Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

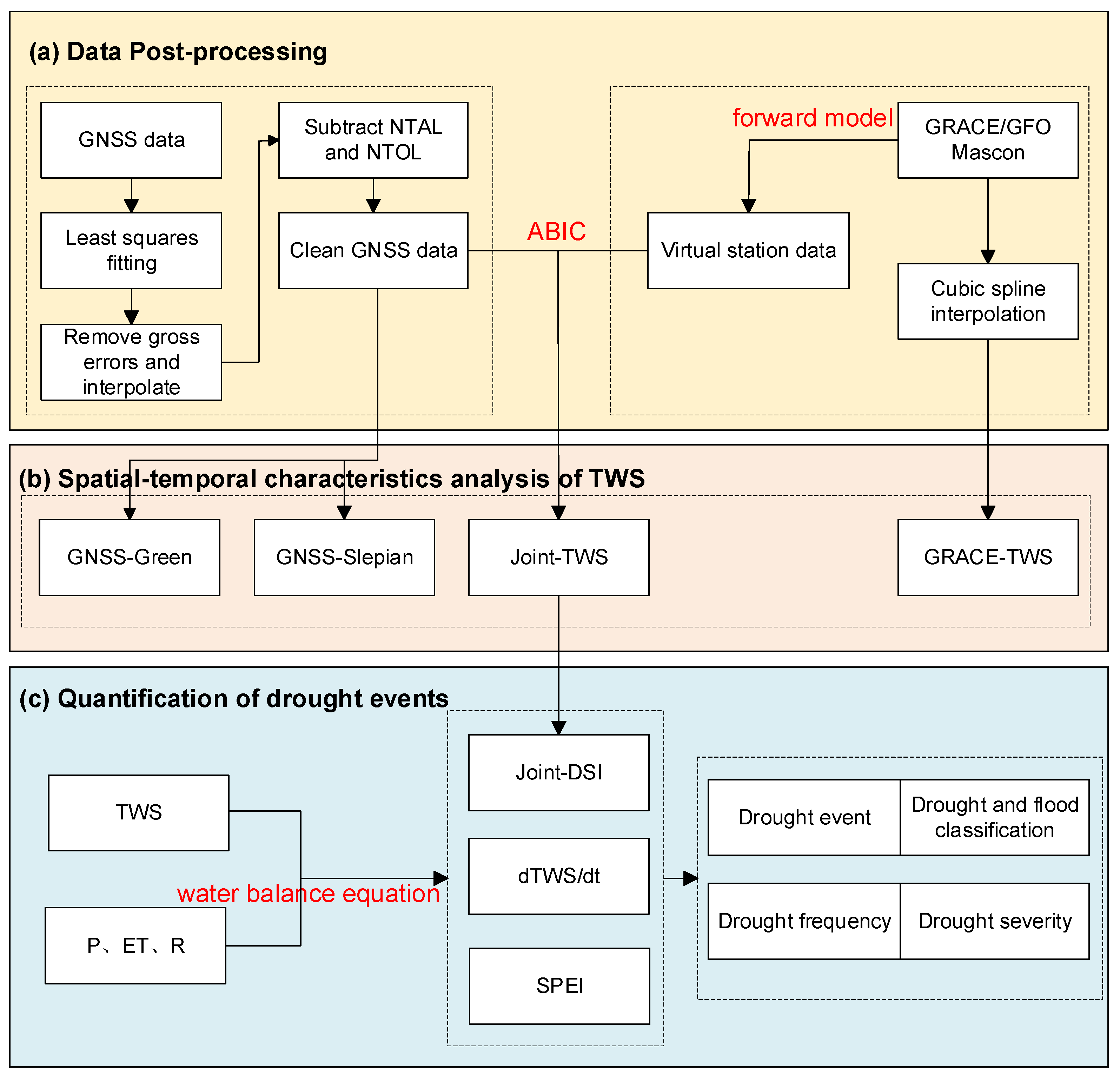

2. Data and methodology

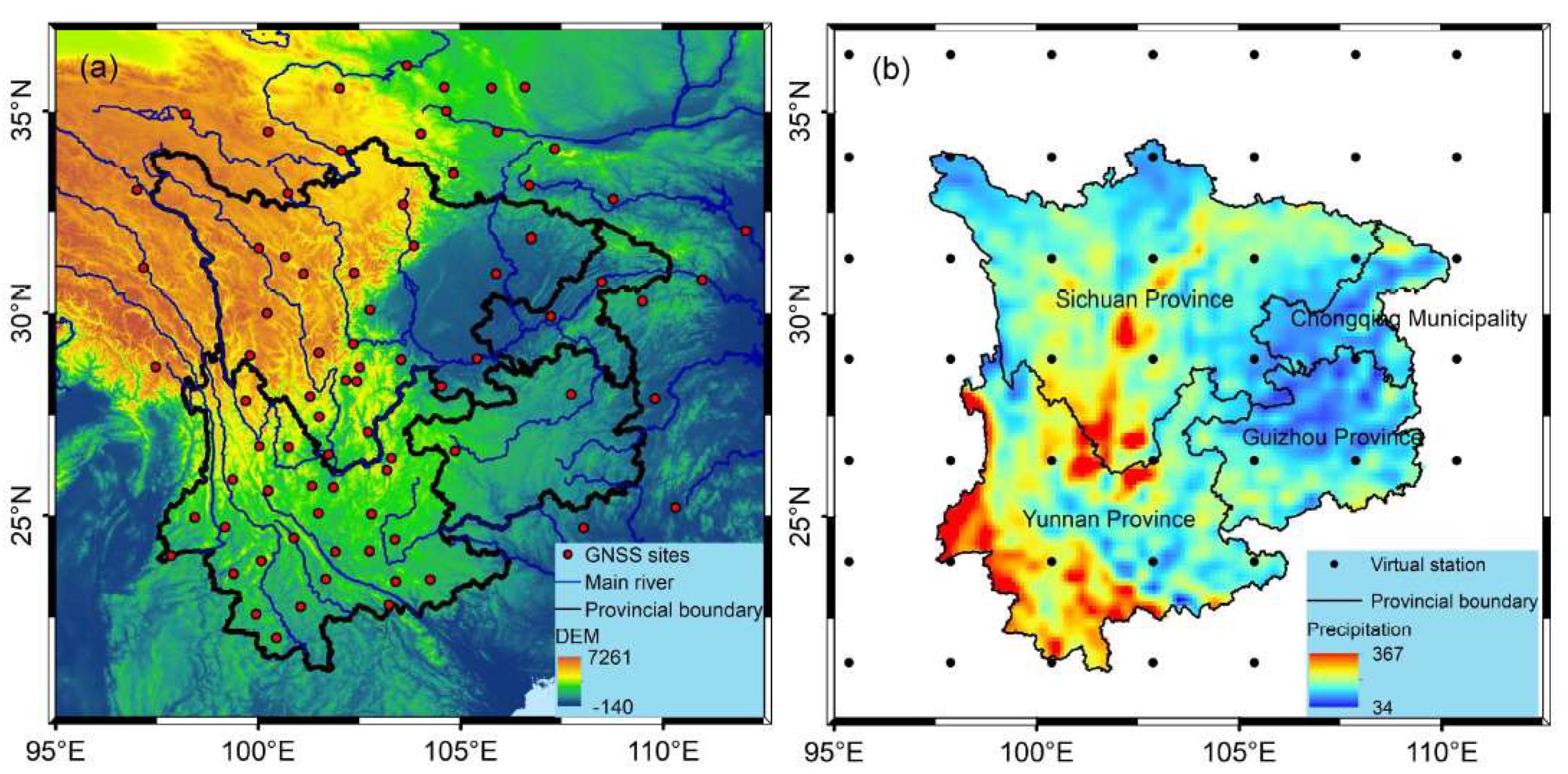

2.1. Study area

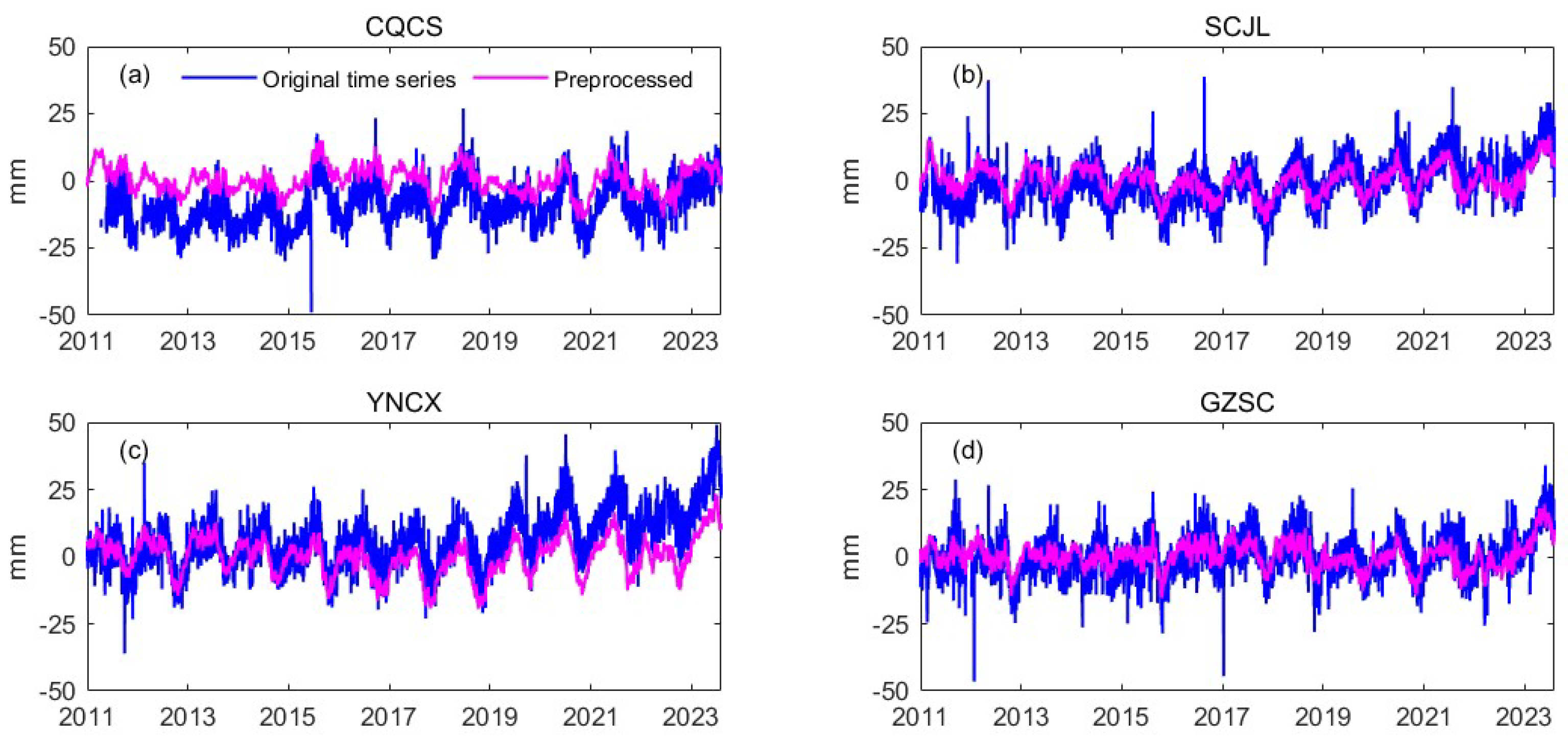

2.2. GNSS vertical displacement time series

2.3. GRACE/GFO Mascon solutions

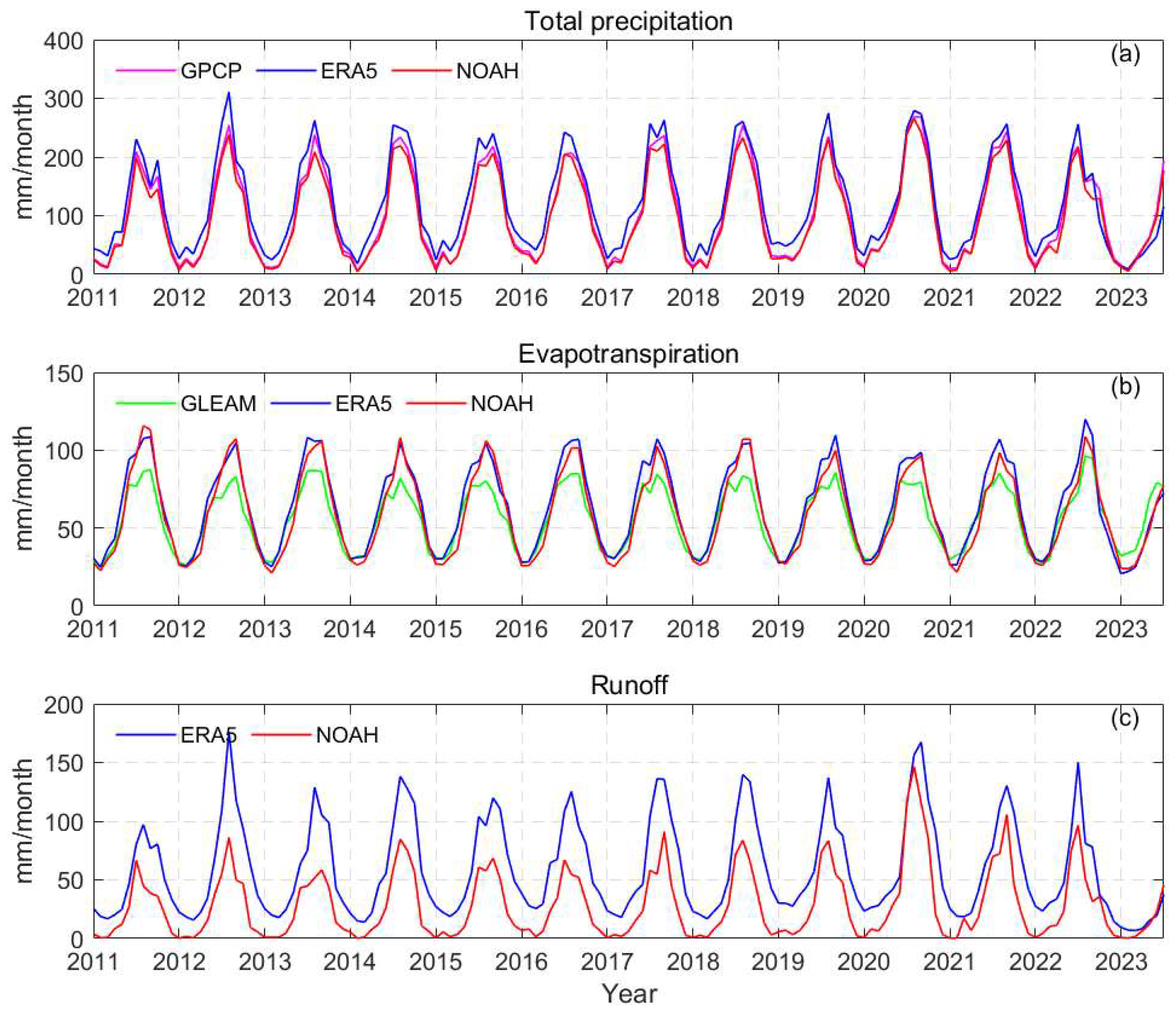

2.4. Hydrometeorological data

3. Methodology

3.1. Green’s function

3.2. Slepian basis function

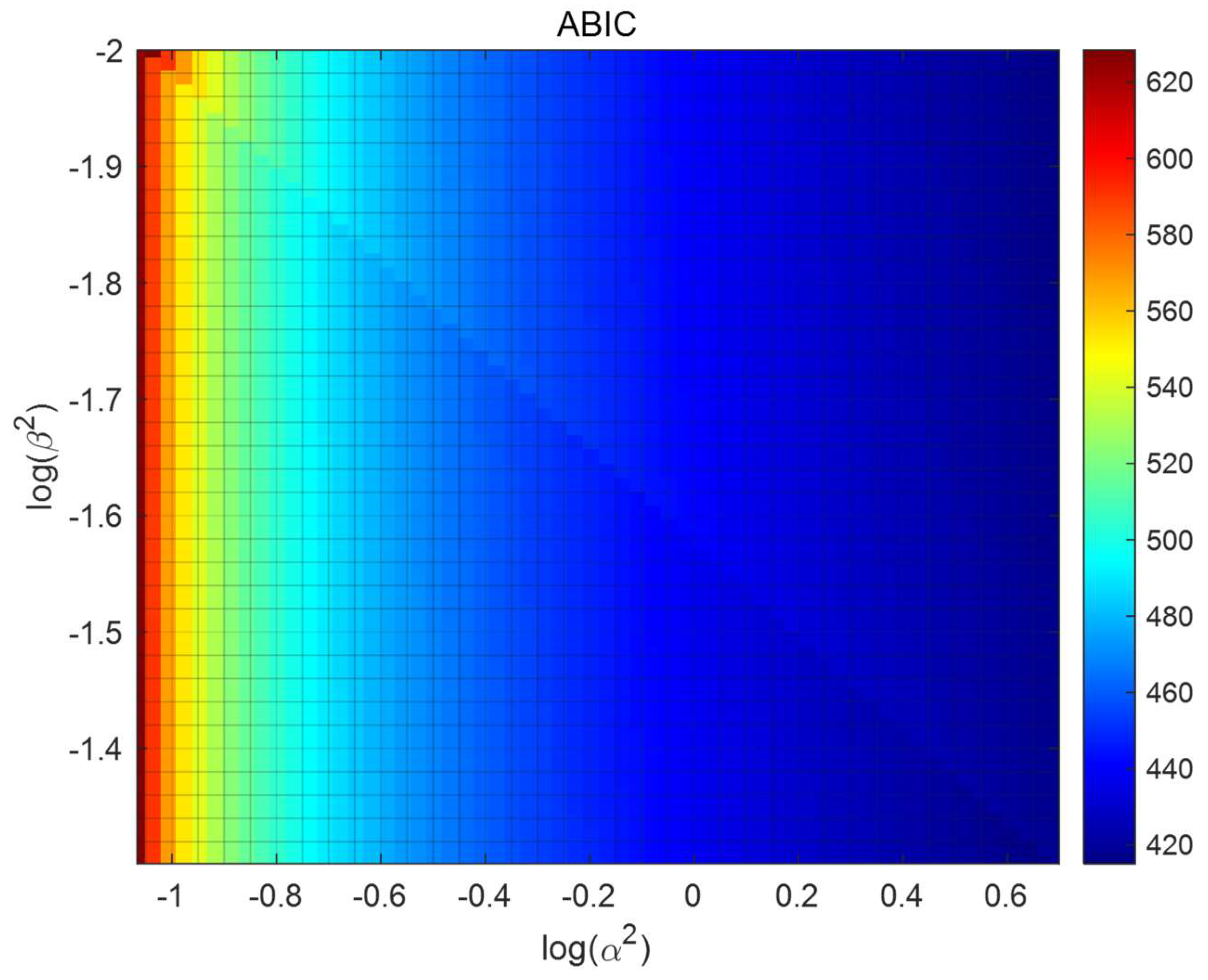

3.3. Joint inversion

3.4. Drought index

4. Result

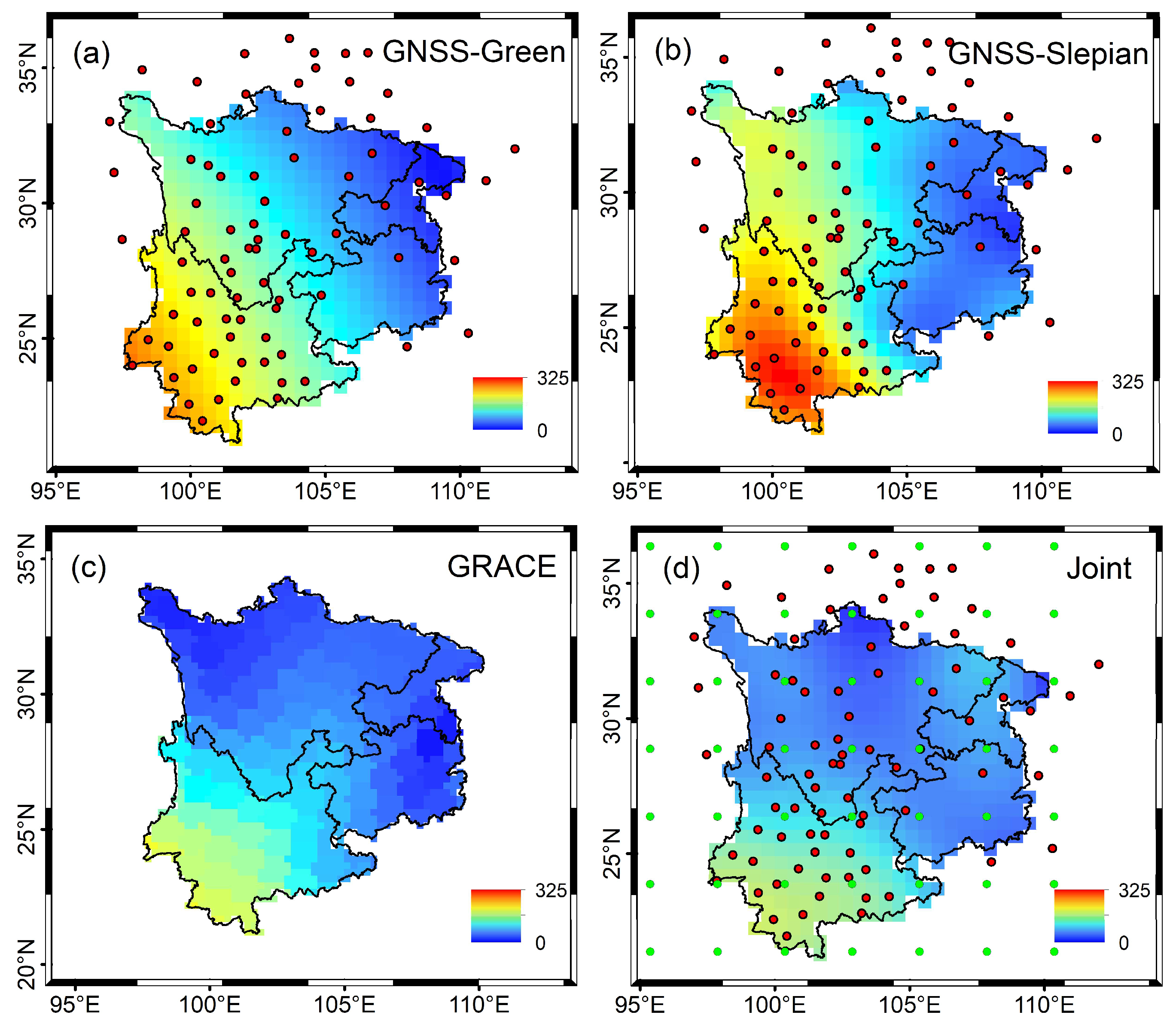

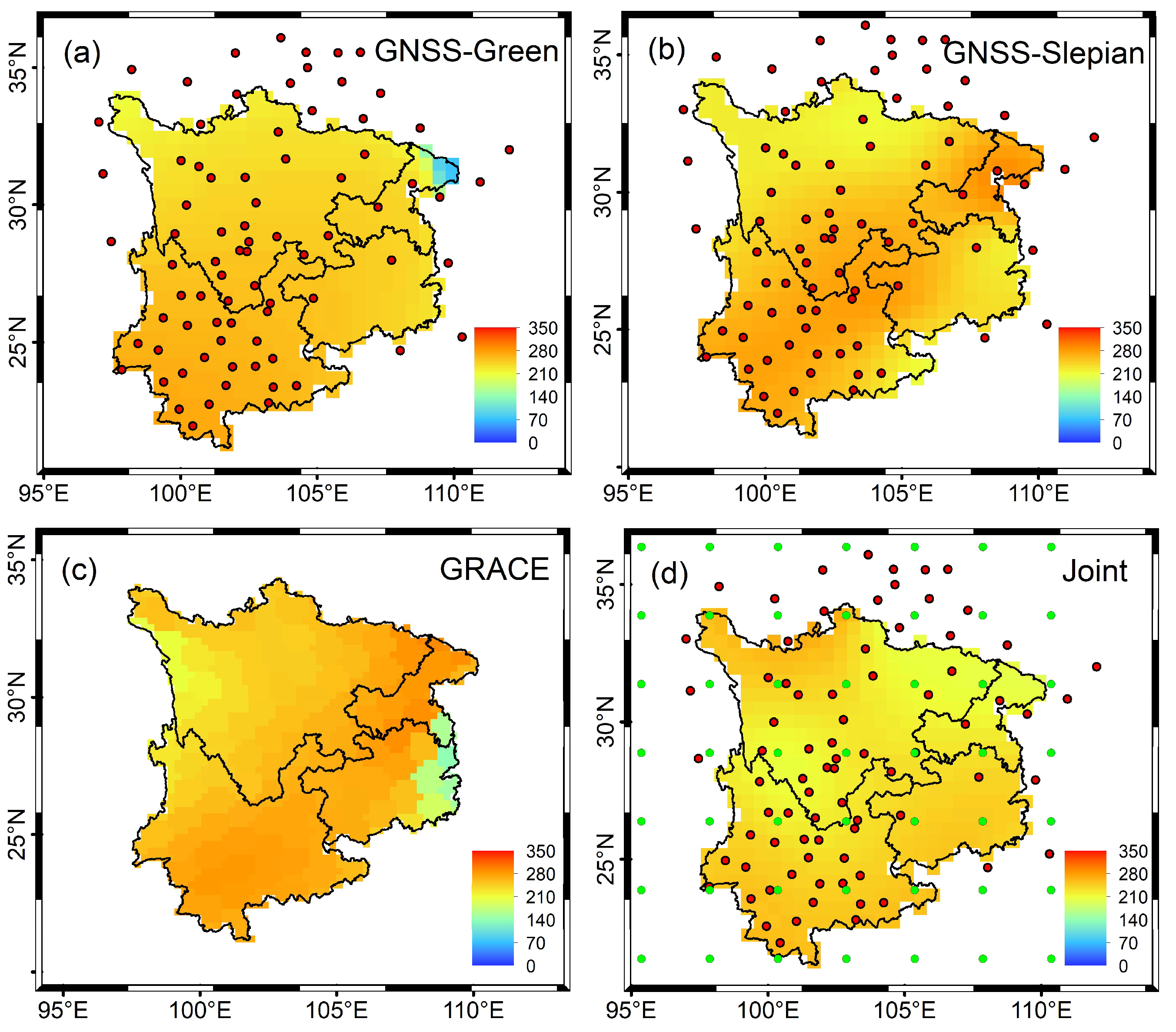

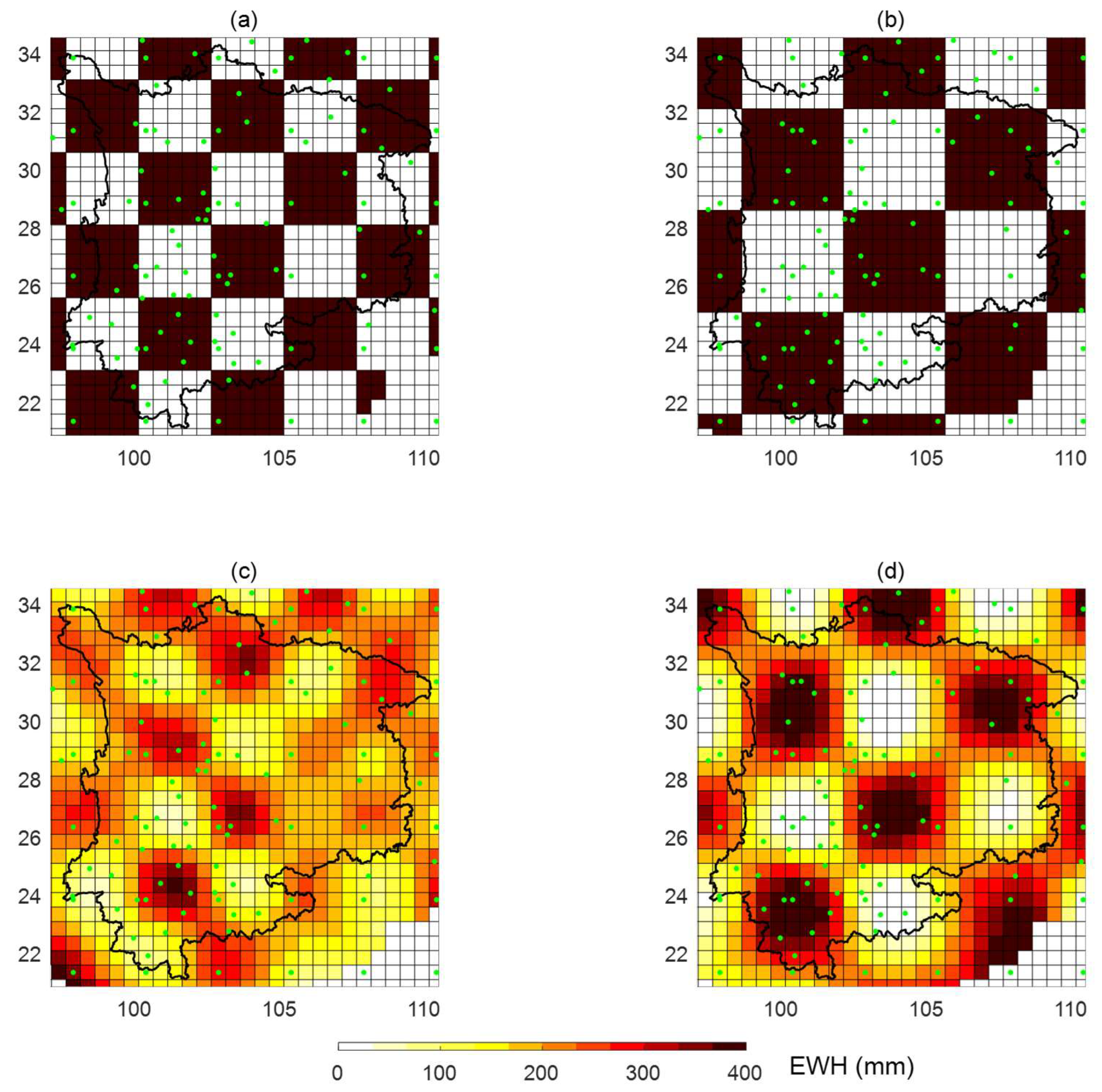

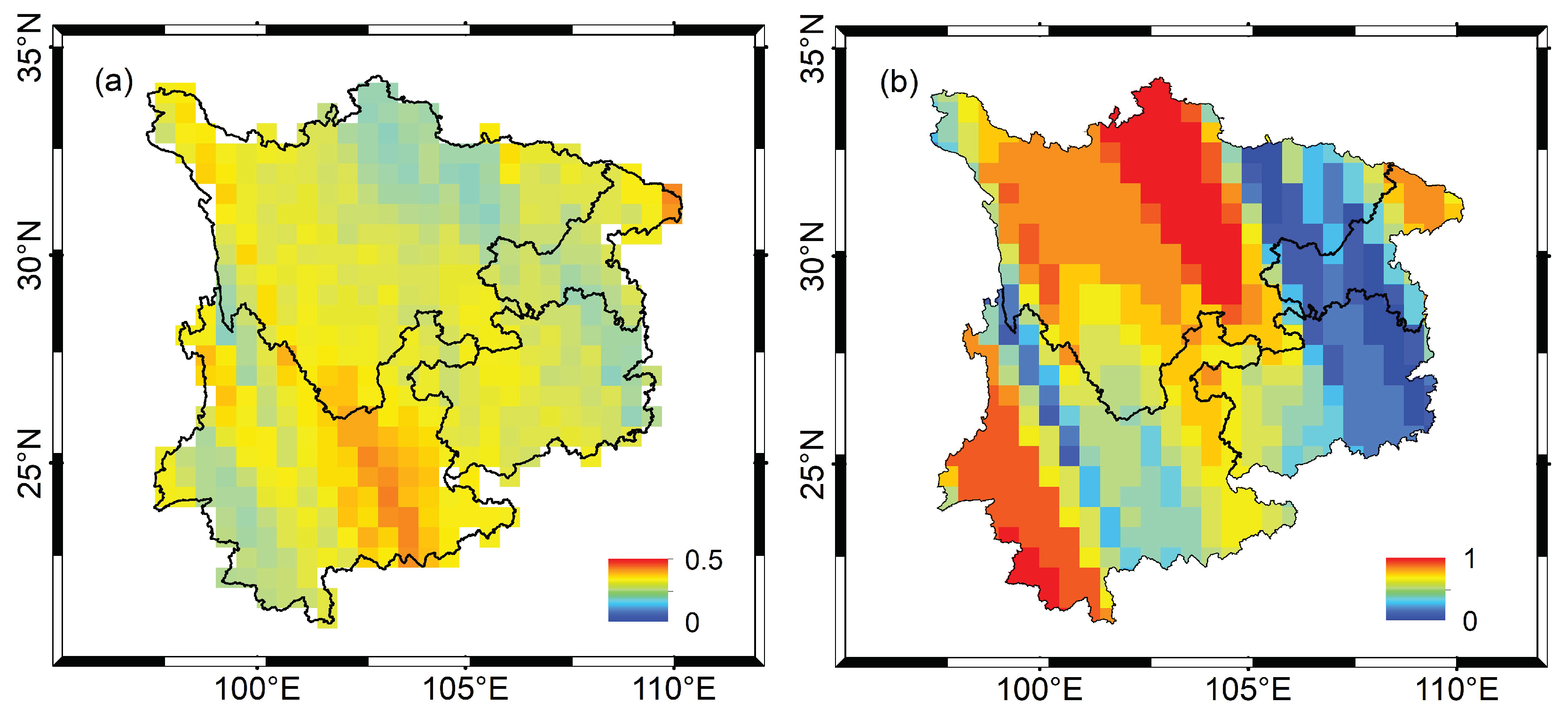

4.1. Spatial distribution characteristics of TWS

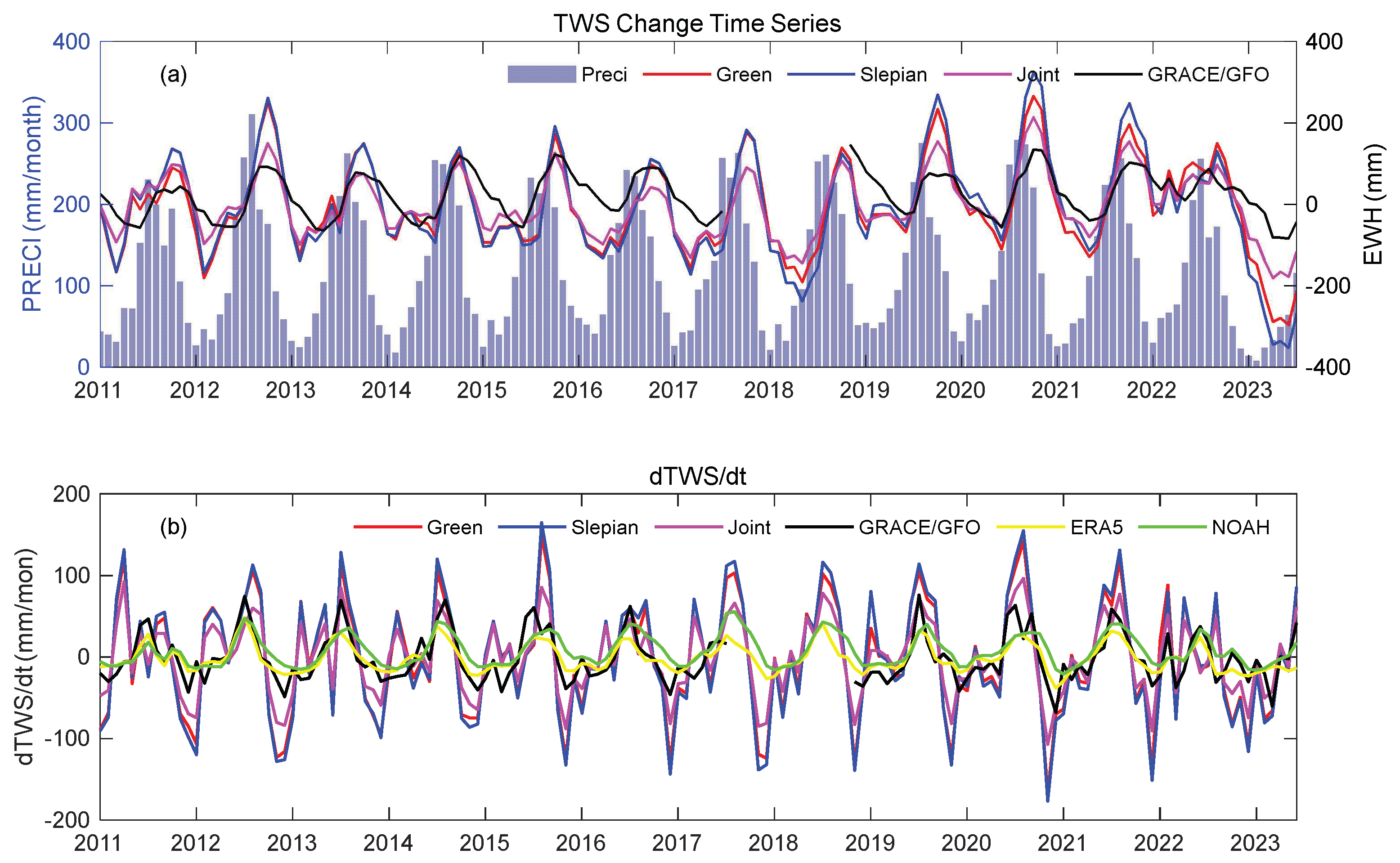

4.2. Temporal distribution characteristics of TWS

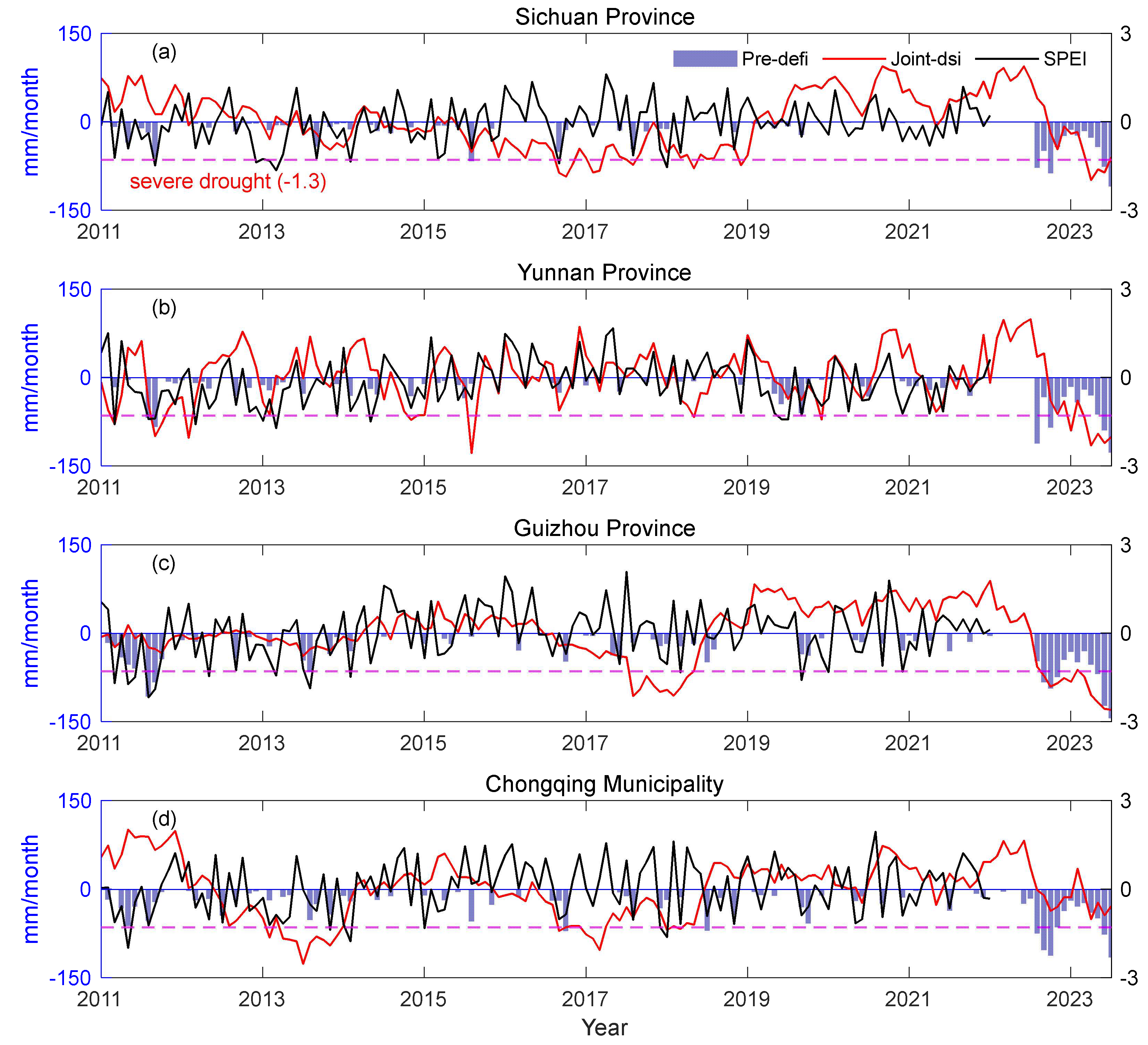

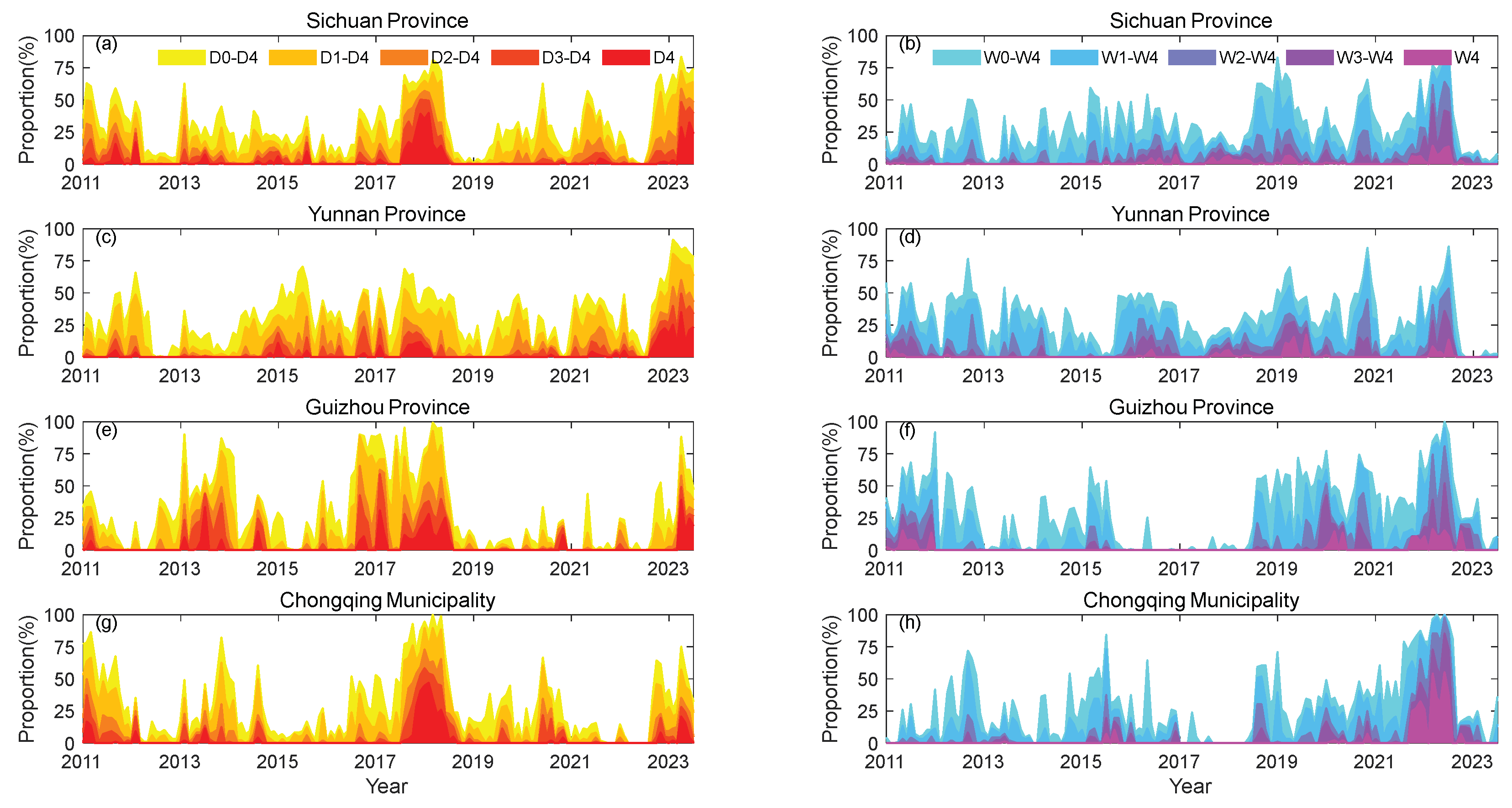

4.3. GNSS-based drought index

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial resolution of joint inversion

5.2. Quantification of drought characteristics in Southwest China

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Cheng, Y. Drought area, intensity and frequency changes in China under climate warming, 1961–2014. J. Arid. Environ. 2021, 193, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, G. Ecological Economic Problems and Development Patterns of the Arid Inland River Basin in Northwest China. AMBIO 2006, 35, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Famiglietti, J.S. Detectability of variations in continental water storage from satellite observations of the time dependent gravity field. Water Resour. Res. 1999, 35, 2705–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapley, B.D.; Bettadpur, S.; Ries, J.C.; Thompson, P.F.; Watkins, M.M. GRACE Measurements of Mass Variability in the Earth System. Science 2004, 305, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, S.; Wahr, J. Post-processing removal of correlated errors in GRACE data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Zhang, Z.; Save, H.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Global models underestimate large decadal declining and rising waterstorage trends relative to GRACE satellite data. PANS 2018, 115, E1080–E1089. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, W.E. Deformation of the Earth by surface loads. Rev. Geophys. 1972, 10, 761–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Heflin, M.B.; Ivins, E.R.; Argus, D.F.; Webb, F.H. Large-scale global surface mass variations inferred from GPS measurements of load-induced deformation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahr, J.; Khan, S.A.; van Dam, T.; Liu, L.; van Angelen, J.H.; Broeke, M.R.v.D.; Meertens, C.M. The use of GPS horizontals for loading studies, with applications to northern California and southeast Greenland. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M.; Gardner, W.P.; Borsa, A.A.; Argus, D.F.; Martens, H.R. A Review of GNSS/GPS in Hydrogeodesy: Hydrologic Loading Applications and Their Implications for Water Resource Research. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.C.; Li, X.P.; Zhong, B. Review of Inverting GNSS Surface Deformations for Regional Terrestrial Water Storage Changes. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2023, 48, 1724–1735. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Razeghi, S.M. GPS Recovery of Daily Hydrologic and Atmospheric Mass Variation: A Methodology and Results From the Australian Continent. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9328–9343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argus, D.F.; Fu, Y.; Landerer, F.W. Seasonal variation in total water storage in California inferred from GPS observations of vertical land motion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Argus, D.F.; Landerer, F.W. GPS as an independent measurement to estimate terrestrial water storage variations in Washington and Oregon. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2014, 120, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Hsu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Yang, X.; Ding, Y.; Tang, M.; Chen, C. Characterizing Spatiotemporal Patterns of Terrestrial Water Storage Variations Using GNSS Vertical Data in Sichuan, China. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, B.; Li, J.; Liu, R. Inversion of GNSS Vertical Displacements for Terrestrial Water Storage Changes Using Slepian Basis Functions. Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintori, F.; Serpelloni, E. Drought-Induced Vertical Displacements and Water Loss in the Po River Basin (Northern Italy) From GNSS Measurements. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, J. A novel GNSS and precipitation-based integrated drought characterization framework incorporating both meteorological and hydrological indicators. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2024, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Hu, X. On the Improvement of Mass Load Inversion With GNSS Horizontal Deformation: A Synthetic Study in Central China. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, H.S.; Liu, Y. An Improved GPS-Inferred Seasonal Terrestrial Water Storage Using Terrain-Corrected Vertical Crustal Displacements Constrained by GRACE. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fok, H.S.; Tenzer, R.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X. Akaike's Bayesian Information Criterion for the Joint Inversion of Terrestrial Water Storage Using GPS Vertical Displacements, GRACE and GLDAS in Southwest China. Entropy 2019, 21, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, B.; Li, J.; Liu, R. Joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE/GFO data for terrestrial water storage changes in the Yangtze River Basin. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 233, 1596–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Hu, S.; Wei, G.; Chai, H.; Wang, T. Characterizing hydrological droughts within three watersheds in Yunnan, China from GNSS-inferred terrestrial water storage changes constrained by GRACE data. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 235, 1581–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusumilli, S.; Borsa, A.A.; Fish, M.A.; McMillan, H.K.; Silverii, F. A Decade of Water Storage Changes Across the Contiguous United States from GPS and Satellite Gravity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 13006–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, G.; Werth, S.; Shirzaei, M. Joint Inversion of GNSS and GRACE for Terrestrial Water Storage Change in California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, M.; Feng, X.; Li, C. Investigating terrestrial water storage changes in Southwest China by integrating GNSS and GRACE/GRACE-FO observations. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.K.; Zhao, L.L.; Chen, J.S.; Ren, Y.N.; Li, H.Z. Spatio-temporal Evolution Trend of Meteorological Drought and Identification of Drought Events in Southwest China from 1983 to 2020. Ecol. Env. Sci. 2023, 32, 920–932. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Tang, H.; Qu, S.M.; Wen, T.; Zhao, L.L.; LI, Q.F. Characteristics of propagation from meteorological drought to hydrological drought in Southwest China. Water Resour. Prot. 2023, 39, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Sun, J. Changes in Drought Characteristics over China Using the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 5430–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.L.; Luo, Z.C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.M. Detecting droughts in Southwest China from GPS vertical position displacements. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2019, 48, 547–554. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Yuan, L.; Huang, D. Monitoring time-varying terrestrial water storage changes using daily GNSS measurements in Yunnan, southwest China. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2021, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, B.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Investigation of 2020–2022 extreme floods and droughts in Sichuan Province of China based on joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE/GFO data. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Chen, G.; Chao, N.; Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Luo, X. Detection of extreme hydrological droughts in the poyang lake basin during 2021–2022 using GNSS-derived daily terrestrial water storage anomalies. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 919, 170875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Chai, H.; Ye, Y.; Liu, W. Characterizing extreme drought and wetness in Guangdong, China using global navigation satellite system and precipitation data. Satell. Navig. 2024, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, T.A.; King, R.W.; Floyd, M.A.; McClusky, S.C. Introduction to GAMIT/GLOBK, Release 10.7; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D.; Herring, T.A.; King, R.W. Estimating regional deformation from a combination of space and terrestrial geodetic data. J. Geodesy 1998, 72, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Dai, W.; Santerre, R.; Kuang, C. A MATLAB-based Kriged Kalman Filter software for interpolating missing data in GNSS coordinate time series. GPS Solutions 2017, 22, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H.; Bettadpur, S.; Tapley, B.D. High--resolution CSR GRACE RL05 mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid. Earth 2016, 121, 7547–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, W.K. Progress and prospect of GRACE Mascon product and its application. Rev. Geophys. Planet. Phys. 2022, 53, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-Land hourly data from 1950 to present. opernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodell, M.; Houser, P.R.; Jambor, U.; Gottschalck, J.; Mitchell, K.; Meng, C.-J.; Arsenault, K.; Cosgrove, B.; Radakovich, J.; Bosilovich, M.; et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.F.; Huffman, G.J.; Chang, A.; Ferraro, R.; Xie, P.-P.; Janowiak, J.; Rudolf, B.; Schneider, U.; Curtis, S.; Bolvin, D.; Gruber, A.; Susskind, J.; Arkin, P.; Nelkin, E. The Version-2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Precipitation Analysis (1979–Present). J. Hydrometeorol. 2003, 4, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, D.G.; Holmes, T.R.H.; De Jeu, R.A.M.; Gash, J.H.; Meesters, A.G.C.A.; Dolman, A.J. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tapley, B.; Rodell, M.; Seo, K.W.; Wilson, C.; Scanlon, B.R.; Pokhrel, Y. Basin--Scale River Runoff Estimation from GRACE Gravity Satellites, Climate Models, and In Situ Observations: A Case Study in the Amazon Basin. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR028032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landerer, F.W.; Dickey, J.O.; Güntner, A. Terrestrial water budget of the Eurasian pan-Arctic from GRACE satellite measurements during 2003–2009. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funning, G.J.; Fukahata, Y.; Yagi, Y.; Parsons, B. A method for the joint inversion of geodetic and seismic waveform data using ABIC: Application to the 1997 Manyi, Tibet, earthquake. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 196, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukahata, Y.; Nishitani, A.; Matsu'Ura, M. Geodetic data inversion using ABIC to estimate slip history during one earthquake cycle with viscoelastic slip-response functions. Geophys. J. Int. 2004, 156, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.C.; Reager, J.T.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Rodell, M. A GRACE-based water storage deficit approach for hydrological drought characterization. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zou, R.; Fang, Z.; Cao, J.; Wang, Q. Using geodetic measurements derived terrestrial water storage to investigate the characteristics of drought in Yunnan, China. GPS Solutions 2023, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-J.; Fu, Y.; Bürgmann, R.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-C.; Tang, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-M. Assessing seasonal and interannual water storage variations in Taiwan using geodetic and hydrological data. 2020, 550, 116532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Geruo, A.; Velicogna, I.; Kimball, J.S. Satellite Observations of Regional Drought Severity in the Continental United States Using GRACE-Based Terrestrial Water Storage Changes. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 6297–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.Y.; Dai, L.; Yang, G.B.; Yin, C.Y.; Yang, Q.; Liu, F.; Li, M. Dynamic analysis of spatio-temporal distribution of droughts in karst mountainous regions of Guizhou Province from 1960 to 2016. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2021, 32, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

| GNSS-Green | GNSS-Slepian | Joint-TWS | GRACE-TWS | ERA5 | NOAH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNSS-Green | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| GNSS-Slepian | 0.99 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Joint-TWS | 0.98 | 0.98 | - | - | - | |

| GRACE-TWS | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.69 | - | - | - |

| ERA5 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.79 | - | - |

| NOAH | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.76 | 0.85 | - |

| Occurrence time | Duration (month) | Peak deficit (km3) | Average deficit (km3) | Total severity (km3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013.08-2013.12 | 5 | -50.817(201310) | -32.899 | -164.499 |

| 2014.06-2015.01 | 8 | -22.758(201410) | -13.223 | -105.782 |

| 2015.05-2015.08 | 4 | -56.075(201507) | -23.912 | -95.649 |

| 2016.01-2018.12 | 36 | -111.192(201804) | -39.177 | -1410.370 |

| 2022.09-2023.06 | 10 | -150.694(202305) | -86.133 | -861.332 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).