Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Historical Context

3. Methodology

3.1. Criteria for LLM Categorization

- Architectural Composition: A foundational classification, we dissect models based on their architectural core — whether they are primarily encoder-based, decoder-based, or a hybrid of both.

- Functional Role: Stemming from their architecture, models are categorized by their primary functionality, be it understanding text (Interpretive AI), generating text (Generative AI), or transforming text (Transformative AI).

- Application Spectrum: The variety of tasks LLMs excel at, from sentiment analysis (typically encoder models) to content generation (largely decoder models), offer critical insights for our categorization.

3.2. Research Methods

- Literature Review: A thorough exploration of existing literature, spanning original papers, articles, and conference contributions, gave us historical context, current trends, and potential future directions.

- Model Analysis: Practical assessments of prominent models like BERT, GPT-3, T5, and others provided direct insights into their capabilities and limitations.

- Expert Engagement and Community Feedback: Interaction with NLP experts and the wider community through seminars, forums, and discussions enriched our theoretical insights with practical experiences and considerations.

4. Transformer Architecture: The Backbone of LLMs

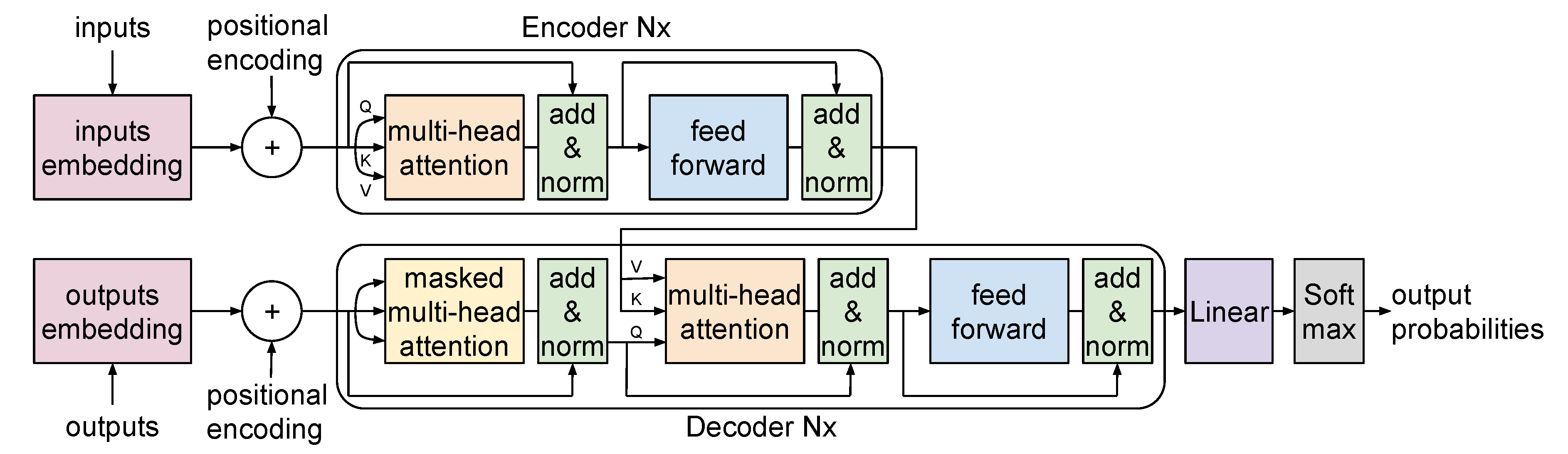

4.1. A Glimpse of the Transformer

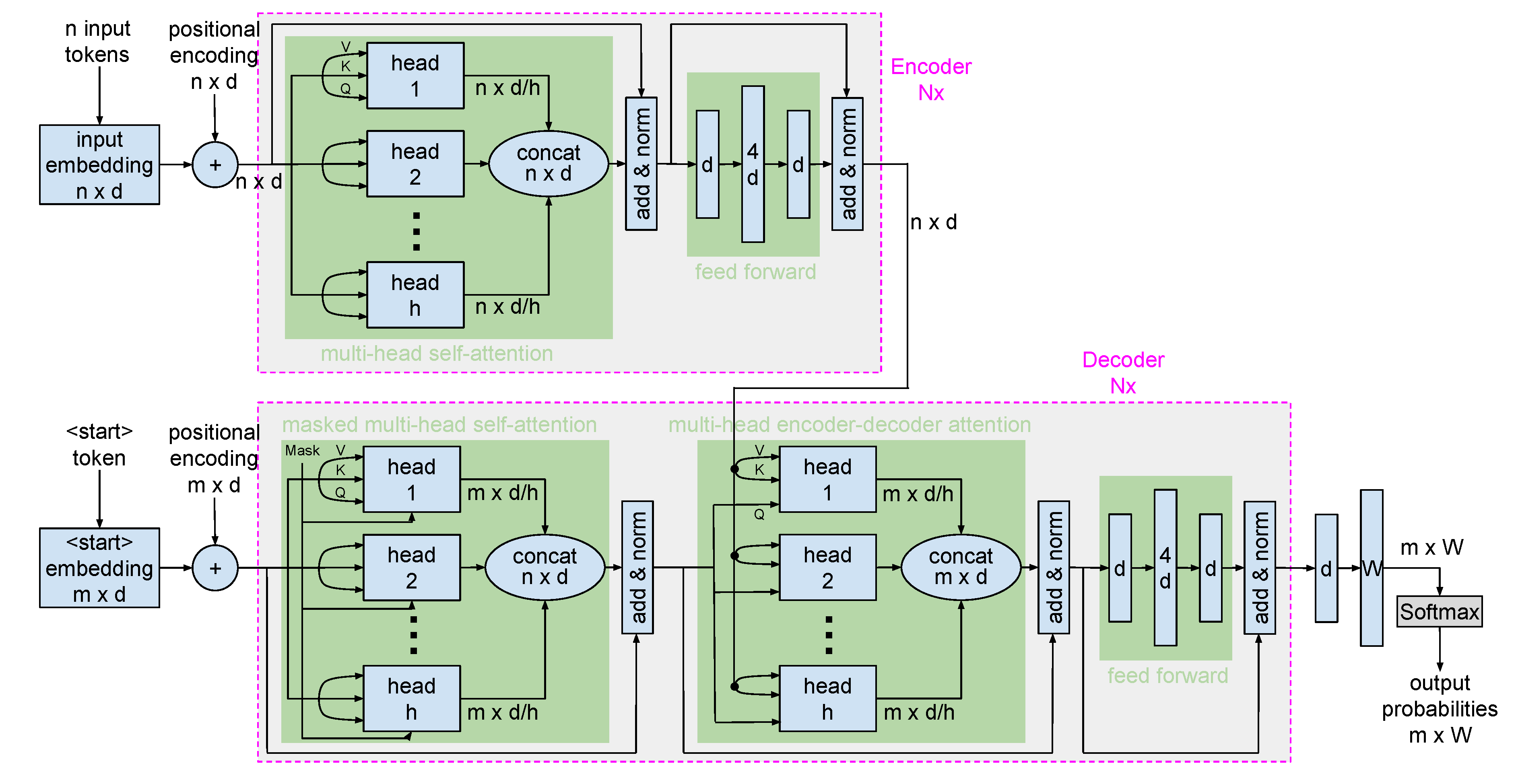

4.2. Data Flow and Architectural Details

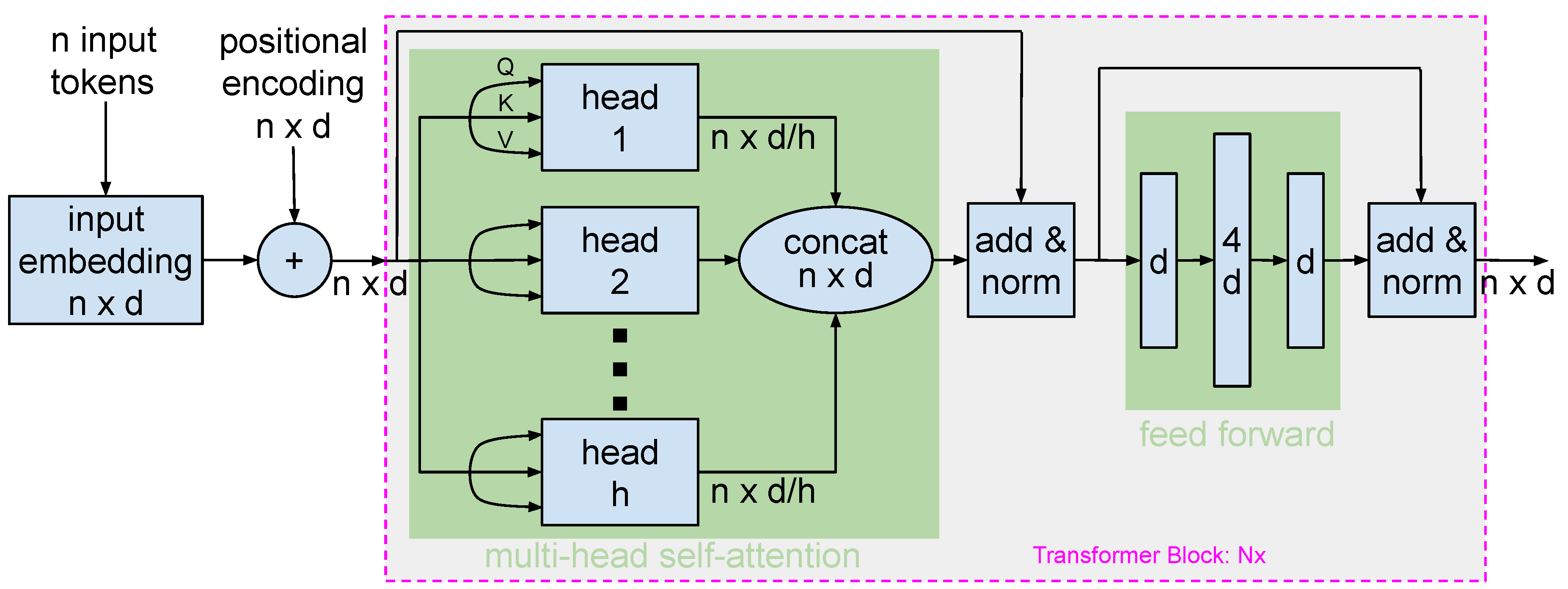

- Input embeddings: Input words are converted into tokens size of n. Convert these tokens into embeddings using a learned embedding matrix. The resulting matrix has dimensions , where d is the embedding size. For each position in the sequence (from 0 to ), generate positional encodings of size [See Appendix B for methods of generating position encodings]. Add these encodings to the token embeddings to get input embeddings of size .

-

Encoder: The encoder consists of several identical layers, denoted as layers, which are stacked one after the other, and the output of one layer is passed to the next as its input. Each encoder layer comprises:

- -

- Multi-head Self-Attention Mechanism: The input embeddings are transformed into Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) matrices. The attention scores are computed using the scaled dot product between Q and K. These scores signify the importance or emphasis each word places on every other word in the sequence. These raw scores are then passed through the softmax function to yield attention weights. The attention output is derived as the product of these weights and the V matrix. The process can be represented by:where denotes the dimension of the key. The attention outputs from all heads are concatenated and linearly transformed, then added to the original input embeddings using a residual connection. This is followed by layer normalization. The size of the resulting matrix is .

- -

- Feed-Forward Networks: The normalized outputs are sent through feed-forward networks, which can have one or more hidden layers. The output from these networks is then combined with the input through a residual connection, followed by layer normalization. The resultant output size is .

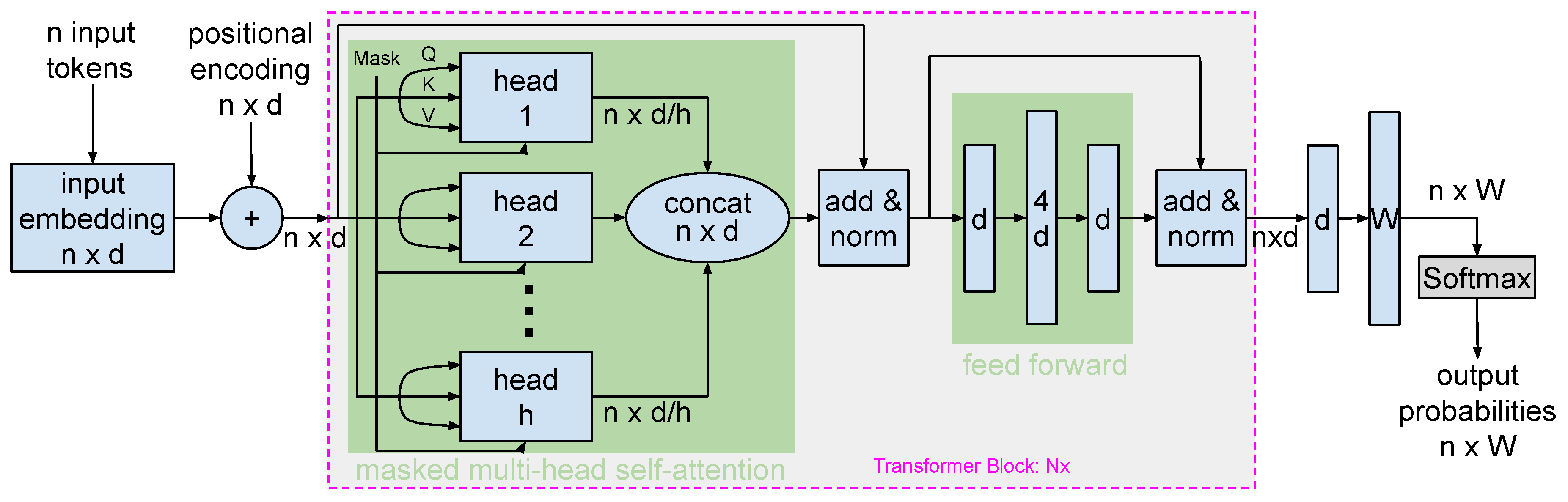

- Target embeddings: Target words are converted into tokens of size m. Convert these tokens into embeddings using a learned embedding matrix. The resulting matrix has dimensions , where d is the embedding size. For each position in the sequence (from 0 to ), generate positional encodings of size . Add these encodings to the token embeddings to produce target embeddings of size .

-

Decoder: The decoder, like the encoder, is made up of several identical layers (denoted as ). Each decoder layer comprises:

- -

-

Masked Multi-head Self-Attention: The self-attention mechanism in the decoder mirrors that of the encoder. However, there are two key differences: the Q, K, V matrices are derived from target embeddings, and the attention is masked to ensure that each token can only attend to prior tokens in the sequence. This masking mechanism is represented as:In this equation, the Mask matrix contains extremely negative values for positions that should not be attended to, such as future tokens in an autoregressive setting. After passing through the softmax function, these positions approach zero, effectively ignoring those positions in the weighted sum.

- -

- Encoder-Decoder Attention: This layer of attention enables the decoder to focus on different parts of the encoder’s output. The Q matrix is derived from the output of the previous masked self-attention layer, whereas K and V are taken from the encoder’s output. The attention output is computed using equation 1. By allowing the decoder to refer back to the encoder’s output, the model can utilize the context provided by the encoder. This mechanism is pivotal for tasks such as machine translation where the decoder needs to generate sequences based on the encoder’s context.

- -

- Feed-Forward Networks: After the attention mechanisms, the output is passed through feed-forward neural networks. The output from these networks is then combined with the input from the previous layer using a residual connection and then normalized. The final output size remains .

-

Final Layers:

- -

- Linear Layer: The output from the final decoder layer (size ) passes through a linear layer that has a weight matrix of size , where W is the vocabulary size. This transforms the output to size .

- -

- Softmax Activation: Applied to the above output, producing a probability distribution over the vocabulary for each position in the output sequence. The result remains .

- -

- Final Output: A matrix of size representing predicted probabilities for each token in the output sequence at each position.

4.3. The Transformative Impacts of the Transformer

- Parallelization: Avoiding recurrent layers, Transformers empower parallel data processing, expediting training and accommodating larger models.

- Versatility: Suited for both encoding (as with BERT) and decoding (as with GPT) tasks, and even combined approaches (e.g., T5, BART), its adaptability covers a broad NLP spectrum.

- Performance Benchmarking: Transformers have raised the bar in various NLP tasks, from machine translation to sentiment analysis.

5. LLM Spectrum: A Thorough Categorization

5.1. Interpretive AI (iAI)

5.1.1. Mechanics of Encoder-Based Models

5.1.2. Comparative Analysis of iAI Models

5.1.3. Drawbacks and Criticisms of iAI Models

- Computational Intensity: Particularly the larger variants are computationally intensive, requiring powerful GPUs or cloud infrastructures.

- Opaque Decision-making: iAI models might produce answers without transparent rationale, creating challenges in critical applications.

- Bias: These models can manifest biases from their training data, potentially leading to skewed results [27].

- Overfitting: Their complexity creates risks of overfitting to training data, possibly affecting performance on new data.

5.2. Generative AI (gAI)

5.2.1. Mechanics of Text Generation

5.2.2. Comparative Analysis of gAI Models

5.2.3. Ethical Concerns and Implications of gAI

- Misinformation and Fake News: gAI models can be exploited to produce misleading information or entirely fabricated news articles, posing challenges for identifying truth in the digital age [30].

- Impersonation: These models can be employed to craft realistic sounding emails or messages, potentially being used in phishing attacks or other forms of deception.

- Bias and Stereotyping: If trained on biased data, gAI can perpetuate harmful stereotypes, leading to further misinformation or cultural insensitivity.

- Loss of Originality: As content generation becomes increasingly automated, there’s a philosophical debate about the erosion of human creativity and the value of machine-generated art or literature.

5.3. Transformative AI (tAI)

5.3.1. Balancing Encoding and Decoding

5.3.2. Comparative Analysis of tAI Models

5.3.3. Current Perspectives on tAI Limitations

6. In-Depth Analysis of Foundational Models

6.1. BERT for iAI

6.1.1. BERT Architecture and Data Flow

- Model Size: BERT’s base architecture contains 12 layers (transformer blocks), 768 hidden units, and 12 attention heads, summing up to approximately 110 million parameters.

- Input Representations: BERT’s inputs are token sequences from texts, further complemented by special tokens: [CLS] (for classification tasks) and [SEP] (to demarcate segments). These embeddings combine token, segment, and position embeddings.

- Transformer Blocks: BERT’s core consists of transformer blocks, with each featuring a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward neural network. Surrounding each main component are residual connections followed by layer normalization.

- Attention Mechanism: BERT’s attention mechanism, bidirectional in nature, focuses variably on different tokens. With 12 attention heads in the base model, each word has 12 unique attention weight sets.

- Position-wise Feed-forward Networks: Present in each transformer block, these networks treat each position separately. Both the input and output layers match the input embedding size, while the hidden layer is 4x larger. GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) serves as the activation function.

- Output: The [CLS] token’s output is suitable for classification, while outputs related to specific tokens can be used for tasks like named entity recognition.

6.1.2. BERT Pre-Training and Fine-Tuning

- BERT’s pre-training capitalizes on the Masked Language Model (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP). In MLM, BERT masks and then predicts roughly 15% of sentence words. For NSP, BERT detects if a second sentence naturally succeeds the first. Pre-trained BERT models are available from open source platforms such as Hugging Face.

- These models can be further refined for specific tasks by introducing task-specific layers to the pre-trained model.

- Constructing a BERT equivalent from scratch requires considerable resources, expertise, and time.

6.2. GPT for gAI

6.2.1. GPT Architecture and Data Flow

- Model Size: This version of GPT-3 consists of 96 layers (transformer blocks), 2048 hidden units, and 16 attention heads per block, totaling approximately 175 billion parameters.

- Input Representations: GPT-3 employs token and positional embeddings for input data representation. These embeddings help capture the sequence and context of the input.

- Transformer Blocks: GPT-3’s core lies in its transformer blocks, which encompass a multi-head self-attention mechanism and feed-forward neural networks. Each component features residual connections followed by layer normalization.

- Attention Mechanism: The masked multi-head self-attention mechanism enables GPT-3 to attend to preceding words for next-word prediction. This attention processes text uni-directionally, capturing past context. This is a clear distinction from the BERT model, where attention is bidirectional, enabling it to understand the context from both the preceding and following words in a sentence.

- Position-wise Feed-forward Networks: Each block has feed-forward networks operating per position. These networks use the GELU activation function and maintain a hidden layer size four times that of the input embedding.

- Output: The last transformer block’s outputs are directed through a linear layer, matching the input embedding size. This output is subsequently passed through a softmax function to yield a vocabulary-spanning probability distribution, determining the next predicted word.

6.2.2. GPT Pre-Training and Fine-Tuning

- Initially, GPT is trained on a vast corpus, aiming to predict the next word in a sequence. This process enables the model to grasp the language’s inherent patterns and structures.

- Unlike many models which require task-specific fine-tuning post pre-training, GPT uniquely generalizes across multiple tasks. By understanding detailed prompts, GPT can efficiently execute diverse tasks without additional fine-tuning.

- GPT can operate in zero-shot, one-shot, or few-shot scenarios by incorporating examples within the input prompt to perform tasks. In this context, "zero-shot" refers to performing tasks without any provided examples, "one-shot" involves using a single example to understand a task, and "few-shot" leverages several examples to understand and execute a task.

- Given GPT’s complexity, creating an equivalent model from scratch would require substantial resources.

6.3. T5 for tAI

6.3.1. T5 Architecture and Data Flow

- Model Size: T5 is available in multiple sizes, but the largest, T5-11B, boasts 11 billion parameters, enabling it to set benchmarks in numerous NLP tasks.

- Input Representations: T5 employs a tokenization strategy that breaks text into subwords, which are then translated into embeddings. Positional embeddings are combined with these token embeddings to ensure sequence coherence.

- Encoder: Comprising 24 transformer blocks, the encoder captures intricate context from the input. The multi-head self-attention mechanism within these blocks allows for the careful assessment of token significance when encoding. Additionally, each transformer block embeds a feed-forward network for processing token representations.

- Decoder: Initiated with a <start> token (e.g., for text summarising tasks) or target output tokens (e.g., for translation tasks), the decoder leverages embeddings analogous to the encoder. The decoder houses its own suite of transformer blocks, each equipped with self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms to ensure contextually relevant decoding. Feed-forward networks are also embedded within these blocks to further process token data.

- Output: Post decoding, the output undergoes transformation through linear layers and a softmax activation to derive word probabilities. Depending on these probabilities, word selections are made, with options to introduce variability for more dynamic outputs like in generative AI.

6.3.2. T5 Pre-Training and Fine-Tuning

- Initially, T5 is trained on a vast text corpus. By reimagining every NLP task as text-to-text during this phase, T5 learns to transform input text sequences into fitting output sequences, thereby gaining a broad and versatile linguistic understanding.

- Post pre-training, while most models undergo task-specific fine-tuning, T5’s text-to-text paradigm simplifies this process. Every task, be it sentiment analysis or translation, is treated as a transformation of one text form to another, making T5 an adaptable model for a wide range of tasks.

- T5’s capabilities extend to zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot learning. Such capability, coupled with its foundational training and the text-to-text model, empowers it to interpret and execute tasks based on minimal examples or prompts.

- Building a model of T5’s stature from the ground up demands significant resources, both computational and expertise-wise, attesting to the strides made in NLP and the investment in crafting such advanced models.

7. Quality Assessment of Generated Texts

- Human Evaluation: A subjective but essential method where human raters assess the quality, relevance, and coherence of generated content.

- Entity and Topic Verification: Ensure the presence of desired themes or entities using methods like topic modeling, named entity recognition, and keyword matching.

- Avoidance of Undesired Outputs: Curtail harmful or biased content through techniques such as fine-tuning, rule-based filtering, and user feedback. Automate the detection process with tools like sentiment analysis or other dedicated models.

- Consistency and Coherence: Ensure logical structure and non-contradictory content. Check embedding similarity across sentences or analyze connected components in entity-relationship graphs.

- Diversity Measurement: Prevent monotonous AI outputs by evaluating the ratio of unique words to total words or by checking embedding similarity and clustering.

-

Quantitative Metrics: These metrics provide an objective and standardized assessment of text quality, distinguishing them from the more subjective or heuristic evaluations.

- -

- BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy): BLEU checks how many n-grams in the generated content match those in the reference text. It favors precision and is more about "out of all the n-grams in my generated output, how many are correct?" The score also incorporates a brevity penalty, discouraging overly short or incomplete translations.

- -

- ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation): ROUGE calculates the overlap of n-grams between generated and reference content. It favors recall and is more about "out of all the n-grams in the reference, how many did I capture in my generated output?" There are several variants of ROUGE, including ROUGE-N (overlap of n-grams), ROUGE-L (longest common subsequence), and ROUGE-S (skip-bigram).

- -

- METEOR (Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering): More sophisticated than BLEU, METEOR considers precision and recall, synonymy, stemming, and even word order, and therefore, offers a more holistic evaluation.

- -

- BERTScore: It uses the power of BERT’s contextual embeddings. By comparing the embeddings of the generated text and reference text, BERTScore captures semantic similarities that other metrics might miss. It provides precision, recall, and F1-scores. Typically, the F1-score is used as the representative BERTScore value if not stated otherwise.

- -

- Perplexity: It is a measure for probabilistic models like language models, and does quantify how well the model’s probability distribution aligns with the true distribution of the words in the text. A lower perplexity indicates a better fit, meaning the model is less "surprised" or "perplexed" by the given text.

8. Ethical Considerations and Criticisms

8.1. Biases in LLMs

- Data-Originated Biases: As LLMs undergo training on massive datasets typically derived from the internet, they are susceptible to inheriting societal biases present in this data. These biases range from racial and gender stereotypes to socio-economic disparities [27].

- Amplification of Biases: LLMs, in some contexts, might not only mirror but intensify pre-existing biases. This can result in outputs that show a higher degree of bias than the training data [37].

- Presumption of Objectivity: The algorithmic foundations of LLMs can mislead users into assuming their outputs are impartial, overlooking over the potential for biased information.

8.2. Potential Misuse and Mitigation Strategies

- Fake News and Disinformation: The generative ability of AI models can be misemployed to create convincing yet wholly spurious news articles, driving disinformation campaigns.

- Impersonation and Phishing: Cutting-edge models can author communications that adeptly imitate genuine human-crafted content, thereby elevating risks in domains such as email phishing.

- Dependency and Over-reliance: An unchecked reliance on LLMs, especially within decision-making fields, could erode human judgment and supervision. Critical sectors like healthcare, finance, and law increasingly utilize LLMs. However, relying solely on model outputs without human judgment can result in severe consequences. For instance, in medical diagnostics, LLM recommendations should complement, not replace, expert opinions. Similarly, financial or legal decisions based solely on model outputs might overlook contextual nuances, leading to potentially flawed outcomes. It’s imperative for users to interpret LLM results with a thorough understanding, integrating them with domain-specific knowledge.

- Fine-tuning on Curated Data: Models trained on meticulously curated datasets can reduce biases, aligning outputs more faithfully with societal ideals and ethics [38].

- Transparent Model Training: Open-sourcing both the model training protocols and the datasets introduces transparency, facilitating the pinpointing of bias and inaccuracies. Furthermore, understanding attention mechanisms helps make the model more transparent by showing how it weighs different words. This allows us to see into its decision-making and find any bias or mistakes.

- User Education: By providing end-users with knowledge about LLMs’ confines and inherent biases, a more thoughtful engagement with their outputs can be encouraged.

- Regulation and Oversight: Regulatory frameworks can demarcate boundaries for LLM utilization, establishing ethical commitments and limiting misuse.

- Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF): Incorporating RLHF into the mechanics of text generation enriches the output’s quality and relevance. Once an initial model is trained, human evaluators can refine it by providing explicit feedback or even ranking multiple generated text outputs. This feedback fine-tunes the text generation capabilities of the model. Moreover, RLHF addresses challenges by mitigating biases, upholding contextual appropriateness, and ensuring safety measures in the generated content.

9. Future Prospects

9.1. Current Limitations and Areas for Improvement

9.2. Anticipated Future Developments

10. Conclusions

Appendix A. Attention Mechanism in Transformers

Appendix A.1. Preliminaries

- Query (Q): It corresponds to the current word or token being considered. The Query matrix seeks to understand which parts (or words/tokens) of the input sequence are relevant in the context of the current word.

- Key (K): The Key matrix is used to represent every word or token in the input sequence. It essentially provides a representation against which the Query matrix can be compared to determine the relevance of each word in the sequence.

- Value (V): Once the relevance (or attention scores) of each word in the sequence is computed by comparing the Query with all Keys, the Value matrix provides the actual values (or word representations) that are used in the weighted sum to produce the final attention output for the current word.

Appendix A.2. Computation Steps

- Step 1: Obtain Q, K, V matrices: First, we derive the Q, K, and V matrices using learned weight matrices , , and respectively.

- Step 2: Calculate Attention Scores: To determine the attention scores, compute the dot product between the Query and Key matrices. For self-attention, both the query and key come from the same previous layer output.

-

Step 3: Scale the Attention Scores: The scores are scaled down by a factor of the square root of the depth of the key vectors (often denoted as ).This scaling helps in stabilizing the gradients, especially for larger values of .

- Step 4: Apply Softmax: The scaled scores are then passed through a softmax operation to obtain the attention weights. This ensures the weights are between 0 and 1, and they sum up to 1.

- Step 5: Multiply by Value matrix: To get the final attention output, multiply the attention weights with the Value matrix:

Appendix B. Positional Encoding in Transformers

Appendix B.1. Formulation

Appendix B.2. Intuition

Appendix B.3. Usage in Transformers

References

- R. Schwartz et al. Green ai. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1907.10597, 2019.

- OpenAI. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

- OpenAI. Introducing chatgpt. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt, 2022.

- T. B. Brown et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2005.14165, 2020.

- Google. An overview of bard: an early experiment with generative ai. https://ai.google/static/documents/google-about-bard.pdf, 2023.

- J. Devlin et al. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2019.

- T. Wolf et al. Huggingface’s transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1910.03771, 2020.

- E. Callaway. ‘it will change everything’: Deepmind’s ai makes gigantic leap in solving protein structures. Nature 588, 203-204, 2020.

- J. M. Tshimula et al. Characterizing financial market coverage using artificial intelligence. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2302.03694, 2023.

- J. Weizenbaum. Eliza—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM, pp.36–45, 1966.

- M. Collins. Log-linear models, memms, and crfs. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:18582888, 2011.

- T. Mikolov et al. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1301.3781, 2013.

- J. Pennington et al. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages: 1532–1543, 2014.

- A. Vaswani et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 5998–6008, 2017.

- T. Le Scao et al. Bloom: A 176b-parameter open-access multilingual language model. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2211.05100, 2022.

- R. Thoppilan et al. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2201.08239, 2022.

- S. Smith et al. Using deepspeed and megatron to train megatron-turing nlg 530b, a large-scale generative language model. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2201.11990, 2022.

- H. Touvron et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2307.09288, 2023.

- S. Reed et al. A generalist agent. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2205.06175, 2022.

- Anthropic. Introducing claude. https://www.anthropic.com/index/introducing-claude, 2023.

- G. Penedo et al. The refinedweb dataset for falcon llm: Outperforming curated corpora with web data, and web data only. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01116, 2023. arXiv:2306.01116, 2023.

- THUDM. Chatglm-6b. https://github.com/THUDM/ChatGLM-6B, 2023.

- J. Devlin et al. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

- Y. Liu et al. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1907.11692, 2019.

- V. Sanh et al. Distilbert, a distilled version of bert: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1910.01108, 2019.

- Z. Zhang et al. Xlnet for named entity recognition. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2002.00260, 2020.

- N. Mehrabi et al. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1908.09635, 2019.

- L. Ouyang et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2203.02155, 2022.

- N. Keskar et al. Ctrl: A conditional transformer language model for controllable generation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1909.05858, 2019.

- R. Zellers et al. Defending against neural fake news. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1905.12616, 2019.

- I. Sutskever et al. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1409.3215, 2014.

- C. Raffel et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1910.10683, 2019.

- A. Chowdhery et al. Palm: scaling language modeling with pathways. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2204.02311, 2022.

- M. Lewis et al. Bart: denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1910.13461, 2019.

- X. Zhang et al. Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2015.

- R. Socher et al. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2013.

- S. Paun et al. Comparing bayesian models of annotation. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018.

- T. Gebru et al. Datasheets for datasets. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1803.09010, 2020.

- N. Shazeer. Glu variants improve transformer. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2002.05202, 2020.

- I. Turc et al. Well-read students learn better: On the importance of pre-training compact models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1908.08962, 2019.

- NVIDIA. Fastertransformer. https://github.com/NVIDIA/FasterTransformer, 2023.

- G. Xiao et al. Smoothquant: Accurate and efficient post-training quantization for large language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2211.10438, 2022.

- A. Radford et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. Openai Blog, 1(8):9, 2019.

| Model | Full Name | Developer | Year | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | Transformer | 2017 | tAI | |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers | 2018 | iAI | |

| DistilBERT | Distilled version of BERT | HuggingFace | 2019 | iAI |

| T5 | Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer | 2019 | tAI | |

| XLNet | Extended Transformer Network | 2019 | iAI | |

| RoBERTa | Robustly optimized BERT approach | Meta AI | 2019 | iAI |

| BART | Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformers | Meta AI | 2019 | tAI |

| GPT-2 | Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2 | OpenAI | 2019 | gAI |

| CTRL | Conditional Transformer Language Model | Salesforce | 2019 | gAI |

| GPT-3 | Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 | OpenAI | 2020 | gAI |

| LaMDA | Language Model for Dialogue Applications | 2021 | gAI | |

| MT-NLG | Megatron-Turing Natural Language Generation | NVIDIA/Microsoft | 2021 | gAI |

| BLOOM | BigScience Large Open-science Open-access Multilingual Language Model | BigScience | 2022 | gAI |

| PaLM | Pathways Language Model | 2022 | gAI | |

| GATO | Generalist Agent | 2022 | gAI | |

| chatGPT | GPT-3.5 variant for chat applications | OpenAI | 2022 | gAI |

| chatGLM | Chat version of General Language Model | Tsinghua | 2023 | gAI |

| Claude | Claude | Anthropic | 2023 | gAI |

| Falcon | Falcon | TIIUAE | 2023 | gAI |

| BARD | Bard | 2023 | gAI | |

| LLaMA | Large Language Model Meta AI | Meta AI | 2023 | gAI |

| GPT-4 | Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 | OpenAI | 2023 | gAI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).