Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

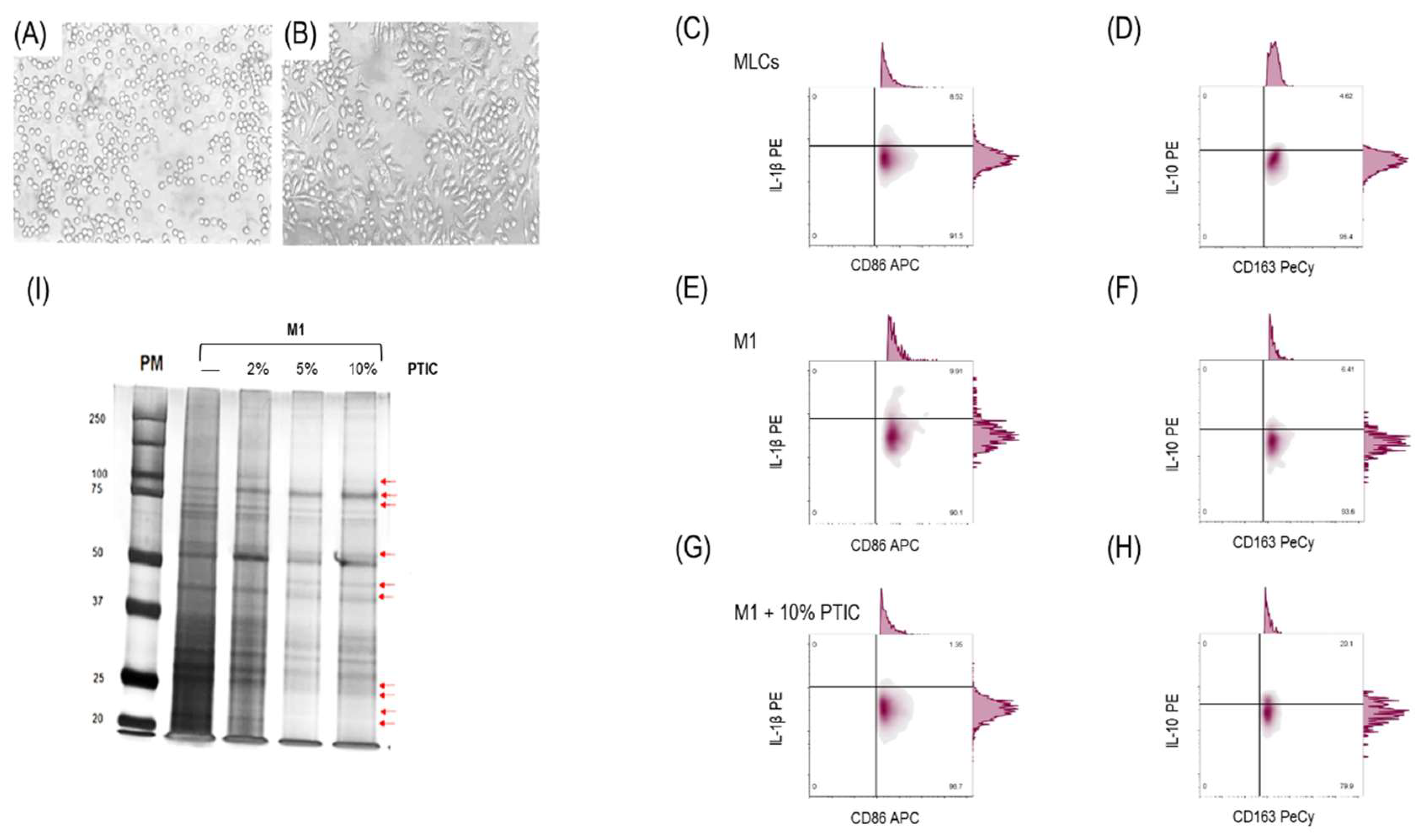

2.1. Differentiation of THP-1 to macrophage-like cells and polarization to M1

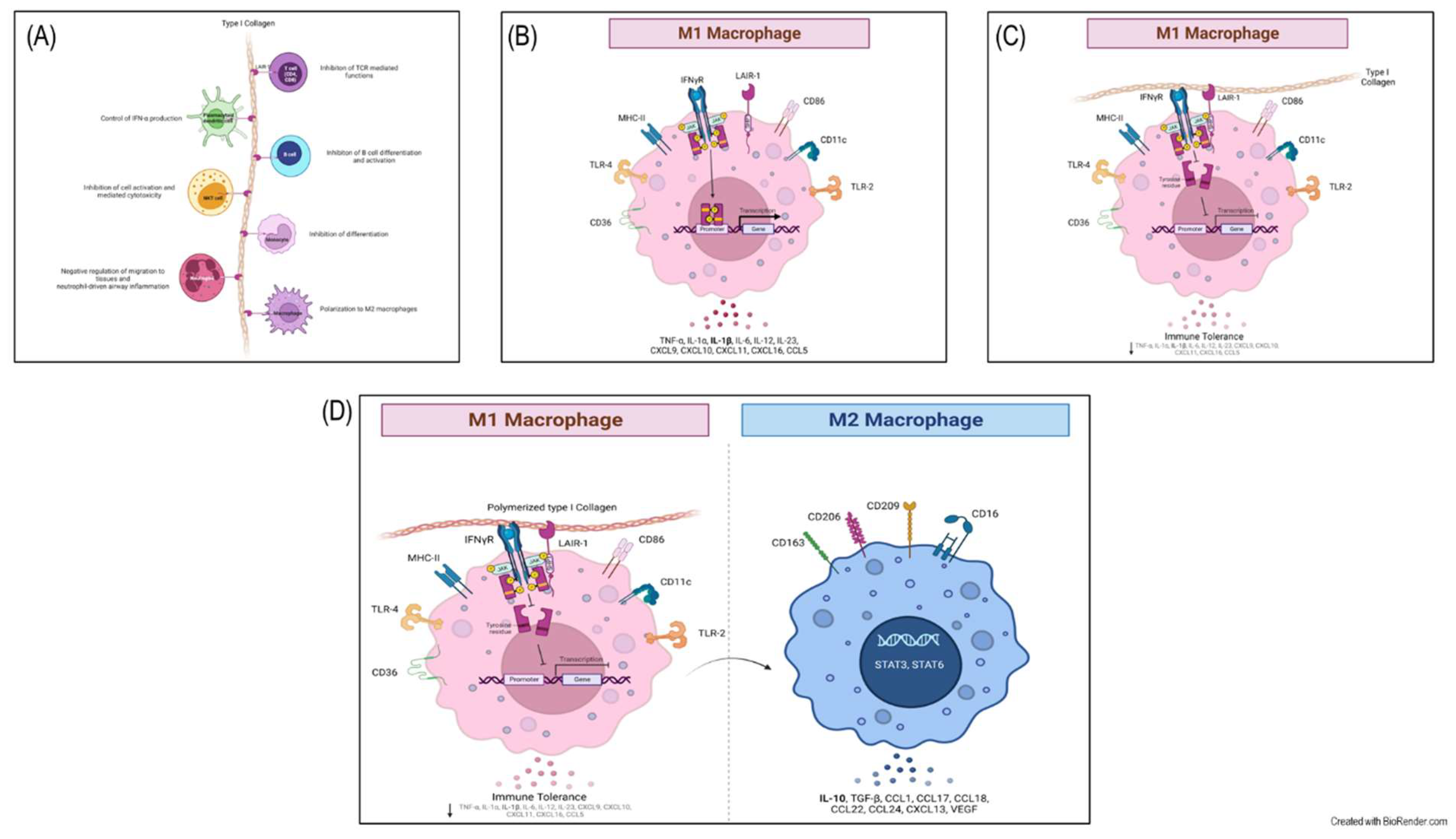

2.2. The effect of polymerized type I collagen on M1 macrophages is dose-dependent, favoring polarization toward the M2 phenotype

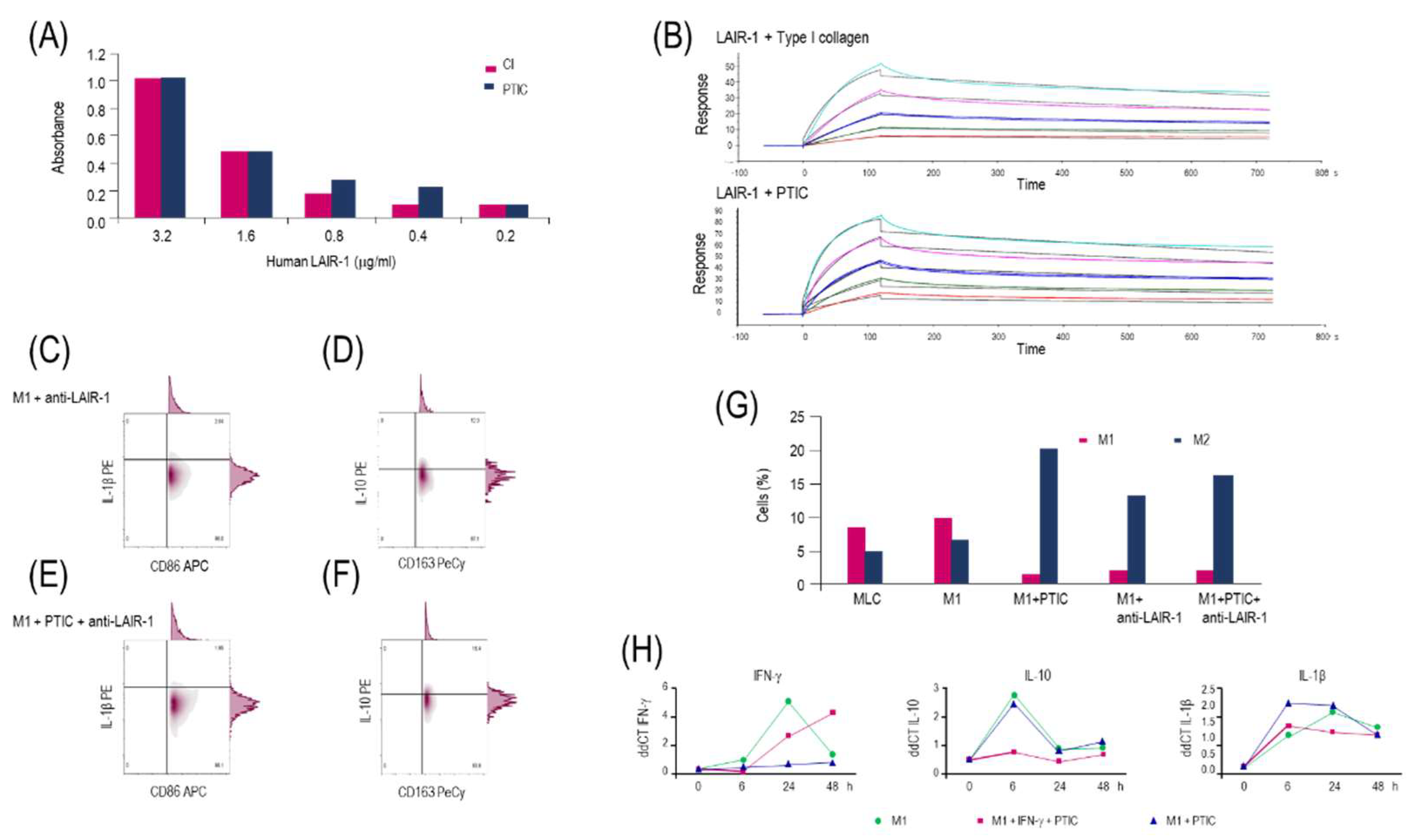

2.3. Polymerized type I collagen binds to LAIR-1 with a similar affinity as native type I collagen

2.4. Activation of the LAIR-1 receptor with the anti-huLAIR-1 antibody or polymerized type I collagen favors the change of M1 to M2 macrophage phenotype

2.5. Polymerized type I collagen downregulates INF-γ gene expression in M1 macrophages

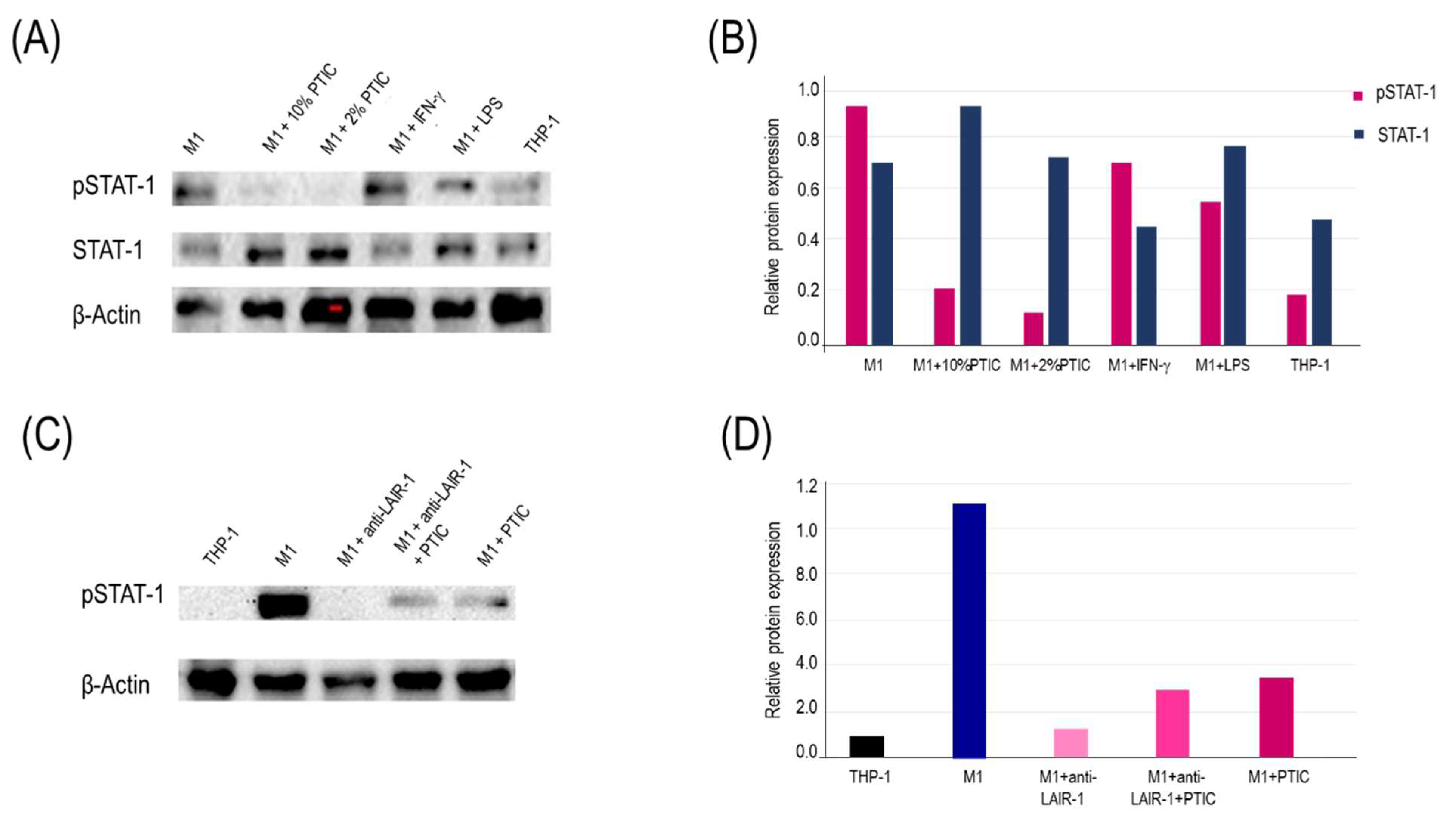

2.6. The binding of polymerized type I collagen to LAIR-1 downregulates inflammation through decrease of STAT-1 phosphorylation in M1 macrophages

2.7. Evaluation of the polymerized type I collagen effect on circulating monocytes (Mo)1 of COVID-19 patients.

2.7.1. Baseline description of the study population

2.7.2. Concomitant medications

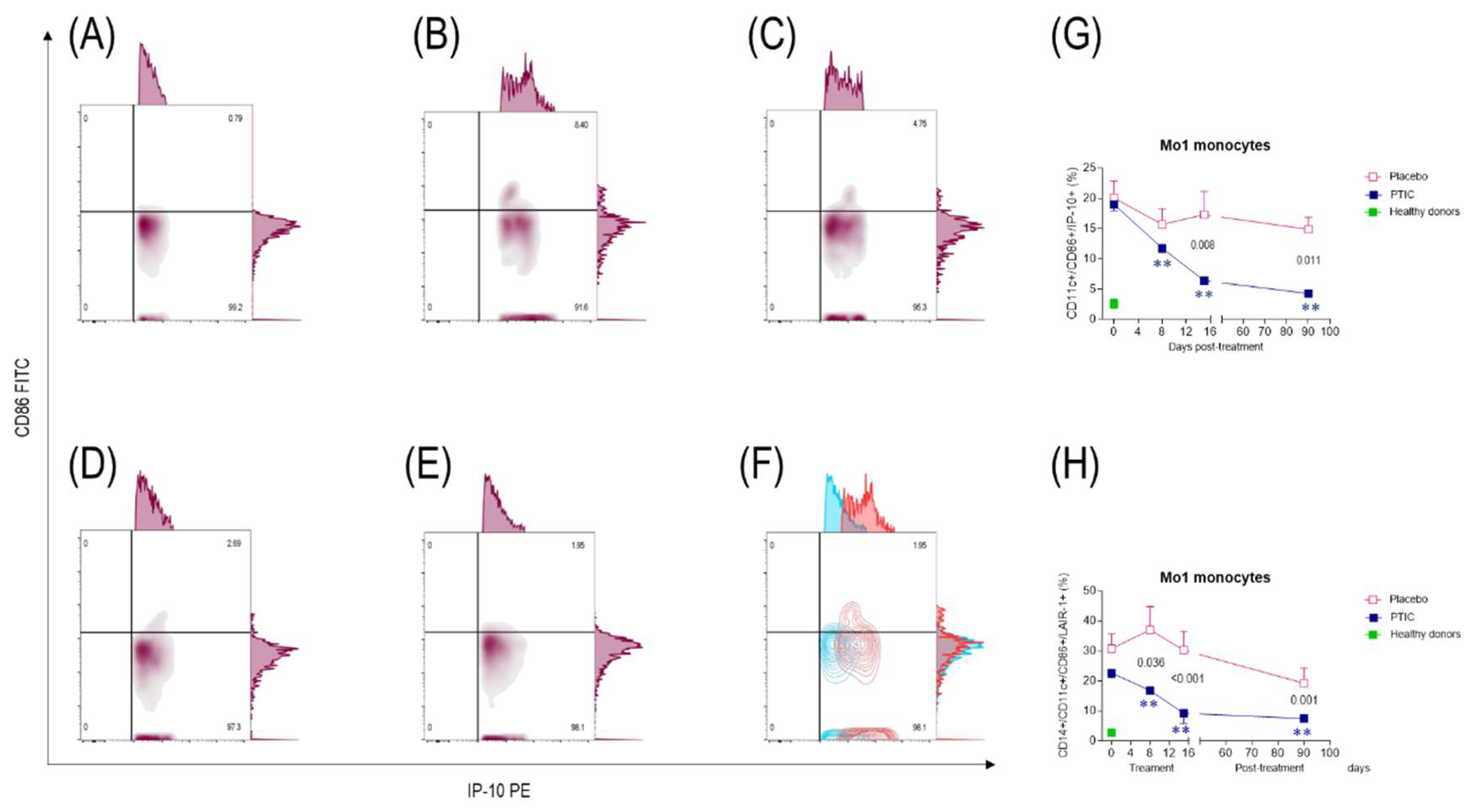

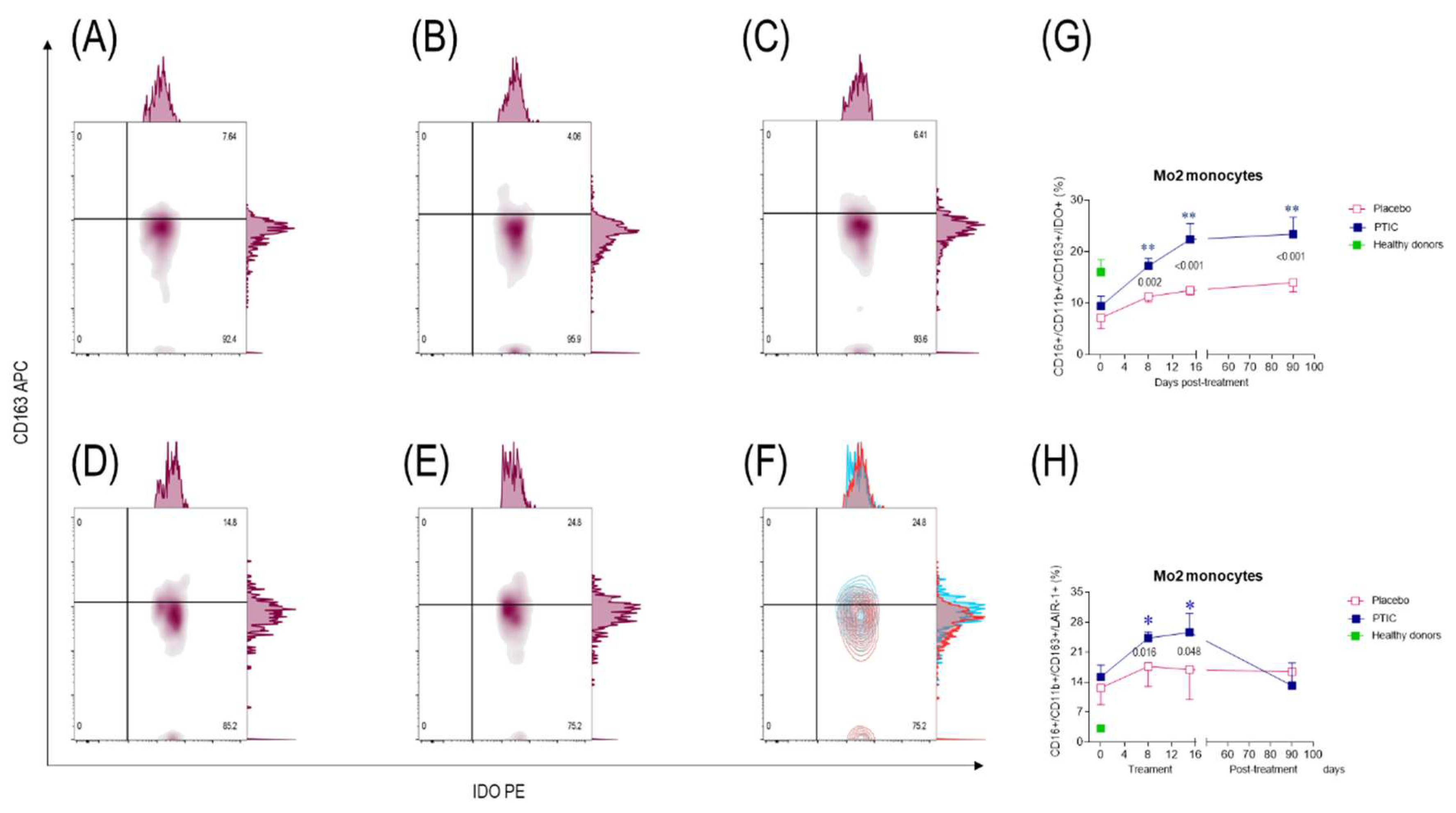

2.7.3. COVID-19 patients under treatment with polymerized type I collagen decrease the number of IP-10-producing monocytes (Mo)1 and increase the number of regulatory IDO-expressing Mo2

2.7.4. Polymerized type I collagen decreases the expression of LAIR-1 in monocytes (Mo)1 and increases it in Mo2

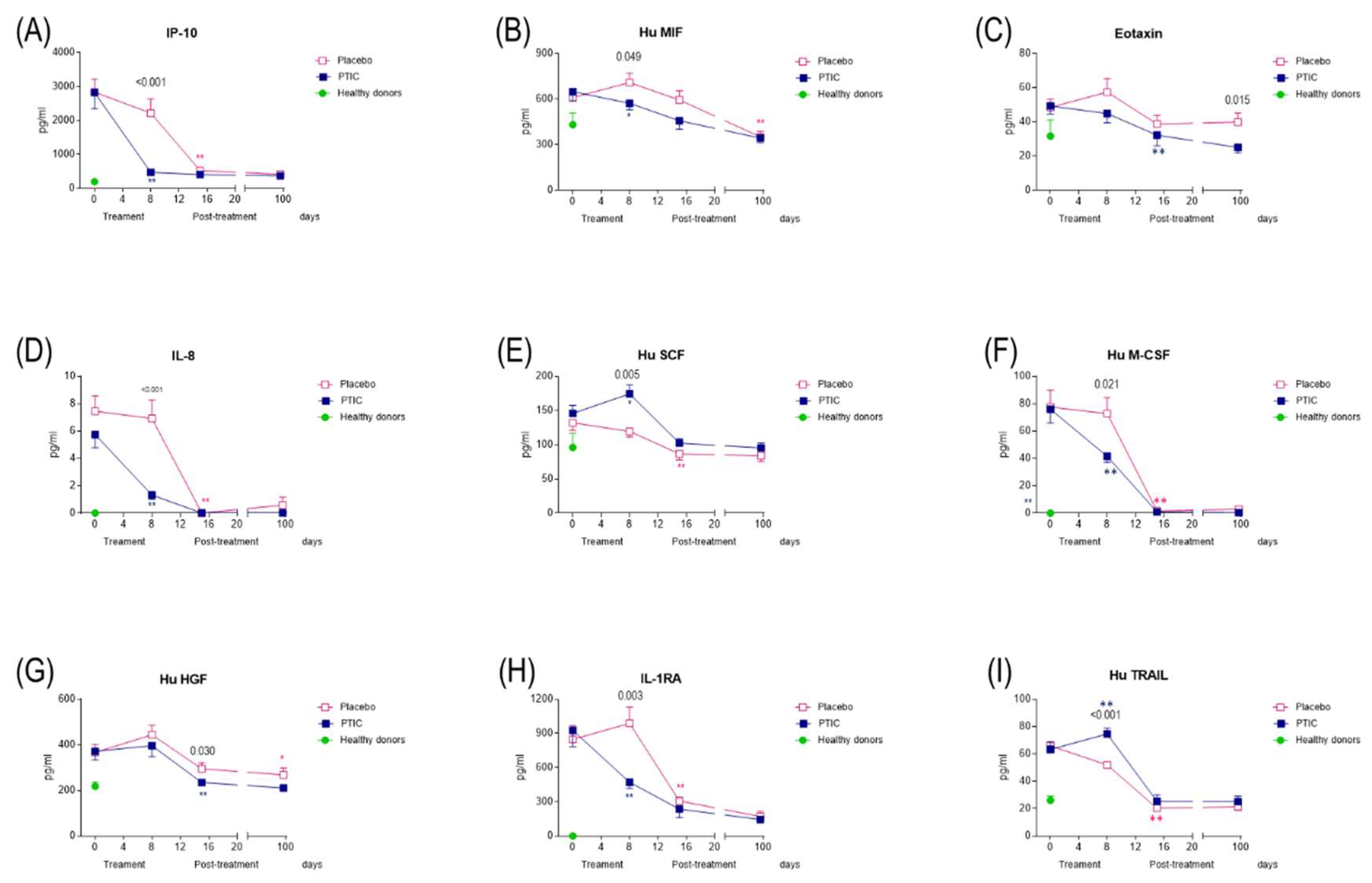

2.7.5. COVID-19 patients under treatment with polymerized type I collagen have lower proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines serum levels

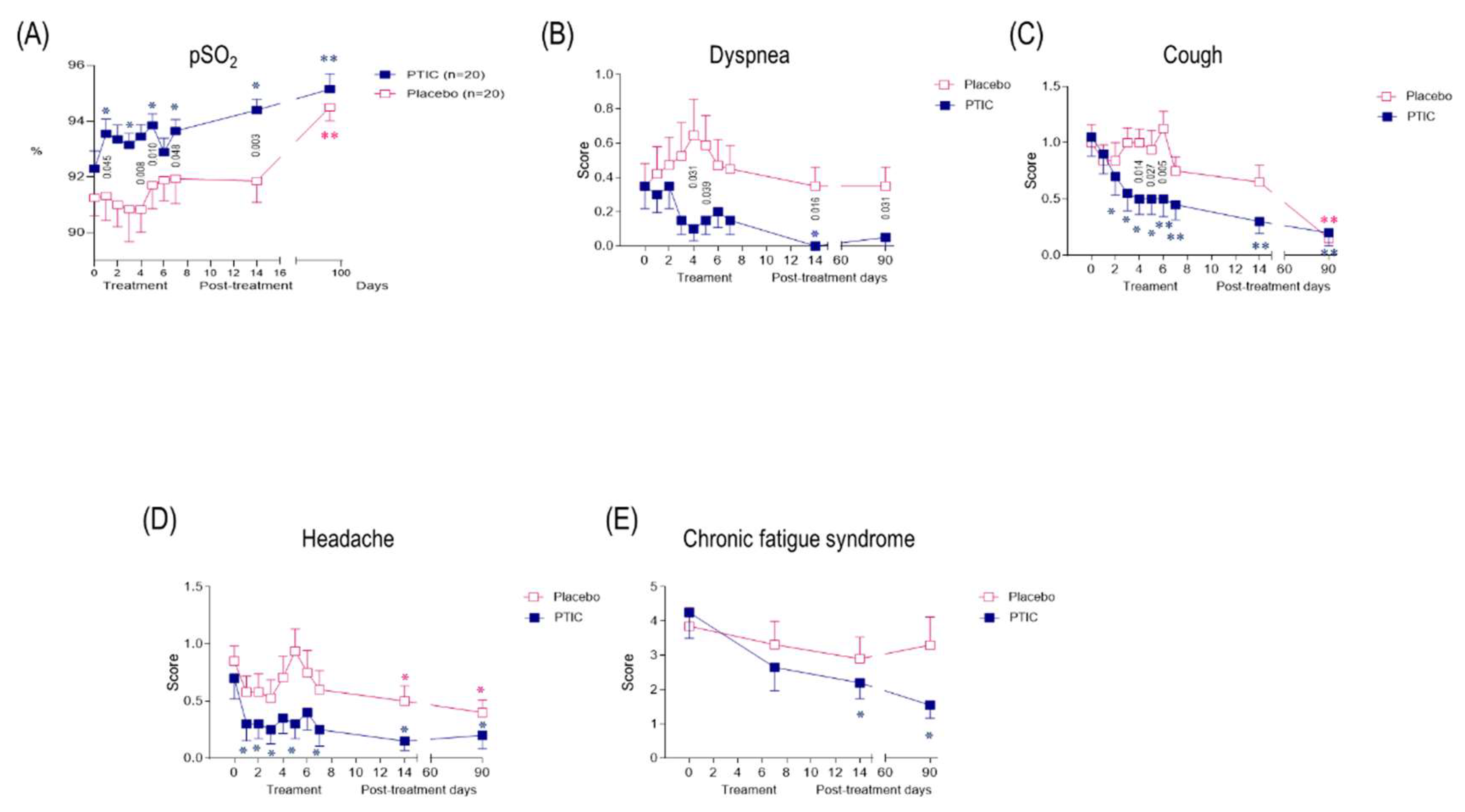

2.7.6. COVID-19 patients under treatment with polymerized type I collagen have better oxygen saturation than those treated with placebo

2.7.7. Treatment with polymerized type I collagen was associated with normal spirometries in post-COVID patients

2.7.8. Polymerized type I collagen treatment was associated with a reduction in symptom duration

2.7.9. Polymerized type I collagen is safe and well-tolerated

2.7.10. Treatment with polymerized type I collagen decreases serum proinflammatory biomarkers and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Cell differentiation and treatments

4.3. Flow cytometry

4.4. Western blotting

4.5. LAIR-1 Binding Assays

4.6. RT-qPCR

4.7. Surface Plasmon Resonance Binding Assay

4.8. Study nested cohort

4.9. Serum cytokines

4.10. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell isolation and flow cytometry

4.11. Chest CT

4.12. Basic spirometry

4.13. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Chimal-Monroy, J.; Bravo-Ruíz, T.; Krötzsch-Gómez, F.E.; Díaz de León, L. Implantes de FibroquelMR aceleran la formación de hueso nuevo en defectos óseos inducidos experimentalmente en cráneos de rata: un estudio histológico. Rev. Biomed. 1997, 8, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Krötzsch-Gómez, F.E.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; de León, L.D.; Reyes-Márquez, R.; Quiróz-Hernández, E. Cytokine Expression is Downregulated by Collagen-Polyvinylpyrrolidone in Hypertrophic Scars. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Rodríguez-Calderón, R.; León, L.D.D.; Alcocer-Varela, J. Mediators of inflammation are down-regulated while apoptosis is up-regulated in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue by polymerized collagen. Clin. & Exp. Immunol. 2002, 130, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Muñoz-Chablé, O.A.; Barrios-Payán, J.; Hernández-Pando, R. Effect of polymerized-type I collagen in knee osteoarthritis. I.In vitrostudy. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 39, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Macip-Rodríguez, P.; Galindo-Feria, A.S.; Cruz-Robles, D.; Soto-Abraham, V.; Escobar-Hernández, S.; Aguilar, D.; Alpizar-Rodríguez, D.; Férez-Blando, K.; Llorente, L. Polymerized-Type I Collagen Induces Upregulation of Foxp3-Expressing CD4 Regulatory T Cells and Downregulation of IL-17-Producing CD4+T Cells (Th17) Cells in Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Krotzsch, E.; Barile-Fabris, L.; Alcala, M.; Espinosa-Morales, R. Subcutaneous administration of collagen-polyvinylpyrrolidone down regulates IL-1beta, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1, ELAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in scleroderma skin lesions. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2005, 30, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Ortíz-Ávalos, M.; Lima, G.; Jurado-Santa Cruz, F.; Llorente, L. Subcutaneous administration of polymerized type I collagen downregulates interleukin (IL)-17A, IL-22 and transforming growth factor-β1 expression, and increases Foxp3-expressing cells in localized scleroderma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 37, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonte-Becerril, M.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J. Polymerized-Type I Collagen Induces a High Quality Cartilage Repair in a Rat Model of Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Bone Rheumatol. Res. 2017, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Muñoz-Chablé, O.A.; Macías-Hernández, S.I.; Agualimpia-Janning, A. Effect of polymerized-type I collagen in knee osteoarthritis. II.In vivostudy. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 39, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Lima, G.; Llorente, L.; Nuñez-Álvarez, C.; Ruiz-Ordaz, B.H.; Echevarría-Zuno, S.; Hernández-Cuevas, V. Polymerized-Type I Collagen Downregulates Inflammation and Improves Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis Following Arthroscopic Lavage: A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Flores, A.; Macías-Hernández, S.I.; Hernández-Molina, G.; Perez-Ortiz, A.; Reyes-Martínez, E.; Belzazar-Castillo de la Torre, J.; Ávila-Jiménez, L.; Vázquez-Bello, M.C.; León-Mazón, M.A.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; et al. Long-Term Effectiveness of Polymerized-Type I Collagen Intra-Articular Injections in Patients with Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation in a Cohort Study. Adv. Orthop. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Rojas, E.; Valverde, M.; Castillo, I.; de León, L.D.; Krötzsch, E. Cellular and humoral responses to collagenpolyvinylpyrrolidone administered during short and long periods in humans. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2003, 81, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Cabral, A.R.; Zapata-Zúñiga, M.; Alcocer-Varela, J. Subcutaneous administration of polymerized-type I collagen for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. An open-label pilot trial. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Fenutria-Ausmequet, R.; Gil-Espinosa, V.; Lozano-Soto, F.; Teliz-Meneses, M.A.; Romero-Trejo, C. , Alcocer-Varela, J. Polymerized-type I collagen for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Effect of intramuscular administration in a double blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2006, 24, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Flores, S.; Priego-Ranero, Á.; Azamar-Llamas, D.; Olvera-Prado, H.; Rivas-Redonda, K.I.; Ochoa-Hein, E.; Perez-Ortiz, A.; Rendón-Macías, M.E.; Rojas-Castañeda, E.; Urbina-Terán, S.; et al. Effect of polymerised type I collagen on hyperinflammation of adult outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpio-Orantes, L.D.; García-Méndez, S.; Sánchez-Díaz, J.S.; Aguilar-Silva, A.; Contreras-Sánchez, E.R.; Hernández, S.N.H. Use of Fibroquel® (Polymerized type I collagen) in patients with hypoxemic inflammatory pneumonia secondary to COVID-19 in Veracruz, Mexico. J. Anesthesia & Crit. Care 2021, 13, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Rocha MD, H.A. Safety and efficacy of Fibroquel® (polymerized type I collagen) in adult outpatients with moderate COVID-19: an open-label study. J. Anesthesia Crit. Care 2021, 13, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchor-Amador, J.R.; Mota-González, E.; M. Amador-Ayestas, S.; Castelán-López, M.; M.Vidal-Mendez, A.; Ojeda Guevara, J.A.; Palma-Vázquez, K.; Ríos-Lina, A.A. Polymerized type I collagen improves the mean oxygen saturation and efficiently shortens symptom duration and hospital stay in adult hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: Randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Anesthesia & Crit. Care 2021, 13, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Zhang, K.; Gao, X.; Lv, M.; Luan, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, A.; Gou, X. Role and mechanism of LAIR-1 in the development of autoimmune diseases, tumors, and malaria: A review. Curr. Res. Transl. Med. 2020, 68, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers 2021, 13, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, N.; Guo, W.; Jin, B.; Fang, L.; Chen, L. LAIR-1 activation inhibits inflammatory macrophage phenotype in vitro. Cell. Immunol. 2018, 331, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordkamp, M.J.M.O.; van Roon, J.A.G.; Douwes, M.; de Ruiter, T.; Urbanus, R.T.; Meyaard, L. Enhanced secretion of leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 2 (LAIR-2) and soluble LAIR-1 in rheumatoid arthritis: LAIR-2 is a more efficient antagonist of the LAIR-1-collagen inhibitory interaction than is soluble LAIR-1. Arthritis & Rheum. 2011, 63, 3749–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheiro, T.; Garcia, S.; Pascoal Ramos, M.I.; Giovannone, B.; Radstake, T.R.D.J.; Marut, W.; Meyaard, L. Leukocyte Associated Immunoglobulin Like Receptor 1 Regulation and Function on Monocytes and Dendritic Cells During Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Easterling, E.R.; Price, L.C.; Smith, S.L.; Coligan, J.E.; Park, J.-E.; Brand, D.D.; Rosloniec, E.F.; Stuart, J.M.; Kang, A.H.; et al. The Role of Leukocyte-Associated Ig-like Receptor-1 in Suppressing Collagen-Induced Arthritis. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 2692–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L.K.; Winstead, M.; Kee, J.D.; Park, J.J.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Yi, A.-K.; Stuart, J.M.; Rosloniec, E.F.; Brand, D.D.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 20-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Upregulate LAIR-1 and Attenuate Collagen Induced Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, K.; Zhang, C.M.; Jin, B.Q.; Zhuang, R.; Ding, Y. The role of LAIR-1 (CD305) in T cells and monocytes/macrophages in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. Immunol. 2014, 287, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genin, M.; Clement, F.; Fattaccioli, A.; Raes, M.; Michiels, C. M1 and M2 macrophages derived from THP-1 cells differentially modulate the response of cancer cells to etoposide. BMC Cancer 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenakin, TA. Pharmacology Primer: Theory, Application and Methods, Elsevier Science & Technology Books, 2004.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, A.; Takahashi, H.; Ibe, T.; Ishii, H.; Kurata, Y.; Ishizuka, Y.; Hamamoto, Y. Comparison of semiquantitative chest CT scoring systems to estimate severity in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Eur. Radiol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, D.F.; Thomas, P.G. Towards integrating extracellular matrix and immunological pathways. Cytokine 2017, 98, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyaard, L. The inhibitory collagen receptor LAIR-1 (CD305). J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 83, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthivasan, S.; Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Martinez-Martin, N.; Husain, B.; Verschueren, E.; Wong, A.; Yang, Y.A.; Sun, Y.; Pham, V.; Hinkle, T.; et al. Homeostatic functions of monocytes and interstitial lung macrophages are regulated via collagen domain-binding receptor LAIR1. Immunity 2021, 54, 1511–1526.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, R.; Wang, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, D.; Xie, J.; Hu, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Silencing LAIR-1 in human THP-1 macrophage increases foam cell formation by modulating PPARγ and M2 polarization. Cytokine 2018, 111, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Tao, Y.; Piao, H.; Wang, X.; Luan, X.; Du, M.; Li, D. Involvement of the JAK-STAT pathway in collagen regulation of decidual NK cells. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Gao, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Q.; et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced inflammatory bowel disease by regulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization via the STAT1 and STAT6 pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helou, D.G.; Quach, C.; Hurrell, B.P.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Akbari, A.; Shen, S.; Shafiei-Jahani, P.; Akbari, O. LAIR-1 limits macrophage activation in acute inflammatory lung injury. Mucosal Immunol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, C.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wei, J.; Huang, F.; Wang, F.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Xing, L.; et al. Plasma IP-10 and MCP-3 levels are highly associated with disease severity and predict the progression of COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 119–127.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Su, L.; Zhang, D.; Fan, J.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Xie, J.; Xu, Y.; et al. IP-10 and MCP-1 as biomarkers associated with disease severity of COVID-19. Mol. Med. 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Gao, M.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Kim, J.; Aliyari, R.; et al. Interleukin-8 as a Biomarker for Disease Prognosis of Coronavirus Disease-2019 Patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qazi, B.S.; Tang, K.; Qazi, A. Recent Advances in Underlying Pathologies Provide Insight into Interleukin-8 Expression-Mediated Inflammation and Angiogenesis. Int. J. Inflamm. 2011, 2011, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesta, M.C.; Zippoli, M.; Marsiglia, C.; Gavioli, E.M.; Mantelli, F.; Allegretti, M.; Balk, R.A. The Role of Interleukin-8 in Lung Inflammation and Injury: Implications for the Management of COVID-19 and Hyperinflammatory Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melton, D.W.; McManus, L.M.; Gelfond, J.A.L.; Shireman, P.K. Temporal phenotypic features distinguish polarized macrophagesin vitro. Autoimmunity 2015, 48, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, P. Is macrophages heterogeneity important in determining COVID-19 lethality? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 143, 110073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, K.; Liang, L.; Sun, J.; Xu, B.; Dai, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Longitudinal COVID-19 profiling associates IL-1RA and IL-10 with disease severity and RANTES with mild disease. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Carpio-Orantes, L. New off-label or compassionate drugs and vaccines in the fight against COVID-19. Microbes, Infect. Chemother. 2022, 2, e1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, F.; Kirdar, S.; Karul, A.B.; Ceylan, E. The value of C-reactive protein as a marker of systemic inflammation in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2008, 19, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline | 8-day post-treatment | 15-day post-treatment | 90-day post-treatment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Subjects (N= 40) |

PTCI (N= 20) |

Placebo (N= 20) |

P |

PTCI (N= 20) |

Placebo (N= 20) |

P |

PTCI (N= 20) |

Placebo (N= 20) |

P |

PTCI (N= 20) |

Placebo (N= 20) |

P | |

| Demographics | |||||||||||||

| Age (years), mean±SD Median Range |

49.6±13.8 48.0 19.0–78.0 |

48.5±15.1 45.5 19.0–73.0 |

50.7±12.6 50.5 31.0–78.0 |

0.612 | |||||||||

| Male sex, n, (%) | 20 (50.0) | 12 (60.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0.343 | |||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD Median Range |

29.7±4.2 29.4 22.7–40.8 |

28.7±3.5 28.4 23.1–38.3 |

30.6±4.7 30.5 22.7–40.8 |

0.145 | |||||||||

| Guangzhou Severity Index, mean±SD Median Range |

93.2±24.4 92.9 44.4–137.5 |

92.7±27.1 93.3 44.4–134.1 |

93.7±22.1 91.8 53.2-137.5 |

0.907 | |||||||||

| Chest CT Score 0% <20% 20-50% >50% |

5 (13) 26 (65) 8 (20) 1 (2) |

3 (15) 12 (60) 4 (20) 1 (5) |

2 (10) 14 (70) 4 (20) 0 (0.0) |

||||||||||

| pSO2<92% (%) | 16 (40) | 6 (30) | 10 (50) | 0.333 | 2 (10) | 6 (30) | 0.235 | 0 (0) | 5 (25) | 0.047 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 |

| pSO2; mean±SD Median Range |

91.8±2. 9 92.0 84-97 |

92.3±2.9 92.5 84-96 |

91.3±2.9 91.5 86-97 |

0.255 |

93.7±1.8 93.5 91-97 |

91.9±3.6 93.0 84-97 |

0.048 |

94.4±1.7 94.5 92-97 |

91.9±2.9 92.5 87-97 |

0.003 |

95.2±2.5 94.5 92-100 |

94.5±2.2 94.0 91-99 |

0.382 |

| Laboratory variables | |||||||||||||

| Complete blood count | |||||||||||||

| Leukocyte count (x10^3/µL), mean±SD Median Range |

5.9±2.3 5.4 2.8-12.5 |

5.5±1.6 5.6 2.8–8.0 |

5.7±2.5 4.9 3.0-12.5 |

0.490 |

6.2±1.5 6.3 3.6-9.3 |

6.4±1.7 6.0 3.9-11.4 |

0.766 |

6.6±1.2 6.5 4.8-9.6 |

7.1±1.2 6.9 5.1-9.7 |

0.462 |

6.7±1.3 6.8 3.7-8.5 |

6.8±1.5 6.7 4.6-9.5 |

0.856 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), mean±SD Median Range |

15.3±2.03 15.25 10.5-20.1 |

15.9±2.6 16.0 11.9-20.1 |

14.9±1.8 15.1 10.5-18.1 |

0.274 |

15.4±1.8 15.3 11.9-20.1 |

14.6±1.9 14.7 9.7-18.3 |

0.191 |

15.2±1.5 15.7 11.2-17.6 |

14.4±1.6 14.4 10.0-16.9 |

0.182 |

15.7±1.7 16.0 12.0-19.4 |

14.9±1.7 14.7 11.2-19.0 |

0.395 |

| Platelets (K/µL), mean±SD Median Range |

265±41 239 73–910 |

286±162 241 150-910 |

243±118 229 73-568 |

0.522 |

331±122 297 151-642 |

312±127 287 85-605 |

0.678 |

299±897 297 166-469 |

365±158 312 20-620 |

0.121 |

274±75 267 169-460 |

282±971 271 150-579 |

0.775 |

| Lymphocyte count (%), mean±SD Median Range |

28.0±11.3 27.7 8.0–54.0 |

28.6±11.5 30.8 8.1–43.5 |

28.1±12.0 24.4 8.0-54.0 |

0.938 |

31.7±7.0 33.9 17.4 |

25.7±9.7 26.0 6.6-42.0 |

0.050 |

31.6±8.0 31.5 15.1-46.4 |

29.5±7.1 29.2 12.6-39.6 |

0.324 |

32.0±6.6 33.0 18.1-41.5 |

31.8±8.8 31.0 14.3-49.3 |

0.929 |

| Neutrophil count (%), mean±SD Median Range |

62.5±11.2 62.3 39.0–82.0 |

61.2±12.0 57.9 46.3–80.4 |

62.6±11.4 66.5 39.0–82.0 |

0.962 |

58.1±6.6 55.8 49.0-71.0 |

64.7±10.5 64.3 48.9-85.2 |

0.050 |

58.5±7.4 56.8 44.9-71.2 |

60.1±7.5 59.5 48.7-76.3 |

0.402 |

58.5±6.3 56.2 50.5-71.3 |

58.0±8.3 58.0 41.9-76.3 |

0.845 |

| Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), mean±SD Median Range |

3.0±2.3 2.3 0.7-10.3 |

3.0±2.4 2.1 1.1-9.9 |

3.0±2.3 2. 8 0.7-10.3 |

0.475 |

2.0±0.8 1.7 1.2-4.0 |

3.6±3.3 2.5 1.2-12.9 |

0.040 |

2.1±0.9 1.8 1.0-4.7 |

2.3±1.1 2.1 1.2-6.1 |

0.190 |

2.0±0.7 1.7 1.2-3.7 |

2.1±1.1 1.9 0.9-5.1 |

0.475 |

| Monocytes count (%), mean±SD Median Range |

7.8±2.1 7.7 4.0-11.4 |

7.7±2.0 7.9 4.2-11.4 |

7.9±2.1 7.6 4.0-11.3 |

7.5±1.2 7.4 5.6-10.0 |

7.6±1.9 7.7 4.9-11.9 |

7.2±1.6 6.7 5.3-10.7 |

7.6±1.6 7.6 4.9-10.5 |

6.7±1.3 6.5 5.0-9.6 |

6.8±1.4 2. 8 3.1-9.1 |

||||

| Liver function test (LFT) | |||||||||||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), mean±SD Median Range |

0.6±0.3 0.6 0.2-1.4 |

0.6±0.3 0.6 0.3-1.3 |

0.6±0.3 0.5 0.2–1.4 |

0.597 |

0.8±0.3 0.7 0.4-1.3 |

0.6±0.2 0.6 0.2-1.1 |

0.064 |

0.8±0.3 0.7 0.3-1.3 |

0.6±0.3 0.6 0.2-1.4 |

0.280 |

0.8±0.4 0.8 0.3-1.8 |

0.7±0.3 0.6 0.3-1.5 |

0.142 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL), mean±SD Median Range |

0.1±0.1 0.1 0.03-0.4 |

0.1±0.1 0.1 0.04-0.3 |

0.1±0.1 0.1 0.03-0.4 |

0.987 |

0.1±0.1 0.1 0.05-0.2 |

0.1±0.1 0.1 0.05-0.3 |

0.592 |

0.1±0.04 0.1 0.07-0.2 |

0.1±0.05 0.1 0.04-0.2 |

0.886 |

0.1±0.04 0.1 0.07-0.2 |

0.1±0.05 0.1 0.06-0.3 |

0.613 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL), mean±SD Median Range |

0.5±0.20 0.5 0.15–1.0 |

0.5±0.19 0.5 0.22–1.0 |

0.5±0.22 0.4 0.15–1.0 |

0.449 |

0.6±0.23 0.6 0.28-1.0 |

0.5±0.15 0.5 0.16-0.7 |

0.017 |

0.6±0.27 0.6 0.27-1.1 |

0.5±0.23 0.5 0.19-1.2 |

0.216 |

0.7±0.33 0.7 0.24-1.6 |

0.5±0.25 0.5 0.25-1.3 |

0.113 |

| Aminotransferase, serum aspartate (AST) (U/L), mean±SD Median Range |

35.2±27.3 28.5 9–158 |

27.5±16.6 22.0 11-83 |

40.9±34.2 31.5 9-58 |

0.142 |

23.5±9.0 23.0 12.0-51.0 |

34.5±27.0 25.0 14.0-126.0 |

0.167 |

21.6±13.1 18.0 12.0-70.0 |

23.9±10.9 22.00 12.0-49.0 |

0.623 |

20.0±7.7 19.5 2.8-34.0 |

28.3±18.1 20.5 10.0-87.0 |

0.114 |

| Aminotransferase, serum alanine (ALT) (U/L), mean±SD Median Range |

40±32 29.5 9.0-129.8 |

31±23 28.0 9.0–92.0 |

43±33 31.5 12.0–120.0 |

0.372 |

33±21 32.0 9.0-88.0 |

40±38 28.0 12.0-178.0 |

0.679 |

25±14 22.5 6.0-60.0 |

30±12 28.0 15.0-52.0 |

0.327 |

22±11 19.5 5.0-50.0 |

31±18 23.0 12.0-76.0 |

0.077 |

| Albumin (g/dL), mean±SD Median Range |

4.3 ± 0.4 4.3 3.5 – 5.1 |

4.5 ± 0.3 4.4 3.8 - 5.1 |

4.2 ± 0.3 4.2 3.6-4.7 |

0.150 |

4.2±0.7 4.3 1.9-5.1 |

4.0±0.4 4.0 3.4-4.8 |

0.315 |

4.5±0.4 4.5 3.8-5.6 |

4.1±0.3 4.1 3.6-4.8 |

0.023 |

4.6±0.33 4.7 4.0-5.2 |

4.3±0.2 4.4 3.9-4.7 |

0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) Mean±SD Median Range |

128±77 104.0 70–386 |

117±72 95.5 70-386 |

139±82 104.5 79-354 |

0.284 |

112±60 97.5 81-361 |

121±54 99.0 82-286 |

0.568 |

110±46 96.5 85-297 |

120±62 95.0 78-317 |

0.854 |

104±44 94.5 80-286 |

122±54 98.5 85-307 |

0.133 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (U/L) Mean±SD Median Range |

172±51 162.0 97–303 |

173±64 157.5 97-303 |

171±34 165.5 121-271 |

0.923 |

149±52 140.50 95-338 |

186±64 170.0 121-271 |

0.027 |

134±25 128.5 91-169 |

174±72 159.0 104-422 |

0.058 |

147±24 153.0 104-192 |

168±30 164.5 125-235 |

0.065 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) mean±SD Median Range |

2.2±3.2 1.3 0.05-16.5 |

2.4±4.2 1.1 0.05-16.5 |

2.1±2.5 1.3 0.08-11.5 |

0.860 |

0.4±0.3 0.3 0.03-1.3 |

3.8±5.3 1.9 0.15-22.7 |

0.001 |

0.3±0.8 0.2 0.03-3.6 |

1.1±2.2 0.4 0.11-9.1 |

0.013 |

0.2±0.2 0.2 0.04-1.1 |

0.6±0.5 0.4 0.05-1.7 |

0.025 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) mean±SD Median Range |

267±322 189.7 6-1614 |

285±342 203.3 6-1614 |

250±309 1390.0 6-1277 |

0.841 |

220±256 155 3-1194 |

274±350 131.1 17-1420 |

1.00 |

158±143 114.0 3-627 |

173±209 142.6 13-860 |

0.824 |

94±86 70.0 13-379 |

70±68 55.5 4-277 |

0.393 |

| D-dimer (ng/dL) mean±SD Median Range |

1047±2498 481.5 192-15000 |

1619±3476 511.5 192-5000 |

475±196 451.5 213-987 |

0.189 |

968±1683445.5 154-7525 |

967±1596 613.5 244-7634 |

0.430 |

850±1393 395.0 190-6333 |

1016±1821 482.5 186-7764 |

0.747 |

374±382 284.5 169-1894 |

387±218 366.5 169-1091 |

0.165 |

| CD11c+/CD86+/IP-10+-expressing cells (M1%) mean±SEM Median Range |

19.0±1.1 19.6 15-22 |

20.1±2.8 19.9 15-26 |

0.914 |

11.8±1.8 12.2 9-14 |

15.7±2.6 14.6 11-23 |

0.118 |

6.4±0.5 6.5 5-8 |

17.3±3.9 15.0 11-28 |

0.008 |

4.3±0.4 4.4 3-6 |

14.9±2.0 13.9 11-20 |

0.011 | |

| CD11b+/CD16hi/CD163+/IDO+-expressing cells (M2%) mean±SEM Median Range |

7.7±1.0 8.0 4-11 |

7.1±2.2 6.8 3-12 |

0.776 |

18.3±2.6 18.5 15-22 |

11.2±1.1 11.1 9-14 |

0.002 |

5.2±1.4 24.6 21-32 |

12.5±0.9 12.3 10-15 |

<0.001 |

26.4±1.5 26.8 20-31 |

14.0±1.8 14.1 11-17 |

<0.001 |

|

| CD4+/CD183+/CD192+/IFN-γ+-expressing cells (Th1%) mean±SEM Median Range |

3.1±0.7 3.2 2 - 4 |

2.5±0.2 2.6 2-3 |

0.103 |

8.7±0.7 9.0 6-10 |

3.6±0.7 3.4 2-5 |

<0.001 |

14.0±0.8 13.1 13-18 |

4.3±0.7 3.9 3-6 |

0.011 |

3.1±0.2 3.2 2-4 |

5.0±0.5 4.8 4-7 |

0.005 |

|

| Summary of Comorbidities | |||||||||||||

| None, n, (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| One, n, (%) | 7 (18) | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2 or More, n, (%) | 32 (80) | 16 (80) | 16 (80) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Clinical Comorbidities | |||||||||||||

| History or current tobacco use, n, (%) | 8 (20) | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | 0.695 | |||||||||

| Overweight, n, (%) | 19 (48) | 11 (55) | 8 (40) | 0.527 | |||||||||

| Obesity, n, (%) | 17 (43) | 6 (30) | 11 (55) | 0.200 | |||||||||

| Hypertension, n, (%) | 10 (25) | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Diabetes, n, (%) | 8 (20) | 2 (10) | 6 (30) | 0.235 | |||||||||

| Dyslipidemia, n, (%) | 6 (15) | 5 (25) | 1 (5) | 0.181 | |||||||||

| Hypertriglyceridemia, n, (%) | 21 (53) | 12 (60) | 9 (45) | 0.527 | |||||||||

| Coronary artery disease, n, (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | |||||||||

| Congestive heart failure, n, (%) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Chronic respiratory disease (emphysema), n, (%) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Asthma, n, (%) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Chronic liver disease (chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis), n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | |||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease, n, (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | |||||||||

| Cancer, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | |||||||||

| Immune deficiency (acquired or innate), n, (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | |||||||||

| Symptoms | |||||||||||||

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 12 (30) | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 8 (40) | 0.155 | 0 (0) | 7 (35) | 0.008 | 1 (5) | 7 (35) | 0.044 |

| Cough, n (%) | 32 (80) | 16 (80) | 16 (80) | 1.00 | 8 (40) | 14 (70) | 0.111 | 6 (30) | 11 (55) | 0.200 | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 1.00 |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 11 (28) | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 1.00 | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 1.00 |

| Rhinorrhea, n (%) | 18 (45) | 7 (35) | 11 (55) | 0.341 | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | 1.00 | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 1.00 |

| Headache, n (%) | 25 (63) | 10 (50) | 15 (75) | 0.191 | 3 (15) | 9 (45) | 0.082 | 3 (15) | 9 (45) | 0.082 | 3 (15) | 8 (40) | 0.155 |

| Sore throat, n (%) | 21 (53) | 10 (50) | 11 (55) | 1.00 | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | 1.00 | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 0.661 | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 1.00 |

| Malaise, n (%) | 21 (53) | 11 (55) | 10 (50) | 1.00 | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 | 4 (20) | 5 (25) | 1.00 |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 21 (53) | 9 (45) | 12 (60) | 0.527 | 4 (20) | 5 (25) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 |

| Myalgia, n (%) | 22 (55) | 10 (50) | 12 (60) | 0.751 | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 1.00 |

| Brain fog, n (%) | 17 (43) | 10 (50) | 7 (35) | 0.523 | 4 (20) | 7 (35) | 0.480 | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 0.661 | 2 (10) | 6 (30) | 0.235 |

| Ageusia, n (%) | 20 (50) | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | 0.752 | 6 (30) | 9 (45) | 0.500 | 3 (15) | 6 (30) | 0.451 | 3 (15) | 5 (25) | 0.695 |

| Anosmia, n (%) | 22 (55) | 11 (55) | 11 (55) | 1.00 | 9 (45) | 10 (50) | 1.00 | 7 (35) | 7 (35) | 1.00 | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 7 (18) | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 0.231 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 2 (5) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 0.661 | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 0.605 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).