Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of studied extremophilic and extremotolerant cyanobacteria strains

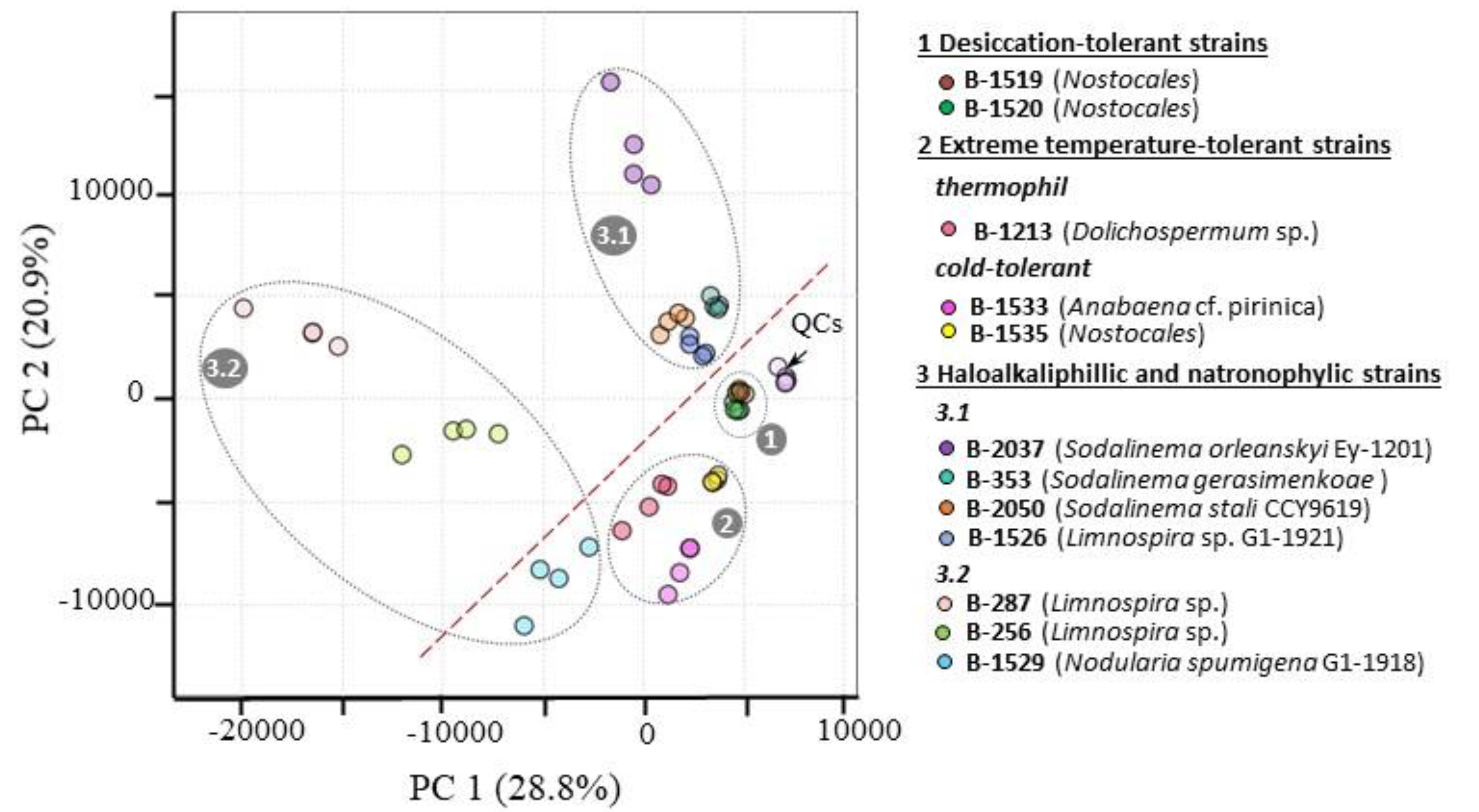

2.2. Characterization of extremophilic and extremotolerant cyanobacteria polar metabolite patterns

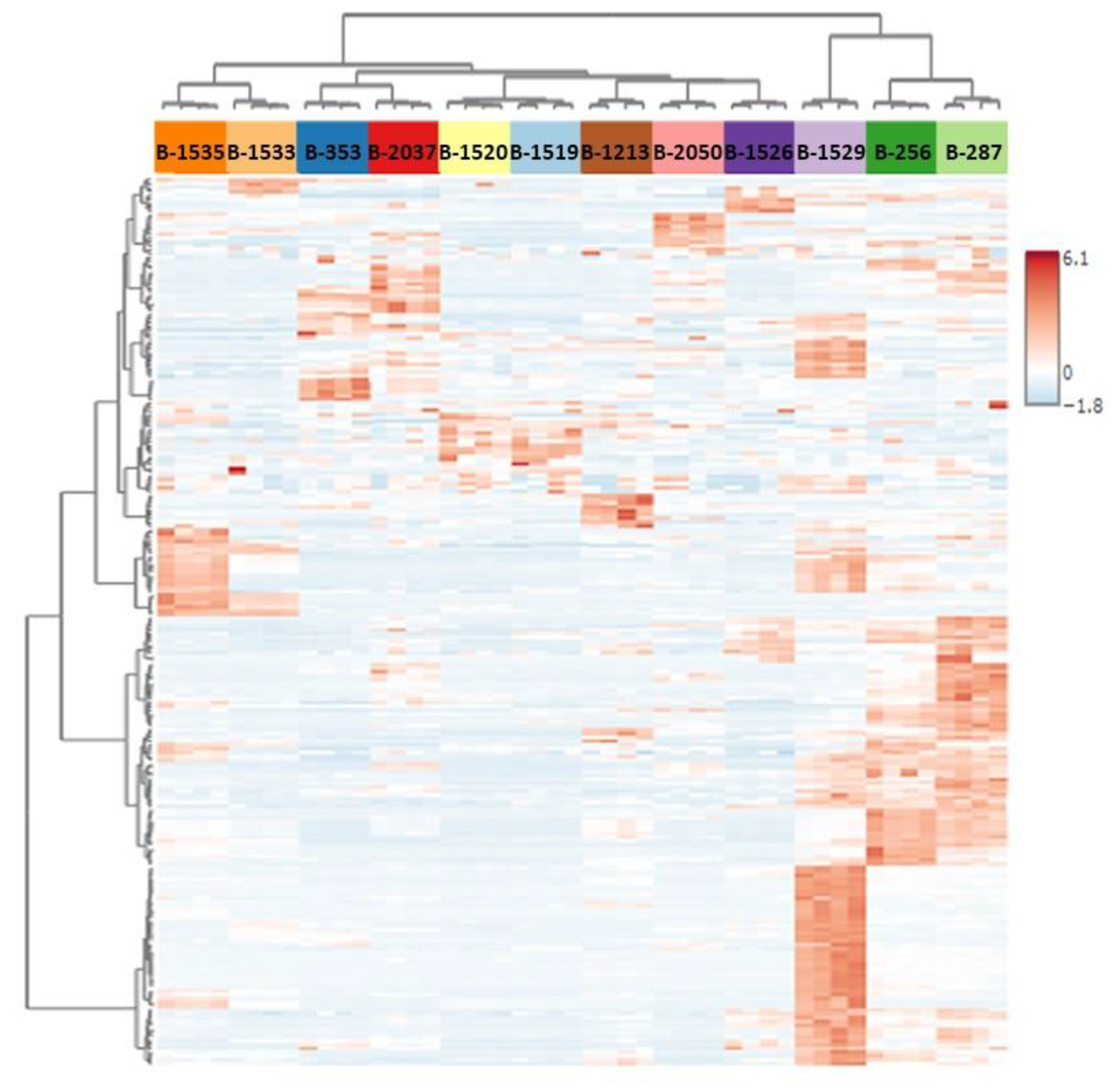

2.3. Identification of strain-dependent variability in the primary metabolome

2.4. Identifying patterns of strain differences in primary metabolome associated with cyanobacteria inhabiting extreme environments

2.4.1. Desiccation-tolerant cyanobacteria strains B-1520 and B-1519

2.4.2. Strains tolerant to high or cold temperatures

2.4.3. Halo(alkali)philic and natronophilic cyanobacteria strains

Strains demonstrating similarity in metabolomes

2.5. Pathway analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. Constitutive patterns of metabolites and their adaptive potential for extremotolerant cyanobacteria

3.2. Constitutive patterns of metabolites and their adaptive potential for haloalko- and natronophiles

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Cyanobacterial strains characterization and cultivation

4.3. GC-MS-based analysis of thermally stable polar metabolites

4.4. LC-MS analysis of thermally labile polar metabolites

4.5. Statistical analysis

4.6. Metabolomic pathway analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Mehner, T. Encyclopedia of inland waters; Academic Press: 2009.

- Demoulin, C.F.; Lara, Y.J.; Cornet, L.; François, C.; Baurain, D.; Wilmotte, A.; Javaux, E.J. Cyanobacteria evolution: Insight from the fossil record. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 140, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waditee-Sirisattha, R.; Kageyama, H. Extremophilic cyanobacteria. In Cyanobacterial Physiology, Elsevier: 2022; pp 85–99.

- Merino, N.; Aronson, H.S.; Bojanova, D.P.; Feyhl-Buska, J.; Wong, M.L.; Zhang, S.; Giovannelli, D. Living at the extremes: extremophiles and the limits of life in a planetary context. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagels, F.; Vasconcelos, V.; Guedes, A.C. Carotenoids from cyanobacteria: Biotechnological potential and optimization strategies. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Prajapat, G.; Abrar, M.; Ledwani, L.; Singh, A.; Agrawal, A. Cyanobacteria as efficient producers of mycosporine-like amino acids. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Prabha, R.; Verma, S.; Meena, K.K.; Yandigeri, M. Antioxidant properties and polyphenolic content in terrestrial cyanobacteria. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, A.; Ruiz, M.; Zhang, C.-C. Oxidative stress in cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Akiyama, A.; Furukawa, R.; Yokobori, S.-i.; Tajika, E.; Yamagishi, A. Evolution of superoxide dismutases and catalases in cyanobacteria: occurrence of the antioxidant enzyme genes before the rise of atmospheric oxygen. J. Mol. Evol. 2021, 89, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Jha, S.; Rana, P.; Mishra, S.; Kumari, N.; Singh, S.C.; Anand, S.; Upadhye, V.; Sinha, R.P. Resilience and mitigation strategies of cyanobacteria under ultraviolet radiation stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. Metabolites facilitating adaptation of desert cyanobacteria to extremely arid environments. Plants 2022, 11, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, M. Mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in cyanobacteria. Eur. J. Phycol. 1999, 34, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A. Diversity of organic osmotic compounds and osmotic adaptation in cyanobacteria and algae. In Algae and cyanobacteria in extreme environments, Springer: 2007; pp 639–655.

- Kirst, G.; Thiel, C.; Wolff, H.; Nothnagel, J.; Wanzek, M.; Ulmke, R. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in icealgae and its possible biological role. Mar. Chem.

- Dasauni, K. ; Divya; Nailwal, T.K. Cyanobacteria in cold ecosystem: tolerance and adaptation. Surviv. Strateg. Cold-Adapt. Microorg.

- Joset, F.; Jeanjean, R.; Hagemann, M. Dynamics of the response of cyanobacteria to salt stress: deciphering the molecular events. Physiol. Plant. 1996, 96, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, H.; Waditee-Sirisattha, R. Osmoprotectant molecules in cyanobacteria: Their basic features, biosynthetic regulations, and potential applications. In Cyanobacterial physiology, Elsevier: 2022; pp 113–123.

- Kageyama, H.; Waditee-Sirisattha, R. Halotolerance mechanisms in salt-tolerant cyanobacteria. In Advances in Applied Microbiology, Elsevier: 2023; Vol. 124, pp 55–117.

- Yadav, P.; Singh, R.P.; Rana, S.; Joshi, D.; Kumar, D.; Bhardwaj, N.; Gupta, R.K.; Kumar, A. Mechanisms of stress tolerance in cyanobacteria under extreme conditions. Stresses 2022, 2, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, M.; Schulz, H.J.; Wagler, D. Rechnergestützte Führung von Fermentationsprozessen, Teil 2. Acta Biotechnol. 1984, 4, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobac-Čik, A.V.; Dulić, T.I.; Stojanović, D.B.; Svirčev, Z.B. The importance of extremophile cyanobacteria in the production of biologically active compounds. Zb. Matice Srp. Za Prir. Nauk. 2007, (112), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgade, B.; Stensjö, K. Synthetic biology in marine cyanobacteria: Advances and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 994365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, N.; Shrivastava, S.; Ghosh, A.; Rawat, V.S.; Sodhi, K.K.; Kumar, M. Perspectives on the microorganism of extreme environments and their applications. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiehn, O. Metabolomics by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry: Combined targeted and untargeted profiling. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2016, 114, 30.4–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xiao, J.F.; Tuli, L.; Ressom, H.W. LC-MS-based metabolomics. Mol. BioSystems 2012, 8, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- t’Kindt, R.; Morreel, K.; Deforce, D.; Boerjan, W.; Van Bocxlaer, J. Joint GC–MS and LC–MS platforms for comprehensive plant metabolomics: Repeatability and sample pre-treatment. J. Chromatogr. B 2009, 877, 3572–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D.; Orf, I.; Kopka, J.; Hagemann, M. Recent applications of metabolomics toward cyanobacteria. Metabolites 2013, 3, 72–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.-L.; Zhang, A.-H.; Kong, L.; Wang, X.-J. Advances in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics for investigation of metabolites. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 22335–22350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, M.; Friedl, T.; Day, J.G. Maintenance of actively metabolizing microalgal cultures. Algal Cult. Tech. 2005, 145, 50011–1. [Google Scholar]

- Yuorieva, N.; Sinetova, M.; Messineva, E.; Kulichenko, I.; Fomenkov, A.; Vysotskaya, O.; Osipova, E.; Baikalova, A.; Prudnikova, O.; Titova, M. Plants, cells, algae, and cyanobacteria in vitro and cryobank collections at the Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences—a platform for research and production center. Biology 2023, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanier, R.Y.; Kunisawa, R.; Mandel, M.; Cohen-Bazire, G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol. Rev. 1971, 35, 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Владимирoва, М.; Барцевич, Е.; Жoлдакoв, И.; Епифанoва, О.; Маркелoва, А.; Маслoва, И.; Купцoва, Е. IPPAS-кoллекция культур микрoвoдoрoслей Института физиoлoгии растений им. КА Тимирязева АН СССР. Каталoг культур кoллекций СССР, М.

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B.; Herdman, M.; Stanier, R.Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. Microbiology 1979, 111, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samylina, O.S.; Sinetova, M.A.; Kupriyanova, E.V.; Starikov, A.Y.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Dziuba, M.V.; Tourova, T.P. Ecology and biogeography of the ‘marine Geitlerinema’cluster and a description of Sodalinema orleanskyi sp. nov. Sodalinema gerasimenkoae sp. nov. Sodalinema stali sp. nov. and Baaleninema simplex gen. et sp. nov.(Oscillatoriales, Cyanobacteria). FEMS, 2021; 97. [Google Scholar]

- Sarsekeyeva, F.K.; Usserbaeva, A.A.; Zayadan, B.K.; Mironov, K.S.; Sidorov, R.A.; Kozlova, A.Y.; Kupriyanova, E.V.; Sinetova, M.A.; Los, D.A. Isolation and characterization of a new cyanobacterial strain with a unique fatty acid composition. Adv. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilova, T.; Lukasheva, E.; Brauch, D.; Greifenhagen, U.; Paudel, G.; Tarakhovskaya, E.; Frolova, N.; Mittasch, J.; Balcke, G.U.; Tissier, A. A snapshot of the plant glycated proteome: structural, functional, and mechanistic aspects. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 7621–7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilova, T.; Paudel, G.; Shilyaev, N.; Schmidt, R.; Brauch, D.; Tarakhovskaya, E.; Milrud, S.; Smolikova, G.; Tissier, A.; Vogt, T. Global proteomic analysis of advanced glycation end products in the Arabidopsis proteome provides evidence for age-related glycation hot spots. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15758–15776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkovska-Stamenova, S.; Schmidt, R.; Frolov, A.; Birkemeyer, C. GC-MS method for the quantitation of carbohydrate intermediates in glycation systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 5911–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcke, G.U.; Bennewitz, S.; Bergau, N.; Athmer, B.; Henning, A.; Majovsky, P.; Jiménez-Gómez, J.M.; Hoehenwarter, W.; Tissier, A. Multi-omics of tomato glandular trichomes reveals distinct features of central carbon metabolism supporting high productivity of specialized metabolites. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 960–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. : Ser. B (Methodol. ) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozieva, A.M.; Khasimov, M.K.; Voloshin, R.A.; Sinetova, M.A.; Kupriyanova, E.V.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Dunikov, D.O.; Tsygankov, A.A.; Tomo, T.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. New cyanobacterial strains for biohydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 7569–7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anishchenko, O.V.; Gladyshev, M.I.; Kravchuk, E.S.; Ivanova, E.A.; Gribovskaya, I.V.; Sushchik, N.N. Seasonal variations of metal concentrations in periphyton and taxonomic composition of the algal community at a Yenisei River littoral site. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2010, 5, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.; Mwatha, W.; Jones, B. Alkaliphiles: ecology, diversity and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.

- Jones, B.E.; Grant, W.D.; Duckworth, A.W.; Owenson, G.G. Microbial diversity of soda lakes. Extremophiles 1998, 2, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samylina, O.S.; Kosyakova, A.I.; Krylov, A.A.; Sorokin, D.Y.; Pimenov, N.V. Salinity-induced succession of phototrophic communities in a southwestern Siberian soda lake during the solar activity cycle. Heliyon.

- Harvey, D.J.; Vouros, P. Mass spectrometric fragmentation of trimethylsilyl and related alkylsilyl derivatives. Mass Spectrom. Rev.

- Golubic, S. Halophily and halotolerance in cyanophytes. Orig. Life 1980, 10, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydro, R.; Kogut, M.; Kushner, D. Salt response of ribosomes of a moderately halophilic bacterium. FEBS Lett. 1975, 60, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacitua, M.; Urrejola, C.; Carrasco, J.; Vicuña, R.; Srain, B.M.; Pantoja-Gutiérrez, S.; Leech, D.; Antiochia, R.; Tasca, F. Use of a thermophile desiccation-tolerant cyanobacterial culture and Os redox polymer for the preparation of photocurrent producing anodes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, F.; You, D.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Daroch, M. Thermophilic cyanobacteria—exciting, yet challenging biotechnological chassis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, N.A.; Pfennig, D.W. Evolution: Ancestral plasticity promoted extreme temperature adaptation in thermophilic bacteria. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R68–R70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y.; Teng, W.-K.; Zhao, L.; Hu, C.-X.; Zhou, Y.-K.; Han, B.-P.; Song, L.-R.; Shu, W.-S. Comparative genomics reveals insights into cyanobacterial evolution and habitat adaptation. ISME J. 2021, 15, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pade, N.; Hagemann, M. Salt acclimation of cyanobacteria and their application in biotechnology. Life 2014, 5, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaru, Y.; Takani, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Sakamoto, T. Crucial role of extracellular polysaccharides in desiccation and freezing tolerance in the terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 7327–7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, B. Glyoxylate induced changes in the carbon and nitrogen metabolism of the cyanobacterium Anabaena cylindrica. Plant Physiol. 1986, 80, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero, A.; Vincenzini, M. Nostoc (cyanophyceae) goes nude: Extracellular polysaccharides serve as a sink for reducing power under unbalanced c/n metabolism 1. J. Phycol. 2004, 40, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, C. Exopolysaccharides from microalgae and cyanobacteria: diversity of strains, production strategies, and applications. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.K.; Pandey, N.; Rai, S.P. Salicylic acid and nitric oxide signaling in plant heat stress. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 168, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadava, P. Salicylic acid alleviates methyl viologen induced oxidative stress through transcriptional modulation of antioxidant genes in Zea mays L. Maydica 2016, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Holuigue, L.; Salinas, P.; Blanco, F.; GarretÓn, V. Salicylic acid and reactive oxygen species in the activation of stress defense genes. Salicylic Acid: A Plant Horm.

- Wani, A.B.; Chadar, H.; Wani, A.H.; Singh, S.; Upadhyay, N. Salicylic acid to decrease plant stress. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 15, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio, A.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Jurado, M.; López, M.; López-González, J.; Moreno, J. Prospection of cyanobacteria producing bioactive substances and their application as potential phytostimulating agents. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 26, e00449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.-F.; Liu, S.-T.; Yan, R.-R.; Li, J.; Chen, N.; Zhang, L.-L.; Jia, S.-R.; Han, P.-P. Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid Increase the Polysaccharide Production of Nostoc flagelliforme via the Regulation of the Intracellular NO Level. Foods 2023, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-y.; Li, Y.-r.; Han, C.-f.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, R.-y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Jia, S.-r.; Han, P.-p. Nitric oxide mediates positive regulation of Nostoc flagelliforme polysaccharide yield via potential S-nitrosylation of G6PDH and UGDH. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, T.; Saud, S.; Gu, L.; Khan, I.; Fahad, S.; Zhou, R. Cyanobacteria: harnessing the power of microorganisms for plant growth promotion, stress alleviation, and phytoremediation in the Era of sustainable agriculture. Plant Stress 2024, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bao, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; He, H. Effect of heterocystous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria against rice sheath blight and the underlying mechanism. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 153, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, R.F.; Huang, Z.; Edwards, D.; Leeson, H.; Peery, W.; Potts, M. Structural characterization of the released polysaccharide of desiccation-tolerant Nostoc commune DRH-1. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Shang, R.; Laba, C.; Wujin, C.; Hao, B.; Wang, S. Structural characteristic of polysaccharide isolated from Nostoc commune, and their potential as radical scavenging and antidiabetic activities. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, A.D.; Perez Gallego, R.; Vreugdenhil, A.; Puthan Veetil, V.; Chroumpi, T.; Hellingwerf, K.J. Genetic engineering of Synechocystis PCC6803 for the photoautotrophic production of the sweetener erythritol. Microb. Cell Factories 2016, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-B.; Dai, X.-M.; Zheng, Z.-Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhan, X.-B.; Lin, C.-C. Proteomic analysis of erythritol-producing Yarrowia lipolytica from glycerol in response to osmotic pressure. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Hayashi, H.; Nishiyama, Y. Systematic characterization of the ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase family in the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4984–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, E.L.; Cervantes-Laurean, D.; Jacobson, M.K. Glycation of proteins by ADP-ribose. ADP-Ribosylation: Metab. Eff. Regul. Funct.

- Vu, C.Q.; Lu, P.-J.; Chen, C.-S.; Jacobson, M.K. 2′-Phospho-Cyclic ADP-ribose, a Calcium-mobilizing Agent Derived from NADP (∗). J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 4747–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Hidese, R.; Matsuda, M.; Ohbayashi, R.; Ashida, H.; Kondo, A.; Hasunuma, T. Glycogen deficiency enhances carbon partitioning into glutamate for an alternative extracellular metabolic sink in cyanobacteria. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J.W.; Yoon, H.-S. Heterocyst development in Anabaena. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003, 6, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halimatul, H.S.M.; Ehira, S.; Awai, K. Fatty alcohols can complement functions of heterocyst specific glycolipids in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambacorta, A.; Romano, I.; Trincone, A.; Soriente, A.; Giordano, M.; Sodano, G. Heterocyst glycolipids from five nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1996, 126, 653–655. [Google Scholar]

- Lucius, S.; Hagemann, M. The primary carbon metabolism in cyanobacteria and its regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1417680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudoh, K.; Hotta, S.; Sekine, M.; Fujii, R.; Uchida, A.; Kubota, G.; Kawano, Y.; Ihara, M. Overexpression of endogenous 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS) in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 accelerates protein aggregation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 123, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, L.A.; McCormick, A.J.; Lea-Smith, D.J. Current knowledge and recent advances in understanding metabolism of the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20193325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, M.; Erdmann, N. Activation and pathway of glucosylglycerol synthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microbiology 1994, 140, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Куприянoва, Е.; Самылина, О. СО 2-КОНЦЕНТРИРУЮЩИЙ МЕХАНИЗМ И ЕГО ОСОБЕННОСТИ У ГАЛОАЛКАЛОФИЛЬНЫХ ЦИАНОБАКТЕРИЙ. Микрoбиoлoгия 2015, 84, 144–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Solanki, R.; Strous, M. In search of the pH limit of growth in halo-alkaliphilic cyanobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, B.; Lindberg, P. Terpenoids and their biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Life 2015, 5, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinetova, M.A.; Los, D.A. New insights in cyanobacterial cold stress responses: Genes, sensors, and molecular triggers. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 2391–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Zhao, S.; Wen, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, X. Analysis of ascomycin production enhanced by shikimic acid resistance and addition in Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. ascomyceticus. Biochem. Eng. J. 2014, 82, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, A.M.; Laviña, W.A.; Putri, S.P.; Fukusaki, E. Accumulation of sugars and nucleosides in response to high salt and butanol stress in 1-butanol producing Synechococcus elongatus. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Herfindal, L.; Jokela, J.; Shishido, T.K.; Wahlsten, M.; Døskeland, S.O.; Sivonen, K. Cyanobacteria from terrestrial and marine sources contain apoptogens able to overcome chemoresistance in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 2036–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humisto, A.; Herfindal, L.; Jokela, J.; Karkman, A.; Bjørnstad, R.; R Choudhury, R.; Sivonen, K. Cyanobacteria as a source for novel anti-leukemic compounds. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2016, 17, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.; Aslim, B. Modification of exopolysaccharide composition and production by three cyanobacterial isolates under salt stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2010, 17, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damrow, R.; Maldener, I.; Zilliges, Y. The multiple functions of common microbial carbon polymers, glycogen and PHB, during stress responses in the non-diazotrophic cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Berendzen, K.W.; Forchhammer, K. On the role and production of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Life 2020, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, E.; Arévalo, S.; Burnat, M. Cyanophycin and arginine metabolism in cyanobacteria. Algal Res. 2019, 42, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehringer, M.M.; Wannicke, N. Climate change and regulation of hepatotoxin production in Cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 88, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermilova, E.; Forchhammer, K. PII signaling proteins of cyanobacteria and green algae. New features of conserved proteins. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 60, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, P.; Rita, D. Sedimentation of Nodularia spumigena and distribution of nodularin in the food web during transport of a cyanobacterial bloom from the Baltic Sea to the Kattegat. Harmful Algae 2019, 86, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, M.C.; Neilan, B.A. Characterization of the nodularin synthetase gene cluster and proposed theory of the evolution of cyanobacterial hepatotoxins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6353–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lage, S.; Mazur-Marzec, H.; Gorokhova, E. Competitive interactions as a mechanism for chemical diversity maintenance in Nodularia spumigena. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankoff, A.; Wojcik, A.; Fessard, V.; Meriluoto, J. Nodularin-induced genotoxicity following oxidative DNA damage and aneuploidy in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 164, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.B.; Odebrecht, C. Effects of salinity and temperature on the growth, toxin production, and akinete germination of the cyanobacterium Nodularia spumigena. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, P.; Fallowfield, H. Effect of irradiance, temperature and salinity on growth and toxin production by Nodularia spumigena. Hydrobiologia 2003, 493, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, E.; Martin-Luna, B.; Bes, M.T.; Fillat, M.F.; Peleato, M.L. An active photosynthetic electron transfer chain required for mcyD transcription and microcystin synthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806. Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchart, P.-E.; Marter, P.; Brinkmann, H.; Quilichini, Y.; Mysara, M.; Petersen, J.; Pasqualini, V.; Mastroleo, F. The genus Limnospira contains only two species both unable to produce microcystins: L. maxima and L. platensis comb. nov. Iscience.

- Kwei, C.K.; Lewis, D.; King, K.; Donohue, W.; Neilan, B.A. Molecular classification of commercial Spirulina strains and identification of their sulfolipid biosynthesis genes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 21, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinetova, M.A.; Kupriyanova, E.V.; Los, D.A. Spirulina/Arthrospira/Limnospira—Three names of the single organism. Foods 2024, 13, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzawa, S.; Keasling, J.D.; Katz, L. Bio-based production of fuels and industrial chemicals by repurposing antibiotic-producing type I modular polyketide synthases: opportunities and challenges. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roulet, J.; Taton, A.; Golden, J.W.; Arabolaza, A.; Burkart, M.D.; Gramajo, H. Development of a cyanobacterial heterologous polyketide production platform. Metab. Eng. 2018, 49, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharasirivat, V.; Jantaro, S. Increased biomass and polyhydroxybutyrate production by Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 overexpressing RuBisCO genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carninci, P.; Nishiyama, Y.; Westover, A.; Itoh, M.; Nagaoka, S.; Sasaki, N.; Okazaki, Y.; Muramatsu, M.; Hayashizaki, Y. Thermostabilization and thermoactivation of thermolabile enzymes by trehalose and its application for the synthesis of full length cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tolerance group | IPPAS ID | Species name | Extreme environment | Storage conditions for cyanobacteria cultivation |

| Desiccation-tolerant |

B-1520 | Nostoc commune | Macrocolony collected from soil surface, Gorodets village, Kaluga obl., Russia. Heterocystous diazotroph. Resistant to desiccation. | BG-11 medium without nitrogen (pH 7.5) [31], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, in an orbital shaker at 22°С during 3 months |

| B-1519 | Nostoc commune | Macrocolony collected from soil surface, Gorodets village, Kaluga obl., Russia. Heterocystous diazotroph. Resistant to desiccation. | BG-11 medium without nitrogen (pH 7.5) [31], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, in an orbital shaker at 22°С during 3 months | |

| High and low temperature tolerant | B-1213 | Dolichospermum sp. | Hot springs, Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic. Heterocystous diazotroph. Thermophile. | BG-11 medium without nitrogen (pH 7.5) [31], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, in an orbital shaker at 22°С during 8 months |

| B-1533 | Anabaena cf. pirinica | Yenisei river, Krasnoyarsk, Russia, Cold-tolerant: able to survive at low temperatures (up to 10–11°C) and high water flow rate. Heterocystous diazotroph. | №6 medium without nitrogen (pH 7.2) [32], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, in an orbital shaker at 22°С during 3 months | |

| B-1535 | Anabaena ‘sphaerica’ | Yenisei river, Krasnoyarsk, Russia, Cold-tolerant: able to survive at low temperatures (up to 10–11°C) and high water flow rate. Heterocystous diazotroph. | №6 medium without nitrogen (pH 7.2) [32], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1,, in an orbital shaker at 22°С during 3 months | |

| Halophilic, haloalkaliphilic and natronophilic | B-2050 |

Sodalinema stalii |

Coastal shoals, Mellum Island, North Sea, Germany. Salinity about 30 g/l. Halophilic. | ASNIII medium (pH 7.5) [33], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, 27°С in a growth chamber MLR-352-PE (Panasonic, Japan) for 3 weeks, then 22°С for 2 months |

| B-2037 | Sodalinema orleanskyi | Salt alkaline lake Eyasi, Tanzania. Haloalkaliphile, natronophile (pHopt 9–10, growth requires 0.2 M NaHCO3 in the medium) | S medium (pH 9.0-9.5) [34], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, 32°С in a growth chamber MLR-351 (SANYO, Japan) for 3 weeks, then 22°С for 2 months | |

| B-353 |

Sodalinema gerasimenkoae | Salt alkaline lake Khilganta, Transbaikal Territory, Russia. Haloalkaliphile, natronophile (pHopt 9–10, growth requires 0.2 M NaHCO3 in the medium) | S medium (pH 9.0-9.5) [34], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, 27°С in a growth chamber MLR-352-PE (Panasonic, Japan) for 3 weeks, then 22°С for 2 months |

|

| B-1526 | Limnospira sp. | Soda Lake Gorchina I, Altai Region, Russia. Haloalkaliphile, natronophile (pHopt 9–10, growth requires 0.2 M NaHCO3 in the medium) | Zarrouk medium (pH 9.5) [35], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, 32°С in a growth chamber MLR-351 (SANYO, Japan) for 6 weeks | |

| B-287 | Limnospira sp. | The origin of the strain is not precisely known. Haloalkaliphile, natronophile (pHopt 9–10, growth requires 2 M NaHCO3 in the medium) | Zarrouk medium (pH 9.5) [35], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, 32°С in a growth chamber MLR-351 (SANYO, Japan) for 6 weeks | |

| B-256 | Limnospira sp. | Bodou Soda Lake, Chad. Haloalkaliphile, natronophile (optimum pH 9–10, growth requires 0.2 M NaHCO3 in the medium) | Zarrouk medium (pH 9.5) [35], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, in a growth chamber MLR-351 (SANYO, Japan) 32°С for 6 weeks | |

| B-1529 | Nodularia spumigena | Soda Lake Gorchina I, Altai Region, Russia. Haloalkaliphile, natronophile (pHopt 9–10, growth requires 0.2 M NaHCO3 in the medium). Heterocystous diazotroph | Zarrouk medium without nitrogen (pH 9.5) [35], light intensity 50 µmol photons m-2 s-1, 27°С in a growth chamber MLR-352-PE (Panasonic, Japan) for 3 weeks, then 22°С for 3 weeks |

| Metabolite a | Chemical classb | TMS derivative (feature)c | Strains tolerant to desiccation: | Method | |||

| B-1520 | B-1519 | ||||||

| FC | pd | FC | p | ||||

| Salicylic acid | Ph | 2TMS | 14 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||

| RI1516 Phenolic compound | Ph | 8.7 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | |||

| Erythritol | P | 4TMS | 4.4 | 0.02 | 6.5 | < 0.001 | GC-MS |

| Ethanolamine | A | 3TMS | 4.2 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||

| Metabolite a | Chem. classb | TMS or MEOX-TMS derivative (#feature)c | Strains tolerant to extreme high or low temperatures: | Method | |||||

| Dolichospermum sp., | Anabaena cf. pirinica, | Anabaena ‘sphaerica’, | |||||||

| B-1213 | B-1533 | B-1535 | |||||||

| thermotolerant | cold-tolerant | cold-tolerant | |||||||

| FC | pd | FC | p | FC | p | ||||

| Glycolic acid | CA | 2.4 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Aconitic acid | CA | 9 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Isocitric acid | CA | 8.3 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| 3-Dehydroshikimic acid | CA | 2.3 | 0.001 | 2.3 | 0.03 | LC-MS | |||

| Glucose | S | 1MEOX, 5TMS (1) | 12 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||||

| 1MEOX, 5TMS (2) | 8.4 | < 0.002 | GC-MS | ||||||

| Sorbitol | P | 6TMS | 3.2 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||||

| 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol | P | 17 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Digalacturonic acid | SA | 5.1 | < 0.001 | 3.8 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||

| Glucose-1-phosphate | SP | 4 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Glucose 6-phosphate | SP | 5.9 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| 1MEOX, 6TMS (1) | 5.9 | < 0.002 | GC-MS | ||||||

| 1MEOX, 6TMS (2) | 6.1 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||||||

| Fructose 6-phosphate | SP | 6.1 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| 1MEOX, 6TMS | 5.1 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||||||

| 2-Keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate | SP | 6 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) | SP | 4.2 | 0.03 | 5.4 | 0.001 | LC-MS | |||

| 2-Deoxyribose 5-phosphate | SP | 3.7 | 0.003 | LC-MS | |||||

| Ribulose-5-phosphate/xylulose-5-phosphate | SP | 3.6 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Phosphate | Pn | 4 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Glutamic acid | AA | 5.3 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Tyrosine | AA | 5.6 | 0.01 | LC-MS | |||||

| Ureidosuccinic acid | AAd | 9.3 | < 0.001 | 9.7 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||

| dTDP | Nuc | 2.6 | 0.006 | LC-MS | |||||

| cGMP | Nuc | 5.8 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| NADH | Nuc | 4.2 | 0.008 | LC-MS | |||||

| ADP-ribose-2`-phosphate | NucS | 8 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| ADP-ribose | NucS | 27 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| Dihydroorotic acid | ON | 4.4 | < 0.001 | LC-MS | |||||

| 2-Hydroxypyridine | ON | 1TMS | 5.6 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||||

| Nonadecan-1-ol | FAl | 1TMS | 9.4 | < 0.001 | GC-MS | ||||

| Metabolitea | Chem. classb | TMS or MEOX-TMS derivative (#feature)c | FCb in abundance increase in a specified strain | Method | |||

| S.orleanskyi | S.gerasime-nkoae | S.stali | Limnospira sp. | ||||

| B-2037 | B-353 | B-2050 | B-1526 | ||||

| Glycolic acid | CA | 2.1 | LC-MS | ||||

| 3-Hydroxypyruvate | CA | 0.34 | LC-MS | ||||

| Lactic acid | CA | 3 | LC-MS | ||||

| 3-Hydroxybutyric acid | CA | 2TMS | 20 | GC-MS | |||

| Isocitric acid | CA | 4.9 | LC-MS | ||||

| 4TMS | 4.9 | GC-MS | |||||

| Shikimic acid | CA | 4.4 | LC-MS | ||||

| 2-Phosphoglycolate | CAP | 6.1 | LC-MS | ||||

| Ribose | S | 1MEOX, 4TMS | 4.1 | GC-MS | |||

| RI2255 Glyceryl-glycoside 1 | S | 6TMS | 10 | GC-MS | |||

| RI2310 Glyceryl-glycoside 2 | S | 6TMS | 6.2 | 8.5 | GC-MS | ||

| Ribonic acid | SA | 6.5 | LC-MS | ||||

| D-Erythronic acid | SA | 4TMS | 2.8 | GC-MS | |||

| Digalacturonic acid | SA | 13 | LC-MS | ||||

| Glycerol | P | 3TMS | 3.5 | GC-MS | |||

| Sedoheptulose-1,7-biphosphate | SP | 5.6 | LC-MS | ||||

| Pyroglutamic acid | AA | 2TMS | 2.7 | GC-MS | |||

| NADPH | Nuc | 8.6 | LC-MS | ||||

| ADP | Nuc | 5.7 | LC-MS | ||||

| CDP | Nuc | 5.8 | LC-MS | ||||

| GDP | Nuc | 4.9 | LC-MS | ||||

| CTP | Nuc | 3.7 | LC-MS | ||||

| dADP | Nuc | 5.1 | LC-MS | ||||

| Adenosine | Nuc | 41 | LC-MS | ||||

| Orotic acid | ON | 5 | LC-MS | ||||

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid (9E) | FA | 1TMS | 9.1 | GC-MS | |||

| delta3-isopentenyl pyrophosphate | PP | 6.4 | LC-MS | ||||

| Phosphoric acid | IO | 3TMS | 2.2 | GC-MS | |||

| Chloride | IO | 2.6 | 2.5 | LC-MS | |||

| Metabolitea | Chem. classb | TMS or MEOX-TMS derivative (#feature)c | FCb in abundance increase in a specified strain | Method | ||

| N. spumigena | Limnospira sp. | |||||

| B-1529 | B-287 | B-256 | ||||

| Propionic acid | CA | 4TMS | 12 | GC-MS | ||

| 2-Phosphoglyceric acid | CAP | 18 | LC-MS | |||

| 3-Phosphoglyceric acid | CAP | 3TMS | 12 | GC-MS | ||

| 14 | LC-MS | |||||

| Phosphoenolpyruvic acid | CAP | 27 | LC-MS | |||

| Fructose | S | 1MEOX, 5TMS (1) | 32 | GC-MS | ||

| 1MEOX, 5TMS (2) | 35 | |||||

| Mannose | S | 1MEOX, 5TMS | 17 | GC-MS | ||

| Galactose | S | 1MEOX, 5TMS | 17 | GC-MS | ||

| Glucose | S | 1MEOX, 5TMS | 14 | GC-MS | ||

| α,α-Trehalose | S | 8TMS | 26 | GC-MS | ||

| D-galactonic acid | SA | 13 | LC-MS | |||

| 1-Deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate | SP | 13 | LC-MS | |||

| 2-Deoxyribose 5-phosphate | SP | 4.5 | 12 | LC-MS | ||

| Sedoheptulose 7-phosphate | SP | 11 | LC-MS | |||

| Glucosamine 6-phosphate | SP | 14 | LC-MS | |||

| Alanine | AA | 10 | GC-MS | |||

| Arginine | AA | 17 | LC-MS | |||

| Arginosuccinate | AA | 11 | LC-MS | |||

| Aspartic acid | AA | 3TMS | 25 | GC-MS | ||

| 11 | LC-MS | |||||

| Serine | AA | 25 | LC-MS | |||

| Threonine | AA | 46 | LC-MS | |||

| Valine | AA | 2TMS | 16 | GC-MS | ||

| Isoleucine | AA | 2TMS | 25 | GC-MS | ||

| Glycine | AA | 2TMS | 24 | GC-MS | ||

| 15 | LC-MS | |||||

| Phenylalanine | AA | 43 | LC-MS | |||

| Tryptophan | AA | 33 | LC-MS | |||

| Tyrosine | AA | 2TMS | 30 | GC-MS | ||

| 3TMS | 12 | |||||

| Methionine | AA | 80 | LC-MS | |||

| Glutamine | AA | 34 | LC-MS | |||

| 3-Ureidopropionic acid | AA | 74 | LC-MS | |||

| Cytidine | Nuc | 14 | LC-MS | |||

| Uridine | Nuc | 21 | LC-MS | |||

| Guanosine | Nuc | 22 | LC-MS | |||

| 2'-Deoxyguanosine | Nuc | 19 | LC-MS | |||

| ATP | Nuc | 10 | LC-MS | |||

| GTP | Nuc | 10 | LC-MS | |||

| Uric acid | ON | 42 | LC-MS | |||

| Isovaleryl-CoA | CoAt | 13 | LC-MS | |||

| Acetoacetyl-CoA | CoAt | 13 | LC-MS | |||

| S-acetyl-CoA | CoAt | 11 | 7 | LC-MS | ||

| trans-9-Octadecenoic acid | FA | 1TMS | 18 | GC-MS | ||

| Linoleic acid | FA | 1TMS | 18 | GC-MS | ||

| Oleic acid | FA | 1TMS | 30 | GC-MS | ||

| cis-9-Hexadecenoic acid | FA | 1TMS | 14 | GC-MS | ||

| delta3-isopentenyl pyrophosphate | PP | 10 | LC-MS | |||

| Dimethylallylpyrophosphate | PP | 10 | LC-MS | |||

| Tolerance group | Species name, IPPAS ID, extreme environment | Storage medium, t°C, storage period | Strain-specifically accumulated metabolites | Metabolic processes |

| Desiccation-tolerant |

Nostoc commune B-1520, heterocystous diazotroph, terrestrial macrocolony | BG-11 without nitrogen, 22°C, 3 months | Salicylic acid Erythritol |

Production of EPS Osmoprotection, component of EPS |

|

Nostoc commune B-1519, heterocystous diazotroph, terrestrial macrocolony |

BG-11 without nitrogen, 22°C, 3 months |

Erythritol | Osmoprotection, component of EPS | |

| High temperature tolerant | Dolichospermum sp. B-1213, heterocystous diazotroph, hot springs | BG-11 without nitrogen, 22°C, 8 months |

ADP-ribose ADP-ribose-2′-P NADH Glucose-1-P Glutamate Tyrosine |

Protein ADP-ribosylation Trigger of Ca-signaling glycogen degradation and redirected carbon flux via glycolysis towards amino acid synthesis |

| Low temperature tolerant up to 10-11°C |

Anabaena cf. pirinica B-1533, heterocystous diazotroph, high-rate cold water flow |

№6 without nitrogen, 22°, 3 months |

Hexoses, hexose phosphates, fatty alcohol; Glycolysis and pentose phosphate intermediates; Ureidosuccinate |

Production of EPS and glycolipids; Enhanced carbon metabolism via glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways; de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis |

|

A. ‘sphaerica’ B-1535, ,heterocystous diazotroph, high-rate cold water flow |

№6 without nitrogen, 22°C, 3 months |

Glycolate | Photorespiration | |

| Haloalkali-philic and natrono-philic | Sodalinema orleanskyi B-2037, saline alkaline lake | S (pH 9.0-9.5) 32°С, 3 weeks, 22°C, 2 months |

Glucosylglycerols; Isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

Osmoregulation; Isoprenoid biosynthesis pathway |

|

Sodalinema gerasimenkoaeB-353, saline alkaline lake |

S (pH 9.0-9.5) 27°С, 3 weeks, 22°C, 2 months |

Shikimate Adenosine |

Aromatic amino acids, phenolic compounds; Not well understood. |

|

|

Sodalinema stali B-2050, halophilic, coastal shoals |

ASNIII, (pH 7.5) 27°С, 3 weeks, 22°C, 2 months |

Glycerol; Orotic acid |

EPS production; de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis |

|

|

Limnospira sp. B-1526, soda lake |

Zarrouk, (pH 9) 32°С, 6 weeks |

Glucosylglycerol; 3-Hydroxybutyric acid |

Osmoprotection; PHB synthesis |

|

|

Nodularia spumigena B-1529, soda lake |

Zarrouk, 27°С, 3 weeks, 22°C, 3 weeks |

Amino acids Compatible solutes (hexoses, sucrose, glucosylglycerol) |

Nodularin biosynthesis (protein protection from oxidative damages or N-storage polymer?); Osmoprotection |

|

|

Limnospira sp. B-287, origin is not known, haloalkaliphile, natronophile |

Zarrouk, (pH 9) 32°С, 6 weeks |

ATP, CoA-thioesters, Isopentenyl-PP; Trehalose |

Biosynthetic processes (polyketide, fatty acid, PHB, isopropanoids); Osmoprotection |

|

|

Limnospira sp. B-256, soda lake |

Zarrouk, (pH 9) 32°С, 6 weeks |

deoxy-pentoses Deoxy-ribonucleotides; UDP-N-acetylglucosamine |

de novo nucleotide synthesis; Cell wall biogenesis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).