Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

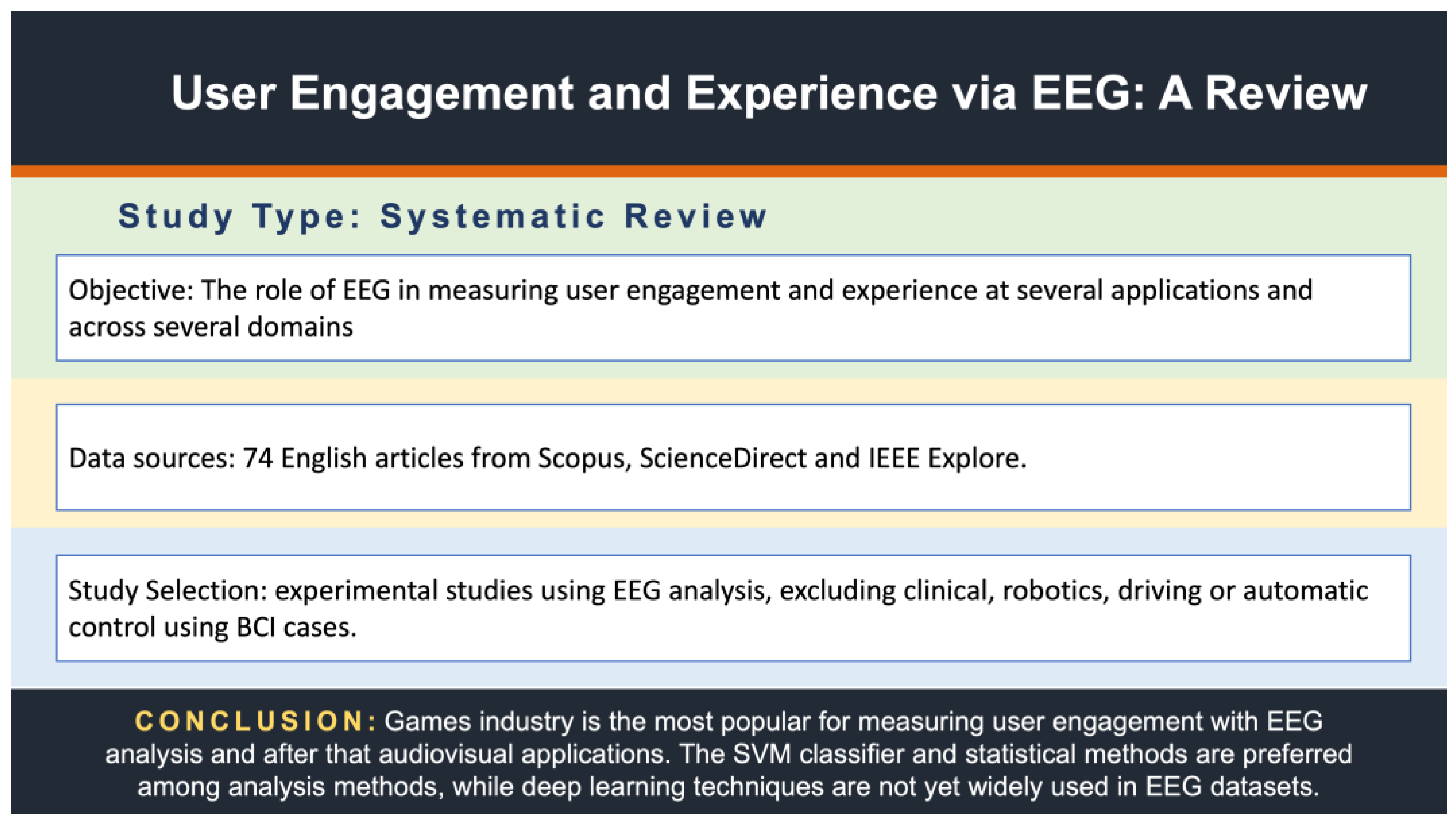

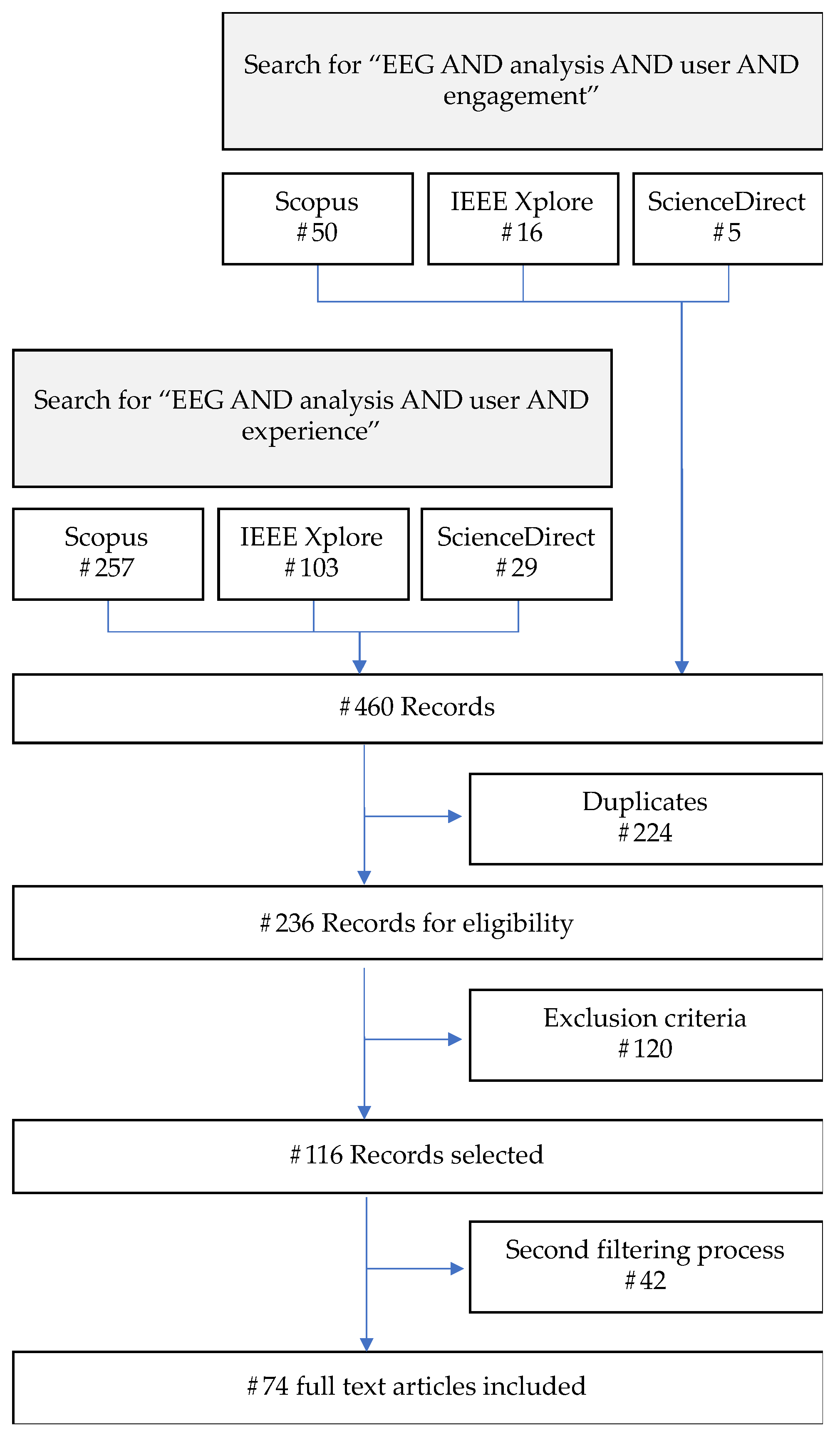

This review paper explores the intersection of user engagement and user experience studies with Electroencephalography (EEG) analysis by investigating the existing literature in this field. User engagement describes the immediate, session-based experience of using interactive products and is commonly used as a metric to assess the success of games, online platforms, applications, and websites, while user experience encompasses the broader and longer-term aspects of user interaction. This review focuses on the use of EEG as a precise and objective method to gain insights into user engagement. EEG recordings capture brain activity as waves, which can be categorized into different frequency bands. By analyzing patterns of brain activity associated with attention, emotion, mental workload, and user experience, EEG provides valuable insights into user engagement. The review follows the PRISMA statement. The search process involved an extensive exploration of multiple databases, resulting in the identification of 74 relevant studies. The review encompasses the entire information flow of the experiments, including data acquisition, pre-processing analysis, feature extraction, and analysis. By examining the current literature, this review provides a comprehensive overview of various algorithms and processes utilized in EEG-based systems for studying user engagement and identifies potential directions for future research endeavors.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Delta Waves (0.5-4 Hz) that are associated with deep sleep and unconsciousness, and their presence during wakefulness can indicate a brain injury. Therefore, they are not usually associated with engagement or emotions.

- Theta Waves (4-8 Hz) that are associated with drowsiness, daydreaming, and meditative states. They are also associated with emotional processing and memory formation. An increase in theta waves has been linked to positive emotions, such as happiness and relaxation.

- Alpha Waves (8-13 Hz) that are associated with relaxation, calmness, and focused attention. They are also associated with a decrease in sensory processing and a reduction in distractibility. An increase in alpha waves is often observed when individuals are engaged in activities that they find enjoyable or calming.

- Beta Waves (13-30 Hz) that are associated with focused attention, concentration, and cognitive processing. An increase in beta waves is often observed when individuals are engaged in tasks that require high levels of concentration, such as problem-solving or decision-making.

- Gamma Waves (30-100 Hz) that are associated with high levels of cognitive processing, perception, and attention. They are also associated with peak emotional experiences, such as excitement, happiness, and joy.

2. Research Methodology

- Study objectives, where the overall aim and objectives are being examined.

- Study population, including the number of subjects or reporting the EEG open database that is used.

- Experimental protocol, describing the experiment that was used for EEG data acquisition.

- Methodology, including the preprocessing step, the feature extraction, the classification/statistical analysis.

- Results and conclusion, including the findings from the study.

- Using EEG for automatic control (Brain Computer Interface).

- Subjects of the experimental protocol including patients, disabled people, infants, and drivers.

- Application of the EEG study to rehabilitation, Intensive Care Unit, and surgery.

- Application of the EEG study to meditation.

3. Results

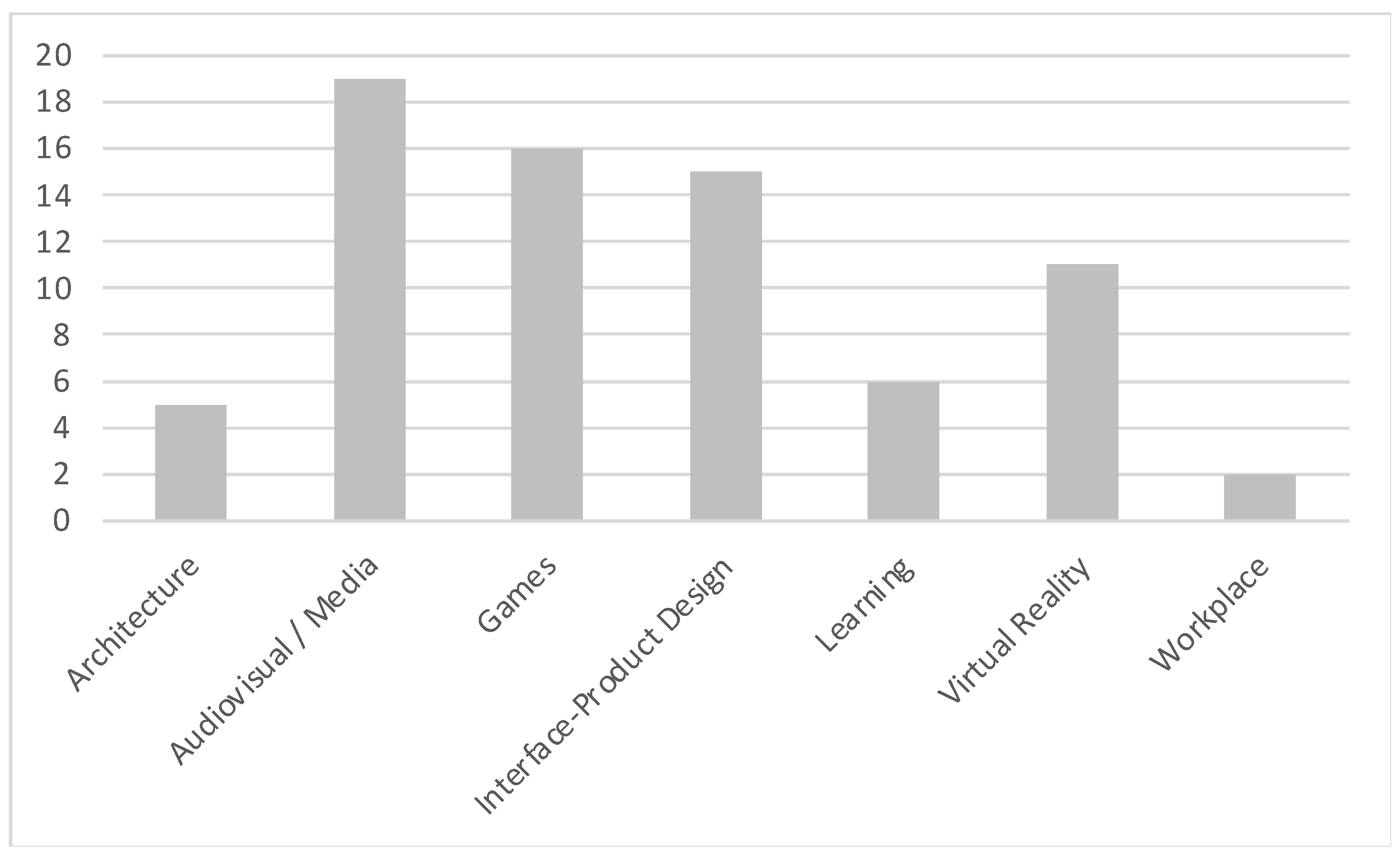

3.1. Application Field

3.2. Study Design and Instruments for Data Acquisition

3.3. Pre-Processing Analysis

| Step | References |

|---|---|

| Filtering | [11,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,30,33,34,35,43,45,47,49,51,54,58,60,61,62,63,65,66,68,70,78,81,82,84,87,88,90] |

| Artifact removal | [12,16,19,23,24,25,26,30,43,44,45,49,51,52,54,55,57,61,65,66,68,70,75,81,84,86,90] |

| Epoching | [15,16,23,51,52,58,61,65,78,81,86,87] |

| Independent Component Analysis | [12,15,16,24,34,43,51,58,61,62,63,65,68,70,87,88,90] |

| Referencing | [15,16,17,24,30,34,49,51,58,61,65,81,87,90] |

| Baseline correction | [14,24,28,33,51,58,62,65,68,78,82,84,88] |

| Downsampling | [18,30,34,43,49,61,68] |

3.3.1. Filtering

3.3.2. Artifact Removal

3.3.3. Epoching

3.3.4. Independent Component Analysis (ICA)

3.3.5. Referencing

3.3.6. Baseline Correction

3.3.7. Downsampling

3.4. Feature Extraction and Selection

3.4.1. Time-Domain Methods

3.4.2. Frequency-Domain Methods

3.4.3. Time-Frequency-Domain Methods

3.4.4. Spatial-Feature Based Methods

3.4.5. Feature Selection Methods

3.5. Analysis of EEG Recordings

3.5.1. Statistical Analysis

3.5.2. Machine Learning

- Brain-Computer Interface (BCI): Machine learning methods are widely used in BCI applications to classify EEG signals and decode user intentions. These methods can be used to analyze EEG data in real-time and make predictions based on the user's brain activity, which can be used to control external devices or applications.

- Cognitive Neuroscience: Machine learning methods are increasingly used in cognitive neuroscience research to analyze EEG data and identify patterns of brain activity associated with different cognitive processes or tasks. These methods can be used to model the complex relationships between brain activity and cognitive variables, such as attention, memory, or decision-making.

- Clinical Neurology: Machine learning methods are also used in clinical neurology applications, such as diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders, such as epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, or depression. These methods can analyze EEG data to identify biomarkers and predict disease progression or treatment outcomes.

- Neuromarketing: Machine learning methods are used in neuromarketing research to analyze EEG data and identify patterns of brain activity associated with consumer preferences and decision-making. These methods can be used to optimize marketing strategies and product designs based on the user's brain activity.

3.5.3. Graph Theory

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Literature Review Findings

4.2. Soft and Full Emerging Technologies

4.3. Comparative Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sutcliffe, A. Designing for User Experience and Engagement. in Why Engagement Matters. Springer, Springer International Publishing, 2016. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, E.G.; H.L.; Toms, “What is User Engagement? A Conceptual Framework for Defining User Engagement with Technology. Journal of the American Society for Information Science & Technology 2008, 59, 938–955.

- van der Linden, D.; Tops, M.; Bakker, A.B. Go with the flow: A neuroscientific view on being fully engaged. European Journal of Neuroscience 2021, 53, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moënne-Loccoz, R.C.V.C.; Hernández, A.; Larraguibel, C.; Lam, G.; Lorca-Ponce, E.; Montefusco-Siegmund, R.; Maldonado, P. Effects of the self-perceived sensorimotor demand and immersion during video gaming on visual-attention skills. European Journal of Neuroscience 2023, 57, 1870–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, J.J.; Parra, L.C.; Dmochowski, J.P. Visually evoked responses are enhanced when engaging in a video game. European Journal of Neuroscience 2020, 52, 4695–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halderman, L.K.; Finn, B.; Lockwood, J.R.; Long, N.M.; Kahana, M.J. EEG Correlates of Engagement During Assessment. ETS Research Report Series 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X., W.; Liu, T.Z.B.; Guo, J.; Chen, C.L.P. X. W.; Liu, T.Z.B.; Guo, J.; Chen, C.L.P. Fine-grained Interpretability for EEG Emotion Recognition: Concat-aided Grad-CAM and Systematic Brain Functional Network. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. GMSS : Graph-Based Multi-Task Self-Supervised Learning for EEG Emotion Recognition. 1–14.

- Shen, Y.-P. ; Yi-Wei; Lin, “Cross-Day Data Diversity Improves Inter-Individual Emotion Commonality of Spatio-Spectral EEG Signatures Using Independent Component Analysis. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. [CrossRef]

- Y., Z.; Wang, S.C.C.X.; Wang, D.; Gao, X. Y. Z.; Wang, S.C.C.X.; Wang, D.; Gao, X. Enhancing EEG-Based Decision-Making Performance Prediction by Maximizing Mutual Information Between Emotion and Decision-Relevant Features. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; et al. AMDET : Attention based Multiple Dimensions EEG Transformer for Emotion Recognition. 1–10.

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Unsupervised Time-Aware Sampling Network with Deep Reinforcement Learning for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition. 1–12.

- Ding, Y.; Member, S.; Robinson, N.; Zhang, S. TSception : Capturing Temporal Dynamics and Spatial Asymmetry From EEG for Emotion Recognition. IEEE Trans Affect Comput 2023, 14, 2238–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, L. PR-PL : A Novel Transfer Learning Framework with Prototypical Representation based Pairwise Learning for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition. 1–12, 2022.

- Shemesh, A.; Leisman, G.; Bar, M.; Grobman, Y.J. The emotional influence of different geometries in virtual spaces: A neurocognitive examination. J Environ Psychol 2022, 81, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Ergan, S. Evaluating the effectiveness of biometric sensors and their signal features for classifying human experience in virtual environments. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, H.; Choo, S. Article effects of changes to architectural elements on human relaxation-arousal responses: Based on vr and eeg. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergan, S.; Radwan, A.; Zou, Z.; Tseng, H.-A.; Han, X. Quantifying Human Experience in Architectural Spaces with Integrated Virtual Reality and Body Sensor Networks. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiato, G.; Jelic, A.; Tieri, G.; Maglione, A.G.; De Matteis, F.; Babiloni, F. Neurophysiological correlates of embodiment and motivational factors during the perception of virtual architectural environments. Cogn Process 2015, 16, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Geng, B.; Tao, X.; Duan, Y.; Gao, D.; Hu, S. Video Quality Measurement For Buffering Time Based On EEG Frequency Feature. in 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 2021, 1424–1428. [CrossRef]

- Geng, B.; et al. A Novel EEG Based Directed Transfer Function for Investigating Human Perception to Audio Noise. in 2020 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, IWCMC 2020, 2020, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonnegra, R.D.; Campáz-Usuga, P.; Osorno-Castillo, K.; Díaz, G.M. Emotion Recognition from Time-Frequency Analysis in EEG Signals Using a Deep Learning Strategy. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 2020; 1154 CCIS, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapakis, I.; Barreda-Angeles, M.; Pereda-Banos, A. Interest as a Proxy of Engagement in News Reading: Spectral and Entropy Analyses of EEG Activity Patterns. IEEE Trans Affect Comput 2019, 10, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheel, A.; Majid, M.; Anwar, S.M. A study on the effects of traditional and olfaction enhanced multimedia on pleasantness classification based on brain activity analysis. Comput Biol Med 2019, 114, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-E.; Jang, S.; Lee, J.-S. Evaluation of preference of multimedia content using deep neural networks for electroencephalography. in 2018 10th International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience, QoMEX 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Deja, J.A.; Cabredo, R. Using EEG emotion models in viewer experience design: An exploratory study. in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2018, 82–88. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhao, G. Natural interaction in video image investigation and its evaluation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2018; 10906 LNAI, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abromavičius, V.; Gedminas, A.; Serackis, A. Detecting sense of presence changes in EEG spectrum during perception of immersive audiovisual content. 2017 Open Conference of Electrical, Electronic and Information Sciences, eStream 2017 - Proceedings of the Conference, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Kubo, V.; Morán, A.L.; Carrillo, I.; Galindo, G.; García-Canseco, E. Assessing the user experience of older adults using a neural network trained to recognize emotions from brain signals. J Biomed Inform 2016, 62, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang; Liu, H. ; Mak, J.N. Detection of media enjoyment using single-channel EEG. in Proceedings - 2016 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference, BioCAS 2016, 2016, 516–519. [CrossRef]

- Samara, A.; Menezes, M.L.R.; Galway, L. Feature Extraction for Emotion Recognition and Modelling Using Neurophysiological Data. in 2016 15th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications and 2016 International Symposium on Cyberspace and Security (IUCC-CSS), 2016, 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Kroupi, E.; Hanhart, P.; Lee, J.-S.; Rerabek, M.; Ebrahimi, T. Modeling immersive media experiences by sensing impact on subjects. Multimed Tools Appl 2016, 75, 12409–12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Falk, T.H. Affective state characterization based on electroencephalography graph-theoretic features. in International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering, NER, 2015, 577–580. [CrossRef]

- Daimi, S.N.; Saha, G. Classification of emotions induced by music videos and correlation with participants’ rating. Expert Syst Appl 2014, 41, 6057–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, U.; De Moor, K. Content categorization based on implicit and explicit user feedback: Combining self-reports with EEG emotional state analysis. in 2012 4th International Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience, QoMEX 2012, 2012, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrantonakis, P.C.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J. Emotion recognition from EEG using higher order crossings. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 2010, 14, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juboori, S.; Mkwawa, I.-H.; Sun, L.; Ifeachor, E. , Modeling the relationships between changes in EEG features and subjective quality of HDR images. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Moon, S.-E.; Lee, J.-S. On the Repeatability of EEG-Based Image Quality Assessment. in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), 2018, 1785–1788. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; et al. Exploring audience response in performing arts with a brain-adaptive digital performance system. ACM Trans Interact Intell Syst, 2017; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Di, K.; Zeng, G.; Wei, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X. Towards better video services: An EEG-based interpretable model for functional quality of experience evaluation. Displays 2024, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, S.; et al. Using Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials and Spatio-Spectral Decomposition. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2018, 28, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acqualagna, L.; et al. EEG-based classification of video quality perception using steady state visual evoked potentials (SSVEPs). J Neural Eng 2015, 12, 26012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Dubey, S.; Ranjan, A.K. , et al. Neural correlates of affective content: application to perceptual tagging of video. Neural Comput Appl 2023, 35, 7925–7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Dubey, S.; Ranjan, A.K. , et al. A deep perceptual framework for affective video tagging through multiband EEG signals modelling. Neural Comput Appl, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Chien, S.Y.; Su, W.C.; Hsiao, S.I. Coding peekaboom: a gaming mechanism for harvesting programming concepts. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Pachori, R.B.; Sanjram, P.K. Dorsal-ventral visual pathways and object characteristics: Beamformer source analysis of EEG. Computers, Materials and Continua 2022, 70, 2347–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jao, P.-K.; Chavarriaga, R.; Dell’agnola, F.; Arza, A.; Atienza, D.; Millán, J.D.R. EEG Correlates of Difficulty Levels in Dynamical Transitions of Simulated Flying and Mapping Tasks. IEEE Trans Hum Mach Syst 2021, 51, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, T.; Saeed, S.M.U.; Arsalan, A.; Anwar, S.M.; Ashraf, M.U.; Alsubhi, K. EEG in game user analysis: A framework for expertise classification during gameplay. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranthaman, P.K.; Bajaj, N.; Solovey, N.; Jennings, D. Comparative Evaluation of the EEG Performance Metrics and Player Ratings on the Virtual Reality Games. in IEEE Conference on Computatonal Intelligence and Games, CIG, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liang, H.N.H.-N.; Zhang, Z.; Baghaei, N. Studying the Effect of Display Type and Viewing Perspective on User Experience in Virtual Reality Exergames. Games Health J 2020, 9, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, S.; Araujo, N.; Guzman, C.; Rusu, C.; Albiol-Pérez, S. Low-cost assessment of user experience through EEG signals. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 158475–158487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.N.; Sharma, K.; Niforatos, E. Exploring EEG signals during the different phases of game-player interaction. in 2019 11th International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications, VS-Games 2019 - Proceedings, 2019, p. 1DUUMY. [CrossRef]

- Labonte-Lemoyne, E.; Courtemanche, F.; Louis, V.; Fredette, M.; Sénécal, S.; Léger, P.-M. Dynamic threshold selection for a biocybernetic loop in an adaptive video game context. Front Hum Neurosci 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumbouya, R.; Benlamine, M.S.; Dufresne, A.; Frasson, C. Game scenes evaluation and player’s dominant emotion prediction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2018; 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Dong, H.; Yang, Y. Developing a Virtual Reality Game User Experience Test Method Based on EEG Signals. in Proceedings - 2017 5th International Conference on Enterprise Systems: Industrial Digitalization by Enterprise Systems, ES 2017, 2017, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, R.; Bellotti, F.; De Gloria, A.; Pranantha, D.; Schatten, C. Electroencephalogram and physiological signal analysis for assessing flow in games. IEEE Trans Comput Intell AI Games 2013, 5, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikov, A.; et al. Exploiting real-time EEG analysis for assessing flow in games. in Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, ICALT 2012, 2012, 688–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, J.; Reinecke, K.; Cordes, M.; Lerch, C.; Weiß, M. Brain activity in goal-directed movements in a real compared to a virtual environment using the Nintendo Wii. Neurosci Lett 2010, 481, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, R.B.; Filiz, E. Enhancement of Player Experience in Video Games Using EEG Based Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment. 16th International Conference on INnovations in Intelligent SysTems and Applications, INISTA 2022, 2022, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Chien, S.Y.; Su, W.C.; Hsiao, S.I. Coding peekaboom: a gaming mechanism for harvesting programming concepts. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr) 2023, 28, 3765–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, R. ; Dasgupta, “Neural correlates of action video game experience in a visuospatial working memory task. Neural Comput Appl 2020, 32, 3431–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Ding, T.; Chen, X.; Shi, F. Using event-related potentials to identify user’s moods induced by product color stimuli with different attributes. Displays 2022, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yuan, F.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Kaner, J. The Impact of Interface Design Element Features on Task Performance in Older Adults: Evidence from Eye-Tracking and EEG Signals. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, N. Research on EEG-based graphic user interface kansei design evaluation. in E3S Web of Conferences, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Cao, Y.; Qu, Q.; Duffy, V.G. An Exploratory Study Using Electroencephalography (EEG) to Measure the Smartphone User Experience in the Short Term. Int J Hum Comput Interact 2020, 36, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.Z.; Kavakli, M. Classification of user competency levels using EEG and convolutional neural network in 3D modelling application. Expert Syst Appl 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangion, R.S.; Garg, L.; Garg, G.; Falzon, O. Emotional Testing on Facebook’s User Experience. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 58250–58259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Camp, M.; De Boeck, M.; Verwulgen, S.; De Bruyne, G. EEG technology for UX evaluation: A multisensory perspective. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 2019, 775, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, S.-P.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, L. Gamma EEG Correlates of Haptic Preferences for a Dial Interface. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 22324–22331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Molina, A.; Retamal, C.; Lira, H. Using psychophysiological sensors to assess mental workload during web browsing. Sensors (Switzerland) 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J.; Niu, Y.F.; Ding, F.Q.; Xue, C.Q. Application of electroencephalogram physiological experiment in interface design teaching: A case study of visual cognitive errors. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri 2018, 18, 2306–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksander, B.A.I.; Fuglerud, K.S. Method for semi-automated evaluation of user experience using brain activity. Stud Health Technol Inform 2018, 256, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefancova, E.; Moro, R.; Bielikova, M. Towards detection of usability issues by measuring emotions. Communications in Computer and Information Science 2018, 909, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ritchie, J.M.; Lim, T.; Kosmadoudi, Z.; Sivanathan, A.; Sung, R.C.W. A fuzzy psycho-physiological approach to enable the understanding of an engineer’s affect status during CAD activities. CAD Computer Aided Design 2014, 54, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Yoon, M.-Y. The Use of EEG to Measure Emotional Response to Tactile Sensation in Evaluation of DSLR Camera Usability. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 2014; 434 PART I, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Li, L.; Ma, L. Online Service Quality Measurement Utilizing Psychophysiological Responses. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 2020, 965, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pireva, K.; Tahir, R.; Imran, A.S.; Chaudhary, N. Evaluating learners’ emotional states by monitoring brain waves for comparing game-based learning approach to pen-and-paper. in Proceedings - Frontiers in Education Conference, FIE, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.N.; Sharma, K.; Pappas, I.O.; Kostakos, V.; Velloso, E. Multimodal data as a means to understand the learning experience. Int J Inf Manage 2019, 48, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, M.; Mitsukura, Y. Portable drowsiness detection through use of a prefrontal single-channel electroencephalogram. Sensors (Switzerland) 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, V.; Wai, A.A.P.; Ho, C.Y. Evaluation of learning performance by quantifying user’s engagement investigation through low-cost multi-modal sensors. in 2017 International Conference on Orange Technologies (ICOT), 2017, 180–183. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Grigore, O.; Guimarães, N.; Duarte, L. Relevance of EEG input signals in the augmented human reader. in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Chen, Y.; Fazli, S.; Wallraven, C. Predicting what you remember from brain activity: EEG-based decoding of long-term memory formation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2018; 10727 LNCS, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.K.; S. A.L.; Megalingam, “Human attention detection system using deep learning and brain–computer interface. Neural Comput Appl 2024, 36, 10927–10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, D.; Zwoliński, G.; Laska-Leśniewicz, A. Usability Testing of Virtual Reality Applications—The Pilot Study. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athif, M.; et al. Using Biosignals for Objective Measurement of Presence in Virtual Reality Environments. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS, 3035–3039. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Chatburn, A.; Billinghurst, M. Exploration of an EEG-Based Cognitively Adaptive Training System in Virtual Reality. in 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Mar. 2019, 220–226. [CrossRef]

- Fabroyir, H.; Teng, W.C. Navigation in virtual environments using head-mounted displays: Allocentric vs. egocentric behaviors. Comput Human Behav 2018, 80, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupi, E.; Yazdani, A.; Vesin, J.-M.; Ebrahimi, T. EEG correlates of pleasant and unpleasant odor perception. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications, 2014; 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.; Delechelle, E. On the measurement of image quality perception using frontal EEG analysis. in 2013 International Conference on Smart Communications in Network Technologies, SaCoNeT 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kober, S.E.; Kurzmann, J.; Neuper, C. Cortical correlate of spatial presence in 2D and 3D interactive virtual reality: An EEG study. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2012, 83, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; et al. Investigate the Neuro Mechanisms of Stereoscopic Visual Fatigue. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Huang, M.; Yang, R.; Han, J.; Yue, Y. Mental Workload Evaluation of Virtual Object Manipulation on WebVR: An EEG Study. in 2021 14th International Conference on Human System Interaction (HSI), 2021, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kosmyna, N.; Maes, P. AttentivU: A Biofeedback Device to Monitor and Improve Engagement in the Workplace. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS, Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 1702–1708., Jul. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijović, P.; et al. Communicating the user state: Introducing cognition-aware computing in industrial settings. Saf Sci 2019, 119, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A.-F.N.M.; Xu, H.; Kroupi, E.; Řeřábek, M. Multimodal Dataset for Assessment of Quality of Experience in Immersive Multimedia. In in In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM international conference on Multimedia (MM ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1007–1010. [Online]. Available:; 2015; pp. 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhong, S.; Liu, Y. GANSER : A Self-supervised Data Augmentation Framework for EEG-based Emotion Recognition”.

- Shen, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, D.; Song, S. Contrastive Learning of Subject-Invariant EEG Representations for Cross-Subject Emotion Recognition. 1–23.

- T. Q.; Zhang, Q.Z.Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition With Emotion Localization via Hierarchical Self-Attention. IEEE Trans Affect Comput 2023, 14, 2458–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juboori, S.; Mkwawa, I.H.; Sun, L.; Ifeachor, E. Investigation of relationships between changes in EEG features and subjective quality of HDR images. Proc (IEEE Int Conf Multimed Expo), 2017; 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cuevas, B.Y.; Crawford, C.S. A Literature Review of Physiological-Based Mobile Educational Systems. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 2021, 14, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marochko, V.; Reilly, R.; McDonnell, R.; Longo, L. A Survey on the Application of Virtual Reality in Event-Related Potential Research. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2022; 13480 LNCS, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.P.; González-González, C.S.; Adamatti, D.F. Business simulation games analysis supported by human-computer interfaces: A systematic review. Sensors, 2021; 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres P, E.P.; Torres, E.A.; Hernández-Álvarez, M.; Yoo, S.G. EEG-based BCI emotion recognition: A survey. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Hammad, A.; Ali, A.A. , Human emotion recognition from EEG-based brain–computer interface using machine learning: a comprehensive review 34, no. 15. Springer London, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Application Field | References |

|---|---|

| Architecture | [11,12,13,14,15] |

| Audiovisual / Media | [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] |

| Games | [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| Interface-Product Design | [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] |

| Learning | [73,74,75,76,77,78,79] |

| Virtual Reality | [14,51,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] |

| Workplace | [89,90] |

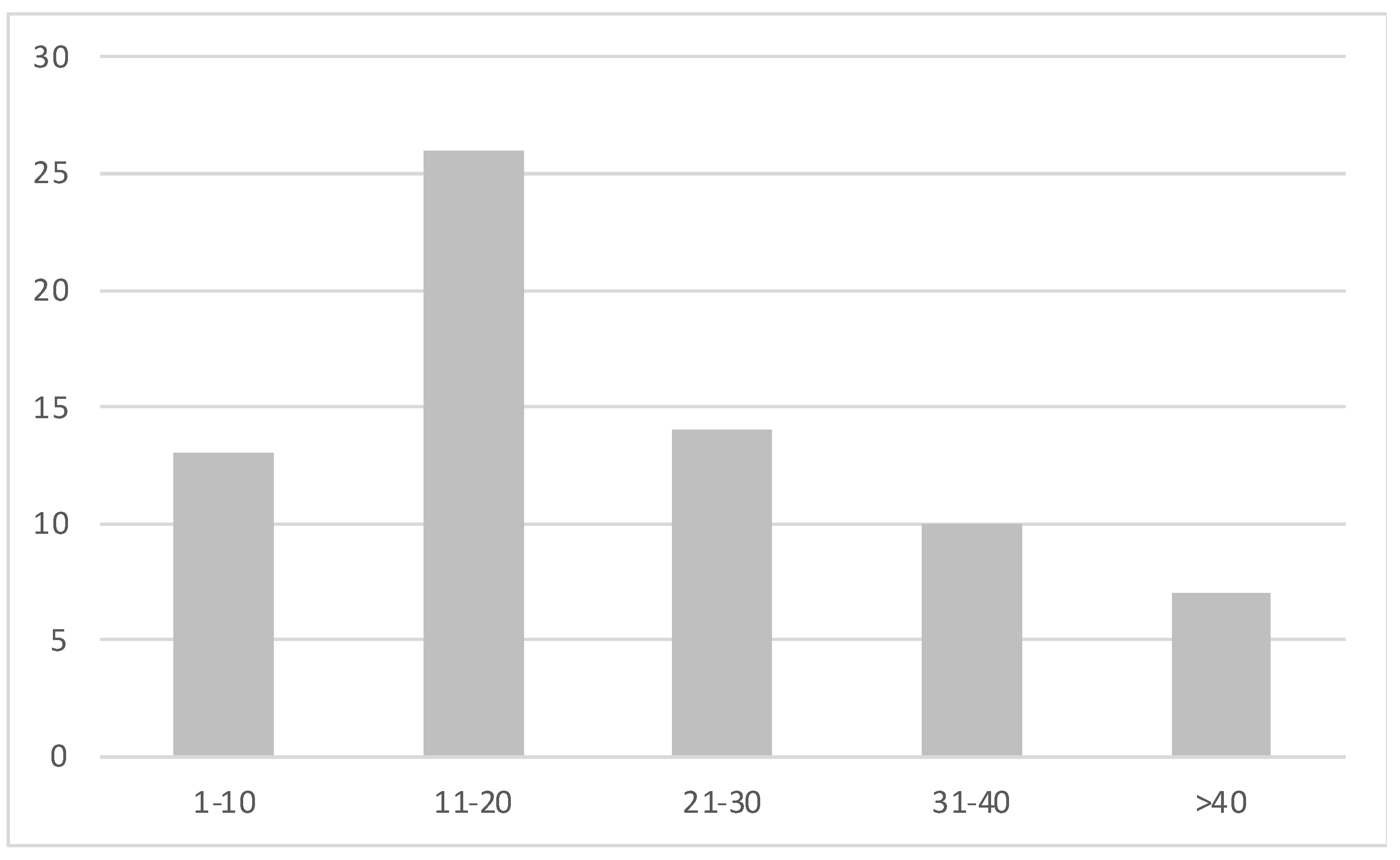

| No. of Participants | References |

|---|---|

| 1-10 | [16,26,34,44,47,53,54,64,68,76,78,84,88] |

| 11-20 | [15,17,20,24,28,32,45,48,49,59,60,62,63,65,67,71,72,74,78,80,81,82,85,87,89,90] |

| 21-30 | [23,25,31,33,43,51,52,58,61,69,70,73,75,86] |

| 31-40 | [13,14,18,21,22,27,29,30,46,83] |

| >40 | [11,12,19,35,41,42,66] |

| Device | EEG Channels | References |

|---|---|---|

| BEmicro, Ebneuro | 24 | [15] |

| BIOPAC MP 150 | 6 | [71] |

| Biosemi | 32 / 64 | [29,34,43,65] |

| BrainAmps | 32 / 64 | [16,17,49,78] |

| BrainCo Focus | 1 | [89] |

| Emotiv | 16 | [51,55] |

| Emotiv EPOC+ | 14 | [19,25,31,35,42,44,45,62,66,69,88] |

| Emotiv Insight | 5 | [22,73] |

| SMARTING (mBrainTrain) | 24 | [90] |

| EEGO | 24 | [67] |

| EGI’s Geodesic EEG System (GES) 300 | 256 | [28,84] |

| ElectroCap Inc. | 19 | [54] |

| Elemaya Visual Energy Tester | 4 | [52,53] |

| ENOBIO | 20 | [48,74] |

| g.GAMMAcap2 | 32 | [81] |

| HeadCoach™, Alpha-Active Ltd | 2 | [33] |

| Liveamp EEG cap | 32 | [82] |

| Looxid Link Package for VIVE Pro | 6 | [80] |

| MindSet-1000 | 16 | [77] |

| MindWave Mobile | 1 | [26,75,85] |

| Muse | 4 | [68,76] |

| NeurOne Bittium | 32 | [58] |

| Neuroscan | 32 / 64 | [23,60,61] |

| NeXus-32 Mindmedia | 24 | [70] |

| OPENBCI | 8 | [47] |

| QUASAR EEG headset | 21 | [64] |

| Method | References |

|---|---|

| Time-domain methods | [21,23,55,58,67,74,78,87,90] |

| Frequency-domain methods - PSD | [15,16,18,19,47,52,61,63,65,75,77,84,89,90] |

| Frequency-domain methods - FFT | [12,13,14,25,35,44,47,51,52,54,61,70,86,90] |

| Frequency-domain methods – Other | [20,22,34,44,45,57,60,69,74] |

| Time-frequency-domain methods | [18,26,30,51,58,65,66,82,88] |

| Spatial-feature based methods | [23,43,62] |

| Method | References |

|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis - ANOVA | [16,19,23,24,28,31,33,35,43,46,48,51,53,54,58,59,65,67,71,77,78,86,87,89] |

| Statistical Analysis – other tests | [11,13,14,15,21,29,33,41,43,45,49,50,61,63,65,69,73,82,83,88,90] |

| Machine Learning | [12,17,18,20,21,22,25,26,27,30,32,34,44,52,53,55,62,68,70,71,74,75,76,77,80,84,90] |

| Graph theory | [29] |

| Study | Review Study | Year Range | Articles Included | Main Objective | Sub-Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our Study | Systematic | 2012-2023 | 74 | explores the intersection of user engagement and user experience studies with EEG | General population Analysis of EEG |

| [96] | Literature | 2014-2019 | 30 | m-learning applications and relation to educational engagement with EEG analysis | physiological-based mobile computing |

| [97] | Survey | 2014-2022 | 39 | Analysing virtual reality experience with EEG headsets | Virtual reality event-related potentials Head-Mounted Displays |

| [98] | Systematic | 2010-2021 | 19 | Studying the learning process and user experience with serious games and EEG | Serious games Eye tracking signals skills and competencies |

| [99] | Survey | 2015-2020 | 31 | Studying the algorithms and processes of EEG based BCI emotion recognition systems | Emotion elicitation signal acquisition feature extraction, selection and classification performance evaluation |

| [100] | Comprehensive | 2015-2021 | 82 | Reviews emotion recognition methods | provides an overview of the datasets and methods used to elicit emotional states (feature extraction, feature selection/reduction, machine learning and deep learning methods) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).