Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Epidemiology

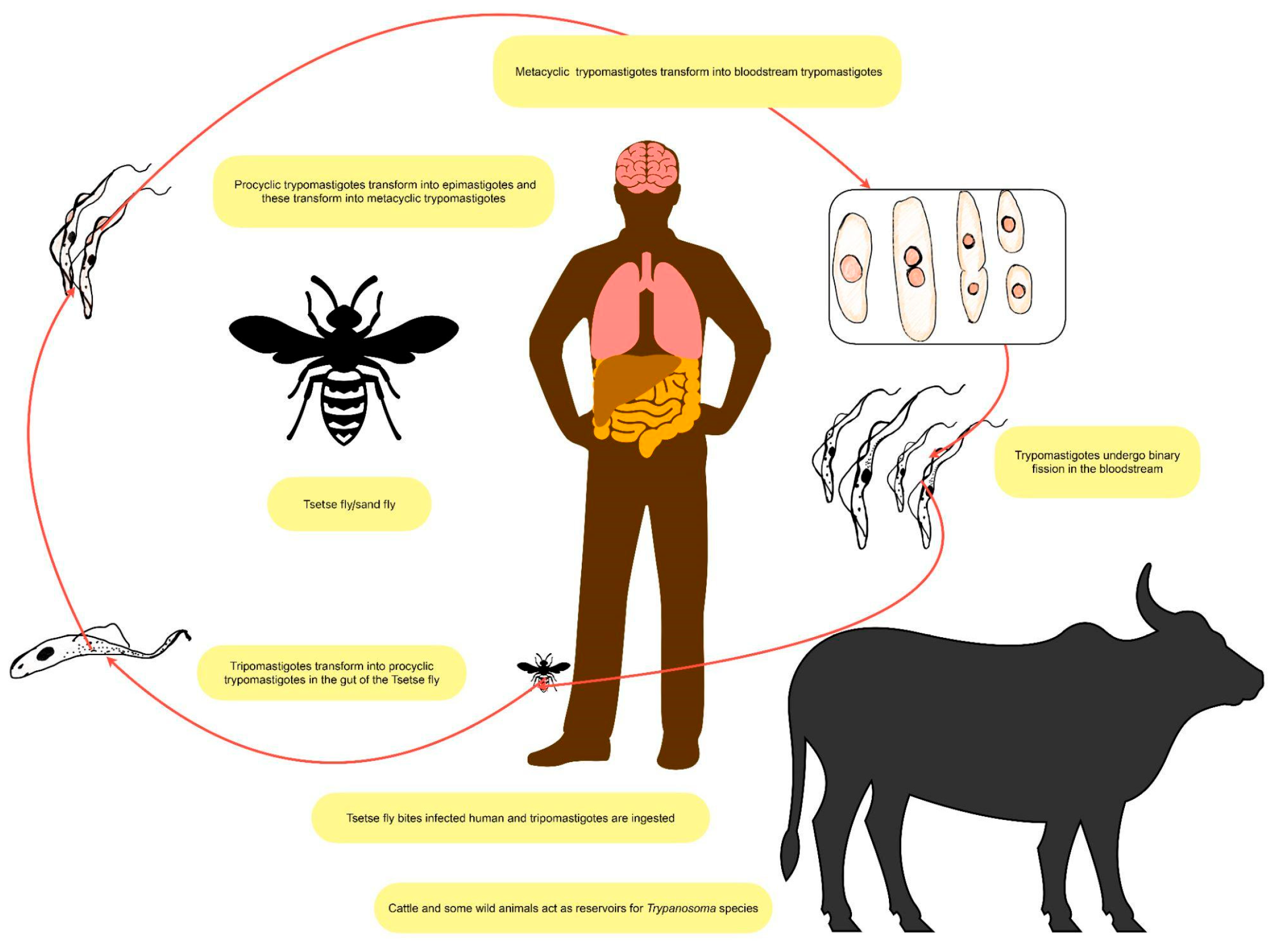

1.2. Trypanosoma Brucei Parasitology

1.3. Sleep Disorders

2. Pathophysiology of Sleep Disorders in African Trypanosomiasis

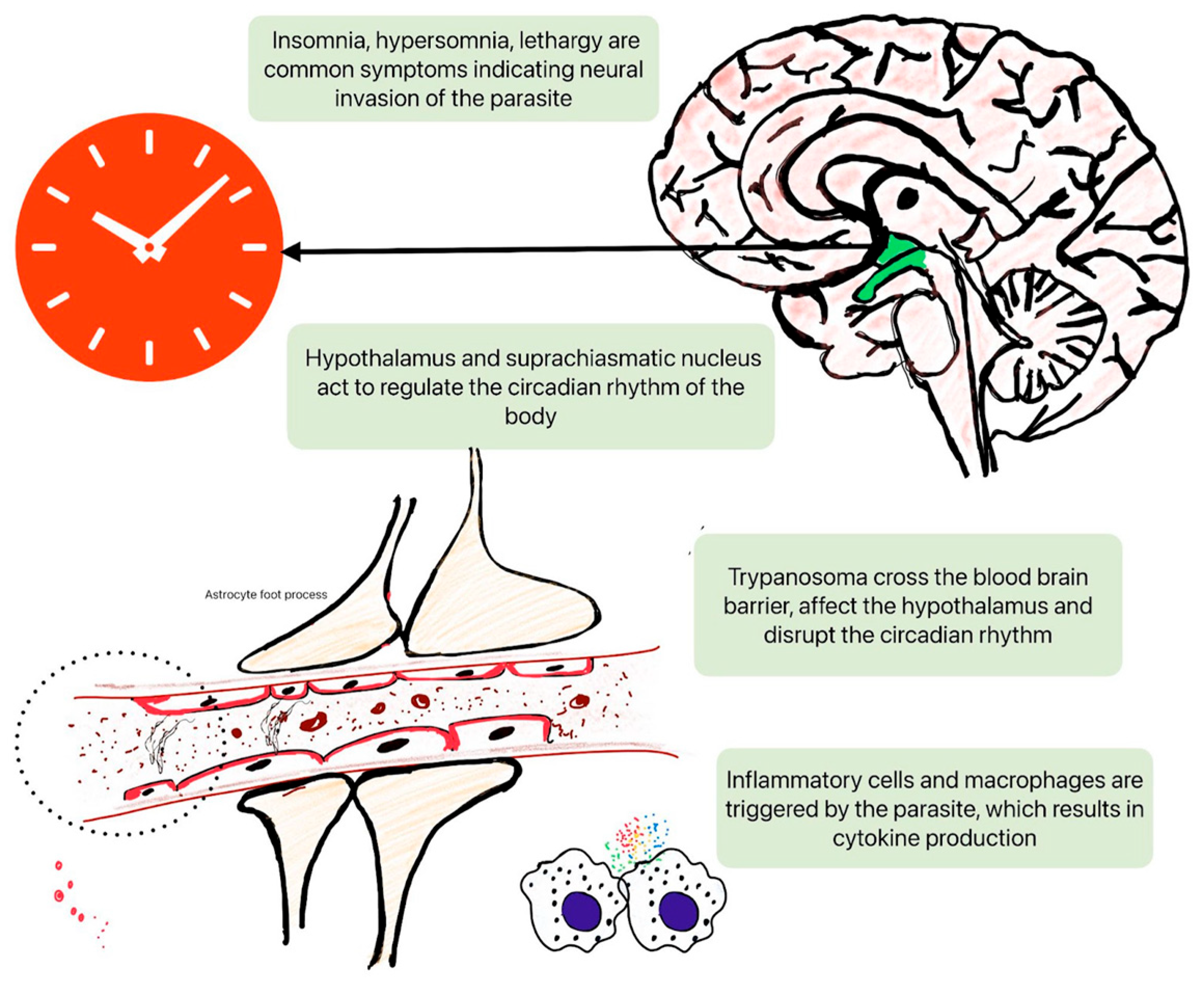

2.1. Disruption of Circadian Rhythms

2.2. Neurotransmitter Imbalance

2.3. Immune System Modulation

3. Clinical Manifestations of Sleep Disorders in African Trypanosomiasis

3.1. Subtypes of African Trypanosomiasis

3.2. Sleep Disturbances

3.3. Differential Diagnosis Challenges

4. Diagnostic Approaches

4.1. Polysomnography and Actigraphy

4.2. Biomarkers and Laboratory Testing

4.3. Neuroimaging Techniques

5. Management Strategies

5.1. Pharmacological Interventions

5.2. Non-Pharmacological Therapies

6. Impact on Public Health and Socioeconomic Burden

6.1. Global Health Implications

6.2. Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Disease Burden

7. Psychological Impact of Sleep Disorders

8. Prevention and Control Measures

8.1. Vector Control Strategies

8.2. Public Health Education and Awareness

9. Future Perspectives

9.1. Future Research Directions

9.2. Clinical Implications and Challenges

10. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Büscher, P.; Cecchi, G.; Jamonneau, V.; Priotto, G. Human African Trypanosomiasis. The Lancet 2017, 390, 2397–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, R.; Blum, J.; Chappuis, F.; Burri, C. Human African Trypanosomiasis. The Lancet 2010, 375, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Martínez, Y.; Kouamé, M.G.; Bongomin, F.; Lakoh, S.; Henao-Martínez, A.F. Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness)—Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Current Tropical Medicine Reports 2023, 10, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J. Epidemiology of African Sleeping Sickness.; Wiley Online Library, 1974; Vol. 20, pp. 29–50.

- Okwelum, N.; Onagbesan, O.; Shittu, O.; Famakinde, S.; Bemji, M.; Osinowo, O. PREVALENCE OF SAVANNAH-TYPE TRYPANOSOMA CONGOLENSE IN CATTLE IN SOUTH-WESTERN NIGERIA. Nigerian Journal of Animal Production 2024, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutto, J.J.; Osano, O.; Thuranira, E.G.; Kurgat, R.K.; Odenyo, V.A.O. Socio-Economic and Cultural Determinants of Human African Trypanosomiasis at the Kenya - Uganda Transboundary. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013, 7, e2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Grace, D.; Kock, R.; Alonso, S.; Rushton, J.; Said, M.Y.; McKeever, D.; Mutua, F.; Young, J.; McDermott, J.; et al. Zoonosis Emergence Linked to Agricultural Intensification and Environmental Change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 8399–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Upadhyay, R.K. Global Effect of Climate Change on Seasonal Cycles, Vector Population and Rising Challenges of Communicable Diseases: A Review. Journal of Atmospheric Science Research 2023, 6, 21–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikwai, C.; Ngeiywa, M. Review on the Socio-Economic Impacts of Trypanosomiasis. 2022.

- John, M.A.; Bankole, I.; Ajayi-Moses, O.; Ijila, T.; Jeje, O.; Lalit, P. Relevance of Advanced Plant Disease Detection Techniques in Disease and Pest Management for Ensuring Food Security and Their Implication: A Review. American Journal of Plant Sciences 2023, 14, 1260–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.S. Parasites. Diagnostic Microbiology of the Immunocompromised Host 2008, 283–330. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, G.A.; Vogel, P.; Balczun, C. Parasite-Vector Interactions. Molecular Parasitology: Protozoan Parasites and their Molecules 2016, 431–489.

- Rodgers, J. Trypanosomiasis and the Brain. Parasitology 2010, 137, 1995–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.R.; McCulloch, R.; Morrison, L.J. The Within-Host Dynamics of African Trypanosome Infections. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015, 370, 20140288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickerman, K. Antigenic Variation in African Trypanosomes.; Wiley Online Library, 1974; pp. 53–80.

- Tesoriero, C.; Del Gallo, F.; Bentivoglio, M. Sleep and Brain Infections. Brain Res Bull 2019, 145, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensson, K.; Nygård, M.; Bertini, G.; Bentivoglio, M. African Trypanosome Infections of the Nervous System: Parasite Entry and Effects on Sleep and Synaptic Functions. Prog Neurobiol 2010, 91, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imeri, L.; Opp, M.R. How (and Why) the Immune System Makes Us Sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakroborty, N.K.; Baksi, S.; Bhattacharya, A. Cognitive Impairment in Parasitic Protozoan Infection. In Pathobiology of Parasitic Protozoa: Dynamics and Dimensions; Springer, 2023; pp. 61–94.

- MOTIVALA, S.J.; IRWIN, M. Immunologic Changes.

- Bouteille, B.; Dumas, M. Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. In Tropical Neurology; CRC Press, 2003; pp. 325–343.

- Feuth, T. Interactions between Sleep, Inflammation, Immunity and Infections: A Narrative Review. Immun Inflamm Dis 2024, 12, e70046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, V.; Grau, G.E. 11 Cytokines and Defense and Pathology of the CNS. Cytokines and the CNS 2005, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Maestroni, G.J.M. Role of Melatonin in Viral, Bacterial and Parasitic Infections. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, R.M.; van Eden, C.G.; Goncharuk, V.D.; Kalsbeek, A. The Biological Clock Tunes the Organs of the Body: Timing by Hormones and the Autonomic Nervous System. J Endocrinol 2003, 177, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stibbs, H.H. Neurochemical and Activity Changes in Rats Infected with Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense. J Parasitol 1984, 70, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montague, P.; Bradley, B.; Rodgers, J.; Kennedy, P.G.E. Microarray Profiling Predicts Early Neurological and Immune Phenotypic Traits in Advance of CNS Disease during Disease Progression in Trypanosoma. b. Brucei Infected CD1 Mouse Brains. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021, 15, e0009892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-Filho, A.J.M.; Macedo, D.S.; de Lucena, D.F.; Maes, M. Shared Microglial Mechanisms Underpinning Depression and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Their Comorbidities. Behav Brain Res 2019, 372, 111975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamour, S.D.; Alibu, V.P.; Holmes, E.; Sternberg, J.M. Metabolic Profiling of Central Nervous System Disease in Trypanosoma Brucei Rhodesiense Infection. J Infect Dis 2017, 216, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimgampalle, M.; Chakravarthy, H.; Sharma, S.; Shree, S.; Bhat, A.R.; Pradeepkiran, J.A.; Devanathan, V. Neurotransmitter Systems in the Etiology of Major Neurological Disorders: Emerging Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 89, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besedovsky, L.; Lange, T.; Haack, M. The Sleep-Immune Crosstalk in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1325–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, J.M.; Fang, J.; Floyd, R.A. Relationships between Sleep and Immune Function. Lung biology in health and disease 1999, 133, 427–427. [Google Scholar]

- Palagini, L.; Geoffroy, P.A.; Miniati, M.; Perugi, G.; Biggio, G.; Marazziti, D.; Riemann, D. Insomnia, Sleep Loss, and Circadian Sleep Disturbances in Mood Disorders: A Pathway toward Neurodegeneration and Neuroprogression? A Theoretical Review. CNS Spectr 2022, 27, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.F.; Chandrasegaran, P.; Sinton, M.C.; Briggs, E.M.; Otto, T.D.; Heslop, R.; Bentley-Abbot, C.; Loney, C.; de Lecea, L.; Mabbott, N.A.; et al. Single Cell and Spatial Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Microglia-Plasma Cell Crosstalk in the Brain during Trypanosoma Brucei Infection. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, M.R.; Gibbons, A.J. Neuroinflammation, Sleep, and Circadian Rhythms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 853096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steverding, D. Sleeping Sickness and Nagana Disease Caused by Trypanosoma Brucei. Arthropod borne diseases 2017, 277–297. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, S.; Lanteri, P.; Durando, P.; Magnavita, N.; Sannita, W.G. Co-Morbidity, Mortality, Quality of Life and the Healthcare/Welfare/Social Costs of Disordered Sleep: A Rapid Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte-Sucre, A. An Overview of Trypanosoma Brucei Infections: An Intense Host-Parasite Interaction. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, J.R.; Simarro, P.P.; Diarra, A.; Jannin, J.G. Epidemiology of Human African Trypanosomiasis. Clin Epidemiol 2014, 6, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checchi, F.; Piola, P.; Ayikoru, H.; Thomas, F.; Legros, D.; Priotto, G. Nifurtimox plus Eflornithine for Late-Stage Sleeping Sickness in Uganda: A Case Series. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2007, 1, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pépin, J.; Méda, H.A. The Epidemiology and Control of Human African Trypanosomiasis. Adv Parasitol 2001, 49, 71–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J.; Ortiz, J.F.; Fabara, S.P.; Eissa-Garcés, A.; Reddy, D.; Collins, K.D.; Tirupathi, R. Efficacy and Toxicity of Fexinidazole and Nifurtimox Plus Eflornithine in the Treatment of African Trypanosomiasis: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e16881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisapel, N. Sleep and Sleep Disturbances: Biological Basis and Clinical Implications. Cell Mol Life Sci 2007, 64, 1174–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagni, R.; Novara, R.; Minardi, M.L.; Frallonardo, L.; Panico, G.G.; Pallara, E.; Cotugno, S.; Ascoli Bartoli, T.; Guido, G.; De Vita, E. Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness): Current Knowledge and Future Challenges. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2023, 4, 1087003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.G.E. The Continuing Problem of Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness). Ann Neurol 2008, 64, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G.; Wille, M.; Hemels, M.E. Short- and Long-Term Health Consequences of Sleep Disruption. Nat Sci Sleep 2017, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishir, M.; Bhat, A.; Essa, M.M.; Ekpo, O.; Ihunwo, A.O.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mohan, S.K.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Ray, B.; Tuladhar, S.; et al. Sleep Deprivation and Neurological Disorders. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 5764017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, J.M. Sleep-Related Problems in Common Medical Conditions. Chest 2009, 135, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamo, F.Z.; Djiogue, S.; Awounfack, C.F.; Nange, A.C.; Njamen, D. Neurological Disorders: The Use of Traditional Medicine in Cameroon. thought 2024, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozko, V.; Bondarenko, A.; Katsapov, D.; Krasnov, M.; Nikitina, N.; Gradil, G. Tropical Diseases. 2007.

- Walker, M.; Kublin, J.G.; Zunt, J.R. Parasitic Central Nervous System Infections in Immunocompromised Hosts: Malaria, Microsporidiosis, Leishmaniasis, and African Trypanosomiasis. Clin Infect Dis 2006, 42, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, A.; Meltzer, E.; Leshem, E.; Dickstein, Y.; Stienlauf, S.; Schwartz, E. The Changing Epidemiology of Human African Trypanosomiasis among Patients from Nonendemic Countries--1902-2012. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, F.; Loutan, L.; Simarro, P.; Lejon, V.; Büscher, P. Options for Field Diagnosis of Human African Trypanosomiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005, 18, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boraschi, D.; Abebe Alemayehu, M.; Aseffa, A.; Chiodi, F.; Chisi, J.; Del Prete, G.; Doherty, T.M.; Elhassan, I.; Engers, H.; Gyan, B.; et al. Immunity against HIV/AIDS, Malaria, and Tuberculosis during Co-Infections with Neglected Infectious Diseases: Recommendations for the European Union Research Priorities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008, 2, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BENTIVOGLIO, M.; BERTINI, G.; GRASSI-ZUCCONI, G.; ETET, P.S. Sleep Research in Africa: From Basic Neuroscience and Clinical Investigations to Health Management in Developing Countries.; Wiley Online Library, 2010; p. 6.

- Kayabekir, M. Sleep Physiology and Polysomnogram, Physiopathology and Symptomatology in Sleep Medicine. Updates in Sleep Neurology and Obstructive Sleep Apnea 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buguet, A.; Bourdon, L.; Bouteille, B.; Cespuglio, R.; Vincendeau, P.; Radomski, M.W.; Dumas, M. The Duality of Sleeping Sickness: Focusing on Sleep. Sleep Med Rev 2001, 5, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Zhang, W.E.; Ortiz, J.; Pouriyeh, S. Non-Invasive Techniques for Monitoring Different Aspects of Sleep: A Comprehensive Review. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare (HEALTH) 2022, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.G.E. The Evolving Spectrum of Human African Trypanosomiasis. QJM 2024, 117, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincendeau, P.; Bouteille, B. Immunology and Immunopathology of African Trypanosomiasis. An Acad Bras Cienc 2006, 78, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, L.; De Witte, J.; Victor, B.; Vermeiren, L.; Zimic, M.; Brandt, J.; Geysen, D. Specific Detection and Identification of African Trypanosomes in Bovine Peripheral Blood by Means of a PCR-ELISA Assay. Vet Parasitol 2009, 164, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappuis, F.; Stivanello, E.; Adams, K.; Kidane, S.; Pittet, A.; Bovier, P.A. Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosomiasis (CATT) End-Dilution Titer and Cerebrospinal Fluid Cell Count as Predictors of Human African Trypanosomiasis (Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense) among Serologically Suspected Individuals in Southern Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004, 71, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desquesnes, M.; Dávila, A.M.R. Applications of PCR-Based Tools for Detection and Identification of Animal Trypanosomes: A Review and Perspectives. Vet Parasitol 2002, 109, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dea-Ayuela, M.A.; Galiana-Roselló, C.; Lalatsa, A.; Serrano, D.R. Applying Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) in the Diagnosis of Malaria, Leishmaniasis and Trypanosomiasis as Point-of-Care Tests (POCTs). Curr Top Med Chem 2018, 18, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adung’a, V.; Jebet, C.; John, T.; Masiga, D.; John, O.; Field, M.; Matovu, E.; Orindi, B. Roles of Cytokines in Modulating Trypanosoma Brucei Rhodesiense Infection Outcomes in Vervet Monkeys. 2024.

- Villanueva, M.S. Trypanosomiasis of the Central Nervous System. Semin Neurol 1993, 13, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atadzhanov, M. Tropical Neurology. In Manson’s tropical diseases; Elsevier Science Ltd. Edinburgh, 2003; pp. 275–291.

- Sabbah, P.; Brosset, C.; Imbert, P.; Bonardel, G.; Jeandel, P.; Briant, J.F. Human African Trypanosomiasis: MRI. Neuroradiology 1997, 39, 708–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.K.; Clegg, A.; Brown, M.; Hyare, H. MRI Findings of the Brain in Human African Trypanosomiasis: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. BJR Case Rep 2018, 4, 20180039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivoglio, M. Trypanosomiasis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2015, 357, e465–e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Tagliazucchi, L.; Lima, C.; Venuti, F.; Malpezzi, G.; Magoulas, G.E.; Santarem, N.; Calogeropoulou, T.; Cordeiro-da-Silva, A.; Costi, M.P. Current Treatments to Control African Trypanosomiasis and One Health Perspective. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, J. Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense and Trypanosoma Brucei Rhodesiense (African Trypanosomiasis). 2010.

- Kansiime, F.; Adibaku, S.; Wamboga, C.; Idi, F.; Kato, C.D.; Yamuah, L.; Vaillant, M.; Kioy, D.; Olliaro, P.; Matovu, E. A Multicentre, Randomised, Non-Inferiority Clinical Trial Comparing a Nifurtimox-Eflornithine Combination to Standard Eflornithine Monotherapy for Late Stage Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis in Uganda. Parasit Vectors 2018, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuepfer, I.; Schmid, C.; Allan, M.; Edielu, A.; Haary, E.P.; Kakembo, A.; Kibona, S.; Blum, J.; Burri, C. Safety and Efficacy of the 10-Day Melarsoprol Schedule for the Treatment of Second Stage Rhodesiense Sleeping Sickness. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012, 6, e1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babokhov, P.; Sanyaolu, A.O.; Oyibo, W.A.; Fagbenro-Beyioku, A.F.; Iriemenam, N.C. A Current Analysis of Chemotherapy Strategies for the Treatment of Human African Trypanosomiasis. Pathog Glob Health 2013, 107, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galalain, S.; Bandiya, H.; Galalain, A.; Mohammed, Y. A Review on the Epidemiology and Burden of Neglected Tropical Diseases. SOKOTO JOURNAL OF MEDICAL LABORATORY SCIENCE (SJMLS) 2017, 49. [Google Scholar]

- FORSTER, E.B. The Theory and Practice of Psychiatry in Ghana. Am J Psychother 1962, 16, 7–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, R.S.; Tareen, K.N. Psychiatry and Tropical Diseases. Journal of Alternative Medicine Research 2016, 8, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gimonneau, G.; Rayaisse, J.-B.; Bouyer, J. 6. Integrated Control of Trypanosomosis. In Pests and vector-borne diseases in the livestock industry; Wageningen Academic, 2018; pp. 147–174 ISBN 90-8686-863-0.

- Mitra, A.K.; Mawson, A.R. Neglected Tropical Diseases: Epidemiology and Global Burden. Trop Med Infect Dis 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukachi, S.A.; Wandibba, S.; Nyamongo, I.K. The Socio-Economic Burden of Human African Trypanosomiasis and the Coping Strategies of Households in the South Western Kenya Foci. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0006002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fèvre, E.M.; Picozzi, K.; Jannin, J.; Welburn, S.C.; Maudlin, I. Human African Trypanosomiasis: Epidemiology and Control. Adv Parasitol 2006, 61, 167–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, B.; Sonar, S.; Khan, S.; Bhattacharya, J. Pandemic-Proofing: Intercepting Zoonotic Spillover Events. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.-M.; Qian, Z.-Y.; Hide, G.; Lai, D.-H.; Lun, Z.-R.; Wu, Z.-D. Human African Trypanosomiasis: The Current Situation in Endemic Regions and the Risks for Non-Endemic Regions from Imported Cases. Parasitology 2020, 147, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntire, J.M.; Bourzat, D.; Pingali, P.L. Crop-Livestock Interaction in Sub-Saharan Africa. 1992.

- Trypanosomiasis, H. On the Socio-Economic Impact of Pandemics in Africa.

- Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Nombela, N.; Alvar, J. Population Movement: A Key Factor in the Epidemiology of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Trop Med Int Health 2010, 15, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barasa, K.W. Access Barriers to Formal Health Services: Focus on Sleeping Sickness in Teso District, Western Kenya. 2012.

- Savard, J.; Ouellet, M.-C. Handbook of Sleep Disorders in Medical Conditions; Academic Press, 2019; ISBN 0-12-813015-6.

- Freeman, D.; Sheaves, B.; Waite, F.; Harvey, A.G.; Harrison, P.J. Sleep Disturbance and Psychiatric Disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molińska, M.; ZŁOTOGÓRSKA, A. Sleep Deficits and Executive Functions at Different Developmental Stages-Meta-Analysis. The Polish Journal of Aviation Medicine, Bioengineering and Psychology 2016, 22, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Giri, S.; Mallick, B.N. REM Sleep Loss-Induced Elevated Noradrenaline Could Predispose an Individual to Psychosomatic Disorders: A Review Focused on Proposal for Prediction, Prevention, and Personalized Treatment. EPMA J 2020, 11, 529–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Molyneux, D.; Amerasinghe, F.; Davies, C.; Fletcher, E.; Schofield, C.; Hougard, J.; Polson, K.; Sinkins, S.; Epstein, P. Ecosystems and Vector-Borne Disease Control. Ecosystems and human well-being: policy responses 2005, 3, 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, G.; Mutika, G.; Lovemore, D. Insecticide-Treated Cattle for Controlling Tsetse Flies (Diptera: Glossinidae): Some Questions Answered, Many Posed. Bulletin of Entomological Research 1999, 89, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torr, S.J.; Vale, G.A. Is the Even Distribution of Insecticide-Treated Cattle Essential for Tsetse Control? Modelling the Impact of Baits in Heterogeneous Environments. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011, 5, e1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, B.A. Advancing the Sterile Insect Technique for Tsetse (Diptera: Glossinidae): Exploring Alternative Radiation Sources and Protocols. 2024.

- Vreysen, M.J.B.; Seck, M.T.; Sall, B.; Bouyer, J. Tsetse Flies: Their Biology and Control Using Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management Approaches. J Invertebr Pathol 2013, 112 Suppl, S15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, U.; Dyck, V.; Mattioli, R.; Jannin, J. Potential Impact of Tsetse Fly Control Involving the Sterile Insect Technique. Sterile insect technique: Principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management 2005, 701–723.

- Meyer, A.; Holt, H.R.; Selby, R.; Guitian, J. Past and Ongoing Tsetse and Animal Trypanosomiasis Control Operations in Five African Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10, e0005247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, I. African Trypanosomiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2006, 100, 679–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabir, M.; Choolayil, A.C. Social Work with Populations Vulnerable to Neglected Tropical Diseases: Evidence and Insights from India. 2024.

- Palmer, J.J.; Surur, E.I.; Checchi, F.; Ahmad, F.; Ackom, F.K.; Whitty, C.J.M. A Mixed Methods Study of a Health Worker Training Intervention to Increase Syndromic Referral for Gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis in South Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subspecies | T. b. gambiense | T. b. rhodesiense |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Western and Central Africa | Eastern and Southern Africa |

| Epidemiology (2020) | < 100 cases. It corresponds to 95-97% of all the cases reported. | < 100 cases. It corresponds to 3-5% of all the cases reported. |

| Incidence | Young adults involved in productive activities (hunting, fishing, and cultivating) | Young adults of working age, tourists visiting areas where wildlife is preserved |

| Vector | G. palpalis and G. fuscipes | G. morsitans and G. pallidipes |

| Fly habitat | Humid; river habitat | Dry; savannah and woodland habitat |

| Reservoir | Anthropologic (humans) | Zoonotic (animals) |

| Transmission | Human/ mammalian host - tsetse fly - human | Animal - tsetse fly - animal Animal - tsetse fly - human Human - tsetse fly - human The seasonal variations in transmission linked to the density of the Glossina (higher after the rainy season) |

| Symptoms and signs | Chronic disease, lasting months to years | Acute disease lasting a few weeks |

| Mild fever, headache, personality disorder, and sleeping disorder | Severe fever, persistent headache, and multi-organ damage | |

| Rarely skin manifestations | More frequent skin manifestations. | |

| Laboratory | Screening: available. | Screening: not available. |

| Microscopy: concentration methods | Microscopy: concentration methods | |

| Staging: lumbar puncture | Staging: lumbar puncture | |

| Vaccine | No | No |

| Prognosis | If left untreated, three years of survival. | If left untreated, six to twelve months survival. |

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Indication | Adverse effects | Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoziborole | Block protein biosynthesis by inhibiting leucyl-tRNA synthetase | First and second stage | Not available | Not available |

| Eflornithine (monotherapy) | Suicide inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), inhibition of polyamine biosynthesis | Alone only in the second stage | Itching, fever, headache, abdominal pain, nausea/ vomiting, diarrhea, myelosuppression | Membrane transporter for aminoacids |

| Fexinidazole | Production of reactive amines and other metabolites with toxic effects on trypanosome | First and early second stage | Vomit/ nausea, asthenia, prolongation of QT interval | Nitroreductase mutations, possibly cross-resistance with nifurtimox |

| Melarsoprol | Formation of toxic adducts with trypanothione and alterations of the parasite’s mitotic processes through action on multiple kinases | First choice in the second stage and treatment of recurrent relapse after first-line and rescue treatments | Encephalopathic syndrome, heart failure | Membrane transporters, pentamidine cross-resistance |

| Nifurtimox/ eflornithine combination therapy | Nifurtimox promotes the generation of free radicals. Unknown combination mechanism | First choice in the severe second stage and early second stage | Gastrointestinal symptoms, headache | Nitroreductase mutations, possibly cross-resistance with fexinidazole |

| Pentamidine | Preventing replication and transcription in the kinetoplast and the nucleus-inhibition of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential | First stage | Hypotension, nausea/vomiting, hyperazotemia, diabetes mellitus | Membrane transporters, melarsoprol cross-resistance |

| Suramin | Inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase, thymidine kinase, and glycolytic enzymes | First stage | Nephrotoxicity | Variant surface glycoprotein |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).