Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Sources of Silver Exposure in Humans

1.2. Silver in Direct Contact with Food Substances

1.3. Health Effects of Silver in Humans

1.4. Toxicity Generated by Exposure to Silver and Silver Salts

1.5. Information Concerning the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS)

1.6. Legislation Concerning Values of Metallic Silver, Soluble Silver, and Daily Silver Intake Amounts

1.7. Silver in Dental Applications

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cations Release Assessment

2.2. Cytotoxicity Tests

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Cations Release

3.1.1. Migration of Metallic Silver in Ionic Solutions

3.1.2. Aspects Regarding Migration of Metallic Silver

- − Alloy Composition:

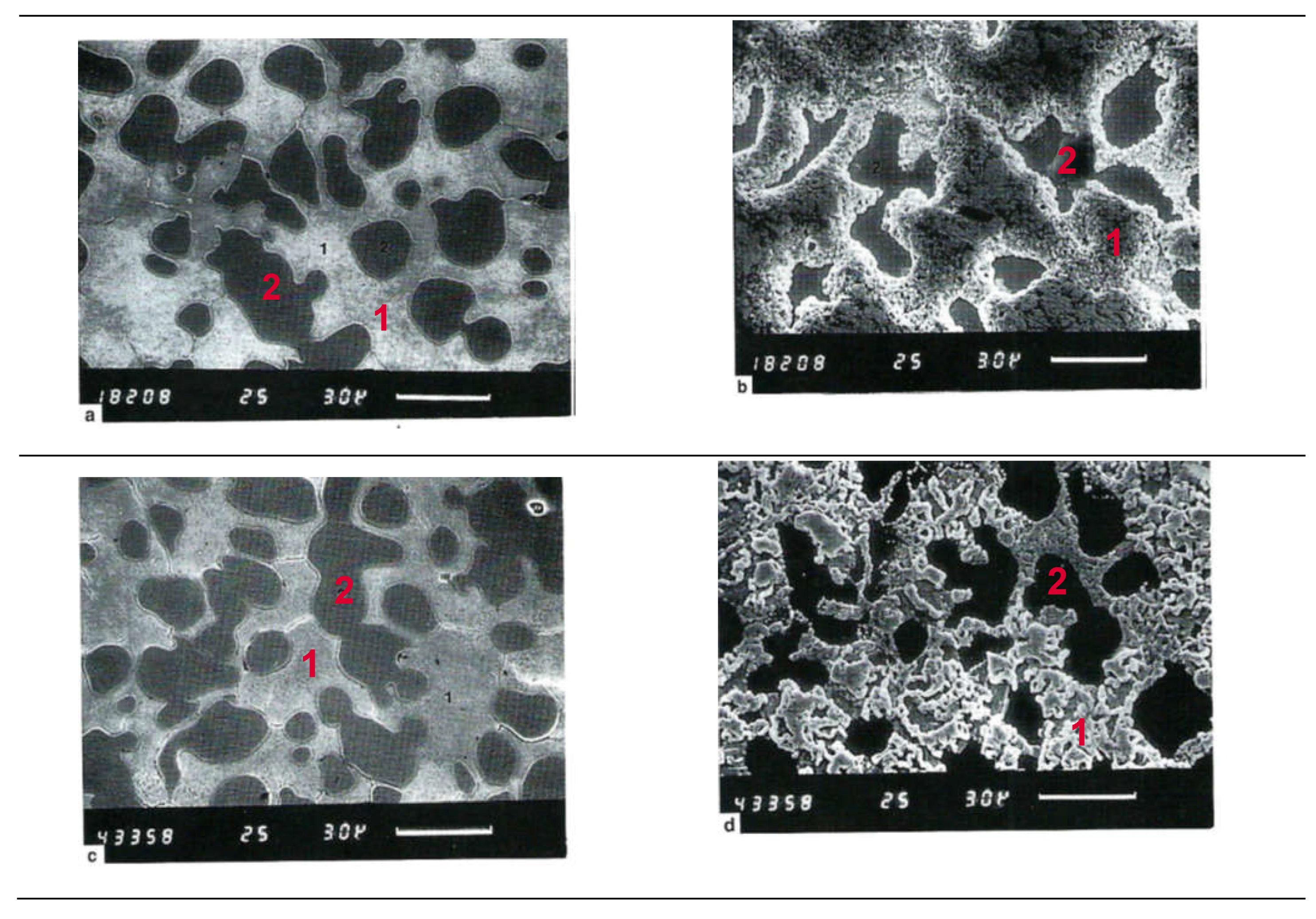

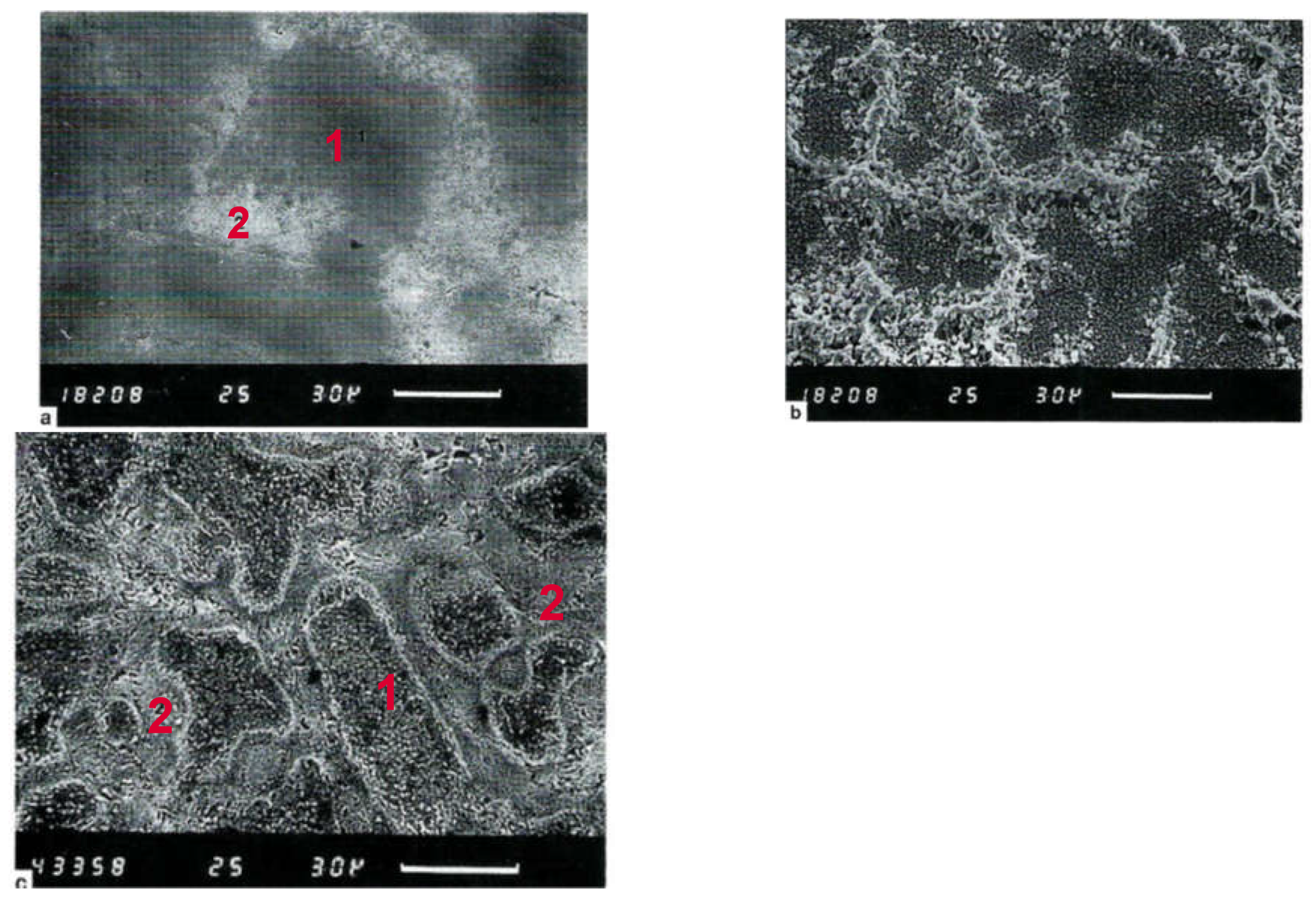

- − Microstructural structure of the alloy:

- − Chemical environment of the solution:

- − Temperature: Higher temperature can accelerate dissolution and corrosion processes, increasing the release of silver ions.

- − Alloy Surface:

- − Alloy tension state: Mechanical stresses or deformations can create local anodic sites, increasing corrosion and leaching of silver ions.

- − Presence of biofilms or biological organisms: The formation of biofilms on the surface of the alloy can influence microbiological corrosion, thereby altering the release of silver ions.

- − Exposure time: The longer the alloy is exposed to an ionic solution, the greater the release of silver ions can be.

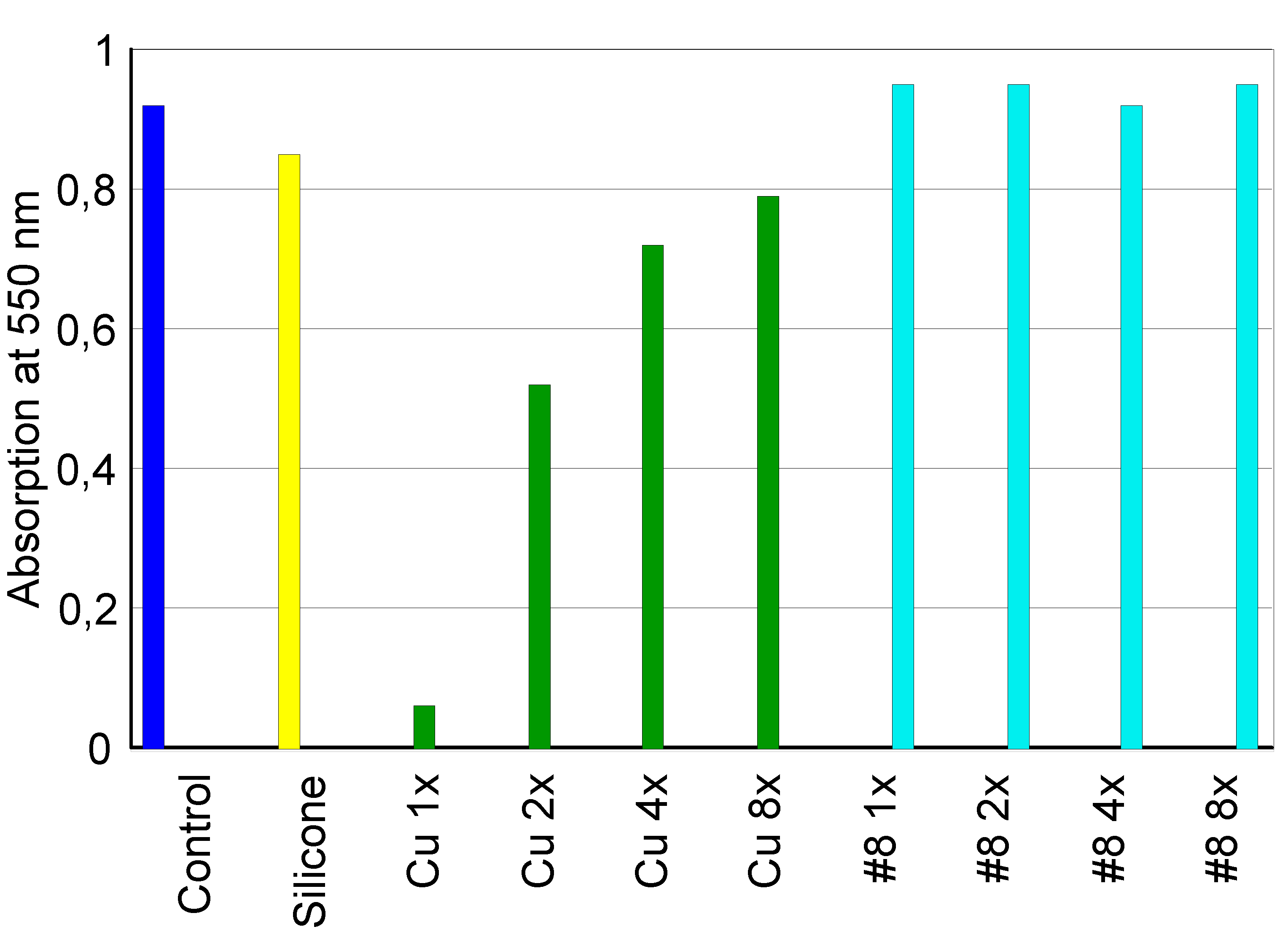

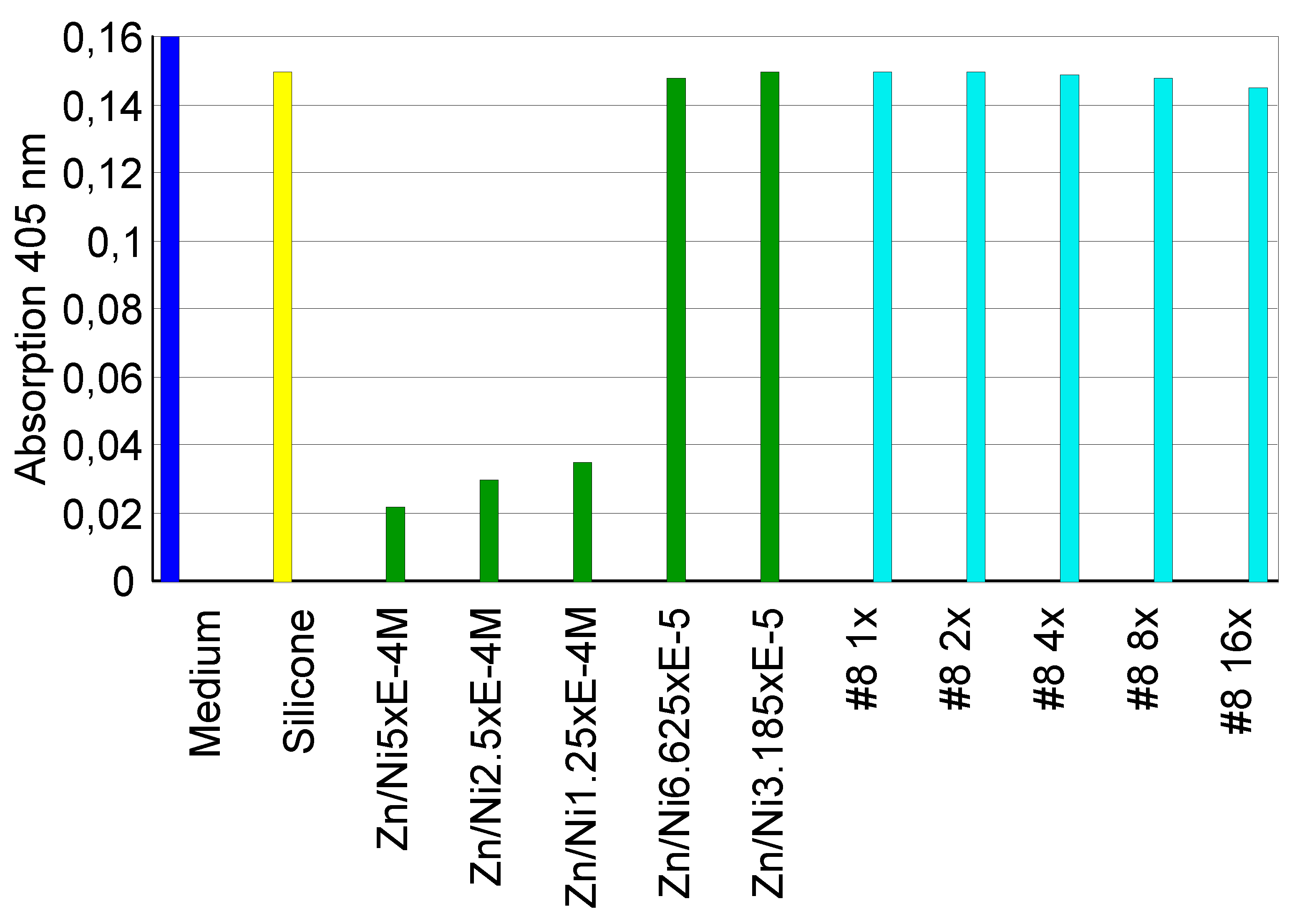

3.2. Impact of Silver on Cytotoxicity

3.2.1. Extract Dilution Method

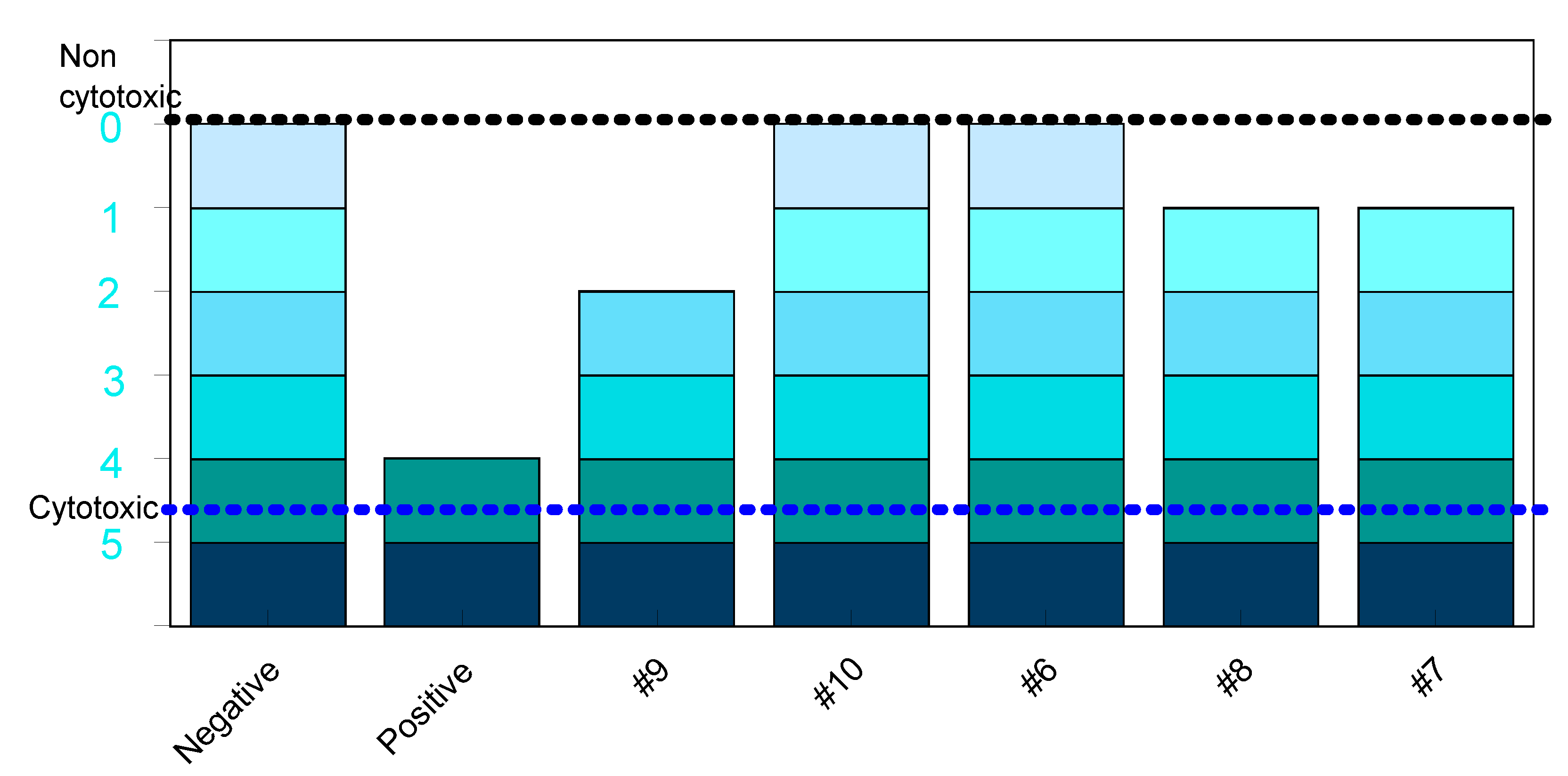

3.2.2. Direct Contact Tests

- −

- "A", alloys that reveal cytotoxicity close to Teflon (90% to 100% cell viability). In this group are silver-palladium-based alloys, gold-rich alloys, and medium-grade gold alloys.

- −

- "B", alloys that reveal a cellular viability of between 70-89% and that do not represent any risk of toxicity in the oral environment. In this group are classified the titanium-based alloys and silver-based alloys.

- −

- "C", alloys that reveal a cellular viability between 45 -69%, therefore represent significant cytotoxicity, and which may represent a risk of toxicity from their use in the mouth.

- −

- "D", alloys that reveal a cell viability < 44%, therefore have a strong cytotoxic response. In this group are classified metals such as nickel, copper and gold-nickel and gold-cadmium alloys.

5. Conclusions

- The quantities of silver detected during the extraction tests were minimal, suggesting no significant concerns related to toxicity;

- Based on the results of cytotoxicity assessment, it has been determined that the silver-based dental alloys included in our study do not pose a risk to the oral cavity when utilized.

- In the future, it may be necessary for dental alloys to be accompanied by a certificate detailing the cations released into an appropriate biological medium. This documentation could pave the way for innovative strategies and guidelines in the development of new methods to protect patients and consumers based on the latest knowledge. It's plausible that as medical standards evolve and our understanding of material science and its biological impacts deepens, such requirements could become more common to better protect patients from potential toxicity or allergic reactions. Such measures would also help in maintaining quality control and traceability of materials used in dental practices.

Supplementary Material

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hill, WR; Pillsbury, D.M. Argyria: the pharmacology of silver. Baltimore, MD, U.SA. Williams & Wilkins Company, 1939.

- Gold, K.; Slay, B.; Knackstedt, M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Antimicrobial activity of metal and metal-oxide based nanoparticles. Advanced Therapeutics 2018, 1, 1700033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemire, J.A; Harrison, J.J.; Turner, R.J. Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applicationsNature Reviews. Microbiology 2013, 11, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.W. History of the medical use of silver. Surgical infections 2009, 10, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkow, G.; Gabbay, J. Copper, An ancient remedy returning to fight microbial, fungal and viral infections. Current Chemical Biology 2009, 3, 272–278. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, S.; Phung, L. T.; Silver, G. Silver as biocides in burn and wound dressings and bacterial resistance to silver compounds. Journal of industrial microbiology and biotechnology 2006, 33, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J. P.; Schneider, R. P. Systemic argyria secondary to topical silver nitrate. Archives of Dermatology 1977, 113, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, W. B.; Shelley, E. D.; Burmeister, V. Argyria: the intrademal “photograph,” a manifestation of passive photosensitivity. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1987, 16, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbranson, S. H.; Hud, J. A.; Hansen, R. C. Argyria following the use of dietary supplements containing colloidal silver protein. Cutis-New York 2000, 66, 373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, F.W. Health hazard from occupational exposure to metallic copper and silver dust. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 1979, 40, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.C.; Roberts, S.M.; Williams, P.L. General principles of toxicology. In Principles of toxicology: environmental and industrial applications, Second edition, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, U.S.A., 2000; pp. 3–4.

- Brooks, S.M. Lung disorders resulting from the inhalation of metals. Clin Chest Med 1981, 2, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, K.D.; Moss, A.; Kon, S. Argyria: clinical implications of exposure to silver nitrate and silver oxide. J Occup Med 1979, 21, 430–435. [Google Scholar]

- Pifer, J.W.; Friedlander, B.R.; Kintz, R.T.; Stockdale, D. K. Absence of toxic effects in silver reclamation workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 1989, 15, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitstadt, R. Occupational exposure limits for metallic silver. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Precious Metals Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 1995, pp. 1–13.

- Williams, N.; Gardner, I. Absence of symptoms in silver refiners with raised blood silver levels. Occup Med 1995, 45, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S. Bacterial silver resistance: molecular biology and uses and misuses of silver compounds. FEMS microbiology reviews 2003, 27, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.T.; Conyers, R.A.; Coombs, C.J.; Masterton, J.P. Determination of silver in blood, urine, and tissues of volunteers and burn patients. Clin Chem 1991, 37, 1683–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catsakis, L.H. , Sulica, V.I. Allergy to silver amalgams. Oral Surg 1978, 46, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Committee of Ministers, European Committee for Food Contact Materials and Articles (CD-P-MCA) 2021. Available online: https://www.edqm.eu/documents/52006/82182/Terms+of+reference+CD-P-MCA.pdf/54ac2c0e-21e6-676c-ee74-98fc5a43364b?t=1640002298681 (accessed 02.10.2024).

- ISO 8442-2 :1997, Matériaux et objets en contact avec les denrées alimentaires - Coutellerie et orfèvrerie de table - Partie 2 : exigences relatives à la coutellerie et aux couverts en acier inoxydable et en métal argenté. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:8442:-2:ed-1:v1:fR (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- ISO 8442-3 :1997, Matériaux et objets en contact avec les denrées alimentaires - Coutellerie et orfèvrerie de table - Partie 2 : exigences relatives à l’orfèvrerie de table et décorative en métal argenté. Available online: https://www.iso.org/fr/standard/2464.html (accessed on 20.11.2024 ).

- Beliles, R.P. The metals. In: Patty’s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. Fourth Edition. Edited by Clayton, G.D. and Clayton, F.E., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, U.S.A., 1994; Volume 2, part C.

- Fowler, B.A.; Nordberg, G.F. Silver. In: Handbook on the toxicology of metals. Second Edition. Elsevier, Amsterdam, New York, Oxford; 1986; Volume 2, pp. 55.

- Gill, P.; Richards, K.; Cho, W. C.; Nagarajan, P.; Aung, P. P.; Ivan, D.; Curry, J.L.; Prieto, V.G.; Torres-Cabala, C. A. Localized cutaneous argyria: Review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 2021, 54, 151776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, S.; Veenstra, D.L.; Sullivan, S.D.; Chenoweth, C.; Fendrick, A.M. The potential clinical and economic benefits of silver alloy urinary catheters in preventing urinary tract infection. Archives of Internal Medicine 2000, 160, 2670–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongioletti, F.; Robert, E.; Buffa, P.; Bertagno, R.; Rebora, A. Blue nevi-like dotted occupational argyria. Journal-American Academy of Dermatology 1992, 27, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, K.D; Seixas, N.; Jacobs, I. Potential nephrotoxic effects of exposure to silver. Br J Ind Med 1987, 44, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żyro, D.; Sikora, J.; Szynkowska-Jóźwik, M.I.; Ochocki, J. Silver, its salts and application in medicine and pharmacy. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 15723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, B. , Luckey, T.D. Metal toxicity in mammals. In Chemical toxicology of metals and metalloids. Plenum Press, New York, U.S.A., 1978; 32–36.

- Aaseth, J.; Olsen, A.; Halse, J.; Hovig, T. Argyria-tissue deposition of silver as selenide. Scan J Clin Lab Invest 1981, 41, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.H. Generalized argyria after habitual use of AgNO3. J Dermatol 1994, 21, 50–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, H.G.A.; Sigel, H. Silver. In Handbook on Toxicity of Inorganic Compounds, Editor Marcel Dekker, New York, U.S.A., 1998; pp. 619–24.

- Fung, M.C.; Bowen, D.L. Silver products for medical indications: risk-benefit assessment. Clin Toxicol 1996, 34, 119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furst, A.; Schlauder, M.C. Inactivity of two noble metals as carcinogens. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 1978, 1, 51–7. [Google Scholar]

- Espinal, M.L.; Ferrando, L.; Jimenex, D.F. Asymptomatic blue nevus-like macule. Diagnosis: localized argyria. Arch Dermatol 1996, 132, 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E.J.; Rungby, J.; Hansen, J.C.; Schmidt, E.; Pedersen, B.; Dahl, R. Serum concentrations and accumulation of silver in skin during three months treatment with an anti-smoking chewing gum containing silver acetate. Hum Toxicol 1998, 7, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, D. Silver poisoning associated with anti-smoking lozenge. Br Med J 1978, 2, 1749–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Garsse, L.; Versieck, J. General argyria caused by administration of tobacco-withdrawal tablets containing silver acetate. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde 1995, 139, 2658–2661. [Google Scholar]

- Gaslin, M. T.; Rubin, C.; Pribitkin, E. A. Silver nasal sprays: misleading Internet marketing. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal 2008, 87, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, N. F.; De Los Bueis, A. B. Ocular argyrosis. Oman Journal of Ophthalmology 2023, 16, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirigliano, F.; Meschia, A.; Taietti, D.; Aliverti, M.; Wu, M.A. Painted in black: deciphering the cornerstones of a challenging case. Internal and Emergency Medicine 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Szymczak, M.; Maciejewska, M.; Laskowski, Ł. ; Laskowska, M; Ostaszewski, R.; Skiba, G.; Franiak-Pietryga, I. All that glitters is not silver—a new look at microbiological and medical applications of silver nanoparticles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021; 22, 854. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadian, N.; Mashoof, R.U.; Khanizadeh, S.; Ghaderi, E.; Farhadian, M.; Miresmaeili, A. Streptococcus mutans counts in patients wearing removable retainers with silver nanoparticles vs those wearing conventional retainers: A randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2016, 149, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, P.L.; Hazelwood, K.J. Exposure-related health effects of silver and silver compounds: a review. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 2005, 49, 575–585. [Google Scholar]

- Silver and Compounds, American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). Available online : https://www.acgih.org/silver-and-compounds/ (accessed on 02.10.2024).

- Hays, S.M.; Aylward, L.L.; LaKind, J.S.; Bartels, M.J.; Barton, H.A.; Boogaard, P.J.; Brunk, C.; DiZio, S.; Dourson, M.; Goldstein, D.A.; Lipscomb, J.; Kilpatrick, M.E.; Krewski, D.; Krishnan, K.; Nordberg, M.; Okino, M. ; Yu-Mei Tan, Y-M.; Viau, C.; Yager, J.W. Guidelines for the derivation of Biomonitoring Equivalents: report from the Biomonitoring Equivalents Expert Workshop. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2008, 51, S4-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent et ses composés, Santé Canada, 2022. Available online : Argent et ses composés — Fiche d’information - Canada.ca (accessed on 02.10.2024). (accessed on 02.10.2024).

- Steck, M.B.; Murray, B.P. SilverToxicity. In StatPearlsPublishing, 2024. Available on line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK604211/ (accessed on 02.11.2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO), Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Second edition, 1993. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259956/9241544600-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20.11.2024 ).

- The French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES) Etude de l’alimentation totale française 2 (EAT 2), Tome 1 : contaminants inorganiques, minéraux, polluants organiques persistants, mycotoxines et phytoestrogènes, 2011. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/fr/system/files/PASER2006sa0361.pdf (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Ambient water quality criteria for silver, 1980. Available online:.

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-03/documents/ambient-wqc-silver-1980.pdf (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Integrated Risk Information System, Silver (CASRN 7440-22-4), 1987. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/static/pdfs/0099_summary.pdf (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO), Directives de qualité pour l’eau de boisson, Deuxième édition, Volume 1, Recommandations, 1995. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259937/9242541680-fre.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO), Silver in drinking-water. Background document for preparation of WHO Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 2003. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wash-documents/wash-chemicals/silver.pdf?sfvrsn=195cf8b3_4 (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO), Directives sur la qualité de l’eau de boisson, Troisieme édition incorporant les 1er et 2e addendum, Volume 1, Recommandations, 2004. Available online: https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/oms_directives_de_qualite_pour_l_eau_de_boisson_vol1_recommendations_2004.pdf (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO), Directives sur la qualité de l’eau de boisson, Quatrième édition, 2017. Available online https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/258887/9789242549959-fre.pdf (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- Gaul, L.E.; Staud, A.H. Clinical spectroscopy. Seventy cases of generalized argyrosis following organic and colloidal silver medication. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1935, 104, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) related to a 7th list of substances for food contact materials. Available on line : https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2005.201a (accessed on 20.11.2024). (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) on a 4th list of substances for food contact materials. The EFSA Journal 2004, 1-17. Available online: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2004.65a (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- Gkioka, M.; Rausch-Fan, X. Antimicrobial Effects of Metal Coatings or Physical, Chemical Modifications of Titanium Dental Implant Surfaces for Prevention of Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Studies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-5:2009. Biological evaluation of medical devices — Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:10993:-5:ed-3:v1:en; accessed on 20.11.2024).

- ISO 10271:2020. Dentistry — Corrosion test methods for metallic materials. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:10271:ed-3:v1:en (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of immunological methods, 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratzner, H. G. Monoclonal antibody to 5-bromo-and 5-iododeoxyuridine: a new reagent for detection of DNA replication. Science, 1982, 218, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Evaluation Conclusion as Required by REACH Article 48 and Evaluation Report for Silver EC No 231-131-3 CAS No 7440-22-4, Evaluating Member State(s): The Netherlands, 2018, REACH. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/776ad739-c591-16fd-2e2c-62b9e50169ee (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- Steppan, J.J.; Roth, J.A.; Hall, L.C.; Jeannotte, D.A.; Carbone, S.P. A review of corrosion failure mechanisms during accelerated tests: electrolytic metal migration. Journal of the electrochemical society 1987, 134, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, K. Silver migration–The mechanism and effects on thick-film conductors. Mater Sci Eng 2003, 234, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Reclaru, L.; Meyer, J. M. Zonal coulometric analysis of the corrosion resistance of dental alloys. Journal of Dentistry 1995, 23, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graig, R.G. Reaction of fibroblast to various dental casting alloy. J. Oral Pathol 1988, 17, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R. G.; Hanks, C. T. Cytotoxicity of experimental casting alloys evaluated by cell culture tests. Journal of Dental Research 1990, 69, 1539–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumgardner, J. D.; Lucas, L. C.; Tilden, A. B. Toxicity of copper-based dental alloys in cell culture. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 1989, 23, 1103–1114.

- Kuhn, A. T.; Rae, T. Aqueous corrosion of Ni-Cr alloys in biological environments and implications for their biocompatibility. British Corrosion Journal 1988, 23, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataha J., C.; Hanks C., T.; Craig R., G. In vitro synergistic, antagonistic, and duration of exposure effects of metal cations on eukaryotic cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1992, 26, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataha, J. C.; Malcolm, C. T.; Hanks, C. T. Correlation between cytotoxicity and the elements released by dental casting alloys. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 1995, 8, 9–14.

- Wataha, J. C.; Craig, R. G.; Hanks, C. T. The release of elements of dental casting alloys into cell-culture medium. J. Dent. Res, 1991, 70, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashi, K.; Imaeda, T.; Kwazoe, Y. Effect om metals ions on the adaptive response induced by methyl-N-Nitrosourea in Escherichia Coli, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1988, 157, 1124–1130.

- Olivier, P.; Marzin, D. Study of Genotoxic Potential 48 Inorganic Derivatives whit the SOS Chromotest, Muation Research 1987, 189, 263–269.

- Kanematsu, N.; Hara, M.; Kada, T. Rec assay and mutagenicity studies on metal compounds. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology, 1980, 77, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusinska, M. , Slamenova D., Effect of Silver Compounds on Invitro Cultured Mammalian Cells, II Study of Genotoxicity and the Effect of DiammineSilver TetraBorate on Macromolecular Synthesis of V79 Cells. Biologia 1990, 45, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Denizeau, F. , Marion, M. . Genotoxic effects of heavy metals in rat hepatocytes. Cell biology and toxicology 1989, 5, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Garraus, A.; Azqueta, A.; Vettorazzi, A.; Lopez de Cerain, A. Genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShan, D.; Ray, P.C.; Yu, H. Molecular toxicity mechanism of nanosilver. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdal Dayem, A.; Hossain, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.; Saha, S.; Yang, G.; Choi, H.; Cho, S. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the Biological Activities of Metallic Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakal, T.C.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, R.S.; Yadav, V. Mechanistic Basis of Antimicrobial Actions of Silver Nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genchi, G.; Carocci, A.; Lauria, G.; Sinicropi, M. S.; Catalano, A. Nickel: Human health and environmental toxicology. h Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 2020 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDD93/42 EEC: Council Directive 93/42/EEC of 14 June 1993 concerning medical devices. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A31993L0042 (accessed on 17.11.2024).

- Soma, T.; Iwasaki, R.; Sato, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Ito, E.; Matsumoto, T.; Kimura, A.; Homma, F.; Saiki, K.; Takahashi, Y.; et al. An ionic silver coating prevents implant-associated infection by anaerobic bacteria in vitro and in vivo in mice. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutinguiza, M.; Fernández-Arias, M.; del Val, J.; Buxadera-Palomero, J.; Rodríguez, D.; Lusquiños, F.; Gil, F.; Pou, J. Synthesis and deposition of silver nanoparticles on cp Ti by laser ablation in open air for antibacterial effect in dental implants. Mater. Lett. 2018, 231, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, G.M.; Esteves, J.; Resende, M.; Mendes, L.; Azevedo, A.S. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Coating of Dental Implants—Past and New Perspectives. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Han, Y.; Lu, Z.; Qin, G.; Zhang, E. Effect of nano/micro-Ag compound particles on the bio-corrosion, antibacterial properties and cell biocompatibility of Ti-Ag alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, H.; Bakitian, F.; Neilands, J.; Andersen, O.Z.; Stavropoulos, A. Antimicrobial Properties of Strontium Functionalized Titanium Surfaces for Oral Applications, A Systematic Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noga, M.; Milan, J.; Frydrych, A.; Jurowski, K. Toxicological aspects, safety assessment, and green toxicology of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)—critical review: state of the art. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, J.; Van Miert, E.; Siciliani, L.; Cheyns, K.; Blaude, M.N.; Wouters, C.; Waegeneers, N.; Bernsen, R.; Vleminckx, C.; Van Loco, J.; Verleysen, E. Application of silver-based biocides in face masks intended for general use requires regulatory control. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 870, 161889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) No 528/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2012 concerning the making available on the market and use of biocidal products, Official Journal of the European Union L 167, 27 June 2012, pp. 1–123. Avilable online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2012/528/oj (accessed on 17.11.2024).

| Alloy code | Chemical composition in % weight | |||||

| Au | Pt | Pd | Ag | Cu | Zn | |

| #1 | 75.0 | 9.0 | - | 9.2 | 3.0 | - |

| #2 | 72.0 | 3.0 | - | 13.6 | 10.4 | - |

| #3 | 56 | - | 12.0 | 28.0 | - | - |

| #4 | 51 | - | 7.0 | 27.0 | 0.14 | - |

| #5 | 2.0 | - | 32.9 | 58 | 3.5 | - |

| #6 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 20.6 | 59.0 | 11.3 | 2.0 |

| #7 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 27.4 | 58.5 | 10.4 | 1.5 |

| #8 | - | - | 24.9 | 59.0 | 14.0 | 2.0 |

| #9 | 54.8 | - | 6.2 | 26.0 | 10.9 | 2.1 |

| #10 | 58.8 | - | 4.8 | 22.4 | 12.9 | 1.1 |

| Alloy #1 | Alloy #2 | Alloy #3 | Alloy #4 | Alloy #5 | |||||||||||

| [*] | [**] | σ | [*] | [**] | σ | [*] | [**] | σ | [*] | [**] | σ | [*] | [**] | σ | |

| Ag | 55 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 82 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 103 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 314 | 1.17 | 0.15 | 243 | 0.90 | 0.13 |

| Cu | 92 | 0.34 | 0.01 | - | - | - | 83 | 0.31 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Fe | 64 | 0.24 | 30 | 0.11 | - | 24 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 66 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 60 | 0.22 | ||

| Mo | 12 | 0.04 | - | 10 | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| Zn | 30 | 0.11 | - | ||||||||||||

| Au | 1.0 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.7 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.7 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.7 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 0.4 | 0.001 | 0.00 |

| Cr | 4.8 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.8 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 4.5 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 7.5 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 5.4 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| In | 0.4 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 6.3 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.4 | 0.001 | 5.5 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 3.9 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| Pd | 2.2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.1 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 4.4 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Pt | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.2 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Sn | 0.4 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.2 | 0.001 | 8.1 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 18 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ||||

| Alloy code | Quantity of Ag in the chemical composition | Quantity of the released Ag | |

| % weight | [µg/L] | µg/cm2/week | |

| #1 | 9.2 | 55 | 0.20 |

| #2 | 13.6 | 82 | 0.31 |

| #3 | 28.0 | 103 | 0.38 |

| #4 | 27.0 | 314 | 1.17 |

| #5 | 58.0 | 243 | 0.90 |

| Alloy | Concentration (µ/L) | |||||

| Au | Ag | Pd | In | Cu | Zn | |

| 11.8Au 47.7Ag 22.8Pd 6.7In 6.8Zn (Figure 1) | 10 | 330 | 15 | 1.5 | 13 | 85 |

| 1.6Au 62.7Ag 22.5 Pd 1.8In Cu10.6 Zn0.8 (Figure 2) | 53 | 640 | 1680 | - | 465 | 80 |

| Code | Direct#break#contact | By extracts (elution test) | Ranking #break#According ISO 10993-5 | ||

| Cell#break#Viability | Cell#break#Proliferation | Grade of positivity | |||

| #9 | + | +1dil | - | 2nd level | 3 |

| #10 | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| #6 | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| #8 | - | +1dil | - | 1st level | 1 |

| #7 | - | +1dil | - | 1st level | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).