Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

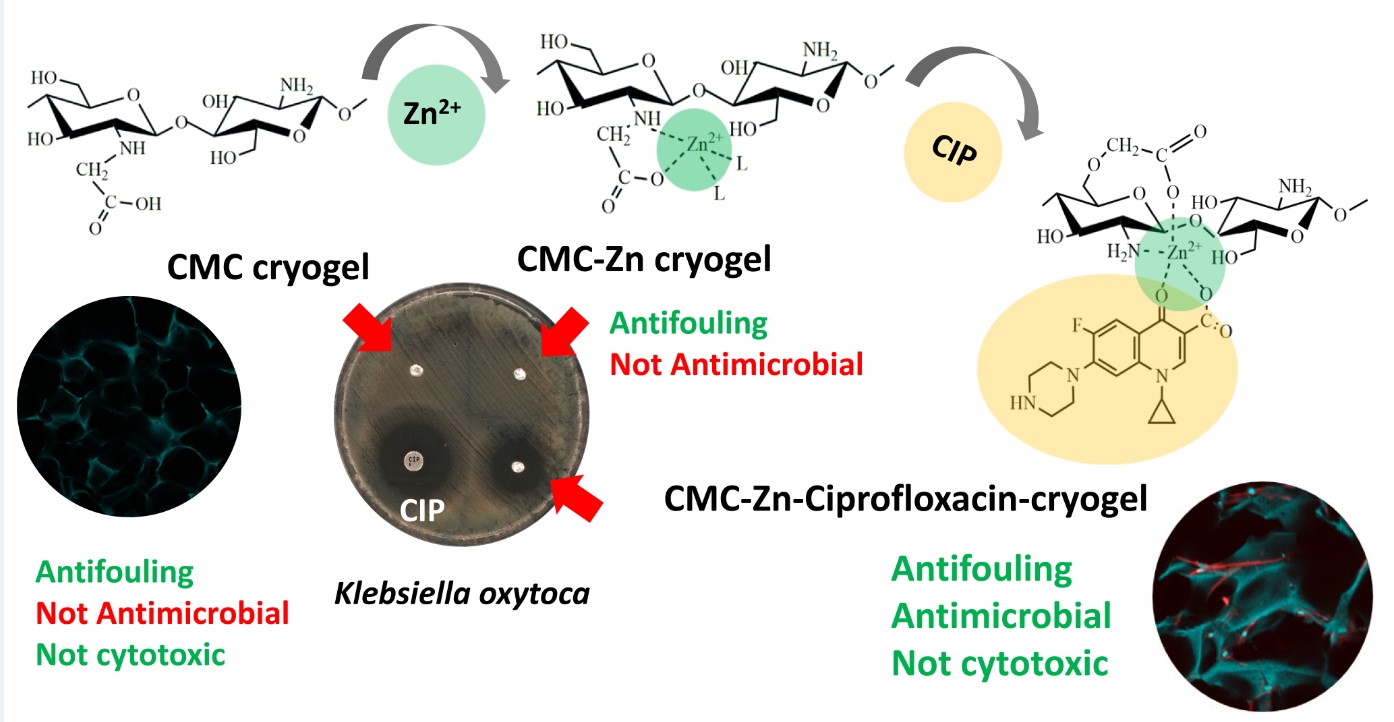

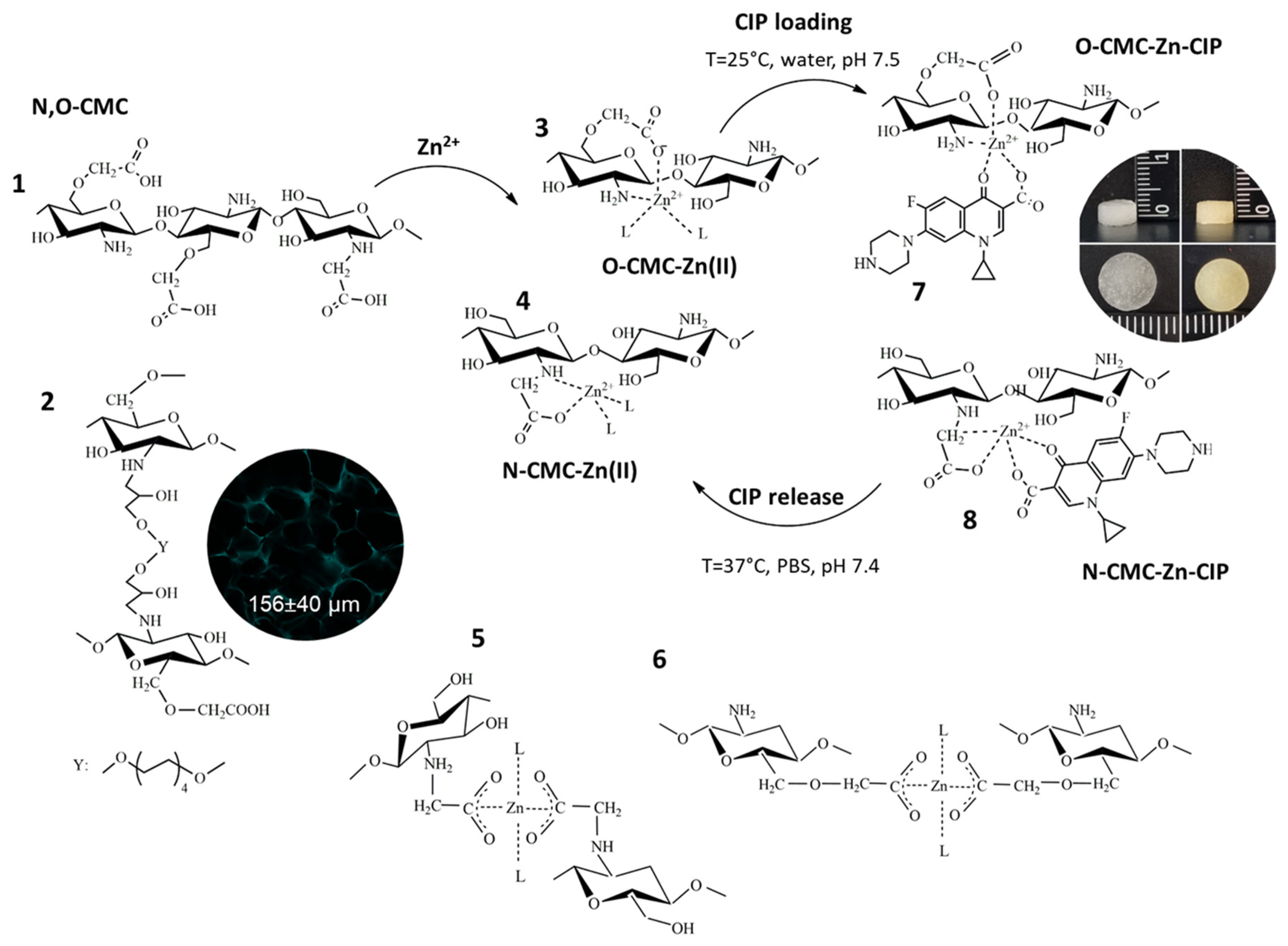

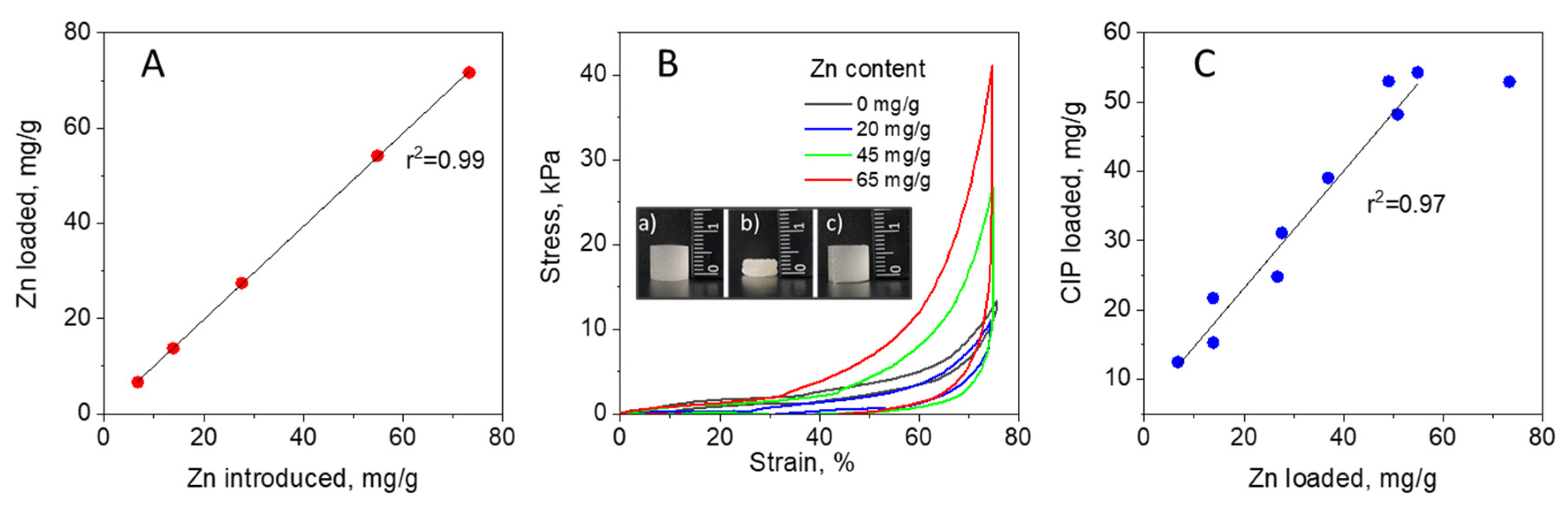

2.1. Fabrication of CMC-Zn and CMC-Zn-CIP Cryogels

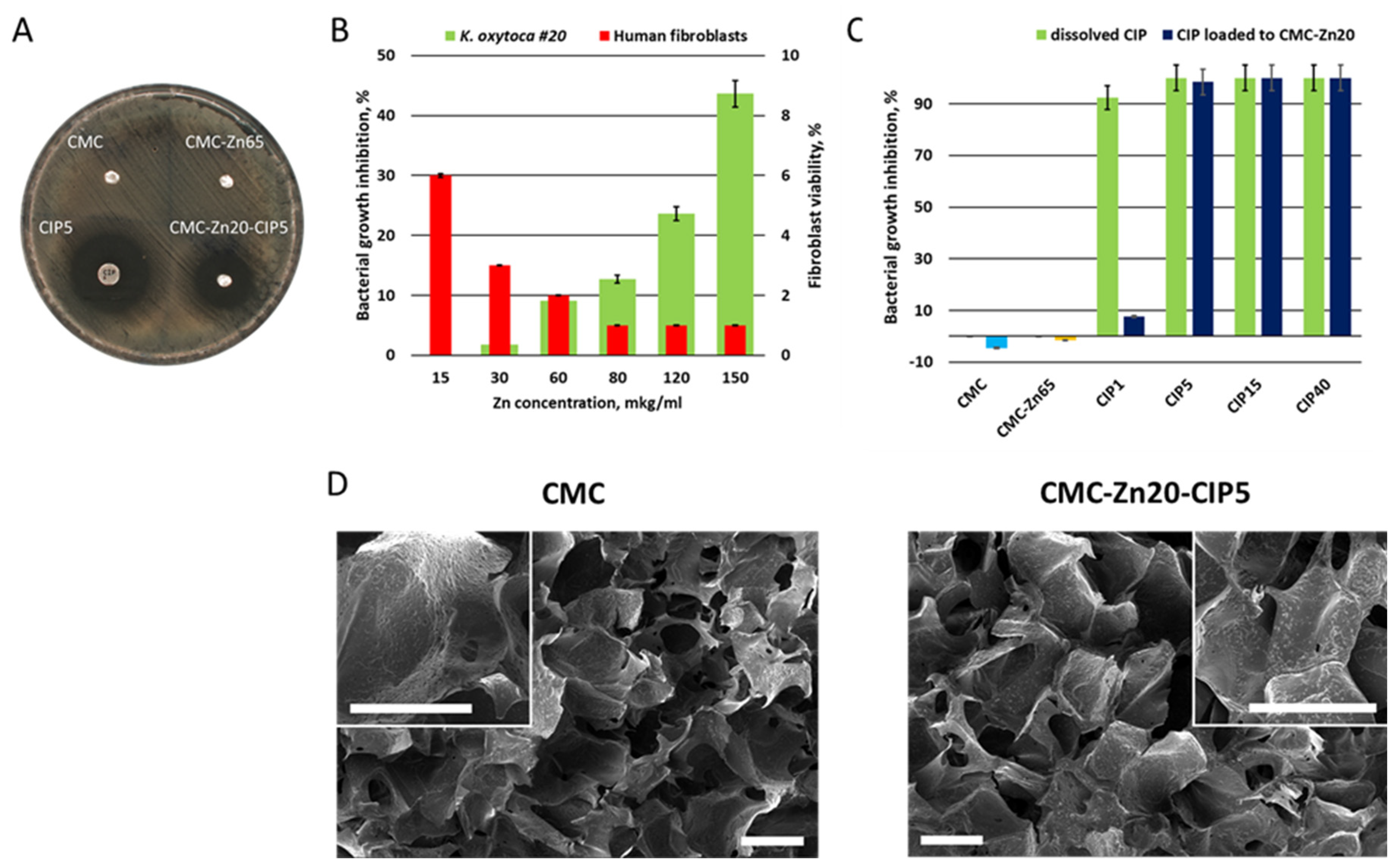

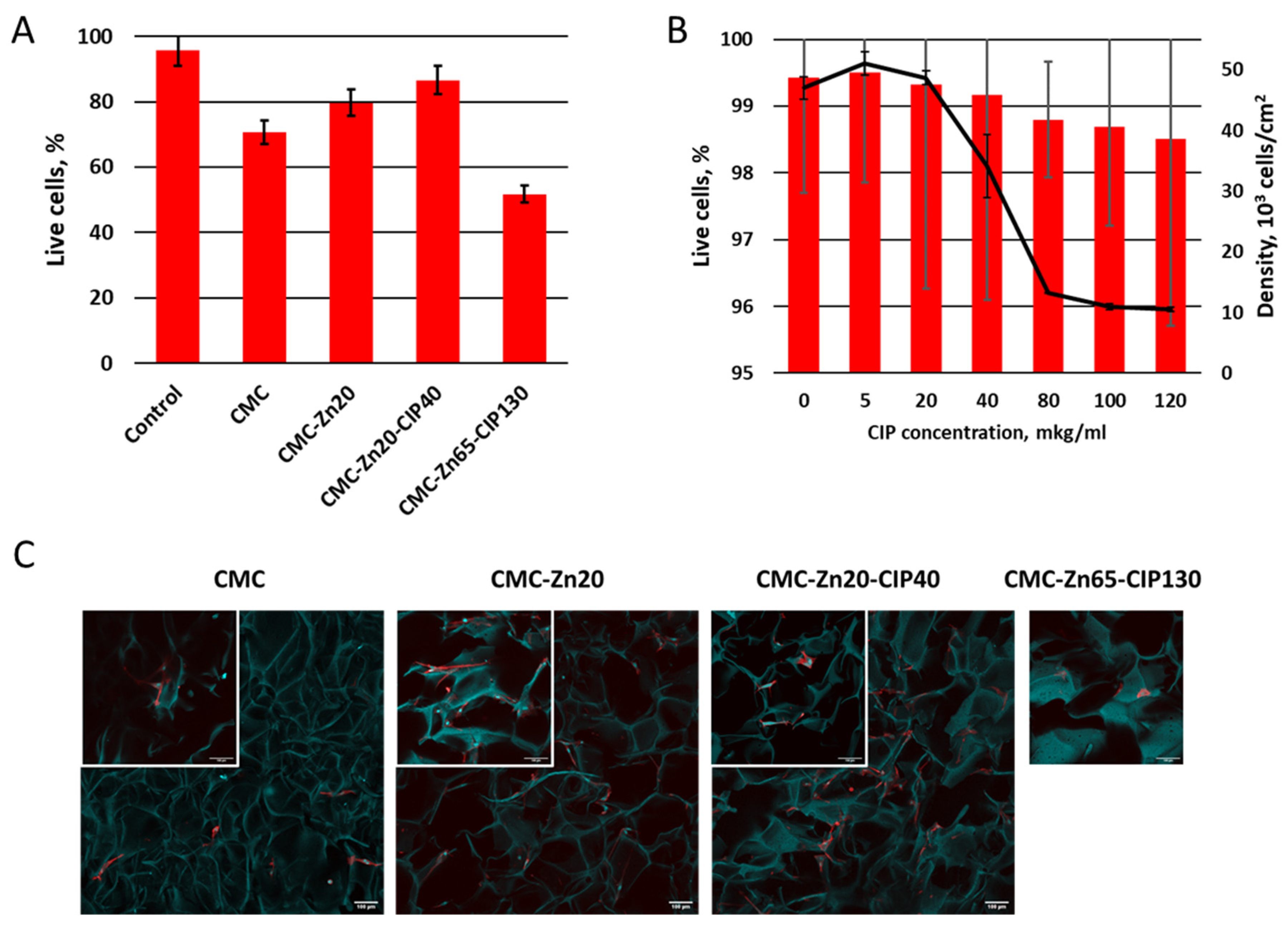

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity

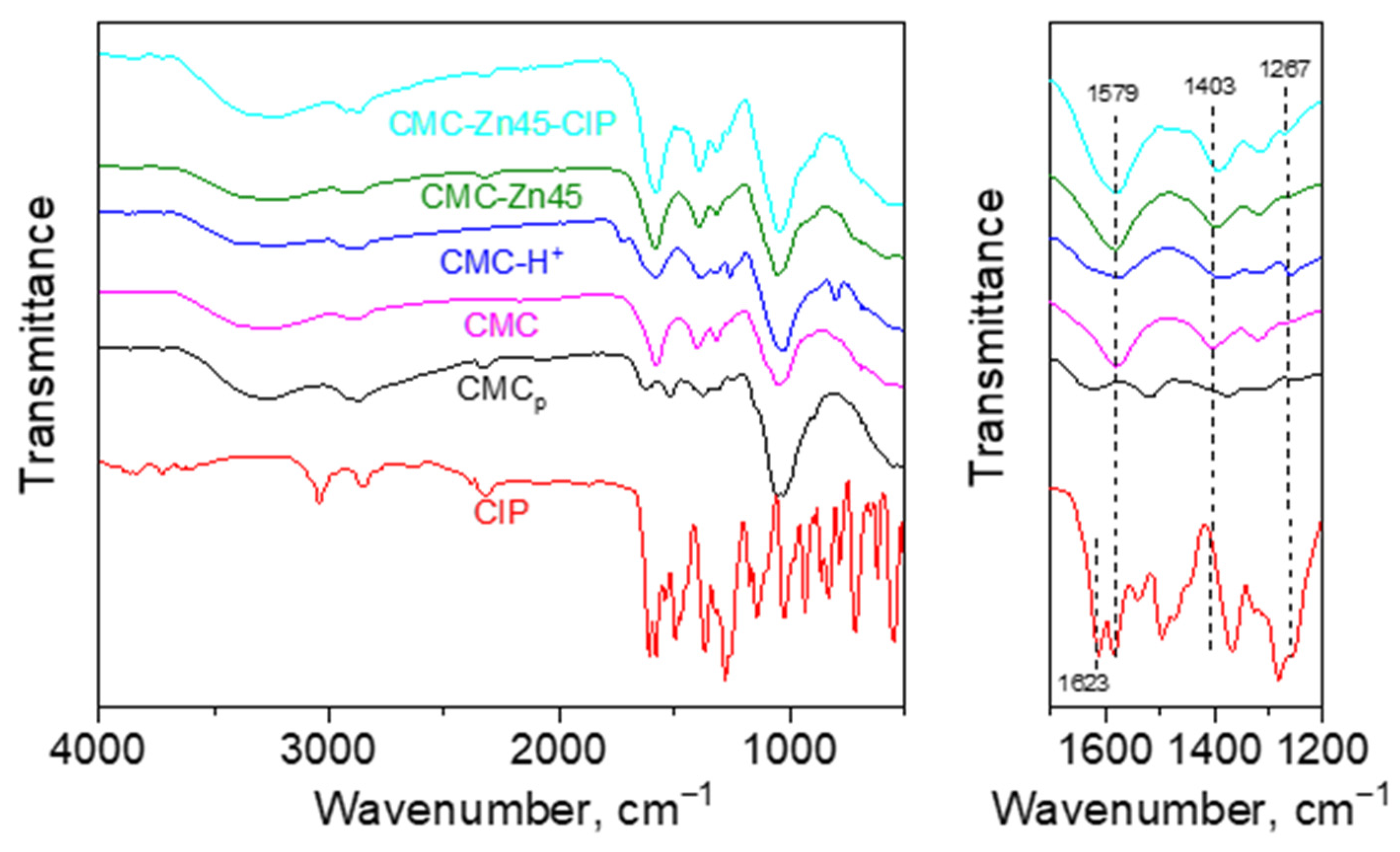

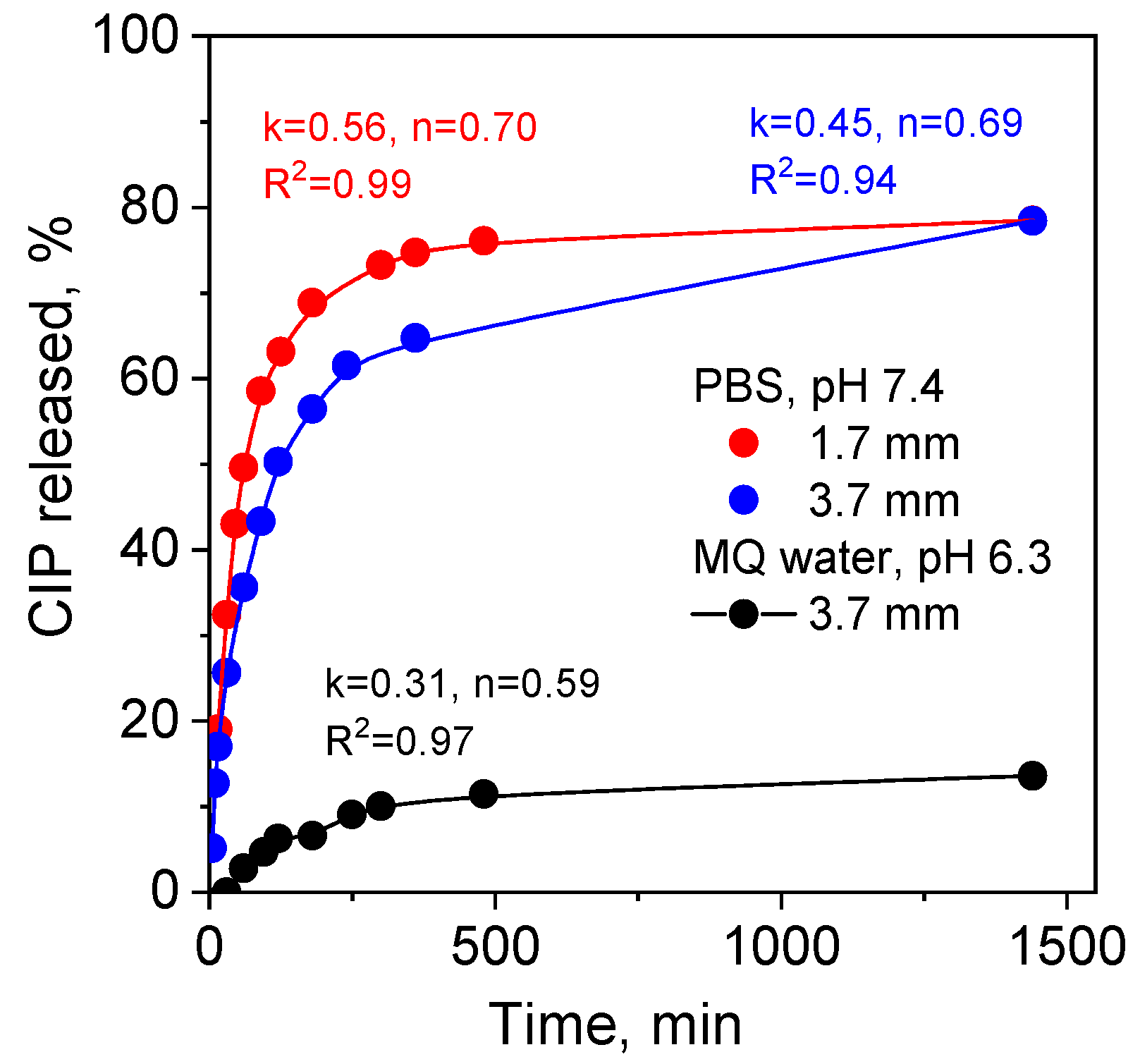

2.3. Binding and Release Mechanisms

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Fabrication of CMC and CMC-Zn Cryogels

3.3. Ciprofloxacin Loading and Release

3.4. Mechanical Properties of Cryogels

3.5. Antibacterial Activity

3.6. Cytotoxicity

3.6.1. Isolation and Cultivation of Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDF)

3.6.2. Cytotoxicity Tests with Zn2+ and CIP

3.6.3. Cultivation of Human Dermal Fibroblast in Cryogels

3.6.4. Assessing of Fibroblast Viability

3.6.5. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, K.; Han, Q.; Chen, B.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Antimicrobial Hydrogels: Promising Materials for Medical Application. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 2217–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darouiche, R.O. Antimicrobial Approaches for Preventing Infections Associated with Surgical Implants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapusta, O.; Jarosz, A.; Stadnik, K.; Giannakoudakis, D.A.; Barczyński, B.; Barczak, M. Antimicrobial Natural Hydrogels in Biomedicine: Properties, Applications, and Challenges—A Concise Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, T.; Narayan, R.; Maji, S.; Behera, S.; Kulanthaivel, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Banerjee, I.; Pal, K.; Giri, S. Gelatin/Carboxymethyl Chitosan Based Scaffolds for Dermal Tissue Engineering Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendradi, E.; Hariyadi, D.; Adrianto, M. The Effect of Two Different Crosslinkers on in Vitro Characteristics of Ciprofloxacin-Loaded Chitosan Implants. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, S.; Eskandani, M.; Vandghanooni, S.; Hossainpour, H.; Jaymand, M. Ciprofloxacin-Loaded Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Hydrogel Containing Silica Nanoparticles as a Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering Application. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Shang, J.; Shi, L. An Injectable Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogel Scaffold Formed via Coordination Bond for Antibacterial and Osteogenesis in Osteomyelitis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 324, 121466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Sun, S.; Cui, C.; Li, X.; Wu, S.; Ma, J.; Chen, S.; Li, C.M. Zinc Ions and Ciprofloxacin-Encapsulated Chitosan/Poly(ɛ-Caprolactone) Composite Nanofibers Promote Wound Healing via Enhanced Antibacterial and Immunomodulatory. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamfil, D.; Butnaru, E.; Vasile, C. Poly (Vinyl Alcohol)/Chitosan Cryogels as PH Responsive Ciprofloxacin Carriers. J. Polym. Res. 2016, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Kumar, P. Synthesis and Characterization of PH-Sensitive Nanocarrier Based Chitosan-g-Poly(Itaconic Acid) for Ciprofloxacin Delivery for Anti-Bacterial Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, T. V.; Jin, H.; Dutta, S.D.; Aacharya, R.; Chen, K.; Ganguly, K.; Randhawa, A.; Lim, K.T. Zn@TA Assisted Dual Cross-Linked 3D Printable Glycol Grafted Chitosan Hydrogels for Robust Antibiofilm and Wound Healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 344, 122522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruczkowska, W.; Kłosiński, K.K.; Grabowska, K.H.; Gałęziewska, J.; Gromek, P.; Kciuk, M.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Kołat, D.; Wach, R.A. Medical Applications and Cellular Mechanisms of Action of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogels. Molecules 2024, 29, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroda, A.; Privar, Y.; Maiorova, M.; Beleneva, I.; Eliseikina, M.; Skatova, A.; Marinin, D.; Bratskaya, S. Chitosan versus Carboxymethyl Chitosan Cryogels: Bacterial Colonization, Human Embryonic Kidney 293T Cell Culturing and Co-Culturing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitha, A.; Divya Rani, V.V.; Krishna, R.; Sreeja, V.; Selvamurugan, N.; Nair, S.V.; Tamura, H.; Jayakumar, R. Synthesis, Characterization, Cytotoxicity and Antibacterial Studies of Chitosan, O-Carboxymethyl and N,O-Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 78, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Yu, H.; Zheng, D. O-Carboxymethyl Chitosan in Biomedicine: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoukry, A. a.; Hosny, W.M. Coordination Properties of N,O-Carboxymethyl Chitosan (NOCC). Synthesis and Equilibrium Studies of Some Metal Ion Complexes. Ternary Complexes Involving Cu(II) with (NOCC) and Some Biorelevant Ligand. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2012, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, A. Adsorption Properties and Mechanism of Cross-Linked Carboxymethyl-Chitosan Resin with Zn(II) as Template Ion. React. Funct. Polym. 2006, 66, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patale, R.L.; Patravale, V.B. O,N-Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Zinc Complex: A Novel Chitosan Complex with Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Pei, L.; Zhang, W.; Shu, G.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Xu, F.; Tang, H.; Peng, G.; Zhao, L.; et al. Chitosan-Poloxamer-Based Thermosensitive Hydrogels Containing Zinc Gluconate/Recombinant Human Epidermal Growth Factor Benefit for Antibacterial and Wound Healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 130, 112450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padaga, S.G.; Bhatt, H.; Ch, S.; Paul, M.; Itoo, A.M.; Ghosh, B.; Roy, S.; Biswas, S. Glycol Chitosan-Poly(Lactic Acid) Conjugate Nanoparticles Encapsulating Ciprofloxacin: A Mucoadhesive, Antiquorum-Sensing, and Biofilm-Disrupting Treatment Modality for Bacterial Keratitis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 18360–18385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rembe, J.D.; Boehm, J.K.; Fromm-Dornieden, C.; Hauer, N.; Stuermer, E.K. Comprehensive Analysis of Zinc Derivatives Pro-Proliferative, Anti-Apoptotic and Antimicrobial Effect on Human Fibroblasts and Keratinocytes in a Simulated, Nutrient-Deficient Environment in Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2020, 9, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, G.; Kessissoglou, D.P. Quinolones and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Interacting with Copper(Ii), Nickel(Ii), Cobalt(Ii) and Zinc(Ii): Structural Features, Biological Evaluation and Perspectives. Dalt. Trans. 2013, 42, 6252–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkan, A.; MacKlyne, H.R.; Chirgadze, Di.Y.; Bond, A.D.; Hesketh, A.R.; Hong, H.J. Zn(II) Mediates Vancomycin Polymerization and Potentiates Its Antibiotic Activity against Resistant Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewes, F.; Bahamondez-Canas, T.F.; Moraga-Espinoza, D.; Smyth, H.D.C.; Watts, A.B. In Vivo Efficacy of a Dry Powder Formulation of Ciprofloxacin-Copper Complex in a Chronic Lung Infection Model of Bioluminescent Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 152, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uivarosi, V. Metal Complexes of Quinolone Antibiotics and Their Applications: An Update. Molecules 2013, 18, 11153–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratskaya, S.; Privar, Y.; Slobodyuk, A.; Shashura, D.; Marinin, D.; Mironenko, A.; Zheleznov, V.; Pestov, A. Cryogels of Carboxyalkylchitosans as a Universal Platform for the Fabrication of Composite Materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroda, A.; Privar, Y.; Maiorova, M.; Skatova, A.; Bratskaya, S. Sponge-like Scaffolds for Colorectal Cancer 3D Models: Substrate-Driven Difference in Micro-Tumors Morphology. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.G.; Hon, D.N.S. Chelation of Chitosan Derivatives with Zinc Ions. II. Association Complexes of Zn2+ onto O,N-Carboxymethyl Chitosan. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 79, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privar, Y.; Shashura, D.; Pestov, A.; Modin, E.; Baklykov, A.; Marinin, D.; Bratskaya, S. Metal-Chelate Sorbents Based on Carboxyalkylchitosans: Ciprofloxacin Uptake by Cu(II) and Al(III)-Chelated Cryogels of N-(2-Carboxyethyl)Chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privar, Y.; Shashura, D.; Pestov, A.; Ziatdinov, A.; Azarova, Y.; Bratskaya, S. Effect of Regioselectivity of Chitosan Carboxyalkylation and Type of Cross-Linking on the Metal-Chelate Sorption Properties toward Ciprofloxacin. React. Funct. Polym. 2020, 150, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uivarosi, V. Metal Complexes of Quinolone Antibiotics and Their Applications: An Update. Molecules 2013, 18, 11153–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djurdjevic, P.; Jakovljevic, I.; Joksovic, L.; Ivanovic, N.; Jelikic-Stankov, M. The Effect of Some Fluoroquinolone Family Members on Biospeciation of Copper(II), Nickel(II) and Zinc(II) Ions in Human Plasma. Molecules 2014, 19, 12194–12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.N.; Li, X.Y.; Huang, J.; Wahid, F.; Zhong, C.; Chu, L.Q. Continuous Production of Antibacterial Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Zinc Supramolecular Hydrogel Fiber Using a Double-Syringe Injection Device. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsikogianni, M.G.; Wood, D.J.; Missirlis, Y.F. Biomaterial Functionalized Surfaces for Reducing Bacterial Adhesion and Infection. In Handbook of Bioceramics and Biocomposites; Antoniac, I.V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015, 2015; pp. 1–28 ISBN 9783319092300.

- Baudry-Simner, P.J.; Singh, A.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Hoban, D.J.; Zhanel, G.G. Mechanisms of Reduced Susceptibility to Ciprofloxacin in Escherichia Coli Isolates from Canadian Hospitals. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 23, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, D.; Yergeshov, A.A.; Zoughaib, M.; Sadykova, F.R.; Gareev, B.I.; Savina, I.N.; Abdullin, T.I. Transition Metal-Doped Cryogels as Bioactive Materials for Wound Healing Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 109759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanigan, K.C.; Pidsosny, K. Reflectance FTIR Spectroscopic Analysis of Metal Complexation to EDTA and EDDS. Vib. Spectrosc. 2007, 45, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogina, A.; Lončarević, A.; Antunović, M.; Marijanović, I.; Ivanković, M.; Ivanković, H. Tuning Physicochemical and Biological Properties of Chitosan through Complexation with Transition Metal Ions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioomars, S.; Heidari, S.; Malaekeh-Nikouei, B.; Shayani Rad, M.; Khameneh, B.; Mohajeri, S.A. Ciprofloxacin-Imprinted Hydrogels for Drug Sustained Release in Aqueous Media. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2017, 22, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakhova, I.; Golikov, A.; Azarova, Y.; Bratskaya, S. Extended Rate Constants Distribution (RCD) Model for Sorption in Heterogeneous Systems: 2. Importance of Diffusion Limitations for Sorption Kinetics on Cryogels in Batch. Gels 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, S.; Pitarresi, G.; Palumbo, F.S.; Fiorica, C.; Catania, V.; Schillaci, D.; Giammona, G. An Asymmetric Electrospun Membrane for the Controlled Release of Ciprofloxacin and FGF-2: Evaluation of Antimicrobial and Chemoattractant Properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzi, C.; Cerezo, P.; Salcedo, I.; Sánchez, R.; Viseras, C. Mathematical Models Describing Drug Release from Biopolymeric Delivery Systems. Mater. Technol. 2010, 25, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratskaya, S.; Skatova, A.; Privar, Y.; Boroda, A.; Kantemirova, E.; Maiorova, M.; Pestov, A. Stimuli-Responsive Dual Cross-Linked N-Carboxyethylchitosan Hydrogels with Tunable Dissolution Rate. Gels 2021, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DA1 | DStot2 | N-DS3 | O-DS4 | Monomer composition | |||

| NH2 | NHR | NR2 | NHCOCH3 | ||||

| 0.25 | 1.49 | 0.29 | 1.20 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0 | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).