Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

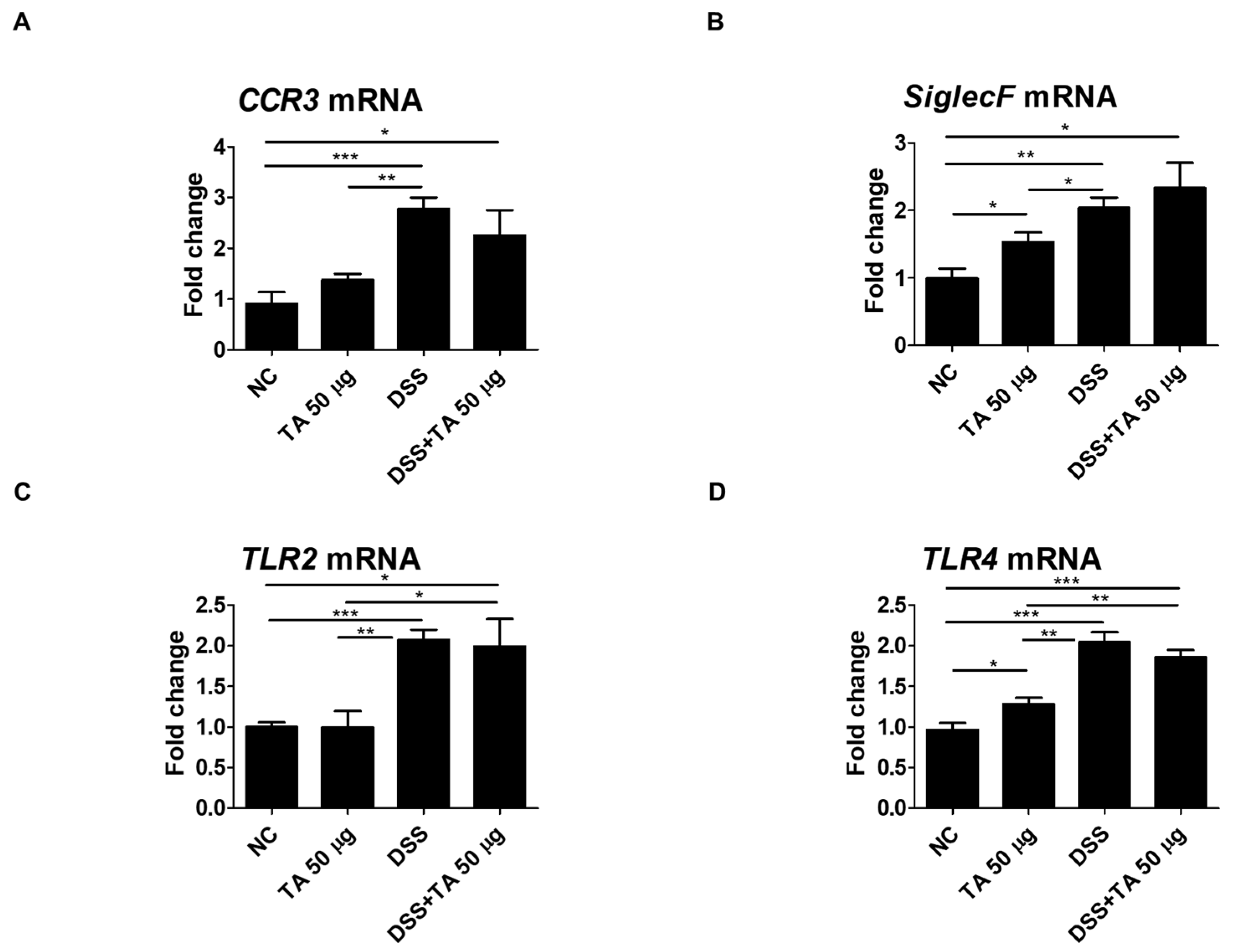

2. Results

2.1. Expression Levels of Eosinophil Activation Markers in PBLs of Normal Mice Treated with Tartaric Acid (TA)

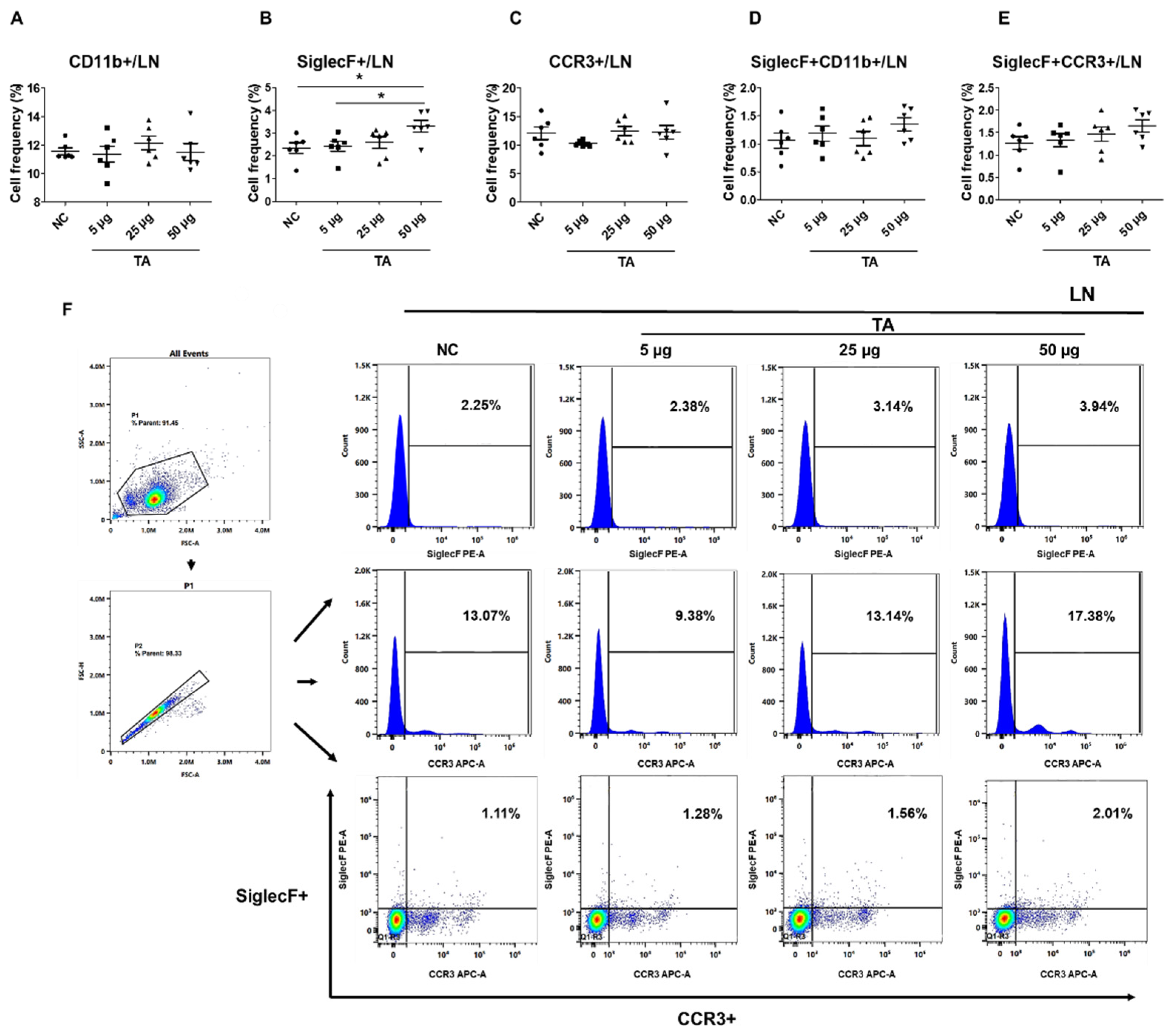

2.2. Increased frequencies of SiglecF+ Cells in LN of TA-Treated Mice

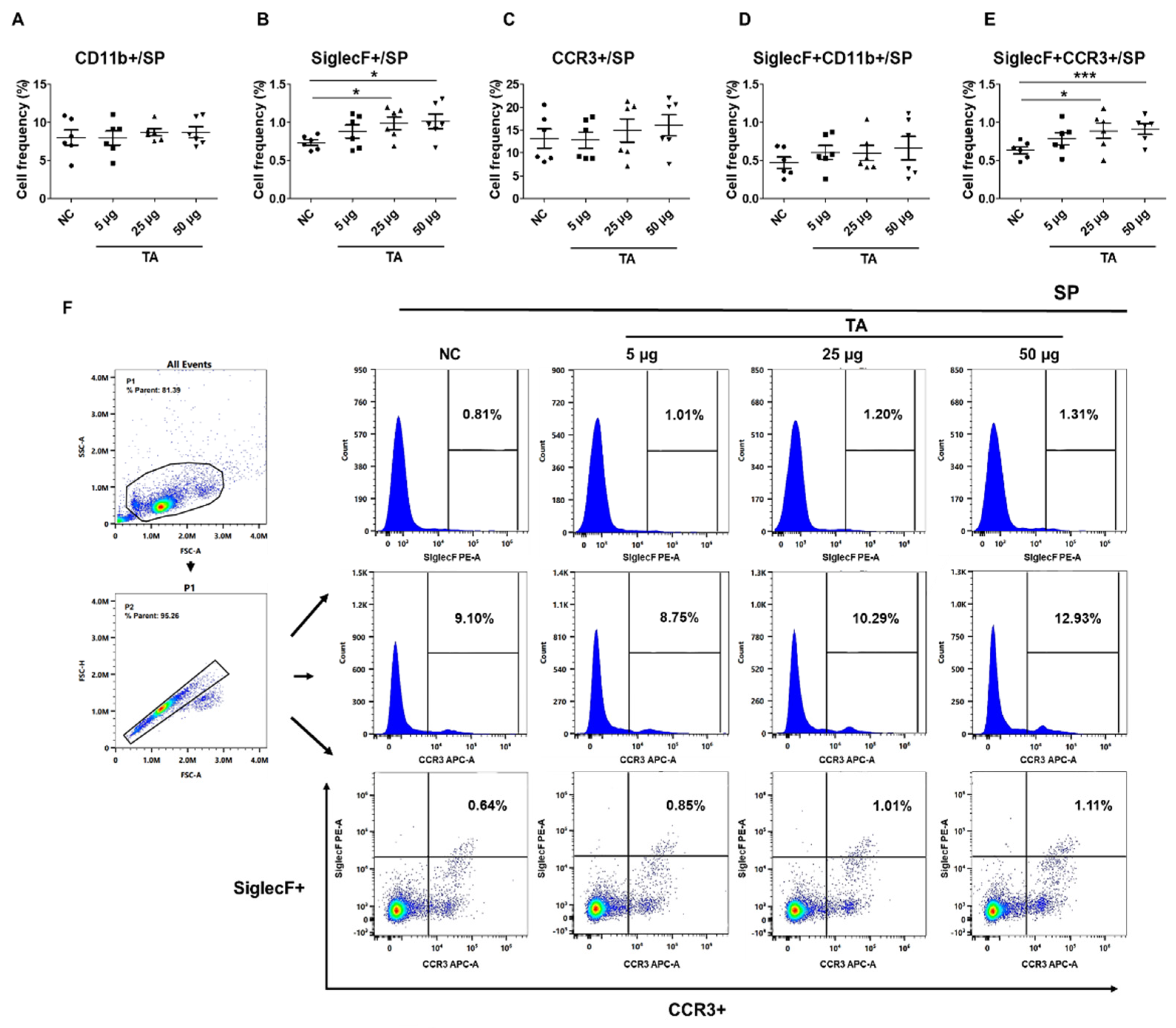

2.3. Upregulation of SiglecF+ and SiglecF+CCR3+ Cells in the Spleen of TA-Treated Mice

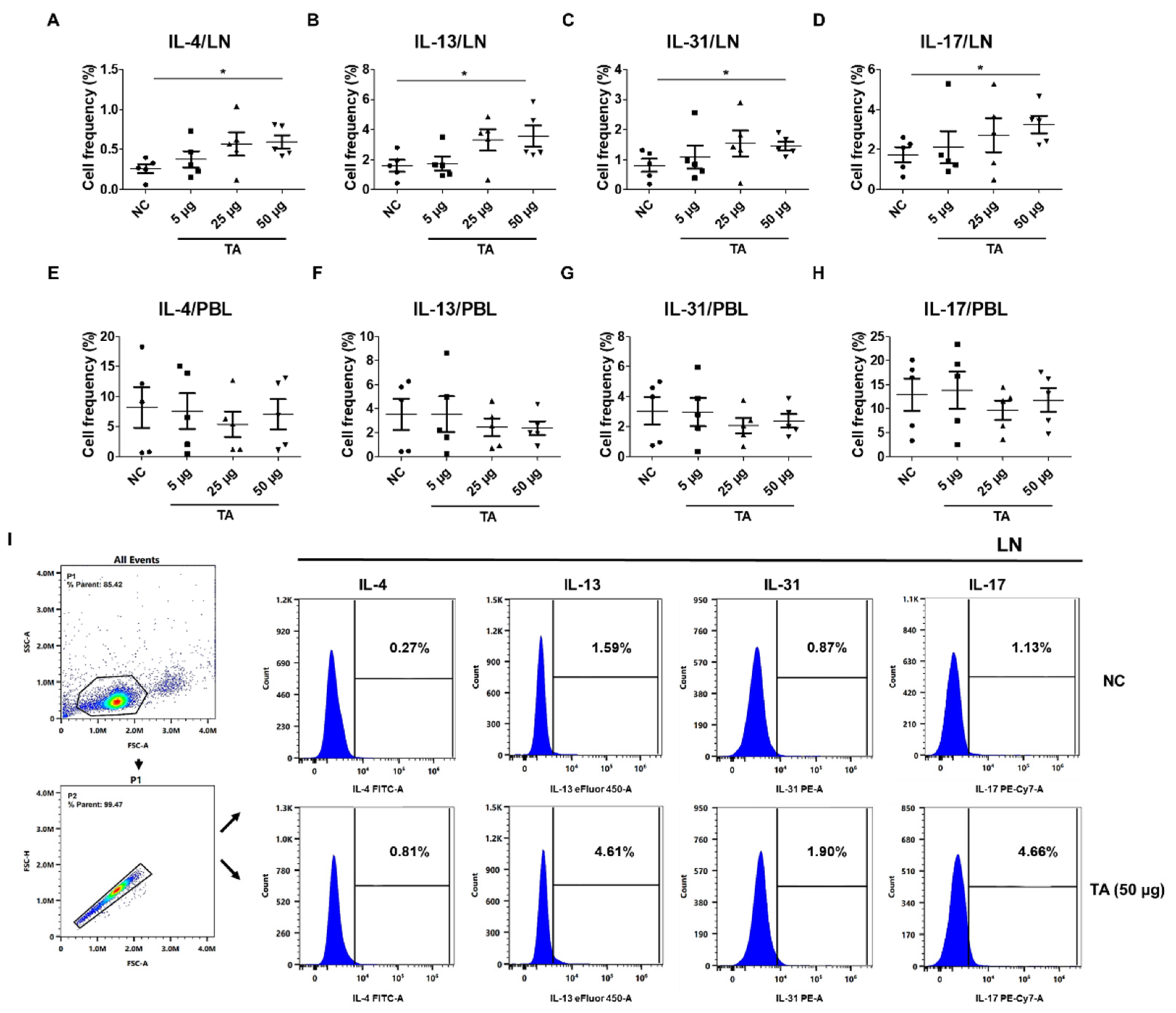

2.4. Increased Th2 Cytokine Expression in TA-Treated Mice

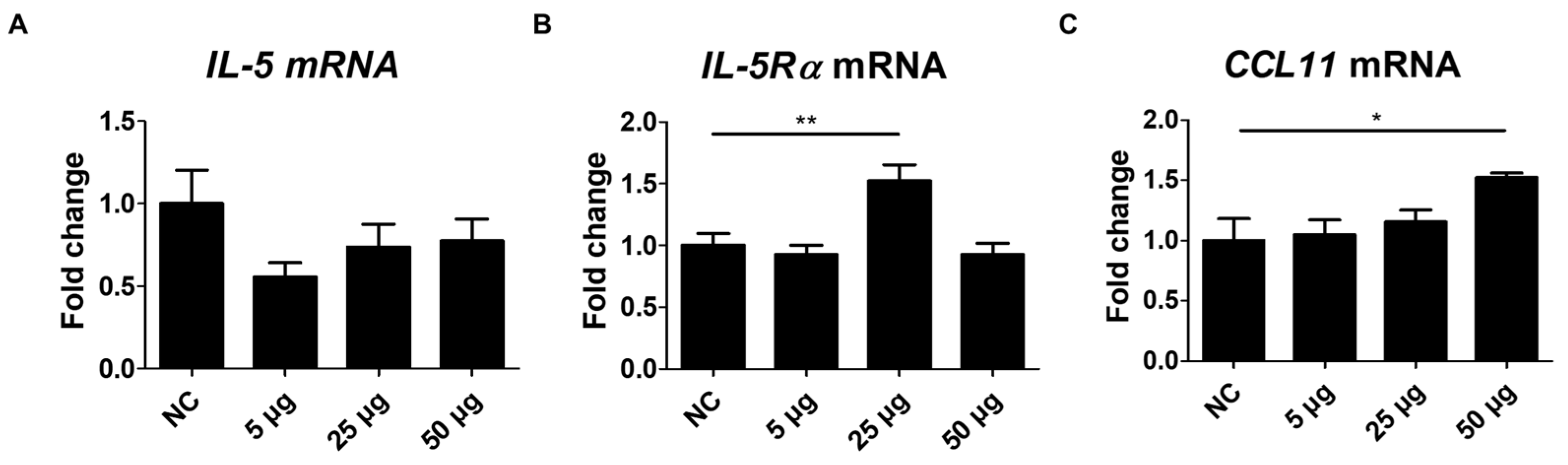

2.5. Changes in IL-5, IL-5Rα, and CCL11 mRNA Expression After TA Administration to Mice

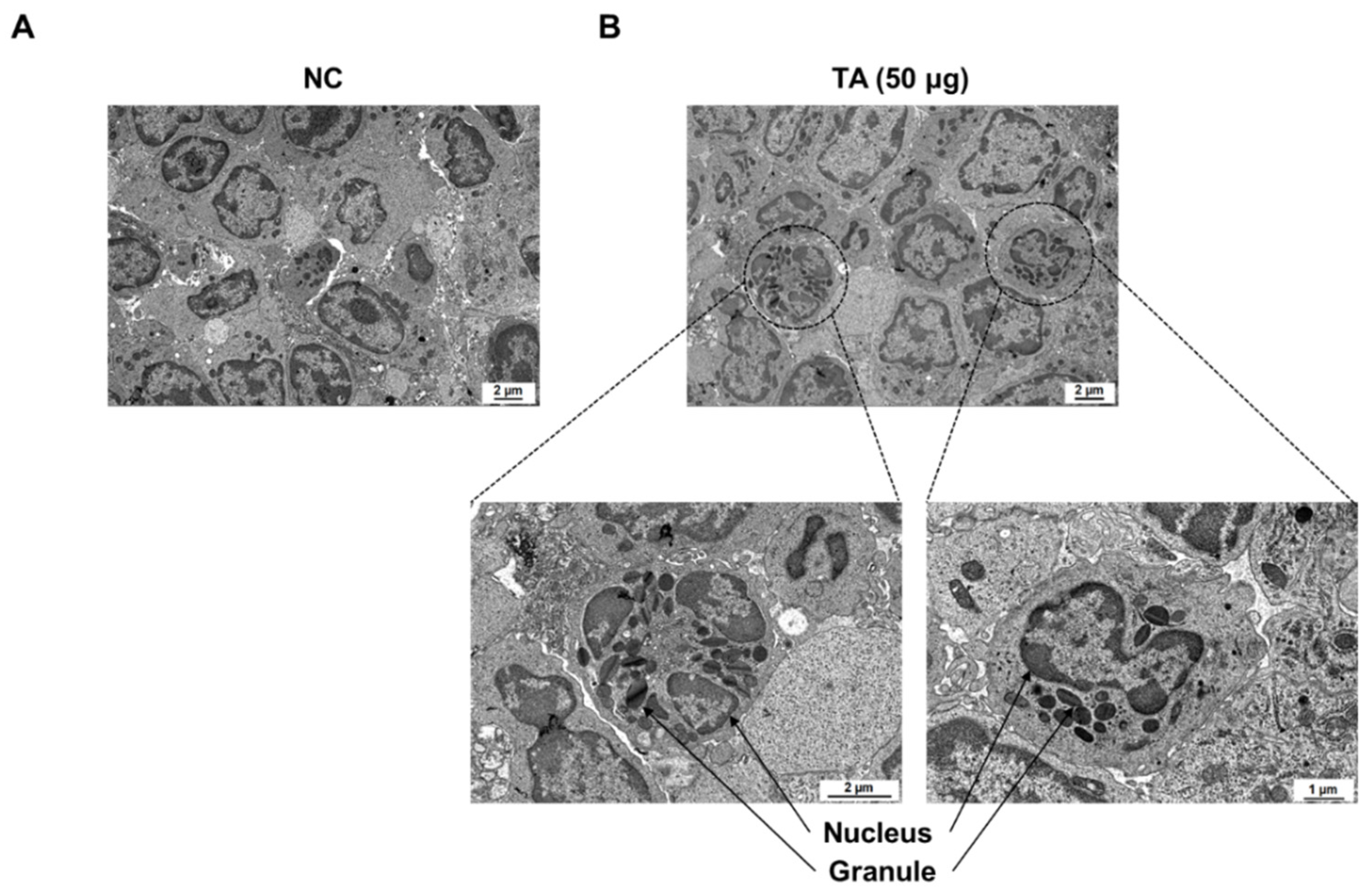

2.6. Eosinophil Identification in LN of TA-Treated Mice by Transmission Electron Microscope

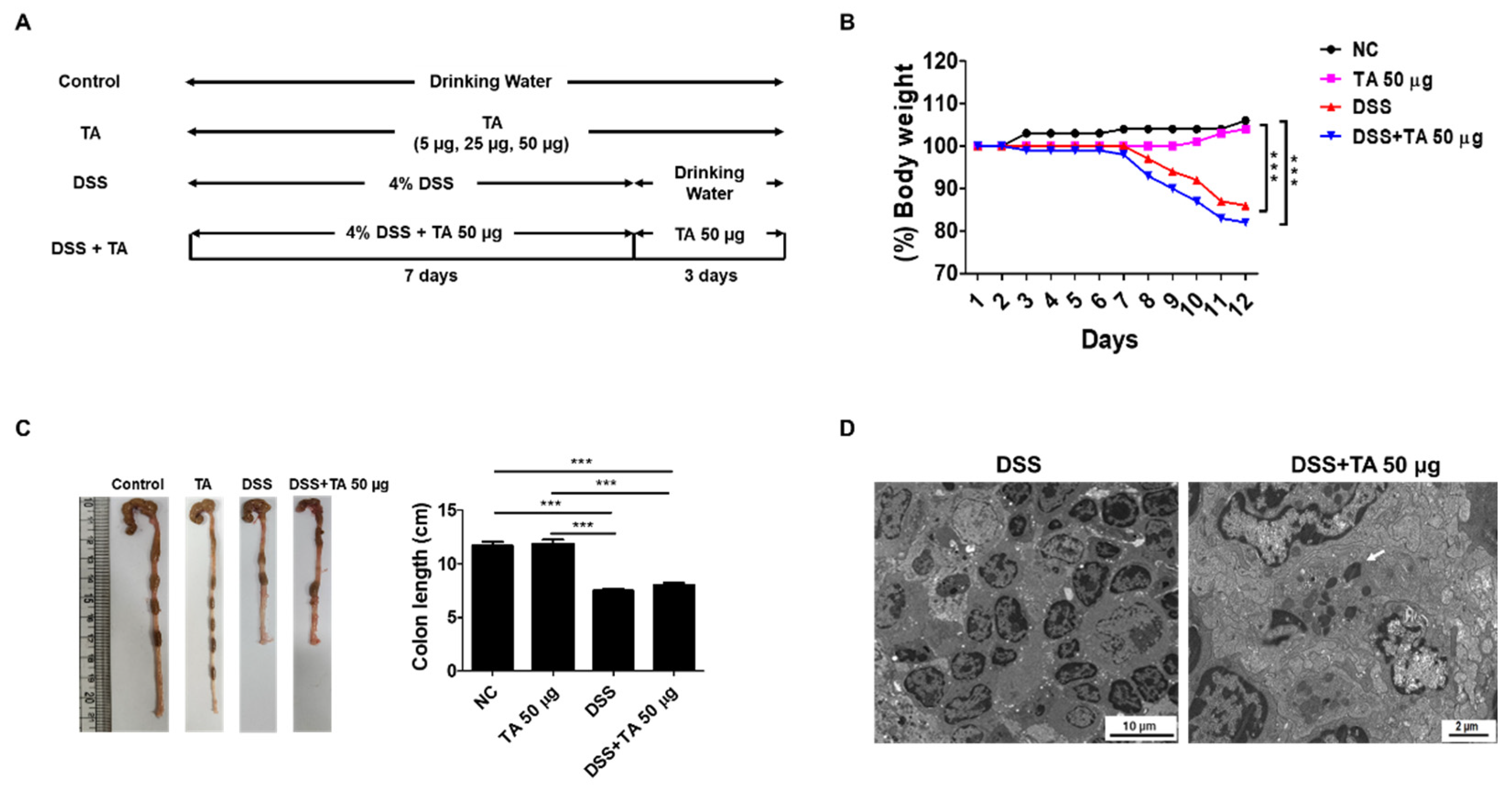

2.7. Effects of TA on DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice

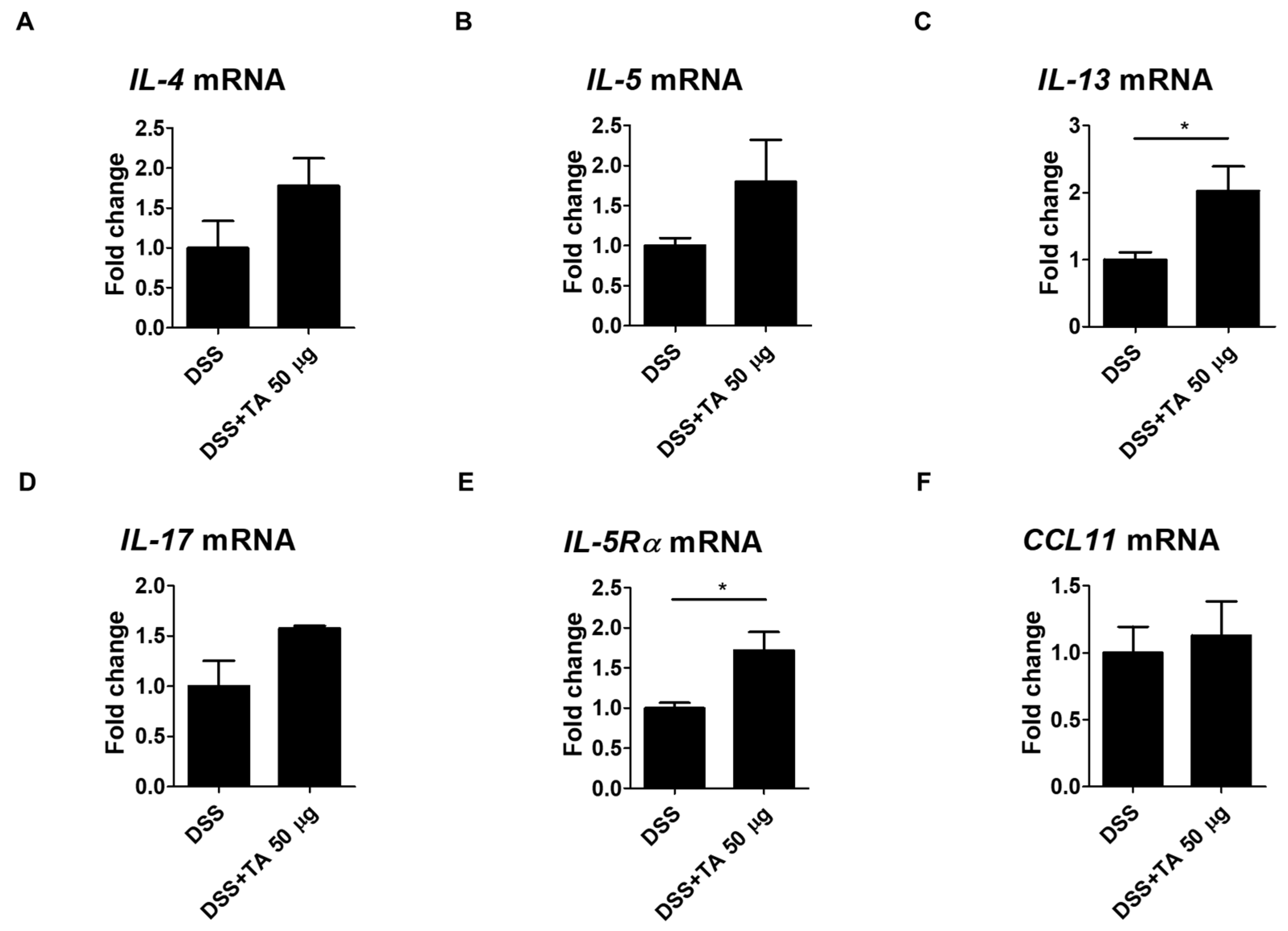

2.9. Th2 Cytokine mRNA Expression by TA Administration in Colitis Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice

4.2. Experimental Design and Dextran Sodium Sulfate (DSS)-Induced Colitis

4.3. Preparation of Single-Cell Suspensions

4.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

4.5. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| IL-4 | GGTCTCAACCCCCAGCTAGT | GCCGATGATCTCTCTCAAGTGAT |

| IL-5 | AGGCTTCCTGTCCCTACTCAT | ATTTCCACAGTACCCCCACG |

| IL-13 | CCTGGCTCTTGCTTGCCTT | GGTCTTGTGTGATGTTGCTCA |

| IL-17 | CCTCACACGAGGCACAAGTG | CTCTCCCTGGACTCATGTTTGC |

| CCR3 | TGATGTTTACTACCTGACTGGTG | TGCCATTCTACTTGTCTCTGGT |

| CCL11 | GAATCACCAACAACAGATGCAC | ATCCTGGACCCACTTCTTCTT |

| SiglecF | CTCCACAGAAGATGACCATCAGG | CTGTCAGCCATACAGACCAGGC |

| IL-5Rα | AGAACACTGTGTAGCCCTGTT | ACCTGTCCAGTGAGCTTCTTC |

| TLR2 | CACTGGGGGTAACATCGCTT | GAGAGAAGTCAGCCCAGCAA |

| TLR4 | CGAGAGCCCATGGAACACAT | CCCCTGGAAAGGAAGGTGTC |

| β-actin | TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT | AGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGCCTAG |

4.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothenberg, M.E.; Hogan, S.P. The eosinophil. Annu Rev Immunol 2006, 24, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, H.F.; Dyer, K.D.; Foster, P.S. Eosinophils: changing perspectives in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, E.; Cho, J.Y.; Rosenthal, P.; Chao, J.; Miller, M.; Pham, A.; Aceves, S.S.; Varki, A.; Broide, D.H. Siglec-F inhibition reduces esophageal eosinophilia and angiogenesis in a mouse model of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011, 53, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Dai, M.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, Y.; Peng, H.; Liu, K.; Zhu, X. Gene knockdown of CCR3 reduces eosinophilic inflammation and the Th2 immune response by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT pathway in allergic rhinitis mice. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnasco, D.; Ferrando, M.; Varricchi, G.; Puggioni, F.; Passalacqua, G.; Canonica, G.W. Anti-Interleukin 5 (IL-5) and IL-5Ra Biological Drugs: Efficacy, Safety, and Future Perspectives in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017, 4, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, J.C.; McNamee, E.N.; Fillon, S.A.; Hosford, L.; Harris, R.; Fernando, S.D.; Jedlicka, P.; Iwamoto, R.; Jacobsen, E.; Protheroe, C.; et al. Eosinophil-mediated signalling attenuates inflammatory responses in experimental colitis. Gut 2015, 64, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, P.C.; Rothenberg, M.E. Targeting eosinophils in allergy, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013, 12, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagome, K.; Nagata, M. Involvement and Possible Role of Eosinophils in Asthma Exacerbation. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, E.E.; Dellon, E.S. Review article: Emerging insights into the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of eosinophilic oesophagitis and other eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2024, 59, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Lu, Q. Eosinophilic Skin Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016, 50, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.J.; Akuthota, P.; Roufosse, F. Eosinophils and eosinophilic immune dysfunction in health and disease. Eur Respir Rev 2022, 3, 210150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, M.E.; Munitz, A.; Ackerman, S.J.; Drake, M.G.; Jackson, D.J.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Dougan, S.K.; Berdnikovs, S.; Schleich, F.; Matucci, A.; et al. Eosinophils in Health and Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. Mayo Clin Proc 2021, 96, 2694–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.A.; Bochner, B.S. Eosinophils and eosinophil-associated diseases: An update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 141, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, E.M.; Nutman, T.B. Eosinophilia in Infectious Diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2015, 35, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diny, N.L.; Rose, N.R.; Čiháková, D. Eosinophils in Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.P.; LeBlanc, J.F.; Hart, A.L. Ulcerative colitis: an update. Clin Med (Lond) 2021, 21, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Ha, C. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2020, 49, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kałużna, A.; Olczyk, P.; Komosińska-Vassev, K. The Role of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in the Pathogenesis and Development of the Inflammatory Response in Ulcerative Colitis. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrie, A.; Mourabet, M.E.; Weyant, K.; Clarke, K.; Gajendran, M.; Rivers, C.; Park, S.Y.; Hartman, D.; Saul, M.; Regueiro, M.; et al. Recurrent blood eosinophilia in ulcerative colitis is associated with severe disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci 2013, 58, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xenakis, J.J.; Howard, E.D.; Smith, K.M.; Olbrich, C.L.; Huang, Y.; Anketell, D.; Maldonado, S.; Cornwell, E.W.; Spencer, L.A. Resident intestinal eosinophils constitutively express antigen presentation markers and include two phenotypically distinct subsets of eosinophils. Immunology 2018, 154, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.C.; Yang, J.H. Dual Effects of Alpha-Hydroxy Acids on the Skin. Molecules 2018, 23, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, C.; Li, L.; Sun, Q.; Liu, L.; Shan, S.; Wang, P.; Liu, T.; et al. Tartaric acid ameliorates experimental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 975, 176668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Morikawa, T.; Takahashi, M.; Yoshida, M.; Ogawa, K. Obstructive nephropathy induced with DL-potassium hydrogen tartrate in F344 rats. J Toxicol Pathol 2015, 28, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Rothenberg, M.E. The Regulatory Function of Eosinophils. Microbiol Spectr 2016, 4, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, L.A.; Szela, C.T.; Perez, S.A.; Kirchhoffer, C.L.; Neves, J.S.; Radke, A.L.; Weller, P.F. Human eosinophils constitutively express multiple Th1, Th2, and immunoregulatory cytokines that are secreted rapidly and differentially. J Leukoc Biol 2009, 85, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.; Humbert, M.; Buhl, R.; Cruz, A.A.; Inoue, H.; Korom, S.; Hanania, N.A.; Nair, P. Revisiting Type 2-high and Type 2-low airway inflammation in asthma: current knowledge and therapeutic implications. Clin Exp Allergy 2017, 47, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamias, G.; Cominelli, F. Role of type 2 immunity in intestinal inflammation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2015, 31, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, M.F. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Shu, X. [Effect of CCR3 gene on related inflammatory cells in respiratory allergic diseases]. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2021, 35, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Grozdanovic, M.; Laffey, K.G.; Abdelkarim, H.; Hitchinson, B.; Harijith, A.; Moon, H.G.; Park, G.Y.; Rousslang, L.K.; Masterson, J.C.; Furuta, G.T.; et al. Novel peptide nanoparticle-biased antagonist of CCR3 blocks eosinophil recruitment and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 143, 669–680.e612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallusto, F.; Mackay, C.R.; Lanzavecchia, A. Selective expression of the eotaxin receptor CCR3 by human T helper 2 cells. Science 1997, 277, 2005–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manousou, P.; Kolios, G.; Valatas, V.; Drygiannakis, I.; Bourikas, L.; Pyrovolaki, K.; Koutroubakis, I.; Papadaki, H.A.; Kouroumalis, E. Increased expression of chemokine receptor CCR3 and its ligands in ulcerative colitis: the role of colonic epithelial cells in in vitro studies. Clin Exp Immunol 2010, 162, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xia, L.; Peng, W.; Xie, G.; Li, F.; Zhang, C.; Syeda, M.Z.; Hu, Y.; Lan, F.; Yan, F.; et al. CCL11/CCR3-dependent eosinophilia alleviates malignant pleural effusions and improves prognosis. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polosukhina, D.; Singh, K.; Asim, M.; Barry, D.P.; Allaman, M.M.; Hardbower, D.M.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Washington, M.K.; Gobert, A.P.; Wilson, K.T.; et al. CCL11 exacerbates colitis and inflammation-associated colon tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6540–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paplińska, M.; Hermanowicz-Salamon, J.; Nejman-Gryz, P.; Białek-Gosk, K.; Rubinsztajn, R.; Arcimowicz, M.; Placha, G.; Góra, J.; Chazan, R.; Grubek-Jaworska, H. Expression of eotaxins in the material from nasal brushing in asthma, allergic rhinitis and COPD patients. Cytokine 2012, 60, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, W.; Paplińska, M.; Targowski, T.; Jahnz-Rózyk, K.; Paluchowska, E.; Kucharczyk, A.; Kasztalewicz, B. Analysis of eotaxin 1/CCL11, eotaxin 2/CCL24 and eotaxin 3/CCL26 expression in lesional and non-lesional skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Cytokine 2010, 50, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhou, J.; Bi, H.; Li, L.; Gao, W.; Huang, M.; Adcock, I.M.; Barnes, P.J.; Yao, X. CCL11 as a potential diagnostic marker for asthma? J Asthma 2014, 51, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adar, T.; Shteingart, S.; Ben Ya’acov, A.; Bar-Gil Shitrit, A.; Goldin, E. From airway inflammation to inflammatory bowel disease: eotaxin-1, a key regulator of intestinal inflammation. Clin Immunol 2014, 153, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, A.; Borrelli, C.; Gonzalez-Perez, I.; Bach, K.; Acar, I.E.; Núñez, N.G.; Crepaz, D.; Handler, K.; Vu, V.P.; Lafzi, A.; et al. Active eosinophils regulate host defence and immune responses in colitis. Nature 2023, 615, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, H.; Hua, L.; Liu, Z.; Lin, G.; Cai, H.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; et al. Antagonizing interleukin-5 receptor ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in mice through reducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 965, 176331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, E.J.; Duplisea, J.; Dawicki, W.; Haidl, I.D.; Marshall, J.S. Tissue eosinophilia in a mouse model of colitis is highly dependent on TLR2 and independent of mast cells. Am J Pathol 2011, 178, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folci, M.; Ramponi, G.; Arcari, I.; Zumbo, A.; Brunetta, E. Eosinophils as Major Player in Type 2 Inflammation: Autoimmunity and Beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021, 1347, 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.E.; Sutherland, T.E.; Rückerl, D. IL-17 and neutrophils: unexpected players in the type 2 immune response. Curr Opin Immunol 2015, 34, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matucci, A.; Maggi, E.; Vultaggio, A. Eosinophils, the IL-5/IL-5Rα axis, and the biologic effects of benralizumab in severe asthma. Respir Med 2019, 160, 105819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigon, L.; Fettrelet, T.; Yousefi, S.; Simon, D.; Simon, H.U. Eosinophils from A to Z. Allergy 2023, 78, 1810–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakase, H.; Sato, N.; Mizuno, N.; Ikawa, Y. The influence of cytokines on the complex pathology of ulcerative colitis. Autoimmun Rev 2022, 21, 103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoving, J.C. Targeting IL-13 as a Host-Directed Therapy Against Ulcerative Colitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, V.; Kreiger, P.; Kutsch, E. Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis and Colitis: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016, 50, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P.; Degenfeld-Schonburg, L.; Sadovnik, I.; Horny, H.P.; Arock, M.; Simon, H.U.; Reiter, A.; Bochner, B.S. Eosinophils and eosinophil-associated disorders: immunological, clinical, and molecular complexity. Semin Immunopathol 2021, 43, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.N.; Khatry, D.B.; Ke, X.; Ward, C.K.; Gossage, D. High blood eosinophil count is associated with more frequent asthma attacks in asthma patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014, 113, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-López, I.; Parilli-Moser, I.; Arancibia-Riveros, C.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Castañer, O.; Lapetra, J.; Arós, F.; et al. Urinary Tartaric Acid, a Biomarker of Wine Intake, Correlates with Lower Total and LDL Cholesterol. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurram; Ghaffar, A.; Zulfiqar, S.; Khan, M.; Latif, M.; Cochran, E.W. Synthesis of polyaniline-coated composite anion exchange membranes based on polyacrylonitrile for the separation of tartaric acid via electrodialysis. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 29648–29657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Castle, L.; Engel, K.H.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gürtler, R.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Husøy, T.; et al. Re-evaluation of l(+)-tartaric acid (E 334), sodium tartrates (E 335), potassium tartrates (E 336), potassium sodium tartrate (E 337) and calcium tartrate (E 354) as food additives. Efsa j 2020, 18, e06030. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, B.; Emmen, H.; van Otterdijk, F.; Lau, A. Subchronic and reproductive/developmental (screening level) toxicity of complexation products of iron trichloride and sodium tartrate (FemTA). J Food Sci 2013, 78, T1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochner, B.S.; O’Sullivan, J.A.; Chang, A.T.; Youngblood, B.A. Siglecs in allergy and asthma. Mol Aspects Med 2023, 90, 101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, S.; Koohpeyma, F.; Samare-Najaf, M.; Jahromi, B.N.; Jafarinia, M.; Samareh, A.; Hashempur, M.H. The Effects of L-Tartaric Acid on Ovarian Histostereological and Serum Hormonal Analysis in an Animal Model of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reprod Sci 2024, 31, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amssayef, A.; Bouadid, I.; Eddouks, M. L-Tartaric Acid Exhibits Antihypertensive and Vasorelaxant Effects: The Possible Role of eNOS/NO/cGMP Pathways. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem 2023, 21, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, M.; Sakamoto, S.; Kamio, Y.; Saito, M.; Miyake, Y.; Yasui, M.; Matsuda, T. Cough threshold to inhaled tartaric acid and bronchial responsiveness to methacholine in patients with asthma and sino-bronchial syndrome. Intern Med 1992, 31, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, P.S.; Hogan, S.P.; Ramsay, A.J.; Matthaei, K.I.; Young, I.G. Interleukin 5 deficiency abolishes eosinophilia, airways hyperreactivity, and lung damage in a mouse asthma model. J Exp Med 1996, 183, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, E.; Cai, F.; Holweg, C.T.J.; Wong, K.; Brumm, J.; Arron, J.R. Interleukin-13 in Asthma and Other Eosinophilic Disorders. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017, 4, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaian, M.T.; Page, K.M.; Fish, S.; Brennan, A.; Cook, T.A.; Moreira, K.; Zhang, M.; Jesson, M.; Marquette, K.; Agostinelli, R.; et al. Therapeutic activity of an interleukin-4/interleukin-13 dual antagonist on oxazolone-induced colitis in mice. Immunology 2014, 143, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.M.; Banerjee, G. The role of Th17/IL-17 on eosinophilic inflammation. J Autoimmun 2013, 40, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgia, F.; Custurone, P.; Li Pomi, F.; Cordiano, R.; Alessandrello, C.; Gangemi, S. IL-31: State of the Art for an Inflammation-Oriented Interleukin. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoine, F.; Lacy, P. Eosinophil cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors: emerging roles in immunity. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, L.A.; Horst, S.N.; Chaturvedi, R.; Brown, C.T.; Allaman, M.M.; Scull, B.P.; Singh, K.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Chitnavis, M.V.; Hodges, M.E.; et al. High-throughput multi-analyte Luminex profiling implicates eotaxin-1 in ulcerative colitis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e82300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, M.; Nakajima, T.; Imai, T.; Harada, S.; Combadiere, C.; Tiffany, H.L.; Murphy, P.M.; Yoshie, O. Molecular cloning of human eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective CC chemokine, and identification of a specific eosinophil eotaxin receptor, CC chemokine receptor 3. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 7725–7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Kohli, L.L.; Stone, M.J. Characterization of binding between the chemokine eotaxin and peptides derived from the chemokine receptor CCR3. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 27250–27257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnault, S.; Johansson, M.W.; Mathur, S.K. Eosinophils, beyond IL-5. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molteni, M.; Gemma, S.; Rossetti, C. The Role of Toll-Like Receptor 4 in Infectious and Noninfectious Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2016, 2016, 6978936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).