.

6. Conclusions

(1) In hydrocarbon source rock strata: The permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of porous mudstone is generally greater than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, and the connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is also better than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. When fractures are developed, the permeability and connectivity in the fracture direction of argillaceous rocks (coal) are the best, followed by the direction parallel to the bedding plane, and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is the worst.

(2) In sandstone reservoirs: The permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane of porous sandstone is generally greater than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane, and the connectivity in the direction parallel to the bedding plane is also better than that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. When fractures are developed, the permeability and connectivity in the fracture direction of sandstone are the best, followed by the direction parallel to the bedding plane, and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane is the worst.

(3) When comparing the two: The permeability of porous sandstone is generally greater than that of mudstone, and the connectivity of porous sandstone is also better than that of mudstone. When fractures are developed, the permeability and connectivity in the fracture direction are the best, followed by sandstone, and mudstone is the worst.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G. and J.Z.; methodology, Q.G.; software, Q.G.; validation, Q.G. and J.Z.; formal analysis, Q.G.; investigation, Q.G.; data curation, Q.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by The “14th Five Year Plan” Prospective Basic Science and Technology Project, China National Petroleum Corporation (Grant Nos. 2021DJ2101).

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their professional review work, constructive comments, and valuable suggestions on our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fu, G. and Meng, Q. (2004) ‘Migration translocation system and its control over reservoir forming and distribution of natural gas in deep strata of Xujiaweizi region’, Petroleum Geology and Recovery Efficiency, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 18-20.

- Guo, Q., Li, S. and Jin, Z. (2023) ‘Characteristics and exploration targets of Chang 7 shale oil in Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China’, Petroleum Exploration and Development, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 878-893. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D., Wei, Z. and Liu, R. (2022) ‘Enrichment control factors and exploration potential of lacustrine shale oil and gas: A case study of Jurassic in the Fuling area of the Sichuan Basin’, Natural Gas Industry B, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J., Yi, W. and Qiu, N. (2016) ‘Oil and gas transport system and transport and gathering mode in the long 8 sections of the extension group of the Honghe Oilfield’, Oil and Gas Geology and Recovery, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 9-15.

- Jiang, F., Hu, M. and Hu, T. (2023) ‘Controlling factors and models of shale oil enrichment in Lower Permian Fengcheng Formation, Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, NW China’, Petroleum Exploration and Development, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 812-825. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z., Zhang, J. and Tang, X. (2022) ‘Unconventional natural gas accumulation system’, Natural Gas Industry B, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Ju, J. (2022) ‘Characteristics of the oil and gas transport system in the submarine hills of the western depression of the Liaohe depression’, Special Oil & Gas Reservoirs, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 55-61.

- Li, Y., Xu, K. and Yan, S. (2015) ‘Study on hydrocarbon carrier system in petroliferous basins’, Petroleum Geology and Recovery Efficiency, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 32-36.

- Liu, C., Chen, S. and Zhao, J. (2021) ‘Hydrocarbon transportation system and accumulation simulation of Mesozoic-Cenozoic in the south slope of Kuqa foreland basin’, Natural Gas Geoscience, Vol. 32, No. 10, pp. 1450-1462. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Zhao, S. and Liang, S. (2021) ‘Hydrocarbon transportation system and reservoir forming model of Es3 in slope belt of Chezhen Depression’, Journal of China University of Petroleum (Edition of Natural Sciences), Vol. 45, No. 5, pp. 42-53.

- Liu, Y. (2022) Study on the reservoir transport system and cap features of the Mesozoic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin. Master’s thesis, Northwest University.

- Liu, Z. (2010) Study on the gas transport system in the upper Palaeozoic of the Ordos Basin. Master’s thesis, Northwest University.

- Shi, X., Wu, W. and Wu, Q. (2022) ‘Controlling factors and forming types of deep shale gas enrichment in Sichuan Basin, China’, Energies, Vol. 15, No. 19, pp. 7023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Pang, X. and Chen, Z. (2021) ‘Quantitative evaluation of transport efficiency of fault-reservoir composite migration pathway systems in carbonate petroliferous basins’, Energy, Vol. 222, No. 1, pp. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Liu, L. and Ji, H. (2019) ‘Structure of a pre-Triassic unconformity and its hydrocarbon transporting characteristics, Wuerhe-Fengnan area, Junggar Basin, China’, Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Vol. 173, pp. 820-834. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. and Zhang, J. (2018) ‘Geochemical characteristics and identification criteria of effective source rock in Mesozoic Yanchang Formation, southern margin of Ordos Basin’, International Journal of Oil Gas and Coal Technology, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 379-395. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Hao, F. and Xu, C. (2019) ‘Hydrocarbon migration and accumulation in the northwestern Bozhong subbasin, BohaiBay Basin, China’, Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Vol. 172, pp. 477-488. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., Zheng, R. and Zhao, Y. (2015) ‘New understanding of petroleum migration and accumulation law in Kendong Area, Jiyang Depression’, Petroleum Geology and Recovery Efficiency, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 10-15.

- Zeng, X., Li, J. and Tian, J. (2018) ‘Physical simulation experimental study on the gas accumulation in the late tectonic belts of the northern border of Qaidam Basin’, Natural Gas Geoscience, Vol. 29, No. 9, pp. 1301-1309. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. and Zhao, X. (2023) ‘Hydrocarbon migration pathways and its control on the accumulation in Chengbei fault zone of Qikou Sag, Bohai Bay Basin, East China’, Earth Science, Vol. 48, No. 8, pp. 3053-3067.

- Zhang, H., Wang, X. and Jia, C. (2023) ‘Whole petroleum system and hydrocarbon accumulation model in shallow and medium strata in northern Songliao Basin, NE China’, Petroleum Exploration and Development, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 784-797. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Shi, M. and Wang, D. (2022) ‘Fields and directions for shale gas exploration in China’, Natural Gas Industry B, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 20-32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Zhang, Z. and Jiang, S. (2022) ‘Geological characteristics and enrichment model of Permian Mao 1 Member shale gas reservoirs in Nanchuan area’, Natural Gas Industry B, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 96-105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Jiang, Y. and Hou, S. (2023) ‘Characteristics of Paleoproterozoic oil and gas transport system in northeast Kentucky’, Special Reservoirs, Vol. 30, No. 6, pp. 31-39.

- Zhang, Z., Wang, H. and Yang, H. (2000) ‘Study on passage system of petroliferous basins’, Oil & Gas Geology, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 133-135.

- Zhou, X., Wang, D. and Yu, H. (2022) ‘Major controlling factors and hydrocarbon accumulation models of large-scale lithologic reservoirs in shallow strata around the Bozhong sag, Bohai Bay Basin, China’, Petroleum Exploration and Development, Vol. 49, No. 4, pp. 758-769. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Zhang, H., Guo, H., Zhao, W., Wang, Y., Shi, S., ... & Liu, J. (2024). The impact of marine influence on the hydrocarbon generation potential and process of Upper Paleozoic coal in the eastern Ordos Basin, China: implications for unconventional gas exploration of coal measures. Energy & Fuels, 38(14), 12700-12717. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Kong, Q., Wang, H., Zhang, H., Guo, H., Wang, Y., ... & Peng, P. A. (2024). Generation Potential and Kinetics of Gaseous Hydrocarbons from Upper Paleozoic Carboniferous Benxi Formation Mudstone in Ordos Basin, China. ACS omega, 9(37), 39088-39099. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F., Qu, C., Cao, G., Xie, L., Shi, X., Luo, S., ... & Wang, Z. (2024). Oolitic Sedimentary Characteristics of the Upper Paleozoic Bauxite Series in the Eastern Ordos Basin and Its Significance for Oil and Gas Reservoirs. Processes, 12(10), 2123. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Qin, Y., Zhang, G., Shen, J., Yu, J., Ji, X., ... & Qin, Y. (2024). Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Upper Paleozoic Coal in the Renjiazhuang Mining District, Northwest Ordos Basin, China: Evidence for Sediment Sources, Depositional Environment, and Elemental Occurrence. Minerals, 14(10), 1045. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Fu, H., Yan, D., & Wang, X. (2024). The constraints of the sedimentary environment on the evolution of bauxite reservoir characteristics within the benxi formation in the Linxing area, Ordos Basin, China. Energy Science & Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X. M., Zhao, B. Q., Thu, Z. L., Song, Z. G., & Wilkins, R. W. T. (2005). Upper Paleozoic petroleum system, Ordos Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 22(8), 945-963. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., Sun, Z., Luo, D., Ding, Y., Liu, W., & Yang, D. (2022). Critical review on microscopic rock characteristics and flow behaviour differences for tight sandstone reservoirs in Ordos Basin, China. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 218, 110669. [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y., Jinhua, F., Xinshe, L., & Peilong, M. (2012). Accumulation conditions and exploration and development of tight gas in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin. Petroleum Exploration and Development, 39(3), 315-324. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Li, J., Li, Z., Wang, D., Gong, S., Zhang, Y., ... & Sun, Q. (2014). The hydrogen isotopic characteristics of the Upper Paleozoic natural gas in Ordos Basin. Organic geochemistry, 74, 66-75. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., Sun, L., Luo, J., ... & Gao, S. (2024). Multi-scale fracture patterns and their effects on gas enrichment in tight sandstones: a case study of the Upper Paleozoic in the Qingshimao gas field, Ordos Basin, China. Frontiers in Earth Science, 12, 1448238. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Lithological stratigraphic column chart of the Upper Paleozoic in Ordos Basin.

Figure 1.

Lithological stratigraphic column chart of the Upper Paleozoic in Ordos Basin.

Figure 4.

The variation law of permeability of mudstone samples under two conditions.

Figure 4.

The variation law of permeability of mudstone samples under two conditions.

Figure 5.

The variation law of permeability of mudstone samples under two conditions (pressurization on the left and depressurization on the right).

Figure 5.

The variation law of permeability of mudstone samples under two conditions (pressurization on the left and depressurization on the right).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the average values of the reduction and increase ranges of permeability for mudstone samples.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the average values of the reduction and increase ranges of permeability for mudstone samples.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the permeability of mudstone samples before and after rupture.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the permeability of mudstone samples before and after rupture.

Figure 9.

The variation in porosity and permeability of sandstone under different conditions.

Figure 9.

The variation in porosity and permeability of sandstone under different conditions.

Figure 10.

The reduction amplitudes of the two kinds of data under the pressurization condition of the samples.

Figure 10.

The reduction amplitudes of the two kinds of data under the pressurization condition of the samples.

Figure 11.

The increased amplitudes of the two kinds of data under the depressurization condition of the samples.

Figure 11.

The increased amplitudes of the two kinds of data under the depressurization condition of the samples.

Figure 12.

The comparison chart of the average values of the variation amplitudes of porosity and permeability of sandstone samples.

Figure 12.

The comparison chart of the average values of the variation amplitudes of porosity and permeability of sandstone samples.

Figure 13.

The comparison chart of the permeability of sandstone before and after fracturing.

Figure 13.

The comparison chart of the permeability of sandstone before and after fracturing.

Figure 14.

The diagram of permeability changes of parallel bedding plane fractures in sandstone samples under different stress conditions.

Figure 14.

The diagram of permeability changes of parallel bedding plane fractures in sandstone samples under different stress conditions.

Figure 15.

The diagram of permeability changes of fractures perpendicular to the bedding plane in sandstone samples under different stress conditions.

Figure 15.

The diagram of permeability changes of fractures perpendicular to the bedding plane in sandstone samples under different stress conditions.

Figure 16.

Comparison chart of the permeability of porous mudstone (Su117, E3N3Q,3577.15m, Box 8 above, dark pink sandy mudstone).

Figure 16.

Comparison chart of the permeability of porous mudstone (Su117, E3N3Q,3577.15m, Box 8 above, dark pink sandy mudstone).

Figure 17.

Comparison chart of the permeability of full-diameter mudstone (Su 116, E2N1Q, 3595.50m, dark pink sandy mudstone of Shanxi Formation).

Figure 17.

Comparison chart of the permeability of full-diameter mudstone (Su 116, E2N1Q, 3595.50m, dark pink sandy mudstone of Shanxi Formation).

Figure 18.

Comparison chart of the permeability and pore structure of full-diameter coal rock.

Figure 18.

Comparison chart of the permeability and pore structure of full-diameter coal rock.

Figure 19.

Comparison of the number of pore throats in the direction parallel to the bedding plane and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane.

Figure 19.

Comparison of the number of pore throats in the direction parallel to the bedding plane and the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane.

Figure 20.

Comparison chart of the permeability and pore structure in the directions parallel to the bedding plane, perpendicular to the bedding plane, and along the bedding plane fractures of sandstone samples.

Figure 20.

Comparison chart of the permeability and pore structure in the directions parallel to the bedding plane, perpendicular to the bedding plane, and along the bedding plane fractures of sandstone samples.

Figure 21.

Comparison chart of the permeability and pore structure in the directions parallel to the bedding plane, perpendicular to the bedding plane, and along the nearly perpendicular fractures of sandstone samples.

Figure 21.

Comparison chart of the permeability and pore structure in the directions parallel to the bedding plane, perpendicular to the bedding plane, and along the nearly perpendicular fractures of sandstone samples.

Table 1.

Comparison between the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane and that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane for mudstone samples.

Table 1.

Comparison between the permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane and that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane for mudstone samples.

| Well Number |

Depth

m |

Lithology |

Permeability number

H - Direction parallel to the bedding plane

V - Direction perpendicular to the bedding plane |

Porosity

% |

Air Permeability

10-3μm2

|

Average permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane |

Average permeability in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane |

The ratio of the average permeability in the direction parallel to the bedding plane to that in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane |

Annotation |

| Mi 11 |

1666.25 |

Interbedded argillaceous siltstone and silty mudstone |

E13Y1NH1 |

10.2 |

0.0802 |

0.0802 |

|

1.516 |

Sample E13Y1NH2 contains fractures |

| E13Y1NH2 |

9.1 |

130.0 |

| E13Y1NV1 |

10.4 |

0.0440 |

|

0.0529 |

| E13Y1NV2 |

9.9 |

0.0618 |

| Mi 11 |

2046.7 |

Silty mudstone |

E13Y6NH1 |

1.4 |

0.0194 |

0.01915 |

|

1.013 |

|

| E13Y6NH2 |

1.6 |

0.0189 |

| E13Y6NV1 |

0.7 |

0.0216 |

|

0.0189 |

| E13Y6NV2 |

0.8 |

0.0162 |

| Yu 27 |

2727.85 |

Silty mudstone |

E9Y8NH1 |

1.4 |

0.0551 |

0.08155 |

|

3.811 |

|

| E9Y8NH2 |

1.5 |

0.1080 |

| E9Y8NV1 |

2.2 |

0.0223 |

|

0.0214 |

| E9Y8NV2 |

1.1 |

0.0205 |

| mean value |

|

1.34 |

|

0.0603 |

0.03107 |

2.113 |

Samples of the E13Y1N series are excluded |

Table 2.

Comparison between the Permeability in the Direction Parallel to the Bedding Plane and that in the Direction Perpendicular to the Bedding Plane of Sandstone.

Table 2.

Comparison between the Permeability in the Direction Parallel to the Bedding Plane and that in the Direction Perpendicular to the Bedding Plane of Sandstone.

Well

Number |

Depth(m) |

Lithology |

Serial Number |

Horizon |

Porosity(%) |

Air Permeability(10-3μm2) |

The average value of permeability parallel to the bedding plane

(10-3μm2) |

The average value of permeability perpendicular to the bedding plane

(10-3μm2) |

The ratio of the average value of horizontal permeability to that of vertical permeability |

| Well Shan 256 |

3221.2 |

fine sandstone |

E8Y15SH1 |

He 7 |

1.3 |

0.0486 |

0.0489 |

|

1.38 |

| E8Y15SH2 |

1.3 |

0.0492 |

| E8Y15SV1 |

1.9 |

0.0391 |

|

0.0354 |

| E8Y15SV2 |

2.4 |

0.0317 |

| Well Shan 211 |

2851.55 |

medium sandstone |

E6Y10SH1 |

Lower He 8 |

7.3 |

0.182 |

0.182 |

|

2.53 |

| E6Y10SH2 |

7.7 |

0.181 |

| E6Y10SV1 |

5.2 |

0.072 |

|

0.072 |

| E6Y10SV2 |

6.1 |

0.073 |

| Well Mi 11 |

2041.7 |

coarse sandstone |

E13Y5SH1 |

Shan 1 |

9.8 |

4.540 |

3.845 |

|

2.80 |

| E13Y5SH2 |

10.2 |

3.150 |

| E13Y5SV1 |

10.3 |

1.170 |

|

1.375 |

| E13Y5SV2 |

9.7 |

1.580 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).