Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

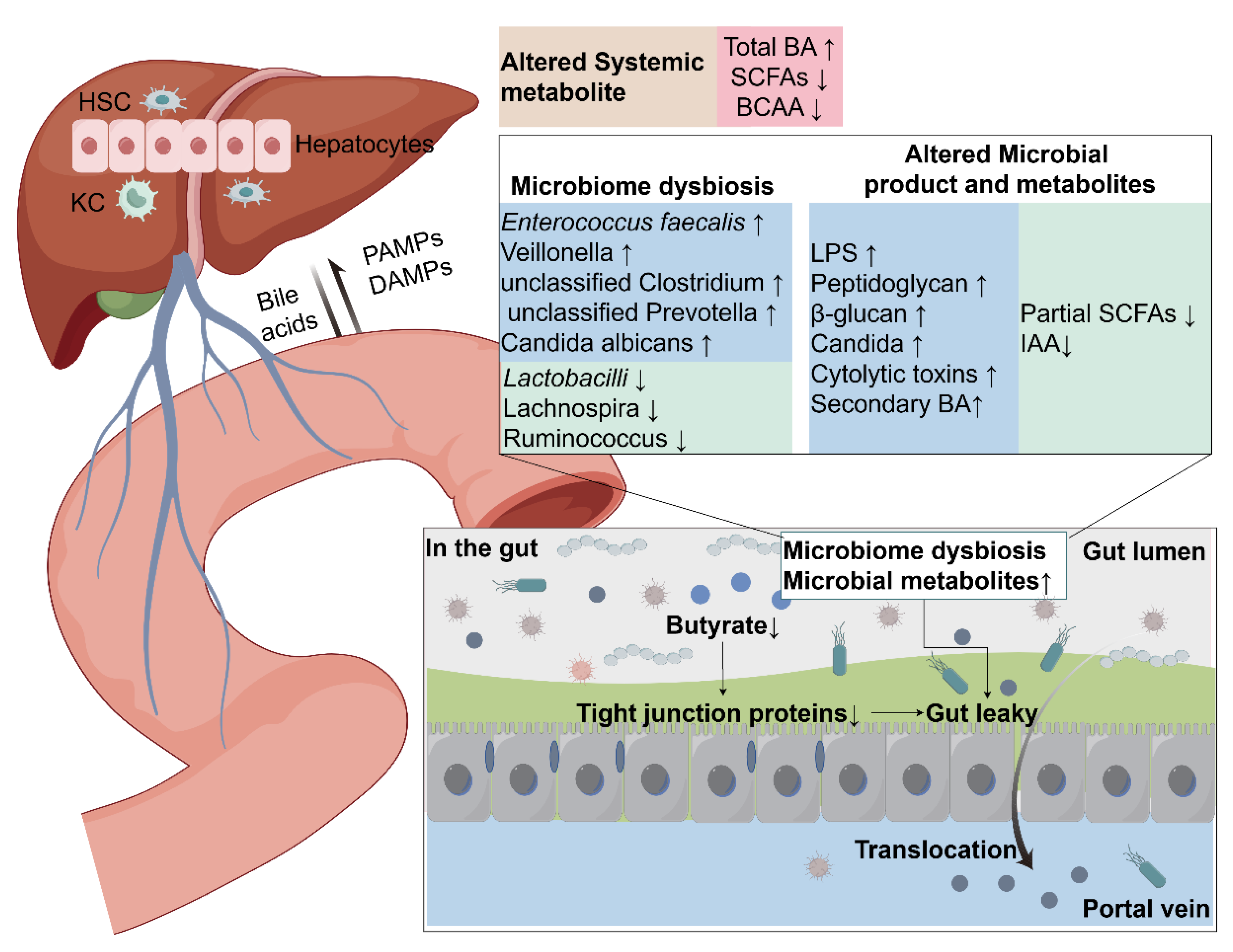

Figure 1. Mechanism of alcohol-related liver disease damage caused by gut microbiota. Drinking alcohol can lead to intestinal microbiota imbalance and increased intestinal permeability. A large number of immunogenic substances enter the circulatory system and reach the liver, activating PRRs receptors on various cells in the liver, triggering the release of a large number of cytokines and chemokines. These substances accumulate in the liver, leading to changes in liver metabolism, inflammation, fibrosis and cirrhosis, and even the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; PRRs, pattern recognition receptors; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Gut-Liver Axis

Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in ALD

The Possible Mechanisms that Gut Microbiota Promote the Development of ALD

Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Barrier

Gut Microbiota and Immunity

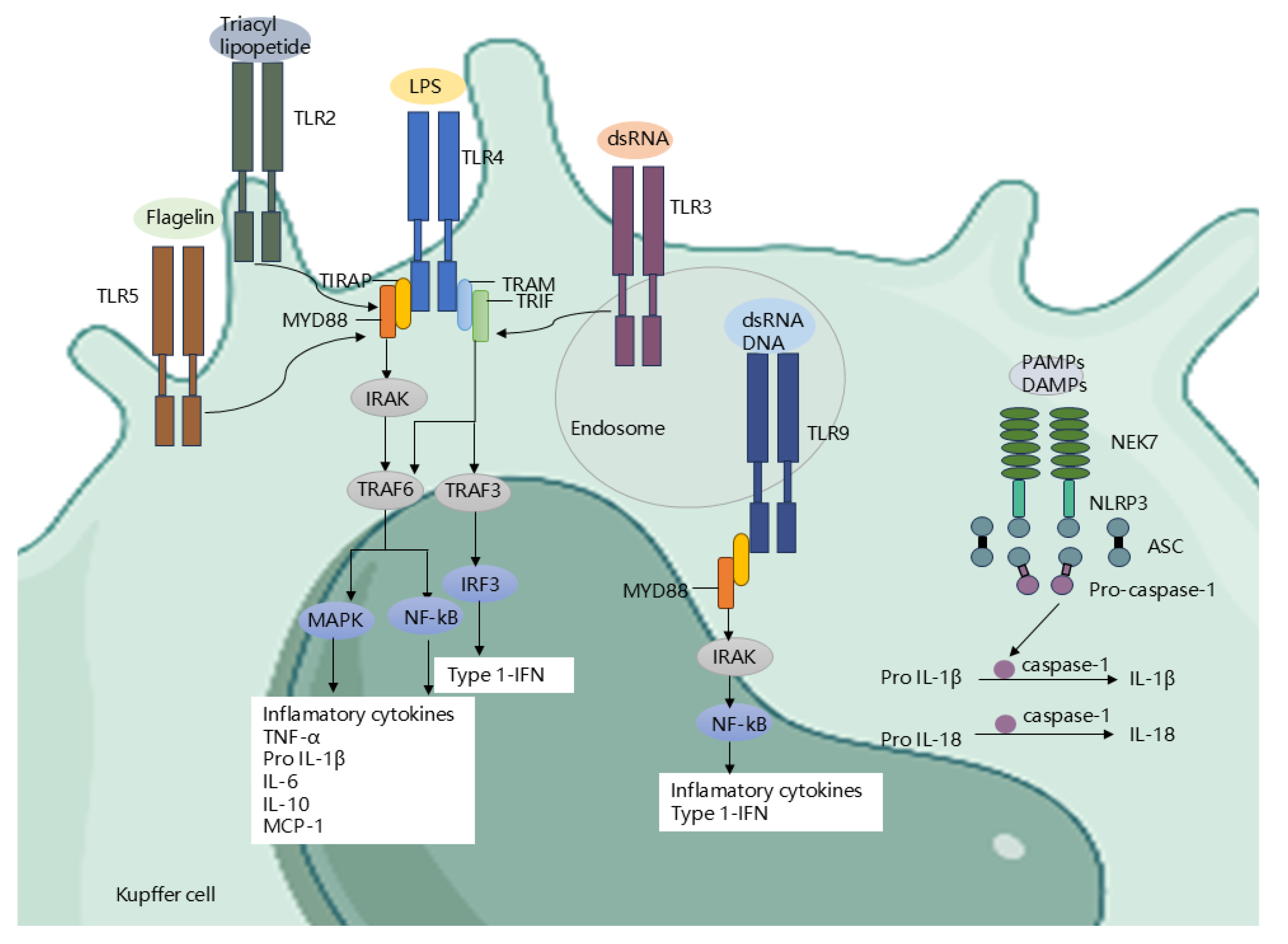

Gut Microbiota Regulate Receptors and Signaling Pathways

Gut Microbiota Regulate Metabolites

Bile Acids

Short-Chain Fatty Acid

Amino Acids

Other Metabolites

Therapy Methods for ALD Target Gut Microbiota

Probiotics

FMT

Bacteriophage

| Participants | Comparison | Change of gut microbiota | Method | Ref | |

| Increased | Decreased | ||||

| Patients |

ALD (n=21) Vs HC(n=16) |

- | Akkermansia muciniphila | 16S rRNA | Grander C, Adolph TE, Wieser V, et al. (2018) [52] |

| Patients |

ALD (n= 14) Vs HC (n=14) |

Alcaligenaceae, Rikenellaceae, Barnesillaceae, Paraprevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, |

Verrucomicrobiaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, Akkermansia, Blautia, Bifidobacterium, Coprococcus Ruminococcus |

16S rRNA | Addolorato G et al.(2020) [44] |

| Patients |

ALD(n=19) Vs HC(n=18) |

Clostridium |

Bacteroides Bifidobacterium |

16S rRNA | Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, et al. (2012) [18] |

| Patients |

AH(n=70) Vs HC (n=88) |

Enterococcus Escherichia coli |

- | 16S rRNA | Duan Y, Llorente C, Lang S, et al. (2019) [54] |

| Patients | AUD(n=10) Vs HC (n=15) |

Lachnospiraceae Blautia |

Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Subdoligranulum, Oscillibacter Anaerofilum |

16S rRNA | Leclecrq S, Matamoros S etal.(2014) [32] |

| Patients | AH (n=18) Vs SAH (n=54) |

Unclassified Clostridales, unclassified Prevotellaceae, Anaerostipes | Akkermansia | 16S rRNA sequencing | Lang s,Fairfied B et al.(2020) [47] |

| Patients | ALD (n=56) Vs HC(n=20) |

Neisseriaceae, Chitinophagaceae, Bradyrhizobiaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae Turicellaand Microbacterium Anaerococcus, Lachnospiraceaeincertaesedis, ClostridiumXI |

- | 16S rRNA sequencing | Puri et al(2018) [48] |

| Patients | ALD(n=27) Vs HC(n=72) |

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Lactobacillus salivarius, Citrobacter koseri, Lactococcus lactis | Akkermansia, Coprococcus, unclassified Clostridiales, | 16S rRNA sequencing | Dubinkina V et al.(2017) [19] |

| Patients |

AH(n=34) Vs HC (n=24) |

Veillonellaceae, Proteobacteria |

Lachnospiraceae,Ruminococcaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, Rikenellaceae |

16S rRNA sequencing | Smirnova E et al (2020) [45] |

| Patients | ALD(n=89) Vs HC(n=40) |

Escherichia coli, Bacteroides spp, Enterococcus spp | - | 16S rRNA sequencing | Casafont M et al (1995) [227] |

| C57BL/6N Mouse model | ALD (n=8) Vs HC (n=8) |

Clostridium perfringens |

Lactobacillus Bifidobacterium |

16S rRNA sequencing | Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, et al. (2013) [50] |

| Mouse model |

ALD (n=12) Vs HC(n=12) |

Bacteroides verrucous microorganisms |

- | 16S rRNA sequencing | Yan A et al.(2011) [49] |

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wu X, Fan X, Miyata T, Kim A, Cajigas-Du Ross C K, Ray S, Huang E, Taiwo M, Arya R, Wu J, Nagy L E. Recent Advances in Understanding of Pathogenesis of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease[J/OL]. Annual Review of Pathology, 2023, 18: 411-438. [CrossRef]

- Seitz H K, Bataller R, Cortez-Pinto H, Gao B, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Mueller S, Szabo G, Tsukamoto H. Alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 2018, 4(1): 16. [CrossRef]

- Thursz M, Kamath P S, Mathurin P, Szabo G, Shah V H. Alcohol-related liver disease: Areas of consensus, unmet needs and opportunities for further study[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2019, 70(3): 521-530. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Qin S, Tan C, Li S, Xie O, Wan X. Estimated projection of incidence and mortality of alcohol-related liver disease in China from 2022 to 2040: a modeling study[J/OL]. BMC Medicine, 2023, 21(1): 277. [CrossRef]

- Sarin S K, Kumar M, Eslam M, George J, Mahtab M A, Akbar S M F, Jia J, Tian Q, Aggarwal R, Muljono D H, Omata M, Ooka Y, Han K H, Lee H W, Jafri W, Butt A S, Chong C H, Lim S G, Pwu R F, Chen D S. Liver diseases in the Asia-Pacific region: a Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commission[J/OL]. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2020, 5(2): 167-228. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018[M/OL]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/274603.

- Kulkarni N S, Wadhwa D K, Kanwal F, Chhatwal J. Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease Mortality Rates by Race Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US[J/OL]. JAMA Health Forum, 2023, 4(4): e230527. [CrossRef]

- Hsu C L, Schnabl B. The gut–liver axis and gut microbiota in health and liver disease[J/OL]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2023, 21(11): 719-733. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S. Alcohol, liver disease and the gut microbiota[J/OL]. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2019, 16(4): 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Adawi D, Kasravi F B, Molin G, Jeppsson B. Effect ofLactobacillus supplementation with and without arginine on liver damage and bacterial translocation in an acute liver injury model in the rat[J/OL]. Hepatology, 1997, 25(3): 642-647. [CrossRef]

- Nanji A A, Khettry U, Sadrzadeh S M. Lactobacillus feeding reduces endotoxemia and severity of experimental alcoholic liver (disease)[J/OL]. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.), 1994, 205(3): 243-247. [CrossRef]

- Belizário J E, Napolitano M. Human microbiomes and their roles in dysbiosis, common diseases, and novel therapeutic approaches[J/OL]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso N, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani F R. Intestinal Barrier in Human Health and Disease[J/OL]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(23): 12836. [CrossRef]

- Kirpich I A, Solovieva N V, Leikhter S N, Shidakova N A, Lebedeva O V, Sidorov P I, Bazhukova T A, Soloviev A G, Barve S S, McClain C J, Cave M. Probiotics restore bowel flora and improve liver enzymes in human alcohol-induced liver injury: a pilot study[J/OL]. Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.), 2008, 42(8): 675-682. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann P, Chen W C, Schnabl B. The intestinal microbiome and the leaky gut as therapeutic targets in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2012, 3: 402. [CrossRef]

- Sarin S K, Pande A, Schnabl B. Microbiome as a therapeutic target in alcohol-related liver disease[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2019, 70(2): 260-272. [CrossRef]

- Eom J A, Jeong J J, Han S H, Kwon G H, Lee K J, Gupta H, Sharma S P, Won S M, Oh K K, Yoon S J, Joung H C, Kim K H, Kim D J, Suk K T. Gut-microbiota prompt activation of natural killer cell on alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Gut Microbes, 2023, 15(2): 2281014. [CrossRef]

- Mutlu E A, Gillevet P M, Rangwala H, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Engen P A, Kwasny M, Lau C K, Keshavarzian A. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism[J/OL]. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2012, 302(9): G966-G978. [CrossRef]

- Dubinkina V B, Tyakht A V, Odintsova V Y, Yarygin K S, Kovarsky B A, Pavlenko A V, Ischenko D S, Popenko A S, Alexeev D G, Taraskina A Y, Nasyrova R F, Krupitsky E M, Shalikiani N V, Bakulin I G, Shcherbakov P L, Skorodumova L O, Larin A K, Kostryukova E S, Abdulkhakov R A, Abdulkhakov S R, Malanin S Y, Ismagilova R K, Grigoryeva T V, Ilina E N, Govorun V M. Links of gut microbiota composition with alcohol dependence syndrome and alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Microbiome, 2017, 5(1): 141. [CrossRef]

- Ferrere G, Wrzosek L, Cailleux F, Turpin W, Puchois V, Spatz M, Ciocan D, Rainteau D, Humbert L, Hugot C, Gaudin F, Noordine M L, Robert V, Berrebi D, Thomas M, Naveau S, Perlemuter G, Cassard A M. Fecal microbiota manipulation prevents dysbiosis and alcohol-induced liver injury in mice[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2017, 66(4): 806-815. [CrossRef]

- Llopis M, Cassard A M, Wrzosek L, Boschat L, Bruneau A, Ferrere G, Puchois V, Martin J C, Lepage P, Le Roy T, Lefèvre L, Langelier B, Cailleux F, González-Castro A M, Rabot S, Gaudin F, Agostini H, Prévot S, Berrebi D, Ciocan D, Jousse C, Naveau S, Gérard P, Perlemuter G. Intestinal microbiota contributes to individual susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Gut, 2016, 65(5): 830-839. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S, Kakiyama G, Zhao D, Takei H, Fagan A, Hylemon P, Zhou H, Pandak W M, Nittono H, Fiehn O, Salzman N, Holtz M, Simpson P, Gavis E A, Heuman D M, Liu R, Kang D J, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P M. Continued Alcohol Misuse in Human Cirrhosis is Associated with an Impaired Gut-Liver Axis[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2017, 41(11): 1857-1865. [CrossRef]

- Szabo G. Gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 148(1): 30-36. [CrossRef]

- Peterson L W, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis[J/OL]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2014, 14(3): 141-153. [CrossRef]

- Turner J R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease[J/OL]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2009, 9(11): 799-809. [CrossRef]

- Chelakkot C, Ghim J, Ryu S H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications[J/OL]. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 2018, 50(8): 103. [CrossRef]

- Tilg H, Adolph T E, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: Pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications[J/OL]. Cell Metabolism, 2022, 34(11): 1700-1718. [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto S, Pessi T, Collin P, Vuento R, Aittoniemi J, Karhunen P J. Changes in gut bacterial populations and their translocation into liver and ascites in alcoholic liver cirrhotics[J/OL]. BMC gastroenterology, 2014, 14: 40. [CrossRef]

- An L, Wirth U, Koch D, Schirren M, Drefs M, Koliogiannis D, Nieß H, Andrassy J, Guba M, Bazhin A V, Werner J, Kühn F. The Role of Gut-Derived Lipopolysaccharides and the Intestinal Barrier in Fatty Liver Diseases[J/OL]. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery: Official Journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 2022, 26(3): 671-683. [CrossRef]

- Lang S, Schnabl B. Microbiota and Fatty Liver Disease-the Known, the Unknown, and the Future[J/OL]. Cell Host & Microbe, 2020, 28(2): 233-244. [CrossRef]

- Cook R T. Alcohol abuse, alcoholism, and damage to the immune system--a review[J]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 1998, 22(9): 1927-1942.

- Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani P D, Neyrinck A M, Jamar F, Stärkel P, Windey K, Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F, Verbeke K, de Timary P, Delzenne N M. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity[J/OL]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(42): E4485-E4493. [CrossRef]

- Dukić M, Radonjić T, Jovanović I, Zdravković M, Todorović Z, Kraišnik N, Aranđelović B, Mandić O, Popadić V, Nikolić N, Klašnja S, Manojlović A, Divac A, Gačić J, Brajković M, Oprić S, Popović M, Branković M. Alcohol, Inflammation, and Microbiota in Alcoholic Liver Disease[J/OL]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(4): 3735. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida T, Friedman S L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation[J/OL]. Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2017, 14(7): 397-411. [CrossRef]

- Ohtani N, Kawada N. Role of the Gut-Liver Axis in Liver Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Cancer: A Special Focus on the Gut Microbiota Relationship[J/OL]. Hepatology Communications, 2019, 3(4): 456-470. [CrossRef]

- Consortium T H M P. Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome[J/OL]. Nature, 2012, 486(7402): 207. [CrossRef]

- Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf K S, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende D R, Li J, Xu J, Li S, Li D, Cao J, Wang B, Liang H, Zheng H, Xie Y, Tap J, Lepage P, Bertalan M, Batto J M, Hansen T, Le Paslier D, Linneberg A, Nielsen H B, Pelletier E, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Turner K, Zhu H, Yu C, Li S, Jian M, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Li S, Qin N, Yang H, Wang J, Brunak S, Doré J, Guarner F, Kristiansen K, Pedersen O, Parkhill J, Weissenbach J, Bork P, Ehrlich S D, Wang J. A human gut microbial gene catalog established by metagenomic sequencing[J/OL]. Nature, 2010, 464(7285): 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Kuziel G A, Rakoff-Nahoum S. The gut microbiome[J/OL]. Current biology: CB, 2022, 32(6): R257-R264. [CrossRef]

- Guarner F, Malagelada J R. Gut flora in health and disease[J/OL]. The Lancet, 2003, 361(9356): 512-519. [CrossRef]

- Lopetuso L R, Scaldaferri F, Petito V, Gasbarrini A. Commensal Clostridia: leading players in the maintenance of gut homeostasis[J/OL]. Gut Pathogens, 2013, 5(1): 23. [CrossRef]

- Clemente J C, Ursell L K, Parfrey L W, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view[J/OL]. Cell, 2012, 148(6): 1258-1270. [CrossRef]

- Brown C T, Sharon I, Thomas B C, Castelle C J, Morowitz M J, Banfield J F. Genome resolved analysis of a premature infant gut microbial community reveals a Varibaculum cambriense genome and a shift towards fermentation-based metabolism during the third week of life[J/OL]. Microbiome, 2013, 1(1): 30. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo G, Mirijello A, Ferrulli A, Antonelli M, Landolfi R, Gasbarrini A, Addolorato G. Review article: Alcohol and gut microbiota - the possible role of gut microbiota modulation in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2015, 41(10): 917-927. [CrossRef]

- Addolorato G, Ponziani F R, Dionisi T, Mosoni C, Vassallo G A, Sestito L, Petito V, Picca A, Marzetti E, Tarli C, Mirijello A, Zocco M A, Lopetuso L R, Antonelli M, Rando M M, Paroni Sterbini F, Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Gasbarrini A. Gut microbiota compositional and functional fingerprint in patients with alcohol use disorder and alcohol-associated liver disease[J/OL]. Liver International: Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver, 2020, 40(4): 878-888. [CrossRef]

- Smirnova E, Puri P, Muthiah M D, Daitya K, Brown R, Chalasani N, Liangpunsakul S, Shah V H, Gelow K, Siddiqui M S, Boyett S, Mirshahi F, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P, Sanyal A J. Fecal Microbiome Distinguishes Alcohol Consumption From Alcoholic Hepatitis But Does Not Discriminate Disease Severity[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2020, 72(1): 271-286. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S, Heuman D M, Hylemon P B, Sanyal A J, White M B, Monteith P, Noble N A, Unser A B, Daita K, Fisher A R, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P M. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2014, 60(5): 940-947. [CrossRef]

- Lang S, Fairfied B, Gao B, Duan Y, Zhang X, Fouts D E, Schnabl B. Changes in the fecal bacterial microbiota associated with disease severity in alcoholic hepatitis patients[J/OL]. Gut Microbes, 12(1): 1785251. [CrossRef]

- Puri P, Liangpunsakul S, Christensen J E, Shah V H, Kamath P S, Gores G J, Walker S, Comerford M, Katz B, Borst A, Yu Q, Kumar D P, Mirshahi F, Radaeva S, Chalasani N P, Crabb D W, Sanyal A J, TREAT Consortium. The circulating microbiome signature and inferred functional metagenomics in alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2018, 67(4): 1284-1302. [CrossRef]

- Yan A W, Fouts D E, Brandl J, Stärkel P, Torralba M, Schott E, Tsukamoto H, Nelson K E, Brenner D A, Schnabl B. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2011, 53(1): 96-105. [CrossRef]

- Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, Wang Y, Qin X, Liu Y, Gobejishvili L, Joshi-Barve S, Ayvaz T, Petrosino J, Kong M, Barker D, McClain C, Barve S. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment[J/OL]. PloS One, 2013, 8(1): e53028. [CrossRef]

- Llorente C, Jepsen P, Inamine T, Wang L, Bluemel S, Wang H J, Loomba R, Bajaj J S, Schubert M L, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P M, Xu J, Kisseleva T, Ho S B, DePew J, Du X, Sørensen H T, Vilstrup H, Nelson K E, Brenner D A, Fouts D E, Schnabl B. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus[J/OL]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8(1): 837. [CrossRef]

- Grander C, Adolph T E, Wieser V, Lowe P, Wrzosek L, Gyongyosi B, Ward D V, Grabherr F, Gerner R R, Pfister A, Enrich B, Ciocan D, Macheiner S, Mayr L, Drach M, Moser P, Moschen A R, Perlemuter G, Szabo G, Cassard A M, Tilg H. Recovery of ethanol-induced Akkermansia muciniphila depletion ameliorates alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Gut, 2018, 67(5): 891-901. [CrossRef]

- Bode J C, Bode C, Heidelbach R, Dürr H K, Martini G A. Jejunal microflora in patients with chronic alcohol abuse[J]. Hepato-Gastroenterology, 1984, 31(1): 30-34.

- Duan Y, Llorente C, Lang S, Brandl K, Chu H, Jiang L, White R C, Clarke T H, Nguyen K, Torralba M, Shao Y, Liu J, Hernandez-Morales A, Lessor L, Rahman I R, Miyamoto Y, Ly M, Gao B, Sun W, Kiesel R, Hutmacher F, Lee S, Ventura-Cots M, Bosques-Padilla F, Verna E C, Abraldes J G, Brown R S, Vargas V, Altamirano J, Caballería J, Shawcross D L, Ho S B, Louvet A, Lucey M R, Mathurin P, Garcia-Tsao G, Bataller R, Tu X M, Eckmann L, van der Donk W A, Young R, Lawley T D, Stärkel P, Pride D, Fouts D E, Schnabl B. Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Nature, 2019, 575(7783): 505-511. [CrossRef]

- Naito Y, Uchiyama K, Takagi T. A next-generation beneficial microbe: Akkermansia muciniphila[J/OL]. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition, 2018, 63(1): 33-35. [CrossRef]

- Kakiyama G, Hylemon P B, Zhou H, Pandak W M, Heuman D M, Kang D J, Takei H, Nittono H, Ridlon J M, Fuchs M, Gurley E C, Wang Y, Liu R, Sanyal A J, Gillevet P M, Bajaj J S. Colonic inflammation and secondary bile acids in alcoholic cirrhosis[J/OL]. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2014, 306(11): G929-937. [CrossRef]

- Bode C, Kugler V, Bode J C. Endotoxemia in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis and in subjects with no evidence of chronic liver disease following acute alcohol excess[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 1987, 4(1): 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury S, Glueck B, Han Y, Mohammad M A, Cresci G A M. A Designer Synbiotic Attenuates Chronic-Binge Ethanol-Induced Gut-Liver Injury in Mice[J/OL]. Nutrients, 2019, 11(1): 97. [CrossRef]

- Maccioni L, Gao B, Leclercq S, Pirlot B, Horsmans Y, De Timary P, Leclercq I, Fouts D, Schnabl B, Stärkel P. Intestinal permeability, microbial translocation, changes in duodenal and fecal microbiota, and their associations with alcoholic liver disease progression in humans[J/OL]. Gut Microbes, 2020, 12(1): 1782157. [CrossRef]

- Rs L, Fy L, Sd L, Yt T, Hc L, Rh L, Wc H, Cc H, Ss W, Kj L. Endotoxemia in patients with chronic liver diseases: relationship to severity of liver diseases, presence of esophageal varices, and hyperdynamic circulation[J/OL]. Journal of hepatology, 1995, 22(2). [CrossRef]

- Vancamelbeke M, Vermeire S. The intestinal barrier: a fundamental role in health and disease[J/OL]. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2017, 11(9): 821-834. [CrossRef]

- Chung L K, Raffatellu M. G.I. pros: Antimicrobial defense in the gastrointestinal tract[J/OL]. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2019, 88: 129-137. [CrossRef]

- Ye R, Yj B. Balancing Act of the Intestinal Antimicrobial Proteins on Gut Microbiota and Health[J/OL]. Journal of microbiology (Seoul, Korea), 2024, 62(3). [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx T, Duan Y, Wang Y, Oh J H, Alexander L M, Huang W, Stärkel P, Ho S B, Gao B, Fiehn O, Emond P, Sokol H, van Pijkeren J P, Schnabl B. Bacteria Engineered to Produce IL22 in Intestine Induce Expression of REG3G to Reduce Ethanol-induced Liver Disease in Mice[J/OL]. Gut, 2018: gutjnl-2018-317232. [CrossRef]

- Zhong W, Wei X, Hao L, Lin T D, Yue R, Sun X, Guo W, Dong H, Li T, Ahmadi A R, Sun Z, Zhang Q, Zhao J, Zhou Z. Paneth Cell Dysfunction Mediates Alcohol-related Steatohepatitis Through Promoting Bacterial Translocation in Mice: Role of Zinc Deficiency[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2020, 71(5): 1575-1591. [CrossRef]

- Zhou R, Llorente C, Cao J, Gao B, Duan Y, Jiang L, Wang Y, Kumar V, Stärkel P, Bode L, Fan X, Schnabl B. Deficiency of Intestinal α1-2-Fucosylation Exacerbates Ethanol-Induced Liver Disease in Mice[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2020, 44(9): 1842-1851. [CrossRef]

- Pickard J M, Chervonsky A V. Intestinal fucose as a mediator of host-microbe symbiosis[J/OL]. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 2015, 194(12): 5588-5593. [CrossRef]

- Pham T A N, Clare S, Goulding D, Arasteh J M, Stares M D, Browne H P, Keane J A, Page A J, Kumasaka N, Kane L, Mottram L, Harcourt K, Hale C, Arends M J, Gaffney D J, Sanger Mouse Genetics Project, Dougan G, Lawley T D. Epithelial IL-22RA1-mediated fucosylation promotes intestinal colonization resistance to an opportunistic pathogen[J/OL]. Cell Host & Microbe, 2014, 16(4): 504-516. [CrossRef]

- Smith P M, Howitt M R, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini C A, Bohlooly-Y M, Glickman J N, Garrett W S. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis[J/OL]. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2013, 341(6145): 569-573. [CrossRef]

- Yang W, Yu T, Huang X, Bilotta A J, Xu L, Lu Y, Sun J, Pan F, Zhou J, Zhang W, Yao S, Maynard C L, Singh N, Dann S M, Liu Z, Cong Y. Intestinal microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulation of immune cell IL-22 production and gut immunity[J/OL]. Nature Communications, 2020, 11(1): 4457. [CrossRef]

- Mann E R, Lam Y K, Uhlig H H. Short-chain fatty acids: linking diet, the microbiome and immunity[J/OL]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2024, 24(8): 577-595. [CrossRef]

- Luu M, Riester Z, Baldrich A, Reichardt N, Yuille S, Busetti A, Klein M, Wempe A, Leister H, Raifer H, Picard F, Muhammad K, Ohl K, Romero R, Fischer F, Bauer C A, Huber M, Gress T M, Lauth M, Danhof S, Bopp T, Nerreter T, Mulder I E, Steinhoff U, Hudecek M, Visekruna A. Microbial short-chain fatty acids modulate CD8+ T cell responses and improve adoptive immunotherapy for cancer[J/OL]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12(1): 4077. [CrossRef]

- Gu M, Samuelson D R, Taylor C M, Molina P E, Luo M, Siggins R W, Shellito J E, Welsh D A. Alcohol-associated intestinal dysbiosis alters mucosal-associated invariant T-cell phenotype and function[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2021, 45(5): 934-947. [CrossRef]

- Nm P, P K. MAIT Cells in Health and Disease[J/OL]. Annual review of immunology, 2020, 38. [CrossRef]

- Legoux F, Salou M, Lantz O. MAIT Cell Development and Functions: the Microbial Connection[J/OL]. Immunity, 2020, 53(4): 710-723. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Han F, Ho A, Xue Y, Wu Z, Chen X, Sandberg J K, Ma S, Leeansyah E. Role of MAIT cells in gastrointestinal tract bacterial infections in humans: More than a gut feeling[J/OL]. Mucosal Immunology, 2023, 16(5): 740-752. [CrossRef]

- Germain L, Veloso P, Lantz O, Legoux F. MAIT cells: Conserved watchers on the wall[J/OL]. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2025, 222(1): e20232298. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Mehal W, Nagy L E, Rotman Y. Immunological mechanisms and therapeutic targets of fatty liver diseases[J/OL]. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 2021, 18(1): 73-91. [CrossRef]

- Xu H, Wang H. Immune cells in alcohol-related liver disease[J/OL]. Liver Research, 2022, 6(1): 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kim A, McCullough R L, Poulsen K L, Sanz-Garcia C, Sheehan M, Stavitsky A B, Nagy L E. Hepatic Immune System: Adaptations to Alcohol[J/OL]. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 2018, 248: 347-367. [CrossRef]

- Jeong W I, Gao B. Innate immunity and alcoholic liver fibrosis[J/OL]. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2008, 23 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): S112-118. [CrossRef]

- Piano M R. Alcohol’s Effects on the Cardiovascular System[J]. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 2017, 38(2): 219-241.

- Pone E J. Analysis by Flow Cytometry of B-Cell Activation and Antibody Responses Induced by Toll-Like Receptors[J/OL]. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2016, 1390: 229-248. [CrossRef]

- Paik Y H, Schwabe R F, Bataller R, Russo M P, Jobin C, Brenner D A. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2003, 37(5): 1043-1055. [CrossRef]

- Taïeb J, Delarche C, Paradis V, Mathurin P, Grenier A, Crestani B, Dehoux M, Thabut D, Gougerot-Pocidalo M A, Poynard T, Chollet-Martin S. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils are a source of hepatocyte growth factor in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2002, 36(3): 342-348. [CrossRef]

- Bertola A, Park O, Gao B. Chronic plus binge ethanol feeding synergistically induces neutrophil infiltration and liver injury in mice: a critical role for E-selectin[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2013, 58(5): 1814-1823. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez M, Miquel R, Colmenero J, Moreno M, García-Pagán J C, Bosch J, Arroyo V, Ginès P, Caballería J, Bataller R. Hepatic expression of CXC chemokines predicts portal hypertension and survival in patients with alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 136(5): 1639-1650. [CrossRef]

- Degré D, Lemmers A, Gustot T, Ouziel R, Trépo E, Demetter P, Verset L, Quertinmont E, Vercruysse V, Le Moine O, Devière J, Moreno C. Hepatic expression of CCL2 in alcoholic liver disease is associated with disease severity and neutrophil infiltrates[J/OL]. Clinical and Experimental Immunology, 2012, 169(3): 302-310. [CrossRef]

- Ibusuki R, Uto H, Oda K, Ohshige A, Tabu K, Mawatari S, Kumagai K, Kanmura S, Tamai T, Moriuchi A, Tsubouchi H, Ido A. Human neutrophil peptide-1 promotes alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis and hepatocyte apoptosis[J/OL]. PloS One, 2017, 12(4): e0174913. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, You Q, Lor K, Chen F, Gao B, Ju C. Chronic alcohol ingestion modulates hepatic macrophage populations and functions in mice[J/OL]. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 2014, 96(4): 657-665. [CrossRef]

- Albano E, Vidali M. Immune mechanisms in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Genes & Nutrition, 2010, 5(2): 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Mandrekar P, Ambade A. Immunity and inflammatory signaling in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Hepatology International, 2014, 8 Suppl 2(0 2): 439-446. [CrossRef]

- Shevach E M, Davidson T S, Huter E N, Dipaolo R A, Andersson J. Role of TGF-Beta in the induction of Foxp3 expression and T regulatory cell function[J/OL]. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 2008, 28(6): 640-646. [CrossRef]

- Markwick L J L, Riva A, Ryan J M, Cooksley H, Palma E, Tranah T H, Vijay G K M, Vergis N, Thursz M, Evans A, Wright G, Tarff S, O’Grady J, Williams R, Shawcross D L, Chokshi S. Blockade of PD1 and TIM3 Restores Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Patients With Acute Alcoholic Hepatitis[J/OL]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 148(3): 590-602.e10. [CrossRef]

- Støy S, Dige A, Sandahl T D, Laursen T L, Buus C, Hokland M, Vilstrup H. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells display impaired cytotoxic functions and reduced activation in patients with alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2015, 308(4): G269-276. [CrossRef]

- Pan H na, Sun R, Jaruga B, Hong F, Kim W H, Gao B. Chronic ethanol consumption inhibits hepatic natural killer cell activity and accelerates murine cytomegalovirus-induced hepatitis[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2006, 30(9): 1615-1623. [CrossRef]

- Duddempudi A T. Immunology in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Clinics in Liver Disease, 2012, 16(4): 687-698. [CrossRef]

- Melhem A, Muhanna N, Bishara A, Alvarez C E, Ilan Y, Bishara T, Horani A, Nassar M, Friedman S L, Safadi R. Anti-fibrotic activity of NK cells in experimental liver injury through killing of activated HSC[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2006, 45(1): 60-71. [CrossRef]

- Dhanda A D, Collins P L. Immune dysfunction in acute alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2015, 21(42): 11904-11913. [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli S, Nobili V, Alisi A. Toll-like receptor-mediated signaling cascade as a regulator of the inflammation network during alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG, 2014, 20(44): 16443-16451. [CrossRef]

- Miller Y I, Choi S H, Wiesner P, Fang L, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Boullier A, Gonen A, Diehl C J, Que X, Montano E, Shaw P X, Tsimikas S, Binder C J, Witztum J L. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity[J/OL]. Circulation Research, 2011, 108(2): 235-248. [CrossRef]

- Gao B, Ahmad M F, Nagy L E, Tsukamoto H. Inflammatory pathways in alcoholic steatohepatitis[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2019, 70(2): 249-259. [CrossRef]

- Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity[J/OL]. Nature Immunology, 2001, 2(8): 675-680. [CrossRef]

- Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors[J/OL]. Nature Immunology, 2010, 11(5): 373-384. [CrossRef]

- Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Signalling pathways in alcohol-induced liver inflammation[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2009, 50(6): 1258-1266. [CrossRef]

- Babu S, Blauvelt C P, Kumaraswami V, Nutman T B. Cutting edge: diminished T cell TLR expression and function modulates the immune response in human filarial infection[J/OL]. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 2006, 176(7): 3885-3889. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler M D. Endotoxin and Kupffer cell activation in alcoholic liver disease[J]. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2003, 27(4): 300-306.

- Uesugi T, Froh M, Arteel G E, Bradford B U, Thurman R G. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2001, 34(1): 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Mencin A, Kluwe J, Schwabe R F. Toll-like receptors as targets in chronic liver diseases[J/OL]. Gut, 2009, 58(5): 704-720. [CrossRef]

- Petrasek J, Csak T, Szabo G. Toll-like receptors in liver disease[J/OL]. Advances in Clinical Chemistry, 2013, 59: 155-201. [CrossRef]

- Seki E, Schnabl B. Role of innate immunity and the microbiota in liver fibrosis: crosstalk between the liver and gut[J/OL]. The Journal of Physiology, 2012, 590(3): 447-458. [CrossRef]

- Petrasek J, Dolganiuc A, Csak T, Nath B, Hritz I, Kodys K, Catalano D, Kurt-Jones E, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Interferon regulatory factor 3 and type I interferons are protective in alcoholic liver injury in mice by way of crosstalk of parenchymal and myeloid cells[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2011, 53(2): 649-660. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X J, Dong Q, Bindas J, Piganelli J D, Magill A, Reiser J, Kolls J K. TRIF and IRF-3 binding to the TNF promoter results in macrophage TNF dysregulation and steatosis induced by chronic ethanol[J/OL]. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 2008, 181(5): 3049-3056. [CrossRef]

- Atianand M K, Rathinam V A, Fitzgerald K A. SnapShot: inflammasomes[J/OL]. Cell, 2013, 153(1): 272-272.e1. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Dong L, Lin X, Li J. Relevance of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Liver Disease[J/OL]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2017, 8: 1728. [CrossRef]

- Kono H, Rusyn I, Yin M, Gäbele E, Yamashina S, Dikalova A, Kadiiska M B, Connor H D, Mason R P, Segal B H, Bradford B U, Holland S M, Thurman R G. NADPH oxidase–derived free radicals are key oxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease[J/OL]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2000, 106(7): 867-872. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Goeddel D V. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway[J/OL]. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2002, 296(5573): 1634-1635. [CrossRef]

- Cubero F J, Nieto N. Ethanol and arachidonic acid synergize to activate Kupffer cells and modulate the fibrogenic response via tumor necrosis factor alpha, reduced glutathione, and transforming growth factor beta-dependent mechanisms[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2008, 48(6): 2027-2039. [CrossRef]

- Locksley R M, Killeen N, Lenardo M J. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology[J/OL]. Cell, 2001, 104(4): 487-501. [CrossRef]

- Wilson N S, Dixit V, Ashkenazi A. Death receptor signal transducers: nodes of coordination in immune signaling networks[J/OL]. Nature Immunology, 2009, 10(4): 348-355. [CrossRef]

- Purohit V, Gao B, Song B J. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2009, 33(2): 191-205. [CrossRef]

- Inokuchi S, Tsukamoto H, Park E, Liu Z X, Brenner D A, Seki E. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates alcohol-induced steatohepatitis through bone marrow-derived and endogenous liver cells in mice[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2011, 35(8): 1509-1518. [CrossRef]

- Gao B. Hepatoprotective and anti-inflammatory cytokines in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2012, 27 Suppl 2(Suppl 2): 89-93. [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi N, Wang L, Mukhopadhyay P, Park O, Jeong W I, Lafdil F, Osei-Hyiaman D, Moh A, Fu X Y, Pacher P, Kunos G, Gao B. Cell type-dependent pro- and anti-inflammatory role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in alcoholic liver injury[J/OL]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(4): 1148-1158. [CrossRef]

- García-Calvo X, Bolao F, Sanvisens A, Zuluaga P, Tor J, Muga R, Fuster D. Significance of Markers of Monocyte Activation (CD163 and sCD14) and Inflammation (IL-6) in Patients Admitted for Alcohol Use Disorder Treatment[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 2020, 44(1): 152-158. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Liu N N, Li J R, Wang M X, Tan J L, Dong B, Lan P, Zhao L M, Peng Z G, Jiang J D. Bicyclol ameliorates advanced liver diseases in murine models via inhibiting the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway[J/OL]. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie, 2022, 150: 113083. [CrossRef]

- Kulp A, Kuehn M J. Biological Functions and Biogenesis of Secreted Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles[J/OL]. Annual review of microbiology, 2010, 64: 163-184. [CrossRef]

- Bishop D G, Work E. An extracellular glycolipid produced by Escherichia coli grown under lysine-limiting conditions[J/OL]. The Biochemical Journal, 1965, 96(2): 567-576. [CrossRef]

- Rathinam V A K, Vanaja S K, Waggoner L, Sokolovska A, Becker C, Stuart L M, Leong J M, Fitzgerald K A. TRIF licenses caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by gram-negative bacteria[J/OL]. Cell, 2012, 150(3): 606-619. [CrossRef]

- Kayagaki N, Stowe I B, Lee B L, O’Rourke K, Anderson K, Warming S, Cuellar T, Haley B, Roose-Girma M, Phung Q T, Liu P S, Lill J R, Li H, Wu J, Kummerfeld S, Zhang J, Lee W P, Snipas S J, Salvesen G S, Morris L X, Fitzgerald L, Zhang Y, Bertram E M, Goodnow C C, Dixit V M. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling[J/OL]. Nature, 2015, 526(7575): 666-671. [CrossRef]

- Khanova E, Wu R, Wang W, Yan R, Chen Y, French S W, Llorente C, Pan S Q, Yang Q, Li Y, Lazaro R, Ansong C, Smith R D, Bataller R, Morgan T, Schnabl B, Tsukamoto H. Pyroptosis by Caspase11/4-Gasdermin-D Pathway in Alcoholic Hepatitis[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2018, 67(5): 1737-1753. [CrossRef]

- Gao B, Duan Y, Lang S, Barupal D, Wu T C, Valdiviez L, Roberts B, Choy Y Y, Shen T, Byram G, Zhang Y, Fan S, Wancewicz B, Shao Y, Vervier K, Wang Y, Zhou R, Jiang L, Nath S, Loomba R, Abraldes J G, Bataller R, Tu X M, Stärkel P, Lawley T D, Fiehn O, Schnabl B. Functional Microbiomics Reveals Alterations of the Gut Microbiome and Host Co-Metabolism in Patients With Alcoholic Hepatitis[J/OL]. Hepatology Communications, 2020, 4(8): 1168-1182. [CrossRef]

- Jin M, Kalainy S, Baskota N, Chiang D, Deehan E C, McDougall C, Tandon P, Martínez I, Cervera C, Walter J, Abraldes J G. Faecal microbiota from patients with cirrhosis has a low capacity to ferment non-digestible carbohydrates into short-chain fatty acids[J/OL]. Liver International: Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver, 2019, 39(8): 1437-1447. [CrossRef]

- Xie G, Zhong W, Li H, Li Q, Qiu Y, Zheng X, Chen H, Zhao X, Zhang S, Zhou Z, Zeisel S H, Jia W. Alteration of bile acid metabolism in the rat induced by chronic ethanol consumption[J/OL]. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2013, 27(9): 3583-3593. [CrossRef]

- Xie G, Zhong W, Zheng X, Li Q, Qiu Y, Li H, Chen H, Zhou Z, Jia W. Chronic ethanol consumption alters mammalian gastrointestinal content metabolites[J/OL]. Journal of Proteome Research, 2013, 12(7): 3297-3306. [CrossRef]

- Park J W, Kim S E, Lee N Y, Kim J H, Jung J H, Jang M K, Park S H, Lee M S, Kim D J, Kim H S, Suk K T. Role of Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases[J/OL]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 23(1): 426. [CrossRef]

- Ridlon J M, Kang D J, Hylemon P B. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria[J/OL]. Journal of Lipid Research, 2006, 47(2): 241-259. [CrossRef]

- Ridlon J M, Harris S C, Bhowmik S, Kang D J, Hylemon P B. Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria[J/OL]. Gut Microbes, 2016, 7(1): 22-39. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström A, Sayin S I, Marschall H U, Bäckhed F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism[J/OL]. Cell Metabolism, 2016, 24(1): 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Chiang J Y L. Bile acid-based therapies for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition, 2020, 9(2): 152-169. [CrossRef]

- Brandl K, Hartmann P, Jih L J, Pizzo D P, Argemi J, Ventura-Cots M, Coulter S, Liddle C, Ling L, Rossi S J, DePaoli A M, Loomba R, Mehal W Z, Fouts D E, Lucey M R, Bosques-Padilla F, Mathurin P, Louvet A, Garcia-Tsao G, Verna E C, Abraldes J G, Brown R S, Vargas V, Altamirano J, Caballería J, Shawcross D, Stärkel P, Ho S B, Bataller R, Schnabl B. Dysregulation of serum bile acids and FGF19 in alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2018, 69(2): 396-405. [CrossRef]

- Cariello M, Piglionica M, Gadaleta R M, Moschetta A. The Enterokine Fibroblast Growth Factor 15/19 in Bile Acid Metabolism[J/OL]. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 2019, 256: 73-93. [CrossRef]

- Di Ciaula A, Bonfrate L, Baj J, Khalil M, Garruti G, Stellaard F, Wang H H, Wang D Q H, Portincasa P. Recent Advances in the Digestive, Metabolic and Therapeutic Effects of Farnesoid X Receptor and Fibroblast Growth Factor 19: From Cholesterol to Bile Acid Signaling[J/OL]. Nutrients, 2022, 14(23): 4950. [CrossRef]

- Kong B, Zhang M, Huang M, Rizzolo D, Armstrong L, Schumacher J, Chow M D, Lee Y H, Guo G L. FXR Deficiency Alters Bile Acid Pool Composition and Exacerbates Chronic Alcohol Induced Liver Injury[J/OL]. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver, 2019, 51(4): 570-576. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Liu T, Zhao X, Gao Y. New insights into the bile acid-based regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives in alcohol-related liver disease[J/OL]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences: CMLS, 2022, 79(9): 486. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, Zhu B, Peng X, Zhou M, Jia D, Gu J. Activation of farnesoid X receptor attenuates hepatic injury in a murine model of alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2014, 443(1): 68-73. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi A, Debelius J, Brenner D A, Karin M, Loomba R, Schnabl B, Knight R. The gut-liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome[J/OL]. Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018, 15(7): 397-411. [CrossRef]

- Kong B, Zhang M, Huang M, Rizzolo D, Armstrong L E, Schumacher J D, Chow M D, Lee Y H, Guo G L. FXR deficiency alters bile acid pool composition and exacerbates chronic alcohol induced liver injury[J/OL]. Digestive and Liver Disease: Official Journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver, 2019, 51(4): 570-576. [CrossRef]

- Manley S, Ding W. Role of farnesoid X receptor and bile acids in alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. B, 2015, 5(2): 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Inagaki T, Moschetta A, Lee Y K, Peng L, Zhao G, Downes M, Yu R T, Shelton J M, Richardson J A, Repa J J, Mangelsdorf D J, Kliewer S A. Regulation of antibacterial defense in the small intestine by the nuclear bile acid receptor[J/OL]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(10): 3920-3925. [CrossRef]

- Thomas C, Pellicciari R, Pruzanski M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases[J/OL]. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 2008, 7(8): 678-693. [CrossRef]

- Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites[J/OL]. Cell, 2016, 165(6): 1332-1345. [CrossRef]

- Keitel V, Donner M, Winandy S, Kubitz R, Häussinger D. Expression and function of the bile acid receptor TGR5 in Kupffer cells[J/OL]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2008, 372(1): 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Spatz M, Ciocan D, Merlen G, Rainteau D, Humbert L, Gomes-Rochette N, Hugot C, Trainel N, Mercier-Nomé F, Domenichini S, Puchois V, Wrzosek L, Ferrere G, Tordjmann T, Perlemuter G, Cassard A M. Bile acid-receptor TGR5 deficiency worsens liver injury in alcohol-fed mice by inducing intestinal microbiota dysbiosis[J/OL]. JHEP reports: innovation in hepatology, 2021, 3(2): 100230. [CrossRef]

- Molinero N, Ruiz L, Sánchez B, Margolles A, Delgado S. Intestinal Bacteria Interplay With Bile and Cholesterol Metabolism: Implications on Host Physiology[J/OL]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2019, 10: 185. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto S, Loo T M, Atarashi K, Kanda H, Sato S, Oyadomari S, Iwakura Y, Oshima K, Morita H, Hattori M, Honda K, Ishikawa Y, Hara E, Ohtani N. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome[J/OL]. Nature, 2013, 499(7456): 97-101. [CrossRef]

- Kurdi P, Kawanishi K, Mizutani K, Yokota A. Mechanism of growth inhibition by free bile acids in lactobacilli and bifidobacteria[J/OL]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2006, 188(5): 1979-1986. [CrossRef]

- Kakiyama G, Hylemon P B, Zhou H, Pandak W M, Heuman D M, Kang D J, Takei H, Nittono H, Ridlon J M, Fuchs M, Gurley E C, Wang Y, Liu R, Sanyal A J, Gillevet P M, Bajaj J S. Colonic inflammation and secondary bile acids in alcoholic cirrhosis[J/OL]. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2014, 306(11): G929-937. [CrossRef]

- Trinchet J C, Gerhardt M F, Balkau B, Munz C, Poupon R E. Serum bile acids and cholestasis in alcoholic hepatitis. Relationship with usual liver tests and histological features[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 1994, 21(2): 235-240. [CrossRef]

- Cummings J H. Short chain fatty acids in the human colon[J/OL]. Gut, 1981, 22(9): 763-779. [CrossRef]

- Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn A N, Mackay C R, Macia L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease[J/OL]. Advances in Immunology, 2014, 121: 91-119. [CrossRef]

- Hamer H M, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost F J, Brummer R J. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function[J/OL]. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2008, 27(2): 104-119. [CrossRef]

- Israel Y, Orrego H, Carmichael F J. Acetate-mediated effects of ethanol[J/OL]. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 1994, 18(1): 144-148. [CrossRef]

- Visapaa J P. Microbes and mucosa in the regulation of intracolonic acetaldehyde concentration during ethanol challenge[J/OL]. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 2002, 37(4): 322-326. [CrossRef]

- Couch R D, Dailey A, Zaidi F, Navarro K, Forsyth C B, Mutlu E, Engen P A, Keshavarzian A. Alcohol induced alterations to the human fecal VOC metabolome[J/OL]. PloS One, 2015, 10(3): e0119362. [CrossRef]

- Elamin E E, Masclee A A, Dekker J, Pieters H J, Jonkers D M. Short-chain fatty acids activate AMP-activated protein kinase and ameliorate ethanol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in Caco-2 cell monolayers[J/OL]. The Journal of Nutrition, 2013, 143(12): 1872-1881. [CrossRef]

- Säemann M D, Parolini O, Böhmig G A, Kelemen P, Krieger P M, Neumüller J, Knarr K, Kammlander W, Hörl W H, Diakos C, Stuhlmeier K, Zlabinger G J. Bacterial metabolite interference with maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells[J]. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 2002, 71(2): 238-246.

- Li M, van Esch B C A M, Wagenaar G T M, Garssen J, Folkerts G, Henricks P A J. Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells[J/OL]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2018, 831: 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Cresci G A, Bush K, Nagy L E. Tributyrin Supplementation Protects Mice from Acute Ethanol-Induced Gut Injury[J/OL]. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research, 2014, 38(6): 1489-1501. [CrossRef]

- Maslowski K M, Vieira A T, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, Schilter H C, Rolph M S, Mackay F, Artis D, Xavier R J, Teixeira M M, Mackay C R. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43[J/OL]. Nature, 2009, 461(7268): 1282-1286. [CrossRef]

- Ohira H, Fujioka Y, Katagiri C, Mamoto R, Aoyama-Ishikawa M, Amako K, Izumi Y, Nishiumi S, Yoshida M, Usami M, Ikeda M. Butyrate attenuates inflammation and lipolysis generated by the interaction of adipocytes and macrophages[J/OL]. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis, 2013, 20(5): 425-442. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y, Cai X, Fei W, Ye Y, Zhao M, Zheng C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in immunity, inflammation and metabolism[J/OL]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2022, 62(1): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Kendrick S F W, O’Boyle G, Mann J, Zeybel M, Palmer J, Jones D E J, Day C P. Acetate, the key modulator of inflammatory responses in acute alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2010, 51(6): 1988-1997. [CrossRef]

- Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward R E, Martin R J, Lefevre M, Cefalu W T, Ye J. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice[J/OL]. Diabetes, 2009, 58(7): 1509-1517. [CrossRef]

- Demigné C, Morand C, Levrat M A, Besson C, Moundras C, Rémésy C. Effect of propionate on fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis and on acetate metabolism in isolated rat hepatocytes[J/OL]. The British Journal of Nutrition, 1995, 74(2): 209-219. [CrossRef]

- Chambers E S, Viardot A, Psichas A, Morrison D J, Murphy K G, Zac-Varghese S E K, MacDougall K, Preston T, Tedford C, Finlayson G S, Blundell J E, Bell J D, Thomas E L, Mt-Isa S, Ashby D, Gibson G R, Kolida S, Dhillo W S, Bloom S R, Morley W, Clegg S, Frost G. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults[J/OL]. Gut, 2015, 64(11): 1744-1754. [CrossRef]

- Alves-Bezerra M, Cohen D E. Triglyceride Metabolism in the Liver[J/OL]. Comprehensive Physiology, 2017, 8(1): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Dubinkina V B, Tyakht A V, Odintsova V Y, Yarygin K S, Kovarsky B A, Pavlenko A V, Ischenko D S, Popenko A S, Alexeev D G, Taraskina A Y, Nasyrova R F, Krupitsky E M, Shalikiani N V, Bakulin I G, Shcherbakov P L, Skorodumova L O, Larin A K, Kostryukova E S, Abdulkhakov R A, Abdulkhakov S R, Malanin S Y, Ismagilova R K, Grigoryeva T V, Ilina E N, Govorun V M. Links of gut microbiota composition with alcohol dependence syndrome and alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Microbiome, 2017, 5(1): 141. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan R, Gupta H, Jeong J J, Sharma S P, Won S M, Oh K K, Yoon S J, Han S H, Yang Y J, Baik G H, Bang C S, Kim D J, Suk K T. Characteristics of microbiome-derived metabolomics according to the progression of alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Hepatology International, 2024, 18(2): 486-499. [CrossRef]

- Tom A, Nair K S. Assessment of branched-chain amino Acid status and potential for biomarkers[J/OL]. The Journal of Nutrition, 2006, 136(1 Suppl): 324S-30S. [CrossRef]

- Park J H, Lee S Y. Fermentative production of branched chain amino acids: a focus on metabolic engineering[J/OL]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2010, 85(3): 491-506. [CrossRef]

- Takegoshi K, Honda M, Okada H, Sunagozaka H, Matsuzawa N, Takamura T, Tanaka T, Kaneko S. Branched-chain amino acids improve liver fibrosis and reduce tumorigenesis in mice fed an atherogenic high-fat diet by suppressing PDGFR-β/ERK signaling: 780[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 58: 578A.

- Shirabe K, Yoshimatsu M, Motomura T, Takeishi K, Toshima T, Muto J, Matono R, Taketomi A, Uchiyama H, Maehara Y. Beneficial effects of supplementation with branched-chain amino acids on postoperative bacteremia in living donor liver transplant recipients[J/OL]. Liver Transplantation: Official Publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, 2011, 17(9): 1073-1080. [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx T, Schnabl B. Indoles: metabolites produced by intestinal bacteria capable of controlling liver disease manifestation[J/OL]. Journal of Internal Medicine, 2019, 286(1): 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx T, Duan Y, Wang Y, Oh J H, Alexander L M, Huang W, Stärkel P, Ho S B, Gao B, Fiehn O, Emond P, Sokol H, van Pijkeren J P, Schnabl B. Bacteria engineered to produce IL-22 in intestine induce expression of REG3G to reduce ethanol-induced liver disease in mice[J/OL]. Gut, 2019, 68(8): 1504-1515. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg G F, Fouser L A, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22[J/OL]. Nature Immunology, 2011, 12(5): 383-390. [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx T, Duan Y, Wang Y, Oh J H, Alexander L M, Huang W, Stärkel P, Ho S B, Gao B, Fiehn O, Emond P, Sokol H, van Pijkeren J P, Schnabl B. Bacteria engineered to produce IL-22 in intestine induce expression of REG3G to reduce ethanol-induced liver disease in mice[J/OL]. Gut, 2019, 68(8): 1504-1515. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S, Reddy K R, O’Leary J G, Vargas H E, Lai J C, Kamath P S, Tandon P, Wong F, Subramanian R M, Thuluvath P, Fagan A, White M B, Gavis E A, Sehrawat T, de la Rosa Rodriguez R, Thacker L R, Sikaroodi M, Garcia-Tsao G, Gillevet P M. Serum Levels of Metabolites Produced by Intestinal Microbes and Lipid Moieties Independently Associated With Acute on Chronic Liver Failure and Death in Patients With Cirrhosis[J/OL]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 159(5): 1715-1730.e12. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani A, Massy Z A, Meijers B, Evenepoel P, Vanholder R, Raj D S. Role of the Gut Microbiome in Uremia: A Potential Therapeutic Target[J/OL]. American Journal of Kidney Diseases: The Official Journal of the National Kidney Foundation, 2016, 67(3): 483-498. [CrossRef]

- Garcovich M, Zocco M A, Roccarina D, Ponziani F R, Gasbarrini A. Prevention and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: focusing on gut microbiota[J/OL]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2012, 18(46): 6693-6700. [CrossRef]

- Dhiman R K. Gut microbiota and hepatic encephalopathy[J/OL]. Metabolic Brain Disease, 2013, 28(2): 321-326. [CrossRef]

- Calzadilla N, Zilberstein N, Hanscom M, Al Rashdan H T, Chacra W, Gill R K, Alrefai W A. Serum metabolomic analysis in cirrhotic alcohol-associated liver disease patients identified differentially altered microbial metabolites and novel potential biomarkers for disease severity[J/OL]. Digestive and Liver Disease, 2024, 56(6): 923-931. [CrossRef]

- Helsley R N, Miyata T, Kadam A, Varadharajan V, Sangwan N, Huang E C, Banerjee R, Brown A L, Fung K K, Massey W J, Neumann C, Orabi D, Osborn L J, Schugar R C, McMullen M R, Bellar A, Poulsen K L, Kim A, Pathak V, Mrdjen M, Anderson J T, Willard B, McClain C J, Mitchell M, McCullough A J, Radaeva S, Barton B, Szabo G, Dasarathy S, Garcia-Garcia J C, Rotroff D M, Allende D S, Wang Z, Hazen S L, Nagy L E, Brown J M. Gut microbial trimethylamine is elevated in alcohol-associated hepatitis and contributes to ethanol-induced liver injury in mice[J/OL]. eLife, 2022, 11: e76554. [CrossRef]

- Oh J, Kim J, Lee S, Park G, Baritugo K A G, Han K J, Lee S, Sung G H. 1H NMR Serum Metabolomic Change of Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) Is Associated with Alcoholic Liver Disease Progression[J/OL]. Metabolites, 2024, 14(1): 39. [CrossRef]

- Chu H, Duan Y, Lang S, Jiang L, Wang Y, Llorente C, Liu J, Mogavero S, Bosques-Padilla F, Abraldes J G, Vargas V, Tu X M, Yang L, Hou X, Hube B, Stärkel P, Schnabl B. The Candida albicans exotoxin candidalysin promotes alcohol-associated liver disease[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2020, 72(3): 391-400. [CrossRef]

- J P D, Fj R O, M G C, A G. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics[J/OL]. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 2019, 10(suppl_1). [CrossRef]

- van Zyl W F, Deane S M, Dicks L M T. Molecular insights into probiotic mechanisms of action employed against intestinal pathogenic bacteria[J/OL]. Gut Microbes, 2020, 12(1): 1831339. [CrossRef]

- Singh R P, Shadan A, Ma Y. Biotechnological Applications of Probiotics: A Multifarious Weapon to Disease and Metabolic Abnormality[J/OL]. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, 2022, 14(6): 1184-1210. [CrossRef]

- Dalal R, McGee R G, Riordan S M, Webster A C. Probiotics for people with hepatic encephalopathy[J/OL]. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017, 2(2): CD008716. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Lei L, Shi W, Li X, Huang X, Lan L, Lin J, Liang Q, Li W, Yang J. Probiotics are beneficial for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials[J/OL]. Frontiers in Medicine, 2024, 11: 1379333. [CrossRef]

- Leitner U, Brits A, Xu D, Patil S, Sun J. Efficacy of probiotics on improvement of health outcomes in cirrhotic liver disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials[J/OL]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2024, 981: 176874. [CrossRef]

- Horvath A, Durdevic M, Leber B, di Vora K, Rainer F, Krones E, Douschan P, Spindelboeck W, Durchschein F, Zollner G, Stauber R E, Fickert P, Stiegler P, Stadlbauer V. Changes in the Intestinal Microbiome during a Multispecies Probiotic Intervention in Compensated Cirrhosis[J/OL]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(6): 1874. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Liu Y, Guo X, Ma Y, Zhang H, Liang H. Effect of Lactobacillus casei on lipid metabolism and intestinal microflora in patients with alcoholic liver injury[J/OL]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2021, 75(8): 1227-1236. [CrossRef]

- Stadlbauer V, Mookerjee R P, Hodges S, Wright G A K, Davies N A, Jalan R. Effect of probiotic treatment on deranged neutrophil function and cytokine responses in patients with compensated alcoholic cirrhosis[J/OL]. Journal of Hepatology, 2008, 48(6): 945-951. [CrossRef]

- J M, F F, E G L, H L, H J, R S, K S, S F, J M, A M, Ij C, L T, N D, R W, R M, G W, R J. A Double-Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota in Stable Cirrhotic Patients[J/OL]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Lata J, Novotný I, Príbramská V, Juránková J, Fric P, Kroupa R, Stibůrek O. The effect of probiotics on gut flora, level of endotoxin and Child-Pugh score in cirrhotic patients: results of a double-blind randomized study[J/OL]. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2007, 19(12): 1111-1113. [CrossRef]

- Tian X, Li R, Jiang Y, Zhao F, Yu Z, Wang Y, Dong Z, Liu P, Li X. Bifidobacterium breve ATCC15700 pretreatment prevents alcoholic liver disease through modulating gut microbiota in mice exposed to chronic alcohol intake[J/OL]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2020, 72: 104045. [CrossRef]

- Han S H, Suk K T, Kim D J, Kim M Y, Baik S K, Kim Y D, Cheon G J, Choi D H, Ham Y L, Shin D H, Kim E J. Effects of probiotics (cultured Lactobacillus subtilis/Streptococcus faecium) in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis: randomized-controlled multicenter study[J/OL]. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2015, 27(11): 1300-1306. [CrossRef]

- Chang B, Sang L, Wang Y, Tong J, Zhang D, Wang B. The protective effect of VSL#3 on intestinal permeability in a rat model of alcoholic intestinal injury[J/OL]. BMC gastroenterology, 2013, 13: 151. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth C B, Farhadi A, Jakate S M, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Keshavarzian A. Lactobacillus GG treatment ameliorates alcohol-induced intestinal oxidative stress, gut leakiness, and liver injury in a rat model of alcoholic steatohepatitis[J/OL]. Alcohol, 2009, 43(2): 163-172. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Wang X, Zhu L, Tu Y, Chen W, Gong L, Pan T, Lin H, Lin J, Sun H, Ge Y, Wei L, Guo Y, Lu C, Chen Y, Xu L. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG combined with inosine ameliorates alcohol-induced liver injury through regulation of intestinal barrier and Treg/Th1 cells[J/OL]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2022, 439: 115923. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Liu Y, Kirpich I, Ma Z, Wang C, Zhang M, Suttles J, McClain C, Feng W. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reduces hepatic TNFα production and inflammation in chronic alcohol-induced liver injury[J/OL]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2013, 24(9): 1609-1615. [CrossRef]

- Ps H, Cw C, Yw K, Hh H. Lactobacillus spp. reduces ethanol-induced liver oxidative stress and inflammation in a mouse model of alcoholic steatohepatitis[J/OL]. Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 2021, 21(3). [CrossRef]

- Bang C S, Hong S H, Suk K T, Kim J B, Han S H, Sung H, Kim E J, Kim M J, Kim M Y, Baik S K, Kim D J. Effects of Korean Red Ginseng (Panax ginseng), urushiol (Rhus vernicifera Stokes), and probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and Lactobacillus acidophilus R0052) on the gut-liver axis of alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. Journal of Ginseng Research, 2014, 38(3): 167-172. [CrossRef]

- Hong M, Kim S W, Han S H, Kim D J, Suk K T, Kim Y S, Kim M J, Kim M Y, Baik S K, Ham Y L. Probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and acidophilus R0052) reduce the expression of toll-like receptor 4 in mice with alcoholic liver disease[J/OL]. PloS One, 2015, 10(2): e0117451. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Fan D, Wang J, Wang Y, Li A, Wu S, Zhang B, Liu J, Wang S. Lactobacillus rhamnosus NKU FL1-8 Isolated from Infant Feces Ameliorates the Alcoholic Liver Damage by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Barrier in C57BL/6J Mice[J/OL]. Nutrients, 2024, 16(13): 2139. [CrossRef]

- Thomas C M, Hong T, van Pijkeren J P, Hemarajata P, Trinh D V, Hu W, Britton R A, Kalkum M, Versalovic J. Histamine derived from probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppresses TNF via modulation of PKA and ERK signaling[J/OL]. PloS One, 2012, 7(2): e31951. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Xiang X, Liu C, Cai T, Li T, Chen Y, Bai J, Shi H, Zheng T, Huang M, Fu W. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Lactobacillus reuteri Alleviating Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury in Mice by Enhancing the Farnesoid X Receptor Signaling Pathway[J/OL]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2022, 70(39): 12550-12564. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X W, Li Y T, Ye J Z, Lv L X, Yang L Y, Bian X Y, Wu W R, Wu J J, Shi D, Wang Q, Fang D Q, Wang K C, Wang Q Q, Lu Y M, Xie J J, Li L J. New strain of Pediococcus pentosaceus alleviates ethanol-induced liver injury by modulating the gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid metabolism[J/OL]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2020, 26(40): 6224-6240. [CrossRef]

- Philips C A, Phadke N, Ganesan K, Ranade S, Augustine P. Corticosteroids, nutrition, pentoxifylline, or fecal microbiota transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis[J/OL]. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology: Official Journal of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology, 2018, 37(3): 215-225. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S, Gavis E A, Fagan A, Wade J B, Thacker L R, Fuchs M, Patel S, Davis B, Meador J, Puri P, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P M. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Alcohol Use Disorder[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2021, 73(5): 1688-1700. [CrossRef]

- Philips C A, Pande A, Shasthry S M, Jamwal K D, Khillan V, Chandel S S, Kumar G, Sharma M K, Maiwall R, Jindal A, Choudhary A, Hussain M S, Sharma S, Sarin S K. Healthy Donor Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Steroid-Ineligible Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Pilot Study[J/OL]. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2017, 15(4): 600-602. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S, Kakiyama G, Savidge T, Takei H, Kassam Z A, Fagan A, Gavis E A, Pandak W M, Nittono H, Hylemon P B, Boonma P, Haag A, Heuman D M, Fuchs M, John B, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P M. Antibiotic-Associated Disruption of Microbiota Composition and Function in Cirrhosis Is Restored by Fecal Transplant[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2018, 68(4): 1549-1558. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj J S, Salzman N H, Acharya C, Sterling R K, White M B, Gavis E A, Fagan A, Hayward M, Holtz M L, Matherly S, Lee H, Osman M, Siddiqui M S, Fuchs M, Puri P, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P M. Fecal Microbial Transplant Capsules Are Safe in Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Phase 1, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial[J/OL]. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 2019, 70(5): 1690-1703. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Roy A, Premkumar M, Verma N, Duseja A, Taneja S, Grover S, Chopra M, Dhiman R K. Fecal microbiota transplantation in alcohol-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure: an open-label clinical trial[J/OL]. Hepatology International, 2022, 16(2): 433-446. [CrossRef]

- Abedon S T, García P, Mullany P, Aminov R. Editorial: Phage Therapy: Past, Present and Future[J/OL]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 981. [CrossRef]

- Morencos F C, de las Heras Castaño G, Martín Ramos L, López Arias M J, Ledesma F, Pons Romero F. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis[J/OL]. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 1995, 40(6): 1252-1256. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).