Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

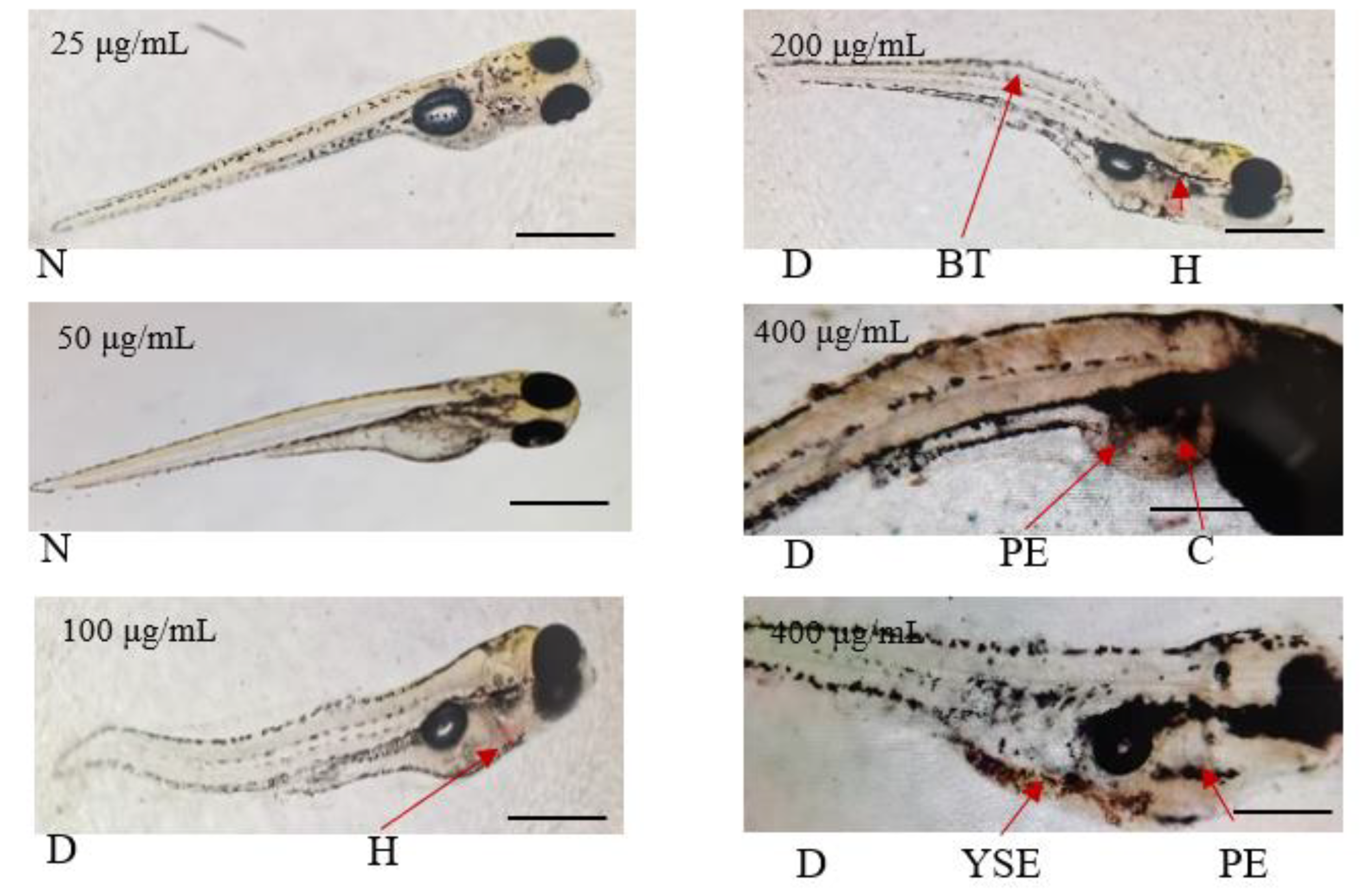

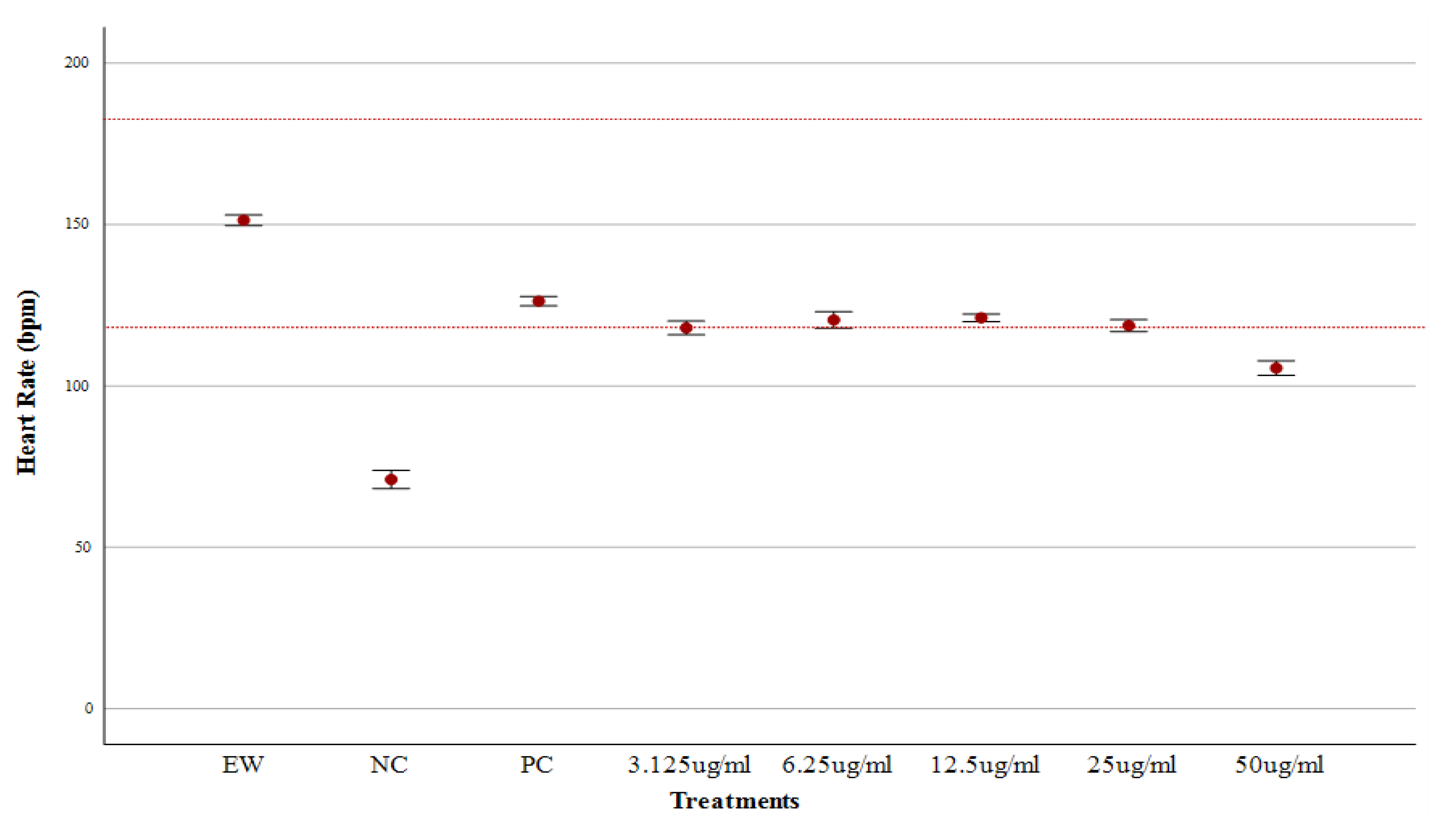

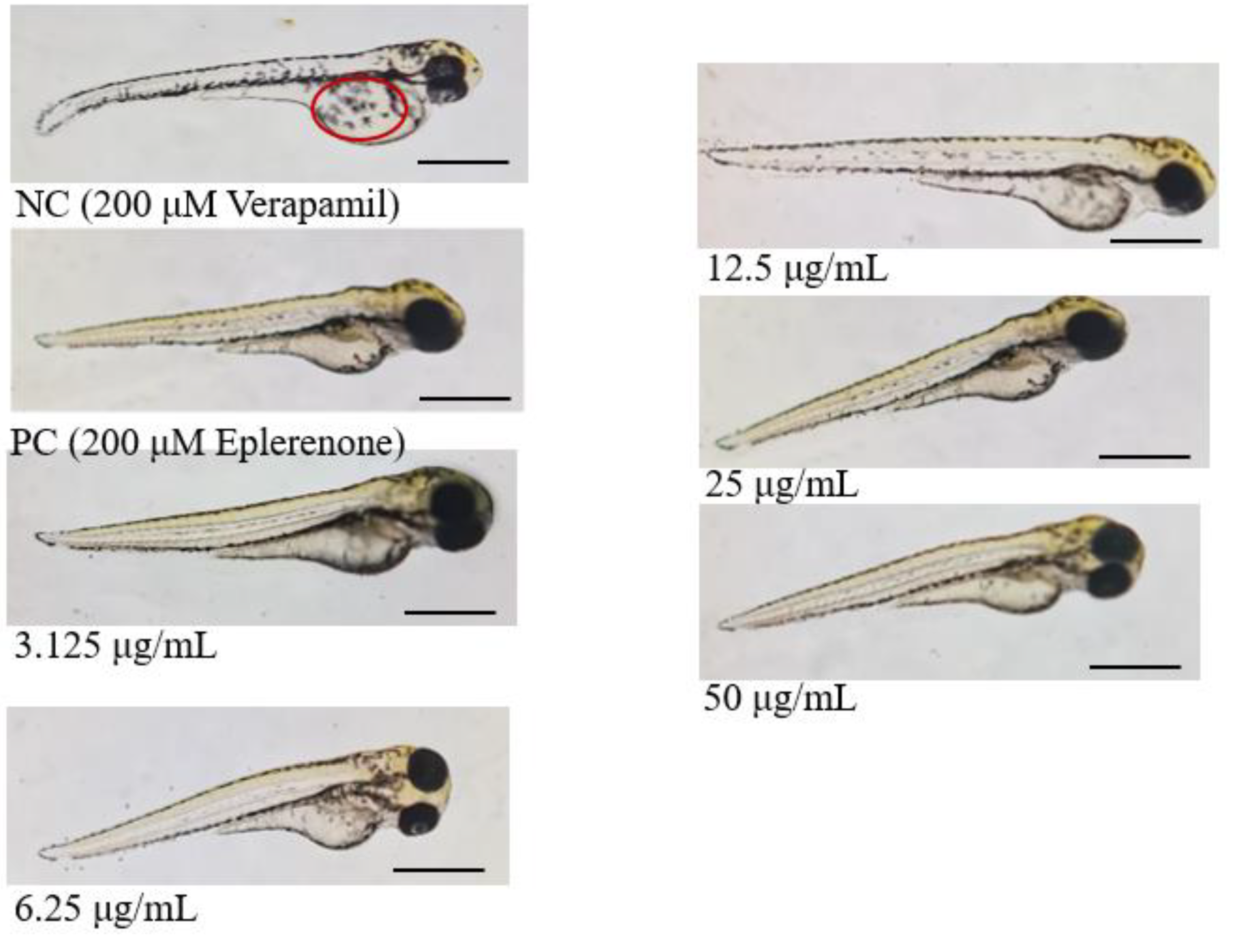

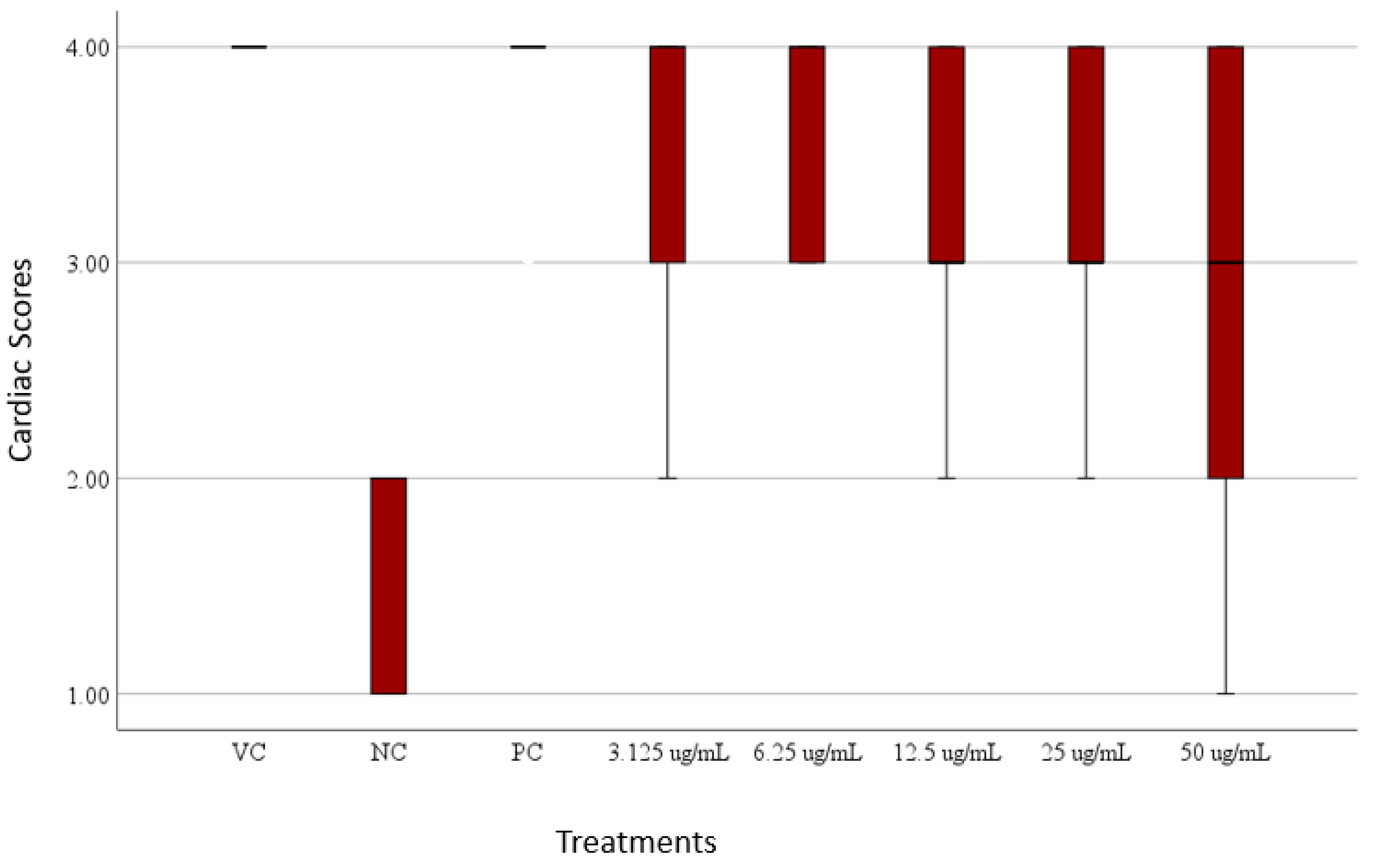

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), a major global health concern, is characterized by cardiac complications that can lead to death. The commonly used treatments for this condition are synthetic drugs, but these often come with risky side effects. A potential alternative is the use of traditional medicinal plants, such as Amaranthus viridis, which is rich in bioactive compounds. This study aimed to determine the non-toxic concentration of A. viridis ethanolic extract, investigate its cardioprotective effects on zebrafish (Danio rerio) heart rate and cardiac phenotype, qualitatively assess the presence of phytochemicals, and assess its free radical scavenging activity using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). Zebrafish larvae at 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf) were used to evaluate mortality and optimize dosing. Physio-morphological screening was conducted by pre-treating zebrafish larvae with the extract 4 hours prior to administering a heart failure inducer, verapamil. The maximum non-toxic concentration was found to be 25 µg/mL, as all zebrafish survived after 24 hours. Mortality began at 50 µg/mL, and concentrations from 100 µg/mL to 400 µg/mL resulted in 100% mortality. All tested concentrations of A. viridis leaf extract showed cardioprotective activity in the physio-morphological analysis. Phytochemical analysis detected the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, and saponins. Furthermore, A. viridis exhibited free radical scavenging activity from all tested concentrations. Based on the results, A. viridis exhibited cardioprotective effects against verapamil-induced cardiotoxicity, as evidenced by the recovery of heart rate and cardiac phenotype in the zebrafish model.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Collection and Authentication of Plant Material

Plant Extraction

Preparation of Egg Water

Ethics Declaration

Establishment of Zebrafish Aquarium and Husbandry

Procurement of Zebrafish

Breeding and Embryo Isolation

Preliminary Mortality Test of A. viridis Extracts Against Zebrafish Larvae

Treatment Protocol for Assessing Cardioprotective Activity

Heart Rate Assessment

Scoring on Cardiac Phenotypes

Disposal of Zebrafish Carcass

Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis

Statistical Analyses

Results and Discussion

| Concentrations (μg/mL) |

A. viridis (%) |

| 0.5% DMSO | 0 |

| 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 0 |

| 50 | 13.33% |

| 100 | 100% |

| 200 | 100% |

| 400 | 100% |

Heart Rate and Cardiac Phenotype Response of Zebrafish larvae Protected by Amaranthus viridis Leaf Ethanolic Extracts Against Verapamil-Induced Heart Failure

| Treatments | Cardiac functions and phenotypes |

| Egg water | Normal function and no visible abnormality |

| NC – Verapamil | No contraction in the heart; Weak contraction in the atria; No circulation; Pericardial edema |

| PC – Eplerenone + Verapamil | Some showed slow circulation, while most had no visible abnormalities |

| 3.125 μg/mL A. viridis + Verapamil | Some showed slow circulation, while most had no visible abnormalities |

| 6.25 μg/mL A. viridis + Verapamil | Some showed slow circulation, while most had no visible abnormalities |

| 12.5 μg/mL A. viridis + Verapamil | Some showed slow circulation, while most had no visible abnormalities |

| 25 μg/mL A. viridis + Verapamil | Some showed slow circulation, while most had no visible abnormalities |

| 50 μg/mL A. viridis + Verapamil | No contraction in the heart; Weak contraction in the atria; No circulation; |

Phytochemical Composition of A. viridis Crude Leaf Extracts

| A. viridis | |

| Alkaloids | + |

| Flavonoids | + |

| Phenols | - |

| Saponins | + |

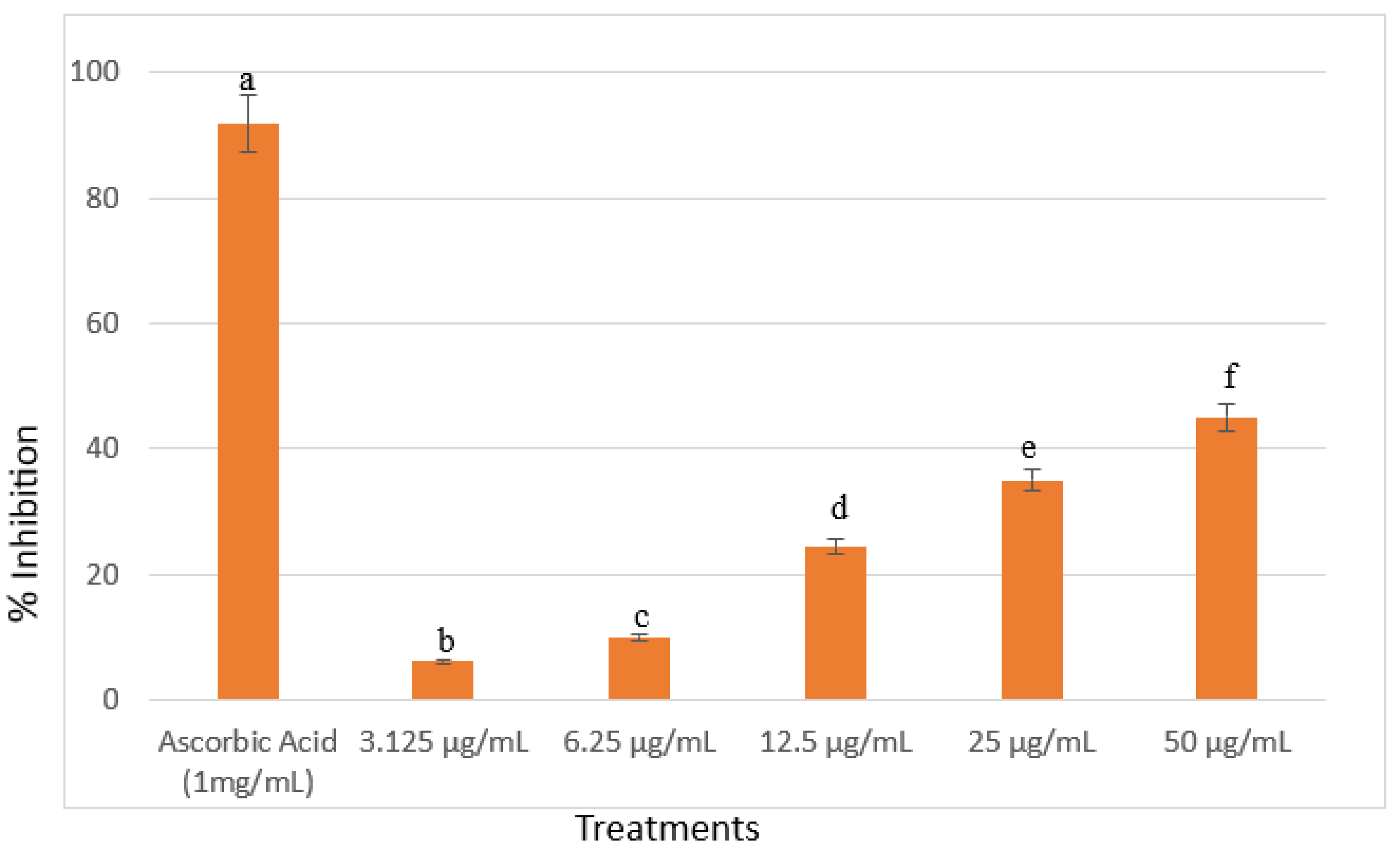

In Vitro Free Radical Scavenging Activity of A. viridis Ethanolic Leaf Extracts

Summary, Conclusion, and Recommendation

References

- Abbate, F., Maugeri, A., Laurà, R., Levanti, M., Navarra, M., Cirmi, S., Germanà, A. (2021). Zebrafish as a useful model to study oxidative stress-linked disorders: Focus on flavonoids. Antioxidants (Basel), 10(5), 668. [CrossRef]

- Abbate, F., Maugeri, A., Laurà, R., Levanti, M., Navarra, M., Cirmi, S., & Germanà, A. (2021). Zebrafish as a useful model to study oxidative stress-linked disorders: Focus on flavonoids. Antioxidants (Basel), 10(5), 668. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-alim, M. E., Serag, M. S., Moussa, H. R., Elgendy, M. A., Mohesien, M. T., & Salim, N. S. (2023). Phytochemical screening and antioxidant potential of Lotus corniculatus and Amaranthus viridis. Egyptian Journal of Botany, 63(2), 665–681.

- Ahmed, S. A., Hanif, S., & Iftkhar, T. (2013). Phytochemical profiling with antioxidant and antimicrobial screening of Amaranthus viridis L. leaf and seed extracts. Open Journal of Medical Microbiology.

- Alafiatayo, A. A., Lai, K.-S., Syahida, A., Mahmood, M., & Shaharuddin, N. A. (2019). Phytochemical evaluation, embryotoxicity, and teratogenic effects of Curcuma longa extract on zebrafish (Danio rerio). Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J. K. (2014). Meyler's side effects of drugs 15E: The international encyclopedia of adverse drug reactions and interactions. Newnes.

- Bachheti, R. K., Worku, L. A., Gonfa, Y. H., Zebeaman, M., Pandey, D. P., & Bachheti, A. (2022). Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases with plant phytochemicals: A review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2022.

- Bagher, P., & Segal, S. S. (2011). Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation: Role of conducted vasodilation. Acta Physiologica, 202(3), 271–284.

- Barteková, M., Adameová, A., Görbe, A., Ferenczyová, K., Pecháňová, O., Lazou, A., & Giricz, Z. (2021). Natural and synthetic antioxidants targeting cardiac oxidative stress and redox signaling in cardiometabolic diseases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 169, 446–477. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K., Chopra, C., Bhardwaj, P., Dhanjal, D. S., Singh, R., Najda, A., & Manickam, S. (2022). Biogenic metallic nanoparticles from seed extracts: Characteristics, properties, and applications. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2022.

- Bowley, G., Kugler, E., Wilkinson, R., Lawrie, A., van Eeden, F., Chico, T. J. A., Evans, P. C., Noël, E. S., & Serbanovic-Canic, J. (2022). Zebrafish as a tractable model of human cardiovascular disease. British Journal of Pharmacology, 179(5), 900–917. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Cao, B., Varghese, C., Mikkelsen, B., Weiderpass, E., & Soerjomataram, I. (2021). Comparing cancer and cardiovascular disease trends in 20 middle- or high-income countries 2000–19: A pointer to national trajectories towards achieving sustainable development goal target 3.4. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 100, 102290.

- Brittijn, S. A., Duivesteijn, S. J., Belmamoune, M., Bertens, L. F., Bitter, W., Debruijn, J. D., & Richardson, M. K. (2009). Zebrafish development and regeneration: New tools for biomedical research. International Journal of Developmental Biology, 53(5-6), 835–850.

- Brown, D. R., Samsa, L. A., Qian, L., & Liu, J. (2016). Advances in the study of heart development and disease using zebrafish. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 3(2), 13. [CrossRef]

- Bucciarelli, V., Caterino, A. L., Bianco, F., Caputi, C. G., Salerni, S., Sciomer, S., & Gallina, S. (2020). Depression and cardiovascular disease: The deep blue sea of women’s heart. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 30(3), 170–176.Chatterjee, S., Min, L., Karuturi, R.K., and Lufkin, T. (2010) The role of post-transcriptional RNA processing and plasmid vector sequences on transient transgene expression in zebrafish. Transgenic Research. 19(2):299-304.

- Chen, J., Tchivelekete, G. M., Zhou, X., Tang, W., Liu, F., Liu, M., Zhao, C., Shu, X., & Zeng, Z. (2021). Anti-inflammatory activities of Gardenia jasminoides extracts in retinal pigment epithelial cells and zebrafish embryos. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 22(1), 700. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Xu, M., Gong, Z. (2018). Comparative cardio and developmental toxicity induced by the popular medicinal extract of Sutherlandia frutescens (L.) R.Br. detected using a zebrafish Tuebingen embryo model. BMC Complement Altern Med 18, 273. [CrossRef]

- Choy, K. W., Murugan, D., & Mustafa, M. R. (2018). Natural products targeting ER stress pathway for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacological Research, 132, 119–129.

- Cordero-Maldonado, M. L., Siverio-Mota, D., Vicet-Muro, L., Wilches-Arizábala, I. M., Esguerra, C. V., de Witte, P. A., & Crawford, A. D. (2013). Optimization and pharmacological validation of a leukocyte migration assay in zebrafish larvae for the rapid in vivo bioactivity analysis of anti-inflammatory secondary metabolites. PLoS One, 8(10), e75404.

- Corpuz, J. C. (2023). Cardiovascular disease in the Philippines: a new public health emergency? Journal of Public Health, fdad175.

- Daniels, M., Donilon, T., & Bollyky, T. J. (2014). The emerging global health crisis: noncommunicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries. Council on Foreign Relations independent task force report, (72).

- Dlugos, C. A., & Rabin, R. A. (2010). Structural and Functional Effects of Developmental Exposure to Ethanol on the Zebrafish Heart. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(6), 1013–1021 . [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A., Ghosh, N. S., & Singh, R. (2022). Zebrafish as An Emerging Model: An Important Testing Platform for Biomedical Science. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results. Volume, 13(3), 2.

- Dubińska-Magiera M, Daczewska M, Lewicka A, Migocka-Patrzałek M, Niedbalska-Tarnowska J, Jagla K. (2016). Zebrafish: A Model for the Study of Toxicants Affecting Muscle Development and Function. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Dweck, M. R., Williams, M. C., Moss, A. J., Newby, D. E., & Fayad, Z. A. (2016). Computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance in ischemic heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 68(20), 2201-2216.

- Echeazarra, L., Hortigón-Vinagre, M. P., Casis, O., & Gallego, M. (2021). Adult and developing zebrafish as suitable models for cardiac electrophysiology and pathology in research and industry. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 607860. [CrossRef]

- Eimon, P. M., & Ashkenazi, A. (2010). The zebrafish as a model organism for the study of apoptosis. Apoptosis, 15, 331–349.

- Fatisson, J., Oswald, V., & Lalonde, F. (2016). Influence diagram of physiological and environmental factors affecting heart rate variability: an extended literature overview. Heart international, 11(1), heartint-5000232.

- FitzSimons, M., Beauchemin, M., Smith, A. M., Stroh, E. G., Kelpsch, D. J., Lamb, M. C., Tootle, T. L., & Yin, V. P. (2020). Cardiac injury modulates critical components of prostaglandin E2 signaling during zebrafish heart regeneration. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 3095. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, E. L., Preston, C. D., & Lokman, P. M. (2010). Zebrafish (Danio rerio) and the egg size versus egg number trade off: effects of ration size on fecundity are not mediated by orthologues of the Fec gene. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 22(6), 1015-1021.

- Fouad, M., Ghareeb, M., Aidy, E., Tabudravu, J., Sayed, A., Tammam, M., & Mwaheb, M. (2024). Exploring the antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial potential of Amaranthus viridis L. collected from Fayoum depression: Phytochemical and biological aspects. South African Journal of Botany, 166. [CrossRef]

- Fukuta, H., & Little, W. C. (2008). The cardiac cycle and the physiologic basis of left ventricular contraction, ejection, relaxation, and filling. Heart Failure Clinics, 4(1), 1-11.

- Gandhi, P., Samarth, R. M., & Peter, K. (2020). Bioactive Compounds of Amaranth (Genus Amaranthus). Bioactive Compounds in Underutilized Vegetables and Legumes, 1-3.

- Geetha, R. G., & Ramachandran, S. (2021). Recent advances in the anti-inflammatory activity of plant-derived alkaloid rhynchophylline in neurological and cardiovascular diseases. Pharmaceutics, 13(8), 1170.

- Genge, C. E., Lin, E., Lee, L., Sheng, X., Rayani, K., Gunawan, M., & Tibbits, G. F. (2016). The zebrafish heart as a model of mammalian cardiac function. Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology, Vol. 171, 99-136.

- Giardoglou, P., & Beis, D. (2019). On zebrafish disease models and matters of the heart. Biomedicines, 7(1), 15.

- González-Rosa JM, Burns CE, Burns CG. Zebrafish heart regeneration: 15 years of discoveries. Regeneration (Oxf). 2017 Sep 28;4(3):105-123. [CrossRef]

- González-Rosa, J. M. (2022). Zebrafish models of cardiac disease: From fortuitous mutants to precision medicine. Circulation Research, 130(12), 1803-1826.

- Haege, E. R., Huang, H. C., & Huang, C. C. (2021). Identification of Lactate as a Cardiac Protectant by Inhibiting Inflammation and Cardiac Hypertrophy Using a Zebrafish Acute Heart Failure Model. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 14(3), 261. [CrossRef]

- Horng J.L., Hsiao B.Y., Lin W.T., Lin T.T., Chang C.Y., & Lin L.Y. (2024). Investigation of verapamil-induced cardiorenal dysfunction and compensatory ion regulation in zebrafish embryos. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Hou Y, Liu X, Qin Y, Hou Y, Hou J, Wu Q, Xu W. (2023). Zebrafish as model organisms for toxicological evaluations in the field of food science. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. [CrossRef]

- Hu, N., Sedmera, D., Yost, H. J., & Clark, E. B. (2000). Structure and function of the developing zebrafish heart. The Anatomical Record: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists, 260(2), 148-157.

- Huang, C.C., Monte, A., Cook, J. M., Kabir, M. S., & Peterson, K. P. (2013). Zebrafish Heart Failure Models for the Evaluation of Chemical Probes and Drugs. ASSAY and Drug Development Technologies, 11(9-10), 561–572. [CrossRef]

- Iamonico, D., Hussain, A. N., Sindhu, A., Saradamma Anil Kumar, V. N., Shaheen, S., Munir, M., & Fortini, P. (2023). Trying to Understand the Complicated Taxonomy in Amaranthus (Amaranthaceae): Insights on Seeds Micromorphology. Plants, 12(5), 987.

- Imam, M. U., Zhang, S., Ma, J., Wang, H., & Wang, F. (2017). Antioxidants mediate both iron homeostasis and oxidative stress. Nutrients, 9(7), 671.

- Iqbal, M. J., Hanif, S., Mahmood, Z., Anwar, F., & Jamil, A. (2012). Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Chowlai (Amaranthus viridis L.) leaf and seed extracts. J. Med. Plants Res, 6(27), 4450-4455.

- Irion, U., & Nüsslein-Volhard, C. (2022). Developmental genetics with model organisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(30), e2122148119. ISSN 0254-6299. [CrossRef]

- Jewhurst, K., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2015). Beyond the mammalian heart: Fish and amphibians as a model for cardiac repair and regeneration. Journal of Developmental Biology, 4(1), 1.

- Jin, L., Pan, Y., Li, Q., Li, J., & Wang, Z. (2021). Elabela gene therapy promotes angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 25(17), 8537-8545.

- Jing, L., Xi, L., Chen, Y., Chen, Z., Zhang, L. H., Fang, F., & Jiang, L. X. (2013). National survey of doctor-reported secondary preventive treatment for patients with acute coronary syndrome in China. Chinese medical journal, 126(18), 3451-3455.

- Jyotsna, F. N. U., Ahmed, A., Kumar, K., Kaur, P., Chaudhary, M. H., Kumar, S., & Kumar, F. K. (2023). Exploring the complex connection between diabetes and cardiovascular disease: analyzing approaches to mitigate cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes. Cureus, 15(8).

- Kebler, M., Just, S., & Rottbauer, W. (2012). Ion flux dependent and independent functions of ion channels in the vertebrate heart: lessons learned from zebrafish. Stem Cells International, 2012.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B., & Fernandez, D. G. (2003). Culture ingested: On the indigenization of Phillipine food.

- Kossack, M., Hein, S., Juergensen, L., Siragusa, M., Benz, A., Katus, H. A., & Hassel, D. (2017). Induction of cardiac dysfunction in developing and adult zebrafish by chronic isoproterenol stimulation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 108, 95-105.

- Kretz, C.A., Weyand, A.C., & Shavit, J.A. Modeling Disorders of Blood Coagulation in the Zebrafish. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2015 Jun;3(2):155-161. [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P. M., Petersen, K. S., Velarde, G., Barnard, N. D., Miller, M., Ros, E., & Freeman, A. M. (2020). Barriers, opportunities, and challenges in addressing disparities in diet-related cardiovascular disease in the United States. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(7), e014433.

- Krishna, P.S., Nenavath, R.K., Sudha-Rani, S., Anupalli, R.R. (2023). Cardioprotective action of Amaranthus viridis methanolic extract and its isolated compound Kaempferol through mitigating lipotoxicity, oxidative stress and inflammation in the heart. 3 Biotech. [CrossRef]

- Krum, H., Massie, B., Abraham, W. T., Dickstein, K., Kober, L., McMurray, J. J., & atmosphere investigators. (2011). Direct renin inhibition in addition to or as an alternative to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale and design of the Aliskiren Trial to Minimize OutcomeS in Patients with HEart failure (Atmosphere) study. European journal of heart failure, 13(1), 107-114.

- Kumar, S., & Pandey, A. K. (2013). Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Yadav, M., Yadav, A., & Yadav, J. P. (2017). Impact of spatial and climatic conditions on phytochemical diversity and in vitro antioxidant activity of Indian Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. South African Journal of Botany, 111, 50–59. [CrossRef]

- Kumari S, Elancheran R, Devi R. (2018). Phytochemical screening, antioxidant, antityrosinase, and antigenotoxic potential of Amaranthus viridis extract. Indian J Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M., Zinta, G., Chauhan, R., Kumar, A., Singh, S., & Singh, S. (2023). Genetic resources and breeding approaches for improvement of amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Frontiers in Nutrition, 10.

- Lahera, V., Goicoechea, M., Garcia de Vinuesa, S., Miana, M., Heras, N. D. L., Cachofeiro, V., & Luno, J. (2007). Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis: beneficial effects of statins. Current medicinal chemistry, 14(2), 243-248.

- Lalhminghlui, K., & Jagetia, G.C. (2018). Evaluation of the free-radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of Chilauni, Schima wallichii Korth in vitro. Future Sci OA. FSO272. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. T., & Walsh, K. (2016). The future of cardiovascular regenerative medicine. Circulation, 133(25), 2618-2625.

- Li, Q., Wang, P., Chen, L., Gao, H., & Wu, L. (2016). Acute toxicity and histopathological effects of naproxen in zebrafish (Danio rerio) early life stages. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Wang. Y., Mai, Y., Li, H., Wang, Z., Xu, J., & He, X. (2020). Health Benefits of the Flavonoids from Onion: Constituents and Their Pronounced Antioxidant and Anti-neuroinflammatory Capacities. J Agric Food Chem. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhu, Y., Zhao, X., Zhao, L., Wang, Y., & Yang, Z. (2022). Screening of anti-heart failure active compounds from fangjihuangqi decoction in verapamil-induced zebrafish model by anti-heart failure index approach. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 999950.

- Li, S., Liu, H., Li, Y., Qin, X., Li, M., Shang, J., & Zhou, M. (2021). Shen-Yuan-Dan capsule attenuates verapamil-induced zebrafish heart failure and exerts antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects via reactive oxygen species–induced NF-κB pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 626515.

- Liu, W., Di Giorgio, C., Lamidi, M., Elias, R., Ollivier, E., & De Méo, M. P. (2011). Genotoxic and clastogenic activity of saponins extracted from Nauclea bark as assessed by the micronucleus and the comet assays in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 137(1), 176-183.

- Low Wang, C. C., Hess, C. N., Hiatt, W. R., & Goldfine, A. B. (2016). Clinical update: cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus–mechanisms, management, and clinical considerations. Circulation, 133(24), 2459-2502.

- Mahmood, A., Eqan, M., Pervez, S., Javed, R., Ullah, R., Islam, A., & Rafiq, M. (2021). Drugs Resistance in Heart Diseases. Biochemistry of Drug Resistance, 295-334.

- Mai Sayed Fouad, Mosad A. Ghareeb, Ahmed A. Hamed, Esraa A. Aidy, Jioji Tabudravu, Ahmed M. Sayed, Mohamed A. Tammam, Mai Ali Mwaheb. (2024). Exploring the antioxidant, anticancer and antimicrobial potential of Amaranthus viridis L. collected from Fayoum depression: Phytochemical, and biological aspects, South African Journal of Botany,Volume 166,Pages 297-310.

- Meid, H., & S Haddad, P. (2017). The antidiabetic potential of quercetin: underlying mechanisms. Current medicinal chemistry, 24(4), 355-364.

- Minamino, T. (2012). Cardioprotection From Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury–Basic and Translational Research–. Circulation Journal, 76(5), 1074-1082.

- Mohamad Shariff, N. F. S., Singgampalam, T., Ng, C. H., & Kue, C. S. (2020). Antioxidant activity and zebrafish teratogenicity of hydroalcoholic Moringa oleifera L. leaf extracts. British Food Journal, 122(10), 3129-3137.

- Mohs, R. C., & Greig, N. H. (2017). Drug discovery and development: Role of basic biological research. Alzheimer's & dementia (New York, N. Y.), 3(4), 651–657. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L. M., Vasques-Nóvoa, F., Ferreira, L., Pinto-do-Ó, P., & Nascimento, D. S. (2017). Restoring heart function and electrical integrity: closing the circuit. NPJ Regenerative medicine, 2(1), 9.

- Baky, M., Elsaid, M., & Farag, M. (2022). Phytochemical and biological diversity of triterpenoid saponins from family Sapotaceae: A comprehensive review. Phytochemistry, Volume 202, , 113345, ISSN 0031-9422,. [CrossRef]

- Murino-Rafacho, B. P., Portugal dos Santos, P., Gonçalves, A. de F., Fernandes, A. A. H., Okoshi, K., Chiuso-Minicucci, F., Rupp de Paiva, S. A. (2017). Rosemary supplementation (Rosmarinus oficinallis L.) attenuates cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0177521. [CrossRef]

- Narumanchi, S., Wang, H., Perttunen, S., Tikkanen, I., Lakkisto, P., & Paavola, J. Zebrafish Heart Failure Models. (2021). Front Cell Dev Biol.20;9:662583. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C., & Cheng-Lai, A. (2013). The polypill: a potential global solution to cardiovascular disease. Cardiology in review, 21(1), 49-54.

- Nowak, D., Gośliński, M., Wojtowicz, E., & Przygoński, K. (2018). Antioxidant Properties and Phenolic Compounds of Vitamin C-Rich Juices. J Food Sci. [CrossRef]

- Nowbar, A. N., Gitto, M., Howard, J. P., Francis, D. P., & Al-Lamee, R. (2019). Mortality from ischemic heart disease: Analysis of data from the World Health Organization and coronary artery disease risk factors From NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Circulation: cardiovascular quality and outcomes, 12(6), e005375.

- Omondi, J. O. (2017). Phenotypic variation in morphology, yield and seed quality in selected accessions of leafy Amaranths (Doctoral dissertation, Maseno University).

- Pearson, T. A., Mensah, G. A., Alexander, R. W., Anderson, J. L., Cannon III, R. O., Criqui, M. & Vinicor, F. (2003). Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. circulation, 107(3), 499-511.

- Peter, K., & Gandhi, P. (2017). Rediscovering the therapeutic potential of Amaranthus species: A review. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(3), 196-205.

- Pichaivel, M., Dhandayuthapani, D., Porwal, O., Sharma, P. K., & Manickam, D. (2022). Phytochemical And Pharmacological Evaluation Of Hydroalcoholic Extract Of Amaranthus Viridis Linn. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 2250-2269.

- Pirdhankar, M. S., Sadamate, P. S., & Tasgaonkar, D. R. (2023). Cardioprotective Herbal Plants: A Review. International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology, 11(3), 1114-1118.

- Plein, S., Greenwood, J. P., Ridgway, J. P., Cranny, G., Ball, S. G., & Sivananthan, M. U. (2004). Assessment of non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 44(11), 2173-2181.

- Poon, K. L., & Brand, T. (2013). The zebrafish model system in cardiovascular research: A tiny fish with mighty prospects. Global Cardiology Science and Practice, 2013(1), 4.

- Pruthvi, N. (2010). Phytochemical Studies And Evaluation Of Leaves Of Amaranthus Viridis (Amaranthaceae) For Antidiabetic Activity (Doctoral dissertation, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences (India).

- Raggi, P., Genest, J., Giles, J. T., Rayner, K. J., Dwivedi, G., Beanlands, R. S., & Gupta, M. (2018). Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and therapeutic interventions. Atherosclerosis, 276, 98-108.

- Rajendran P, Rengarajan T, Thangavel J, Nishigaki Y, Sakthisekaran D, Sethi G, Nishigaki I. The vascular endothelium and human diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2013 Nov 9;9(10):1057-69. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, L., & Piferrer, F. (2014). The zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a model organism, with emphasis on applications for finfish aquaculture research. Reviews in Aquaculture, 6(4), 209-240.

- Rotariu, D., Babes, E. E., Tit, D. M., Moisi, M., Bustea, C., Stoicescu, M., & Bungau, S. G. (2022). Oxidative stress–Complex pathological issues concerning the hallmark of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 152, 113238.

- Salvamani, S., Gunasekaran, B., Shukor, M. Y., Shaharuddin, N. A., Sabullah, M. K., & Ahmad, S. A. (2016). Anti-HMG-CoA reductase, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of Amaranthus viridis leaf extract as a potential treatment for hypercholesterolemia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2016.

- Sant KE, Timme-Laragy AR. Zebrafish as a Model for Toxicological Perturbation of Yolk and Nutrition in the Early Embryo. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2018 Mar;5(1):125-133. [CrossRef]

- Santoso, F., Farhan, A., Castillo, A. L., Malhotra, N., Saputra, F., Kurnia, K. A., & Hsiao, C. D. (2020). An overview of methods for cardiac rhythm detection in zebrafish. Biomedicines, 8(9), 329.

- Sapna, F. N. U., Raveena, F. N. U., Chandio, M., Bai, K., Sayyar, M., Varrassi, G., & Mohamad, T. (2023). Advancements in Heart Failure Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review of Emerging Therapies. Cureus, 15(10).

- Saravanan, G., & Ponmurugan, P. (2012). Amaranthus viridis Linn., a common spinach, modulates C-reactive protein, protein profile, ceruloplasmin and glycoprotein in experimental induced myocardial infarcted rats. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 92(12), 2459-2464.

- Sarker, U., & Oba, S. (2019). Nutraceuticals, antioxidant pigments, and phytochemicals in the leaves of Amaranthus spinosus and Amaranthus viridis weedy species. Scientific reports, 9(1), 20413.

- Schwitter, J., Wacker, C. M., Wilke, N., Al-Saadi, N., Sauer, E., Huettle, K., & MR-IMPACT Investigators. (2013). MR-IMPACT II: Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Myocardial Perfusion Assessment in Coronary artery disease Trial: perfusion-cardiac magnetic resonance vs. single-photon emission computed tomography for the detection of coronary artery disease: a comparative multicentre, multivendor trial. European heart journal, 34(10), 775-781.

- Sedighi, M., Faghihi, M., Rafieian-Kopaei, M., Rasoulian, B., & Nazari, A. (2019). Cardioprotective Effect of Ethanolic Leaf Extract of Melissa Officinalis L Against Regional Ischemia-Induced Arrhythmia and Heart Injury after Five Days of Reperfusion in Rats. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research: IJPR, 18(3), 1530–1542. [CrossRef]

- Sedmera, D., Reckova, M., DeAlmeida, A., Sedmerova, M., Biermann, M., Volejnik, J., & Thompson, R. P. (2003). Functional and morphological evidence for a ventricular conduction system in zebrafish and Xenopus hearts. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 284(4), H1152-H1160.

- Sessa, F., Anna, V., Messina, G., Cibelli, G., Monda, V., Marsala, G., ... & Salerno, M. (2018). Heart rate variability as predictive factor for sudden cardiac death. Aging (Albany NY), 10(2), 166.

- Shah, S. M. A., Akram, M., Riaz, M., Munir, N., & Rasool, G. (2019). Cardioprotective potential of plant-derived molecules: a scientific and medicinal approach. Dose-response, 17(2), 1559325819852243.

- Shen, C., & Zuo, Z. (2020). Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an excellent vertebrate model for the development, reproductive, cardiovascular, and neural and ocular development toxicity study of hazardous chemicals. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(35), 43599-43614.

- Singh, G. M., Danaei, G., Farzadfar, F., Stevens, G. A., Woodward, M., Wormser, D., & Prospective Studies Collaboration (PSC). (2013). The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a pooled analysis. PloS one, 8(7), e65174.

- Sogorski, A., Spindler, S., Wallner, C., Dadras, M., Wagner, J. M., Behr, B., & Kolbenschlag, J. (2021). Optimizing remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) of cutaneous microcirculation in humans: number of cycles and duration of acute effects. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 74(4), 819-827.

- Srivastava, D., & Baldwin, H. S. (2001). Molecular determinants of cardiac development. Moss and Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Hugh D. Allen, Howard P. Gutgesell, et al, 3-23.

- Stajer, D., Bervar, M., & Horvat, M. (2001). Cardiogenic shock following a single therapeutic oral dose of verapamil. International journal of clinical practice, 55(1), 69–70.

- Stevens, C. M., Rayani, K., Genge, C. E., Singh, G., Liang, B., Roller, J. M., & Tibbits, G. F. (2016). Characterization of zebrafish cardiac and slow skeletal troponin C paralogs by MD simulation and ITC. Biophysical journal, 111(1), 38-49.

- Sullivan-Brown, J., Bisher, M. E., & Burdine, R. D. (2011). Embedding, serial sectioning and staining of zebrafish embryos using JB-4 resin. Nature protocols, 6(1), 46–55. [CrossRef]

- Swathy, M., & Saruladha, K. (2022). A comparative study of classification and prediction of Cardio-vascular diseases (CVD) using Machine Learning and Deep Learning techniques. ICT Express, 8(1), 109-116.

- Tavares, B., & Lopes, S. S. (2013). The importance of Zebrafish in biomedical research. Acta medica portuguesa, 26(5), 583-592.

- Timmis, A., Townsend, N., Gale, C. P., Torbica, A., Lettino, M., Petersen, S. E., & Vardas, P. (2020). European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2019. European heart journal, 41(1), 12-85.

- Timmis, A., Vardas, P., Townsend, N., Torbica, A., Katus, H., De Smedt, D., & Achenbach, S. (2022). European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. European Heart Journal, 43(8), 716-799.

- Ullah, A., Munir, S., Badshah, S.L., Khan, N., Ghani, L., Poulson, B.G., Emwas, A.H, & Jaremko, M. (2020). Important Flavonoids and Their Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules. [CrossRef]

- Valaei, K., Taherkhani, S., Arazi, H., & Suzuki, K. (2021). Cardiac Oxidative Stress and the Therapeutic Approaches to the Intake of Antioxidant Supplements and Physical Activity. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. W., Huttner, I. G., Santiago, C. F., Kesteven, S. H., Yu, Z. Y., Feneley, M. P., & Fatkin, D. (2017). Standardized echocardiographic assessment of cardiac function in normal adult zebrafish and heart disease models. Disease models & mechanisms, 10(1), 63-76.

- Ward, E., Jemal, A., Cokkinides, V., Singh, G. K., Cardinez, C., Ghafoor, A., & Thun, M. (2004). Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 54(2), 78-93.

- Weichao Zhao, Yuna Chen, Nan Hu, Dingxin Long, Yi Cao. (2042). The uses of zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an in vivo model for toxicological studies: A review based on bibliometrics, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, Volume 272, 2024, 116023, ISSN 0147-6513. [CrossRef]

- White, R., Rose, K., & Zon, L. (2013). Zebrafish cancer: the state of the art and the path forward. Nature Reviews Cancer, 13(9), 624-636.

- Wiciński, M., Socha, M., Walczak, M., Wódkiewicz, E., Malinowski, B., Rewerski, S., & Pawlak-Osińska, K. (2018). Beneficial effects of resveratrol administration—Focus on potential biochemical mechanisms in cardiovascular conditions. Nutrients, 10(11), 1813.

- Wiegand, J., Avila-Barnard, S., Nemarugommula, C., Lyons, D., Zhang, S., Stapleton, H.M., & Volz, D.C. (2023). Triphenyl phosphate-induced pericardial edema in zebrafish embryos is dependent on the ionic strength of exposure media. Environ Int. ;172:107757. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. S., Walker, R. J., & Egede, L. E. (2016). Achieving equity in an evolving healthcare system: opportunities and challenges. The American journal of the medical sciences, 351(1), 33-43.

- World Health Organization. (2007). Prevention of cardiovascular disease. Pocket guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. Africa: Who/Ish cardiovascular risk prediction charts for the African region. World Health Organization.

- Zhu, X.Y., Wu, S.Q., Guo, S.Y., Xia, B., Li, P., & Li, C.Q. (2018). A Zebrafish Heart Failure Model for Assessing Therapeutic Agents. Zebrafish.243-253.http://doi.org/10.1089/zeb.2017.1546.

- Yumnamcha, T., Nongthomba, U., & Devi, M. D. (2014). Phytochemical screening and evaluation of genotoxicity and acute toxicity of aqueous extract of Croton tiglium L. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(1), 2250-3153.

- Yumnamcha, T., Roy, D., Devi, M. D., & Nongthomba, U. (2015). Evaluation of developmental toxicity and apoptotic induction of the aqueous extract of Millettia pachycarpa using zebrafish as model organism. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry, 97(10), 1363-1381.

- Zahir, S., Pal, T. K., Sengupta, A., Biswas, S., Bar, S., & Bose, S. (2021). Determination of lethal concentration fifty (LC50) of whole plant ethanolic extract of Amaranthus viridis, Cynodon dactylon & Aerva sanguinolenta on Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Int J Pharm Sci & Res 2021; 12(4): 2394-04. [CrossRef]

- Zahra, M., Abrahamse, H., & George, B.P. (2021). Flavonoids: Antioxidant Powerhouses and Their Role in Nanomedicine. Antioxidants (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Zainol-Abidin, I.Z., Fazry, S., Jamar, N.H., Ediwar, Dyari, H.R., Zainal-Ariffin, Z., Johari, A.N., Ashaari, N.S, Johari NA, Megat Abdul Wahab R, Zainal Ariffin SH. (2020). The effects of Piper sarmentosum aqueous extracts on zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos and caudal fin tissue regeneration. Sci Rep. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).